Evaluating Canada’s initiative of enhanced screening for tuberculosis infection in migrants

Download this article as a PDF (255 KB)

Download this article as a PDF (255 KB)Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 51-10/11/12, October/November/December 2025: Tuberculosis and Migration in Canada

Date published: December 2025

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 51-10/11/12, October/November/December 2025: Tuberculosis and Migration in Canada

Implementation Science

Evaluating Canada’s initiative of enhanced screening for tuberculosis infection in migrants: Implementation lessons from Alberta

Courtney Heffernan1, Abdul Jamro2, Mary Lou Egedahl1, Richard Long1,2

Affiliations

1 Tuberculosis Program Evaluation and Research Unit, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB

2 School of Public Health, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Heffernan C, Jamro A, Egedahl ML, Long R. Evaluating Canada’s initiative of enhanced screening for tuberculosis infection in migrants: Implementation lessons from Alberta. Can Commun Dis Rep 2025;51(10/11/12):381–8. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v51i101112a02

Keywords: tuberculosis, surveillance, incidence rate, migrants, screening, evaluation, implementation

Abstract

Background: The domestic tuberculosis (TB) disease burden in high-income, low TB-incidence countries is largely driven by the reactivation of remotely acquired TB infections (TBIs) in people born outside the country (PBOC). In Canada, PBOC now accounts for more than three quarters of annual active TB diagnoses. To prevent some of this disease experience, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) rolled out a new TBI screening initiative in 2019.

Objective: An evaluation of TB outcomes among individuals referred through this initiative between May 2019 and May 2023 in Alberta, Canada.

Methods: Inclusion criteria for this initiative are migrants who are required to undergo an immigration medical exam with at least one of HIV/AIDS, solid organ transplant, end-stage renal disease, recent close TB contact (within five years), and past head and neck cancer. Those with a positive screening test for TBI are referred directly to TB services in the stated province/territory of landing for assessment and treatment.

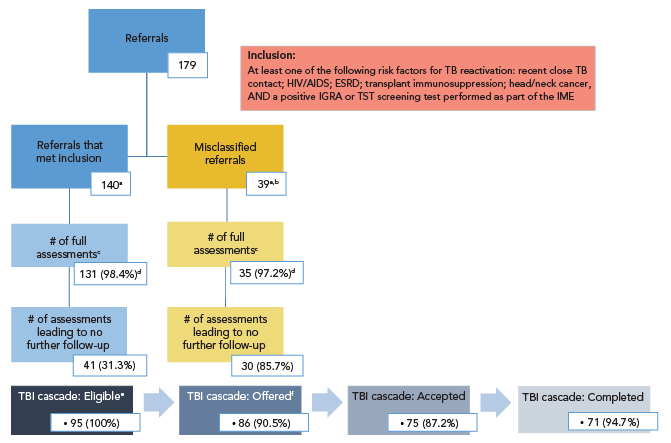

Results: Over four years, 179 referrals were made to Alberta. No one referred through the program and offered treatment developed active TB. Overall, 95 individuals were considered suitable candidates for prevention, among whom 87% accepted. Completion was high at nearly 95%. Inefficiencies included 113 individuals undergoing repeated TBI testing locally, 39 (21.8%) referrals not meeting the inclusion criteria, and 61 (34.1%) individuals being rereferred despite being past patients of Alberta TB services.

Conclusion: Our findings highlight that, in Alberta, IRCC’s new TBI screening initiative was highly successful in connecting referred individuals to TB services. The initiative experienced some inefficiencies and we describe areas where it could be improved.

Introduction

Despite being preventable and curable, in 2023, 10.8 million people fell ill with tuberculosis (TB) disease worldwide and 1.25 million succumbed to its effects Footnote 1. Tuberculosis has traditionally been conceived as existing in a binary of TB infection (TBI) and TB disease (TBD), with the former being neither contagious nor symptomatic but requisite to developing TBD Footnote 2. The global prevalence of TBI is estimated at 25%, but only 5%–10% of those infected will progress to disease Footnote 3. Progression risk is highest among people who have been recently infected, have immune compromising conditions, or are in poor general health, including from undernutrition Footnote 4. As a result, TBD proliferates in places where the health and social welfare needs of most citizens are largely unmet, as in low- and middle-income countries. Meanwhile, in high-income countries, the majority of TBD is experienced by people born outside the country (PBOC), with most resulting from reactivation of remotely acquired infections Footnote 5.

Canada has a rate of TBD that is among the lowest in the world, but which has hovered at approximately five per 100,000 population from 2000 to present Footnote 6. In part, this may be because in 2016, the decades long shift from people arriving from countries of Western Europe with a low TB burden to people arriving from countries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America with intermediate and high TB incidence was at a nearly 30/70 split, while the absolute number of migrants have been increasing rapidly since Footnote 7Footnote 8Footnote 9Footnote 10. By 2019, PBOC made up 74% of all people affected by TB nationally, see Figure 1. Such considerations imply that the immigration pathways are ideal settings for TBI screening with positive impacts to both the individual and public.

Figure 1: Descriptive text

The graph shows the number of Canadian-born and people born outside the country (PBOC) individuals with tuberculosis (TB) and the corresponding rate per 100,000 people in Canada between 2000 to 2022. The figure has a vertical bar graph where the bar color is split each year into orange (which represents the number of PBOC individuals diagnosed with TB) and blue (number of Canadian-born individuals diagnosed with TB) corresponding to the values listed on the left side of the bar graph. The number of Canadian-born individuals with TB has remained steady between 2000 to 2020, with case counts ranging from 434 to 578. The number of PBOC diagnosed with TB has risen steadily from 2000 to 2022, with case counts ranging from 1,133 in 2000 to 1,475 in 2022. In 2009, the case numbers reached their highest level among Canadian-born individuals at 578 and dropped 434 by 2022 while case numbers among PBOC went down in 2021 before reaching their highest level in 2022 at 1,475 cases. Above the bars is a light blue line which shows the overall incidence rate of TB in Canada per 100,000 people, which corresponds to the scale on the right side of the graph. The incidence rate gradually decreased between 2000 to 2015, with the rate ranging from 5.6 cases per 100,000 people in 2000 to 4.6 cases per 100,000 people in 2014. Since then the rate has increased from 4.6 cases per 100,000 people in 2015 to 5.1 cases per 100,000 people by 2022.

Canada has high levels of immigration, having welcomed 437,000 new permanent residents in 2022 Footnote 11. In light of the ostensible TB prevention gap among PBOC to Canada, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) introduced a federal program of enhanced screening for TBI in 2019 as an add-on to their existing medical surveillance program for TBD. Prior to the introduction of this initiative, the immigration focus was on finding active TBD, including domestic post-landing medical surveillance for TB among those with abnormal chest X-rays or past history of TB Footnote 12. This article describes TB outcomes among individuals referred by this new, systematic TBI screening initiative between May 2019 and May 2023 to the province of Alberta, where net international migration is a major component of population growth and the majority of TBD is diagnosed among PBOC Footnote 13Footnote 14. The top three countries of birth of newcomers to Alberta are Philippines, India, and Nigeria, with corresponding rates of TB ranging from 199 to 638 cases per 100,000 people (Figure 2) Footnote 15. In 2021, 241 people in Alberta had TBD, with a corresponding crude rate of 5.4 per 100,000 population Footnote 6.

Figure 2: Descriptive text

The graph shows the count of Alberta’s population from 1981 to 2023 broken down by Canadian-born and people born outside the country (PBOC) as well as the proportion of the population who are PBOC. The figure has a vertical bar graph where the bar color is split each year into red (population of Alberta who are PBOC) and light blue (Canadian-born) corresponding to the population counts scale listed on the left side of the bar graph. Above the bars is a doted red line showing the proportion of Alberta’s population made up of PBOC corresponding to the scale on the right side of the graph. The total population of Alberta has increased from approximately 2.2 million in 1981 to approximately 4.3 million by 2023. The number of people who are Canadian-born has slowly increased from approximately 1.8 million in 1981 to 3.3 million by 2023. The number of PBOC has increased substantially from 1981 to 2023, with the count going from approximately 360,000 in 1981 to over one million in 2023. The proportion of the population who are PBOC has increased from 1981 to 2023, with the proportion rising from 16.3% in 1981 t0 23.5% by 2023.

Table 1 shows the top countries of origin of new arrivals to Alberta from 2016–2021. Table 2 shows the top five countries of origin and five-year average TB incidence in those countries for PBOC diagnosed with TB in Alberta from 2016–2021 during which time a total of 1,248 people were diagnosed with TB.

| Country | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Philippines | 47,605 (24.6) |

| India | 31,810 (16.5) |

| Nigeria | 9,840 (5.1) |

| China | 9,495 (4.9) |

| Syria | 7,300 (3.8) |

| Total in Alberta | 193,130 (100.0) |

| Country | n (%) | Average five year incidence |

|---|---|---|

| Philippines | 414 (33.2) | 577/100,000 |

| India | 255 (20.4) | 201/100,000 |

| Ethiopia | 79 (6.9) | 133/100,000 |

| Somalia | 74 (5.3) | 254/100,000 |

| Vietnam | 31 (2.5) | 174/100,000 |

Methods

The enhanced TBI screening initiative for migrants focuses on TBI-test-positive individuals at high risk of reactivation who would benefit from TB preventive therapy (TPT). Individuals coming from select countries are required to complete an immigration medical exam (IME) to evaluate their health in order to be admissible to Canada Footnote 16. All permanent residents and some temporary resident applicants are required to complete an IME. After screening, applicants who can be part of this intervention must have a complete IME with at least one high-risk medical condition for TB reactivation (HIV/AIDS and have a solid organ transplant, end-stage renal disease, recent close TB contact within five years, and head and neck cancer) together with either a positive interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) or Tuberculin Skin Test (TST) Footnote 17. The IRCC notifies provincial or territorial public health authorities of these individuals so that they can arrange assessment for TPT. A letter is also provided at the port of entry to applicants whose IME was performed overseas directing them to follow up with TB services in their intended province/territory of residence within 30 days. As a result, health system contact can be initiated either by provincial/territorial TB services or by the individual. Assessment by a clinician or public health designated specialist is a condition of entry that can affect future eligibility of Canadian citizenship Footnote 12. For this reason, TB services and individual migrants assume mutual responsibility for medical surveillance of TB in Canada, and compliance is high.

Other high-income countries with low rates of TB in the general population, such as the United Kingdom Footnote 18, Australia Footnote 19Footnote 20, and the United States Footnote 21, run varied TB screening programs for inbound migrants to reduce imported prevalent TB infection and disease, as shown in Table 3. Compared to Canada, the governments of the United Kingdom, Australia, and especially the United States have more comprehensive TB screening programs for PBOC that emphasize prevention and involve more robust testing of persons arriving from high incidence countries. The initiative evaluated in this article is intended to lessen existing TB prevention gaps between Canada and other high-income countries.

| Characteristics | Canada | United Kingdom | Australia | United States |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target population | Individuals applying for permanent resident status and select temporary residents who require an IME Footnote 7. | Visa applicants aged ≥11 years, coming from countries with a TB rate of >40 per 100,000 and staying for ≥6 months Footnote 18. | Individuals applying for permanent resident status and select non-permanent residents who require an IME Footnote 19Footnote 20. | Immigrants, refugees, or other legal permanent residents Footnote 21. |

| Screening tests | Tests include physical examination, medical history, chest X-ray, and sputum for acid-fast bacilli smear and culture if indicated Footnote 7. | Tests include chest X-ray and symptom inquiry. Sputum for acid-fast bacilli smear and culture is required for those with a suggestive chest radiograph. | Tests include chest X-ray and symptom inquiry. Children aged >2 but <11 years coming from high-TB-incidence countries, which includes all those not categorized by WHO as low-TB risk, are required to complete an IGRA or TST. | Tests include physical examination, medical history, chest X-ray and sputum for acid-fast bacilli smear and culture if indicated. IGRA test for those aged ≥2–15 years, expanding in fall of 2024 to those aged >15 years, who come from high-TB-burden countries (defined by an incidence of ≥20 cases per 100,000). |

| Medical surveillance requirement | Past history of TB or abnormal chest X-ray, but no microbiological confirmation of disease which are required to report to a public health authority within 30 days of arrival. | Migrants arriving by unofficial routes are screened for active TB at the first point of contact with healthcare services. | Past history of TB or an abnormal chest X-ray but not microbiological confirmation of disease, which are required to report to public health within 28 days of arrival. | Panel physicians assign applicants into one of seven TB classifications with varying travel clearances: Those classified as A or B are referred to their local state health department for follow-up within 90 days of arrival. |

| Other screening | Selective TBI testing predates the 2019 enhanced program, and applies to individuals who intend to work, study or train in certain areas, including medicine and allied health Footnote 16. | TBI testing and treatment for recently arrived (within 5 years) PBOC aged 16–35 from countries with an incidence rate of 150 per 100,000 or greater Footnote 18. | Selective TBI testing of individuals aged ≥15 years, arriving from high TB-incidence countries who intend to work, study, or train in health care, aged care or disability care. | Refugees undergo domestic screening within 90 days of arrival to find TB disease that may have developed between an overseas IME and arrival to the United States. |

Abbreviations: IGRA, interferon-gamma release assay; IME, immigration medical exam; TB, tuberculosis; TBI, tuberculosis infection; TST, tuberculin skin test; WHO, World Health Organization Footnotes

|

||||

Implementation and effectiveness

Between 2019 and 2023, IRCC made 9,887 referrals to TB services in Alberta and between May 2019 and May 2023, with 179 or fewer than 2%, resulting from the enhanced TBI screening initiative. To describe the effectiveness of this initiative (i.e., its ability to connect eligible individuals to TB services for domestically delivered prevention), this study focused on TB outcomes. Data were extracted in a retrospective review of public health records to establish care cascades. Every referred individual had a one-year follow up to assess for development of TBD. The characteristics of individuals referred through this initiative are described in this article. Thereafter, to identify implementation challenges, the entire process is explored in detail, from application of screening inclusion to referral and subsequent stages of TB care in Alberta.

Results

Alberta TB services received 179 referrals through IRCC’s enhanced screening initiative, relating to 177 unique individuals over four years. Characteristics of individuals referred are shown in Table 4. The majority of IMEs were performed overseas compared to Canada (71.8% and 28.2%, respectively). Recent close contact of a TB case was the top reason for referral, followed by HIV/AIDS (46.9% and 35.6%, respectively). The majority of referred individuals were applying for permanent residence status (67.2%). Approximately 40% of the individuals referred through the program were coming from the Philippines. Overall, 87.6% of referred individuals came from the World Health Organization (WHO) designated, high-TB-burden countries Footnote 22. The IGRA was used to screen the majority of individuals, compared to TST (81.4% and 15.2%, respectively). Close to one-quarter of the results of the screening test were reported in the IME qualitatively.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Location of IME | |

| Overseas | 127 (71.8) |

| Canada | 50 (28.2) |

| Screening inclusion group | |

| Recent close TB contact (within five years) | 83 (46.9) |

| HIV/AIDS | 63 (35.6) |

| End-stage renal disease | 22 (12.4) |

| Previous head/neck cancer | 6 (3.4) |

| Previous organ/transplant recipient | 3 (1.7) |

| IME screening tool | |

| IGRA | 144 (81.4) |

| TST | 27 (15.2) |

| No test | 6 (3.4) |

| Reporting of results in IME (n=171) | |

| Quantitatively | 128 (74.9) |

| Qualitatively | 43 (25.1) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 90 (50.8) |

| Female | 87 (49.2) |

| Age group (years) | |

| 5–14 | 12 (6.8) |

| 15–35 | 73 (41.2) |

| 36–60 | 63 (35.6) |

| 60+ | 29 (16.4) |

| Immigration typeFootnote b | |

| Permanent resident | 119 (67.2) |

| Temporary resident | 57 (32.2) |

| Country of birth | |

| Philippines | 71 (40.1) |

| Ethiopia | 15 (8.5) |

| India | 15 (8.5) |

| Nigeria | 11 (6.2) |

| Other | 65 (36.7) |

| WHO region | |

| Western Pacific | 78 (44.1) |

| African | 59 (33.3) |

| South-Eastern Asia | 16 (9.0) |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 15 (8.5) |

| Region of the Americas | 8 (4.5) |

| European | 1 (0.6) |

| WHO high-burden countryFootnote c | |

| Yes | 155 (87.6) |

| No | 22 (12.4) |

Abbreviations: IGRA, interferon-gamma release assay; IME, immigration medical exam; TB, tuberculosis; TST, tuberculin skin test; WHO, World Health Organization Footnotes

|

|

No one referred through the program and offered treatment developed active TB, whether they accepted and completed treatment, declined, or discontinued, but one individual had prevalent active TBD diagnosed at their surveillance appointment, which occurred within two weeks of landing in Canada.

Attendance at the surveillance and assessment appointments was high, at 94.3% and 92.7%, respectively (defined in Table 5). The median time between surveillance and assessment appointments was 28 days (interquartile range [IQR]: 9, 101), and 10% of all referrals were associated with a wait time of >6 months between referral and assessment. From 177 unique individuals referred, only 95 (53.6%) were ultimately determined to be candidates for prevention, 86 (90.5%) of whom were offered treatment. Just over 87% of individuals who were offered accepted treatment and completion was high at 94.6% (Figure 3). Out of 95 individuals referred through this initiative, 71 successfully progressed through the TBI cascade of care while attrition at some step or another affected 24. Individuals who had a successful cascade were slightly younger than those who did not (average 36 years vs. 52.8 years), and less likely to have had their IME in-country (32.4% vs. 58.3%); data not shown.

| Performance metrics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total unique individuals referred | 177 (100.0) |

| Individuals who attended a surveillance appointmentFootnote a | 167 (94.3) |

| Individuals who completed an assessment appointmentFootnote b | 164 (92.7) |

| Individuals who had TBI testing repeated | 113 (63.8) |

| Total unique individuals who attended surveillance | 167 (100.0) |

| Individuals with a surveillance appointment that preceded referral | 60 (35.9) |

| Individuals whose surveillance appointment occurred within 6 months of referral | 89 (53.2) |

| Individuals whose surveillance appointment occurred >6 months from referral | 18 (10.7) |

| Total unique individuals who completed physician assessment | 164 (100.0) |

| Individuals recommended TPT | 86 (52.4) |

| Individuals who initiated TPT | 75 (87.2) |

| Individuals who completed TPT | 71 (94.7) |

Abbreviations: TBI, tuberculosis infection; TPT, tuberculosis preventive therapy Footnotes

|

|

Figure 3: Descriptive text

The figure shows two flowcharts, the top flowchart illustrates how the 179 referrals moved through the stages of care in the Alberta tuberculosis program and the bottom horizontal flowchart shows the tuberculosis infection cascade of care for individuals. The top figure is a flowchart, which starts with 179 referrals and splits into two paths: blue and yellow. The blue path follows the referrals that met inclusion, where of the 140 referrals that met the inclusion criteria, 131 led to full assessments; of those individuals who were fully assessed, 41 were put to no further follow-up. The yellow path follows referrals that were made despite not meeting inclusion criteria (misclassified) where of the 39 misclassified referrals, 35 led to full assessments and of those, 30 individuals were put to no further follow-up. The bottom figure has a blue gradient and flows horizontally showing boxes with numbers that correspond to the following stages in the cascade of care, connected by arrows: eligible for TB preventive therapy, offered treatment, accepted treatment, and completed treatment. There were 95 individuals who were eligible for TB preventive therapy, 86 offered, 75 who accepted and, of those, 71 successfully completed treatment.

Abbreviations: ESRD, end-stage renal disease; IGRA, interferon-gamma release assay; IME, immigration medical exam; TB, tuberculosis; TBI, tuberculosis infection; TST, tuberculin skin test

Footnotes- Footnote a

-

Each referral group includes one individual who had two distinct IMEs during the review period and was hence referred twice

- Footnote b

-

33 negative test results on file; 6 missing test results

- Footnote c

-

Of the 166 full assessment appointments, 61 were for individuals who had contact with provincial TB services that pre-dated the referral, of which 72.1% resulted from an IME performed in Canada and 27.9% were from those whose IME was done overseas

- Footnote d

-

Of surveillance appointments (n=133 in the “met inclusion” group; n=36 in the misclassified group)

- Footnote e

-

Sum of individuals who were fully assessed but not put to no further follow up

- Footnote f

-

Nine individuals were not offered treatment for miscellaneous reasons (did not have insurance, died incidentally, moved or left Canada)

Notably, 60 (35.9%) individuals had contact with TB services prior to notification to the province by IRCC of their referral through this initiative, with the median number of days between those events being 148 days (IQR: 67, 364) (see Table 5). For 53 (88.3%) of those individuals, their prior contact occurred more than 30 days before the province receiving their referral, and majority was observed in individuals whose IME was performed in-country (83%). In addition, TBI screening tests were repeated in Alberta for 113 (63.1%) of all individuals referred. Among those, 39 had a negative test result or else no evidence of a prior test having been performed as part of the IME; see Figure 3. From the remaining 140 referrals, after excluding those 39 with negative or no test result in their IME, were two individuals each referred twice. In other words, of the 179 total referrals made, 138 unique individuals were seen from referrals to Alberta TB services that met all inclusion criteria of this enhanced screening initiative over the review period.

Discussion

This enhanced TBI screening initiative has been nationally administered by IRCC since 2019 but, given its restrictive screening inclusion, applies to very few of all newcomers to Canada Footnote 17Footnote 23. Outcomes of individuals referred through it have heretofore not been reported, a knowledge gap that this evaluation contributes to closing. Local data showed that this initiative was highly effective at connecting referred individuals to TB services in the province in a timely fashion, including for one individual who had prevalent disease at their surveillance appointment who was rapidly provided TBD treatment. Despite this success, only about half of those referred for prevention were considered suitable candidates for TPT after in-country assessment. Those who were offered treatment had high rates of acceptance and completion. The conclusion drawn is that the program was limited by certain inefficiencies, but future evaluations should be undertaken in other high immigrant receiving provinces to determine unique and common obstacles to its implementation and effectiveness with respect to TB control in Canada. From the limited vantage point of this study, cautious, but generalizable takeaways are presented.

First, redundant patient referrals were observed. About one-third of individuals referred by this initiative had already been seen by TB prevention and care services in Alberta prior to the referral being made. This may be due to an administrative delay, whereby individuals initiate their surveillance appointment prior to TB services being notified of the referral. It may also result from in-country applicants, who are likelier to have prior health system contact to manage their high-risk medical condition that satisfies the requirement for screening during the IME. Across Canada, it is the standard of care to screen for TBI among patients provided care for HIV/AIDS, end-stage renal disease, solid organ transplant ,and head and neck cancers and this may account for much of the duplication Footnote 9Footnote 24.

Second, a substantial number of individuals referred, who did not meet the screening or test result inclusion criteria, were observed. Such misclassification occurs in the events prior to referrals being made by IRCC, so its rate is likely countrywide. As a result, a high volume of individuals who are not suitable candidates for TPT are referred nationally contributing to increased workload, unnecessary testing, and reduced yield of the intervention.

Third, information management pitfalls and resource waste were observed. For example, in Alberta, nearly two–thirds of individuals referred underwent local repeat screening. On the one hand, this may be due to test results being hard to find. On the other hand, it may be due to misalignment between panel physician member guidance and the local standard of care. For instance, the instructions guide physicians to report test results qualitatively, which conflicts with the standard of care in Alberta to base a TBI diagnosis on quantitative test results Footnote 17.

Although it is recognized that this initiative is a step in the right direction to close prevention gaps for migrants to Canada, more expansive screening for PBOC especially designed to reach migrants not identified by current methods should be considered. For example, the latest edition (8th) of the Canadian Tuberculosis Standards recommends TB screening within five years of arrival for PBOC originating from countries with a TB incidence of >200/100,000, who have low to moderate risk of TB reactivation, and are aged ≤65 years; the TBI screening infrastructure now in place for the IME would ideally support implementation of this recommendation. This strategy would elevate weighting of exposure and infection risk in addition to, or instead of, underlying reactivation risks Footnote 7. Relatedly, it was noted that individuals whose IME was performed in-country as opposed to overseas were less likely to be considered eligible for prevention at assessment, and more likely to have an inferior TBI care cascade. As a result, cost savings may be achieved by restricting TBI screening to those undertaking an IME overseas.

Limitations

Although the enhanced TBI screening initiative for migrants is a nationally administered initiative, it was only evaluated in one province and the review period overlapped with the COVID-19 pandemic, which contributed to a sharp decline in global movement and thus reduced expected referral volume. It is noted that while some implementation challenges are related to pre-referral events in administering and reporting of tests in the IME, others may be unique to the organization of TB services by jurisdiction, thereby limiting the generalizability of our reported data. Alberta TB services are highly centralized, with one point of contact for IRCC referrals that get distributed to its three public health TB clinics based on the referred individual’s residence Footnote 25. Other areas with decentralized TB control efforts may see distinct and more diffuse challenges. The retrospective nature of data collection for this study, and a lack of qualitative data, limit this article to a description of that but not why events occurred. Nevertheless, an evaluation of this initiative is important for detailing implementation lessons that can be used to optimize both its administration, nationally, and corollary patient care, provincially/territorially.

Conclusion

In low TB-incidence settings like Canada, reactivation of imported infection is a significant driver of the epidemic. Immigration pathways are good places to implement screening as they reflect a major pipeline through which infection flows into Canada. That said, targeting screening, so as not to overwhelm the resources of local TB programs to deliver a treatment response, is crucial; IRCC has implemented one such targeted effort cross-country Footnote 10Footnote 26Footnote 27. Compared to its peers, TBI screening has been less robust in Canada. This new initiative, however, is a good step toward expanding TBI screening among PBOC, but we note areas where its administration and local prevention responses can be improved. A lot of work remains if Canada is serious about meeting its TB elimination targets.

Authors' statement

-

CH — Conceptualization, methodology, project administration, writing–original draft

AJ — Formal analysis, writing–original draft

MLE — Data curation, writing–review & editing

RL — Supervision, funding acquisition, writing–review & editingThe content and view expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

Competing interests

None declared.

ORCID numbers

Courtney Heffernan — 0000-0003-1241-7201

Abdul Jamro — 0009-0000-1823-0400

Richard Long — 0000-0003-2126-5430

Acknowledgements

Invaluable guidance, analytic support and data procurement were provided by the staff of the provincial tuberculosis program in Alberta, the Migration Health branch of Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada, and the Infection Prevention and Surveillance Division (IPSD), Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control, Infectious Diseases and Vaccination Programs Branch at the Public Health Agency of Canada for which we are grateful.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada.