Obesity Statistics in Canada: Report

Download in PDF format

(2.5 MB, 120 pages)

Organization:Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: 2025-06-05

Table of contents

- Acknowledgements

- Executive summary

- List of tables

- List of figures

- Section 1: What is obesity and how is it measured?

- Section 2: Adult obesity

- Section 3: Child and youth obesity

- Section 4: Data sources and methods

- Appendixes

- Bibliography

Acknowledgements

The report was prepared by the following people (currently and formerly) in the Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research (CSAR) at the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC): Farah Barakat, Julie Bates, Marisol Betancourt, Alexandria Melvin, Karen C Roberts, Margot Shields, Calum Thompson, Wendy Thompson, Stephanie Toigo, Ron Wall, Chinchin Wang, and Danisha Zaman.

We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of the following who provided valuable review and input to the development of this report: Mary Sue Devereaux, Didier Garriguet, Margaret de Groh, Blair Jones, Alison Lake, Sarah MacKinnon, Shaila Rodrigues, and Eric Vallières.

Executive summary

Introduction (and health risks)

The term "obesity" describes a medical condition where excess body fat threatens health. Individuals with excess body fat have an elevated risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, some types of cancers, and various mental health conditions Footnote 1Footnote 2. Among children, high body mass index (BMI) has been associated with the early onset of diseases including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and a range of cancers Footnote 3Footnote 4. Evidence also suggests that a high BMI in childhood can have adverse psychosocial impacts, such as depression, lower self-esteem, and behavioral disorders Footnote 5Footnote 6. As well, obesity in childhood and adolescence is strongly associated with obesity in adulthood Footnote 7Footnote 8.

Purpose of this report

The purpose of this report is to promote awareness and give the most up-to-date information and data on the prevalence of obesity among adults, children, and adolescents in the Canadian context. This report aims to inform stakeholders, policymakers, and healthcare professionals when developing programs and policies concerning the prevalence of obesity in Canada. This report discusses obesity and how it is measured in addition to identifying the population groups more affected by obesity.

The information and data portrayed in this report are drawn from the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) years 2000 to 2021, the Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS) cycle 1 (2007-2009) to cycle 6 (2018-2019), and the CCHS–Nutrition Focus (CCHS-Nutrition) from 2004 and 2015. The statistical analysis of the data allows for prevalence breakdowns of obesity according to different variables (where available) such as: age and sex, household income and education, Indigenous status, regional variation, as well as temporal and forecasted projections.

How is obesity measured?

BMI is the indicator most used by surveillance systems to track excess body fat within a population. BMI is a measure of an individual's weight in relation to their height (weight divided by height squared-weight (kg)/height (m2)) Footnote 9.

For adults

Among adults, BMI estimates calculated from self-reported data are often biased, because adults' self-reports underestimate weight and overestimate height Footnote 10. Correction equations for adjusting BMI based on self-reported height and weight have been developed for use on adults in the CCHS. In this report, BMIAdjSR refers to BMI based on self-reported values that have been adjusted to correct for biases. For adults, only BMI from measured data and adjusted BMI are presented in the report.

For children and youth

Children and youth grow at varying rates, therefore the World Health Organization age- and sex-specific cut-points are applied to classify BMI Footnote 11Footnote 12Footnote 13. For 5- to 17-year-olds, there are four BMI categories (thin, normal weight, overweight, and obesity). For children younger than 5 years, an "at risk of overweight" category is also used to lessen the likelihood that they will be classified in the obesity category during a period of rapid growth. Among children and youth, self- and parent-reported height and weight often result in substantial misclassification of BMI, for which no correction equations have been established in Canada Footnote 14Footnote 15. Consequently, only measured data for children and youth are used in this report.

Key findings

Adult obesity

- In 2021, 29.5% of Canadian adults had a BMIAdjSR classified as obesity. An additional 35.5% had a BMIAdjSR classified as overweight. Therefore, 65% of Canadian adults are classified in the combined overweight and obesity category.

- Men were more likely than women to have a BMIAdjSR in the overweight range (39.7% versus 31.3%).

- The lowest prevalence of obesity was among the youngest (18 to 34 years) and oldest (80 years or older) age groups: 22.5% and 21.2%, respectively.

- Among women, low household income was associated with a significantly higher prevalence of obesity than the highest household income group (30.8% versus 26.6%).

- For both sexes, the lowest prevalence of obesity was among those in the highest household education group (post-secondary graduate).

- Obesity was significantly more common among adults in rural areas (33.6%) than in urban ones (28.6%).

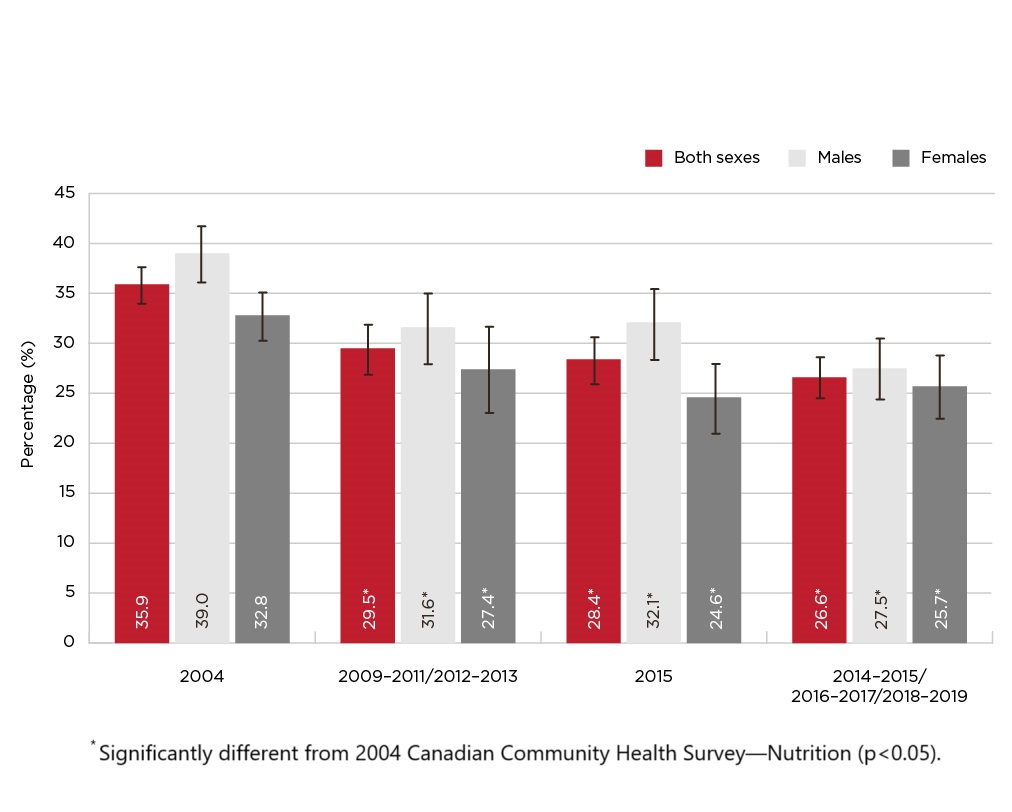

- Between 2000-2001 and 2019-2020, the prevalence of obesity among adults based on self-reported data rose from 20.6% to 28.2%. A significant upward trend in the prevalence of obesity (based on adjusted BMI) was observed among adults in all age groups, all household income quintiles, and all levels of household education. The impact of COVID-19 has yet to be determined.

Child and youth obesity

- In 2015, 12.4% of Canadian children and youth aged 5 to 17 years had a BMI that placed them in the obesity category, and another 19.4% were in the overweight range. As a result, close to one out of three children and youth (31.8%) were classified in the combined overweight and obesity category.

- A larger percentage of boys than girls were in the obesity category (14.9% versus 9.9%).

- The prevalence of combined overweight/obesity was higher at ages 12 to 17 years than at ages 5 to 11 years (35.6% versus 28.4%).

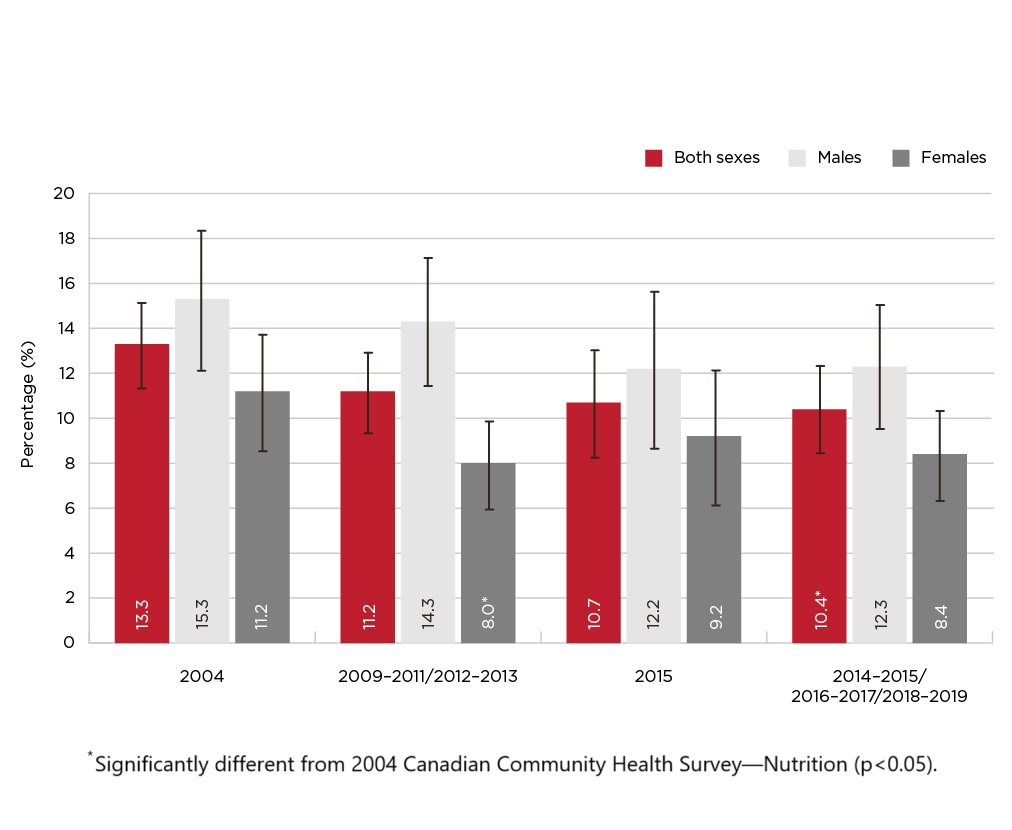

- In 2004, the prevalence of obesity among children and youth (12.9%) was double the rate observed in 1978-1979.

- There is an indication of child and youth obesity and overweight/obesity rates plateauing in recent decades, with some exceptions. Among 5- to 11-year-olds, both obesity and combined overweight/obesity prevalence in 2014-2019 were lower than in 2004 (13.3% versus 10.4%, and 35.9% versus 26.6%). Among 12- to 17-year-olds, no significant differences in obesity or combined overweight/obesity were observed. Among girls (but not boys) aged 2 to 4 years, the prevalence of combined overweight/obesity decreased between 2004 and 2015 (11.1% versus 4.1%).

Concluding remarks

For adults, the prevalence of obesity from 2021 appears to be higher than previous years, but additional data is required to determine if the increase is larger than would have been expected based on recent trends. Ongoing surveillance could help to monitor the trends of obesity in the context of a pandemic in the long term. We are awaiting nationally representative measured data for children and youth collected since the COVID-19 pandemic. Further research is needed to fully understand the impact COVID-19 had on health behaviours (for example, movement, dietary patterns) of children (5–11 years) and youth (12–17 years) in Canada Footnote 16. Ongoing research will help determine if obesity prevalence in children and youth remains at a plateau or if an increase will be observed following the COVID-19 pandemic.

List of tables

- Table 2a: Prevalence of waist circumference health risk by sex and age group, household population aged 18 to 79 years, Canada excluding territories, 2014 to 2019,

- Table 2b: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by sex and province/territory, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada, 2019-2020,

- Table 3a: Prevalence of measured obesity and overweight/obesity, by sex and household income quintile, household population aged 5 to 17 years, Canada excluding territories, 2015,

- Table 3b: Prevalence of measured obesity and overweight/obesity, by sex and highest level of education in household, household population aged 5 to 17 years, Canada excluding territories, 2015,

- Table 3c: Prevalence of measured obesity and overweight/obesity by sex and province, household population aged 5 to 17 years, Canada excluding territories, 2015,

- Table 3d: Prevalence of measured obesity and overweight/obese by sex and urban/rural, household population aged 5 to 17 years, Canada excluding territories, 2015,

- Table A2.2: Percentage distribution of household population aged 18 years or older, by sex and adjusted self-reported body mass index (BMI) category, Canada excluding territories, 2021,

- Table A2.3: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by sex and age group, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2021,

- Table A2.4: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by sex and household income quintile, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2021,

- Table A2.5: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by sex and highest level of education in the household, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2021,

- Table A2b: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity (age standardized) by sex and province/territory, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada, 2019-2020,

- Table A2.6: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by sex and urban/rural, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2021,

- Table A2.7: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by health regions among Canadians aged 18 years and older, 2015-2018,

- Table A2.8a: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by sex, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2000-2001 to 2019-2020,

- Table A2.8b: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity (age standardized) by sex, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2000-2001 to 2019-2020,

- Table A2.9: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by sex and age group, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2000-2001 to 2019-2020,

- Table A2.10: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by sex and household income quintile, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2000-2001 to 2019-2020,

- Table A2.11: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by sex and highest level of education in the household, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2000-2001 to 2019-2020,

- Table A2.12a: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported class III obesity by sex, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2000-2001 to 2019-2020,

- Table A2.12b: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported class III obesity (age standardized) by sex, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2000-2001 to 2019-2020,

- Table A2.13a: Prevalence of measured obesity by sex, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories (selected years),

- Table A2.13b: Prevalence of measured obesity (age standardized) by sex, household population aged 18-79 years, Canada excluding territories (selected years),

- Table A2.14a: Prevalence of measured class III obesity by sex, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada (selected years),

- Table A2.14b: Prevalence of measured class III obesity (age standardized estimates) by sex, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories (selected years),

- Table A2.16: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity among Indigenous/non-Indigenous peoples (living off reserve), by sex and age group, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2021,

- Table A3.1a: Percentage distribution of household population aged 2 to 17 years, by sex and measured body mass index (BMI) category, Canada excluding territories, 2015,

- Table A3.1b: Percentage distribution of household population aged 5 to 17 years, by sex and measured body mass index (BMI) category, Canada excluding territories, 2014-2019,

- Table A3.2a: Prevalence of measured obesity by sex and age group, household population aged 2 to 17 years, Canada excluding territories (selected years),

- Table A3.3a: Prevalence of measured overweight/obesity by sex and age group, household population aged 2 to 17 years, Canada excluding territories (selected years),

- Table A3.6: Prevalence of measured obesity and overweight/obesity among Indigenous/non-Indigenous children and youth, by sex, household population aged 5 to 17 years, Canada excluding territories, 2015,

- Table A4a: Response rates and sample sizes for self-reported estimates based on the Canadian Community Health Survey,

- Table A4b: Response rates and sample sizes for measured estimates,

List of figures

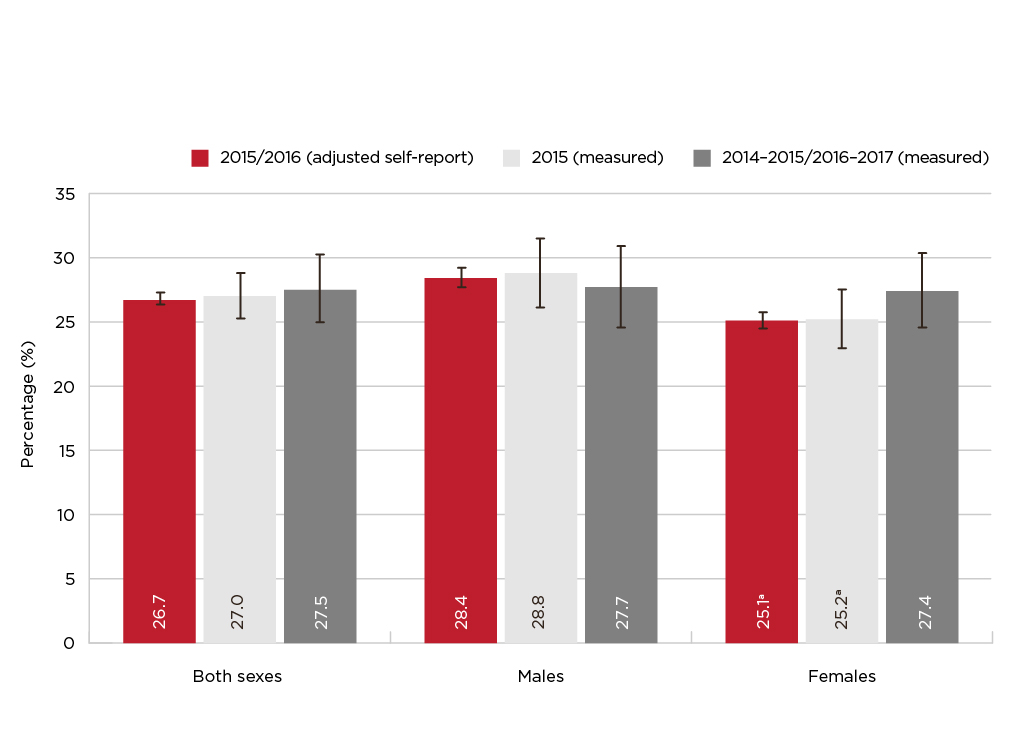

- Figure 2.1: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported and measured obesity by sex, household population aged 18 to 79 years, Canada excluding territories, (selected years)

- Figure 2.2: Percentage distribution of household population aged 18 years or older, by sex and adjusted self-reported body mass index (BMI) category, Canada excluding territories, 2021

- Figure 2.3: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by sex and age group, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2021

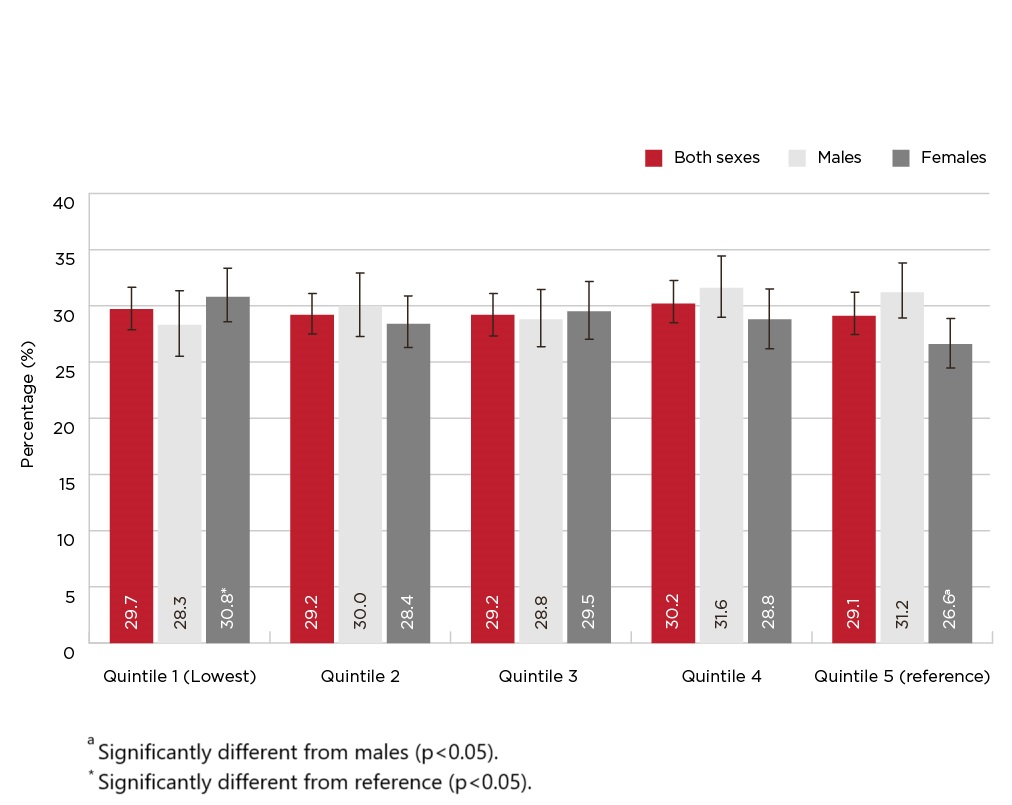

- Figure 2.4: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by sex and household income quintile, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2021

- Figure 2.5: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by sex and highest level of education in the household, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2021

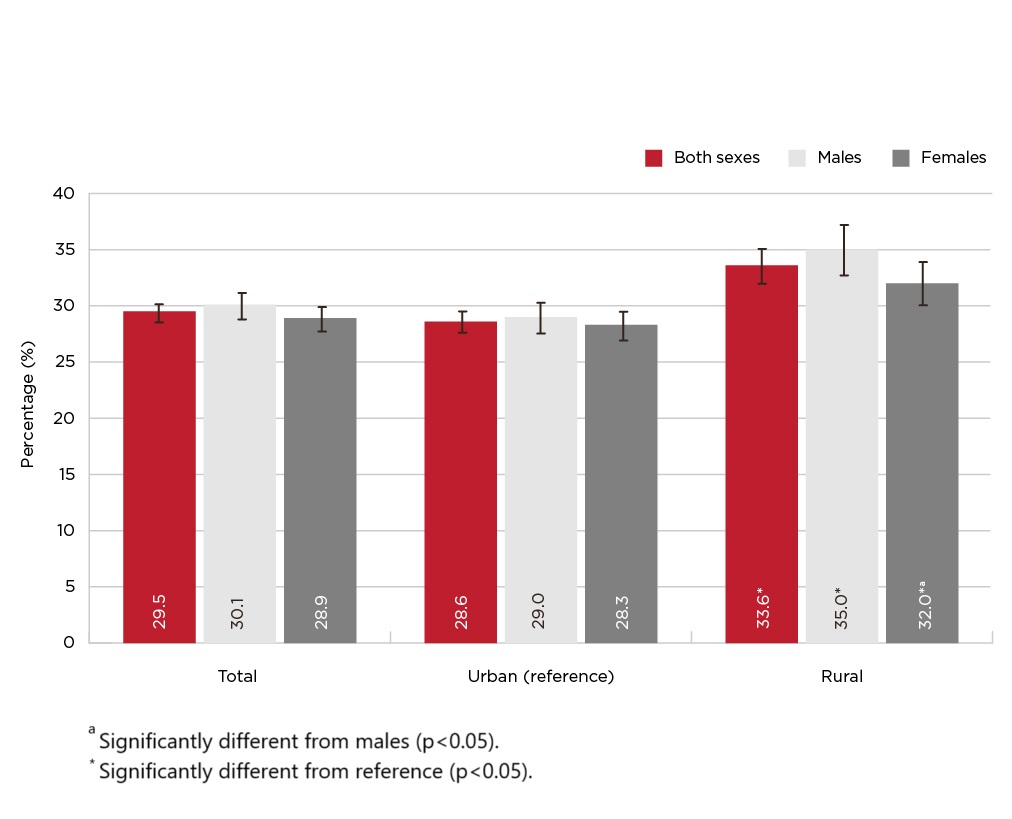

- Figure 2.6: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by sex and urban/rural, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2021

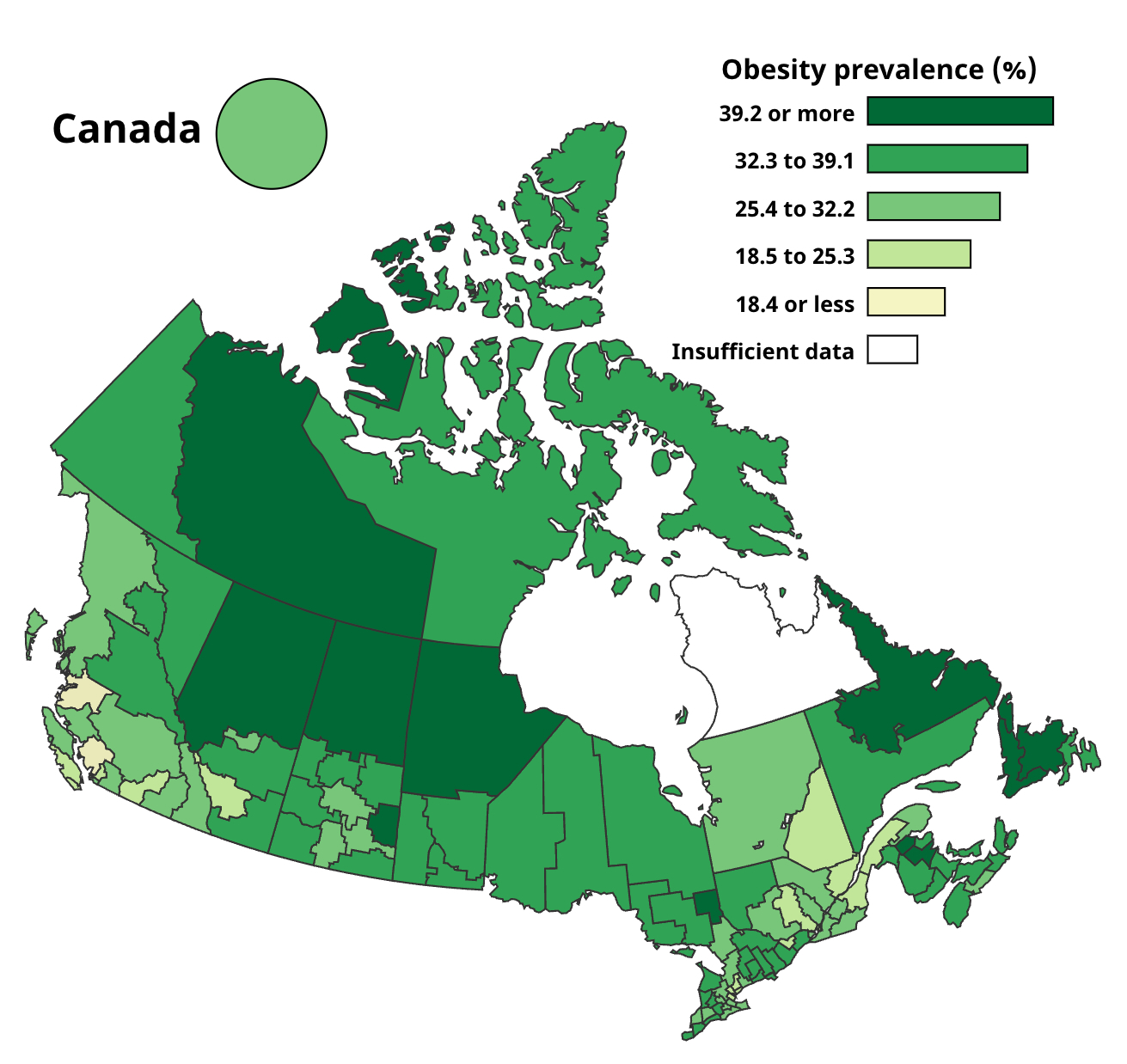

- Figure 2.7: Prevalence (%) of obesity (self-reported, adjusted BMI), crude rates, among Canadian adults aged 18 years and older, by health regions, both sexes

- Figure 2.8: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by sex, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada 2000-2001 to 2019-2020

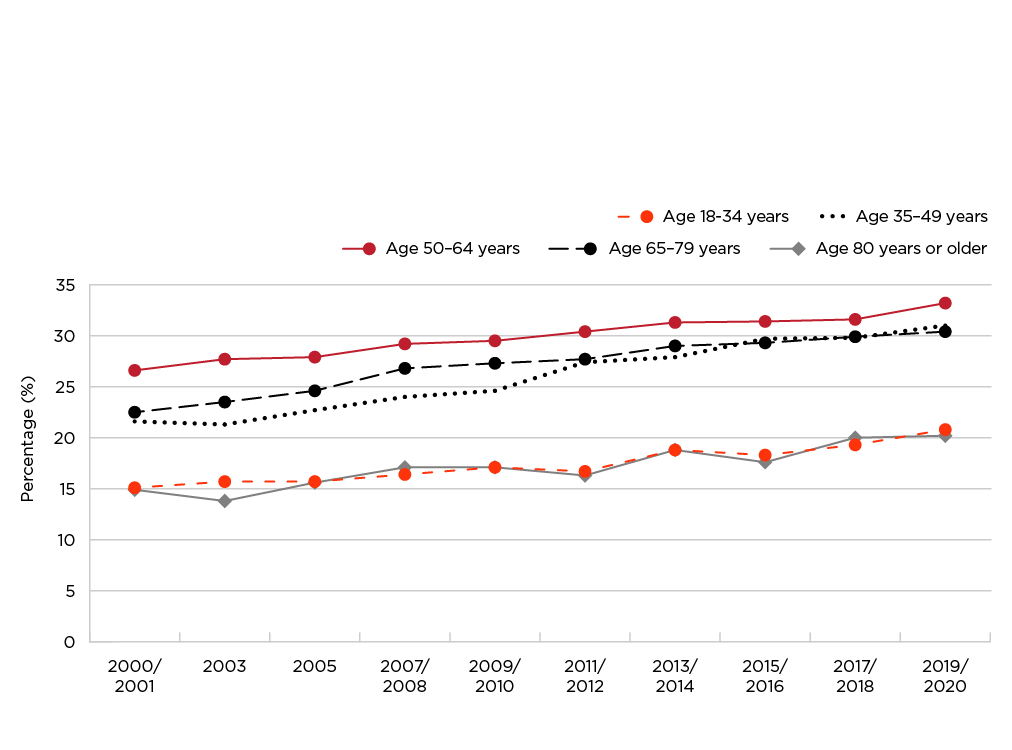

- Figure 2.9: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by age group, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada 2000-2001 to 2019-2020

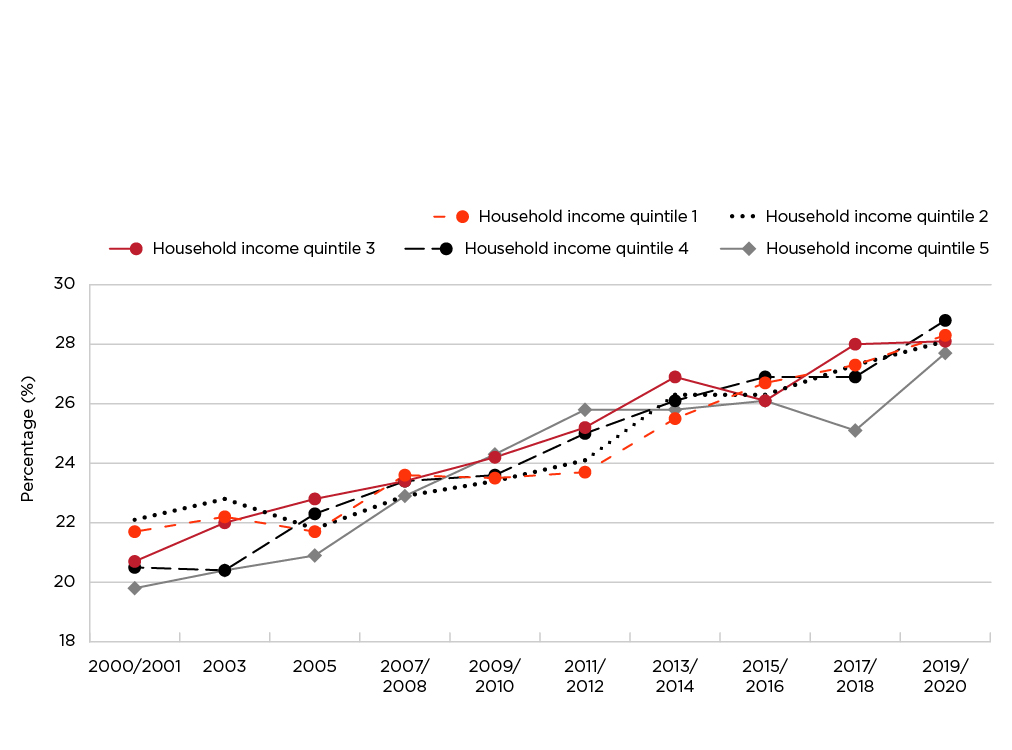

- Figure 2.10: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by household income quintile, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2000-2001 to 2019-2020

- Figure 2.11: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity by highest level of education in the household, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada excluding territories, 2000-2001 to 2019-2020

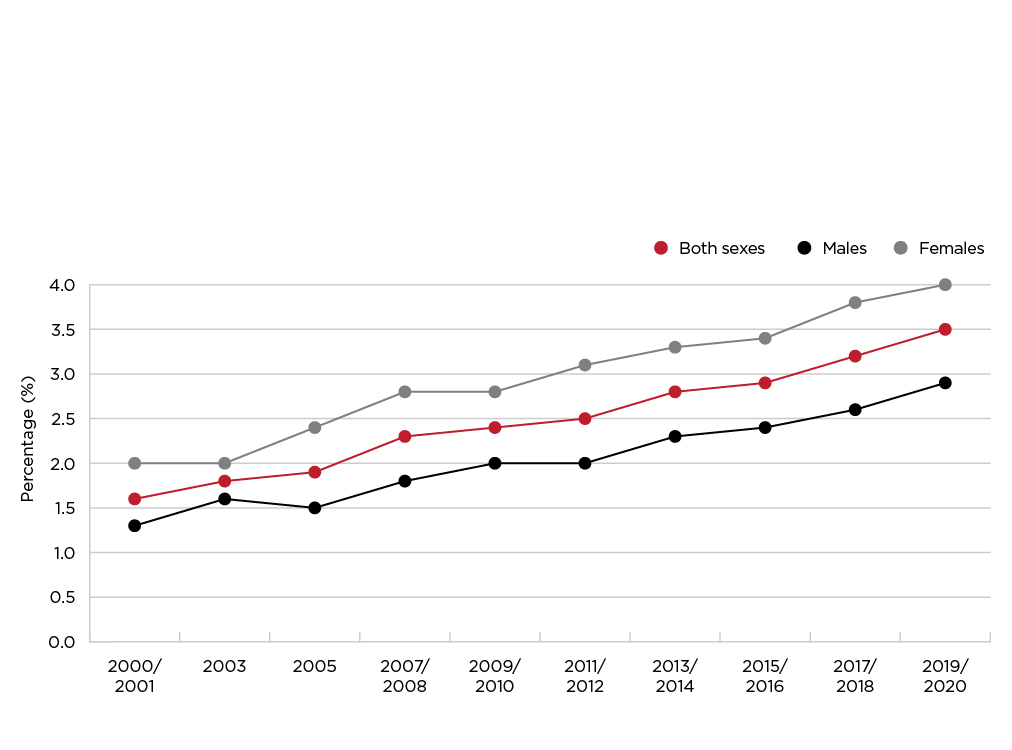

- Figure 2.12: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported class III obesity by sex, household population aged 18 years or older, Canada 2000-2001 to 2019-2020

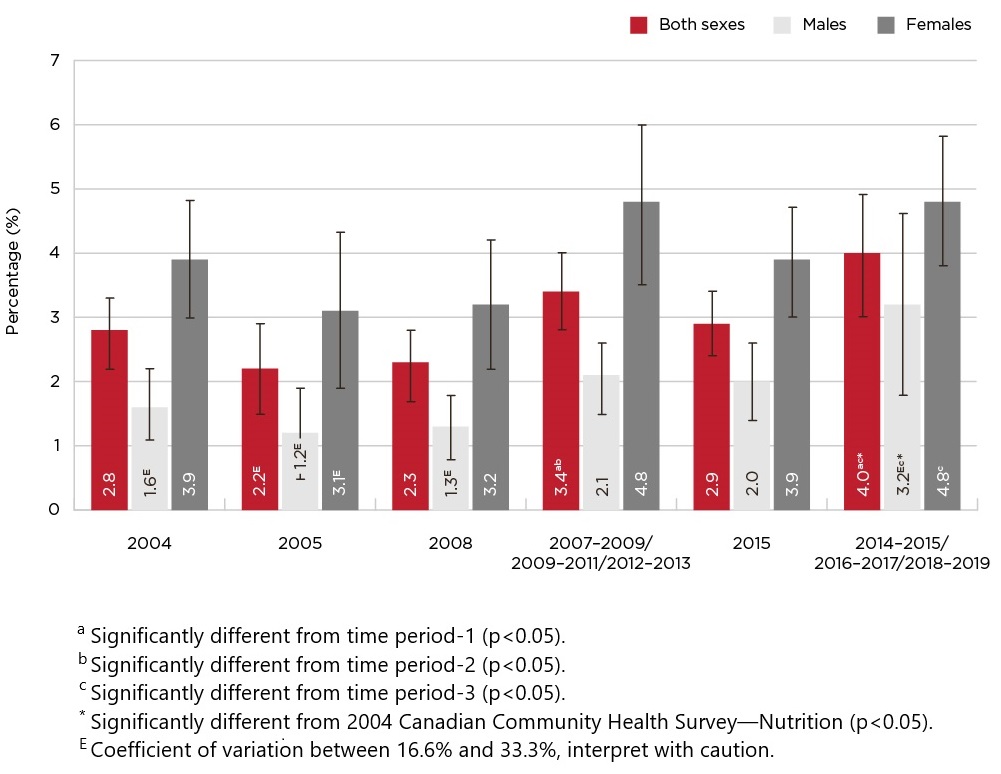

- Figure 2.13: Prevalence of measured obesity by sex, household population aged 18-79, Canada excluding territories (selected years)

- Figure 2.14: Prevalence of measured class III obesity by sex, household population aged 18-79 years, Canada (selected years)

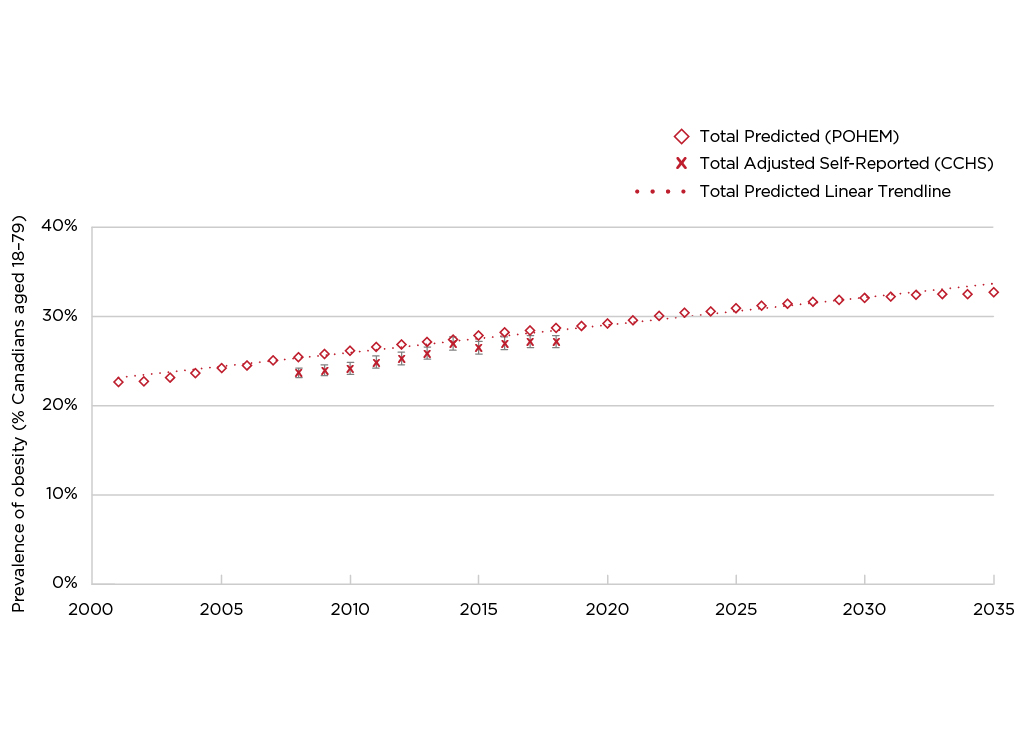

- Figure 2.15: Prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity based on POHEM projections and survey data, household population aged 18-79, Canada, 2001-2035

- Figure 3.1: Percentage distribution of household population aged 5-17 years, by sex and measured body mass index (BMI) category, Canada excluding territories, 2015

- Figure 3.2: Prevalence of measured obesity by sex, household population aged 5 to 11 years, Canada excluding territories (selected years)

- Figure 3.3: Prevalence of measured overweight/obesity by sex, household population aged 5 to 11 years, Canada excluding territories (selected years)

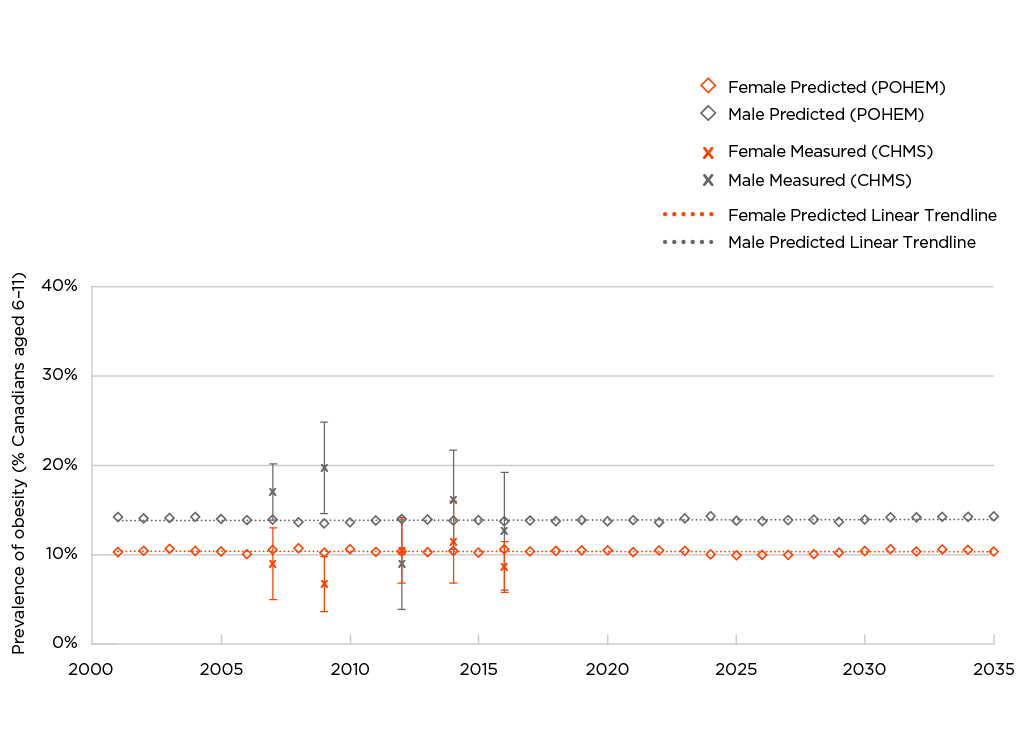

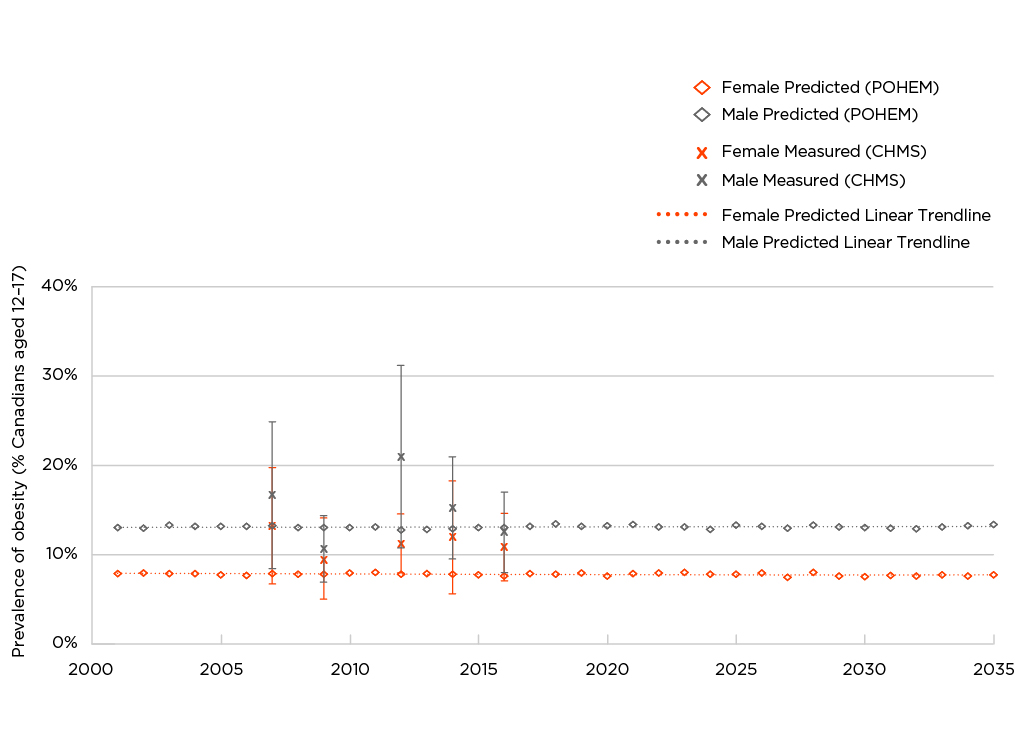

- Figure 3.4: Prevalence of measured obesity based on POHEM projections and survey data, household population aged 6-11, by sex, Canada excluding the territories, 2001-2035

- Figure 3.5: Prevalence of measured obesity based on POHEM projections and survey data, household population aged 12-17, by sex, Canada excluding the territories, 2001-2035

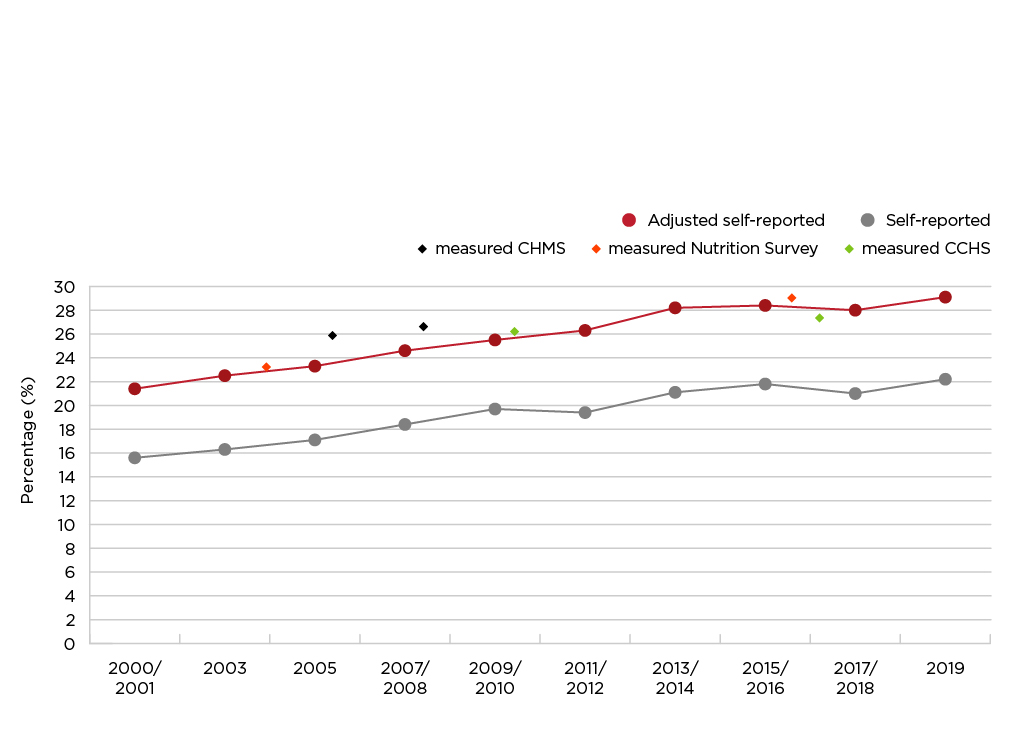

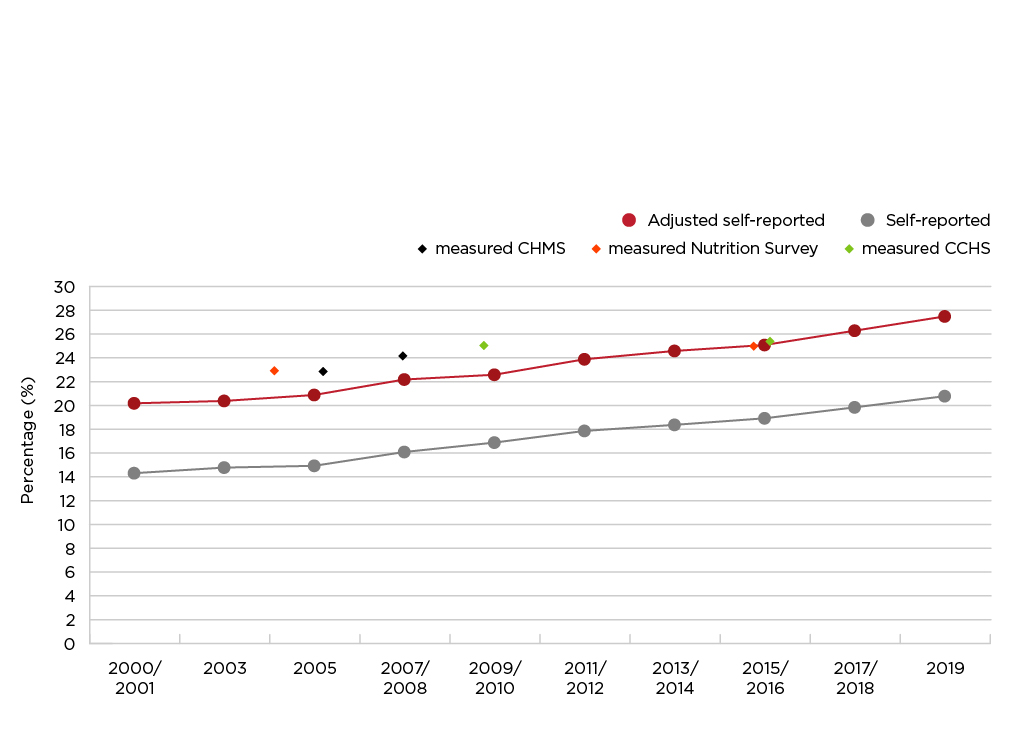

- Figure 4.1: Prevalence of self-reported, adjusted self-reported and measured obesity, male household population aged 18 to 79 years, Canada 2000-2001 to 2019

- Figure 4.2: Prevalence of self-reported, adjusted self-reported and measured obesity, female household population aged 18 to 79 years, Canada 2000-2001 to 2019

Section 1: What is obesity and how is it measured?

Key points

- The most used indicator of excess body fat is the body mass index (BMI), which is a measure of an individual's weight in relation to their height.

- The Canadian Guidelines for Body Weight Classification in Adults classify individuals aged 18 years or older into six BMI categories, each representing a different level of health risk.

- The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends age- and sex-specific categories for calculating BMI for children and youth.

- A population-based surveillance of BMI can provide information on trends over time and assist in the development and evaluation of intervention programs.

What is obesity?

The term "obesity" describes a medical condition where excess body fat threatens health Footnote 17. Individuals with excess body fat have an elevated risk of diseases such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, osteoarthritis and several types of cancer Footnote 2Footnote 18, and mental health conditions such as depression Footnote 1Footnote 18.

How is obesity measured?

BMI is the indicator most used by surveillance systems to track excess body fat within a population. It is a measure of an individual's weight in relation to their height (weight divided by height squared—weight (kg)/height(m2)) Footnote 19.

There are six BMI categories that classify people aged 18 years or older. Each represent a different level of health risk: underweight, normal weight, overweight, obesity class I, obesity class II, and obesity class III (see Box 1. BMI classification for adults). These categories are based on Canadian Guidelines for Body Weight Classification in Adults Footnote 20, and are aligned with those of the WHO Footnote 21.

| Classification | BMI category

(kg/m2) |

Risk of developing health problems |

|---|---|---|

| Underweight | < 18.5 | Increased |

| Normal weight | 18.5 to < 25.0 | Least |

| Overweight | 25.0 to < 30.0 | Increased |

| Obesity | ≥ 30.0 | |

| Obesity ≥ 30.0 (kg/m2) | ||

| Class I | 30.0 to < 35.0 | High |

| Class II | 35.0 to < 40.0 | Very high |

| Class III | ≥ 40.0 | Extremely high |

Some articles have been discussing the need to review the BMI cut-off points or the way BMI is measured since it does not consider age, gender, ethnicities and indigenous status, but recommendations by the WHO have yet to be emitted Footnote 22Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26. At the present, these BMI cut-offs remain the best measure for obesity at a population level. |

||

This report uses the Canadian Guidelines to classify adults aged 18 years or older (excluding pregnant women) according to BMI Footnote 20.

Since children and youth grow at varying rates, WHO recommends age- and sex-specific cut-points. These cut-points are employed to calculate BMI for these groups (see Box 2. BMI classification for children and youth). For 5- to 17-year-olds, there are four classification categories (thin, normal weight, overweight, and obesity); for children younger than 5 years, an additional "at risk of overweight" category is used. For this report, the WHO cut-offs were used to classify children and youth aged 17 or younger (215 months or less) Footnote 11Footnote 12Footnote 13. Although the WHO cut-offs extend to age 19 years, for those aged 18 years or older (216 months or older), the adult classification was applied.

Box 2. BMI classification for children and youth

BMI calculation for children and youth is the same as for adults (weight divided by height squared). However, due to varying growth rates, cut-points are age- and sex-specific. The Public Health Agency of Canada calculates prevalence estimates of overweight and obesity based on BMI categories specified by the WHO Footnote 9Footnote 11.

In 2006, the WHO released international growth standards for children younger than 5 years (60 months or younger) Footnote 21. These standards are based on a cohort of children raised in desirable conditions that include breastfeeding, a good diet and a non-smoking mother, conditions considered optimal for healthy growth Footnote 11. In 2007, the WHO produced growth references for 5- to 19-year-olds. (61 to 228 months) Footnote 12. By 2010, several Canadian professional associations had recommended to employ the WHO references to monitor children's growth Footnote 27.

The WHO categories for classifying children younger than 5 years (60 months or younger) as having a BMI in the overweight or obesity category differ from those for children aged 5 years or older (61 months or older) Footnote 13. For both age groups, classification is based on growth charts specifying mean BMIs and standard deviations (SDs) by age in months. The approach for children younger than 5 years includes an "at risk of overweight" category, which lessens the likelihood that they will be classified in the obesity category during a period of rapid growth Footnote 13. Because of the difference in classification categories, the WHO does not recommend combining the younger and older age groups.

The following categories and SD values (based on the WHO cut-offs and SDs) Footnote 11Footnote 12Footnote 13 are used in the classification systems for children aged 60 months or younger and children aged 61 months or older:

| BMI category | 60 months or younger | 61 months or older |

|---|---|---|

| Thin | ≥ 2 SD below the mean | ≥ 2 SD below the mean |

| Normal weight | < 2 SD below the mean and

≤ 1 SD above the mean |

< 2 SD below the mean and

≤ 1 SD above the mean |

| At risk of overweight | > 1 SD above the mean and ≤ 2 SD above the mean | Category not applicable |

| Overweight | > 2 SD above the mean and ≤ 3 SD above the mean | > 1 SD above the mean and ≤ 2 SD above the mean |

| Obesity | > 3 SD above the mean | > 2 SD above the mean |

SD=standard deviation from the age-/sex-specific WHO growth chart mean |

||

Other measures of excess body fat

BMI does not distinguish between body fat and lean body mass (muscle), and it gives no information about the distribution of body fat or body shape Footnote 19Footnote 28. Abdominal obesity, a measure of body fat distribution, has shown to be associated with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease mortality Footnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 34. Measures of abdominal obesity may provide added discriminatory power in predicting obesity-related disease Footnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 34. Even among individuals whose BMI is in the normal weight category, abdominal fat has been associated with cardiovascular disease risk-factors Footnote 35. For clinical settings, it is recommended that waist circumference be measured as well as BMI, particularly for people with a BMI in the normal, overweight, or obese class I categories Footnote 36. Among adults with a BMI in obese class II and class III categories, waist circumference measurements are nearly all in the high health risk waist circumference group. For people aged 18 years or older, the WHO Footnote 37, Health Canada Footnote 38, and Obesity Canada Footnote 36 classify waist circumference into three health-risk categories Footnote 39 (see Box 3. Waist circumference health-risk categories for adults).

Several techniques for measuring body fat are more accurate than BMI such as underwater weighing (densitometry), dual energy X-ray absorptiometry, and magnetic resonance imaging Footnote 19Footnote 28. These procedures are complex, expensive, and not practical for clinical settings or for surveillance. They confirm the accuracy of simpler methods, such as BMI, in research studies. BMI has been found to be strongly correlated with body fat as measured by these more complex methods (which are considered to be the "gold standard"), but does have its limitations Footnote 7Footnote 19Footnote 28.

| Waist circumference health-risk | Waist circumference measurement | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |

| Low-risk | < 94.0 cm | < 80.0 cm |

| Increased-risk | 94.0 to < 102.0 cm | 80.0 to < 88.0 cm |

| High-risk | ≥ 102.0 cm | ≥ 88.0 cm |

Although these supplemental techniques (for example, waist circumference, densitometry, and magnetic resonance imaging) provide valuable insights, BMI remains the preferred measure for population surveillance and epidemiologic studies, owing to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and the ease with which it can be estimated.

Health risks associated with elevated BMI

Among adults, obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) has been associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, asthma, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, chronic back pain, and several types of cancer Footnote 2. As well, a BMI in the overweight category (BMI 25.0-29.9 kg/m2) has been associated with a higher likelihood of these diseases Footnote 2. Research has also revealed relationships between excess body fat and mental health conditions such as mood disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, binge eating disorder, and schizophrenia Footnote 1.

Severe obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2, as defined by Health Canada and WHO guidelines Footnote 38 presents the greatest health risk, particularly for type 2 diabetes (5.1 times the risk compared to normal BMI) and cardiovascular disease (2.53 to 3.14 times the risk compared to normal BMI) Footnote 40Footnote 41. Although the prevalence of severe obesity is low, the associated health care expenditures are disproportionately high Footnote 42.

The association between BMI and mortality is less conclusive. Some studies Footnote 43Footnote 44Footnote 45Footnote 46Footnote 47Footnote 48 have found that that people with a BMI in the overweight category are at decreased risk of all-cause mortality, compared with a BMI in the normal weight category. The obesity paradox describes this counterintuitive relationship. Methodological shortcomings in the research reporting these results, such as reverse causation and failure to account for confounding variables, are likely at the root of this unexpected association. This relationship is further complicated by BMI failing to distinguish between body fat and fat-free, lean muscle mass. The BMI "overweight" category includes individuals whose BMI value results from higher levels of body fat but also individuals whose BMI value results from higher fat-free, lean muscle mass Footnote 49. Misclassification through lean muscle mass is most common in certain clinical populations Footnote 50, and individuals with physical fitness requirements (for example, soldiers Footnote 51 or athletes Footnote 52). See Appendix A: BMI, mortality, and the obesity paradox.

Among children, the earlier onset of diseases – including type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, hypertension, and a range of cancers – has been associated with high BMI Footnote 3Footnote 4. Evidence also suggests that a high BMI in childhood can have psychosocial impact, such as depression, lower self-esteem, and behavioral disorders Footnote 5Footnote 6. As well, obesity in childhood and adolescence is strongly associated with obesity in adulthood Footnote 7Footnote 8.

Estimates for the direct (that is, costs associated with treatment and condition management) and indirect costs (that is, costs associated with life years lost to premature death and short- or long-term disability) of obesity are high Footnote 53. A recent Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report found that, on average, countries would spend 8.4% of total health expenditures treating the consequences of overweight and obesity between 2020 and 2050 Footnote 53. OECD predicted average spending associated with management of obesity and overweight is approximately double the estimated healthcare costs of overweight and obesity in 2006 of 4.1% Footnote 54. Obesity and its health consequences are associated with economic effects such as decreased work productivity and workforce participation. As mentioned in the OECD report, at a macroeconomic level, such an impact on the labour market affects the GDP of a country and increases fiscal pressure Footnote 53.

Surveillance

Regular surveillance of BMI trends over time is essential for understanding populations at risk, identifying areas for intervention, and evaluating the effectiveness of policies and programs.

BMI remains the preferred measure for population surveillance and epidemiologic studies, owing to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and the ease with which it can be estimated.

At the national level, several Statistics Canada surveys routinely provide surveillance data for BMI calculation. However, because height and weight data are not collected in the same way, different surveys yield different estimates. See Section 4: Data Sources and Methods for more information.

Self-reported versus measured BMI

BMI may be calculated using information from surveys that ask respondents to self-report their height and weight, or from surveys with interviewers trained to take precise measurements. To estimate BMI for children, surveys may ask parents to report their child's height and weight. However, the accuracy of BMI estimates based on parent-reported data has been questioned Footnote 55.

Adults’ self-reports underestimate weight and overestimate height Footnote 10. Consequently, prevalence estimates of overweight and obesity calculated from self-reported data are significantly lower than estimates based on measured data. Researchers in Canada have sought to establish equations that correct such self-reports to obtain more accurate estimates of BMI from self-reported data. See Appendix B: Correction equations for adjusting BMI in the CCHS based on self-/parent-reported height and weight. In this report, BMIAdjSR refers to BMI based on self-reported values that have been adjusted to correct for biases.

Similar to adults, BMI classification of youth, based on self-reported height and weight, underestimates the prevalence of overweight and obesity Footnote 14Footnote 15. For youth, however, females underestimate their weight more than males. Furthermore, for both sexes, those with a BMI classified as in the overweight/obesity range underestimate their weight more than youth with a BMI in the normal weight category Footnote 15. More work is required to determine if developing correction equations for youth is feasible.

For children, self- and parent-reported height and weight often result in substantial misclassification of BMI Footnote 55. Moreover, while misclassification of BMI based on adults' self-reported height and weight tends to be consistent and predictable, this is not true for children's BMI based on parent-reported height and weight Footnote 55. This inconsistency has thwarted attempts to devise correction equations to adjust BMI based on parent reports.

Section 2: Adult obesity

Key points

- In 2021, based on adjusted self-reported height and weight, 29.5% of Canadian adults had a BMIAdjSR classified as obesity.

- An additional 35.5% had a BMIAdjSR classified as overweight.

- An estimated 3.7% of adults had a BMIAdjSR that placed them in obesity class III, the category associated with extremely high health risk.

- Although there was no difference in the proportion of men compared to women with a BMIAdjSR in the obesity range, men were more likely than women to have a BMIAdjSR in the overweight range (39.7% versus 31.3%).

- The lowest prevalence of obesity was among the youngest (18 to 34 years) and oldest (80 years or older) age groups: 22.5% and 21.2%, respectively.

- Among women, low household income was associated with a significantly higher prevalence of obesity than the highest household income group (30.8% versus 26.6%). Among men, no significant differences were seen across the different household incomes.

- For both sexes, the lowest prevalence of obesity was among those in the highest household education group (post-secondary graduate): 28.3% versus 36.7% and 35.1% among those with only secondary school graduation, or less than secondary school graduation.

- Obesity was significantly more common among adults in rural areas (33.6%) than in urban ones (28.6%).

- Between 2000-2001 and 2019-2020, the prevalence of obesity among adults based on self-reported data rose from 20.6% to 28.2%; increases were similar among men and women.

- A significant upward trend in the prevalence of obesity was observed among adults in all age groups, all household income quintiles, and all levels of household education.

- The prevalence of obesity class III among adults doubled from 2000-2001 to 2019-2020.

- Initial results from 2021 show increases in the prevalence of obesity during the COVID-19 pandemic, however more data is required to determine trends.

Reminder: BMIAdjSR refers to BMI based on self-reported values that have been adjusted to correct for biases.

Box 4. Data sources

Recent estimates of adult BMI are available from three national surveys:

- The Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) collects self-reported height and weight on adults aged 18 and over. The most recent, complete cycle, 2021, provides estimates for Canada, excluding the territories. The 2019-2020 CCHS provides the most recent data for the provinces and the territories.

- The Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS) collects measured height, weight, and waist circumference on adults aged 18 to 79. The most recent cycles (4, 5 and 6) were conducted in 2014-2015, 2016-2017, and 2018-2019. For this report, results from these three cycles (combined 2014-2019) were combined to report more stable estimates.

- The CCHS–Nutrition Focus (CCHS-Nutrition), which was conducted in 2004 and 2015, includes measured height and weight on adults aged 18 and over.

Most estimates in this section are based on adjusted self-reported BMI data (BMIAdjSR) from the 2021 CCHS. See Appendix B: Correction equations for adjusting BMI in the CCHS based on self-/parent-reported height and weight. CCHS 2019-2020 data were used for the analyses of provincial and territorial variations.

Although measured BMI data are available from the CHMS, adjusted self-reported data from the CCHS survey are used instead to obtain the largest sample, allowing for detailed granular estimates. The extent to which adjusted self-reported estimates align with estimates based on physical measurements is indicated in Figure 2.1, which presents estimates of the prevalence of obesity among adults aged 18 to 79 years from three surveys with comparable time frames: the combined 2015-2016 CCHS, the 2015 CCHS—Nutrition, and the 2014-2015/2016-2017 CHMS. Estimates from the 2015-2016 CCHS were adjusted (BMIAdjSR) to correct for the bias in BMI derived from self-reported data. For both men and women, estimates from the three surveys are similar.

Figure 2.1 - Text description

| Both Sexes | Males | Females | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% Confidence Interval |

% | 95% Confidence Interval |

% | 95% Confidence Interval |

|

| 2015/2016 (adjusted self-report) | 26.7 | (26.3, 27.2) | 28.4 | (27.6, 29.1) | 25.1 Footnote a | (24.4, 25.7) |

| 2015 (measured) | 27.0 | (25.2, 28.8) | 28.8 | (26.1, 31.4) | 25.2 Footnote a | (22.9, 27.5) |

| 2014-2015/2016-2017 (measured) | 27.5 | (24.9, 30.1) | 27.7 | (24.5, 30.8) | 27.4 | (24.5, 30.3) |

Data sources: 2015/2016 Canadian Community Health Survey (share file), 2015 Canadian Community Health Survey—Nutrition (share file), 2014-2015/2016-2017 Canadian Health Measures Survey (Cycles 4 and 5). Footnotes

|

||||||

Prevalence of obesity and overweight among adults

In 2021, 29.5% of Canadian adults were classified as having a BMIAdjSR that set them in the obesity category (see Table A2.2 in Appendix C). An estimated 18.9% had a BMIAdjSR in obesity class I (high risk); 6.9%, in class II (very high risk); and 3.7%, in class III (extremely high risk) (see Figure 2.2). See Box 1. BMI classification for adults in Section 1 for details regarding the categories.

Age and sex

In 2021, for both sexes, 65.0% had a BMIAdjSR classified as overweight/obese while 29.5% were classified in the obesity category and 35.5% were classified in the overweight category. When comparing men and women, there were significantly more men than women in the overweight/obesity category: 69.8% versus 60.1% (see Table A2.2 in Appendix C). For the BMIAdjSR in the obesity range, there were no differences between men and women. However, more men than women were in the overweight category: 39.7% versus 31.3%. Another significant difference than can be observed between men and women is for the obesity class I where a higher percentage of men than women are classified in that category (19.9% versus 18.0%) (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 - Text description

| Underweight (< 18.5) | Normal weight (18.5 to 24.9) | Overweight (25.0 to 29.9) | Obesity Class I (30.0 to 34.9) | Obesity Class II (35.0 to 39.9) | Obesity Class III (≥ 40.0) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both | 1.7 | 33.4 | 35.5 | 18.9 | 6.9 | 3.7 |

| Males | 1.3 Footnote E | 28.9 | 39.7 | 19.9 | 6.6 | 3.6 |

| Females | 2.0 Footnote a | 37.8 Footnote a | 31.3 Footnote a | 18.0 Footnote a | 7.1 | 3.8 |

Data source: 2021 Canadian Community Health Survey (share file). Footnotes

Note: The percentages are based on records with a valid value for BMI. Excluded from the total population counts are pregnant women (n=284, estimated population 278.2 thousand) and individuals with a missing value for BMI (n=828 for males, estimated population 613.9 thousand; n=1,138 for females, estimated population 812.9 thousand). |

||||||

Overall, the prevalence of adjusted self-reported obesity is significantly lower for those aged between 18 and 34 years (22.5%) and 80 years or older (21.2%) (see Figure 2.3). The same observation can be made when looking at men and women separately. For men specifically, the prevalence of obesity was lower for those in the 65 to 79 age group when compared to the 50 to 64 age group (30.9% versus 36.4%). For women, those age groups had similar obesity prevalence. Among men, the prevalence of obesity was significantly higher than women between the ages of 50 and 64 years: 36.4% versus 31.1%. For more information, see Table A2.3 in Appendix C.

The low prevalence of obesity among the elderly (21.2%) should be interpreted cautiously. As people age, they tend to lose muscle mass, which is often replaced with fat Footnote 56Footnote 57. Therefore, even if an individual's BMI does not change, increases in fat may raise their health risk.

Figure 2.3 - Text description

| Age group (in years) | Both Sexes | Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% |

% | 95% |

% | 95% |

|

| Total (18 or older) | 29.5 | (28.6, 30.3) | 30.1 | (28.9, 31.3) | 28.9 | (27.8, 30.0) |

| 18 to 34 | 22.5 Footnote b | (20.7, 24.3) | 22.3 Footnote b | (19.8, 24.8) | 22.7 Footnote b | (20.3, 25.2) |

| 35 to 49 | 32.9 | (31.1, 34.6) | 33.8 | (31.3, 36.3) | 31.9 | (29.7, 34.1) |

| 50 to 64 (reference) | 33.7 | (32.1, 35.3) | 36.4 | (34.0, 38.8) | 31.1 Footnote a | (28.9, 33.3) |

| 65 to 79 | 31.5 | (30.1, 32.8) | 30.9 Footnote b | (28.8, 32.9) | 32.0 | (30.1, 33.8) |

| 80 or older | 21.2 Footnote b | (18.7, 23.7) | 19.6 Footnote b | (15.9, 23.3) | 22.4 Footnote b | (19.0, 25.9) |

Data source: 2021 Canadian Community Health Survey (share file). Footnotes

|

||||||

Waist circumference

Based on CHMS data from 2014 to 2019, 41.9% of adults aged 18 to 79 years had a waist circumference in the high-risk range (see Table 2a). An additional 21.9% were in the increased-risk category. Overall, 63.8% of adults had a waist circumference associated with high health risk. In all age categories, significantly more women had a high-risk waist circumference compared to men: 29.5% versus 21.9% for age 18 to 34; 50.1% versus 31.6% for age 35 to 49; 61.3% versus 39.5% for age 50 to 64; and 66.5% versus 50.3% for age 65 to 79.

Measures of central obesity can be helpful in assessing health risk at older ages Footnote 19Footnote 28Footnote 47. Waist circumference data from the CHMS show that the prevalence of high-risk measurements rose with age. The percentage of men with a high-risk waist circumference increased from 21.9% at ages 18 to 34 years to 50.3% at ages 65 to 79 years (the oldest age group in the CHMS); among women, percentages were higher, rising from 29.5% at ages 18 to 34 years to 66.5% at ages 65 to 79 years (see Table 2a).

| Age group (in years) | Both Sexes | Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% Confidence Interval | % | 95% Confidence Interval | % | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Total (18-79) | ||||||

| Low-risk WC | 36.2 | (33.4, 39.0) | 42.6 | (39.9, 45.2) | 29.8 Footnote b | (25.6, 34.0) |

| Increased-risk WC | 21.9 | (20.3, 23.5) | 23.6 | (21.2, 26.1) | 20.1 Footnote b | (17.8, 22.3) |

| High-risk WC | 41.9 | (38.5, 45.3) | 33.8 | (30.5, 37.1) | 50.1 Footnote b | (45.8, 54.5) |

| Age 18-34 | ||||||

| Low-risk WC | 56.7 Footnote a | (52.1, 61.2) | 62.4 Footnote a | (56.8, 67.9) | 50.6 Footnote aFootnote b | (42.4, 58.9) |

| Increased-risk WC | 17.7 Footnote a | (14.7, 20.7) | 15.7 Footnote a | (12.5, 19.0) | 19.8 | (14.4, 25.3) |

| High-risk WC | 25.6 Footnote a | (22.1, 29.1) | 21.9 Footnote a | (17.4, 26.5) | 29.5 Footnote aFootnote b | (23.6, 35.5) |

| Age 35-49 (reference) | ||||||

| Low-risk WC | 36.2 | (31.0, 41.4) | 42.7 | (36.8, 48.7) | 29.7 Footnote b | (23.1, 36.2) |

| Increased-risk WC | 22.9 | (20.3, 25.5) | 25.7 | (21.4, 29.9) | 20.2 | (16.7, 23.6) |

| High-risk WC | 40.9 | (35.5, 46.2) | 31.6 | (25.3, 37.9) | 50.1 Footnote b | (43.9, 56.4) |

| Age 50-64 | ||||||

| Low-risk WC | 24.5 Footnote a | (21.4, 27.7) | 31.2 Footnote a | (26.5, 35.9) | 17.8 Footnote aFootnote b | (14.2, 21.3) |

| Increased-risk WC | 25.2 | (22.3, 28.0) | 29.4 | (24.6, 34.1) | 21.0 Footnote b | (16.4, 25.5) |

| High-risk WC | 50.3 Footnote a | (46.3, 54.4) | 39.5 Footnote a | (33.6, 45.3) | 61.3 Footnote aFootnote b | (56.7, 65.8) |

| Age 65-79 | ||||||

| Low-risk WC | 19.8 Footnote a | (16.5, 23.2) | 25.1 Footnote a | (20.3, 30.0) | 14.8 Footnote aFootnote b | (10.5, 19.1) |

| Increased-risk WC | 21.6 | (18.7, 24.6) | 24.6 | (20.4, 28.8) | 18.8 Footnote b | (15.6, 21.9) |

| High-risk WC | 58.5 Footnote a | (54.0, 63.1) | 50.3 Footnote a | (44.9, 55.7) | 66.5 Footnote aFootnote b | (61.4, 71.5) |

Data sources: 2014-2015, 2016-2017, and 2018-2019 Canadian Health Measures Survey (Cycles 4, 5, and 6).

WC=waist circumference. |

||||||

Household income and education

Associations between household income and obesity differed for men and women (see Figure 2.4). Women in the lowest income quintiles had the highest prevalence of obesity (30.8%), which was significantly higher than women in the highest income quintile (26.6%). The prevalence varied relatively little among women in quintiles two to four (ranging from 28.4% to 29.5%). By contrast, men in the highest income quintile have a significantly higher prevalence of obesity than women in the same quintile (31.2% versus 26.6%). Among men, no differences in the distribution of BMIAdjSR appeared across income quintiles. For information on the confidence intervals (CI), see Table A2.4 in Appendix C.

Figure 2.4 - Text description

| Household income quintile | Both Sexes | Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% |

% | 95% |

% | 95% |

|

| Quintile 1 (Lowest) | 29.7 | (27.8, 31.5) | 28.3 | (25.4, 31.2) | 30.8 Footnote b | (28.5, 33.2) |

| Quintile 2 | 29.2 | (27.4, 31.0) | 30.0 | (27.2, 32.8) | 28.4 | (26.2, 30.7) |

| Quintile 3 | 29.2 | (27.3, 31.0) | 28.8 | (26.3, 31.4) | 29.5 | (26.9, 32.0) |

| Quintile 4 | 30.2 | (28.4, 32.1) | 31.6 | (28.9, 34.3) | 28.8 | (26.1, 31.4) |

| Quintile 5 (reference) | 29.1 | (27.4, 30.9) | 31.2 | (28.8, 33.6) | 26.6 Footnote a | (24.4, 28.8) |

Data source: 2021 Canadian Community Health Survey (share file). Footnotes

|

||||||

For both sexes, the lowest prevalence of obesity was among those in the highest household education group (post-secondary graduate): 28.3% versus 36.7% (only secondary school graduation) and 35.1% (less than secondary school graduation). See Table A2.5 in Appendix C or look at Figure 2.5 below. Significantly more men than women with a post-secondary degree, were classified in the obesity category: 29.2% versus 27.3%.

Figure 2.5 - Text description

| Highest level of education in the household | Both Sexes | Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% |

% | 95% |

% | 95% |

|

| Less than secondary school graduation | 35.1 Footnote b | (31.9, 38.2) | 33.5 | (29.1, 37.9) | 36.5 Footnote b | (32.1, 40.9) |

| Secondary school graduation | 36.7 Footnote b | (34.4, 39.0) | 36.5 Footnote b | (32.9, 40.1) | 36.9 Footnote b | (33.9, 39.8) |

| Post-secondary certificate, diploma or university degree (reference) | 28.3 | (27.4, 29.2) | 29.2 | (27.9, 30.5) | 27.3 Footnote a | (26.2, 28.5) |

Data source: 2021 Canadian Community Health Survey (share file). Footnotes

|

||||||

Box 5. International Surveillance

International surveillance has revealed a negative association between socioeconomic status (SES) and BMI in higher-income countries, but a positive association in lower-income countries. This is called the "reversal hypothesis," for which several explanations have been proposed. In affluent countries, the higher prevalence of obesity among those with low SES may be due to lack of funds to buy healthy foods. In poorer countries, the lower prevalence of obesity among those with low SES may reflect limited access to any food Footnote 58. As well, in higher-income countries, cultural values about the desirability of being thin may motivate high-SES individuals to avoid weight gain. By contrast, in lower-income countries, excess weight may be seen as a status symbol.

Regional variations

In 2019-2020, the prevalence of adult obesity varied across provinces and territories, ranging from 23.2% in British Columbia to 40.4% in Newfoundland and Labrador (see Table 2b). Provincial prevalence estimates of obesity were similar when differences in the age-distribution between provinces were taken into consideration (see Table A2b in Appendix C).

| Province | Both Sexes | Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% |

% | 95% |

% | 95% |

|

| Total (18+) | 28.2 | (27.7, 28.7) | 28.7 | (28.0, 29.5) | 27.7 Footnote a | (26.9, 28.4) |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 40.4 Footnote b | (37.4, 43.4) | 41.2 Footnote b | (37.0, 45.4) | 39.5 Footnote b | (35.6, 43.4) |

| Prince Edward Island | 36.2 Footnote b | (32.4, 40.1) | 34.6 | (28.9, 40.2) | 37.9 Footnote b | (33.0, 42.9) |

| Nova Scotia | 34.8 Footnote b | (32.2, 37.4) | 35.2 Footnote b | (31.0, 39.4) | 34.5 Footnote b | (31.4, 37.5) |

| New Brunswick | 37.3 Footnote b | (34.7, 39.9) | 34.4 | (30.5, 38.4) | 40.2 Footnote aFootnote b | (36.6, 43.7) |

| Quebec | 26.2 Footnote b | (25.1, 27.4) | 26.9 | (25.3, 28.4) | 25.6 Footnote b | (24.1, 27.1) |

| Ontario | 28.3 | (27.3, 29.2) | 28.4 | (27.0, 29.8) | 28.1 | (26.9, 29.4) |

| Manitoba | 32.7 Footnote b | (30.5, 34.9) | 32.0 | (28.7, 35.2) | 33.5 Footnote b | (30.5, 36.4) |

| Saskatchewan | 35.6 Footnote b | (33.2, 37.9) | 37.0 Footnote b | (33.5, 40.5) | 34.0 Footnote b | (30.7, 37.4) |

| Alberta | 29.7 | (28.2, 31.2) | 31.5 | (29.3, 33.8) | 27.8 Footnote a | (25.8, 29.9) |

| British Columbia | 23.2 Footnote b | (21.8, 24.6) | 24.4 Footnote b | (22.4, 26.5) | 22.0 Footnote b | (20.1, 23.8) |

| Yukon | 33.3 | (27.8, 38.9) | 32.6 | (24.0, 41.3) | 34.0 | (26.3, 41.8) |

| Northwest Territories | 36.7 | (30.4, 43.0) | 34.7 | (27.3, 42.0) | 39.0 | (29.7, 48.2) |

| Nunavut | 33.2 | (24.5, 41.8) | 23.0 Footnote E | (11.3, 34.8) | 46.6 Footnote EFootnote a | (31.1, 62.1) |

Data source: 2019-2020 Canadian Community Health Survey (share file).

|

||||||

In 2021, obesity was more common among adults in rural areas (33.6%) than in urban centres (28.6%). For both sexes, the observation was the same, males: 35.0% versus 29.0%; females: 32.0% versus 28.3% (See Table A2.6 in Appendix C or look at Figure 2.6 below). Furthermore, in rural areas, the prevalence of self-reported obesity is significantly higher in men than women.

Figure 2.6 - Text description

| Urban/rural | Both Sexes | Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% |

% | 95% |

% | 95% |

|

| Total | 29.5 | (28.6, 30.3) | 30.1 | (28.9, 31.3) | 28.9 | (27.8, 30.0) |

| Urban (reference) | 28.6 | (27.7, 29.6) | 29.0 | (27.6, 30.4) | 28.3 | (27.0, 29.5) |

| Rural | 33.6 Footnote b | (32.1, 35.1) | 35.0 b | (32.8, 37.3) | 32.0 Footnote aFootnote b | (30.1, 34.0) |

Data source: 2021 Canadian Community Health Survey (share file). Footnotes

|

||||||

The Canadian Risk Factor Atlas (CRFA) examines the prevalence of obesity and overweight in all provinces, territories, health regions, census metropolitan areas, and large census agglomerations in Canada. To allow for information to be presented at a range of geographic levels, including distributions by age, sex, income and education, data from four cycles of the CCHS (2015-2018) were combined Footnote 59. Figure 2.7 shows the distribution of obesity by health region among adults, using data from the CRFA tool. For additional information, see Table A2.7 in Appendix C.

Figure 2.7 - Text description

Geography |

Prevalence (%) | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | 26.7 | (26.3, 27.1) |

| Bas-Saint-Laurent | 25.3 | (22.3, 28.3) |

| Brant County HU | 31.9 | (28.3, 35.5) |

| Calgary Zone | 24.2 | (22.7, 25.7) |

| Capitale-Nationale | 22.4 | (20.4, 24.3) |

| Central Regional | 40.3 | (36.8, 43.9) |

| Central Vancouver Island HSDA | 22.9 | (20.0, 25.8) |

| Central Zone | 33.6 | (31.5, 35.8) |

| Chatham-Kent HU | 37.9 | (33.9, 41.9) |

| Chaudière-Appalaches | 22.5 | (20.1, 25.0) |

| City of Hamilton HU | 27.2 | (23.9, 30.5) |

| City of Ottawa HU | 23.1 | (20.9, 25.4) |

| City of Toronto HU | 19.6 | (17.9, 21.3) |

| Côte-Nord | 34.9 | (31.5, 38.3) |

| Cypress RHA | 36.6 | (31.3, 41.9) |

| Durham Regional HU | 29.2 | (25.8, 32.5) |

| East Kootenay HSDA | 29.0 | (24.3, 33.7) |

| Eastern Ontario HU | 32.6 | (28.6, 36.6) |

| Eastern Regional | 38.7 | (36.0, 41.3) |

| Edmonton Zone | 27.5 | (25.7, 29.4) |

| Elgin-St Thomas HU | 36.6 | (33.1, 40.1) |

| Five Hills RHA | 30.0 | (25.4, 34.6) |

| Fraser East HSDA | 30.3 | (27.1, 33.4) |

| Fraser North HSDA | 21.6 | (18.5, 24.6) |

| Fraser South HSDA | 26.3 | (23.7, 29.0) |

| Gaspésie - Îles-de-la-Madeleine | 31.0 | (28.1, 33.8) |

| Grey Bruce HU | 34.4 | (31.0, 37.9) |

| Haldimand-Norfolk HU | 28.7 | (25.6, 31.8) |

| Haliburton, Kawartha, Pine Ridge District HU | 34.7 | (30.8, 38.5) |

| Halton Regional HU | 23.9 | (21.5, 26.4) |

| Hastings and Prince Edward Counties HU | 35.2 | (31.4, 38.9) |

| Heartland RHA | 35.9 | (30.2, 41.7) |

| Huron County HU | 34.1 | (29.4, 38.9) |

| Interlake-Eastern Regional Health | 37.9 | (34.7, 41.2) |

| Kelsey Trail RHA | 37.6 | (30.2, 45.0) |

| Kingston, Frontenac and Lennox and Addington HU | 32.3 | (28.5, 36.1) |

| Kootenay-Boundary HSDA | 27.8 | (23.9, 31.7) |

| L'Abitibi-Témiscamingue | 34.0 | (31.3, 36.7) |

| L'Estrie | 26.4 | (24.2, 28.7) |

| L'Outaouais | 27.3 | (25.2, 29.4) |

| Labrador-Grenfell Regional | 46.1 | (42.3, 49.9) |

| Lambton HU | 30.5 | (26.9, 34.1) |

| Leeds, Grenville and Lanark District HU | 34.5 | (29.7, 39.4) |

| Mamawetan/Keewatin/Athabasca | 43.9 | (35.8, 52.1) |

| Mauricie et du Centre-du-Québec | 29.0 | (27.0, 30.9) |

| Middlesex-London HU | 26.5 | (23.4, 29.7) |

| Montérégie | 28.2 | (26.1, 30.3) |

| Northwest Territories | 40.2 | (36.9, 43.6) |

| Nunavut | 33.7 | (30.0, 37.5) |

| Niagara Regional Area HU | 29.8 | (26.7, 32.8) |

| Nord-du-Québec | 30.4 | (26.0, 34.7) |

| North Bay Parry Sound District HU | 31.7 | (28.3, 35.0) |

| North Shore/Coast Garibaldi HSDA | 16.0 | (12.5, 19.4) |

| North Vancouver Island HSDA | 29.6 | (26.4, 32.9) |

| North Zone | 39.2 | (36.8, 41.6) |

| Northeast HSDA | 36.8 | (31.4, 42.1) |

| Northern Interior HSDA | 32.4 | (28.8, 36.0) |

| Northern RHA | 40.3 | (36.7, 44.0) |

| Northwest HSDA | 32.1 | (27.0, 37.3) |

| Northwestern HU | 36.0 | (31.3, 40.7) |

| Okanagan HSDA | 24.9 | (21.7, 28.0) |

| Oxford County HU | 37.2 | (33.5, 40.8) |

| Peel Regional HU | 23.1 | (20.8, 25.4) |

| Perth District HU | 35.0 | (31.2, 38.8) |

| Peterborough County-City HU | 33.7 | (29.0, 38.4) |

| Porcupine HU | 38.8 | (34.0, 43.6) |

| Prairie Mountain Health | 37.0 | (33.6, 40.4) |

| Prairie North RHA | 32.9 | (29.1, 36.6) |

| Prince Albert Parkland RHA | 37.4 | (33.0, 41.8) |

| Prince Edward Island | 32.9 | (30.8, 35.0) |

| Regina Qu'Appelle RHA | 32.2 | (28.8, 35.5) |

| Région de Lanaudière | 28.9 | (25.8, 32.0) |

| Région de Laval | 25.2 | (22.9, 27.5) |

| Région de Montréal | 20.6 | (18.9, 22.3) |

| Région des Laurentides | 24.9 | (22.8, 26.9) |

| Renfrew County and District HU | 34.0 | (30.0, 38.0) |

| Richmond HSDA | 11.9 | (9.8, 14.0) |

| Saguenay - Lac-Saint-Jean | 24.5 | (21.8, 27.2) |

| Saskatoon RHA | 30.0 | (27.2, 32.8) |

| Simcoe Muskoka District HU | 31.7 | (28.3, 35.2) |

| South Vancouver Island HSDA | 19.9 | (17.3, 22.4) |

| South Zone | 32.6 | (30.2, 35.0) |

| Southern Health | 33.9 | (31.0, 36.7) |

| Sudbury and District HU | 33.0 | (29.8, 36.2) |

| Sun Country RHA | 34.9 | (30.7, 39.1) |

| Sunrise RHA | 41.9 | (36.6, 47.1) |

| The District of Algoma HU | 36.3 | (33.2, 39.4) |

| Thompson/Cariboo HSDA | 29.2 | (26.1, 32.3) |

| Thunder Bay District HU | 35.5 | (32.3, 38.7) |

| Timiskaming HU | 41.2 | (36.0, 46.4) |

| Vancouver HSDA | 11.6 | (9.7, 13.4) |

| Waterloo HU | 29.0 | (25.6, 32.3) |

| Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph HU | 29.0 | (26.1, 31.9) |

| Western Regional | 44.9 | (40.9, 48.9) |

| Windsor-Essex County HU | 32.7 | (29.6, 35.8) |

| Winnipeg RHA | 26.5 | (24.4, 28.5) |

| Yukon | 34.4 | (31.7, 37.2) |

| York Regional HU | 19.4 | (17.2, 21.7) |

| Zone 1 (Moncton area) | 37.9 | (34.3, 41.4) |

| Zone 1 - Western | 37.3 | (34.4, 40.3) |

| Zone 2 (Saint John area) | 38.2 | (34.2, 42.1) |

| Zone 2 - Northern | 37.7 | (34.4, 41.0) |

| Zone 3 (Fredericton area) | 37.0 | (33.3, 40.8) |

| Zone 3 - Eastern | 38.7 | (35.4, 42.0) |

| Zone 4 (Edmundston area) | 38.3 | (33.2, 43.5) |

| Zone 4 - Central | 30.5 | (28.1, 32.8) |

| Zone 5 (Campbellton area) | 39.7 | (32.3, 47.1) |

| Zone 6 (Bathurst area) | 33.2 | (29.5, 36.9) |

| Zone 7 (Miramichi area) | 41.2 | (35.4, 47.0) |

Data sources: 2015-2018 Canadian Community Health Survey. |

||

Indigenous Status

The CCHS lacks data collection among First Nations living on-reserve and Inuit living in Inuit Nunangat. Although CCHS provides information for self-identified First Nations living off-reserve, Inuit living outside of Inuit Nunangat, and Métis peoples, this data is known to have limitations. Table A2.16 in Appendix C presents the available CCHS data on Indigenous Peoples. However, it is recognized that the estimates provided do not deliver a full picture and do not address the wider needs for Indigenous peoples, primarily closing health gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous persons, as per the Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action report Footnote 60. This report acknowledges the data gaps associated with obesity in Indigenous Peoples in addition to the lack of data on risk factors such as socioeconomic factors and the effects of colonialization.

Additional information on the prevalence of obesity among Indigenous peoples can be found in the Key Health Inequalities in Canada: A National Portrait – 2018 Footnote 61. This report sought to estimate the scale of inequality between Indigenous Peoples and the non-Indigenous population using data from 1) the 2008-2010 First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey (RHS) for First Nations people living on-reserve and 2) the 2010-2014 CCHS for the non-Indigenous population and for First Nations people living off-reserve, Inuit living outside of Inuit Nunagat and Métis peoples. The First Nation Information Governance Centre (FNIGC) provided the analysis and data on health inequalities with respect to First Nations living on reserve Footnote 61. New data on measured obesity in Indigenous Peoples aged 18 to 79 years old is available in the Health Inequalities Data Tool Footnote 62, which combines the recent CHMS Cycles (2014 to 2019).

Other social determinants of health

The Health Inequalities Data Tool Footnote 62 presents data on over 100 indicators, including obesity, stratified by life course stage and by a range of social and economic characteristics. These socioeconomic determinants include, but are not limited to sexual orientation, cultural/racial background, employment status, occupation, etc. For adults, self-reported and measured obesity are presented by combining CCHS cycles (2015 to 2018) and CHMS cycles (2016 to 2019), respectively. The Health Inequalities Data Tool also provides rate ratios, to show the strength of the association, and rate differences, to show excess risk among groups.

Trends over time

According to a 2016 report from the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration, from 1975 to 2014, the global age-standardized prevalence of adult obesity rose from 3.2% to 10.8% among men and from 6.4% to 14.9% among women Footnote 17Footnote 63. Compared with other OECD nations, the prevalence of obesity in Canada is high, however Canada's rate of growth is one of the slowest among OECD countries Footnote 64.

For the first time since 1978-1979, the 2004 CCHS—Nutrition provided nationally representative BMI estimates using measured height and weight data. Based on these data, a significantly higher percentage of adults were classified in the obesity category in 2004 (23.1%) than in 1978-1979 (14%) Footnote 65.

Trends since 2000

Based on self-reported height and weight

At the time of publication, data from 2021-2022 were not available, as such, trend estimation ranges from 2000-2001 to 2019-2020. Adjusted self-reported data (BMIAdjSR) from the CCHS surveys show that between 2000-2001 and 2019-2020, the prevalence of obesity among adults rose steadily from 20.6% to 28.2% (see Figure 2.8). For more details, see Table A2.8a in Appendix C. Increases were similar among men and women: from 21.2% to 28.7% and from 20.0% to 27.7%, respectively. For both sexes, a significant upward trend was observed for all age groups (see Figure 2.9), household income quintiles (see Figure 2.10), and household education levels (see Figure 2.11). Their corresponding tables (Table A2.9, A2.10 and A2.11) can be found in Appendix C. Canadians aged between 35 and 49 years old show the largest increase in obesity prevalence with a rise of 9.4%: 21.6% in 2000-2001 to 31.0% in 2019-2020. For household income quintiles, the largest increase in the prevalence of self-reported obesity is seen in those in the highest income quintile (19.8% in 2000-2001 to 27.7% in 2019-2020). Regarding the household education levels, obesity prevalence increased by 11% between 2000 and 2020 (21.3% in 2000-2001 versus 32.3% in 2019-2020) for households where the highest level of education was secondary school graduation.

Figure 2.8 - Text description

| Time period | Both Sexes | Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% |

% | 95% |

% | 95% |

|

| 2000-2001 | 20.6 | (20.2, 21.0) | 21.2 | (20.6, 21.7) | 20.0 | (19.5, 20.5) |

| 2003 | 21.2 | (20.8, 21.6) | 22.2 | (21.7, 22.8) | 20.1 | (19.6, 20.6) |

| 2005 | 21.9 | (21.5, 22.3) | 23.1 | (22.5, 23.6) | 20.7 | (20.2, 21.2) |

| 2007-2008 | 23.2 | (22.8, 23.6) | 24.3 | (23.8, 24.9) | 22.1 | (21.6, 22.6) |

| 2009-2010 | 23.8 | (23.4, 24.3) | 25.2 | (24.6, 25.9) | 22.4 | (21.8, 23.0) |

| 2011-2012 | 24.8 | (24.3, 25.2) | 26.0 | (25.3, 26.6) | 23.6 | (22.9, 24.2) |

| 2013-2014 | 26.1 | (25.6, 26.6) | 27.9 | (27.1, 28.6) | 24.4 | (23.7, 25.0) |

| 2015-2016 | 26.4 | (26.0, 26.9) | 28.1 | (27.4, 28.8) | 24.8 | (24.1, 25.4) |

| 2017-2018 | 26.9 | (26.4, 27.4) | 27.9 | (27.2, 28.6) | 25.9 | (25.3, 26.6) |

| 2019-2020 | 28.2 | (27.7, 28.7) | 28.7 | (28.0, 29.5) | 27.7 | (26.9, 28.4) |

Data sources: 2000-2001 to 2019-2020 Canadian Community Health Survey (share files). |

||||||

Figure 2.9 - Text description

| Time period | Both Sexes | |

|---|---|---|

| % | 95% |

|

| Aged 18 to 34 years | ||

| 2000-2001 | 15.1 | (14.5, 15.7) |

| 2003 | 15.7 | (15.1, 16.3) |

| 2005 | 15.7 | (15.2, 16.3) |

| 2007-2008 | 16.4 | (15.7, 17.0) |

| 2009-2010 | 17.1 | (16.3, 17.9) |

| 2011-2012 | 16.7 | (15.9, 17.5) |

| 2013-2014 | 18.8 | (18.0, 19.7) |

| 2015-2016 | 18.3 | (17.5, 19.2) |

| 2017-2018 | 19.3 | (18.4, 20.1) |

| 2019-2020 | 20.8 | (19.7, 21.9) |

| Aged 35 to 49 years | ||

| 2000-2001 | 21.6 | (20.9, 22.2) |

| 2003 | 21.3 | (20.6, 22.0) |

| 2005 | 22.7 | (22.0, 23.5) |

| 2007-2008 | 24.0 | (23.2, 24.8) |

| 2009-2010 | 24.6 | (23.7, 25.5) |

| 2011-2012 | 27.4 | (26.4, 28.4) |

| 2013-2014 | 27.9 | (26.7, 29.0) |

| 2015-2016 | 29.7 | (28.6, 30.8) |

| 2017-2018 | 29.8 | (28.7, 30.9) |

| 2019-2020 | 31.0 | (29.8, 32.2) |

| Aged 50 to 64 years | ||

| 2000-2001 | 26.6 | (25.7, 27.4) |

| 2003 | 27.7 | (26.9, 28.6) |

| 2005 | 27.9 | (27.0, 28.7) |

| 2007-2008 | 29.2 | (28.3, 30.0) |

| 2009-2010 | 29.5 | (28.4, 30.5) |

| 2011-2012 | 30.4 | (29.4, 31.5) |

| 2013-2014 | 31.3 | (30.4, 32.3) |

| 2015-2016 | 31.4 | (30.4, 32.3) |

| 2017-2018 | 31.6 | (30.6, 32.6) |

| 2019-2020 | 33.2 | (32.2, 34.3) |

| Aged 65 to 79 years | ||

| 2000-2001 | 22.5 | (21.6, 23.5) |

| 2003 | 23.5 | (22.6, 24.5) |

| 2005 | 24.6 | (23.7, 25.4) |

| 2007-2008 | 26.8 | (25.8, 27.8) |

| 2009-2010 | 27.3 | (26.4, 28.2) |

| 2011-2012 | 27.7 | (26.7, 28.7) |

| 2013-2014 | 29.0 | (28.1, 30.0) |

| 2015-2016 | 29.3 | (28.3, 30.4) |

| 2017-2018 | 29.9 | (28.9, 30.8) |

| 2019-2020 | 30.4 | (29.5, 31.3) |

| Aged 80 years or older | ||

| 2000-2001 | 14.9 | (13.3, 16.4) |

| 2003 | 13.8 | (12.6, 15.1) |

| 2005 | 15.6 | (14.1, 17.1) |

| 2007-2008 | 17.1 | (15.6, 18.5) |

| 2009-2010 | 17.1 | (15.7, 18.6) |

| 2011-2012 | 16.3 | (14.9, 17.7) |

| 2013-2014 | 18.8 | (17.3, 20.3) |

| 2015-2016 | 17.6 | (16.2, 19.0) |

| 2017-2018 | 20.0 | (18.4, 21.5) |

| 2019-2020 | 20.2 | (18.6, 21.8) |

Data sources: 2000-2001 to 2019-2020 Canadian Community Health Survey (share files). |

||

Figure 2.10 - Text description

| Time period | Both Sexes | |

|---|---|---|

| % | 95% |

|

| Household income quintile 1 | ||

| 2000-2001 | 21.7 | (20.9, 22.6) |

| 2003 | 22.2 | (21.3, 23.2) |

| 2005 | 21.7 | (20.9, 22.5) |

| 2007-2008 | 23.6 | (22.5, 24.6) |

| 2009-2010 | 23.5 | (22.5, 24.6) |

| 2011-2012 | 23.7 | (22.7, 24.7) |

| 2013-2014 | 25.5 | (24.4, 26.7) |

| 2015-2016 | 26.7 | (25.6, 27.9) |

| 2017-2018 | 27.3 | (26.3, 28.4) |

| 2019-2020 | 28.3 | (27.0, 29.5) |

| Household income quintile 2 | ||

| 2000-2001 | 22.1 | (21.3, 23.0) |

| 2003 | 22.8 | (21.8, 23.8) |

| 2005 | 21.8 | (20.9, 22.6) |

| 2007-2008 | 22.9 | (22.0, 23.8) |

| 2009-2010 | 23.4 | (22.3, 24.4) |

| 2011-2012 | 24.1 | (23.0, 25.2) |

| 2013-2014 | 26.3 | (25.2, 27.4) |

| 2015-2016 | 26.3 | (25.2, 27.4) |

| 2017-2018 | 27.3 | (26.2, 28.4) |

| 2019-2020 | 28.1 | (26.8, 29.5) |

| Household income quintile 3 | ||

| 2000-2001 | 20.7 | (19.8, 21.6) |

| 2003 | 22.0 | (21.1, 22.9) |

| 2005 | 22.8 | (21.9, 23.6) |

| 2007-2008 | 23.4 | (22.5, 24.2) |

| 2009-2010 | 24.2 | (23.2, 25.3) |

| 2011-2012 | 25.2 | (24.1, 26.3) |

| 2013-2014 | 26.9 | (25.8, 28.0) |

| 2015-2016 | 26.1 | (25.0, 27.2) |

| 2017-2018 | 28.0 | (26.9, 29.1) |

| 2019-2020 | 28.1 | (26.8, 29.4) |

| Household income quintile 4 | ||

| 2000-2001 | 20.5 | (19.7, 21.4) |

| 2003 | 20.4 | (19.5, 21.2) |

| 2005 | 22.3 | (21.4, 23.3) |

| 2007-2008 | 23.4 | (22.5, 24.3) |

| 2009-2010 | 23.6 | (22.7, 24.6) |

| 2011-2012 | 25.0 | (23.9, 26.1) |

| 2013-2014 | 26.1 | (25.1, 27.2) |

| 2015-2016 | 26.9 | (25.9, 28.0) |

| 2017-2018 | 26.9 | (25.9, 27.9) |

| 2019-2020 | 28.8 | (27.5, 30.0) |

| Household income quintile 5 | ||

| 2000-2001 | 19.8 | (19.0, 20.6) |

| 2003 | 20.4 | (19.5, 21.2) |

| 2005 | 20.9 | (20.1, 21.7) |

| 2007-2008 | 22.9 | (22.0, 23.7) |

| 2009-2010 | 24.3 | (23.3, 25.4) |

| 2011-2012 | 25.8 | (24.7, 26.9) |

| 2013-2014 | 25.8 | (24.8, 26.8) |

| 2015-2016 | 26.1 | (25.1, 27.1) |

| 2017-2018 | 25.1 | (24.1, 26.1) |

| 2019-2020 | 27.7 | (26.5, 28.9) |

Data sources: 2000-2001 to 2019-2020 Canadian Community Health Survey (share files). |

||

Figure 2.11 - Text description

| Time period | Both Sexes | |

|---|---|---|

| % | 95% |

|

| Less than secondary school graduation | ||

| 2000-2001 | 26.0 | (25.1, 26.9) |

| 2003 | 27.9 | (26.7, 29.0) |

| 2005 | 28.7 | (27.6, 29.8) |

| 2007-2008 | 29.3 | (27.9, 30.6) |

| 2009-2010 | 29.5 | (28.1, 30.9) |

| 2011-2012 | 31.7 | (30.0, 33.4) |

| 2013-2014 | 31.0 | (29.5, 32.6) |

| 2015-2016 | 32.8 | (31.3, 34.4) |

| 2017-2018 | 33.3 | (31.6, 34.9) |

| 2019-2020 | 33.6 | (31.7, 35.5) |

| Secondary school graduation | ||

| 2000-2001 | 21.3 | (20.5, 22.0) |

| 2003 | 23.3 | (22.4, 24.2) |

| 2005 | 25.2 | (24.3, 26.1) |

| 2007-2008 | 25.5 | (24.5, 26.5) |

| 2009-2010 | 26.5 | (25.3, 27.8) |

| 2011-2012 | 28.0 | (26.7, 29.3) |

| 2013-2014 | 30.2 | (29.0, 31.4) |

| 2015-2016 | 30.8 | (29.6, 32.0) |

| 2017-2018 | 30.3 | (29.1, 31.5) |

| 2019-2020 | 32.3 | (30.9, 33.7) |

| Post-secondary certificate, diploma or university degree | ||

| 2000-2001 | 19.4 | (18.9, 19.8) |

| 2003 | 19.8 | (19.3, 20.2) |

| 2005 | 20.7 | (20.2, 21.2) |

| 2007-2008 | 22.4 | (21.9, 22.8) |

| 2009-2010 | 22.8 | (22.2, 23.3) |

| 2011-2012 | 24.0 | (23.4, 24.6) |

| 2013-2014 | 24.9 | (24.3, 25.5) |

| 2015-2016 | 25.2 | (24.6, 25.7) |

| 2017-2018 | 25.8 | (25.2, 26.4) |

| 2019-2020 | 27.3 | (26.6, 27.9) |

Data sources: 2000-2001 to 2019-2020 Canadian Community Health Survey (share files). |

||

Figure 2.12 - Text description

| Time period | Both Sexes | Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% |

% | 95% |

% | 95% |

|

| Adults aged 18 years or older | ||||||

| 2000-2001 | 1.6 | (1.5, 1.7) | 1.3 | (1.1, 1.4) | 2.0 | (1.8, 2.1) |

| 2003 | 1.8 | (1.7, 1.9) | 1.6 | (1.4, 1.8) | 2.0 | (1.9, 2.2) |

| 2005 | 1.9 | (1.8, 2.1) | 1.5 | (1.4, 1.7) | 2.4 | (2.2, 2.5) |

| 2007-2008 | 2.3 | (2.2, 2.4) | 1.8 | (1.6, 2.0) | 2.8 | (2.6, 3.0) |

| 2009-2010 | 2.4 | (2.2, 2.5) | 2.0 | (1.8, 2.2) | 2.8 | (2.6, 3.0) |

| 2011-2012 | 2.5 | (2.4, 2.7) | 2.0 | (1.8, 2.2) | 3.1 | (2.8, 3.3) |

| 2013-2014 | 2.8 | (2.6, 3.0) | 2.3 | (2.1, 2.6) | 3.3 | (3.0, 3.5) |

| 2015-2016 | 2.9 | (2.7, 3.0) | 2.4 | (2.2, 2.6) | 3.4 | (3.1, 3.6) |

| 2017-2018 | 3.2 | (3.0, 3.4) | 2.6 | (2.4, 2.9) | 3.8 | (3.6, 4.1) |

| 2019-2020 | 3.5 | (3.2, 3.7) | 2.9 | (2.6, 3.2) | 4.0 | (3.6, 4.3) |

Data sources: 2000-2001 to 2019-2020 Canadian Community Health Survey (share files). |

||||||

Furthermore, the percentage of adults categorised in obesity class III doubled over this period, (see Figure 2.12, for additional information, see Table A2.12a in Appendix C) rising from 1.3% (in 2000-2001) to 2.9% (in 2019-2020) for men, and from 2.0% to 4.0% for women. Age standardized prevalence estimates of obesity and obesity class III were similar to crude rates (see Tables A2.8b and A2.12b in Appendix C).

Based on physical measurements

Trends in obesity based on physical measurements come from the following surveys: the CCHS—Nutrition (2004 and 2015); the CHMS; and the 2005 and 2008 CCHS (see Section 4 Data sources and methods).

Among men aged 18 to 79 years, the prevalence of measured obesity varied depending on the data source: 23.1% in the 2004-CCHS-Nutrition, 28.8% in the 2015-CCHS-Nutrition and 27.3% in the combined 2014-2019-CHMS (see Figure 2.13). Among women, estimates were not statistically different. For additional details, see Table A2.13a in Appendix C.

Figure 2.13 - Text description

| Time period | Both Sexes | Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% |

% | 95% |

% | 95% |

|

| Adults aged 18 to 79 years | ||||||

| 2004 | 23.2 | (21.7, 24.7) | 23.1 | (20.8, 25.4) | 23.3 | (21.3, 25.3) |

| 2005 | 24.6 | (22.3, 27.0) | 25.9 | (22.7, 29.2) | 23.3 | (20.4, 26.2) |

| 2008 | 25.3 | (23.4, 27.2) | 26.4 | (23.7, 29.1) | 24.2 | (21.5, 26.8) |

| 2007-2009/ 2009-2011/ 2012-2013 | 25.6 | (23.3, 27.8) | 26.0 | (23.5, 28.6) | 25.1 | (22.2, 28.0) |

| 2015 | 27.0 Footnote a | (25.2, 28.8) | 28.8 Footnote a | (26.1, 31.4) | 25.2 | (22.9, 27.5) |

| 2014-2015/ 2016-2017/ 2018-2019 | 26.5 Footnote a | (23.6, 29.3) | 27.3 Footnote a | (24.2, 30.5) | 25.5 | (22.3, 28.8) |

Data sources: 2004 and 2015 Canadian Community Health Survey—Nutrition (share files); 2005 and 2008 Canadian Community Health Survey (share files); 2007-2009/2009-2011/2012-2013/2014-2015/2016-2017/2018-2019 Canadian Health Measures Survey (Cycles 1 to 6). Footnotes

|

||||||

For obesity class III, the combined 2014-2019 CHMS estimate for men (3.2%) is not significantly different from the estimates from the 2015 CCHS‒Nutrition (2.0%), and marginally different from the 2008 CCHS (1.3%) (see Figure 2.14). Among women, the prevalence of obesity class III were similar across the different time periods from 2004 to 2019. For additional details, see Table A2.14a in Appendix C.

Age standardized prevalence estimates of obesity and obesity class III were similar to crude rates when examined (see Tables A2.13b and A2.14b in Appendix C).

Figure 2.14 - Text description

| Time period | Both Sexes | Males | Females | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% |

% | 95% |

% | 95% |

|

| Adults aged 18 to 79 years | ||||||

| 2004 | 2.8 | (2.2, 3.3) | 1.6 Footnote E | (1.1, 2.2) | 3.9 | (3.0, 4.8) |

| 2005 | 2.2 Footnote E | (1.5, 2.9) | 1.2 Footnote E | (0.5, 1.9) | 3.1 Footnote E | (1.9, 4.3) |

| 2008 | 2.3 | (1.7, 2.8) | 1.3 Footnote E | (0.8, 1.8) | 3.2 | (2.2, 4.2) |

| 2007-2009/ 2009-2011/ 2012-2013 | 3.4 Footnote aFootnote b | (2.8, 4.0) | 2.1 | (1.5, 2.6) | 4.8 | (3.5, 6.0) |

| 2015 | 2.9 | (2.4, 3.4) | 2.0 | (1.4, 2.6) | 3.9 | (3.0, 4.7) |

| 2014-2015/ 2016-2017/ 2018-2019 | 4.0 Footnote aFootnote cFootnote d | (3.0, 4.9) | 3.2 Footnote EFootnote cFootnote d | (1.8, 4.6) | 4.8 Footnote c | (3.8, 5.8) |

Data sources: 2004 and 2015 Canadian Community Health Survey—Nutrition (share files); 2005 and 2008 Canadian Community Health Survey (share files); 2007-2009/2009-2011/2012-2013/2014-2015/2016-2017/2018-2019 Canadian Health Measures Survey (Cycles 1 to 6). Footnotes

|

||||||

Projections

Forecasting the trajectory of the prevalence of obesity can help in planning and evaluating public health strategies. Statistics Canada's microsimulation Population Health Model (POHEM) uses multiple data sources to simulate the health status of the population over time, by combining the results of individual life course simulations for a large sample Footnote 66. See Section 4 - Data sources and methods for more information regarding POHEM. The model was created to predict the prevalence of obesity, in a way that accounts for interconnected factors such as socio-demographics and health behaviours (smoking, physical activity levels, chronic diseases) that may be associated with body weight Footnote 67. POHEM simulated the annual prevalence of obesity among adults aged 18 to 79 years, by sex, over two periods: 2001-to-2018, which was retrospectively compared with observed estimates, and 2018-to-2035, which was used to project future patterns (see Figure 2.15).

Figure 2.15 - Text description

Year |

Total Predicted % (POHEM) | Total Adjusted Self-Reported % (CCHS) | 95% Confidence Interval (CCHS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 22.69 | ||

| 2002 | 22.74 | ||

| 2003 | 23.16 | ||

| 2004 | 23.64 | ||

| 2005 | 24.26 | ||

| 2006 | 24.55 | ||

| 2007 | 25.08 | ||

| 2008 | 25.44 | 23.7 | (23.2, 24.3) |

| 2009 | 25.81 | 24.0 | (23.4, 24.6) |

| 2010 | 26.14 | 24.2 | (23.5, 24.8) |

| 2011 | 26.60 | 24.9 | (24.2, 25.6) |

| 2012 | 26.89 | 25.3 | (24.6, 26.0) |

| 2013 | 27.15 | 25.9 | (25.2, 26.6) |

| 2014 | 27.44 | 27.0 | (26.2, 27.7) |

| 2015 | 27.88 | 26.5 | (25.8, 27.2) |

| 2016 | 28.22 | 27.0 | (26.3, 27.7) |

| 2017 | 28.47 | 27.2 | (26.5, 27.9) |

| 2018 | 28.69 | 27.2 | (26.5, 27.9) |

| 2019 | 28.97 | ||

| 2020 | 29.26 | ||

| 2021 | 29.59 | ||

| 2022 | 30.07 | ||

| 2023 | 30.42 | ||

| 2024 | 30.56 | ||

| 2025 | 30.91 | ||

| 2026 | 31.20 | ||

| 2027 | 31.46 | ||

| 2028 | 31.67 | ||

| 2029 | 31.83 | ||

| 2030 | 32.05 | ||

| 2031 | 32.22 | ||

| 2032 | 32.46 | ||

| 2033 | 32.48 | ||

| 2034 | 32.53 | ||

| 2035 | 32.69 | ||

Data sources: POHEM projections for 2001 through 2035; 2008 to 2018 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) (share files). |

|||

Note: POHEM projections for BMI account for age, physical activity, and smoking. The model does not account for diet quality or potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

POHEM results showed that during the 2001-to-2018 period, the prevalence of obesity in the total adult population rose from 22.7% to 28.7%, an average annual rate of 1.5%. These simulated numbers aligned relatively well with those derived from survey data (see Table A2.8a).

The predicted 2018-to-2035 time-series shows further increases in the prevalence of obesity among adults, but at a much slower annual pace: 0.8% rather than 1.5%. POHEM predictions do not account for all factors associated with BMI, diet being a notable exclusion Footnote 68, or consider the potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. These are important limitations of the model given both the significant influence of diet on body weight and signals that the pandemic may have had lasting effects on behaviours and other factors related to body weight.

Obesity and the COVID-19 pandemic

On March 11th, 2020, COVID-19 was declared a pandemic. Initially, not a lot was known on this virus, but over the past few years, research has helped paint a picture of the association between COVID-19 and obesity.

Foremost, research has demonstrated that obesity is associated with increased severity of COVID-19 Footnote 69Footnote 70Footnote 71Footnote 72. For those living with obesity, the risk of COVID-19 infection and the severity of symptoms are increased Footnote 70. Obesity has been linked to impaired immune function and to a decrease in lung capacity and reserve, which result in difficulties breathing and the increased burden of COVID-19 observed among those living with obesity Footnote 71Footnote 72. One review differentiated between overweight and obesity: the first increases the risk of COVID-19-related hospitalisations, but not death; while the second would appear to increase the risk of both COVID-19-related hospitalisations and death Footnote 71. However, whether obesity significantly increases mortality remains a debate across studies Footnote 73.