A Dementia Strategy for Canada: Together We Achieve - 2022 Annual Report

Download in PDF format

(5.5 MB, 102 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: January 2023

Cat.: HP22-1E-PDF

ISSN: 2652-7805

Pub.: 220451

On this page

- Minister's message

- Introduction

- State of dementia in Canada

- Public Health Agency of Canada: Dementia investments

- Advancing dementia prevention

- Priorities for dementia research and innovation

- New directions for dementia research priorities for Canada

- Informing research with lived experience

- Sharing high-quality research results through guidance and training for care providers

- Assessment of dementia guidance available in Canada on treatment and care

- Dementia research efforts across Canada

- Strengthening efforts on quality of life

- Dementia and populations at higher risk

- Conclusion

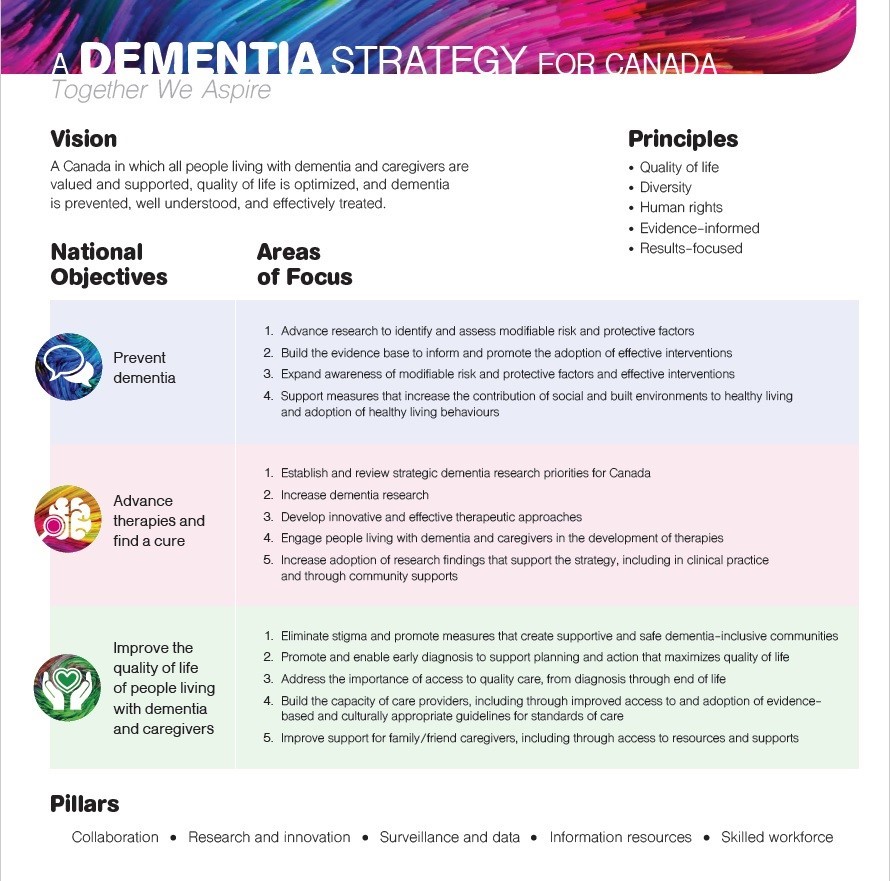

- Appendix A: Overview of the national dementia strategy

- Appendix B: Aspirations for Canada's efforts on dementia from the national dementia strategy

- Appendix C: Map of PHAC investments – project details

- Bibliography

- Endnotes

Minister's message

It is my pleasure to share the 2022 annual report on the national dementia strategy with Canadians. Despite the continued challenges of the past year related to the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change-related emergencies, many organizations and individuals across our country continue to dedicate themselves to efforts that support progress on the strategy's three national objectives. These objectives remain central to the Government of Canada's investments in dementia-related initiatives: to move toward prevention, to advance therapies and find a cure, and to improve the quality of life of people living with dementia and caregivers.

In January 2022, the Government of Canada launched a successful national advertising campaign as part of our national public education initiative on dementia under the Dementia Strategic Fund. Awareness-raising activities focused on reducing stigma by helping Canadians to better understand dementia and to learn how to be supportive when interacting with a person living with this condition. This knowledge is essential to making our communities more inclusive and welcoming. Advertisements ran on television and digital platforms and in newspapers, with the digital ads shown more than 50 million times. Two well-known Canadians who have personal experience with dementia in their families supported the campaign through media interviews, resulting in a combined reach of over 21.5 million impressions across Canada.

Over the past few years, the Government of Canada has continued to develop new dementia-focused programs that support the strategy's national objectives. For example, the Dementia Community Investment has to date supported 21 community-based projects designed to improve the wellbeing of people living with dementia and caregivers and to increase knowledge about the dementia risk factors. These projects also undertake intervention research, enabling assessment of their effectiveness. This program also supports a knowledge hub to share lessons and results and enable collaboration to expand impact. The Dementia Strategic Fund (DSF) has supported 15 awareness raising projects to date across the country which are focused on risk reduction and making communities more dementia-inclusive including through addressing stigma. In this year's report, you will find details about these and other projects that are underway.

Recent public opinion research conducted for the Public Health Agency of Canada is providing greater insight into topics such as the experiences and knowledge of dementia care providers, what quality of life means in the context of dementia, and the knowledge, perceptions, motivations and actions of Canadians related to risk reduction. Some highlights from the results are shared throughout this year's report.

The Government of Canada continues to invest in surveillance projects that gather data to deepen our understanding of dementia in Canada and its impact. Through the Enhanced Dementia Surveillance Initiative, 10 projects have been funded to support new approaches to strengthen data on areas such as when dementia co-exists with other chronic conditions, dementia in long-term care settings, and risk factors. The data and evidence produced by these projects is expected to inform future public health actions to better support those living with dementia and caregivers.

Investment in research and innovation is essential to advancing progress in Canada on the national dementia strategy. In Budget 2022, the Government announced a new $20 million investment for the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to ramp up efforts to learn more about dementia and brain health, to improve treatment and outcomes for persons living with dementia, and to evaluate and address mental health consequences for caregivers and different models of care. Budget 2022 also provides $30 million for the Centre for Aging and Brain Health Innovation to accelerate innovations in brain health and aging. Combined with ongoing investments, Canada is continuing to contribute to global progress on building the research base in dementia as well as innovations that allow research results to support concrete outcomes.

The Government of Canada continues to support efforts to strengthen our health care system, including long-term care, incorporating lessons learned. It is a priority for Canada to be well-prepared for the next public health emergency by strengthening international collaboration and by improving our response systems at home. We also must strengthen preparations for the impacts of climate change, which has been shown to disproportionately impact older adults and people with pre-existing medical conditions that may impact mobility and cognition, such as dementia.

I will close by thanking all those who are focusing their efforts on dementia, whether it is through caring for and supporting those living with the condition, advancing more effective therapies and moving us closer to a cure or expanding risk reduction efforts. Together and every day, across all of our work and investments, we are making progress on the objectives of our national dementia strategy.

Introduction

A variety of efforts across Canada support progress toward the national dementia strategy's objectives on prevention, improved therapies and quality of life. These efforts are made by many different organizations and individuals. They include: community-based programming; many aspects of health care including guidance; research and innovation; data gathering; and, health promotion efforts that reduce the risk of developing dementia. As part of Canada's effort, increased federal investments in dementia-related initiatives are translating into activity that aligns with the strategy's national objectives. The chapter in this report on investments managed by the Public Health Agency of Canada provides a glimpse of projects now underway across the country.

Dementia is a term used to describe symptoms affecting brain function. It may be characterized by a decline in cognitive (thinking) abilities such as: memory; planning; judgement; basic math skills; and awareness of person, place and time. Dementia can also affect language, mood and behaviour, and the ability to maintain activities of daily living. Dementia is not an inevitable part of aging.

Dementia is a chronic and progressive condition that may be caused by neurodegenerative diseases (affecting nerve cells in the brain), vascular diseases (affecting blood vessels like arteries and veins) or injuries. Types of dementia include vascular, Lewy body, frontotemporal, Alzheimer's disease and mixed (a combination of more than one type). In rare instances, dementia may be linked to infectious diseases, including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

Action to pursue the national objectives requires high-quality data and evidence and needs to be informed by lived experience to ensure it responds to notable gaps and reflects Canadians' priorities. This report shares the results of public opinion research Footnote 1 that have deepened knowledge about dementia in Canada, including about quality of life when living with dementia, dementia guidance and Indigenous peoples, and the perspectives and experiences of health care providers Footnote 2 who work with people living with dementia. The report also provides results from a 2022 dementia prevention study and includes key findings from analytical work on dementia guidance. A focus on populations identified as being likely to be at higher risk of developing dementia and/or to face barriers to dementia care continues this year, which includes information about Indigenous peoples and dementia guidance.

This year's report also provides an overview of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people living with dementia as well as on the ability to maintain healthy behaviours associated with a reduced risk of developing dementia. It notes the need to improve the capacity to support people living with dementia during times of climate-change related emergencies such as extreme weather events. People living with dementia are likely to be at higher risk of adverse outcomes in both pandemic situations and climate change-related emergencies and efforts are underway to better understand how to mitigate these impacts and develop necessary resources. This annual report shares information that was current as of June 2022.Footnote 3

State of dementia in Canada

A Dementia Strategy for Canada: Together We Aspire includes ambitious aspirations for the future of dementia in Canada to inspire action from all Canadians to work toward achieving its national objectives. The 2020 annual report to Parliament was the first to present data points selected to shed light on key aspects of the state of dementia in Canada; this year, data points for all three objectives are together in a single chapter to provide insight into movement toward the objectives.

Objective: Prevent dementia

The data points on dementia prevention monitor risk factors among Canadians over time along with the rate of new cases (incidence). Later in the report, the prevalence of risk factors is broken down across provinces and territories. As well, these data points include responses from a 2021 public opinion survey of health care professionals related to their knowledge and access to information about dementia risk reduction. Footnote 4 Health care professionals such as family doctors and nurses have the opportunity to provide guidance related to risk reduction to their patients, making it important to understand their level of knowledge and whether there is adequate access to the tools and resources they need.

Dementia risk factors among Canadians

As rates among Canadians for modifiable dementia risk factors decrease and protective factors increase, the rate of new cases of dementia in Canada may continue to decrease. The data points below outline the age-standardized Footnote 5 prevalence of known dementia risk and protective factors among Canadians over two time points including the most recently available data (see Table 1). This year, one additional risk factor (drinking) is now moving in a better direction, while two risk factors (obesity and diabetes) are still trending in a worse direction. A neutral trend suggests that the risk or protective factor has not changed in a statistically significant way from one time point to the other.

| Dementia risk or protective factor | Percentage (%) of Canadians with factor (Year 1) | Percentage (%) of Canadians with factor (Year 2) | Trend | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of population (aged 18+) that reports heavy drinkingFootnote 7 | 20.7 (2015) | 17.8 (2020) | BetterFootnote 8 | Canadian Community Health Survey, 2020; 2015 (custom analysis) |

| % of population (aged 20+) that reports having less than a high school education | 12.0 (2015) | 8.4 (2020) | Better | Canadian Community Health Survey, 2020; 2015 |

| % of population (aged 20+) with diagnosed hypertension (high blood pressure) | 24.2 (2012–13) | 23.5 (2017–18) | Better | Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System, 2017–18; 2012–13 |

| % of population (aged 18+) that reports being current smokers (daily or occasional) | 18.7 (2015) | 13.4 (2020) | Better | Canadian Community Health Survey, 2020; 2015 |

| % of population (aged 18–79) with elevated blood cholesterol | 18.4 (2014–15) | 14.0 (2018–19) | No significant change | Canadian Health Measures Survey, 2018-2019; 2014-2015 |

| % of population (aged 18–79) who meet physical activity recommendations by accumulating at least 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity each week, in bouts of 10 minutes or moreFootnote 9 | 22.4 (2012–13) | 21.7 (2018–19) |

No significant change | Canadian Health Measures Survey, 2018-2019; 2012-2013 |

| % of population (aged 18–79) that reports obtaining the recommended amount of daily sleep | 61.8 (2009–11) | 64.9 (2014–15) | No significant change | Canadian Health Measures Survey, 2014-2015; 2009-2011 |

| % of population (aged 12+) that reports a "very strong" or "somewhat strong" sense of belonging to their local community (social isolation is a dementia risk factor)Footnote 10 | 68.0 (2015) | 69.7 (2020) | No significant change | Canadian Community Health Survey, 2020; 2015 |

| % of population (aged 20+) with diagnosed stroke | 2.6 (2012–13) | 2.6 (2017–18) | No significant change | Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System, 2017–18; 2012–13 |

| % of population (aged 20+) with diagnosed diabetes | 9.7 (2012–13) | 10.3 (2017–18) | Worse | Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System, 2017–18; 2012–13 |

| % of adults (aged 18–79) that are obeseFootnote 11(self-reported, adjusted BMI) | 25.7 (2015) | 27.8 (2020) | Worse | Canadian Community Health Survey, 2020; 2015 |

Dementia incidence

The age-standardized data shows that the rate of newly diagnosed cases of dementia has decreased between 2008–2009 and 2017–2018. However, as the population of Canadians over the age of 65 grows, the number of Canadians living with dementia is expected to rise. As of 2017–2018, almost 452,000 Canadians aged 65 years and older were living with diagnosed dementia, an increase of almost 10,000 since 2016–2017.Footnote 12

- In 2008–2009 there were 1,576 new cases per 100,000 Canadians aged 65+ years

- In 2017–2018 there were 1,418 new cases per 100,000 Canadians aged 65+ yearsFootnote 13

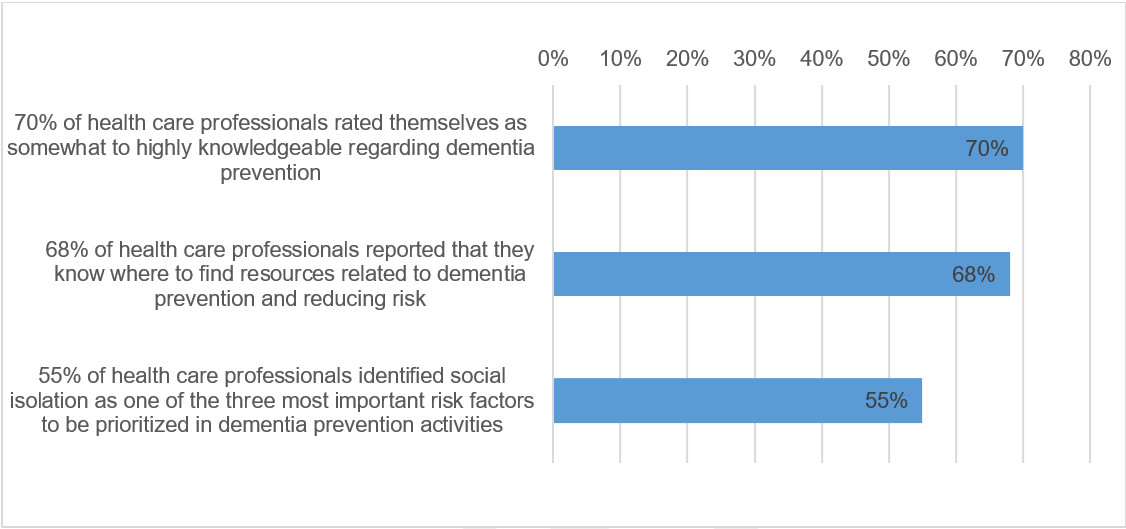

Health care professionals and dementia risk reduction

Health care professionals such as nurses and family doctors are often the first point of contact for people seeking more information on dementia risk reduction. Recent data suggests the majority of health care professionals in Canada consider themselves knowledgeable about dementia prevention and know where to find resources. Drawn from a 2021 survey, these data points provide a sense of the degree of understanding among health care professionals about the factors linked to dementia, their knowledge about resources and their awareness of actions that reduce the risk of dementia.Footnote 4

Overall, health care professionals assess themselves as more knowledgeable regarding dementia risk reduction compared with other categories of care providers such as personal care workers or caregivers.Footnote 14

Figure 1 - Text description

- 70% of health care professionals rated themselves as somewhat to highly knowledgeable regarding dementia prevention

- 68% of health care professionals reported that they know where to find resources related to dementia prevention and reducing risk

- 55% of health care professionals identified social isolation as one of the three most important risk factors to be prioritized in dementia prevention activities

When asked to identify three risk factors to prioritize for prevention, health care professionals most often identified social isolation (55%), physical inactivity (38%) and depression (28%). These three factors, along with several others, are associated with an increased relative risk of dementia, see Table 4a. On a global scale, it has been estimated that people older than 65 who experience social isolation are about 60% more likely to develop dementia than those who do not. Similarly, the increased relative risk for dementia for people older than 65 who are physically inactive is 40%; and those over age 65 who experience depression are 90% more likely to develop dementia compared with those who do not.

Other dementia risk factors identified by health care professionals as being important across the lifespan include a low level of education (26%), alcohol consumption (25%) and traumatic brain injury (23%). Risk factors identified by health care professionals less frequently included hearing loss (12%), diabetes (9%), smoking (9%), hypertension (9%), obesity (7%) and air pollution (1%). (Livingston, 2020)

Objective: Advance therapies and find a cure

Investments in innovation and research help advance improved therapies and deepen understanding of potential causes of dementia. Data points for this national objective track dementia research spending by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the number of dementia research trainees supported by CIHR.

Dementia research spending

The CIHR is Canada's federal funding agency for health research and has 13 Institutes, including the Institute of Aging, that collaborate with partners and researchers to improve health and strengthen the health care system. This data point reports on CIHR's total investment in dementia research, including investigator-initiated research (e.g. funded through the Project Grant competition), research in priority areas (e.g. the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging), and training and career support programs (e.g. fellowships). Canada's investments in research support all three objectives of the national dementia strategy.

| Year | Spending ($) |

|---|---|

| 2020–21 | approximately $49 million |

| 2019–20 | approximately $42 million |

| 2018–19 | approximately $40.8 million |

Dementia research trainees

Supporting and training the next generation of researchers is critical to advancing what we know about dementia. This data point reports on the approximate number of students/trainees engaged in dementia research through CIHR funding. This includes students and fellows who either received a training award (direct trainees), or received a stipend paid through researcher grants (indirect trainees).

| Year | Trainees (number) |

|---|---|

| 2020–21 | 389 |

| 2019–20 | 375 |

| 2018–19 | 359 |

Objective: Improve the quality of life of people living with dementia and caregivers

The data points below report on ratings of quality of life by people living with dementia and dementia caregivers, and on care provider perspectives related to stigma. They include levels of pain, depression and social interaction among people living with dementia receiving home care, as well as a comparison of distress between dementia caregivers and caregivers for those with other conditions.

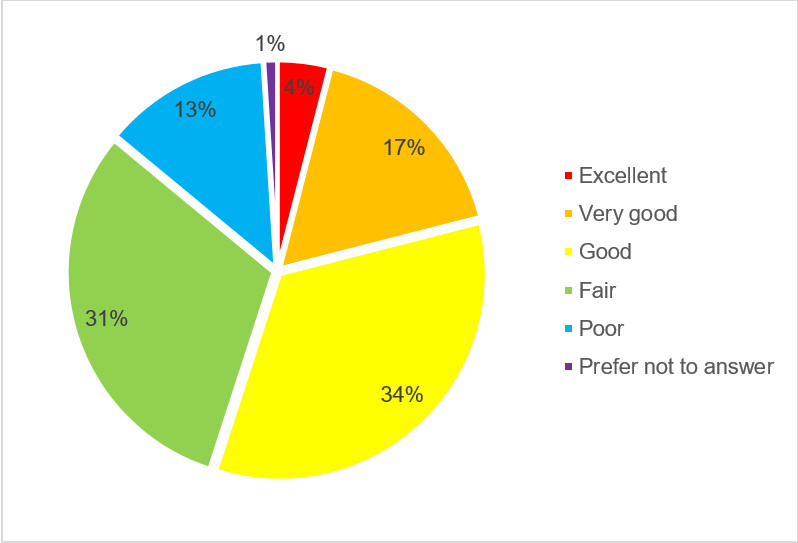

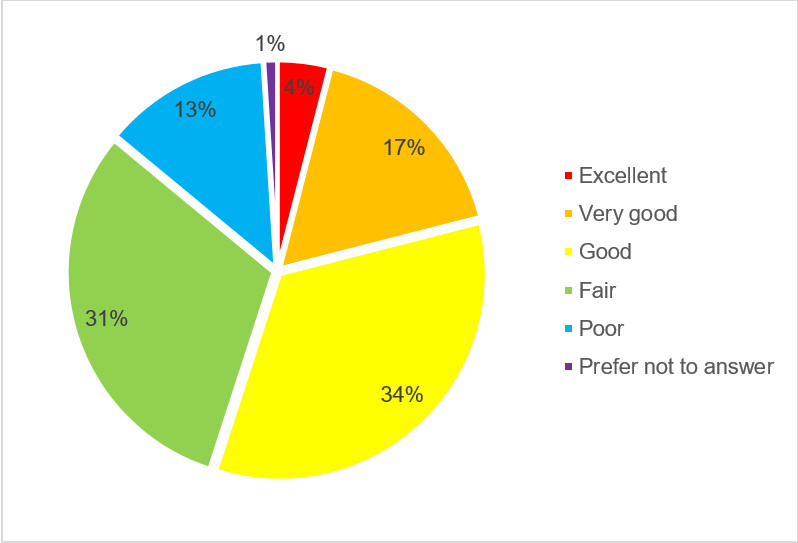

Quality of life rating

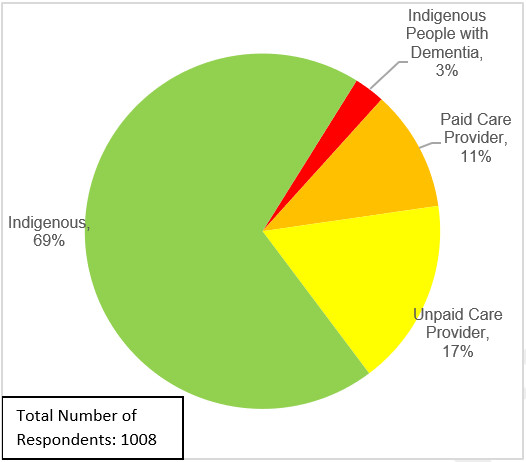

A 2021 public opinion research project focused on deepening understanding of what quality of life means for people living with dementia. Footnote 16 The more than 500 respondents who participated were people living with dementia responding on their own or with the assistance of a caregiver, or current or recent caregivers responding on behalf of a person living with dementia to ensure the results were informed by lived experience.

Just over half of respondents rated quality of life positively. Almost a third responded neutrally, rating quality of life as "fair" and 13% responded that it was poor.

Figure 2 - Text description

- 4% responded with "excellent"

- 17% responded with "very good"

- 34% responded with "good"

- 31% responded with "fair""

- 13% responded with "poor"

- 1% responded with "prefer not to answer"

Care provider perspectives and experiences with stigma related to dementia

The perspectives of care providers Footnote 17 provide insight into the degree of stigma related to dementia in the health care system and the community. Stigma can come from inaccurate assumptions about the capacity of a person diagnosed with dementia and being unaware that symptoms can vary widely by individual and even by day. Care provider perspectives captured below include views about the ability of people living with dementia to work and remain independent.

- 51% of care providers agree that negative stereotypes about dementia are common within the health care system.

- 47% of care providers agree that someone living with dementia can sometimes continue to work for years following diagnosis.

- 73% of care providers agree that someone living with dementia can sometimes continue to live in their own home for years following diagnosis.

Depression, pain, and social interaction among people living with dementia in home care settings and caregiver distress

The 2022 report continues to track data points on depression, pain, and social interaction for people living with dementia receiving home care and on caregiver distress. Footnote 18 They suggest that most people living with dementia receiving home care engaged in activities of interest and had social interactions in 2020–21. However, nearly 34% experienced daily pain and nearly 25% showed signs of depression. Footnote 19 These statistics stayed relatively stable in 2020–21 compared with 2019–20, with the exception of the percentage of people living with dementia receiving home care experiencing reduced social interaction, which increased.Footnote 20

- 21.1% exhibit withdrawal from activities of interest and/or reduced social interaction.

- 24.9% display a potential or actual problem with depression, based on a depression rating scale.

- 33.8% experience daily pain (severe and not severe).

| Data point | Percentage (%) in 2018–19 | Percentage (%) in 2019–20 | Percentage (%) in 2020–21 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exhibiting withdrawal from activities of interest and/or reduced social interaction | 18.3 | 19.1 | 21.1 |

| Displaying a potential or actual problem with depression, based on a depression rating scale | 24 | 24.8 | 24.9 |

| Experiencing daily pain (severe and not severe) | 34.6 | 34.6 | 33.8 |

Caregivers play a key role in supporting the quality of life of people living with dementia. However, this role is often demanding and can lead to distress, impacting physical, mental and emotional health. The data point below from 2020–21 measures distress encountered by caregivers Footnote 21 of people living with dementia who receive home care in contrast to caregivers who provided care to people without dementia who receive home care. Footnote 22 This statistic stayed relatively stable in 2020–21 compared with 2019–20.

- 36.6% of caregivers providing home care to people living with dementia experienced distress, compared with 18.5% of caregivers who provided care for someone without dementia.Footnote 19

Public Health Agency of Canada: Dementia investments

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) directly funds the implementation of key elements of A Dementia Strategy for Canada: Together We Aspire through the Dementia Strategic Fund, the Dementia Community Investment and the Enhanced Dementia Surveillance Initiative.

Dementia Strategic Fund

The Dementia Strategic Fund (DSF) supports efforts designed to pursue the strategy's national objectives on prevention and quality of life. These efforts include awareness-raising projects by organizations across Canada, work to improve access to and use of high-quality dementia guidance and information, and a national public education/awareness campaign.

DSF projects raising awareness about dementia across Canada

As of June 2022, the DSF was supporting 15 projects focused on raising awareness of actions that help prevent dementia, reduce stigma and support communities in becoming more dementia-inclusive. Additional projects are expected to be funded in 2022–23.

Some of the DSF projects encourage Canadians to adopt healthier behaviours to reduce their risk of developing dementia. Through the Luci program, a web-based application, Canadians can learn about dementia risk and protective factors and receive advice from counsellors to engage in a brain-healthy lifestyle. A project with Women's Brain Health Initiative is raising awareness through a brain health campaign that includes an interactive application focused on dementia prevention, alongside a podcast series and educational videos. Another risk reduction project led by S.U.C.C.E.S.S. is developing and delivering a culturally appropriate awareness and educational workshop series in Mandarin, Cantonese, Korean and Farsi to immigrant communities in Metro Vancouver.

Some of the efforts funded by the DSF are focused on dementia-inclusive communities in urban and rural areas, including one project led by the Rural Development Network that is piloting the implementation of dementia-inclusive initiatives and producing guides for rural communities in Alberta. Another led by Simon Fraser University is developing knowledge sharing resources to assess and create dementia-inclusive neighbourhood environments in Metro Vancouver and Prince George, British Columbia. As well, a team led by the Centre collégial d'expertise en gérontologie du Cégep de Drummondville in Quebec is identifying best practices for stigma reduction and dementia-inclusive communities. These best practices will be shared through videos and online training for the general population in St-Jean-sur-Richelieu.

Building capacity for awareness-raising initiatives

For some organizations, capacity building is a necessary first step to dementia awareness raising initiatives. In 2020–21, the Native Women's Association of Canada (NWAC) received funding from PHAC to undertake capacity building. NWAC successfully developed a distinctions-based understanding of the needs, attitudes and behaviours of First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities surrounding stigma and dementia, including the identification of existing community strengths and resources to address dementia.

This additional capacity enabled NWAC to work next toward developing and delivering a strengths-based photobook that illustrates the experiences of Indigenous people living with dementia and a toolkit for people living with dementia and caregivers with culturally specific information on stigma, its effects and tips to overcome it. The photobook and toolkit will be delivered through in-person and virtual workshops/webinars, with the toolkit also being made available in print.

Making a community more dementia-inclusive also means supporting people living with dementia in continuing activities they enjoy. Canada's National Ballet School's Sharing Dance with People with Dementia project, including its Dancer Not Dementia campaign, is increasing opportunities across Canada to participate in dance. Through dance, the project challenges dementia-related stigma while highlighting the creativity, joy, playfulness, community and connection of dancers living with dementia and their caregivers. Similarly, the Art Gallery of Hamilton is building on its Artful Moments program to share best practices and approaches that can be adopted by other museums and galleries to help them become more accessible and welcoming for people living with dementia.

How others interact with and perceive people living with dementia is a core aspect of dementia-inclusive communities. The Open Minds, Open Hearts project led by the Conestoga College Institute of Technology and Advanced Learning is fostering a sense of belonging among college students, people living with dementia and caregivers through guided intergenerational activities in educational institutions in British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec. As well, the Regional Geriatric Program of Toronto is delivering a multi-site education and coaching program on person-centred language to health care professionals working in acute care settings in Ontario to help reduce stigma linked to language, attitudes and practices, including how patients are described in medical records.

Some of the projects funded by the DSF focus on both risk reduction and quality of life for those living with dementia. The Cyber-Seniors intergenerational technology-training program in Ontario and New Brunswick is developing an online educational webinar series, a dementia awareness app and active learning centres where seniors can try out the latest techniques designed to facilitate the adoption of healthier behaviours to reduce the risk of dementia. The ABCs of a Healthy Brain project led by RésoSanté Colombie-Britannique is conducting awareness campaigns and providing information resources to Francophone minorities living in the Yukon, British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan. A project led by the Dementia Society of Ottawa and Renfrew County is enhancing and evaluating an existing dementia-inclusive program that could serve as a model elsewhere in Canada. Activities include an interactive media campaign focused on brain health and dementia risk reduction. The project will use interactive virtual reality to complement existing training and an app to locate and rate dementia-inclusive businesses in the region.

Improving dementia guidance

To improve access to and use of high-quality dementia guidance in Canada, the DSF includes funding for the Dementia Guidelines and Best Practices Initiative. Dementia guidance refers to recommendations and advice in various formats including formal guidelines and best practice statements. A call for proposals for projects was launched in December 2021. As of the preparation of this report, proposals were under review. Applicants were encouraged to focus on populations identified as being likely to be at higher risk and/or facing barriers to equitable dementia care. The themes for the 2021 call were informed by analysis of the quality of dementia guidance available in Canada and engagement with dementia guidance users. Applicants were asked to focus on at least one of these themes:

- Dementia prevention

- Reduce stigma and encourage dementia-inclusive communities

- Person-centred support, communication and care

- Support in times of emergency such as pandemics and natural disasters

- Indigenous-led

The national awareness campaign

A national public education campaign in 2021–22 involved a variety of efforts to reach and educate Canadians about dementia, such as a national advertising campaign and a public relations tour with two public figures as spokespeople. The national advertising campaign, with a focus on reducing stigma, took place in early 2022. This multimedia campaign included a video ad highlighting how to interact in a supportive way with someone living with dementia while out in the community. The advertisements ran from January 17 to March 13 on television, digital platforms and newspapers across Canada. During this period, digital ads were shown 50.4 million times and users clicked on the ads a total of 137,600 times. Results from a survey following the campaign showed that 76% of participants felt the ad helped reduce negative perceptions of people living with dementia, 68% felt it clearly conveyed how to support people who live with dementia, and 63% felt that it provided new information. Average daily visits to the website increased from 79 before the advertising campaign to 2,441 during the advertising period. During the advertising period, there were a total of 136,700 visits to the Canada.ca/dementia website.

Two well-known spokespersons, Jay Ingram and François Morency, supported the campaign through media interviews and other activities. Both spokespeople have family-related experience with dementia. Their speaking tours resulted in 99 interviews and the resulting content appeared in media outlets with a combined reach of over 21.5 million impressions across Canada.

To further raise awareness about dementia in Canada, news articles and a radio spot about risk reduction and healthy lifestyle behaviours as well as an animated video to help reduce stigma have been available to media outlets since January 2021. Between January 2021 and March 2022, these awareness-raising products were integrated into local and national media channels with a reach of 15.5 million impressions across Canada.

Figure 5 - Text description

What does dementia look like?

A friend.

A family member.

A neighbour.

À quoi la démence ressemble-t-elle?

À une amie.

À une maman.

À une voisine.

Dementia might look different than you expect. Learn more at Canada.ca/dementia

La démence n'est peut-être pas comme vous pensez. Apprenez-en plus au Canada.ca/demence

"Addressing misconceptions about dementia is an important step in reducing stigma, which can contribute to social isolation for people living with dementia and can lead to poorer health outcomes. Through initiatives such as the national dementia awareness campaign, we can create more supportive communities where people living with dementia are actively engaged and feel valued and respected as individuals."

— Theresa Tam, Chief Public Health Officer of Canada

As PHAC continues to create a variety of tools to support its efforts to raise awareness about dementia, a video portrait series featuring people living with dementia and their personal stories is being developed as part of a digital engagement campaign. PHAC is also developing a risk reduction campaign for next year.

Dementia Community Investment

PHAC's Dementia Community Investment (DCI) funds community-based projects that develop, test and scale up resources, information, and programs to improve the wellbeing of people living with dementia and caregivers, and to increase knowledge about dementia and its risk and protective factors. All projects funded by the DCI undertake intervention research to assess the effectiveness of the initiative and develop knowledge transfer and sustainability plans to help mobilize and share results.

The DCI has funded 21 community-based projects to date, which have undertaken a variety of initiatives such as developing a model for education and support for caregivers of people living with dementia that reflects participants' cultural heritage, beliefs, values and preferences, as well as promoting inclusive approaches that decrease barriers and increase support for 2SLGBTQI+ people living with dementia and their caregivers.

The DCI funded three new community-based projects from its 2020 solicitation, focused on providing virtual supports to address the impacts of social isolation experienced by people living with dementia and caregivers in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Alzheimer Society of Ontario is adapting its Minds in Motion bilingual programming from in-person to include virtual delivery to better support people living with dementia and caregivers in Ontario. This includes increasing access to those living in rural areas. The eight-week, evidence-based program will be shared with all Alzheimer Societies across Canada. Similarly, McGill University's bilingual Dementia Education Program is being adapted into a virtual platform to educate and support caregivers of people living with dementia, including those living in diverse communities across Montreal and remote communities in Quebec. A third project is adapting an existing virtual intervention from the United Kingdom, the Computer Interactive Reminiscing and Conversation Aid (CIRCA). This intervention provides social engagement and meaningful activities for people living with dementia and caregivers and has been shown to enhance speech and recall from long-term memory while minimizing the impact of challenges related to short-term memory losses. This virtual intervention will reach urban, rural and remote communities across Ontario, Saskatchewan and British Columbia.

Two projects under the DCI have recently been completed. The BC Centre for Palliative Care's project focused on mobilizing and equipping community-based organizations to promote the engagement of people at risk of dementia, people living with dementia, and caregivers in Advance Care Planning (ACP). Tools, resources and training materials were developed to support 28 unique community-based organizations in British Columbia to deliver ACP activities for people living with early stages of dementia and their family and friends. This project involved the training of 131 staff and volunteers, with 85% of public participants reporting increased awareness and knowledge about ACP. SE Health's Research Centre focused on developing tools and processes to build stronger and more effective relationships among people living with dementia, caregivers and care providers. A tool called Our Dementia Journey Journal (ODJJ) was adapted collaboratively with Indigenous, rural and urban communities in British Columbia and Ontario into three versions (English, French and Indigenous) and a mobile app to improve communication, quality of life and relationships throughout the dementia journey.

Knowledge hub spotlight

The DCI also supports a knowledge hub, the Canadian Dementia Learning and Resource Network (CDLRN), led by the Schlegel-UW Research Institute for Aging (RIA). This hub facilitates a community of practice for all DCI projects, enabling them to build capacity, share findings, learn from each other and support collaboration. It is guided by a community advisory committee, which includes people living with dementia and caregivers, to ensure that lived experience is integrated into the work of CDLRN. The CDLRN website offers resources and information about each of the community-based projects.

CDLRN shares key findings from individual projects and broader lessons learned to inform dementia policy and programming across Canada (e.g. through newsletters, working groups, website resources, webinars and workshops). Building these connections will help ensure learnings from DCI investments are shared broadly with partners across Canada to benefit more Canadians living with dementia, caregivers, and the communities in which they live.

Key lessons learned from DCI projects

The CDLRN supports mutual learning among DCI projects and the wider community through sharing at events and annual reporting by DCI projects. Some key themes of lessons learned and best practices have emerged, such as developing tailored approaches in collaboration with diverse communities, as well as understanding how language and stigma can influence recruitment and participation in dementia projects.

- Several DCI projects have highlighted the importance of paying attention to language and culture. Notably, recent findings from an environmental scan (led by COSTI Immigration Services in Toronto) indicate that the ethnocultural and linguistic needs of people living with dementia and caregivers are significantly under-addressed in current dementia care and intervention practices. Incorporating cultural traditions has been highlighted as an effective way to help people living with dementia from diverse cultures feel comfortable and experience positive memories.

- Some DCI projects have also emphasized that the term "dementia" often does not exist in Indigenous languages. Instead, words that describe symptoms associated with dementia are often used. This can be a contributing factor to not accessing health and social services for those in the early stages of dementia. It can also contribute to a lack of Indigenous participation in community-based dementia projects. This underscores the need to raise awareness and to learn about and integrate Indigenous language, concepts, and perspectives in dementia-related projects, specific to each community, as well as the need for Indigenous community members to play a central role in designing, developing and delivering projects.

- Stigma has also been highlighted as an important theme among projects. While addressing ageism and stigma related to dementia is a responsibility of all Canadians, paying attention to privacy and confidentiality when working directly with people living with dementia and caregivers is critical to building trusting relationships with project participants.

- Some best practices have been highlighted for creating inclusive and safe spaces when engaging 2SLGBTQI+ people living with dementia and caregivers, such as leveraging existing 2SLGBTQI+ networks, using inclusive imagery, avoiding gendered language and not making unwarranted assumptions about gender and sexual orientation. It is also helpful to work directly with researchers and partners who identify as 2SLGBTQI+ to improve participation, recognizing that some 2SLGBTQI+ people living with dementia and caregivers may not trust organizations and institutions because of previous experiences of discrimination.

Enhanced Dementia Surveillance Initiative: Strengthening Canada's data

The Enhanced Dementia Surveillance Initiative (EDSI) funds projects that support the surveillance and data pillar of the national dementia strategy (see Appendix A, which provides an overview of the dementia strategy and its pillars). Surveillance and data offer insights into groups within the general population that are more impacted or more at risk to develop dementia. This information is key to guiding prevention efforts. It can also be used to inform the development of policies and programs, health care planning, and service delivery to meet the needs of people living with dementia and their caregivers.

Ten projects have been supported since the start of the EDSI, six of which are highlighted below. Through collaboration between PHAC, provincial and federal partners, as well as academic stakeholders, new approaches are being explored to collect and analyze data on topics such as risk factors for dementia, co-occurrence of dementia and other chronic conditions (i.e. comorbidities), and dementia in long-term care (LTC) settings.

Most of the EDSI projects will ultimately feed into the first and third objectives of the strategy. For example a project led by the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network (Queen's University) resulted in a public access dashboard that presents valuable data on people living with dementia, including demographics, comorbidities, medications, health care use, to support researchers and public health professionals conducting dementia prevention and health care planning activities.

Improving data to support dementia prevention

Many of the ongoing EDSI projects aim to collect, analyze and report data on specific populations living with dementia as well as risk and protective factors. These data will help inform initiatives to prevent dementia or delay its progression.

Improving Indigenous data on dementia (McMaster University)

A first step to help prevent a condition at the population level is to know who develops it and what factors are associated with its development. A team at McMaster University has undertaken an extensive review of the literature and an environmental scan. They highlighted important limitations with existing strategies and data sources which make data-gathering about dementia in Indigenous populations in Canada more difficult. These limitations include incomplete coverage of older Indigenous populations, the lack of culturally safe cognitive assessment tools to appropriately diagnose dementia in Indigenous populations, and barriers to accessing health care. These limitations impact the ability to use existing data sources for surveillance, and this work will set the stage for future surveillance tools to more accurately identify Indigenous peoples living with dementia and inform community-based prevention and treatment.

A comprehensive and holistic approach to dementia surveillance in Canada (University of Waterloo)

A University of Waterloo project has developed a comprehensive and holistic model of dementia to inform surveillance. This model encompasses factors affecting the health and wellbeing of older adults across three levels: individual (e.g. age and sex), social (e.g. social support and family structure), and broader (e.g. public policies). Focus groups that informed the development of this model reflected diverse populations, inclusive of those with different cultural backgrounds, who identify as 2SLGBTQI+, or are from rural or remote areas in eight provinces and one territory. The components of this model will be compared with existing data sources across Canada to identify where new ones are needed to support future prevention efforts as well as treatment and care.

A microsimulation model for dementia projections (Statistics Canada)

In collaboration with PHAC, Statistics Canada is developing a microsimulation model of dementia, Footnote 23 a complex tool that produces long-term projections of the number of new and existing cases of dementia, mortality, risk factors, and associated health care costs among Canadians living with the condition. Projected estimates produced by this tool will enable policy-makers not only to investigate modifiable risk factors, but also to evaluate the impact of potential interventions and policy options. Statistics Canada will be publishing findings from this work, in addition to publicly releasing an application to showcase these projections and the impacts of interventions.

Improving data to support the quality of life of people living with dementia

A series of projects will build on the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (CCDSS), a collaborative network of provincial and territorial surveillance systems that is supported by PHAC and used to produce national surveillance data on dementia. Footnote 24 These projects will leverage the CCDSS data infrastructure to expand and enhance dementia surveillance and generate evidence for public health action aimed at improving the quality of life of people living with dementia.

Using health administrative data to describe comorbidities in people living with dementia (Institute for Clinical and Evaluative Science [IC/ES] in Ontario and three participating provinces)

Comorbidities add to the complexity of care and the overall health impacts associated with dementia. This project, led by IC/ES with the support of British Columbia, Prince Edward Island and Quebec, focuses on developing a common method to identify the presence and the sequence in time of other chronic conditions occurring among people living with dementia (comorbidities). Currently, there is little information on the subject. Early findings from Ontario indicate that adults over the age of 65 with dementia have more comorbidities than those without dementia and that there are important differences in the profile of specific comorbidities by age, sex and setting of care. This project will also assess the association between having multiple comorbidities and subsequent health care use and mortality. These data will help enable optimal management of dementia comorbidities to aid individuals to achieve a higher quality of life by potentially lessening the health impact of these comorbidities.

Collecting data on where people with dementia are living (independently led by three provinces)

This series of projects will examine where people with dementia live, what factors may predict the transition from the community to other settings, and finally, identify the possible data sources to enhance ongoing surveillance of dementia in LTC settings. Each province (British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec) will lead their own work and explore different approaches, given the databases available in their jurisdiction.

People with dementia may live within the community and in LTC settings. In fact, early findings from Ontario (IC/ES) indicate that approximately 80% of older adults (aged 65 years and older) have a history of dementia when admitted to LTC. Currently, routinely collected surveillance data cannot distinguish cases in the community versus cases in LTC, and the extent to which the CCDSS is able to identify all cases of dementia in LTC is not well documented. Early findings from British Columbia suggest that around 80% of those living with dementia in LTC are identified in both the CCDSS and a LTC database (Continuing Care Reporting System Footnote 25) in this jurisdiction, but that a portion of these people remains undetected in the CCDSS. To support jurisdictions where linking to other data sources to improve the identification of dementia cases in LTC is not currently possible, Quebec is piloting a "proxy" approach that will rely only on available information contained in the CCDSS.Footnote 26

Understanding the characteristics of individuals transitioning to LTC and establishing how many people with dementia live in the community compared with LTC is crucial for health system planning. Such data are also important from a quality of life perspective, to ensure appropriate resources are available to ensure optimal quality of life in each setting.

Public Health Agency of Canada investments across Canada

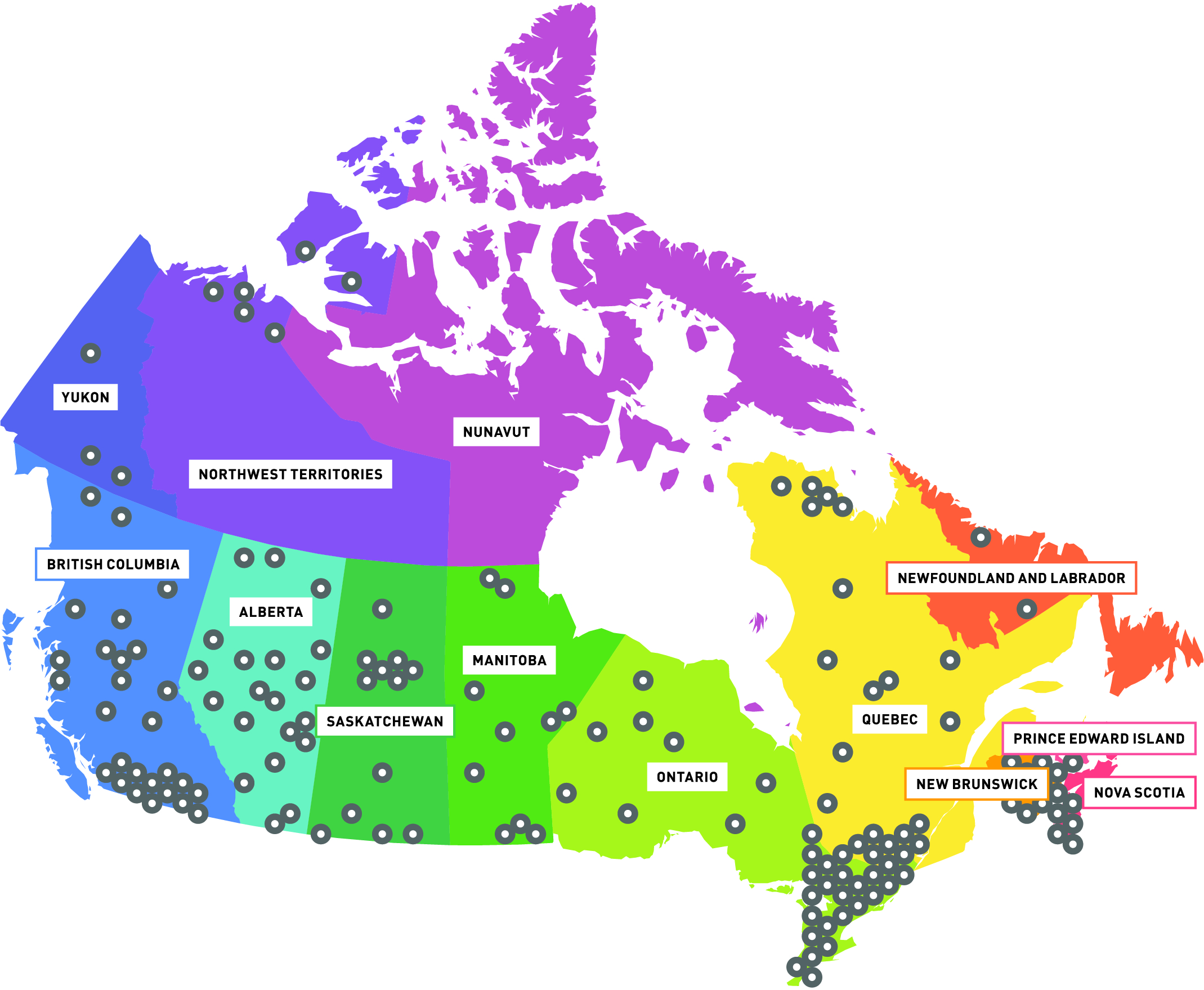

PHAC has funded many dementia-related projects supporting the national dementia strategy across Canada over the last several years. The map in Figure 6 highlights the broad spread of these initiatives supported through the Dementia Strategic Fund (DSF), the Dementia Community Investment (DCI), and the Enhanced Dementia Surveillance Initiative (EDSI). They include provincial and national surveillance projects along with community-based projects. They also include projects that raise awareness of dementia and promote dementia-inclusive communities, and projects that accelerate innovation in aging and brain health. The dots on the map represent areas of activity from 36 projects whose scope is focused on one or more provinces or territories but whose scope is not national. PHAC also supports 11 projects that are national in scope. See Appendix C for a list of projects.

Description: Map of Canada with indicators on provinces/territories where PHAC has invested in a project (numbers seen in table 3 below).

| Total projects funded | National projects | Provincial projects | Number of project sites | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSF | 15 | 3 | 12 | 54 |

| DCI | 22 | 4 | 18 | 68 |

| EDSI | 10 | 4 | 6 | 29 |

| Total | 47 | 11 | 36 | 151 |

| NL | PEI | NS | NB | QC | ON | MB | SK | AB | BC | YT | NWT | NU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSF | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 9 | 16 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| DCI | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 13 | 16 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| EDSI | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 2 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 23 | 31 | 12 | 12 | 20 | 27 | 3 | 6 | 0 |

Advancing dementia prevention

As knowledge about dementia risk factors grows, efforts to reduce risk must be evidence-based to be effective. Examining the rates of these factors across Canada provides insight into where efforts may be most needed. Similarly, a better understanding the views and actions of Canadians about dementia risk and how knowledgeable and equipped care providers are about risk reduction will help to focus efforts and lead to a greater impact.

Dementia risk factors across Canada

Table 4 shows the levels of dementia risk and protective factors in Canada, broken down by province and territory compared with the overall national average. Some factors such as heavy alcohol drinking, education, obesity, smoking, physical activity and social isolation vary widely in some provinces and territories compared with the national average. For example:

- Diabetes prevalence estimates were higher in Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, and Ontario and lower in Alberta, British Columbia, Prince Edward Island, Quebec and the Yukon.

- Heavy alcohol drinking prevalence estimates were higher in Newfoundland and Labrador, the Northwest Territories, and Quebec and lower in Manitoba.

- Less than high school education prevalence estimates were higher in Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Prince Edward Island, and Quebec and lower in Alberta, British Columbia, and Ontario.

- Hypertension prevalence estimates were higher in Alberta, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Saskatchewan and lower in British Columbia, Quebec and the Yukon.

- Obesity prevalence estimates were higher in all the territories, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Saskatchewan and lower in British Columbia.

- Smoking prevalence estimates were higher in all the territories, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Quebec, and Saskatchewan and lower in British Columbia.

- Stroke prevalence estimates were higher in Manitoba, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, and Saskatchewan and lower in Alberta, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Quebec and the Yukon.

The prevalence of some dementia protective factors differ in the following provinces and territories compared with the national average:

- Physical activity prevalence estimates were higher in Alberta, British Columbia, and the Yukon and lower in New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nunavut, Prince Edward Island, and Quebec.

- Strong social wellbeing prevalence estimates were higher in all the territories, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Saskatchewan and lower in Quebec. Social isolation is associated with a higher risk of developing dementia.

| Dementia risk factor | Source | National | AB | BC | MB | NB | NFL | NWT | NS | NU | ON | PEI | QC | SK | YK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of population (aged 20+) with diagnosed diabetes | CCDSS (2017–18) | 10.3 | 9.6 | 10.0 | 11.7 | 11.3 | 11.5 | N/A | 10.5 | N/A | 11.2 | 9.9 | 8.6 | 10.3 | 8.4 |

| % of population (aged 18+) that reports heavy drinkingFootnote 7 | CCHS (2017–18) | 22.9 | 22.2 | 22.5 | 19.2 | 22.7 | 32.1 | 31.7 | 24.5 | 25.5 | 21.4 | 20.2 | 25.3 | 24.4 | 28.7 |

| % of population (aged 20+) that reports having less than a high school education | CCHS (2017–18) | 10.7 | 9.1 | 7.8 | 12.9 | 12.5 | 15.8 | 23.4 | 12.0 | 50.0 | 9.1 | 14.8 | 14.2 | 11.7 | 13.1 |

| % of population (aged 20+) with diagnosed hypertension (high blood pressure) | CCDSS (2017–18) | 23.5 | 24.7 | 22.3 | 27.4 | 27.4 | 30.6 | N/A | 26.5 | N/A | 24.0 | 24.4 | 20.5 | 25.4 | 21.1 |

| % of population (aged 18–79) that are obeseFootnote 11 (self-reported, adjusted BMI) | CCHS (2017–18) | 26.9 | 29.4 | 22.9 | 30.0 | 36.1 | 39.6 | 41.7 | 33.9 | 37.8 | 26.0 | 33.9 | 25.4 | 35.1 | 33.8 |

| % of population (aged 18+) that reports being current smokers (daily or occasional) | CCHS (2017–18) | 17.1 | 17.1 | 13.4 | 17.7 | 16.2 | 22.2 | 35.8 | 19.3 | 59.5 | 16.6 | 18.4 | 18.7 | 21.5 | 21.6 |

| % of population (aged 20+) with diagnosed stroke | CCDSS (2017–18) | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 2.1 | N/A | 2.0 | N/A | 2.7 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 1.9 |

Note: For tables 4a and 4b, provincial and territorial differences observed with the CCDSS should be interpreted with caution. Even though differences are statistically significant, methodological differences may explain the patterns observed in addition to actual differences in the health status of the populations. For instance, differences in detection and treatment practices, as well as differences in data coding, remuneration models and shadow billing practices likely play a role in the patterns observed.

| Dementia protective factor | Source | National | AB | BC | MB | NB | NFL | NWT | NS | NU | ON | PEI | QC | SK | YK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of population (aged 18+) that report accumulating at least 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity each week, in bouts of 10 minutes or moreFootnote 9 | CCHS (2017–18) | 56.8 | 58.8 | 65.7 | 54.4 | 52.2 | 51.5 | 57.1 | 56.0 | 45.9 | 55.8 | 52.1 | 53.8 | 57.0 | 69.6 |

| % of population (aged 12+) that reports a "very strong" or "somewhat strong" sense of belonging to their local community (social isolation is a dementia risk factor)Footnote 10 | CCHS (2017–18) | 68.9 | 69.8 | 70.5 | 73.6 | 75.5 | 77.4 | 81.4 | 71.8 | 80.8 | 70.7 | 73.4 | 61.4 | 74.4 | 80.2 |

The Weston Family Foundation awarded a $12-million research grant to the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) hosted at McMaster University, for a new initiative that will shed light on the many factors that influence brain health as we age, including lifestyle and the human microbiome. The human microbiome is the collection of microorganisms (for example, the bacteria, bacteriophage, fungi, protozoa and viruses) that live inside and on the human body.

The Healthy Brains, Healthy Aging Initiative will feature a cohort of 6,000 research participants currently enrolled in the CLSA. It marks the first time a national study of aging in Canada has introduced both brain imaging and microbiome analyses to investigate cognitive aging in the population over time. The goal of the six-year Healthy Brains, Healthy Aging Initiative is to enhance the CLSA platform with longitudinal data from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and microbiome analyses of the gut, to help researchers examine how diverse lifestyle, medical, psychosocial, economic and environmental factors as well as changes in the microbiome correlate with healthy aging outcomes. This data will be critical to the future development of screening and prevention strategies that promote brain health for aging Canadians.

Building our understanding of dementia risk reduction in Canada

Perceptions of dementia risk and action to reduce risk among Canadians

Public opinion research undertaken by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) in 2022 provides greater insight into the views and actions of Canadians related to dementia risk reduction. Footnote 28 These results suggest that over half of Canadians (52%) would rate their personal risk of developing dementia as moderate to high. Individuals belonging to groups identified as likely to be at higher risk rate their own risk as moderate to high slightly more often than all respondents, with Indigenous individuals at 57% and 2SLGBTQI+ individuals at 61% for example, while those with existing health conditions are at 61%. Common reasons among respondents for rating their risk as moderate to high include having family members who have or have had dementia (61%), lack of exercise (41%), or having one or more ongoing health conditions (34%).

Almost one in three Canadians (32%) rate their personal risk of developing dementia as low. Common reasons among respondents for rating their risk of developing dementia as low (32%) include challenging their brain regularly (72%), no one in their family having or have had dementia (64%) and maintaining healthy eating habits (58%). Common risk factors identified by all respondents to be likely to increase their own risk include sleep disruption (41%), loneliness/social isolation (42%), and depression (41%).

Despite more than half of Canadians rating their personal dementia risk moderate or higher, more than two-thirds (69%) of all respondents have not taken any steps to intentionally reduce that risk in the last 12 months. However, many did report healthy behaviours associated with a reduced risk such as challenging their brain (68%), eating healthy foods (62%) and being physically active (54%), although less than half of respondents reported being socially active (44%). About 60% feel they would like to be able to or need to do more to reduce their dementia risk. Of those (27%) who indicated they would not do more to reduce their risk, reasons include not knowing enough about what actions to take (33%), feeling it would not have an impact (13%), lacking the time to take steps (12%), and having health challenges that prevent them from taking steps (11%).Footnote 28

| Risk factor | Relative increased risk of developing dementia compared with someone without this risk factor |

|---|---|

| Early life (under 45 years old) | |

| Lower levels of education | 60% |

| Midlife (45 to 65 years old) | |

| Hearing loss | 90% |

| Traumatic brain injury | 80% |

| Hypertension | 60% |

| Obesity | 60% |

| Alcohol use (over 21 units per week) | 20% |

| Later life (over 65 years of age) | |

| Depression | 90% |

| Smoking | 60% |

| Social isolation | 60% |

| Diabetes | 50% |

| Physical inactivity | 40% |

| Air pollution | 10% |

Care providers and risk reduction

Health care providers may have the opportunity in their work to provide guidance about dementia risk factors. A 2021 survey of 1593 care providers Footnote 31 who interact with people living with dementia asked which three risk factors should be prioritized. Care providers most often selected well-recognized risk factors although there was some variation among different groups of care providers. Among all respondents, social isolation was the most common risk factor identified (59%). It was also highlighted as a risk factor by most of the care providers who participated in the individual interviews that were another part of this public opinion research project.

In the 2021 survey, health care professionals such as family doctors and nurses Footnote 32 identified social isolation (55%), physical inactivity (38%) and depression (28%) most often as risk factors to prioritize. These three factors have been identified as associated with dementia (see Table 5).Footnote 29 It is important to note that alternatively dementia may be a risk factor for depression; as well dementia and depression may have similar risk factors. Health care professionals were more likely to identify obesity (7%), smoking (9%), diabetes (9%) and alcohol consumption (25%) as risk factors to prioritize compared with other dementia care providers.

Depression was often selected by developmental service workers and personal care workers (41% each) as a priority risk factor while caregivers were more likely to identify social isolation (66%), physical inactivity (51%), hearing loss (17%) and hypertension (11%) compared with other care providers. Developmental service workers were most likely to identify traumatic brain injury (31%). Only 1% of health care professionals and personal care workers identified air pollution Footnote 33 as a risk factor for prioritization.

Availability and use of guidance related to dementia risk reduction

Another recent PHAC study gathered insights from dementia guidance users and those otherwise familiar with this guidance Footnote 34 through a questionnaire, roundtables and interviews. Most roundtable and interview participants Footnote 35 indicated in self-reporting that there is a lack of awareness among health care professionals and the public related to risk reduction and a need for more education. Among questionnaire participants, 60% were familiar with or use dementia guidance on risk reduction. Almost all of this guidance was related to healthy habits (e.g. diet, physical activity and cognitive stimulation) (88%), reducing risk factors like smoking and sleep disorders (83%), and managing chronic conditions linked to dementia (70%). Participants in approximately half of the roundtables indicated that more public education and resources are needed on this topic. Conducting public health campaigns, providing education in schools, and having an accessible educational toolkit and supportive resources were noted as ways to address gaps and barriers, and improve awareness, access and training regarding dementia risk reduction guidance

The study of dementia guidance users found that health care professionals need access to practical and efficient on-the-job training and quick reference information in one convenient location (such as fact sheets or an app), both of which need to include case examples and clear recommendations relevant to their practice. Education was highlighted as a key component to successfully disseminating guidance across Canada for all audiences, including the general public. Dementia guidance users also noted that it is important that evidence-based information is available in plain language, provided in multiple formats, located all in one spot, and tailored to various contexts and audiences. These strategies were noted as particularly important for dementia guidance related to prevention.

To inform effective action to reduce the risk of dementia, high-quality evidence-based guidance must be easy to access. A 2021 survey focused on care providers found that almost half of caregivers (48%), who are often family and friends, reported that they would not know where to find resources related to dementia risk reduction.Footnote 4 About one-quarter of health care professionals (23%) and personal care workers (27%) reported a similar lack of knowledge. The majority of developmental service workers (60%) and personal care workers (52%) felt they could use more preparation or training in reducing dementia risk. Almost half (46%) of health care professionals, who may be the most likely to need this information in their day-to-day work, felt the same.

As part of a recent analysis of existing dementia guidance in Canada, expert panel members suggested that additional efforts to improve knowledge about risk reduction could include knowledge translation activities Footnote 36 aimed at educating care providers about new and existing guidance to support the adoption and consistency of guidance use across Canada. These activities could take place in schools and through continued education and awareness raising efforts targeted at professionals throughout their careers.

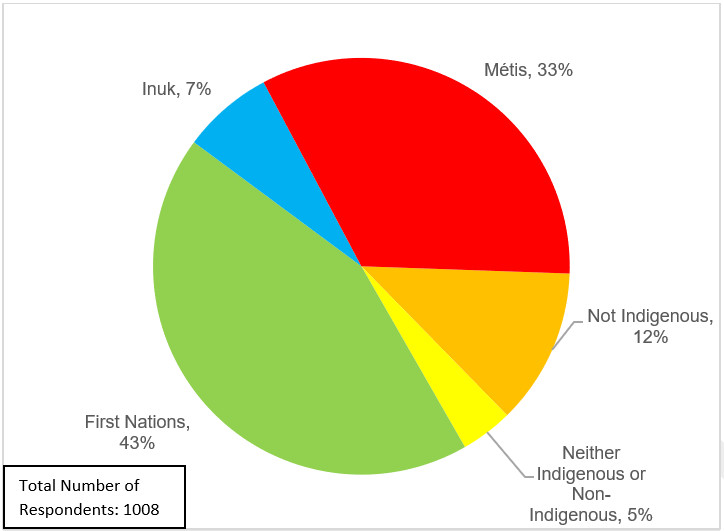

Indigenous perspectives on dementia risk reduction

Indigenous individuals in Canada have been identified as likely to be at higher risk for developing dementia and facing barriers to care. In a 2021 survey that gathered Indigenous perspectives on dementia guidance, 34% of Indigenous participants who were not living with dementia and had not cared for someone living with dementia said they were somewhat to very knowledgeable about ways to reduce the risk. Footnote 37 Approximately three in five (62%) said they were a little to not at all knowledgeable about ways to reduce the risk. A third (39%) said that they have taken steps to reduce their own risk. Of those who had not taken any steps, the most common barrier identified to reducing risk was being unaware of what steps to take (57%). These respondents less frequently said the reason they have not taken any steps is because they do not consider themselves at risk (10%), they are not sure it will make a difference (8%), and they are not personally concerned about developing dementia (7%). Respondents to this survey commonly identified a diet lacking in healthy foods, social isolation, a lack of physical activity and harmful alcohol use as factors that come to mind that could increase their chances of developing dementia.

Care providers to an Indigenous person living with dementia more often than not said they were relatively knowledgeable about ways to reduce the risk of developing dementia with 51% and 73% of unpaid and paid care providers respectively identifying as somewhat to very knowledgeable. Almost half of unpaid care providers (45%) and 27% of paid care providers said they were a little to not at all knowledgeable about ways to reduce the risk of developing dementia. Over two-thirds of both paid and unpaid care providers (68%) agreed that there were gaps or barriers in dementia risk reduction recommendations and advice for Indigenous populations.

When looking for dementia guidance, recommendations or advice online, nearly two-thirds (64%) of Indigenous respondents who were not living with dementia and had not provided care to someone living with dementia said they would be likely or very likely to refer to advocacy organization websites and over half (53%) would likely or very likely go to health care expert websites. Slightly less than half of this segment would be likely or very likely to use federal government websites (49%), provincial or territorial websites (43%), or regional or local Indigenous health authority websites (41%). Most unpaid and paid care providers are likely to very likely to use advocacy organizations (67% and 74% respectively) and health care expert websites (51% and 68% respectively).

Dementia and the genetic link

In Canada and globally, genetic factors are known to play one of two roles in the emergence of dementia. The less common role is when genetic inheritance determines a dementia outcome. The more common role is when genetic factors elevate the risk of developing a dementia-causing disease. In the latter case, genetic risk is one of many dementia risk factors, including several that can be modified through healthy lifestyles and behaviours. Recent studies have shown that taking action on some of these lifestyle risk factors can have a notable impact on dementia risk reduction. Footnote 38, Footnote 39, Footnote 40 A study in 2019 exploring the link between genetic risk and lifestyle found that overall only 1.23% of those with a high genetic risk eventually developed dementia compared with 0.63% with a low genetic risk. Footnote 41 However, those with a high genetic risk and a lower level of healthy behaviours were almost three times as likely to develop dementia. In other words, while genetics may heighten the risk of developing dementia, evidence suggests that acting to reduce other risk factors can still have an impact on lowering risk.Footnote 29 Regardless of one's genetic risk, having a healthy lifestyle such as not smoking, regular physical activity, healthy diet, and moderating alcohol consumption along with a good level of cognitive reserve (i.e. early life education, mid-life substantive work complexity, late life leisure activities, and late life social networks) is associated with a lower risk of developing dementia. Footnote 42, Footnote 43

PHAC's 2022 public opinion research on dementia prevention found that genetics is the risk factor most likely to come to mind for respondents when asked what may increase the likelihood of developing dementia (34%).Footnote 28 Further, when asked about their own perceived level of risk and the reasons for that perception, genetics was commonly mentioned. Among the 52% of respondents who felt their own risk of developing dementia is moderate to high, having family members who have or have had dementia was given as a reason by 61%. Among the 32% of respondents who felt their risk of developing dementia is low, almost two-thirds (64%) selected having no one in their family having or having had dementia as a reason. Similarly, a 2021 study found that almost one in four Indigenous respondents (23%) identified genetics as one of the first three risk factors that come to mind when asked about what increases their chances of developing dementia.Footnote 37

While genetic risk was a common reason identified by participants as informing their rating of their own personal risk in a 2022 survey,Footnote 28 studies suggest that it is not a direct cause in most cases of dementia.

- Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, accounting for 60-80% of all dementia cases in Canada. Footnote 44 It is estimated that between 15–25% of the general population carries at least one copy of the APOE ɛ4 gene (which increases the chance of developing AD three to fourfold) Footnote 45 and 2–3% are estimated to carry two copies of that gene (which further increases the risk of developing AD nine to fifteenfold). Footnote 46, Footnote 47

- The second most common form of dementia is vascular dementia which accounts for 15-20% of all cases in North America. Footnote 48 This form is typically not inherited. However, underlying conditions, such as high blood pressure or diabetes, may be inherited along with genes that increase the risk of conditions that lead to vascular dementia, like heart disease or stroke.Footnote 29

- Other types of dementia are much rarer in Canada. For these types, genetic risk may play a larger role. However, the likelihood of them being inherited is never more than 50% (rarer types of dementia such as Huntington's disease can be up to 50%),Footnote 38 behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia is 40%, Footnote 49 dementia with Lewy bodies is 10%, Footnote 50 semantic dementia is less than 5% Footnote 51 and young-onset AD is less than 1%.Footnote 52

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dementia risk factors among Canadians

Research is exploring how the COVID-19 pandemic has reduced opportunities for exercise and social activity and increased feelings of loneliness, isolation, anxiety and stress that have challenged Canadians' abilities to maintain positive mental health. Alcohol use, which is linked to depression, has been identified as a common coping mechanism during the COVID-19 pandemic. A lack of physical activity, social isolation, harmful levels of alcohol consumption and depression are risk factors for developing dementia.

Physical activity

Physical activity in children and youth can have life-long benefits by helping to maintain a healthy weight, develop cardiovascular fitness, and reduce the risk of developing chronic conditions in later life, such as dementia. Footnote 53, Footnote 54, Footnote 55 In the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, physical activity levels declined among some populations and increased in others. As of April 2020, 4.8% of children aged 5–11 and 0.6% of youth aged 12–17 were found to be meeting Canada's 24-hour movement guidelines. This represents a significant drop in physical activity levels compared with pre-pandemic, when the proportion of Canadian children and youth aged 5–17 who met physical activity recommendations had been between 12.7% and 17.1%. Footnote 56 As of October 2020, during the second COVID-19 wave, the number of children aged 5–11 who met the guidelines dropped further to 4.5%. Footnote 57 For youth aged 12–17, 37.2% met the Canadian physical activity recommendations in fall 2020, compared with 50.8% of youth in fall 2018.Footnote 58

Physical activity recommendations

Children aged 5–11

- At least one hour of moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity daily

- Vigorous intensity activities at least three days per week

- Activities that strengthen muscle and bone at least three days per week (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019a)

Youth aged 12–17

- An hour every day of moderate to vigorous intensity activity

- Vigorous intensity activities at least three days a week

- Activities that build muscles and bones at least three days a week (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019b)

There were no significant changes in physical activity noted among adults aged 18–64 overall, though results varied depending on whether individuals were working from home.Footnote 58 While those working at home due to the COVID-19 pandemic appeared to be able to transition to other forms of physical activity, such as at-home workouts or recreational walks, total physical activity minutes remained less than those who did not work from home (40.7 minutes per day compared with 49.8 minutes per day). For adults aged 65 and over, physical activity levels increased by almost 5% in 2020 compared with 2018 (from 35.4% to 40.3%).

Social isolation

Some Canadians have reported a sense of loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly younger Canadians. Data on loneliness among Canadians aged 15 and older during the COVID-19 pandemic (collected for the first time between August and September 2021) indicates that 23% of youth aged 15–24 experienced loneliness, compared with 15% of those between the ages of 25 and 34. Footnote 59 Women were particularly susceptible, with almost a third (29%) of women aged 15–24 experiencing loneliness compared with 18% of men aged 15–24. Among those aged 25–34, 16% of women reported feelings of loneliness compared with 15% of men. Adults aged 65–75 were least likely to report experiences of loneliness (9%), followed by 14% of those aged 75 and older.

Alcohol consumption

Researchers have been exploring links between social isolation and alcohol consumption as there is evidence of alcohol consumption being used during the COVID-19 pandemic as a coping strategy for feelings of loneliness, isolation, stress, and boredom. Footnote 60, Footnote 61, Footnote 62 Excessive alcohol use in mid-life is a risk factor for developing dementia.

About one-quarter (24%) of Canadians reported increased alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic, with stress, boredom and loneliness contributing to the increase, while 22% said their consumption had decreased.Footnote 60 CIHR's COVID-19 and Mental Health (CMH) Initiative found that more Canadians (especially those aged 40–49, those reporting increased anxiety, and those reporting feelings of loneliness) reported an increase in alcohol use (23%) than those that reported a decrease in alcohol use (11%). Footnote 63 The number of Canadians reporting no change in alcohol use was slightly higher, at 65%. As well, the number of hospital stays for harm caused by substances such as alcohol, opioids, stimulants and cannabis between March and September 2020 increased by 4,000 stays across Canada, compared with the same period in 2019. Footnote 64 The relationship between stress, loneliness and increased alcohol use was also noted among Canadians living in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, where research indicates that about 12% of respondents reported more frequent drinking during the COVID-19 pandemic, and 25%–40% reported increased stress, loneliness and hopelessness.Footnote 65

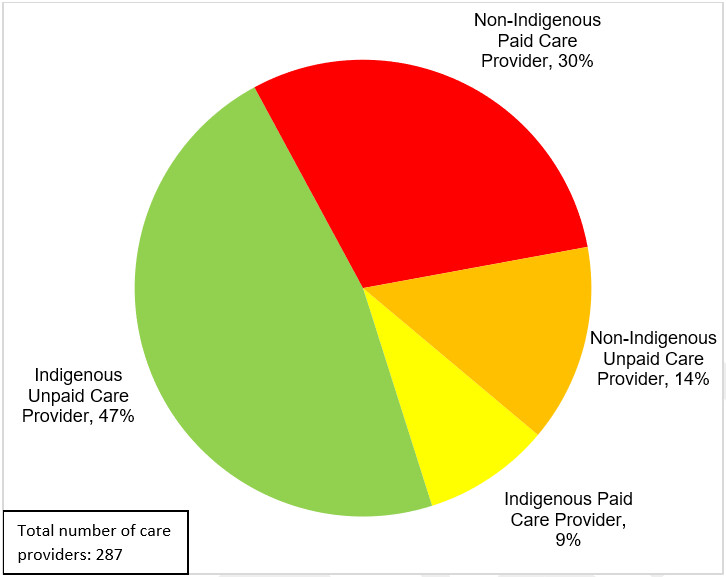

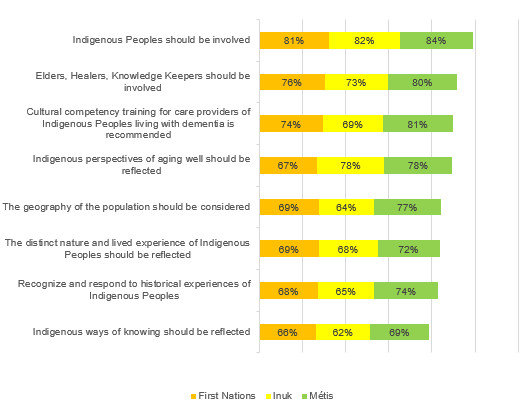

Depression