National Advisory Committee on Sexually Transmitted and Blood-Borne Infections (NAC-STBBI) Statement – Interim guidance for the treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal infections

Preamble

The National Advisory Committee on Sexually Transmitted and Blood-Borne Infections (NAC-STBBI) is an External Advisory Body that provides the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) with ongoing scientific and public health advice and recommendations for the development of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBI) guidance, in support of its mandate to prevent and control infectious diseases in Canada.

PHAC acknowledges that the advice and recommendations in this statement are based upon the best available scientific knowledge at the time of writing, and is disseminating this document for information purposes to primary care providers and public health professionals. The NAC-STBBI Statement may also assist policy makers or serve as the basis for adaptation by other guideline developers. NAC-STBBI members and liaison members conduct themselves within the context of PHAC's Policy on Conflict of Interest, including yearly declaration of interests and affiliations.

The recommendations in this statement do not supersede any provincial/territorial legislative, regulatory, policy and practice requirements or professional guidelines that govern the practice of health professionals in their respective jurisdictions, whose recommendations may differ due to local epidemiology or context. The recommendations in this statement may not reflect all the situations that may arise in professional practice, and are not intended as a substitute for clinical judgment in consideration of individual circumstances and available resources.

Table of contents

- Preamble

- Glossary of abbreviations and acronyms

- Objectives

- Summary

- Definitions and clarifications

- Background

- Methods

- Summary of the evidence

- Recommendations and rationale from other guidelines

- Systematic reviews and studies on the effects of NG treatment with combination therapy or monotherapy

- Canadian epidemiology/surveillance information

- Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cephalosporins in NG infections

- Evidence on patient values and preferences, feasibility, acceptability to stakeholders, equity and resource use

- Justification/Rationale

- Acknowledgements

- Appendices

Glossary of abbreviations and acronyms

- AMR

- Antimicrobial resistance

- ASHM

- Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine

- BASHH

- British Association for Sexual Health and HIV

- CDC

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- BCCDC

- British Columbia Centre for Disease Control

- CGSTI

- Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections

- CI

- Confidence interval

- CLSI

- Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute

- CT

- Chlamydia trachomatis

- DS

- Decreased susceptibility

- ECOFF

- Epidemiological Cut-Off Value

- ESAG

- Enhanced Surveillance of Antimicrobial-Resistance Gonorrhea

- EUCAST

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing.

- ƒT>MIC

- Time of the free drug concentration exceeding the MIC

- GASP

- Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (GASP-Canada)

- gbMSM

- Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men

- IM

- Intramuscular

- INESSS

- Institut national d'excellence de la santé et des services sociaux

- LSPQ

- Laboratoire de santé publique du Québec

- MIC

- Minimum inhibitory concentration

- NAAT

- Nucleic acid amplification test

- NAC-STBBI

- National Advisory Committee on Sexually Transmitted and Blood-Borne Infections

- NG

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- NML

- National Microbiology Laboratory

- MG

- Mycoplasma genitalium

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PID

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- PK/PD

- Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics

- QALY

- Quality-adjusted life year

- STI

- Sexually transmitted infection

- TOC

- Test of cure

- WHO

- World Health Organization

Objectives

The objectives of this work are:

- To update recommendations for preferred treatment regimens of uncomplicated NG infections

- To update the choice of test and timing of test of cure (TOC) and

- To clarify the recommendations to request culture of NG.

Summary

This statement provides recommendations 1) on preferred treatment for uncomplicated NG infection in adults and adolescents 10 years of age and older (Table 1); 2) for the choice of test and timing for NG TOC (Table 2); and 3) for requesting culture to obtain NG antimicrobial susceptibility.

Table 1: Updated recommendation on the preferred treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea in adults and adolescents 10 years of age and older

NAC-STBBI recommends ceftriaxone 500 mg IM as a single dose (monotherapy) for preferred treatment of all uncomplicated infections (urethral, endocervical, vaginal, rectal and pharyngeal).

Alternative treatment options, which are required if access to IM injection is not available, if the individual refuses the injection, or if the individual is severely allergic to cephalosporins, are currently under review by the NAC-STBBI. Refer to the following four alternative treatment regimens in the PHAC Gonorrhea Guide pending further review.

- Cefixime 800 mg PO in a single dose plus doxycycline 100 mg PO BID x 7 daysFootnote *

- Cefixime 800 mg PO in a single dose plus azithromycin 1g PO in a single dose

- Azithromycin 2 g in a single oral dose PLUS gentamicin 240 mg IM in a single doseFootnote *

- Gentamicin 240 mg IM a single dose PLUS doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 daysFootnote *

Notes:

- If C. trachomatis infection has not been excluded by a negative test, concurrent treatment for chlamydia is recommended; refer to the treatment recommendations in the PHAC Chlamydia and LGV Guide: Treatment and follow-up.

- Refer to PHAC Gonorrhea Guide: Treatment and follow-up for further details for each alternative treatment regimen, including the indications for use of ertapenem and also for information on partner notification and treatment.

- Test of cure (TOC) is recommended for all positive NG sites in all cases (refer to Table 2 below).

- The following alternative treatment regimens have been removed from the PHAC Gonorrhea Guide.

- Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM in a single dose PLUS doxycycline 100 mg PO BID x 7 daysFootnote **

- Azithromycin 2 g in a single oral dose PLUS ciprofloxacin 500 mg in a single oral doseFootnote **

- Azithromycin 2 g in a single dose plus gemifloxacin 320 mg in a single oral doseFootnote **

Table 2: Recommendation on the choice of test and timing

NAC-STBBI recommends a TOC for all positive NG sites in all cases. This is particularly important when regimens other than ceftriaxone 500 mg IM are used. Ideally, TOC samples should be taken for both culture and NAAT.

- A NAAT should be performed three to four weeks after the completion of treatment because residual nucleic acids from dead bacteria may be responsible for positive results less than three weeks after treatment.

- When a TOC is performed within three weeks after completion of treatment, a culture should be performed; samples should be taken at least three days after completion of treatment.

- When treatment failure is suspected more than three weeks after treatment, both NAAT and culture should be performed (for example, when symptoms persist or recur after treatment).

Table 3: Recommendation on NG culture

Although culture is less sensitive than NAAT, it provides the opportunity for antimicrobial susceptibility determination, which is important for case management and is critical for monitoring AMR patterns and trends.

NAC-STBBI recommends NG culture (together with NAAT) in the following situations:

- For a TOCFootnote * when treatment failure is suspected;

- In the presence of symptoms compatible with cervicitis, urethritis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), epididymo-orchitis, proctitis or pharyngitis;

- Asymptomatic individual who has notified as a contact of an NG infected case;

- When sexual abuse/sexual assault is suspected (this may vary according to legal and medical contexts of the jurisdiction);

- If the infection might have been acquired in countries or areas with high rates of AMR (NG resistant strains have been reported in Canada, Japan, Europe and Australia; many were associated with travel to South-East Asia).

In addition, NAC-STBBI recommends a culture when NG infection is confirmed by NAAT only, as long as it does not delay treatment.

Note:

- Successful culture requires proper collection and transportation of appropriate specimens. Consult with your local Public Health Laboratory for guidance on specimen collection and transportation.

Definitions and clarifications

- Uncomplicated Neisseria gonorrhoeaeFootnote a (NG) infections include anogenital (urethritis, cervicitis, and proctitis) and pharyngitis. Asymptomatic infections are common in the endocervical canal, and in pharyngeal and rectal sites in both men and women. Asymptomatic infections also occur at the urethral siteReference 1.

- Complicated NG infections can be local (those that extend locally beyond the primary site of infection, such as epididymitis and pelvic inflammatory disease), or disseminated (systemic complications which may include arthritis-dermatitis syndrome and rarely endocarditis or meningitisReference 1.

- The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) is the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial that will inhibit the visible growth of a microorganism after overnight incubation. The MIC is used to categorize a strain as susceptible, intermediate or resistant (Appendix 1: Table 1).

- According to the Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI), there is no established resistance breakpoint for ceftriaxone and cefixime. When the NG isolate has an MIC above the susceptibility breakpoint (0.25 mg/L for ceftriaxone and cefixime), it is considered "non-susceptible". For simplification, the term "resistant" has been used to describe these strains.

- Strains are considered to have decreased susceptibility (DS) to ceftriaxone (0.125-0.25 mg/L) or cefixime (0.25 mg/L) if they are still susceptible, but their MICs are close to the breakpoint.

- The term combination (or dual) therapy is used when the two antibiotics are directed towards NG treatment. This is different from using two antibiotics to treat presumed (as part of the syndromic approach) or confirmed co-infection with Chlamydia trachomatis (CT).

Background

General information

Gonococcal infection, caused by Gram-negative diplococcus Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG), represents a significant public health problem globally due to increasing rates, and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) to most antibiotics used for its treatment, and association with serious complications and sequelae when left undiagnosed and untreated, as well as HIV transmission and acquisitionReference 2Reference 3Reference 4Reference 5Reference 6Reference 7.

Treatment of gonorrhea has been complicated by the ability of NG to develop AMR. International travel can contribute to the spread of gonorrhea, including with resistant strainsReference 7. Optimal antimicrobial treatment for NG is important because it can cure gonorrhea and prevent long-term sequelae, decrease transmission, and slow the emergence and spread of AMR.

Variability in treatment recommendations

There is considerable variability in the treatment regimens recommended by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), provincial/territorial guidelines and international guidelines (Appendix 2). These differences are partially due to the differences in local AMR profiles, requiring the use of regionalized treatment recommendations. The recommendations vary between guidelines in terms of the following:

- Choice of preferred and alternate drugs

- Use of combination therapy vs. monotherapy

- Dosing regimens

Treatment recommendations may also vary within the guidelines based on patient-specific factors. For example, the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections (CGSTI) recommendations on gonorrhea are based on the following:

- Whether treating suspected (empiric treatment in symptomatic people) or confirmed NG infection (in either symptomatic or asymptomatic people)

- The syndrome associated with NG infection [cervicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), proctitis, urethritis, epididymo-orchitis]

- The site of infection (anogenital and pharyngeal)

- Key populations [e.g., ceftriaxone is preferred over cefixime as part of therapy for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM)]

Combination therapy vs. monotherapy and other factors affecting treatment recommendations

Combination therapy is used for different situations:

- To treat presumed NG or CT infection in a symptomatic individual before laboratory confirmation of infection.

- To treat possible undetected coinfection with CT when NG infection is confirmed. Addition of a drug against CT infection (azithromycin or doxycycline) has been used for many decades. However, with the introduction of nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) in the 1990s and the improvement of their analytical sensitivity (capacity of detecting very low numbers of bacteria) over time, as well as the adoption of the recommendation to test extragenital sites (when indicated), the probability of undetected CT infection may be very low.

- To treat potential AMR NG infection. Even when NG infection is confirmed, antimicrobial susceptibility results to guide therapy may not be available at the time of treatment, for a variety of reasons (sample for culture not taken, negative culture results, or antimicrobial susceptibility profile not yet available).

To address AMR in gonorrhea, the CGSTI treatment recommendations were regularly updatedReference 8Reference 9Reference 10:

- High rates of antimicrobial resistance to penicillins and tetracyclines have been reported, so these antimicrobials are no longer recommended for the treatment of NG infections;

- Fluoroquinolones were removed as first-line treatment in 2008;

- Doses of third-generation cephalosporins (ceftriaxone and cefixime) were doubled in 2011;

- Combination therapy has been recommended since 2011;

- The dose of cefixime was increased from 400 mg to 800 mg based on surveillance data of higher MICs being for NG;

- Monotherapy with azithromycin 2 g orally as a single dose and as an alternative in those with anaphylactic reactions to penicillin or allergy to cephalosporins is no longer recommended [gentamicin 240 mg intramuscularly (IM) in combination with azithromycin 2 g orally was introduced in 2017].

However, the relevance and appropriateness of combination therapy, particularly the role of azithromycin, has recently been called into question due to:

- Increasing resistance of NG to azithromycin and other antibiotics in many countries, including Canada.

- Increasing resistance of other microorganisms to azithromycin [e.g., M. genitalium (MG), T. pallidum] directly linked to azithromycin use, thus limiting their treatment optionsReference 11Reference 12Reference 13.

- Other considerations for antimicrobial stewardship, such as side effects, costs, concerns about the effects of antibiotics on individual microbiome and AMR of other bacteria (for example Streptococcus pneumoniae)Reference 14Reference 15Reference 16Reference 17Reference 18.

Given the growing uncertainty related to existing recommendations, the National Advisory Committee on Sexually Transmitted and Blood-Borne Infections (NAC-STBBI) advised PHAC to reassess the NG treatment recommendations, while taking into consideration patient values and preferences, impact on healthcare providers and realities of health care systems including access to culture for NG and access to injectable drugs on site and costs.

Methods

NAC-STBBI provides PHAC with ongoing scientific and public health advice and recommendations for the development of STBBI guidance, in support of its mandate to prevent and control infectious diseases in Canada. A Working Group composed of eight experts from the NAC-STBBI was formed to review the existing PHAC recommendations on NG treatment following the methodology for developing recommendations by NAC-STBBI and PHACReference 19Reference 20Reference 21Reference 22. The Working Group received methodological and technical support from the PHAC Secretariat and from an external methodology expert.

The recommendations included herein consist of an interim guidance; the final recommendations will be available after the completion of a review of primary studies currently underway.

Review of relevant guidelines and of literature

PHAC in collaboration with the Working Group conducted a scoping exercise (a review) of relevant guidelines on treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea in symptomatic or asymptomatic adults and adolescents, including pregnant and non-pregnant individuals, to support the development of the recommendationsReference 23. The Google search engine was used to identify relevant guidelines. The websites of several international guideline development organizations, as well as provincial guideline groups, were also searched. Appendix 2 shows the list of organizational websites searched. For the identified guidelines, information on the type of evidence and the rationale that supported the development of the recommendations were gathered.

PHAC, in collaboration with the Working Group, also conducted a search for systematic reviews and a sample of primary studies on the effects of treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea in symptomatic or asymptomatic adults and adolescents, including pregnant and non-pregnant individuals to support the development of the recommendations. Information sources, including Ovid MEDLINE® All, Embase and EBM Reviews – Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, were searched with the support of a Health Canada librarian from January 1st 2010 to February 2020 and updated in 2023. No study design limit was applied. Although a comprehensive/systematic review of the literature was not undertaken, a sample of relevant primary studies were identified and considered. The sample of primary studies included to support the development of the recommendations were identified by selecting the first four of the relevant studies during the screening of titles, abstracts and full-text records. A targeted search of the literature was performed for evidence on patient values and preferences, feasibility, acceptability, equity and resource use. A manual search of the reference lists of the included sample of primary studies, reviews and guidelines was performed to identify other relevant publications. Working Group members were also asked to share any studies on the topic. Titles, abstracts, and selected full-text articles were screened based on predefined inclusion criteria, and data were extracted by a reviewer. Reviews and primary studies of any design that were conducted in a healthcare setting in Canada and other high-income countries that examined the effects of monotherapy or combination therapy on uncomplicated gonorrhea were included. Only studies published in English or French were included. A narrative synthesis was prepared.

Canadian surveillance data

Latest available data on notified cases of NG infectionsReference 24, AMR, and treatment failures were considered in the development of the treatment recommendations. Data were gathered from PHAC, provincial publications, and personal communication with experts at the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) in Canada.

Since 1985 the Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (GASP – Canada), a passive national surveillance program where provincial and territorial partners send NG isolates obtained from cultures to the NML, has been in operationReference 25. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing with a panel of antimicrobials and molecular characterization are performed on all cultured isolates, and results are published on an annual basisReference 26. Some provincial reference laboratories also conduct AMR surveillance. For example, the Laboratoire de santé publique du Québec (LSPQ) publishes yearly reports on NG AMR, the latest one being for the year 2021Reference 27.

PHAC launched the Enhanced Surveillance of Antimicrobial-Resistance Gonorrhea (ESAG) program in 2013 in three jurisdictions (Alberta, Manitoba, and Nova Scotia) to improve the understanding of current trendsReference 28. In 2017, an additional jurisdiction, the Northwest Territories, was added. This enhanced laboratory-epidemiological linked surveillance program collects data not available via its existing routine and laboratory surveillance, including treatment information and risk factors. All cultures and data from participating jurisdictions are included in the surveillance program. The NML performs antimicrobial susceptibility testing on a standard set of antimicrobials and sequence typing.

A similar program (Réseau sentinelle de surveillance de l'infection gonococcique, de l'antibiorésistance et des échecs de traitement au Québec) has been ongoing with data available from 2015 to 2019 in three regions of the province of QuébecReference 29. Its main objectives were to 1) promote culturing of isolates to maintain AMR surveillance capacity, 2) collect epidemiologic and clinical data to examine factors associated with antibiotic susceptibility, and 3) detect and characterize treatment failures.

Other types of evidence

Other types of evidence were also considered, including expert opinion and pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) studies. The PK/PD data were collected from the literature.

Management of competing interests

Conflicts of interest were managed according to PHAC guidelines. No conflicts of interest were declared by the NAC-STBBI prior to discussion and voting on the recommendations. The entire NAC-STBBI reviewed this statement and voted on the recommendations. External peer-reviewers (outside of the NAC-STBBI) with expertise in infectious diseases were identified and engaged prior to the publication of the recommendations.

Summary of the evidence

Recommendations and rationale from other guidelines

As detailed in Appendix 2, 13 guidelines published between 2013 and 2021 on gonorrhea treatment were identified.

The CGSTI guidelines (2013, 2021) recommend:

For anogenital infections:

- Preferred treatment:

- ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus azithromycin 1 g orally in a single dose OR

- cefixime 800 mg orally in a single dose plus azithromycin 1 g orally in a single dose (the cefixime regimen is considered an alternative therapy for gbMSM)

- Alternative treatment if there is a macrolide resistance or contraindication to macrolide:

- ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day x 7 days OR

- cefixime 800 mg orally in a single dose plus doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day x 7 days

For pharyngeal infections:

- Preferred treatment:

- ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus azithromycin 1 g orally in a single dose

- Alternative treatment:

- cefixime 800 mg orally in a single dose plus azithromycin 1 g orally in a single dose

In 2020, the Québec guidelines were updated to recommend ceftriaxone monotherapy at a dosage of 250 mg as the sole option for pharyngeal infections and as one of two options for anogenital infections, the other being a combination of cefixime 800 mg with azithromycin 2 gReference 30. The decision to offer an alternative regimen to ceftriaxone IM was based on the necessity to have access to an oral regimen in the current healthcare system context. The addition of azithromycin 2 g to cefixime was based on the poor performance of cefixime treatment alone, in particular with pharyngeal infections.

The recommended dose of ceftriaxone and azithromycin (in combination therapy) varies between guidelines. Doses of ceftriaxone range from 250 mg IM to 2 g IM as a single dose; and doses of oral azithromycin range from 1 g to 2 g. World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines (2016)Reference 31 additionally recommend combination therapy with cefixime plus azithromycin as oral first-line treatment for anogenital infection. Doses of oral single-dose cefixime range from 400 mg to 800 mg. The recommendations for combination therapy with ceftriaxone plus azithromycin and the various dosing regimens were based on earlier/older clinical trials, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic simulations, AMR surveillance data, anticipated/predicted trends in AMR, case reports of treatment failures, and expert consultations/opinion.

Additionally, the recommendations to treat gonorrhea with two antibiotics are based on hypotheses that using two antibiotics with different mechanisms of action may improve or enhance the effectiveness of treatment, may reduce the transmission of resistant strains, and may help delay the emergence and progression of resistance to cephalosporins. The evidence to support these hypotheses comes from laboratory studies and case seriesReference 32Reference 33Reference 34Reference 35. Despite the paucity of clinical data, guidelines cited that some studies suggest that ceftriaxone and azithromycin combination therapy may reduce the development of resistance to cephalosporinsReference 36 and combination therapy may also treat concurrent CTReference 37Reference 38 and a proportion of MG infectionsReference 39.

According to the British Association of Sexual Health and HIV( BASHH)Reference 40, among the reasons to remove azithromycin, in addition to antibiotic stewardship, are fears of accelerating the induction and spread of resistance in other STIs such as MG and Treponema pallidum. BASHH now recommends monotherapy with ceftriaxone 1 g for all sites of infection. The recommendation is supported by pharmacodynamic analyses, suggesting that a 1 g dose of ceftriaxone would result in fewer treatment failuresReference 41. A high dose of cephalosporin, 1 g in single dose (IV) has also been recommended by other national guidelines such as the Japanese guidelines for treating gonococcal infectionsReference 42Reference 43.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has also removed azithromycin from prior regimens because of potential harm to the microbiome and potential emerging resistance in other pathogensReference 14. The preferred regimen for all sites of infection is ceftriaxone monotherapy given IM with dosing based on the patient's body weight (500 mg or 1 g if ≥150 kg). If ceftriaxone is not available, the alternative regimens for anogenital infection are gentamicin 240 mg IM plus azithromycin 2 g orally OR cefixime 800 mg orally. The CDC does not recommend alternative treatment for pharyngeal infections. In all cases, if chlamydia infection has not been excluded, concurrent treatment with doxycycline (100 mg orally twice a day for 7 days) is recommendedReference 14.

In contrast, the Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine (ASHM) continues to recommend 500 mg ceftriaxone plus 1 g azithromycin for genital and anorectal infections but increased the azithromycin dose to 2 g for pharyngeal infections (Appendix 2). The working group members of the Communicable Diseases Network of Australia noted that oropharyngeal infections pose a greater challenge to the selection of ceftriaxone and azithromycin resistance, as lower levels of mucosal drug penetration can occasionally lead to treatment failures, even with gonococcal strains sensitive to ceftriaxone and azithromycinrReference 44. Increasing low-level resistance to azithromycin among Australian gonococcal isolates is the basis for the recommendation to increase the dose of oral azithromycin from 1 g to 2 g, as part of combination therapy, for the treatment of confirmed pharyngeal gonorrhea. The rationale provided for the increased dose was based on the report that "gonococcal strains determined to have low resistance to azithromycin, where azithromycin minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) are at or just above the breakpoint for clinical treatment failure, are more likely to respond to a single 2 g oral dose than to a single 1 g oral dose"Reference 45.

The 2020 European guideline for gonorrhea treatment continues to recommend combination therapy with 1 g ceftriaxone plus 2 g azithromycinReference 36. The authors of the guideline highlighted the following regarding combination therapy:

- It aims to provide cure for all gonorrhoea cases and, accordingly, to delay the emergence or spread of multi-drug resistance and particularly ceftriaxone resistance.

- It has very high cure rates; effectively targets both intracellular and extracellular bacteriaReference 46.

- It has likely been involved in decreasing the level of resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins (mainly ceftriaxone and cefixime) internationally and inhibiting the spread of cephalosporin-resistant and azithromycin resistant gonococcal strains, because concurrent resistance to ceftriaxone and azithromycin has been exceedingly rare globally.

- It may eradicate effectively concomitant CT infections and a proportion of MG infections, and adherence appears high.

Systematic reviews and studies on the effects of NG treatment with combination therapy or monotherapy

A total of 11 systematic reviewsReference 47Reference 48Reference 49Reference 50Reference 51Reference 52Reference 53Reference 54Reference 55Reference 56Reference 57 published between January 2010 and February 2021 were identified. In addition, although a systematic review was not undertaken for publications after August 2020 (the latest date of search included in the systematic reviews), four primary studiesReference 43Reference 58Reference 59Reference 60 were considered to be of importance to guide the interim recommendations. The characteristics of the included studies are available in Appendix 3.

All infection sites (urogenital, rectal and pharyngeal sites)

A recent systematic review with network meta-analysis of monotherapy for the treatment of NG infections at all sitesReference 55 compared the effects of injectable drugs with each other, and oral drugs to each other. Of the 44 included randomized controlled trials, nine had a total of 683 patients who were treated with ceftriaxone at 125 or 250 mg doses. It was found that ceftriaxone resulted in greater odds of cure compared to all other injectable drugs. When comparing cefixime (800 mg) to other oral drugs, cefixime resulted in greater odds of cure, except when compared to azithromycin 1g or ofloxacin.

A review by Bai (2012)Reference 47 reported on studies published in 1991 and 1992 that directly compared ceftriaxone to cefixime: three studiesReference 61Reference 62Reference 63 compared ceftriaxone 250 mg IM (n=234) and cefixime 400 mg (n=348), and two studiesReference 61Reference 63 compared ceftriaxone 250 mg IM (n=157) and cefixime 800 mg (n=142). The results included greater odds of cure with ceftriaxone 250 mg compared to cefixime 400 mg (OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.11 to 2.80). However, no difference was found when compared to cefixime 800 mg [OR 1.19, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.19 to 7.39]. These results must be interpreted with caution as the original studies were conducted more than 30 years ago, and numbers were small, as reflected by the wide 95% CI.

Since the publication of the systematic reviews, an open label randomized controlled trial was conducted in Hai Phong, Vietnam among 125 NG and CT co-infected individualsReference 60. Both groups received doxycycline orally twice a day for 7 days to treat CT infection. For NG infection, one group received a single 1 g IV dose of ceftriaxone (n=61, among which 21 had pharyngeal infection) and the other group received a single 800 mg oral dose of cefixime (n=64, among which 19 had pharyngeal infection). Overall cure rates for NG infections were 96.7% (95% CI 88.8–99.1%) with ceftriaxone (and doxycycline) and 95.3% (95% CI 87.1–98.4%) for cefixime (and doxycycline). Treatment failures were observed only among participants with pharyngeal infections: clearance of NG pharyngeal infection on the 8th day was 19/21 (90%) in those treated with ceftriaxone and 14/19 (74%) in those treated with cefixime.

In a retrospective observational studyReference 59, surveillance data from China was used to compare the effects of various doses of ceftriaxone (250 mg IM, 500 mg IM, ≥ 1 g IV; n=1401), unspecified dose of cefixime (n=119), and other extended-spectrum cephalosporins for the treatment of uncomplicated NG infections among 1686 participants. The prevalence of isolates with DS to ceftriaxone [MIC ≥0.125 mg/L] was 9.8% (131/1333). All the patients recruited in this study were cured, regardless of the isolates' susceptibility to ceftriaxone or the dosage of ceftriaxone they received.

Anorectal site

The systematic review by Lo et al. (2021)Reference 57 found that the proportion of cures with mono- or combination therapy including ceftriaxone at various dosages (125 mg, 250 mg or 500 mg) for rectal gonorrhoea was 100.0% (95% CI: 99.9%–100.0%). The cure rates with monotherapy (100.0%; 95% CI: 99.88%–100.0%) and combination therapies (100.0%; 95% CI: 97.65%–100.0%) were similar.

Pharyngeal site

Kong et al. (2020)Reference 56 assessed the effects of treatment for pharyngeal infection from randomized controlled trials. They reported 98.1% (95% CI: 93.8%-100%; I2 = 57.3%; P < 0.01) microbiological cure across all treatments for pharyngeal gonorrhea. The proportion of cure with monotherapy (97.1%; 95% CI 90.8–100.0) and combination therapies (98.0%; 95% CI 91.4–100) was similar. Of the 19 treatment regimens assessed in this systematic review and meta-analysis, two included ceftriaxone monotherapy, one included cefixime monotherapy, and three included ceftriaxone combined with azithromycin.

The summary estimates for microbiological cure were:

- Ceftriaxone 250 mg (Hook III 2014Reference 64, n=13): 100% (95% CI 77.2-100)

- Ceftriaxone 125 mg (Ramus 1997Reference 65, n=5): 100% (95% CI 56.6-100)

- Cefixime 400 mg (Ramus 1997Reference 65, n=6): 100% (95% CI 61.0-100)

- Ceftriaxone 500 mg with azithromycin 2 g (Rob 2019Reference 66, n=33): 100% (95% CI 89.6-100)

- Ceftriaxone 500 mg with azithromycin 1 g (Chen 2015Reference 67, n=19): 100% (95% CI 83.2-100)

- Ceftriaxone 500 mg with azithromycin 1 g (Ross 2016Reference 68, n=113): 95.6% (95% CI 90.0-100)

In this SR, the study on cefixime was conducted more than 25 years ago with only six participants who had NG and were given a dosage of 400 mgReference 65. For ceftriaxone monotherapy, only 18 participants with NG were included (125 mg or 250 mg), with 100% microbiological cure ratesReference 64Reference 65. These two studies were conducted more than 10 years ago. They also reported summary estimates on side effects, specifying considerable heterogeneity among studiesReference 56:

- Overall, 13.7% (95% CI: 9.2%–19.0%) reported nausea, which appeared more frequent for dual regimens that included azithromycin 2 g.

- Overall, 1.8% (95% CI: 0.9%–3.0%) reported vomiting, with little variation by treatment regimens.

- Overall, 15.8% (95% CI: 9.2%–23.8%) reported diarrhoea, which was more commonly reported for dual regimens using azithromycin 2 g.

A prospective observational study was conducted among asymptomatic MSM aged > 19 years diagnosed with extragenital NG infections in Tokyo, JapanReference 43. Participants were treated with 1000 mg IV ceftriaxone monotherapy (158 participants with NG infection only: 88 with pharyngeal infection, 20 with rectal infection and 50 with pharyngeal and rectal infection) or combination therapy (72 participants with CT coinfection: one with pharyngeal infection, 11 with rectal infection and 50 with pharyngeal and rectal infection). The combination therapy consisted of 1 g IV ceftriaxone combined with a single oral dose of 1 g azithromycin (n=19), 100 mg doxycycline administered orally twice daily for 7 days (n=89) or another antibiotic (n=4). The test of cure (TOC) was performed at least 2 weeks after treatment in participants with pharyngeal infection and at least 3 weeks after treatment in participants with rectal infection. Nine treatment failures (pharynx=5; rectal=4) were identified in eight participants (the TOC was positive at the pharyngeal and the rectal sites in one participant). In those participants, the TOC was performed 20 to 409 days after treatment, making it difficult in some of the individuals to distinguish between reinfection and treatment failure. The microbiological efficacy between monotherapy and combination therapy was similar. Efficacy against pharyngeal and rectal infections in the monotherapy group was 97.8% (135/138, 95% CI: 93.8–99.4%) and 98.6% (69/70, 95% CI: 92.3–99.9%), respectively, and in the combination therapy group was 96.1% (49/51, 95% CI: 86.8–99.3%) and 95.1% (58/61, 95% CI: 86.5–98.7%), respectively.

A literature review by Creighton et al. (2014)Reference 50 found a cure rate for pharyngeal infection of 80% and 92% for cefixime 800 mg and 400 mg respectively. For ceftriaxone 125 mg and 250 mg the cure rates are 94.1% and 99% respectively. These studies were published earlier and may not represent current resistance pattern.

Overall, published systematic reviews and a sample of primary studies suggest that the percentages of cures are similar with combination therapy or monotherapy, and that ceftriaxone 250, 500 or 1000 mg may result in greater cure rates than cefixime 400 mg, with or without the addition of azithromycin.

Canadian epidemiology/surveillance information

There has been a gradual and steady increase in reported NG infection cases since 1997. In 2019, 35,443 cases of gonorrhea were reported in Canada, corresponding to a rate of 94.3 cases per 100,000 population. Between 2010 and 2019, the rates have almost tripled (182% increase)Reference 24.

Rates of gonorrhoea were consistently higher among males compared to females. In 2019, two thirds of cases were among males, among whom rates were 228% higher than in 2010; in females rates increased by 121% during the same periodReference 24. Over the 2010-2019 decade, the highest rate of gonorrhea cases was among those aged 20 to 29 years. Since 2010, all age groups experienced an increase in rate. However, the magnitude of the change in rate over time varied by age group. The greatest relative increase was in the 30 to 39 and 40 to 59-year age groups, up 368% and 331% respectively, since 2010Reference 24.

AMR NG: current situation internationally and in Canada

AMR NG is a global public health challengeReference 69Reference 70. DSFootnote b and resistance in NG to ceftriaxone has been reported in 24% of countries participating in the WHO Global Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Program from 2015 to 2016 and 31% from 2017 to 2018Reference 71Reference 72. In addition, more countries have reported increased resistance to azithromycin: 81% from 2015 to 2016 and 84% from 2017 to 2018Reference 71Reference 72.

Seven cases of ceftriaxone-resistant NG have been identified in Canada between 2017 and 2023Reference 25Reference 73Reference 74, all of these were also cefixime-resistant. JapanReference 75, AustraliaReference 76, ChinaReference 77Reference 78, DenmarkReference 79 and IrelandReference 80 are a few of the other countries that have also identified ceftriaxone-resistant NG. Five of the seven Canadian ceftriaxone-resistant isolates have the same AMR associated mutations seen in Japan and AustraliaReference 77. The two ceftriaxone resistant isolates identified in March and April 2023 were from Central and Western Canada (unpublished data). The case from Central Canada was a symptomatic man who reported one sexual encounter with a woman. He had not recently travelled out of the province. Empiric treatment with 250 mg ceftriaxone and 1 g azithromycin was effective as demonstrated by a negative TOC (by culture) collected 18 days post-treatment. The case from Western Canada was acquired in South-East Asia and was successfully treated using ceftriaxone 1 g IV and doxycycline 100 mg twice a day x 14 days as demonstrated by a negative TOC (by NAAT) collected 30 days post-treatment. These two cases were not related based on differences in their genetic sequence typing results. Also of concern, the United Kingdom has reported an isolate with both ceftriaxone-resistance and high-level azithromycin-resistance that led to failure of treatment in 2018Reference 81. While an isolate with this type of resistance has not been identified in Canada, there have been 12 isolates with DS to cephalosporins identified between 2016 and 2022.

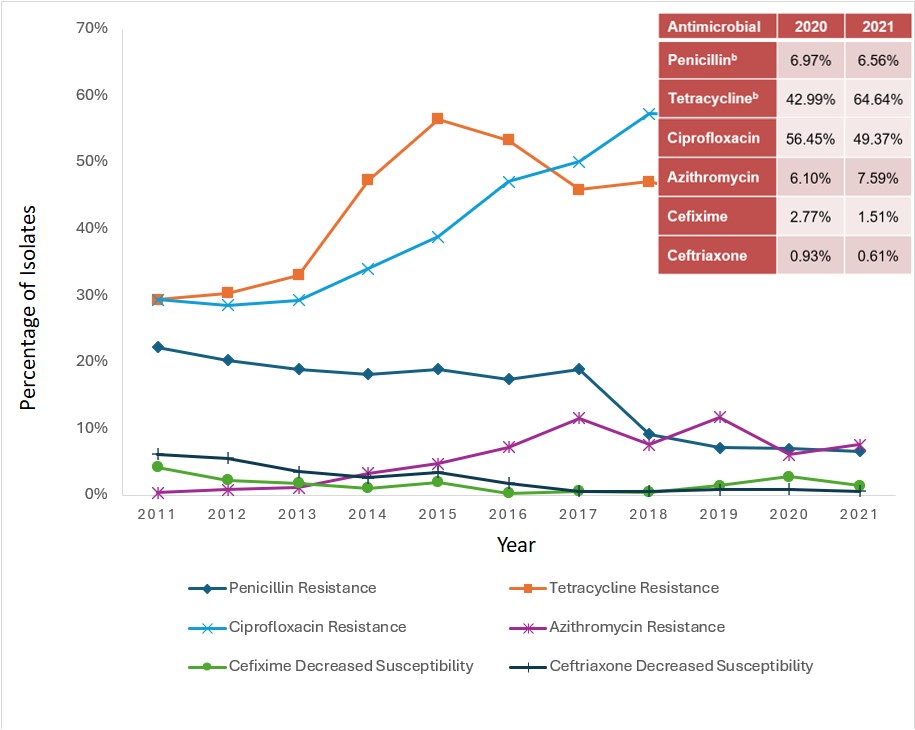

Data from GASP-Canada indicates that the proportion of strains with DS to ceftriaxone remained stable between 2017-2021 (0.6% in 2021). However, DS to cefixime increased between 2017 (0.6%) and 2020 (2.8%) and then decreased to 1.5% in 2021 (Appendix 1 – Figure 1).

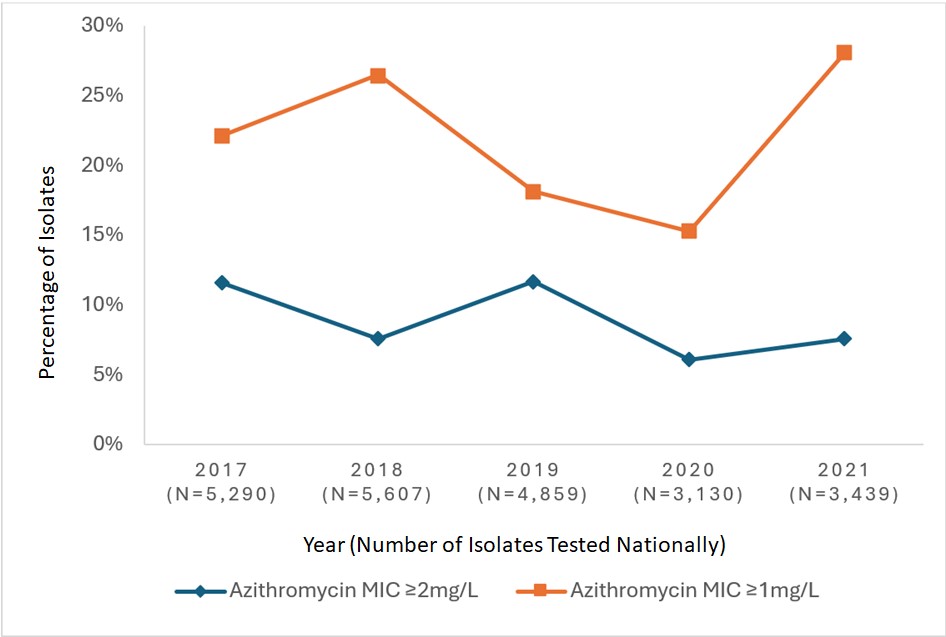

Data from GASP-Canada shows that azithromycin-resistance has increased in Canada (Appendix I – Figure 2). At 7.2% in 2016, it has surpassed the 5% resistance cut-off recommended by the WHO to trigger a review of current recommended therapiesReference 82. Since then, the proportion of azithromycin-resistant strains has fluctuated between 6.1% and 11.7%. In 2021, 7.6% of NG isolates were resistant to azithromycin. The CLSI recommended breakpoint for azithromycin is 2 mg/LReference 83, with a note informing that "this breakpoint presumes that azithromycin (1 g single dose) is used in an approved regimen that includes an additional antimicrobial agent, i.e., ceftriaxone 250 mg IM, single dose". However, some countries, including Australia, have set their breakpoint at 1 mg/L, which is also the Epidemiological Cut-Off Value (ECOFF) from EUCASTReference 84Reference 85. The proportion of NG isolates with an azithromycin MIC ≥1 mg/L increased significantly (p<0.001) over the last years in Canada, from 11.6% in 2016 to 28.1% in 2021.

In 2021, the proportion of NG isolates resistant to ciprofloxacin was 57%; tetracycline resistance was at an all-time high of 64%, erythromycin resistance was 51.5% and penicillin resistance was below 7% (Appendix 1 – Figure 1).

The ESAG system includes data on AMR from four provinces and territories (Alberta, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, and the Northwest Territories). Between 2014 and 2017, ESAG captured 2,767 cultures from 2566 cases. The majority of the cases were males (81%) and less than 40 years old (83%). From 2014 to 2017, there was a 25% decrease in the number of cases from MSM. The proportion of isolates demonstrating AMR to at least one antibiotic agent increased from 54% in 2014 to 66% 2016, and then decreased to 58% in 2017Reference 86.

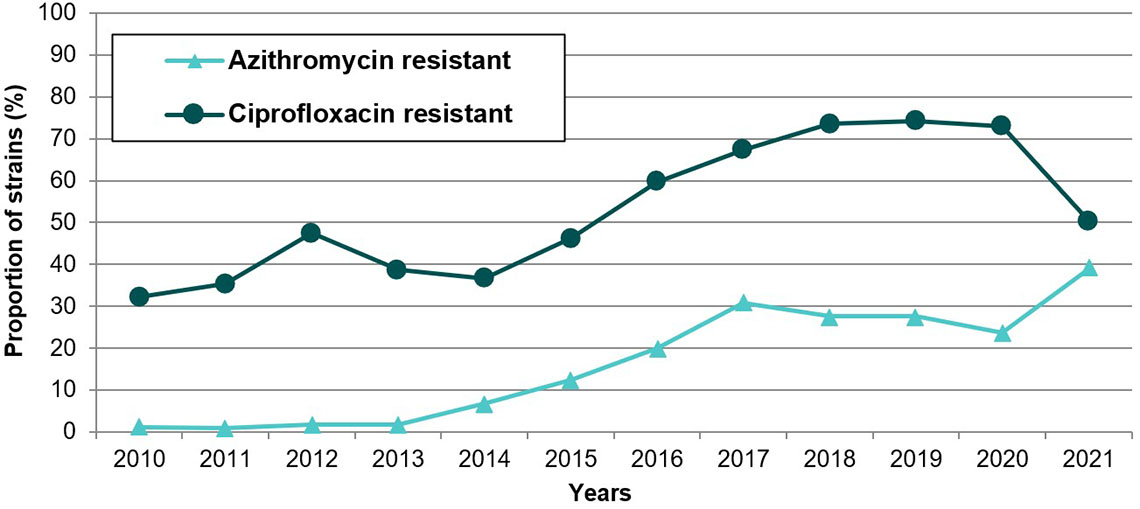

In Quebec, one ceftriaxone resistant strain was identified in 2017Reference 73. Since then, all strains have been susceptible to ceftriaxoneReference 27. The first two cefixime resistant strains were identified in 2015 (0.2%), with a peak of 12 strains in 2019 (0.7%). All strains (n=1520) tested in 2021Reference 27 and 2022 (personal communication with Brigitte Lefebvre) were susceptible to cefixime (MIC ≤0.25 mg/L). From 2011 to 2021, DS to ceftriaxone (MIC 0.12-0.25 mg/L) ranged from 0 to 3.9% and DS to cefixime (MIC 0.25 mg/L) ranged from 0.2 to 1.9%. However, no increasing trend has been observed: the highest rates of DS to ceftriaxone were found in 2014 and 2015; they vary from 0 to 0.3% since 2017. On the other hand, resistance to azithromycin increased from 1.0% in 2011 to 39.0% in 2021Reference 27. It is noteworthy that most resistant strains had an azithromycin MIC of 2 mg/L, which is the breakpoint for resistance (strains with an MIC of 1 mg/L -one dilution below- are considered susceptible). For example, in 2021, 561/593 (95%) resistant strains had an azithromycin MIC of 2 mg/LReference 27.

Overall, in Canada, resistance to ceftriaxone or cefixime has been reported, but remains rare. The proportion of strains with DS to ceftriaxone remains low and stable, but DS to cefixime appears to increase (remaining below 2%). A worrying increase in azithromycin resistance (7.6%) has been observed, which is above the 5% cut-off established by WHO. In addition, 20.5% of strains harbor an azithromycin MIC of 1 mg/L, which is only one dilution below resistance threshold.

Treatment failures surveillance in Canada

An ESAG report (2017) indicates that test of cures and treatment failures can be difficult to measure using surveillance data, as they rely on the ability to detect negative results. Also, people may not return to the same clinic for their test of cure, if they return at allReference 87.

ESAG data indicates that in 2016 and 2017, less than 0.5% of (5/1452) cases of gonorrhea with cultures reported to ESAG were classified as potential treatment failures by the public health nurse assessing the case. However, none of these five cases demonstrated resistance to cephalosporins (i.e., cefixime or ceftriaxone)Reference 28. Among the 5 cases of potential failure, the anatomical sites of infection and treatment received were as follows:

- Pharyngeal: a single dose of ceftriaxone 250 mg combined with azithromycin 1 g

- Pharyngeal: a single dose of azithromycin 2 g

- Cervical: a single dose of cefixime 800 mg combined with azithromycin 1 g

- Cervical: a single dose of cefixime 800 mg combined with azithromycin 1 g

- Pharyngeal: a single dose of cefixime 800 mg combined with azithromycin 1g.

In the Québec sentinel network (2015-2019), a TOC was performed in 1,596 included episodes of NG infection (63% of all episodesReference 29. The TOC was positive for 83 episodes (5%), among which 57 had sufficient collected information to enable classification (according to pre-established definitions) between reinfection (documented re-exposure) or treatment failure. Among the 18 cases for whom treatment failure was considered probable or possible, the treatments received wereReference 29:

- A single dose of ceftriaxone 250 mg combined with azithromycin 1 g (n=10)

- A single dose of cefixime 800 mg combined with azithromycin 1 g (n=3, including two who had confirmed pharyngeal infection)

- A single dose of azithromycin 2 g monotherapy (n=2)

- A single dose of azithromycin 1 g monotherapy, followed eight days later by a single dose of cefixime 800 mg (n=1)

- A seven-day course of doxycycline 100 mg twice a day (n=1)

- A single dose of ceftriaxone 250 mg monotherapy (n=1).

Overall, treatment failures have been reported in Canada, even when ceftriaxone is combined with azithromycin. Because of the small number of events, it is difficult to identify whether a specific regimen is more associated with failure. To determine whether failures are increasing over time, surveillance would need to be maintained and expanded.

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cephalosporins in NG infections

Since 2016, the WHO has recommended combination treatment using cephalosporin with azithromycin as a mainstay for gonorrhea therapy, due to the potential for NG to develop antimicrobial resistance. In general, first-line therapies for uncomplicated gonorrhea infections have efficacy rates of over 99%; however pharyngeal infections are more difficult to treat with cure rates of less than 90% with non-ceftriaxone-based therapies, which is possibly due to reduced oropharyngeal tissue penetrationReference 88. For pharyngeal infections, ceftriaxone remains the only recommended treatment, even though it has high protein binding and low concentrations in tonsillar tissue, so its pharmacodynamics activity is less understoodReference 88.

For beta-lactam antibiotics, the pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) parameter associated with clinical activity is the time of the free drug concentration exceeding the MIC (ƒT>MIC)Reference 89. Jaffe et al. (1979)Reference 90 proposed that the optimal ƒT >MIC for penicillin was 7 to 10 hours for clinical efficacy in the treatment of male urethritis, and this target was assumed to apply to cephalosporins for gonococcal infectionsReference 41Reference 91. Based on more recent clinical and PK-PD modelling data with ceftriaxone and cefiximeReference 41, Chisholm et al. (2010) hypothesized that a target ƒT>MIC of ~20 to 24 hours is required for optimal activityReference 41Reference 92. However, the ideal PK-PD criteria for pharyngeal gonorrhea remains unclearReference 88.

In response to surveillance data showing an increase in NG isolates with reduced susceptibility to cefixime, some experts have suggested using an increased dose of cefixime or multiple doses to overcome rising MICs. In a pharmacokinetic study, Barbee et al. (2018)Reference 93 examined the use of higher cefixime single dose regimens (cefixime 400 mg, 800 mg, and 1200 mg) and cefixime 800 mg orally every 8 hours for 3 doses to treat theoretical pharyngeal infections by NG with an MIC ≥ 0.5 mg/L. They found that none of the single dose regimens achieved the proposed target total serum concentration of 2.0 mg/L (4 times above the MIC of 0.5 mg/L) for more than 20 hours, and only 50% of cases who received the multi-dose cefixime regimen attained the target. In addition, pharyngeal fluid concentrations were negligible for all of the cefixime dosing regimensReference 93. It is important to note that total serum cefixime concentrations (and not active free unbound cefixime concentrations) were used in this study and the proposed target concentration of 2.0 mg/L was relatively high, considering that NG strains with DS to cefixime have an MIC to cefixime of 0.25 mg/LFootnote c. Based on these considerations, a dose of cefixime 800 mg orally every 8 hours for 3 doses may sufficiently achieve therapeutic targets for NG strains with lower MICs of less than 0.5 mg/L. Chisholm et al. (2010)Reference 41 conducted a pharmacodynamics simulation study to determine whether higher single cefixime doses or multiple doses would achieve target ƒT>MIC values of 20 to 24 hours for NG. The authors found that, for NG isolates with an MIC of 0.25 mg/L, a two-dose regimen of cefixime at 400 mg given 6 hours apart achieved the target ƒT>MIC at 26 hours, while two doses of cefixime 200 mg given 6 hours apart, and single doses of 400 mg and 200 mg did not reach the target, suggesting the potential utility of multiple dose regimens to optimize treatmentReference 41.

In 2013Reference 9, the CGSTI recommended ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus azithromycin 1 g orally in a single dose as the preferred regimen for the treatment of uncomplicated NG infection, and recommended increasing cefixime to 800 mg orally combined with azithromycin 1 g orally in a single dose as a preferred alternative for only uncomplicated anogenital infections (Canadian STI Guidelines). The rationale for this higher dose of cefixime 800 mg was based on concerns of an increasing MIC of NG to 0.125 mg/L, whereby a dose of cefixime 400 mg would not be adequate in achieving the target ƒT>MIC of 20 to 24 hours. Based on PK-PD modelling, the Expert Working Group for the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections in 2013 recommended cefixime 800 mg as a single dose to increase the ƒT>MIC to approximately 20 hours for NG isolates with a MIC of up to 0.125 mg/L.

For ceftriaxone, several organizations have updated their treatment guidelines for NG to recommend the use of higher dosesReference 14Reference 40. Based on PK-PD modelling for ceftriaxone, an increase in dose from 250 mg to 500 mg would increase the ƒT>MIC from 16 hours to 24 hours, which would achieve the target to effectively treat NG isolates with MICs of 0.25 mg/L or lowerReference 41. Thus, a higher dose of ceftriaxone would be more effective against potential strains with reduced susceptibility.

In summary, with an increase in NG isolates with reduced susceptibilities to cephalosporins, new dosing strategies based on PK-PD principles are required to maintain the effectiveness of these agents while reducing the development of resistance. A higher single dose such as 500 mg and multiple dosing regimens may have utility in optimizing the activity of cephalosporins; however, further clinical and surveillance studies are needed to verify their clinical efficacy and effects on AMR.

Evidence on patient values and preferences, feasibility, acceptability to stakeholders, equity and resource use

The available evidence on patient values and preferences for NG infection treatment is limited. WHO (2016) found no evidence on patient values and preferences, acceptability, equity or feasibility specific to gonococcal infections treatmentReference 31. Additionally, the Belgium Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE) (2019)Reference 94 cited the WHO's report, indicating the lack of available evidence in this area. For most guidelines, the emphasis has been placed on cures, rather than on side effects of treatments. There are some data in the literature on the acceptability of injections versus oral medication in people with syphilis. Approximately 10-20% of patients refused injectionsReference 31Reference 95Reference 96. Regarding adverse drug reactions, the incidence of gastrointestinal side effects is high in particular with azithromycin 2 gReference 56Reference 97. This dose may therefore not be as acceptable to patients or healthcare providers/cliniciansReference 40Reference 98. Other factors may be valued by patients, such as convenience of receiving an injection provided in a clinic rather than filling a prescription at another location, or the fear of stigma at the time of filling a prescription for an STI.

Adherence to the previously published recommendations by clinicians may be different depending on the province and availability of medications. For example, clinicians in British Columbia tend to prescribe cefixime over ceftriaxone as a first choice (personal communication with Troy Grennan, June 2023). In some primary care settings they may also not stock or have the resources to provide ceftriaxone injections. Better adherence to guidelines may also be dependent on providing treatment recommendations that are similar for genital, anorectal and pharyngeal sites, as opposed to having different recommendations according to site.

Ceftriaxone is currently available as 250 mg vials, and if the dose were to be increased to 500 mg, clinicians could either use 2 x 250 mg vials or one half of a 1000 mg vial. The two doses of 250 mg could be combined into one syringe and administered as one IM injection to the patient. It is likely that the cost differences between using 2 x 250 mg vials or half a vial of 1000 mg would be negligible.

The literature regarding cost effectiveness of NG treatment is very limited. The WHO's 2016Reference 31 NG treatment guideline included a review of the cost-effectiveness evidence and concluded that the cost compared to the effectiveness of combination therapy was not greater than that of monotherapyReference 31. Xiridou et al. (2016)Reference 99 investigated whether dual therapy could delay the spread of AMR and whether the additional costs of dual therapy be efficiently invested into the resulting health benefits of dual therapy compared with monotherapy. They used a transmission model and an economic model to determine the costs and effects of monotherapy and dual therapy among MSM. Their framework was based on testing and treatment guidelines in the Netherlands. For the baseline scenario, they assumed that dual therapy was introduced in the absence of resistance to ceftriaxone or azithromycin. They also examined a scenario with 5% azithromycin resistance in the beginning. They calculated costs and used quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) as a measure of the health benefits of the treatment strategies. Based on their assumptions and the parameters used in the models, the authors concluded that, in the absence of initial resistance, dual therapy can delay the spread of ceftriaxone resistance by at least 15 years, compared to monotherapy. However, if azithromycin resistance is initially prevalent (5%), resistance to the first-line treatment increases similarly with both treatment strategies and the annual incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ratio of annual additional costs divided by annual QALYs gained) remains extremely high (i.e., is not a cost-effective strategy).

In summary, based on the literature review and the opinions of the Gonorrhea treatment Working Group, factors valued by patients for the treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal infections may include potentially fewer side effects with monotherapy than with combination therapy, and route of administration (the oral route avoids a painful injection, but may be associated with stigma during filling a prescription for an STI, while the administration of the drug directly at the clinic may be perceived as convenient). Clinicians may adhere better to recommendations that are similar for the different infected sites. Resources and availability of medications in Canadian jurisdictions could be a strong predictor. The cost and feasibility of providing an increased dose of ceftriaxone would likely be negligible, which may lead to little impact on equity.

Justification/Rationale

There are some points to consider when interpreting the literature review findings. The timeline for the literature review search was from January 1st 2010 to February 2020 (updated in 2023). In addition, a comprehensive/systematic review of primary studies on the effects of treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea in symptomatic or asymptomatic adults and adolescents, including pregnant and non-pregnant individuals was not conducted for the interim guidance. The interim guidance/recommendations will be updated/reaffirmed pending the completion of a more comprehensive/rapid review of primary studies.

The Working Group considered evidence from published systematic reviews, recommendations from several guideline development groups, a sample of primary studies, Canadian epidemiology/surveillance information, AMR surveillance data in Canada, surveillance information on treatment failures in Canada, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cephalosporins in NG infections, and literature on patient values and preferences, feasibility, acceptability, equity and resource use.

Evidence suggests that the percentages of cures are similar with combination therapy or monotherapy, and that ceftriaxone with dosages varying from 250 to 1000 mg, and with or without azithromycin, result in similar percentages of cures. A worrying increase in azithromycin resistance (7.6%) has been observed, which is above the 5% cut-off established by WHO. In addition, 20.5% of strains harbor an azithromycin MIC of 1 mg/L, which is only one dilution below resistance threshold. Treatment failures have been reported in Canada, even when ceftriaxone is combined with azithromycin. Due to the small number of events, it is difficult to identify whether a specific regimen is more associated with failure. The use of azithromycin in combination therapy with ceftriaxone or cefixime may also be contrary to the priority set in Canada for antimicrobial stewardshipReference 18. In addition, side effects (e.g., gastrointestinal side effects) with the higher dose of azithromycin may limit its use.

A higher single dose such as 500 mg and multiple dosing regimens may have utility in optimizing the activity of cephalosporins; however, further clinical and surveillance studies are needed to verify their clinical efficacy and effects on AMR. Overall, the choice of 500 mg ceftriaxone rather than 250 mg without azithromycin could favour better responses to treatment in more individuals, but given increased resistance to ceftriaxone globally, a test of cure has become more important.

Although oral medications may be preferred over injections by patients, ceftriaxone injections could be provided immediately at a clinic, and potentially reduce stigma if an oral prescription had to be filled. Increasing the dose of ceftriaxone for all sites of infection may be acceptable and feasible to clinicians, and have little impact on costs or equity. Additional research is underway to develop alternative treatment recommendations.

Based on these judgments, NAC-STBBI has made new recommendations for the preferred treatment of NG as presented in the table below. Given that the included studies were conducted earlier, changes in the resistance to these medications over time and smaller sample size of the studies, the certainty of the evidence is low.

Updated recommendation on the preferred treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea in adults and adolescents 10 years of age and older

NAC-STBBI recommends Ceftriaxone 500 mg IM as a single dose (monotherapy) for preferred treatment of all uncomplicated infections (urethral, endocervical, vaginal, rectal and pharyngeal).

- If C. trachomatis infection has not been excluded by a negative test, concurrent treatment for chlamydia is recommended; refer to the treatment recommendations in the PHAC Chlamydia and LGV Guide: Treatment and follow-up).

Alternative treatment options for uncomplicated infections, which are required if access to IM injection is not available, if the individual refuses the injection, or if the individual is severely allergic to cephalosporins, are currently under review by the NAC-STBBI. Refer to the following four alternative treatment regimens in the PHAC Gonorrhea Guidepending further review.

- Cefixime 800 mg PO in a single dose plus doxycycline 100 mg PO BID x 7 daysFootnote *

- Cefixime 800 mg PO in a single dose plus azithromycin 1g PO in a single dose

- Azithromycin 2 g in a single oral dose PLUS gentamicin 240 mg IM in a single doseFootnote *

- Gentamicin 240 mg IM a single dose PLUS doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 daysFootnote *

Notes

- If C. trachomatis infection has not been excluded by a negative test, concurrent treatment for chlamydia is recommended; refer to the treatment recommendations in the PHAC Chlamydia and LGV Guide: Treatment and follow-up).

- Refer to PHAC Gonorrhea Guide: Treatment and follow-up for further details for each treatment regimen, including the indications for use of ertapenem and also for information on partner notification and treatment.

- Test of cure (TOC) is recommended for all positive NG sites in all cases. This is particularly important when regimens other than ceftriaxone 500 mg IM are used (refer to Table below).

- The following alternative treatment regimens have been removed from the PHAC Gonorrhea Guide.

- Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM in a single dose PLUS doxycycline 100 mg PO BID x 7 daysFootnote **

- Azithromycin 2 g in a single oral dose PLUS ciprofloxacin 500 mg in a single oral doseFootnote **

- Azithromycin 2 g in a single dose plus gemifloxacin 320 mg in a single oral doseFootnote **

Recommendation on the choice of test and timing for test of cure

NAC-STBBI recommends a TOC for all positive NG sites in all cases. This is particularly important when regimens other than ceftriaxone 500 mg IM are used.

- A NAAT should be performed three to four weeks after the completion of treatment because residual nucleic acids from dead bacteria may be responsible for positive results less than three weeks after treatment.

- When a TOC is performed within three weeks after completion of treatment, a culture should be performed; samples should be taken at least three days after completion of treatment.

- When treatment failure is suspected more than three weeks after treatment, both NAAT and culture should be performed (for example, when symptoms persist or recur after treatment).

Recommendation on NG culture

Although culture is less sensitive than NAAT, it provides the opportunity for antimicrobial susceptibility determination, which is important for case management and is critical for monitoring AMR patterns and trends. Continuing to monitor for emergence of AMR through ongoing surveillance is essential to inform timely changes in treatment recommendationsReference 100.

NAC-STBBI recommends NG culture (together with NAAT) in the following situations:

- For a TOCFootnote * when treatment failure is suspected;

- In the presence of symptoms compatible with cervicitis, urethritis, PID, epididymo-orchitis, proctitis or pharyngitis;

- Asymptomatic individual who has notified as a contact of an NG infected case;

- When sexual abuse/sexual assault is suspected (this may vary according to legal and medical contexts of the jurisdiction);

- If the infection might have been acquired in countries or areas with high rates of AMR (NG resistant strains have been reported in Canada, Japan, Europe and Australia; many were associated with travel to South-East Asia).

In addition, NAC-STBBI recommends a culture when NG infection is confirmed by NAAT only, as long as it does not delay treatment.

Note:

- Successful culture requires proper collection and transportation of appropriate specimensReference 101Reference 102. Consult with your local Public Health Laboratory for guidance on specimen collection and transportation.

Screening for reinfection

There is no change to the recommendation.

Repeat screening of people with a gonococcal infection is recommended six months post treatment, because of the risk of reinfectionReference 103.

Acknowledgements

NAC-STBBI Gonorrhea Treatment Working Group:

Co-chairs: Annie-Claude Labbé and Tim Lau

Members: Jared Bullard, Troy Grennan, Todd F. Hatchette, Irene Martin, Petra Smyczek and Mark Yudin

Other NAC-STBBI members:

Ian M. Gemmill (chair), William A. Fisher, Jennifer Gratrix, Gina Ogilvie and Marc Steben

Ex-officio representative (non-voting): Ibrahim Khan

Public Health Agency of Canada (Secretariat)

Ulrick Auguste, Shamila Shanmugasegaram, Annie Fleurant and Nick Giannakoulis

External Contributor

Nancy Santesso (McMaster University)

External Peer-reviewers

Dr. Jo-Anne Dillon

Dr. Hunter Handsfield

Dr. Ameeta Singh

Appendices

Appendix 1 : Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Surveillance Information

| Antibiotic | MIC Interpretive Standard (mg/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | DS | I | R | |

| AzithromycinFootnote a | ≤ 1.0 | - | - | ≥ 2.0 |

| CefiximeFootnote aFootnote b | ≤ 0.125 | 0.25 | - | ≥ 0.5 |

| CeftriaxoneFootnote aFootnote b | ≤ 0.06 | 0.125-0.25 | - | ≥ 0.5 |

| CiprofloxacinFootnote a | ≤ 0.06 | - | 0.12 - 0.5 | ≥ 1.0 |

| GentamicinFootnote cFootnote d | ≤ 4.0 | - | 8 - 16 | ≥ 32.0 |

| PenicillinFootnote a | ≤ 0.06 | - | 0.12- 1.0 | ≥ 2.0 |

| TetracyclineFootnote a | ≤ 0.25 | - | 0.5 - 1.0 | ≥ 2.0 |

|

Abbreviations: DS, decreased susceptibility; I, intermediate; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; R, resistant; S, susceptible. Note: According to the Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI), there is no established resistance breakpoint for azithromycin, ceftriaxone and cefixime. When the NG isolate has an MIC above the susceptibility breakpoint (1 mg/L for azithromycin and 0.25 mg/L for ceftriaxone and cefixime, it is considered "non-susceptible". For simplification, the term "resistant" has been used to describe these strains.

|

||||

a. Percentage based on total number of isolates tested nationally:

2011=3,360; 2012=3,036; 2013=3,195; 2014=3,809; 2015=4,190; 2016=4,538; 2017=5,290; 2018=5,607; 2019=4,859; 2020=3,130; 2021-3,439.

b. Not all provinces test penicillin, tetracycline and erythromycin, therefore denominators are lower for these antimicrobials.

Figure 1: Text description

This figure is a line graph displaying the percentage of all Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates determined to be penicillin-resistant, tetracycline-resistant, erythromycin-resistant, ciprofloxacin-resistant, azithromycin-resistant, cefixime-decreased susceptible and ceftriaxone-decreased susceptible based on the number of isolates tested nationally each year, from 2011 to 2021.

| Antibiotic | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillin Resistance | 22.2% | 20.3% | 18.9% | 18.2% | 18.9% | 17.4% | 19.0% | 9.2% | 7.14% | 6.97% | 6.56% |

| Tetracycline Resistance | 29.4% | 30.3% | 33% | 47.3% | 56.4% | 53.3% | 45.9% | 47.1% | 44.21% | 42.99% | 64.64% |

| Erythromycin Resistance | 26.6% | 23.1% | 24.3% | 32% | 32.4% | 31.7% | 57.0% | 56.0% | 37.70% | 32.50% | 51.45% |

| Ciprofloxacin Resistance | 29.3% | 28.5% | 29.3% | 34% | 38.9% | 47% | 50.1% | 57.3% | 56.95% | 56.45% | 49.37% |

| Azithromycin Resistance | 0.4% | 0.9% | 1.2% | 3.3% | 4.7% | 7.2% | 11.6% | 7.6% | 11.67% | 6.10% | 7.59% |

| Cefixime Decreased Susceptibility | 4.2% | 2.2% | 1.8% | 1.1% | 1.9% | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.5% | 1.46% | 2.77% | 1.51% |

| Ceftriaxone Decreased Susceptibility | 6.2% | 5.5% | 3.5% | 2.7% | 2.7% | 1.8% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.82% | 0.93% | 0.61% |

Figure 2: Text description

This figure is a line graph displaying the percentage of all Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates identified with azithromycin minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of ≥ 2 mg/L and ≥ 1 mg/L based on the total number of cultures tested nationally each year, from 2017 to 2021.

| Azithromycin MIC | 2017 (N=5,290) |

2018 (N=5,607) |

2019 (N=4,859) |

2020 (N=3,130) |

2021 (N=3,439) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azithromycin MIC ≥2mg/L | 11.6% | 7.6% | 11.67% | 6.10% | 7.59% |

| Azithromycin MIC ≥1mg/L | 22.2% | 26.5% | 18.17% | 15.27% | 28.14% |

a. Personal communication, Brigitte Lefebvre, LSPQ, August 4th, 2023.

Figure 3: Text description

This figure is a linear graph displaying the percentage of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates resistant to azithromycin and ciprofloxacin in Quebec from 2010 to 2021.

| Antibiotic | 2010 n=920 |

2011 n=797 |

2012 n=772 |

2013 n=714 |

2014 n=906 |

2015 n=1031 |

2016 n=1260 |

2017 n=1478 |

2018 n=1836 |

2019 n=1747 |

2020 n=1167 |

2021 n=1520 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aztrhromycine | 1.2% | 1.0% | 1.7% | 1.7% | 6.7% | 12.4% | 19.9% | 30.9% | 27.6% | 27.6% | 23.7% | 39.0% |

| Ciprofloxacine | 32.2% | 35.3% | 47.5% | 38.7% | 36.6% | 46.3% | 59.5% | 67.3% | 73.6% | 74.2% | 73.0% | 50.4% |

|

n: number of strains tested |

||||||||||||

Appendix 2: List of guidelines

Guidelines on treatment of gonorrhea

| Group, Country & Year | Population | Intervention | Outcome(s) | Recommendations (urogenital- anorectal infections) |

Recommendations (pharyngeal infection) |

Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

World Health Organization (WHO, 2016) |

Adults and adolescents (10-19 years of age), people living with HIV, and key populations, including sex workers, MSM and transgender person including pregnant women. |

Drug Therapy: |

Clinical and microbiological cure and adverse effects |

Preferred Evidence level: Low quality evidence, conditional recommendation |

Preferred |

|

Monotherapy

Evidence level: Low quality evidence, conditional recommendation |

Monotherapy

Evidence level: Low quality evidence, conditional recommendation |

|||||

Treatment failure:

Note: Higher dose of ceftriaxone, cefixime, azithromycin in cases of treatment failure |

||||||

Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine (ASHM) 2021 |

Adults |

Drug Therapy: |

Not specifically stated In general:

|

Preferred |

Preferred |

No systematic review identified; Expert panel from CDNA -consensus-based approach drawing from existing STI guidelines, research data, gonococcal surveillance data and practice data. |

Alternatives |

Alternatives |

|||||

Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany AWMF Germany 2019Table Footnote * |

Adults |

Drug Therapy: |

Not specifically stated In general:

|

Three options based on the following conditions: a. Site of infection and availability of identification of the pathogen b. Patient compliance in terms of treatment monitoring 1-Ceftriaxone 1-2 g IM or IV Plus Azithromycin 1.5 g PO if pathogen identification not yet available and patient compliance unknown/not definitively ensured. 2-Ceftriaxone 1-2 g IM or IV if pathogen identification not yet available and Patient compliance certain (additional diagnosis workup and follow-up in 4 weeks. 3-Ceftriaxone (monotherapy)1-2 g IM or IV if pathogen has been identified and patient compliance is certain and co-infection ruled-out. Note: For option 2 and 3 follow-up is required, 4 weeks after treatment for monitoring of treatment success using NAATs. |

Same as for anogenital infections Cefixime is insufficiently effective in case of pharyngeal infection. In such cases, treatment with ceftriaxone is required. |

Unspecified. |

N. gonorrhoeae has been identified, and results of susceptibility testing are available Follow-up 4 weeks after treatment for monitoring of treatment response |

Same as for anogenital infections Note: Cefixime is not recommended for treatment of pharyngeal NG infection. |

|||||

BASHH (2018) |

Adults |

Drug Therapy: |

Not specifically stated In general:

|

Ceftriaxone 1 g - when antimicrobial susceptibility is not known prior to treatment (Grade IC) When antimicrobial susceptibility is known: Ciprofloxacin 500 mg PO |

Literature search: Studies and surveillance reports (UK and international) |

|

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment guidelines (2021) |

Infants, Children, Adolescents and adults |

Drug Therapy: |

Not specifically stated In general:

|

Preferred: Note: If chlamydial infection has not been excluded, concurrent treatment with doxycycline (100 mg orally twice a day for 7 days) is recommended. |

Preferred: Note: If Chlamydial infection is identified, treat for chlamydia with doxycycline |

Subject matter experts (SMEs) conducted a literature search of PubMed, Embase, and Medline databases by using parameters related to gonorrhea treatment. Review of published literature and US national AMR surveillance data, by CDC staff members and SMEs. |

Alternatives:

|

Alternatives: |

|||||

European International Union against Sexually Transmitted Infections (IUSTI) 2020) |

Adults and adolescents |

Drug Therapy: |

Not specifically stated In general :

Prevention of complications |

Preferred:

Note: For uncomplicated N. gonorrhoeae infections of the urethra, cervix and rectum in adults and adolescents when the antimicrobial sensitivity of the infection is unknown |

Preferred:

|

Medline search using PubMed for relevant for relevant articles published since the development of the previous 2012 guideline. |

Alternatives:

When the infection has been confirmed before treatment to be susceptible to Ciprofloxacin

Note: Treatment for coinfection with Chlamydia should be considered unless coinfection has been excluded with NAAT testing. |

Alternatives:

Note: If azithromycin is not available or patient unable to take oral medication

Note: When the infection has been confirmed before treatment to be susceptible to Ciprofloxacin |

|||||

Société Française de Dermatologie (SFD) et de pathologie sexuellement transmissible, 2016 |

Adults (Men and women) |

Drug Therapy: |

Not specifically stated In general:

|

Ceftriaxone 500 mg IM Chlamydia treatment should always be combined. |

Ceftriaxone 500 mg IM Chlamydia treatment should always be combined. |

Unspecified |

Belgian Healthcare Knowledge Centre (KCE) 2019 |

Women and men including young people |

Drug Therapy: |

Not specifically stated In general:

|

Combination therapy

|

Combination therapy

|

This guideline was developed following an evidence-based approach and involving a guideline development group (GDG). A literature review was conducted, including a search for existing guidelines and the grey literature. The ADAPTE method was used to assess the quality of available guidelines It was also performed a search of systematic reviews and primary studies of gonorrhea treatment. The evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach. |

Pregnant women |

Monotherapy |

As above |

Monotherapy

|

Monotherapy

|

||

New Zealand Sexual Health Society (NZSHS, 2017) |

Adults Note: Adults and children in 2014 guidelines |

Drug Therapy: |

Not specifically stated In general:

|

Ceftriaxone 500 mg plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

Ceftriaxone 500 mg plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

Refers to the 2014 guidelines in which the NZSHS conducted a review of international NG management guidelines and studies conducted in NZ. Consensus, following group discussion. |

Note: If co-infection with rectal chlamydia, treatment as above PLUS doxycycline 100mg PO twice daily for 7 days. |

||||||

|

||||||

Existing Guidelines on treatment of gonorrhea

| Group, Province/Territory & Year | Population | Intervention | Outcome(s) | Recommendations (anogenital infection) |

Recommendations (pharyngeal infection) |

Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Alberta Health Services Alberta Treatment Guidelines for STI 2018 |

Adults and adolescents |

Drug Therapy: |

Cefixime 800 mg Note: Ceftriaxone is recommended for gbMSM,. |

Ceftriaxone 250 mg |

Adaptation from the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections. |

|

BCCDC British Columbia Treatment Guidelines for STI 2014 |

Adults and adolescents |

Drug Therapy: |