Lyme disease surveillance in Canada: Annual edition 2020

Download in PDF format

(765 KB, 11 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2023-07-11

On this page

- Surveillance highlights 2020

- Introduction

- Methods

- Results

- Discussion

- Public health conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- References

Surveillance highlights 2020

- A total of 1,617 human cases of Lyme disease were reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada between January 1, 2020 and December 31, 2020, of which, 1,204 (74%) were confirmed cases and 413 (26%) probable cases.

- Incidence peaked in adults aged 65–79 years (25% of cases) and children aged 5–9 years (8% of cases) with a predominance in males.

- 26% of cases reported an illness onset in July.

- 96% of cases were reported in Ontario, Québec and Nova Scotia.

- Less than 1% of reported cases were likely infected during travel outside of Canada.

Introduction

Vector-borne diseases are infectious diseases caused by bacteria, viruses and parasites that are transmitted to humans from animals and/or insects. Lyme disease is the most commonly reported vector-borne disease in Canada. Lyme disease is a bacterial infection caused by Borrelia burgdorferi and transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected tick; the blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis, in Manitoba, central and eastern Canada and the western blacklegged tick, Ixodes pacificus, in British Columbia. In Alberta and Saskatchewan, no known endemic areas of blacklegged tick populations have been identified (1, 2). The ticks become infected after feeding on infected small mammals and birds.

Lyme disease can cause a range of clinical manifestations in humans. In the early stage of disease, flu-like symptoms, including joint pain, and erythema migrans rash are common. If untreated, individuals may experience cardiac, neurologic, and musculoskeletal manifestations such as arthritis. Over the past decade, there has been an increase in the number of locally acquired Lyme disease cases. This occurred in part due to changes in climate, which has contributed to increases in the abundance and geographic range of blacklegged tick populations in central and eastern Canada. Surveillance for ticks and human Lyme disease cases are conducted using a "One Health" approach to minimize the burden of Lyme disease and other emerging tick-borne diseases and protect the health of Canadians. This report focuses on the human component of the Lyme disease surveillance program, by providing an overview of surveillance data on cases reported between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2020.

Methods

Since becoming nationally notifiable in 2009, human cases of Lyme disease in Canada have been reported voluntarily to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) by provincial/territorial health ministries/agencies through the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (CNDSS). Information collected through CNDSS include age, sex, and case classification (probable and confirmed cases). In 2011, in collaboration with provincial and territorial partners, PHAC developed and implemented the Lyme Disease Enhanced Surveillance (LDES) system whereby participating jurisdictions (eight provinces in 2020) report information in addition to what is collected by the CNDSS, including information on geographic location of infection acquisition, clinical features and laboratory results (3). Data obtained from provincial/territorial notifiable disease systems represent a snapshot at the time of data extraction and may differ from previous/subsequent reports, data displayed by provincial health authorities and from CNDSS. Lyme disease cases reported to PHAC are classified using the national Lyme disease 2016 case definition (3).

Results

Change in incidence over time

In 2020, 1,617 cases of Lyme disease including locally-acquired and travel related cases were reported in Canada. Of these, 1,204 (74.5%) were confirmed and 413 (25.5%) were probable cases. Although there was a 39% drop in the number of total Lyme disease cases reported in 2020 compared to the previous year (incidence of 4.3 compared to 7.0 per 100,000 population, respectively), there has been an overall upward trend in this number since 2010 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Text equivalent

This is a bar chart with vertical bars showing the number of cases reported in each year, from left to right, from 2010 to 2020. The pink filled bars show the total number of cases reported each from 2010 to 2020. Above the filled bars is a black marker that displays the incidence per 100,000 population over each year from 2010 to 2020. The number of cases and incidence per year are detailed in the following table:

| Year | Number of cases | Incidence per 100,000 population |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 143 | 0.4 |

| 2011 | 266 | 0.8 |

| 2012 | 338 | 1.0 |

| 2013 | 682 | 1.9 |

| 2014 | 522 | 1.5 |

| 2015 | 917 | 2.6 |

| 2016 | 992 | 2.7 |

| 2017 | 2,025 | 5.5 |

| 2018 | 1,487 | 4.0 |

| 2019 | 2,634 | 7.0 |

| 2020 | 1,617 | 4.3 |

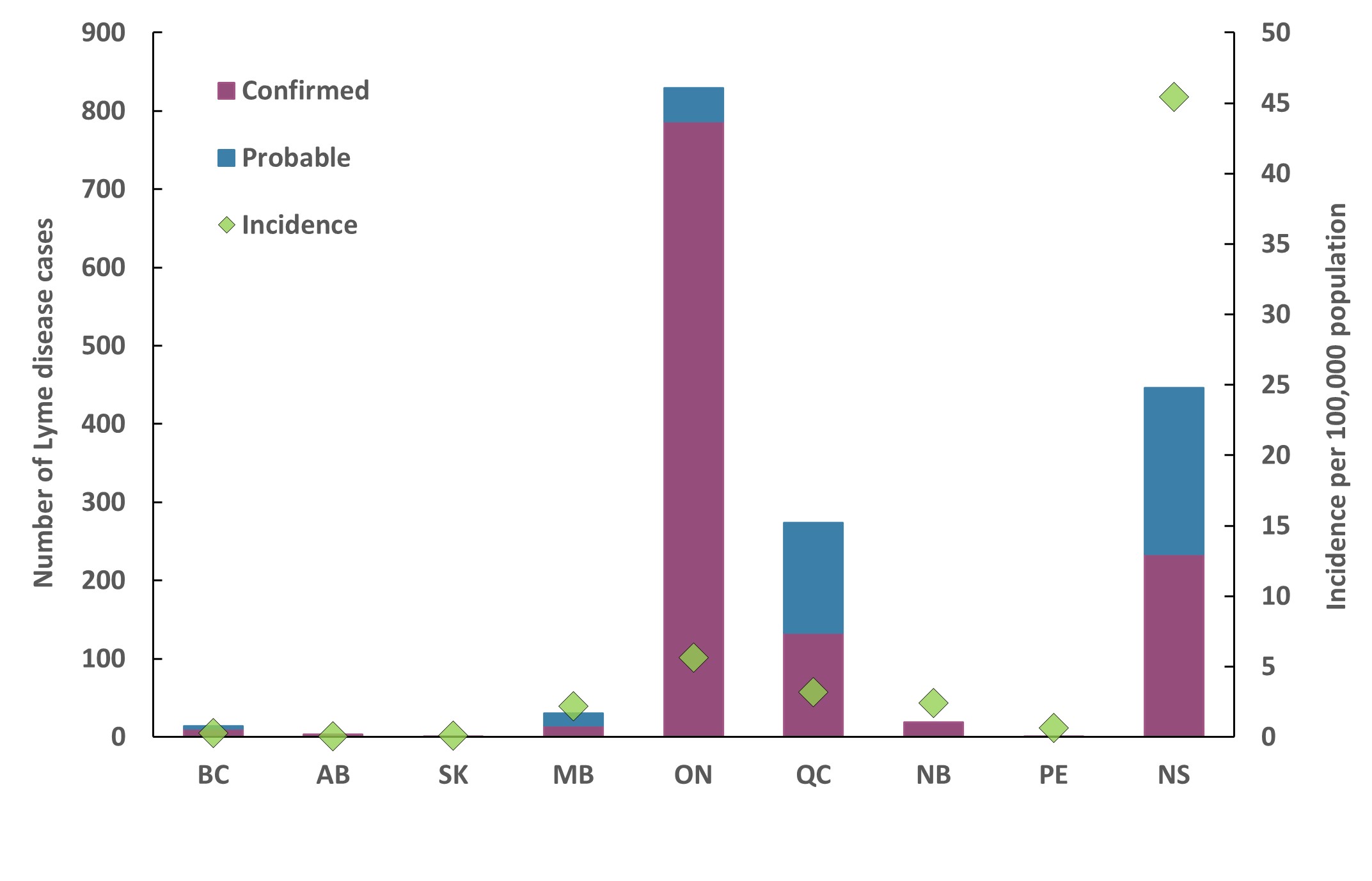

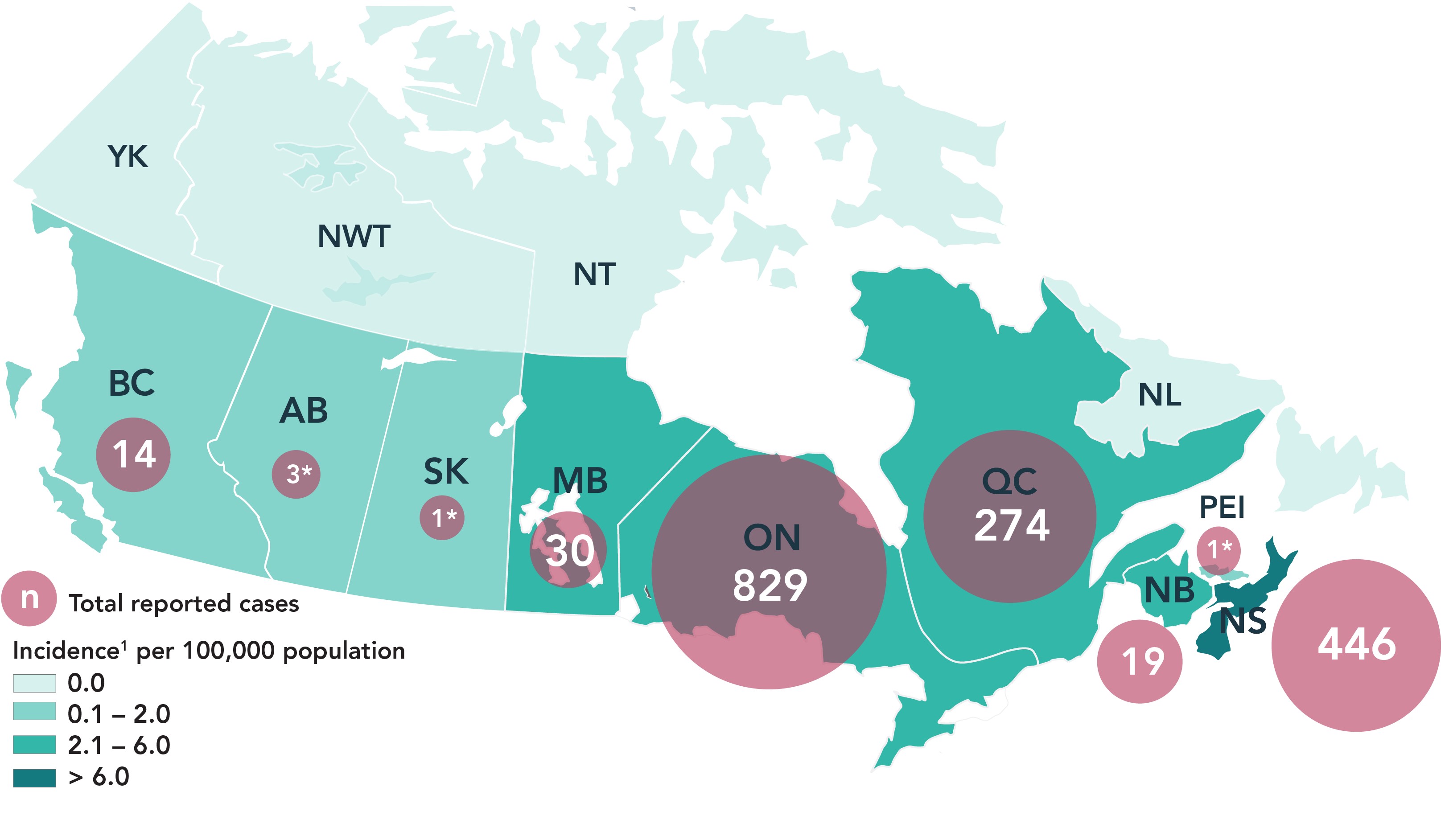

Geographic distribution

As in 2019, the majority of all cases (95.8%) were reported from Ontario (n=829), Nova Scotia (n=446) and Québec (n=274) (Figure 2). The province with the highest incidence per 100,000 population was Nova Scotia (45.4 per 100,000 population) which is nearly 11-folds greater than the national incidence (4.3 per 100,000 population).

Figure 2 - Text equivalent

Abbreviations: BC, British Columbia; AB, Alberta; SK, Saskatchewan; MB, Manitoba; ON, Ontario; QC, Quebec; NB, New Brunswick; PE, Prince Edward Island; NS, Nova Scotia

Notes: Probable cases are not reported in Saskatchewan. Cases reported by Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan, and Alberta were travel-related only. No cases have been reported by Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut and Newfoundland & Labrador for 2020.

This figure is a stacked bar graph with pink filled bars showing the number of confirmed cases and probable (teal) Lyme disease cases reported by each province (from left to right, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia). The black diamonds show the incidence of the disease in each province. The numbers of cases and incidence per province are detailed in the following table:

| Province / territory | Cases – confirmed | Cases – probable | Total | Incidence per 100,000 population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 11 | 3 | 14 | 0.27 |

| Alberta | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.07 |

| Saskatchewan | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.08 |

| Manitoba | 15 | 15 | 30 | 2.17 |

| Ontario | 787 | 42 | 829 | 5.63 |

| Québec | 133 | 141 | 274 | 3.19 |

| New Brunswick | 19 | 0 | 19 | 2.43 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.62 |

| Nova Scotia | 232 | 212 | 446 | 45.23 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yukon | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Northwest Territories | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nunavut | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

*Cases reported by AB, SK, and PE were travel-related only

Figure 3 - Text equivalent

| Province / territory | Total reported cases | Incidence per 100,000 population |

|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 14 | 0.27 |

| Alberta | 3 | 0.07 |

| Saskatchewan | 1 | 0.08 |

| Manitoba | 30 | 2.17 |

| Ontario | 829 | 5.63 |

| Québec | 274 | 3.19 |

| New Brunswick | 19 | 2.43 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1 | 0.62 |

| Nova Scotia | 446 | 45.23 |

| *Cases reported by AB, SK, and PE were travel-related only | ||

Travel−related cases

Lyme disease is commonly acquired in areas of Canada where blacklegged tick populations are established (i.e., at-risk areas) or through travel to countries where the disease is endemic. In 2020, information about travel history was available for 1,339 Lyme disease cases (82.8%). Of these, 11 Lyme disease cases (0.8%) were likely infected during travel outside of Canada to the USA (n=4), Europe (n=6) or unidentified locations (n=1).

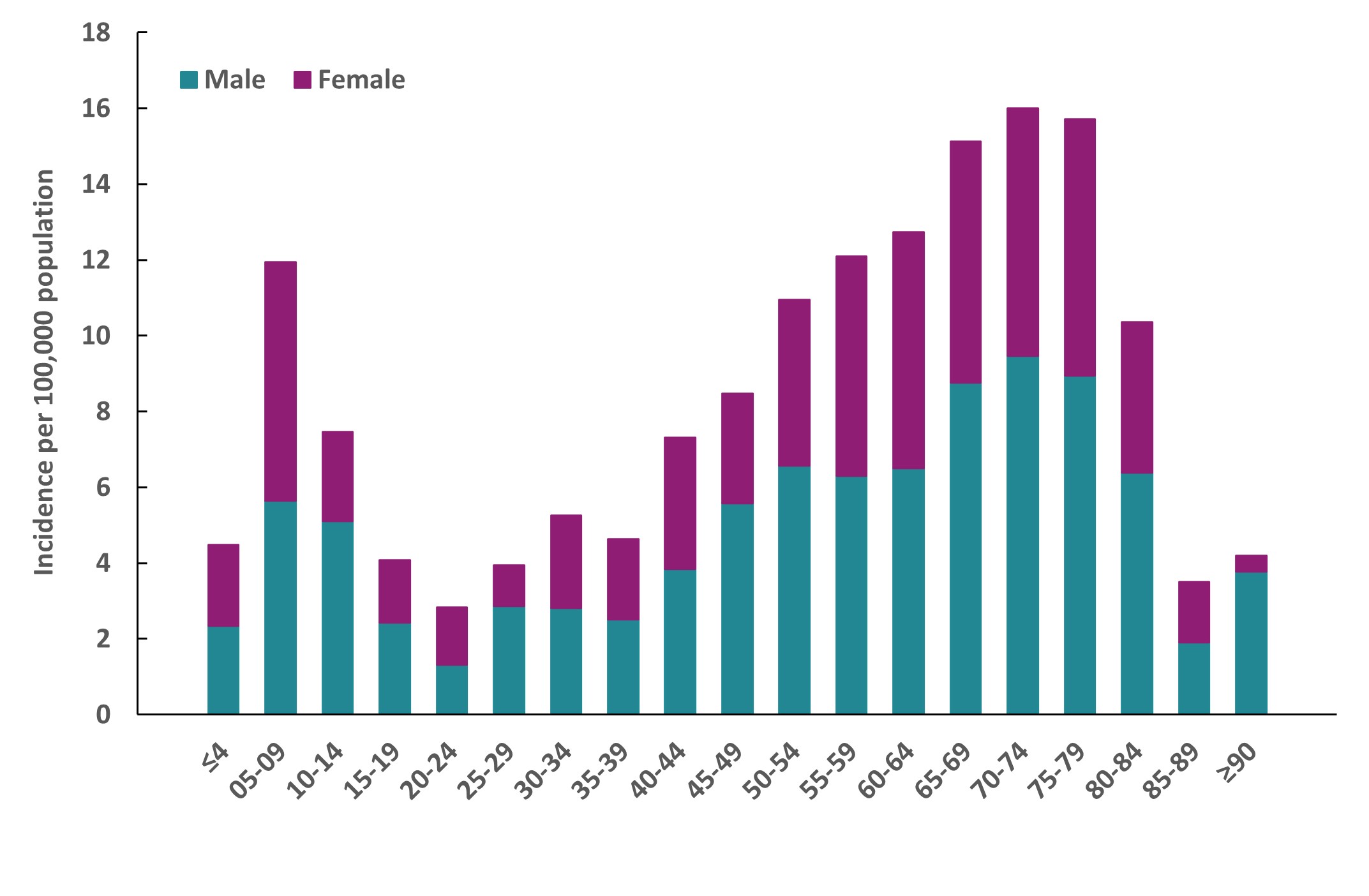

Demographic characteristics

In 2020, information on age and sex was available for 1,613 cases (99.8%). Like the previous year, the average age of reported Lyme disease cases was 48 years old. The incidence per 100,000 population for all reported Lyme disease cases exhibited a bimodal pattern with two peaks of high incidence. These occurred among children aged 5–9 years and adults aged 65–79 years (Figure 4), representing 7.6% and 24.9% of these cases, respectively. Except for the 5–9 and 20–24 age groups, incidence in males was higher than females, and overall, 56.1% of cases were male (n=905).

Figure 4 - Text equivalent

This figure is a stacked bar graph with bars showing the incidence per 100,000 population of male (teal) and female (pink) Lyme disease cases reported by age group (intervals of five years). The incidences by age group are detailed in the following table:

| Age | Incidence per 100,000 – Male | Incidence per 100,000 – Female |

|---|---|---|

| ≤4 | 2.34 | 2.14 |

| 05-09 | 5.64 | 6.3 |

| 10-14 | 5.11 | 2.36 |

| 15-19 | 2.42 | 1.66 |

| 20-24 | 1.31 | 1.52 |

| 25-29 | 2.86 | 1.09 |

| 30-34 | 2.82 | 2.44 |

| 35-39 | 2.51 | 2.13 |

| 40-44 | 3.85 | 3.46 |

| 45-49 | 5.57 | 2.9 |

| 50-54 | 6.57 | 4.38 |

| 55-59 | 6.3 | 5.8 |

| 60-64 | 6.43 | 6.23 |

| 65-69 | 8.76 | 6.36 |

| 70-74 | 9.36 | 6.54 |

| 75-79 | 8.94 | 6.78 |

| 80-84 | 6.38 | 3.98 |

| 85-89 | 1.9 | 1.61 |

| ≥90 | 3.77 | 0.43 |

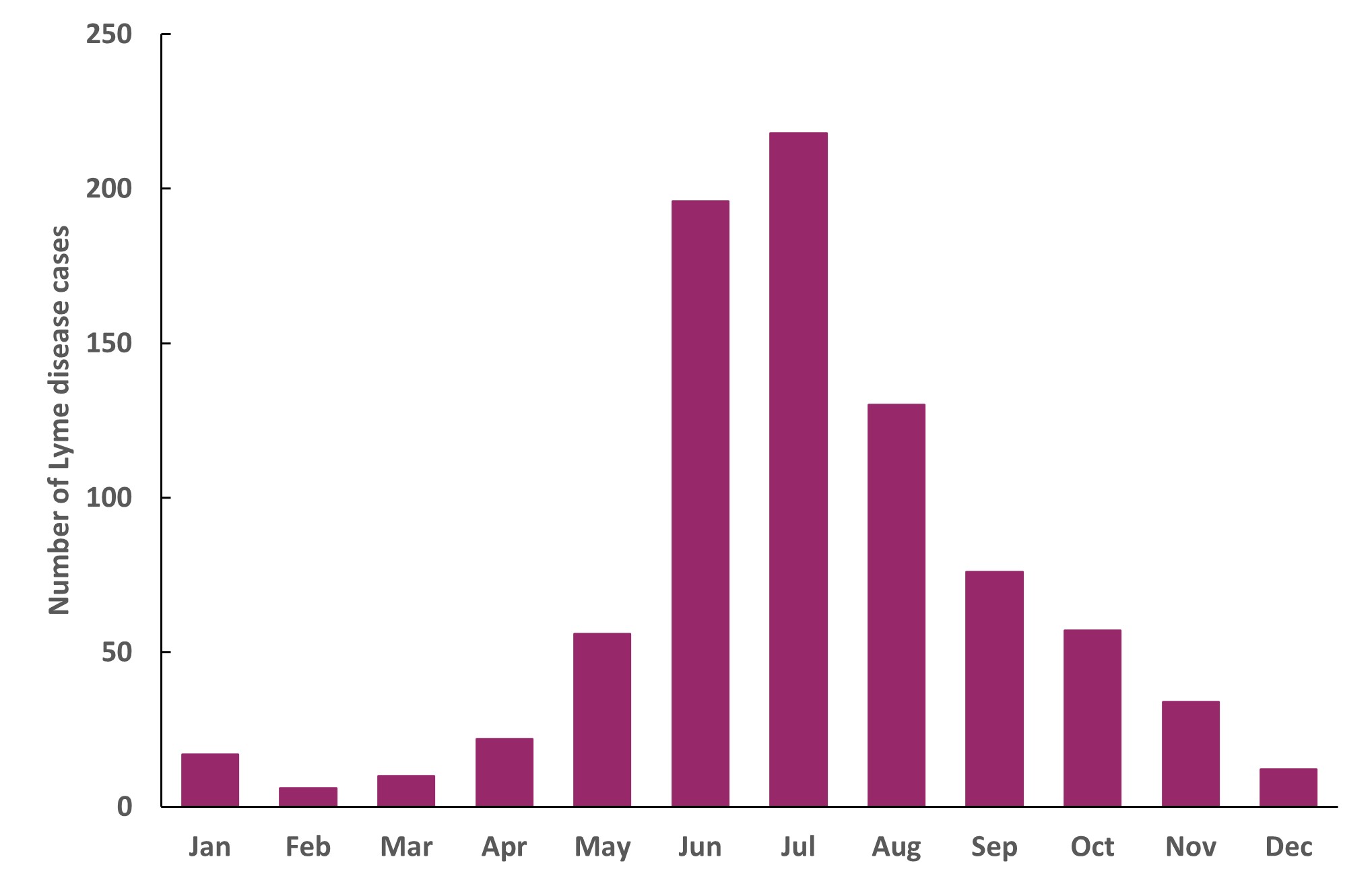

Seasonality

In 2020, 834 locally acquired cases included a date of illness onset. These cases occurred in every month of the year; however, 87.9% occurred between May and October. More than 65.2% of the cases had a reported episode date during the months of June (23.5%), July (26.1%), and August (15.6%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5 - Text equivalent

This is a bar chart with vertical bars showing the months of reported illness onset date of Lyme disease cases acquired locally, from left to right, from January to December. The months of reported illness onset date of Lyme disease cases are detailed in the following table:

| Month | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| January | 17 |

| February | 6 |

| March | 10 |

| April | 22 |

| May | 56 |

| June | 196 |

| July | 218 |

| August | 130 |

| September | 76 |

| October | 57 |

| November | 34 |

| December | 12 |

Discussion

In 2020, nine provinces reported 1,617 cases of Lyme disease to PHAC, representing a decrease of 39% compared to 2019. In previous years, there has been a decrease in the risk of Canadians acquiring Lyme disease in 2014 and 2018. Various factors can contribute to such fluctuations in risk. These include underreporting (4), public health prevention efforts and inter-annual variations in weather affecting tick activity (5). Factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic may also have influenced the risk of acquiring Lyme disease, for example, by affecting the amount of time Canadians spent outdoors, being associated with travel restrictions, and affecting healthcare-seeking behaviours (6).

Climate change continues to increase the risk of Lyme disease across the country. It does so by contributing to the expansion of habitat suitable for blacklegged ticks in eastern Canada (7, 8), to landscape changes, greater activity and range of ticks and their hosts, as well as an increase in uptake of outdoor human activity in longer and warmer seasons (9, 10).

In 2020, trends related to age and sex distribution are similar to those observed in previous years and in the USA, with higher incidence in males and peaking in two age groups: children aged 5−9 years and adults aged 65−79 years (3, 11, 12, 13). As observed before and in the USA, the reported illness onset was higher in summer months, peaking in July (3, 11, 13), corresponding to the season in which ticks are most actively seeking hosts and when Canadians are more likely to participate in outdoor activities (14). As a result, Canadians should be aware of the risk of tick bites during such activities as gardening, camping, hiking and outdoor excursions.

A large proportion of cases acquired infection in locations in southern and southeastern Ontario, southern Québec and in Nova Scotia, where the main vector of Lyme disease, the blacklegged tick, is established. Ten (10) cases were related to travel to endemic areas in the USA and Europe. It is important that Canadians travelling to endemic areas in the USA and Europe be aware of the risk of infection when participating in outdoor activities and use personal protective measures to prevent tick bites.

Public health conclusions

Lyme disease continues to be the most frequently reported vector-borne disease in Canada. Although there was a dip in the number of cases reported in 2020, there has been an overall upward trend of reported Lyme disease cases in Canada since 2009. It is estimated that the number of reported Lyme disease cases will continue to increase in the future (9). This trend will be influenced by several factors including the local abundance of infected tick populations, and the continued range expansion of tick populations in Canada.

The key findings of this report highlight the importance of sustained human and vector surveillance and preventative strategies, especially enhancing public awareness, to minimize the burden of Lyme disease in Canada.

Acknowledgements

The Public Health Agency of Canada acknowledges the provincial and territorial partners for their participation in the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (CNDSS) and Lyme Disease Enhanced Surveillance (LDES) system.

References

- Guillot C, Badcock J, Clow K, Cram J, Dergousoff S, Dibernardo A, et al. Sentinel surveillance of Lyme disease risk in Canada, 2019: Results from the first year of the Canadian Lyme Sentinel Network (CaLSeN). Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2020;46(10):354.

- Chilton NB, Curry PS, Lindsay LR, Rochon K, Lysyk TJ, Dergousoff SJ. Passive and active surveillance for Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) in Saskatchewan, Canada. J. Med. Entomol. 2019; 57(1):156.

- Gasmi S, Koffi JK, Nelder MP, Russell C, Graham-Derham S, Lachance L, et al. Surveillance for Lyme disease in Canada, 2009–2019. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2022; 48(5):219.

- Ogden NH, Bouchard C, Badcock J, Drebot MA, Elias SP, Hatchette TF, et al. What is the real number of Lyme disease cases in Canada? BMC public health. 2019; 19(1):849.

- Berger KA, Ginsberg HS, Dugas KD, Hamel LH, Mather TN. Adverse moisture events predict seasonal abundance of Lyme disease vector ticks (Ixodes scapularis). Parasites Vectors. 2014; 7(1):181.

- McCormick DW, Kugeler KJ, Marx GE, Jayanthi P, Dietz S, Mead P, et al. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on reported Lyme disease, United States, 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021; 27(10):2715.

- Robinson EL, Jardine CM, Koffi JK, Russell C, Lindsay LR, Dibernardo A, et al. Range Expansion of Ixodes scapularis and Borrelia burgdorferi in Ontario, Canada, from 2017 to 2019. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2022;22(7):361.

- Bouchard C, Leonard E, Koffi JK, Pelcat Y, Peregrine A, Chilton N, et al. The increasing risk of Lyme disease in Canada. Can. Vet. J. 2015;56(7):693.

- Bouchard C, Dibernardo A, Koffi JK, Wood H, Leighton PA, Lindsay LR. Increased risk of tick-borne diseases with climate change. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2019;45(4):81.

- Mysterud A, Easterday WR, Stigum VM, Aas AB, Meisingset EL, Viljugrein H. Contrasting emergence of Lyme disease across ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 2016; 7(1):11882.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Lyme disease surveillance report: Preliminary annual report 2019; 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/lyme-disease-surveillance-report-2019.html [Accessed 2022 Dec 30].

- Ogden NH, Koffi JK, Lindsay LR, Fleming S, Mombourquette DC, Sanford C, et al. Vector-borne diseases in Canada: Surveillance for Lyme disease in Canada, 2009 to 2012. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2015; 41(6):132.

- Schwartz AM, Hinckley AF, Mead PS, Hook SA, Kugeler KJ. Surveillance for Lyme Disease-United States, 2008-2015. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2017; 66(22):1.

- Kurtenbach K, Hanincová K, Tsao JI, Margos G, Fish D, Ogden NH. Fundamental processes in the evolutionary ecology of Lyme borreliosis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006; 4(9):660.

Footnotes

- Footnote 1

-

The denominators used to calculate the incidences were obtained from Statistics Canada, population estimates on July 1st