Lyme disease surveillance in Canada: Annual edition 2018

Download in PDF format

(1,272 KB, 12 pages)

- Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

- Published: September 2023

Related Links

On this page

- 2018 surveillance highlights

- Introduction

- Methods

- Results

- Discussion

- Public health conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- References

2018 surveillance highlights

- A total of 1,487 human cases of Lyme disease were reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada, of which, 1,053 (71%) were confirmed cases and 434 (29%) probable cases.

- Incidence was highest in adults aged 60-74 years (28% of cases) and children aged 5-14 years (11% of cases) with predominance in males.

- 31% of cases reported an illness onset in July.

- 97% of cases were reported in Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia.

- 8% of the reported cases were likely infected during travel outside of Canada.

Introduction

Vector-borne diseases are infectious diseases caused by bacteria, viruses and parasites that spread between animals and humans. Lyme disease is a multisystemic infection which can lead to health issues such as erythema migrans rash, cardiac, neurologic or arthritic manifestations. It is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which is transmitted by the bite of an infected tick; the blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis, in Manitoba, central and eastern Canada and the western blacklegged tick, Ixodes pacificus in British Columbia. The ticks become infected after feeding on infected small mammals or birds.

Over the past decade, the northward geographic range expansion of the blacklegged tick populations in southeastern and south-central Canada, in part due to climate warming, has resulted in an increase of the number of locally acquired Lyme disease cases. Surveillance for ticks and human Lyme disease cases are conducted using a One Health approach to minimize the burden of what has become the most reported vector-borne disease in Canada. This report focuses on the human component of Lyme disease surveillance, providing surveillance overview of data on cases reported in 2018.

Methods

Since becoming nationally notifiable in 2009, human cases of Lyme disease in Canada have been reported voluntarily to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) by provincial/territorial health ministries/agencies through the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (CNDSS). Information collected through CNDSS include age, sex, and case classification (probable and confirmed case). In 2011, PHAC developed and implemented the Lyme Disease Enhanced Surveillance System whereby participating jurisdictions (eight provinces in 2018) report information additional to that collected by the CNDSS, including information on geographic location of infection acquisition, clinical features and laboratory resultsFootnote 1. Data obtained from provincial notifiable disease systems represent a snapshot at the time of data extraction and may differ from previous/subsequent reports, data displayed by provincial health authorities and from CNDSS.

Cases reported to PHAC are classified using the national Lyme disease 2016 case definitionFootnote 1.

Results

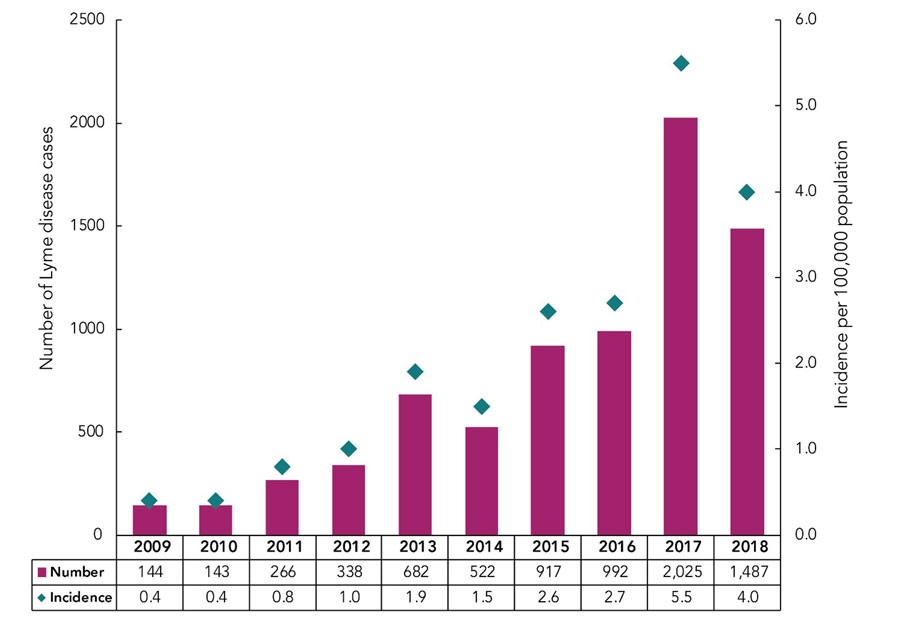

Changes in incidence amongst years

In 2018, 1,487 human cases of Lyme disease were reported in Canada. Of those, 1,053 (70.8%) were confirmed and 434 (29.2%) were probable cases. From 2009 through 2017, the total reported Lyme disease cases increased from 144 to 2,025 (an incidence of 0.4 and 5.5 per 100,000 population, respectively) and then decreased by 26.6% to 1,487 in 2018 (an incidence of 4.0 per 100,000 population) (Figure 1).

Noteworthy, although the surveillance system does not collect information about the outcome of the cases, Manitoba recorded one death attributed to Lyme carditis in 2018Footnote 2.

Figure 1 - Text Equivalent

| Year | Number of cases | Incidence per 100,000 population |

|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 144 | 0.4 |

| 2010 | 143 | 0.4 |

| 2011 | 266 | 0.8 |

| 2012 | 338 | 1.0 |

| 2013 | 682 | 1.9 |

| 2014 | 522 | 1.5 |

| 2015 | 917 | 2.6 |

| 2016 | 992 | 2.7 |

| 2017 | 2,025 | 5.5 |

| 2018 | 1,487 | 4.0 |

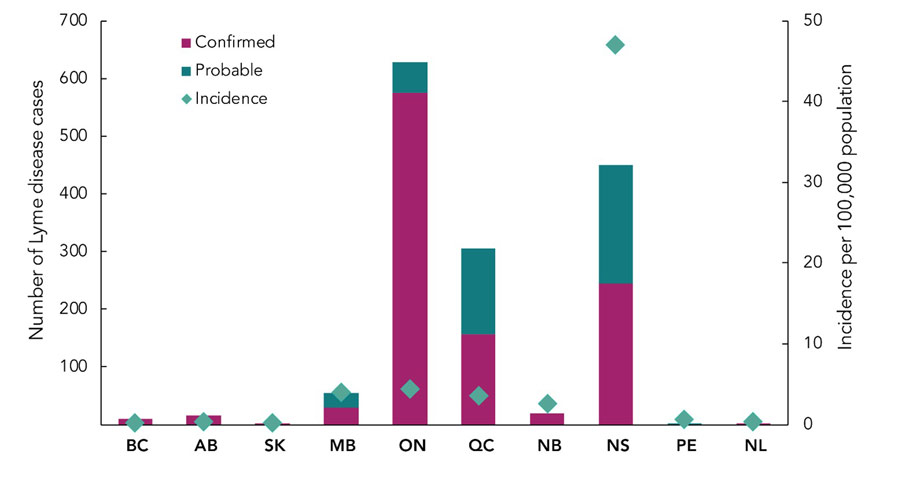

Geographic distribution

Both locally and travel-acquired cases are reported to PHAC. The majority of all cases (96.7%) were reported from Ontario (n = 628), Nova Scotia (n = 451), Quebec (n = 305) and Manitoba (n = 54) (Figure 2). Nova Scotia was the province with the highest incidence (47.0 per 100,000 pop.) (Figure 2) which is 11.7 folds greater than the national incidence (of 4.0 per 100,000 pop.). The greatest decline in the reported cases from 2017 to 2018 was seen in Ontario where the number fell from 1,005 in 2017 (incidence of 7.1 per 100,000 pop.) to 628 in 2018 (incidence of 4.4 per 100,000 pop.), a decrease of 37%.

Figure 2 - Text Equivalent

| Province | Case classification | Total | Incidence per 100,000 population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed | Probable | |||

| British Columbia | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0.2 |

| Alberta | 15 | 0 | 15 | 0.3 |

| Saskatchewan | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.2 |

| Manitoba | 29 | 25 | 54 | 4.0 |

| Ontario | 576 | 52 | 628 | 4.4 |

| Quebec | 156 | 149 | 305 | 3.6 |

| New Brunswick | 20 | 0 | 20 | 2.6 |

| Nova Scotia | 244 | 207 | 451 | 47.0 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.4 |

Furthermore, cases reported by Alberta, Saskatchewan, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland & Labrador were travel-related only.

Abbreviations: BC, British Columbia; AB, Alberta; SK, Saskatchewan; MB, Manitoba; ON, Ontario; QC, Quebec; NB, New Brunswick; NS, Nova Scotia; PE, Prince Edward Island; NL, Newfoundland & Labrador. Note that probable cases are not reported in British Columbia and Saskatchewan.

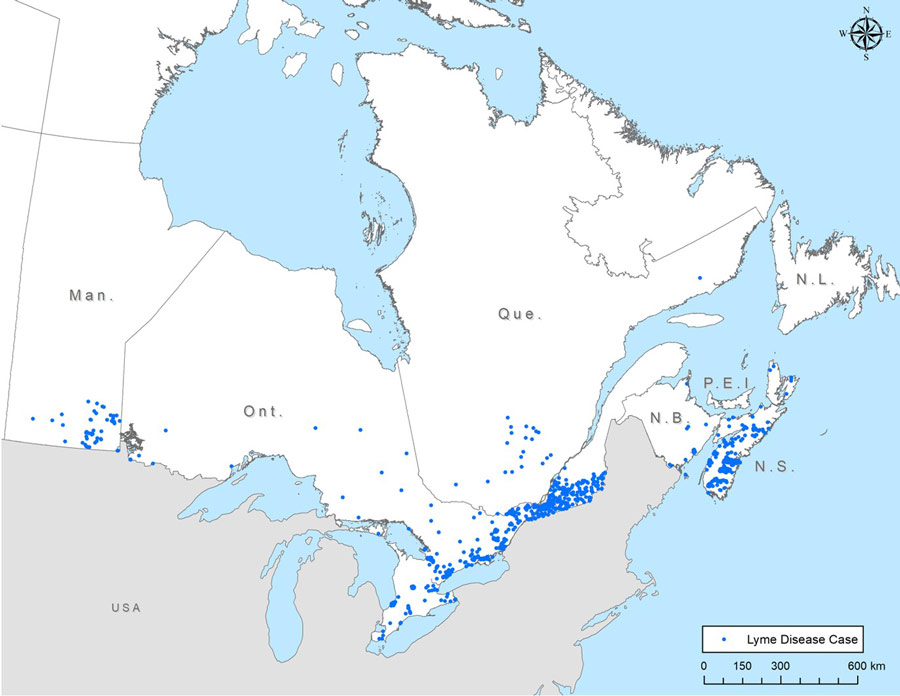

Locally acquired cases

In Canada, Lyme disease cases were acquired in six provinces in 2018: British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Text Equivalent

| Province | Number of cases | Number of census subdivisions | Number of health regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manitoba | 48 | 22 | n/a |

| Ontario | 365 | 100 | n/a |

| Quebec | 218 | n/a | 8 |

| New Brunswick | 19 | 8 | n/a |

| Nova Scotia | 334 | 41 | n/a |

| Total | 984 | 171 | 8 |

Legend: Each dot on the map represents the probable location of infection acquisition, randomly distributed at the health region level for Quebec and at the census subdivision level for the other provinces. The majority of locally reported cases are concentrated in locations in southern Manitoba, southern and southeastern Ontario, southern Quebec and in Nova Scotia. Data on location of acquisition was available for 69% of the locally acquired cases. The data on location of acquisition at a sub-provincial level were not available for British Columbia. Furthermore, cases reported by Alberta, Saskatchewan, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland & Labrador were travel-related only.

Travel-related cases

Lyme disease is mostly acquired in parts of Canada where blacklegged tick populations are established (i.e., at-risk areas) or during travel in countries where the disease is endemic. In 2018, the information of travel-history was available for 1,217 Lyme disease cases. Of these, 100 cases (8.2%) were likely infected during travel outside of Canada and were probably acquired either in the USA (51 cases), or in Europe (49 cases).

Demographic characteristics

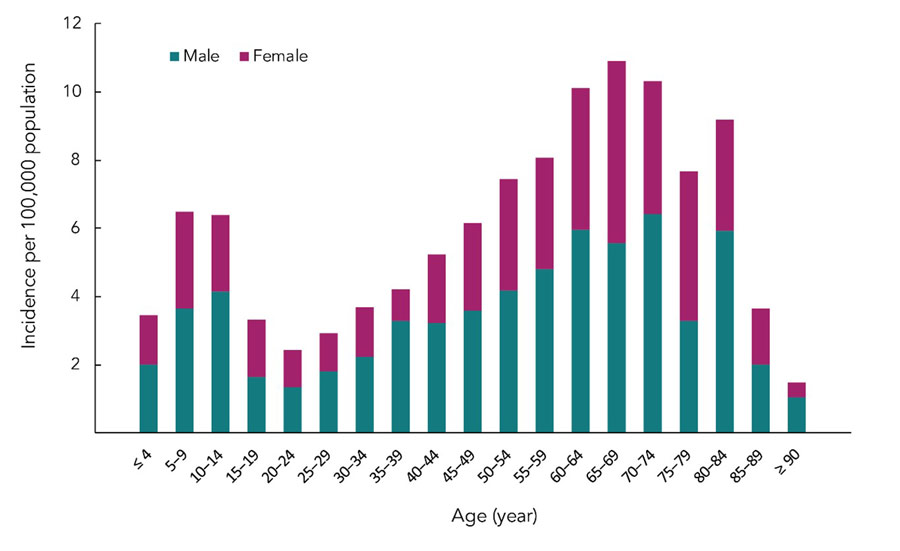

In 2018, information on age and sex was available for 1,115 cases (75.2%). The average age of reported Lyme disease cases was 47 years old. The highest incidence of reported Lyme disease was in adults aged 60-74 and in children aged 5-14 (Figure 4), representing 27.7% and 11.4% of all cases, respectively. Except for the 75-79 age group, incidence in males was higher than in females, and overall, 58.1% of reported cases were males.

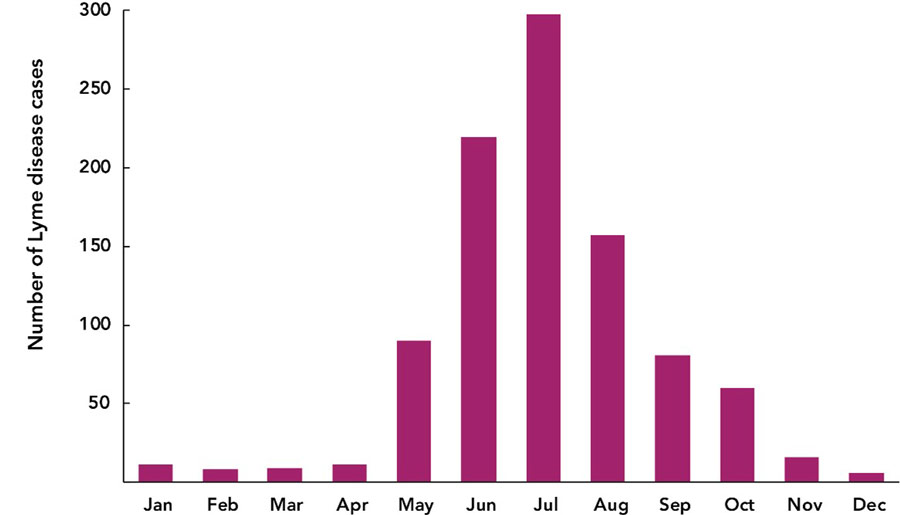

Seasonality

In 2018, Lyme disease cases were reported in every month; however, 95.3% of the cases occurred from May through November. More than 69% of the cases had symptom onset during the summer months of June (22.8%), July (30.8%) and August (16.2%) (Figure 5).

Figure 4 - Text Equivalent

| Age (year) | Incidence per 100,000 | |

|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |

| ≤ 4 | 2.0 | 1.5 |

| 5-9 | 3.7 | 2.8 |

| 10-14 | 4.1 | 2.3 |

| 15-19 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| 20-24 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| 25-29 | 1.8 | 1.1 |

| 30-34 | 2.3 | 1.4 |

| 35-39 | 3.3 | 0.9 |

| 40-44 | 3.2 | 2.0 |

| 45-49 | 3.6 | 2.6 |

| 50-54 | 4.2 | 3.2 |

| 55-59 | 4.8 | 3.3 |

| 60-64 | 6.0 | 4.2 |

| 65-69 | 5.6 | 5.3 |

| 70-74 | 6.4 | 3.9 |

| 75-79 | 3.3 | 4.4 |

| 80-84 | 5.9 | 3.3 |

| 85-89 | 2.0 | 1.6 |

| ≥ 90 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

Figure 5 - Text Equivalent

| Month | Number of Lyme disease cases |

|---|---|

| January | 11 |

| February | 8 |

| March | 9 |

| April | 11 |

| May | 90 |

| June | 220 |

| July | 298 |

| August | 157 |

| September | 81 |

| October | 60 |

| November | 16 |

| December | 6 |

Discussion

In 2018, ten provinces reported 1,487 cases to PHAC representing a decrease of 26.6% compared to the previous year. Impacts of human activities, climate and landscape changes can influence the human infection risk on the long term. However, change in the frequency of human exposure, infection, detection and reporting of cases may vary amongst years. Environmental and human behavioural factors may have caused a reduction in the risk of acquiring infection in 2018, as was seen in 2014. Similar interannual variations have been seen in surveillance data in the USFootnote 3, and these may be due to interannual variations in weather that affect tick activity and survivalFootnote 4, or time spent doing outdoor pursuits by the publicFootnote 5. To some extent, this may also reflect efforts by the different Canadian public health authorities at the federal, provincial/territorial and local levels, to enhance prevention of Lyme disease, including promotion of measures to prevent tick bites, and increase the availability of post-tick bite antimicrobial prophylaxis in some jurisdictionsFootnote 6,Footnote 7. Despite the 2018 decrease in the number of reported cases, long-term risk of human infection is increasingFootnote 8,Footnote 9 in part because of the warming climate that drives the northward range expansion of the blacklegged ticks in eastern Canada. In addition, as for any surveillance system, it is likely that there is some underreportingFootnote 10 because some cases may be undetected or not reported.

In 2018, children aged 5-14 years and adults aged 60-74 years are the age groups with apparently higher risk of acquiring Lyme disease, while for nearly all age groups incidence was higher in males. Age and sex- based variation in risk may be related to behavioural or occupational/recreational risk factors, which lead to higher likelihood of tick bites and Lyme disease transmissionFootnote 3,Footnote 10,Footnote 11. It would be worthwhile for public health programs to target these at-risk groups to increase their vigilance and adoption of preventive measures in order to reduce the risk for Lyme disease in areas where the vector ticks are present (learn about Prevention of Lyme disease on the Canada.ca website).

Lyme disease cases were observed in every month in 2018; however, most had symptom onset from May to November and there were distinct peaks in cases during the summer months when nymphal ticks are most activeFootnote 12,Footnote 13 and people are most likely to be engaged in outdoor activities. However, illness onset occurred throughout the year, which would be consistent with the onset of manifestations of disseminated Lyme disease some months post-infectionFootnote 14 (learn about Lyme disease, its causes, symptoms, risks, treatment and prevention on the Canada.ca website). Health care providers should be aware that Lyme disease cases can occasionally be observed outside the peak activity period for ticks and as a result should not exclude Lyme disease diagnosis when there is evidence of compatible clinical manifestations.

The majority of reported cases acquired infection in locations in southern Manitoba, southern and southeastern Ontario, southern Quebec and in Nova Scotia, where the main vector of Lyme disease, the blacklegged tick is establishedFootnote 15 (for more details, see where is the risk in Canada? on the Canada.ca website). However, some cases appear to have been acquired outside of known risk areas, which may indicate that, albeit at a low level, there is a real risk of acquiring Lyme disease from adventitious blacklegged ticks dispersed by migratory birds. In western provinces, only British Columbia reported a few locally-acquired cases. In this province, the risk from infected western blacklegged tick (the other main vector of Lyme disease) remains stable compared with the provinces where blacklegged tick is establishedFootnote 16.

In 2018, where information on travel-history was available, the 100 travel-related cases acquired infection in the USA or Europe. Canadians travelling to endemic areas in the USA and Europe should be aware of outdoor activities that put them at increased risk and ensure the use of personal protection measures to prevent tick bites and Lyme disease (see Lyme disease prevention toolkit on the Canada. ca website).

Public health conclusions

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vector-borne disease in Canada. Although the number of cases dipped in 2018, it is anticipated that the number of reported Lyme disease cases will continue to increase in the future. This trend will be driven in part by local abundance of infected nymphal tick populations and by continued range expansion of tick populations in Canada.

The key findings of this report highlight the need for further development and implementation of targeted awareness campaigns designed to minimize the burden of Lyme disease in Canada.

Acknowledgements

The Public Health Agency of Canada acknowledges the provincial and territorial partners for their participation to the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System and Lyme Disease Enhanced Surveillance System.