Interim guidance on the use of Imvamune® in the context of a routine immunization program

Download in PDF format

(816 KB, 29 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: 2024-05-24

Cat.: HP40-362/1-2024E-PDF

ISSN: 978-0-660-71252-9

Pub.: 240036

On this page

- Preamble

- Summary of information

- Background

- Methods

- Epidemiology

- Vaccine

- Ethics, equity, feasibility and acceptability considerations

- Economics

- Recommendations

- Research priorities

- Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Appendix A: Vaccine effectiveness studies

- References

Preamble

The National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) is an External Advisory Body that provides the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) with independent, ongoing and timely medical, scientific, and public health advice in response to questions from PHAC relating to immunization.

In addition to burden of disease and vaccine characteristics, PHAC has expanded the mandate of NACI to include the systematic consideration of programmatic factors in developing evidence-based recommendations to facilitate timely decision-making for publicly funded vaccine programs at provincial and territorial levels.

The additional factors to be systematically considered by NACI include: economics, ethics, equity, feasibility, and acceptability. Not all NACI statements will require in-depth analyses of all programmatic factors. While systematic consideration of programmatic factors will be conducted using evidence-informed tools to identify distinct issues that could impact decision-making for recommendation development, only distinct issues identified as being specific to the vaccine or vaccine-preventable disease will be included.

This statement contains NACI's independent advice and recommendations, which are based upon the best current available scientific knowledge. This document is being disseminated for information purposes. People administering the vaccine should also be aware of the contents of the relevant product monograph. Recommendations for use and other information set out herein may differ from that set out in the product monographs of the Canadian manufacturers of the vaccines. Manufacturer(s) have sought approval of the vaccines and provided evidence as to its safety and efficacy only when it is used in accordance with the product monographs. NACI members and liaison members conduct themselves within the context of PHAC's Policy on Conflict of Interest, including yearly declaration of potential conflict of interest.

Summary of information

The following highlights key information for immunization providers. Please refer to the remainder of the Statement for details.

What

- Mpox disease: Mpox is caused by the monkeypox virus (MPXV), a mammalian Orthopoxvirus related to the vaccinia, cowpox, as well as variola (smallpox) viruses. Clinical presentation includes pox-like lesions, often in oral and/or anogenital regions, fever, body aches, back pain, and swollen lymph nodes. Since 2022, mpox has been reported across multiple countries previously non-endemic to MPXV including Canada. For more information on mpox in Canada, please visit Mpox (monkeypox).

- Imvamune® vaccine: Imvamune® is a non-replicating, third-generation smallpox vaccine manufactured by Bavarian Nordic, authorized in Canada for active immunization against smallpox, mpox, and related Orthopoxvirus infections and disease in adults 18 years of age and older determined to be at high risk for mpox exposure. Evidence on Imvamune®vaccine effectiveness (VE) against mpox continues to accumulate; numerous observational studies initiated during active mpox outbreaks since 2022 are reporting high VE against symptomatic mpox. Available clinical and post-marketing safety surveillance data on Imvamune® demonstrates that the vaccine is well-tolerated. The most common adverse events (AEs) reported by adults following 1 and/or 2 doses were non-serious injection-site (e.g., swelling, pain) and systemic (e.g., fatigue, headache) reactions.

Who

NACI makes the following recommendations for public health program and individual decision making:

- Individuals at high risk of mpox should receive two doses of Imvamune® administered at least 28 days (4 weeks) apart.

- Imvamune® vaccination can be given concurrently (i.e., same day) or at any time before or after other live or non-live vaccines.

- Doses should be administered via subcutaneous injection. Dose sparing strategies involving intradermal administration are not recommended in the context of routine immunization.

- Those who have started a primary series with Imvamune®, in whom more than 28 days have passed without receipt of the second dose, should receive the second dose regardless of time since the first dose.

- Those who have previously received smallpox vaccination (e.g., previous generation live-replicating vaccine) and are recommended to receive Imvamune® based on risk factors for mpox should also receive a 2-dose series with a minimum interval of 28 days.

- NACI guidance on the use of Imvamune® in the context of a routine immunization program should be considered interim, and will be re-evaluated once additional evidence emerges. Vaccine eligibility based on increased risk for mpox should be informed by available clinical evidence and ongoing epidemiology. Risk factors may change over time and should be assessed by local and/or provincial/territorial public health.

- At this time, individuals considered at high risk of mpox in Canada include:

- Men who have sex with men (MSM) who meet one or more of the following criteria:

- have more than one partner

- are in a relationship where at least one of the partners has other sexual partners

- have had a confirmed sexually transmitted infection acquired in the last year

- have engaged in sexual contact in sex-on-premises venues.

- Sexual partners of individuals who meet the criteria above.

- Sex workers (regardless of gender, sex assigned at birth, or sexual orientation).

- Staff or volunteers in sex-on-premises venues where workers may have contact with fomites potentially contaminated with mpox.

- Those who engage in sex tourism (regardless of gender, sex assigned at birth, or sexual orientation).

- Individuals who anticipate experiencing any of the above scenarios.

- Men who have sex with men (MSM) who meet one or more of the following criteria:

- NACI continues to recommend the use of Imvamune® as a post-exposure vaccination (also known and referred to as post-exposure prophylaxis) to individuals who have had high risk exposure(s) to a probable or confirmed case of mpox, or within a setting where transmission is happening, if they have not received both doses of pre-exposure vaccination.

- A post-exposure vaccine dose should be offered as soon as possible, preferably within 4 days of last exposure, but can be considered up to 14 days from last exposure.

- After 28 days, a second dose should be offered if MPVX infection did not develop, regardless of ongoing exposure status.

- Individuals with previous or active MPXV infection should not be offered Imvamune®

- Off-label use in pediatric populations is recommended for those meeting the criteria for post-exposure vaccination, and may be offered at their clinician's discretion.

- Imvamune® vaccination can be given concurrently (i.e., same day) or at any time before or after other live or non-live vaccines.

MSM: Man or Two-Spirit identifying individual who has sex with another person who identifies as a man, including but not limited to individuals who self-identify as trans-gender, cis-gender, Two-Spirit, gender-queer, intersex, and non-binary.

Why

- While the incidence of mpox in Canada has significantly declined since the fall of 2022, mpox remains an important public health concern with the potential for future resurgence.

- After NACI provided guidance for Imvamune® pre-exposure vaccination, most Canadian jurisdictions offered the vaccine to populations/groups consistent with NACI guidance. Across Canada, individuals self-identifying as gay, bisexual, or other men who have sex with men (gbMSM) who are considered at high risk of mpox exposure (e.g., multiple sex partners, recent sexually transmitted infection; STI) are eligible for Imvamune® pre-exposure vaccination; however, specified risk factors and eligibility for other groups (e.g., sex workers) varies by jurisdiction.

- Up to December 10, 2023, approximately 143,471 vaccine doses were administered in Canada, primarily in Ontario (n=52,747), Quebec (n=46,870), and British Columbia (n=30,168). Specifically, 103,572 people were vaccinated against mpox with at least one dose of Imvamune® in response to this outbreak, while 39,631 people were vaccinated with two dosesFootnote 1.

- Due to evolving mpox epidemiology in Canada and emerging evidence on VE of Imvamune®, Canadian provinces and territories, as well as several stakeholders, have indicated the need for national guidance on pre-exposure vaccination outside the context of an ongoing mpox outbreak. This included identification of priority populations for pre-exposure vaccination and guidance on a recommended vaccine schedule in the context of a focused routine immunization program.

Background

Mpox disease

Mpox is caused by the monkeypox virus (MPXV), a mammalian Orthopoxvirus related to the vaccinia, cowpox, as well as variola (smallpox) viruses. MPXV is endemic in multiple regions of Central and West AfricaFootnote 2. Prior to the multi-country outbreak in 2022, mpox was considered a rare zoonotic disease. It is transmitted through contact with bodily fluids, lesions on the skin or internal mucosal surfaces (e.g., mouth, throat, anogenital region), contaminated objects, and respiratory droplets. MPXV is subclassified into two clades: clade I and clade II (formerly the Central African and West African clades, respectively), with the former being associated with greater disease severityFootnote 3. Clade II has two subclades, of which clade IIb was responsible for the 2022 global outbreakFootnote 4.

Mpox is typically a mild and self-limiting disease, with most infected individuals recovering within two to four weeks. Symptoms appear within seven to 21 days after exposure and include rash, fever, body aches, back pain, and swollen lymph nodes. Clinical presentation in the 2022 outbreak often included oral and/or anogenital lesions, as well as lesions on the face, mouth, throat, palms of hands, and soles of feet. Potential complications of mpox include skin infections, pneumonia, sepsis, pain or difficulty swallowing, vision loss, encephalitis, myocarditis, and deathFootnote 5. During the 2022 mpox outbreak, reports indicate that individuals with uncontrolled human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection are at higher risk of severe diseaseFootnote 6Footnote 7Footnote 8. Young children, pregnant women and pregnant individuals, and immunocompromised individuals are also at higher risk of severe disease with mpoxFootnote 5

History of vaccines for mpox in Canada: Previous NACI guidance and provincial/territorial immunization programs

Imvamune® (Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic [MVA-BN]) is available in all provinces and territories across Canada. NACI first issued guidance on the use of Imvamune® on June 10, 2022, in the context of a rapidly evolving mpox outbreak among countries previously non-endemic for mpox. NACI provided initial interim recommendations on Imvamune® for post-exposure vaccination against mpox, as well as guidance for personnel working with replicating Orthopoxviruses in research laboratory settingsFootnote 9Footnote 10. NACI subsequently updated guidance on the use of Imvamune® on September 23, 2022, recommending pre-exposure vaccination against mpoxFootnote 11. At that time, NACI recommended immunization of individuals at highest risk of mpox based on epidemiological data and specific factors that may increase risk (e.g., MSM, as defined in the statement summary, who meet high-risk criteria, sex workers, individuals working in sex-on-premises venues).

While the incidence of mpox in Canada has significantly declined since the fall of 2022, mpox remains an important public health concern with the potential for future resurgence. After NACI provided guidance for Imvamune® pre-exposure vaccination, most Canadian jurisdictions offered the vaccine to populations/groups consistent with this guidance. Across Canada, individuals self-identifying as gbMSM who are considered at high risk of mpox exposure (e.g., multiple sex partners, recent STI) are eligible for Imvamune® pre-exposure vaccination; however, specified risk factors and eligibility for other groups (e.g., sex workers) varies by jurisdiction. Up to December 10, 2023, approximately 143,471 vaccine doses were administered in Canada, primarily in Ontario (n=52,747), Quebec (n=46,870), and British Columbia (n=30,168). Specifically, 103,572 people were vaccinated with at least one dose, while 39,631 people were vaccinated with two doses of Imvamune®Footnote 1

Due to evolving mpox epidemiology in Canada and emerging evidence on vaccine effectiveness of Imvamune®, Canadian provinces and territories, as well as several stakeholders, have indicated the need for national guidance on pre-exposure vaccination outside the context of an ongoing mpox outbreak. This included identification of priority populations for pre-exposure vaccination and guidance on a recommended vaccine schedule in the context of a focused routine immunization program.

Objective

The objective of this NACI statement was to review the available evidence and provide interim guidance on the use of Imvamune® to prevent mpox in the context of a focused interim routine immunization program for populations at high risk.

Methods

In brief, the broad stages in the preparation of this statement on interim NACI guidance are:

- Analysis of the burden of mpox disease in Canada and worldwide since the 2022 multi-country outbreak.

- Knowledge synthesis (retrieval and summary of individual studies, assessment of the quality of the evidence from individual studies on VE using Cochrane 2.0 or ROBINS-I methodology– summarized in vaccine effectiveness figures)

- Synthesis of the body of evidence of benefits and harms, considering the quality of the synthesized evidence and magnitude of effects observed across studies.

- Use of a published, peer-reviewed framework and evidence-informed tools to ensure that issues related to ethics, equity, feasibility, and acceptability (EEFA) are systematically assessed and integrated into the guidance.

- Economic evaluation: While an economic evaluation on a routine Imvamune® immunization program in Canada was not conducted, this guidance is considered interim and will be reassessed when more evidence is available. Cost-effectiveness analyses may be considered in the future.

- Translation of evidence and programmatic considerations into recommendations, leveraging a NACI Evidence-to-Decision framework.

For more information, see the following:

- Evidence-based recommendations for immunization: Methods of the National Advisory Committee on Immunization

A framework has been developed to facilitate systematic consideration of programmatic factors (now included in NACI's mandate, including ethics, equity, feasibility, acceptability) in developing clear, evidence-based recommendations for timely, transparent decision-makingFootnote 12.This framework provides a clear outline with accompanying evidence-informed tools to consider relevant aspects of each programmatic factor that may have an impact on the implementation of NACI recommendations. This framework has been integrated into the statement.

For this interim guidance, NACI reviewed key questions as proposed by the NACI mpox Working Group (WG), including on the burden of disease to be prevented and the population(s) with greatest disease burden, vaccine safety, vaccine efficacy/effectiveness, vaccine supply, and other aspects of the overall immunization strategy. Knowledge synthesis was performed by the NACI Secretariat and supervised by the NACI mpox WG. Following critical appraisal of individual studies, summary tables with ratings of risk of bias informed by Cochrane 2.0 and ROBINS-I, as appropriate, were prepared (see Appendix). The NACI Secretariat provided the NACI mpox WG an assessment of the body of evidence using an Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework, and proposed recommendations for WG input.

NACI considered feedback obtained during 2022 deliberations from stakeholder groups representing the communities and groups considered at high risk of mpox exposure. Input was also provided by the Public Health Ethics Consultative Group (PHECG) during a 2022 consultation, the Canadian Immunization Committee (CIC; August 2023), and PHAC. Guidance on the use of Imvamune® in the context of international travel was developed in collaboration with the Canadian Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT). The description of relevant considerations, rationale for specific decisions, and knowledge gaps are described. NACI reviewed the available evidence and approved updated guidance on March 26, 2024.

The policy questions addressed in this statement are:

- Considering previous, current, and projected epidemiology, what populations/groups should be recommended to routinely receive Imvamune® for the prevention of mpox?

- In the setting of a sustained sufficient vaccine supply, what is the recommended schedule for Imvamune® for the prevention of mpox, including primary series and additional doses?

- Do recommendations (including vaccine use/schedule) differ based on clinical considerations (e.g., immunocompromised, history of mpox) or previous smallpox vaccination history?

Epidemiology

Burden of mpox in Canada

In 2022, during the beginning of a multi-country outbreak, the first case in Canada was reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) on May 19, 2022, during the beginning of a multi-country outbreak among previously non-endemic regions. Between May 19, 2022, and December 31, 2023, a total of 1,541 cases (1,465 confirmed and 76 probable), 46 hospitalizations, and no deaths have been reported across 9 provinces and 1 territory. The highest case numbers are in Ontario (n=737), Quebec (n=531), and British Columbia (n=213). Consistent with global trends, mpox cases in Canada have been reported primarily among gbMSM (96%; median age: 36 years), with sexual contact as the predominantly reported mode of transmissionFootnote 13. Based on available data from May 19, 2022 to December 31, 2023, a small percentage of cases reported possible non-sexual exposure including person-to-person transmission via respiratory secretions, household contact with a known or suspected case, occupational exposure, large gatherings and shared drug equipment. Of the total mpox cases in Canada with available information on HIV status (884 cases of a total of 1541 cases; as of December 31, 2023), 30% were among individuals living with HIV. There are no reports of hospital acquired mpox (i.e., no reports of nosocomial transmission) in Canada. As of December 31, 2023, there have been 92 mpox cases among healthcare workers in Canada (85 confirmed; 7 probable). Based on available information, cases among healthcare workers were likely acquired through sexual contact. Since the peak of the outbreak in 2022, mpox cases have declined significantly. Between January 1 and December 31, 2023, 70 confirmed mpox cases have been reported in CanadaFootnote 1.

Global burden of mpox since the start of the 2022 multi-country outbreak

Global mpox incidence has decreased considerably in 2023 compared to 2022Footnote 14. However, higher numbers of mpox cases were reported in southeast Asia and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC; clade I-specific outbreak) in 2023, and the Americas and Europe have recently reported an increase in mpox casesFootnote 14Footnote 15. Between January 1, 2022, and December 31, 2023, 93,030 confirmed cases, 652 probable cases, and 176 deaths were reported in 117 countries across all six WHO regions. Among countries previously non-endemic for the disease prior to 2022, including Canada, mpox has been primarily transmitted via sexual encounters (83.2%) and among men who have sex with men (85.3%). The majority of cases were in males (96.4%) aged 18-44 years (79.4%), with a median age of 34 years. Non-sexual exposure settings included household contacts, large events/parties, tattoo parlours, and the workplace Footnote 14Footnote 16. Among cases with known HIV status, 52.1% were living with HIV. Approximately 4.1% of cases reported to the WHO were in health workers, most of whom were exposed in community settings (i.e., non-healthcare exposures)Footnote 14. Although data on mpox among sex workers has been limited, 35 mpox cases were reported among cisgender and transgender women and non-binary individuals assigned female sex at birth in the context of a multi-national case series (136 confirmed mpox cases among 15 countries, cases reported between May 11, 2022 and October 4, 2022)Footnote 17.

MPXV clades currently circulating in Europe, the U.S., and Canada belong to clade II, specifically subclade IIb, which is associated with milder illness than clade I. Historically, clade I infections were not known to be associated with transmission through sexual contact. However, in March 2023, a cluster of sexually transmitted clade I mpox cases was confirmed in the DRC. The primary case-patient was a man from the DRC who reported having multiple sexual encounters in both Europe and the DRC, which led to an additional five PCR-positive MPXV cases. This finding shows that mpox transmission through sexual contact extends beyond clade IIb and highlights the need for more routine screening in mpox-endemic and non-endemic regionsFootnote 18.

Clinical presentation of mpox

The most frequently reported symptoms of mpox include rash (any rash- 89.8%, generalized rash- 54.7%, genital rash- 49.4%), fever (58.4%), lymphadenopathy (29.8%), and headache (29.2%)Footnote 14. Genital rash is much more common among cases since 2022 (e.g., clade IIb; predominant source of transmission via sexual encounter) compared to cases in areas endemic to mpox (e.g., clade I or clade II). Asymptomatic cases have been described, although rare (0.7% of total cases) (WHO, 2023)Footnote 14. While most people who contract mpox experience only mild symptoms, some progress to severe disease. Available evidence suggests that unvaccinated individuals who have uncontrolled HIV infection are at greater risk for severe infection, hospitalization, and deathFootnote 6Footnote 7Footnote 8.

Vaccine

Preparation(s) authorized for use in Canada

Imvamune® (also called MVA-BN, Jynneos®, Imvanex®) is a non-replicating, third-generation smallpox vaccine manufactured by Bavarian Nordic. Imvamune® was initially authorized for use in Canada on November 21, 2013, as an Extraordinary Use New Drug Submission (EUNDS) for emergency use by the government for active immunization against smallpox infection and disease in persons 18 years of age and older who have a contraindication to first- or second-generation smallpox vaccines. Imvamune® was subsequently approved under a supplement to the EUNDS on November 5, 2020, for active immunization against smallpox, mpox, and related Orthopoxvirus infections and diseases in adults 18 years of age and older determined to be at high risk for exposure.

Additional information on Imvamune is contained within the product monograph available through Health Canada's Drug product database.

| Product brand name and formulation | Imvamune®(smallpox and mpox vaccine) |

|---|---|

| Type of vaccine | Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic® (MVA-BN) (live-attenuated, non-replicating) |

| Date of authorization in Canada | Date of Initial Approval: November 21, 2013 Date of Authorization for Mpox as Expanded Indication: November 5, 2020 Date of Latest Revision: August 3, 2023 |

| Authorized ages for use | Adults 18 years of age and older determined to be at high risk of exposure |

| Dose | Each dose is 0.5 mL (at least 0.5 x 108 Infectious Units MVA-BN) |

| Route of administration | Subcutaneous injection |

| Recommended scheduleFootnote a for primary series | Two doses, administered at least 28 days apart |

| Non-Medical Ingredients | TromethamineFootnote b (trometamol, tris) Sodium chloride Water for injection Hydrochloric acid Traces of:

|

| Adjuvant / Preservatives | The vaccine contains no adjuvants or preservatives |

|

|

Efficacy/effectiveness of Imvamune® pre-exposure vaccination against mpox

NACI reviewed available evidence on efficacy/effectiveness and safety of Imvamune® as pre-exposure vaccination for the prevention of mpox leveraging an evergreen PHAC database of published and pre-print studies related to Imvamune® and mpox. Study details can be found in Appendix A.

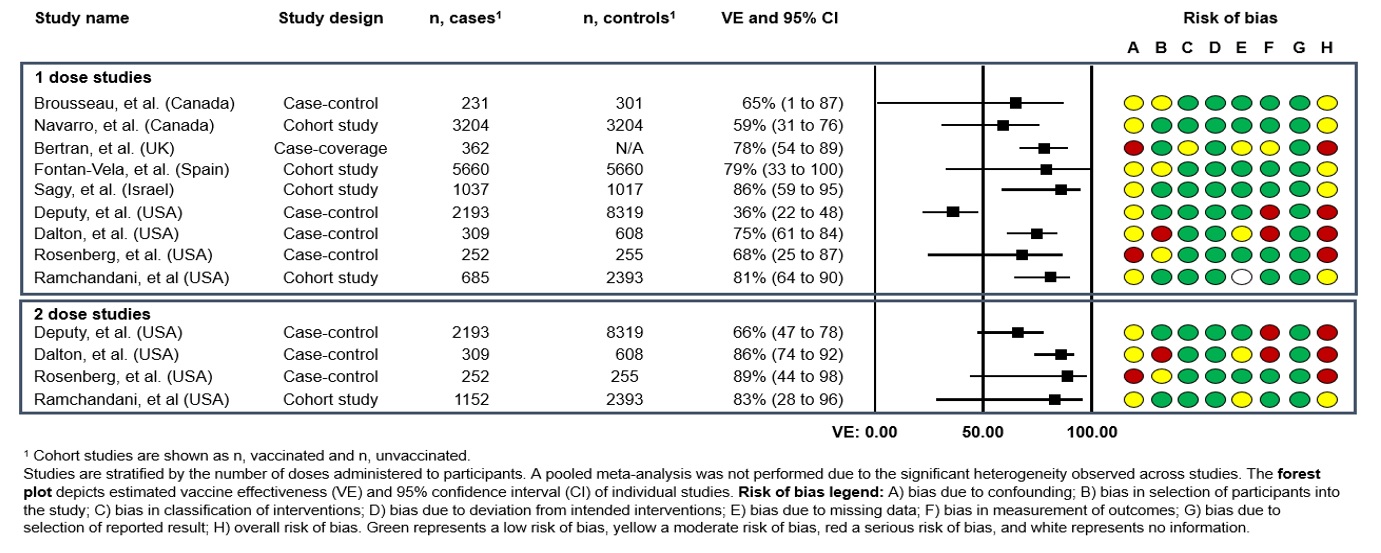

Any published or pre-print study reporting efficacy/effectiveness of one or more doses of Imvamune® for the pre-exposure prevention of mpox and mpox-associated disease was included in the analysis. Available evidence was limited to real-world vaccine effectiveness (VE) observational studies. To date, 10 studies have reported estimates of the effect of a single dose of Imvamune® against mpox infection, five of which also evaluated the effect of a 2-dose series. One-dose VE ranged from 36% (95% confidence intervals [CI]: 22 to 47%] to 86% (95% CI: 59 to 95%), while 2-dose VE ranged from 66% (95% CI: 47 to 78%) to 89% (95% CI: 44 to 98%). All individual studies evaluated are summarized below (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Of note, evidence should be interpreted with caution, as studies were assessed to be at a serious risk of bias (largely due to concerns regarding confounding and the measurement of outcomes) or at a moderate risk of bias (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Effectiveness against mpox infection

Two Canadian studies reported 1-dose VE against symptomatic mpox infection (Figure 1):

- A test-negative case-control study from Quebec used administrative/surveillance data collected via a self-reported questionnaire. The study period was June 19 to September 24, 2022, and included men ≥18 years of age with no history of mpox infection. In total, 532 men were included in the study (231 cases and 301 controls). After adjusting for age, calendar-time, and more detailed indicators of exposure risk determined from the questionnaire, 1-dose VE was estimated to be 65% (95% CI: 1 to 87%). Adjusted VE (aVE) using administrative data only was lower at 35% (95% CI: - 2 to 59%)Footnote 19.

- In a study from Ontario that took place from June 12 to November 26, 2022, linked administrative data was used in a target trial emulation to estimate 1-dose VE in men 18 years of age and older. In a sample of 3,204 vaccinated men who were matched 1:1 to unvaccinated men with a similar risk profile, 1-dose VE was estimated to be 59% (95% CI: 31 to 76%)Footnote 20.

- In both Canadian studies, individuals were classified as vaccinated if it had been at least 14 days since their first dose. No estimates of 2-dose VE were reported by Canadian studies, and neither were estimates of VE (any dose) specifically for individuals considered immunocompromised.

- Additional observational studies from the United Kingdom (UK), Spain, and Israel also provided estimates of 1-dose VE of Imvamune® against mpox infection in males. All three studies reported similar estimates of VE, ranging from 78% (95% CI: 54 to 89%) to 86% (95% CI: 59 to 95%)Footnote 21Footnote 22Footnote 23

- Three case-control studies and one retrospective cohort study from the United States (US) provided estimates of 1- and 2-dose VE against mpox infection (Figure 1):

- In the largest study (n=360 individuals receiving two doses of Jynneos®), nationwide health records were used to estimate 1- and 2-dose VE against medically attended mpox disease among adults 18 years of age and older between August and November 2022. Cases were matched with up to four controls who had either a new HIV diagnosis or new or refill order for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). After adjusting for several potential confounding variables, the aVE of a single dose was estimated to be 36% (95% CI: 22 to 47%), while the aVE of the complete 2-dose schedule was estimated to be 66% (95% CI: 47 to 78%). One- and 2-dose VE among immunocompetent individuals was 41% (95% CI: 25 to 53%) and 76% (95% CI: 58 to 87%), respectively. However, VE among immunocompromised individuals was not able to be estimated due to low vaccine coverageFootnote 24.

- Higher VE estimates were obtained in another US case-control study, conducted between August 2022 to March 2023 (n=206 individuals receiving two doses of Jynneos®). Participants were 18 to 49 years of age who were sexually active and identified as MSM or transgender. Cases were matched with up to four controls who had recently visited a sexual health, HIV care, or HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) clinic. Here, 1- and 2-dose aVE was estimated at 75% (95% CI: 61 to 84%) and 86% (95% CI: 74 to 92%), respectively. This study also provided estimates of aVE stratified by immunocompromised status, with 1- and 2-dose aVE in immunocompromised individuals being estimated at 51% (95% CI: -28 to 81%) and 70% (95% CI: -38 to 94%), respectivelyFootnote 25.

- A third US case-control study that used systematic surveillance reporting was conducted in New York between July and October 2022 among men ≥18 years of age. This study used contemporaneous controls who were men diagnosed with rectal gonorrhea or primary syphilis and had a presumed history of sexual contact with a male or transgender person. The results from this study (n=21 individuals receiving two doses of Jynneos®) were similar to the other US studies, with 1- and 2-dose aVE being estimated at 68% (95% CI: 25 to 87%) and 89% (95% CI: 44 to 98%), respectivelyFootnote 26.

- In a retrospective cohort study from Seattle, electronic health record data was used to estimate 1- and 2-dose VE among all men who have sex with men, who had at least one health clinic visit between January 2020 and December 2022 (n=4,230). Results were consistent with estimates from other studies, with aVE estimates of 81% (95% CI: 64 to 90%) and 83% (28 to 96%) for one and two doses, respectivelyFootnote 27.

- Consistent with the VE data observed for 1- and 2-dose schedules, a recent observational study from the US found considerably higher antibody titers after two doses compared to a single dose of Jynneos®, in those without prior smallpox vaccination, measured at a median of 33 days after dose 1 and 21 days after dose 2. This study also reported similar antibody titers after a 2-dose series in those with no previous smallpox vaccination, regardless of HIV infection status, measured at approximately 2.5 to 3 months following the second vaccine doseFootnote 28. However it should be noted that other studies have not shown a correlation between VE and immunogenicity and the correlate of protection for the Imvamune vaccine remains unknown.

Figure 1: Descriptive text

Studies are stratified by the number of doses administered to participants. A pooled meta-analysis was not performed due to the significant heterogeneity observed across studies.

Forest plot depicts estimated vaccine effectiveness (VE) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of individual studies.

This figure consists of a table summarizing the study characteristics for studies reporting on vaccine effectiveness against mpox as well as a graphic depicting the vaccine effectiveness in a forest plot and a graphic depicting the risk of bias for each study.

| Study name | Study design | N, casesFootnote a | N, controlsFootnote a | VE and 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brousseau, et al. (Canada) | Case-control | 213 | 301301 | 65% (1 to 87) |

| Navarro, et al. (Canada) | Cohort study | 3204 | 3204 | 59% (31 to 76) |

| Bertran, et al. (UK) | Case-coverage | 362 | N/A | 78% (54 to 89) |

| Fontan-Vela, et al. (Spain) | Cohort study | 5660 | 5660 | 79% (33 to 100) |

| Sagy, et al. (Israel) | Cohort study | 1037 | 1017 | 86% (59 to 95) |

| Deputy, et al. (USA) | Case-control | 2193 | 8319 | 36% (22 to 48) |

| Dalton, et al. (USA) | Case-control | 309 | 608 | 75% (61 to 84) |

| Rosenberg, et al. (USA) | Case-control | 252 | 255 | 68% (25 to 87) |

| Ramchandani, et al (USA) | Cohort study | 685 | 2393 | 81% (64 to 90) |

|

||||

| Study name | Study design | N, casesFootnote a | N, controlsFootnote a | VE and 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deputy, et al. (USA) | Case-control | 2193 | 8319 | 66% (47 to 78) |

| Dalton, et al. (USA) | Case-control | 309 | 608 | 86% (74 to 92) |

| Rosenberg, et al. (USA) | Case-control | 252 | 255 | 89% (44 to 98) |

| Ramchandani, et al (USA) | Cohort study | 685 | 2393 | 83% (28 to 96) |

|

||||

For Brousseau et al, risk of bias was assessed as moderate due to confounding and the selection of participants into the study. For Navarro et al, risk of bias was assessed as moderate due to confounding. For Bertran et al, risk of bias was assessed as serious due to confounding, the classification of interventions, missing data and the measurement of outcomes. For Fontan-Vela et al, the risk of bias was assessed as moderate due to confounding and the selection of participants into the study. For Sagy et al, risk of bias was assessed as moderate due to confounding. For Deputy et al, risk of bias was assessed as serious due to confounding and the measurement of outcomes. For Dalton et al, the risk of bias was assessed as serious due to confounding, the selection of participants into the study, missing data, and the measurement of outcomes. For Rosenberg et al, the risk of bias was assessed as serious due to confounding and the selection of participants into the study. For Ramchandani et al, the risk of bias was assessed as moderate due to confounding.

Effectiveness against moderate/severe mpox infection

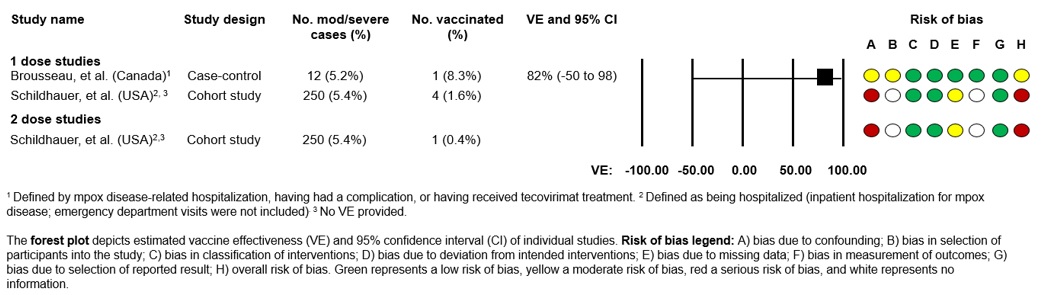

Two studies provided an estimate of effect of Imvamune® against moderate to severe mpox infection (Figure 2):

- One test-negative case-control study using vaccine administration data from Quebec estimated 1-dose aVE against moderate/severe mpox infection to be 82% (95% CI: -50 to 98%). In this study, moderate to severe mpox disease was defined as mpox disease-related hospitalization, having had a complication, or having received tecovirimat treatment. During the study period, 12 individuals had moderate to severe mpox disease, of which three were hospitalized. Only one of these 12 individuals received Imvamune®Footnote 19.

- A study from the US used surveillance data from California from May 2022 to May 2023 to estimate the odds of being hospitalized due to mpox in those with and without receipt of Jynneos®. Mpox-related hospitalization was defined as inpatient hospitalization for mpox disease, and emergency department visits were not included. Of individuals who were hospitalized for mpox, four (1.7%) received one dose, while only one (1.3%) received two doses. Compared to unvaccinated individuals, the odds of hospitalization among those with mpox who received 1 or 2 doses of Jynneos® were 0.27 (95% CI: 0.08 to 0.65) and 0.20 (95% CI: 0.01 to 0.90), respectively. Among individuals with mpox and HIV infection, the odds of hospitalization were 0.28 (95% CI: 0.05 to 0.91) for those who met the definition of having received 1 dose of Jynneos®, compared to those who were unvaccinated. None of the 19 individuals with mpox and HIV infection who received 2 doses of Imvamune® were hospitalized. Based on limitations of this study, it is unclear how CD4 counts and other markers of HIV disease progression may affect the immune response to vaccination and mpox infection due to limited numbers of individuals with HIV who were infected with mpoxFootnote 29.

Figure 2: Descriptive text

Forest plot depicts estimated vaccine effectiveness (VE) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of individual studies.

This figure consists of a table summarizing the study characteristics for studies reporting on vaccine effectiveness against moderate to severe mpox as well as a graphic depicting the vaccine effectiveness in a forest plot and a graphic depicting the risk of bias for each study.

| Study name | Study design | No. mod/severe cases (%) | No. vaccinated (%) | VE and 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brousseau, et al. (Canada)Footnote a | Case-control | 12 (5.2%) | 1 (8.3%) | 82% (-50 to 98) |

| Schildhauer, et al. (USA)Footnote bFootnote c | Cohort study | 250 (5.4%) | 4 (1.6%) | - |

|

||||

| Study name | Study design | N, cases1 | N, controls | VE and 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schildhauer, et al. (USA)Footnote aFootnote b | Cohort study | 250 (5.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | - |

|

||||

For Brousseau et al, risk of bias was assessed as moderate due to confounding and the selection of participants into the study. For Schildhauer et al, risk of bias was assessed as serious due to confounding and missing data.

Effectiveness against additional clinical outcomes

There is currently no available data on Imvamune® VE against death due to mpox or mpox transmission, nor among those previously infected with mpox.

Vaccine safety

Both pre- and post-licensure safety data support the safety of Imvamune®. According to Imvamune® clinical trial data where approximately 13,700 doses were given to 7,414 participants, the most common adverse events (AEs) reported by adults were injection-site reactions such as pain, redness, swelling, and systemic reactions including fatigue, headache, and myalgia. Most were mild to moderate in intensity and resolved without intervention within 7 days post-vaccination, and no unexpected AEs were identified. Additionally, there were no confirmed cases of cardiac events such as myocarditis and/or pericarditis following vaccination. The safety profile of Imvamune® was similar in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals.

Available post-marketing safety surveillance data on Imvamune® also suggests that the vaccine is well-tolerated. The most common AEs reported by adults following one and/or two doses were non-serious injection-site and systemic reactions, consistent with clinical trial findingsFootnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 34. The second dose was generally slightly better tolerated than the first doseFootnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33. Serious AEs were rarely reported. Specifically, there was no signal for increased risk of myocarditis or anaphylaxis following vaccination, and no new or unexpected safety concerns were identifiedFootnote 30Footnote 34Footnote 35. In Canada, data from the Canadian National Vaccine Safety Network (CANVAS) showed that Imvamune® was well tolerated, and most reported AEs were mild or moderate. Health events interfering with work/school or requiring medical assessment were less common among vaccinated individuals versus unvaccinated controls (3.3% vs. 7.1%, p < 0.010). No participants were hospitalized within seven or 30-days following vaccination. Furthermore, no cases of severe neurological disease, skin disease, or myocarditis were identifiedFootnote 34.

Concurrent administration with other vaccines

Imvamune® vaccination can be given concurrently (i.e., same day) or at any time before or after other live or non-live vaccines. Currently, there is limited data on the concurrent administration of Imvamune® with other vaccines. Available evidence suggests that concurrent administration is possible, but details on the frequency and/or type of associated AEs are not providedFootnote 31Footnote 32. Because Imvamune®is based on a non-replicating Orthopoxvirus, it may be administered without regard to timing of other vaccines. If concurrent administration with another vaccine is indicated, immunization of each vaccine should be done in a different anatomic site (e.g., different limb) with separate injection equipment.

Ethics, Equity, Feasibility and Acceptability considerations

Ethics considerations

NACI considered the importance of transparency, in terms of acknowledging any uncertainties or knowledge gaps, in fostering and maintaining public trust. Additionally, as mpox transmission generally requires close and prolonged contact (including, but not limited to, sexual contact), NACI recommendations have been made based on need and risk, rather than solely other criteria such as gender or sexual orientation.

Equity considerations

In Canada, gbMSM communities continue to be most affected by mpox. Stigma and discrimination against the gbMSM community can lead to health inequities that must be considered in immunization program development. While cases of mpox among female sex workers and/or individuals working/volunteering at sex-on-premises venues have not been reported in Canada, cases have been reported in other countries previously non-endemic for the disease since 2022; and there are overlapping sexual networks between sex workers and gbMSM communities where cases have primarily occurred in CanadaFootnote 17. This potential situational risk should be considered by immunization policy decision makers when determining vaccine eligibility.

Available evidence suggests that people living with chronic diseases (e.g., uncontrolled HIV, immunosuppression) have a higher risk of severe mpox, and are likely to have reduced vaccine responses and limited duration of protectionFootnote 6Footnote 7Footnote 8. Therefore, vaccination of individuals with uncontrolled HIV infection at high risk of mpox exposure should be prioritized.

Canadian mpox immunization programs have global implications. The majority of low- and middle-income countries with active human-to-human transmission do not have access to Imvamune® or other vaccines authorized for mpox prevention.

Feasibility considerations

Canadian jurisdictions continue to offer Imvamune® to individuals considered at high risk of mpox. Implementation as a routine program may have improved feasibility compared to ad hoc pop-up clinics employed during the 2022 mpox outbreak.

Acceptability considerations

During summer 2022, PHAC consulted with stakeholder groups representing impacted communities. Overall, gbMSM communities communicated positive attitudes towards mpox vaccination. However, since 2022, most Imvamune® recipients have only had their first dose, possibly due to factors such as perceived lower risk of infection compared to the spring/summer of 2022 when case numbers were high across many Canadian urban centers, or perceived risk of adverse events following immunization (AEFI). Therefore, emphasizing the effectiveness of a 2-dose schedule will be important when updating immunization recommendations.

Economics

While vaccine supply has been purchased and is currently managed federally, provinces and territories continue to bear the costs associated with administering the vaccination program. Cost-effectiveness analyses have not been conducted at this time for this interim guidance, but may be considered in the future. An understanding of mpox epidemiology in Canada following establishment of a focused routine immunization program will be crucial for informing future cost-effectiveness analyses.

Recommendations

Please see Table 3 for an explanation of strong versus discretionary NACI recommendations.

NACI recommendations on Imvamune® in the context of a focused routine immunization program

1. NACI recommends that individuals at high risk of mpox should receive two doses of Imvamune® administered at least 28 days (4 weeks) apart.

- Doses should be administered via subcutaneous injection. Dose sparing strategies involving intradermal administration are not recommended in the context of routine immunization.

- Those who have started a primary series with Imvamune®, in whom more than 28 days has passed without receipt of the second dose, should receive the second dose regardless of time since the first dose.

- Those who have previously received smallpox vaccination (e.g., previous generation live-replicating vaccine) and are recommended to receive Imvamune® based on risk factors for mpox should also receive a 2-dose series with a minimum interval of 28 days.

- Imvamune® vaccination can be given concurrently (i.e., same day) or at any time before or after other live or non-live vaccines.

- At this time, Imvamune® is not routinely recommended for healthcare workers, including those serving populations at high risk of mpox, with the exception of post-exposure vaccination.

- NACI guidance on the use of Imvamune in the context of a routine immunization program should be considered interim guidance, and will be re-evaluated once additional evidence emerges.

(Strong NACI recommendation)

Summary of evidence and additional considerations

- Vaccine eligibility based on increased risk for mpox should be informed by available clinical evidence and ongoing epidemiology. Risk factors may change over time and should be assessed by local and/or provincial/territorial public health.

- At this time, individuals considered at high risk of mpox in Canada include:

- Men who have sex with men (MSM) who:

- have more than one partner; or

- are in a relationship where at least one of the partners has other sexual partners; or

- have had a confirmed sexually transmitted infection acquired in the last year; or

- have engaged in sexual contact in sex-on-premises venues.

- Sexual partners of individuals who meet the criteria above.

- Sex workers regardless of gender, sex assigned at birth, or sexual orientation.

- Staff or volunteers in sex-on-premises venues where workers may have contact with fomites potentially contaminated with mpox.

- Those who engage in sex tourism regardless of gender, sex assigned at birth, or sexual orientation.

- Individuals who anticipate experiencing any of the above scenarios.

- Men who have sex with men (MSM) who:

- Based on available evidence, which is limited for other immunocompromised populations, unvaccinated individuals with uncontrolled HIV infection (e.g., CD4 count <200 x10^6 cells/L) are considered at higher risk of severe mpox. Numerous studies are reporting that two doses of Imvamune® are effective at preventing mpox and associated outcomes including among individuals living with HIV infection. Clinicians should discuss Imvamune® and risks for mpox exposure with individuals who are living with HIV.

- Given the lack of evidence on the benefits and risks, NACI is not issuing recommendations on additional doses (e.g., >2) of Imvamune®within the context of a focused routine program at this time. So far, there is no evidence to suggest that additional doses of Imvamune® are needed for individuals at high risk in community settings, including immunocompromised populations. Evidence will continue to be reviewed on this topic as it becomes available.

- NACI continues to recommend that personnel working with replicating Orthopoxviruses in laboratory settings be offered an additional dose after 2 years if they remain at risk of occupational exposure.

- Evidence is limited in pediatric populations <18 years, and the current indication of Imvamune® is for individuals 18 years of age and older. Off-label use in pediatric populations may be considered pre- or post- exposure, for those meeting the high-risk criteria, with their clinician's discretion.

- Vaccination is not recommended for individuals who have had mpox. Healthcare professionals should use clinical judgement when considering vaccinating individuals who have a history of mpox infection.

- Although there are limited data regarding Imvamune® use among specific populations (e.g., immunocompromised due to disease or treatment; pregnancy or breastfeeding), these individuals should be offered Imvamune® if vaccination is recommended based on high-risk criteria.

- Individuals at high risk of mpox and planning to travel internationally should consult with their healthcare provider on vaccination at least 4 to 6 weeks prior to travel, particularly those travelling to countries with ongoing mpox transmission. Healthcare providers should consider a traveler's responsibility to prevent the introduction and spread of mpox internationally in their recommendation to vaccinate.

- NACI will continue to monitor emerging evidence and update guidance on Imvamune® for pre-exposure and post-exposure vaccination against mpox as warranted. This will include monitoring the duration of protection following 2 doses of Imvamune® or MPXV infection, to inform the need for booster doses or vaccination of those previously infected, respectively.

- NACI previously recommended a precautionary minimum waiting period for Imvamune® administration of at least 4 weeks after or before an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Post-market safety surveillance data on Imvamune® is now available, and shows the vaccine is well tolerated with no no signal for increased risk of myocarditis or anaphylaxis following vaccination, and no new or unexpected safety concerns were identified. Therefore, NACI is now recommending Imvamune® vaccination can be given concurrently (i.e., same day) or at any time before or after other live or non-live vaccines.

2. NACI continues to recommend the use of Imvamune® as a post-exposure vaccination (also known and referred to as post-exposure prophylaxis) to individuals who have had high risk exposure(s) to a probable or confirmed case of mpox, or within a setting where transmission is happening, if they have not received both doses of pre-exposure vaccination.

(Strong NACI Recommendation)

- A post-exposure vaccine dose should be offered as soon as possible, preferably within 4 days of last exposure, but can be considered up to 14 days of last exposure.

- After 28 days, a second dose should be offered if MPVX infection did not develop, regardless of ongoing exposure status.

- Individuals with previous or active MPXV infection should not be offered Imvamune®

- Off-label use in pediatric populations is recommended for those meeting the criteria for post-exposure vaccination, and may be offered at their clinician's discretion.

- Imvamune® vaccination can be given concurrently (i.e., same day) or at any time before or after other live or non-live vaccines.

Definitions

MSM: Man or Two-Spirit identifying individual who has sex with another person who identifies as a man, including but not limited to individuals who self-identify as trans-gender, cis-gender, Two-Spirit, gender-queer, intersex, and non-binary.

Pre-exposure vaccination: Vaccine dose(s) to prevent mpox administered prior to potential exposure to mpox; also sometimes referred to as pre-exposure immunization or prophylaxis.

Post-exposure vaccination: Vaccine dose(s) to prevent mpox administered shortly following a known or presumed exposure to mpox, or a setting where transmission is happening, and before the development of any symptoms; also sometimes referred to as post-exposure prophylaxis.

| Dose number | Pre-exposure vaccinationFootnote aFootnote b | Post-exposure vaccinationFootnote aFootnote b |

|---|---|---|

| Dose 1 | 0.5mL, SC | 0.5 mL, SC, within 4 days since exposure, can be considered up to 14 days |

| Dose 2 | 0.5mL, SC, administered ≥ 28 days after dose 1 if MPXV infection did not develop | |

|

||

| Strength of NACI recommendationFootnote a | Strong | Discretionary |

|---|---|---|

| Wording | "should/should not be offered" | "may/may not be offered" |

| Rationale | Known/anticipated advantages outweigh known/anticipated disadvantages ("should"), OR Known/Anticipated disadvantages outweigh known/anticipated advantages ("should not") | Known/anticipated advantages are closely balanced with known/anticipated disadvantages, OR uncertainty in the evidence of advantages and disadvantages exists |

| Implication | A strong recommendation applies to most populations/individuals and should be followed unless a clear and compelling rationale for an alternative approach is present. | A discretionary recommendation may be considered for some populations/individuals in some circumstances. Alternative approaches may be reasonable. |

|

||

Research priorities

- Further study of the protection offered by Imvamune® vaccine against mpox infection and disease (in both pre-exposure and post-exposure prophylaxis scenarios), including:

- Understanding immune responses that confer protection against infection and disease and defining protective thresholds.

- Understanding how previous Orthopoxvirus infection or vaccination impacts the protection offered by Imvamune®.

- Real-world evidence on the VE of Imvamune®against mpox, including duration of protection over time.

- Understanding the protection incurred by MPXV infection over time, to determine the need for vaccination in those with past MPXV infection.

- Further studies on the safety of Imvamune® vaccine including both clinical trials and post-market safety surveillance.

- Targeted clinical trials on Imvamune®safety in special populations, including individuals who are pregnant or breastfeeding, children younger than 18 years of age, and people who are immunocompromised.

- Further study of mpox epidemiology to better understand disease presentation and modes of transmission, as well as identify populations at high risk for severe disease, ultimately informing and optimizing disease prevention strategies.

- Further studies on vaccine acceptability among populations at higher risk of mpox, to inform effective vaccination programming.

Abbreviations

- ACS

- Advisory committee statement

- AEs

- Adverse events

- AEFI

- Adverse events following immunization

- aVE

- Adjusted vaccine effectiveness

- CANVAS

- Canadian National Vaccine Safety Network

- CATMAT

- Canadian Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel

- CD4

- Cluster of differentiation 4

- CI

- Confidence interval

- CIG

- Canadian Immunization Guide

- DNA

- Deoxyribonucleic acid

- DRC

- Democratic Republic of Congo

- EEFA

- Ethics, equity, feasibility, acceptability

- EtD

- Evidence-to-Decision

- EUNDS

- Extraordinary Use New Drug Submission

- HIV

- Human immunodeficiency virus

- GbMSM

- Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men

- MPXV

- Monkeypox virus

- MSM

- Men who have sex with men

- MVA-BN

- Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic

- NACI

- National Advisory Committee on Immunization

- PCR

- Polymerase chain reaction

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PHECG

- Public Health Ethics Consultative Group

- PrEP

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis

- RNA

- Ribonucleic acid

- SC

- Subcutaneous injection

- STI

- Sexually transmitted infection

- US

- United States

- UK

- United Kingdom

- VE

- Vaccine effectiveness

- WG

- Working Group

- WHO

- World Health Organization

Acknowledgements

This statement was prepared by: N Forbes, K Klein, J Montroy, M Salvadori, K Gusic, and X Yiao, V Dubey, R Harrison, MC Tunis, on behalf of NACI.

NACI gratefully acknowledges the contribution of: M Tunis, K Young, A Tuite, A Howarth, L Coward, and J Daniel.

NACI members: R Harrison (Chair), Vinita Dubey (Vice-Chair), A Buchan, M Andrew, J Bettinger, N Brousseau, H Decaluwe, P De Wals, E Dubé, K Hildebrand, K Klein, M O'Driscoll, J Papenburg, A Pham-Huy, B Sander, and S Wilson.

Liaison representatives: L Bill / M Nowgesic (Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association), LM Bucci (Canadian Public Health Association), S Buchan (Canadian Association for Immunization Research and Evaluation), E Castillo (Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada), J Comeau (Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada), M Lavoie (Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health), J MacNeil (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States), D Moore (Canadian Paediatric Society), M Naus (Canadian Immunization Committee), M Osmack (Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada), J Potter (College of Family Physicians of Canada), and A Ung (Canadian Pharmacists Association).

Ex-officio representatives: V Beswick-Escanlar (National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces), E Henry (Centre for Immunization Programs, PHAC), M Lacroix (Public Health Ethics Consultative Group, PHAC), P Fandja (Marketed Health Products Directorate, Health Canada), M Su (COVID-19 Epidemiology and Surveillance, PHAC), S Ogunnaike-Cooke (Centre for Immunization Surveillance, PHAC), C Pham (Biologic and Radiopharmaceutical Drugs Directorate, Health Canada), M Routledge (National Microbiology Laboratory, PHAC), and T Wong (First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, Indigenous Services Canada).

NACI Mpox Working Group

Members: K Klein (Chair), N Brousseau, A Buchan, YG Bui, E Castillo, R Harrison, K Hildebrand, M Libman, D Tan, M Murti, A Rao, C Quach, and B Petersen.

PHAC/HC participants: SP Anand, O Baclic, P Barcellos, C Bell, J Cao, A Coady, L Coward, P Doyon-Plourde, N Forbes, P Gorton, K Gusic, A Howarth, C Jensen, W Kaouache, J Laroche, J Montroy, M Patel, M Pignat, M Plamondon, G Pulle, M Salvadori, MC Tunis, B Warshawsky, C Yan, J Venugopal, and R Ximenes.

Appendix A: Vaccine effectiveness studies

| Author, date, country | Study design, period, data sources | Study population, sample size | Vaccine | Outcome | VE analyses, resultsFootnote a | Overall risk of biasFootnote b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

UK |

Case-coverage (screening method) July 4-October 9, 2022 Public health surveillance data (England), self-report survey, laboratory reports |

At-risk gbMSM at sexual health clinics N=363 cases |

1 dose of MVA-BN |

Laboratory-confirmed symptomatic mpox infection |

VE=1-odds of vaccination in cases/population VE after ≥14 days: 78% (95% CI: 54 to 89%) |

High |

|

Canada |

Test-negative case control June 19-September 24, 2022 Public health surveillance data (Quebec), administrative data, self-report survey |

Males aged ≥18y with mpox specimens collected in Montreal All-admin population: N=231 cases N=301 controls Sub-questionnaire population: N=91 cases N=108 controls |

1 dose of MVA-BN |

Laboratory-confirmed symptomatic mpox infection and moderate-to-severe mpox disease (i.e., mpox-related hospitalization, complication, tecovirimat treatment) |

VE=1-odds of vaccination in cases/population All-admin population: aVE against mpox infection: 35% (95% CI: -2 to 59%) aVE against moderate-to-severe disease: 82% (95% CI: -50 to 98%) Sub-questionnaire population: aVE (administrative indicators only): 30% (95% CI: -38 to 64%) aVE (administrative indicators and questionnaire): 65% (95% CI: 1 to 87%) |

Moderate |

|

US |

Case-control August 19, 2022-March 31, 2023 Public health surveillance data (12 US jurisdictions), self-report survey, vaccine registries |

Sexually active MSM or transgender individuals aged 18-49y N=308 cases N=608 controls |

1 or 2 doses of MVA-BN |

Laboratory-confirmed symptomatic mpox infection |

VE=1-odds of vaccination in cases/population Total population: aVE for 1 dose: 75.2% (95% CI: 61.2 to 84.2%) aVE for 2 doses: 85.9% (95% CI: 73.8-92.4%) Immunocompromised sub-population: aVE: 70.2% (95% CI: -37.9 to 93.6%) Immunocompetent sub-population: aVE: 87.8% (95% CI: 57.5 to 96.5%) |

High |

|

US |

Case-control August 15-November 19, 2022 Epic Cosmos database (EHR) |

Cases: Individuals with mpox (cases) or incident HIV infection or taking HIV PrEP (controls) N=2,193 cases N=8,319 controls |

1 or 2 doses of MVA-BN |

Mpox diagnosis code or positive Orthopoxvirus or mpox virus laboratory result |

VE=1-odds of vaccination in cases/controls Total population: aVE for 1 dose: 35.8% (95% CI: 22.1 to 47.1%) aVE for 2 doses: 66% (95% CI: 47.4 to 78.1%) Immunocompetent sub-population: aVE for 1 dose: 40.8% (95% CI : 24.8 to 53.4%) aVE for 2 doses: 76.3% (95% CI: 57.7 to 86.8%) |

High |

|

Spain |

Retrospective cohort July 12-December 12, 2022 Public health surveillance data (15/19 regions in Spain) |

Males aged ≥18y receiving HIV-PrEP N=5,660 vaccinated N=5,660 unvaccinated |

1 dose of MVA-BN |

Laboratory-confirmed symptomatic mpox infection |

VE=1-risk of infection among vaccinated/unvaccinated group VE after ≥7 days: 65% (95% CI: 22.9 to 88.0%) VE after ≥14 days: 79% (95% CI: 33.3 to 100.0%) |

Moderate |

|

Canada |

Prospective cohort June 12-November 26, 2022 Public health surveillance data (Ontario) |

Males aged ≥18y who: (1) had a history of syphilis testing and a laboratory-confirmed bacterial STI in the prior year; or (2) filled a prescription for HIV PrEP in the prior year N=3,204 vaccinated N=3,204 unvaccinated |

1 dose of MVA-BN |

PCR-confirmed mpox infection |

VE=1-hazard rate in vaccinated/unvaccinated group VE after ≥14 days: 59% (95% CI: 31 to 76%) |

Moderate |

|

US |

Retrospective cohort May 1-December 31, 2022 Public health surveillance data and vaccine registries (Washington state) |

MSM who visited the Seattle and King County sexual health clinics at least once between January 1, 2020-December 31, 2022 N=4,230 (n=2,393 unvaccinated, n=685 vaccinated with 1 dose, n=1,152 vaccinated with 2 doses) |

1 or 2 doses of MVA-BN |

Laboratory-confirmed symptomatic mpox infection |

VE=1-hazard rate in vaccinated/unvaccinated group aVE for 1 dose: 81% (95% CI: 64 to 90%) aVE for 2 doses: 83% (95% CI: 28 to 96%) |

Moderate |

|

US |

Case-control January 1, 2020-December 31, 2022 Public health surveillance data (New York State, excluding NYC) |

Males aged ≥18y with an mpox diagnosis (cases) or diagnosed with rectal gonorrhea or primary syphilis and a history of male-to-male sexual contact, without mpox (controls) N=252 cases N=255 controls |

1 or 2 doses of MVA-BN |

Laboratory-confirmed symptomatic mpox infection |

VE=1-odds of vaccination in cases/controls aVE for 1 or 2 doses: 76% (95% CI: 49 to 89%) aVE for 1 dose: 68% (95% CI: 25 to 87%) aVE for 2 doses: 88% (95% CI: 44 to 98%) |

High |

|

Israel |

Retrospective cohort July 31-December 25, 2022 Clalit Health Services (EHR) |

Males aged 18-42y on HIV PrEP for at least one month or diagnosed with HIV and one or more STIs since January 1, 2022 N=2,054 (n=1,037 vaccinated and n=1,017 unvaccinated) |

1 dose of MVA-BN |

Laboratory-confirmed symptomatic mpox infection |

VE=1-hazard rate in vaccinated/unvaccinated group aVE: 86% (95% CI: 59 to 95%) |

Moderate |

|

US |

Retrospective cohort May 12, 2022-May 18, 2023 Public health surveillance data (California) |

California residents diagnosed with mpox N=4,611 |

1 or 2 doses of MVA-BN |

Mpox-related hospitalization |

Odds of hospitalization in persons with mpox who were vaccinated vs unvaccinated Total population: OR 1 dose vs unvaccinated: 0.27 (95% CI: 0.08 to 0.65) OR 2 doses vs unvaccinated: 0.20 (95% CI: 0.01 to 0.90) Immunocompromised sub-population: OR 1 dose vs unvaccinated in persons with HIV: 0.28 (95% CI: 0.05 to 0.91) |

High |

Abbreviations

|

||||||

References:

- Footnote 1

-

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Public Health Agency of Canada vaccine administration and epidemiology data [Unpublished]. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2023.

- Footnote 2

-

Durski KN, McCollum AM, Nakazawa Y, Petersen BW, Reynolds MG, Briand S, et al. Emergence of monkeypox - West and Central Africa, 1970-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018 Mar 16;67(10):306-10. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6710a5.

- Footnote 3

-

Likos AM, Sammons SA, Olson VA, Frace AM, Li Y, Olsen-Rasmussen M, et al. A tale of two clades: Monkeypox viruses. J Gen Virol. 2005 Oct;86(Pt 10):2661-72. https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.81215-0.

- Footnote 4

-

Ulaeto D, Agafonov A, Burchfield J, Carter L, Happi C, Jakob R, et al. New nomenclature for mpox (monkeypox) and monkeypox virus clades. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023 Mar;23(3):273-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00055-5.

- Footnote 5

-

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Mpox (monkeypox): For health professionals [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2024 Feb 12 [cited 2024 Mar 07]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/mpox/health-professionals.html.

- Footnote 6

-

Henao-Martínez AF, Orkin CM, Titanji BK, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Salinas JL, Franco-Paredes C, et al. Hospitalization risk among patients with mpox infection-a propensity score matched analysis. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2023 Aug 30;10:20499361231196683. https://doi.org/10.1177/20499361231196683.

- Footnote 7

-

Riser AP, Hanley A, Cima M, Lewis L, Saadeh K, Alarcón J, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical features of mpox-associated deaths - United States, May 10, 2022-March 7, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023 Apr 14;72(15):404-10. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7215a5.

- Footnote 8

-

Triana-González S, Román-López C, Mauss S, Cano-Díaz AL, Mata-Marín JA, Pérez-Barragán E, et al. Risk factors for mortality and clinical presentation of monkeypox. Aids. 2023 Nov 01;37(13):1979-85. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000003623.

- Footnote 9

-

National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). NACI Rapid Response: Interim guidance on the use of Imvamune in the context of monkeypox outbreaks in Canada [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada: Government of Canada; 2022 Nov 09 [cited 2024 Feb 27]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization/national-advisory-committee-on-immunization-naci/guidance-imvamune-monkeypox.html.

- Footnote 10

-

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Immunization of workers: Canadian Immunization Guide - For health professionals [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2023 Sep [cited 2024 Mar 19]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-3-vaccination-specific-populations/page-11-immunization-workers.html.

- Footnote 11

-

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). NACI rapid response: Updated interim guidance on use of Imvamune in monkeypox outbreaks in Canada: NACI rapid response, September 23, 2022 [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2022 Nov 09 [cited 2024 Mar 21]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/vaccines-immunization/rapid-response-updated-interim-guidance-imvamune-monkeypox-outbreaks.html.

- Footnote 12

-

Ismail SJ, Hardy K, Tunis MC, Young K, Sicard N, Quach C. A framework for the systematic consideration of ethics, equity, feasibility, and acceptability in vaccine program recommendations. Vaccine. 2020 Aug 10;38(36):5861-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.05.051.

- Footnote 13

-

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Epidemiological summary report: 2022-23 mpox outbreak in Canada. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2024. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/epidemiological-summary-report-2022-23-mpox-outbreak-canada.html

- Footnote 14

-

World Health Organization (WHO). 2022-23 mpox (monkeypox) outbreak: Global trends [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2024 Feb 23 [cited 2024 Mar 19]. Available from: https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/.

- Footnote 15

-

World Health Organization (WHO). Multi-country outbreak of mpox - External situation report 31 [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2023 Dec 22 [cited 2024 Mar 19]. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20231222_mpox_external-sitrep-31.pdf?sfvrsn=a48ccab5_3.

- Footnote 16

-

Viedma-Martinez M, Dominguez-Tosso FR, Jimenez-Gallo D, Garcia-Palacios J, Riera-Tur L, Montiel-Quezel N, et al. MPXV transmission at a tattoo parlor. N Engl J Med. 2023 Jan 05;388(1):92-4. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2210823.

- Footnote 17

-

Thornhill JP, Palich R, Ghosn J, Walmsley S, Moschese D, Cortes CP, et al. Human monkeypox virus infection in women and non-binary individuals during the 2022 outbreaks: a global case series. Lancet. 2022 Dec 03;400(10367):1953-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02187-0.

- Footnote 18

-

Kibungu EM, Vakaniaki EH, Kinganda-Lusamaki E, Kalonji-Mukendi T, Pukuta E, Hoff NA, et al. Clade I-associated mpox cases associated with sexual contact, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024 Jan;30(1):172-6. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid3001.231164.

- Footnote 19

-

Brousseau N, Carazo S, Febriani Y, Padet L, Hegg-Deloye S, Cadieux G, et al. Single-dose effectiveness of mpox vaccine in Quebec, Canada: Test-negative design with and without adjustment for self-reported exposure risk. Clin Infect Dis. 2024 Feb 17;78(2):461-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad584.

- Footnote 20

-

Navarro C, Lau C, Buchan SA, Burchell AN, Nasreen S, Friedman L, et al. Effectiveness of one dose of MVA-BN vaccine against mpox infection in males in Ontario, Canada: A target trial emulation. medRxiv. 2023 Oct 06:2023.10.04.23296566. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.04.23296566.

- Footnote 21

-

Bertran M, Andrews N, Davison C, Dugbazah B, Boateng J, Lunt R, et al. Effectiveness of one dose of MVA-BN smallpox vaccine against mpox in England using the case-coverage method: An observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023 Jul;23(7):828-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00057-9.

- Footnote 22

-

Fontán-Vela M, Hernando V, Olmedo C, Coma E, Martínez M, Moreno-Perez D, et al. Effectiveness of modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavaria Nordic vaccination in a population at high risk of mpox: A Spanish cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2024 Feb 17;78(2):476-83. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad645.

- Footnote 23

-

Wolff Sagy Y, Zucker R, Hammerman A, Markovits H, Arieh NG, Abu Ahmad W, et al. Real-world effectiveness of a single dose of mpox vaccine in males. Nat Med. 2023 Mar;29(3):748-52. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02229-3.

- Footnote 24

-

Deputy NP, Deckert J, Chard AN, Sandberg N, Moulia DL, Barkley E, et al. Vaccine effectiveness of JYNNEOS against mpox disease in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2023 Jun 29;388(26):2434-43. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2215201.

- Footnote 25

-

Dalton AF, Diallo AO, Chard AN, Moulia DL, Deputy NP, Fothergill A, et al. Estimated effectiveness of JYNNEOS vaccine in preventing mpox: A multijurisdictional case-control study - United States, August 19, 2022-March 31, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023 May 19;72(20):553-8. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7220a3.

- Footnote 26

-

Rosenberg ES, Dorabawila V, Hart-Malloy R, Anderson BJ, Miranda W, O'Donnell T, et al. Effectiveness of JYNNEOS vaccine against diagnosed mpox infection - New York, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023 May 19;72(20):559-63. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7220a4.

- Footnote 27

-

Ramchandani MS, Berzkalns A, Cannon CA, Dombrowski JC, Brown E, Chow EJ, et al. Effectiveness of the modified Vaccinia Ankara vaccine against mpox in men who have sex with men: a retrospective cohort analysis, Seattle, Washington. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023 Oct 24;10(11):ofad528. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofad528.

- Footnote 28

-

Kottkamp AC, Samanovic MI, Duerr R, Oom AL, Belli HM, Zucker JR, et al. Antibody titers against mpox virus after vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2023 Dec 14;389(24):2299-301. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2306239.

- Footnote 29

-

Schildhauer S, Saadeh K, Vance J, Quint J, Salih T, Lo T, et al. Reduced odds of mpox-associated hospitalization among persons who received JYNNEOS vaccine — California, May 2022–May 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023 Sep 08;72(36):992-6. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7236a4.

- Footnote 30

-

Duffy J, Marquez P, Moro P, Weintraub E, Yu Y, Boersma P, et al. Safety Monitoring of JYNNEOS vaccine during the 2022 mpox outbreak - United States, May 22-October 21, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 Dec 09;71(49):1555-9. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7149a4.

- Footnote 31

-

van der Boom M, van Hunsel F. Adverse reactions following mpox (monkeypox) vaccination: An overview from the Dutch and global adverse event reporting systems. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2023 Nov;89(11):3302-10. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.15830.

- Footnote 32

-

Montalti M, Di Valerio Z, Angelini R, Bovolenta E, Castellazzi F, Cleva M, et al. Safety of monkeypox vaccine using active surveillance, two-center observational study in Italy. Vaccines (Basel). 2023 Jun 27;11(7):1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11071163.

- Footnote 33

-

Deng L, Lopez LK, Glover C, Cashman P, Reynolds R, Macartney K, et al. Short-term adverse events following immunization with modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic (MVA-BN) vaccine for mpox. Jama. 2023 Jun 20;329(23):2091-4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.7683.

- Footnote 34

-

Muller MP, Navarro C, Wilson SE, Shulha HP, Naus M, Lim G, et al. Prospective monitoring of adverse events following vaccination with modified Vaccinia Ankara - Bavarian Nordic (MVA-BN) administered to a Canadian population at risk of mpox: A Canadian immunization research network study. Vaccine. 2024 Jan 25;42(3):535-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.12.068.

- Footnote 35

-

Sharff KA, Tandy TK, Lewis PF, Johnson ES. Cardiac events following JYNNEOS vaccination for prevention of mpox. Vaccine. 2023 May 22;41(22):3410-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.04.052.