The health of Canadian youth: Findings from the health behaviour in school-aged children study

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 5.5 MB, 157 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Type: Publication

Date published: 2020-06-24

Related topics

The results of a cross-national research study on the health and health behaviours of youth in Canada in grades 6 through 10.

Table of contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Home and family

- Chapter 3: Friends

- Chapter 4: School

- Chapter 5: Community

- Chapter 6: Physical activity, screen time, and sleep

- Chapter 7: Healthy eating

- Chapter 8: Healthy weights

- Chapter 9: Injury and concussions

- Chapter 10: Bullying and teen dating violence

- Chapter 11: Mental health

- Chapter 12: Spiritual health

- Chapter 13: Substance use

- Chapter 14: Sexual health

- Chapter 15: Social media use

- Chapter 16: Key messages

Foreword

We are pleased to present The health of Canadian youth: Findings from the health behaviour in school-aged children study.

In an evolving public health landscape, gaining insight into the health and well-being of young people remains important. Understanding the connections between health and social contexts is a crucial step in ensuring positive health outcomes. This report examines the social determinants of youth health, including family, friends, school and community. We are encouraged to see that the majority of youth are reporting happy home lives and positive relationships with their parents.

Further, the study’s ability to capture trends in health behaviour provides information on progress made in addressing some risk-taking behaviours, such as smoking, and the challenges that are emerging, such as vaping. In addition, new information collected on social media use has provided us with a more comprehensive perspective on its positive and negative dimensions, and identifies it as an important emerging health issue.

The report highlights the continued need to support young people during an important time of transition. The study is a valuable source of information that enables the Public Health Agency of Canada to deliver on its mandate to protect and promote the health of Canadians through evidence-based decision-making.

We extend our gratitude to the over 21,000 students across Canada who shared their lived experiences, as well as to the young people who were engaged in providing reflections, context and insight on the findings. Youth perspectives matter and are an invaluable contribution to our work. Thank you to the teachers and school administrators for their collaboration and support in the administration of this survey. Together we can help to ensure that young people in Canada receive the support they need to lead healthy lives.

Tina Namiesniowski

President, Public Health Agency of Canada

Dr. Theresa Tam

Chief Public Health Officer of Canada

Acknowledgements

This report presents findings from the 8th cycle of the health behaviour in school-aged children survey in Canada. We would like to acknowledge the collaborative efforts of the 50 participating research teams from Europe and North America and the ongoing support of the International Coordinating Centre in Scotland, as well as the International Databank Coordinating Centre in Norway.

The administration of the HBSC survey and the presentation of findings in this report are made possible by funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada through the Youth Policy and Partnerships Unit in the Division of Children and Youth.

Special appreciation is given to Dr. Suzy Wong, Senior Policy Analyst; Matthew Enticknap, Manager; and Adrian Puga, Manager; as well as reviewers within the Government of Canada for providing invaluable insight and contributions throughout the planning and the completion of this report.

The Pan-Canadian Joint Consortium for School Health (JCSH) collaborated with the HBSC team to provide active support in the data collection phase of the study and to identify priority issues in the development of the survey instruments and for reporting. Leadership in our collaboration was provided by Executive Director Katherine Kelly, the JCSH Secretariat, and the JCSH School Health Coordinators’ Committee.

For the first time the HBSC study has targeted a subsample of students who are the children of current or retired Canadian Armed Forces families. This was done in collaboration with the Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research (CIMVHR) under the leadership of Dr. Alyson Mahar. Findings will be released in a separate report.

We would like to acknowledge Shanti MacFronton, Sharif Mahdy, Christa Romaldi, Gillian Camazzola and Stoney McCart, and their colleagues from The Students Commission of Canada, for their work in bringing together young people to elicit their input on questions, and for their work in collecting and summarizing the views of young people. We would also like to thank the young people who so candidly shared with us their thoughts and experiences and their perspectives on the HBSC findings.

The Social Program Evaluation Group, Queen’s University, was responsible for collecting and analyzing the data under the supervision and organization of Matthew King. Sandy Youmans and Diane Earle were responsible for contacting school jurisdictions and schools and coordinating the administration of the survey.

Data entry, coding, questionnaire handling, and the related tracking and documentation were carried out by Deen Maishan, Nea Okada, Lovleen Cheema, Christina Zheng, Darmetha Ajerla, Nive Indrajith, Vivek Thanki, Jaishnu Moudgil, Najmeh Arabi, Hannah Michaelson, Ozma Aziz, Olivia Hughes, Hossein Tari, Sau-Ling Hum, Sierra Dyer, Natalie Kwan, and Diksha Doodnauth.

Diane Yocum was responsible for carrying out and overseeing the many administrative tasks required in the questionnaire development process and collecting the data, as well as preparing and editing the figures and the text in the report.

Lee Watkins edited the manuscript, while Les Stuart graphically designed the report and assisted the editorial team with picture research. Chantal Caron was responsible for translating the English version of the report into French.

We would like to thank all of the co-investigators who have contributed to the development of the measures, the methodology, as well as the conceptual direction of the report (Dr. Colleen Davison, Dr. Ian Janssen, and Dr. Don Klinger of Queen’s University; Dr. Frank Elgar, McGill University; Dr. Genevieve Gariepy, l’Université de Montréal; Dr. Kathy Georgiades, McMaster University; Dr. Scott Leatherdale, University of Waterloo; Dr. Michael McIsaac, University of Prince Edward Island; and Dr. Elizabeth Saewyc, University of British Columbia).

We are also grateful for the leadership of Dr. John Freeman, who worked tirelessly as the principal investigator of HBSC Canada from 2008 to 2017. On John’s passing in August 2017 the leadership of HBSC Canada and this survey was assumed by Dr. Wendy Craig, Dr. Will Pickett, and Mr. Matthew King, who co-authored this report.

Most importantly, we wish to thank all the students who were willing to share their experiences with us, as well as the school principals, teachers, school boards, and parents, for making this survey happen.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC)

The HBSC examines the health and health behaviours of youth ages 11-15 through a population health theory lens. Such a lens considers both individual and collective factors and conditions within broadly defined determinants of health (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2013). Among youth, these physical and social environmental determinants include their home life, school life, peer groups, neighbourhood settings, socioeconomic status, and health and risk behaviours.

Purpose

The main purposes of the HBSC are to understand youth health and well-being and to inform education and health policy and health promotion programs nationally and internationally. The HBSC is conducted every four years using a common research protocol, which is developed and approved by the International Assembly of Principal Investigators. By collecting common indicators of youth health across multiple nations and administering the survey every four years, health behaviours in youth can be compared internationally, within nations, and over time.

Objectives

In Canada, the HBSC is funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and conducted by Queen’s University. The protocol and associated questions asked of Canadian students are developed through a broad-based consultation model alongside PHAC, provincial and territorial Ministries of Health and Education through the Pan-Canadian Joint Consortium for School Health and the Canadian HBSC team.

The primary objectives of the HBSC are to:

- initiate and sustain national and international research on health behaviour, health and well-being, and their social and physical contexts in school-aged children;

- contribute to theoretical, conceptual, and methodological development in youth health research;

- monitor health and health behaviours and social and physical contexts of school-aged children;

- disseminate findings to the relevant audiences;

- provide an international source of expertise on youth health for public health and health education.

Methods

The Canadian HBSC survey

- The student questionnaire represents the core source of information in the HBSC.

- Questionnaires were administered to school classes during one 45-70 minute session.

- Survey questions covered a wide range of topics pertaining to health and its determinants.

- Researchers were granted ethics clearance for the study by Research Ethics Boards from both Queen’s University and PHAC/Health Canada.

Youth perspective

In 2019, the Students Commission of Canada (SCC) worked with the Public Health Agency of Canada to support youth engagement on the HBSC study through youth-centered events, workshops, activities and youth-generated videos/materials that engage with the HBSC study findings. Young people across Canada have engaged in providing reflections, context and insight to the most recent HBSC findings and they are represented in this report through the youth participant quotes and youth perspective.

Sample

Selection of schools

- All provinces and two territories (Yukon and the Northwest Territories) participated in 2018.

- School jurisdictions in each province or territory were identified and ordered according to key characteristics: language of instruction, public/Roman Catholic designation (where applicable), and community size.

- A list of schools within eligible and consenting school jurisdictions was created, and schools in the sample were selected randomly from this list.

Selection of students

- The number of classes in specific schools was estimated based on the grades in the school, the number of teachers, the total enrolment, and the enrolment by grade, while accounting for known variations in class structure.

- Classes had an approximately equal chance of being selected.

- Students within the selected classrooms, following consent, were asked to complete the survey questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

- Nationally-representative estimates were calculated using survey weights, which reflected actual enrolments of students within each grade (from grades 6 to 10) and province/territory.

- Differences between groups are considered statistically significant (p<.05) if they were three percent or greater.

| Province | Schools | Students | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 20 | (7.0%) | 1,740 | (8.1%) | |

| Alberta | 29 | (10.1%) | 2,261 | (10.5%) | |

| Saskatchewan | 8 | (2.8%) | 373 | (1.7%) | |

| Manitoba | 27 | (9.4%) | 2,569 | (11.9%) | |

| Ontario | 54 | (18.8%) | 2,757 | (12.8%) | |

| Quebec | 25 | (8.7%) | 1,832 | (8.5%) | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 20 | (7.0%) | 1,416 | (6.6%) | |

| Nova Scotia | 21 | (7.3%) | 2,438 | (11.3%) | |

| Prince Edward Island | 14 | (4.9%) | 2,410 | (11.2%) | |

| New Brunswick | 7 | (2.4%) | 584 | (2.7%) | |

| Northwest Territories | 34 | (11.8%) | 1,724 | (8.0%) | |

| Yukon | 28 | (9.8%) | 1,437 | (6.7%) | |

| Total | 287 | (100%) | 21,541 | (100%) | |

| Gender, number, percentage, total | Grade | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| Male | n | 2,017 | 2,143 | 2,114 | 2,294 | 1,688 | 10,256 |

| % | 50.6% | 47.4% | 47.4% | 48.0% | 46.9% | 48.0% | |

| Female | n | 1,932 | 2,315 | 2,264 | 2,414 | 1,842 | 10,767 |

| % | 48.4% | 51.2% | 50.8% | 50.5% | 51.2% | 50.4% | |

| Neither term describes me*Footnote * | n | 39 | 64 | 78 | 76 | 70 | 327 |

| % | 1.0% | 1.4% | 1.8% | 1.6% | 1.9% | 1.5% | |

| Total | n | 3,988 | 4,522 | 4,456 | 4,784 | 3,600 | 21,350 |

|

|||||||

References

Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC]. (2013). What is the population health approach? Retrieved from http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/approach-approche/appr-eng.php

Chapter 2: Home and family

- Family structure

- Happy home life

- Want to leave home

- Mother easy to talk to

- Father easy to talk to

- Parents understand me

- Conclusions

Family

Throughout development, the family is an important socializing force, influencing young people’s actions, values, and beliefs (Parke & Buriel, 2006). As behavioural role models, family plays a key role in a variety of health-promoting behaviours. Parents also play a significant role in supporting young people’s psychological and emotional health and well-being. Youth with strong attachments and supportive relationships with their parents are more likely to have high self-esteem. These positive parental connections may also help adolescents to cope with challenges and struggles (Bulanda & Majumdar, 2009), including mental health problems (Leone, Ray, & Evans, 2013).

Adolescence marks a time of great social and emotional change, where youth begin to expand their networks of social support. Despite the increase in social support from friends and partners during adolescence, parental support continues to be a key factor in healthy mental and physical development.

In this chapter, we examine the relationships that adolescents have with their parents. These relationships are assessed by asking students about how supported they feel by their family; if their parents expect too much of them; if they feel understood by their parents; if they have a happy home life; if they have thoughts of leaving home; and the ease at which they communicate with their mother and father.

Family support

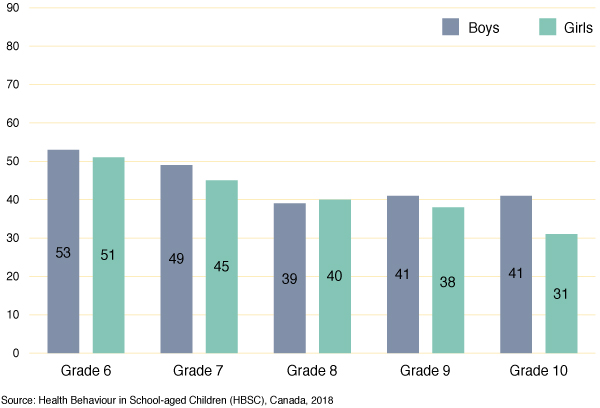

With increasing grade, fewer girls report high family support.

51% of girls in grade 6 report high family support compared to 31% of girls in grade 10.

The percentage of boys who report high family support is higher in grades 6 and 7 than in grades 9 and 10.

53% of boys in grade 6 report high family support compared to 41% of boys in grade 10.

Parents are struggling with being over protective and accepting that kids are growing up. They also struggle with communication and listening. A lot of times parents are on their phones, so they’re struggling to be present.

[Youth Workshop Group Reflections]

Figure 1 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 53 | 51 |

| Grade 7 | 49 | 45 |

| Grade 8 | 39 | 40 |

| Grade 9 | 41 | 38 |

| Grade 10 | 41 | 31 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

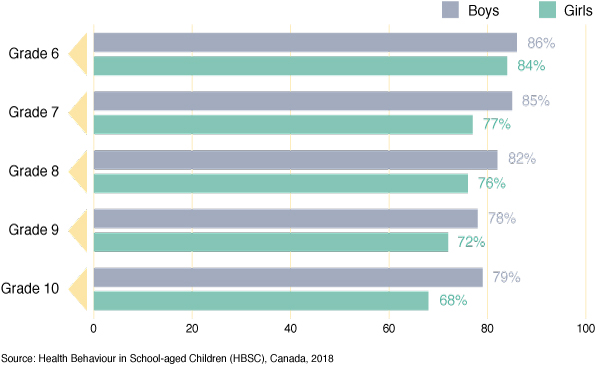

Majority of students report having a happy home life

Boys are more likely than girls to report having a happy home life.

79% of boys in grade 10 report having a happy home life compared to 68% of grade 10 girls.

With increasing grade, there are fewer students who report having a happy home life. This drop is greater for girls than boys.

86% of grade 6 boys report having a happy home life and it drops 7 percentage points to 79% by grade 10.

For girls, 84% report having a happy home life in grade 6 and it drops 16 percentage points to 68% by grade 10.

Figure 2 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 86 | 84 |

| Grade 7 | 85 | 77 |

| Grade 8 | 82 | 76 |

| Grade 9 | 78 | 72 |

| Grade 10 | 79 | 68 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

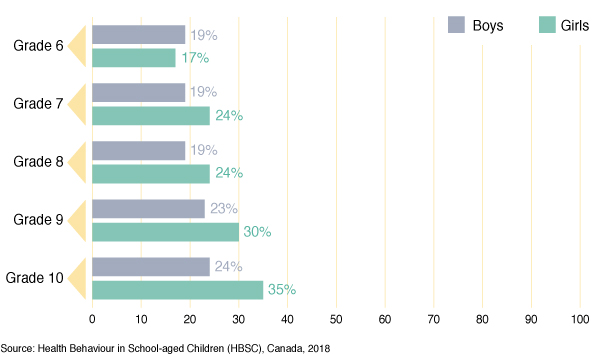

One-third of girls in grades 9 and 10 report that there are times when they would like to leave home

Girls are more likely than boys to report wanting to leave home.

24% of boys in grade 10 report having times when they wanted to leave home compared to 35% of grade 10 girls.

With increasing grade, there are more students reporting wanting to leave home. This increase is greater for girls than boys.

19% of grade 6 boys report that there are times they would like to leave home and it increases 5 percentage points to 24%, by grade 10.

17% of grade 6 girls report that there are times they would like to leave home and it increases 18 percentage points to 35%, by grade 10.

Figure 3 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 19 | 17 |

| Grade 7 | 19 | 24 |

| Grade 8 | 19 | 24 |

| Grade 9 | 23 | 30 |

| Grade 10 | 24 | 35 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

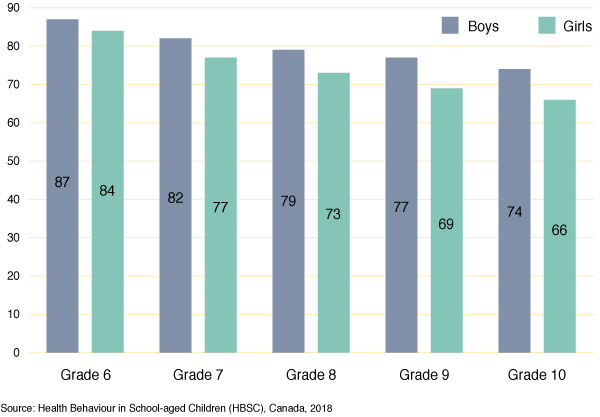

The majority of students report that it is easy to talk to their mother, but this decreases with grade

Boys are more likely than girls to report it is easy to talk to their mother about things that really bother them.

In grade 10, 74% of boys report it is easy to talk to their mother versus 66% of girls.

With increasing grade, fewer students report it is easy to talk to their mother.

In grade 6, 87% of boys report it is easy to talk to their mother compared to 74% in grade 10. Similarly for girls, ease of talking with their mother drops from 84% in grade 6 to 66% in grade 10.

Figure 4 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 87 | 84 |

| Grade 7 | 82 | 77 |

| Grade 8 | 79 | 73 |

| Grade 9 | 77 | 69 |

| Grade 10 | 74 | 66 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

With increasing grade, fewer students report that it is easy to talk to their father

Boys are more likely than girls to report it is easy to talk to their father about things that really bother them.

In grade 10, 59% of boys versus 44% of girls report it is easy to talk to their father.

With increasing grade, fewer students report it is easy to talk to their father.

In grade 6, 77% of boys report it is easy to talk to their father compared to 59% in grade 10, an 18 percentage point drop. Similarly for girls, ease talking to their father declines from 67% in grade 6 to 44% in grade 10, a 23 percentage point drop.

Fewer students report that it is easy to talk to their father than it is easy to talk to their mother.

Figure 5 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 77 | 67 |

| Grade 7 | 73 | 53 |

| Grade 8 | 67 | 50 |

| Grade 9 | 62 | 49 |

| Grade 10 | 59 | 44 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

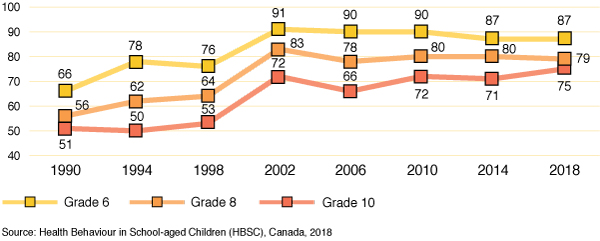

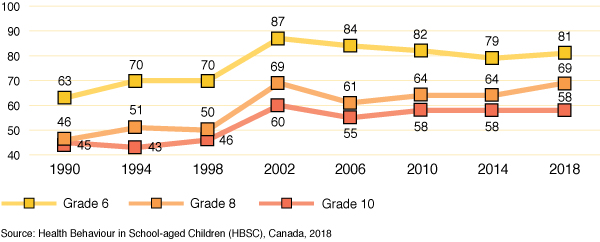

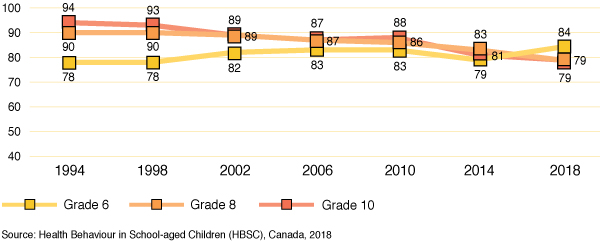

Over time, more students are reporting that they feel understood by their parents

In 1990, 51% of grade 10 boys reported they were understood by their parents, compared to 75% in 2018.

In 1990, 45% of grade 10 girls reported that they were understood by their parents, compared to 58% in 2018.

Boys are more likely than girls to report that they feel understood by their parents, 87% of grade 6 boys in 2018 versus 81% of grade 6 girls.

With increasing grade, fewer youth report feeling understood by their parents, 81% of grade 6 girls in 2018 versus 58% of grade 10 girls.

Figure 6a - Text description

| Year | Grade 6 | Grade 8 | Grade 10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 66 | 56 | 51 |

| 1994 | 78 | 62 | 50 |

| 1998 | 76 | 64 | 53 |

| 2002 | 91 | 83 | 72 |

| 2006 | 90 | 78 | 66 |

| 2010 | 90 | 80 | 72 |

| 2014 | 87 | 80 | 71 |

| 2018 | 87 | 79 | 75 |

Figure 6b - Text description

| Year | Grade 6 | Grade 8 | Grade 10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 63 | 46 | 45 |

| 1994 | 70 | 51 | 43 |

| 1998 | 70 | 50 | 46 |

| 2002 | 87 | 69 | 60 |

| 2006 | 84 | 61 | 55 |

| 2010 | 82 | 64 | 58 |

| 2014 | 79 | 64 | 58 |

| 2018 | 81 | 69 | 58 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | |||

Conclusions

- It is concerning that only one-half of Canadian grade 6 students are reporting feeling high support at home and that this percentage declines as grade increases, particularly for girls.

- It is encouraging that the majority of students report a happy home life. However, it is noteworthy that lower percentages of girls than boys report a happy home life and the percentage declines with grade.

- One-third of youth in grades 9 and 10 report thinking about leaving home. Again, older girls are more likely to report these feelings. Girls may be experiencing more conflict and stress in the home and may require support.

- Most youth report that it is easy to talk to their mother about things that really bother them, but fewer report it is easy to talk to their father. Boys report more ease communicating with parents than do girls. Again it is the older girls who are least likely to report ease of communicating, especially with fathers.

- Since 1990, more students are reporting that they feel understood by their parents, although this increase is less for the older students, particularly girls.

- Nonetheless, parents play an important role in the healthy development of youth (Parke & Buriel, 2006).

References

Bulanda, R., & Majumdar, D. (2009). Perceived parent-child relations and adolescent self-esteem. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18, 203-212.

Leon, R., Ray, S., & Evans, M. (2013). The lived experience of anxiety among late adolescents during high school: An interpretive phenomenological approach. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 31, 188-197.

Parke, R. D., & Buriel, R. (2006). Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology, (pp. 429-504). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Chapter 3: Friends

- Positive peer behaviours

- Risky peer behaviours

- Easy to talk to friends

- Friend support

- Online friend communication

- Trends in close friends

- Conclusions

Friends

Relationships with friends are highly influential for school-aged youth, contributing to psychological, social, and emotional development (Bukowski, Burmester, & Underwood, 2011). Friendships become especially salient during adolescence, as youth pursue greater autonomy from parents and deeper engagement with peers (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). This includes friendships with peers of the same and opposite sex (Lam, McHale, & Crouter, 2014). With the increased importance of peer relationships, friends become important sources of companionship, validation, and mutual support during adolescence (Juvonen, Espinoza, & Knifsend, 2012).

This chapter examines students’ friendships with their peers. These relationships are assessed by asking students how supported they feel by their friends and the ease with which they can communicate and share concerns with their friends. This chapter also explores positive social behaviours and the risk-taking behaviours of their peers.

Majority of students report that most of their friends do well at school and get along with parents

The majority of students in grades 9 and 10 report having friends who do well at school, with a higher percentage of girls than boys with friends who do well at school (71% versus 66%).

43% of grade 9 and 10 boys versus 53% of girls report having friends who help others.

16% of boys and 18% of girls report having friends who engage in cultural activities.

Figure 7 - Text description

| Positive behaviour | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Do well at school | 66 | 71 |

| Participate in sports | 51 | 47 |

| Participate in cultural activities | 16 | 18 |

| Get along with parents | 66 | 59 |

| Care for environment | 35 | 42 |

| Help others | 43 | 53 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

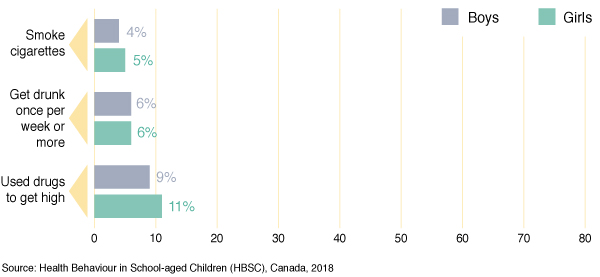

Minority of grade 9 and 10 students report that most of their friends engage in risky behaviours

In grades 9 and 10, 4% of boys and 5% of girls report that most of their friends smoke.

6% of students report that most of their friends get drunk at least once a week.

Grade 9 and 10 students are more likely to report that most of their friends use drugs to get high (11% of girls; 9% of boys) than smoke cigarettes (4%).

Both boys and girls agreed that they would likely participate in risky behaviours if their friends were doing them.

[Youth Workshop Group Reflections]

Figure 8 - Text description

| Risky behaviour | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Smoke cigarettes | 4 | 5 |

| Get drunk once per week or more | 6 | 6 |

| Used drugs to get high | 9 | 11 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

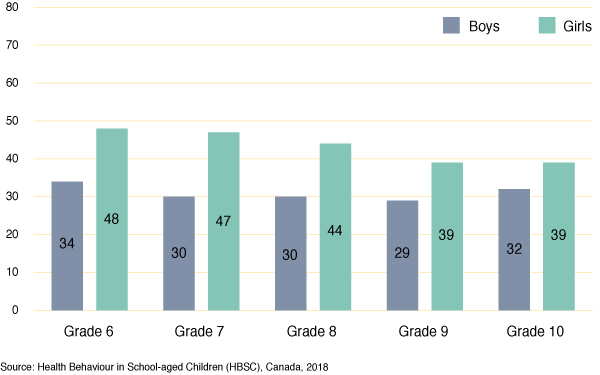

A higher percentage of girls than boys report having high friend support

44% of girls in grade 8 compared to 30% of grade 8 boys report having high friend support.

For girls, with increasing grade, fewer report high friend support, 48% of girls in grade 6 to 39% in grade 10.

Figure 9 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 34 | 48 |

| Grade 7 | 30 | 47 |

| Grade 8 | 30 | 44 |

| Grade 9 | 29 | 39 |

| Grade 10 | 32 | 39 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

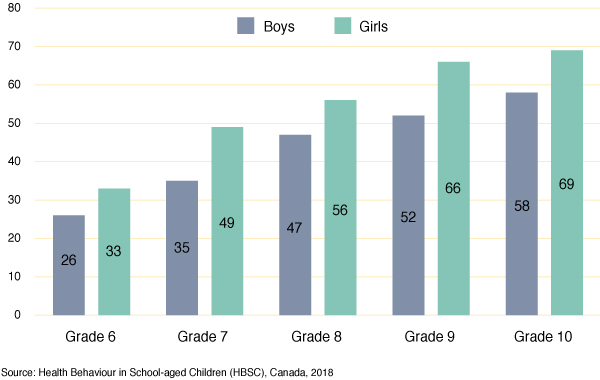

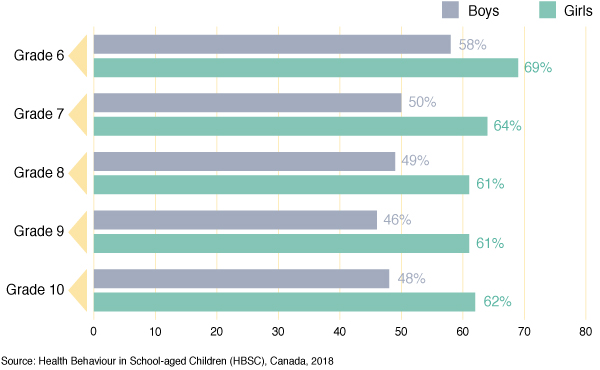

With increasing grade, students are more likely to communicate with friends online

Girls are more likely than boys to communicate frequently with their close friends online.

In grade 10, 69% of girls versus 58% of boys report having online communication with close friends several times a day.

With increasing grade, students report increased online communication with close friends.

26% of grade 6 boys report communicating online several times a day versus 58% of grade 10 boys.

In the survey, ‘online communication’ was defined as ‘sending and receiving text messages, emojis, and photo, video, or audio messages through instant, social network sites, or e-mail (on a computer, laptop, tablet, or smartphone)’.

Figure 10 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 26 | 33 |

| Grade 7 | 35 | 49 |

| Grade 8 | 47 | 56 |

| Grade 9 | 52 | 66 |

| Grade 10 | 58 | 69 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

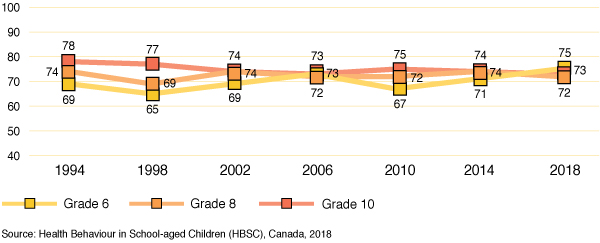

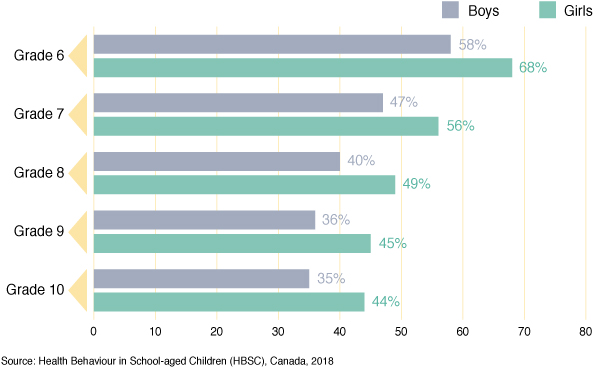

Compared to 1994, fewer grade 8 and 10 girls report having a same-sex friend to talk to in 2018

Over time, fewer grade 8 and 10 girls report having a same-sex friend to talk to about things that bother them, while for boys it is relatively stable.

For example, in 1994, 90% of grade 8 girls report having a same-sex friend to talk to versus 79% in 2018.

In 1994, 94% of grade 10 girls report having a same-sex friend to talk to versus 79% in 2018.

Figure 11a - Text description

| Year | Grade 6 | Grade 8 | Grade 10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 69 | 74 | 78 |

| 1998 | 65 | 69 | 77 |

| 2002 | 69 | 74 | 74 |

| 2006 | 73 | 72 | 73 |

| 2010 | 67 | 72 | 75 |

| 2014 | 71 | 74 | 74 |

| 2018 | 75 | 72 | 73 |

Figure 11b - Text description

| Year | Grade 6 | Grade 8 | Grade 10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 78 | 90 | 94 |

| 1998 | 78 | 90 | 93 |

| 2002 | 82 | 89 | 89 |

| 2006 | 83 | 87 | 87 |

| 2010 | 83 | 86 | 88 |

| 2014 | 79 | 83 | 81 |

| 2018 | 84 | 79 | 79 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | |||

Conclusions

- The majority of youth are reporting having friends who engage in positive behaviours. These friendships can have the benefit of strengthening adaptive behaviours (Bukowski et al., 2011).

- A minority of students report having friends who engage in risky behaviour – although 11% of grade 9 and 10 girls report having friends who use drugs. Having close friends who engage in risky behaviours can increase the likelihood that the youth will also engage in that behaviour (Lam et al., 2014).

- More girls than boys report having high friend support. Since 1994, fewer girls are reporting having a same-sex friend that they can talk to about issues that bother them. Social support is a protective factor for mental health (Reinke et al., 2011).

- A majority of students have daily online communication, and it is more prevalent for girls. Communication among friends provides opportunities to develop intimacy, to share interpersonal issues, and to support one another (Bukowski et al., 2011).

- Healthy relationships with peers can help prevent negative outcomes and promote healthy development (Craig & Pepler, 2014).

References

Bukowski, W. M., Buhrmester, D., & Underwood, M. K. (2011). Peer Relations as a Developmental Context. In M. K. Underwood & L. H. Rosen (Eds.), Social Development: Relationships in Infancy, Childhood, and Adolescence (pp. 153–179).

Craig, W., & Pepler, D. (2014). Trends in Healthy Development and Healthy Relationships. Public Health Agency of Canada.

Juvonen, J., Espinoza, G., & Knifsend, C. (2012). The role of peer relationships in student academic and extracurricular engagement. In S. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 387–401). New York, NY: Springer. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Lam, C. B., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2014). Time with peers from middle childhood to late adolescence: Developmental course and adjustment correlates. Child Development, 85, 1677–1693. doi:10.1111/cdev.12235

Reinke, W., Stormont, M., Herman, K., Puri, R., & Goel, N. (2011). Supporting children’s mental health in schools: Teacher perceptions of needs, roles, and barriers. School Psychology Quarterly, 26, 433–449.

Steinberg, L., & Morris, A. S. (2000). Adolescent Development. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 83–110. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83

Chapter 4: School

- School pressure

- Caring teachers

- Kind classmates

- School climate

- Conclusions

Schools

In addition to educating students, schools also influence their social-emotional health and well-being (Anderman, 2002; Kidger et al., 2012; McLaughlin, 2008). Students who have positive experiences at school are less likely to have mental health problems and engage in risk-taking behaviours than students who experience school negatively (McLaughlin, 2008). On the other hand, students who experience a negative school climate report lower self-confidence and lower self-esteem (King et al., 2002).

This chapter examines students’ experiences of pressure at school. In addition, it explores students’ relationships with school teachers and classmates.

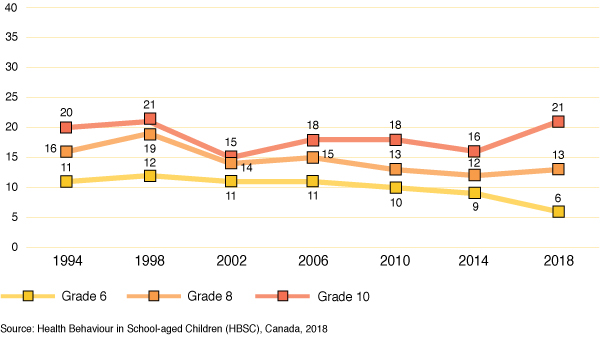

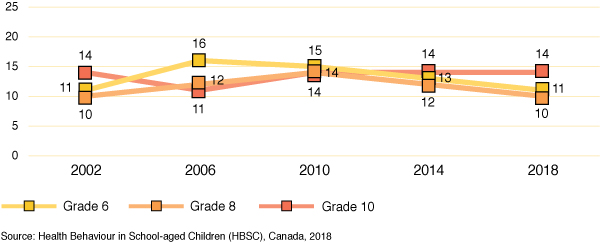

In 2018, 1 in 5 grade 10 boys report feeling a lot of school pressure

Compared to those in the younger grades, more grade 10 boys report feeling a lot of school pressure. This pattern is found consistently from 1994 to 2018.

For example, in 2018, 21% of grade10 boys versus 6% of grade 6 boys report feeling a lot of school pressure.

From 2014 to 2018, the percentage of grade 10 boys reporting feeling a lot of school pressure has increased from 16% to 21%.

Figure 12 - Text description

| Year | Grade 6 | Grade 8 | Grade 10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 11 | 16 | 20 |

| 1998 | 12 | 19 | 21 |

| 2002 | 11 | 14 | 15 |

| 2006 | 11 | 15 | 18 |

| 2010 | 10 | 13 | 18 |

| 2014 | 9 | 12 | 16 |

| 2018 | 6 | 13 | 21 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | |||

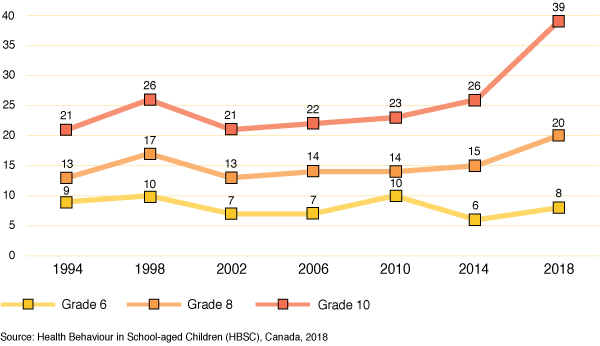

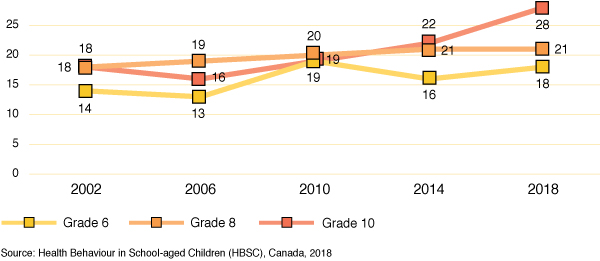

In 2018, 2 in 5 grade 10 girls report feeling a lot of school pressure

Compared to those in the younger grades, more grade 10 girls report feeling a lot of school pressure and this pattern is found consistently from 1994 to 2018.

For example, in 2018, 39% of grade 10 girls report feeling a lot of school pressure versus 8% of grade 6 girls.

For Grade 8 girls, and especially grade 10 girls, the proportion reporting that they feel a lot of pressure from school work increases dramatically between 2014 and 2018.

Figure 13 - Text description

| Year | Grade 6 | Grade 8 | Grade 10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 9 | 13 | 21 |

| 1998 | 10 | 17 | 26 |

| 2002 | 7 | 13 | 21 |

| 2006 | 7 | 14 | 22 |

| 2010 | 10 | 14 | 23 |

| 2014 | 6 | 15 | 26 |

| 2018 | 8 | 20 | 39 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | |||

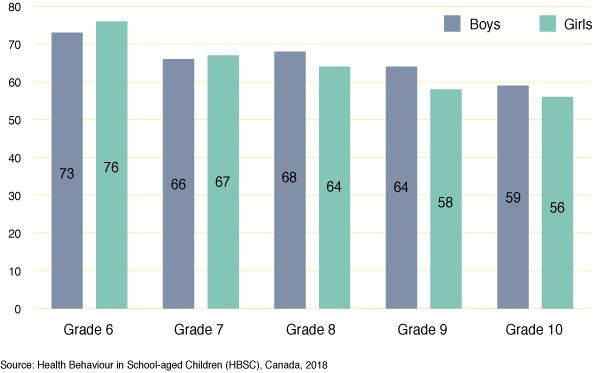

Students in higher grades are less likely to report that teachers care about them

In grade 6, 76% of girls report that teachers care about them versus 56% of girls in grade 10.

Similarly, 73% of grade 6 boys report that their teachers care about them versus 59% of grade 10 boys.

In grades 8, 9, and 10, boys are more likely than girls to report that teachers care about them.

Young people talked about the need to feel respect from teachers in order to feel supported. When students were asked what makes them feel supported at school they said:

“When teachers believe in you and know your strengths and weaknesses.”; “Teachers greeting us and saying hello.”; “Teachers that stand by you and respect you and talk to you.”

[Youth Workshop Group Reflections]

Figure 14 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 73 | 76 |

| Grade 7 | 66 | 67 |

| Grade 8 | 68 | 64 |

| Grade 9 | 64 | 58 |

| Grade 10 | 59 | 56 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

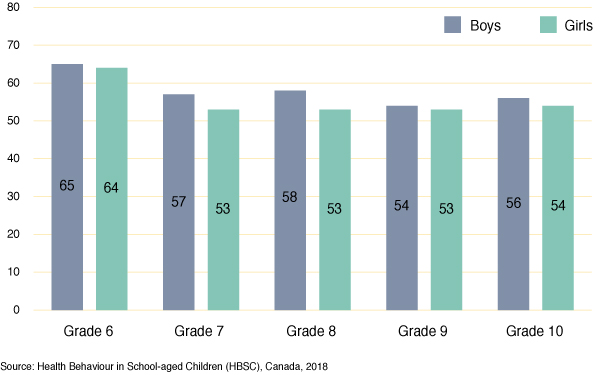

With increasing grade, students are less likely to report that other students are kind and helpful

65% of grade 6 boys versus 56% of grade 10 boys report that other students are kind and helpful.

64% of grade 6 girls versus 54% of grade 10 girls report that other students are kind and helpful.

Figure 15 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 65 | 64 |

| Grade 7 | 57 | 53 |

| Grade 8 | 58 | 53 |

| Grade 9 | 54 | 53 |

| Grade 10 | 56 | 54 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

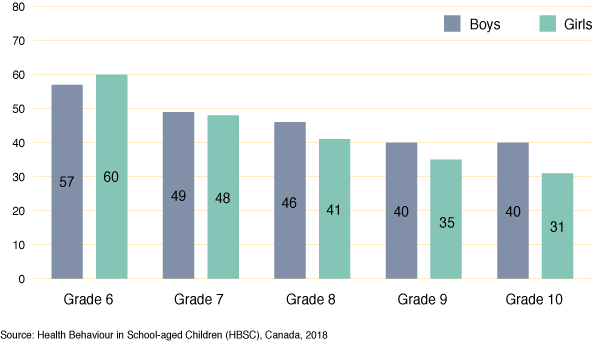

In the higher grades, fewer students report a positive school climate

School climate assesses students’ opinion of school (liking school, feeling a sense of belonging, feeling their school is a nice place to be and that the rules at school are fair).

The percentage of boys reporting a more positive school climate decreases from Grade 6 (57%) to Grade 9 (40%).

For girls, the drop in the percentage who report a more positive school climate is even greater than it is for boys, from 60% in Grade 6 to 31% in Grade 10.

In Grades 6 and 7, the percentage of girls and boys who report a positive school climate is similar, but by Grade 10, there are many fewer girls than boys who report a positive school climate.

“Teachers think that [older students] are more mature and don’t need as much help; trying to prepare [us] for the ‘real world’.”

[Youth Workshop Participant]

Figure 16 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 57 | 60 |

| Grade 7 | 49 | 48 |

| Grade 8 | 46 | 41 |

| Grade 9 | 40 | 35 |

| Grade 10 | 40 | 31 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

Conclusions

- It is concerning that the percentage of students reporting a lot of school pressure in grade 10 has increased over the past 4 years, particularly for girls.

- Grade 10 girls report more school pressure than boys and this trend is consistent over time.

- A cause for concern is that with increasing grade, fewer students are reporting that teachers care about them. While a majority of students still reported that teachers care about them, a decline in social support from teachers may have a negative impact on student mental health and well-being (Kidger et al., 2012).

- With increasing grade, fewer students are reporting that their peers are kind and helpful. This lack of support from peers may also have a negative impact on students’ well-being (Craig & Pepler, 2014).

- Support from schools and families may help students cope with feelings of school pressure (Craig & Pepler, 2014).

- With increasing grade, fewer students report experiencing a positive school climate. Having a positive school climate is related to increased academic performance and more positive social relationships (McLaughlin, 2008).

References

Anderman, E. M. (2002). School effects on psychological outcomes during adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 795–809.

Craig, W., & Pepler, D. (2014). Trends in Healthy Development and Healthy Relationships. Public Health Agency of Canada.

Kidger, J., Araya, R., Donovan, J., & Gunnell, D. (2012). The effect of the school environment on the emotional health of adolescents: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 129, 1–25.

King, K. A., Vidourek, R. A., Davis, B., & McClellan, W. (2002). Increasing self‐esteem and school connectedness through a multidimensional mentoring program. Journal of School Health, 72, 294–299.

McLaughlin, C. (2008). Emotional well-being and its relationship to schools and classrooms: A critical reflection. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 36, 353–366.

Chapter 5: Community

- Community support

- Neighbourhood trust

- Volunteering

- Conclusions

Communities

Communities refer to the neighbourhoods where young people live, play, and grow up. Groups and activities in which young people participate represent important parts of such communities. Together, these neighbourhoods and groups offer important benefits to health. A healthy community will provide support to young people in making good behavioural choices, and in educating them about decisions that enhance their health and well-being (Ellen, Mijanovich, & Dillman, 2001).

In this chapter, we examine young people’s perceptions of the supports that they receive in their communities, and the extent to which they trust the people in their neighbourhood. We also examine the proportions of young people who volunteer on a regular basis.

Perceived levels of community support decline with grade

Here we report on a scale that measures community support using five items that ask about the quality of social relationships, safety, trust, and community leisure spaces.

One-half or fewer students in each grade and gender group report a high level of community support.

Among both boys and girls, perceived levels of community support decline as grade increases. For example, 48% of grade 6 girls report a high level of community support versus 38% of grade 10 girls, a difference of 10 percentage points.

Overall, boys are more positive than girls about their level of community support. For example, in grade 10, 43% of boys report a high level of community support compared to 38% of girls.

Figure 17 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 50 | 48 |

| Grade 7 | 48 | 43 |

| Grade 8 | 45 | 41 |

| Grade 9 | 43 | 40 |

| Grade 10 | 43 | 38 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

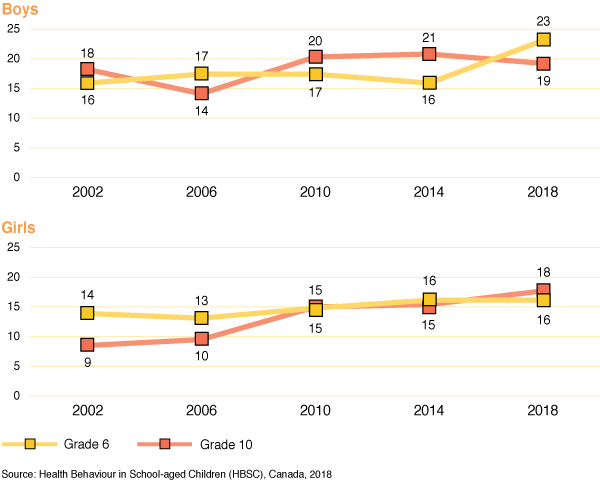

Young people’s level of neighbourhood distrust is on the rise

Among both girls and boys, levels of distrust of the people in their neighbourhoods is low.

For example, in grade 10 boys, the proportion expressing distrust of the people in their community is one-fifth or less across the years.

However, among both girls and boys, levels of distrust in their community rise between 2002 and 2018.

For example, in grade 10 girls, the proportion expressing distrust of the people in their community rises from 9% in 2002 to 18% in 2018.

“If something isn’t right in your neighbourhood, you don’t feel like you belong there. Because I didn’t know a lot of people there it really wasn’t my space.”

[Youth Workshop Participant]

Figure 18 - Text description

Figure 18: Percentage of students who agree or strongly agree that people in the area where they live would try to take advantage of them if they got the chance, by grade, gender and year of survey

| Year | Grade 6 | Grade 10 |

|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 16 | 18 |

| 2006 | 17 | 14 |

| 2010 | 17 | 20 |

| 2014 | 16 | 21 |

| 2018 | 23 | 19 |

| Year | Grade 6 | Grade 10 |

|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 14 | 9 |

| 2006 | 13 | 10 |

| 2010 | 15 | 15 |

| 2014 | 16 | 15 |

| 2018 | 16 | 18 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

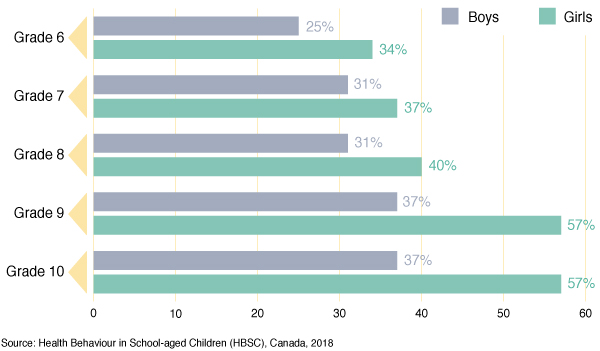

Girls get involved in volunteer work more than boys

In each of grades 6 to 10, more girls report involvement in volunteer work than do boys.

For example, in both grades 9 and 10, the percentage of girls who report volunteering is 57% versus 37% of boys.

In boys, proportions reporting involvement in volunteer work range from a low of 25% in grade 6 to a high of 37% in grades 9 and 10.

Figure 19 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 25 | 34 |

| Grade 7 | 31 | 37 |

| Grade 8 | 31 | 40 |

| Grade 9 | 37 | 57 |

| Grade 10 | 37 | 57 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

Conclusions

- It is concerning that less than one-half of young people feel high levels of support from the communities where they live.

- Increases in levels of neighbourhood distrust are noteworthy and should be monitored over time.

- In Canada, girls appear to be more likely to get involved in volunteer work, a prosocial behaviour.

References

Ellen, I. G., Mijanovich, T., & Dillman, K. N. (2001). Neighborhood effects on health: Exploring the links and assessing the evidence. Journal of Urban Affairs, 23, 391-408.

Chapter 6: Physical activity, screen time, and sleep

- Physical activity

- Screen time

- Sleep

- Conclusions

Movement behaviours

Movement ranges in intensity from vigorous exercise at the high end to sleep at the low end. Movement behaviours include physical activity (e.g., sports, outdoor play), sedentary behaviour (e.g., screen time), and sleep. For optimal health, the Canadian 24-hour Movement Guidelines (Tremblay et al., 2016) encourage youth to achieve high levels of physical activity, low levels of sedentary behaviour and recreational screen time, and sufficient sleep each day.

In this chapter, we describe the amount of time youth report that they spend engaged in physical activity, recreational screen time, and sleep. Collectively, we refer to such behaviours as “movement behaviours”.

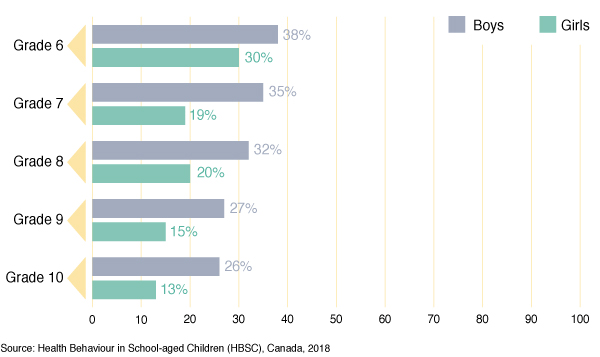

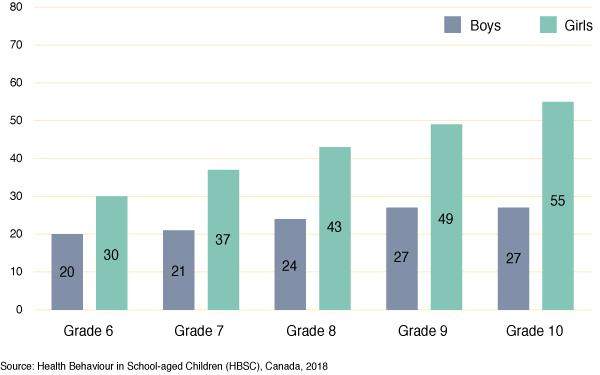

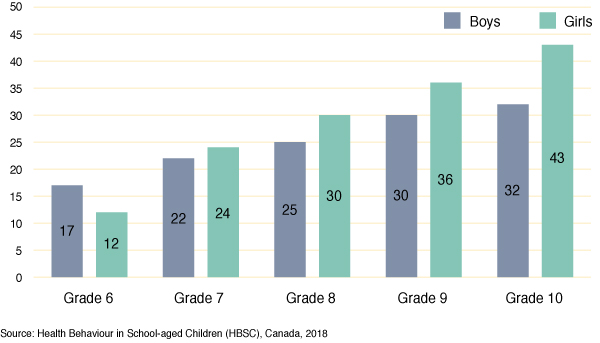

Most young people are not participating in regular physical activity, and girls are participating less than boys

Among boys, the proportion who report being active for at least 60 minutes a day over the past seven days declines from 38% in grade 6 to 26% in grade 10.

Among girls, the proportion who report being active for at least 60 minutes a day over the past seven days declines from 30% in grade 6 to 13% in grade 10.

More boys than girls participate in regular physical activity at all grade levels.

Young people attribute the lower levels of engagement of girls in physical activity to a number of factors, including: (1) girls are often less comfortable engaging in activities in front of others; (2) girls often have less opportunities to engage in physical activities than do boys (for example, contact sports such as football, rugby or hockey), and (3) boys have more friends who engage in physical activities than do girls, and they also have more role models in sports to look up to.

[Youth Workshop Group Reflections]

Figure 20 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 38 | 30 |

| Grade 7 | 35 | 19 |

| Grade 8 | 32 | 20 |

| Grade 9 | 27 | 15 |

| Grade 10 | 26 | 13 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

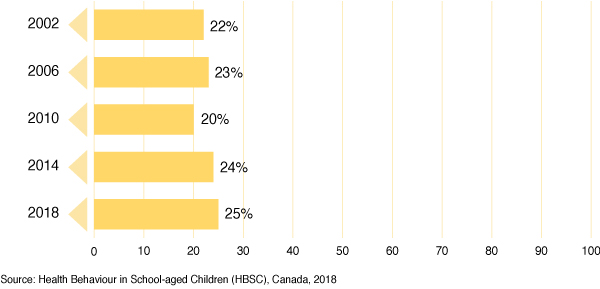

25% of young people report at least 60 minutes per day of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity

Among students in grades 6 to 10, those reporting at least 60 minutes per day of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity varied from 20% to 25% from 2002 to 2018.

Figure 21 - Text description

| 2002 | 22 |

|---|---|

| 2006 | 23 |

| 2010 | 20 |

| 2014 | 24 |

| 2018 | 25 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | |

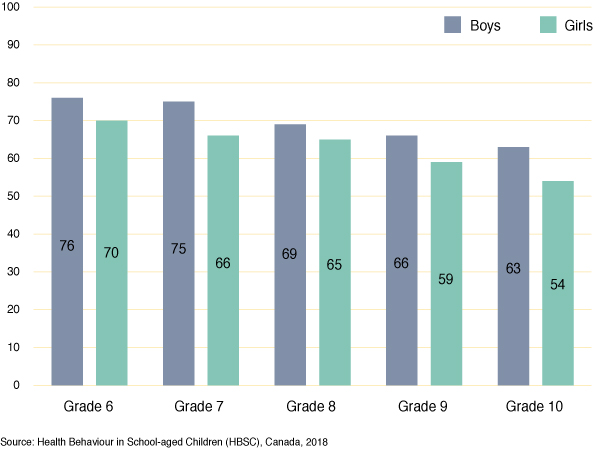

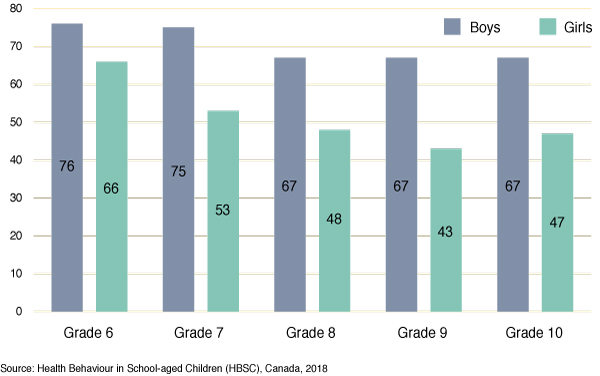

Participation in organized sports is more common in boys, and declines by grade

Among boys, participation in organized sports declines from 76% in grade 6 to 63% in grade 10.

Among girls, this decline goes from 70% in grade 6 to 54% in grade 10.

Higher percentages of boys than girls report participating in a team-based organized sport.

Higher percentages of girls than boys report participating in an individual-based organized sport.

Figure 22 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 76 | 70 |

| Grade 7 | 75 | 66 |

| Grade 8 | 69 | 65 |

| Grade 9 | 66 | 59 |

| Grade 10 | 63 | 54 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

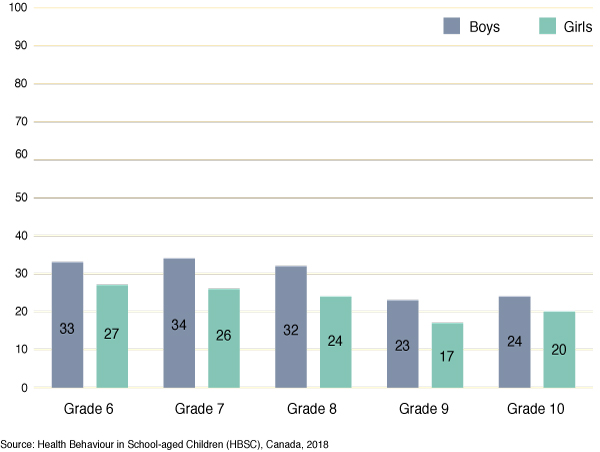

Active transportation to school

One-third or fewer students across all grades use active transportation to go to school in the morning and there is a general decline as grade increases.

Higher percentages of boys than girls report regularly walking or bicycling to school.

Higher proportions of students who report they take 15 minutes or less to get to school report that they use active transportation (36%) compared to those who took more than 15 minutes to get to school (12%).

Figure 23 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 33 | 27 |

| Grade 7 | 34 | 26 |

| Grade 8 | 32 | 24 |

| Grade 9 | 23 | 17 |

| Grade 10 | 24 | 20 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

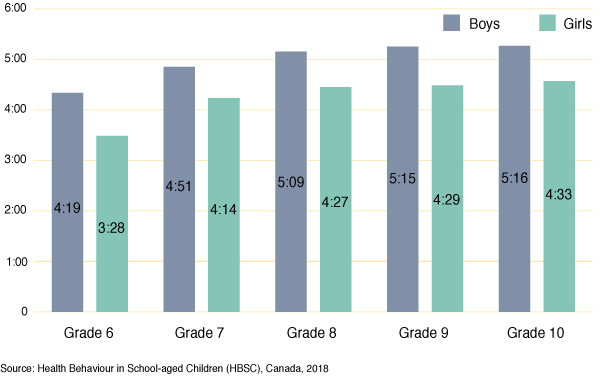

Screen time differs by grade and gender

In 2019, the Canadian Paediatric Society published new recommendations for screen time use in children that emphasized four “essential Ms”: managed, meaningful, modeled, and monitored (Ponti et al., 2019).

Among boys, average amounts of screen time increase from 4 hours and 19 minutes per day in grade 6, to 5 hours and 16 minutes in grade 10.

Among girls, screen time increases from 3 hours and 28 minutes per day in grade 6, to 4 hours and 33 minutes in grade 10.

Boys consistently report more screen time than girls.

Screen time increases from grade 6 to 10 in both boys and girls.

Figure 24 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 4:19 | 3:28 |

| Grade 7 | 4:51 | 4:14 |

| Grade 8 | 5:09 | 4:27 |

| Grade 9 | 5:15 | 4:29 |

| Grade 10 | 5:16 | 4:33 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

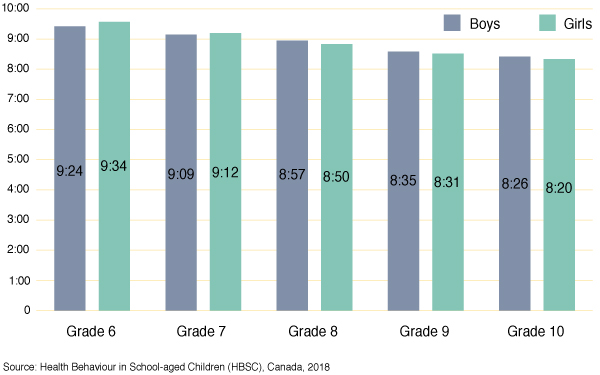

Sleep duration differs by grade but not by gender

The Canadian 24-hour Movement Guidelines (Tremblay et al., 2016) suggest that from ages 5 to 13, children require 9 to 11 hours of sleep per night. This recommendation changes to 8 to10 hours among those aged 14 to 17.

Among boys, average amounts of sleep drop from 9 hours and 24 minutes per night in grade 6, to 8 hours and 26 minutes in grade 10.

Among girls, average amounts of sleep drop from 9 hours and 34 minutes per night in grade 6, to 8 hours and 20 minutes in grade 10.

Figure 25 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 9:24 | 9:34 |

| Grade 7 | 9:09 | 9:12 |

| Grade 8 | 8:57 | 8:50 |

| Grade 9 | 8:35 | 8:31 |

| Grade 10 | 8:25 | 8:20 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

Conclusions

- The proportion of Canadian students in grades 6 to 10 that report participating in at least 60 minutes per day of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity has not exceeded 25% from 2002 to 2018.

- The average levels of screen time reported by boys and girls at all grade levels far exceed the 2 hours per day of recreational screen time recommended in the Canadian 24-hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth.

- Most young people adhere to sleep recommendations in the Canadian 24-hour Movement Guidelines.

- One-third or fewer students across all grades use active transportation to go to school in the morning.

References

Ponti, M., & the Canadian Paediatric Society Digital Health Task Force (2019). Digital media: Promoting healthy screen use in school-aged children and adolescents. Retrieved from: https://www.cps.ca/en/documents/position/digital-media.

Tremblay, M. S., Carson, V., Chaput, J. P., Connor Gorber, S., Dinh, T., Duggan, M., ... & Janssen, I. (2016). Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth: an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep.Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 41(6), S311-S327.

Chapter 7: Healthy eating

- Healthy and unhealthy foods

- Fast food

- Eating breakfast

- Hunger

- Conclusions

Healthy eating

Healthy eating is important for the healthy development of children and youth (Health Canada, 2019) and to reduce the risk of obesity later in life (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2012). Unhealthy eating behaviours that begin during adolescence may continue into adulthood, creating negative conditions for a wide variety of eating-related concerns (Vereecken, 2005). Where and when young people eat, or not, can have a great influence on their body weight and other related nutritional and mental health outcomes. Food insecurity can also have a bearing on their eating habits (Kirkpatrick et al., 2015).

This chapter describes the foods that young people eat, and behaviours and practices that may influence their nutrition. These include the frequency of eating at fast food restaurants and skipping breakfast. The frequency of going to school or bed hungry due to not having enough food in the home is also presented.

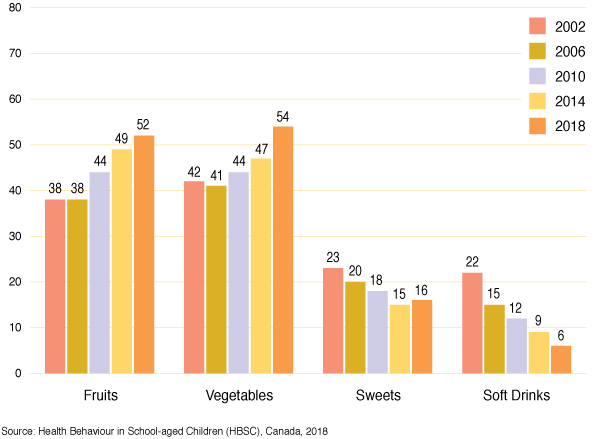

The dietary habits of young Canadians are improving

From 2002 to 2018, the proportion of young people reporting daily consumption of fruits increases from 38% to 52%.

Daily consumption of vegetables increases from 42% to 54% over the same time period.

Daily consumption of sweets decreases from 23% to 16% from 2002 to 2018.

Daily consumption of soft drinks decreases from 22% to 6% in the same time period.

Figure 26 - Text description

| Types of food | 2002 | 2006 | 2010 | 2014 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruits | 38 | 38 | 44 | 49 | 52 |

| Vegetables | 42 | 41 | 44 | 47 | 54 |

| Sweets | 23 | 20 | 18 | 15 | 16 |

| Soft Drinks | 22 | 15 | 12 | 9 | 6 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | |||||

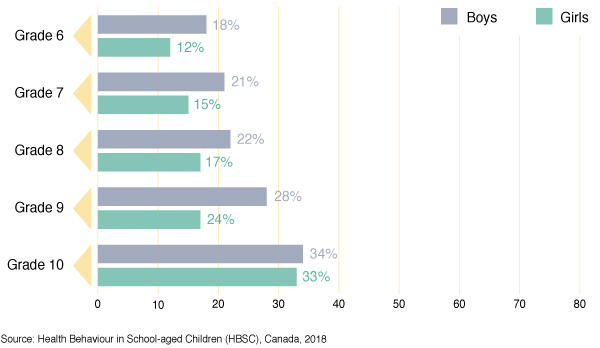

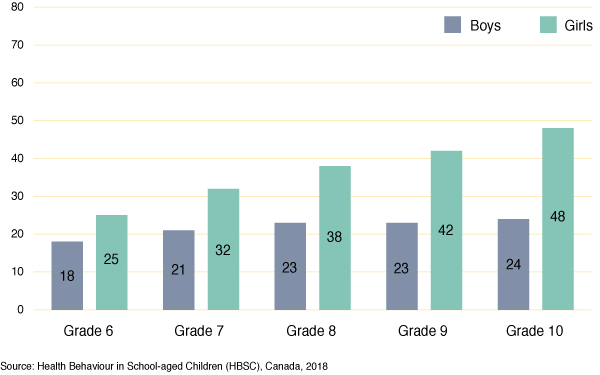

Fast food consumption occurs more often in higher grades

Weekly consumption of food in a fast food restaurant increases as young people grow older.

For example, 18% of grade 6 boys, 22% of grade 8 boys, and 34% of grade 10 boys report eating fast food at least once per week.

In girls, the proportion reporting fast food consumption is slightly less than boys, in grades 6 to 9.

Figure 27 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 18 | 12 |

| Grade 7 | 21 | 15 |

| Grade 8 | 22 | 17 |

| Grade 9 | 28 | 24 |

| Grade 10 | 34 | 33 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

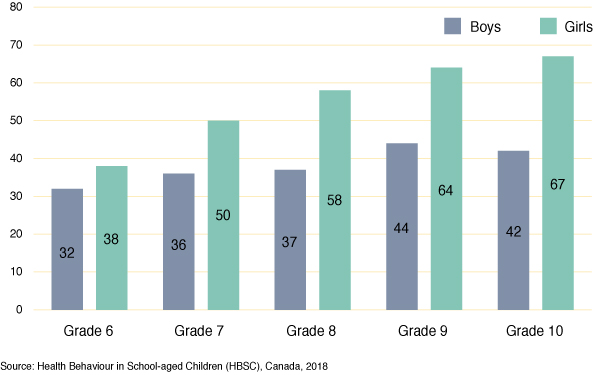

Breakfast consumption patterns vary by grade and gender

In boys, proportions reporting that they usually consume breakfast decline from 76% in grade 6, to 59% in grade 10.

In girls, these proportions drop from a high of 70% in grade 6, to a low of 43% in grade 10.

Breakfast consumption is more common among boys than girls in all grades.

There are lots of factors involved in skipping breakfast, including the need to get ready, finishing homework and the time required to travel to school.

[Youth Workshop Group Reflections]

Figure 28 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 76 | 70 |

| Grade 7 | 66 | 58 |

| Grade 8 | 64 | 51 |

| Grade 9 | 60 | 45 |

| Grade 10 | 59 | 43 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

Hunger is experienced by many young Canadians

In all grade levels and for both genders, 2 to 4% of students report often or always going to school or bed hungry because there is not enough food at home.

A further 11 to 17% report that they sometimes experience such hunger.

There is no consistent pattern in the occurrence of hunger by gender or grade.

Young people talked about how expensive it can be to eat healthy, especially in more northern and remote communities, and how this can be a barrier to eating healthy.

[Youth Workshop Group Reflections]

Figure 29 - Text description

| Grade | Gender | Sometimes | Often or always |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | Boys | 16 | 3 |

| Girls | 14 | 4 | |

| Grade 7 | Boys | 15 | 3 |

| Girls | 17 | 2 | |

| Grade 8 | Boys | 14 | 3 |

| Girls | 11 | 3 | |

| Grade 9 | Boys | 13 | 3 |

| Girls | 12 | 2 | |

| Grade 10 | Boys | 12 | 4 |

| Girls | 15 | 2 | |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | |||

Conclusions

- The proportion of young people reporting daily consumption of fruits and vegetables continues to increase, while the proportion reporting consumption of unhealthy foods such as sweets and soft drinks continues to decline.

- Despite this positive trend, one-third of grade 10 boys and girls report eating in a fast food restaurant at least on a weekly basis.

- Although not eating breakfast is associated with increased risk of nutritional inadequacies and poorer cognition, daily breakfast eating declines dramatically in the older grades.

- Up to 1 in 5 young people report going to school or bed hungry at least sometimes because there is not enough food at home. For 2-4% this occurs often or always. There are many possible explanations for this hunger, but it remains an important concern affecting the health and academic success of young people.

References

Health Canada. (2019). Eating well with Canada’s Food Guide. Retrieved from https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/

Kirkpatrick, S. I., Dodd, K. W., Parsons, R., Ng, C., Garriguet, D., & Tarasuk, V. (2015). Household food insecurity is a stronger marker of adequacy of nutrient intakes among Canadian compared to American youth and adults. The Journal of Nutrition, 145(7), 1596-1603.

Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC]. (2012). Curbing childhood obesity: A federal, provincial and territorial framework for action to promote healthy weights. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/migration/phac-aspc/hp-ps/hl-mvs/framework-cadre/pdf/ccofw-eng.pdf

Vereecken, C. A., Inchley, J., Subramanian, S. V., Hublet, A., & Maes, L. (2005). The relative influence of individual and contextual socio-economic status on consumption of fruit and soft drinks among adolescents in Europe. The European Journal of Public Health, 15(3), 224-232.

Chapter 8: Healthy weights

- Overweight and obesity

- Weight-based teasing

- Body image

- Conclusions

Healthy weights

A healthy weight is a weight that is appropriate for a person’s height and promotes good health and well-being. Simply defined, the terms overweight and obesity represent a state where an individual has excess body weight and fat to the extent that it affects his or her health in a negative way (World Health Organization, 1998). Body weight issues, and the behaviours and stigmas to which young people are subject, due to perceptions of the look of their bodies, are also major adolescent health concerns among young people (Puhl & Suh, 2015).

In this chapter, we report on overweight and obesity, weight-based teasing (body shaming) and body image. Overweight and obesity were determined using body mass index (BMI) based on self-reported height and weight. Height and weight measurements were not taken as part of the survey.

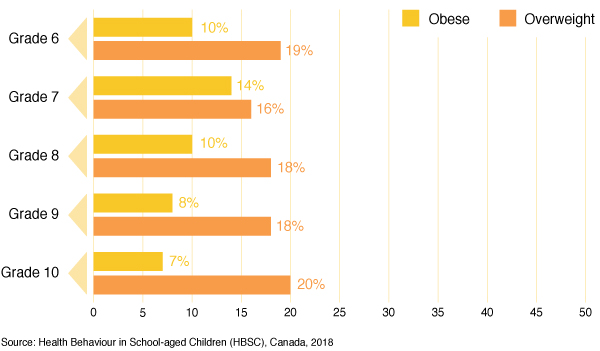

1 in 4 boys in Canada have a BMI categorized as obese or overweight

In grades 6 to 10, between 7% and 14% of boys have a BMI categorized as obese.

By grade, between 16% and 20% of boys have a BMI categorized as overweight.

Among boys, obesity peaks in grade 7, then declines as they enter the high school years.

Among boys, the prevalence of overweight remains relatively stable by grade level.

Figure 30 - Text description

| Grade | Obese | Overweight |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 10 | 19 |

| Grade 7 | 14 | 16 |

| Grade 8 | 10 | 18 |

| Grade 9 | 8 | 18 |

| Grade 10 | 7 | 20 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

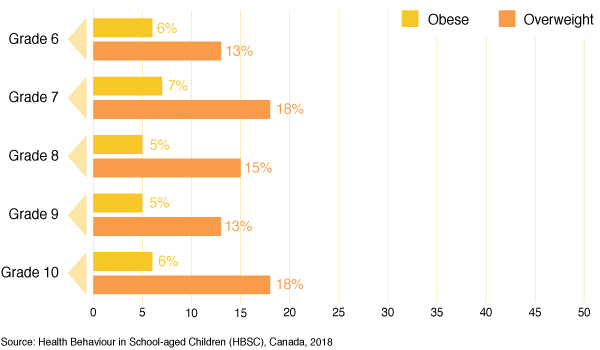

Overweight and obesity remain common in girls

By grade, between 5% and 7% of girls have a BMI categorized as obese.

By grade, between 13% and 18% of girls have a BMI categorized as overweight.

Overall prevalence of obesity, based on self-reported heights and weights, are lower among girls than boys.

Figure 31 - Text description

| Grade | Obese | Overweight |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 6 | 13 |

| Grade 7 | 7 | 18 |

| Grade 8 | 5 | 15 |

| Grade 9 | 5 | 13 |

| Grade 10 | 6 | 18 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

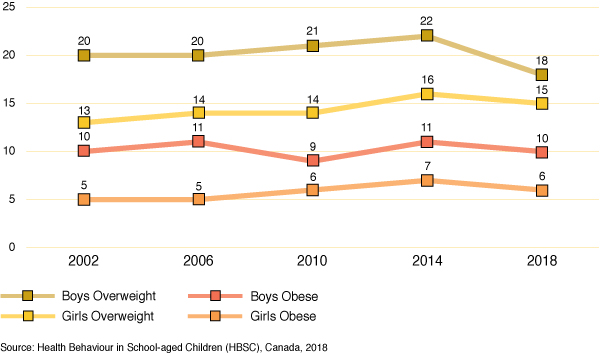

Percentages of students with a BMI categorized as overweight and obese have not changed much over time

Among boys in grades 6 to 10 combined, the prevalence of obesity ranged from 9% to 11% and overweight ranged from 18% to 22% between 2002 and 2018.

Among girls, the prevalence of obesity ranged from 5% to 7% and overweight ranged from 13% to 16% between 2002 and 2018.

Figure 32 - Text description

| Year | Boys Overweight | Boys Obese | Girls Overweight | Girls Obese |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 20 | 10 | 13 | 5 |

| 2006 | 20 | 11 | 14 | 5 |

| 2010 | 21 | 9 | 14 | 6 |

| 2014 | 22 | 11 | 16 | 7 |

| 2018 | 18 | 10 | 15 | 6 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||||

Body shaming is experienced by almost 1 in 10 young people

Among boys, the prevalence of reported weight-based teasing varies from 5% to 9% by grade level.

Among girls, the prevalence of reported weight-based teasing varies from 6% to 10% by grade level.

Figure 33 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 5 | 6 |

| Grade 7 | 9 | 10 |

| Grade 8 | 8 | 9 |

| Grade 9 | 9 | 7 |

| Grade 10 | 6 | 8 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

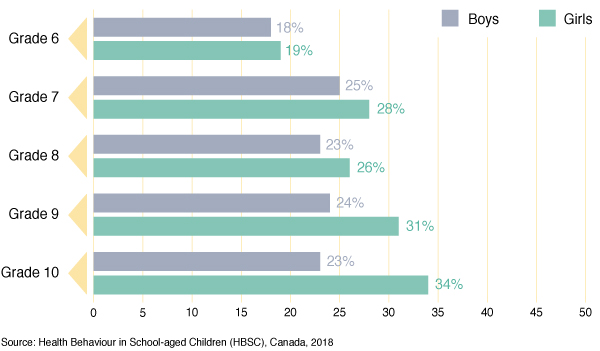

Up to 1 in 3 young people perceive that their body is “too fat”

In general, girls report that they perceive their body to be “too fat” more often than boys.

Among boys, the percentage that perceive their body as being “too fat” ranges from 18% to 25% by grade level.

Among girls, the percentage that perceive their body as being “too fat” rises from 19% in grade 6 to 34% in grade 10.

“Boys are told by social media and society that they should be “buff”, but naturally in grades 6 to 10 they are often skinny. Girls are told that they should have a “perfect hour glass figure”.

[Youth Workshop Participant]

Figure 34 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 18 | 19 |

| Grade 7 | 25 | 28 |

| Grade 8 | 23 | 26 |

| Grade 9 | 24 | 31 |

| Grade 10 | 23 | 34 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

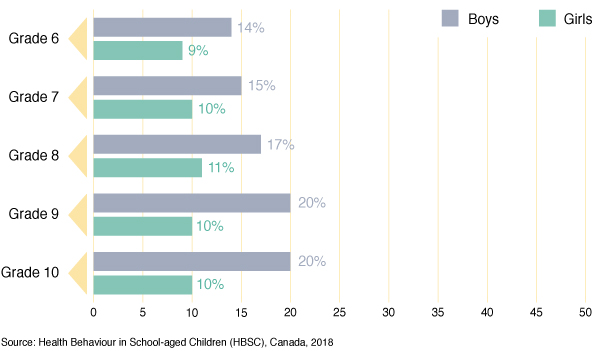

Many other young people perceive that their body is “too thin”

Among boys, the proportion that perceive their body as being “too thin” rises from 14% in grade 6 to 20% in grades 9 and 10.

Among girls, the proportion that perceive their body as being “too thin” varies from 9% to 11%.

In all grade levels, more boys than girls perceive their body as being “too thin”.

Figure 35 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 14 | 9 |

| Grade 7 | 15 | 10 |

| Grade 8 | 17 | 11 |

| Grade 9 | 20 | 10 |

| Grade 10 | 20 | 10 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

Conclusions

- Between 7% to 14% of boys, and 5% to 7% of girls, have obesity.

- Between 16% to 20% of boys, and 13% to 18% of girls, are overweight.

- Between 2002 and 2018, percentages of students with a BMI categorized as overweight and obese have not changed much in young Canadians.

- Body shaming (being teased because of their weight) is reported by 5% to 10% of young people.

- A greater percentage of girls than boys think that their body is “too fat”, whereas a greater percentage of boys than girls think that their body is “too thin”, illustrating the complex social pressure faced by young people with respect to their body image.

References

Puhl, R., & Suh, Y. (2015). Health consequences of weight stigma: implications for obesity prevention and treatment. Current obesity reports, 4(2), 182-190.

World Health Organization. (1998). Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic (Vol. [WHO/NUT/ NCD/98.1.1998]). Geneva: Report of a WHO Consultation on Obesity.

Chapter 9: Injury and concussions

- Medically treated injuries

- Serious injuries

- Where injuries happen

- Concussion

- Conclusions

Injuries

Injuries are the leading cause of death in Canadian children over the age of one (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2018). Youth injury has an enormous impact on Canadian society in terms of premature mortality, person years of life lost, inpatient and outpatient medical treatment, disability, and loss from productive activities for both youth and the adults who care for them when they are injured (Parachute, 2015). In addition, concussions have emerged as a major health issue in recent years, as awareness of their importance to the health of young people has grown.

This chapter describes how frequently young people report the occurrence of medically treated injuries. The vast majority of these are unintentional injuries, but HBSC does capture some injury events with intentional causes. It examines trends in the occurrence of more serious injuries over time, and where these more serious injuries occurred. Finally, it examines novel data on the occurrence of concussions that has not been available in past cycles of HBSC.

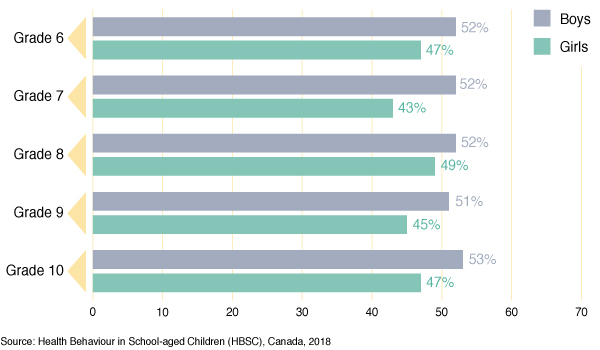

Injuries requiring medical treatment by a doctor or nurse represent a substantial burden

In boys, proportions reporting one or more medically treated injuries in the last 12 months range from 51% to 53%.

In girls, these proportions range from 43% to 49%.

Boys report injuries more often than girls in all grades.

There is no clear difference in injury prevalence reported by grade.

Boys have more contact sports options than girls, and these provide more opportunities to get injured. Most girls don’t play tackle football, rugby, or hockey; activities that are associated with a higher risk for injury.

[Youth Workshop Group Reflections]

Figure 36 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 52 | 47 |

| Grade 7 | 52 | 43 |

| Grade 8 | 52 | 49 |

| Grade 9 | 51 | 45 |

| Grade 10 | 53 | 47 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

Reports of serious injuries are stable or increasing over time

Serious injuries are those requiring a cast, stitches, an operation, or an overnight hospital stay.

Higher proportions of boys report serious injuries than girls in all grade levels.

Among girls, the proportion reporting serious injuries over time increases, while these trends are less consistent for boys.

The differences in the reporting of injury by gender are similar for all grade levels; grade 6 and 10 data are provided to illustrate these patterns.

Figure 37 - Text description

| Year | Grade 6 Boys | Grade 6 Girls | Grade 10 Boys | Grade 10 Girls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 18 | 10 | 19 | 13 |

| 2010 | 18 | 15 | 22 | 13 |

| 2014 | 19 | 16 | 22 | 14 |

| 2018 | 21 | 18 | 21 | 16 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||||

Serious injuries most commonly occur in three locations

The majority of injuries (78% of boys, 79% of girls) are experienced in one of three locations: sports facilities, schools, and homes or yards.

Children in the younger grades are more likely to experience serious injuries in home locations, while the locations for incurrence of injury for older children are much more diverse.

Figure 38 - Text description

| Location of serious injury | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Sports facilities | 34 | 31 |

| Schools | 22 | 21 |

| Home or yard | 22 | 27 |

| Streets, roads and parking lots | 5 | 4 |

| Other | 17 | 18 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

About 1 in 10 young Canadians have experienced a concussion in the past year

In boys, between 10 and 14% of students report experiencing a concussion in the past 12 months.

In girls, these proportions range from 7% to 12% across the grades.

The majority of these concussions (59.1%) occur while participating in sports.

There is no clear increase or decrease in concussion prevalence reported by grade.

It was concerning to some young people that they may report concussion-like symptoms to adults, but they may be ignored by people other than their parents. Those who had experienced concussion-like symptoms reported that their parents generally viewed them “very seriously”, but coaches and team-mates did not.

[Youth Workshop Group Reflections]

Figure 39 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 10 | 8 |

| Grade 7 | 12 | 7 |

| Grade 8 | 14 | 10 |

| Grade 9 | 14 | 10 |

| Grade 10 | 12 | 12 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

Conclusions

- Injuries happen frequently, and result in an enormous burden in terms of the costs of treatment, lost time and potential, and disability (Parachute, 2015).

- Boys consistently report the occurrence of medically treated injuries and serious injuries more often than do girls.

- Three types of locations (sports facilities, schools, and homes) are associated with 4 out of every 5 serious injuries that occur. This may provide direction for the targeting of interventions.

- About 1 in 10 Canadian youth report that they were diagnosed with a concussion in the past year, with most of these concussions occurring while participating in sports.

References

Parachute. (2015). The cost of injury in Canada. Retrieved from https://parachute.ca/en/professional-resource/cost-of-injury-report/

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2018). Facts on Injury. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/injury-prevention/facts-on-injury.html

Chapter 10: Bullying and teen dating violence

- Involvement in bullying

- Trends of the involvement in bullying

- Sexual and cyber-victimization

- Sexual and cyber-perpetration

- Physical, psychological, and cyber

teen dating victimization - Physical, psychological, and cyber teen dating perpetration

- Conclusions

Bullying and teen dating violence

Bullying is repeated and targeted aggression within a relationship in which one person has greater power than the other person. Bullying is a destructive relationship that is characterized by disrespect. Children who bully are learning to use power and aggression to control and distress others. Children who are victimized become increasingly powerless; they find themselves trapped in relationships in which they are being abused.

Teen dating violence also involves the combination of power and aggression and can take the form of physical, emotional, psychological, or cyber-violence. Although sexual violence is recognized as an important aspect of teen dating violence, it was not assessed in the HBSC study.

For both bullying and teen dating violence, there are negative long term physical and mental health effects (Wolke & Lereya, 2015).

In this chapter we examine young people’s reports of bullying and teen dating violence, two forms of an abuse of power within peer relationships.

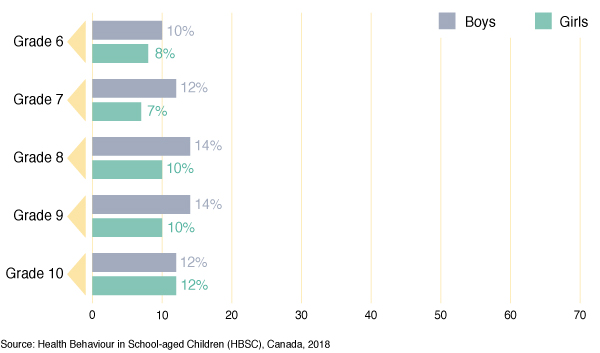

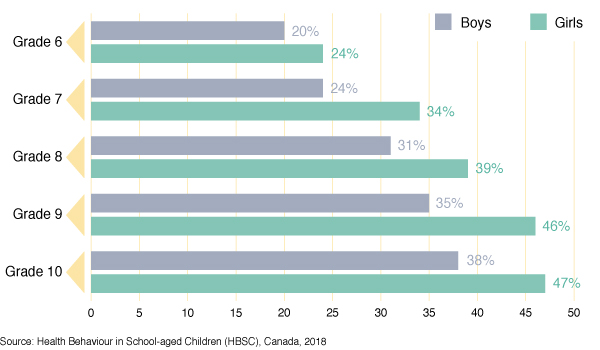

Approximately one in three girls report being bullied

In general, more girls report being bullied than boys at all grades. For example, 25% of boys in grade 6 report being bullied compared to 31% of girls.

For both boys and girls the lowest percentages of students who report being bullied are in grade 10, 22% of boys and 26% of girls.

Figure 40 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 25 | 31 |

| Grade 7 | 30 | 31 |

| Grade 8 | 27 | 30 |

| Grade 9 | 27 | 29 |

| Grade 10 | 22 | 26 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC),

Canada, 2018. In the HBSC international report, the percentage of students being bullied and bullying others are each based on a single question. In Canada, a more comprehensive method is used: the percentage of students being bullied and bullying others are each based on six questions that measure frequency on specific types of bullying behaviours, in addition to the question used in the international report. The international approach results in lower percentages compared to the approach used in this report. |

||

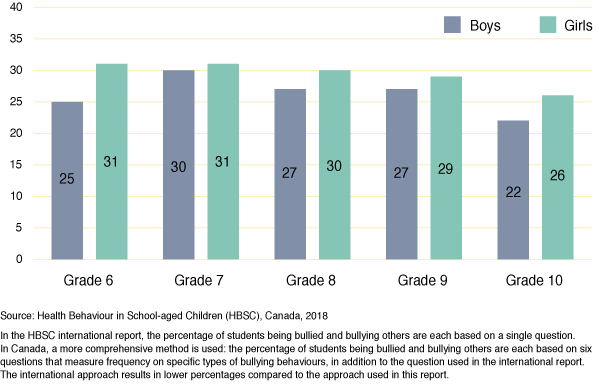

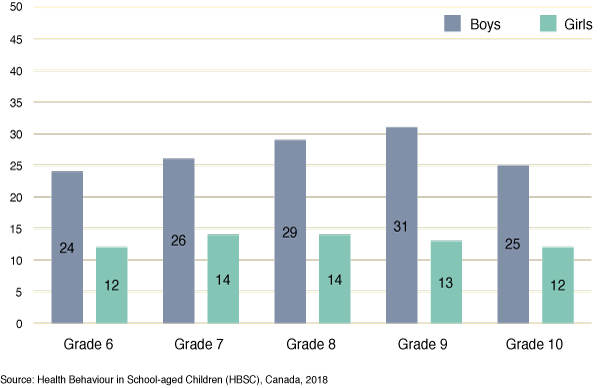

More boys than girls report bullying others

In all grades, more boys than girls report bullying others. For example, 15% of boys in grade 6 report bullying others compared to 10% of girls.

For boys, the percentage of students who report bullying others increases from grade 6 to grade 10, from 15% to 23%.

Some young people were surprised by the statistics. They thought that bullying rates would be higher than reported and questioned whether students might not be candid in answering whether they had bullied others or had been bullied.

[Youth Workshop Group Reflections]

Figure 41 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 15 | 10 |

| Grade 7 | 15 | 10 |

| Grade 8 | 21 | 12 |

| Grade 9 | 20 | 10 |

| Grade 10 | 23 | 11 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

More boys than girls report bullying others and being bullied

More boys than girls report both bullying others and being bullied in grades 7 through 10. For example, 12% of boys in grade 8 report both behaviours versus 7% of girls.

In general, the percentages of students who report bullying others and being bullied is fairly consistent across the grades for both boys and girls. The lone exception is the lower percentage for grade 6 boys compared to the older grades.

Figure 42 - Text description

| Grade | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 6 | 8 | 7 |

| Grade 7 | 10 | 6 |

| Grade 8 | 12 | 7 |

| Grade 9 | 12 | 6 |

| Grade 10 | 11 | 6 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||

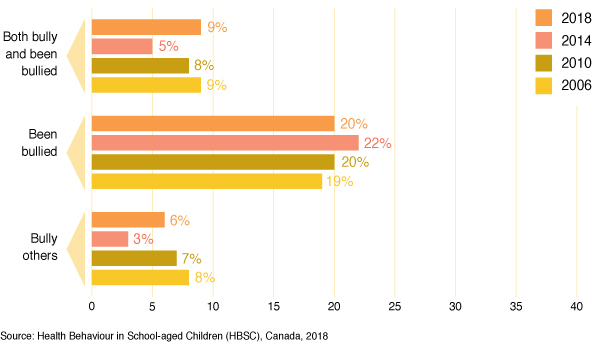

Percentages of students who report being bullied and bullying others are relatively stable over time

The percentages of students who report being bullied, bullying others and being both victims and bullies have been relatively stable over the past 12 years. The notable exception is lower percentages of both bullying perpetration and being both a bully and a victim were lower in 2014 compared to 2018.

A lot of young people felt that bullying will likely never go away because it’s an evolving problem and cyber-bullying is hard to catch and address.

[Youth Workshop Group Reflections]

Figure 43 - Text description

| Involvement in bullying | 2018 | 2014 | 2010 | 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both bully and been bullied | 9 | 5 | 8 | 9 |

| Been bullied | 20 | 22 | 20 | 19 |

| Bully others | 6 | 3 | 7 | 8 |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||||

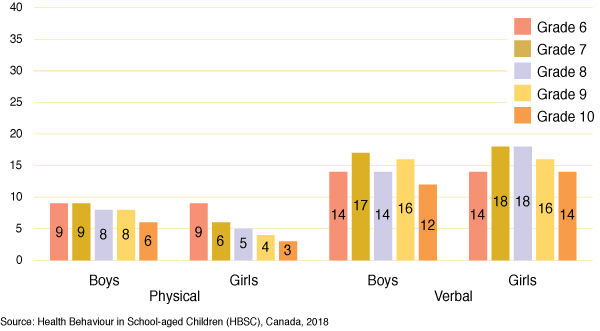

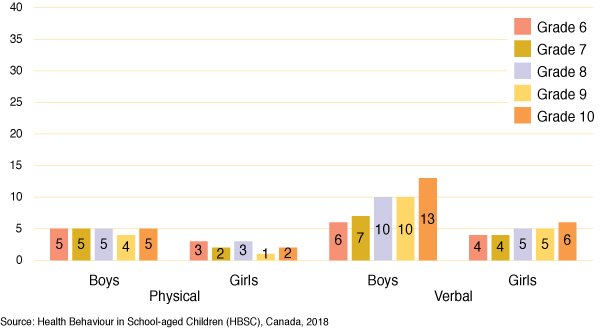

Verbal bullying is more often reported than physical bullying

More boys than girls report being bullied physically with the exception of grade 6.

9% of boys in grade 6 and 9% of girls in grade 6 report being bullied physically.

Similar percentages of boys and girls report being verbally bullied.

12% of boys and 14% of girls report being verbally bullied in grade 10.

Figure 44 - Text description

| Physical and verbal bullying, by gender | Grade 6 | Grade 7 | Grade 8 | Grade 9 | Grade 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Boys | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 6 |

| Girls | 9 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | |

| Verbal | Boys | 14 | 17 | 14 | 16 | 12 |

| Girls | 14 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 14 | |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||||||

More boys than girls report bullying others physically and verbally

With increasing grade, more boys report verbally bullying others.

For example, 6% of grade 6 boys report verbally bullying others versus 13% of grade 10 boys.

Figure 45 - Text description

| Physical and verbal bullying, by gender | Grade 6 | Grade 7 | Grade 8 | Grade 9 | Grade 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Boys | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Girls | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Verbal | Boys | 6 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 13 |

| Girls | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||||||

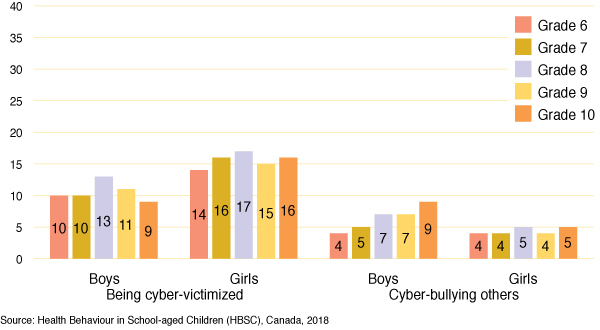

Girls are more likely to report being cyber-victimized and boys are more likely to report cyber-bullying others

“[Cyber-bullying is a] lot more scary because people are more likely to say stuff over social media than to your face; ‘keyboard warriors’.”

[Youth Workshop Participant]

Girls are more likely to report being cyber-victimized than boys.

For example, 16% of girls in grade 10 and 9% of boys in grade 10 report being cyber-victimized.

With increasing grade, more boys report cyber-bullying others than girls.

9% of boys and 5% of girls report cyber-bullying others in grade 10.

Young people commented on the effects of cyber-bullying and how easy it is to bully people online because of the anonymity and being removed from the situation. They felt like this was something that is going to continue to increase over time.

[Youth Workshop Group Reflections]

Figure 46 - Text description

| Being cyber-victimized and cyber-bulleying others, by gender | Grade 6 | Grade 7 | Grade 8 | Grade 9 | Grade 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Being cyber-victimized | Boys | 10 | 10 | 13 | 11 | 9 |

| Girls | 14 | 16 | 17 | 15 | 16 | |

| Cyber-bullying others | Boys | 4 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 9 |

| Girls | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | ||||||

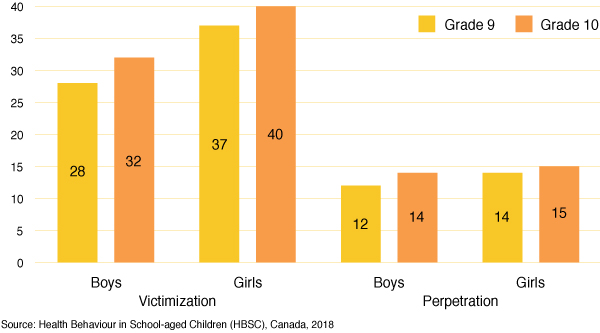

Girls report more dating violence victimization than boys

A high proportion of students in grades 9 and 10 report being victimized in their dating relationships, versus significantly fewer reporting perpetrating the dating violence.

40% of grade 10 girls compared to 32% of grade 10 boys.

Boys and girls are equally likely to report perpetrating dating violence, 14% of grade 9 girls and 12% of grade 9 boys.

Figure 47 - Text description

| Victimization and perpetration, by gender | Grade 9 | Grade 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Victimization | Boys | 28 | 32 |

| Girls | 37 | 40 | |

| Perpetration | Boys | 12 | 14 |

| Girls | 14 | 15 | |

| Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), Canada, 2018 | |||

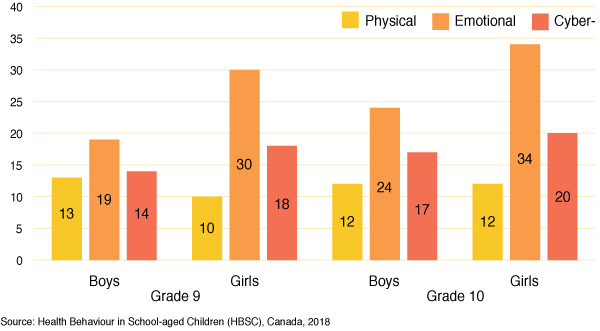

Girls are more likely to report emotional and cyber-victimization than boys in teen dating relationships

A greater percentage of students reported cyber- and emotional victimization than physical victimization in teen dating relationships.

For example, 19% of boys in grade 9 and 34% of girls in grade 10 report emotional teen dating violence victimization.

17% of boys and 20% of girls report being cyber-victimized by their dating partner in grade 10.

Figure 48 - Text description

| Grade, gender | Physical | Emotional | Cyber- | |

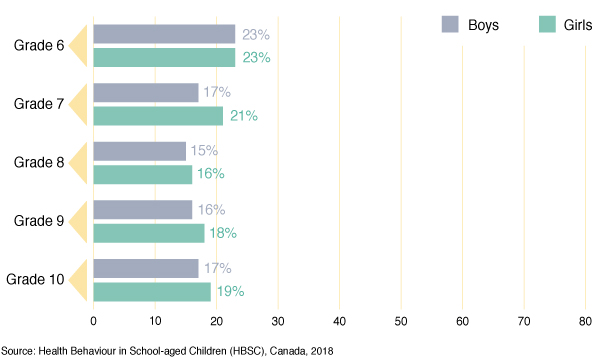

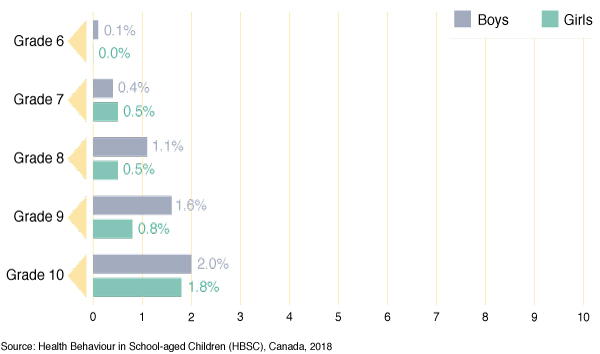

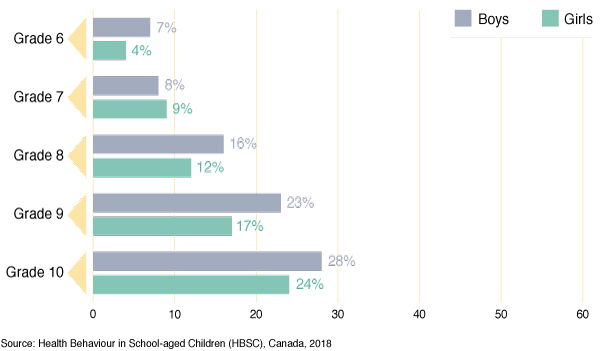

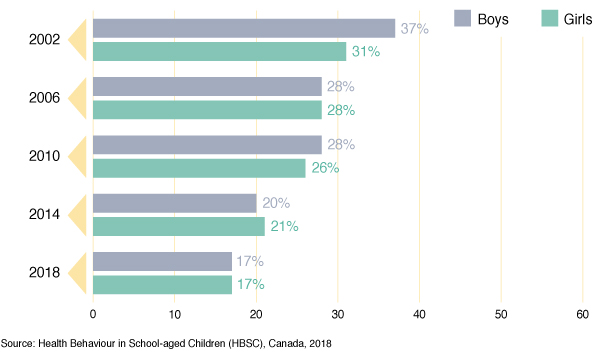

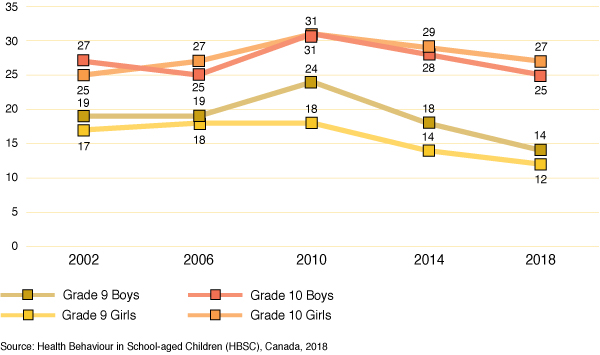

|---|---|---|---|---|