Chapter 15 of the Canadian Tuberculosis Standards: Monitoring tuberculosis program performance

On this page

- Authors and affiliations

- Key points

- Introduction

- Background

- Design and limitations of a performance monitoring framework

- Core program performance indicators

- Analytic and action strategies

- Summary

- Disclosure statement

- Funding

- Appendix 1: Monitoring tuberculosis program performance

- References

Authors and affiliations

Courtney Heffernan; Tuberculosis Program Evaluation and Research Unit, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Margaret Haworth-Brockman; National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Pierre Plourde; Max Rady College of Medicine, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba; Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Tom Wong; Public Health for Indigenous Services Canada; Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Giovanni Ferrara; Tuberculosis Program Evaluation and Research Unit, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Richard Long; Tuberculosis Program Evaluation and Research Unit, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Key points

- Program performance monitoring provides evidence of the quality and value of the services that tuberculosis (TB) programs provide.

- All TB programs in Canada are encouraged to monitor the same core indicators of performance using the definitions and suggested targets provided.

- This framework should be considered a minimum standard for monitoring Canadian TB programs; jurisdictions are encouraged to monitor additional indicators relevant to the populations served.

- Assessment against targets produces quantitative measures of performance, which are useful to reallocate efforts and resources.

- Program performance monitoring should be annual, with summaries made available to TB programs and other relevant stakeholders, as well as the public.

- Program performance monitoring requires adequate human resources dedicated to data collection, validation and analyses processes.

- Interpretation of monitoring results should be performed in close collaboration with the physician/nursing leads to ensure clinically relevant judgments are properly considered.

- Solutions to programmatic underperformance should be collaborative, involving members of TB-affected communities, select population groups, and relevant stakeholders.

- TB programs should monitor their capacity to provide patient-centered care and favorably influence long-term outcomes, which, among other program staff, is dependent on having dedicated support of a social worker.

1. Introduction

This new chapter of the Canadian TB Standards (the Standards) is focused on the role of program performance monitoring in the era of TB elimination. This chapter describes a program performance monitoring framework as part of the Standards to measure the value, quality and impact of services provided by TB programs across Canada.Reference 1Reference 2 In addition to frontline staff of TB programs, the intended audience for this chapter includes TB program managers, health policy leaders and physician/nursing leads.

2. Background

In 2014, after the full endorsement of its member states through a World Health Assembly resolution, the World Health Organization (WHO) began promoting the new End TB Strategy as the global approach to eliminating TB.Reference 3 This strategy outlines three major pillars: the provision of high-quality, patient-centered prevention and care (Pillar 1); increased political will, and sustained resources for bold action (Pillar 2); and research and innovation (Pillar 3).Reference 4 Implementation of these pillars is meant to help achieve three targets by the year 2035: 1) reduce the number of new TB cases by 90% and 2) the number of TB-attributable deaths by 95%, both as compared to 2015; and 3) have no TB-affected families incurring catastrophic costs due to TB.Reference 4

To evaluate national progress toward achieving these targets, systematic program performance monitoring is recommended as part of the End TB strategy and has been widely adopted internationally.Reference 5Reference 6Reference 7Reference 8Reference 9 Canada is a signatory to the End TB Strategy and thus has an obligation to implement this recommendation. The purpose of such evaluations is to distinguish programs that promote health and prevent disease from those that do not.Reference 10 In turn, monitoring generates information that can be used to judge the quality and value of public health programs, like TB services.Reference 11 An appropriately designed program performance monitoring framework should document progress toward goals, identify areas for improvement and demonstrate the impact of resource investments.Reference 12

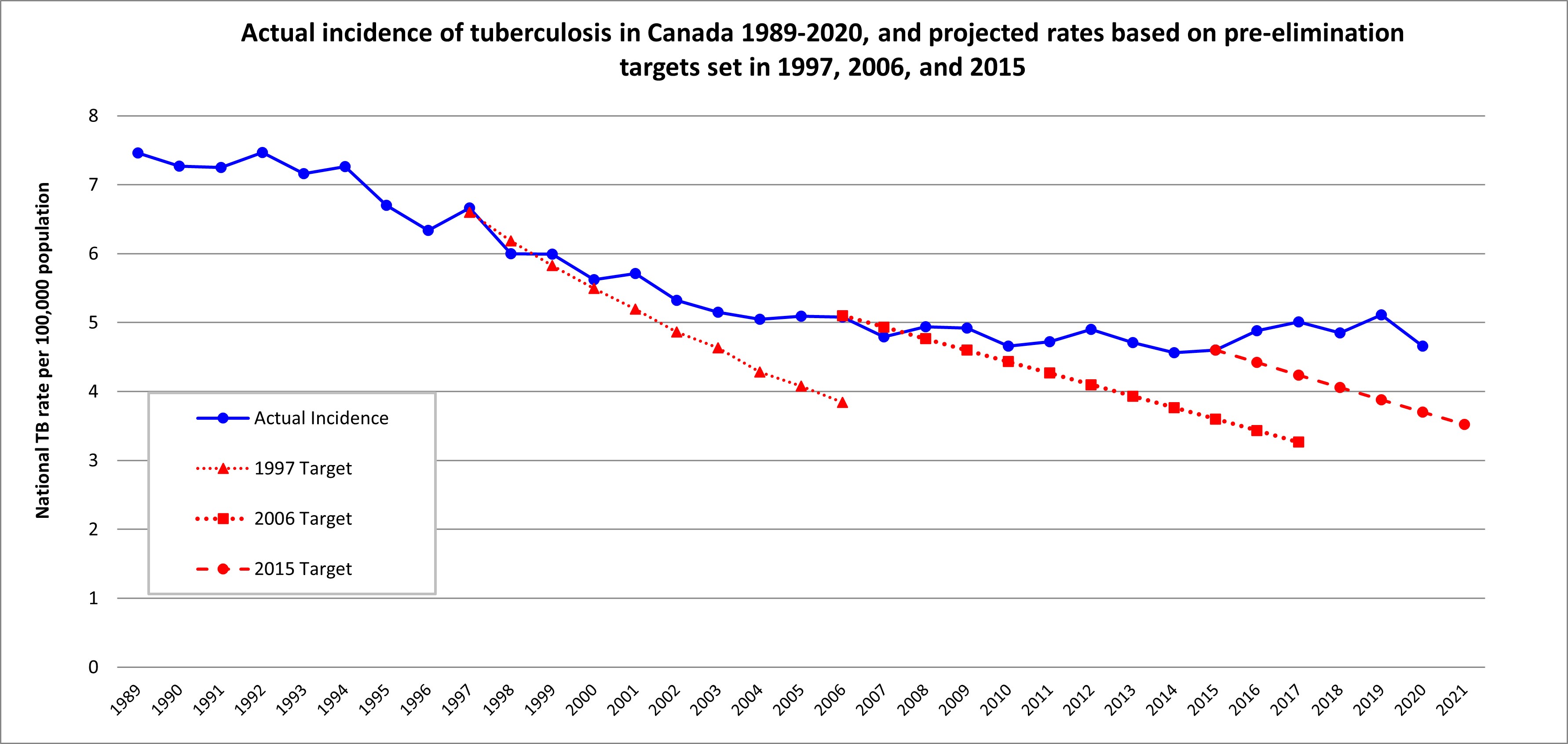

Although the importance of TB program performance monitoring in Canada has been discussed for more than 20 years, notably by Health Canada, the pan-Canadian Public Health Network and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, a national framework does not yet exist.Reference 13Reference 14Reference 15Reference 16Reference 17 In the same period, a substantial reduction in cases has not been achieved, with the overall annual incidence of TB in Canada remaining flat for 16 years, as in Figure 1 (see Chapter 1: Epidemiology of tuberculosis in Canada).

Actual incidence: Reported cases from the Notifiable diseases on-line (PHAC)Reference 20 1924 to 2019 in Canada

1997 target: 5% annual reduction in casesReference 21

2006 target: Reach a target incidence of 3.6 by 2015. A linear relationship was plotted and extended beyond the 2015 goal.Reference 22

2015 target: Reduce new incident cases by 90% in 2035 as compared to 2015.Reference 4 Note that these case numbers are for Canada overall and differ for select populations within Canada.

Figure 1: Text description

| Year | Actual incidence (National TB rate per 100,000 population) | 1997 Target | 2006 Target | 2015 Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | 7.46 | - | - | - |

| 1990 | 7.27 | - | - | - |

| 1991 | 7.25 | - | - | - |

| 1992 | 7.47 | - | - | - |

| 1993 | 7.16 | - | - | - |

| 1994 | 7.26 | - | - | - |

| 1995 | 6.70 | - | - | - |

| 1996 | 6.34 | - | - | - |

| 1997 | 6.66 | 6.60 | - | - |

| 1998 | 6.00 | 6.18 | - | - |

| 1999 | 5.99 | 5.83 | - | - |

| 2000 | 5.62 | 5.50 | - | - |

| 2001 | 5.71 | 5.19 | - | - |

| 2002 | 5.32 | 4.86 | - | - |

| 2003 | 5.15 | 4.63 | - | - |

| 2004 | 5.05 | 4.28 | - | - |

| 2005 | 5.09 | 4.08 | - | - |

| 2006 | 5.08 | 3.84 | 5.10 | - |

| 2007 | 4.79 | - | 4.93 | - |

| 2008 | 4.94 | - | 4.77 | - |

| 2009 | 4.92 | - | 4.60 | - |

| 2010 | 4.66 | - | 4.43 | - |

| 2011 | 4.72 | - | 4.27 | - |

| 2012 | 4.90 | - | 4.10 | - |

| 2013 | 4.71 | - | 3.93 | - |

| 2014 | 4.56 | - | 3.77 | - |

| 2015 | 4.60 | - | 3.60 | 4.60 |

| 2016 | 4.88 | - | 3.43 | 4.42 |

| 2017 | 5.01 | - | 3.27 | 4.24 |

| 2018 | 4.85 | - | - | 4.06 |

| 2019 | 5.11 | - | - | 3.88 |

| 2020 | 4.66 | - | - | 3.70 |

| 2021 | - | - | - | 3.52 |

Meanwhile, performance indicators have been adopted in other settings to assess regional and national TB prevention and care services. For example, 1 study from the United States showed marked improvements in outcomes within local health regions that actively monitored and evaluated performance relative to those that passively collected data.Reference 18 In England, where a national standard of performance indicators exists, research has contributed to recommendations for new indicators to improve the overall quality and value of TB services within the context of elimination.Reference 19 In sum, program performance monitoring has been successful elsewhere, and this chapter provides recommendations for use by TB programs in Canada.

3. Design and limitations of a performance monitoring framework

In 2018, the National Collaborating Center for Infectious Diseases conducted a scoping review, compiling reports and TB program performance indicators from 25 distinct programs in other low-incidence countries and regions as well as for 3 TB-affected population groups in Canada: First Nations, Inuit and foreign-born populations. Analysis of these documents led to a list of 105 program performance indicators with potential applicability to Canada. That same year, those indicators were discussed at a national meeting and ranked using a modified Delphi technique.Reference 23Reference 24 The meeting concluded with expert consensus achieved on 8 core indicators of TB program performance relevant to the aforementioned priority populations.Reference 17Reference 24

These eight core indicators were reviewed by all of the authors of this chapter with additions made during facilitated discussion to produce a more generalizable tool. The end result is a framework of twelve indicators (see Table 1) that can be used to evaluate TB services across Canada.

| Indicator number | Key indicator | Definition | Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elimination goals | |||

| 1.0 | Total annual incidence (crude) rate of tuberculosis (TB), all forms | The total number of people notified with TB in the jurisdiction, expressed as a rate per 100,000 population | Pre-elimination target set at an active case rate of 1/100,000 or, as above, 10/1,000,000 population by 2035 |

| Objectives for examination of immigrants and refugees | |||

| 2.0 | Of people whose immigration medical examination (IME) indicated follow-up, the proportion (%) of individuals who are evaluated by a TB clinician | The total number of appointments attended among persons whose IME led to a referral to public health for medical surveillance of TB | >90% |

| Objectives for case management and treatment | |||

| 3.0 | Of all people with new, relapse, or retreatment TB, proportion (%) with known human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status | The number of people with annual incident TB whose HIV status is known at the start date of treatment | ≥95% |

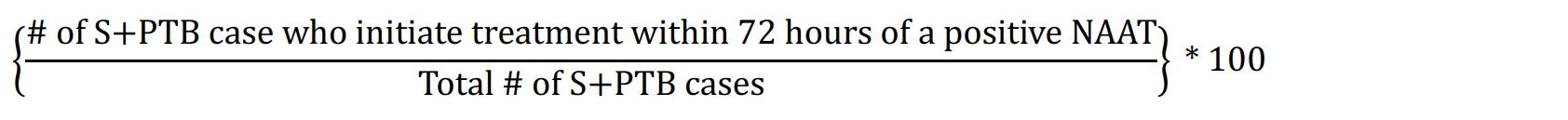

| 3.1 | Of all people with smear-positive, pulmonary TB, proportion (%) started treatment within 72 hours of positive nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) | The number of people with annual incident, smear-positive pulmonary TB who are started on anti-TB drugs within 72 hours of a positive NAAT result | ≥95% |

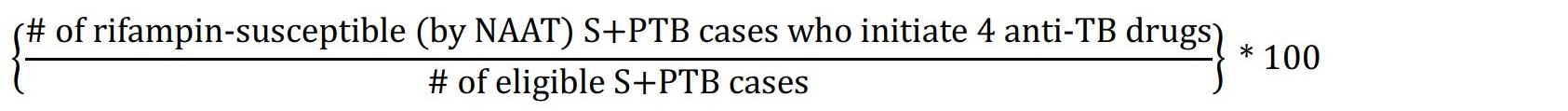

| 3.2 | Of all people with smear-positive, pulmonary TB, proportion (%) started on 4 or more anti-TB drugs to which they are likely to be susceptibleTable 1 Footnote a | The number of people with annual incident smear-positive, rifampin-susceptible (by NAAT), pulmonary TB who start 4 anti-TB drugs in the absence of any risk factors for resistance, or hepatoxicity | ≥95% |

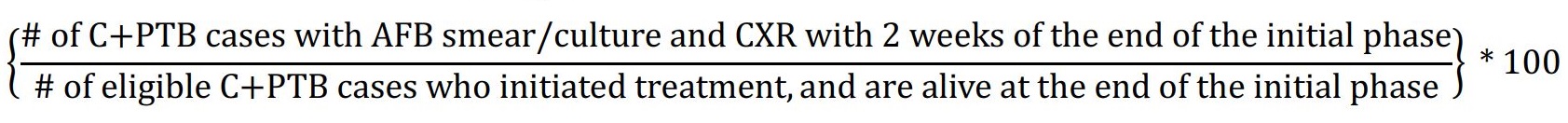

| 3.3 | Of all people with culture positive, pulmonary TB, proportion (%) with sputum submitted for acid fast bacillus (AFB) smear/culture, and a chest radiograph (CXR) at the end of the initial phase of treatment | The number of people with annual incident culture-positive, pulmonary TB who have sputum submitted for AFB smear and culture, and have a CXR performed within 2 weeks of the end of the initial phase of treatment | ≥95% |

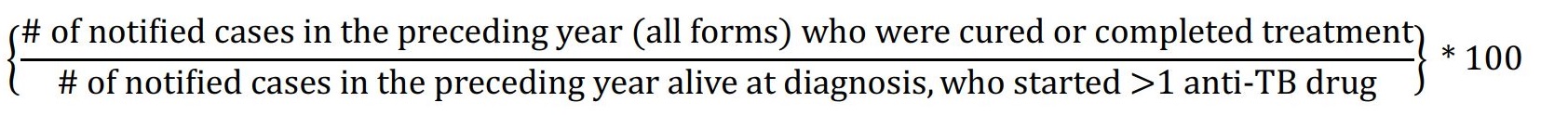

| 3.4 | Of all patients who started treatment for active disease in the preceding 12 months, the proportion (%) who achieved treatment success (cure or completed)Table 1 Footnote b | The proportion of patients notified in the preceding 12 months who were cured or completed treatment | ≥90% |

| 3.5 | Does the TB program have dedicated social worker support to provide patient-centered care? | TB disease is considered a biologic expression of social inequity, thereby requiring solutions that consider social and structural factors* *See text below for more details. |

Yes |

| Objectives for contact management | |||

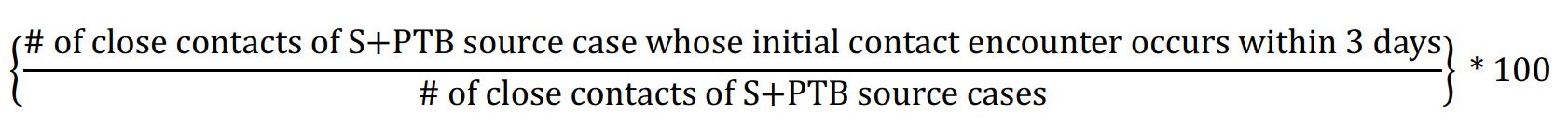

| 4.0 | Of all close contacts of people with smear-positive, pulmonary TB, proportion (%) whose initial contact encounter is within 3 working days of having been listed as a contact | The number of close contacts of people with smear-positive, pulmonary TB, whose initial contact encounter occurred within 3 working days of having been named as a contact | ≥95% |

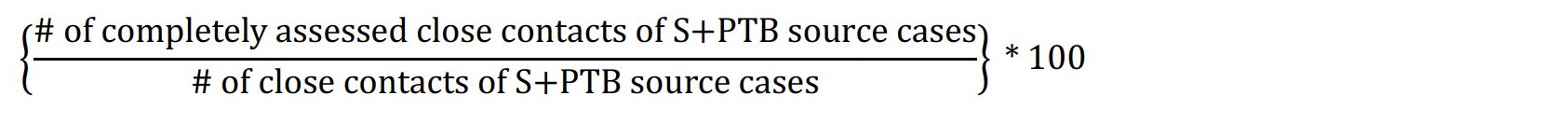

| 4.1 | Of all close contacts of people with smear-positive, pulmonary TB, proportion (%) completely assessed | The number of close contacts (household and non-household) of people with smear-positive, pulmonary cases, whose assessments are completed | ≥95% |

| 4.2 | Of all close contacts of people with smear-positive, pulmonary TB with a diagnosis of latent TB infection (LTBI), proportion (%) who began treatment | The number of close contacts of people with smear-positive, pulmonary TB with a diagnosis of LTBI who initiate preventive therapy within 12 months of source diagnosis | ≥90% |

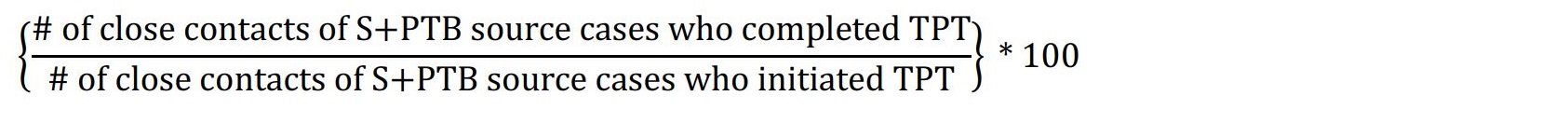

| 4.3 | Of all close contacts of people with smear-positive, pulmonary TB with a diagnosis of LTBI, proportion (%) completed treatment | The number of close contacts of people with smear-positive, pulmonary TB who complete treatment with TB preventive therapy after initiating | ≥90% |

|

Footnotes:

|

|||

The resulting framework comprises program performance indicators (actions) that are largely pragmatic and judged to adhere to the following criteria: relevant, well-defined, reliable, technically feasible, practical and have a history of use elsewhere.Reference 25 It is, however, not without limitation. For example, TB programs in provinces and territories that have a high proportion of foreign-born persons may ultimately perform well across most or all program performance indicators, but see limited reduction of incidence.Reference 26Reference 27 This is because replenishment of the reservoir of TB infections may continually occur among those from high-TB-incidence nations.Reference 28Reference 29Reference 30Reference 31 (see Chapter 13: Tuberculosis surveillance and tuberculosis testing and treatment in migrants). Implementing this framework will require dedicated human resources with requisite qualifications to properly compile and report these data. This investment is justified, as program performance monitoring produces valuable information for programmatic improvement, strengthens program management activities, improves accountability and generates evidence of the value of TB services.Reference 11Reference 18Reference 32

4. Core program performance indicators

This program performance monitoring framework includes 12 indicators, with accompanying targets. In the absence of preexisting national data, targets were set to strike a balance between being achievable and motivational based on expert guidance. Future iterations of this nationally applicable framework should adjust these targets based on actual performance.

Overall, this initial performance monitoring framework focuses on the management of patients with smear-positive pulmonary TB and their contacts, as these groups are considered the highest priorities for optimal program performance. Indicators are grouped according to the following goals/objectives.

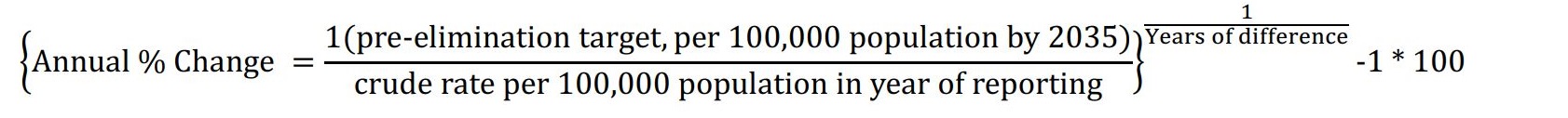

4.1. Elimination

The goals for pre-elimination and elimination are set in Canada's international commitments and programs should be monitoring their own year-on-year progress toward meeting them. The pre-elimination target for low-incidence settings is an active case rate of 10/1,000,000 population by 2035, while the elimination target is 1/1,000,000 population by 2050 at the national level. Progress toward elimination depends on achieving a rate of decline that aligns with those targets, but will be influenced by the local epidemiology of TB in the populations served by the program. As a result, the rate of decline will vary by the reporting program.

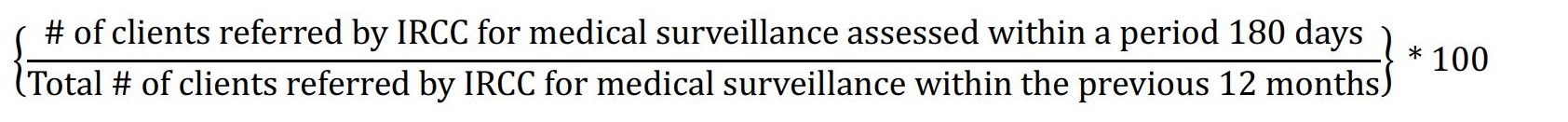

4.2. Objectives for examination of immigrants and refugees

Foreign-born persons contribute the highest absolute number and proportion (>70%) of TB cases in Canada, which creates pressure on the pace of decline that can be achieved domestically. Therefore, programs should give priority to managing Immigration Medical Exam referrals (see Chapter 13: Tuberculosis surveillance and tuberculosis testing and treatment in migrants).Reference 26Reference 33

4.3. Objectives for case management and treatment

Timely diagnosis of, and effective treatment initiation in, people with pulmonary TB is paramount in preventing the transmission of TB, and to prevent further morbidity and mortality for these individuals. Maximizing successful treatment (cure or treatment completed) while minimizing unsuccessful treatment outcomes (TB-related death, treatment non-completion loss to follow-up) are key outcomes. In addition, the psycho-social and behavioral needs of people affected by TB may influence local epidemiology and individual outcomes. Addressing these issues is central to the program's ability to provide patient-centered care (see Chapter 5: Treatment of tuberculosis disease).

4.4. Objectives for contact management

Preventing the reactivation of latent TB infections is an equally crucial component of TB elimination, particularly for priority contacts — that is, close contacts of persons with smear-positive, pulmonary TB (see Chapter 11: Tuberculosis contact investigation and outbreak management).

The calculations for each indicator tabulate the number of times the action was completed out of the number of times it was applicable, displayed as a proportion.Reference 34 These proportions are then compared quantitatively to defined targets. Definitions of these actions and targets are provided in Table 1, while methods for analysis and reporting are provided in Table 2.

5. Analytic and action strategies

Table 2 describes how to measure and analyze performance of TB programs based on the indicators in this framework. This analytic strategy is separate from the clinical care of patients, which is covered in other chapters of these standards.

5.1. Reporting schedule

Performance monitoring will be achieved by completing reports on the indicators presented here, according to the formulas provided in Table 2. Program performance indicators for the immediate past calendar year should be reported in February or March of the current year, except for treatment outcomes of all patients diagnosed with TB disease in the previous calendar year, which can be reported only a full year after. Annual program performance reports should be discussed with appropriate local public health representatives and community partners to ensure accountability, determine whether and how actions should be changed to improve outcomes and contextualize the information in a culturally-safe manner.Reference 35 Program managers (leads) are best positioned to implement change. This makes it crucial that program managers oversee the process and develop a mechanism to properly engage stakeholder groups.Reference 36 Annual summary reports should be published online to promote transparency and contribute to benchmarking efforts across the country.

Implementation of this program performance monitoring framework includes the completion of annual reports (to assess local performance over time) that are consistent across jurisdictions (to assess relative performance). Timely completion and sharing of these reports will help minimize delays in making program improvements. TB programs should allocate adequate human resources for data collection and validation to monitor these indicators. Validation should be performed in close collaboration with the physician/ nursing leads and relevant community partners.

Table 2. Calculating and presenting TB program performance indicators

| Indicator number | How to calculate performance for reporting |

|---|---|

| Goal of elimination | |

| 1.0 | Numerator: Number of TB cases who are notified in the jurisdiction between January 1 and December 31, inclusive. Denominator: Total mid-year population estimate. Formula:

In addition, calculate the necessary annual rate of decline to achieve pre-elimination within the jurisdiction (see below) where "years of difference" is the period between the year of reporting and 2035 and the target of 1 is the numerator.  |

| Objectives for examination of immigrants and refugees | |

| 2.0 | Numerator: Number of Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) referrals dating from July 1 of the preceding year whose first appointment by a physician or designated public health specialist was achieved within six months of the date the referral was received. Denominator: Total number of IRCC referrals to the public health authority in the jurisdiction between July 1 and June 30. Formula:  |

| Objectives for case management and treatment | |

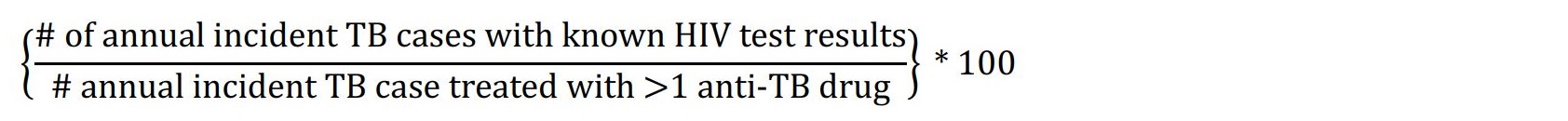

| 3.0 | Numerator: Number of TB cases notified between January 1 and December 31 whose human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status is known at the commencement of treatment. Denominator: Total number of TB cases treated. Formula:

HIV results include the following possibilities:

|

| 3.1 | Numerator: Number of smear-positive (S), pulmonary TB (PTB) cases notified between January 1 and December 31 who initiate treatment within 72 hours of a positive nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). Denominator: Total number of smear-positive, pulmonary TB cases. Formula:  |

| 3.2 | Numerator: Number of eligible smear-positive (S), rifampin-susceptible (by nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT)) pulmonary TB (PTB) cases notified between January 1 and December 31 who start four anti-TB drugs. Denominator: Total number of eligible TB cases treated. Exclusions: Patients judged to be at high risk for hepatoxicity, gout, and/or have a history of overt exposure to a source case who is known to have had drug resistant TB (any first-line anti-TB drug), and patients who have been previously treated will not count in the numerator or denominator. Formula:  |

| 3.3 | Numerator: Number of all culture positive (C), pulmonary TB (PTB) cases who have sputum submitted for acid fast bacillus (AFB) smear/culture, and a chest radiograph (CXR) within two weeks of the end of the initial phase of treatment. Denominator: Total number of culture-positive pulmonary TB cases who are alive and not transferred out at the end of the initial phase of treatment. Exclusions: Patients who die during the initial phase and/or transfer out of the jurisdiction before the end of the initial phase will not count in the numerator or denominator. Formula:  |

| 3.4 | Numerator: Number of annual incident TB cases notified in the preceding 12 months who were cured or completed treatment. Denominator: Total number of annual incident TB cases notified in the preceding 12 months who were alive at diagnosis, and who started ≥ one anti-TB drug. Exclusions: Patients with rifampin resistance, patients whose treatment was initiated in another Canadian jurisdiction (transferred in), and patients who have transferred out of country during treatment are excluded from the numerator and denominator. Formula:  |

| 3.5 | Does the TB program have dedicated social worker support? If yes, their performance should be monitored according to the objective needs of patients and clients in the jurisdiction (See section 5.3 for examples). If no, the program, under the direction of the program manager/lead, should define the objective needs of underserved patients and clients in the program to advocate for dedicate social worker support. |

| Objectives for contact management | |

| 4.0 | Numerator: Number of close (household and non-household) contacts of smear-positive (S) pulmonary TB (PTB) cases notified between January 1 and December 31 whose initial contact encounter was within 3 working days of the contact having been listed. Denominator: Total number of close contacts of annual incident smear-positive pulmonary TB cases. Formula:  |

| 4.1 | Numerator: Number of close (household and non-household) contacts of smear-positive (S) pulmonary TB (PTB) cases notified between January 1 and December 31 who are completely assessed.Table 2 Footnote a Denominator: Total number of close contacts of annual incident smear-positive, pulmonary TB cases. Formula:  |

| 4.2 | Numerator: Number of close (household and non-household) contacts of smear-positive pulmonary TB cases notified between January 1 and December 31 eligible for TB preventive therapy (TPT) who initiate treatment. Denominator: Total number of close contacts of annual incident smear-positive pulmonary TB cases, who are eligible for TPT. Formula:  |

| 4.3 | Numerator: Number of close (household and non-household) contacts of smear-positive (S) pulmonary TB (PTB) cases notified between January 1 and December 31 eligible for TB preventive therapy (TPT) who initiated and complete treatment Denominator: Total number of close contacts of annual incident smear-positive pulmonary TB cases, eligible for TPT who initiated treatment of latent TB infection. Formula:  |

|

Footnotes:

|

|

5.2. Recommended demographic, clinical and social variables

It is recommended that data be analyzed by age, sex/gender and population group to maintain a focus on where there is greatest need for TB services and care and where inequities can be mitigated. These levels of disaggregation align with international and Canadian standards for sex- and gender-based analysis of health data.Reference 37Reference 38Reference 39Reference 40Reference 41 Depending on local decisions for programs to collect or link with other data, analyses can also include other significant social strata of risk, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status, persons experiencing homelessness, persons with limited labor participation and/or high-risk occupations and persons currently or recently incarcerated.

5.3. Role of social work in addressing patient and client needs

Responses to TB-associated social risk factors should be addressed by a dedicated TB-program social worker; the ability of programs to do this should be monitored. Among communicable infectious diseases, TB in particular illustrates how structural barriers imposed by racism, classism and colonialism in Canada require political commitment to make health systems available and accessible to all (see Chapter 12: An introductory guide to tuberculosis care serving Indigenous peoples and Chapter 13: Tuberculosis surveillance and tuberculosis testing and treatment in migrants).Reference 42Reference 43 At the same time, psycho-social, behavioral and biological considerations complicate TB disease and its management (e.g., substance use disorders, contact network structures, HIV/AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome), diabetes, undernutrition).Reference 44Reference 45Reference 46Reference 47Reference 48Reference 49Reference 50Reference 51Reference 52Reference 53Reference 54Reference 55 Because the specific tasks of the dedicated TB-program social worker may vary, programs can assess the impact of this support in various ways, including: 1) reporting the proportion of patients connected to a primary care provider by the end of TB care; 2) reporting the proportion of patients experiencing homelessness who are adequately housed by the end of TB care; and 3) assessing housing conditions among patients with infectious TB.

6. Summary

In a federation, meeting the challenge of TB elimination is made more difficult by inherent differences in the delivery of health services across the country. Accordingly, each province and territory contributes parts of what, in sum, constitutes the national response. Every person with active TB in Canada matters, and by committing to the aspirational End TB targets, there is a recognition that every prevented case counts more than ever. The purpose of this chapter is to encourage TB program leads and staff to provide evidence to communities, the public at large, health authorities and governments of progress toward desired outcomes. The core program performance indicators described in this chapter are considered the minimum standard for all programs.

Disclosure statement

The Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS) TB Standards editors and authors declared potential conflicts of interest at the time of appointment and these were updated throughout the process in accordance with the CTS Conflict of Interest Disclosure Policy. Individual member conflict of interest statements are posted on the CTS website.

Funding

The 8th edition Canadian Tuberculosis Standards are jointly funded by the CTS and the Public Health Agency of Canada, edited by the CTS and published by the CTS in collaboration with the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease (AMMI) Canada. However, it is important to note that the clinical recommendations in the Standards are those of the CTS. The CTS TB Standards editors and authors are accountable to the CTS Respiratory Guidelines Committee (CRGC) and the CTS Board of Directors. The CTS TB Standards editors and authors are functionally and editorially independent from any funding sources and did not receive any direct funding from external sources.

The CTS receives unrestricted grants which are combined into a central operating account to facilitate the knowledge translation activities of the CTS Assemblies and its guideline and standards panels. No corporate funders played any role in the collection, review, analysis or interpretation of the scientific literature or in any decisions regarding the recommendations presented in this document.

Appendix 1: Monitoring tuberculosis program performance

The framework for monitoring tuberculosis program performance outlined in Chapter 15 consists of 12 program performance indicators; a rationale for each is provided below along with international and national history of use or recommendation precedents. As in the text, in 2018, the National Collaborating Center for Infectious Diseases performed a scoping review of TB program performance indicators in epidemiologically similar settings (high-income, low-TB incidence) coupled with general global recommendations. Indicators were selected from this review. As shown in the following data, more recent recommendations and strategies have been reviewed in preparation of this chapter for a history of use. This list of prior use/recommendation is representative, and not exhaustive.

Abbreviations: NCCID, National Collaborating Center for Infectious Diseases; WHO, World Health Organization; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; FNIHB, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch; ROI, return on investment; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; P/T, provincial and territorial; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; CI, confidence interval; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; TST, tuberculin skin test; AFB, acid fast bacillus; CXR, chest radiograph; ITK, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami; 4R, daily rifampin for 4 months; 9INH, 9-month daily isoniazid regimen; TPT, tuberculosis preventive treatment; LTBI, latent tuberculosis infection.

Goal of elimination: Indicator, target and rationale

1.0 Crude incidence rate of TB: all forms

Target: Report incidence, and rate of decline.

Rationale: this is the hard target of pre-elimination and elimination. this measurement establishes the ultimate standard by which the program is performing. Incidence should be monitored and reported annually to inform effective mid-course changes on the path to elimination.Reference 56Reference 57 Canada is responsible for reporting national and subnational data to the global community; therefore, these data should be accessible and reportable.Reference 58

Notes: Program leads should establish a rate of decline that is adequate to achieve elimination targets.

Recommended internationally by: WHO - Compendium of Indicators for Monitoring and Evaluation of National Tuberculosis Control Programs;Reference 56 CDC - National Tuberculosis Program Objectives and Performance Targets for 2025;Reference 59 Australia - The Strategic Plan for Control of Tuberculosis in Australia 2011-2015, and National Tuberculosis Performance Indicators, Australia 2013-2014;Reference 5Reference 60 Public Health England - Public Health England Tuberculosis Strategy Monitoring Indicators 2015-2020 (three-year average);Reference 7 Alaska - Alaska Department of Health and Social Services TB Manual;Reference 61 Minnesota - Tuberculosis (TB) Prevention and Control Program;Reference 62 and California - CID TB Performance Trends for US, California Objectives.Reference 63

Recommended for Canada by: Pan-Canadian Public Health Network - Guidance for Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Programs in Canada;Reference 15 FNIHB - Health Canada Strategy against Tuberculosis for First Nations on-Reserve and Monitoring and Performance Framework;Reference 13Reference 14 Inuit Tuberculosis Elimination Framework;Reference 16 Heffernan & Long - Would program performance indicators and a nationally coordinated response accelerate tuberculosis elimination in Canada?;Reference 64 and NCCID - Toward TB Elimination: Shared Priorities for TB Program Performance Measurement in Canada, a Proposal for Discussion.Reference 17

Objectives for examination of immigrants and refugees: Indicator, target and rationale

2.0 Proportion of individuals referred for immigration medical surveillance who are evaluated by physician

Target: ≥90%

Rationale: Foreign-born persons contribute the absolute highest number of total cases identified in Canada (now >70% nationally), creating pressure on the pace of decline that can be achieved domestically.Reference 26Reference 33 A systematic and meta-review of TB incidence among migrants deemed 'high-risk' in pre-migration screening reported an elevated incidence of active disease in this group. The pooled cumulative incidence of TB post-migration in the study population from 22 cohorts was 2,794 per 100,000 persons (95% CI 2179-3409; I2 = 99%). The pooled cumulative incidence of TB at the first follow-up visit from ten cohorts was 3,284 per 100,000 persons (95% CI 2173-4395; I2 = 99%). The pooled TB incidence from 15 cohorts was 1,249 per 100,000 person-years of follow-up (95% CI 924-1574; I2 = 98%).Reference 65 There is recent debate about whether the phenotypic expression of disease in newcomers poses a significant public health risk, suggesting that the risk of in-country transmission is limited compared to the risk of transmission by people who develop reactivation pulmonary disease from undetected LTBI on arrival.Reference 28Reference 66 As a result, this indicator alone is insufficient for long-term reduction of TB in foreign-born persons. Although referral of foreign-born persons to public health for medical surveillance is understood to be minimalReference 67 in contributing to elimination, targeted screening for LTBI among immigrants and refugees arriving in Canada has not yet reached its potential.

Notes: Despite the limitations, this performance indicator is a measurable aspect of TB prevention and care services and helps generate evidence in support of value (ROI).

Recommended internationally by: CDC - National Tuberculosis Program Objectives and Performance Targets for 2025;Reference 59 California - CID TB Performance Trends for US, California ObjectivesReference 63; and Public Health England - Public Health England Tuberculosis Strategy Monitoring Indicators 2015-2020.Reference 61

Recommended for Canada by: Pan-Canadian Public Health Network - Guidance for Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Programs in Canada;Reference 15 Heffernan & Long - Would program performance indicators and a nationally coordinated response accelerate tuberculosis elimination in Canada?.Reference 64 Chapter 15 of the sixth Edition of the Canadian Tuberculosis Standards, Immigration and Tuberculosis Control in Canada records an evaluation of compliance on this indicator done at the national level (average performance reported to be about 50% at the time).Reference 68

Objectives for case management and treatment: Indicator, target and rationale

3.0 Proportion of all new, relapse, or re-treatment TB cases whose HIV status is known

Target: ≥95%

Rationale: A diagnosis of HIV, independent of TB, has individual and public health implicationsReference 69 and, in the event of co-infection, has implications for treatment. In Alberta, where >90% of TB patients are HIV tested (attributable to an opt-out strategy), nearly 50% of HIV infections are discovered at the time of a TB diagnosis.Reference 70 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of the adoption of indicator condition-guided HIV testing in Western nations showed that there has been scarce reporting of HIV testing of TB patients in Canada (4/28 articles), with variability in achievement ranging from 53.6 to 90.6% known HIV status during TB treatment. This indicates both a greater need for reporting as well as implementation of strategies to improve adherence to recommendations at the program level.Reference 71

Notes: The target is to offer an HIV test to all incident TB cases if HIV status is unknown at the time of diagnosis, 100% of the time; it is understood that the rate of acceptance will be lower.

Recommended internationally by: WHO - Compendium of Indicators for Monitoring and Evaluating National Tuberculosis Programs;Reference 56 Horsburgh et al. - Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Tuberculosis;Reference 34 WHO - End TB Strategy;Reference 4 WHO/UNAIDS - Guide to Monitoring and Evaluation for Collaborative TB/HIV activities;Reference 72 Australia - The Strategic Plan for Control of Tuberculosis in Australia 2011-2015, and National Tuberculosis Performance Indicators, Australia 2013-2014;Reference 5Reference 60 Public Health England - Public Health England Tuberculosis Strategy Monitoring Indicators 2015-2020 (three-year average);Reference 7 Alaska - Alaska Department of Health and Social Services TB Manual;Reference 61 and, California - CID TB Performance Trends for US, California Objectives.Reference 63

Recommended for Canada by: Canadian Tuberculosis Directors of Canada and the Department of National Health and Welfare in consultation with P/T epidemiologists - Guidelines for the identification, investigation and treatment of individuals with concomitant tuberculosis and HIV infection;Reference 73 Canadian Tuberculosis Committee, Health Canada - Recommendations for screening and prevention of tuberculosis in patients with HIV and for screening for HIV in patients with tuberculosis and their contacts;Reference 74 Pan-Canadian Public Health Network - Guidance for Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Programs in Canada;Reference 15 and Haworth-Brockman & Keynan - Strengthening tuberculosis surveillance in Canada.Reference 75

3.1 Proportion of all smear-positive, pulmonary cases who start treatment within 72 hours of positive NAAT

Target: ≥95%

Rationale: Timely treatment initiation provides an individual benefit by limiting increased risk of complications associated with delay as well as a public health benefit, by rapidly reducing infectivity.Reference 76 A prospective cohort study in the United States found an increased risk of transmission to close contacts (outcome = TST positivity) of US-born patients who experienced a delay in treatment initiation ≥90 days (40%) vs those who had a shorter delay in treatment initiation (24%) (aOR 2.34; p = 0.03), and increasing to (aOR 3.29; p = 0.01) among close contacts of US-born patients sputum smear-positive for AFB and whose treatment initiation was delayed.Reference 77 Accordingly, rapid initiation of anti-TB drugs for pulmonary cases is a priority, and program performance should be leading in these patients.

Notes: The indicator and related target here is to initiate treatment rapidly (within 3 days), ≥95% of the time. This choice was based on the proficiency turnaround time expectation for labs to perform, and report results of the test within 24 hours of submission. Two additional days are proposed to allow for the possibility that notification of a positive NAAT may occur at the beginning of a long weekend.

Recommended internationally by: CDC - National Tuberculosis Program Objectives and Performance Targets for 2025;Reference 59 Alaska - Alaska Department of Health and Social Services TB ManualReference 61; and California - CID TB Performance Trends for US, California Objectives.Reference 63

Recommended for Canada by: Pan-Canadian Public Health Network - Guidance for Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Programs in Canada.Reference 15

3.2 Proportion of smear-positive pulmonary cases who start four or more anti-TB drugs

Target: ≥95%

Rationale: Rapid initiation of anti-TB drugs, especially for smear-positive pulmonary cases, is critical to reduce infectivity and interrupt transmission.Reference 76Reference 78 Given this reality, and in light of the delays associated with obtaining drug susceptibility test results, the greater individual and public health benefits derive from initiating empiric treatment among those infectious cases without risk factors for resistance, suspicion of hepatoxicity or gout. Of note, in Canada, drug resistance is a relatively infrequent phenomenon, but there is variability in the regional epidemiology of drug-resistant forms of TB that could contribute to more frequent exceptions to the numerator that some programs can anticipate.Reference 79

Recommended internationally by: CDC - National Tuberculosis Program Objectives and Performance Targets for 2025;Reference 59 and Public Health England - Public Health England Tuberculosis Strategy Monitoring Indicators 2015-2020.Reference 7

Recommended for Canada by: Pan-Canadian Public Health Network - Guidance for Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Programs in Canada;Reference 15 FNIHB/Health Canada - Strategy against Tuberculosis for First Nations on-Reserve, and related Monitoring and Performance Framework; Reference 13Reference 14 NCCID - Toward TB Elimination: Shared Priorities for TB Program Performance Measurement in Canada, a Proposal for Discussion;Reference 17 and Heffernan & Long - Would program performance indicators and a nationally coordinated response accelerate tuberculosis elimination in Canada?Reference 64

3.3 Proportion of all culture-positive pulmonary cases who have sputum submitted for AFB smear/culture, and a CXR at the end of the initial phase of treatment

Target: ≥95%

Rationale: Sputum culture-conversion at the end of the initial phase is understood to be a good predictor of eventual cure; more significantly, there are implications for treatment.Reference 56 Sustained culture positivity, or having unclosed cavitation on CXR at the end of the initial phase of treatment, may be suggestive of treatment failure/relapse and induced drug resistance.Reference 80 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of sputum conversion during effective treatment found 12, and 41% of persons with smear-positive disease, remained solid and liquid culture-positive, respectively, at the end of the initial phase of treatment but sub-group analyses by important covariates known to be independently associated with sputum conversion, such as HIV status, and cavitation, were limited.Reference 81 Monitoring adherence to best clinical practice provides useful information to the program relating to efforts that ostensibly improve treatment outcomes by reducing risk of relapse.

Recommended internationally by: WHO - Compendium of Indicators for Monitoring and Evaluation of National Tuberculosis Control Programs;Reference 56 California - CID TB Performance Trends for US, California Objectives;Reference 63 and CDC - National Tuberculosis Program Objectives and Performance Targets for 2025.Reference 59

Recommended for Canada by: Pan-Canadian Public Health Network - Guidance for Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Programs in Canada;Reference 15 and FNIHB/Health Canada - Strategy against Tuberculosis for First Nations on-Reserve, and related Monitoring and Performance Framework.Reference 13Reference 14

3.4 Treatment success (cure or completed) within 12 months of starting treatment

Target: ≥90% of cases

Rationale: Treatment success (cure or completed) is essential to eliminating TB by preventing transmission, disease severity and death. Incomplete treatment or loss to follow-up can lead to drug resistance and transmission to others. A 1991 World Health Assembly resolution established a global target for treatment success to be 85%, but in low-HIV-prevalence settings with universal health coverage, a higher rate of achievement should be possible.Reference 82

Recommended internationally by: WHO - Compendium of Indicators for Monitoring and Evaluation of National Tuberculosis Control Programs;Reference 56 CDC - National Tuberculosis Program Objectives and Performance Targets for 2025;Reference 59 Australia - The Strategic Plan for Control of Tuberculosis in Australia 2011-2015, and National Tuberculosis Performance Indicators, Australia 2013-2014;Reference 5Reference 60 WHO - End TB StrategyReference 4; Alaska - Alaska Department of Health and Social Services TB Manual;Reference 61 Minnesota - Tuberculosis (TB) Prevention and Control Program;Reference 62 and California - CID TB Performance Trends for US, California Objectives.Reference 63

Recommended for Canada by: Pan-Canadian Public Health Network - Guidance for Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Programs in Canada;Reference 15 FNIHB/Health Canada - Health Canada Strategy against Tuberculosis for First Nations on-Reserve and Monitoring and Performance Framework;Reference 13Reference 14 ITK - Inuit Tuberculosis Elimination Framework;Reference 16 and Heffernan & Long - Would program performance indicators and a nationally coordinated response accelerate tuberculosis elimination in Canada?Reference 64

3.5 Does the TB program have dedicated social worker support?

Target: Yes

Rationale: This chapter recommends that TB programs have dedicated support of a social worker, and that their associated workflow be evaluated. Some examples of possible measurements of the social worker's performance include: the proportion of patients who are connected to a primary care provider by the end of TB care; the proportion of patients experiencing homelessness, or are underhoused, who are adequately housed through their efforts; monitoring of patients who report crowded housing. The objective psycho-social needs of clients and patients may vary by jurisdiction, and should be clearly defined by the program manager/lead.

Recommended by: A specific program performance indicator about whether TB programs have dedicated social worker support could not be located. Recommendations, however, to meet the psycho-social needs of patients and clients who suffer the effects of TB infection and disease are common, but practical guidance about how to achieve this remains limited.Reference 83 As a result, this indicator is included as a means to generate information about the practical steps programs take to address the impacts of structural, and social determinants of health in the lives of clients/patients served.

Objectives for contact management: Indicator, target and rationale

4.0 Proportion of close contacts of persons with smear-positive pulmonary disease whose initial contact encounter occurs within 3 working days

Target: ≥95%

Rationale: TB programs in Canada generally rely on a stone-in-pond method for unmasking evidence of transmission among contacts of persons with pulmonary TB.Reference 84 This method is considered favorable when the relative risk of transmission to contacts is higher than the risk of infection in the general public.Reference 84Reference 85 A public health benefit of timely contact investigations is limiting transmission into broader circles of contact.Reference 86 The rapid identification and initial encounter of close contacts of infectious source cases provides a mechanism for prioritization. A modification to stone-in-pond is the rapid assessment (prioritization) of vulnerable contacts (young children, and persons with immunocompromising conditions, notably HIV) who have been shown to be at risk of very rapid progression to disease.Reference 87Reference 88

Notes: Three days is considered timely and reasonable, but also somewhat arbitrary.Reference 86 The purpose is to monitor with the ambition to meet and exceed the target, redirecting efforts if underperforming.

Recommended internationally by: CDC - Guidelines for the investigation of contacts of patients with infectious tuberculosis: Recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and the CDC.Reference 86

Recommended for Canada by: Chapter 12 of the seventh Edition of the Canadian Tuberculosis Standards, Contact follow-up and outbreak management in tuberculosis control.Reference 89

4.1 Proportion of close contacts of persons with smear-positive pulmonary disease who are completely assessed

Target: ≥95%

Rationale: Prevention of reactivation TB is equally important to appropriate case management, especially of infectious cases, in its contribution to pre-elimination and elimination goals.

Recommended internationally by: WHO - End TB Strategy;Reference 4 CDC - National Tuberculosis Program Objectives and Performance Targets for 2025;Reference 59 and Public Health England - Public Health England Tuberculosis Strategy Monitoring Indicators 2015-2020 (in development).Reference 7

Recommended for Canada by: FNIHB/Health Canada - Strategy against Tuberculosis for First Nations on-Reserve, and related Monitoring and Performance Framework;Reference 12Reference 13 and Heffernan & Long - Would program performance indicators and a nationally coordinated response accelerate tuberculosis elimination in Canada?Reference 64

4.2 Proportion of close contacts of persons with smear-positive pulmonary disease eligible for TPT, who initiate treatment

Target: ≥90%

Rationale: LTBI is the seedbed of future cases but treatment of LTBI, in the absence of a risk of reinfection, is considered to be fully protective against reactivation TB.Reference 90Reference 91Reference 92Reference 93Reference 94Reference 95 As a result, pairing the prevention of reactivation with excellent infectious source case management work as hand-in-glove strategies to reduce future incidence of TB.Reference 49Reference 90

Notes: Targets are ambitious, but performance here and with respect to completion are likely to benefit from the current wealth of research aimed at reducing treatment duration and pill burden while maintaining efficacy and safety, as the expanded use of 4R compared to the long-standing 9INH has shown.Reference 96Reference 97

Recommended internationally by: WHO - End TB Strategy;Reference 4 CDC - National Tuberculosis Program Objectives and Performance Targets for 2025;Reference 59 and Public Health England - Public Health England Tuberculosis Strategy Monitoring Indicators 2015-2020 (in development).Reference 7

Recommended for Canada by: Pan-Canadian Public Health Network - Guidance for Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Programs in Canada;Reference 15 FNIHB/Health Canada - Health Canada Strategy against Tuberculosis for First Nations on-Reserve and related Monitoring and Performance Framework;Reference 13Reference 14 and Heffernan & Long - Would program performance indicators and a nationally coordinated response accelerate tuberculosis elimination in Canada?Reference 64

4.3 Proportion of close contacts of persons with smear-positive pulmonary disease who began, and completed, TPT for a diagnosis of LTBI

Target: ≥90%

Rationale: As above, successful treatment is protective against reactivation of TB (for the infection it is treating); success is a function of completion and strategies to facilitate completion are encouraged, especially for shorter regimens where each dose is a greater contributor to the effectiveness of the therapy.Reference 96Reference 97Reference 98Reference 99

Notes: As in 4.2.

Recommended internationally by: CDC - National Tuberculosis Program Objectives and Performance Targets for 2025.Reference 59

Recommended for Canada by: Pan-Canadian Public Health Network - Guidance for Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Programs in Canada;Reference 15 FNIHB - Health Canada Strategy against Tuberculosis for First Nations on-Reserve and Monitoring and Performance Framework;Reference 13Reference 14 NCCID - Toward TB Elimination: Shared Priorities for TB Program Performance Measurement in Canada, a Proposal for Discussion;Reference 17 and Heffernan & Long - Would program performance indicators and a nationally coordinated response accelerate tuberculosis elimination in Canada?Reference 64

References

- Reference 1

-

World Health Organization. Strategy for the control and elimination of tuberculosis. In: Implementing the WHO Stop TB Strategy: A Handbook for National Tuberculosis Control Programmes. Geneva: WHO Press; 2008.

- Reference 2

-

Cole B, Nilsen DM, Will L, Etkind SC, Burgos M, Chorba T. Essential Components of a Public Health Tuberculosis Prevention, Control, and Elimination Program: Recommendations of the Advisory Council for the Elimination of Tuberculosis and the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69(7):1-27. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6907a1.

- Reference 3

-

Uplekar M, Weil D, Lonnroth K, et al. WHO's new End TB Strategy. The Lancet. 2015;385(9979):1799-1801. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60570-0.

- Reference 4

-

World Health Organization. The End TB Strategy. https://www.who.int/tb/strategy/End_TB_Strategy.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed July 5, 2021.

- Reference 5

-

Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. The strategic plan for control of tuberculosis in Australia: 2011-2015. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. www1.health.gov.au. Accessed June 30, 2021.

- Reference 6

-

Degeling C, Carroll J, Denholm J, Marais B, Dawson A. Ending TB in Australia: Organizational challenges for regional tuberculosis programs. Health Policy. 2020;124(1):106-112. doi:10.1016/j.2019.11.009.

- Reference 7

-

Public Health England. Collaborative TB Strategy for England, 2015 to 2020: end of programme report. 2015. GW-1954.

- Reference 8

-

Pan American Health Organization. The End TB Strategy: Main Indicators in the Americas. 2020.

- Reference 9

-

Kritski A, Barreira D, Junqueira-Kipnis AP, et al. Brazilian Response to Global End TB Strategy: The National Tuberculosis Research Agenda. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2016;49:135-145. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0330-2015.

- Reference 10

-

Davidson EJ. Evaluative Reasoning. Methodological Briefs: Impact Evaluation. 2014;4:1-14.

- Reference 11

-

Coelho AA, Martiniano CS, Brito EWG, et al. Tuberculosis care: an evaluability study. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 2014;22(5):792-800. doi:10.1590/0104-1169.3294.2482.

- Reference 12

-

Centers for Disease Control. Framework for Program Evaluation in Public Health. MMWR. 1999;48(RR-11):1-40.

- Reference 13

-

Health Canada. Health Canada's Strategy against Tuberculosis for First Nations on-Reserve. Ottawa, Ont.: Health Canada; 2012.

- Reference 14

-

Health Canada. Health Canada's Monitoring and Performance Framework for Tuberculosis Programs for First Nations on-Reserve. Feb 12 2016.

- Reference 15

-

Pan-Canadian Public Health Network. Guidance for Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Programs in Canada. 2013.

- Reference 16

-

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. Inuit Tuberculosis Elimination Framework. 2018.

- Reference 17

-

Haworth-Brockman M, Balakumar S, Head B, Keynan Y. Towards TB Elimination: Shared Priorities for TB Program Performance Measurement in Canada, a Proposal for Discussion. Winnipeg, Manitoba: National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases; June 2019. 453.

- Reference 18

-

Cass A, Shaw T, Ehman M, Young J, Flood J, Royce S. Improved Outcomes Found After Implementing a Systematic Evaluation and Program Improvement Process for Tuberculosis. Public Health Reports. 1974-). 2013;128(5):367-376. doi:10.1177/003335491312800507.

- Reference 19

-

Cavany SM, Sumner T, Vynnycky E, et al. An evaluation of tuberculosis contact investigations against national standards. Thorax. 2017;72(8):736-745. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209677.

- Reference 20

-

Government of Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada. Reported cases from 1924 to 2019 in Canada - Notifiable diseases on-line. https://diseases.canada.ca/notifiable/charts?c=pl. Published 2000. Updated Accessed January 1, 2000.

- Reference 21

-

Proceedings of the National Consensus Conference on Tuberculosis. December 3-5, 1997. 1998;24(Supplement 2):1-24.

- Reference 22

-

The global plan to stop TB 2006-2015: actions for life: towards a world free of tuberculosis. Geneva: Stop TB Partnership; 2006.

- Reference 23

-

Stewart TR. The Delphi technique and judgmental forecasting. Clim Change. 1987;11(1-2):97-113. doi:10.1007/BF00138797.

- Reference 24

-

Niederberger M, Spranger J. Delphi Technique in Health Sciences: A Map. Front Public Health. 2020;8:457. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00457.

- Reference 25

-

von Schirnding Y. Health in Sustainable Development Planning: The Role of Indicators. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. WHO/HDE/HID/02.11.

- Reference 26

-

Langlois-Klassen D, Wooldrage KM, Manfreda J, et al. Piecing the puzzle together: foreign-born tuberculosis in an immigrant-receiving country. European Respiratory Journal. 2011;38(4):895-902. doi:10.1183/09031936.00196610.

- Reference 27

-

World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Control: surveillance, Planning, Financing. Geneva: WHO Press; 2005.

- Reference 28

-

Asadi L, Heffernan C, Menzies D, Long R. Effectiveness of Canada's tuberculosis surveillance strategy in identifying immigrants at risk of developing and transmitting tuberculosis: a population-based retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(10):e450-e457. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30161-5.

- Reference 29

-

Greenaway C, Pareek M, Chakra C-NA, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening for latent tuberculosis among migrants in the EU/EEA: a systematic review. Eurosurveillance. 2018;23(14):17. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.14.17-00543.

- Reference 30

-

Berrocal-Almanza LC, Harris R, Lalor MK, et al. Effectiveness of pre-entry active tuberculosis and post-entry latent tuberculosis screening in new entrants to the UK: a retrospective, population-based cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2019;19(11):1191-1201. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30260-9.

- Reference 31

-

Kruijshaar ME, Abubakar I, Stagg HR, Pedrazzoli D, Lipman M. Migration and tuberculosis in the UK: targeting screening for latent infection to those at greatest risk of disease. Thorax. 2013;68(12):1172-1174. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203254.

- Reference 32

-

Ehman M, Shaw T, Cass A, et al. Developing and Using Performance Measures Based on Surveillance Data for Program Improvement in Tuberculosis Control. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2013;19(5):E29-E37. doi:10.1097/0b013e3182751d6f.

- Reference 33

-

Stop TB Partnership, World Health Organization. The Global Plan to Stob TB 2011-2015: transforming the Fight towards Elimination of Tuberculosis. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

- Reference 34

-

Horsburgh CR, Feldman S, Ridzon R. Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Tuberculosis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2000;31(3):633-639. doi:10.1086/314007.

- Reference 35

-

Curtis E, Jones R, Tipene-Leach D, et al. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2019;18(1):174. doi:10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3.

- Reference 36

-

Canadian Health Services Research Foundation. Performance Reporting to Help Organizations Promote Quality Improvement. Healthcare Policy | Politiques de Santé. 2008;4(2):70-74.

- Reference 37

-

Health Canada. Health Portfolio Sex and Gender-Based Analysis Policy. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/transparency/corporate-management-reporting/heath-portfolio-sex-gender-based-analysis-policy.html. Published 2017. Accessed July 27, 2021.

- Reference 38

-

World Health Organization. Closing data gaps in gender. https://www.who.int/activities/improving-treatment-for-snakebite-patients. Published 2019. Accessed July 27, 2021.

- Reference 39

-

Global Health Data Exchange | GHDx. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/. Accessed July 27, 2021.

- Reference 40

-

Gigli KH. Data Disaggregation: A Research Tool to Identify Health Inequities. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2021;35(3):332-336. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2020.12.002.

- Reference 41

-

Gomes MGM, Barreto ML, Glaziou P, et al. End TB strategy: the need to reduce risk inequalities. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2016;16(1):132. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1464-8.

- Reference 42

-

Smith A, Herington E, Loshak H. Tuberculosis Stigma and Racism, Colonialism, and Migration: A Rapid Qualitative Review. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2021.

- Reference 43

-

Mathema B, Andrews JR, Cohen T, et al. Drivers of Tuberculosis Transmission. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(suppl_6):S644-S653. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix354.

- Reference 44

-

Kwan CK, Ernst JD. HIV and Tuberculosis: a Deadly Human Syndemic. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2011;24(2):351-376. doi:10.1128/CMR.00042-10.

- Reference 45

-

Gupta KB, Gupta R, Atreja A, Verma M, Vishvkarma S. Tuberculosis and nutrition. Lung India: Official Organ of Indian Chest Society. 2009;26(1):9-16. doi:10.4103/0970-2113.45198.

- Reference 46

-

Sylla L, Bruce RD, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Integration and co-location of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and drug treatment services. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2007;18(4):306-312. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.03.001.

- Reference 47

-

Zumla A, Malon P, Henderson J, Grange J. Impact of HIV infection on tuberculosis. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2000;76(895):259-268. doi:10.1136/pmj.76.895.259.

- Reference 48

-

Marais BJ, Lönnroth K, Lawn SD, et al. Tuberculosis comorbidity with communicable and non-communicable diseases: integrating health services and control efforts. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2013;13(5):436-448. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70015-X.

- Reference 49

-

Cormier M, Schwartzman K, N'Diaye DS, et al. Proximate determinants of tuberculosis in Indigenous peoples worldwide: a systematic review. The Lancet Global Health. 2019;7(1):e68-e80. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30435-2.

- Reference 50

-

Ali M. Treating tuberculosis as a social disease. The Lancet. 2014;383(9936):2195. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61063-1.

- Reference 51

-

Khan K, Rea E, McDermaid C, et al. Active Tuberculosis among Homeless Persons, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 1998-2007. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2011;17(3):357-365. doi:10.3201/eid1703.100833.

- Reference 52

-

Marks SM, Taylor Z, Burrows NR, Qayad MG, Miller B. Hospitalization of homeless persons with tuberculosis in the United Am. J. Public Health. 2000;90(3):435-438. doi:10.2105/ajph.90.3.435.

- Reference 53

-

Parriott A, Malekinejad M, Miller AP, Marks SM, Horvath H, Kahn JG. Care Cascade for targeted tuberculosis testing and linkage to Care in Homeless Populations in the United States: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:485. doi:10.1186/ s12889-018-5393-x.

- Reference 54

-

Baker MA, Harries AD, Jeon CY, et al. The impact of diabetes on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Medicine. 2011;9(1):81. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-9-81.

- Reference 55

-

Stevenson CR, Forouhi NG, Roglic G, et al. Diabetes and tuberculosis: the impact of the diabetes epidemic on tuberculosis incidence. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):234. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-234.

- Reference 56

-

World Health Organization. Compendium of Indicators for Monitoring and Evaluating National Tuberculosis Programs. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

- Reference 57

-

Henderson DA. The challenge of eradication: lessons from past eradication campaigns. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;2(9 Suppl 1): S4-S8.

- Reference 58

-

World Health Organization. International Health Regulations. Geneva: WHO Press; 2005.

- Reference 59

-

Center for Disease Control. TB - National TB Program Objectives and Performance Targets for 2025. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/programs/evaluation/indicators/default.htm. Published 2019. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- Reference 60

-

Bareja C, Waring J, Stapledon R, Toms C, Douglas P. Tuberculosis notifications in Australia. Commun Dis Intell. 2011;38(4):E356-E368. 2014;

- Reference 61

-

Alaska Departement of Health and Social Services. Alaska Tuberculosis Program Manual. 2017.

- Reference 62

-

Minnesota Department of Health. Published 2021. https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/tb/stats/index.html. Accessed Jul 6, 2021.

- Reference 63

-

California Department of Public Health. TB Performance Trends for National and California Objectives. 2016.

- Reference 64

-

Heffernan C, Long R. Would program performance indicators and a nationally coordinated response accelerate the elimination of tuberculosis in Canada? Can J Public Health. 2019;110(1):31- doi:10.17269/s41997-018-0106-x.

- Reference 65

-

Chan IHY, Kaushik N, Dobler CC. Post-migration follow-up of migrants identified to be at increased risk of developing tuberculosis at pre-migration screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2017;17(7):770-779. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30194-9.

- Reference 66

-

Long R, Asadi L, Heffernan C, et al. Is there a fundamental flaw in Canada's post-arrival immigrant surveillance system for tuberculosis? PLOS One. 2019;14(3):e0212706. doi:10.1371/journal.0212706.

- Reference 67

-

Ronald LA, Campbell JR, Rose C, et al. Estimated impact of World Health Organization latent tuberculosis screening guidelines in a region with a low tuberculosis incidence: retrospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(12):2101-2108. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz188.

- Reference 68

-

Long R, Ellis E. Public Health Agency of Canada, Canadian Lung Association, Canadian Thoracic Society. Canadian Tuberculosis Standards. 2007.

- Reference 69

-

Rutstein SE, Ananworanich J, Fidler S, et al. Clinical and public health implications of acute and early HIV detection and treatment: a scoping review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21579. doi:10.7448/IAS.20.1.21579.

- Reference 70

-

Long R, Niruban S, Heffernan C, et al. A 10-year population based study of 'opt-out' HIV testing of tuberculosis patients in Alberta, Canada: national implications. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98993. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098993.

- Reference 71

-

Bogers SJ, Hulstein SH, Schim van der Loeff MF, et al. Current evidence on the adoption of indicator condition guided testing for HIV in western countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35:100877. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100877.

- Reference 72

-

World Health Organization, UNAIDS, The Global Fund, PEPFAR. A Guide to Monitoring and Evaluation for Collaborative TB/HIV Activities-2015 Revisions. Geneva: WHO Press; 2015.

- Reference 73

-

Canadian Medical Association. Guidelines for the identification, investigation and treatment of individuals with concomitant tuberculosis and HIV infection. Bureau of Communicable Disease Epidemiology, Canada Department of National Health and CMAJ. 1993;148(11):1963-1970.

- Reference 74

-

Long R, Houston S, Hershfield E. Canadian Tuberculosis Committee of the Centre for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Population and Public Health Branch, Health Canada. Recommendations for screening and prevention of tuberculosis in patients with HIV and for screening for HIV in patients with tuberculosis and their contacts. CMAJ. 2003;169(8):789-791.

- Reference 75

-

Haworth-Brockman MJ, Keynan Y. Strengthening tuberculosis surveillance in Canada. CMAJ. 2019;191(26):E743-E744. doi:10.1503/cmaj.72225.

- Reference 76

-

Migliori GB, Nardell E, Yedilbayev A, et al. Reducing tuberculosis transmission: a consensus document from the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(6):1900391. doi:10.1183/13993003.00391-2019.

- Reference 77

-

Golub JE, Bur S, Cronin WA, et al. Delayed tuberculosis diagnosis and tuberculosis transmission. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2006;10(1):24-30.

- Reference 78

-

Mitchison DA. Infectivity of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis during chemotherapy. Eur Respir J. 1990;3(4):385-386.

- Reference 79

-

LaFreniere M, Dam D, Strudwick L, McDermott S. Tuberculosis drug resistance in Canada: 2018. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2020;46(1):9-15. doi:10.14745/ccdr.v46i01a02.

- Reference 80

-

Benator D, Bhattacharya M, Bozeman L, et al. Rifapentine and isoniazid once a week versus rifampicin and isoniazid twice a week for treatment of drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV-negative patients: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet (London, England). 2002;360(9332):528-534.

- Reference 81

-

Calderwood CJ, Wilson JP, Fielding KL, et al. Dynamics of sputum conversion during effective tuberculosis treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Med. 2021;18(4):e1003566. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003566.

- Reference 82

-

World Health Organization. WHA44.8 TUBERCULOSIS CONTROL PROGRAMME. 1991.

- Reference 83

-

Hargreaves JR, Boccia D, Evans CA, Adato M, Petticrew M, Porter JDH. The Social Determinants of Tuberculosis: From Evidence to Action. J. Public Health. 2011;101(4):654-662. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.199505.

- Reference 84

-

Veen J. Microepidemics of tuberculosis: the stone-in-the-pond principle. Tuber Lung Dis. 1992;73(2):73-76. doi:10.1016/0962-8479(92)90058-R.

- Reference 85

-

Fox GJ, Dobler CC, Marks GB. Active case finding in contacts of people with tuberculosis. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;(9):CD008477. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008477.pub2.

- Reference 86

-

National Tuberculosis Controllers Association, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for the investigation of contacts of persons with infectious tuberculosis. Recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-15):1-47.

- Reference 87

-

Luzzati R, Migliori GB, Zignol M, et al. Children under 5 years are at risk for tuberculosis after occasional contact with highly contagious patients: outbreak from a smear-positive healthcare worker. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(5):1701414. doi:10.1183/13993003.01414-2017.

- Reference 88

-

Daley CL, Small PM, Schecter GF, et al. An outbreak of tuberculosis with accelerated progression among persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. An analysis using restriction-fragment-length polymorphisms. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326(4):231-235. doi:10.1056/NEJM199201233260404.

- Reference 89

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Chapter 12: Canadian Tuberculosis Standards 7th Edition: 2014 - Contact follow-up and outbreak management in Tuberculosis control. Published 2014. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/infectious-diseases/canadian-tuberculosis-standards-7th-edition/edition-8.html. Accessed February 17, 2014.

- Reference 90

-

Ai J-W, Ruan Q-L, Liu Q-H, Zhang W-H. Updates on the risk factors for latent tuberculosis reactivation and their managements. Emerging Microbes Infect. 2016;5(2):e10. doi:10.1038/emi.2016.10.

- Reference 91

-

Fox GJ, Dobler CC, Marais BJ, Denholm JT. Preventive therapy for latent tuberculosis infection—the promise and the challenges. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2017;56:68-76. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2016.11.006.

- Reference 92

-

Rangaka MX, Cavalcante SC, Marais BJ, et al. Controlling the seedbeds of tuberculosis: diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis infection. Lancet. 2015;386(10010):2344-2353. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00323-2.

- Reference 93

-

Dobler CC, Martin A, Marks GB. Benefit of treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in individual patients. European Respiratory Journal. 2015;46(5):1397-1406. doi:10.1183/13993003.00577-2015.

- Reference 94

-

Kim HW, Kim JS. Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection and Its Clinical Efficacy. Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases. 2018;81(1):6-12. doi:10.4046/trd.2017.0052.

- Reference 95

-

Comstock GW, Edwards PQ. The competing risks of tuberculosis and hepatitis for adult tuberculin reactors. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1975;111(5):573-577. doi:10.1164/arrd.1975.111.5.573.

- Reference 96

-

Menzies D, Adjobimey M, Ruslami R, et al. Four months of rifampin or nine months of isoniazid for latent tuberculosis in adults. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(5):440-453. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1714283.

- Reference 97

-

Macaraig MM, Jalees M, Lam C, Burzynski J. Improved treatment completion with shorter treatment regimens for latent tuberculous infection. Int j Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018;22(11):1344-1349. doi:10.5588/ijtld.18.0035.

- Reference 98

-

Ferebee SH, Mount FW. Tuberculosis Morbidity in a Controlled Trial of the Prophylactic Use of Isoniazid among Household Contacts. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1962;85(4):490-510.

- Reference 99

-

Molhave M, Wejse C. Historical review of studies on the effect of treating latent tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;92S:S31-S36. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.011.