Informing a Framework for Diabetes in Canada: Stakeholder Engagement Summary

Download in PDF format

(1.5 MB, 53 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: 2022-09-13

Foreword

The Public Health Agency of Canada recognizes that diabetes is a serious chronic disease that poses significant challenges for people in Canada living with the disease, their families and communities, as well as the health system.

In accordance with the National Framework for Diabetes Act and as part of efforts to address diabetes, the Public Health Agency of Canada retained the Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue based at Simon Fraser University, to undertake a formal (virtual) engagement process (February to May 2022) to help inform the development of a diabetes framework for Canada.

A wide range of key stakeholders, including people living with diabetes, caregivers, health professionals, advocacy groups, Indigenous peoples and researchers, had an opportunity to share their views, experiences and perspectives to help identify priorities for advancing efforts on diabetes in Canada, and to inform the development of a framework. Perspectives of provincial and territorial governments were also sought through existing federal, provincial and territorial mechanisms.

With the engagement process for the development of the framework now completed, the Public Health Agency of Canada is pleased to share a summary of the stakeholder engagement, and wishes to thank the Morris J. Wosk Centre for their work to engage stakeholders and prepare this summary report. Our sincere gratitude also goes to the many stakeholder organizations and Canadians who provided their diverse perspectives to help inform the framework.

Background

The engagements described in this report sought input from a wide range of stakeholders affected by or working in relation to diabetes. This work responds directly to “An Act to establish a national framework for diabetes,” which received Royal Assent on June 29, 2021. The Act requires the Minister of Health, in consultation with stakeholders, to develop a framework designed to support improved access to diabetes prevention and treatment to ensure better health outcomes for Canadians.

A series of engagement activities, including key informant interviews, virtual dialogue sessions, and an online survey were used to invite people with a connection to diabetes to share their ideas and priorities to improve the lives of Canadians affected by the many forms of this disease. These activities took place between February and May of 2022.

Purpose of this document

Each of the 3 engagement processes resulted in a report on "What We Heard" during that part of the process; these reports can be found in the appendices to this document.

This document endeavors to provide a description of the engagement process and a high-level summary of the key findings to date. While this is not a comprehensive compilation, what we have heard has been synthesized into a narrative form. This work does not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Centre for Dialogue, the University at-large, nor of the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Acknowledgment

The process of engaging stakeholders for the purpose of informing a diabetes framework was convened by Simon Fraser University’s Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue in partnership with the Public Health Agency of Canada.Footnote 1 The Centre for Dialogue and the Public Health Agency of Canada are grateful for everyone who volunteered their time to participate in this engagement process. The diversity of participant's lived experience, knowledge and expertise broadened and deepened the stories we heard.

Table of contents

- Engagement process

- Central themes emerging from the engagement process

- Appendix I: Key informant interviews report

- Appendix II: What we heard report (dialogues)

- Appendix III: Summary of Ethelo report

Engagement process

In recognition of the unique perspectives of Indigenous Peoples, the principles of reconciliation and the right to self-determination, an Indigenous-led engagement process separate from this initiative is under way. As such, the voice of Indigenous Peoples was welcomed but not specifically sought out during this series of activities.

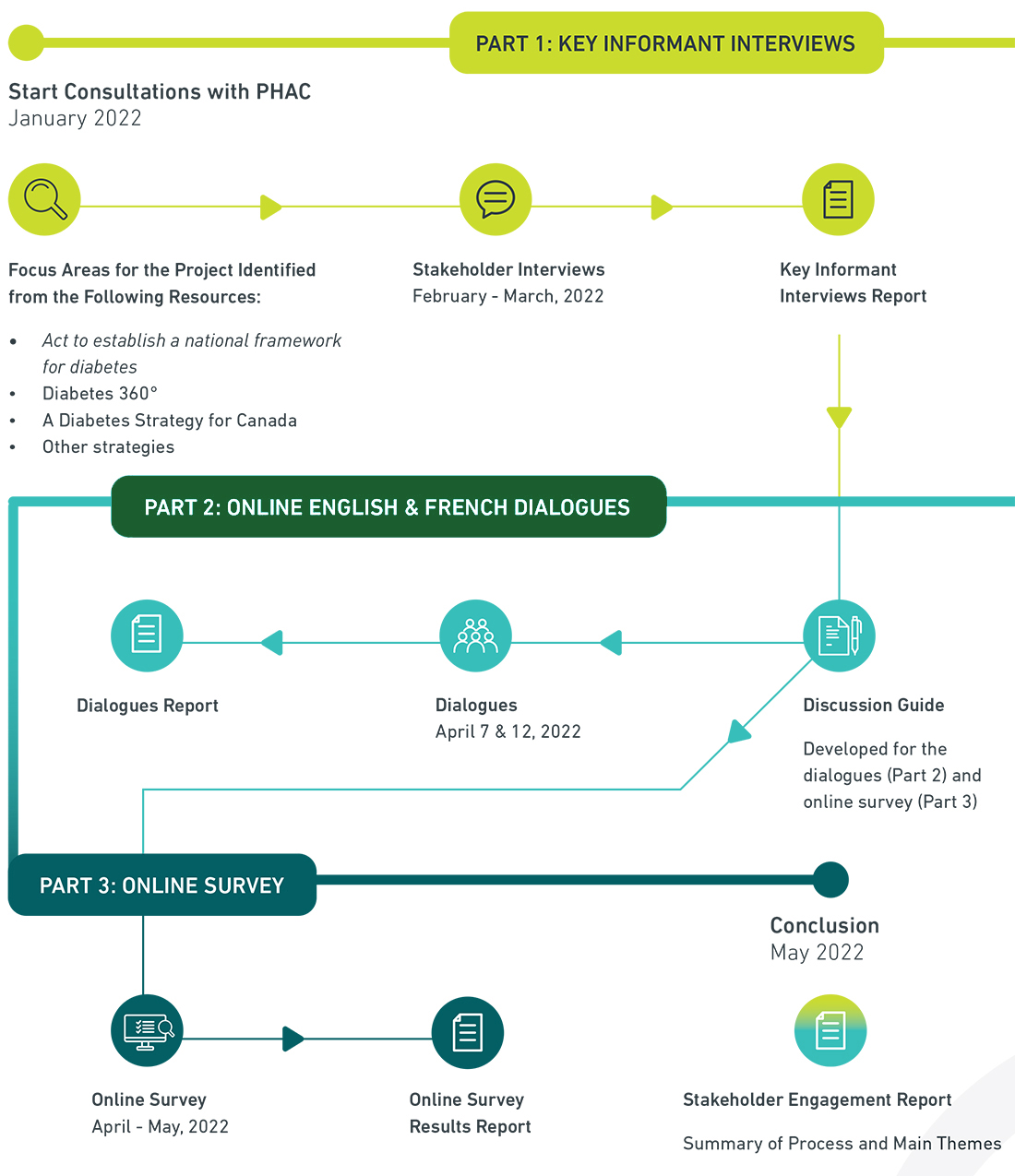

The approach to the stakeholder engagement initiative is outlined in Figure 1. We began by identifying key themes from a document review which included:

- An Act to establish a national framework for diabetes

- Diabetes 360°: A Framework for a Diabetes Strategy for Canada developed by Diabetes Canada

- A Diabetes Strategy for Canada, Report of the Standing Committee on Health, April 2019

- Other strategies and documents

Themes were identified to use as prompts during the key informant interviews including: determinants of health, health system (including care and treatment), prevention, research and surveillance, and the Disability Tax Credit.

Key informants were identified in collaboration with the Public Health Agency of Canada to support an initial broad understanding of diabetes in Canada. The ideas offered during these interviews can be found in Appendix I.

The findings from the key informant interviews served to inform the development of a discussion guide for 2 virtual dialogue sessions. Invitations to the English and French dialogue sessions were sent to a broad range of stakeholders identified as having an interest in diabetes. What we heard during the dialogues is summarized in Appendix II.

To further broaden the opportunity for stakeholders to provide input, a survey based on the discussion guide was administered by Ethelo, an online engagement platform. The survey was distributed to previously identified stakeholders, who were encouraged to distribute it to their networks. A summary report is provided in Appendix III.

All engagement activities were offered in French and English.

Figure 1: Project phases

Text description

Part 1 (in yellow): Consultations with PHAC began in January 2022 to identify key resources to review to determine focus areas for the project. These key resources included Bill C-237, Diabetes 360, A Diabetes Strategy for Canada, and other strategies and documents. Stakeholder interviews were conducted in February and March, 2022 and a Key Informant Interviews Report was developed.

Part 2 (in green): The key Informant Interviews Report informed the development of a discussion guide for the dialogues which occurred on April 7th and April 12th, 2022 and which generated a Dialogues Report and informed the development of an online survey.

Part 3 (in dark blue): The online survey ran in April and May, 2022, generating an Survey Results Report. In May, 2022, the engagement process concluded and a Stakeholder Engagement Report was developed which provided a summary of the processes and main themes.

Who we heard from

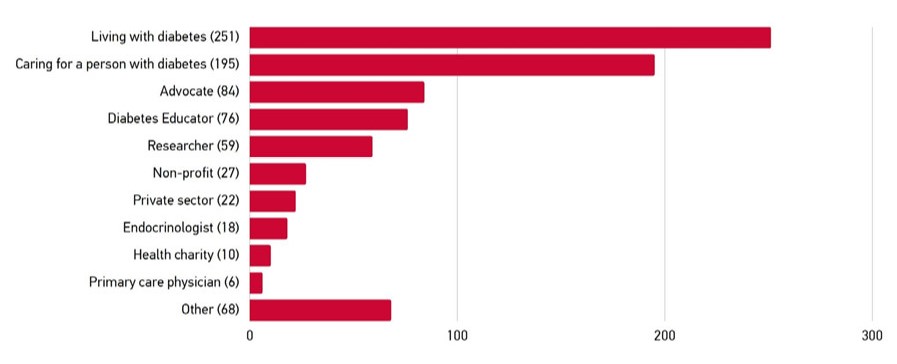

We sought to engage a wide variety of stakeholders including people living with and caring for people with diabetes and those working in different parts of the systems that address the disease in its many forms.

For the key informant interviews that made up phase 1 of the engagement we aimed to gain an initial overview of priorities as identified by several stakeholder groups, including individuals living with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, diabetes researchers who work with diverse populations, health care professionals, non-profits, and more. We heard from individuals living and working in different areas of the country, including stakeholders familiar with the challenges of living and working in remote regions and with marginalized populations. We conducted a total of 32 key informant interviews with 50 different individuals connected to diabetes.

The virtual dialogues were similarly attended by individuals from multiple sectors, professions and advocacy groups, who helped to broadened our understanding and provide invaluable input on what we had heard to date, including what was missing. We learned more about the intersections of race and disability with diabetes, and about the challenges specific to living with different types of diabetes. Over 80 individuals attended the dialogue sessions.

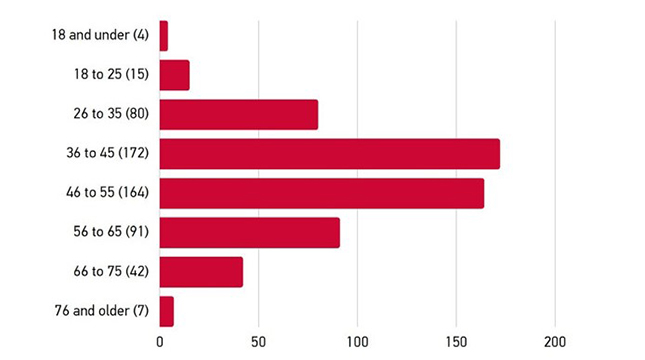

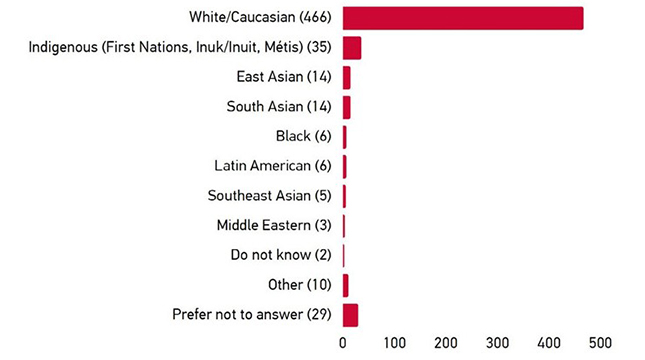

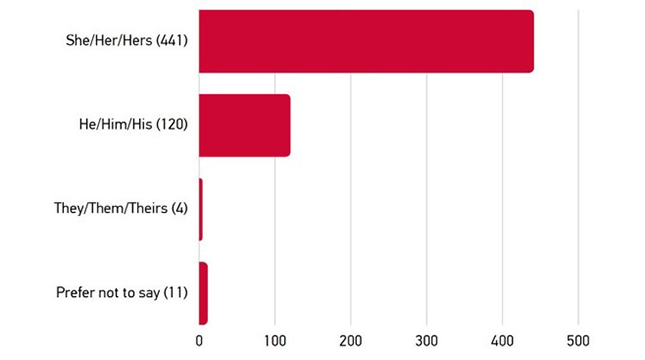

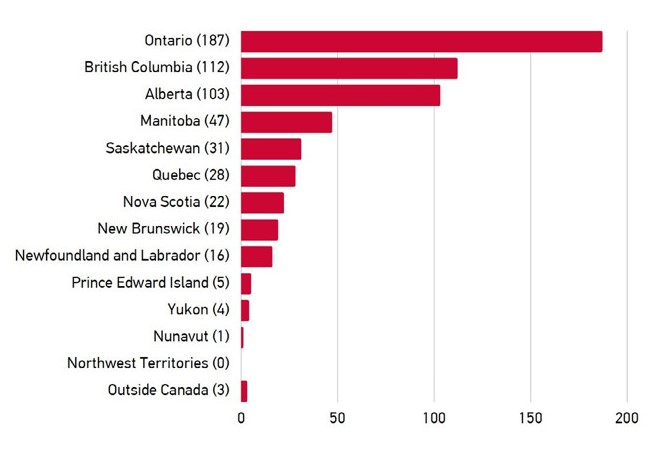

The survey on the Ethelo platform offered the broadest opportunity of engagement to interested stakeholders, with 884 individuals providing input. The majority of this input was from individuals self-identifying as female (73%) and white/Caucasian (80%). 35 individuals identified as Indigenous (First Nations, Inuk/Inuit, Métis) (5.9%). Ontario and BC-based participants accounted for 50% of the total. The regional split was similar to the overall population. 55% of participants indicated they either have a type of diabetes or caring for someone who does.

Part 1: Key informant interviews

- 32 interviews

- 50 individuals

Part 2: Online English and French dialogues

- English

- 101 registered

- 76 participants present

- French

- 13 registered

- 8 participants present

Part 3: Online survey (5 weeks)

- 2,911 people visited the engagement

- 884 people participated on the English language platform

- 38 people participated on the French language platform

- 4,850 total survey comments

Figure 2: Stakeholders

People with lived experience

Individuals living with type 1 diabetes (T1D), type 2 diabetes (T2D) and other forms of diabetes and its complications, including blindness or low-vision. Family members and caregivers, particularly parents of children with T1D.

People working in healthcare

A wide range of stakeholders working with all types of diabetes patients in the care system, including endocrinologists, primary care physicians, dieticians, nurses, general practitioners, First Nations health professionals, occupational therapists and other allied health professionals.

Advocates, health charities and other not-for-profits

Groups advocating, caring and providing services for persons living with diabetes, its complications and its associated diseases.

Researchers

Researchers whose work either centres on, or is relevant to, improving the lives of Canadians with diabetes, including diverse areas of interest such as clinical research, community engaged research, and public policy analysis.

Private sector

Private sector organizations whose work relates to diabetes, include medical device manufacturers, digital technologies and pharmaceutical companies.Central themes emerging from the engagement process

Through the 3 parts of this stakeholder engagement process we learned a great deal about the tapestry of considerations that are on the minds of people connected to diabetes in Canada. What follows is a narrative account that attempts to integrate what we heard and is intended to give voice to the main storylines.

Connections between inequity and diabetes

“It’s impossible to self-manage when your basic needs aren’t being met.”

Throughout the many conversations we had across the full engagement process, stakeholders unpacked the interconnections that inequity has with diabetes in Canada. The Covid-19 pandemic was frequently at the forefront of these conversations – it laid bare many of the inequities that currently exist in our care systems and is giving voice to stakeholders hoping to build a better future. Participants from racialized and Indigenous communities spoke to the need to explicitly name racism and colonialism as factors driving increases in diabetes. They reinforced that for these and other historically marginalized populations, a focus on healthy living is relatively meaningless in the face of poverty, lack of access to healthy food, safe spaces to live, and mistrust in systems that do not work in the best interests of marginalized populations.

Given the patchwork of care across Canada, people connected to diabetes feel inequity acutely through lack of access to all they need to be able to live a healthy life. Access to care, medication, devices, financial supports and diabetes education varies considerably between provinces and territories. Social determinants of health, geography, the presence of a disability and other factors further influence an individual’s access to the support they need. Visually impaired individuals described the inaccessibility of essential blood glucose monitoring devices. We heard about individuals and families having to prepare for a day’s travel to attend a 15-minute appointment with a specialist. We heard many stories of challenges that people face in gaining equitable access to essential care for their diabetes.

Our informants – particularly those with lived experience – clearly prioritized addressing the social determinants of health and inequity. Racialized, Indigenous and other individuals from marginalized populations spoke about the need to place their members at the forefront of problem-solving and in leadership positions; communities know themselves best and hold unique knowledge and expertise. Stakeholders also supported ideas like scale-up of efforts that are proving effective and development of comprehensive strategies as important ways to support marginalized populations.

Advances made in virtual health care during the pandemic were identified as a point of hope in improving equity of access, but was measured by disparities in access to reliable internet service and technology. Other suggestions for addressing equity included making improvements to the current Disability Tax Credit and exploring alternative tax measures and means of financial support. Anti-racism training for professionals and developing team-based care systems were seen as health system improvements that could also help reduce inequities.

Distinguishing between diabetes types

Type 1 (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) are very different diseases that are “lumped” together because of their common characteristic: high blood sugar. It was acknowledged by many that there are also other forms of diabetes including gestational diabetes and maturity onset diabetes of the young, but what we heard was mostly about the differences between T1D and the much larger population of people with T2D.

Stakeholders were clear that T1D and T2D are very different diseases and are experienced very differently, be it medically, socially, financially, and/or psychologically.

Individuals living with T1D were particularly concerned that the engagement process and framework adequately account for the factors specific to their disease. These factors include the psychological load of managing a life-threatening disease, the challenges of developing this disease as a young person, the impacts that an individual’s T1D diagnosis has on entire families, and the differences in clinical care necessary to thrive. Individuals with T1D wanted physicians and care systems to take seriously how stress, burnout and isolation affects their mental and physical health. They also noted that messages about preventing diabetes were irrelevant to them and should be identified as specific to other diabetes types, whereas the necessity of developing a cure for T1D – and supporting research to achieve this aim – should be reinforced.

Individuals with T1D also spoke about the challenges of accessing the Disability Tax Credit and other financial supports that would allow them to have to have access to expensive devices such as continuous glucose monitoring systems. We heard about care providers who were unwilling to fill out the awkward and cumbersome paperwork for the Disability Tax Credit because the questions as they apply to diabetes are unclear; the paperwork is time consuming and some physicians fear a federal audit when some of the questions are difficult to answer, such as the thresholds for time spent managing the disability.

“DTC should automatically be approved for TYPE 1 DIABETES. It is an autoimmune disease that requires 24/7/365 care. End of story.”

Systems which enable continuous glucose monitoring and closed-loop glucose control are considered major advances for people living with T1D. These systems are expensive and coverage is limited or nonexistent in many jurisdictions.

“Knowledge is power. Understanding all of the data is understanding your chronic disease and what influences it.”

But access to the devices and the data they collect, in a form that promotes understanding for both patient and provider is uneven. People with lived experience talked about differences in device manufacturers, diabetes education, care providers and coverage. Many stakeholders noted how Canada lags other jurisdictions in approving and making available the latest technological advancements in glucose monitoring. T1D patients wanted access to their preferred devices and emphasized the impact that this would have on their overall quality of life. Researchers talked about the importance of the data in understanding newly accessible parameters like 'time in range' and its value in self-management and the prevention of complications.

Moving from stigma and shame to support

“Empathy and respect are in short supply.”

The stigma associated with having diabetes was also high on people's list of priorities, but as we heard, stigma is a very different story for people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Regarding T2D, there is a considerable blame and shame associated with the disease, as well as with obesity, which at the population level is considered a risk factor for developing diabetes. That T2D is commonly thought of as being the result of poor lifestyle choices, and solvable by “eating less and moving more” just adds to the blame and shame mentality. Individuals spoke of feeling judgement not only from acquaintances, but from people close to them and from health care providers. They asked for more education and awareness campaigns that would help the public better understand their disease and how to support them.

People with T1D spoke about feeling shame in the context of dealings with medical professionals about the degree to which they control their blood sugar and HbA1C. This was further complicated for young people for whom self- management is very difficult and psychologically taxing.

We heard from several people living with diabetes about the vicious cycle created by shame and blame, leading to non-disclosure, worse outcomes, and more shame and blame. As one individual notes, "patients need comfort in speaking the truth on their issues without shame." Stakeholders called for more flexibility and humanity in support systems, more inclusion, more consultation, more understanding, and less judgment. Improved training that fosters people-centered and age-appropriate approaches to care were recommended.

Rethinking prevention

Prevention was identified by many stakeholders as an essential means of reducing rates of T2D in Canada. However, as noted, talk of “prevention” is problematic in many contexts, particularly when tied to messaging that does not account for the social determinants of health, or when misunderstood to be relevant to type 1 diabetes.

Stakeholders spoke to other issues related to prevention as well. Researchers and health professionals informed us that better access and use of screening is important for preventing the complications of diabetes. Another overarching message heard about traditional prevention efforts regarding diet and exercise fail to account for the realities of many people’s daily lives. Researchers shared examples of working collaboratively with communities to co-develop culturally relevant and locally appropriate interventions. Many stakeholders noted that it is time for Canada to move beyond its reputation as “a nation of pilot projects” when it comes to prevention efforts, and to invest in scaling-up programs that have proven to be effective and relevant to specific population groups.

Accessible and appropriate health care

Stakeholders offered a variety of ideas about what can be done to improve delivery of care. In addition to the system drivers of inequality and stigma, there was strong support for centering the patient and their families. People living with diabetes want to be provided with the tools, education, support and resources necessary to empower them in the management of their own care and as leaders and partners in research, community- led collaborative efforts, intervention design and implementation.

Stakeholders identified several ways of supporting patients and increasing their ability to collaborate effectively in their own care. One of these was providing patients with access to their own data and metrics around diabetes, and education around how to interpret these and convey that information to caregivers and family.

Easing access to blood tests and reducing unnecessary visits to general practitioners was also noted as a means of streamlining care. Tailoring care to patients’ needs and strengths (or “meeting them where they’re at” ) was a dominant theme.

As has been previously noted, patients need access to devices and medications that best meet their needs in order to manage their own care effectively. Individuals connected to health care service funding and delivery noted that funders prioritize immediate costs and fail to take a longer view, resulting in lower quality care and worse long-term outcomes. There were several calls to shift the health care system’s mindset from an emphasis on unit cost to a broader, more comprehensive view of costs and benefits that centers patients’ long-term health.

Many spoke of the need to develop more interdisciplinary/ team-based approaches and to expand the scope of practice and education of allied health professionals. These suggestions were linked to lessening patient administrative loads in coordinating their care, matching patient care needs to the most appropriate practitioners, and making care more accessible throughout the system. Stakeholders spoke to the general practitioner shortage across Canada and the lack of fit between our primary-care based care model and chronic conditions like diabetes.

Building care capacity in other parts of the professional system and through peer support was identified as a means of improving the patient experience.

Digital health was also identified as having the potential to amplify the capacity of people, providers, communities, and systems. As previously noted, however, it has its own accessibility issues, and is not always an appropriate replacement for in-person care.

Research, surveillance and data

We heard a considerable amount about many important challenges and opportunities relevant to research, surveillance and data. This thread was particularly strong during the key informant interviews, not surprisingly given that many researchers and health professionals were targeted in the first part of the engagement. We heard about the well-known, long-standing challenge for researchers to access data due to fragmentation, privacy and ethics policies, and practices in the public sector. While access for researchers has been improving, it is still seen as a significant barrier. Researchers called for registries, repositories, data lakes and surveillance systems of various kinds that would enable a deeper understanding from patient, provider and system perspectives. Some interviewees pointed to the value of publicly available dashboards that would help us monitor our progress against the framework.

Informants called out a variety of data gaps including quality of life indicators, impacts of prevention, and mental health in people with lived experience. They also spoke to centering patients and their needs in the design of data systems, with patients having the option to opt in or out. We learned about community driven models of data ownership and other efforts to simplify the challenges associated with our current approaches to data privacy and ethics.

Regarding research, participants noted it should be patient-driven, not just patient-inclusive, and called for a shift so that research is aligned first and foremost with patient and community needs and engages patients throughout the research timeline.

The patient perspective on data came through in the comments sections of the survey where persons with lived experience of T1D focused on the importance of continuous glucose monitoring systems. Many survey respondents felt more and better focused research was a good idea, especially with respect to finding a cure; others felt we know a lot but don't do a good job applying what we know. We also heard about the importance of practice guidelines as a tool for synthesizing the available evidence and for the opportunity to set standards for care delivery, but we need to make them more relevant and accessible for both professionals and patients.

Collaborating for systems change

“Collaboration truly requires conversation.”

Many of the people we talked to and who provided their comments on the survey platform felt that collaboration was key to increasing the quality of life for people affected by diabetes.

Stakeholders recognized the complexity of addressing diabetes in a framework and wanted approaches that would support ongoing inter-sectoral collaborations, foster problem solving and build the bridges needed to successfully execute the framework. Specific recommendations for collaboration included fostering inter-jurisdictional knowledge exchange about successful interventions, creating knowledge hubs, and evaluation of the indicators and outcomes that are most important to diabetes care.

Appendix I: Key informant interviews report

Diabetes framework: Stakeholder engagement

Phase 1: February to March 2022

Background

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) is undertaking a virtual engagement process to support an Act to establish a national diabetes framework, which received Royal Assent in June 2021. Through this process, a range of key stakeholders and Canadians connected to diabetes will have an opportunity to share their views, experiences and perspectives to help identify priorities for advancing efforts on diabetes in Canada, thereby informing the development of a framework. This work is being conducted with the assistance of the Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue, based at Simon Fraser University (SFU).

This process is made up of 2 phases. Phase 1 consists of key informant interviews. This report was independently prepared by SFU’s Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue to provide an overview and summary of the themes and content surfaced during these conversations. These findings will inform Phase 2 of the engagement process, in which additional stakeholders invested in addressing diabetes in Canada will be invited to attend virtual dialogue sessions.

This report does not provide an overall representation of general public opinion, institutional policies or positions, nor that of a randomly selected population sample. Rather, this report presents a summary of the views and ideas of key stakeholders related to diabetes in Canada. This report does not necessarily reflect the opinions of the SFU Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue, nor of PHAC.

Process

Dr. Diane Finegood and Dr. Lee Johnston (SFU Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue) conducted 32 interviews that included 50 individuals. While key informants were selected to represent a broad range of sectors, we acknowledge that this representation is incomplete. Phase 2 of the dialogue process will extend the breadth of PHAC’s consultation to include a wider array of voices.

The key informants interviewed represent a wide range of expertise related to diabetes, including:

- Persons living with type 1 or type 2 diabetes

- Specialists in areas such as endocrinology, nephrology, food and nutrition science, epidemiology, and pediatrics

- Representatives from non-profit organizations dedicated to supporting people living with diabetes (types 1 and 2) and obesity

- Clinician scientists and researchers with experience working in participatory, community-based settings

- Individuals and organizations working to promote healthy living, dietary change, physical activity and heart health

- Experts in health innovation and data collection/management for health improvement

- Representatives of foundations that support work to address diabetes and related conditions

- Private sector representatives with knowledge of diabetes drugs and technologies

- Researchers and clinicians with strong ties to marginalized and high-risk communities

It should be noted that while issues relevant to Canada’s Indigenous populations did surface during these interviews, formal consultations led by Indigenous organizations is being done in a different stream of work.

The interview contents were coded and then organized into key areas of focus relevant to diabetes. The following section presents summaries of the data as well as specific recommendations to address issues that emerged in each area.

Overview of findings

Towards a Framework

During the interviews, stakeholders shared their ideas and hopes for what approaches might be reflected in a framework for diabetes. Interviewees also identified the ways in which frameworks can prove beneficial for jurisdictions, especially smaller ones that lack access to resources such as local universities. Generally speaking, frameworks were identified as helping to “set the tone” in our approach to diabetes, providing good guidance, fostering network building across Canada, and highlighting best practices and approaches. It was also hoped the framework would help to raise the profile of diabetes as an urgent issue and a threat to Canada’s health care system.

It was suggested that the Framework:

- Take a long-term view on diabetes

- Take a developmental, learning systems approach that supports adaptation and continuous improvement

- Create opportunity for collaboration and meaningful, authentic dialogue and engagement between stakeholders facilitated by a backbone structure/organization. The Canadian Partnership Against Cancer was offered as an example.

- Be strategic in its approach and focus on priority areas (“don’t try and be everything to everyone”)

- Foster honest conversations about funding, sustainability and the efficacy of our responses to diabetes

- Provide strategies and practices that are flexible and enable local jurisdictions to adapt and adopt them

- “Set the tone” for using patient/people-first language, addressing stigma and recognizing obesity as a chronic disease

- Help to foster coordinated inter-provincial learning opportunities and to develop a cohesive vision for research projects and interventions across the country

- Help frame responsibility for diabetes and obesity as collective, and not merely individual, responsibilities

- Serve as a tool for health partners in supporting type 2 diabetes and obesity prevention initiatives at the provincial, territorial and health system levels

- Adequately address the needs of all types of diabetes while recognizing the distinctive differences between type 1 and type 2 diabetes

- Account for and tap into the many resources that already exist and help bring cohesion to the already in place

A framework enables system change to move in the right direction. I think provincial health systems are already moving there, there is a ground swell but the thing is, can that be accelerated with the right kind of framework that makes it go quicker and faster and be more aligned across the country?

System-wide themes

Several themes and/or concepts emerged as being relevant to diabetes at a systemic level. While some of this content pertains to other categories in our overview, we have highlighted them here to indicate their significance to participants.

Equity

The need to establish more equitable practices across the diabetes system was an overwhelming theme across many of our discussions. Areas of interest included addressing the social determinants of health (including food insecurity), increasing access to drugs and devices, and tailoring approaches and interventions to account for the needs of marginalized and priority populations. Stakeholders also pointed to the structural inequities that prevent marginalized and racialized populations from receiving adequate and compassionate care.

Centering people with diabetes

The need to centre the experiences and knowledge of individuals living with diabetes was emphasized as being essential across the system. Patients wish to be met where they are at and treated in a culturally appropriate and holistic manner that accounts for both pre-existing trauma and the psychological impacts of living with diabetes. Inherent in this was a move away from the “shame and blame” approach and stigma that people living with diabetes – type 2 in particular – feel exposed to on a regular basis. Interviewees also noted the need for meaningful and authentic engagement with a wide range of people with diabetes – not just those with the capacity to gain access to stakeholder tables. People with diabetes also noted that they sought to be taken seriously as participants in their own care and in research.

At a national context we really have to have infrastructure for stakeholders to share their perspectives in a way where they feel that they're authentically heard. So not that tokenistic engagement, which is what I think many of us have done for many years.

The post COVID-19 context

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and its implications for diabetes was a recurring theme across our interviews. Participants identified the many ways in which COVID-19 has impacted individuals’ health – both physical and mental. In regard to prevention, increased sedentary behaviour due to lockdowns, the loss of participation in regular social physical activities, and economic impacts were noted as potentially having long-term impacts that are just beginning to be understood. In the clinical care space, delays in screening and procedures will similarly have long-term consequences. Interviewees also noted the potential for positive outcomes from the pandemic, particularly in the area of telehealth and virtual care. Stakeholders agreed that the uncertainty associated with the pandemic of its short- and longer-term impacts will require consideration in our efforts to address diabetes moving forward.

The diabetes landscape in Canada: Issues and opportunities

A note about the sections below: we have identified common themes or important contexts in each section's introduction. The list of recommendations included in each section reflects a wide breadth of stakeholder input and does not necessarily reflect consensus opinion or order of priority.

Prevention

Stakeholders identified the strong need to focus on type 2 diabetes prevention given that its growth among an aging population could prove catastrophic for our health care system and people’s quality of life. However, the need for a shift in our thinking about prevention was also a strong theme across many interviews. The “eat less, move more” messaging of traditional lifestyle interventions was acknowledged as being largely ineffective and stigmatizing for many population groups. It was suggested that intervention need to account for lived realities regarding income, food insecurity, culture, gender, tradition and other factors that affect the ways in which individuals are affected by diabetes and are able to receive lifestyle intervention efforts. Participants also noted how important it was for professionals to be connected to the cultures and traditions of priority populations, such as the South-Asian population, should they wish to be effective.

Prevention is a huge conversation, and it's for the privileged. You can’t just tell everyone to adopt a Mediterranean diet.

Another theme was the need to support the scale up and spread of models of prevention that have been proven to be effective. These include evidence-based programs for systems change interventions and programs that offer behaviour change in a culturally appropriate manner that is realistic about working with people’s current lifestyles. Digital platforms, when well-designed, were also identified as an accessible, low-cost means of placing prevention education and motivation into the hands of more people.

The following priorities were identified by stakeholders in regard to prevention:

- Break down silos between chronic diseases with common risk factors

- Focus on systemically embedding and normalizing preventative measures for middle-aged to older adults

- Increase the profile of tobacco as a risk factor

- Promote a prevention focused approach to eliminating health inequities prioritizing the availability of healthy food and the accessibility of active community living

- Engage the disability community and adapt programs to meet their needs

- Recognize that active, healthy living means different things to different people

- Act on outstanding federal commitment re. front of package labeling, restricting marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages to children, and the development of an active transportation strategy

- Adopt a strengths-based approach to dietary change that taps into traditional diets and understands heterogeneity of cultural makeups (and where relevant, the intergenerational impacts of trauma)

- Train those in prevention about the problems with approaches that “shame and blame” the diets or lifestyle of specific communities

- Support emergent family and youth centered programs that allow for inter-generational learning and knowledge transfer

- Support the inclusion of people with diverse backgrounds in diabetes educator, peer support and other professional programs to increase a range of cultural knowledge and capacities in prevention efforts

- Recognize that physical activity extends beyond sports and should be the responsibility of ministries tied to families, active transportation and health

- Increase public awareness around the dangers of sedentary behaviour (and its association with screen time)

- Increase public awareness of the benefits of regular physical activity, which include mental health, improved sleep, prevention of cognitive decline, opportunities for socialization and overall improved quality of life; move the public away from the notion that physical activity is mainly for weight loss

- Make long-term, strategic investments in normalizing physical activity as part of everyday life for all Canadians; adopt an intersectional approach that accounts for gender, culture, disability and age

- Support the growth of low-barrier digital mobile health apps and better digital platforms so education can be provided in an engaging way

- Develop public education campaigns that demystify diabetes, address stigma, inform people about risk and highlight symptoms

Health care

Given the breadth of content discussed related to the care and management of diabetes, we have sub-divided this overview into specific areas of focus discussed by participants.

Health system

Participants identified several ways in which the current care structure poses challenges for effectively addressing chronic conditions like diabetes. The focus of our health care system around family physicians and general practitioners (GPs) was identified as being a poor match for diabetes, given the disease’s complexity and the need for specialized knowledge. The decline in GP availability has further exacerbated challenges as patients who rely on walk-in clinics are likely to experience less consistency in their care. Participants envisioned a system that shifts from episodic care to more consistent chronic disease management. The development of hubs and interdisciplinary care teams were also seen as an important means of addressing inequities for families and individuals needing to travel great distances or take time off of work to attend multiple specialist appointments.

Interviewees identified the following as ways of building the health care system’s capacity to address diabetes:

- Keep the focus on diabetes as a specific disease requiring specialized supports (don’t “dilute” into metabolic care centres, for example)

- Support interdisciplinary care teams that lessen the burden on patients (link to chronic disease management supports including dieticians, physiotherapists, kinesiologists, social workers, etc.)

- Expand integrated health centers that provide interdisciplinary care for rural populations and give nurses a greater role

- Collaborate with and create greater roles for non-profits who can support people with diabetes

- Foster connectivity between medical professionals and non-profits invested in diabetes and healthy, active living

- Expand the roles of nurses, pharmacists and other professionals who can serve as diabetes specialists

- Extend the availability of online certified diabetes education programs

- Develop strategies to address the ongoing loss of medical professionals to retirement and the private sector

- Work to improve communication between primary care, specialist care and allied health professionals

- Consider alternative funding models (e.g. dollar follows the patient, not the services; private sector takes on risk; private insurers running public programs; social impact bonds; outcomes-based payment programs)

Delivery of care

In regard to care delivery, clinicians and other stakeholder pointed to areas for helping improve clinical practice, including the development of standardized best practices and increasing the utility of Canada’s clinical practice guidelines – seen as being of excellent quality but overwhelming in their scope. Another significant theme was the important gains made in virtual and tele-health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stakeholders noted the transformational potential for virtual care to increase access, particularly for remote communities, provided that gaps in necessary infrastructure supports were also addressed.

The following specific areas of focus were identified in regard to diabetes care delivery:

- Identify and develop best practices for treating complex priority populations with limited access to primary care (including the unhoused and substance users)

- Identify national standards of care to be adapted and implemented locally

- Expand virtual care of various types including care provider visits, web-based management tools, and peer support

- Accelerate the access to internet pledge of the Federal Government

- Scale up and implement advancements in remote technologies

- Identify and support a standardized guideline development group

- Align clinical practice guidelines more with physician needs and priorities

- Extend supports for transitioning out of youth care for type 1 diabetes into adulthood, when many supports are lost

- Develop a national diabetes education program – a gold standard for coaching

- Develop a centralized, valid source of information on diabetes (stop re-inventing the wheel) with customizable and culturally appropriate educational materials that can be adapted to the local level

Patient support

There’s the theory of how to manage your diabetes that the doctors give you, and there’s the reality of doing it.

Interviewees, including individuals living with diabetes, identified the expert role that patients can play in the self-management of their disease, and the importance of engaging in shared decision-making with their health care providers. However, it was also noted that the “burden” of self-management should not be shifted entirely onto patients without adequate supports, which has traditionally resulted in exacerbating inequities between the well-resourced and those without.

Stakeholders recommended the following related to these and other areas of patient support:

- Develop and provide support for self-management through peer-to-peer support, access to credible/trusted information in a variety of languages, better access to data visualization, and patient-centered online programs

- Ensure the necessary infrastructure is in place to educate patients on how to work with new technologies such as pumps and closed-loop, continuous glucose monitoring systems

- Expand the development of tools that assist with patient-doctor communications around diabetes (including innovation in apps, patient facing clinical practice guidelines, etc.)

- Acknowledge the diversity and uniqueness of how different patients experience and live with diabetes

- Remove GPs as gatekeepers for blood testing, enabling patients to better monitor their own health

- Acknowledge the psychological impacts of diabetes management on mental health and normalize the provision of support

- Identify effective approaches to assisting those with mental health issues (and their caregivers, where applicable) with diabetes self-management

- Provide system navigators, particularly for newcomers to Canada

- Provide anti-racism training for medical personnel and education around shame and blame

- Provide quality advice as to how to incorporate activity (like sports) into your life as a person with diabetes – find solutions to encourage active living

- Create specialized education centres tailored to the different needs of patients with type 1 and

- Provide more education for women regarding gestational diabetes (ex. postpartum effects on glucose monitoring w closed loop systems)

Screening

Interviewees identified the following priorities in regard to improving diabetes-related screening within Canada:

- Provide universal childhood screening for type 1 diabetes as therapies are being developed that may delay onset

- Create a coordinated system for monitoring that provides information on screening and treatment

- Replicate cancer prevention screening; coordinate amongst provinces (note: it was also suggested that cancer-relevant models may not be appropriate for diabetes screening)

- Implement adequate screening for the range of complications associated with diabetes

- Implement systems to screen for pre-diabetes

Obesity

Several stakeholders noted the importance of including obesity in the framework given its close association with diabetes. Participants were also keenly aware as to how carefully the inclusion of obesity in a framework needs to be handled, given the stigma and shame that public health efforts can foster in this area. We have included obesity under health care as this is where most of its discussion was centered.

We need to move people into an empathy space regarding obesity.

The following priorities were identified by stakeholders in regard to obesity:

- Acknowledge obesity as a significant risk factor for type 2 diabetes

- Incorporate up to date definitions of obesity and its classification as a chronic disease

- Share the most up-to-date knowledge and practices for diagnosing and treating obesity

- Provide coverage for anti-obesity medications

- Address bias towards obesity

- Provide support for education for medical professionals in treating obesity (beyond telling patients to lose weight)

- Provide treatment/management systems that include frequent touch points, a key component of supporting lasting behaviour change

Access to drugs, devices and financial supports

The patchwork nature of drug and device coverage across Canada – and the stress and inequity it causes – was a common theme across various stakeholders. The disability tax credit (DTC) was also frequently identified as being poorly designed and neither patient nor physician friendly, and of no use to low-income individuals with diabetes given its design as a non-refundable tax credit.

The following points were made in regard to addressing access to drug, devices and financial supports:

- Shift funder thinking away from unit model costs to longer term quality of life metrics

- Create more equitable access/ coverage for drugs and devices through collaboration across Federal, Provincial and Territorial governments

- Enable new business models incentivized by outcomes and value instead of cost

- Accelerate the pace of federal approval for technology and medications

- Apply a holistic approach to financial supports and engage patients in their design

- Provide patients with choice in regard to new technologies

- Redesign the DTC as a refundable tax credit, based-on the diagnosis of diabetes as sole criteria

Data

While stakeholders identified multiple paths forward to addressing issues around data, one theme was common the need to overcome barriers in our currently fragmented system and enhance system integration so as to meet the needs of health care professionals, patients and researchers. It was recognized that different types of data are needed including administrative data, data from electronic medical records, repository and registry data. A related theme was the need to expand the scope of current data collection to identify and enable solutions to inequities in service and care. Interviewees also pointed out the well-known barriers to data sharing and some stakeholders suggested that diabetes could provide a proof of concept for data sharing across the provinces and between those who provide and receive care.

The following needs and opportunities were identified in relation to data on diabetes:

- Integrate electronic medical records with clinical practice guidelines and evidence-based recommendations for screening and care to improve patient outcomes

- Scale up current repositories of electronic medical records that could provide new insights including into prevalence and uptake of technologies; patient-reported outcome and experiences; social-demographic information; pediatric diabetes

- Expand on current registries of people with diabetes that allow them to control their own data and decide who can see and use their data to support self-management, care and research

- Beyond data collection, use data to identify patterns, address inequities, clarify the health economics of diabetes in Canada and inform policy-making, quality improvement, and resource allocation

- Develop publicly available and transparent dashboards or other methods to enable provincial territorial comparisons

- Adopt a citizen-science approach that incentivizes patient involvement, communicates the value of data sharing to inform research and health care quality, and offers security and the opportunity to withdraw one's data at any time

- Provide surveillance data at a more local, granular level

- Support and consult with projects already underway to increase data linkages nationally

- Provide assistance to jurisdictions lacking capacity to analyze their own data

- Investigate the development of interactive apps that integrate data into clinical care and self-management, and can link to a central repository and/or feed into administrative data sets

- Build collaborative efforts to share best practices in handling, using and securing data.

Research and innovation

Stakeholders frequently referred to Canada’s reputation as a “nation of pilot projects” when discussing their diabetes research and the mechanisms in place to support it. Scientists expressed frustration at having to expend significant resources and energy applying for research funding for new projects when already successful interventions were left unsupported. They desired a research support model that “funds and follows” through support for scale-up and spread, rather than the current system that “funds and forgets.” Participants also noted the ingenuity and passion of this generation’s innovative researchers, some of whom are connected to racialized communities who have previously been excluded from research efforts. Integrating their knowledge and expertise into research and innovation efforts was identified as a key means of addressing the higher rates of diabetes present in sub-populations. Participants also expressed concern that Canada has fallen behind in supporting innovation and pointed to the need to streamline approval processes.

The following suggestions were made in relation to research and innovation:

- Embrace funding models that are flexible, allow for risk, provide time to develop relationships and partnerships, and are more easily accommodating of interdisciplinary approaches

- Support implementation research and research that takes a learning health systems approach

- Identify the successful work that is already being done to innovate in priority populations and scale-up from there

- Fund research on the implementation of interventions that will address mental health and the psychological impacts of diabetes

- Include people with diabetes as active participants in the development and implementation of research (not just as consultants)

- Support community-based research programs that engage local stakeholders

- Tap into the innovation of research professionals with lived cultural experience and knowledge of the Canadian system

- Focus research funding on societal impacts and not research impacts (such as publications)

- Develop mechanisms and/or a database so researchers can know what others are doing across the country

- Hasten the approval process for innovative technologies; the speed of technological innovations in diabetes care is outpacing Canada’s the regulatory environment

- Build infrastructure that anticipates and supports the uptake and use of rapid tech advances in diabetes care

Indigenous peoples and diabetes

As noted above, although issues relevant to Canada’s Indigenous Peoples did surface during these interviews, consultations led by Indigenous organizations are being done under a different contract with the Public Health Agency of Canada. What follows is what we heard from the key informants who participated in this initial set of interviews, including both Indigenous and non-indigenous identifying individuals.

Equity was top of mind for most informants. Equitable access to culturally safe, high-quality care located in community settings was a priority for many. The impacts of colonialism and racism on poverty, trauma and health are clear and with us today. Diabetes care and support needs to be trauma informed and take a strengths- based approach which builds upon the skills, strengths and capacity of individuals and communities. Ending poverty and supporting workforce development were seen as important to building equity and addressing diabetes.

If you're going to grow healthy people you're going to have to give the same access or more, dependent on needs. You're not looking at equal access you're looking at equity.

More care is needed in community. Informants told stories of needing to travel long distances to access care and support. This meant significant time away from both family and community, which is especially difficult for the most vulnerable, both in the young and those near the end of life. We also heard about the need for Indigenous organizations to set up their own vaccination centres because "people were more comfortable with that."

We were told communities have the knowledge to support themselves but they need the resources and capacity to do this work. This was connected to the need to expand (not narrow) the scope of practice for health care workers in community, to train more Indigenous healthcare providers and to deepen their knowledge about diabetes prevention, screening and care. Also, in this regard we heard calls to expand telehealth capabilities so people affected by diabetes can receive care at home and in community. Expanding telehealth was also connected to the need to improve internet access in rural and remote communities.

The health research system in Canada has supported some work on data sovereignty and self-governance, and adaptation of community-led, evidence-based approaches in rural, remote and Indigenous cultural contexts. Unfortunately, research project-based funding is often not community-led and it comes and goes, making it difficult to sustain meaningful system change. Insufficient data collection and surveillance was also cited as a problem, as was the fact that our system doesn’t change in response to the needs identified when data is collected (see for example, the identified need for widespread screening).

A number of respondents indicated that a life course approach is needed. The system needs to recognize all aspects of an individual's journey which supports wellness and helps to prevent diabetes, starting pre- conception, through gestation and along the many phases of life are important touch points for wellness, diabetes prevention and care. Diabetes is appearing more frequently and in younger Indigenous people. Education and screening need to be more widespread and at a younger age; we know early screening for complications is more efficient and effective, but implementation is not widespread.

We heard about the need for other strengths-based approaches such as supporting food security and food sovereignty. In regard to behaviour change, the "eat less, move more" messaging is stigmatizing and does not help to create non-judgmental environments that support health and wellbeing. People need care support where they are at, whether it is an HbA1C of 7 to 9, 11 to 12 or higher.

Lastly, many interviewees described the need for an Indigenous-led strategy to address diabetes. The need for self-governance and a nation to nation approach was also emphasized by some informants.

Appendix II: What we heard report (dialogues)

Table of contents

Overview

Context

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) is undertaking a virtual engagement process to support An Act to Establish a Diabetes Framework, which received Royal Assent in June 2021.

The process for engagement has taken several forms including key informant interviews, stakeholder dialogues, and an online survey where stakeholders were invited to share their ideas and priorities to improve the lives of people affected by diabetes.

Process

This report summarizes what we heard during the virtual dialogues co-hosted with the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) on April 7 and April 12 of 2022. Nearly 300 stakeholders were invited to register for 1 of 2 dialogues, depending on language preference and availability.

In advance of the sessions, registered participants received a report that summarized the findings from the previous key informant interviews, as well as a discussion guide for the dialogues based on what we heard in the interviews (see Appendix). In the key informant interviews, a range of stakeholders and Canadians affected by diabetes shared their views, experiences and perspectives to help identify priorities for advancing efforts on diabetes in Canada in one-on-one and focus group interviews. 33 interviews were conducted with over 50 stakeholders. The findings from the key informant interviews were shared in a report to registered participants of the April 7 and April 12 dialogues. Dialogue participants were asked to review the discussion guide for topics of interest and to reflect on which of the suggested actions were a priority for them.

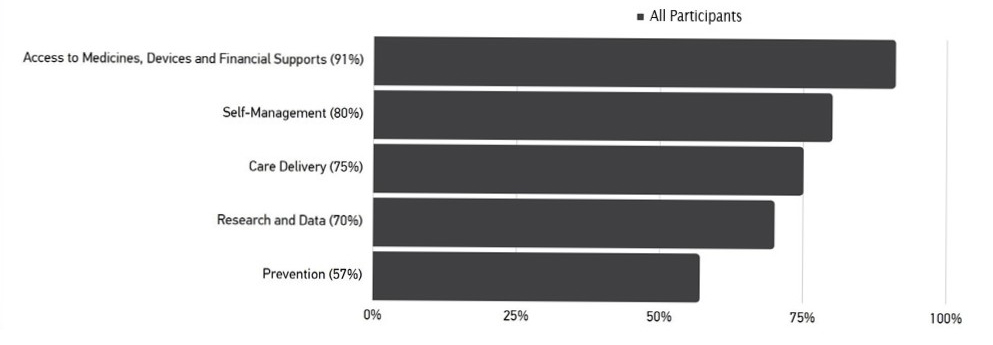

The English only dialogue held on April 7 was structured around 2 rounds of breakout discussions, initially based on system-wide themes including: Inequity, Stigma, Types of Diabetes, Collaboration and Capacity. The second set of breakouts tackled system specific themes including: Prevention, Care delivery, Self-management, Research and data, and Access to medicines, devices and financial supports.

Breakouts had pre-assigned Facilitators, Notetakers and Witnesses. Participants selected the themed breakout room of their choice. The Witnesses were asked in advance to serve as deep listeners and to participate in a panel discussion following the breakouts. Panelists spoke about what they heard and what surprised them. The Notetaker records provided the basis for this report. The April 7 English dialogue had 101 registered participants, with 76 present on the day of the session.

The French dialogue held on April 12 also explored these same themes. Since this was a smaller group than the English dialogue, participants conversed together as one group rather than in breakout rooms. This dialogue had 13 registered participants with 8 participants present on the day of the session.

For the purpose of this report contents from the English and French dialogues have been synthesized.

Both events were 3 hours in length, hosted on the Zoom platform and were facilitated by teams from SFU’s Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue.

About this what we heard report

This “What We Heard” Report is intended to provide an overview and summary of participants’ ideas that surfaced during the 2 dialogues. These ideas were gleaned from notetaker notes and the post-forum evaluation survey which was administered via SurveyMonkey at the end of each dialogue. SFU’s team analyzed this material and organized it thematically. After the 2 dialogue sessions, participants also received a separate invitation to participate in a survey administered through the platform Ethelo. The findings of that survey are not included in this “What We Heard” report.

All feedback was compiled and analyzed without attribution to protect participants’ privacy and to encourage participation. The report does not provide an overall representation of public opinion, institutional policies or positions, nor that of a randomly selected population sample. Rather, this report presents a summary of our analysis of the ideas expressed by the people who participated in these dialogues.

The report was independently prepared by Drs. Lee Johnston and Diane Finegood from SFU’s Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue. The report does not necessarily reflect the opinions of the SFU Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue, the University at-large, nor of the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Summary

“Collaboration truly requires conversation.”

Many of the themes and areas of focus that emerged from the prior round of key interviews resonated strongly with the dialogue participants who attended these sessions. Improving access to drugs and medications was a predominant concern throughout the engagement process. The need to centre patients within systems was another overarching theme. People living with diabetes want to be provided with the tools, education, support and resources necessary to empower them as leaders and partners in research, community-led collaborative efforts, intervention design and implementation, and in the management of their own care. Stigma was recognized as having both psychological and physiological impacts on people living with diabetes, particularly when it entered into their relationships with their health care providers.

Participants also echoed previous recommendations as to how systems need to be restructured to better support diabetes treatment, prevention and self-management. Particular areas of recommendation include building out roles for diabetes education and treatment throughout the health care system, fostering inter- jurisdictional knowledge exchange about successful interventions, creating knowledge hubs, and evaluation of the indicators and outcomes that are most important to diabetes care. Providing opportunities for ongoing engagement in support of the framework and its implementation was also emphasized by dialogue participants.

Participants also identified gaps in the themes that were brought forward in the dialogues and helped to further unpack the complexities of diabetes. We heard about the intersections of race, age, and disability with diabetes prevention, care and access. People warned of the dangers of speaking of “diabetes” in umbrella terms without acknowledging the distinctions between types of diabetes and the needs specific to living with type 1. They raised concern about the erasure of the unique challenges faced by living with this acute condition 24/7, 365 days a year. The challenge of diabetes management, and its associated mental load – particularly for young people – was highlighted. Engaging with youth and providing better support for those transitioning out of pediatric care were identified as priorities, as was the regular and consistent commitment to finding a cure for type 1 diabetes.

Participants from racialized and Indigenous communities spoke to the need to explicitly name racism and colonialism as factors helping to drive diabetes rates in high priority populations. A related focus of discussion was the need to embed conversations about prevention and self-management in discussions about broader public policy and the barriers they create for both. Participants urged policy-makers and the medical system to avoid thinking about diabetes in isolation and to consider its intersectionality both medically (with other chronic or mental health conditions) or socially (with characteristics such as race, disability, age, etc.). More consideration is needed for the visually impaired, given the impact that blindness has in complicating diabetes self-management. Attendees also called not just for meaningful engagement with individuals living with diabetes, but the recognition of how priority populations and communities can assume leadership based on their knowledge of their communities and their needs.

Key themes

1. Discussion 1: System-wide challenges

In Discussion 1 of the dialogues, participants were asked to select a system wide theme that was particularly meaningful to them and engage in dialogue guided by questions included in the discussion guide. Below are the key themes that came out of the discussions on each system wide challenge.

1.1 Inequities

“We need to view diabetes, and the people who have it, with an equity lens.”

The breakout discussion on inequities reinforced several of the themes that emerged during the key informant interviews, including the broader need to address the upstream elements that determine people’s ability to support their own health, such as stable healthy food sources, safe homes/available housing, and income. The need to center persons living with diabetes across the system and adopt an approach that respects boundaries, listens to needs, and does not contribute to a shame and blame approach was also reinforced as central to planning around diabetes. As in previous stakeholder consultations, participants requested that the disability tax credit be automatically granted to persons with diabetes and that “arbitrary and illogical” requirements be suspended.

Some participants also emphasized the importance of moving beyond discussions of inclusion and meaningful engagement – with persons with diabetes positioned as consultants – and towards adopting an intersectional approach led by systemically oppressed communities, including Indigenous, black, South Asian and disabled groups. Representatives of these populations talked about the importance of having interventions designed by and for the community, created by individuals with lived experience and knowledge of their communities’ unique needs. This was situated within a broader conversation about the need to address systemic racism throughout the systems that service individuals with diabetes, and a dialogue about the limitations of encouraging individual self-management in this context, a theme that overlapped with discussions on prevention and self-management. One participant encouraged the dialogue organizers and participants to reflect on their own make-up and consider what was lacking there in terms of representation.

In addition to these conversations, the following points/recommendations were also made during the dialogue on inclusion:

- Acknowledge and address the inequities distinctions that occur between type 1 and 2 diabetes (see also the section on distinctions between types of diabetes)

- Individuals with type 1 are at a higher risk of mental illness and suicide, and physicians should take seriously how the mental stress (burnout, isolation, etc.) affects physical health; more research is needed in this area

- Build anti-oppression and disability justice into the work and ensure under-represented voices are being heard within organizations

- Examine and address the inequities that are prevalent in diabetes-related complications (for example, lower limb amputations and mortality have higher rates in some populations/groups)

- Address discrimination based on age/disease subtypes (and consider important intersection that occurs with ages and stages)

- Consider regional inequities; not just the differences between rural and urban areas, but also those between neighbourhoods in urban and suburban areas

- Improve cultural equity; many people need healthcare resources that are culturally relevant and it is therefore useful to engage with community organizations to enrich learning and carry out prevention in other languages beyond French and English

- Increase accessibility to devices and treatments

- There are limited options for visually impaired individuals (insulin pumps, for example, are not accessible)

- A disability lens needs to be placed on diabetes; there are no glucometers or insulin pumps that a blind person can use, therefore they lose their independence and need sighted help; some equipment is only partially accessible to them

- Devices/medicine should be universal; barriers of age, province, socio-economic status and insurance status should not get in the way of access to essential/lifesaving care

- Provide more investments for the less privileged and a framework that covers individuals across their lifespan (for example, there is a 25% higher chance of diabetes development in Indigenous children and type 2 is on the rise)

- Review service provision through a lens of equity rather than equality; allocate resources where they are most needed to help individuals thrive with less support

- Review research and evidence-based care to evaluate if what is being funding really makes a difference; consider the types of insulin/medications being used – some aren’t making a noticeable difference in addressing blindness or heart attacks, for example

- Provide more social supports and policy changes (every individual should be assigned a social worker)

- Change screening practices for those at high risk; many are placed at risk through policies and not their race

- Produce a diabetes report much like the Truth and Reconciliation report, where we acknowledge the inequities that exist, and firmly state that all Canadians should be entitled to care no matter where they live; understand and document the problem before making solutions

- Consider the unintended consequences of blunt policy changes (for example, taxes that can be regressive on the poor)

“Many biological/socioeconomic factors aren’t in diabetes patients’ control. There are many interconnected/overlapping barriers for them, like financial barriers for immigrants, the homeless and minorities. Policies need to be structured so that people with diabetes can take care of themselves.”

1.2 Stigma

“Stigma can come from words, impressions, images, attitudes, but also clinical practices that we undertake perhaps without even thinking about how they make the client feel.”

The issue of stigma resonated strongly with many dialogue participants, particularly those with type 2 diabetes. Individuals spoke of being stigmatized every day and in every sphere of their lives – at work, school and in the health care system. Dialogue attendees urged public health to examine its own narratives around diabetes and consider how they might be contributing to stigma around the disease. While some participants noted a role for prevention education in helping people make healthier choices that personally suit them, they also spoke to the failure of traditional health practices perpetuating inequities identified in the previous section.

Shame and blame were also noted as contributors to breaking down trust in patient-clinician relationships, and its potential to push patients to disengage and have worse outcomes. One participant noted that stigma is still embedded in the health care system as patients may feel as if there is something innately wrong with them and they need to live up to the expectations of health care providers. Having to repeatedly recount their health issues in relation to diabetes was also identified as creating distance between themselves and medical professionals; it was suggested that better training and information systems could lessen this load and improve patient-doctor relations. Individuals called for approaches that encourage self-efficacy while reducing feelings of judgement, shame and discomfort. Education about diabetes – both targeted to professionals and more generally to the public – was put forward as a way of reducing the trauma associated with being shamed and blamed by professionals and members of support systems. As one participant noted, “education can help address fear of the unknown.”

In addition to these themes, the following was noted in relation to stigma:

- Help clinicians to adopt a patient-first approach that put the patient in the driver’s seat; emphasize treatment collaboration:

- Ask why patients are there and for their perspective on the issue instead of immediately focusing on checking charts and conducting routine activities

- Emphasize collaboration toward health and progress and stress importance on the value of health objectives rather than numerical numbers like on a scale or glucometer

- Patients know their own body the most and what works for them, so clinicians should always take that into account when discussing their health

- Promote a collective response to chronic disease (by society and health care practitioners) rather than a focus on those with diabetes or perceived to be at-risk

- Include people with diabetes when writing government reports, medical guidelines, prevention and awareness campaigns, etc.

- Implement education at a wider scale in different institutions (beyond healthcare) to help those with little health care experience or knowledge of diabetes better approach those who have it

- Actively discourage disrespectful language or notions about diabetes

- Separate the approach within healthcare for Indigenous peoples, who live with chronic and generational problems that stem from colonization; addressing barriers that mitigate Indigenous people receiving proper health care (institutionalized racism)

- Educate people on diabetes early on so they are taught actual implications and facts about the condition rather than biased narratives

- Respect patient values and listen to their lived experiences; understand that each patient is different and requires individualized approach

1.3 Types of diabetes

The type 1 diabetes community resoundingly expressed the need to distinguish between the unique needs of type 1 and type 2 patients in a diabetes framework. They noted that type 1 diabetes in an acute life-or-death disease that requires more direct and frequent access to medical specialists and constant adjustment of their medication with insufficient professional support, placing a significant mental burden on patients and the people they live with. People living with type 1 diabetes noted that it can take too long to access endocrinologists, and that other health professionals often do not have the expertise needed to adequately help with diabetes management. Individuals with type 1 diabetes also did not see themselves as part of the prevention conversation and expressed concern about the lack of focus on finding a cure for type 1. Type 1 patients also noted the negatives effects of dealing with a healthcare system more experienced in dealing with type 2 and called for education regarding the differences between them. They suggested that the focus on type 2 was reinforced by media and stakeholder emphasis and the perception that’s it’s just a “blood sugar disease.” It was also noted that we should move beyond the perception of “juvenile” diabetes, given that adults do get type 1 diabetes and children get type 2.

Another key theme during this breakout conversation was that age and stage are important in providing the right care at the right time based on diabetes type. Participants also rearticulated the intense challenges that occurs with the transition from pediatric to adult care for type 1 patients, at which point patients can lose access to a range of supports and clinical care. Individuals also spoke to how difficult this shift is for families as parents and children navigate a shift in their responsibilities for diabetes management. As one participant noted, type 1 diabetes is in many respects a “family disease.” Concern was also expressed that the focus tends to be on the adult experience of type 1 diabetes and its associated complications (such as limb amputations and blindness); children are often left out on the sidelines.

The following was discussed in relation to the types of diabetes:

- Personalize care and prevention according to risk associated with different diabetes types

- Respect choices about medication/devices/services so individuals have all the tools available to get the best health outcomes; this differs vastly across the country

- Consider how we conduct risk assessment regarding the social determinants of health (for example, geography/access to care/structural inequities/racialization)

- Challenge the belief that type 2 diabetes is easy to manage and the responsibility of primary care; specialists should be involved in all types of diabetes

- Address issues related to diagnosis (currently the same for all types of diabetes; such as sugar/glucose level)

- Advocate for research and efforts on how to diagnose diabetes

- Modify how we define diabetes and diagnostic guidelines

- Explore opportunities to implement technologies and evidence-based decision-making tools (not just guidelines) for practitioners related to different types of diabetes