Archived: Rapid risk assessment: Clade 1 mpox virus outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, public health implications for Canada

Download in PDF format

(1.01 MB, 25 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: 2024-05-10

Assessment completed: April 16, 2024 (with data as of March 26, 2024)

On this page

- Reason for assessment

- Risk question

- Risk statement

- Risk assessment summary

- Technical annex

- Footnotes

- References

Reason for assessment

Concern of importation of clade I mpox virus (MPXV, formerly monkeypox virus) into Canada and subsequent spread, given increasing incidence and potential changing epidemiology in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Risk question

What is the likelihood of clade I MPXV importationFootnote a into Canada and impact of onward spread in the next six months (April to September 2024) either via (a) an individual traveller from the DRC, or (b) via an amplification eventFootnote b outside the DRC or Canada, if such an event were to occur?

Risk statement

Within the next six months, the likelihood of clade I MPXV importation into Canada from the DRC is low to moderate, with a moderate level of uncertainty. However, if an amplification event outside the DRC or Canada were to occur, the likelihood of clade I MPXV importation into Canada from such an event would be moderate, with a high level of uncertainty.

Two different scenarios of onward spread are anticipated, depending on the type of importation:

- If importation were to occur via direct importation from the DRC, transmission is expected to be primarily in the travellers' households and among their non-household close contacts. The impact on affected populations is estimated to be moderate, with a high level of uncertainty.

- If importation were to occur via a traveller from an amplification event, transmission would be expected primarily within high-contact sexual networks, potentially reaching levels seen in the 2022-2023 mpox outbreak in Canada, including some transmission through household contacts. The impact on affected populations is estimated to be moderate, with a moderate level of uncertainty.

The impact on an individual's health is estimated to be minor to moderate for individuals without risk factors, with a high degree of uncertainty. Impact on the health of individuals at higher risk of severe outcomes, including children, pregnant individuals, and the immunocompromisedFootnote c is estimated to be major, with a moderate level of uncertainty.

The impact on the health of the general population for both types of spread patterns is estimated to be minor, with a low level of uncertainty.

Risk assessment summary

| Question | Scenario A: Direct importation: estimate [uncertainty] | Scenario B: Importation via amplification eventtable 1 note a: estimate [uncertainty] |

|---|---|---|

| What is the likelihood of at least one traveller infected with clade I MPXV entering Canada? | Low to moderate [Moderate] | Moderate [High] |

| What is the most likely spread scenario? | Transmission primarily within travellers' households and their non-household close contacts. | Transmission primarily within high-contact sexual networks, potentially at levels seen in the 2022-2023 clade IIb outbreak, including some transmission through household contacts. |

| What would be the impact on an individual's health if infected with clade I MPXV (the magnitude of effects, including impact on mental health, disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare)? | Individual without known risk factors: Minor to Moderate [High] Individual at higher risk of severe outcomes (i.e., children, pregnant individuals, and immunocompromised individuals): Major [Moderate] |

|

| What would be the population health impact on the affected and the general populations? | Cases and their household contacts and non-household close contacts: Moderate [High] General population: Minor [Low] |

Cases and their sexual networks and close contacts: Moderate [Moderate] General population: Minor [Low] |

Notes:See technical annex for definitions. Footnotes:

|

||

Scenario A: Direct importation

There is a low to moderate likelihood, with moderate uncertainty, that a clade I MPXV case will be directly imported from the DRC over the next 6 months (April to September 2024). A simulation-based importation model (Technical Annex: Section 1.4.1) estimated between an 8.1 – 13.5% probability that at least one person infected with clade I MPXV will enter Canada between April and September 2024 from the DRC, assuming incidence in the DRC remains at levels reported in January 2024 (Technical Annex: Section on 2.2). Similarly, this model estimated a 0.3 – 0.9% probability of two or more infected individuals entering Canada from the DRC in this time period. While general travel and immigration patterns from the DRC to Canada are known, limitations in evidence of likelihood of travelling while infectious, the future course of the current DRC outbreaks, and exact travel volumes increase uncertainty.

Scenario B: Importation via amplification event

If an amplification event outside the DRC and Canada were to occur, there is a moderate likelihood, with high uncertainty, that at least one clade I MPXV case will be imported to Canada in the next 6 months. This estimate is based on the following considerations: Canadians have high rates of air travel; the next 6 months overlap with summer travel/vacation, large festivals, and global pride events that may include individuals in high-contact sexual networks. Global pride events likely contributed to onward spread in the 2022-2023 clade IIb MPXV global outbreak, suggesting that such events could do the same for clade I MPXV. The likelihood estimate is highly uncertain since it depends on the type and magnitude of the specific amplification event, and then requires a specific sequence of events that are difficult to predict.

Likely spread scenarios

Clade I MPXV in the DRC disproportionately impacts children and, historically, transmission has been primarily zoonotic with limited person-to-person transmission after spillover events. In 2023, the DRC reported record numbers of mpox cases including the first documented cases of sexually transmitted clade I MPXV and geographic spread to non-endemic areas of the country where 20- to 30-year-olds have been primarily affected and sexual networks are believed to have played an important role.

Historically, MPXV importations into non-endemic settings suggest that even in highly susceptible populations, transmission is limited, likely due to exposure requiring close contact via lesions, respiratory droplets or contaminated shared surfaces/fomites; however, the epidemiology of the current DRC outbreaks introduce uncertainty. All known routes of transmission of MPXV (zoonotic, human-to-human close contact, and human-to-human sexual transmission) are reported in the current DRC outbreaks, but their respective contribution to case counts is unclear at this time.

One spread scenario was considered for each importation type. Scenario A involves direct importation from the DRC, resulting in transmission primarily within travellers' households and their non-household close contacts. Scenario B follows an infectious traveller entering Canada from an amplification event outside of the DRC and Canada. In this scenario, transmission is expected primarily within high-contact sexual networks, potentially at levels seen in the 2022-2023 clade IIb outbreak, including some transmission among household contacts.

There is a moderate level of uncertainty with these spread scenarios, given the limited evidence to estimate mpox susceptibility in Canada, as well as transmissibility of the clade I MPXV circulating in the current DRC outbreaks. Clade I MPXV is not known to be circulating outside of the African continent, so there are challenges to predicting exposure and transmission dynamics in the Canadian context.

Individual impact

The impact of a clade I MPXV infection on an individual's health is expected to be minor to moderate based on evidence from the clade IIb outbreak in which most cases experienced mild to moderate symptoms and fully recovered with adequate treatment. In clade I, symptoms and infections have historically been more severe among those who lack immunity to MPXV (acquired via past infections or vaccination) or receive delayed treatment. This estimate is highly uncertain as it is based on emerging clinical data for clade I MPXV, assumptions about access to care, and clinical experiences from the clade IIb outbreak outside of the DRC context.

The impact of clade I MPXV infections on individuals at greater risk of severe disease and mortality (i.e., children, pregnant individuals, and immunocompromised people) is expected to be major. Children in the DRC have been disproportionately impacted by clade I MPXV infections and account for the majority of deaths to date. Adverse fetal outcomes (e.g., spontaneous fetal abortion) have been documented in infected pregnant individuals. Additionally, those with unsuppressed HIV infection are at risk for more severe disease and death from mpox. This impact estimate has moderate uncertainty, driven by limited evidence on clade I clinical symptoms among these groups, assumptions about access to care, and emerging but limited evidence for a case fatality rate reaching 12% in the current DRC outbreaks.

Impact on affected populations

The population health impact on the affected population is estimated to be moderate for both scenarios A (cases and their household contacts and non-household close contacts) and B (cases and their sexual networks and household contacts). Populations involved may experience morbidity associated with infection and mental health issues such as depression and anxiety. Households and their close contacts may experience stigmatization and social isolation, especially vulnerable populations with limited healthcare access. Stigmatization of mpox cases and their caregivers could increase existing barriers to accessing healthcare. The impact on affected populations in scenario A is highly uncertain due to limited evidence on clade I disease symptoms, severity, as well as transmissibility. Furthermore, available evidence from DRC may not be directly translated to the Canadian context, especially considering differences in access to health services and therapeutics.

The level of MPXV immunity (from vaccination and/or infection) in high-contact sexual networks such as among some members of the gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) population and sex worker population is not high enough (as of December 10, 2023, less than 15% of GBMSM community members had at least partial vaccination) to prevent or significantly diminish expected cases if clade I MPXV were to enter these sexual networks in Canada. In addition, the GBMSM population in Canada has a higher prevalence of HIV compared to the general population, and HIV co-infection puts individuals at greater risk of severe mpox disease and complications. The risk of severe mpox is especially high among those with unsuppressed HIV infection and low CD4 counts. Clade I MPXV spread among GBMSM in Canada may also increase existing experiences of stigma, discrimination, and marginalization, impacting the mental health, wellbeing, and physical safety of GBMSM and those in the broader 2SLGBTQ+ community. This can include post-infection stigma related to mpox lesions. The impact on affected populations in Scenario B has a moderate level of uncertainty driven by limited evidence on disease severity and transmissibility of clade I MPXV in non-endemic, high income countries. The uncertainty is decreased by experience with clade IIb MPXV in Canada.

Impact on general population

The impact on the health of the general population is estimated to be minor for both scenarios A and B, with a low level of uncertainty. This is based on substantial evidence from the 2022-2023 clade IIb MPXV global outbreak, where there was minimal impact to the general population. In addition, the DRC has not reported, either historically or recently, widespread impacts of clade I among the general population.

Future risk in Canada

The probability of importation of a clade I mpox case could increase if the current outbreak were to spread beyond the DRC. Of the countries sharing a border with DRC, the ones with the greatest travel into Canada from April to September last year (2023) were Uganda, Tanzania, and Rwanda (Technical Annex: Section 1.4.1). On March 13, 2024, the Republic of Congo (RC) reported 43 new cases of mpox in several regions, although it is unclear which clade is causing the cases.Footnote 1 No epidemiological link between the DRC and RC cases has been reported to date, but the countries share a border of over 1,500 kilometers. Countries facing challenges, e.g., unrest and food insecurity in Sudan and South Sudan, or those sharing a porous border with DRC, e.g., Burundi and Rwanda, may be particularly vulnerable to importation and undetected spread of clade I MPXV.Footnote 2

There are uncertainties and knowledge gaps (Table 2) associated with the dynamic nature of the clade I MPXV outbreaks in the DRC. Hence, it is challenging to estimate the risk of clade I MPXV to the population of Canada in the next six months and beyond. The worst-case scenario in Canada would be transmission to the general population from high-contact sexual networks or households and non-household close contacts. Potential drivers for spillover and spread include evidence of higher transmissibility of clade I MPXV compared to clade II MPXV, and low mpox immunity in the general population. Onward spread in the general population could be driven by missed cases due to a low index of clinical suspicion and high mpox susceptibility in the general population. Imvamune® vaccinations are approved for use, however, they are not recommended for the general public in Canada at this time. Additionally, vaccine hesitancy could impact clade I mpox control in Canada. Transmission in the general population could result in substantial health and socioeconomic burden.

However, experience with the clade IIb MPXV outbreak suggests that transmission of clade I MPXV would likely be focused within specific high-risk groups if importation were to occur via an infectious traveller from an amplification event (Scenario B). Knowledge gained in the GBMSM community about mpox during the clade IIb outbreak and evidence of behaviour change suggests potential for successful outbreak control if clade I MPXV were to enter high-contact sexual networks in the GBMSM population. Rapid deployment of vaccination campaigns, as well as outreach and tailored communication in partnership with community-based organizations could prevent broader transmission into the general population. Interventions such as case and contact management, education and community outreach, implementation of biomedical prevention (condoms, pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis) and behavioural change, blood screening, and treatment have been effective in controlling other infectious diseases such as syphilis and HIV.

COVID-19 has resulted in pandemic fatigue and burnout for both health care and public health systems. Considering the trajectory of the 2022-23 clade IIb MPXV outbreak and cases in Canada, we do not anticipate seeing clade I MPXV cases reach pandemic levels. However, even in the absence of widespread community transmission, small outbreaks could add strain on the medical and public health resources for diagnostics, treatment, outbreak management, and staff shortages through absenteeism if healthcare staff are affected. In addition, importation and spread of clade I MPXV could have implications for health equity. Potential stigma and isolation requirements could exacerbate health inequities in vulnerable populations.

From a natural environment and wildlife perspective, human-to-animal or animal-to-human transmission of MPXV in Canada could become a concern in the event of ongoing human-to-human transmission in the general population. The likelihood that MPXV becomes enzootic among animal species in Canada with a subsequent ongoing risk of zoonotic spread to humans is unknown.

Proposed actions for public health authorities

Given the risk of importation of clade I MPXV into Canada, early detection, diagnosis, isolation, and contact tracing would be key for the effective control of domestic clade I MPXV transmission. The availability of vaccines and antivirals is also important to Canada's ability to control a likely spread scenario.

Recommendations provided below are based on findings of this risk assessment. These are for consideration by jurisdictions according to their local epidemiology, policies, resources, and priorities. Due to the current level of uncertainty associated with this event, it is important that the public health response be proportionate to the risk.

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) will continue to engage and collaborate with federal, provincial, territorial and other non-governmental organizations to assess public health risks associated with importation of clade I MPXV to Canada.

Public health interventions: prevention and response

Employ similar public health control measures as those taken during the 2022-2023 clade IIb MPXV global outbreak to identify cases and close contacts and limit spread. Refer to Mpox (monkeypox): Public health management of cases and contacts in Canada.

Continue to follow vaccination and post exposure prophylaxis guidance recommended by the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI rapid response: Interim guidance on the use of Imvamune in the context of monkeypox outbreaks in Canada).

Avail PHAC's National Emergency Strategic Stockpile (NESS) for both vaccine (Imvamune®) and therapeutics (TPOXX®), when needed.

Risk communication

Consider targeted educational and awareness messaging for populations at increased mpox risk while continuing with broad communication to Canadians. When necessary, correct and counter mis- or disinformation.

Consider further awareness and education of health professionals on early detection and management of clade I MPXV infections. Additionally, continue to raise awareness among their patients, especially those intending to travel to endemic countries, about the importance of mpox vaccination.

Consider increasing awareness among travellers to consult a health care provider or visit a travel health clinic preferably at least 6 weeks before travel to get personalized health advice and recommendations.

Collaboration and coordination

Engage and communicate with federal/provincial/territorial (FPT) government, Indigenous, and local public health partners, as well as relevant community partners from populations at increased risk, to enable public health control measures.

Increase research readiness by exploring research opportunities to address the key scientific uncertainties and knowledge gaps identified during this assessment.

Facilitate easy access to healthcare, especially for populations at increased mpox risk.

Surveillance and reporting

Prepare to collect, collate, analyse, and share clade I MPXV data and summarize emerging evidence to inform the local, provincial/territorial and federal public health response. Also monitor for potential changing transmission dynamics (e.g., from predominately sexual to household/community transmission).

Continue to monitor and assess vaccination coverage among affected populations to identify areas with higher susceptibility to outbreaks.

Technical annex

Event background

On June 6, 2023, the DRC declared a public health emergency for its current clade I MPXV outbreak. A total of 14,626 suspected mpox cases, including 654 suspected deaths, were reported in the DRC in 2023.Footnote 3 This is the highest number of cases and deaths ever documented for mpox in the DRC (~3 times more cases than 2022 and ~5 times more than 2021).Footnote 2 The case fatality rate (CFR) among suspected cases identified between epidemiological weeks 1 though 10 of 2024 (6.9%) is currently higher than that for all of 2023 (4.5%), but has been trending downwards in recent weeks (2024 CFR previously reported at 8.4% between epidemiological weeks 1 through 6).Footnote 3Footnote 4 The majority of suspected mpox cases (70.4%) and deaths (86.7%) are among children less than 15 years of age in the DRC.Footnote 3 Both historically and recently, children are disproportionately impacted by mpox in the DRC. Notably, the DRC is reporting geographic spread of mpox to non-endemic, often urban areas with some provinces reporting cases for the first time, primarily affecting 20- to 30-year-olds. Recent evidence suggests that heterosexual partners and involvement in the sex industry is playing a role in the urban spread.Footnote 5Footnote 6 Before April 2023, there were no formally documented cases of sexual transmission of clade I MPXV globally, and transmission in endemic areas was primarily zoonotic with limited person-to-person transmission after spillover events.Footnote 6 Analyses of viral sequences from cases in DRC revealed that more than one outbreak of clade I MPXV is occurring, and one of the mutations identified impairs polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection of clade I MPXV when using the CDC-recommended protocol.Footnote 7

There are notable and ongoing limitations with respect to case detection, investigation, and reporting in the DRC. Given reduced capacity for rapid diagnostic testing, DRC reports "suspected" mpox cases, which are based on clinical examination of typical signs and symptoms. About 15% of suspected cases in 2024 have undergone confirmatory testing in the DRC and about 75% of case samples tested positive for MPXV.Footnote 5 As a result, there is uncertainty around emerging transmission dynamics of the current clade I MPXV outbreaks. Reports of sexual and increased close contact transmission raise additional concerns over the rapid expansion of the outbreak in the country and surrounding areas.Footnote 6 There is concern that the mpox outbreak in the DRC has not yet peaked amidst a broader context of a persisting humanitarian crisis, concurrent epidemics (especially among children), and other health and social inequities.

Only two clades of MPXV have been detected to date: clade I (previously known as Congo Basin or central African clade) and clade II (the former west African clade). Clade II is further divided into two subclades: IIa and IIb. The 2022-2023 global mpox outbreak was linked to a new sub-clade of MPXV, clade IIb. Clade I is the only known circulating strain in the DRC, where it is endemic. Evidence suggests that clade I is more transmissible and may cause more severe disease than clade II. Prior to the current outbreak, a meta-analysis of clade I MPXV in the DRC estimated the secondary attack rate (SAR) among unvaccinated household members to be 7.6% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.0-15.2%).Footnote 7 Another study reported a SAR of 50% and nine families showed >1 transmission event, and >6 transmission events occurred within one health zone.Footnote 8 As a crude comparison, in a clade IIb MPXV outbreak in the US, the SAR among pediatric household contacts of a mpox case was 4.7%.Footnote 9 The basic reproduction number (R0) of clade I MPXV is estimated to be 0.8 based on surveillance data from DRC.Footnote 7Footnote 10 Clade I is associated with more severe disease outcomes compared to clade II, including a more pronounced rash, and greater human-to-human transmission.Footnote 6Footnote 11Footnote 12 Clade I is associated with a mortality of up to 10%, whereas clade IIb has a mortality of less than 1%.

To date, only clade IIb has been detected in Canada. Five mpox cases have been reported among people under 18 years of age.Footnote 13 As of September 29, 2023, 1,515 mpox cases have been reported to PHAC (1,443 confirmed; 72 probable). There continue to be cases in Canada (all clade IIb) including a notable increase in cases reported in Ontario for whom travel has not been reported, suggesting ongoing local transmission.Footnote 14

Mpox susceptibility in Canada

Routine smallpox immunization in Canada ceased in 1971 and globally in the 1980s. People born in Canada in 1972 or later have not been routinely immunized against smallpox; therefore, the majority of the population is fully susceptible to mpox.Footnote 15 Statistics Canada estimates 62% of the Canadian population in 2023 are 0- to 49-years old (likely unvaccinated against smallpox);Footnote 16 and with a vaccine effectiveness of ~80% for smallpox vaccine against mpox, based on the above data,Footnote 17Footnote 18Footnote 19 approximately 70% of the Canadian population is susceptible to mpox. The duration of immunity from smallpox vaccination received several decades ago is unclear, and therefore the level of protective immunity against mpox in older Canadians, is currently unknown.

The GBMSM community in Canada began receiving Imvamune® vaccinations against mpox in 2022. By December 10, 2023, less than 15% of GBMSM community members had at least partial vaccination (based on about 100,300 people who got at least a first dose and an estimated 669,000 members in the GBMSM community in 2020), and an estimated 6% had been fully vaccinated (based on 39,000 people with a second dose) or immunized (i.e., fully vaccinated, previously infected with mpox, previously infected with mpox + 1 dose, previously infected with mpox + 2 doses, previously infected with mpox + historical smallpox vaccination, etc.) (IDVPB-VCES personal communication, Mar 2024).Footnote 20

Definitions

Amplification event: Any event in which someone with mpox comes into contact and subsequently exposes and infects more people than average (i.e., mass exposure). Such events can include but are not limited to: cruise ships, parties, sex on premises venues.

Direct Importation: The occurrence of an infectious person arriving in Canada via an itinerary or journey that begins in the DRC and whose final destination is Canada, irrespective of stopovers elsewhere between the departure and arrival locations.

High-contact sexual network: Refers to clustered sexual networks with a high number of sexual partners per individual (6-month average: ≥25 sexual partners). Based on a recent Canadian study,Footnote 21 the following sexual practices were associated with a higher number of sexual partners: attending group sex events, using dating applications, attending bathhouses and/or sex clubs, and engaging in transactional sex in the past 6 months.

Immunocompromised: Individuals with impaired immune response functions due to a variety of factors, including immunodeficiency disorders, treatment with immunosuppressives, cancer, unsuppressed HIV, and others.

Mpox exposure: Refers to direct contact with an infected person's skin lesions, blood, body fluids or mucosal surfaces (such as eyes, mouth, throat, genitalia, perianal area), or sharing clothing, bedding or common items that have been contaminated with the infected person's fluids or sores. Examples of behaviours with potential for exposure can include sexual contact, contact from providing care, or living in the same household as a case.

Key assumptions

- This risk assessment is based on the evidence available at the time of writing.

- On April 13, 2024, Congolese health authorities announced emergency approval of two mpox vaccines and an antiviral.Footnote 22 The potential impact of these forthcoming interventions is unknown at this time and was not considered in the risk estimates.

- The Ministers of Health of Angola, Benin, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, Uganda and partners, met in Kinshasa, DRC and released a joint statement on April 13, 2024.Footnote 23 The potential impact of this public health response is unknown at this time and was not considered in the risk estimates.

- The assessment assumes that those traveling from the DRC will most often travel to cities with a larger than average Congolese population, rather than disperse randomly across Canada.

- Infectious individuals entering Canada could contribute to both likely spread scenarios, but only one pathway is explored in the risk assessment for simplicity.

- It is assumed that people living in Canada who received a smallpox routine immunization are susceptible to mpox based on insufficient evidence for residual, cross-protective immunity.

- Little is known about the epidemiological or viral characteristics of clade I MPXV outside of the African continent. This assessment assumes some similarities with previous strains of clade I and clade IIb MPXV, and no drastic increases in transmissibility or severity, though these possibilities are captured in the uncertainty estimates.

- A standard level of treatment would be provided to any cases in Canada, except the first cases when the index of suspicion might be low particularly if the case has no history of travel to an endemic area or involvement in high-contact sexual networks.

- Case and contact management guidance will be expected to be implemented as usual (i.e., as it was with the 2022-2023 clade IIb MPXV outbreak).

- Given that the likelihood of an amplification event occurring is highly uncertain and could not be estimated within the scope of this risk assessment, such an event was provided as a condition of Question 1b.

- For the purposes of this risk assessment, it is assumed that a high degree of direct, person-to-person contact (e.g., sexual contact) will occur at an international amplification event.

Methods

This assessment was conducted by PHAC between March 4 and April 16, 2024 (see Appendix B for a list of contributors). Data collection ended on March 26, 2024.

The rapid risk assessment (RRA) methodology used by PHAC has been adapted from the Joint Risk Assessment Operational Tool (JRA OT) to assess the risk posed by zoonotic disease hazards developed jointly by the World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH).Footnote 24 PHAC adapted the JRA OT by modifying the likelihood and impact scales and associated definitions to incorporate elements from other RRA frameworks that are relevant to the Canadian context.Footnote 25Footnote 26

PHAC convened a multi-sectoral team that formed two committees: the RRA Oversight Committee and the RRA Technical Team. The Oversight Committee (largely comprised of senior managers and decision makers) defined the hazard, agreed on the purpose and key objectives for the assessment, outlined the scope, drafted the risk question, and reviewed the recommendations. The Technical Team (largely comprised of those with expertise and/or information related to the assessment) characterized the risk by providing qualitative estimates of likelihood, impact and uncertainty in relation to the risk questions being assessed, based on the available evidence and expert opinion. The federal experts represented a variety of disciplines such as epidemiologists, virologists, physicians, travel health and migration experts, and health promotion experts (Appendix B).

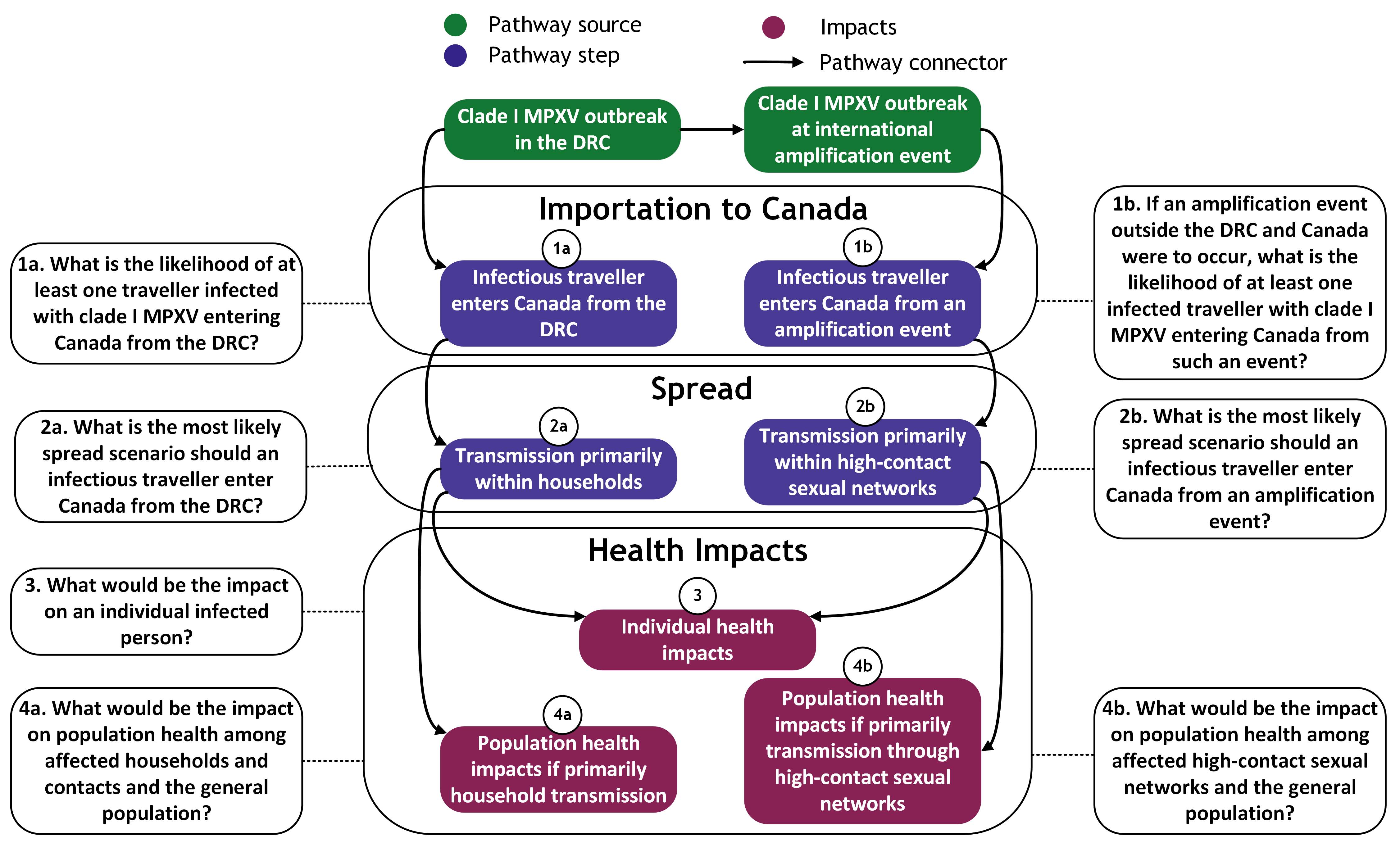

The risk question being assessed was visualized using a risk pathway (Figure 1), a diagrammatic representation of the key components of the sequence of the hazard from its source to its potential infection of the host of interest and subsequent spread scenarios. Each step in the risk pathway is associated with a likelihood or impact sub-question that was then addressed as part of the risk assessment. The Technical Team were introduced to the risk pathway and associated questions in a meeting.

Evidence was gathered by scientific experts using a rapid, non-systematic literature search and includes published articles and pre-print manuscripts, reports on the current outbreak including surveillance reports, and communication from multi-sectoral experts. Where appropriate, some references have been included; where references are not included, this evidence was informed by input from the subject matter experts. Public Health Risk Sciences (within the National Microbiology Laboratory Branch) provided additional evidence through mathematical modelling. The details of this model are provided below.

Final estimates of likelihood or impact for each sub-question were based on discussion with the Technical Team and review of the draft report by Technical Team and Oversight Committee. In addition, Technical Team members were asked to consult on key uncertainties and knowledge gaps that influenced their level of uncertainty in likelihood and impact estimates. These were consolidated into a list of key uncertainties and knowledge gaps related to this risk assessment (Table 2).

Definitions of likelihood (Table A.2), impact (Table A.3 and Table A.4), and uncertainty (Table A.1) are provided in Appendix A. Since the risk pathway describes the sequence of events leading up to the undesired outcome, the likelihood of each event is conditional on the likelihood of preceding steps in the risk pathway, as assessed in the estimation process for each risk pathway sub-question. The likelihood for the overall risk question is therefore determined by the lowest likelihood estimated along the risk pathway.

The findings and conclusions represent the consensual, but not necessarily unanimous, opinions of experts contributing to this risk assessment, and should not be interpreted as representing the views of all participants and their respective organizations.

Disease importation model

The first component of this analysis estimates the number of Canadian passport holders entering Canada via air travel as well as those entering with a foreign passport (hereafter, foreign nationals), for an estimate of total incoming travellers within a specific time period and from a specific source country. Using an estimate of source country (DRC) incidence, length of infection and the proportion susceptible to mpox in the source country and destination (Canada) country, the model computes probability estimates of at least one infected case or at least two infected cases entering Canada in the period of assessment. The model was run for 100,000 simulations to estimate importation risk of clade I mpox from the DRC from April to September 2024, inclusive. Results are presented as the percentage of these simulations in which at least one person with clade I MPXV entered Canada. Several assumptions and caveats were necessary in executing the model; these are listed below.

Considerations in model interpretation:

- The data provided by the Canadian Border Security Agency required that travel from the DRC and from the RC be pooled to total travellers from both nations.

- Travel volumes between one and ten travellers are suppressed for privacy; scenarios were run with the suppressed values imputed as the minimum (1) and maximum (10) volume, creating a possible range of total travellers and importation probability.

- Travel volumes for April through September 2024 were assumed to be the same as those reported in April through September 2023.

- The model assumes that the country population is representative of the traveller population in terms of proportion susceptible and rates of infection.

- This model assumes that total cases occurring in the DRC during the risk assessment period (April-September 2024) will occur at the same levels seen in January 2024.

- Smallpox immunizations from routine campaigns concluded in the 20th century were assumed to provide no immunity to an mpox infection.

- Due to limited available evidence, when necessary, data from the clade IIb MPXV research were used in this model.

- Lifetime prevalence of past mpox infections in the DRC was estimated using reported seroprevalence among those without smallpox vaccination scars in the country.Footnote 27

Detailed risk assessment results

Figure 1 - Text description

Description of pathway sources, the steps along the pathway, and the impacts on individual and population health. Events are in the order assessed by the rapid risk assessment. Each event is conditional on the preceding event indicated by a pathway connector.

Pathway sources and importation to Canada

- Risk sub-question 1a: What is the likelihood of at least one traveller infected with clade I MPXV entering Canada from the DRC?

- Pathway connector from clade I MPXV outbreak in the DRC leading to infectious travelled enters Canada from the DRC

- Risk sub-question 1b: If an amplification event outside the DRC and Canada were to occur, what is the likelihood of at least one infected traveller with clade I MPXV entering Canada from such an event?

- Pathway connector from clade I MPXV outbreak at international amplification event leading to infectious traveller enters Canada from an amplification event

Spread

- Risk sub-question 2a: What is the most likely spread scenario should an infectious traveller enter Canada from the DRC?

- Pathway connector from infectious traveller enters Canada from the DRC leading to transmission primarily within households

- Risk sub-question 2b: What is the most likely spread scenario should an infectious traveller enter Canada from an amplification event?

- Pathway connector from infectious traveller enters Canada from an amplification event leading to transmission primarily within high-contact sexual networks

Health impacts

- Risk sub-question 3: What would be the impact on an individual infected person?

- Pathway connector from transmission primarily within households leading to individual health impacts

- Pathway connector from transmission primarily within high-contact sexual networks leading to individual health impacts

- Risk sub-question 4a: What would be the impact on population health among affected households and contacts and the general population?

- Pathway connector from transmission primarily within households leading to population health impacts if primarily household transmission

- Risk sub-question 4b: What would be the impact on population health among affected high-contact sexual networks and the general population?

- Pathway connector from transmission primarily within high-contact sexual networks leading to population health impacts if primarily transmission through high-contact sexual networks

Likelihood and impact estimates

The likelihood scale used in this assessment is described in Table A.2. The magnitude of effects and impact scales used in this assessment are described in Table A.3 and Table A.4.

What is the likelihood of at least one traveller infected with clade I MPXV entering Canada from the DRC in the next six months?

The likelihood of at least one traveller infected with clade I MPXV entering Canada from the DRC in the next six months is estimated to be low to moderate, with moderate uncertainty.

- Assuming the incidence of cases in the DRC continues to be reported at levels observed in January 2024, there is an estimated 8.1 – 13.5% probability of at least one infectious person entering Canada between April and September 2024 from the DRC, and a 0.3 – 0.9% chance of at least two infectious individuals entering (see Section 1.4.1 for model details).

- Cumulatively, between epidemiological weeks 1 through 10 of 2024, 3,941 suspected cases of clade I MPXV have been identified in the DRC; 458 of these cases were laboratory confirmed.Footnote 3

- A 36.8% decrease in weekly suspected cases was reported in epidemiological week 10 compared to week 8.Footnote 3Footnote 28

- Between April to September 2023, an estimated 7,596 - 13,383 individuals traveled by plane from the DRC and RC to Canada (Section 1.4.1).

- The most popular arrival airports for these passengers were: Montréal-Trudeau (66%), Toronto Pearson (15%), and Ottawa Macdonald-Cartier (6%).

- In 2023, individuals from the DRC settled in Canada as asylum claimants (<2,025), permanent residents (<750), and temporary residents (<3,500) (IRCC, personal communication, March 2024).

- In 2024, <100 refugees are expected to arrive in Canada directly from the DRC (IRCC, personal communication, March 2024).

- While general travel and immigration patterns from the DRC to Canada are known, limitations in evidence of likelihood of travelling while infectious, the future course of the current outbreak, and exact travel volumes increase uncertainty.

- Mpox is not currently listed in the schedule of the Quarantine Act (QA), which will limit the powers of Quarantine Officers (QO) when dealing with a case of mpox.

If an amplification event outside the DRC and Canada were to occur, what is the likelihood of at least one traveller infected with clade I MPXV entering Canada from such an event in the next six months?

The likelihood of at least one traveller infected with clade I MPXV entering Canada from an amplification event outside the DRC and Canada in the next six months is estimated to be moderate, with high uncertainty.

- The 2022-2023 clade IIb mpox global outbreak:

- In the 2022-2023 clade IIb MPXV global outbreak, gatherings at festivals and parties were notable transmission events.Footnote 29Footnote 30

- Particularly those attended by GBMSM and the broader 2SLBGTQI+ community.

- Pride Season occurs between June and September and is expected to be celebrated in Summer 2024 through large-scale gatherings of the 2SLGBTQI+ community.Footnote 31

- In the 2022-2023 clade IIb MPXV global outbreak, gatherings at festivals and parties were notable transmission events.Footnote 29Footnote 30

- Travel data for Canada:

- April through September is the busiest international travel period for overnight visits originating from Canada and in 2019 Canada ranked within the top third of nations in respect to overnight international trips per 1,000 people.Footnote 32Footnote 33

- Some of the DRC's top international destinations are also popular destinations for flights originating from Canada (e.g., Belgium, France, China); it is possible an individual travelling to Canada would be infected at a prior international amplification event, were one to happen (based on unpublished International Air Transport Association data, 2023).

- The scenario relies on a sequence of largely unpredictable events to occur: an individual being infected with mpox at an amplification event and then traveling to Canada when infectious.

- Mpox is not currently listed in the schedule of the QA, which will limit the powers of QOs when dealing with a case of mpox.

What is the most likely spread scenario should an infectious traveller enter Canada from the DRC?

The most likely spread scenario should an infectious traveller enter Canada from the DRC is transmission within households and among non-household close contacts. There is a moderate level of uncertainty associated with this spread scenario.

- Canadian residents living in communities with a high proportion of Congolese people (the term Congolese here includes individuals from RC and DRC and their descendants) (e.g., some communities in Quebec, census) may be at higher probability of exposure due to the likelihood that a traveller may be returning to or visiting their community. Between 2019 and 2023, most people from the DRC with a valid Permanent Resident status or Temporary Resident visa settled in QC, ON, and AB. The number of TR arrivals increased annually during this time period (with the exception of 2020) (IRCC, personal communication, March 2024).

- Mpox immunity in the Canadian-Congolese population is unknown, but some level of immunity likely exists from routine smallpox vaccination in the older age group, and/or previous mpox infection outside of Canada in first generation Canadian-Congolese.

- Overall population susceptibility to mpox in Canada is very high. A small fraction of the Canadian population is immunized against mpox (IDVPB-VCES personal communication, March 2024); however, Health Canada has authorized the Imvamune® vaccine for mpox virus and orthopoxvirus infections in adults >= 18 years who are at high risk of exposure.

- Evidence to estimate mpox susceptibility in Canada is limited. Transmissibility of the clade I MPXV circulating in the current DRC outbreaks is uncertain.

What is the most likely spread scenario if an infectious traveller enters Canada from an amplification event?

The most likely spread scenario if an infectious traveller enters Canada from an amplification event is transmission within high-contact sexual networks, potentially at levels seen in the 2022-2023 clade IIb outbreak, including some transmission through household contacts. There is a moderate level of uncertainty associated with this spread scenario.

- Since April 2023, many cases of clade I mpox in DRC have been associated with sexual contact, which had not previously been reported as a mode of transmission for this clade.Footnote 34Footnote 35

- Examples of high-contact sexual networks include some GBMSM sexual networks and sex worker sexual networks. Analyses of infection transmission dynamics show that sexual networks among GBMSM exhibit high heterogeneity.Footnote 36 If an individual in a high-contact GBMSM sexual network were infectious with clade I MPXV, this could result in spread within the GBMSM population.Footnote 30 If clade I MPXV were to exhibit similar transmissibility as was observed for clade IIb during the 2022-2023 global outbreak, spread through GBMSM high-contact sexual networks is expected to be more likely than through other population networks.

- Due to ongoing circulation of clade IIb MPXV in Canada, if clade I mpox presents similarly to clade IIb, there should be a strong clinical suspicion for mpox in individuals presenting with symptoms and with risk factors for clade IIb. It is possible, however, that the first cases of clade I mpox in Canada may not be identified as clade I, resulting in onward spread.

- The 2022-2023 clade IIb MPXV outbreak and sexual network dynamics:

- Analysis of the mpox clade IIb epidemic in North America reported that new viral importations played a limited role in the ongoing spread of mpox, suggesting that the sustained epidemic was the result of local transmission among GBMSM.Footnote 30

- In Canada for clade IIb MPXV in 2022, the probability of transmission per contact among GBMSM was assumed to be 9.1%-11.4%, and 0.46%-0.57% among the general population (low risk group), respectively.Footnote 37

- Modelling of the transmission dynamics of clade II MPXV using data from the United Kingdom (UK), Spain, Portugal, Germany and Italy showed the mpox effective reproduction number among GBMSM to be approximately 2.5 which is significantly above the 1.0 thresholdFootnote 38 which may be explained by increased transmissibility due to clustering (in time) of multiple high-contact events among GBMSM with dense sexual networks.

- In the UK for clade IIb MPXV in 2022, the R0 for other (non-sexual) transmission pathways was estimated to be 0.04 (95% CI: 0.009–0.07), while the R0 for the GBMSM population was estimated at 5.16 (95% CI: 2.96–9.24).Footnote 39

- Susceptibility of GBMSM in Canada:

- A proportion of the GBMSM population in Canada has some immunity to clade I MPXV through clade IIb infection and/or Imvamune® vaccination, but it is estimated that only 6% are fully vaccinated or immunized.

- It was estimated that behaviour change rather than vaccination was likely the main cause of the short epidemic duration for clade IIb MPXV.Footnote 30Footnote 39Footnote 40 Knowledge gained in the GBMSM community about mpox during the clade IIb outbreak and evidence of behaviour change in some jurisdictions suggests potential for successful outbreak control if clade I MPXV were to enter the GBMSM population and rapid/early interventions were implemented (e.g., outreach and tailored communication in partnership with community-based organizations that work with GBMSM; rapid deployment of vaccination campaigns).

What would be the impact on an individual's health if infected with clade I MPXV (the magnitude of effects, including impact on mental health, disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare)?

The impact on an individual's health is estimated to be minor to moderate for individuals without risk factors, with high uncertainty. Impact on the health of individuals with risk factors for severe outcomes, including children, pregnant individuals, and the immunocompromised is estimated to be major, with moderate uncertainty.

- Potential social, financial and logistical challenges associated with isolation could be burdensome for infected individuals and their families, caregivers, and household members. Additionally, infected individuals and their networks may be the targets of stigma, discrimination, and racism.Footnote 41Footnote 42

- Mpox outbreaks and their containment can cause mental health issues such as anger, frustration, depression and anxiety.Footnote 43Footnote 44

- Impacts for an individual infected without risk factors for severe disease:

- Clade I mpox cases generally experience mild to moderate symptoms that commonly include fever, cough, lymphadenopathy, sore throat, muscle pain, vomiting, nausea, conjunctivitis, and rash or lesions (oral and anogenital).Footnote 6Footnote 35 Based on the clade IIb global outbreak, pain management is commonly required for these symptoms.Footnote 45 Symptoms are worse among individuals lacking immunity (i.e., unvaccinated or no prior infection) or with delayed treatment.Footnote 12Footnote 46 Notably, clade I MPXV is associated with a higher CFR and more severe disease than clade II MPXV, including disseminated lesions, prodromal symptoms, and hospitalization.Footnote 47Footnote 48Footnote 49

- With adequate treatment, most patients fully recover without significant impairments to their quality of life.Footnote 50

- Reported CFRs for clade I MPXV have ranged from 0 to 10%.Footnote 51Footnote 52 The CFR reported in the current DRC outbreak is currently higher for 2024 than during this period in 2023. In 2024, between epidemiological weeks 1 through 10, the DRC reported 3,941 suspected cases with a CFR of 6.9%.Footnote 3 By comparison, during epidemiological weeks 1 through 10 in 2023, 1,388 suspected cases were reported with a CFR of 4.5%.

- There is limited clade I MPXV clinical and hospitalization data. The estimate assumes that experiences from the clade IIb outbreak can be applied to clade I impacts outside the DRC context and that individuals will have access to adequate care.

- Impacts for individuals with risk factors for severe disease outcomes:

- Children are more likely to experience severe symptoms and 86.7% of the suspected mpox deaths in the DRC in 2024 have been among those aged 0 to 15 years.Footnote 3

- Infections during pregnancy have been reported to result in adverse consequences for the fetus, including spontaneous abortion.Footnote 53 A single study (n=4 cases) found a 75% perinatal fatality rate among maternal clade I MPXV infections, including the only documented case of placental infection and stillbirth from congenital mpox syndrome.Footnote 54

- Immunocompromised individuals are considered at greater risk of more severe disease and death from mpox.Footnote 55Footnote 56 HIV-related immunosuppression, for example, has been associated with more frequent fever, anogenital lesions and proctitis in mpox patients.Footnote 57 Furthermore, mpox severity was related to poor HIV continuum of care outcomes and low CD4+ cell counts.

- There is limited evidence on clade I clinical symptoms among children and pregnant individuals, however there is substantial evidence on clade IIb among immunocompromised individuals. Uncertainty in the impact estimate is also driven by assumptions about access to care, and emerging but limited evidence for a CFR reaching 12% in the current DRC outbreaks, with most fatalities occurring in children.

What would be the impact on population health if there is transmission within households and among non-household close contacts?

If the spread scenario is transmission within households and among non-household close contacts, the impact on affected populations is estimated to be moderate, with high uncertainty, and the impact on the health of the general population is estimated to be minor, with low uncertainty.

- Impact on affected household members and their non-household close contacts is estimated to be moderate

- Households and their close contacts may experience stigmatization and social isolation,Footnote 58Footnote 59 especially vulnerable populations with limited healthcare access. This can include post-infection stigma related to mpox lesions.Footnote 42 Stigmatization of mpox cases and their caregivers could increase existing barriers to healthcare seeking; potentially contributing to increased transmission of the virus in the general population.

- In a US study, the SAR among children who were household contacts of an mpox case was 4.7% (6 of 129 pediatric household contacts).Footnote 9 The SAR was 7.1% for children <9 years old and dropped to 0% for pediatric household contacts >= 10 years old.

- In DRC, the CFR between epidemiological weeks 1 though 10 of 2024 (6.9%) was higher than that for all of 2023 (4.5%), but has been trending downwards in recent weeks.Footnote 3Footnote 4 There is high uncertainty as to whether a similar CFR would apply in Canada due to differences between the DRC and Canadian contexts, including population immunity, concurrent epidemics (especially those affecting children in the DRC, such as measles), and access to testing and treatment. Demand on health services is therefore also uncertain in Canada due to differences between the DRC and Canadian contexts.

- The impact on affected populations is highly uncertain due to limited evidence on disease severity and transmissibility of clade I MPXV in non-endemic, high-income countries.

- Impacts on the health of the general population are estimated to be minor:

- Depending on the transmissibility of the current clade I MPXV in the DRC outbreaks, spillover into the general population is possible, though not very likely if transmissibility is similar to that of clade IIb MPXV. Overall population susceptibility to mpox in Canada is very high. A small fraction of the Canadian population is immunized against mpox (IDVPB-VCES personal communication, March 2024); however, Health Canada has authorized the Imvamune® vaccine for mpox virus and orthopoxvirus infections in adults >= 18 years who are at high risk of exposure.Footnote 60 The duration of immunity from smallpox vaccination received several decades ago is unclear, and therefore the level of population susceptibility in older Canadians, is currently unknown.

- Approximately 14% of Canadians aged 15 years or older are immunocompromised,Footnote 61 and at higher risk of hospitalization, complications and death from mpox infection should clade I MPXV spill over into or begin to circulate in the general population.Footnote 6

- The minor impact on the general population is associated with low uncertainty. This is based on substantial evidence from the 2022-2023 clade IIb MPXV global outbreak, where there was minimal impact to the general population. In addition, the DRC has not reported, either historically or recently, widespread impacts of clade I among the general population. Additionally, potential expected numbers of cases in Canada will likely not be high enough to spillover to the general population in the current spread scenario.

What would be the impact on population health if there is transmission within high-contact sexual networks and their household contacts, potentially at levels seen in the 2022-2023 clade IIb outbreak?

If the spread scenario is transmission primarily within high-contact sexual networks, potentially reaching levels seen in the 2022-2023 mpox outbreak in Canada, including some transmission through household contacts, the impact on affected populations is estimated to be moderate, with a moderate level of uncertainty. The impact on the health of the general population is estimated to be minor, with a low level of uncertainty

- Impacts on those involved in high-contact sexual networks and their household contacts are estimated to be moderate:

- The impacts related to mental health issues and stigma mentioned in Scenario A are applicable to Scenario B. Existing systemic barriers could impede access and uptake of mpox testing, prevention (e.g., vaccines), care and treatment, thereby perpetuating ongoing transmission, and increasing morbidity and mortality. Clade I MPXV spread within the Canadian GBMSM or sex worker populations may increase existing stigma experienced by these populations and negatively impact their healthcare access, thereby exacerbating health inequities.Footnote 62

- Stigma may influence individuals' and communities' long-term engagement in the mpox care cascade.

- Evidence suggests that in Canada, the relatively short duration of the clade IIb mpox outbreak was largely attributable to behaviour change and not vaccination,Footnote 40 which could suggest similar temporary behaviour change if clade I MPXV were to enter GBMSM high-contact sexual networks. A US study showed that a 2-dose mpox vaccination campaign could prevent 21.2% of mpox cases and awareness and behavioural changes in the high-risk population could prevent 15.4% of cases. However, a combination of both measures could prevent 64.0% of mpox cases.Footnote 63

- The number of mpox cases in the 2022-2023 clade IIb outbreak can provide a frame of reference for potential cases from a clade I MPXV outbreak. In the first six months of the 2022-2023 clade IIb outbreak, Canada reported 1470 (1394 confirmed; 76 probable) cases, with a maximum of 30 cases per day being reported three months after initial importation of the virus.Footnote 40

- The GBMSM population in Canada has a higher prevalence of HIV compared to the general population, which puts them at greater risk of severe and/or complicated symptoms of mpox due to an elevated probability of a co-infection with HIV.Footnote 64Footnote 65

- The impact on affected populations is associated with moderate uncertainty due to limited evidence on disease severity and transmissibility of clade I MPXV in non-endemic, high income countries, but considerable experience with clade IIb MPXV in the GBMSM population in Canada.

- Impacts on the health of the general population are assessed to be minor:

- During the 2022-2023 mpox outbreak in Canada, most cases were within the GBMSM population, with very limited spillover into non-GBMSM populations.Footnote 40Footnote 66Footnote 67

- Due to the potential high rate of spread within high-contact sexual networks, there is a risk of possible spillover to the general population. Risk of spillover into the general population could be driven by late or missed diagnoses in close contacts of those in high-contact sexual networks, due to assumptions about their risk e.g., female partners of males involved in high-contact sexual networks.Footnote 68 Onward spread in the general population could be driven by missed cases due to a low index of clinical suspicion and high mpox susceptibility in the general population.

- Health Canada has authorized the Imvamune® vaccine for mpox virus and orthopoxvirus infections in adults >= 18 years who are at high risk of exposure.Footnote 2 Therefore, in the event that there were transmissions within the high-contact sexual networks, vaccination uptake could support outbreak control and limit population morbidity and mortality.

- The minor impact on the general populations is associated with low uncertainty. This is based on substantial evidence from the 2022-2023 global clade IIb outbreak, where there was minimal impact to the general population, and that the DRC has not reported, either historically or recently, widespread impacts of clade I among the general population.

Limitations and knowledge gaps

This assessment is based on facts known to PHAC at the time of publication and has several important limitations that affect the uncertainty in the estimates of likelihood and impact. The key scientific uncertainties and knowledge gaps in this assessment include transmissibility of the clade I MPXV circulating in the current DRC outbreaks and what the transmissibility would be in a non-endemic setting such as Canada, incubation period, period of communicability, severity of disease caused by clade I MPXV in a highly susceptible population (i.e., in a non-endemic setting), as well as duration of smallpox vaccine-induced immunity against clade I MPXV (see Table 2 below). A combination of clade I and clade IIb evidence was used to inform this risk assessment when necessary. Of note, evidence on clade I MPXV from before the current DRC outbreaks may exclude cases from sexual transmission (none reported until April 2023), which is a mode of transmission in the current outbreaks. Evidence from the 2022-2023 clade IIb outbreak captures sexual transmission events, but clade II is also associated with less severe disease and lower transmissibility than clade I in the pre-sexual transmission mpox literature.

The qualitative method used for the likelihood estimation also leads to an over-inflation of likelihood since the cumulative effect of probabilities less than 100% along the pathway will reduce the likelihood in a way that cannot be captured without quantitative data. This bias is in line with the use of the precautionary principle.

| Uncertainties identified | Unknown/more information needed |

|---|---|

| Introduction e.g., routes of introduction |

|

| Exposure e.g., incidence, prevalence |

|

| Susceptibility |

|

| Spread |

|

| Immediate/direct impacts e.g., mental health, morbidity/mortality, welfare |

|

| Longer-term/indirect impacts e.g., social, technological, economic, environmental, political and regulatory, population and health system |

|

| Interventions e.g., availability of effective medical countermeasures, public health measures |

|

Appendix A: Likelihood, impact and uncertainty scales

| Likelihood estimate | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Very High | Lack of data or reliable information; results based on crude speculation only |

| High | Limited data or reliable information available; results based on educated guess |

| Moderate | Some gaps in availability or reliability of data and information, or conflicting data; results based on limited consensus |

| Low | Reliable data and information available but may be limited in quantity, or be variable; results based on expert consensus |

| Very low | Reliable data and information are available in sufficient quantity; results strongly anchored in empiric data or concrete information |

| Likelihood estimate | Criteria |

|---|---|

| High | The situation described in the risk assessment question is highly likely to occur (i.e., is expected to occur in most circumstances) |

| Moderate | The situation described in the risk assessment question is likely occur |

| Low | The situation described in the risk assessment question is unlikely to occur |

| Very low | The situation described in the risk assessment question is very unlikely to occur (i.e., is expected to occur only under exceptional circumstances) |

| Estimate | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Severe | Severe impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) |

| Major | Major impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) |

| Moderate | Moderate impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) |

| Minor | Minor impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) |

| Minimal | Minimal or no impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) |

| Estimate | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Severe | Potential pandemic in the general population or large numbers of case reports, with significant impact on the well-being of the population. Severe impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income). Effect extremely serious and/or irreversible. |

| Major | Case reports with moderate to significant impact on the well-being of the population. Moderate to significant impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) affecting a larger proportion of the population and/or several regions. Effect serious with substantive consequences, but usually reversible. |

| Moderate | Case reports with low to moderate impact on the well-being of the population. Low to moderate impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) affecting a larger proportion of the population and/or several regions. Effect noticeable with important consequences, but usually reversible. |

| Minor | Rare case reports, mainly in small at-risk groups, with moderate to significant impact on the well-being of the population. Moderate to significant impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income) on a small proportion of the population and/or small areas (regional level or below). Effect marginal, but insignificant and/or reversible. |

| Minimal | No or very rare case reports with low to moderate impact on the well-being of the population. Negligible or no impact on mental health and/or disease morbidity/mortality, and/or welfare (e.g., loss of income). |

Appendix B: Acknowledgements

Completed by the Public Health Agency of Canada's Centre for Surveillance, Integrated Insights and Risk Assessment within the Data, Surveillance and Foresight Branch.

Clade I MPXV Rapid Risk Assessment Team

Public Health Agency of Canada: Rukshanda Ahmad, Raquel Farias, Fiona Guerra, Jacqueline Middleton, Oluwafemi Oluwole, Julia Paul, Sandra Radons Arneson, Marianne Stefopulos, Clarence Tam, Dana Tschritter, Shelley Veilleux, Jeyasakthi Venugopal, Linda Vrbova, Fushan Zhang

Mathematical modelling

Aamir Fazil, Vanessa Gabriele-Rivet, Valerie Hongoh, Lisa Kanary

The individuals listed below are acknowledged for their contributions to this report:

Other federal departments

Health Canada: Chris Hinds, Maya Bugorski, Gabriela Capurro Estremadoyro, Lidia Guarna, Fannie Ouellette, Isabelle Proulx

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada: Jessica Halverson, Elspeth Payne, Catherine Rutledge Taylor; Jenney Wang

Other individuals from various programs across PHAC

Melissa Abou-Eid, Lyne Bellemare, Alain Boucard, Tayler Brown, Andrea Chittle, Cindi Corbett, Mette Cornelisse, Lesley Doering, Courtney Dowd-Schmidtke, Mark Drouin, Nicole Forbes, Nick Giannakoulis, Stefanie Kadykalo, Maryam Kamkar, Natalie Knox, Julie Laroche, Melissa Lavigne, Marc-André LeBlanc, Andrew Mackenzie, Emma Mackey, Chand Mangat, Stacey Mantha, Joanna Merckx, Janice Merhej, Gila Metz, Joshua Muncaster, John Nash, Nicholas Ogden, Milan Patel, Kusala Pussegoda, Michael Routledge, David Safronetz, Erin Schillberg, Holly Sullivan, Ashleigh Tuite, Matthew Tunis, Jill Williams, Nathalie Vedrine, Lisa Waddell, Semhar Zerat

Footnotes

- Footnote a

-

At least one infected person entering Canada.

- Footnote b

-

Amplification event: Any event in which someone with mpox comes into contact with and subsequently exposes and infects more people than average (i.e., mass exposure). Such events can include but are not limited to: cruise ships, parties, sex on premises venues.

- Footnote c

-

Immunocompromised: Individuals with impaired immune response functions due to a variety of factors, including immunodeficiency disorders, treatment with immunosuppressives, cancer, unsuppressed HIV, and others.

References

- Reference 1

-

Okamba LP. Republic of Congo reports its first mpox virus cases, in several regions. Associated Press. March 14, 2024. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://apnews.com/article/congo-mpox-epidemic-outbreak-disease-7c72b0efda36703155689377263d5899.

- Reference 2

-

Ministère de la Santé publique, Hygiène et Prévention de la RDC, L'Organisation mondiale de la Santé. La variole simienne (monkeypox) en République démocratique du Congo: Évaluation de la situation Rapport de mission conjointe (22 novembre – 12 décembre 2023). Published February 19, 2024. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/la-variole-simienne-monkeypox-en-republique-democratique-du-congo-evaluation-de-la-situation-rapport-de-mission-conjointe-22-novembre-12-decembre-2023.

- Reference 3

-

Ministère de la Santé publique, Hygiène et Prévention de la RDC, L'Organisation mondiale de la Santé. La variole simienne (monkeypox) en République démocratique du Congo: Rapport de la Situation Epidemiologique Sitrep Nº004 (du 14 - 10 mars 2024). Published March 26, 2024. Accessed March 29, 2024. https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/la-variole-simienne-monkeypox-en-republique-democratique-du-congo-rapport-de-la-situation-epidemiologique-sitrep-no004-du-14-10-mars-2024.

- Reference 4

-

Ministère de la Santé publique, Hygiène et Prévention de la RDC, L'Organisation mondiale de la Santé. DR Congo: Rapport de la situation épidémiologiue de la variole simienne - sitrep no 1, 5-11 février 2024. Published February 23, 2024. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/dr-congo-rapport-de-la-situation-epidemiologiue-de-la-variole-simienne-sitrep-no-1-5-11-fevrier-2024.

- Reference 5

-

World Health Organization. 2022-23 Mpox (Monkeypox) Outbreak: Global Trends. Updated March 20, 2024. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/.

- Reference 6

-

Masirika LM, Udahemuka JC, Ndishimye P, et al. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and transmission patterns of a novel Mpox (Monkeypox) outbreak in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): an observational, cross-sectional cohort study. medRxiv. 2024. DOI: 10.1101/2024.03.05.24303395.

- Reference 7

-

Beer EM, Rao VB. A systematic review of the epidemiology of human monkeypox outbreaks and implications for outbreak strategy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(10):e0007791. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007791.

- Reference 8

-

Nolen LD, Osadebe L, Katomba J, et al. Extended Human-to-Human Transmission during a Monkeypox Outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(6):1014-1021. DOI: 10.3201/eid2206.150579.

- Reference 9

-

Wendorf KA, Ng R, Stainken C, et al. Household Transmission of Mpox to Children and Adolescents, California, 2022. J Infect Dis. 2023;229(Supplement 2):S203-S206. DOI: 10.1093/infdis/jiad448.

- Reference 10

-

Charniga K, McCollum AM, Hughes CM, et al. Updating Reproduction Number Estimates for Mpox in the Democratic Republic of Congo Using Surveillance Data. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2024;110(3):561-568. DOI: 10.4269/ajtmh.23-0215.

- Reference 11

-

Americo JL, Earl PL, Moss B. Virulence Differences of Monkeypox Virus Clades 1, 2a and 2b.1 in a Small Animal Model. PNAS. 2023;120(8):e2220415120. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2220415120.

- Reference 12

-

McCollum AM, Damon IK. Human monkeypox. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;58(2):260-267. DOI: 10.1093/cid/cit703.

- Reference 13

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Mpox (monkeypox) epidemiology update. Updated September 29, 2023. Accessed April 2, 2024. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/mpox/.

- Reference 14

-

Toronto Public Health. Toronto Public Health reminds residents to get vaccinated against mpox amid rise in local cases. City of Toronto. March 20, 2024. Accessed March 21, 2024. https://www.toronto.ca/news/toronto-public-health-reminds-residents-to-get-vaccinated-against-mpox-amid-rise-in-local-cases/.

- Reference 15

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Smallpox and mpox (monkeypox) vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide. Updated June 2023. Accessed March 25, 2024. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-21-smallpox-vaccine.html.

- Reference 16

-

Statistics Canada. Table 17-10-0005-01 Population estimates on July 1, by age and gender. Statistics Canada. Published February 21,2024. Accessed March 29, 2024. DOI: 10.25318/1710000501-eng.

- Reference 17

-

Dalton AF, Diallo AO, Chard AN, et al. Estimated Effectiveness of JYNNEOS Vaccine in Preventing Mpox: A Multijurisdictional Case-Control Study - United States, August 19, 2022-March 31, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(20):553-558. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7220a3.

- Reference 18

-

Sah R, Mohanty A, Padhi BK, et al. Monkeypox deaths in 2022 outbreak across the globe: correspondence. Ann Med Surg. 2023;85(1):57-58. DOI: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000000076.

- Reference 19

-

Sagy YW, Zucker R, Hammerman A, et al. Real-world effectiveness of a single dose of mpox vaccine in males. Nat Med. 2023;29(3):748-752. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-023-02229-3.

- Reference 20

-

Sorge JT, Colyer S, Cox J, et al. Estimation of the population size of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in Canada, 2020. CCDR. 2023;49(11/12):465- 476. DOI: 10.14745/ccdr.v49i1112a02.

- Reference 21

-

Xiu F, Flores Anato JL, Cox J, et al. Characteristics of the Sexual Networks of Men Who Have Sex With Men in Montréal, Toronto, and Vancouver: Insights from Canada's 2022 Mpox Outbreak. J Infect Dis. 2024;229(Supplement_2):S293–S304. DOI: 10.1093/infdis/jiae033.

- Reference 22

-

Berthaud-Clair S. Mpox: la RDC va homologuer en urgence deux vaccins et un traitement pour endiguer l'épidémie. Le Monde. April 15, 2024. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2024/04/15/ epidemie-de-mpox-la-rdc-va-homologuer-en-urgence-deux-vaccins-et-un-traitement_6227992_3212.html.

- Reference 23

-

Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Communiqué : United in the Fight Against Mpox in Africa – High-Level Emergency Regional Meeting. Published April 13, 2024. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://africacdc.org/news-item/communique-united-in-the-fight-against-mpox-in-africa-high-level-emergency-regional-meeting.

- Reference 24

-

World Health Organization, World Organization for Animal Health, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Joint Risk Assessment Operational Tool (JRA OT): An Operational Tool of the Tripartite Zoonoses Guide - Taking a Multisectoral, One Health Approach: A Tripartite Guide to Addressing Zoonotic Diseases in Countries. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, OIE, FAO; 2020:98. Accessed April 3, 2024. https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cb1520en/.

- Reference 25

-

World Health Organization. Rapid risk assessment of acute public health events. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2012:44. Accessed April 3, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/rapid-risk-assessment-of-acute-public-health-events.

- Reference 26

-

European Centre for Disease Control. Operational tool on rapid risk assessment methodology. Stockholm, Sweden: ECDC; 2019. Accessed April 3, 2024. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/operational-tool-rapid-risk-assessment-methodology-ecdc-2019.

- Reference 27

-

Leendertz S, Stern D, Theophil D, et al. A Cross-Sectional Serosurvey of Anti-Orthopoxvirus Antibodies in Central and Western Africa. Viruses. 2017;9(10):278. DOI: 10.3390/v9100278

- Reference 28

-

Ministère de la Santé Publique, Hygiène et Prévention de la RDC, L'Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. La variole simienne (monkeypox) en République démocratique du Congo: Rapport de la Situation Epidemiologique Sitrep Nº003 (du 19 - 25 février 2024). Published March 15, 2024. Accessed March 21, 2024. https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/la-variole-simienne-monkeypox-en-republique-democratique-du-congo-rapport-de-la-situation-epidemiologique-sitrep-no003-du-19-25-fevrier-2024.

- Reference 29

-

McFarland SE, Marcus U, Hemmers L, et al. Estimated incubation period distributions of mpox using cases from two international European festivals and outbreaks in a club in Berlin, May to June 2022. Euro Surveill. 2023;28(27):2200806. DOI: 10.2807/1560-7917.Es.2023.28.27.2200806.

- Reference 30

-

Paredes MI, Ahmed N, Figgins M, et al. Underdetected dispersal and extensive local transmission drove the 2022 mpox epidemic. Cell. 2024;187(6):1374–1386. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.02.003.

- Reference 31

-

Women and Gender Equality Canada. Pride Season. Updated July 7, 2023. Accessed March, 2024. https://women-gender-equality.canada.ca/en/pride-season.html.

- Reference 32

-

Statistics Canada. National Travel Survey microdata file. Updated 2022. Updated December 22, 2022. Accessed March, 2024. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/24-25-0001/242500012020001-eng.html.

- Reference 33

-

United Nations World Tourism Organization. International tourist departures per 1,000 people, 2021. Updated 2023. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/international-tourist-departures-per-1000.

- Reference 34

-

World Health Organization. Mpox (monkeypox) - Democratic Republic of the Congo. Disease Outbreak News. November 23, 2023. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON493.

- Reference 35

-

Kibungu E, Vakaniaki E, Kinganda-Lusamaki E, et al. Clade I–Associated Mpox Cases Associated with Sexual Contact, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. EID. 2024;30(1):172-176. DOI: 10.3201/eid3001.231164

- Reference 36