Rates of carpal tunnel syndrome, epicondylitis, and rotator cuff claims in Ontario workers during 1997

Vol. 25 No. 2, 2004

Dianne Zakaria

Abstract

The primary objective of this research was the calculation of crude and specific rates of first-allowed, lost-time carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), epicondylitis, and rotator cuff syndrome/tear (RCS/RCT) claims in Ontario workers during 1997. A secondary objective was to determine if results related to these diagnoses were consistent with findings for all cumulative trauma disorders affecting the specific part of upper extremity region. Rates were calculated by combining claim counts and population "at-risk" estimates derived from the Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board databases and Canadian Labour Force Survey, respectively. The prevention index was used to prioritize occupations for intervention. Gender-specific rates declined as one moved proximally along the upper extremity. Similarly, female to male claim rate ratios declined from 1.61 for CTS to 0.47 for RCS/RCT. Frequently occurring highest rate and prevention index occupational categories across gender and diagnoses included "textiles, furs & leather goods" and "other machining occupations". Diagnosis-specific findings were consistent with previously reported part of upper extremity findings.

Key words: carpal tunnel syndrome; claim rates; epicondylitis; gender differences; prevention index; rotator cuff; workers' compensation

Introduction

Work-related cumulative trauma disorder of the upper extremity (CTDUE) claims are more costly and work disabling than traumatic upper extremity1,2 or workers' compensation claims in general.3-5 Additionally, diagnoses which tend to be associated with a gradual onset and have established typical symptoms and objective physical examination findings, such as carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), epicondylitis, rotator cuff syndrome (RCS), and rotator cuff tear (RCT),6,7 may be more costly and work disabling than less clinically defined gradual onset disorders, such as myalgia.1,4,8 In particular, CTS appears most disabling. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics' release on lost-worktime injuries and illnesses in private industry during 2001, CTS had the greatest median days away from work, 25 days; followed by fractures, 21 days; and amputations, 18 days (released Thursday March 27, 2003).

Workers' compensation databases provide a means of surveillance for work-related CTDUE or specific diagnoses. Although many limitations in the use of workers' compensation data exist,9 these databases provide easy access to population level data which can be used to assess costs, target research and prevention efforts, and evaluate prevention or control activities.10-15 For example, previous research examined the rate of definite and definite + possible cumulative trauma disorder claims of the "neck & shoulder/ shoulder & upper arm", "elbow & forearm", and "wrist & hand" in Ontario Workplace Safety & Insurance Board covered workers during the 1997 calendar year.16 This required an extraction algorithm which used "part of body", "event or exposure", and "nature of injury" codes to classify a claim into one of three mutually exclusive categories: definite, possible, or non-CTDUE.17 It may be that targeting clinically well defined diagnoses, which tend to be associated with a gradual onset, would provide similar information using a simpler, "nature of injury" extraction method. However, if results using the two extraction methods differ, research related to parts of the upper extremity cannot be generalized to the more costly and disabling specific diagnoses within these parts and vice versa.

Hence, the primary objective of this research was the estimation of crude and specific rates of CTS, epicondylitis, and RCS/RCT claims in Ontario Workplace Safety & Insurance Board-covered workers during the 1997 calendar year. A secondary objective was to determine if a simple extraction algorithm, which used clinically well defined diagnoses as a surrogate for part of upper extremity-specific cumulative trauma disorders, produced results consistent with a previously used, more complex cumulative trauma disorder extraction algorithm.

Material and methods

Information on gender, age, "part of body", "event or exposure", "nature of injury", and occupation for all first-allowed, lost-time claims occurring in Ontarians, aged 15 years or greater with a date of injury or disease in the 1997 calendar year (105,556), was obtained from the Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board. A first-allowed claim is a newly registered claim for a previously unreported injury or illness deemed compensational. Lost-time refers to the loss of wages.18

Claims with the following Z795-96 Coding of Work Injury or Disease Information Standard "nature of injury" codes were extracted: "12410 carpal tunnel syndrome"; "17393 epicondylitis"; "17391 rotator cuff syndrome"; and "02101 rotator cuff tear". RCS and RCT claims were combined for two reasons. First, only a small number of RCS claims (n=24) were present. Second, the distinction between a gradual versus sudden onset may not always be clear for RCT claims. "Event or exposure" distributions, which describe the manner in which the injury or disease was produced or inflicted by the identified source,10 were presented by "nature of injury". Demographic information was compared across the three "nature of injury" groups using ANOVA and chi-square tests. In the presence of a statistically significant ( =0.05) ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparison test was utilized to identify which groups significantly differed.

Since the Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board and 1997 Canadian Labour Force Survey collected information on gender, age, and occupation, crude and specific rates were calculated by combining claim counts and population "at-risk" estimates derived from the two data sources, respectively. Population "at-risk" estimates were derived as per Zakaria et al.19 Briefly, this involved extracting that class of worker most likely to be insured by the Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board and using actual hours worked to calculate full-time equivalents (FTEs) "at-risk". Occupational categories were defined as per the 1997 Canadian Labour Force Survey, which used Statistics Canada's Standard Occupational Classification, 1980.20 Since directly age-standardized gender, "nature of injury", and occupation-specific rates produced conclusions generally consistent with the non-standardized rates, they will not be presented.

| % Distribution | ||

|---|---|---|

| Carpal tunnel syndrome (n = 1167) | ||

| repetitive motion, not elsewhere classified | 34.45 | |

| repetitive placing, moving objects, except tools | 24.94 | |

| repetitive use of tools | 18.59 | |

| typing or key entry | 11.40 | |

| repetitive motion unspecified | 2.57 | |

| other | 8.05 | |

| Epicondylitis (n = 638) | ||

| repetitive placing, moving objects, except tools | 35.42 | |

| repetitive motion, not elsewhere classified | 32.13 | |

| repetitive use of tools | 14.89 | |

| typing or key entry | 4.55 | |

| repetitive motion unspecified | 3.29 | |

| overexertion, not elsewhere classified | 3.29 | |

| other | 6.43 | |

| Rotator cuff syndrome/tear (n = 208) | ||

| overexertion, not elsewhere classified | 25.96 | |

| overexertion in lifting | 19.23 | |

| fall to floor, walkway, or other surface | 7.69 | |

| overexertion in pulling or pushing | 7.21 | |

| repetitive motion, not elsewhere classified | 6.25 | |

| bodily reactions & exertions, nec | 5.29 | |

| repetitive placing, moving objects, except tools | 4.81 | |

| struck by falling object | 2.88 | |

| bodily reaction, nec | 2.88 | |

| overexertion in holding, carrying | 2.40 | |

| bending, climbing, crawling, reaching | 2.40 | |

| other overexertion | 0.96 | |

| other repetition | 2.88 | |

| other traumatic | 9.13 | |

Note: NEC = not elsewhere classified |

||

| Characteristic | CTS n = 1167 |

Epicondylitis n = 638 |

RCS/RCT n = 208 |

|---|---|---|---|

| % Male | 46.10 | 54.86 | 74.52 |

| Age, mean years (sd) | 40.66 (9.37) | 40.62 (8.53) |

43.95 (11.69) |

| median years | 40.00 | 40.00 | 44.00 |

| Age (%) | |||

| 15-24 years | 4.63 | 3.76 | 3.37 |

| 25-34 | 21.08 | 20.53 | 20.67 |

| 35-44 | 40.36 | 42.63 | 27.40 |

| 45-54 | 25.96 | 27.74 | 28.37 |

| 55 plus | 7.88 | 5.17 | 20.19 |

| unknown | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.00 |

Note: Only first-allowed, lost-time claims have been considered. CTS = Carpal Tunnel Syndrome; RCS = Rotator Cuff Syndrome; RCT = Rotator Cuff Tear. |

|||

Rate standard errors were calculated according to Armitage and Berry 21 and used for approximate standard normal 95% confidence intervals (CI). Interactions between gender, age, and "nature of injury" were examined using Poisson regression.22

Finally, since focussing intervention efforts on the highest risk occupation will have little impact on claim numbers if the "at-risk" population is small, a prevention index was used to prioritize occupations for intervention purposes.4 For each "nature of injury", occupational categories were ranked according to the frequency of claims and the rate of claims. The prevention index is the mean of these two ranks. For example, an occupational category that ranks first with respect to frequency of claims and rate of claims will have a prevention index equal to one making it worthy of increased attention and resources from a population, public health perspective. However, the prevention index does not provide information on the feasibility or potential success of interventions.

| Syndrome | Overall | Females | Males | Female: male RR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTS | a29.07 (27.31, 30.83) |

37.22 (34.22, 40.21) |

23.15 (21.14, 25.16) | 1.61 |

| Epicondylitis | 15.89 (14.62, 17.17) |

17.04 (15.04, 19.04) | 15.06 (13.45, 16.67) | 1.13 |

| RCS/RCT | 5.18 (4.47, 5.89) |

3.14 (2.29, 3.98) | 6.67 (5.61, 7.73) | 0.47 |

Note: Only first-allowed, lost-time claims have been considered. CTS = Carpal Tunnel Syndrome; RCS = Rotator Cuff Syndrome; RCT = Rotator Cuff Tear; RR = Relative Rate. aRate per 100,000 full-time equivalents (1 full-time equivalent = 50 wks/year * 40 hours/week = 2,000 hours) with 95 percent confidence interval (CI). |

||||

Results

Table 1 presents "event or exposure" codes by "nature of injury". More than 90% of CTS and epicondylitis claims were associated with repetition. Eighty percent of RCS/RCT claims were associated with non-traumatic events or exposures primarily involving overexertion and repetition. Of the 24 claims coded RCS, 21 (88%) were associated with repetition and none were traumatic.

Table 2 presents sex and age characteristics by "nature of injury". When comparing CTS, epicondylitis and RCS/RCT, the proportion of male claims increased with more proximal upper extremity diagnoses (x2=60.5726, df=2, p<0.0001). Mean age significantly varied across "nature of injury" (F=11.53, df=2, 2008, p<0.0001). Tukey's multiple comparison test (a=0.05) indicated that the mean age of RCS/RCT claimants was significantly greater than that of CTS or epicondylitis claimants.

Gender-specific claim rates (Table 3) declined as one moved proximally along the upper extremity. Similarly, the female to male rate ratio declined from 1.61 for CTS to 0.47 for RCS/RCT.

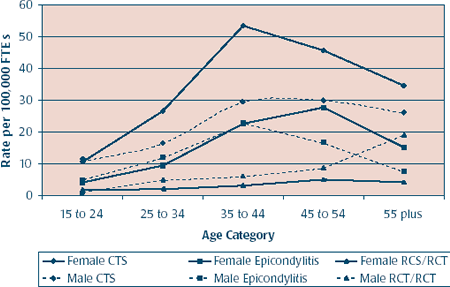

When examining age-specific rates (Figures 1 and 2), CTS and epicondylitis demonstrated a parabolic relationship between age and rate for men and women with the peak generally occurring in the 35 to 44 or 45 to 54 year age categories. For RCS/RCT, the rate generally rose with age, particularly in males aged 55+. Poisson regression using detailed gender, "nature of injury" and age-specific claim counts and "at-risk" estimates revealed significant gender*nature of injury, gender*age, and age*nature of injury interactions ( a=0.05).

FIGURE 1

Age-specific rates of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), epicondylitis, and rotator cuff syndrome/tear (RCS/RCT) claims in Ontario employees, 1997. Rates are expressed per 100,000 full-time equivalents (FTEs). One full-time equivalent is 2,000 worked hours (50 wks/year * 40 hrs/wk).

Table 4 presents those occupations with the highest rates and prevention indexes by gender and "nature of injury".

Frequently occurring highest rate occupations across gender and "nature of injury" included "textiles, furs & leather", "other machining occupations", and "other transportation operators". Frequently occurring highest prevention index occupations across gender and "nature of injury" included "textiles, furs & leather goods", "other machining occupations", and "food, beverage & related processing". In men, "metal products, not elsewhere classified" was consistently identified as having a high prevention index across "nature of injury". Table 5 lists occupations included in these occupational categories. There was greater consistency in the highest rate occupations across gender for a particular "nature of injury" than there was across "nature of injury" for a particular gender. Notwithstanding, the effect of gender was not consistent across "nature of injury" or occupational categories within a particular "nature of injury".

FIGURE 2

Gender and age-specific rates of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), epicondylitis, and rotator cuff syndrome/tear (RCS/RCT) claims in Ontario employees, 1997. Rates are expressed per 100,000 full-time equivalents (FTEs). One full-time equivalent is 2,000 worked hours (50 wks/year * 40 hrs/wk).

Discussion

Other workers' compensation studies have noted a reduction in the proportion of female claims as one moves proximally along the upper extremity;4 a higher rate of CTS in women relative to men; 11,23,24 a reduction in the female to male rate-ratio as one moves proximally along the upper extremity;24 and a parabolic relationship between age and the rate of CTS.23,24 Potential reasons for gender differences include gender differences in occupational distributions;16 gender segregation of tasks within the same job title;25,26 and many biological and social factors not examined by this research.9 In fact, female CTS rates have been found to be comparable to male rates in occupations which supply similar exposures to both genders.27 Potential reasons for the parabolic relationship between CTS and epicondylitis claim rates and age include the healthy worker survivor effect;28-30 workers progressing to physically less stressful jobs as they gain seniority; or policies of the Ontario Workplace Safety & Insurance Board. Specifically, once a claim has been established any recurrences or associated disorders are documented on the initial claim and thus would not be acknowledged in analyses of first-allowed, lost-time claims.18

A direct comparison of work-related rates of CTS, epicondylitis, and RCS/RCT claims with previously reported workers' compensation claim rates is difficult because the present research deals with lost-time claims whereas previous work has examined all claims.1,4,11,23,24,31 However, the Bureau of Labor Statistics' estimate for the incidence rate of occupational CTS involving days away from work was 3.0 per 10,000 FTEs in private industry for 2001 ( released Thursday March 27, 2003). This is comparable to the 2.9 per 10,000 FTEs obtained in the present study.

Although the method of categorizing occupations or industries varies across studies, some consistencies were noted regarding high-risk occupations. For example, previous research has identified the following as high risk for CTS: grinding, abrading, buffing and polishing operators; butchers and meat cutters; textile sewing machine operators;23 shellfish packing; meat/ poultry dealers; packing house; fish canneries processing;11 poultry processing; and meat packing.31 These appear consistent with the presently identified occupational categories at high risk of CTS: "textiles, furs & leather goods"; "food, beverage & related processing"; and "other machining occupations" (Tables 4 and 5).

CTS and epicondylitis findings were very similar to previously noted definite "wrist & hand" and "elbow & forearm" cumulative trauma disorder findings, respectively.16 This might be expected as 59% of definite "wrist & hand" cumulative trauma claims had CTS as their "nature of injury", and 69% of definite "elbow & forearm" cumulative trauma claims had epicondylitis as their "nature of injury" (unpublished observations). However, the RCS/RCT claim findings were consistent with the definite+possible "neck & shoulder/ shoulder & upper arm" cumulative trauma disorder findings despite the fact that only 3.4 percent of the latter claims had RCS or RCT as their "nature of injury". Additional reasons for consistency across extraction algorithms include "nature of injury" misclassification, or a common etiology for disorders segregated to an anatomical region.

Comparisons of work-related, diagnosis-specific claim rates with general population rates are difficult because of the lost-time nature of the claims and the sparse general population data. Compared to present CTS findings, general population incidence rates are much greater;32,33 peak in older age categories;32-34 and have an older mean age at diagnosis.33,34 However, an increased risk in women relative to men has been noted in the general population.32-34 Similarly, RCS/RCT claim findings are inconsistent with general population studies indicating that neck and shoulder disorders are more common among women than men, but are consistent with the increased incidence of neck and shoulder problems with age.35 These comparisons suggest that work-related diagnosis-specific disorders may have aetiologies that differ from those in the general population.

Limitations

The limitations of this research have been previously detailed16 and thus will be briefly reviewed. First, the specificity of the occupational categories was limited by the level of detail used in the Labour Force Survey. Consequently, some occupations at high risk of CTS, epicondylitis, or RCS/RCT claims may be masked by the aggregation, but an elevated risk in light of the aggregation is certainly worthy of increased attention. Second, exposure was quantified using broad occupational categories. Hence, this research does not identify the risk factors for CTS, epicondylitis, or RCS/RCT but rather the high-risk occupational categories.

Third, first-allowed, lost-time claims rather than all first-allowed claims were used because only the former were coded in detail. Thus, the rates reflect those injuries significant enough to result in a loss of wages. Therefore, it is possible that occupational categories identified as low risk may have a substantial occurrence of claims that do not result in lost wages. Fourth, as the rates became more and more specific, stability was compromised by a decreasing number of events and smaller population "at-risk" estimates.36 One solution could be the combining of data from consecutive calendar years. Finally, previous research has demonstrated substantial under-reporting of cumulative trauma disorders of the upper extremity.37-39 If reported CTS, epicondylitis, and RCS/RCT injuries are not representative of all such injuries, bias may result.

Conclusions

CTS, epicondylitis, and RCS/ RCT claims had differing gender, age and event or exposure distributions. RCS/RCT claimants were primarily male, of older age, and had events or exposures related to overexertion. Gender-specific claim rates and female-to-male rate ratios declined as one moved proximally along the upper extremity. Frequently occurring highest rate and prevention index occupational categories across gender and "nature of injury" included "textiles, furs & leather goods" and "other machining occupations" making both worthy of further investigation. A simple extraction algorithm, which used clinically well defined diagnoses as a surrogate for part of upper extremity-specific cumulative trauma disorders, produced results which were consistent with a previously used, more complex cumulative trauma disorder extraction algorithm.

References

- Silverstein B, Welp E, Nelson N, Kalat J. Claims incidence of work-related disorders of the upper extremities: Washington State, 1987 through 1995. Am J Public Health 1998;88:1827-33.

- Yassi A, Sprout J, Tate R. Upper limb repetitive strain injuries in Manitoba. Am J Ind Med 1996;30:461-72.

- Hashemi L, Webster B, Clancy E, Courtney T.Length of disability and cost of work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the upper extremity. J Occup Environ Med 1998;40(3):261-9.

- Silverstein B, Viikari-Juntura E, Kalat J. Use of a prevention index to identify industries at high risk for work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the neck, back, and upper extremity in Washington State, 1990-1998. Am J Ind Med 2002; 41:149-69.

- Webster B, Snook S. The cost of compensable upper extremity cumulative trauma disorders. J Occup Med 1994;36(7):713-7.

- Harrington J, Carter J, Birrel L, Gompertz D. Surveillance case definitions for work related upper limb pain syndromes. Occup Environ Med 1998;55:264-71.

- Marx R, Bombardier C, Wright J. What do we know about the reliability and validity of physical examination tests used to examine the upper extremity. J Hand Surg (Am)1999;24:185-93.

- Beaton D. Examining the clinical course of work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the upper extremity using the Ontario workers' compensation board administrative database. Toronto: University of Toronto, 1995.

- Zakaria D, Robertson J, MacDermid J, Hartford K, Koval J. Work-related cumulative trauma disorders of the upper extremity: Navigating the epidemiologic literature. Am J Ind Med 2002; 42(3):258-69.

- Canadian Standards Association. Z795-96 Coding of Work Injury or Disease Information. Etobicoke, Ontario: Canadian Standards Association, 1996.

- Franklin G, Haug J, Heyer N, Checkoway H, Peck N. Occupational carpal tunnel syndrome in Washington state, 1984-1988. Am J Public Health 1991;81:741-6.

- Muldoon J, Wintermeyer L, Eure J et al. State activities for surveillance of occupational disease and injury, 1985. MMWR 1987;36:7-12.

- Saleh S, Fuortes L, Vaughn T, Bauer E. Epidemiology of occupational injuries and illnesses in a university population: A focus on age and gender differences. Am J Ind Med 2001;39:581-6.

- Schwartz E. Use of workers' compensation claims for surveillance of work-related illness. New Hampshire, January 1986-March 1987. MMWR 1987;36:713-20.

- Tanaka S, Seligman P, Halperin W et al. Use of workers' compensation claims data for surveillance of cumulative trauma disorders. J Occup Environ Med 1988;30(6):488-92.

- Zakaria D, Robertson J, Koval J, MacDermid J, Hartford K. Rates of cumulative trauma disorder of the upper extremity claims in Ontario workers during 1997. Chron Dis Can 2003;25(1):22-31.

- Zakaria D, Mustard C, Robertson J et al. Identifying cumulative trauma disorders of the upper extremity in workers' compensation databases. Am J Ind Med 2003; 43:507-18.

- Workplace Safety and Insurance Board of Ontario. Operational Policy. Toronto, Ontario: Workplace Safety and Insurance Board of Ontario, 1998.

- Zakaria D, Robertson J, MacDermid J, Hartford K, Koval J. Estimating the population at risk for Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board-covered injuries or diseases. Chron Dis Can 2002;23(1):17-21.

- Statistics Canada. Standard occupational classification 1980. Ottawa, Ontario: Standards Division, 1981.

- Armitage P, Berry G. Statistical methods in medical research. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1994;91.

- Frome E, Checkoway H. Use of Poisson regression models in estimating incidence rates and ratios. Am J Epidemiol 1985; 121(2):309-23.

- Davis L, Wellman H, Punnett L. Surveillance of work-related carpal tunnel syndrome in Massachusetts, 1992-1997: A report from the Massachusetts Sentinel Event Notification System for Occupational Risks (SENSOR). Am J Ind Med 2001; 39:58-71.

- Feuerstein M, Miller V, Burrell L, Berger R. Occupational upper extremity disorders in the federal workforce. J Occup Environ Med 1998;40(6):546-55.

- Messing K, Dumais L, Courville J, Seifert A, Boucher M. Evaluation of exposure data from men and women with the same job title. J Occup Environ Med 1994; 36(8):913-7.

- Nordander C, Ohlsson K, Balogh I, Rylander L, Palsson B, Skerfving S. Fish processing work: the impact of two sex dependent exposure profiles on musculoskeletal health. Occup Environ Med 1999;56:256-64.

- McDiarmid M, Oliver M, Ruser J, Gucer P. Male and female rate differences in carpal tunnel syndrome injuries: personal attributes or job tasks? Environ Res 2000; 83(1):23-32.

- Hernberg S. Validity aspects of epidemio-logical studies. In: Karvonen M, Mikheev M, eds. Epidemiology of occupational health. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 1986.

- Monson R. Observations on the healthy worker effect. J Occup Environ Med 1986; 28:425-33.

- Steenland K, Deddens J, Salvan A, Stayner L. Negative bias in exposure-response trends in occupational studies: Modeling the healthy worker survivor effect. Am J Epidemiol 1996;143:202-10.

- Hanrahan L, Higgins D, Anderson H, Haskins L, Tai S. Project SENSOR: Wisconsin surveillance of occupational carpal tunnel syndrome. Wis Med J 1991;990:80-3.

- Nordstrom D, Destefano F, Vierkant R, Layde P. Incidence of diagnosed carpal tunnel syndrome in a general population. Epidemiology 1998;9(3):342-5.

- Stevens J, Sun S, Beard C, O'Fallon W, Kurkland L. Carpal tunnel syndrome in Rochester, Minnesota, 1961 to 1980. Neurology 1988;38:134-8.

- Mondelli M, Giannini F, Giacchi M. Carpal tunnel syndrome incidence in a general population. Neurology 2002;58:289-94.

- Magnusson M, Pope M. Epidemiology of the neck and upper extremity. In: Nordin M, Andersson G, Pope M, eds. Musculoskeletal disorders in the workplace: principles and practice. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book, Inc., 1997;328-35.

- Pagano M, Gauvreau K. Principles of biostatistics. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1993.

- Cummings K, Maizlish N, Rudolph L, Dervin K, Ervin A. Occupational disease surveillance: Carpal tunnel syndrome. MMWR 1989;38:485-9.

- Fine L, Silverstein B, Armstrong T, Anderson C, Sugano D. Detection of cumulative trauma disorders of the upper extremities in the workplace. J Occup Environ Med 1986; 28(8):674-83.

- Maizlish N, Rudolph L, Dervin K, Sankaranarayan M. Surveillance and prevention of work-related carpal tunnel syndrome: An application of the sentinel events notification system for occupational risks. Am J Ind Med 1995;27:715-29.

New Associate Scientific Editor

We are very pleased to welcome Dr. Claire Infante-Rivard to the position of Associate Scientific Editor of Chronic Diseases in Canada.

Dr. Infante-Rivard graduated from the University of Montréal with a medical degree, then completed a master's degree in health administration at the University of California at Berkeley, and a doctorate in epidemiology and statistics at McGill University.

As head of McGill University's Environment and Children's Health Research Group, this doctor and epidemiologist has dedicated her career to prevention and public health and to measuring gene-environment interactions in the development of childhood leukemia.

Calendar of Events

September 1-4, 2004 |

6th International Diabetes Conference onIndigenous People - Dreaming TogetherExperience |

Diabetes Queensland Conferences Secretariat Indigenous Conference Services Australia |

September 4-8, 2004 |

European Respiratory Congress 14th AnnualCongress 2004 |

Congrex Sweden AB |

September 10-12, 2008 |

The Fifth World Conference on The Promotion of Mental Health and Prevention of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: From Margins to Mainstream |

Suite 6, 19-23 Hoddle Street Richmond, VIC 3121, Australia |

October 1- 5, 2004 |

26th Annual Meeting of the American Societyfor Bone and Mineral Research |

2025 M Street, NW, Suite 800 |

October 12-15, 2004 |

2nd International Conference on Local andRegional Health Programmes |

Association pour la santé publique du Québec |

October 23-27, 2004 |

2004 Canadian Cardiovascular Congress |

CCC Secretariat |

November 25-27, 2004 |

Family Medicine Forum 2004 |

The College of Family Physicians of Canada |

Author References

Dianne Zakaria, Canadian Institute For Health Information, 200-377 Dalhousie Street, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1N 9N8 Correspondence: Dianne Zakaria, Canadian Institute For Health Information, 200-377 Dalhousie Street, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1N 9N8; Fax: (613) 241-8120; E-mail: dzakaria@cihi.ca