Accelerating our response: Government of Canada five-year action plan on sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 744KB, 46 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: July 17, 2019

Related links

- In brief: Accelerating our response: Government of Canada five-year action plan on sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections

- Reducing the health impact of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections in Canada by 2030: A pan-Canadian STBBI framework for action

- Sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections

- Funding opportunities to address sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBI)

On this page

- Ministerial message

- Action plan in brief

- 1. Setting the stage

- 2. Action plan priorities

- 2.1 Moving toward truth and reconciliation with First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples

- 2.2 Stigma and discrimination

- 2.3 Community innovation – Putting a Priority on Prevention

- 2.4 Reaching the undiagnosed - Increasing access to STBBI testing

- 2.5 Providing prevention, treatment and care to populations that receive health services or coverage of health care benefits from the federal government

- 2.6 Leveraging existing knowledge and targeting future research

- 2.7 Measuring impact - Monitoring and reporting on trends and results

- 3. Creating conditions for successful implementation

- 4. Conclusion

- Glossary of terms

- Annex A: Global targets for STBBI

- Annex B: Our guiding principles

- Annex C: Federal partner departments with commitments in the STBBI action plan

- References

- Footnotes

Ministerial message

The Government of Canada has endorsed global targets that aim to end the AIDS and viral hepatitis epidemics and to reduce the health impact of sexually transmitted infections by 2030. We have worked with our partners to establish Canada's Framework for Action, Reducing the Health Impact of Sexually Transmitted and Blood-Borne Infections in Canada by 2030: A Pan-Canadian STBBI Framework for Action. And now we are launching the Government of Canada's Action Plan which specifies our priorities under the Framework.

As Canada's Minister of Health, I am concerned that the rates of HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections are either plateauing or increasing. Our public health responses to these infections must be based on evidence and be well-coordinated if we are to reverse these trends. Canada has been at the vanguard of many of the effective strategies that the world looks to in preventing HIV infections. We will draw on what we have learned to amplify our work with our partners under this Action Plan.

We must not shy away from bold and transformative action that brings the benefits of prevention, diagnosis, treatment and support to those who need them. Embracing new ideas and challenging existing paradigms will help us push boundaries and accelerate progress. The Government of Canada is committed to both leading and learning as we implement this Action Plan with you, our partners.

I have had the honour to meet with many people who have shared their personal experiences with sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections, experiences all too often marked by stigma and discrimination. I am inspired by their resilience and I am determined to provide the leadership that will reinforce human rights and support acceptance as we work together to be part of the solution to the public health challenges we are facing.

Action plans must have targets. They drive us to do better and to change our strategies when we are not achieving results. Our first priority in implementing this Action Plan is to develop domestic indicators and targets. We will work with our partners to establish these measures so that we are held accountable for meaningful reporting that matters to the people who are counting on the Government of Canada for leadership and impact.

Finally, I would like to thank all of those who provided input into this Action Plan, especially those who shared their personal stories and insights on what it will take in order to accelerate the pace of progress. We will continue to rely on you for your honest feedback and your collaboration as we move forward. I have confidence in the ingenuity of Canadians and in our capacity to solve complex problems through our dedication to people, families and communities. I look forward to our work together.

Action Plan in Brief

Objective: Accelerate prevention, diagnosis and treatment to reduce the health impacts of sexually transmitted-and blood-borne infections (STBBI) in Canada by 2030

Strategic Goals

- Reduce the incidence of STBBI in Canada

- Improve access to testing, treatment, and ongoing care and support

- Reduce stigma and discrimination that create vulnerabilities to STBBI

Commitments

Moving toward truth and reconciliation with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples

- Support First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples' priorities.

- Improve availability and accessibility of community-level data on STBBI outcomes.

- Invest in culturally safe prevention, education and awareness initiatives.

- Invest in culturally responsive initiatives, developed to facilitate access to ongoing care and support.

Stigma and discrimination

- Raise awareness of the adverse impacts of stigma and discrimination and support campaigns that promote inclusion and respect.

- Equip professionals with skills to provide culturally responsive services in safe environments.

- Invest in research on stigma and discrimination to inform responses to eliminate transphobia, biphobia and homophobia.

- Promote awareness of the impact of gender-based violence, sexism and racism on vulnerability to STBBI.

- Continue to work toward reducing the over-criminalization of HIV non-disclosure in Canada.

Community innovation

- Support communities in designing and implementing evidence-based front-line projects to prevent new and reoccurring infections.

- Bring high impact interventions to scale so that more people benefit from them.

- Support community-based efforts to reach the undiagnosed and link them to testing, treatment and care.

Reaching the undiagnosed

- Promote culturally safe community-led models to increase testing in remote, rural and northern settings.

- Develop and deploy technology that supports equitable access to testing.

- Facilitate the availability of new testing technologies on the Canadian market.

- Support the uptake and integration of new testing approaches in care systems.

Prevention, treatment and care

(applies to populations that receive health services or coverage of health care benefits from the federal government)

- Provide effective STBBI prevention, testing and treatment to eligible populations according to best practices.

- Provide coverage for treatment and health services for eligible individuals.

- Incorporate harm reduction approaches to meet the public health needs of populations more likely to be exposed to STBBI.

- Facilitate linkage to care and treatment for those individuals transitioning from federal to provincial and territorial health systems.

Leveraging existing knowledge and targeting future research

- Invest in basic, translational, and clinical research, implementation science, community-based, population health and health system research.

- Expand the prevention toolkit - vaccine and biomedical prevention research.

- Invest in emerging and innovative testing and diagnostic technologies and approaches.

- Invest in research on novel therapeutic strategies and the biological mechanisms influencing predisposition to, or persistence of, STBBI, with a continued focus on a cure for HIV.

- Develop First Nations, Inuit and Métis health research capacity.

Measuring impact

- Develop Canada's STBBI targets and indicators with our partners.

- Strengthen national surveillance systems to provide necessary data.

- Report on progress annually.

Guiding Principles

- Meaningful engagement of people living with HIV and viral hepatitis and key populations

- Moving towards truth and reconciliation

- Integration

- Cultural relevance

- Human rights

- Health equity

- Life course approach

- Multi-sectoral approach

- Evidence-based policy and programs

1. Setting the Stage

This Action Plan sets out the Government of Canada's priorities as we advance the Pan-Canadian Framework for Action, Reducing the Health Impact of Sexually Transmitted and Blood-Borne Infections (STBBI) in Canada by 2030: A Pan-Canadian Framework for Action, Footnote 1 launched by federal, provincial and territorial Minsters of Health in June 2018. Footnote *

The Pan-Canadian Framework for Action calls for a Canada where new infections are rare and people living with STBBI receive the care, treatment and support they need. It sets out three strategic goals:

- Reduce the incidence of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections;

- Improve access to testing, treatment, care and support; and,

- Reduce the stigma and discrimination that create vulnerabilities to STBBI.

Canada is part of the global effort to reduce STBBI and their impacts on the health of populations. We have endorsed global targets (Annex A) set by the United Nations and the World Health Organization, including the 90-90-90 HIV treatment targets. We are developing made in Canada targets and indicators to drive our domestic actions and unify us in our commitment to specific results.

Canada led the way in demonstrating that HIV treatment prevents HIV transmission. Footnote 2 This contributed to the 90-90-90 global targets that are mobilizing action to provide testing and treatment.

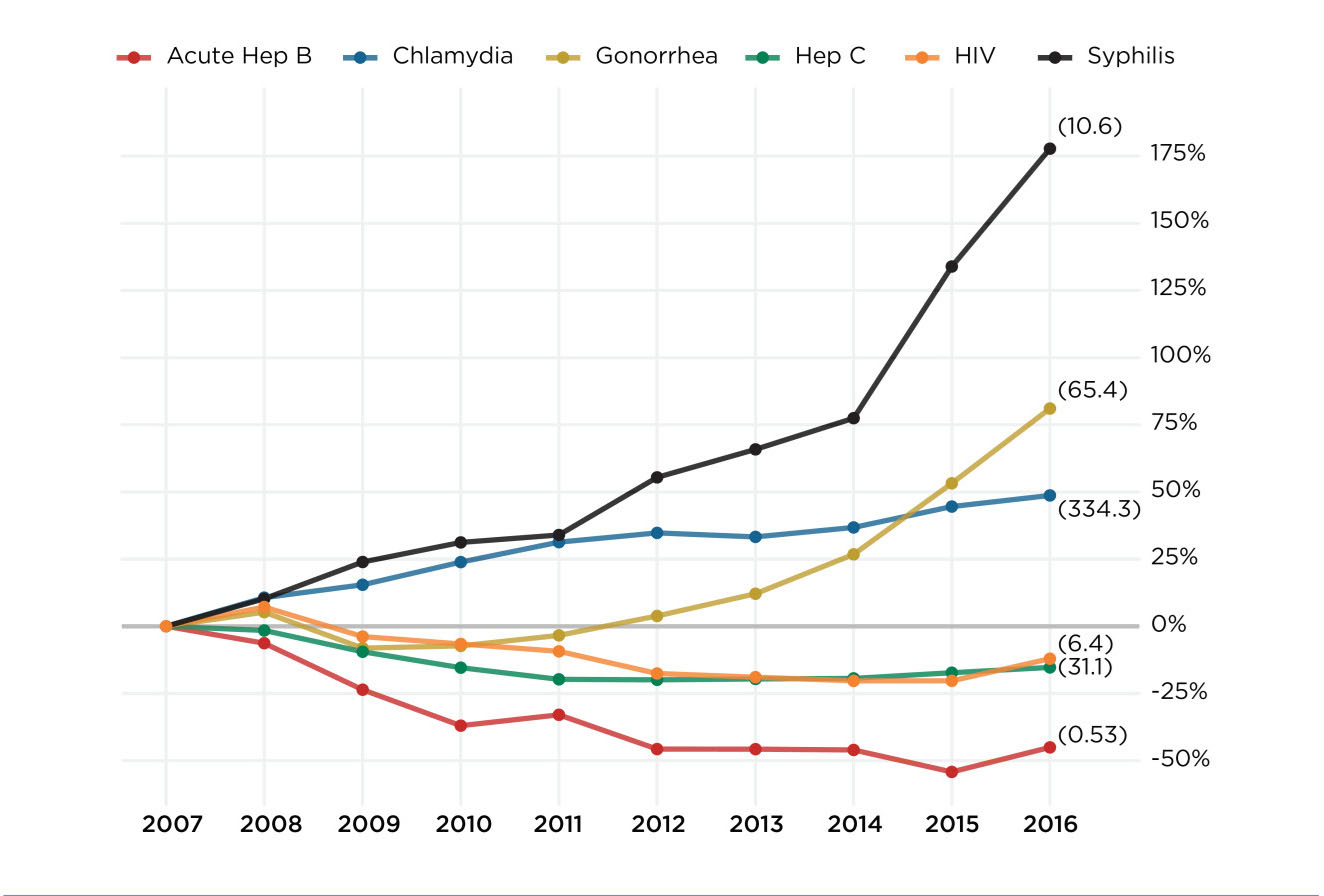

The priorities in this Action Plan are driven by evidence. STBBI are curable or manageable, and transmission can be prevented. Yet rates of sexually transmitted infections have risen dramatically over the last decade - chlamydia increased by 49 percent, gonorrhea by 81 percent, and syphilis by an alarming 178 percent (Figure 1). Even though HIV-related deaths have decreased by 90 percent since the mid-1990s, HIV transmission continues in Canada. Footnote 3 In 2017, Canada saw the highest number of HIV cases (2,387) reported since 2008. Footnote 4 Footnote 5 The rate of reported hepatitis C cases is half of what it was in the late 1990s, but we have reached a plateau with no further decreases since 2011. Footnote 6

- Figure 1 Footnote *

-

Percent change relative to the reference year of 2007

(2016 infection rates per 100,000 population indicated in brackets).

Figure 1 - Text Equivalent

This line graph shows the evolution of STBBI rates in Canada. Infections include acute hepatitis B, chlamydia, gonorrhea, hepatitis C, HIV, and syphilis. Infection rates per 100,000 population in 2016 indicated in brackets. The infection rates are 10.6, 65.4, 334.3, 6.4, 3.1, 0.53 infections per 100,000 for syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV, hepatitis C, and acute hepatitis B, respectively. The horizontal axis shows the years, ranging from 2007 to 2016. The vertical axis shows the percentage change in rates relative to the reference year of 2007. The lines for all the infections are shown on the same axes. Positive values on the vertical axis indicate an increase in the infection rate and negative values on the vertical axis indicate a decrease in the infection rate.

| Year | Acute Hep B | Chlamydia | Gonorrhea | Hep C | HIV | Syphilis |

| 2007 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 2008 | -6% | 11% | 5% | -2% | 7% | 10% |

| 2009 | -24% | 15% | -8% | -9% | -4% | 24% |

| 2010 | -37% | 24% | -7% | -15% | -8% | 31% |

| 2011 | -33% | 31% | -3% | -20% | -10% | 34% |

| 2012 | -46% | 35% | 4% | -20% | -19% | 55% |

| 2013 | -46% | 33% | 12% | -20% | -21% | 66% |

| 2014 | -46% | 37% | 27% | -19% | -21% | 77% |

| 2015 | -54% | 45% | 53% | -17% | -21% | 134% |

| 2016 | -45% | 49% | 81% | -15% | -12% | 178% |

An estimated 63,000 people in Canada are living with HIV and 14 percent (9,000) are unaware of their status. Footnote 7 Despite the availability of highly effective hepatitis C treatments, 44 percent (110,000) of the estimated 246,000 people in Canada with hepatitis C are unaware that they are infected. Footnote 8

STBBI disproportionately affect certain populations. Gay, bisexual men and other men who have sex with men account for half of all new HIV infections in Canada.Footnote 7 In 2017, among new reported HIV cases acquired through injection drug use, the majority were First Nations (61.8%), while Métis accounted for 5.7%.Footnote 4 Footnote 5 Among federally incarcerated persons, while the prevalence of HIV (2.0% in 2007 to 1.2% in 2017) and hepatitis C (31.6% in 2007 to 7.8% in 2017) have declined, Footnote 9 the rates remain higher than the general population (estimated prevalence of HIV in 2016 was 0.17% Footnote 7 estimated prevalence of hepatitis C was between 0.64% and 0.71% in 2011)Footnote 8. Although transmission of hepatitis C infection is most commonly associated with shared injection drug-use equipment, individuals may also have been infected decades ago from unsterilized medical devices or tattooing equipment, before effective infection prevention and control measures were consistently used. Others may have become infected in countries where hepatitis C is more common. Footnote 10

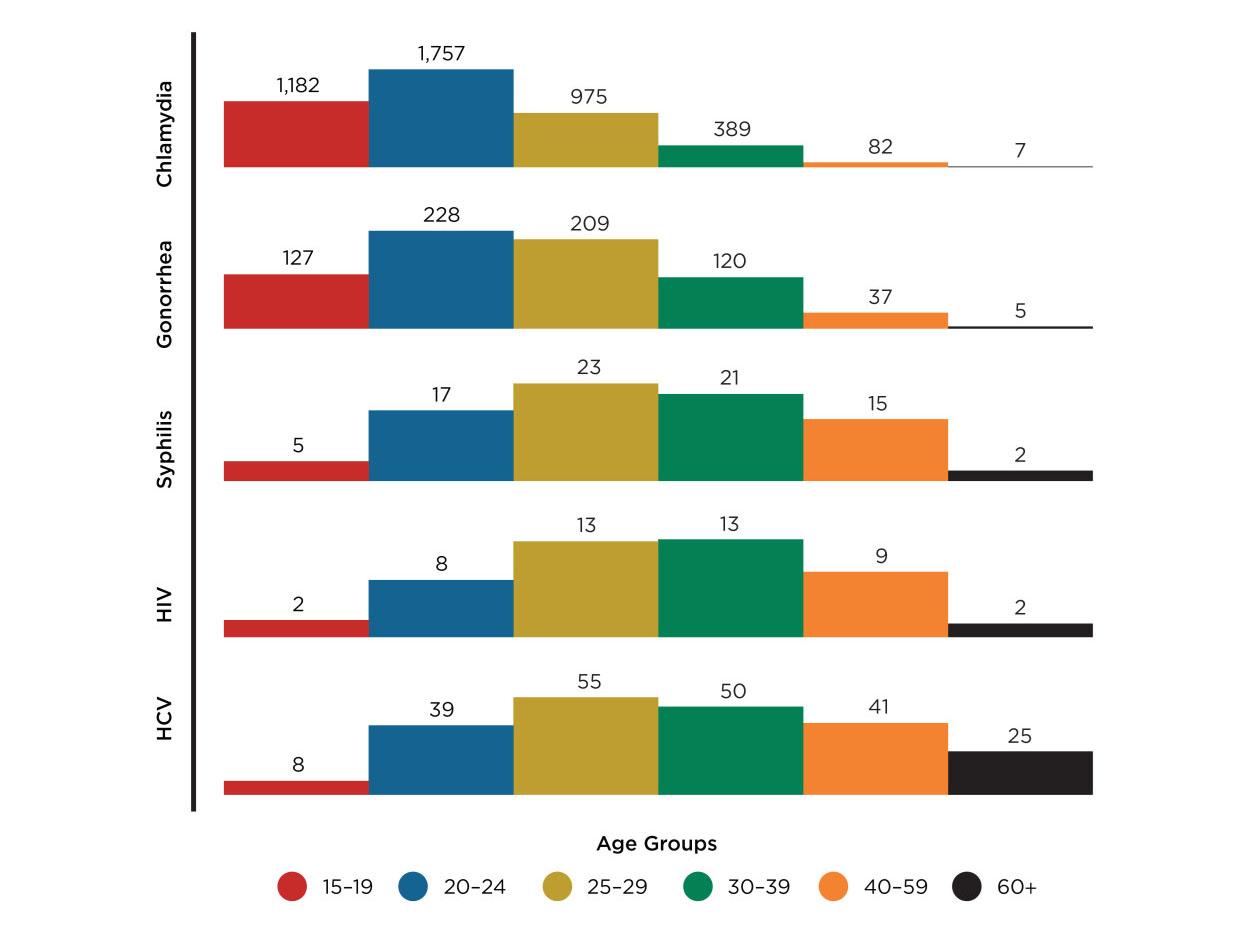

Innovation in designing and delivering targeted prevention and treatment strategies is needed to reverse these worrisome trends. Reaching the undiagnosed and linking them to appropriate care, treatment and support must be a focus of efforts to accelerate progress. STBBI affect people of all ages (Figure 2). Footnote 11 Supporting sexual health over the life course is one of the guiding principles (Annex B) of the Action Plan that will underpin its implementation.

- Figure 1 Footnote *

-

Rate per 100,000 population

Figure 2 - Text Equivalent

These bar graphs show STBBI rates in Canada by age group in 2016. The vertical axis shows the rates of infection per 100,000 population. Infections include chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis C. Each infection has its own set of bars in its own row (e.g. the infection rates for Chlamydia for each age group are on the top row, followed by gonorrhea, etc.) The horizontal axis shows age groups. The following age groups are present: 15-19 years of age, 20-24 years of age, 25-29 years of age, 30-39 years of age, 40-59 years of age, and 60+ years of age.

| Age Range | Chlamydia | Gonorrhea | Syphilis | HIV | Hep C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15-19 | 1,182 | 127 | 5 | 2 | 8 |

| 20-24 | 1,757 | 228 | 17 | 8 | 39 |

| 25-29 | 975 | 209 | 23 | 13 | 55 |

| 30-39 | 389 | 120 | 21 | 13 | 50 |

| 40-59 | 82 | 37 | 15 | 9 | 41 |

| 60+ | 7 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 25 |

While the evidence describes an urgent public health challenge, we are equipped to take action. Canada has the tools to accelerate our response to STBBI - the largest range of prevention strategies and technologies ever available, all demonstrated to reduce STBBI transmission; effective treatments; evidence to guide us in focusing strategies and resources; and exceptional research that is driving innovation. Our challenge is to deploy these tools effectively and appropriately and deliver them at the scale required for greatest impact.

The British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS and the Public Health Agency of Canada's National Microbiology Laboratories undertake phylogenetic analysis and molecular sequencing to identify clusters of genetically similar HIV infections from anonymous data. This helps to inform outbreak responses as well as screening and treatment efforts.

It is important to recognize that we are launching this Action Plan at a time when Canada is in the midst of an opioid crisis. We are witnessing an unprecedented number of deaths and a scope of impact not seen since the height of the HIV epidemic. Between January 2016 and December 2018, the opioid crisis has claimed the lives of more than 11,500 Canadians, Footnote 12 and this number continues to rise rapidly. The public health crisis resulting from the contaminated drug supply is having an impact across the country, and all levels of government are taking action. Federal actions aim to improve access to harm reduction services, which also reduce vulnerability to STBBI; raise awareness of the risks of opioids; explore options for safer alternatives to the contaminated drug supply; and, remove barriers to treatment, including reducing stigma associated with the use of drugs. As the opioid crisis has evolved, strong synthetic opioids have been found as contaminants in a broader range of illegal drugs, including methamphetamines and cocaine. The use of these substances intravenously or through inhalation increases the risk of acquiring HIV and hepatitis C, and is associated with the transmission of sexually transmitted infections among people who use drugs.

We also cannot ignore the impact of the growing global threat of antimicrobial resistance on progress in achieving the STBBI global targets. Footnote 13 The fact that we are running out of treatment options for gonorrhea, for example, illustrates the impact of antimicrobial resistance on STBBI treatment. The Pan-Canadian Framework for Action on Antimicrobial Resistance and Antimicrobial Use, Footnote 14 released by the federal, provincial and territorial ministers of health and agriculture in 2017, and the corresponding Pan-Canadian Action Plan, currently being co-developed by the health, agriculture and agri-food sectors, will support the STBBI Action Plan.

The Government of Canada recognizes and respects the mandates and jurisdictions of our partners and, through this Action Plan, will provide leadership to accelerate our collective response to STBBI. We will take action in areas of federal jurisdiction and will support and complement the work of others to achieve the greatest impact in preventing, testing, treating, and caring for those living with STBBI.

2. Action Plan Priorities

Seven inter-related priorities, involving ten federal government departments and agencies, constitute this Action Plan. Annex C describes the mandates of these departments, within an STBBI context, and specifies the actions each will lead/implement under this plan.

Action Plan Priorities:

- Moving Toward Truth and Reconciliation with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples

- Stigma and discrimination

- Community innovation

- Reaching the undiagnosed - Increasing access to STBBI testing

- Provide prevention, treatment and care to populations that receive health services or coverage of health care benefits from the federal government

- Leveraging existing knowledge and targeting future research

- Measuring impact - monitoring and reporting on trends and results

2.1 Moving toward truth and reconciliation with First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples

In keeping with the Government of Canada's commitment to implementing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Calls to Action, Footnote 15 we will continue our efforts to renew the nation-to-nation, Inuit-Crown, and government-to-government relationships with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples in order to reduce the health impacts of STBBI. Through the implementation of this STBBI Action Plan, we will take a whole-of-government approach to ensure that underlying structural inequalities and determinants of health are taken into account as part of efforts to address STBBI among First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples.

In the context of STBBI programs and services, we will utilize a distinctions-based approach and work closely with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples and communities to ensure that the development and implementation of culturally safe policies and programs reflect their unique circumstances, priorities and goals. For example, Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada's national Inuit sexual health strategy, Tavva, Footnote 16 identifies Inuit-specific goals, values, and strategic priorities for sexual health, including preventing STBBI. We will work collaboratively to ensure that the Government of Canada's actions on STBBI are complementary to those of First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples and with full recognition of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Throughout the development of the Pan-Canadian STBBI Framework for Action and the STBBI Action Plan, we moved towards Truth and Reconciliation throughout our engagement process with First Nations, Inuit and Métis organizations and community representatives.

Strengths-based approaches are needed to address STBBI in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities. Prevention, care, treatment and support services for STBBI must be culturally safe and developed in partnership with the communities they serve in order to reflect First Nations, Inuit and Métis ways of knowing. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Call to Action #22 "calls upon those who can effect change within the Canadian health-care system to recognize the value of Aboriginal healing practices and use them in the treatment of Aboriginal patients in collaboration with Aboriginal healers and Elders where requested by Aboriginal patients." Traditional healing practices, as part of a holistic approach, and community involvement and empowerment are needed to reduce the harms associated with STBBI among First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples. Connecting with culture is an effective way to improve health and maintain well-being. The Government of Canada will work with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples to support efforts in this regard. For example, in April 2019, the First Nations Health Authority, Public Health Agency of Canada, Indigenous Services Canada, and Health Canada signed the Joint Declaration of Commitment to Advance Cultural Safety and Humility in Health and Wellness Services. This declaration aims to improve cultural safety and humility in the health system and ensure First Nations feel safe in accessing the health system in Canada.

Experiences of systemic racism, discrimination and distrust of the health care system can act as significant barriers to equitable access to STBBI services. Cultural competency training for health care professionals, identified in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Call to Action #23, is one vital component needed to improve the provision of culturally safe health care services, including the continuum of STBBI prevention, care, treatment and support programs and services. Supporting initiatives to build community capacity, and peer- and team-based approaches to engaging with the health care system (such as peer outreach, peer navigators, and STBBI testing support) can also contribute to improved access to STBBI services for First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples.

What is Know Your Status?

A screening program developed by Big River First Nation in Saskatchewan to reduce HIV stigma, and provide prevention and testing services in a culturally safe manner. It led to a significant increase in the number of people with an undetectable viral load and a reduction in the number of new infections.

First Nations, Inuit and Métis know the strengths and needs of their communities and are best placed to lead the initiatives that will prevent new infections and link those affected by STBBI to culturally safe and effective diagnosis, treatment and care. Examples include the Know Your Status model in Saskatchewan and the DRUM and SASH project in Alberta. The Government of Canada also recognizes that each community has unique health needs and that these extend beyond STBBI. For rural, remote and northern communities, equitable access to prevention, care, treatment and support can present particular challenges. Historically, policies aimed at assimilating First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples led to the displacement of populations and to ongoing health, educational and economic inequities and disadvantages. For these reasons, we will continue to collaborate with provinces and territories to improve access to the continuum of STBBI care. Federal departments will work together on structural issues, including social determinants of health and health inequities, and link to other efforts related to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Calls to Action, through permanent bilateral mechanisms with First Nations, Inuit and Métis leadership and other government-wide reconciliation initiatives.

National and community-based First Nations, Inuit and Métis organizations play a critical role in delivering sexual health education, prevention activities, developing culturally-adapted resources and conducting community capacity building activities across the country. In addition to investments made by Indigenous Services Canada in on-reserve settings and for Inuit living south of the 60th parallel, the Public Health Agency of Canada provides dedicated funding for Indigenous-led projects outside of reserve settings. The Public Health Agency of Canada's dedicated project funding is based in Indigenous ways of knowing, and the priorities for community-based funding programs which support Indigenous-led STBBI projects and initiatives will continue to be co-developed with First Nations, Inuit and Métis organizations and people, including organizations representing individuals who identify as Two-Spirit.

Finally, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Call to Action #19 identifies the need to establish measurable goals to identify and close the gaps in health outcomes for Indigenous Peoples. We recognize the significant gaps in the current STBBI data for First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples. The Government of Canada will continue to support the development and implementation of studies and other mechanisms that support decision-making by First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples and organizations about health and related issues. In addition, the development of STBBI targets and indicators that are relevant to First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities will be a key area of work going forward.

The Government of Canada will:

- Support First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples' priorities.

- Improve availability and accessibility of community-level data on STBBI outcomes.

- Invest in culturally-safe prevention, education and awareness initiatives.

- Invest in culturally-responsive initiatives, developed to facilitate access to ongoing care and support.

2.2 Stigma and discrimination

Human rights principles that include equality, non-discrimination, privacy, confidentiality, and respect for personal dignity and autonomy are fundamental to the development and implementation of effective programs and services that address STBBI vulnerability and prevent transmission. Within a broader human rights framework, stigma and discrimination undermine the provision of, and access to, effective STBBI prevention, care, treatment and support. For these reasons, addressing STBBI-related stigma and discrimination is a priority of this Action Plan.

In all instances, stigma and discrimination have a direct and negative impact on the health of all those affected by, and vulnerable to, STBBI. STBBI are curable or manageable and their transmission can be prevented. The imperative to replace fear and ignorance with evidence and knowledge is foundational to this Action Plan.

Disproportionate rates of STBBI affect populations that face stigma and discrimination of various forms (such as racism, sexism and homophobia), including First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples, gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men, and people who use substances. In fact, stigma and discrimination can increase vulnerability to STBBI by affecting self-esteem, social support networks and mental health. In turn, these factors can perpetuate high risk sexual and substance use behaviours that increase the likelihood of exposure to STBBI. Negative experiences with the health care system and concerns about discrimination by health care providers are barriers to accessing health services generally and STBBI testing and treatment specifically. Footnote 17

Stigma extends beyond health care and into communities. People may worry about disclosing their infection to their family or community out of fear of rejection or exclusion. The over-criminalization of HIV non-disclosure in Canada has also contributed to HIV stigma. Footnote 18

Because of the persistence of stigma and discrimination and their profound impact on access to health care and social services, we will put a priority on supporting community-based projects that embed evidence-based strategies to address these barriers. This includes training and education for health and social service providers on cultural competency, sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression, so that care is delivered in safe and non-stigmatizing environments.

On World AIDS Day 2018, Canada became the first country to endorse the Undetectable = Untransmittable (U=U) campaign, Footnote 19 a movement dedicated to promoting HIV treatment uptake, adherence and retention in care, and reducing HIV stigma. While the U=U message has the potential to be a powerful tool to promote the importance of HIV treatment adherence and to reduce stigma, achieving and sustaining viral suppression may not be possible for some individuals. Consequently, while promoting the U=U message, the Government of Canada will support actions to address HIV stigma and discrimination, including initiatives in health and social service settings.

U=U is based on the substantial body of scientific evidence demonstrating that for people living with HIV, who have achieved a sustained undetectable viral load, there is effectively no risk of sexual transmission.

In 2017, the Government of Canada made a significant step forward in raising awareness and addressing concerns about over-criminalization of HIV non-disclosure in Canada, with the report on the Criminal Justice System's Response to Non-Disclosure of HIV. Footnote 20 The report reaffirms that HIV is fundamentally a public health issue and that the criminal law should not apply to persons living with HIV who have maintained a suppressed viral load and have not disclosed their status to their sexual partner. The report also found that the criminal law should generally not apply in certain circumstances, such as when viral load is not suppressed but condoms are used. Further to the report, a directive was issued on World AIDS Day 2018 by the Attorney General to federal prosecutors, to ensure that the prosecution of HIV non-disclosure cases under federal jurisdiction is consistent with this scientific evidence. The Government of Canada will continue to work to reduce the over-criminalization of HIV non-disclosure in Canada.

The Government of Canada is committed to reducing barriers to blood and plasma donation for gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men and for transgender people, while maintaining the highest standards to ensure the safety of Canada's blood and blood products. We have already authorized the reduction of the donation deferral period incrementally from indefinite to three months for these individuals and we are supporting research to strengthen the evidence base to ensure a safe and non-discriminatory approach to blood donation.

The STBBI Action Plan is consistent with and supported by the Government of Canada's commitment to address homophobia, biphobia and transphobia and to ensure that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and Two-Spirit (LGBTQ2) populations are included and reflected in all federal government programs and policies. In working to address stigma and discrimination, the Government of Canada is also advancing its commitment to implementing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Calls to Action. As part of our response to the opioid crisis, we will continue to take action to reduce stigma toward people who use drugs. Dedicated federal efforts focused on better understanding and addressing the root causes of racism, sexism, ageism, homophobia, transphobia, biphobia, gender-based violence and other inequities will enable our initiatives to address STBBI.

The Government of Canada will:

- Raise awareness of the adverse impacts of stigma and discrimination and support campaigns that promote inclusion and respect.

- Equip professionals with skills to provide culturally responsive services in safe environments.

- Invest in research on stigma and discrimination to inform responses to eliminate transphobia, biphobia and homophobia.

- Promote awareness of the impact of gender-based violence, sexism and racism on vulnerability to STBBI.

- Continue to work toward reducing the over-criminalization of HIV non-disclosure in Canada.

2.3 Community innovation – Putting a Priority on Prevention

The Government of Canada's longstanding support for the prevention of STBBI through investments in the community-based response remains central to this Action Plan. Communities are best positioned to identify and implement solutions that are appropriate to their contexts and cultures. The historical successes of community-based organizations in bringing attention to and action on public health challenges continue to inspire and mobilize collective efforts.

The HIV and Hepatitis C Community Action Fund, administered by the Public Health Agency of Canada, supports community innovation in prevention, and linkage to testing, treatment and care, in the context of the underlying systemic barriers that impede access to these services. Working in collaboration with affected populations, provinces and territories, community-based organizations, and non-reserve First Nations, Inuit and Métis organizations, this Fund is an important mechanism to facilitate the evaluation and scale-up of effective strategies.

A pillar of the Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy and the Government of Canada's response to the opioid crisis is harm reduction. The Government of Canada considers harm reduction to be essential for a comprehensive, compassionate and collaborative public health response to prevent the transmission of infectious diseases resulting from the sharing of drug-use equipment. Recognizing that communities are central to this effort, and that some communities experience inequitable access to harm reduction services, the Government of Canada established a Harm Reduction Fund in 2017 to advance front-line harm reduction interventions. The objective is to reduce the risk of STBBI from sharing drug-use equipment and other related behaviours. Investments in harm reduction research through the Canadian Research Initiative in Substance Misuse Footnote 21 will provide the evidence needed to develop and deploy effective harm reduction strategies.

Harm reduction generally refers to a pragmatic public health approach to potentially injurious behaviour that seeks to prevent injury, disease transmission and death while not seeking to eliminate the behaviour itself. In the substance use context, harm reduction aims to reduce the negative health, social and economic impacts of substance use on individuals, their families and communities, without requiring abstinence. It acknowledges the central role of people who use drugs in program development and aims to improve people's health and help them make connections with health and social services, including treatment. Footnote 22

The Harm Reduction Fund makes targeted community-based investments, complementing provincial and territorial governments' harm reduction strategies, to reduce HIV and hepatitis C infections among people who share injection and inhalation drug-use equipment. Projects supported under the Harm Reduction Fund deploy evidence-based interventions to address the priority needs of this population and rely on the lived experience of people who use drugs to guide project design and implementation.

To amplify efforts to reduce stigma and promote the inclusion of people living with STBBI, the Government of Canada will prioritize investments, made through our community-based funding programs, which offer services in a culturally responsive and safe environment.

We will focus on populations most likely to be exposed to infection to maximize the impact of our investments. This means putting a priority on front-line community-based interventions that accelerate efforts to address gaps and help reach the undiagnosed, including well-established STBBI prevention programs and messages (such as sexual health education, promoting safer sex and condom use, and vaccinations for vaccine-preventable STBBI). It means supporting projects that advance innovations, such as Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent new HIV infections. We will collaborate with provinces and territories so that federal investments are well-aligned, complementary, and lead to sustainable action.

Combination prevention is an effective prevention tool for populations at increased risk for HIV infection. It includes sexual health education, vaccination, condom use, taking PrEP for HIV prevention, regular STBBI testing and achieving an undetectable viral load.Footnote 23

A principle of this Action Plan is an integrated approach to STBBI. The intent is to move beyond single disease-focused programs and initiatives so that our interventions take the common features of STBBI (e.g. risk factors, transmission routes, co-infections, social determinants of health) into consideration. We believe that siloed strategies can frustrate our collective efforts to advance holistic programs and services. Consequently, we are committed to the principle of integration with regard to STBBI and will work with all our partners to achieve this objective. At the same time, we recognize that in certain circumstances a disease-specific approach is required to address unique facets of specific infections. The HIV and Hepatitis C Community Action Fund is an important mechanism for achieving appropriate integration of STBBI as we move forward.

Finally, we will strengthen community capacity to support the scale-up of high potential, high impact solutions. This will require purposive effort, based on evidence, working with our partners, to leverage each others strengths, mechanisms, and resources.

The Government of Canada will:

- Support communities in designing and implementing evidence-based front-line projects to prevent new and reoccurring infections.

- Bring high impact interventions to scale so that more people benefit from them.

- Support community-based efforts to reach the undiagnosed and link them to testing, treatment and care.

2.4 Reaching the Undiagnosed - Increasing Access to STBBI Testing

Current approaches to STBBI testing are not reaching everyone who could benefit from testing and linkage to care and prevention programs. For some, late stage diagnosis of an infection is associated with poorer health outcomes. Recent reports of vertical transmission of syphilis and HIV in Canada, for example, highlight the fact that current approaches to prevention and testing are not reaching everyone who would benefit from them.

Hepatitis C, one of the leading causes of infectious disease deaths in Canada, Footnote 24 can be cured with highly effective treatments. Accessible life-long therapy for chronic hepatitis B, along with robust treatment interventions following possible exposure, and population-based vaccination programs, prevent transmission of hepatitis B. Vaccines are available and widely recommended to prevent human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. Footnote 25

The life expectancy of people living with HIV who have access to effective treatment has increased over the past decades. Footnote 26 People who are on HIV treatment and have achieved an undetectable viral load have effectively no risk of transmitting HIV to their sexual partners. Footnote 27 People who are HIV negative but at greater risk of exposure to the virus can reduce their risk of HIV by taking PrEP. Footnote 28

STBBI testing facilitates entry to STBBI care, provides opportunities for health promotion and prevention discussions, and linkage to treatment. Reaching people where they are through the provision of supportive, stigma-free testing environments facilitates dialogue on broader issues of sexual health, mental health, and addiction. Ideally this will result in sustained engagement with culturally safe health and social services that lead to improved health outcomes.

A range of testing options is required that address the specific needs and circumstances of populations. These options should increase equitable access to testing, complementing conventional, well-established testing programs in place across the country.

Innovative Diagnostics Program

National Microbiology Laboratory - Public Health Agency of Canada

Conventional methods for STBBI testing that rely on the collection of whole blood samples and their transport to a laboratory require an infrastructure that is often unavailable in remote, northern locations, or communities with limited access to testing services. Additionally, systems to maintain confidentiality and to reduce fear of stigma associated with testing are not always in place. Add to this the challenges that people face in connecting with conventional health care services, and the need for new strategies to expand access to testing is evident.

The Public Health Agency of Canada's National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) has established an Innovative Diagnostics Program to develop and deploy technological solutions to deliver infectious disease testing programs to underserved communities. Using novel, culturally safe and community-led methods, this Program will enhance equitable access to STBBI testing that supports integrated pathways for treatment and ongoing care. This includes building capacity in remote and under-served communities that will sustain the use of these testing procedures according to community-led and culturally safe approaches. Specifically, the NML is implementing the use of Dried Blood Spot (DBS) technology for STBBI testing. This innovative approach to diagnostics utilizes validated tests for HIV, hepatitis B and C, and syphilis. Blood from a finger prick is collected on a card and mailed to the NML for testing. This approach to testing in underserved communities is receiving significant uptake due to its convenience and suitability for use outside of conventional health care settings. Capacity building and training for local community members will ensure that testing is sustainable, standardized and of high quality.

Some alternative approaches to testing, such as point-of-care testing (POCT), anonymous testing and self-testing remain unavailable in parts of the country. Deploying new technologies in non-health settings must be part of strategies to reach the undiagnosed and link them to treatment. The Government of Canada is committed to playing its role in the development, regulatory approval and deployment of POCT and additional novel technologies, according to standardized methods that assure quality.

Conventional health care settings or services with routine hours of operation limit access to existing diagnostic testing for many affected populations. Programs promoting community-based POCT, Dried Blood Spot (DBS) testing and self-testing could empower a wide range of people not reached by current approaches to STBBI testing. The increasing availability and use of STBBI self-test kits could supplement conventional testing regimens and provide another tool for increasing access to testing. Further dialogue and research on services, including counselling and linkage to care, are necessary to realize the benefits of self-testing.

The Government of Canada is responsible for licensing medical devices to assure their quality, safety and efficacy before being authorized for sale and use in Canada. We are committed to efficient and timely review of medical devices and will continue to work with manufacturers and key stakeholders to provide guidance about the regulatory review process and to improve the quality of medical device applications and, ultimately, to support the roll-out of new diagnostic technologies across the country. For STBBI tests conducted on DBS, which are not currently licensed by Health Canada, we will ensure that the tests are thoroughly validated and that information is available to public health jurisdictions to support their appropriate use and interpretation.

Reaching the undiagnosed is key to improving the health of people living with STBBI and reducing transmission. The Government of Canada will continue to support programs and initiatives that promote access to and uptake of STBBI testing. We will provide and update guidance on the diagnosis and treatment of STBBI in line with the research evidence and use technology to make it more accessible to health care providers. As new testing options become available in Canada, we will also work with our provincial, territorial, and First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners, and stakeholders to ensure that care providers and community-based service providers alike, have up-to-date guidance that supports the appropriate implementation of new technologies and their integration into health care and data systems.

The Government of Canada will:

- Promote culturally safe community-led models to increase testing in remote, rural and northern settings.

- Develop and deploy technology that supports equitable access to testing.

- Facilitate the availability of new testing technologies on the Canadian market.

- Support the uptake and integration of new testing approaches in care systems.

2.5 Providing prevention, treatment and care to populations that receive health services or coverage of health care benefits from the federal government

The Government of Canada funds and provides a range of health services or coverage of health care benefits for serving members of the Canadian Armed Forces, certain immigrant populations, incarcerated individuals in federal correctional facilities, and registered First Nations and eligible Inuit. These individuals receive a range of public health and health care services, according to their needs and contexts, from federal health officials. Those who do not directly receive health care services are either eligible to receive coverage of health care benefits or are eligible for coverage of costs not included as part of provincial and territorial health services or drug plans. The federal institutions that administer these services are guided by data on the health of these populations, evidence-based practice, and research evidence. Unique vulnerabilities call for unique solutions and the Government of Canada strives to address the health issues of these groups in culturally safe and responsive ways.

First Nations and Inuit

With the creation of Indigenous Services Canada, the Government of Canada has taken an important step towards supporting improved health outcomes by taking a broader approach that considers the social and economic factors that have an impact on health and well-being together under one new department. The First Nations and Inuit Health Branch of Indigenous Services Canada supports the delivery of public health services, including prevention education and awareness, in First Nations communities on-reserve and in Inuit communities, as well as primary care services on-reserve in remote and isolated areas where there are no provincial services readily available. Eligible First Nations and Inuit also receive coverage for a range of medically necessary health benefits-related goods and services through the Non-Insured Health Benefits program, which are not otherwise covered through private or provincial/territorial health and social programs. These benefits include prescription drugs for the treatment of STBBI when not covered by the province or territory of residence, access to PrEP and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), medical supplies and equipment, mental health counselling, addictions treatment services and centres, and transportation to access medically required health services that are not available in the community of residence. Government of Canada nurses and those hired by Territorial governments and band councils, work in nursing stations and health centres in rural, remote and isolated First Nations and Inuit communities across the country. They continue to strive to provide care in culturally diverse communities, including immunization, community education, testing and treatment using a holistic, trauma-informed and culturally safe approach to care.

Members of the Canadian Armed Forces

The Canadian Forces Health Services is committed to providing healthcare to Canadian Armed Forces personnel both in Canada and abroad. The multi-disciplinary healthcare team will ensure that prevention, education, surveillance, contact tracing and treatment of STBBI for members of the Canadian Armed Forces is delivered according to national clinical practice guidelines.

Federally incarcerated individuals

The Government of Canada provides essential health care services that contribute to federally incarcerated individuals' rehabilitation and successful reintegration into the community. For STBBI prevention and treatment, a comprehensive suite of services is provided: recommended vaccinations for hepatitis B and human papillomavirus infection; PrEP and PEP for persons at risk for HIV infection; prevention education and awareness; condoms and bleach; correctional programs and referral to mental health services to address substance use and replacement therapies for individuals who use substances; confidential and routine offer of STBBI screening and counselling and effective treatment to individuals diagnosed with STBBI. The Government of Canada also works with provincial and territorial correctional facilities and health authorities to improve continuity of care during transition for incarcerated individuals. The Government of Canada is committed to providing trauma-informed and culturally safe health services in correctional settings. We will increase access to harm reduction services and will continue to implement a prison-based needle exchange program. Having done so, we have made significant progress towards meeting the 90-90-90 HIV targets and have significantly decreased the prevalence of hepatitis C.

Immigrant populations

The Government of Canada, through the Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP) will continue to provide limited, temporary coverage of health care benefits for resettled refugees, asylum seekers, and certain other groups in Canada (e.g., victims of trafficking and persons detained under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act) until they become eligible for provincial/territorial health care coverage or, in the case of unsuccessful asylum seekers, leave Canada. This includes medical services and prescription drugs for the treatment of STBBI.

Changes made to the excessive demand policy under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, Footnote 29 effective June 1, 2018, tripled the cost threshold for determining excessive demand on health or social services. This change decreases the number of foreign nationals deemed inadmissible to Canada on medical grounds. Under the Act, foreign nationals are found inadmissible if they have a health condition that might reasonably be expected to cause an excessive demand on health or social services, either by exceeding the defined cost threshold or by impacting wait lists. The Government of Canada is monitoring changes in rates of approvals and refusals under the new policy and anticipates fewer refusals of applicants living with HIV or hepatitis, given that the cost of treatment for these infections, in most cases, is expected to be under the new cost threshold.

The Government of Canada will also continue to provide systematic HIV screening for individuals who are required to undergo an immigration medical examination, and notify provinces and territories of new arrivals in their jurisdictions who are HIV-positive. This screening and notification supports continuity of care and treatment for HIV-positive individuals entering Canada, and informs epidemiological surveillance of HIV.

The Government of Canada will:

- Provide effective STBBI prevention, testing and treatment to eligible populations according to best practices.

- Provide coverage for treatment and health services for eligible individuals.

- Incorporate harm reduction approaches to meet the public health needs of populations more likely to be exposed to STBBI.

- Facilitate linkage to care and treatment for those individuals transitioning from federal to provincial and territorial health systems.

2.6 Leveraging Existing Knowledge and Targeting Future Research

Forty years of Canadian and international research investments fostered important biomedical discoveries that have and continue to inform the development of effective HIV prevention strategies, PrEP, treatment as prevention, microbicides and vaccines. Treatment options for STBBI have improved, increasing positive health outcomes for those living with HIV, hepatitis C and other STBBI. Research has brought us a cure for hepatitis C and work continues towards a cure for HIV.

We will continue to fund STBBI research through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research's investigator-initiated funding opportunities and focus our dedicated STBBI research investments on the public health priorities identified in the Pan-Canadian STBBI Framework for Action and in the STBBI Action Plan.

Science is advancing our understanding of the physical, mental and social impacts of living with chronic infection and its effect on quality of life and social integration, leading us to effective strategies to support better health and social outcomes for those living with HIV. Behavioural and community-based research investments have also improved our understanding of risk behaviours and helped identify effective structural and individual-based interventions.

Infection-specific differences are present across geography, populations, life-stages and gender. The experience of stigma and discrimination may vary depending on the infection. Similarly, biological processes, transmission, and disease progression are infection-specific, as are their health consequences. In addition, the state of knowledge differs for each infection. Consequently, we will align knowledge creation and dissemination efforts to capture these realities.

Between 2007 and 2017, the Government of Canada's investments in the Canadian HIV Trials Network has facilitated clinical research and trials focused on HIV interventions. Biomedical prevention strategies, including research on HIV vaccine-related mucosal immunology and on hepatitis C vaccine, have built significant Canadian capacity in this area. Moving forward, we will continue to invest in the development of innovative biomedical prevention strategies and vaccines for HIV, hepatitis C and other STBBI. We will facilitate the development of these new technologies and therapies through a deeper understanding of the biomedical, behavioral, social and structural factors of susceptibility and resistance to acquiring STBBI and affecting progression of diseases and poor health outcomes. Our support for research on new diagnostic technologies and on the biological mechanisms that contribute to HIV and other STBBI persistence will result in novel therapeutic strategies as we continue to focus on finding cures.

In addition, the Government of Canada will focus on implementation science, participatory and community-based research that is multi and interdisciplinary, and that integrates the knowledge and experience of affected populations. This will support the development of transformative interventions to advance equity across gender and affected populations in Canada and worldwide. It will allow us to assess the effectiveness of new stigma reduction efforts, prevention, diagnosis and testing, treatment and care models among populations most affected. Ultimately, our approach will contribute to the evidence-base of effective interventions that should be scaled-up in Canada and globally.

Consistent with the priorities of this Action Plan, the Government of Canada's research investments will help us understand our progress by linking data sources and conducting studies to monitor the prevention, testing and treatment cascades for HIV, hepatitis C, and other STBBI. We will support community-based research to ensure that affected populations and communities, including First Nations, Inuit and Métis, lead these efforts. In partnership with Indigenous communities and scholars, and academic institutions, we will develop First Nations, Inuit and Métis research capacity to support innovative and culturally safe evidence-based approaches, programs and services including knowledge translation activities, for STBBI.

The testing and treatment cascades refer to the stages of care that people go through from diagnosis to treatment, and in the case of HIV, achieving viral suppression.

Research priorities will focus on achieving the objectives set out by the Pan-Canadian STBBI Framework for Action and the STBBI Action Plan. They will be informed through a consultative process with researchers from multiple disciplines, people with lived experience, community-based organizations, and civil society.

The Government of Canada will:

- Invest in basic, translational, and clinical research, implementation science, community-based, population health and health system research.

- Expand the prevention toolkit - vaccine and biomedical prevention research.

- Invest in emerging and innovative testing and diagnostic technologies and approaches.

- Invest in research on novel therapeutic strategies and the biological mechanisms influencing predisposition to, or persistence of, STBBI, with a continued focus on a cure for HIV.

- Develop First Nations, Inuit and Métis health research capacity.

2.7 Measuring Impact - Monitoring and Reporting on Trends and Results

The Government of Canada's commitment to results for Canadians is served by regular assessment and reporting on the impact of our actions. This information results in dialogue on areas of strength and weakness and inspires new ways of thinking about the challenges we face. It drives course corrections and reveals gaps that need attention to keep us on track to achieve our objectives.

Canada has endorsed a set of global targets for HIV, hepatitis B and C, syphilis, gonorrhea and human papillomavirus for 2020 and 2030 (Annex A). But global targets are not sufficient. Made in Canada targets and indicators are necessary to drive our domestic actions and unify us in our commitment to specific results. We have heard the call from our partners to put targets and indicators in place without delay. We will do this in collaboration with these partners, reflecting the importance of establishing relevant targets and indicators that will fulfil their fundamental purpose of pushing us to do better.

We are committed to respecting the principles of ownership, control, access and possession while implementing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's call to action #19. Action #19 calls on the federal government, in consultation with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples, to establish measurable goals to identify and close the gaps in health outcomes between First Nations, Inuit and Métis and non-Indigenous communities, and to report on progress and assess long term-trends.

The Government of Canada will work with provincial and territorial governments, First Nations, Inuit and Métis partners, people with lived experience, community-based organizations, care providers and researchers, to develop domestic STBBI targets and an indicator framework that monitors our progress and results as we implement the STBBI Action Plan.

Access to reliable data is a prerequisite for developing indicators that tell us how we are doing in achieving our targets. Canada's STBBI surveillance system is a collaborative initiative of federal, provincial and territorial governments. It helps us understand where new infections are occurring, among which populations, the behavioural and social factors that increase risk, the impact of antimicrobial resistance and the populations that remain undiagnosed. Gaps in surveillance can limit the deployment of targeted and tailored approaches to reach populations most at risk and those still undiagnosed. These data gaps affect indicator development, monitoring and progress reporting. Federal, provincial and territorial governments have made a commitment to work together to strengthen STBBI surveillance as a priority.

Throughout the implementation of the STBBI Action Plan we will publically report Footnote † on our progress annually. We will adjust our efforts as necessary to support continued progress.

The Government of Canada will:

- Develop Canada's STBBI targets and indicators with our partners.

- Strengthen national surveillance systems to provide necessary data.

- Report on progress annually.

3. Creating conditions for successful implementation

The specific priorities in this Action Plan will be underpinned by our guiding principles (Annex B) and advanced through broader government policy and initiatives that create the conditions for their successful implementation.

The Government of Canada is committed to building a country where everyone's rights and freedoms are respected and where people are free and safe to be themselves. We have made gender equality a fundamental principle of our policies and programs. Sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression should not be a source of disparity or a barrier to better health outcomes. We have committed to implementing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Calls to Action to advance the process of reconciliation with First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples. These same values commit us to eliminating racism, discrimination and other forms of oppression, whether on the basis of colour, culture, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression in the form of homophobia, biphobia and transphobia. We value our differences and our diversity and believe they are our strength.

Federal partners in the STBBI Action Plan: Public Health Agency of Canada; Canadian Institutes of Health Research; Health Canada; Indigenous Services Canada; Correctional Service Canada; Department of National Defence; Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada; Department for Women and Gender Equality; LGBTQ2 Secretariat of the Privy Council Office; Department of Justice

We understand that social, economic and structural barriers in our society can impede Canada's efforts to reach the strategic goals of the Pan-Canadian STBBI Framework for Action. STBBI do not impact all people equally due to social, economic and other factors. We believe in a whole-of-government approach, through which the specific commitments in this STBBI Action Plan are enabled by the Government of Canada's social and economic policies and programs in areas like skills and training; poverty reduction; immigration; health; youth; seniors and aging; justice; and gender equity.

We have much to build on as we implement this Action Plan with our partners. Dedicated federal STBBI investments of $81.5 million annually remain foundational to our work. Recent investments, including $35 million over the next 5 years for the Harm Reduction Fund, more than $48 million for STBBI programs and services for First Nations and Inuit, and $5 million under the Public Health Agency of Canada's new Innovative Diagnostics Program will also support the commitments of this Action Plan over the next five years.

4. Conclusion

The success of the Government of Canada's STBBI Action Plan lies in the strength of our partnerships. We are committed to implementing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Calls to Action, and to continue efforts to renew the nation-to-nation, Inuit-Crown, and government-to-government relationships. We are committed to working with people with lived experience to guide our initiatives. It is through our collaborative work with provinces and territories that we will achieve alignment and leverage investments for greatest impact. The community-based movement remains a critical partner in achieving the strategic goals set out in Reducing the Health Impact of Sexually Transmitted and Blood-Borne Infections (STBBI) in Canada by 2030: A Pan-Canadian Framework for Action. Expanding our partnerships will allow us to draw on the talents and expertise of even more organizations as we move forward. Everyone in Canada will benefit from this enhanced coordination and collaborative spirit as we find ways to make our investments go further to accelerate our response to HIV, viral hepatitis and other sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections in Canada.

Glossary of terms

- Antimicrobial resistance

- The ability of microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites, to evolve in ways that reduce or eliminate the effectiveness of antimicrobial medicines (e.g. antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals and antiparasitics).

- Biphobia

- Discomfort, dislike, prejudice, or discrimination towards people who are, or who are perceived to be, bisexual.

- Care systems

- The organization of people, institutions, and resources that provide healthcare to meet the health needs of target populations.

- Civil society

- A community of individuals linked by common interests and collective activity, distinct from government or business.

- Combination prevention

- A set of strategically-selected interventions that match the needs of an individual or community. Evidence-based, mutually reinforcing biomedical, behavioral, and structural interventions are combined (e.g., sexual health education, vaccination, using condoms, taking PrEP, getting tested for STBBI regularly and achieving an undetectable viral load), to have the greatest sustained impact on reducing new infections.

- Community-readiness

- The degree to which a community can mobilize around a specific health issue. Readiness can range from none at all, in which the community has never heard of the issue in question, to already having successful programs and resources in place and making progress towards addressing the health issue.

- Culturally-responsive

- The ability to learn, understand and respectfully relate with people of your own culture as well as those from other cultures with differing traditions, values and belief systems. This includes people from marginalized and minority communities.

- Culturally-safe

- An environment where an individual feels physically, emotionally, socially, and spiritually safe in the absence of challenges or a denial of their experiences, identities and needs.

- Discrimination

- The unjust or prejudicial treatment of different categories of people, often on the grounds of race, gender expression, sexual orientation, age or disability.

- Dried Blood Spot (DBS) testing

- A process that collects drops of blood on filter paper for transport to a laboratory for testing. It facilitates access to testing through its ease of use.

- Endemic

- A disease, such as HIV or hepatitis C, that is regularly found among a particular group of people or in a certain area.

- Gender equality

- The state in which access to rights, responsibilities and opportunities across social, political, economic, and ideological contexts are unaffected by gender, including for trans and non-binary communities.

- Gender identity

- A person's internal and individual sense and experience of being a particular gender, which may or may not correspond with their sex assigned at birth.

- Gender expression

- How a person externally presents their gender, which can include behaviour and/or outward appearance, such as dress, hair, make-up, body language and voice. A person's chosen name and pronoun are also common ways of expressing gender.

- Harm reduction

- A pragmatic and evidence-informed public health approach to potentially injurious behaviour that seeks to prevent injury, disease transmission and death while not seeking to eliminate the behaviour itself. In the context of substance use, harm reduction aims to reduce the negative health, social and economic impacts of substance use on individuals, their families and communities, without requiring abstinence. It acknowledges the central role of people who use drugs in program development and aims to improve people's health and help them to make connections with important health and social services, including treatment.

- Health equity lens

- A process of understanding and examining unfair, avoidable, and remediable differences in the health status of specific populations in an attempt to resolve barriers to health and healthcare and ensure that everyone has a fair opportunity to attain their full health potential based on their unique and individual health needs.

- Homophobia

- Discomfort, dislike, prejudice, or discrimination towards people who are, or who are perceived to be, gay, lesbian or queer.

- Human rights-based approach

- A human rights-based approach recognizes that all individuals are equal before and under the law and have the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination, consistent with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the international human rights treaties to which Canada is a party.

- Implementation science

- The study of methods and strategies to promote the uptake of research findings and interventions that have proven effective into routine practice to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services, with the aim of improving population health.

- Integrated approach

- Addresses the interrelated nature of risk factors and transmission routes for STBBI by implementing strategies that target the common features of STBBI to reduce disease-specific siloes.

- Key populations

- Groups of people who are particularly vulnerable to acquiring STBBI due to higher likelihood of exposure as well as systemic barriers that may lead to higher-risk behaviours.

- Knowledge creation

- The continuous formation, combination, transfer, and conversion of new and different kinds of knowledge. This occurs as individuals interact, practice and learn in order to create novel ideas.

- LGBTQ2

- This acronym is a term commonly used to refer to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, Two-Spirit, and other emerging identity populations.

- Life-course approach

- A multidisciplinary approach to understanding the physical, mental, and social health of an individual's health trajectory through incorporating life span and life stage concepts.

- Phylogenetic analysis

- The study of the evolutionary genetic relationship between members of a species.

- Point-of-Care Testing (POCT)

- A form of diagnostic testing that is performed outside a clinical laboratory at the time and place a person is receiving care.

- Post-exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

- An HIV prevention strategy in which a person who does not have HIV takes antiretroviral medicines after being potentially exposed to HIV to reduce their risk of becoming infected.

- Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)

- An HIV prevention strategy in which a person who does not have HIV takes antiretroviral medications on an ongoing basis, starting before being exposed to HIV and continuing afterwards for as long as they are exposed to reduce the possibility of infection.

- Racism

- A belief or doctrine that a person's social and innate capabilities are predetermined by their race and also usually involving the idea that one's own race is superior and has the right to rule over all other races or one in particular.

- Reconciliation

- Policies and programs developed by and with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples through a relationship grounded in mutual respect and rooted in an understanding and recognition of, and responsiveness to, the ongoing impacts of colonization, health and social consequences of residential schools, structural inequities, and systemic racism.

- Self-testing

- Encompasses a wide range of testing procedures and technologies where a person collects their own sample (e.g. oral fluid, urine, or blood) instead of a healthcare provider. The collection of the sample often occurs in a private setting, such as a person's home (also referred to as home testing). The sample is then used to test for an STBBI either on the spot or by mail to a laboratory for diagnostics.

- Sex and Gender-based Analysis (SGBA+)

- An analytical tool that systematically examines potential impacts of policies, programs and services on diverse groups of women, men, boys, girls, gender-diverse, and non-binary people. The "plus" acknowledges that SGBA goes beyond sex and gender differences. There are many other identity factors that intersect to make us who we are; SGBA+ therefore also considers factors such as race, ethnicity, religion, age, and mental or physical disability.

- Sexual orientation

- A person's emotional, romantic and/or sexual attraction towards other people defined within the context of their own gender identity. Sexual orientations are broadly but not exclusively subsumed under heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, and asexual.

- Sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBI)

- Sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBI) are infections that are either sexually transmitted or transmitted through blood. These include, but are not limited to: human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV), chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and human papilloma virus (HPV).

- Stigma

- Shame, disgrace or disapproval, which results in a process of devaluation and exclusion where an individual is rejected, discriminated against, and excluded from participating in a number of different areas of society.

- Surveillance

- Tracking and forecasting health events and determinants through the collection, analysis and reporting of data.

- Systemic barriers

- Policies, practices, procedures, or behaviours that result in disadvantages for some people who in turn receive unequal access to services and resources or are excluded altogether.

- Transphobia

- Discomfort, dislike, prejudice, or discrimination towards people who are, or who are perceived to be, trans.

- Trauma-informed

- A strengths-based approach that considers the whole person, including their past trauma(s) (e.g. sexual assault, intergenerational trauma, medical trauma, etc.), in designing and delivering services and programs.

- Treatment as Prevention

- A highly effective strategy to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV by providing people living with HIV effective antiretroviral therapy, and helping them to maintain an undetectable viral load.

- Two-spirit

- Refers to a person who identifies as having both a masculine and a feminine spirit, and is used by some Indigenous people to describe their sexual, gender and/or spiritual identity. For some, two-spiritedness is more than just an identity, it is a traditional role that some Indigenous people now embody in their modern lives.

- Prevention, testing and treatment cascade

- A way of conceptualizing the care and support required to prevent STBBI transmission and to support and treat people living with an STBBI by describing what is needed in order to achieve optimal health outcomes, including prevention, testing and diagnosis, linkage to appropriate medical care (and other health services), support while in care, access to treatment if and when the individual is ready, and support on treatment. The cascade assesses how well care systems are operating and can identify weaknesses at different stages or unacceptable variations among different groups or communities.

- Undetectable = Untransmittable (U=U)

- People living with HIV infection who maintain an undetectable viral load through treatment cannot sexually transmit the virus to others

- Undetectable viral load

- Viral load refers to how many copies of HIV are present in a milliliter sample of blood. When copies of HIV cannot be detected by standard viral load tests, a person living with HIV is said to have an "undetectable viral load." An 'undetectable' diagnosis means that the level of HIV in the body is so low (under 40-50 copies/mL) that it is non-infectious to other people. Another term, 'viral suppression', is when HIV levels are under 200 copies/mL.

- Undiagnosed

- People who are living with a STBBI but have not yet been diagnosed and are therefore unaware of their status.

- Vertical transmission

- The passage of an infection (e.g. HIV, syphilis) from mother to baby during pregnancy, childbirth or after birth. Transmission might occur across the placenta, in the breast milk, or through direct contact during or after birth.

- Whole-of-government approach

- Joint activities performed by diverse ministries, public administrations and public agencies in order to provide a common solution to a particular problem or issue.

Annex A: Global Targets for STBBI

HIV

By 2020:

- 90% of people living with HIV know their status

- 90% of people living with HIV who know their status are receiving treatment

- 90% of people on treatment have suppressed viral loads

- Fewer than 500,000 new HIV infections

- Elimination of HIV-related discrimination

By 2030:

- Zero new HIV infections

- Zero AIDS-related deaths

- Zero discrimination

Hepatitis

By 2020:

- 30% reduction in new cases of chronic viral hepatitis B and C infections

- 10% reduction in hepatitis B and C deaths

- 30% of viral hepatitis B and C infections are diagnosed

- 5 million people receiving hepatitis B treatment, and 3 million people receiving hepatitis C treatment