Social media use, connections, and relationships in Canadian adolescents

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 1.9 MB, 14 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Type: Publication

Date published: 2022-01-04

Related topics

Findings from the 2018 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Study.

On this page

- Introduction

- The importance of connections

- Perceptions of high social support in adolescent relationships

- Prevalence of intensive and problematic social media use

- Intensive social media use and connections and relationships

- Problematic social media use and connections and relationships

- Limitations

- Conclusions

- Methods

- References

- Acknowledgements

Introduction

Strong connections and relationships are known to be protective to health for young people as they grow and develop through their adolescent years (Freeman et al., 2016; Michaelson et al., 2016).

The availability of computers, tablets, smartphones and other electronic devices provides opportunities for young people to be connected at unprecedented levels. Many young people report being online with friends, family and others almost constantly (Craig et al., 2020). Some young people's online behaviours have had such an effect on their lives that they have been labelled as "problematic" (Boer et al., 2020).

The influence of social media use on health was highlighted as a priority in the most recent national HBSC Report (PHAC, 2020). Yet, despite growing awareness of the role that social media use plays in the lives of young people, there are little population data on its impacts on the lives of young Canadians. This is particularly true with respect to the influence of social media behaviours on connections and relationships.

This report describes the importance of connections and relationships in the lives of Canadian adolescents, and the correlations of these connections and relationships with intensive and problematic social media use using the 2018 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study.

The importance of connections

Connections play an important role in the lives of young people (Michaelson et al., 2016). These connections were measured in the 2018 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study using a short scale where adolescents rated the importance of connections within themselves (self), to other people (others), to nature and the land (nature), or to something greater (the transcendent) (Michaelson et al., 2016).

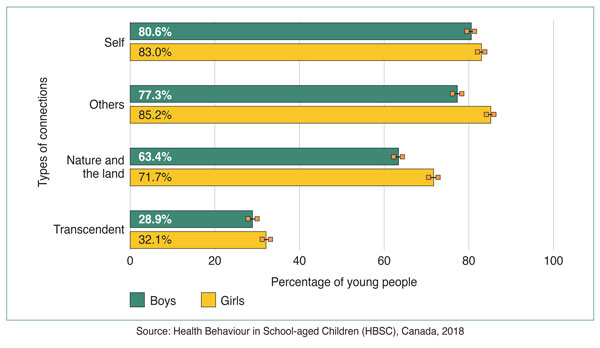

Girls are more likely than boys to report that connections are important to their lives. To illustrate, 83.0% of girls and 80.6% of boys rated connections to self as important, and 85.2% of girls and 77.3% of boys rated connections to others as important. Connections to nature were rated as important by 71.7% of girls and 63.4% of boys. Connections to the transcendent were rated as important by the lowest proportions of boys (28.9%) and girls (32.1%).

Figure 1: Text equivalent

| Types of connections | Boys | Girls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of young people | (95% CI) | % of young people | (95% CI) | |

| Self | 80.6% | (79.7 to 81.5) | 83.0% | (82.2 to 83.8) |

| Others | 77.3% | (76.4 to 78.3) | 85.2% | (84.5 to 86.0) |

| Nature and the land | 63.4% | (62.3 to 64.5) | 71.7% | (70.8 to 72.6) |

| Transcendent | 28.9% | (27.8 to 29.9) | 32.1% | (31.1 to 33.1) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 |

||||

Perceptions of high social support in adolescent relationships

Strong relationships within families, schools and peer groups are known to be beneficial to adolescent health (Freeman et al., 2016). Yet, less than half of young Canadians reported high levels of social support in such contexts. For example, 36.6% of boys and 33.9% of girls reported high levels of family support, and 22.9% of boys and 35.2% of girls reported high levels of support from friends.

Figure 2: Text equivalent

| Types of social supports | Boys | Girls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of young people | (95% CI) | % of young people | (95% CI) | |

| Family | 36.6% | (35.6 to 37.7) | 33.9% | (33.0 to 34.9) |

| Teachers | 35.3% | (34.2 to 36.4) | 35.0% | (34.0 to 36.0) |

| Classmates | 49.9% | (48.8 to 51.0) | 40.5% | (39.5 to 41.5) |

| Friends | 22.9% | (22.0 to 23.9) | 35.2% | (34.2 to 36.2) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 |

||||

Prevalence of intensive and problematic social media use

The frequency of social media use reported by young people is used to identify intensive use (online contact "almost all the time throughout the day").

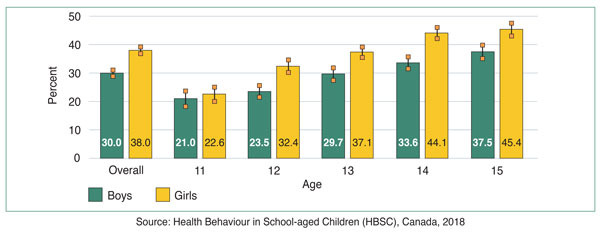

Overall, for students aged 11 to 15, more girls (38.0%) than boys (30.0%) reported intensive social media use. Reports of intensive social media use increased with age among both boys and girls.

Figure 3: Text equivalent

| Age | Boys | Girls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | (95% CI) | Percent | (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 30.0% | (29.0 to 31.0) | 38.0% | (37.0 to 39.0) |

| 11 | 21.0% | (18.2 to 23.7) | 22.6% | (20.0 to 25.1) |

| 12 | 23.5% | (21.4 to 25.5) | 32.4% | (30.3 to 34.6) |

| 13 | 29.7% | (27.5 to 31.8) | 37.1% | (35.1 to 39.2) |

| 14 | 33.6% | (31.5 to 35.7) | 44.1% | (42.1 to 46.1) |

| 15 | 37.5% | (35.2 to 39.9) | 45.4% | (43.2 to 47.6) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 |

||||

Problematic social media use is defined using a scale consisting of nine items. This scale is designed to measure whether the respondent shows addiction-like social media use.

Problematic social media use is significantly higher among older girls (ages 13 to 15 years) compared to younger girls (ages 11 to 12 years), but problematic social media use did not differ by age among boys.

Figure 4: Text equivalent

| Age | Boys | Girls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | (95% CI) | Percent | (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 5.2% | (4.7 to 5.7) | 7.7% | (7.1 to 8.2) |

| 11 | 5.1% | (3.6 to 6.7) | 4.1% | (2.8 to 5.4) |

| 12 | 4.1% | (3.1 to 5.1) | 4.7% | (3.7 to 5.7) |

| 13 | 4.7% | (3.7 to 5.7) | 8.5% | (7.3 to 9.8) |

| 14 | 6.6% | (5.5 to 7.8) | 8.5% | (7.4 to 9.7) |

| 15 | 5.1% | (4.0 to 6.2) | 10.3% | (8.9 to 11.6) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 |

||||

Intensive social media use and connections and relationships

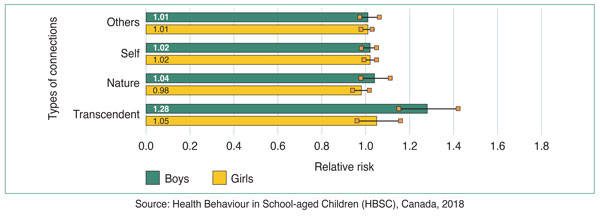

Associations between intensive social media use and the strengths of connections and relationships among adolescent Canadians were examined using regression models.

Associations between intensive social media use and the connections and relationships measures were not strong and most often not statistically significant. One exception to this was for the indicator of high friend support. Intensive social media use was associated with higher levels of support from friends, among both boys (Relative Risk 1.55) and girls (Relative Risk 1.40).

Figure 5: Text equivalent

| Types of connections | Boys | Girls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk | Relative risk | |||

| % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | |

| Others | 1.01% | (0.97 to 1.06) | 1.01% | (0.98 to 1.03) |

| Self | 1.02% | (0.98 to 1.05) | 1.02% | (0.99 to 1.05) |

| Nature | 1.04% | (0.98 to 1.11) | 0.98% | (0.94 to 1.02) |

| Transcendent | 1.28% | (1.15 to 1.42) | 1.05% | (0.96 to 1.16) |

Figure 6: Text equivalent

| Types of social supports | Boys | Girls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk | Relative risk | |||

| % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | |

| Family | 1.12% | (1.01 to 1.23) | 1.07% | (0.97 to 1.18) |

| Teacher | 0.98% | (0.87 to 1.11) | 1.09% | (0.99 to 1.20) |

| Classmate | 1.06% | (0.99 to 1.15) | 1.11% | (1.02 to 1.20) |

| Friend | 1.55% | (0.36 to 1.78) | 1.40% | (1.28 to 1.54) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 |

||||

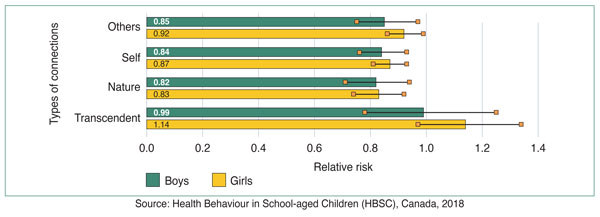

Problematic social media use and connections and relationships

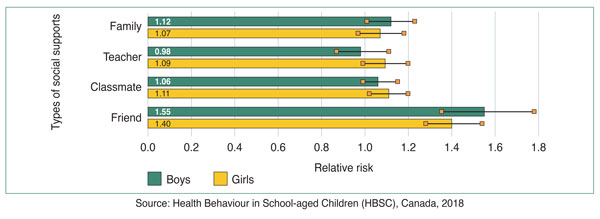

Associations between problematic social media use and young people's connections and relationships were more consistent compared to intensive social media use.

For almost all outcomes, problematic social media use was associated with weaker relationships and connections.

Figure 7: Text equivalent

| Types of connections | Boys | Girls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk | Relative risk | |||

| % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | |

| Others | 0.85% | (0.75 to 0.97) | 0.92% | (0.86 to 0.99) |

| Self | 0.84% | (0.76 to 0.93) | 0.87% | (0.81 to 0.93) |

| Nature | 0.82% | (0.71 to 0.94) | 0.83% | (0.74 to 0.92) |

| Transcendent | 0.99% | (0.78 to 1.25) | 1.14% | (0.97 to 1.34) |

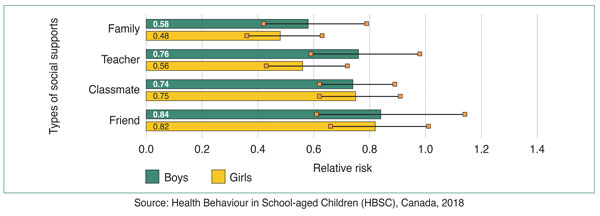

Boys (Relative Risk 0.58) and girls (Relative Risk 0.48) who engaged in problematic social media use were much less likely to report high levels of family support.

Figure 8: Text equivalent

| Types of social supports | Boys | Girls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk | Relative risk | |||

| % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | |

| Family | 0.58% | (0.42 to 0.79) | 0.48% | (0.36 to 0.63) |

| Teacher | 0.76% | (0.59 to 0.98) | 0.56% | (0.43 to 0.72) |

| Classmate | 0.74% | (0.62 to 0.89) | 0.75% | (0.62 to 0.91) |

| Friend | 0.84% | (0.61 to 1.14) | 0.82% | (0.66 to 1.01) |

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 |

||||

Limitations

All research studies have limitations and it is important to interpret results in light of their limitations.

- All data in the HBSC were collected using self-report, which is prone to reporting biases (Choi & Pak, 2005). This could have led to underestimating the prevalence of intensive and problematic social media use and the rated strengths of the relationships and connections that were studied due to social desirability biases.

- The cross-sectional design of the HBSC does not allow for the inference of causality. For example, it is possible that problematic social media use led to poorer relationships and connections. It is also possible that poorer relationships and connections led to problematic social media use or something else may have led to both.

- Students were asked to respond to the question "Are you male or female?" by selecting from the three responses, "male", "female" or "neither term describes me". Students who indicated "neither term describes me" did not comprise a large enough group to include in the statistical analyses.

Conclusions

- Connections and relationships are important indicators to the health of adolescent Canadians (Michaelson et al., 2016).

- Girls are more likely than boys to rate the connections in their lives as important and report higher levels of support from friends.

- Intensive social media use is reported by about 3 in 10 boys, and 4 in 10 girls.

- Problematic social media use is less prevalent, with the highest levels (1 in 10) reported by older girls.

- In general, intensive social media use is not strongly associated with the qualities of the connections and relationships reported by young people. However, it is associated with higher perceived levels of support from friends.

- Problematic social media use is generally associated with weaker connections and relationships among both boys and girls.

Methods

Sample

Data were from the Canadian Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study, a national cross-sectional study of adolescents conducted every four years since 1989-90 [PHAC, 2020]. In 2018, data were collected in school settings from a nationally representative random "two-stage cluster sample" of adolescents in grades 6 to 10 from all provinces and two territories in Canada. For this study, we included the 17,085 participants between the ages of 11 to 15 who responded to items describing intensive and problematic social media use, the importance of social connections, and the strength of relationships.*

*Refer to the international HBSC webpage for more information on the HBSC study.

Social media use

Students were classified as intensive users of social media based on their frequency of communication with four groups: close friend(s); friends from a larger friend group; friends that you got to know through the internet, but didn't know before; and people other than friends (Inchley et al., 2018).

Students were classified as problematic users of social media based on negative aspects of their social media use such as neglecting other activities, being unable to focus on other things, feeling bad about social media use, and having conflict, arguments, or lying to family or friends about social media use (Inchley et al., 2018).

Connections

Using 10 Likert-like indicators that rated their importance (1 - "not at all important" to 5 "very important"), young people described the connections in their lives within four domains. These domains included their connections to others (3 items; how important it is for you to: "be kind to other people", "be forgiving of others", and "show respect to other people"); then to self (2 items; how important it is for you to: "feel that your life has meaning or purpose", "experience joy in life"); then to nature (2 items; the importance of "being connected to nature or wilderness", "care for the natural world"); then to the transcendent (3 items; how important it is to "meditate or pray", "feel a connection to a higher spiritual power", "feel a sense of belonging to something greater than yourself"). Scores within each of the four domains were averaged, with a score of 4 or greater indicating that connections within the domain were rated as "important".

Relationships

The strength of supports available from four social contexts (families, teachers, classmates, and friends) were described using available validated scales [PHAC, 2020]. Each of the four scales is constructed from a set of Likert-type items, family support (4 items, e.g., "I can talk about my problems with my family"), teacher support (8 items, e.g., "I feel that my teachers care about me as a person."), classmate support (3 items, e.g., "The students in my class(es) enjoy being together."), and friend support (4 items, e.g., "I can count on my friends when things go wrong."). The raw scales were collapsed into tertiles with the "high" group representing the one-third of respondents with the most positive responses.

Analysis

Percentages of boys and girls reporting that each of the four domains describing connections were important (an average score of 4 of more for relevant items) were estimated along with 95% confidence intervals. Similar percentages and confidence intervals were estimated for boys and girls describing high levels of support available from their families, teachers, classmates and friends. Percentages of students reporting intensive use of social media, the problematic use of social media, were described by gender and age. In order to be consistent with established precedent in published scientific literature (Boer et al., 2020), this analysis focuses on social media use patterns reported by age and gender, as opposed to school grade and gender. Therefore, some of the results in this report differ slightly from the results in the national HBSC report (PHAC, 2020).

Multivariable binomial regressions were used to model the effects of intensive social media use, then problematic social media use, on the 8 outcomes describing the importance of connections and the strength of social relationships. These models employed the survey weights. The models also adjusted for additional factors (age, family affluence as a measure of socio-economic status, family structure) that potentially confounded the associations under study. Additionally, models examining the effects of intensive social media use are adjusted for problematic social media use and vice versa. Findings are presented as relative risks (RR) and 95% CI's, adjusted for clustering, and were conducted in SAS (Version 9.4).

References

Boer, M., van den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., Boniel-Nissim, M., Wong, S.-L., Inchley, J. C., Badura, P., Craig, W. M., Gobina, I., Kleszczewska, D., Klanšček, H. J., & Stevens, G. W. J. M. (2020). Adolescents' Intense and Problematic Social Media Use and Their Well-Being in 29 Countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6, Supplement), S89-S99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.014

Choi, B. C. K., & Pak, A. W. P. (2005). A catalog of biases in questionnaires. Preventing Chronic Disease, 2, A13.

Craig, W., Boniel-Nissim, M., King, N., Walsh, S.D., Boer, M., Donnelly, P.D., Harel-Fisch, Y., Malinowska-Cieslik, M., Gaspar de Matos, M., Cosma, A., Vandeneijnden, R., Vieno, A., Elgar, F., Molcho, M., Bjereld, Y, Pickett,W. (2020) Social media use and cyber-bullying: a cross-national analysis of young people in 42 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health. Jun;66(6S):S100-S108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.03.006.

Freeman, J., King, M., Pickett, W. (2016). Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children in Canada: Focus on Relationships. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada, 194p; 2015 (ISBN 978-0-660-03890-2; Cat no: HP35-65/2106E, Publication Number: 150150).

Inchley, J., Currie, D., Cosma, A. & Samdal, O. (2018). Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Study Protocol: background, methodology and mandatory items for the 2017/18 survey. St Andrews: CAHRU.

Michaelson, V., Brooks, F., Jirásek, I., Inchley, J., Whitehead, R., King, N., Walsh, S., Davison, C., Mazur, J., Pickett, W., for the HBSC Child Spiritual Health Writing Group. (2016). Developmental patterns of adolescent spiritual health in six countries. SSM-population health, 2, 294-303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.03.006

Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC]. (2020). The health of Canadian youth: Findings from the health behaviour in school-aged children study. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/science-research-data/youth-findings-health-behaviour-school-aged-children-study.html

Acknowledgements

- Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) is an international study carried out in collaboration with the World Health Organization, European Region (WHO/EURO). The International HBSC Coordinator was Dr. Joanna Inchley (University of Glasgow, Scotland) for the 2017/18 survey and the Data Bank Manager was Dr. Oddrun Samdal (University of Bergen, Norway). The Canadian 2017/18 HBSC survey was funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada, the principal investigators were Drs. (the late) John Freeman, William Pickett and Wendy Craig (Queen's University), and the national coordinator was Matthew King (Social Program Evaluation Group, Queen's University).