A Dementia Strategy for Canada: Together We Aspire

Download the alternative format

(3.8 MB, 110 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2019-06-17

Related topics

A summary of the strategy, A Dementia Strategy for Canada: Together We Aspire: In Brief, is also available.

Table of contents

- Minister's message

- Executive summary

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: National objective: Prevent dementia

- 2.1 Advance research to identify and assess modifiable risk and protective factors

- 2.2 Build the evidence base to inform and promote the adoption of effective interventions

- 2.3 Expand awareness of modifiable risk and protective factors and effective interventions

- 2.4 Support measures that increase the contribution of social and built environments to healthy living and adoption of healthy living behaviours

- Chapter 3: National objective: Advance therapies and find a cure

- 3.1 Establish and review strategic dementia research priorities for Canada

- 3.2 Increase dementia research

- 3.3 Develop innovative and effective therapeutic approaches

- 3.4 Engage people living with dementia and caregivers in the development of therapies

- 3.5 Increase adoption of research findings that support the strategy, including in clinical practice and through community supports

- Chapter 4: National objective: Improve the quality of life of people living with dementia and caregivers

- 4.1 Eliminate stigma and promote measures that create supportive and safe dementia-inclusive communities

- 4.2 Promote and enable early diagnosis to support planning and action that maximizes quality of life

- 4.3 Address the importance of access to quality care, from diagnosis through end of life

- 4.4 Build the capacity of care providers, including through improved access to and adoption of evidence-based and culturally appropriate guidelines for standards of care

- 4.5 Improve support for family/friend caregivers, including through access to resources and supports

- Chapter 5: Pillars

- Chapter 6: Focus on higher-risk and equitable care

- Chapter 7: Moving towards implementation

- Appendices

- Appendix A: Federal government dementia-related initiatives

- Appendix B: Overview of provincial and territorial dementia-related initiatives

- Appendix C: Examples of non-governmental, not-for-profit, and international organizations working on dementia-related initiatives

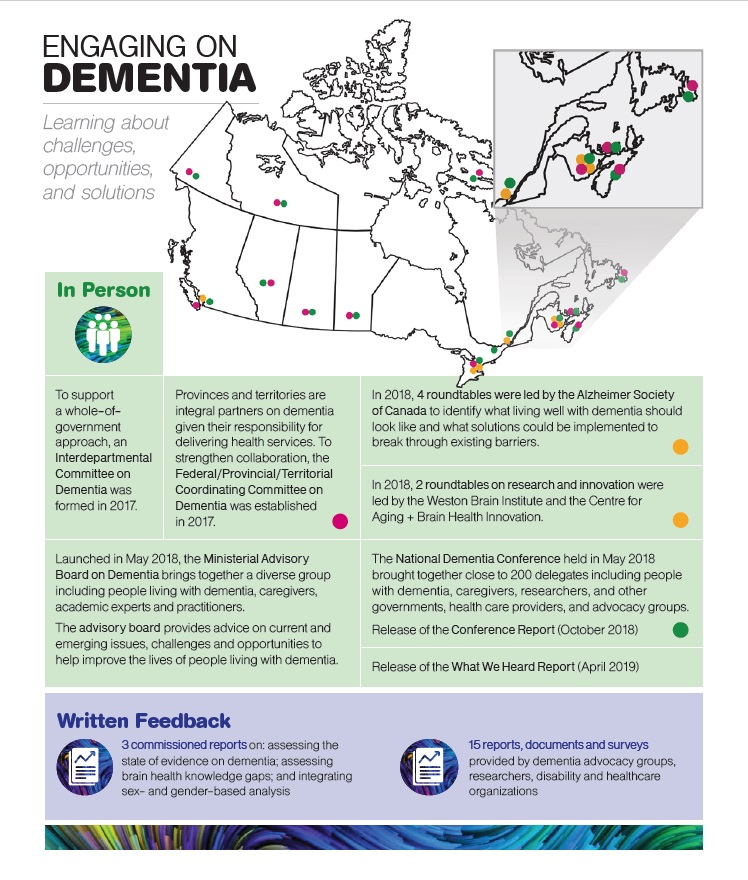

- Appendix D: Engaging on dementia: learning about challenges, opportunities and solutions

- Appendix E: Glossary

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

Minister's message

I am pleased to be sharing with you Canada's first national strategy on dementia. Developing and funding this strategy has been a priority for the Government of Canada, but it is also a deeply personal priority. My first experience with dementia was during my time as a social worker; now I have a very different experience with dementia care following my mother's diagnosis. I know very well the impact that dementia can have on those living with this condition, their family members and caregivers.

Dementia has a significant and growing impact in Canada. We know that there are more than 419,000 Canadians aged 65 and older diagnosed with dementia, but this is only part of the story. This number does not capture those under the age of 65 with a diagnosis of dementia and those who, possibly due to stigma or other barriers, remain undiagnosed. This strategy is not just for those living with or caring for someone with dementia. It is a strategy for all Canadians. There is a growing body of evidence that healthy living is key to preventing dementia. Whether as a caregiver to a family member or friend, as a person living with dementia or in interactions at work or community involvement, many of us will encounter dementia at some point in our daily lives.

The release of this strategy marks a key milestone in our efforts to create a Canada where all people living with dementia and caregivers are valued and supported, and experience an optimal quality of life and where dementia is prevented, effectively treated and better understood. Canada now joins those in the international community who have already developed national dementia strategies, supporting the first target in the WHO Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia (2017-2025).

At the opening of the National Dementia Conference in May 2018, I encouraged participants to dream big when sharing their thoughts and advice with us about the focus for our national dementia strategy. I believe we have achieved a strategy with an aspirational vision that will inspire and motivate us to work together towards our national objectives.

As we move forward, we will continue to collaborate with all those interested in addressing the challenges of dementia, including our partners in other governments, people living with dementia, caregivers, advocacy groups, health care providers and researchers. This strategy has been designed to evolve over time so that we can integrate new evidence and priorities. The Government of Canada will report to Parliament each year on the effectiveness of this strategy. New federal investments of $70 million over 5 years will also help to ensure we make meaningful progress on the national objectives of this strategy.

Many people have helped us get to this point. I would like to extend a thank you to all the individuals and organizations who shared their experiences and advice as well as their hopes and priorities for the strategy. Aging does not cause dementia, but advanced age increases risk. In her role as Minister of Seniors, Minister Filomena Tassi has been a strong supporter of the development of this national dementia strategy. Her conversations with seniors and caregivers are reflected in the strategy. I would like to thank Minister Tassi for her leadership in making dementia a priority in Canada by highlighting issues associated with this condition. I would also like to thank our provincial and territorial partners who have been generous in sharing the lessons learned from their work on dementia and who have welcomed the opportunity to collaborate. Lastly, I would especially like to thank the members of the Ministerial Advisory Board on Dementia. Led by co-chairs Pauline Tardif and Dr. William Reichman, members volunteered their time and energy to ensure that we got this strategy right. The many hours that these members dedicated to reviewing the draft strategy during its development and attending meetings to share their knowledge and expertise with us is something for which I am personally very grateful and have enriched the strategy.

The Honourable Ginette Petitpas Taylor, P.C., M.P.

Minister of Health

Executive summary

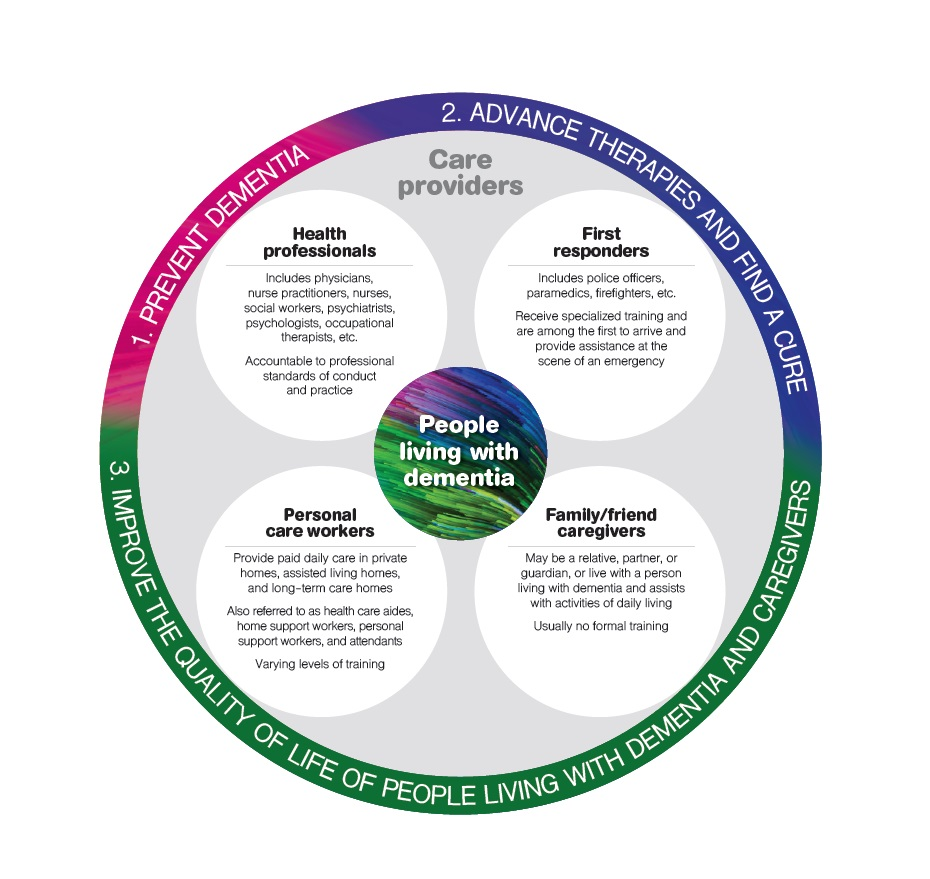

Canada's first national dementia strategy sets out a vision for the future and identifies common principles and national objectives to help guide actions by all levels of government, non-governmental organizations, communities, families and individuals. In developing the strategy, we sought at all times to ensure that people living with dementia and the family and friends who provide care to them were at the heart of these efforts.

Dementia is a term used to describe symptoms affecting the brain that include a decline in cognitive abilities such as memory; awareness of person, place, and time; language; basic math skills; judgement; and planning. Mood and behavior may also change as a result of this decline. Dementia is a progressive condition that, over time, can reduce the ability to independently maintain activities of daily life.

The National Strategy for Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias Act (the Act) was passed in June 2017 and followed a comprehensive report on dementia from the Senate in 2016. This Act requires the federal Minister of Health to develop a national dementia strategy, host a national conference and establish a Ministerial Advisory Board on Dementia.

The Minister held a national conference on dementia in May 2018, which brought together a diverse group of Canadians to identify and discuss challenges related to dementia, identify opportunities for collaboration and action, and share ideas for a national strategy. Participants at the conference included people living with dementia, caregivers, advocacy groups, health professionals, researchers and representatives from provincial and territorial governments.

Discussions were also held in March 2018 at 4 stakeholder roundtables across the country organized by the Alzheimer Society of Canada. Two further roundtables were held in Toronto to specifically discuss research and innovation. The roundtable on research was facilitated by the Weston Brain Institute and was attended primarily by researchers. The roundtable on innovation was facilitated by the Centre for Aging + Brain Health Innovation and attended by a diverse group of stakeholders. The strategy has also been informed by the guidance of the Ministerial Advisory Board, as well as ongoing engagement with provincial and territorial governments and other federal organizations. Footnote 1

The vision for this strategy is bold and reflects the aspirations of the many individuals and organizations who contributed to its development. The actions undertaken to achieve the strategy's national objectives may evolve over time, but every action will bring Canada closer to the vision of a Canada in which all people living with dementia and caregivers are valued and supported, quality of life is optimized, and dementia is prevented, well understood, and effectively treated.

Key to achieving this vision are 5 principles setting out values to guide the implementation of efforts in support of the national objectives and their areas of focus. In implementing the strategy, governments, non-governmental organizations, community organizations and others working on dementia should:

- Prioritize quality of life for people living with dementia and caregivers;

- Respect and value diversity to ensure an inclusive approach, with a focus on those most at risk or with distinct needs;

- Respect the human rights of people living with dementia to support their autonomy and dignity;

- Engage in evidence-informed decision making, taking a broad approach to gathering and sharing best available knowledge and data; and

- Maintain a results-focused approach to tracking progress, including evaluating and adjusting actions as needed.

Building on the vision and guided by these principles, the strategy identifies 3 national objectives:

- Prevent dementia

- Advance therapies and find a cure

- Improve the quality of life of people living with dementia and caregivers

Areas of focus are set out for each of these national objectives, to guide efforts toward meaningful progress.

Finally, the strategy identifies 5 underlying pillars that are essential for implementation, for upholding the principles and achieving the national objectives.

- Collaboration — Achieving progress on the strategy is a shared responsibility among governments, researchers, community organizations, people living with dementia, caregivers and many others

- Research and innovation — Promoting research and innovation will address knowledge gaps and develop therapies that will improve the quality of life of people with dementia and caregivers, and move us towards a cure

- Surveillance and data — Enhanced surveillance and data will help us to understand the scope of dementia in Canada, and focus our efforts and resources where they are most needed and will be most effective

- Information resources — The development of culturally appropriate and culturally safe information resources on dementia will facilitate the work of care providers to provide quality care and will help all Canadians to better understand dementia

- Skilled workforce — Having a sufficient and skilled workforce will support dementia research efforts and provide evidence-informed care, which will improve the quality of life of people living with dementia and caregivers

The strategy places emphasis on those groups who are at a higher risk of dementia as well as those who face barriers to equitable care. These groups include but are not limited to Indigenous peoples, individuals with intellectual disabilities, individuals with existing health issues such as hypertension and type 2 diabetes, older adults, women, ethnic and cultural minority communities, LGBTQ2 individuals, official language minority communities, rural and remote communities, and those with young onset dementia.

The final chapter of the strategy outlines next steps toward implementation including the development of indicators, identification of opportunities for focused collaboration between partners, and reporting. It concludes with the recognition that advancement of the strategy will require the collective action of many organizations and individuals, as well as the flexibility to evolve and respond to new ideas and emerging needs over time. The Government of Canada will report annually on the effectiveness of this strategy, as required by the Act, beginning in 2019.

Chapter 1: Introduction

A Dementia Strategy for Canada

Canada's first national dementia strategy places people living with dementia and the family and friends who provide care to them at its centre. Footnote 2 It provides a focused vision and direction for advancing dementia prevention, care and support in Canada.

Building on existing efforts — including provincial and territorial dementia-related initiatives as well as federal investments in dementia — the strategy sets out 3 national objectives. The implementation of this strategy relies on collaboration toward common goals across federal, provincial, territorial and local governments, as well as with many other organizations and individuals.

Text box 1: What is dementia?

Dementia is an umbrella term used to describe a set of symptoms affecting brain function that are caused by neurodegenerative and vascular diseases or injuries. It is characterized by a decline in cognitive abilities. These abilities include: memory; awareness of person, place, and time; language, basic math skills; judgement; and planning. Dementia can also affect mood and behaviour.

As a chronic and progressive condition, dementia can significantly interfere with the ability to maintain activities of daily living (PDF), such as eating, bathing, toileting and dressing.

Alzheimer's disease, vascular disease and other types of disease all contribute to dementia. Other common types of dementia include Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia and mixed dementias. In rare instances, dementia may be linked to infectious diseases, including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

This strategy includes a commitment to raise awareness of dementia across Canada. This is important, not only to help reduce stigma, but also because the strategy is for all people living in Canada regardless of whether they are currently affected by dementia. There is growing persuasive scientific evidence that healthy living from an early age may prevent or delay the onset of dementia. This strategy promotes healthy lifestyle choices and includes an emphasis on populations that are more at risk of developing dementia and those that may be facing barriers to equitable care. More information about these populations can be found in Chapter 6.

All Canadians can contribute to supporting the quality of life of those living with dementia and caregivers by better understanding dementia and helping to eliminate stigma. While most people receiving a diagnosis of dementia are in later life, dementia also affects individuals at a much younger age. The strategy will encourage dementia-inclusive communities that support people living with dementia and caregivers in staying involved in their communities and at work for as long as possible.

The strategy identifies gaps in knowledge about preventing dementia to help focus efforts by researchers and funders both nationally and internationally. There is also a need to advance efforts that improve the ability to identify, test and share effective therapies that support healthy living after a diagnosis. The strategy will encourage initiatives that broaden access to and adoption of those therapies, including in rural and remote communities and by making them culturally safe and culturally appropriate.

While the national objectives are deliberately broad in scope so that priorities and areas of focus can evolve as new knowledge and new issues emerge, the principles and pillars of the strategy are designed to be constant over time to help guide and support that evolution. The strategy will be implemented through activities such as those undertaken by governments, researchers and other partners, and its impact will be tracked through annual reports to Parliament. Canada's strategy also responds to the call for action in the World Health Organization's (WHO) Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia (2017-2025) and its designation of dementia as a public health priority. The scope of the Canadian strategy responds to all 7 action areas identified by the WHO plan and aligns with its cross-cutting principles.

Impact of dementia on Canadians

Dementia has a significant and growing impact on Canadians. In 2015–16, more than 419,000 Canadians (6.9%) aged 65 years and older were living with diagnosed dementia. Footnote 3 As this number does not include those under age 65 who may have a young onset diagnosis nor those that have not been diagnosed, the true picture of dementia in Canada may be somewhat larger. See Text box 2 for some key statistics on dementia in Canada.

Text box 2: Key statistics on dementia in Canada

- More than 419,000: the number of Canadians aged 65 years of age and older who are living with diagnosed dementia

- 78,600: the number of new cases of dementia in Canada diagnosed per year among people aged 65 years of age and older

- 63%: the percentage of those aged 65 years of age and older living with diagnosed dementia in Canada who are women

- 9: the approximate number of seniors who are diagnosed with dementia every hour in Canada

- 26 hours: the average number of hours that family/friend caregivers spend per week supporting a person with dementia

- $8.3 billion: the total health care costs and out-of-pocket caregiver costs of dementia in Canada in 2011

- $16.6 billion: the projected total health care costs and out-of-pocket caregiver costs of dementia in Canada by 2031

While dementia is not an inevitable part of aging, age is the most important risk factor. As a result, with a growing and aging population, the number of Canadians living with dementia is expected to increase in future decades.Footnote 4 Estimates suggest 50 million people are living with dementia worldwide.Footnote 5 As the proportion of the population aged 65 years and older continues to rise, countries around the world are expected to experience similar increases in the number of individuals living with dementia.Footnote 6

Of those aged 65 years and older living with diagnosed dementia in Canada in 2015–16, almost two-thirds (63%) were women.Footnote 7 Women have higher rates of Alzheimer's disease, while men have higher rates of other types of dementia, such as frontotemporal and Lewy body dementias.Footnote 8 The number of women in long-term care with dementia also greatly exceeds the number of men, which is only partially due to longer life expectancy among women.Footnote 9

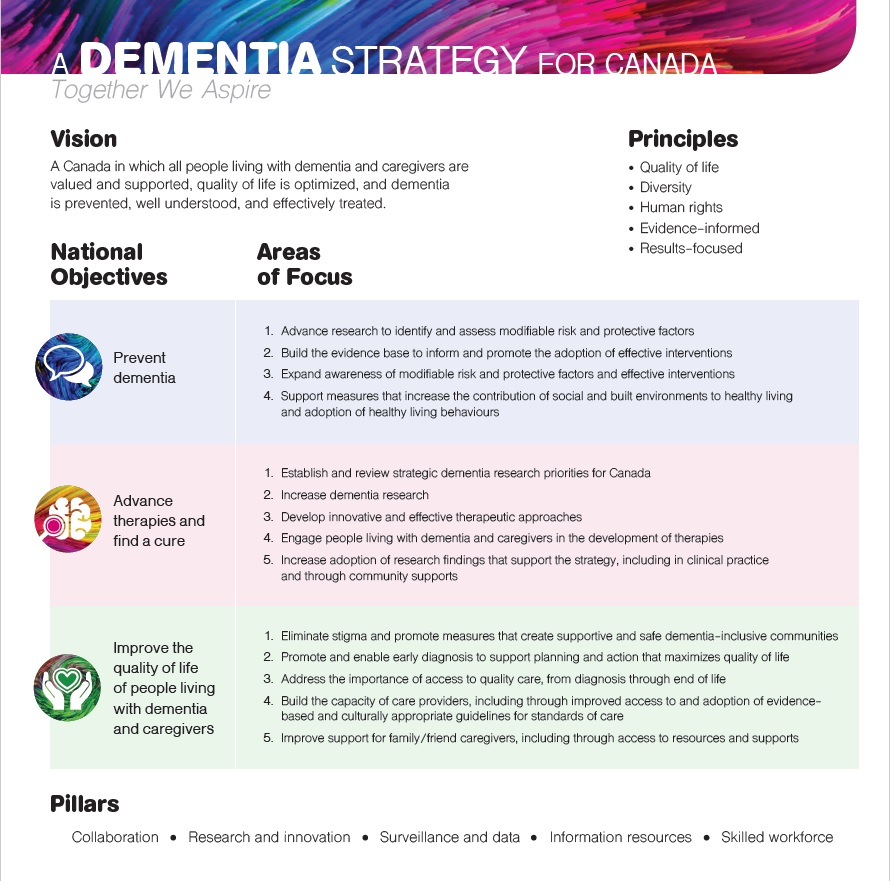

A wide range of care providers are involved in meeting the needs of people living with dementia. These needs can fluctuate as the condition progresses. Care providers include but are not limited to physicians, personal care workers, nurses, and first responders. They also include family and friend caregivers. The majority of these caregivers are female, most commonly female intimate partners and daughters.Footnote 10 On average, family and friend caregivers spend 20 hours a week caring for and supporting a person living with dementia.Footnote 11

The impact of dementia on the health care system is significant. Currently there is no cure or effective therapy to stop the progression of dementia. Direct health care costs for people living with dementia have been estimated to be 3 times higher than for those without dementia. It has been projected that the total annual health care costs and out-of-pocket caregiver costs for Canadians with dementia will double from $8.3 billion in 2011 to $16.6 billion by 2031, while indirect economic costs due to working-age death and disability are projected to increase from $0.6 billion to $0.7 billion during the same period.Footnote 12 Globally, dementia is also a major cause of disability and dependency among older adults.Footnote 13

A dialogue with Canadians

Since the passage of the National Strategy for Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias Act in June 2017 that formally put the development of the first national dementia strategy for Canada in motion, the Government of Canada has heard from many individuals and organizations.

This strategy reflects the valuable input and guidance received from a broad range of stakeholders. It has been informed by consultations and engagement with people living with dementia, caregivers, researchers, health professionals and other care providers, and representatives of dementia-related advocacy groups from across Canada. The strategy also reflects advice resulting from the work of the Ministerial Advisory Board on Dementia, regular meetings with provincial and territorial officials, and the engagement of officials from federal organizations whose activities fall within the scope of the strategy.

The National Dementia Conference in May 2018 was a key step in developing the strategy. It brought together close to 200 participants, including people living with dementia and caregivers, to identify challenges, solutions, and opportunities related to dementia. Prior to the conference, 4 roundtables were organized by the Alzheimer Society of Canada and held across the country in March 2018, in Vancouver, Montreal, Saint John, and Fredericton. They brought together nearly 160 participants, including 15 people living with dementia, to discuss what living well with dementia looks like. Two additional roundtables on research and innovation were facilitated by the Weston Brain Institute and the Centre for Aging + Brain Health Innovation. These roundtables brought together researchers, people living with dementia, advocacy groups, health care professionals, and provincial and territorial representatives. They provided feedback on how innovation can best support living well with dementia and possible ways to break through existing barriers, and identified priorities for dementia research and innovation.

The Public Health Agency of Canada commissioned expert reports to inform the strategy, including an assessment by the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences of the state and strength of the evidence on dementia and a review of sex, gender, diversity and equity considerations related to dementia. Development of the strategy also considered the findings of several other reports and surveys related to dementia, including submissions received from organizations.

The Government of Canada recognizes that Indigenous communities and individuals have distinct dementia experiences and distinct needs. Engagement with Indigenous organizations, communities and governments will continue as the strategy is implemented to better understand these needs and facilitate Indigenous-led efforts to improve the quality of life for people living with dementia and caregivers in those communities.

The Government of Canada was challenged to be bold and ambitious with Canada's first national dementia strategy. We heard that the strategy should encompass both the importance of immediate efforts to improve the quality of life of people living with dementia and caregivers, as well as longer-term efforts to prevent dementia, advance therapies and find a cure. As the strategy moves into implementation, the Government of Canada will continue collaborating with all those committed to making progress on the vision and national objectives. This dialogue will ensure the strategy evolves as new priorities emerge.

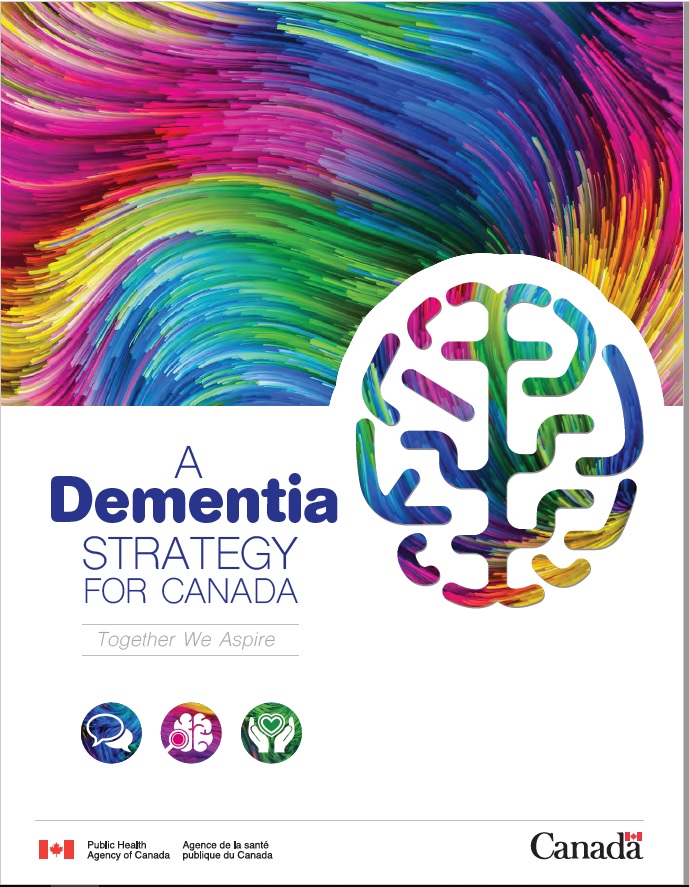

Figure 1: Canada's dementia strategy

Figure 1 - Text description

Canada's dementia strategy

This image is a visual depiction of the core elements of the strategy.

The title of the strategy appears at the top "A dementia strategy for Canada: Together We Aspire".

Below this the Vision is stated which is "A Canada in which all people living with dementia and caregivers are valued and supported, quality of life is optimized, and dementia is prevented, well understood, and effectively treated".

Next to the vision the principles are displayed in a bulleted list: Quality of life, Diversity, Human rights, Evidence-informed, and Results-focused.

Below the principles are a table with a row for each of the National Objectives and their corresponding Areas of Focus.

In the second row is the objective of "Advance therapies and find a cure".

- Advance research to identify and assess modifiable risk and protective factors,

- Build the evidence base to inform and promote the adoption of effective interventions,

- Expand awareness of modifiable risk and protective factors and effective interventions,

- Support measures that increase the contribution of social and built environments to healthy living and adoption of healthy living behaviours.

In the second row is the objective of "Advance therapies and find a cure".

The corresponding Areas of Focus are:

- Establish and review strategic dementia research priorities for Canada,

- Increase dementia research,

- Develop innovative and effective therapeutic approaches,

- Engage people living with dementia and dementia caregivers in the development of therapies,

- Increase adoption of research findings that support the strategy, including in clinical practice and through community supports.

In the third row is the objective of "Improve the quality of life of people living with dementia and caregivers". The corresponding Areas of Focus are:

- Eliminate stigma and promote measures that create supportive and safe dementia-inclusive communities,

- Promote and enable early diagnosis to support planning and action that maximizes quality of life,

- Address the importance of access to quality care, from diagnosis through end of life,

- Build the capacity of care providers, including through improved access to and adoption of evidence-based and culturally appropriate guidelines for standards of care,

- Improve support for family/friend caregivers, including through access to resources and supports.

At the bottom of the image (underneath the National Objectives/Areas of Focus table), the Pillars of the strategy are listed in one line separated by dots. The pillars are:

- Collaboration

- Research

- Innovation

- Surveillance and data

- Information resources

- Skilled workforce

Vision: Setting a clear path forward

The vision we hope to achieve is a Canada in which all people living with dementia and caregivers are valued and supported, quality of life is optimized, and dementia is prevented, well understood and effectively treated.

Achieving the best quality of life for people living with dementia and caregivers is at the centre of the strategy. The vision prioritizes the need to support and value people living with dementia to make it easier to live well for as long as possible, to deepen the understanding of dementia, and to raise awareness of dementia and of stigmatizing behaviours. It also recognizes the importance of improving therapies and investing in efforts towards prevention and a cure, including through research.

Principles

Five principles set out values to direct and guide action on dementia in Canada. These principles are intended to inform all elements of the strategy, including when evaluating options for policies and programs with a direct impact on dementia-related issues. This strategy calls on all governments in Canada and other stakeholders to consider and support these principles through their own work on dementia.

Prioritizing quality of life: Actions taken to implement the strategy prioritize the wellbeing of people living with dementia and caregivers.

- Living well for as long as possible: It is widely recognized and accepted that greater understanding and better access to supports Footnote 14 and tools will enable living well with dementia.

- Access to quality care and supports: The availability and quality of care and supports helps people live as well as possible each day and make choices that are important to them.

- Supportive communities: Community leaders and the general public are knowledgeable and committed to initiatives that make their communities more dementia-inclusive, including by raising awareness and making it easier for people living with dementia to participate.

Respect and value diversity: Actions and initiatives undertaken by all partners maintain an inclusive approach, with special consideration given to those most at risk or with distinct needs in support of greater health equity.

- Inclusive: All forms of diversity are considered in developing and implementing initiatives.

- Most at risk: Initiatives are tailored as needed and when appropriate to reach those most at risk in order to support health equity.

- Distinct Indigenous needs: The distinct needs of Indigenous communities and individuals are identified by Indigenous peoples and recognized by others. Indigenous communities and organizations are supported in addressing dementia in culturally appropriate and culturally safe ways, including through a distinctions-based approach that recognizes differences among First Nations, Inuit and Métis cultures.

- Community involvement: Community input is gathered to support community-based and community-led initiatives, and local capacity building is leveraged to reflect the diversity within Canada.

Respect human rights: Actions taken under the strategy respect the human rights of those living with dementia and reflect and reinforce Canada's domestic and international commitments to human rights.

- Human rights lens: A person-centred approach that focuses on respecting and preserving an individual's rights, autonomy and dignity in alignment with Canada's human rights commitments.

- Inclusion: Steps are taken to enable the participation of people living with dementia.

- Respects choice: The rights of individuals living with dementia to make their own decisions are broadly understood and facilitated.

- Hears the voices of those living with dementia: Actively including and consulting those living with dementia on matters that affect their quality of life.

- Caregiver perspectives: Consideration is given to the needs of the family and friends who care for people living with dementia.

Evidence-informed: Partners implementing the strategy engage in evidence-informed decision making, taking a broad approach to gathering and sharing the best available knowledge and data.

- Best evidence: Identification, creation and access to the best available research findings, data and knowledge.

- All forms of knowledge: A broad approach is taken when gathering evidence, including scientific data, traditional knowledge and the experiences of those living with dementia and of those caring for people living with dementia.

- Working together: Collaboration is used to build evidence and knowledge, including sharing research results.

- Informed decision-making: Policies and programs are informed by a thorough and rigorous examination of the evidence.

Results-focused: Partners maintain a results-focused approach to implementing the strategy and tracking progress, including evaluating and adjusting actions as needed.

- Initiatives that support reporting: Implementation activities are clearly linked to the areas of focus and national objectives, and are designed to support reporting on results.

- Enabling evaluation: Data and evidence are gathered to support evaluation and inform future efforts, both on activities undertaken and their impacts.

- Measurement: Indicators are identified and developed to support tracking of progress.

- Accountability: Annual reports to Parliament demonstrate accountability by sharing the results gathered from monitoring and evaluation.

- Flexibility to evolve: A flexible approach enables priorities to evolve as needed through continued dialogue, ongoing collaboration, and consideration of new evidence and information.

National objectives

Each of the 3 national objectives provides a broad scope for initiatives and activities. Under each national objective, areas of focus are identified where greater efforts are required to make progress on dementia in Canada. The 3 national objectives are:

- Prevent dementia

- Advance therapies and find a cure

- Improve the quality of life of people living with dementia and caregivers

Pillars

Five cross-cutting pillars are essential for implementation of the strategy.

Collaboration

The implementation of the strategy depends on continuing to build on key partnerships and collaboration on dementia, including with people living with dementia, caregivers, and communities. All governments in Canada and many stakeholders, including care providers, community and social service organizations, researchers and advocacy groups have a role to play in contributing to achievement of the strategy's national objectives.

Research and innovation

High quality, collaborative research and innovation are essential to the implementation of the strategy. While Canada is making significant investments in dementia research and advancing our understanding of dementia, there is still much to be learned and tested about prevention, new and better approaches to therapies, and supporting the quality of life of those living with dementia and caregivers. To continue and build Canada's contribution to dementia research, it is important to recruit young researchers.

Canada remains committed to its national and international collaborations and to supporting research towards a cure. It will continue to evaluate research findings and promote adoption of the most effective approaches as best practices across the country. Putting research findings into practice requires awareness and understanding, along with acceptance and sharing. Effort is required to reduce barriers for the adoption of research findings.

Surveillance and data

Optimizing dementia surveillance will provide a more accurate picture of the impact of dementia in Canada. This will give us insight into groups within the general population that are more affected and more at risk, and will support better identification of their health needs and those of caregivers. High quality surveillance data helps ensure that activities taken to support the strategy are well-informed and appropriately targeted. It also enables evaluation of progress resulting from activities undertaken in support of the strategy.

Information resources

Valuable information resources about dementia are available both in Canada and around the world. Efforts to improve public access to information about dementia, best practices in care and prevention, and social supports along with other key resources will broaden awareness and understanding of dementia and support greater health equity. Innovative ways to improve access to information will be explored, along with options for providing information resources in multiple languages and making them culturally appropriate.

Skilled workforce

Canada's dementia workforce is diverse. It includes researchers who are exploring the development of therapies and seeking a cure, as well as health professionals and other care providers who interact with people living with dementia and caregivers. Having a sufficient workforce that is well-equipped to pursue dementia research and provide quality dementia care is essential.

As our population grows and ages and the expected number of people living with dementia increases, Canada is likely to need more care providers. Post-secondary institutions will need to provide programs that include more dementia training for care providers and practitioners across the care pathway, to ensure the workforce is informed about dementia from diagnosis through to end of life. It is critical that these care providers have the necessary knowledge and skills to provide quality care.

Chapter 2: National objective: Prevent dementia

Developing a better understanding of how dementia can be prevented and sharing information about how Canadians can reduce their risk of developing dementia or delay its onset is critical to keeping Canadians healthy and improving quality of life.

There are individual health behaviours and other factors that can reduce or increase our chances of developing dementia (see Text box 3). For example, protective factors include healthy eating and physical activity, while smoking and hypertension may put Canadians at higher risk of developing dementia.

Text box 3: Risk factors for dementia

While there is currently no clear consensus, some evidence suggests that about one third of dementia cases could be prevented by addressing 9 risk factors:

- lower levels of early life education (up to 12 years of age)

- midlife hypertension (45-65 years of age)

- obesity

- hearing loss

- smoking in later life (over age 65)

- depression

- physical inactivity

- diabetes

- social isolation*

While certain factors may be more closely associated with specific stages of life, such as early life education, midlife hypertension and smoking in later life, reducing individual risk may be beneficial at any age when it comes to prevention. For people living with dementia, taking action focused on these factors could improve quality of life and reduce the risk of developing other chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes.Footnote 15

The environments we live in, including both social and built environments, can significantly influence our overall health and wellbeing. Dementia prevention efforts include sharing knowledge about the links between the design of our environments and dementia risk factors. The social environment is the space in which we engage in social activity within our communities, including recreation and education. Footnote 16 The built environment refers to the physical environment around us, including buildings, roads, green spaces and public transit — the places where we live, learn, work and play. Footnote 17 The natural environment, from plants and animals to water and air, also plays an important role in our lives, particularly for those who live in rural and remote communities across Canada. In these communities, geography may amplify both positive and negative impacts of the social and built environment on healthy living.

To support progress on preventing dementia, the strategy encourages researchers to continue working to better understand the factors already associated with developing dementia and assess additional factors that may be linked, such as traumatic brain injury, gum disease and inadequate sleep. Footnote 18 By furthering our knowledge of how these risk factors are linked to dementia, we can move beyond a list of risk factors to more effectively manage those risks and reduce their impact. This work will build a solid foundation for developing ways to prevent dementia.

Studies also suggest that delaying the onset of dementia could significantly reduce the total number of dementia cases in subsequent years. It is estimated that delaying onset by a few years could reduce the number of individuals with dementia by up to one third a few decades later. Footnote 19, Footnote 20 For those at increased risk of developing dementia, delaying its onset may also improve quality of life and reduce the personal, family and societal costs of care. Footnote 21 Some developed countries have already begun to report reduced incidence rates of dementia that appear linked to healthy living and higher education levels. Footnote 22 Canadian data suggests a possible decline in incidence rates of diagnosed dementia, Footnote 23 consistent with trends observed in other developed countries including the United States and the United Kingdom.Footnote 24

Four areas of focus will support preventing dementia:

- 2.1 Advance research to identify and assess modifiable risk and protective factors

- 2.2 Build the evidence base to inform and promote the adoption of effective interventions

- 2.3 Expand awareness of modifiable risk and protective factors and effective interventions

- 2.4 Support measures that increase the contribution of social and built environments to healthy living and adoption of healthy living behaviours

Area of focus 2.1: Advance research to identify and assess modifiable risk and protective factors

Advancing work to better understand which factors are linked to the increased risk of developing dementia, how important a factor is in comparison to other factors, and how these factors influence each other will build a foundation for preventing dementia. Although age is the strongest known risk factor for the onset of dementia, dementia is not an inevitable consequence of aging.

Research has shown a relationship between cognitive impairment (problems with memory, learning, thinking and judgement greater than normal age-related changes) and lifestyle risk factors common to several chronic conditions. Unhealthy lifestyle behaviours linked with conditions such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and hypertension also appear to be associated with a higher risk of developing dementia. As a result, lifestyle changes focused on healthy living behaviours, like healthy eating and regular physical activity (protective factors) may reduce the number of dementia cases in the future. As well, an increase in unhealthy behaviours such as smoking and harmful alcohol use Footnote 25 (risk factors) could be expected to increase the risk of dementia.Footnote 26

Evidence also suggests that building the brain's ability to resist, offset and cope with damage or decline may contribute to prevention or delay the onset of dementia. Higher levels of education are associated with lower rates of dementia in later life, possibly due to greater flexibility and ability for the brain to adapt or overcome challenges (known as cognitive reserve).Footnote 27

Activities to advance research to identify and assess modifiable risk and protective factors may include:

- Promoting research that deepens evidence related to a more accurate assessment of risk and protective factors already linked to dementia

- Encouraging research on and identification of additional potential risk and protective factors to move toward a more comprehensive understanding of dementia

| Current status | Aspiration |

|---|---|

| Incomplete understanding of risk and protective factors linked with dementia, with some factors not yet identified and insufficient evidence on the link between factors and dementia. | A complete understanding of the risk and protective factors linked to dementia, their impacts and interactions. |

Area of focus 2.2: Build the evidence base to inform and promote the adoption of effective interventions

Given emerging evidence about factors that affect the risk of developing dementia, building the evidence base about effective interventions is an essential step in increasing the success of prevention efforts. Recent research has shown that interventions that promote healthy living can reduce the risk of developing dementia. Footnote 28 Healthy living includes embracing actions that maintain health such as physical activity and healthy eating, and avoiding behaviours that may harm health such as smoking.

Building on the work that is already underway, more research is needed to gather evidence on and increase understanding of interventions focused on these factors to determine which are effective in preventing dementia, and in what dose and what combination. Some evidence from prevention research is encouraging, but further research on larger and more diverse populations over longer timeframes is required. Footnote 29 Work is also needed to design interventions that are culturally safe and culturally appropriate to increase the adoption of healthy behaviours. Interventions need to be adapted in ways that best address the unique needs of individuals, particularly within higher-risk populations and for those facing barriers to care.

Interventions that address a number of factors at the same time, rather than those with a sole focus, could potentially be a more effective way to reduce the risk of developing dementia and to prevent chronic diseases. An example of encouraging research on prevention is the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER). Footnote 30 It examined the effectiveness of changing lifestyle factors such as nutrition, physical activity, cognitive training, social activities and monitoring vascular risk for those at risk of developing dementia. Interaction of these types of lifestyle factors is showing promising results of reduced risk of cognitive decline. This study has since expanded to the United States, China, Singapore and Australia.

Activities to build the evidence base to inform and promote the adoption of effective interventions may include:

- Investing in research to study and test interventions that prevent dementia

- Scaling-up and/or integrating promising interventions that enable and change behaviour focusing on modifiable risk and protective factors for dementia

- Sharing Canadian research results on prevention-focused interventions

- Including assessment of brain health and function in healthy living intervention research

| Current status | Aspiration |

|---|---|

| Limited evidence about effective interventions to reduce risk for dementia and insufficient information resources. | Availability of effective prevention resources and interventions, supported by a strong evidence base. |

Area of focus 2.3: Expand awareness of modifiable risk and protective factors and effective interventions

As our understanding of factors that affect the risk of developing dementia grows and we learn more about interventions that are most effective in reducing risk, creating effective ways of sharing this knowledge broadly in a way that Canadians can understand will be important. By increasing awareness among both care providers and the general population, Canadians will be empowered to take action to protect their own health and reduce their risk of developing dementia. To be effective in our diverse country, awareness activities will need to be multi-lingual and culturally appropriate.

The development of dementia can begin as early as 20 years before symptoms can be observed to permit diagnosis. Footnote 31 As a result, a focus on health promotion that expands awareness and promotes lifestyle changes that can delay or reduce risk of dementia should start as early as possible.

In Canada and internationally, the development, implementation and adoption of healthy living interventions is ongoing. Researchers and health professionals are encouraged to seek opportunities to build on and integrate dementia into existing efforts.

Activities to expand awareness of modifiable risk and protective factors and effective interventions may include:

- Putting in place educational awareness activities and campaigns for preventing dementia among people of all ages in Canada with a focus on those most at risk

- Raising awareness among Canadians about brain health promotion and dementia prevention through messaging targeted at other chronic conditions with similar risk and protective factors

- Encouraging care providers to integrate brain health and dementia prevention information with information about other chronic conditions with similar risk and protective factors

| Current status | Aspiration |

|---|---|

| A lack of awareness among the general public and care providers about actions that may help prevent dementia. | All people living in Canada are aware of actions that prevent dementia. |

Area of focus 2.4: Support measures that increase the contribution of social and built environments to healthy living and adoption of healthy living behaviours

While it is important for people to be aware of risk and protective factors, this knowledge alone cannot prevent or delay the onset of dementia. People must also be supported by their environments — the people, places and social contexts that impact their daily lives. These environments, if appropriately designed, can make it easier to adopt healthy living behaviours, which may reduce the risk of developing dementia.

Social environments can have a significant impact on health, particularly mental health and wellbeing, as well as stress levels. A strong and stable social network and a built environment that supports active living can reduce the risk of social isolation that is often associated with aging, and is a risk factor for dementia.

While it can be difficult to identify the extent to which neighbourhood features influence healthy living, we know that the communities we live in can often be better designed to support our health. Footnote 32 For example, neighbourhood features such as walkable destinations, green spaces and gathering places have been linked to a greater sense of community and positive social interaction. Footnote 33 Neighbourhoods with complete streets (streets designed to be safe for people of all ages and abilities, regardless of their mode of transportation) can better support physical activity, while greater availability of healthy food (such as through community gardens) helps people make healthier food choices. Poor health, including obesity, is more common in areas where it is more difficult to access healthy food and where there are many unhealthy food options.Footnote 34

The built environment (which includes buildings, roads, green spaces, and public transit) varies across urban, rural and remote communities. Challenges in accessing transportation may greatly impact the ability to maintain healthy living behaviours, including access to healthy foods and maintaining social networks. For example, in rural and remote communities, public transportation may not be available or accessible. As a result, interventions and solutions may need to be different than those used in urban areas. Other factors in the built environment may contribute to the risk of developing dementia, such as those that also make it more challenging to be physically active and exposure to environmental risks including air pollution.Footnote 35

The World Health Organization's age-friendly communities model, adopted in Canada by over 1200 communities, is an example of an approach that seeks to support healthy and active aging. This approach helps older adults to live safely, enjoy good health and remain involved in their communitiesFootnote 36 (see Text box 4).

Text box 4: Age-friendly communities

There are 8 areas in which communities can take action to become more age-friendly:

- housing

- transportation

- outdoor spaces and buildings

- social participation

- respect and social inclusion

- civic participation and employment

- communication and information

- community support and health services*

Activities to support measures that increase the contribution of social and built environments to healthy living and the adoption of healthy living behaviours may include:

- Raising awareness of the impacts of social and built environments on the risk of developing dementia to foster greater support for initiatives to create healthy environments

- Encouraging programs and initiatives that support healthy social and built environments, including those that contribute to healthy aging and support older adults to age in place

- Delivering community-based programs that increase the adoption of healthy living behaviours related to modifiable risk and protective factors for dementia that are also linked to our environments, including targeted activities for higher-risk populations

- Evaluating best practices to make age-friendly communities more dementia-inclusive

| Current status | Aspiration |

|---|---|

| Barriers related to built and social environments limit the ability of individuals to pursue healthy living in ways that may reduce the risk of developing dementia. | All people living in Canada have access to built and social environments that support their ability to pursue healthy living in ways that may reduce their risk of developing dementia. |

Chapter 3: National objective: Advance therapies and find a cure

In 2013, Canada committed to support efforts to increase research funding for dementia with the aim of finding a disease-modifying treatment or cure by 2025 as a member of the Group of Eight nations (G8). Footnote 37 Canada is also committed to supporting the World Health Organization's Global action plan on the public health response to dementia (2017–2025), Footnote 38 which identifies "dementia research and innovation" as 1 of 7 priority areas of action.

While improving our understanding of dementia and finding possible ways to prevent or cure this condition requires a collective international effort, Canada boasts a strong brain health and dementia research community and is home to many internationally recognized researchers. As awareness of dementia has grown over the years, so has funding for dementia research by governments and other organizations in Canada. However, much more work remains to enhance our fundamental understanding of dementia and its root causes, and to use that knowledge to develop therapies and find a cure. Producing new knowledge and evaluating novel approaches for how best to treat dementia to support those with dementia to live well and advancing efforts towards finding a cure is one of the strategy's 3 national objectives.

Five areas of focus will support advancing therapies and finding a cure:

- 3.1 Establish and review strategic dementia research priorities for Canada

- 3.2 Increase dementia research

- 3.3 Develop innovative and effective therapeutic approaches

- 3.4 Engage people living with dementia and caregivers in the development of therapies

- 3.5 Increase adoption of research findings that support the strategy, including in clinical practice and through community supports

Area of focus 3.1: Establish and review strategic dementia research priorities for Canada

The strategy will encourage efforts to support an inclusive approach to the selection of dementia research priorities, one that is informed by engagement with key stakeholders including people living with dementia and caregivers.

Priority setting also allows us to build on Canadian strengths, support international commitments, and advance Canadian priorities including the strategy's 3 national objectives of preventing dementia, advancing therapies and finding a cure, and improving the quality of life of people living with dementia and caregivers. In addition, regular review of research priorities related to therapies and finding a cure will ensure these priorities remain relevant in addressing gaps in knowledge and are responsive to new research findings.

Priority setting for dementia research is best accomplished with input from diverse stakeholders and populations (e.g. researchers, academics, care providers, industry, organizations, cultural minorities, First Nations, Métis and Inuit) and, most importantly, people living with dementia and caregivers. A broad approach ensures research includes a focus on issues that affect those living with dementia and those who provide care.

Building on the work done through the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) Dementia Research Strategy, the CIHR and partner funded Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA) funding will continue to address dementia research across the 3 themes of primary prevention, secondary prevention, and quality of life (see Text box 5), which are well aligned with the 3 national objectives of the national dementia strategy. Additionally, CIHR will continue to work with international partners to identify and address research priorities.

Text box 5: Research themes of the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (Phase II)

Primary prevention: To examine the basic mechanisms to prevent cognitive impairment and dementia.

Treatment and secondary prevention: To improve early detection (diagnostics) and treatment of dementia.

Quality of life: improving the management of dementia and the quality of life for those living with dementia and caregivers.

Another example of a stakeholder-engaged priority setting approach comes from a collaborative effort among the Alzheimer Society of Canada, the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, and the CCNA. The Canadian Dementia Priority Setting PartnershipFootnote 39 initiative was undertaken to better understand research priorities of those living with dementia, caregivers, families, health and social care providers and the general public. The Partnership questions focused on living with dementia, dementia prevention, treatment and diagnosis. Questions on cure and the biological mechanisms of dementia were not included in this prioritization exercise. The outcome of this priority setting process differs from those dementia research priorities outlined by the World Health Organization in 2016, which was informed by researchers, clinicians, and health and care workers (see Table 1). For example, stigma, and early treatment were prioritized by the Partnership while the WHO priorities included a strong focus on prevention, diagnosis and therapies. These differences demonstrate the importance of dialogue with multiple stakeholders when setting and reviewing research priorities.

International research priorities for dementia identified by the WHO in 2016 fell into 59 thematic research areas which were organized into the top 7 thematic research domainsFootnote 40 (see Text box 6). Research priorities were identified for each thematic research domain.

Text box 6: 2016 World Health Organization dementia thematic research domains:

- Prevention, identification and risk reduction

- Quality of care for people with dementia and their caregivers

- Delivery of care for people with dementia and their caregivers

- Diagnosis, biomarker development, and disease monitoring

- Drug and non-drug clinical-translational research

- Public awareness and understanding

- Physiology and progression of normal ageing and disease development*

* Research Priorities to Reduce the Global Burden of Dementia by 2025

| 2017 The Canadian Dementia Priority Setting Partnership Initiative - Research priorities | 2016 World Health Organization's dementia research priorities |

|---|---|

| (Participants were Canadians affected by dementia including people with dementia, care partners, family, friends and health and social care providers) | (Participants were researchers, clinicians and health and care workers) |

| 1. Addressing stigma | 1. Prevention and risk reduction; relationship with chronic diseases |

| 2. Emotional wellbeing | 2. Identify clinical practices and interventions to promote timely and accurate diagnosis |

| 3. Impact of early treatment | 3. Diversify therapeutic approaches (drug and non-drug) |

| 4. Health system capacity | 4. Brain health promotion and dementia prevention communication strategies |

| 5. Caregiver support | 5. Understand contributions of vascular conditions |

| 6. Access to information and services post-diagnosis | 6. Influence and interactions of non-modifiable and modifiable risk and protective factors |

| 7. Care provider education | 7. Interventions to address risk factors |

| 8. Dementia-friendly communities | 8. Models of care and support in the community |

| 9. Implementing best practices for care | 9. Educating, training and supporting formal and informal carers |

| 10. Non-drug approaches to managing symptoms | 10. Later-life and end-of-life care, including advance care planning |

Activities to support efforts to establish and review strategic dementia research priorities for Canada may include:

- Enabling consideration of diverse perspectives when setting and reviewing strategic dementia research priorities in Canada

- Exploring ways to bring together those working in different disciplines of dementia research to leverage and align efforts

- Supporting dementia research priority setting summits that are open to a broad range of stakeholders

| Current status | Aspiration |

|---|---|

| Limited broad stakeholder input when setting research priorities and insufficient engagement of people living with dementia and caregivers. | Research priorities established in an inclusive manner with broad stakeholder input, with the participation of those living with dementia and caregivers. |

Area of focus 3.2: Increase dementia research

There is a wealth of dementia-related research supported through different funding mechanisms and a variety of national and international organizations. This research addresses many aspects of dementia, including but not limited to: biomedical, clinical, health systems and population health research. Investing in research that explores these elements is critical for the advancement of our understanding of dementia and our ability to treat and manage it as a society. However, there is much more to be explored and learned to find more effective approaches to treat dementia.

Biomedical research aims to understand at the cellular level what changes are occurring in the brain and why. For example, there has been a focus over the last thirty years on two proteins in the brain that are linked to dementia: beta-amyloid and tauFootnote 42. These two proteins reach abnormally high levels in the brain of someone with dementia. Clinical research examines the safety and effectiveness of medications, devices, tools for diagnosis, and therapies. Other types of research include health systems research which examines how people access health services, health professionals, care costs and outcomes. Population health research aims to examine the health of an entire population, understanding how social, cultural, environmental, occupational and economic factors can influence health status.

Moving forward, there is an opportunity to harness Canada's broad and rich foundation of research through strategic partnerships and initiatives to focus efforts on advancing therapies that can prevent, slow or stop the changes underway in the brain that are associated with dementia, as well as working towards the ultimate goal of finding a cure. Using a variety of approaches to fund dementia research may enable us to leverage research investments for greater impact. For example, public-private partnerships allow government and the private sector to work towards common goals while sharing risk and expertise. There may be potential to match funding to increase impact; an example is the partnership between Health Canada and Brain Canada for the Canada Brain Research Fund where non-governmental funding is matched by the Government of Canada.

Strategic and targeted research investments for chronic diseases, such as cancer, heart disease and stroke have had a significant positive impact in Canada. For example, cancer prevention and control efforts and the importance of maintaining heart health by addressing risk factors have resulted in advancements in prevention, diagnosis and treatments for these diseases. Focusing on strategic and targeted investments may result in similar impacts for dementia in Canada.

The federal government, through the CIHR, applies a dual approach in supporting research on dementia. CIHR investments in dementia research totalled close to $200 million between 2013–14 and 2017–18. This investment is both fundamental and strategic in nature, and includes both domestic and international components of the CIHR Dementia Research Strategy. Additionally, the Government of Canada funds dementia-relevant research and innovation networks — AGE-WELL, the Centre for Aging + Brain Health Innovation (CABHI), and the Canadian Frailty Network. Canada's research efforts are spread across provinces, territories and many organizations, and are often collaborative (see examples in Text box 7).

Text box 7: Highlights of non-federal dementia research investments in Canada

The following are examples of investments in dementia research from provincial governments, academia, health charities and other organizations.

Over the past 6 years, Alberta Innovates, the largest research and innovation agency in Alberta, has invested over $2.9 million in Alzheimer's research. Alberta Innovates co-funds the Alberta Alzheimer Research Program through the Alberta Prion Research Institute which helps researchers better understand the fundamental mechanisms of the disease and improve the quality of life of those living with dementia.

Since 1989, the Alzheimer Society of Canada's Alzheimer Research Program has funded $53 million in grants and awards in biomedical and quality of life research.

Through the Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé, the Government of Quebec funds research on the causes, prevention, screening, diagnosis and treatment of age-related conditions, including dementia.

Ontario Brain Institute is a research centre that maximizes the impact of neuroscience through translational research (applied research) aimed at developing therapeutics for the prevention and/or treatment of human disease. For example, through the ONtrepreneurs program, the company RetiSpec was awarded $50K to develop a non-invasive eye scanner for early detection of Alzheimer's disease, which will dramatically reduce diagnostic costs and advance the detection of Alzheimer's disease.

The Pacific Alzheimer Research Foundation focuses exclusively on funding scientific research and investigation into the cause, prevention and treatment of dementia. The Foundation received a $15 million grant from the British Columbia government in 2006 and this endowment has been supplemented by private donations.

Research Manitoba and the Centre for Aging + Brain Health Innovation launched a funding opportunity through the Accelerating Innovations for Aging and Brain Health program (2018-2019) focused on priority innovation themes. In particular, the Aging in Place theme is advancing solutions that enable older adults with dementia to maximize their independence and quality of life.

In 2017, the Weston Brain Institute announced $30 million in grants for researchers to fight neurodegenerative diseases including dementia. This is in addition to the $100M announced in 2016 by the Weston Brain Institute for high-risk, high-reward translational research projects with the potential to help speed up the development of treatments.

Activities to increase dementia research may include:

- Continuing to leverage existing federal investments and working with potential funding organizations to increase overall Canadian investment in dementia research

- Pursuing international opportunities to expand investments including through new funding models

| Current status | Aspiration |

|---|---|

| Annual investment in dementia research in Canada is less than 1% of dementia care costs. | Annual investment in dementia research in Canada exceeds 1% of dementia care costs. |

Area of focus 3.3: Develop innovative and effective therapeutic approaches

The development of innovative approaches to therapies across all stages of dementia, from before symptoms appear to early and advanced symptoms, will be encouraged. Therapies can include any intervention that rehabilitates, provides positive social adjustment and improves quality of life.

Types of innovation could include new technologies, along with social and biomedical innovations such as assistive technologies, individualized cognitive training, drug and non-drug therapies. Assistive technologies can include devices or systems that support a person with dementia to maintain or improve their independence, safety and overall wellbeing. Examples include clocks to assist with telling time, including whether it is day or night, communication aids, electric appliance monitors, picture phones, reminder devices, as well as in-home cameras and home monitoring devices that help caregivers and care providers properly and safely care for people living with dementia. Cognitive training has been shown to improve skills and quality of life for people with dementia through activities such as categorization, word association and discussions of current affairs, which can improve mood and concentration. Further scientific testing of these and other promising therapeutic approaches is needed before wide-scale adoption by the medical community.

There is currently no cure for dementia; however, some drug therapies have been proven to have modest benefits on cognitive abilities such as improving memory and thinking. Current guidance suggests that drug therapies should not be the first choice for managing behavioural and psychological symptoms associated with dementia because their effectiveness is modest and there is a risk of harm associated with use. Footnote 43, Footnote 44 In addition, better understanding is required with some drug therapies due to the increased complexity of care when an individual is receiving treatment for dementia along with medications for other chronic conditions, particularly if the person is of an advanced age. Limited progress on drug therapies highlights the need to support innovative and effective non-drug therapies. These non-drug options can include music therapy, aromatherapy, pet therapy and massage therapy. While still requiring scientific validation, Footnote 45, Footnote 46 these therapies have shown promising benefits for people with dementia.

Activities to develop innovative and effective therapeutic approaches may include:

- Strategically focusing investments on developing innovative and effective therapeutic approaches

- Enhancing Canadian efforts at the international level to promote innovation in dementia research

- Ensuring that the federal regulatory framework for approval of new drugs is flexible and responds to the need for timely access to novel and innovative therapies

- Fostering interdisciplinary approaches to innovation that bring together stakeholders and researchers to develop and identify effective and timely therapies

- Encouraging opportunities for hospitals and associated academic institutions to adopt innovative approaches to therapies — many of these institutions are teaching hospitals where health professionals in training can test and apply new approaches

- Exploring the feasibility of expanding the use of a tailored person-centred care model rather than a focus on the condition

| Current status | Aspiration |

|---|---|

| Options for evidence-informed therapies remain limited and often are not person-centred. | New evidence-informed person-centred therapies are more readily available. |

Area of focus 3.4: Engage people living with dementia and caregivers in the development of therapies

For research on dementia therapies to be effective and culturally appropriate, people living with dementia as well as their families and caregivers must be meaningfully involved as active participants and partners. Their voluntary participation is a vital contribution to our understanding of which therapies are effective, as well as a core tenet of ethical research practice.

For example, Canada's Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR), a CIHR-partnered initiative, funds research that fosters evidence-informed health care by bringing innovative diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to the point of care. SPOR's Patient Engagement Framework Footnote 47 is based on a vision where patients are active partners in health research which leads to improved health outcomes and an enhanced health care system. Through a collaborative and stakeholder-partnered approach, SPOR builds capacity in patient-oriented research and promotes patient engagement (see Text box 8). Such a model can be drawn upon to guide future patient-centric approaches in dementia.

Text box 8: Canadian Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research

“Patients bring the perspective as ‘experts' from their unique experience and knowledge gained through living with a condition or illness, as well as their experiences with treatments and the health care system.”*

By encouraging a diversity of patients to tell their stories, new themes may emerge to guide research. Patients gain many benefits through their involvement in research including increased confidence, new skills, greater access to useable information, and a feeling of accomplishment from contributing to research relevant to their needs.

* Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research: Patient Engagement Framework (PDF)

Activities to engage people living with dementia and caregivers in the development of therapies may include:

- Leveraging collaborative work already underway that engages people living with dementia

- Providing financial supports to caregivers so they can assist people living with dementia in participating in research activities

| Current status | Aspiration |

|---|---|

| People living with dementia and caregivers are predominantly the subject of research to develop new therapies and find a cure. | People living with dementia and caregivers are active participants and partners in research to develop new therapies and find a cure. |

Area of focus 3.5: Increase adoption of research findings that support the strategy, including in clinical practice and through community supports.

Research has shown that there is a gap between health research findings and their practical use in clinical settings. Footnote 48 Traditionally, researchers publish findings in academic journals and other researchers consider this new evidence. However, more can be done to turn research findings on therapies for people living with dementia more quickly into relevant information that can be adapted and adopted in clinical, community and family settings.

Barriers to putting research findings into practice may reduce the ability of health professionals to make informed decisions and prevent patients from benefitting from promising therapies. These barriers include a lack of mechanisms to assist researchers and practitioners in moving research findings toward adoption, uncertainty of researchers about their roles in facilitating adoption, and difficulty in gaining access to clinical settings to test new interventions.

"If the incidence of dementia is to be reduced and the lives of people with dementia are to be improved, research and innovation are crucial, as is their translation into daily practice."*

* WHO Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia (2017-2025)

To enable broad adoption by all those who could benefit, research findings need to be turned into practical information in ways that are affordable. It is also important that research findings are communicated in ways that increase accessibility and are culturally appropriate across diverse communities such as Indigenous peoples, immigrant and minority language communities, LGBTQ2 individuals, people with intellectual disabilities, as well as those who live in rural and remote settings or in federal and provincial custody.

Activities to increase adoption of research findings that support the strategy, including in clinical practice and through community supports may include:

- Supporting projects that generate knowledge on how to effectively and quickly test research findings that can then be used in real-world settings

- Encouraging research design that includes an approach to share research results and encourage their adoption

- Developing mechanisms that support the sharing of best available research findings and potential innovations in ways that make them easier to adopt

| Current status | Aspiration |

|---|---|

| Research findings tend to stay within academic settings and journals and are not broadly known, accepted, or brought into clinical practice. | Research design always includes efforts that ensure findings can be understood, adopted and quickly put into practice. |

Chapter 4: National objective: Improve the quality of life of people living with dementia and caregivers

The quality of life of those living with dementia and caregivers is the motivation for the national dementia strategy. In 2015–16, over 419,000 (6.9%) Canadians aged 65 years and older were living with diagnosed dementia. Footnote 49 In 2012, approximately 8.1 million individuals, or 28% of Canadians aged 15 years and older, were family/friend caregivers for a person with a long-term health condition, disability or aging needs. Footnote 50 Of these caregivers, approximately 486,000 (or 6%) were caring for an individual with dementia. Footnote 51 With the aging population, the number of caregivers is expected to grow.

While recognizing the importance of funding for health care, social services and other types of resources, 5 areas of focus will support improving the quality of life of people living with dementia and caregivers.

- 4.1 Eliminate stigma and promote measures that create supportive and safe dementia-inclusive communities

- 4.2 Promote and enable early diagnosis to support planning and action that maximizes quality of life