Original quantitative research – Screening, prevention and management of osteoporosis among Canadian adults

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada

Siobhan O’Donnell, MSc; in collaboration with the Osteoporosis Surveillance Expert Working Group

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.38.12.02

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references:

Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Correspondence: Siobhan O’Donnell, Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research, Public Health Agency of Canada, 785 Carling Avenue, AL 6806B, Ottawa, ON K1A 0K9; Tel: 613-301-7325; Email: siobhan.odonnell@canada.ca

Abstract

Introduction: This study provides a benchmark for the nationwide use of osteoporosis screening, prevention and management strategies among Canadians aged 40 years and older (40+) using data collected one year prior to the release of Osteoporosis Canada’s latest (2010) clinical practice guidelines.

Methods: Data are from the 2009 Canadian Community Health Survey—Osteoporosis Rapid Response Component. The study sample (n = 5704) was divided into four risk subgroups: (1) osteoporosis diagnosis and major fracture; (2) osteoporosis diagnosis only; (3) major fracture only; or (4) neither osteoporosis diagnosis nor major fracture. We calculated descriptive statistics and performed multinomial multivariate logistic regression analyses to examine factors independently associated with osteoporosis screening, prevention and management strategies. Estimates were weighted to represent the Canadian household population (40+) living in the 10 provinces.

Results: Approximately 10.1% of the population or 1.5 million Canadians 40+ reported having been diagnosed with osteoporosis. The majority related taking vitamin D or calcium supplements and having been prescribed osteoporosis medication(s), while less than 40% reported regular physical activity. Among those without a reported osteoporosis diagnosis, an estimated 6.7% or 1 million reported having had a major fracture, of which one-third reported having had a bone density test and less than half reported taking vitamin D supplements, calcium supplements or engaging in regular physical activity. Major fracture history was not associated with bone density testing or osteoporosis medication use.

Conclusions: A large proportion of Canadians at risk for osteoporosis—those with a major fracture history—are not undergoing bone density testing nor are they engaging in lifestyle approaches known to help maintain healthy bones. This study provides the historical information required to evaluate whether the latest clinical practice guidelines have had an impact on osteoporosis care in Canada.

Keywords: osteoporosis, screening, prevention, disease management, health surveys, population surveillance

Highlights

Q: Who is more likely to receive bone mineral density tests?

A: Older women (aged 65 years and older) with other physical chronic conditions.

Q: Who is more likely to use nutritional supplements known to facilitate healthy bone development?

A: Older women with osteoporosis, with postsecondary education (calcium only) and higher income (vitamin D only) who are not obese, have had a major fracture after age 40 (vitamin D only) and have other physical chronic conditions.

Q: Who is more likely to engage in regular physical activity?

A: Men and women of all ages without osteoporosis, with postsecondary education and higher income, who are not obese, and who are without other physical chronic conditions.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a common skeletal disorder characterized by low bone density and an elevated risk of fracture. It is more prevalent among older individuals and among women. Its prevalence is projected to rise markedly over the next few decades, as the number of older individuals is expected to increase.Footnote 1 The fractures associated with osteoporosis, especially fractures of the spine and hip, are a significant cause of disability, mortality and health care use. Despite available evidence-based interventions that can substantially reduce the risk of these fractures,Footnote 2 extensive data suggest that most individuals with fracture do not undergo appropriate assessment or treatment.Footnote 3Footnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 7

Clinical practice guidelines outline several clinical factors that help to identify people who have a high risk of fracture. These factors include advanced age, previous fragility fracture, parental hip fracture, cigarette smoking, heavy alcohol consumption, low body weight, prolonged use of glucocorticoids and other bone-depleting medications, certain disease states and genetic disorders associated with bone loss. Furthermore, they provide recommendations regarding lifestyle approaches such as calcium and vitamin D intake and physical activity, in addition to the appropriate and selective use of medications for the prevention and management of osteoporosis.Footnote 2

The Public Health Agency of Canada developed and funded the 2009 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS)—Osteoporosis Rapid Response (ORR) Component to provide information on the prevalence, screening, prevention and management of osteoporosis in a nationally representative sample of Canadians 40 years of age or older living in the community. Using data from this questionnaire, the objectives of our study were: 1) to provide prevalence estimates of diagnosed osteoporosis and/or major fracture history (i.e. self-reported fracture after age 40 of the wrist, upper arm, spine or hip); 2) to describe the sociodemographics, behavioural risk and protective factors, health characteristics, and use of osteoporosis screening, prevention and management strategies according to four risk subgroups based on osteoporosis diagnosis and major fracture history; and 3) to determine the factors associated with the use of these osteoporosis management strategies.

The findings from this study represent the most recent data of their kind and serve as a benchmark for the nationwide use of osteoporosis screening, prevention and management strategies. Furthermore, the findings are based on data from an ideal moment in time—that is, one year prior to release of the latest (2010) clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada—and therefore provide the necessary historical information to evaluate whether these guidelines have had a positive impact on osteoporosis care in Canada.

Methods

Data source and study sample

The 2009 CCHS is a cross-sectional, population-based health survey designed to provide reliable estimates at the health region level.Footnote 8 The target population included Canadians 12 years of age and older living in private dwellings in the 10 provinces and three territories. Persons living on Indian reserves or Crown lands, those residing in institutions, full-time members of the Canadian Forces and residents of certain remote regions were excluded (approximately 2% of the target population). The 2009 CCHS used three sampling frames in order to select the sample of households: 49% of the sampled households from an area frame, 50% from a list frame of telephone numbers and the remaining 1% from a random digit dialling telephone number frame. The selection of a household member was made at the time of contact for data collection. All members of the household were listed, and a person aged 12 years or over was selected using various selection probabilities based on age and household composition. The survey was administered by trained personnel via either computer-assisted telephone interview or computer-assisted personnel interview (English or French).

The questions within the ORR Component appeared in the 2009 CCHS for a single collection period (i.e. during the months of March and April) and took approximately two minutes of interview time. The target population included all Canadians 40 years of age and older living in private dwellings in the 10 provinces. It was designed to produce reliable estimates at the national level, by sex and by the following age groups: 40 to 64 and 65 to 79 years. A total of 7461 survey respondents aged 40 years and older participated. Of these respondents, 5849 consented to share their data with the Public Health Agency of Canada, Health Canada and provincial and territorial ministries of health, with an overall response rate of 78.4%. After excluding 145 respondents with missing responses to the diagnosed osteoporosis or major fracture questions, the final study sample contained 5704 individuals. More detailed information regarding the 2009 CCHS is available online: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=67251

Ethics

This study did not require a research ethics board review as it relied exclusively on secondary use of anonymous information as per Article 2.4 of the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans.Footnote * Furthermore, participation in the 2009 CCHS-ORR was completely voluntary. Respondents were informed of the voluntary nature of the survey through a notice prior to the start of the data collection. Interviewers were also instructed to permit respondents to refuse to answer any question or to terminate an interview at any time. Share partners, including the Public Health Agency of Canada, have access to the data under the terms of the data sharing agreements.Footnote 8 These data files contain only information on respondents who agreed (as part of the survey) to share their information with Statistics Canada’s partners. Personal identifiers are removed from the share files to respect respondent confidentiality. Users of these files must first certify that they will not disclose, at any time, any information that might identify a survey respondent.

Measures

Four risk subgroups based on osteoporosis diagnosis status and major fracture history

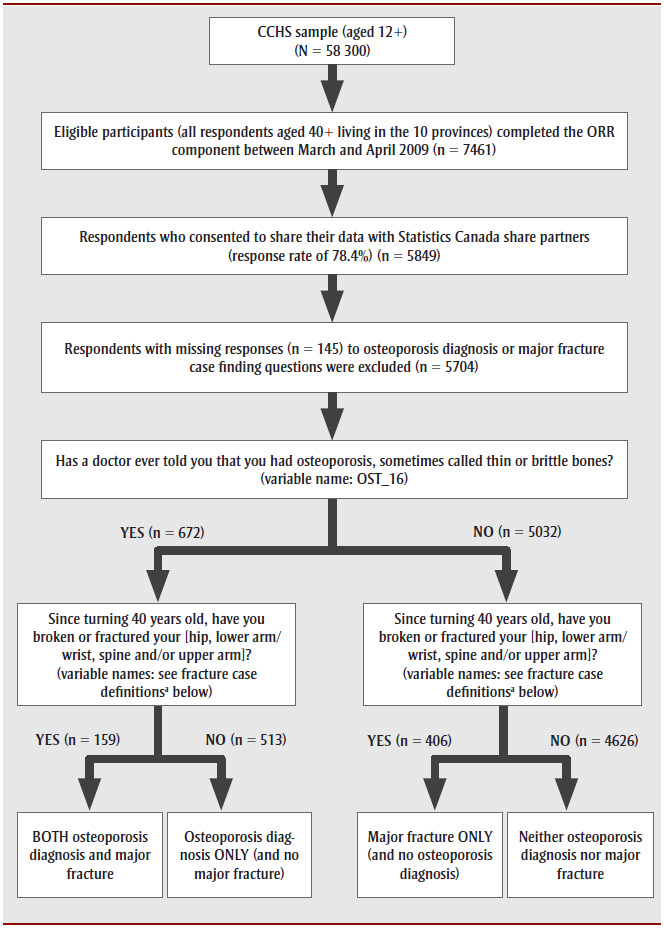

Respondents were classified into one of four mutually exclusive osteoporosis risk subgroups based on their responses to questions regarding their osteoporosis diagnosis status (“Has a doctor ever told you that you had osteoporosis, sometimes called thin or brittle bones?”; response options: “yes”, “no”); and their major fracture history (“Since turning 40 years old, have you broken or fractured your [lower arm/wrist, upper arm, spine, or hip]?”Footnote †; response options: “yes”, “no”). Based on responses to these questions, respondents were categorized as having (1) both osteoporosis diagnosis and major fracture; (2) osteoporosis diagnosis only (and no major fracture); (3) major fracture only (and no osteoporosis diagnosis); or (4) no osteoporosis diagnosis and no major fracture. Figure 1 illustrates how respondents were categorized among the aforementioned risk subgroups.

Abbreviations: CCHS-ORR, Canadian Community Health Survey—Osteoporosis Rapid Response; n, unweighted number.

Note: The 2009 CCHS questionnaire is available online: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=67251

a Fracture case definitions:

Lower arm/wrist fracture: if OST_Q05=’yes’ or (INJ_Q05=’broken or fractured bones’ and INJ_Q06=’elbow or lower arm’ and OST_Q04=’lower arm’) or (INJ_Q05=’broken or fractured bones’ and INJ_Q06=’wrist’)

Upper arm fracture: if OST_Q12=’yes’ or (INJ_Q05=’broken or fractured bones’ and INJ_Q06=’shoulder/upper arm’ and OST_Q11=’upper arm’)

Spine fracture: if OST_Q08=’yes’ or (INJ_Q05=’broken or fractured bones’ and INJ_Q06=’upper back and spine (excluding neck) or lower back or spine’)

Hip fracture: If OST_Q01=’yes’ or (INJ_Q05=’broken or fractured bones’ and INJ_Q06=’hip’)

Figure 1 - Text description

Figure 1 is a flowchart illustrating how respondents were categorized among the risk subgroups.

From the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) sample (participants aged 12+; N = 58 300), eligible participants (all respondents aged 40+ living in the 10 provinces) completed the Osteoporosis Rapid Response component between March and April 2009 (n = 7461). Respondents who did not consent to share their data were removed, leaving those who consented to share their data with Statistics Canada share partners (response rate of 78.4%; n = 5849). Respondents with missing responses (n = 145) to osteoporosis diagnosis or major fracture case finding questions were excluded, leaving n = 5704. This group was separated into 2 subgroups: those who answered “Yes” (n = 672) and those who answered “No” (n = 5032) to the question “Has a doctor ever told you that you had osteoporosis, sometimes called thin or brittle bones? (variable name: OST_16).”

Those who answered “Yes” (n = 672) were then split in 2 smaller subgroups based on their answer to the question “Since turning 40 years old, have you broken or fractured your [hip, lower arm/wrist, spine and/or upper arm]? (variable names: see fracture case definitions below)”: those who answered “Yes” were categorized as having BOTH osteoporosis diagnosis and major fracture (n = 159), and those who answered “No” were categorized as having an osteoporosis diagnosis ONLY (and no major fracture) (n = 513).

Those who answered “No” (n = 5032) were then split in 2 smaller subgroups based on their answer to the question “Since turning 40 years old, have you broken or fractured your [hip, lower arm/wrist, spine and/or upper arm]? (variable names: see fracture case definitions below)”: those who answered “Yes” were categorized as having a major fracture ONLY (and no osteoporosis diagnosis) (n = 406), and those who answered “No” were categorized as having neither osteoporosis diagnosis nor major fracture (n = 4626).

Sociodemographic characteristics

The sociodemographic characteristics included were age (mean age and age groups 40–64 and 65+ years); sex (female, male); cultural/racial background (White, non-White); respondent’s highest level of education (less than postsecondary education and postsecondary graduation); and adjusted household income adequacy quintiles based on deciles, derived by Statistics Canada,Footnote ‡ transformed into quintiles (first/second quintile [low], third quintile [middle] and fourth/fifth quintile [high]).

Risk and protective factors

The risk and protective factors included body mass index (BMI), smoking status and alcohol consumption.

BMI

We used BMI to quantify the prevalence of underweight, normal weight, overweight and obesity. Based on self-reported height and weight, BMI was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms (kg) by height in metres squared (m2).

We applied correction factorsFootnote 9 to adjust for known biases in self-reported BMI (i.e. people overreport their height and underreport their weight).Footnote 10 These correction factors were as follows:

Corrected BMI for males = −1.08 + 1.08 (self-reported BMI); and

Corrected BMI for females = −0.12 + 1.05 (self-reported BMI).

Using cut-points according to the World Health Organization (WHO) Consultation on obesity,Footnote 11 respondents were classified into one of the following four categories based on their corrected BMI (kg/m2): underweight (less than 18.5), normal (18.5–24.9), overweight (25.0–29.9) and obese (30.0 or more).

Smoking status

Respondents were classified as a daily smoker based on their response to the following question: “At the present time, do you smoke cigarettes daily, occasionally or not at all?” (response options: “daily”, “occasionally”, “not at all”).

Alcohol consumption

Respondents were asked about the frequency with which they drank alcohol in the past 12 months, i.e. “During the past 12 months, how often did you drink alcoholic beverages?” (response options: “less than once a month”, “once a month”, “2 to 3 times a month”, “once a week”, “2 to 3 times a week”, “every day”, “not applicable”) and classified as daily drinkers if they responded that they drank “every day.”

Health status

For health status, we included the number of nonosteoporosis physical chronic conditions based on responses to questions regarding specific health conditions that were expected to last or had already lasted six months or more, and had been diagnosed by a health professional. The conditions included were arthritis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, stroke, bowel disorder and Alzheimer disease/other dementia. A summary measure was computed by summing the number of conditions and then categorizing as follows: none, 1–2 and 3+.

Osteoporosis screening, prevention and management strategies

The osteoporosis screening, prevention and management strategies included receipt of a bone density test, use of vitamin D and calcium supplements, regular physical activity and having been prescribed osteoporosis medication(s).

Bone density test

Respondents were asked if they had had a bone density test of the spine (lower back) or hip (response options: “yes”, “no”). A bone density test for osteoporosis was described as a test using a special x-ray device called dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA).

Supplements

Respondents were asked if they took calcium supplements (“yes”, “no”) and/or vitamin D supplements (“yes”, “no”).

Physical activity

Respondent’s level of physical activity was based on the Leisure Time Physical Activity Index, which categorizes a respondent as being “active”, “moderately active”, or “inactive” in their leisure time according to their total daily energy expenditure (EE) value (kcal/kg/day).Footnote 8 The respondent’s total daily EE is calculated by determining their average daily EE for each leisure time physical activity in the previous three months using their self-reported frequency and duration of a variety of leisure time activities,Footnote § as well as the metabolic energy cost of each activity. The respondent’s total daily EE is the sum of their average daily EE of all leisure time activities. Respondents that were categorized as being “active” had a total daily EE value of ≥ 3 kcal/kg/day; “moderately active” 1.5 to 2.9 kcal/kg/day; and “inactive” < 1.5 kcal/kg/day.

Osteoporosis medications

Respondents that answered “yes”, “don’t know” or refused to answer the question “Has a doctor ever told you that you had osteoporosis, sometimes called thin or brittle bones?” were asked if they were prescribed medication for osteoporosis (“yes”, “no”).

Statistical analysis

We carried out descriptive analyses to determine the prevalence estimates of self-reported diagnosed osteoporosis and major fracture history. We conducted cross-tabulation analyses to describe the sociodemographic, behavioural risk/protective factors, health characteristics and use of osteoporosis screening, prevention and management strategies according to four mutually exclusive risk subgroups based on osteoporosis diagnosis status and major fracture history. We used chi-square tests to explore the relationship between the four subgroups and respondents’ characteristics (categorical variables only) as well as respondents’ uptake of the described osteoporosis strategies. Finally, we conducted multivariate logistic regression analyses to examine factors independently associated with the use of the aforementioned osteoporosis strategies. Approximately 16% of the original data in the models were missing. Analyses were performed using respondents with complete data only. Statistical significance was determined at the p-value < .05 level.

We used SAS Enterprise Guide, version 5.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for all data analyses. All estimates are based on weighted data. Sample weights were created by Statistics Canada so that the data would be representative of the Canadian household population aged 40 years and older living in the 10 provinces in 2009 and were adjusted to compensate for nonresponse to the 2009 CCHS-ORR.Footnote 8 Estimates were age-standardized using the 2011 Canadian population in order to minimize the effects of differences in age composition when comparing estimates of the four risk subgroups.Footnote 12 Variance estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using bootstrap weights provided with the data and using the bootstrap technique to account for the complex survey design.Footnote 8Footnote 13In accordance with Statistics Canada’s release guidelines, only results with a coefficient of variation less than 33.3% are reported. If high sampling variability (i.e. coefficient of variation between 16.6% and 33.3%) is associated with any of the estimates reported in Tables 1 and 2, a superscript “a” is used to indicate that the estimate must be interpreted with caution. Note that weighted estimates based on sample sizes of less than 10 observations are not reportable regardless of the value of the coefficient of variation.Footnote 8

| Sociodemographic, risk and protective factors and health characteristics | Overall (100%) |

BOTH osteoporosis diagnosis and major fracture (2.2%) |

Osteoporosis diagnosis ONLY (and no major fracture) (7.9%) |

Major fracture ONLY (and no osteoporosis diagnosis) (6.7%) |

NEITHER osteoporosis diagnosis nor major fracture (83.2%) |

χ2 p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | ||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Mean age | 57.5 (57.3–57.7) |

70.0 (67.3–72.7) |

64.1 (62.4–65.7) |

63.8 (61.4–66.1) |

56.1 (55.8–56.3) |

n/a |

| Age group | ||||||

| 40–64 | 72.9 (72.5–73.3) |

33.7 (22.6–44.8) Footnote a |

55.9 (48.4–63.4) |

52.1 (43.7–60.4) |

77.2 (76.3–78.1) |

< .001 |

| 65+ | 27.1 (26.7–27.5) |

66.3 (55.2–77.4) |

44.1 (36.6–51.6) |

47.9 (39.6–56.3) |

22.8 (21.9–23.7) |

< .001 |

| Sex (females) | 51.6 (51.2–52.0) |

91.1 (85.3–96.9) |

78.1 (70.6–85.7) |

55.4 (47.6–63.2) |

47.7 (46.7–48.7) |

< .001 |

| Cultural/racial background (White) | 86.4 (84.5–88.3) |

93.0 (87.0–99.1) |

87.2 (79.6–94.8) |

88.3 (81.1–95.5) |

86.0 (84.0–88.0) |

.658 |

| Highest level of education (postsecondary graduation) | 58.3 (56.2–60.3) |

45.1 (31.9–58.2) |

49.3 (41.9–56.6) |

53.5 (45.5–61.6) |

59.8 (57.6–62.1) |

.004 |

| Household income adequacy quintile | ||||||

| Low (Q1–Q2) | 38.1 (35.8–40.3) |

53.8 (38.2–69.4) |

54.4 (45.8–63.1) |

47.5 (39.1–56.0) |

35.5 (33.1–37.9) |

< .001 |

| Middle (Q3) | 19.5 (17.7–21.4) |

16.0 (6.3–25.7)Footnote a |

19.1 (12.5–25.8)Footnote a |

19.4 (14.4–24.3) |

19.7 (17.7–21.7) |

|

| High (Q4–Q5) | 42.4 (40.1–44.7) |

30.2 (13.1–47.3)Footnote a |

26.4 (18.8–34.0) |

33.1 (25.1–41.1) |

44.8 (42.3–47.3) |

|

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 0.8 (0.4–1.2) |

NRFootnote b | NRFootnote b | NRFootnote b | 0.8 (0.3–1.3)Footnote a |

.004 |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 29.0 (27.0–31.0) |

37.4 (25.5–49.2) |

39.3 (31.2–47.3) |

32.9 (24.0–41.8) |

27.5 (25.4–29.6) |

.004 |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 43.4 (41.2–45.6) |

45.1 (31.6–58.6) |

32.1 (24.8–39.3) |

41.6 (33.7–49.6) |

44.5 (42.2–46.9) |

.004 |

| Obese (≥ 30.0) | 26.8 (24.9–28.7) |

16.8 (8.7–24.8)Footnote a |

27.6 (20.0–35.2) |

24.8 (18.1–31.5) |

27.2 (25.1–29.2) |

.004 |

| Smoking status (daily) | 15.4 (13.9–16.8) |

10.6 (4.4–16.9)Footnote a |

13.3 (9.1–17.4) |

13.0 (8.0–17.9)Footnote a |

15.9 (14.2–17.5) |

.300 |

| Alcohol consumption (daily) | 11.7 (10.3–13.0) |

NRFootnote b | 8.7 (4.6–12.8)Footnote a |

13.3 (7.6–19.0)Footnote a |

11.9 (10.3–13.4) |

.528 |

| Number of nonosteoporosis physical chronic conditions: | ||||||

| None | 59.1 (57.2–61.0) |

21.6 (11.9–31.2)Footnote a |

32.0 (25.1–38.8) |

41.4 (33.5–49.3) |

64.1 (62.2–65.9) |

< .001 |

| 1–2 | 35.7 (33.7–37.6) |

62.7 (50.7–74.6) |

56.8 (49.1–64.6) |

49.8 (42.0–57.5) |

31.8 (29.9–33.7) |

< .001 |

| 3+ | 5.2 (4.4–6.0) |

15.8 (6.8–24.7)Footnote a |

11.2 (6.5–15.9)Footnote a |

8.8 (4.6–13.0)Footnote a |

4.1 (3.4–4.8) |

< .001 |

Data source: 2009 Canadian Community Health Survey—Osteoporosis Rapid Response.

|

||||||

| Screening, prevention and management strategies | Overall | BOTH osteoporosis diagnosis and major fracture | Osteoporosis diagnosis ONLY (and no major fracture) | Major fracture ONLY (and no osteoporosis diagnosis) | NEITHER osteoporosis diagnosis nor major fracture | χ2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both sexes % (95% CI) |

Both sexes % (95% CI) |

Both sexes % (95% CI) |

Both sexes % (95% CI) |

Both sexes % (95% CI) |

Both sexes p-value |

|||||||

| Females % (95% CI) |

Males % (95% CI) |

Females % (95% CI) |

Males % (95% CI) |

Females % (95% CI) |

Males % (95% CI) |

Females % (95% CI) |

Males % (95% CI) |

Females % (95% CI) |

Males % (95% CI) |

Females p-value |

Males p-value |

|

| Bone density test | 27.8 (26.3–29.2) |

89.1 (82.5–95.7) |

85.9 (81.2–90.6) |

33.4 (26.6–40.2) |

20.2 (18.5–21.8) |

< .001 | ||||||

| 44.6 (42.3–46.6) |

9.9 (7.9–11.8) |

88.5 (81.3–95.7) |

94.9 (85.7–100) |

91.5 (88.6–94.3) |

66.0 (48.1–83.9) |

47.8 (36.6–59.1) |

15.5 (9.0–22.1)Footnote a |

34.6 (32.0–37.3) |

6.9 (5.2–8.5) |

< .001 | < .001 | |

| Vitamin D supplements | 41.5 (39.5–43.5) |

89.2 (83.3–95.0) |

68.5 (60.0–77.0) |

45.2 (37.3–53.0) |

37.5 (35.3–39.6) |

< .001 | ||||||

| 53.1 (50.3–56.0) |

29.1 (26.4–31.9) |

90.2 (84.4–96.1) |

78.6 (51.0–100)Footnote a |

72.8 (64.7–80.9) |

53.0 (31.4–74.7)Footnote a |

59.7 (48.1–71.2) |

27.2 (18.3–36.1)Footnote a |

47.7 (44.4–50.9) |

28.1 (25.2–30.9) |

< .001 | .001 | |

| Calcium supplements | 39.4 (37.5–41.3) |

90.7 (85.1–96.4) |

81.7 (76.5–86.9) |

40.7 (32.9–48.5) |

34.0 (32.0–36.0) |

< .001 | ||||||

| 54.9 (52.0–57.7) |

22.9 (20.4–25.5) |

92.8 (87.9–97.7) |

69.6 (38.2–100)Footnote a |

87.8 (83.7–91.8) |

60.2 (40.8–79.6) |

55.7 (44.0–67.4) |

21.9 (13.6–30.3)Footnote a |

47.8 (44.6–51.1) |

21.3 (18.8–23.8) |

< .001 | < .001 | |

| Regular physical activityFootnote c | 42.0 (39.8–44.2) |

37.0 (23.1–51.0)a |

29.4 (23.2–35.7) |

44.6 (36.3–52.9) |

43.1 (40.7–45.5) |

.003 | ||||||

| 40.7 (37.7–43.7) |

43.3 (40.2–46.5) |

35.5 (20.4–50.6)Footnote a |

NRFootnote b | 31.2 (24.3–38.2) |

23.0 (8.8–37.3)Footnote a |

43.9 (31.8–56.1) |

45.5 (35.2–55.9) |

42.2 (38.8–45.6) |

43.9 (40.6–47.3) |

.089 | .031 | |

| Osteoporosis medication | 59.3 (53.0–65.7) |

69.5 (58.7–80.4) |

56.5 (49.1–63.9) |

n/a | n/a | .059 | ||||||

| 64.8 (58.9–70.8) |

36.2 (18.5–54.0) |

69.0 (57.1–80.8) |

NRFootnote b | 63.5 (56.3–70.6) |

31.8 (12.4–51.1)Footnote a |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

Data source: 2009 Canadian Community Health Survey—Osteoporosis Rapid Response.

|

||||||||||||

Results

Prevalence of diagnosed osteoporosis and major fracture history

In 2009, 10.1% of Canadians aged 40 years and older (an estimated 1.5 million people) reported having been diagnosed with osteoporosis (Table 1). Of these individuals, 80.9% were female, and 21.7% reported having had a major fracture. Additionally, 6.7% of Canadians aged 40 years and older (an estimated 1.0 million people) reported having had a major fracture but not having been diagnosed with osteoporosis; of these, 55.4% were female.

Sociodemographics, behavioural risk/protective factors, health characteristics, and use of osteoporosis screening, prevention and management strategies

We found important differences in the individuals’ characteristics between the four risk subgroups (Table 1). Increasing age, being female, decreasing levels of education and household income, lower BMI and increasing number of nonosteoporosis physical chronic conditions were associated with having an osteoporosis diagnosis and major fracture history.

Furthermore, we found differences in bone density testing, calcium, vitamin D and physical activity between the four risk subgroups (Table 2). Overall, bone density testing was reported by a minority (27.8%) of Canadians aged 40 years and older, but by an overwhelming majority (over 85%) of those with an osteoporosis diagnosis. Canadians with diagnosed osteoporosis with and without prior major fracture also had high self-reported use of vitamin D supplements (89.2% and 68.5%, respectively) or calcium supplements (90.7% and 81.7%, respectively). In contrast, less than 40% reported regular physical activity. In addition, the majority of respondents diagnosed with osteoporosis reported having been prescribed osteoporosis medication(s) (59.3% overall) and this was slightly higher for those with (as opposed to without) prior major fracture (69.5% and 56.5%, respectively). Among respondents who had not been diagnosed with osteoporosis but reported having had a major fracture at one of the common osteoporotic sites, one-third (33.4%) reported having had a bone density test, fewer than half reported taking vitamin D supplements (45.2%) or calcium supplements (40.7%), or regular physical activity (44.6%). Sex-stratified results demonstrated that all screening, prevention and management strategies were more common among women than men, with the exception of physical activity.

Age-standardized estimates related to screening, prevention and management strategies were consistently lower than the crude for all the risk subgroups with the exception of those with neither an osteoporosis diagnosis nor a prior major fracture (available from the author upon request).

Factors independently associated with use of screening, prevention and management strategies

After adjusting for all sociodemographic factors, risk and protective factors and health characteristics,Footnote ** results demonstrated that factors independently associated with the use of osteoporosis prevention and management strategies varied by type of strategy (Table 3). Older age was positively associated with having received a bone density test and use of vitamin D and calcium supplements. Being male was negatively associated with all strategies except for regular physical activity, which was not associated with osteoporosis strategies for either sex. Having a lower level of education and lower household income were negatively associated with use of calcium and vitamin D supplements, and both were negatively associated with regular physical activity. Being obese (vs. normal weight) and a daily smoker were negatively associated with use of vitamin D supplements, calcium supplements and regular physical activity. The number of nonosteoporosis physical chronic conditions was positively associated with all strategies with the exception of regular physical activity. Major fracture history, despite being an important risk factor for future fractures, was not associated with any strategy with the exception of vitamin D supplements.

| Factors | Bone density test | Vitamin D supplements | Calcium supplements | Regular physical activityFootnote a | Osteoporosis medication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted ORFootnote b (95% CI), p-value | |||||

| Age group (years) | |||||

| 65+ | 3.0 (2.3–4.0), < .001Footnote c | 1.7 (1.4–2.1), < .001Footnote c | 1.6 (1.2–2.0), ≤ .001Footnote c | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 1.6 (0.8–3.0) |

| 40–64 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 0.1 (0.1–0.2), < .001Footnote c | 0.4 (0.3–0.5), < .001Footnote c | 0.2 (0.2–0.3), < .001Footnote c | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.3 (0.1–0.7), .003Footnote c |

| Female | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Cultural/racial background | |||||

| Non-White | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 1.2 (0.9–1.8) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 3.9 (0.6–23.5) |

| White | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Highest level of education | |||||

| Less than postsecondary | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0), .030Footnote c | 0.7 (0.6–0.9), .001Footnote c | 1.1 (0.6–2.2) |

| Postsecondary | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Household income adequacy quintile | |||||

| Low (Q1–Q2) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9), .004Footnote c | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9), .003Footnote c | 0.9 (0.4–1.9) |

| Middle (Q3) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.6 (0.5–0.9), .003Footnote c | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.6 (0.2–1.4) |

| High (Q4–Q5) | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 0.9 (0.2–3.6) | 1.8 (0.4–8.1) | 0.7 (0.2–2.4) | 1.2 (0.3–5.7) | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) |

| Obese (> 30.0) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.6 (0.5–0.8), .001Footnote c | 0.6 (0.5–0.8), ≤ .001Footnote c | 0.5 (0.4–0.6), < .001Footnote c | 0.9 (0.4–2.1) |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Daily smoker | |||||

| Yes | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.5 (0.4–0.7), < .001Footnote c | 0.6 (0.4–0.8), .001Footnote c | 0.5 (0.4–0.7), < .001Footnote c | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) |

| No | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Daily drinker | |||||

| Yes | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9), .040Footnote c | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) |

| No | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Major fracture after the age of 40 | |||||

| Yes | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9), .035Footnote c | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) |

| No | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Number of nonosteoporosis physical chronic conditions | |||||

| 3+ | 2.9 (1.7–5.0), < .001Footnote c | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) | 1.7 (1.1–2.7), .018Footnote c | 0.4 (0.3–0.6), .001Footnote c | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) |

| 1–2 | 2.3 (1.7–3.0), < .001Footnote c | 1.4 (1.1–1.7), .001Footnote c | 1.8 (1.4–2.2), < .001 | 0.8 (0.6–1.0), .031Footnote c | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) |

| None | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

Data source: 2009 Canadian Community Health Survey—Osteoporosis Rapid Response.

|

|||||

Discussion

Osteoporosis and its complications are common. In 2009, approximately 10% of Canadian adults aged 40 years and older (an estimated 1.5 million people) reported having been diagnosed with osteoporosis, of which one in five also reported a major fracture history. More concerning is the large proportion of the one million Canadians aged 40 years and older at risk of osteoporosis—those with a major fracture history—that had not undergone bone density testing (approximately two-thirds) and were not engaging in lifestyle approaches recommended to maintain healthy bones (about half). Many of the factors found to be independently associated with the osteoporosis screening, prevention and management strategies studied are in keeping with what we know about those at greatest risk and those most likely to receive osteoporosis care.Footnote 2 However, the negligible effect that a prior major fracture had on any of the strategies studied (particularly bone density testing) is of great concern given that individuals with a prior osteoporosis-related fracture are known to be at greatest risk of a future fracture.Footnote 14 Prevalence estimates based on Canadian administrative health data generally corroborate the findings from this study, with approximately 11% of Canadian adults aged 40 years and older having been diagnosed with osteoporosis in 2009/10.Footnote 15

Between the release of the 2002 clinical practice guidelines and the latest update in 2010,Footnote 16there was a fundamental shift in osteoporosis care from treating low bone mineral density to preventing fractures, given the readily identifiable clinical factors that increase the risk of fracture independent of bone mineral density. As a result, the 2010 guidelines outline a more integrated approach to identify people who should be assessed for osteoporosis and recommended for treatment based on high absolute fracture risk, which incorporates clinical risk factors beyond bone mineral density.Footnote 2 Also, in order to address the well documented osteoporosis care gap among high-risk individuals,Footnote 3Footnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 7 the 2010 clinical practice guidelines concentrate on the assessment and management of women and men over age 50 who are at high risk of fragility fractures, and the integration of new tools for assessing the 10-year risk of fracture into overall management.

Indications for measuring bone density in the 2010 guidelines include advanced age, previous fragility fracture, parental hip fracture, cigarette smoking, heavy alcohol consumption, body weight under 60 kg (132 lbs), prolonged use of glucocorticoids and other bone-depleting medications, certain disease states and genetic disorders associated with bone loss.Footnote 2 Furthermore, the 2010 clinical guidelines provide recommendations regarding lifestyle approaches such as calcium and vitamin D intake and physical activity, in addition to the use of medications for the prevention and management of osteoporosis.

Future work is essential to determine if there has been a positive change in osteoporosis care in Canada as a result of implementing the latest evidence-based clinical practice guidelines and respective knowledge translation strategies.Footnote 17Footnote 18

Repeating similar questions in a future CCHS would assist in a re-evaluation of the osteoporosis care gap on a national level; alternately, the use of administrative data via the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System has the potential to achieve this on an ongoing basis.

Strengths and limitations

This study has a number of strengths, including the large, population-based sample and the administration of the survey by trained personnel using a structured format. Furthermore, it makes use of data from the only national survey to have collected information on the screening, prevention and management of osteoporosis including health determinants, lifestyle behaviours and comorbidities among Canadian adults.

However, findings should be interpreted in light of some important limitations. First, as with most population-based health surveys, the 2009 CCHS-ORR relies on self-reporting of health-related events with no third-party corroboration or verification of these self-reports. While this is the most practical method of assessing disease status in large population studies, self-reporting of health events and related information is susceptible to misclassification of the outcome or explanatory variables due to social desirability bias, recall bias and conscious nonreporting. Nevertheless, validation studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of self-reported diagnosis of osteoporosis and major osteoporotic fractures is reasonably accurate.Footnote 19Footnote 20

Second, associations between different factors can be explored; however, causal inferences cannot be drawn from the results due to the survey’s cross-sectional design.Footnote 21 For example, while the use of vitamin D and calcium supplements are associated with osteoporosis and fracture risk, we do not know whether receiving an osteoporosis diagnosis or having had a major fracture preceded the use of these prevention strategies or vice versa.

Third, while the 2009 CCHS-ORR was designed to be nationally representative, the generalizability of the findings to the entire Canadian population 40 years and older is limited due to the exclusion of the territories and some subpopulations known to be at an elevated risk of osteoporosis, including Indigenous populations living on Indian reserves or Crown landsFootnote 22 and institutionalized patients.Footnote 23

Fourth, while the majority (58.6%) of those having had at least one major fracture after the age of 40 reported it occurred as a result of a fall from a standing height or less, 23.1% reported it occurred as a result of a hard fall and 19.5% reported it was the result of other severe trauma.Footnote †† We elected to include all fractures, irrespective of the mechanism of injury, given that it is uncertain whether such trauma classifications are useful for determining whether a fracture is related to low bone density or indicates an increased risk of future fracture,Footnote 24 and given the recent shift in thinking that all fractures in older adults warrant careful evaluation in an effort to reduce the risk of future fractures.Footnote 25

Finally, we encountered analytical limitations due to available sample size when disaggregating data by specific characteristics of interest. For example, it was not possible to provide a statistical description of the population by racial/ethnic group, as the estimates for the different categories had high coefficients of variation (CV), indicating high sampling variability and estimates of unacceptable quality; therefore, we were limited to collapsing respondents into “White” or “non-White” response categories only.

Conclusions

Osteoporosis is common among Canadians 40 years of age and older, but more concerning is the large proportion at risk for osteoporosis—those with a major fracture history—who have not received a bone density test, nor engaged in lifestyle approaches recommended to help maintain healthy bones. The latest clinical practice guidelines released by Osteoporosis Canada in 2010 focus on preventing fragility fractures, as opposed to treating low bone mineral density, which represents a fundamental shift in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis and related fractures since the release of the 2002 clinical practice guidelines. The results from this study represent the most recent data of their kind and serve as a benchmark for the nationwide use of osteoporosis screening, prevention and management strategies among Canadians aged 40 years and older. Based on 2009 CCHS-ORR data captured one year prior to the release of the 2010 clinical practice guidelines, the findings within provide the necessary historical information to evaluate whether the release of these guidelines has had a positive impact on osteoporosis care in Canada.

Acknowledgements

Osteoporosis Surveillance Expert Working Group: Jacques Brown, David Hanley, Susan Jaglal, Sonia Jean, Famida Jiwa, Stephanie Kaiser, David Kendler, William Leslie, Louise McRae, Suzanne Morin, Siobhan O’Donnell, Jay Onysko, Alexandra Papaioannou and Kerry Siminoski.

Kate Zhang, from the Alberta & Northwest Territory Region of the Public Health Agency of Canada, provided analytic support in the initial stages of this project.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or commercial or not-for-profit organization.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Authors’ contributions and statement

SO contributed to the study design, conducted the statistical analysis, assisted with the interpretation of the data and drafted and revised the manuscript. Members of the Osteoporosis Surveillance Expert Working Group contributed to the study design, assisted with the interpretation of data, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved its submission.

The conclusions in this manuscript reflect the opinions of individual experts and not their affiliated organizations.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Melton LJ 3rd. Epidemiology worldwide. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32(1):1-13.

- Footnote 2

-

Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, et al; Scientific Advisory Council of Osteoporosis Canada. 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ. 2010;182(17):1864-73.

- Footnote 3

-

Papaioannou A, Giangregorio L, Kvern B, et al. The osteoporosis care gap in Canada. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-5-11.

- Footnote 4

-

Bessette L, Ste-Marie LG, Jean S, et al. The care gap in diagnosis and treatment of women with a fragility fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:79-86.

- Footnote 5

-

Papaioannou A, Kennedy CC, Ioannidis G, et al. The osteoporosis care gap in men with fragility fractures: the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(4):581-7.

- Footnote 6

-

Leslie WD, LaBine L, Klassen P, et al. Closing the gap in postfracture care at the population level: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2012;184(3):290-6.

- Footnote 7

-

Leslie WD, Giangregorio LM, Yogendran M, et al. A population-based analysis of the post-fracture care gap 1996-2008: the situation is not improving. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(5):1623-9.

- Footnote 8

-

Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS)—Annual Component: user guide - 2009 microdata files. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2010.

- Footnote 9

-

Connor Gorber S, Shields M, Tremblay MS, et al. The feasibility of establishing correction factors to adjust self-reported estimates of obesity. Health Rep. 2008;19(3):71-82.

- Footnote 10

-

Shields M, Connor Gorber S, Tremblay MS. Estimates of obesity based on self-report versus direct measures. Health Rep. 2008;19(2):61-76.

- Footnote 11

-

World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic [Internet]. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization; 2000 [cited 2018 Mar 20]. 252 p. Available from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/obesity/WHO_TRS_894/en/

- Footnote 12

-

Curtin LR, Klein RJ. Direct standardization (age-adjusted death rates). Healthy People 2000: [Statistical Notes, No. 6—Revised.] Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 1995.

- Footnote 13

-

Rust KF, Rao JN. Variance estimation for complex surveys using replication techniques. Stats Methods Med Res. 1996;5(3):281-310.

- Footnote 14

-

Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, et al. A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone. 2004;35(2):375-82.

- Footnote 15

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Public Health Infobase: Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System. [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2017 June 06 [cited 2018 Mar 20]. Available from: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/ccdss/data-tool/

- Footnote 16

-

Brown JP, Josse RG; Scientific Advisory Council of the Osteoporosis Society of Canada. 2002 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada. CMAJ. 2002;167(10 Suppl):S1-S34.

- Footnote 17

-

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13-24.

- Footnote 18

-

Kastner M, Bhattacharyya O, Hayden L, et al. Guideline uptake is influenced by six implementability domains for creating and communicating guidelines: a realist review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(5):498-509.

- Footnote 19

-

Peeters GM, Tett SE, Dobson AJ, et al. Validity of self-reported osteoporosis in mid-age and older women. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(3):917-27.

- Footnote 20

-

Ivers RQ, Cumming RG, Mitchell P, et al. The accuracy of self-reported fractures in older people. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(5):452-7.

- Footnote 21

-

Bland JM. An introduction to medical statistics. 4th ed. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2015. 464 p.

- Footnote 22

-

Leslie WD, Metge CJ, Weiler HA, et al. Bone density and bone area in Canadian Aboriginal women: the First Nations Bone Health Study. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(12):1755-62.

- Footnote 23

-

Zimmerman SI, Girman CJ, Buie VC, et al. The prevalence of osteoporosis in nursing home residents. Osteoporosis Int. 1999;9(2):151-7.

- Footnote 24

-

Mackey DC, Lui LY, Cawthon PM, et al; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) and Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study (MrOS) Research Groups. High-trauma fractures and low bone mineral density in older women and men. JAMA. 2007;298(20):2381-8.

- Footnote 25

-

Binkley N, Blank RD, Leslie WD, et al. Osteoporosis in crisis: it’s time to focus on fracture. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(7):1391-4.

Footnotes

- Footnote *

-

This 2014 policy statement (“TCPS2 [2014]”) is a joint policy of Canada’s three federal research agencies—the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Available from: http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/eng/policy-politique/initiatives/tcps2-eptc2/chapter2-chapitre2/#toc02-intro

- Footnote †

-

Major fracture history did not take into account the mechanism of injury.

- Footnote ‡

-

This derived variable is a distribution of respondents in deciles (10 categories including approximately the same percentage of residents for each province) based on the adjusted ratio of their total household income to the low-income cut-off corresponding to their household and community size. It provides, for each respondent, a relative measure of their household income to the household incomes of all other respondents.

- Footnote §

-

Including walking for exercise, gardening/yard work, swimming, bicycling, popular/social dance, home exercises, ice hockey, ice skating, inline skating/rollerblading, jogging/running, golfing, exercise class/aerobics, downhill skiing, bowling, baseball/softball, tennis, weight training, fishing, volleyball, basketball and up to three other categories.

- Footnote **

-

Age, sex, cultural/racial background, respondent’s level of education, adjusted household income adequacy quintile, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol consumption, major fracture after the age of 40 and number of nonosteoporosis physical chronic conditions.

- Footnote ††

-

Percentages do not add up to 100% because an individual can report more than one fracture of the major fracture sites with different mechanisms of injury.