Report on the enhanced surveillance of antimicrobial-resistant gonorrhea (ESAG) - Results from 2014 and 2015

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 861 KB, 45 pages)

Organization:

Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: 2019-04-29

TO PROMOTE AND PROTECT THE HEALTH OF CANADIANS THROUGH LEADERSHIP, PARTNERSHIP, INNOVATION AND ACTION IN PUBLIC HEALTH.

—Public Health Agency of Canada

Également disponible en français sous le titre :

Rapport sur le Système de surveillance accrue de la résistance de la gonorrhée aux antimicrobiens (SARGA) :

Résultats de 2014 et 2015

To obtain additional copies, please contact:

Public Health Agency of Canada

Address Locator 0900C2

Ottawa, ON K1A 0K9

Tel.: 613-957-2991

Toll free: 1-866-225-0709

Fax: 613-941-5366

TTY: 1-800-465-7735

E-mail: publications@hc-sc.gc.ca

This publication can be made available in alternative formats upon request.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Health, 2019

Publication date: April 2019

This publication may be reproduced for personal or internal use only without permission provided the source is fully acknowledged.

Suggested Citation: Public Health Agency of Canada. Report on the Enhanced Surveillance of Antimicrobial-resistant Gonorrhea: Results from 2014 and 2015. Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control, Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada; 2018.

Cat.: HP40-206-1-2019E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-30288-1

Pub.: 180943

Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Key Messages

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Methods

- 3.0 Results

- 4.0 Discussion

- References

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Appendix C

- Appendix D

Acknowledgements

The development and continuation of the Enhanced Surveillance of Antimicrobial-Resistant Gonorrhea (ESAG) project and the publication of this report would not have been possible without the collaboration of Alberta Health Services; Alberta Provincial Laboratory for Public Health; Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living; Cadham Provincial Laboratory; the Nova Scotia Health Authority (Central Zone); and the Provincial Public Health Laboratory Network of Nova Scotia. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the contributions of sentinel sites in those jurisdictions.

This report was prepared by the Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control and the National Microbiology Laboratory, Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC).

Key Messages

- Currently, Neisseria gonorrhoeae (N. gonorrhoeae), the bacteria that causes gonorrhoea, is considered a serious public health threat since it has increasingly developed resistance to antimicrobial drugs previously and currently recommended to treat it.

- The Public Health Agency of Canada launched the Enhanced Surveillance of Antimicrobial-Resistant Gonorrhea (ESAG) initiative to better understand the current trends of antimicrobial resistant N. gonorrhoeae, and to support the development of treatment guidelines and public health interventions to minimize the spread of antimicrobial resistant gonorrhea in Canada.

- In 2014 and 2015, data were collected from sentinel sites in four cities: Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, and Halifax. Sentinel sites were selected by provincial and local health authorities and were sexual health or sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics or healthcare providers with the capacity to collect cultures for testing, and to provide enhanced epidemiological and clinical data. These clinics collected cultures for testing, according to their provincial guidelines.

- In 2014, ESAG collected 534 cultures from 458 cases. In 2015, 786 cultures were obtained from 660 cases. An almost equal proportion of ESAG cases in 2014 (17%; 76/458) and 2015 (16%; 106/660) had multiple isolates from different infection sites.

- The majority of cases in both years were male (84.5% in 2014 and 81.7% in 2015) and less than 40 years old (85.6% in 2014 and 83.8% in 2015). The majority of the cases (60.3%) were among men who have sex with men (gbMSMFootnote a) in 2014, while slightly less than half of cases (47.7%) were reported as gbMSM in 2015. Almost all female cases in both years reported male sexual partners.

- Overall, a slightly higher proportion of isolates with resistance to one or more antimicrobials was reported in 2015 (60.0%) than in 2014 (55.2%).

- Decreased susceptibility to cefixime declined overall from 3.5% in 2014 to 0.8% in 2015. Decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone remained consistent between 2014 (1.5%) and 2015 (1.8%); however, among isolates from gbMSM, this proportion increased from 1.1% in 2014 to 2.9% in 2015. The overall proportion of resistance to azithromycin decreased from 1.5% in 2014 to 0.5% in 2015.

- Among gbMSM, the national preferred therapy of ceftriaxone and azithromycin was consistently prescribed more frequently to treat pharyngeal infections than to treat anogenital infections in 2014 (95.6% versus 81.6%) and 2015 (90.8% versus 87.2%). Among non-gbMSM adults, the two preferred combination therapies were almost equally prescribed (44% for ceftriaxone and azithromycin; 42.7% for cefixime and azithromycin) for anogenital infections in 2014, whereas in 2015, a shift was noted from the use of ceftriaxone and azithromycin (9.1%) to cefixime and azithromycin (81.9%).

- With regards to molecular typing, ST7638 (20.9%) was the most prevalent sequence type (ST) in 2015, while ST5985 (12.6%) was the most prevalent ST in 2014. ST7638 is the primary ST identified among non-gbMSM and females, and isolates in this group are susceptible or have low-level resistance to tetracycline. ST5985 the primary ST identified among gbMSM and these isolates are high-level, plasmid mediated tetracycline resistant N. gonorrhoeae (TRNG).

- Gonococcal isolates with decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins were identified in high-risk and frequently transmitting populations such as gbMSM. As ceftriaxone and cefixime (in combination with azithromycin) are the recommended options for gonorrhea treatment, the emergence of resistance to these antimicrobials could initiate an era of gonorrhea that would be untreatable using any of these antimicrobials as combined therapy. It is critical to intensify AMR surveillance and expand ESAG geographical coverage for identification and monitoring across Canada of further spread of resistance to these antimicrobials.

1.0 Introduction

Rates of sexually transmitted infections (STI) continue to increase globally, including in Canada. Gonorrhea is the most commonly reported drug resistant STI and the second most common bacterial STI in Canada with over 19,000 cases reported in 2015Footnote 1. The causative organism, Neisseria gonorrhoeae (N. gonorrhoeae), has long been known to possess the ability to acquire antimicrobial resistance (AMR) through various evolutionary adaptationsFootnote 2. In 2012, laboratory observed increases in decreased susceptibility to the class of antibiotic drugs known as cephalosporins prompted new recommendations for treatment of gonorrhea in the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections. Since then, the recommended first-line treatment for uncomplicated anogenital gonorrhea in gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM) and pharyngeal gonorrhea in all adults has been combination therapy with 250 mg ceftriaxone injected intramuscularly and 1 g azithromycin ingested orallyFootnote 3. In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) predicted that drug resistance in N. gonorrhoeae could result in it emerging as a “superbug”Footnote 4 and that gonorrhea could become untreatable due to resistance to all classes of antimicrobialsFootnote 5. Additionally, in 2013, the Director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) described gonorrhea as one of the three most critical public health threats in the United StatesFootnote 6. Dual therapy treatment failures have also been reported in CanadaFootnote 7. The management of antimicrobial resistance has been identified as a priority in the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC)’s 2017-2018 Report on Plans and PrioritiesFootnote 8, Corporate Risk Profile, PHAC’s Operating Plan, as well as in the Standing Committee of Health (HESA) Study on the Status of Antimicrobial Resistance in Canada and Related RecommendationsFootnote 9. It has also been highlighted in the Agency’s Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (CARSS)Footnote 10 reporting as well as in its Pan-Canadian Framework for Action: Reducing the Health Impact of Sexually Transmitted and Blood-borne Infections in Canada by 2030Footnote 11.

Antimicrobial resistance testing is an important component of gonococcal (GC) surveillance as it: 1) allows for the identification and characterization of resistant isolates in circulation, and 2) monitors changes in the proportion of isolates that are resistant, which is vital for informing clinical treatment guidelines. Currently, the regional laboratories in all ten provinces employ culture for a proportion of the total gonorrhea tests done in their jurisdictions, but nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) is the recommended testing method for diagnosis in some of these jurisdictions. The use of culture for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) testing is a standard laboratory practice for all positive gonorrhea isolates detected by culturing worldwide, including Canada. However, as the majority of GC cases (70%) are not cultured, AMR data are not available for these casesFootnote 12. Most jurisdictions with provincial laboratories that perform culture also perform AMR testing on all positive cultures. Resistant isolates, as well as all isolates from jurisdictions that do not conduct AMR testing, are sent from provincial laboratories to the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) for a standard panel of AMR testing. However, the jurisdictions determine which isolates are submitted to NML and the selection criteria are not consistent, resulting in lack of representativeness. The NML also performs N. gonorrhoeae multi-antigen sequence typing (NG-MAST) as a means to describe the circulating strains of gonorrhea across Canada. The only epidemiological data collected on these isolates are sex, age of patient, province and anatomic site of isolation.

Gonorrhea has been a nationally notifiable disease since 1924 in Canada; however, the amount and quality of information collected and reported to PHAC through routine surveillance are limited. Comprehensive national epidemiological data for antimicrobial resistant gonorrhea isolates are currently not available; limiting the ability to assess risk factors associated with AMR and guide treatment recommendations at a national level. There are also significant difficulties in deriving a valid denominator to estimate the prevalence and patterns of AMR in Canada. The establishment of a pan-Canadian, standardized approach to the surveillance of antimicrobial-resistant gonococcus, combining both epidemiologic and laboratory data, would provide better representation across the country and greater confidence in the estimation of the proportion of drug-resistant isolates. Coupled with NG-MAST sequence typing and enhancement in data quality, this approach would also provide an opportunity to detect unusual clusters, facilitate more timely outbreak response, and design evidence-informed treatment guidelines.

In 2013, the Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control (CCDIC), in partnership with the NML and three provinces (Alberta, Manitoba and Nova Scotia), launched the pilot phase of the Enhanced Surveillance of Antimicrobial-Resistant Gonorrhea (ESAG). Alberta, which already collected data relevant to N. gonorrhoeae antimicrobial resistance (GC-AMR), was the first participating jurisdiction. Winnipeg and the Capital District Health Authority in Nova Scotia (now the Nova Scotia Health Authority Central Zone), began collecting data in 2014. Other jurisdictions have expressed interest in participating in ESAG and recognize that ESAG could be incorporated into their existing surveillance activities.

1.1 Project Goal

The overall goal of this integrated epidemiology-laboratory surveillance system is to improve the understanding of current levels and trends of antimicrobial resistant gonorrhea in Canada and to provide better evidence to inform the development of treatment guidelines and public health interventions to minimize the spread of antimicrobial resistant N. gonorrhoeae.

1.2 Project Deliverables

The objectives of this surveillance system are to:

- Increase the number of gonococcal cultures performed at participating sentinel sites in order to improve monitoring of gonorrhea AMR;

- Monitor antimicrobial susceptibilities of N. gonorrhoeae among newly diagnosed culture-confirmed gonorrhea cases and cases of potential treatment failureFootnote b;

- Collect additional epidemiological data (demographics and risk factors) on people who provided samples for a gonococcal culture, including newly diagnosed, culture-confirmed, gonorrhea cases and cases of treatment failure, to determine the risk factors for gonorrhea AMR in these populations;

- Collect data on the drugs prescribed to treat gonorrhea;

- Identify the sequence types of circulating antimicrobial resistant N. gonorrhoeae through NG-MAST typing.

2.0 Methods

2.1 Case Definitions

The national case definition for gonorrhea was used and consists of laboratory evidence of detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae by culture or by nucleic acid testingFootnote 13.

An “ESAG case” refers to a patient 16 years of age and older from whom a specimen (or specimens) collected within thirty days met the national case definition of gonorrhea. All positive cultures from participating sentinel sites were included in ESAG.

The case definition for treatment failure used in ESAG was the absence of sexual contact during the post-treatment period AND one of the following: 1) gram-negative intracellular diplococci at least 72 hours post treatmentFootnote 4; 2) positive N. gonorrhoeae culture at least 72 hours post treatment; or 3) positive N. gonorrhoeae NAAT at least 2-3 weeks post treatmentFootnote 3.

2.2 Data Collection

Data were collected from sentinel sites in four jurisdictions: Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg and Halifax. Sentinel sites were selected by participating provincial/local health authorities and were sexual health or STI clinics or healthcare providers with the capacity to collect cultures for testing and to provide enhanced epidemiological and clinical data. Cultures were collected by sentinel sites according to their provincial guidelines on gonorrhea testing. Where possible, the number of gonococcal cultures performed was increased in order to improve monitoring of antimicrobial-resistant gonorrhea.

Data were extracted from routine/enhanced case report forms of ESAG-eligible gonorrhea cases reported to public health officials by participating sentinel sites. The data elements collected as part of epidemiological information included information on demographics (e.g. age, sex, site of infection, and province), sexual partner(s) characteristics, risk behaviours, reasons for visit, and treatment. These data were later linked to laboratory testing data from the NML, such as antimicrobial susceptibility and sequence typing data, described further below.

Sentinel sites submitted isolates to provincial public health laboratories for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, which were then forwarded on to the NML where sequence typing and susceptibility testing, on an expanded panel of antimicrobials, were performed. For jurisdictions that rely on NML for their susceptibility testing, all isolates from the sentinel sites were sent to the NML for testing. Data for isolates that met the eligibility criteria were submitted to ESAG. Epidemiological data were also submitted for all susceptible isolates; however, only about half of the susceptible isolates were sent to the NML for re-testing.

Both epidemiological and laboratory data were entered or uploaded into a password-protected, web-accessible, jurisdictionally-filtered database hosted on the Canadian Network for Public Health Intelligence (CNPHI) platform. Necessary steps were taken to ensure accurate linkage of epidemiological data, entered by the sentinel sites, to laboratory results, entered by NML, in this database. A designated ID number in lieu of the patient’s name was used to link the data.

2.3 Laboratory Methods

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing for Isolates

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), the minimum concentration of antibiotic that will inhibit the growth of the organism, was determined for ceftriaxone, cefixime, azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, penicillin, tetracycline and spectinomycin on all N. gonorrhoeae isolates using agar dilution or, for the Alberta susceptible isolates not sent to the NML, Etest® (BioMerieux, Laval, Quebec). Interpretations were based on the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) breakpointsFootnote 14 except for: cefixime decreased susceptibility MIC≥0.25 mg/LFootnote 4; ceftriaxone decreased susceptibility MIC≥0.125 mg/LFootnote 4; azithromycin resistance MIC≥2.0 mg/LFootnote 15; and erythromycin resistance MIC≥2.0 mg/LFootnote 16 (refer to Appendices A and B for details).

Sequence typing for isolates

Sequence typing was determined for all cultures submitted to the NML using the N. gonorrhoeae multi-antigen sequence type (NG-MAST) methodFootnote 17 that incorporates the amplification of the porin gene (por) and the transferrin-binding protein gene (tbpB). DNA sequences of both strands were edited, assembled and compared using DNAStar, Inc. software (Madison, Wisconsin USA, https://www.dnastar.com). The resulting sequences were submitted to the NG-MAST website (http://www.ng-mast.net/) to determine the sequence types (ST). Concatenated NG-MAST porB and tbpB sequences were aligned using ClustalWFootnote 18 and a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was generated using MEGA 6.06 (http://www.megasoftware.net) based on the Tamura-Nei modelFootnote 19. NG-MAST testing was not performed on the susceptible isolates whose cultures were not submitted to the NML.

2.4 Data Analysis

Although ESAG was initiated in 2013, this report is limited to 2014 and 2015 data when all four sites were active participants. Frequencies were calculated for cases with positive cultures. Negative cultures (such as those from a follow-up visit or test-of-cure) were excluded.

For most analyses, only one culture per case was included. When more than one culture per case was submitted, the culture retained for analysis was based on a hierarchy of site of infection: the pharyngeal isolate was prioritized, followed by rectal, urethral, and cervical samples in that order. This hierarchy was determined through consensus with ESAG sites and stakeholders. However, all cultures were retained for analysis when describing the sites of infection overall.

To improve data quality, a derived sexual behaviour variable was created to supplement the self-reported ‘sex of sexual partner’. In addition to including males who self-reported sexual partners as male or both male and female, the derived “gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM)” variable includes males who did not provide information on the sex(es) of their sexual partner(s), but had a rectal infection. “Non-gbMSM” was defined as males who either only reported female partners or males who did not report any male sexual partners and did not have a rectal infection. “Male Unknown” refers to males who did not provide sexual partner information, who also did not have a rectal infection. Female and transgender cases were grouped together for antimicrobial susceptibility analysis due to there being only one transgender case, which had a vaginal site of infection. In the treatment section, cases are categorized as gbMSM (using the same derived gbMSM definition) and as Other Adults, which matches the categories used in the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted InfectionsFootnote 3 (Other Adults includes non-gbMSM males and females, but excludes males with unknown sexual behaviour).

Table 1 shows how the ESAG data were categorized to arrive at total number of cultures (including multiple isolates per case), and the total number of cases.

| Jurisdiction | Primary Culture | Duplicate Cultures | All Cultures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| Alberta | 420 | 638 | 75 | 124 | 495 | 762 |

| Manitoba | 25 | 12 | 0 | 2 | 25 | 14 |

| Nova Scotia | 13 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 10 |

| Total | 458 | 660 | 76 | 126 | 534 | 786 |

3.0 Results

3.1 Case Characteristics

There was a large decrease in the proportion of gbMSM males to non-gbMSM males, with a ratio of 2.7:1 in 2014 falling to 1.4:1 in 2015 (Table 2).

| Sex or Sexual Behaviour |

Alberta | Manitoba | Nova Scotia | Overall | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| gbMSM | 254 | 60.5 | 305 | 47.8 | 12 | 48.0 | 5 | 41.7 | 10 | 76.9 | 5 | 50.0 | 276 | 60.3 | 315 | 47.7 |

| Non-gbMSM Male | 101 | 24.0 | 216 | 33.9 | 3 | 12.0 | 5 | 41.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 104 | 22.7 | 221 | 33.5 |

| Female | 63 | 15.0 | 116 | 18.2 | 6 | 24.0 | 1 | 8.3 | 2 | 15.4 | 4 | 40.0 | 71 | 15.5 | 121 | 18.3 |

| Male - Unknown | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.2 | 4 | 16.0 | 1 | 8.3 | 1 | 7.7 | 1 | 10.0 | 7 | 1.5 | 3 | 0.5 |

| Total | 420 | 100 | 638 | 100 | 25 | 100 | 12 | 100 | 13 | 100 | 10 | 100 | 458 | 100 | 660 | 100 |

In 2015, ESAG captured 786 cultures from 660 cases. Sixteen percent (n=126) of these cases had multiple (two or three) positive isolates from different sites of infection. The age distribution was very similar in both years. In both 2014 and 2015, the majority of cases were less than 40 years old (85.6% and 83.8%, respectively) and the mean age was 31.8 years and 30.6 years, respectively.

Aside from the substantial decrease in the proportion of male cases that were gbMSM, risk behaviours for ESAG cases in 2015 remained similar to 2014, with 2.6% reporting sex work in the last 60 days and 0.6% indicating that it was likely that they acquired the infection while traveling out of province (Table 3).

| Case characteristics | 2014 | 2015 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | n | % | n | % |

| 16-19 | 40 | 8.7 | 47 | 7.1 |

| 20-29 | 215 | 46.9 | 329 | 49.8 |

| 30-39 | 137 | 29.9 | 177 | 26.8 |

| 40-49 | 38 | 8.3 | 64 | 9.7 |

| 50-59 | 24 | 5.2 | 30 | 4.5 |

| 60+ | 4 | 0.9 | 13 | 2.0 |

| Total | 458 | 100 | 660 | 100 |

| Sex Work | ||||

| Yes | 12 | 2.6 | 17 | 2.6 |

| No | 443 | 96.7 | 642 | 97.3 |

| Refused to answer | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Total | 458 | 100 | 660 | 100 |

| Travel-Related Infection | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 0.7 | 4 | 0.6 |

| No | 32 | 7.0 | 655 | 99.2 |

| Refused to answer | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Unknown | 422 | 92.1 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Total | 458 | 100 | 660 | 100 |

3.2 Reason for Visit

Among gbMSM, the primary reason for the initial clinic visit was signs/symptoms in both years. However, this fell from 45.7% to 39.3%, from 2014 to 2015, corresponding to an increase in visits due to case contact (17.4% to 29.1%, respectively). gbMSM were the group with the highest level of STI screening, accounting for approximately one fifth of visits in both years. Non-gbMSM males, on the other hand, rarely identified screening as the reason for seeking care; signs/symptoms remained the primary reason for non-gbMSM male visits in both years, accounting for about 80% of cases. The primary reason for visits among females was case contact in both years. In 2015, females had an increase in visits due to signs/symptoms (26.8% to 35.0%) and case contact (31.0% to 41.0%), with corresponding decreases in the "unknown" and "other" categories (Table 4).

| Reason for initial visit | 2014 | 2015 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gbMSM Male | n | % | n | % |

| Signs/Symptoms | 126 | 45.7 | 123 | 39.3 |

| Case Contact | 48 | 17.4 | 91 | 29.1 |

| STI Screening | 52 | 18.8 | 73 | 23.3 |

| Unknown | 19 | 6.9 | 13 | 4.2 |

| OtherFootnote * | 31 | 11.2 | 13 | 4.2 |

| Total | 276 | 100 | 313 | 100 |

| Non-gbMSM Male | ||||

| Signs/Symptoms | 82 | 78.8 | 173 | 78.3 |

| Case Contact | 13 | 12.5 | 13 | 5.9 |

| STI Screening | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 2.3 |

| Unknown | 3 | 2.9 | 5 | 2.3 |

| OtherFootnote * | 6 | 5.8 | 25 | 11.3 |

| Total | 104 | 100 | 221 | 100 |

| Female | ||||

| Signs/Symptoms | 19 | 26.8 | 41 | 35.0 |

| Case Contact | 22 | 31.0 | 48 | 41.0 |

| STI Screening | 12 | 16.9 | 16 | 13.7 |

| Unknown | 8 | 11.3 | 2 | 1.7 |

| OtherFootnote * | 10 | 14.1 | 10 | 8.5 |

| Total | 71 | 100 | 117 | 100 |

| OverallFootnote ** | ||||

| Signs/Symptoms | 229 | 50.0 | 338 | 51.7 |

| Case Contact | 83 | 18.1 | 153 | 23.4 |

| STI Screening | 64 | 14.0 | 94 | 14.4 |

| Unknown | 35 | 7.6 | 21 | 3.2 |

| OtherFootnote * | 47 | 10.3 | 48 | 7.3 |

| Grand TotalFootnote *** | 458 | 100 | 654 | 100 |

|

||||

3.3 Sites of Infection

In 2015, there were 786 isolates from 660 cases of culture-confirmed gonorrhea. Anatomic sites sampled were based on provincial screening guidelines or exposure. Isolates from female cases were primarily genital (46.4%), although this decreased from 55.8% in 2014. The proportion of rectal and pharyngeal infections both increased in females. Infections from non-gbMSM males were almost exclusively genital, while those from gbMSM males were fairly equally distributed among the rectum (37.0%), genitalia (32.7%), and pharynx (30.4%) (Table 5).

| Reason for initial visit | 2014 | 2015 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gbMSM Male | n | % | n | % |

| Rectum | 124 | 37.8 | 145 | 37.0 |

| Pharynx | 92 | 28.0 | 119 | 30.4 |

| Genital | 112 | 34.1 | 128 | 32.7 |

| Total | 328 | 100 | 392 | 100 |

| Non-gbMSM Male | n | % | n | % |

| Pharynx | 2 | 1.9 | 3 | 1.3 |

| Genital | 102 | 98.1 | 220 | 98.7 |

| Total | 104 | 100 | 223 | 100 |

| Female | n | % | n | % |

| Rectum | 18 | 18.9 | 38 | 22.6 |

| Pharynx | 24 | 25.3 | 52 | 31.0 |

| Genital | 53 | 55.8 | 78 | 46.4 |

| Total | 95 | 100 | 168 | 100 |

| OverallNote de bas de page ** | n | % | n | % |

| Rectum | 142 | 26.6 | 183 | 23.3 |

| Pharynx | 120 | 22.5 | 176 | 22.4 |

| Genital | 272 | 50.9 | 427 | 54.3 |

| Grand Total | 534 | 100 | 786 | 100 |

|

||||

3.4 Antimicrobial Susceptibility

Overall, 44.8% (205/458) of the 2014 isolates and 40.0% (264/660) in 2015 isolates were susceptible to all antimicrobials. The proportion of 2014 and 2015 isolates that demonstrated decreased susceptibility or resistance to only one antimicrobial was 20.7% (95/458) and 24.4% (161/660) respectively. The proportion of 2014 and 2015 isolates that demonstrated decreased susceptibility or resistance to two or more antimicrobials was 34.5% (158/458) and 35.6% (235/660) respectively. In 2015, the proportion of isolates demonstrating decreased susceptibility or resistance to two or more antimicrobials varied from 35.1% to 60.0% across the participating jurisdictions (Table 6).

CefiximeFootnote c

| Susceptibility | Alberta | Manitoba | Nova Scotia | Overall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 n (%) |

2015 n (%) |

2014 n (%) |

2015 n (%) |

2014 n (%) |

2015 n (%) |

2014 n (%) |

2015 n (%) |

|

| Susceptible to all | 192 (45.7) | 258 (40.4) | 8 (32.0) | 4 (33.3) | 3 (23.1) | 2 (20.0) | 205 (44.8) | 264 (40.0) |

| R/DSFootnote * to 1 | 89 (21.2) | 156 (24.5) | 3 (12.0) | 3 (25.0) | 3 (23.1) | 2 (20.0) | 95 (20.7) | 161 (24.4) |

| R/DS to 2 or more | 139 (33.1) | 224 (35.1) | 14 (56.0) | 5 (41.7) | 7 (53.8) | 6 (60.0) | 158 (34.5) | 235 (35.6) |

| Total | 420 (100) | 638 (100) | 25 (100) | 12 (100) | 13 (100) | 10 (100) | 458 (100) | 660 (100) |

|

||||||||

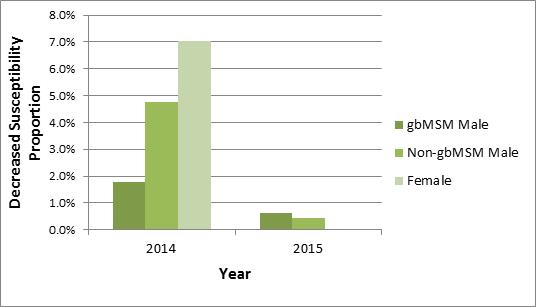

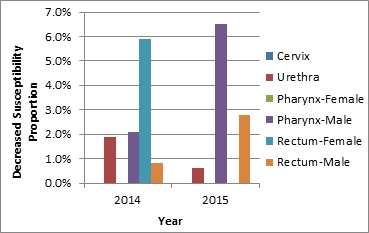

Overall, 3.5% (16/458) of isolates had decreased susceptibility to cefixime (MIC≥0.25 mg/L) in 2014, declining to 0.8% (5/660) in 2015 (Appendix C). In 2014, 4.8% (5/104) of isolates from non-gbMSM males and 7.0% (5/71) of isolates from females had decreased susceptibility to cefixime which dropped to 0.5% (1/221) and 0% (0/121), respectively, in 2015 (Appendix C and Figures 1a and 1b). Decreased susceptibility in gbMSM males also dropped from 1.8% (5/276) in 2014 to 0.6% (2/315) in 2015, as shown in Table 7.

Figure 1a. Distribution of decreased susceptibility to cefixime by sex or sexual behaviour, ESAG 2014 and 2015

Distribution of decreased susceptibility to cefixime by sex or sexual behaviour, ESAG 2014 and 2015 - Long description

The bar chart presents the percentage of ESAG isolates with decreased susceptibility to cefixime by sex or sexual behaviour groupings. The horizontal axis represents the year while the vertical axis represents the decreased susceptibility proportion.

| Sex or Sexual Behaviour | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|

| gbMSM males | 1.8 | 0.6 |

| Non-gbMSM males | 4.8 | 0.5 |

| Females | 7.0 | 0.0 |

Figure 1b. Distribution of decreased susceptibility to cefixime by sex and infection site, ESAG 2014-2015

Footnote a 2014 denominators: cervix=53; urethra=214; pharynx-female=24; pharynx-male=126; rectum-female=18; rectum-male=124

2015 denominators: cervix=78; urethra=348; pharynx-female=52; pharynx-male=148; rectum-female=38; rectum-male=145

Distribution of decreased susceptibility to cefixime by sex and infection sites ESAG 2014 and 2015 - Long description

The bar chart presents the percentage of ESAG isolates with decreased susceptibility to cefixime by sex and infection site groupings. The horizontal axis represents the year while the vertical axis represents the decreased susceptibility proportion.

| Sex or Sexual Behaviour and Infection Site | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|

| Cervix | 5.9 | 0.0 |

| Urethra | 3.2 | 0.6 |

| Pharynx – Females | 8.3 | 0.0 |

| Pharynx – Males | 3.1 | 3.2 |

| Rectum – Females | 5.9 | 0.0 |

| Rectum – Males | 1.6 | 0.0 |

CeftriaxoneFootnote d

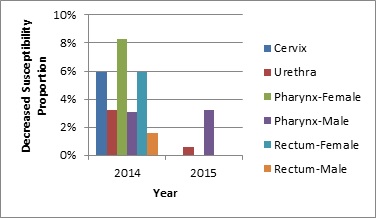

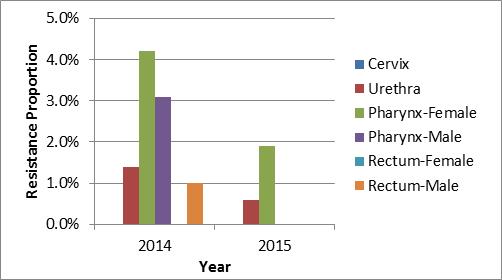

Overall, 1.5% (7/458) of ESAG isolates had decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone in 2014; this proportion increased slightly to 1.8% (12/660) in. The occurrence of decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone in isolates obtained from gbMSM males increased from 1.1% (3/276) in 2014 to 2.9% (9/315) in 2015, whereas it decreased in isolates from non-gbMSM males (1.9% to 0.5%) and females (1.4% to 0%) over the same time period (Appendix C and Figures 2a and 2b), as shown in Table 7.

Figure 2a. Distribution of decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone by sex or sexual behaviour, ESAG 2014 and 2015

Distribution of decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone by sex or sexual behaviour, ESAG 2014 and 2015 - Long description

The bar chart presents the percentage of ESAG isolates with decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone by sex or sexual behaviour groupings. The horizontal axis represents the year while the vertical axis represents the decreased susceptibility proportion.

| Sex or Sexual Behaviour | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|

| gbMSM males | 1.1 | 2.9 |

| Non-gbMSM males | 1.9 | 0.5 |

| Females | 1.4 | 0.0 |

Figure 2b. Distribution of decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone by sex and infection site, ESAG 2014 and 2015

Footnote a 2014 denominators: cervix=53; urethra=214; pharynx-female=24; pharynx-male=126; rectum-female=18; rectum-male=124

2015 denominators: cervix=78; urethra=348; pharynx-female=52; pharynx-male=148; rectum-female=38; rectum-male=145

Distribution of decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone by sex and infection site, ESAG 2014 and 2015 - Long description

The bar chart presents the percentage of ESAG isolates with decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone by sex and infection site groupings. The horizontal axis represents the year while the vertical axis represents the decreased susceptibility proportion.

| Sex or Sexual Behaviour and Infection Site | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|

| Cervix | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Urethra | 1.9 | 0.6 |

| Pharynx – Females | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Pharynx – Males | 2.1 | 6.5 |

| Rectum – Females | 5.9 | 0.0 |

| Rectum – Males | 0.8 | 2.8 |

AzithromycinFootnote e

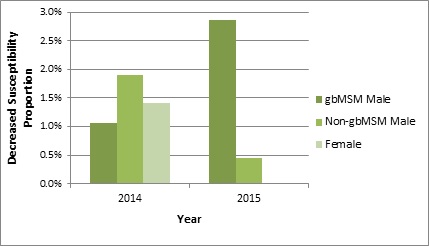

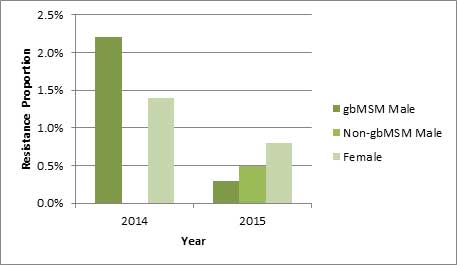

In 2014, 1.5% (7/458) of all isolates obtained from ESAG cases were resistant to azithromycin. This proportion decreased to 0.5% (3/660) in 2015 (Appendix C). All azithromycin resistant isolates identified were from Alberta. The proportion of azithromycin resistance in isolates from gbMSM males decreased from 2.2% (6/276) in 2014 to 0.3% (1/315) in 2015. In isolates from non-gbMSM males, the proportion increased slightly from 0% (0/104) in 2014 to 0.5% (1/221) in 2015, and the proportion of isolates from females decreased slightly from 1.4% (1/71) in 2014 to 0.8% (1/121) in 2015 (Appendix C and Figures 3a and 3b), as shown in Table 7.

Figure 3a. Distribution of azithromycin resistance by sex or sexual behaviour, ESAG 2014 and 2015

Distribution of azithromycin resistance by sex or sexual behaviour, ESAG 2014 and 2015 - Long description

The bar chart presents the percentage of ESAG isolates with resistance to azithromycin by sex or sexual behaviour groupings. The horizontal axis represents the year while the vertical axis represents the decreased susceptibility proportion.

| Sex or Sexual Behaviour | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|

| gbMSM males | 2.2 | 0.3 |

| Non-gbMSM males | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| Females | 1.4 | 0.8 |

Figure 3b. Distribution of azithromycin resistance by sex and infection site, ESAG 2014 and 2015

Footnote a 2014 denominators: cervix=53; urethra=214; pharynx-female=24; pharynx-male=126; rectum-female=18; rectum-male=124

2015 denominators: cervix=78; urethra=348; pharynx-female=52; pharynx-male=148; rectum-female=38; rectum-male=145

Distribution of azithromycin resistance by sex and infection site, ESAG 2014 and 2015 - Long description

The bar chart presents the percentage of ESAG isolates with resistance to azithromycin by sex and infection site groupings. The horizontal axis represents the year while the vertical axis represents the decreased susceptibility proportion.

| Sex or Sexual Behaviour and Infection Site | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|

| Cervix | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Urethra | 1.4 | 0.6 |

| Pharynx – Females | 4.2 | 1.9 |

| Pharynx – Males | 3.1 | 0.0 |

| Rectum – Females | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Rectum – Males | 0.8 | 0.0 |

Ciprofloxacin

The prevalence of ciprofloxacin resistance was 27.1% (124/458) in 2014 increasing slightly to 30.0% in (198/660) in 2015. A large increase was seen in isolates obtained from gbMSM males (30.4% to 47.9%) (Appendix C).

Tetracycline

About 49.8% (228/458) of isolates from ESAG cases were resistant to tetracycline in 2014 increasing to 56.2% (371/660) in 2015. A large increase was seen isolates from non-gbMSM males (27.9% to 45.2%) (Appendix C).

Penicillin

About 17.2% (79/458) of isolates from ESAG cases were resistant to penicillin in 2014 which decreased to 14.8% (98/660) in 2015 (Appendix C).

Erythromycin

Resistance to erythromycin remained fairly constant from 2014 to 2015 with 25.3% (116/458) of isolates exhibiting resistance in 2014 and 26.1% (172/660) in 2015. This increase mostly came from isolates from gbMSM cases, where an increase from 33.7% to 44.1% was seen (Appendix C).

Spectinomycin

No resistance to spectinomycin was identified in any of the submitted isolates in 2014 and 2015.

Multidrug Resistance

In both 2014 and 2015, isolates that had decreased susceptibility to cefixime and/or ceftriaxone were also resistant to one or more other antimicrobials; however, none of these isolates was resistant to azithromycin.

| Sex & Sexual Behaviour | Alberta | Manitoba | Nova Scotia | Overall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| CefiximeDS | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 |

| gbMSM Male | 5 (2.0) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.8) | 2 (0.6) |

| non-gbMSM Male | 5 (5.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (4.8) | 1 (0.5) |

| Female/Transgender | 5 (7.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (7.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Male-unknown | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (66.7) |

| Total | 15 (3.6) | 3 (0.5) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | 16 (3.5) | 5 (0.8) |

| CeftriaxoneDS | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 |

| gbMSM Male | 3 (1.2) | 9 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.1) | 9 (2.9) |

| non-gbMSM Male | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.9) | 1 (0.5) |

| Female/Transgender | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Male-unknown | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (66.7) |

| Total | 6 (1.4) | 9 (1.4) | 1 (4.0) | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | 7 (1.5) | 12 (1.8) |

| AzithromycinR | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 |

| gbMSM Male | 6 (2.4) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (2.2) | 1 (0.3) |

| non-gbMSM Male | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Female/Transgender | 1 (1.6) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.8) |

| Male-unknown | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Total | 7 (1.7) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (1.5) | 3 (0.5) |

|

||||||||

3.5 Sequence Typing (ST)

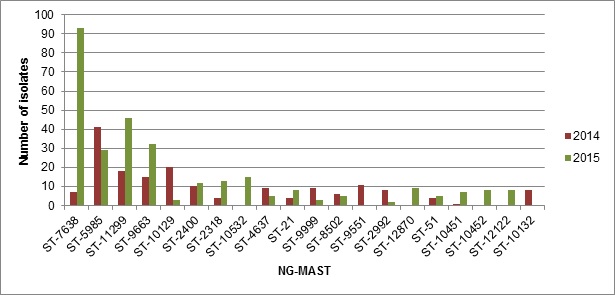

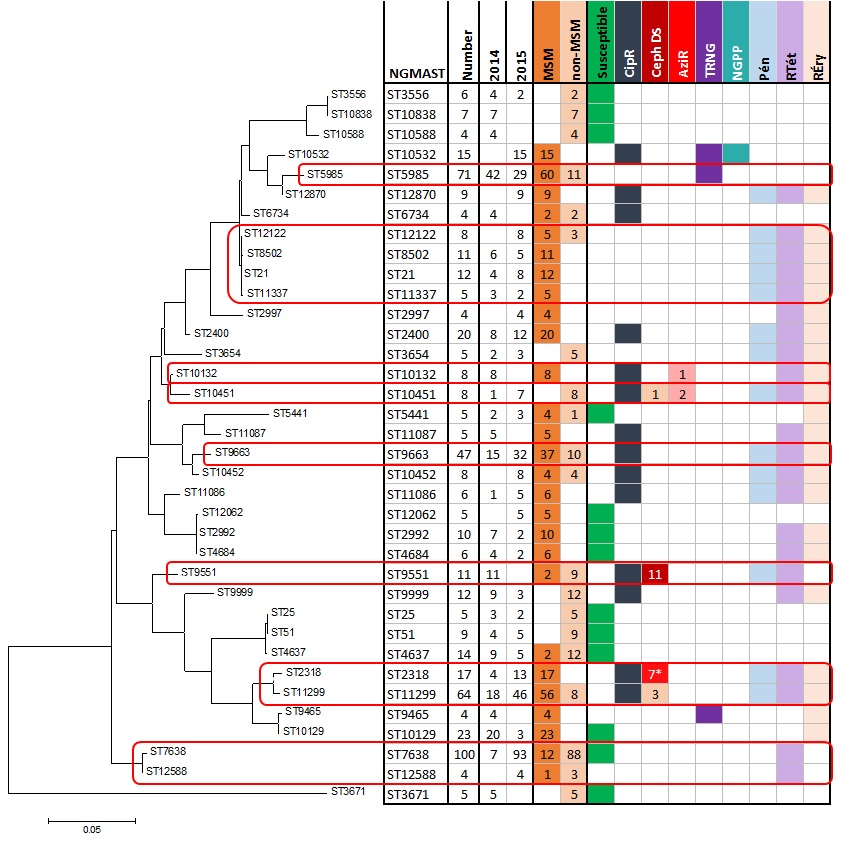

NG-MAST sequence typing of 778 isolates identified 197 different sequence types (STs). The 20 most prevalent STs in 2014 and 2015 are represented in Figure 4. In 2014, ST5985 (12.6%, 42/334) was the most prevalent ST followed by ST10129 (6.0%, 20/334) and ST11299 (5.4%, 18/334). In 2015, ST7638 (20.9%, 93/444) was the most prevalent ST, followed by ST11299 (10.4%, 46/444) and ST9663 (6.3%, 28/444). The three most prevalent sequence types in 2014 and 2015 combined were ST7638 at 12.9% (100/778), ST5985 at 9.1% (71/778) and ST11299 at 8.2% (64/778). Figure 5 represents the genetic relationship between 36 of the most prevalent STs using the Maximum Likelihood method.

- ST7638 (n=100) was identified in seven isolates in 2014 and 93 isolates in 2015.

- ST12588 (n=4), which differs from ST7638 by only two base pairs, was only identified in 2015.

- Isolates in this cluster were either tetracycline resistant or susceptible, and over 85% (91/104) were from non-gbMSM, including females (Figure 5).

- ST5985 (n=71) was identified in 42 isolates from 2014 and 29 isolates from 2015. All ST5985 isolates were high-level, plasmid mediated tetracycline resistant N. gonorrhoeae (TRNG), and over 80% (60/71) were from gbMSM males (Figure 5). All ESAG ST5985 were from Alberta except for one which was from Manitoba. ST5985 was the most prevalent ST identified across Canada in 2015, identified in Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta and SaskatchewanFootnote 20.

- ST11299 (n=64) was identified in 18 isolates in 2014 and 46 isolates in 2015. ST11299 is prevalent across Canada and is multi-drug resistant (CMRNG/CipR – see Appendix B). Three of the ESAG ST11299 had decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins as well. Over 85% (56/64) of these isolates were from gbMSM males (Figure 5).

- ST2318 (n=17) differs from ST11299 by only six base pairs and is also multidrug resistant (CMRNG/CipR). Over 50% (7/13) of the 2015 isolates with this ST also had decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins. One of the isolates was from Nova Scotia; the remaining were from Alberta. All of the isolates with this ST were from gbMSM males (Figure 5).

- ST9663 (n=47) was identified in 25 isolates in 2014 and 32 isolates in 2015. The isolates were multi-drug resistant (CMRNG/CipR) and 78.7% (37/47) were from gbMSM males (Figure 5). While most of the ST9663 isolates were identified in Alberta, there were five from Manitoba with the same antimicrobial resistance.

- ST10129 (n=23) was identified in Alberta, 20 isolates in 2014 and only three isolates in 2015. These isolates were either susceptible or erythromycin resistant and were all from gbMSM males (Figure 5).

- ST2400 (n=20) was identified in eight isolates in 2014 and 12 isolates in 2015. One of the isolates was from Nova Scotia; the remaining were from Alberta. Isolates were multi-drug resistant (CMRNG/CipR) and were all from gbMSM males. ST2400 was the second most prevalent ST identified across Canada in 2015Footnote 20 according to routine NML data (Figure 5).

- ST10451 (n=8) was identified in one isolate from 2014 and seven from 2015. The isolates were multidrug resistant (CMRNG/CipR); two were also resistant to azithromycin and another had decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins. One of the seven ST10451 isolates identified in 2015 was from Manitoba and had decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone; the remaining six isolates were from Alberta. ST10451 was the third most prevalent ST identified across Canada in 2015 and is closely related to the internationally identified clone, ST1407 that has been described as a superbug with high-level resistance to cephalosporinsFootnote 7Footnote 21Footnote 22 (Figure 5).

- The closely related STs that are clustered around ST21 are all within two base pairs of each other. The 36 isolates in this cluster are all resistant to penicillin, tetracycline and erythromycin (CMRNG) and over 90% (33/36) are from gbMSM males (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Frequency of NG-MAST sequence types in N. gonorrhoeae isolates, ESAG 2014 and 2015

Frequency of NG-MAST sequence types in N. gonnorhoeae isolates, ESAG 2014 and 2015 - Long description

This bar chart presents the number of isolates for the 20 most frequent isolates that were tested using NG-MAST method. The horizontal axis represents the different sequence types while the vertical axis shoes the number of isolates.

| Sequence Type | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|

| ST-7638 | 7 | 93 |

| ST-5985 | 41 | 29 |

| ST-11299 | 18 | 46 |

| ST-9663 | 15 | 32 |

| ST-10129 | 20 | 3 |

| ST-2400 | 10 | 12 |

| ST-2318 | 4 | 13 |

| ST-10532 | 0 | 15 |

| ST-4637 | 9 | 5 |

| ST-21 | 4 | 8 |

| ST-9999 | 9 | 3 |

| ST-8502 | 6 | 5 |

| ST-9551 | 11 | 0 |

| ST-2992 | 8 | 2 |

| ST-12870 | 0 | 9 |

| ST-51 | 4 | 5 |

| ST-10451 | 1 | 7 |

| ST-10452 | 0 | 8 |

| ST-12122 | 0 | 8 |

| ST-10132 | 8 | 0 |

Figure 5. Genetic relationship of prevalent NG-MAST sequence types of N. gonorrhoeae, ESAG 2014 and 2015Footnote **

Genetic relationship of prevalent NG-MAST sequence types of N. gonorrhoeae, ESAG 2014 and 2015 - Long description

This dendrogram shows the genetic relationship between 36 of the most prevalent sequence types using the maximum likelihood method. The left-most section of the figure shows the phylogenetic relationships and relatedness of each ST - the branch length of the tree represents the number of base pair substitutions per site. The corresponding table on the right shows the NG-MAST (STs) in the rows, and the number of each ST, the year, the sex/sexual behaviour, and the resistance characterization (CipR, CephDS, AzR, TRNG, PPNG, PenR, TetR, EryR) as the column labels. Each vsariable for the column is coloured and the presence of the variable corresponds to the matching colour present in the NG-MAST row. There are eight groups highlighted in red boxes.

| ST-5985 | This ST, identified in both 2014 and 2015, in primarily gbMSM, has high level resistance to tetracycline (TRNG) |

| ST-12122 ST-8502 ST-21 ST-133 |

The STs in this cluster are all closely related (within two base pairs) and are primarily found in gbMSM. They are all CMRNG |

| ST-10132 | This ST was identified in 2014 in gbMSM and is resistant to ciprofloxacin, tetracycline and erythromycin. One isolate with this ST was resistant to azithromycin |

| ST-10451 | This ST is multi-drug resistant (CMRNG/CipR) and was found in non-gbMSM males. One of the isolates identified also had decreased susceptibility to a cephalosporin. Two of the isolates were also resistant to azithromycin |

| ST-9663 | The isolates of this ST are CMRNG/CipR with about 75% identified in gbMSM |

| ST-9551 | This ST was identified in 2014 in primarily non-gbMSM males, and shows resistance to ciprofloxacin, penicillin, tetracycline and reduced susceptibility to cephalosporins |

| ST-2318 ST-11299 |

This cluster is found primarily in gbMSM, prevalent across Canada and multi-drug resistant. Approximately 10% had reduced susceptibility to cephalosporins as well |

| ST-7638 ST-12588 |

This cluster is found primarily in non-gbMSM males and is either susceptible or resistant to tetracycline. ST-7638 was the most prevalent ST identified in 2015 |

- Footnote 1

-

2015 only

- Footnote 2

-

Dendrogram represents 36 of the most prevalent sequence types identified in 2014 and 2015 (197 STs in total) and includes data from 557 of the 1118 isolates (2014 - 221/458; 2015 - 335/660)

- Footnote 3

-

† non-gbMSM includes females in this figure

3.6 Treatment

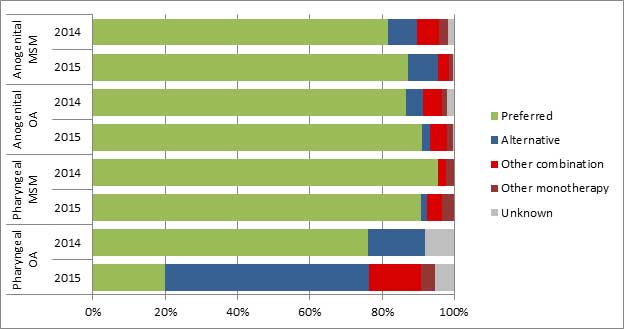

Treatment information was available for 97.6% (n=447) and 99.1% (n=654) of the gonorrhoea positive patients in 2014 and 2015, respectively. Adherence to the treatment recommended in the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted InfectionsFootnote 3 (Table 8) was above 80% for all treatment groups, except for other adults with pharyngeal infections. In this category, 76% of cases received a preferred treatment in 2014; this proportion fell to 20% in 2015 (Figure 6).

| Infection Type | Treatment | gbMSM | Other Adults |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anogenital Infections | Preferred therapy | Ceftriaxone 250mg + azithromycin 1g | Ceftriaxone 250mg + azithromycin 1g |

| Preferred therapy | n/a | Cefixime 800mg + azithromycin 1g | |

| Alternative therapy | Cefixime 800mg + azithromycin 1g OR Azithromycin 2g OR Spectinomycin 2g + azithromycin 1g |

Spectinomycin 2g + azithromycin 1g OR Azithromycin 2g |

|

| Pharyngeal Infections | Preferred therapy | Ceftriaxone 250mg + azithromycin 1g | Ceftriaxone 250mg + azithromycin 1g |

| Alternative therapy | Cefixime 800mg + azithromycin 1g | Cefixime 800mg + azithromycin 1g OR Azithromycin 2g |

The majority of anogenital infections among other adults were treated with preferred therapy in both 2014 (86.7%) and 2015 (90.9%). The two preferred combination therapies were equally prescribed (44.0% for the ceftriaxone and azithromycin treatment, 42.7% for the cefixime and azithromycin treatment) for anogenital infections among other adults in 2014 (Table 9). In 2015, this trend changed and the treatment of cefixime and azithromycin accounted for 81.9% of treatments for anogenital infections among other adults, while the ceftriaxone combination was used in only 9.1% of cases. The same trend was seen in other adults with pharyngeal infections. In 2014, the proportion of cases with the ceftriaxone combination and cefixime combination was 76.0% and 16.0%, respectively. In 2015, it shifted to 20.0% and 50.9%.

Figure 6. Adherence to Canadian Treatment Guidelines for gbMSM and Other AdultsFootnote *, ESAG 2014 and 2015

Adherence to Canadian Treatment Guidelines for gbMSM and Other Adults, ESAG 2014 and 2015 - Long description

This stacked bar graph displays the percentage of gbMSM and other adults with either anogenital or pharyngeal infections that were treated with the preferred, alternative, other combination and other monotherapy according to Canadian Treatment Guidelines. The horizontal axis represents the percent adherence to the treatment guidelines and the vertical axis represents the infection type (anogenital or pharyngeal) in gbMSM and other adults grouped by year.

| Treatment | Anogenital gbMSM | Anogenital Other Adults | Pharyngeal gbMSM | Pharyngeal Other Adults | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| Preferred | 81.6 | 87.2 | 86.7 | 90.9 | 95.6 | 90.8 | 76.0 | 20.0 |

| Alternative | 8.1 | 8.2 | 4.7 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 16.0 | 56.4 |

| Other Combination | 5.9 | 3.1 | 5.3 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 14.5 |

| Other Monotherapy | 2.7 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 3.6 |

| Unknown | 1.6 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.0 | 5.5 |

Footnotes

- Footnote 1

-

Other Adults (OA) includes non-gbMSM males and females. It does not include males with unknown sexual behaviour.

| Infection Type and Sexual Behaviour | Treatment | 2014Footnote * | 2015Footnote ** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| AnogenitalFootnote † | gbMSM | (P) Ceftriaxone 250 mg, Azithromycin 1 g | 151 | 81.6 | 171 | 87.2 |

| (A) Cefixime 800 mg, Azithromycin 1 g | 6 | 3.2 | 10 | 5.1 | ||

| (A) Azithromycin 2 g | 8 | 4.3 | 6 | 3.1 | ||

| (N) Ceftriaxone 250 mg, Azithromycin 1 g, Doxycycline 100 mg | 2 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Other | 18 | 9.7 | 9 | 4.6 | ||

| Total | 185 | 100 | 196 | 100 | ||

| Other Adults | (P) Ceftriaxone 250 mg, Azithromycin 1 g | 66 | 44.0 | 26 | 9.1 | |

| (P) Cefixime 800 mg, Azithromycin 1 g | 64 | 42.7 | 235 | 81.9 | ||

| (A) Azithromycin 2 g | 6 | 4.0 | 7 | 2.4 | ||

| (N) Cefixime 800 mg, Ceftriaxone 250 mg, Azithromycin 1 g | 3 | 2.0 | 6 | 2.1 | ||

| Other | 11 | 7.3 | 13 | 4.5 | ||

| Total | 150 | 100 | 287 | 100 | ||

| Pharyngeal | gbMSM | (P) Ceftriaxone 250 mg, Azithromycin 1 g | 87 | 95.6 | 108 | 90.8 |

| (A) Cefixime 800 mg, Azithromycin 1 g | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.7 | ||

| (N) Azithromycin 2 g | 1 | 1.1 | 3 | 2.5 | ||

| (N) Ceftriaxone 250 mg, Doxycycline 100 mg | 1 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.8 | ||

| Other | 2 | 2.2 | 5 | 4.2 | ||

| Total | 91 | 100 | 119 | 100 | ||

| Other Adults | (P) Ceftriaxone 250 mg, Azithromycin 1 g | 19 | 76.0 | 11 | 20.0 | |

| (A) Cefixime 800 mg, Azithromycin 1 g | 4 | 16.0 | 28 | 50.9 | ||

| (A) Azithromycin 2 g | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 5.5 | ||

| (N) Cefixime 800 mg, Ceftriaxone 250 mg, Azithromycin 1 g | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 7.3 | ||

| Other | 2 | 8.0 | 9 | 16.4 | ||

| Total | 25 | 100 | 55 | 100 | ||

(P) - Preferred treatment in the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections – Gonococcal Infections Chapter, Revised July 2013 (treatment guidelines)Footnote 3

|

||||||

4.0 Discussion

This is the second ESAG report that summarizes gonococcal susceptibility data and describes the public health implications of emerging resistance to cephalosporins and azithromycin.

As a result of the ESAG initiative, partner laboratories submitted increased numbers of gonorrhea isolates to enable improved analysis and information. In 2013, there were 124 cultures from the two sites that were a part of ESAG. In 2014, these same two sites submitted 534 cultures and two new sites began participation; 786 cultures were captured from four jurisdictions in 2015. The likelihood that these cultures could have been captured by routine laboratory surveillance by the NML cannot be ruled out; however, ESAG allows for the capture of additional epidemiological information to better understand treatments, populations, and risk factors involved with gonorrheal infections.

Over 80% of cases captured in ESAG were male. This is consistent with historical data, which show that in 2013, 60% of reported gonorrhea cases in Canada were among malesFootnote 1. This could also suggest that males, especially gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM), were overrepresented in ESAG because gbMSM males are more likely to be asked for a specimen for culture in accordance with the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections.

On average, female ESAG cases were younger than their male counterparts across all four jurisdictions. National rates of reported cases of gonorrhea in 2014 and 2015 were higher among females than males who were less than 20 years of age; in contrast, among adults age 20 years and older, males exhibited higher ratesFootnote 1. Although ESAG data seemed to follow these trends, the sample size did not allow for analyses by both age group and sex.

Approximately half of the ESAG cases who provided specimens for culture sought health care due to symptoms, which would be consistent with the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections’ recommendation for obtaining cultures from symptomatic gbMSM and non-gbMSM. However, among gbMSM, approximately one third reported STI screening or being a case contact as the reason for their visit. The two most common reasons for females seeking treatment were the presence of symptoms and being a case contact; however, this varied across sentinel sites, and because the number of female cases in ESAG was low, it was difficult to detect a consistent pattern.

Between 2014 and 2015, the proportion of azithromycin resistance in all isolates from ESAG cases decreased from 1.5% to 0.5%, influenced by the decrease in resistance observed in isolates obtained from gbMSM and females. There was a minimal increase in this proportion in isolates obtained from non-gbMSM from 0% in 2014 to 0.5% in 2015.

The proportion of isolates with decreased susceptibility to cefixime in all ESAG jurisdictions combined, decreased from 3.5% in 2014 to 0.8% in 2015. This decrease is larger in isolates obtained from non-gbMSM males (4.8% in 2014 to 0.5% in 2015) and females (7.0% in 2014 to 0% in 2015) than in gbMSM (1.8% in 2014 to 0.6% in 2015). In line with World Health Organization recommendations for when the proportion of resistant strains is at a level of 5% or more, or when any unexpected increase below 5% is seen in key populations (i.e., gbMSM or sex workers), Canada reviews and modifies their national guidelines for treatment and managementFootnote 4.

Treatment data for ESAG isolates indicate that the use of cefixime (800 mg) and azithromycin (1 g) for non-gbMSM (including females) increased from 42.7% in 2014 to 81.9% in 2015 for anogenital infections, and from 16.0% in 2014 to 56.4% in 2015 for pharyngeal infections. The low use of cefixime in 2014 was likely caused by a shortage that occurred during that time period. The participating clinics in Alberta subsequently switched to ceftriaxone in June 2014. This was reversed in January 2015, and subsequently an increase in cefixime treatments in ESAG was observed. Therapy using cefixime (800 mg) and azithromycin (1 g) among gbMSM remained low for both anogenital and pharyngeal infections. The cefixime shortage did not appear to affect the other two jurisdictions in the same way.

While the overall proportion of decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone in all ESAG jurisdictions increased slightly (1.5% to 1.8%), the proportion among isolates from non-gbMSM males and females decreased between 2014 and 2015. The proportion of isolates from gbMSM males with decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone increased from 1.1% in 2014 to 2.9% in 2015.

The single preferred treatment for treating both anogenital and pharyngeal infections in gbMSM (ceftriaxone (250 mg) and azithromycin (1 g) therapy) has remained the most prevalent treatment for these cases. However, this combination therapy has decreased in use for treating non-gbMSM (including females) from 44.0% in 2014 to 9.1% in 2015 for anogenital infections, and from 76.0% in 2014 to 20.0% in 2015 for pharyngeal infections. For anogenital infections in non-gbMSM this isn’t a problem as the 2nd preferred therapy of cefixime (800 mg) and azithromycin (1 g) has increased from 42.7% in 2014 to 81.9% in 2015. There may be cause for concern, however, that pharyngeal infections in non-gbMSM (including females) were treated with the alternate therapy (cefixime 800mg and azithromycin 1g) in half the cases (50.9%), with other therapies being used more than the preferred (29.2% compared to 20.0%, respectively) in 2015. This may be a result of pharyngeal infections often being asymptomatic; with the clinician only finding a positive result after the treatment was prescribed for the anogenital infection.

In 2015, the proportions of decreased susceptibility to cefixime and ceftriaxone and resistance to azithromycin determined in combined ESAG jurisdictions differed from rates identified in the national passive laboratory surveillance system. Nationally, decreased susceptibility to cefixime was 1.9% compared to the ESAG rate of 0.8%. Decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone was 3.5% nationally and was only 1.8% in ESAG jurisdictions. Similarly, azithromycin resistance was much higher nationally at 4.7% than the 0.5% found in ESAG jurisdictions, due to higher azithromycin resistance in Quebec and Ontario isolatesFootnote 20.

Gonococcal isolates with decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins were identified in high-risk and frequently transmitting populations such as gbMSM. As ceftriaxone and cefixime, in combination with azithromycin, are the recommended options for preferred therapy of gonorrhea, the emergence of gonococci resistant to these antimicrobials might initiate an era of gonorrhea that would be untreatable using any of these antimicrobials as combined therapy. It is critical to intensify AMR surveillance and expand ESAG geographical coverage for identification and monitoring across Canada of further spread of gonococci resistant to these antimicrobials.

Sequence typing (ST) of gonorrhea is a highly discriminatory typing method that helps monitor the spread of antimicrobial resistant clones and identify transmission patterns within sexual networks. ST11299 and ST9663 were both associated with multi-drug resistance and ST5985 was associated with tetracycline resistance; they were all identified predominantly in the gbMSM population. Overall, ST7638 was the most prevalent ST identified in 2014 and 2015 combined at 12.9%. It was by far the most prevalent ST identified in 2015 at 20.9%; ten times more frequent than in 2014 at 2.1%. ST7638 is the fourth most prevalent ST nationally (5.69%). ST7638 isolates are predominately tetracycline resistant (low level) with approximately 10% being susceptible.

The majority of cases at the four participating sites were prescribed either preferred or alternative therapies as currently proposed by the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted InfectionsFootnote 3. This high degree of consistency is likely due to the familiarity of the clinicians at STI clinics with the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections and may not necessarily be indicative of general practitioners’ prescribing behaviours. According to a recent study on the antibiotic management of gonorrhea in Ontario, Canada, adherence to first-line treatment recommendations decreased to below 30% following the release of the 2011 recommendationsFootnote 23. After the latest Ontario guidelines were released in 2013, approximately 40% of patients did not receive first-line treatment, putting them at risk of treatment failure and potentially promoting further drug resistanceFootnote 23. Public health organizations should consider ways to enhance the uptake of new guidelines, as and when the gonorrhea treatment recommendations change due to antimicrobial resistance patterns. Therefore, it becomes increasingly desirable to develop active guidelines dissemination and implementation strategies to accelerate clinicians’ uptake of new recommendations for gonorrhea treatment.

Frontline clinicians may also not have access to intramuscularly injected ceftriaxone and may defer to the use of oral cefixime even in pharyngeal cases. As well, pharyngeal infections are often asymptomatic; with the clinician only finding a positive result after the treatment was prescribed for the anogenital infection. Another possibility is that a patient presents with genitourinary symptoms and is treated empirically using cefixime and azithromycin with the pharynx being asymptomatic and the clinician only getting confirmation of a positive after the visit and, as a result, opts for a test of cure rather than retreatment given the low levels of decreased susceptibility to cefixime. Because dosage information was not available for some cases, it is possible that adherence to recommended therapies may have been even higher than presented at the ESAG sentinel sites. A large number of other combination therapies were comprised of cases where a preferred therapy appeared to be provided without dosage information, or in combination with another drug.

4.1 Limitations

Results from ESAG are not representative of all gonorrhea cases or culture-confirmed gonorrhea cases in Canada. Similarly, sentinel sites may not be representative of their jurisdiction. In addition to limited geographic representation, ESAG cases may have been over-represented by gbMSM. Because the majority of cases in ESAG were from Alberta, any aggregated results should be interpreted with caution. Moreover, the small number of ESAG cases in Winnipeg and Halifax made some data difficult to interpret.

The relative representativeness of gbMSM, non-gbMSM and females may vary across these sub-populations. This variation may be associated with proportion of participation per sub-population and profile of those who visited the ESAG sites. For example, the participating gbMSM could represent all gbMSM cases from those jurisdictions in terms of risk behaviours, while the participating females and non-gbMSM could be more at risk compared to their source sub-populations.

The proportion of infection sites of the different sexes and risk behaviour groups may be biased according to the screening guidelines of each sentinel site or provincial jurisdiction. The low numbers of isolates with decreased susceptibility to cephalosporins and resistance to azithromycin made it difficult to determine significant increases and decreases between 2014 and 2015 or significant differences between isolates from different infection sites, sexes and sexual behaviours.

The collection of preferred and alternate treatment data from sentinel sites reflected the prescribing practices in the participating STI clinics and was not expected to reflect gonorrhea treatment practices in non-participating STI clinics in all three provincial jurisdictions where the majority of gonorrhea cases were diagnosed in 2014 and 2015. Also, provincial treatment guidelines and availability of preferred antimicrobials may have influenced chosen therapies; a client may have had other empiric therapies based on risks or presentations during an initial visit, prior to being diagnosed with gonorrhea.

The completion rate of some variables was low and/or limited to certain sentinel sites and this is another reason these results would not likely reflect the overall Canadian context. In addition, some of the variables rely on self-reported data, which may not be accurate and could result in under- or over-reporting.

All of the isolates from ESAG cases were from swabs taken during initial visits or call-backs after a positive nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) from the initial visit. No known treatment failures were reported in any of the four participating jurisdictions for the study period. However, people may not have returned for a test of cure or may not have returned to a participating clinic/physician for follow-up. Because detailed clinical information, such as allergies, other infections or contraindications, was not collected for ESAG, it was not possible to definitively determine why the preferred or alternative treatment was not prescribed. Tests of cure and treatment failures can be difficult to measure using surveillance data because they rely on the ability to detect negative results.

4.2 Conclusion

The Enhanced Surveillance of Antimicrobial-Resistant Gonorrhea (ESAG) initiative monitored N. gonorrhoeae antimicrobial susceptibility in 2014 and 2015 in participating jurisdictions and provided additional information to supplement the laboratory-based passive surveillance of antimicrobial resistant gonorrhea. The ESAG data for 2014 and 2015 demonstrated decreased susceptibility to antimicrobials recommended for preferred therapy such as ceftriaxone, cefixime, and resistance to azithromycin. This suggests that decreased susceptibility or resistance to these antimicrobials could complicate gonorrhea treatment substantially in the future.

The ESAG initiative provides useful integrated epidemiological and laboratory data describing the risk behaviours, clinical information, and antimicrobial susceptibility rates of gonococcal disease that would have otherwise not been available nationally. This project determined that it is possible to conduct surveillance of gonorrhea resistance at sentinel sites across Canada by integrating existing local/ provincial/ territorial surveillance. However, the number of sites able to collect such data remains limited and the expansion of ESAG’s scope nationally remains a priority.

As Canada deals with increasing cases of gonorrhea and the continued evolution, emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance, efforts are ongoing to recruit additional ESAG sites to allow the collection of more representative data which in turn would be more useful for informing treatment guidelines, clinical practice, and public health interventions. The ESAG program has allowed the monitoring of gonococcal antimicrobial susceptibility despite the decreasing use of culture in clinical practice for gonorrhea diagnosis and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. The recent report of a N. gonorrhoeae strain resistant to ceftriaxone in Quebec, Canada, poses a potential threat to the combination therapy currently being used to treat gonorrhea in Canada(24). The continuous monitoring of antimicrobial resistance patterns via surveillance is of paramount importance to ensure the effectiveness of the recommended antimicrobials to treat gonococcal infection. The ESAG program can play an important role in assessing and monitoring the effectiveness of gonococcal treatment options and for the success of Canadian initiatives to combat AMR.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Notifiable Diseases On-Line. Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control, Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada, 2017.

- Footnote 2

-

Barry PM, Klausner JD. The use of cephalosporins for gonorrhea: The impending problem of resistance. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2009;10:555-577.

- Footnote 3

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections, Gonococcal Infections: Revised July 2013. [cited 22 July 2014]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/infectious-diseases/sexual-health-sexually-transmitted-infections/canadian-guidelines/sexually-transmitted-infections/canadian-guidelines-sexually-transmitted-infections-34.html.

- Footnote 4

-

World Health Organization. Global action plan to control the spread and impact of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. [cited 12 June 2012]. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/9789241503501/en/.

- Footnote 5

-

Unemo M, Shafer WM. Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the 21st Century: Past, evolution, and future. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014; 27(3): 587-613.

- Footnote 6

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013.

- Footnote 7

-

Allen VG, Mitterni L, Seah C, Rebbapragada A, Martin IE, Lee C, Siebert H, Towns L, Melano RG, Lowe DE. Neisseria gonorrhoeae treatment failure and susceptibility to cefixime in Toronto, Canada. JAMA 2013; 309: 163-170.

- Footnote 8

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. 2017-18 Departmental Plan 2017. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/corporate/transparency/corporate-management-reporting/reports-plans-priorities/2017-2018-report-plans-priorities-eng.pdf.

- Footnote 9

-

House of Commons, Standing Committee on Health (HESA). A Study on the Status of Antimicrobial Resistance in Canada and Related Recommendations 2018. https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HESA/Reports/RP9815159/hesarp16/hesarp16-e.pdf.

- Footnote 10

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System 2017 Report 2017. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/drugs-health-products/canadian-antimicrobial-resistance-surveillance-system-2017-report-executive-summary/CARSS-Report-2017-En.pdf.

- Footnote 11

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. A Pan-Canadian Framework for Action: Reducing the Health Impact of Sexually Transmitted and Blood-borne Infections in Canada by 2030. 2018. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/infectious-diseases/sexual-health-sexually-transmitted-infections/reports-publications/sexually-transmitted-blood-borne-infections-action-framework/sexually-transmitted-blood-borne-infections-action-framework.pdf.

- Footnote 12

-

Martin I, Sawatzky P, Liu G, and Mulvey MR. Antimicrobial resistance to Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Canada: 2009-2013. Canada Communicable Disease Report February 5, 2015; 41-02: 35-41.

- Footnote 13

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Case definitions for communicable diseases under national surveillance. Canada Communicable Disease Report 2009;3552: June 6, 2016.

- Footnote 14

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Twenty-fifth international supplement. CLSI document, approved Standard M100-S25. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015.

- Footnote 15

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2007 Supplement, Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) Annual Report 2007. Atlanta, GA. [cited 30 November 2010]. http://www.cdc.gov/std/gisp2007/gispsurvsupp2007short.pdf.

- Footnote 16

-

Ehret JM, Nims LJ, Judson FN. A clinical isolate of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with in vitro resistance to erythromycin and decreased susceptibility to azithromycin. Sex Transm Dis 1996; 23(4): 270-272.

- Footnote 17

-

Martin IMC, Ison CA, Aanensen DM, et al. Rapid sequence-based identification of gonococcal transmission clusters in a large metropolitan area. J Infect Dis 2004; 189: 1497-1505.

- Footnote 18

-

Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigam PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007; 23(21): 2947-2948.

- Footnote 19

-

Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol 1993;10:512-526.

- Footnote 20

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. National Surveillance of Antimicrobial Susceptibilities of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Annual Summary 2015.

- Footnote 21

-

Unemo M, Golparian D, Syversen G, Vestrheim DF, Mol H. Two cases of verified clinical failures using internationally recommended first-line cefixime for gonorrhoea treatment, Norway, 2010. Eurosurveillance 2010; 15(47) : pii=19721.

- Footnote 22

-

Unemo M, Golparian D, Potočnik M, Jeverica S. Treatment failure of pharyngeal gonorrhoea with internationally recommended first-line ceftriaxone verified in Slovenia, September 2011. Eurosurveillance 2012; 17(25): pii=20200.

- Footnote 23

-

Dickson C, Taljaard M, Friedman DS, Metz G, Wong T, Grimshaw JM. The antibiotic management of gonorrhoea in Ontario, Canada following multiple changes in guidelines: An interrupted time-series analysis. Sex Transm Infect Published Online First: 26-08-2017. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2017-053224, pp 1-6.

- Footnote 24

-

Lefebvre B, Martin I, Demczuk W, Deshaies L, Michaud S, Labbé A-C, Beaudoin M-C, Longtin J. Ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Canada, 2017. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2018; 24(2): 381-383.

Appendix A

| Antibiotic | Recommended Testing Concentration Ranges (mg/L) | MIC Interpretive Standard (mg/L)Footnote a | Sources of Antibiotics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFootnote b | DSFootnote c | IFootnote d | RFootnote e | |||

| Penicillin | 0.032 – 128.0 | ≤ 0.06 | n/a | 0.12- 1.0 | ≥ 2.0 | Sigma |

| Tetracycline | 0.064 – 64.0 | ≤ 0.25 | n/a | 0.5 - 1.0 | ≥ 2.0 | Sigma |

| Erythromycin | 0.032 – 32.0 | ≤ 1.0 | n/a | n/a | ≥ 2.0 | Sigma |

| Spectinomycin | 4.0 – 256.0 | ≤ 32.0 | n/a | 64 | ≥ 128.0 | Sigma |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.001 – 64.0 | ≤ 0.06 | n/a | 0.12 - 0.5 | ≥ 1.0 | Bayer Health Care |

| Ceftriaxone | 0.001 – 2.0 | n/a | ≥ 0.125 | n/a | n/a | Sigma |

| Cefixime | 0.002 – 2.0 | n/a | ≥ 0.25 | n/a | n/a | Sigma |

| Azithromycin | 0.016 – 32.0 | ≤ 1.0 | n/a | n/a | ≥ 2.0 | Pfizer |

| Ertapenem | 0.002 – 2.0 | Interpretive Standards Not Available | Sequoia | |||

| Gentamicin | 0.5 – 128.0 | Interpretive Standards Not Available | MP Biomedicals | |||

|

||||||

Appendix B

| Characterization | Description | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| PPNG | Penicillinase Producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Pen MIC ≥ 2.0 mg/L, β-lactamase positive, β-lactamase plasmid (3.05, 3.2 or 4.5 Mdal plasmid) |

| TRNG | Tetracycline Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Tet MIC ≥ 16.0 mg/L, 25.2 Mdal plasmid, TetM PCR positive |

| CMRNG | Chromosomal Mediated Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Pen MIC ≥ 2.0 mg/L, Tet MIC ≥ 2.0 mg/L but ≤ 8.0 mg/L, and Ery MIC ≥ 2.0 mg/L |

| Probable CMRNG | Probable Chromosomal Mediated Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae | One of the MIC values of Pen, Tet, Ery = 1 mg/L, the other two ≥ 2.0 mg/L |

| PenR | Penicillin Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Pen MIC ≥ 2.0 mg/L, β-lactamase negative |

| TetR | Tetracycline Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Tet MIC ≥ 2.0 mg/L but ≤ 8.0 mg/L |

| EryR | Erythromycin Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Ery MIC ≥ 2.0 mg/L |

| CipR | Ciprofloxacin Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Cip MIC ≥ 1.0 mg/L |

| AzR | Azithromycin Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Az MIC ≥ 2.0 mg/L |

| SpecR | Spectinomycin Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Spec R ≥ 128 mg/L |

| CxDS | Neisseria gonorrhoeae with decreased susceptibility to Ceftriaxone | Cx MIC ≥ 0.125 mg/L |

| CeDS | Neisseria gonorrhoeae with decreased susceptibility to Cefixime | Ce MIC ≥ 0.25 mg/L |

Appendix C

| Antimicrobial ResistanceFootnote * | 2014 | 2015 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gbMSM Male | n | (%) | n | (%) |

| CefiximeDSFootnote * | 5 | 1.8 | 2 | 0.6 |

| CeftriaxoneDSFootnote * | 3 | 1.1 | 9 | 2.9 |

| AzithromycinRFootnote * | 6 | 2.2 | 1 | 0.3 |

| CiprofloxacinRFootnote * | 84 | 30.4 | 151 | 47.9 |

| TetracyclineRFootnote * | 170 | 61.6 | 222 | 70.5 |

| PenicillinRFootnote * | 57 | 20.7 | 68 | 21.6 |

| ErythromycinRFootnote * | 93 | 33.7 | 139 | 44.1 |

| Susceptible to all antibiotics tested | 94 | 34.1 | 75 | 23.8 |

| Total MSM | 276 | 100 | 315 | 100 |

| Non-gbMSM Male | n | (%) | n | (%) |

| CefiximeDSFootnote * | 5 | 4.8 | 1 | 0.5 |

| CeftriaxoneDSFootnote * | 2 | 1.9 | 1 | 0.5 |

| AzithromycinRFootnote * | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.5 |

| CiprofloxacinRFootnote * | 20 | 19.2 | 30 | 13.6 |

| TetracyclineRFootnote * | 29 | 27.9 | 100 | 45.2 |

| PenicillinRFootnote * | 10 | 9.6 | 21 | 9.5 |

| ErythromycinRFootnote * | 10 | 9.6 | 24 | 10.9 |

| Susceptible to all antibiotics tested | 66 | 63.5 | 117 | 52.9 |

| Total Non-MSM | 104 | 100 | 221 | 100 |

| Female | n | (%) | n | (%) |

| CefiximeDSFootnote * | 5 | 7.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| CeftriaxoneDSFootnote * | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| AzithromycinRFootnote * | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.8 |

| CiprofloxacinRFootnote * | 17 | 23.9 | 15 | 12.4 |

| TetracyclineRFootnote * | 23 | 32.4 | 46 | 38.0 |

| PenicillinRFootnote * | 7 | 9.9 | 7 | 5.8 |

| ErythromycinRFootnote * | 9 | 12.7 | 7 | 5.8 |

| Susceptible to all antibiotics tested | 44 | 62.0 | 72 | 59.5 |

| Total Females | 71 | 100 | 121 | 100 |

| OverallFootnote ** | n | (%) | n | (%) |

| CefiximeDSFootnote * | 16 | 3.5 | 5 | 0.8 |

| CeftriaxoneDSFootnote * | 7 | 1.5 | 12 | 1.8 |

| AzithromycinRFootnote * | 7 | 1.5 | 3 | 0.5 |

| CiprofloxacinRFootnote * | 124 | 27.1 | 198 | 30.0 |

| TetracyclineRFootnote * | 228 | 49.8 | 371 | 56.2 |

| PenicillinRFootnote * | 79 | 17.2 | 98 | 14.8 |

| ErythromycinRFootnote * | 116 | 25.3 | 172 | 26.1 |

| Susceptible to all antibiotics tested | 205 | 44.8 | 264 | 40.0 |

| Grand Total | 458 | 660 | ||

|

||||

| 2014 TotalsFootnote ** | CefiximeDSFootnote * | CeftriaxoneDSFootnote * | AzithromycinRFootnote * | PenicillinRFootnote * | TetracyclineRFootnote * | ErythromycinRFootnote * | CiprofloxacinRFootnote * | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Female | 93 | 6 | 6.5 | 1 | 1.1 | 1 | 1.1 | 11 | 11.8 | 30 | 32.3 | 13 | 14.0 | 23 | 24.7 |