Rabies: For health professionals

On this page

- Key information

- Transmission

- Risk groups

- Clinical manifestations

- Diagnosis and laboratory testing

- Management of rabies exposure

- Surveillance

Key information

Rabies is a rare disease in humans caused by a lyssavirus of the Rhabdoviridae family. The rabies virus is most commonly transmitted to humans in the saliva from an infected mammal. It is highly neurotropic and causes fatal encephalomyelitis once the infection is established and reaches the central nervous system.

Children are considered at higher risk to contract rabies due to the type and frequency of interactions that they have with animals.

Once clinical symptoms develop, rabies is almost always fatal. Death typically occurs within 7 to 14 days of symptom onset although critical care measures (supportive therapy) may delay the timing of death.

Rabies in humans can be prevented through pre-exposure prophylaxis and prompt post-exposure prophylaxis combined with appropriate medical care.

Transmission

Rabies is most often transmitted to humans from saliva of an infected mammal, most commonly through a bite, or less commonly through:

- a scratch

- exposure across mucous membranes of the eyes, nose or mouth

Transmission is rare:

- via airborne

- from organ transplant from a donor who had rabies infection

Once an individual has rabies infection, the virus:

- replicates in the peripheral muscle tissue

- spreads along the peripheral nerves and spinal cord to the brain

- disseminates through the central nervous system

- centrifugally spreads along nerves to various organs, including the salivary glands

Risk groups

Children are considered at higher risk of rabies infection because they:

- play with animals more often

- are more likely to be bitten

- are less likely to report bites, scratches or licks

Other higher risk groups include:

- people who work with animals (dead or alive)

- hunters and trappers

- spelunkers

- laboratory workers who handle rabies virus or samples potentially containing rabies virus

- travellers to countries where rabies is transmitted more commonly

Clinical manifestations

The incubation period for rabies can vary depending on factors such as the:

- amount of virus introduced

- distance from the site of the exposure on the body to the brain

Typically, the incubation period range from 1 to 3 months, but it can be as short as a few days or as long as several years after exposure.

The disease starts with a non-specific prodromal phase. After that, the disease takes 1 of 2 forms:

- paralytic rabies (called 'dumb' in animals)

- encephalitic or classical rabies (called 'furious' in animals)

About 80% of patients develop the encephalitic form of rabies, whereas about 20% develop the paralytic form.

Prodromal symptoms

Both forms of rabies (encephalitic and paralytic) are preceded by non-specific prodromal symptoms that may last for up to 10 days, prior to the onset of neurologic symptoms, and include:

- pain, tingling, prickling or burning sensations at the wound site (in 80% of cases)

- flu-like symptoms such as fever, malaise, headache, fatigue and gastrointestinal issues

- occasional photophobia

- sore throat

Encephalitic rabies

Encephalitic rabies is characterised by:

- hydrophobia (33% to 50% of cases)

- aerophobia (approximately 9% of cases)

- agitation and combativeness, which may alternate with periods of calmness (50% of cases)

- symptoms of generalized arousal or hyperexcitability that can be associated with:

- disorientation

- fluctuating consciousness

- restlessness

- hallucinations (visual or auditory)

Mental status changes are evident upon examination.

Other signs include:

- neurological signs, such as:

- increased muscle tone

- increased tendon reflexes

- extensor plantar responses

- fasciculations

- nuchal rigidity

- seizures

- signs of autonomic nervous system dysfunction, including:

- sweating

- lacrimation

- tachycardia and arrhythmias

- piloerection

- hyperpyrexia

- dilated pupils

- hypersalivation

- tachycardia and arrhythmias

- signs of cranial nerve palsies, such as:

- facial weakness

- ophthalmoplegia

- tongue weakness

- impaired swallowing

- vocal cord weakness and voice changes

- progression to severe flaccid paralysis

- coma

- multiple organ failure

Paralytic rabies

Paralytic rabies is characterized by:

- urinary incontinence

- prominent flaccid muscle weakness often beginning in the bitten extremity and spreading to other extremities

- progressive weakness of bulbar and respiratory muscles

Diagnosis and laboratory testing

For ante-mortem diagnosis:

- a fluorescent antibody test can be performed on frozen sections of nuchal skin biopsy material for detection of viral antigen

- reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for detection of viral ribonucleic acid (RNA) can also be performed on skin, saliva and cerebrospinal fluid samples

For post-mortem diagnosis, a fluorescent antibody test can be performed on human brain tissue, as is also used for all animal samples.

The National Microbiology Laboratory provides:

- testing for neutralizing antibody in cerebrospinal fluid samples for all provinces and territories

- serology testing from blood for all provinces and territories except Ontario

- in Ontario, serology testing is conducted at the Public Health Ontario Laboratory

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency Ottawa Laboratory provides testing for antigen and RNA detection.

Learn more about:

- Rabies: Requisition forms

- Guidance for Submission of Human Specimens for Rabies Testing in Canada (PDF)

Management of rabies exposure

Rabies is a preventable disease. Pre-exposure and post-exposure prophylaxis is available. Additionally, proper wound care after an animal bite can significantly reduce the risk of rabies.

The Canadian Immunization Guide chapter on rabies vaccine provides details on:

- efficacy, effectiveness, and immunogenicity

- recommendations for use

- vaccine administration

- serologic testing

- vaccine and immunoglobulin safety and adverse events and reporting

Rabies vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide

Pre-exposure prophylaxis: Immunization of high-risk groups

Rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis consists of vaccination with rabies vaccine. In Canada, human diploid cell vaccine or purified chick embryo cell vaccine are given on days 0, 7 and any time between days 21 to 28.

Rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis is recommended for high-risk groups, such as:

- laboratory workers who handle the rabies virus

- veterinarians, veterinary staff, animal control and wildlife workers

- certain travellers

- hunter and trappers in areas with confirmed rabies

- spelunkers (cavers)

Workers should regularly measure their antibody titres to determine if they need booster doses if they are continually exposed to rabies virus:

- in a laboratory

- by potentially rabid animals

Depending on the province or territory, rabies vaccinations for certain high-risk groups may be covered. For more information in your area, contact your local public health authority.

Medical care after an exposure to a potentially rabid animal

There is no treatment for rabies once symptoms have begun. As such, efforts should focus on:

- prevention before the onset of symptoms, such as:

- wound care

- post-exposure prophylaxis

- supportive therapy after symptom onset

Almost all patients succumb to the disease or its complications within a few weeks of illness onset.

Wound care

First aid for potential exposure to a rabid animal begins with good wound care as soon as possible. This can reduce the risk of rabies by up to 90%.

Clean and flush the wound with soap and water for 15 minutes to its full depth.

Some guidelines suggest the use of viricidal agents such as iodine or alcohol.

Avoid suturing the wound if possible.

Post-exposure prophylaxis

Following wound care, health care providers will need to decide whether to administer rabies post-exposure prophylaxis (RPEP). RPEP is intended to neutralize any rabies virus that was introduced by the animal exposure before it can enter the nervous system.

For people who have not been previously vaccinated against rabies, RPEP involves administering rabies immune globulin (RabIg) treatment and rabies vaccine. RabIg contains preformed antibodies providing rapid passive immunity that lasts for only a few weeks. It is given as a 20 IU/kg dose with as much of the dose administered directly into and around the wounds as possible. The remainder is administered intramuscularly using a separate needle and syringe at a site distant to vaccine administration.

For people who have been previously vaccinated against rabies, only rabies vaccine is required for RPEP.

Rabies vaccine provides active immunity which begins to develop within 2 weeks of initiating vaccination. Immunity from rabies vaccine lasts considerably longer than RabIg. Vaccination schedules depend on previous history of vaccination and medical history.

Post-exposure prophylaxis risk assessment

RPEP is initiated based on an assessment of risk. The risk assessment and a decision to provide RPEP should be made with local public health authorities, and possibly veterinary authorities. Factors to consider before initiating RPEP include:

- the species of animal involved, including the prevalence of:

- rabies in that species

- rabies in other species in the area

- whether the type of exposure was:

- a bite

- a non-bite, such as:

- transplant of infected organs

- saliva contact with open skin or mucous membranes

- direct contact with a bat (unless 1 of these 3 potential modes of exposure has occurred, transmission of rabies is highly unlikely)

- the circumstances of the exposure (provoked or unprovoked)

- the vaccination status and behaviour of the domestic animal

- the age of the exposed person

- the location and severity of the wound or bite (e.g., the size and number of bites)

In general, if the exposure was to a dog, cat or ferret, the animal can be observed for signs of rabies for 10 days. Public health and animal health authorities collaborate to assist in monitoring the animal. Rabies viral excretion in saliva does not generally precede symptom development by more than 10 days. Therefore, if the animal is alive and well at the end of the 10 days, the animal would not have transmitted rabies at the time of the bite.

If the dog, cat or ferret is not available for observation, the local public health authority, or provincial or territorial public health authority will assist in the risk assessment to determine the need for RPEP.

Any direct contact with a bat generally warrants RPEP. Exposure to any wild terrestrial animal also generally requires RPEP, unless:

- rabies is not considered likely

- the animal can be rapidly tested for rabies

For post-exposure prophylaxis of previously unimmunized immunocompetent persons:

- 4 doses of vaccine should be administered on days 0, 3, 7 and 14

- 1 dose of RabIg should be administered on day 0

Unimmunized immunocompromised persons should also receive a fifth dose of vaccine on day 28. Unimmunized immunocompromised persons include people:

- who have immunosuppressive illnesses

- taking chloroquine and other antimalarials

- taking corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents

RabIg should not be given to people who have been previously appropriately immunized. In previously appropriately immunized people who require post-exposure prophylaxis, only 2 vaccine doses are recommended on day 0 and 3 days later.

Learn more about:

Surveillance

Health professionals play a critical role in identifying and reporting cases of rabies virus.

Rabies in humans is a nationally notifiable disease in Canada. Health professionals must report human cases to the local public health authority as soon as possible.

In Canada, rabies in animals is also a reportable disease under the Health of Animals Act. All suspected cases in animals must be reported to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

Rabies virus variants

Globally, canine-mediated rabies continues to cause thousands of deaths every year in over 150 countries and territories. It mostly affects communities with limited access to health care and veterinary systems.

In Canada, the canine variant of rabies virus is not present. Wildlife are the main reservoirs for rabies. Wildlife variants of rabies virus include:

- bat

- fox

- skunk

- raccoon

All variants can be transmitted:

- within the reservoir host species

- by spillover to other mammalian species

Humans and animals, such as dogs, cats and livestock, can be infected with any strain of rabies by exposure to other animals that are infected with these strains. Health professionals should be aware of the rabies epidemiology in their region to help inform risk assessments for their patients.

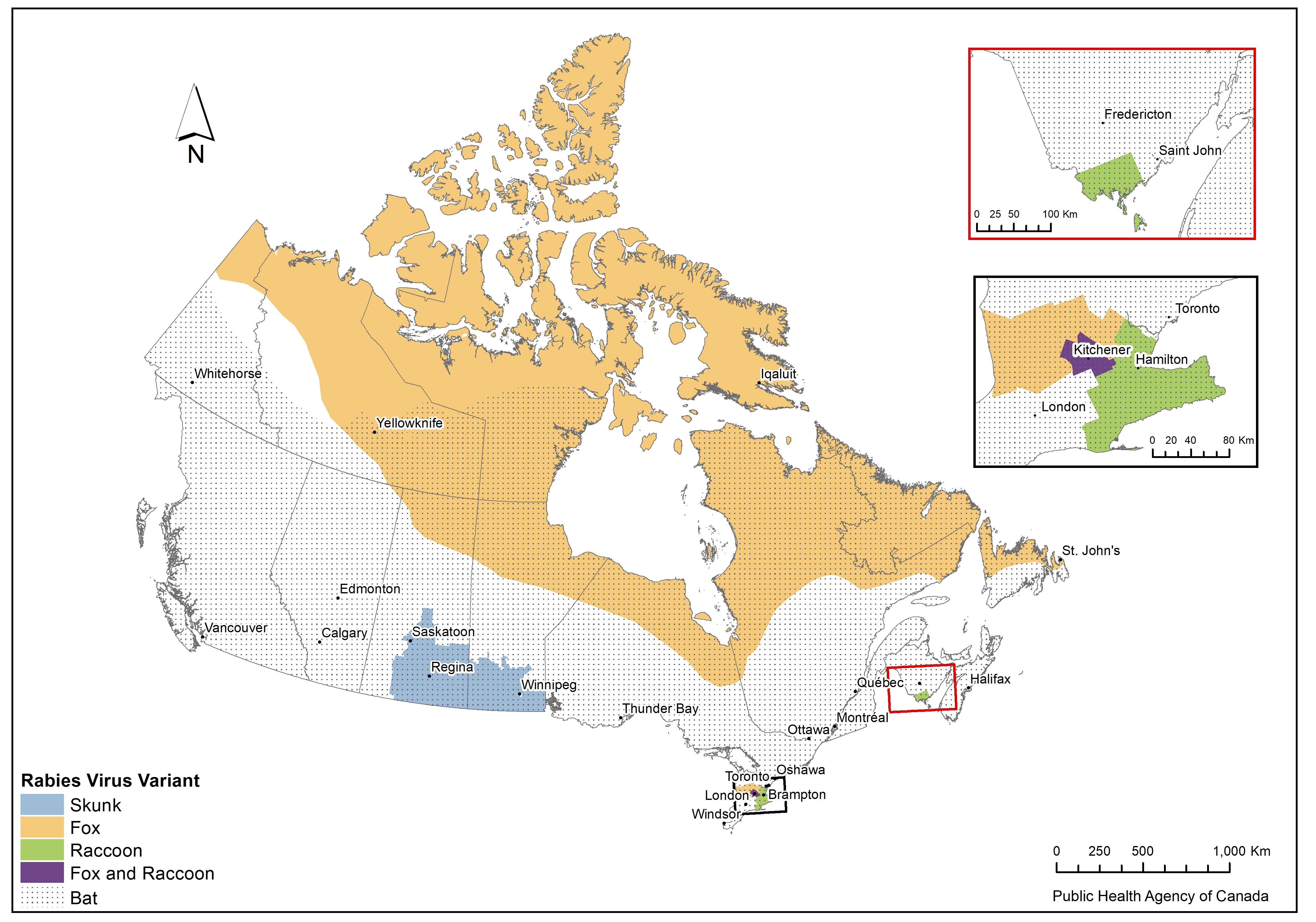

Figure 1 shows the distribution of rabies virus variants in Canada, except for bat rabies virus variant and fox rabies virus variant in northern Canada where host geographic ranges are used instead.

Figure 1: Text description

Rabies virus variant (RVV) ranges are depicted in a map of Canada by census division, except for bat RVV and fox RVV in northern regions of Canada where host geographic ranges are used. Bat variants are considered a potential risk throughout most of Canada, with the exception of the far north, where bat populations have not been confirmed. Fox variant is presumed to be found in northern regions of Canada, excluding Newfoundland, in line with the Arctic fox habitat range.

The skunk variant is found in central/southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan; whereas, the raccoon variant is found in a small area of southern Ontario, southern Quebec and southern New Brunswick.

Data sources:

- Rabies census division data: Laboratory test results, including confirmed cases by animal species, location, and rabies virus variant, were provided to the Public Health Agency of Canada by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency for map development.

- Arctic fox habitat range: Base shapefiles obtained from the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List of Threatened Species.

- Bat habitat range: Base shapefiles obtained from the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada and International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List of Threatened Species.

Previous maps

2016 to 2020

Figure 2: Text description

Rabies virus variant (RVV) ranges are depicted in a map of Canada by census division, except for bat RVV and fox RVV in northern regions of Canada where host geographic ranges are used. The bat variant is visualized to be found across most of Canada, except for the more northern regions of the territories. Similarly, fox variant in northern regions of Canada is visualized to span across the country, in line with fox habitat range.

The skunk variant is found in Manitoba and Saskatchewan. The raccoon variant is found in a small area of southern Ontario and southern New Brunswick. Both fox and raccoon variants are found in a small region of southern Ontario.

Learn more about:

- Notifiable Diseases Online

- National case definition: Rabies

- Positive rabies results by province and animal type