COVID-19 population-based analysis of the 2020–2021 school year in Saskatchewan

Download this article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 48-9, September 2022: Invasive Diseases Surveillance in Canada

Date published: September 2022

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 48-9, September 2022: Invasive Diseases Surveillance in Canada

Surveillance

In-person learning low risk for COVID-19 acquisition: Findings from a population-based analysis of the 2020–2021 school year in Saskatchewan, Canada

Molly Trecker1, Leanne McLean1, Stephanie Konrad2, Dharma Yalamanchili3, Kristi Langhorst1, Maureen Anderson4

Affiliations

1 Saskatchewan Health Authority, Saskatoon, SK

2 Indigenous Services Canada Saskatchewan Region, Regina, SK

3 Northern Inter-Tribal Health Authority, Prince Albert, SK

4 Department of Community Health and Epidemiology, College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Trecker MA, McLean L, Konrad S, Yalamanchili DT, Langhorst K, Anderson M. In-person learning low risk for COVID-19 acquisition: Findings from a population-based analysis of the 2020–2021 school year in Saskatchewan, Canada. Can Commun Dis Rep 2022;48(9):415–9. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v48i09a06

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, school, COVID-19 transmission, Saskatchewan

Abstract

Background: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused substantial disruption to in-person learning, often interfering with the social and educational experience of children and youth across North America, and frequently impacting the greater community by limiting the ability of parents and caregivers to work outside the home. Real-world evidence related to the risk of COVID-19 transmission in school settings can help inform decisions around initiating, continuing, or suspending in-person learning.

Methods: We analyzed routinely collected case-based surveillance data from Saskatchewan’s electronic integrated public health system, Panorama, from the 2020–2021 school year, spanning various phases of the pandemic (including the Alpha variant wave), to better understand the risk of in-school transmission of COVID-19 in Saskatchewan schools.

Results: The majority (over 80%) of school-associated COVID-19 infections were acquired outside the school setting. This finding suggests that the non-pharmaceutical measures in place (including masking, distancing, enhanced hygiene, and cohorting) worked to limit viral spread in schools.

Conclusion: Implementation of such control measures may play an essential role in allowing children and youth to safely maintain in-person learning during the pandemic.

Introduction

Since the start of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in North America, the question of whether schools can safely operate in-person has been the focus of much debate. Schools were frequently included in widespread shutdowns to limit viral transmission and exponential growth, despite a lack of evidence related to their role in transmission. Stakeholders, including parents, educators, public health professionals, and the media, have presented many differing viewpoints on the risks/benefits of in-person learning during the pandemic. The issue remains at the forefront during the third school year affected by COVID-19.

Prior to start of the 2020–2021 school year, there was little real-world evidence related to in-person learning and the risk of COVID-19 transmission. Evidence has been emerging since that time, however, and we now have a better understanding of COVID-19 transmission dynamics in schools in a variety of geographic settingsFootnote 1Footnote 2Footnote 3Footnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 7Footnote 8Footnote 9Footnote 10. Several of these studies have found that with appropriate mitigation measures in place (such as cohorting, distancing, or masking), the risk of in-school transmission was relatively low. A study of 17 rural Wisconsin schools found that of COVID-19 cases identified among students, only 3.7% were acquired in the school settingFootnote 2. One report of a large outbreak in a Jerusalem high school concluded that crowded classrooms, the suspension of masking requirements (due to a heatwave), and continuous air conditioning were factors that substantially increased transmission. However, attack rates among students and staff were still relatively low at 13.2% and 16.6%Footnote 4. Data from British Columbia found a similar proportion of overall school-associated cases were likely acquired in school (13.0%)Footnote 8. Another British Columbia study reported that in-person schooling was not associated with an increased risk of COVID-19 acquisition among school staffFootnote 1, and other Canadian and United States studies have reported relatively low risk associated with in-person schooling as wellFootnote 6Footnote 9. Here we present the characteristics of cases and risk of transmission of COVID-19 in preschools, elementary, and high schools in Saskatchewan, a jurisdiction that largely maintained in-person learning throughout the 2020–2021 school year.

Methods

We analyzed population-level data from the 2020–2021 school year in Saskatchewan, spanning various phases of the pandemic (including the Alpha variant wave), to better understand the risk of in-school transmission of COVID-19 in Saskatchewan schools.

Routinely collected case-based surveillance data from Saskatchewan’s electronic integrated public health system, Panorama, were used for the analysis. Data on all laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases were entered in Panorama, and standardized data collection worksheets are used for case and contact investigations. These surveillance data were used to better understand the epidemiology of COVID-19, including case volumes over time, demographics and case type (e.g. staff versus student), and most likely exposure sources for cases.

The study period for the 2020–2021 school year was from September 2, 2020 (start of school year) to July 12, 2021 (approximately two weeks post the end of the school year). Data were extracted on July 13, 2021, and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 and Microsoft Excel 2016. This analysis represents a synthesis of province-wide data from the full 2020–2021 school year; similar analyses were conducted throughout the school year at the local and provincial level and were used to inform decisions around maintaining in-person learning.

“School-associated” cases were identified using risk factor variables routinely collected during case investigations that indicate whether a person was a teacher, a preschool attendee, a school attendee (e.g. K–12) or other school staff. We included only those school-associated cases that had a most likely source (MLS) of exposure flagged in Panorama, which is also routinely collected during case interviews, as determined by trained case investigators, who are typically public health nursing staff. The determination is based on a thorough retrospective investigation, taking into account the incubation period of the organism, period of communicability, and all potential exposure settings during the relevant time period for acquisition. Ultimately the investigator makes the determination of which reported exposure is the most likely source of infection.

Results

From September 3, 2020, through July 12, 2021, a total of 5,952 school-associated cases occurred in Saskatchewan. Among these, 4,980 (83.7%) had MLS data available; this analysis is based on those 4,980 cases. Of these cases, the largest proportion occurred among children aged 5–13 years (n=2,336, 46.9%), followed by youth aged 14–19 years (n=1,470, 29.5%). Other age groups made up substantially smaller proportions of the overall caseload (Table 1).

| Age group (years) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0–4 | 199 | 4.0% |

| 5–13 | 2,336 | 46.9% |

| 14–19 | 1,470 | 29.5% |

| 20–44 | 586 | 11.8% |

| 45–64 | 368 | 7.4% |

| 65+ | 21 | 0.4% |

| Total | 4,980 | 100% |

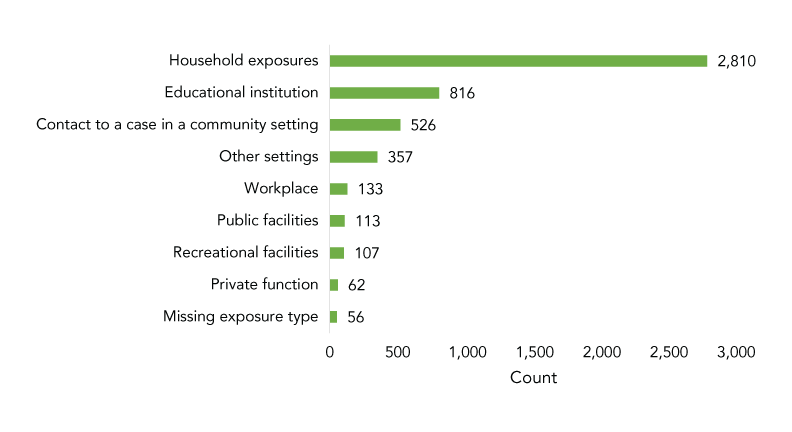

By category, the majority of cases (n=3,853, 77.4%) were among elementary/high school students, with smaller proportions comprising teachers (n=491, 9.9%), other school staff (n=420, 8.4%), and preschool students (n=216, 4.3%). Teachers had the highest proportion of in-school exposures (n=112, 22.8%), followed by elementary/high school students (n=614, 15.9%), other school staff (n=65, 15.5%), and preschool students (n=25, 11.6%) (Table 2). Throughout the academic year, 816 (16.4%) school-associated cases were found to have acquired their infection in the school, with household exposure (n=2,810, 56.4%) being responsible for the majority of infections (Figure 1).

| Case type | Total cases | Total school acquired within case type category | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Elementary/High school student | 3,853 | 77.4% | 614 | 15.9% |

| Teacher | 491 | 9.9% | 112 | 22.8% |

| Other school staff | 420 | 8.4% | 65 | 15.5% |

| Preschool student | 216 | 4.3% | 25 | 11.6% |

| Total | 4,980 | 100% | 816 | 16.4% |

Figure 1: School-associated COVID-19 cases, by exposure setting, Saskatchewan, September 3, 2020–July 10, 2021 (N=4,980)

Text description: Figure 1

| Most likely source exposure type | Total cases |

|---|---|

| Household exposures | 2,810 |

| Educational institution | 816 |

| Contact to a case in a community setting | 526 |

| Other settings | 357 |

| Workplace | 133 |

| Public facilities | 113 |

| Recreational facilities | 107 |

| Private function | 62 |

| Missing exposure type | 56 |

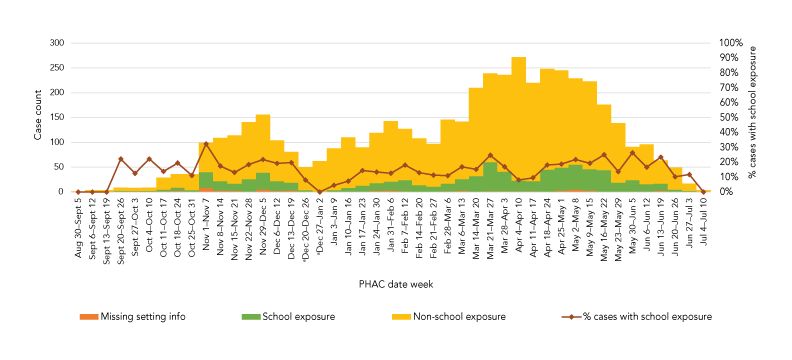

The epidemic curve of school-associated COVID-19 cases during the 2020–2021 school year (Figure 2) illustrates that while the volume of school-associated cases (height of the bars) varied throughout the time period, the proportion of infections acquired in school (green portion of the bars, also shown as a percent by the red line) remained relatively stable throughout the period. Of note, the Alpha variant was first identified in Saskatchewan in February 2021, and led to a subsequent surge in infections by mid-March. This surge was clearly reflected among school-associated cases on the epidemic curve, beginning the week of March 14–20; however, the overall proportion of cases attributed to in-school exposure remained relatively steady throughout this surge in cases.

Figure 2: Epidemic curve, school-associated COVID-19 cases, by week and exposure setting, September 3, 2020–July 10, 2021 (N=4,980)Figure 2 footnote a

Text description: Figure 2

This graph shows the epidemic curve of school-associated COVID-19 cases, by week, from September 3, 2020 through July 10, 2021. The volume of cases fluctuated throughout the year, with lows in September and June, and peaked during the Alpha wave in the spring of 2021. Throughout the time period, the proportion of cases attributed to in-school exposure varied from 0.0% to 32.3%, but overall remained relatively steady over the time period at under 20%.

Discussion

Unlike many North American jurisdictions, schools in Saskatchewan began the 2020–2021 school year offering in-person learning; students and parents were also provided with an alternative option to choose online learning if desired. While there was some regional variation throughout the school year, for the most part, Saskatchewan maintained in-person learning for all grades from K–12 for the duration of the academic year. Temporary exceptions did occur based on local epidemiology; for example, rural versus urban areas and northern versus central/southern areas may have had different protocols at different times. Additionally, individual schools in the province had the option to temporarily move to online learning, based on local epidemiology, when needed. The Saskatchewan Ministry of Education provided school divisions four “Levels” of learning based on local risk assessment/epidemiology: Level 1 indicated “normal” return to school, Level 2 required continuous mask use by all students and staff, Level 3 included cohorting and hybrid (mixed online/in person) learning modules (to allow for smaller class sizes), and Level 4 indicated mandatory online learning school-wide. Most schools in Saskatchewan operated at Level 2 or Level 3 for the majority of the academic year, with some temporarily (10–14 days) moving to Level 4 following the declaration of a school outbreak or based on other local risk assessments. It was more common for larger schools and upper grades to operate at Level 3 compared with elementary gradesFootnote 11.

Overall, with temporary regional variation as mentioned, the non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) in place included non-medical masking for students and staff, enhanced environmental cleaning and personal hygiene, physical distancing where possible, the suspension of youth recreational sports, symptom screening and stay home policies, universal access to testing, and cohorting of students in some schools. Contact tracing of each school-associated case was guided by a risk assessment matrixFootnote 12Footnote 13, which led to identification and exclusion/quarantine of close contacts in the school setting.

The majority (over 80%) of school-associated COVID-19 cases during the study period were found to have been acquired outside the school setting. This suggests that the non-pharmaceutical measures in place (including masking, distancing, enhanced hygiene and cohorting) worked to limit viral spread in schools.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this analysis. First, this study included only cases that were tested and subsequently diagnosed. Asymptomatic school-associated cases that were not tested would not be included in Panorama, which relies on a positive laboratory result to confirm a case. Second, inadvertent inclusion of post-secondary students may have occurred in situations where incorrect risk factors were chosen. It is also possible that students from congregate living settings (boarding schools) were also inadvertently included, which would overestimate total school-associated cases, and likely in-school exposures as well. Third, the true burden of in-school acquisition may also have been underestimated given many schools temporarily moved to Level 4 learning (online) following the declaration of a school-associated outbreak or other risk assessment; however, we would argue this is further evidence that the measures taken in schools to limit and control viral transmission, including temporary shifts to online learning when required, worked. Further, our findings demonstrate these ”school-associated” index cases, which may have triggered Level 4 learning, usually did not acquire their infection in school, but in households, social gatherings, and other outside-school activities. Fourth, is also important to note this study period occurred prior to the emergence and widespread circulation of the Delta and Omicron variants. Because these variants are more transmissible, findings may not be generalizable to the context of the pandemic in the later part of 2021 and into 2022. Fifth, we were also unable to assess the impact of ventilation on limiting disease spread. Lastly, only cases with MLS information were included in the analysis. Completeness of data varied by geographic area and over time; however, over the time period and across the province, 83.7% of cases had MLS information available.

Conclusion

Our finding that the proportion of school-associated COVID-19 cases attributed to in-school exposure was low and remained stable throughout the school year despite an overall surge in cases in spring 2021, is consistent with data from other jurisdictions Footnote 1Footnote 2Footnote 4Footnote 6Footnote 8Footnote 10. These studies imply that the NPIs in place in school settings likely contributed to limiting disease transmission. Compared with many community settings, Saskatchewan schools were a relatively controlled environment during the 2020–2021 school year. As we move into the immunization era, with a safe and effective pharmaceutical intervention available, we expect that immunization of age-eligible individuals in schools will contribute to reducing transmission. Even in this new era, however, given high background community transmission rates, the potential for breakthrough infections, and variable vaccination coverage rates among children and youth, NPIs remain important interventions in schools. While it is possible the arrival of new variants and the faster rate of viral spread will change the epidemiological picture, our findings contribute to the larger body of evidence that to date suggests in-person learning is not a substantial contributor to COVID-19 transmission when appropriate NPIs are in place.

Authors’ statement

- MT — Writing–original draft, writing–review & editing, data analysis, conceptualization, visualization, interpretation

- LM — Writing–review & editing, conceptualization, visualization, interpretation

- SK — Writing–review & editing, conceptualization, visualization, interpretation

- DY — Writing–review & editing, conceptualization, visualization, interpretation

- KL — Writing–review & editing, data preparation and synthesis

- MA — Writing–review & editing, conceptualization, interpretation

The content and view expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

Competing interests

None.

Funding

This work was supported by the Saskatchewan Health Authority, Indigenous Services Canada–Saskatchewan Region, and the Northern Inter-Tribal Health Authority.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the feedback provided by the following individuals, regarding the approach to analyzing epidemiology of COVID-19 in schools: J Wright, J Marko, B Quinn, T Dunlop, L Murphy, S Gupta, M Andkhoie and O Oluwole.