Original quantitative research – Canadian trends in opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder from 1990 to 2014 through the lens of the Global Burden of Disease Study

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada

Heather M. Orpana, PhDReference 1,Reference 2 Note *; Justin J. Lang, PhDReference 1 Note *; Maulik Baxi, MD, MPHReference 3; Jessica Halverson, MPH, MSWReference 1; Nicole Kozloff, MD, SMReference 4,Reference 5; Leah Cahill, PhDReference 6,Reference 7,Reference 8; Samiah Alam, MScReference 6; Scott Patten, MD, PhDReference 9; Howard Morrison, PhDReference 1

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.38.6.03

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references:

- Author reference 1

-

Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

- Author reference 2

-

School of Psychology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

- Author reference 3

-

Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

- Author reference 4

-

Slaight Family Centre for Youth in Transition, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

- Author reference 5

-

Centre for Urban Health Solutions, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

- Author reference 6

-

Department of Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

- Author reference 7

-

Department of Nutrition, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

- Author reference 8

-

Department of Community Health and Epidemiology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

- Author reference 9

-

Departments of Community Health Sciences and Psychiatry, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Notes - Author reference

- Note *

-

These authors contributed equally to this work.

Correspondence: Heather M. Orpana, Applied Research Division, Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research, Public Health Agency of Canada, 785 Carling Ave, Ottawa, ON K1A 0K9; Email: heather.orpana@canada.ca

Abstract

Introduction: Several regions in Canada have recently experienced sharp increases in opioid overdoses and related hospitalizations and deaths. This paper describes opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder in Canada from 1990 to 2014 using data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study.

Methods: We used data from the GBD study to describe temporal trends (1990-2014) in opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder using common metrics: disability-adjusted life years (DALY), deaths, years of life lost (YLL) and years lived with disability (YLD). We also compared age-standardized YLL and DALY rates per 100 000 population between Canada, the USA and other regions.

Results: The age-standardized opioid-related DALY rate in Canada was 355.5 per 100 000 population in 2014, which was higher than the global rate of 193.2, but lower than the rate of 767.9 in the United States. Between 1990 and 2014, the age-standardized opioid-related YLL rate in Canada increased by 142.2%, while globally this rate decreased by 10.1%. In comparison with YLL, YLD accounted for a larger proportion of the overall opioid-related burden across all age groups. Health loss was greater for males than females, and highest among those aged 25 to 29 years.

Conclusion: The health burden associated with opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder in Canada is significant and has increased dramatically from 1990 to 2014. These data point to a need for public health action including enhanced monitoring of a range of opioid-related harms.

Keywords: opioids, substance use, health burden, DALY, dependence, mortality, years of life lost, disability-adjusted life years, death, years lived with disability

Highlights

- Long-term national trends data on opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder have not been previously presented for Canada.

- From 1990 to 2014, the age-standardized years-of-life-lost rate due to opioid-related mortality increased by 142.2%, compared to a 10.1% global decrease.

- These estimates of the health burden of disability and mortality related to opioid use are likely an underestimate. More work is needed to capture the full range of health and social consequences of opioid use.

Introduction

Canada is experiencing a public health crisis; significant and sharp increases in opioid-related overdoses and mortality in multiple regions over the last few years have prompted federal, provincial/territorial and municipal responses.Reference 1,Reference 2,Reference 3 The most recent count of apparent opioid-related mortality from national public health surveillance was 2861 in 2016. If the current trend continues, the number of opioid-related deaths in 2017 is anticipated to be greater than 4000.Reference 2 While information on opioid-related mortality is available through vital registration data and more recently through public health surveillance, no consistent national data are available on the overall burden of health loss associated with opioid use.Reference 4,Reference 5,Reference 6,Reference 7

The Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey, which reports biennially on national drug-related behaviour, does not include information on all opioids, and prevalence or frequency information does not support a full understanding of the health burden associated with drug consumption. For example, in 2015, 2% of respondents reported using psychoactive substances, including cocaine or crack, ecstasy, speed or methamphetamines, hallucinogens or heroin,8 but this does not include other forms of opioids. Of those reporting taking prescription opioids, 2% reported abusing them, which represents about 0.3% of Canadians aged 15 years and older.Reference 8 However, survey sources of data on illegal drug use likely provide underestimates of the true magnitude of the issue because of respondents' concerns around reporting drug use and the associated stigma.Reference 9 In addition, household survey methods do not reach some of the populations who may be more likely to use substances. This is particularly important when measuring the health burden disproportionately present in socially disadvantaged groups, such as people experiencing homelessness.Reference 10 Based on other sources of data, the number of people using heroin, fentanyl and other synthetic opioids is steadily rising, representing a shift from prescription to non-prescription opioid use.Reference 4,Reference 5,Reference 6 Apart from the direct health impacts of opioid use, including deaths and overdoses, other health and social harms related to opioid use include increased risk of chronic and infectious diseases and a higher risk of family problems, self-harm, problems at work and school, and contact with the criminal justice system.Reference 4,Reference 5,Reference 11,Reference 12,Reference 13

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study is an international collaborative effort to systematically quantify health loss due to more than 300 diseases, injuries and risk factors in 195 countries from 1990 to 2016.Reference 14 In this paper, we use the GBD framework to quantify the health burden of opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder in Canada from 1990 to 2014 to allow comparisons across time and regions. The purpose of this paper is to describe the burden of opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder in Canada over the last quarter century, through the lens of the GBD study, by sex and by age. A secondary goal is to compare levels and trends in Canada with those in the United States of America (USA) and those in GBD study super-regions (i.e., Southeast Asia, East Asia and Oceania; Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Central Asia; High Income; Latin America and Caribbean; North Africa and Middle East; South Asia; and Sub-Saharan Africa).Reference 14

Methods

The GBD 2016 estimates and analyses adhere to the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER).Reference 15 Comprehensive details on the GBD methodology are available in the 2016 GBD capstone papers,Reference 14,Reference 16,Reference 17 and Degenhardt et al. (2014)Reference 18 provide further details on GBD methods related to the modelling of opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder. All GBD results can be accessed online through the GBD Data Visualization Hub (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/).

Data sources

The GBD study identifies data through comprehensive systematic reviews of published and grey literature and through environmental scans of national and subnational data sources.Reference 19,Reference 20,Reference 21,Reference 22 The full list of data sources used to model Canadian GBD estimates can be found at http://ghdx.healthdata.org/geography/canada.

Estimation of mortality and years of life lost

Opioid-related mortality estimates were modelled using the Cause of Death Ensemble modelling (CODEm) statistical package. CODEm uses the best available data to model consistent estimates by using ensemble models of various techniques (linear mixed effects models, spatial-temporal models and Gaussian process regression) that incorporate temporal trends of the estimate.Reference 23

The GBD study undertakes a standard process to ensure that international data are comparable and to correct for "garbage codes" (i.e. deaths that are coded to causes that cannot cause death or are intermediate causes of death). Because of the low number of deaths due to opioid dependence (International Classification of Diseases [ICD-10] code F11), it is difficult to obtain internally consistent models that capture all mortality associated with opioid use. As a result, deaths due to accidental poisoning from narcotics were reclassified as deaths associated with opioid use, thereby collapsing ICD-10 Codes X42 and F11 into a single category (as described by Degenhardt et al., 2014Reference 18). Because not all jurisdictions capture detailed information about the specific drugs associated with drug-related deaths, the higher-level category--mortality due to drug use disorders--was modelled first. When data on specific drug-related deaths were available, such as in Canada, these data were used to distribute deaths between different types of drug-related deaths. When data on specific drug deaths were not available, other methods were used to proportionally distribute drug-related deaths between each drug included in the GBD framework.Reference 14 Garbage codes, including unintentional poisoning by exposure to other and unspecified drugs (ICD-10 X44), are redistributed proportionally to specific drugs as described in the GBD causes of death capstone paper.14 We did not distinguish between prescription and non-prescription opioid use in relation to opioid mortality.

Mortality estimates were then combined with time-invariant world standard life expectancy tables to calculate years of life lost (YLL), describing the number of years lost to premature mortality.Reference 14 The GBD study takes changes to the ICD into account by recalculating all estimates with each annual iteration and accommodating annual changes in methodology. The 2016 iteration of the GBD study incorporated Canadian mortality data up to 2012, as reported to the World Health Organization by Statistics Canada. As a result, we report GBD estimates up to 2014 because after this point, the modelled estimates do not reflect the recent, large increases in opioid-related mortality.

We also present crude mortality data from 2000 to 2014 using Canadian vital statistics (from CANSIM; Canadian Socio-Economic Information Management System), incorporating ICD-10 codes X42 (Accidental poisoning due to narcotics and hallucinogens)Reference 7 and F11 (Mental disorders due to the use of opioids).Reference 24 We extracted deaths associated with these codes and combined them into a single category--deaths related to opioid use--in order to provide data consistent with the presentation of the GBD opioid-related mortality data. Age-standardized rates were calculated using the GBD world standard population. While more recent vital statistics data for Canada are available, we have reported these to correspond with the date range of GBD estimates that we are reporting.

Estimation of years lived with disability

To estimate the prevalence of opioid use disorder in order to calculate the associated disability, we defined opioid use disorder in accordance with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR; code 304.00)Reference 25 and the ICD-10 (code F11.2)Reference 26 diagnostic criteria (as described by Degenhardt et al., 2014Reference 18). This case definition means that people experiencing morbidity associated with opioid use, but not opioid dependence, are excluded in our disability estimates.

Prevalence estimates for opioid use disorder were calculated using the Disease Modelling - Meta-Regression II (DisMod-MR II) software, which implements Bayesian meta-regression techniques to obtain internally consistent estimates.Reference 27 Obtaining accurate estimates of illegal drug use prevalence remains a major challenge because of the associated stigma and difficulties with accessing marginalized populations. As a result, indirect estimates of prevalence, based on methods such as the multiplier methods, capture-recapture and back-projection estimates, were preferred over direct sources such as surveys.Reference 28 The modelled High Income North America (i.e. Canada, USA and Greenland) estimates are based on 27 prevalence studies and two studies on remission.Reference 18

To provide a more global sample, the GBD study developed disability weights using community-based surveys conducted in five countries and open-access Internet-based surveys.Reference 29,Reference 30 Epidemiological data from a US national study were used to adjust each disability weight by severity,Reference 31 and microsimulation methods were used to account for comorbidity.Reference 16 After all corrections, the disability weight for opioid use disorder was set by the GBD study at 0.50 (95% uncertainty interval [UI]: 0.33-0.69) on a scale from 0 (no disability) to 1.0 (severe disability).Reference 18 Final prevalence estimates were multiplied by their corresponding disability weights to obtain YLD, described as the number of years that individuals lived with disability.

Disability-adjusted life years

DALYs were calculated as the sum of YLL and YLD, representing the overall burden of opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder.

Age-standardized rates for DALY were calculated using the GBD, time-invariant, world standard population. Crude (all-age) and age-standardized analyses are presented, and trend analyses use age-standardized estimates. Analyses were conducted for both sexes together and by sex. YLL and DALY are also presented for the USA and each of the seven GBD super-regions.

Uncertainty intervals

Uncertainty intervals (UIs) were established by running 1000 draws and identifying the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles for each estimate. The level of uncertainty is related to the quality of the available data and the data coverage. Narrow UIs indicate high certainty in the estimate, whereas wide UIs indicate low certainty in the estimate.

Results

General results and international comparisons

In 2014, there were 131 057.8 (95% UI: 104 713.8-159 793.1) crude DALYs from opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder. Of these, 80 893.3 (63 579.9-100 891.3) were among males and 50 164.5 (37 340.4-62 727.8) among females (data not shown).

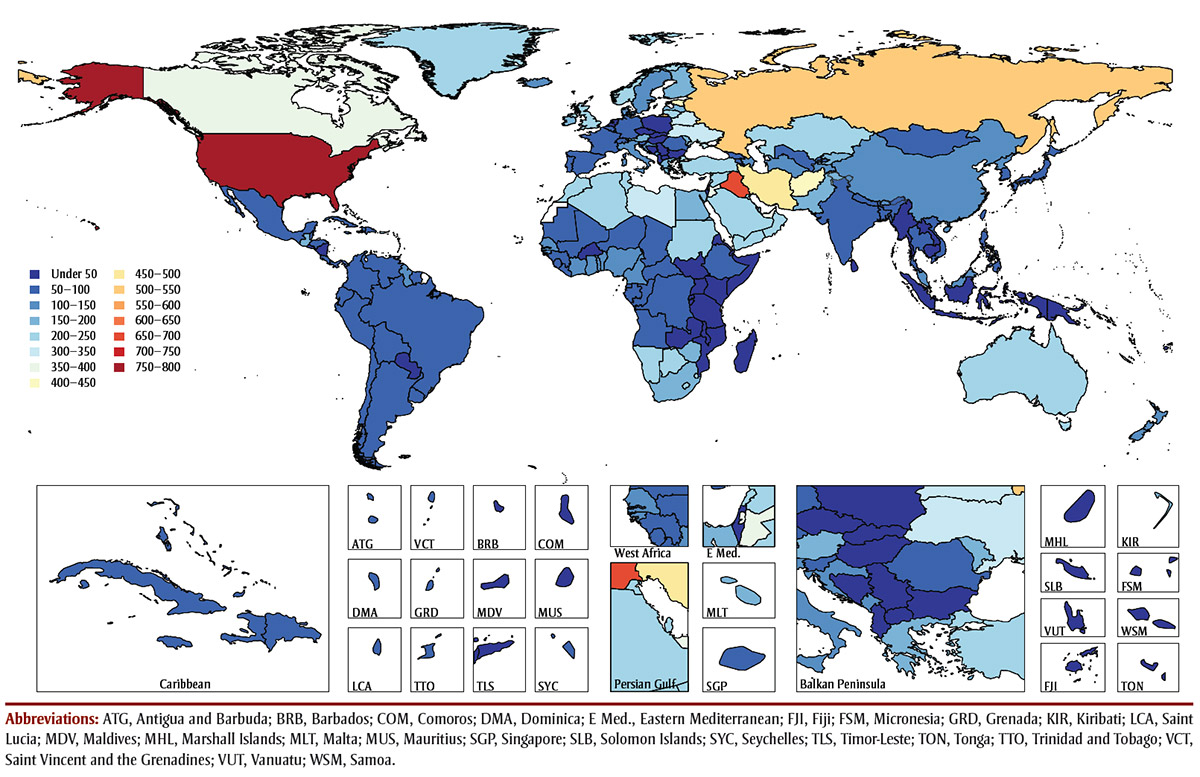

The age-standardized DALY rate for Canadian males and females combined was 355.5 per 100 000 population (95% UI: 280.8-436.3), a burden associated with opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder that was significantly higher than the global rate of 193.2 (147.5-232.5; Table 1). The burden of opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder in 2014 was concentrated in the High Income region (which includes Canada and the USA); North Africa and the Middle East; and the Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Central Asia regions (see Figure 1). The USA demonstrates the largest rates of opioid burden for both males (968.6 DALYs per 100 000; 95% UI: 746.6-1167.2) and females (565.7 DALYs per 100 000; 95% UI: 435.2-684.3), more than double the burden estimated in Canada in 2014.

| Region | Total | Females | Males | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DALY rate per 100 000 population | 95% UI | Per cent change in age-standardized rates 1990-2014 (%) | Per cent change in age-standardized rates 2004-2014 (%) | DALY rate per 100 000 population | 95% UI | Per cent change age-standardized rates 1990-2014 (%) | Per cent change age-standardized rates 2004-2014 (%) | DALY rate per 100 000 population | 95% UI | Per cent change in age-standardized rates 1990-2014 (%) | Per cent change in age-standardized rates 2004-2014 (%) | |

| Canada | 355.5 | 280.8-436.3 | 54.7 | 14.8 | 270.5 | 202.0-343.5 | 42.8 | 15.1 | 440.7 | 342.1-554.7 | 63.0 | 14.8 |

| USA | 767.9 | 612.3-915.7 | 47.5 | 18.1 | 565.7 | 435.2-684.3 | 41.8 | 18.2 | 968.6 | 746.6-1167.2 | 50.1 | 17.9 |

| Global | 193.2 | 147.5-232.5 | −4.4 | −0.9 | 136.5 | 102.7-166.1 | −7.2 | −0.9 | 249.2 | 192.0-299.4 | −3.0 | −1.9 |

| Southeast Asia, East Asia and Oceania | 145.0 | 111.5-176.1 | −27.9 | −8.0 | 108.4 | 83.2-133.1 | −33.0 | −6.6 | 181.2 | 138.4-217.3 | −24.5 | −8.9 |

| Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 298.6 | 254.8-344.5 | −8.9 | −18.2 | 151.4 | 119.9-179.2 | −10.9 | −16.3 | 452.0 | 385.7-522.4 | −8.9 | −19.1 |

| High Incometable 1 note a | 346.6 | 274.9-417.1 | 36.3 | 14.4 | 252.3 | 193.6-304.2 | 34.9 | 15.6 | 440.1 | 347.8-530.3 | 36.6 | 13.5 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 116.3 | 86.8-145.7 | 13.6 | 3.8 | 88.9 | 64.7-113.1 | 10.0 | 4.5 | 144.6 | 109.9-179.2 | 15.9 | 3.2 |

| North Africa and Middle East | 330.7 | 234.1-414.0 | 13.5 | −0.0 | 216.8 | 153.2-288.8 | 8.4 | 3.2 | 438.0 | 310.5-534.9 | 15.3 | −1.8 |

| South Asia | 147.8 | 107.6-185.6 | 13.0 | 10.2 | 111.8 | 80.4-141.6 | 13.4 | 9.1 | 182.2 | 133.4-230.1 | 13.4 | 11.1 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 136.5 | 102.3-168.2 | −7.9 | −5.6 | 93.2 | 67.3-120.8 | −10.5 | −8.6 | 180.8 | 139.6-218.2 | −6.6 | −3.9 |

|

Abbreviations: DALY, disability-adjusted life years; UI, uncertainty interval. Table 1 Notes

|

||||||||||||

Figure 1 - Text description

The age-standardized disability-adjusted life year (DALY) rate for Canadian males and females combined was 355.5 per 100 000 (95% UI: 280.8-436.3), a burden associated with opioid use disorder and opioid-related mortality that was significantly higher than the global rate of 193.2 (147.5-232.5). In this figure, which shows a map of the world, we can see that the burden of opioid use-related disability and opioid-related mortality in 2014 was concentrated in the High Income region (which includes Canada and the USA); North Africa and the Middle East; and the Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Central Asia regions. The USA demonstrates the largest rates of opioid burden for both males (968.6 DALYs per 100 000; 95% UI: 746.6-1167.2) and females (565.7 DALYs per 100 000; 95% UI: 435.2-684.3), more than double the burden estimated in Canada in 2014.

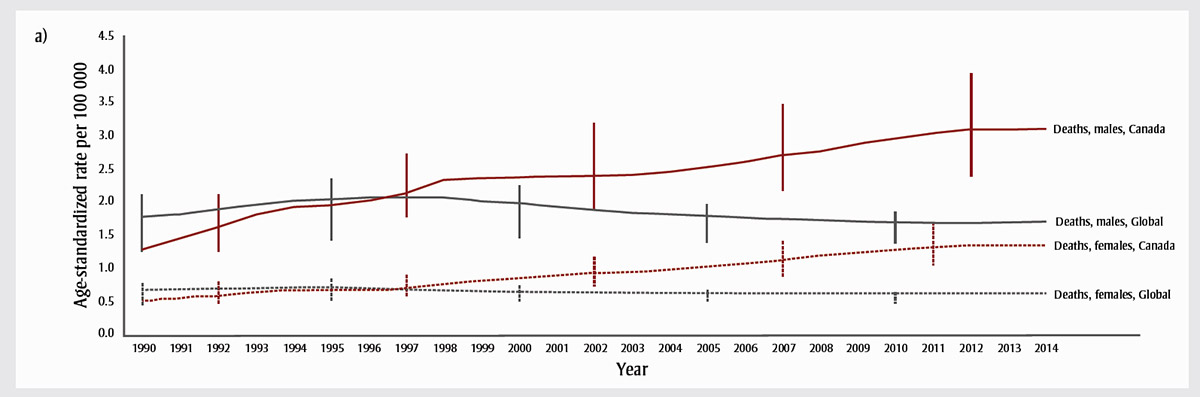

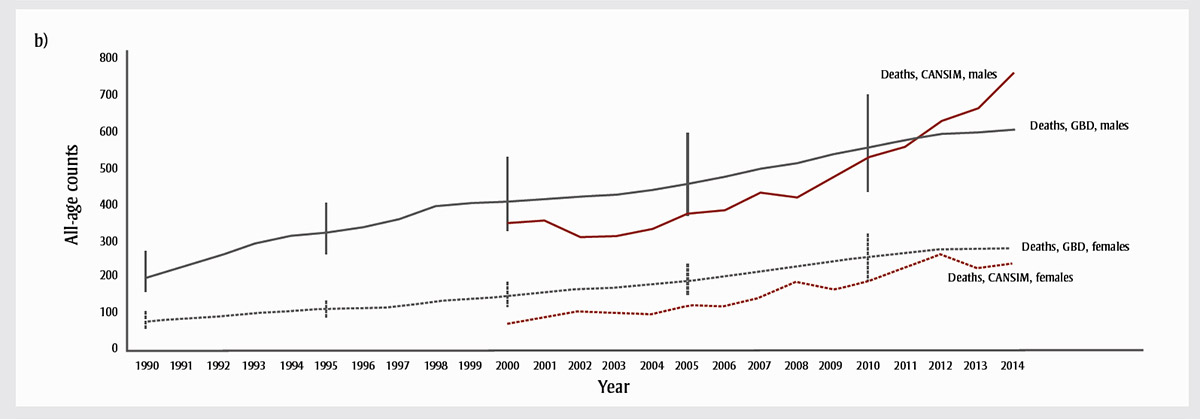

Age-standardized opioid-related mortality rates increased substantially among males, from 1.3 per 100 000 (95% UI: 1.0-1.7) in 1990 to 3.1 (2.3-4.1) in 2014, whereas rates among females rose from 0.5 (0.4-0.7) to 1.3 (1.0-1.8) between 1990 and 2014 (Figure 2). The crude opioid-related mortality count increased from 201.1 per 100 000 (157.0-271.9) in 1990 to 606.6 (454.3-805.6) in 2014 among males, and from 76.7 (59.9-105.6) in 1990 to 279.2 (210.9-361.7) in 2014 among females. For the most part, observed Canadian data from vital statistics fall within the GBD estimates of 95% UIs. However, in 2011, the observed data for males surpassed the GBD modelled estimates, and this trend continued through the rest of the time series.

Figure 2a - Text description

Figure 2a shows that age-standardized opioid-related mortality rates increased substantially among males, from 1.3 per 100 000 (95% UI: 1.0-1.7) in 1990 to 3.1 (2.3-4.1) in 2014, whereas rates among females rose from 0.5 (0.4-0.7) to 1.3 (1.0-1.8) between 1990 and 2014.

| Category | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths, males, Canada | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| Deaths, males, Global | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Deaths, females, Canada | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Deaths, females, Global | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

Figure 2b - Text description

Figure 2b depicts the crude opioid-related mortality count, which according to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) increased from 201.1 per 100 000 (157.0-271.9) in 1990 to 606.6 (454.3-805.6) in 2014 among males, and from 76.7 (59.9-105.6) in 1990 to 279.2 (210.9-361.7) in 2014 among females. For the most part, observed Canadian data from vital statistics fall within the GBD estimates' of 95% UIs. However, in 2011, the observed data for males surpassed the GBD modelled estimates, and this trend continued through the rest of the time series.

| Category | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths, CANSIM, males | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 349.0 | 355.0 | 310.0 | 313.0 | 334.0 | 375.0 | 384.0 | 433.0 | 420.0 | 473.0 | 531.0 | 559.0 | 629.0 | 664.0 | 760.0 |

| Deaths, GBD, males | 201.1 | 231.2 | 260.4 | 294.8 | 315.9 | 324.6 | 339.5 | 361.5 | 396.9 | 405.2 | 410.2 | 415.9 | 422.9 | 428.3 | 441.0 | 458.0 | 477.2 | 499.2 | 514.2 | 538.6 | 558.6 | 577.0 | 594.3 | 598.2 | 606.6 |

| Deaths, CANSIM, females | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 73.0 | 92.0 | 107.0 | 102.0 | 98.0 | 122.0 | 117.0 | 143.0 | 191.0 | 167.0 | 194.0 | 230.0 | 262.0 | 224.0 | 239.0 |

| Deaths, GBD, females | 76.7 | 85.3 | 91.4 | 101.5 | 106.8 | 110.9 | 113.8 | 118.3 | 131.1 | 141.0 | 149.1 | 157.1 | 166.2 | 171.0 | 178.1 | 189.3 | 200.7 | 215.9 | 232.1 | 244.0 | 254.9 | 264.5 | 275.0 | 276.2 | 279.2 |

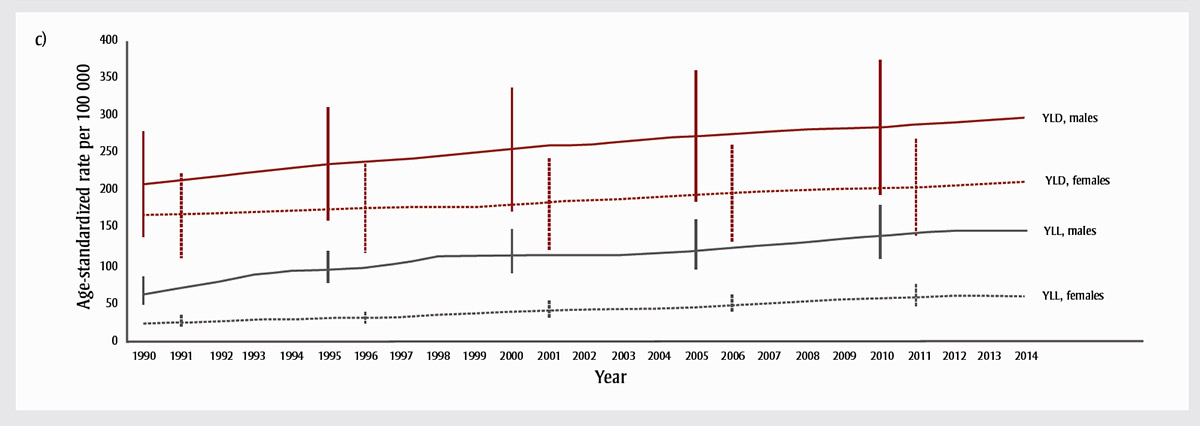

Figure 2c - Text description

Figure 2c illustrates the age-standardized years of life lost (YLL) rate for Canadians, which, in 2014, was much higher among males (146.3; 109.6-195.9) than among females (59.8; 45.1-79.4). We can see the increasing trends in YLL and YLD for both males and females, which together demonstrate a slow but steady increase from 1990 to 2014, resulting in large overall percentage increases. The increase is greater in YLL, reflecting the impact of an increasing number of deaths at younger ages. For both sexes, the YLL rate in Canada increased by 142.2% between 1990 and 2014, with a 28.2% increase between 2004 and 2014.

| Category | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YLD, males | 208.2 | 212.9 | 218.5 | 224.2 | 228.3 | 233.6 | 237.1 | 241.2 | 245.5 | 249.6 | 253.2 | 258.0 | 259.9 | 263.1 | 267.8 | 271.8 | 273.8 | 276.6 | 279.6 | 281.4 | 282.7 | 286.1 | 288.4 | 292.0 | 294.6 | 297.9 | 300.0 |

| YLD, females | 166.6 | 167.9 | 169.5 | 171.0 | 172.0 | 173.0 | 175.0 | 176.8 | 178.9 | 178.3 | 179.9 | 183.1 | 186.5 | 187.9 | 191.0 | 193.1 | 195.0 | 197.9 | 198.7 | 201.2 | 203.0 | 204.1 | 206.5 | 208.9 | 210.7 | 211.7 | 213.4 |

| YLL, males | 62.1 | 70.6 | 78.3 | 87.7 | 93.2 | 94.4 | 97.7 | 103.0 | 112.2 | 113.6 | 113.5 | 113.5 | 113.7 | 114.0 | 116.2 | 119.7 | 123.3 | 127.7 | 130.4 | 135.5 | 139.5 | 143.3 | 146.1 | 145.6 | 146.3 | 147.1 | 147.4 |

| YLL, females | 22.8 | 25.1 | 26.6 | 29.0 | 29.9 | 30.8 | 31.1 | 32.1 | 35.3 | 37.6 | 39.1 | 40.6 | 42.4 | 43.0 | 44.0 | 46.0 | 47.7 | 50.2 | 53.1 | 55.3 | 57.1 | 58.7 | 60.2 | 59.9 | 59.8 | 59.9 | 59.5 |

Abbreviations: CANSIM, Canadian Socio-Economic Information Management System; GBD, Global Burden of Disease; YLD, years lived with disability; YLL, years of life lost.

Note: Vertical bars represent the 95% uncertainty intervals.

The age-standardized YLL rate for Canadians (both sexes combined) was 103.1 per 100 000 (95% UI: 83.5-129.9) (Table 2). This rate was much higher among males (146.3; 109.6-195.9) than among females (59.8; 45.1-79.4). Figure 2 highlights the increasing trends in YLL and YLD for both males and females, which together demonstrate a slow but steady increase from 1990 to 2014, resulting in large overall percentage increases. The increase is greater in YLL, reflecting the impact of an increasing number of deaths at younger ages. For both sexes, the YLL rate in Canada increased by 142.2% between 1990 and 2014, with a 28.2% increase between 2004 and 2014. In contrast, the global YLL rate decreased by 10.1% from 1990 to 2014, with an 8.6% decrease between 2004 and 2014 (Table 2).

| Region | Total | Females | Males | Per cent change in (total) age-standardized YLL rates (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YLL rate per 100 000 | 95% UI | Prevalence | 95% UI | YLL rate per 100 000 | 95% UI | Prevalence | 95% UI | YLL rate per 100 000 | 95% UI | Prevalence | 95% UI | 1990-2014 | 2004-2014 | |

| Canada | 103.1 | 83.5-129.9 | 0.7 | 0.6-0.8 | 59.8 | 45.1-79.4 | 0.5 | 0.5-0.7 | 146.3 | 109.6-195.9 | 0.8 | 0.7-0.9 | 142.2 | 28.2 |

| USA | 265.0 | 123.2-294.5 | 1.3 | 1.2-1.5 | 164.2 | 67.0-185.0 | 1.1 | 0.9-1.2 | 364.6 | 145.3-409.7 | 1.7 | 1.5-1.8 | 343.2 | 48.6 |

| Global | 47.6 | 39.8-51.0 | 0.4 | 0.3-0.4 | 23.6 | 18.9-25.6 | 0.3 | 0.2-0.3 | 71.2 | 57.8-79.5 | 0.4 | 0.4-0.5 | −10.1 | −8.6 |

| Southeast Asia, East Asia and Oceania | 35.9 | 30.5-48.6 | 0.3 | 0.2-0.3 | 20.7 | 15.5-24.8 | 0.2 | 0.2-0.3 | 50.8 | 40.4-76.2 | 0.3 | 0.3-0.4 | −43.9 | −12.2 |

| Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 150.8 | 129.7-179.1 | 0.4 | 0.3-0.4 | 48.4 | 40.9-62.4 | 0.3 | 0.2-0.3 | 257.3 | 215.0-309.4 | 0.5 | 0.5-0.6 | −8.3 | −25.7 |

| High Incometable 2 note a | 107.5 | 60.0-116.5 | 0.6 | 0.6-0.7 | 61.6 | 31.7-67.7 | 0.5 | 0.4-0.5 | 152.8 | 77.7-167.1 | 0.8 | 0.7-0.8 | 147.8 | 32.5 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 19.9 | 17.8-24.6 | 0.2 | 0.2-0.3 | 9.1 | 8.2-11.2 | 0.2 | 0.2-0.2 | 30.8 | 27.0-39.7 | 0.3 | 0.2-0.3 | 43.3 | 6.2 |

| North Africa and Middle East | 41.3 | 30.1-49.5 | 0.7 | 0.6-0.9 | 13.0 | 9.2-16.2 | 0.5 | 0.4-0.6 | 68.0 | 46.9-82.4 | 0.9 | 0.8-1.1 | 18.5 | −11.9 |

| South Asia | 20.3 | 17.2-24.2 | 0.3 | 0.3-0.4 | 11.1 | 8.8-13.7 | 0.2 | 0.2-0.3 | 29.1 | 22.7-36.9 | 0.4 | 0.3-0.4 | 6.0 | −3.9 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 30.5 | 24.2-37.7 | 0.3 | 0.2-0.3 | 10.6 | 8.9-13.7 | 0.2 | 0.2-0.3 | 50.7 | 36.2-65.1 | 0.3 | 0.3-0.4 | −21.1 | −16.6 |

|

Abbreviations: YLL, years of life lost; UI, uncertainty interval. Table 2 Notes

|

||||||||||||||

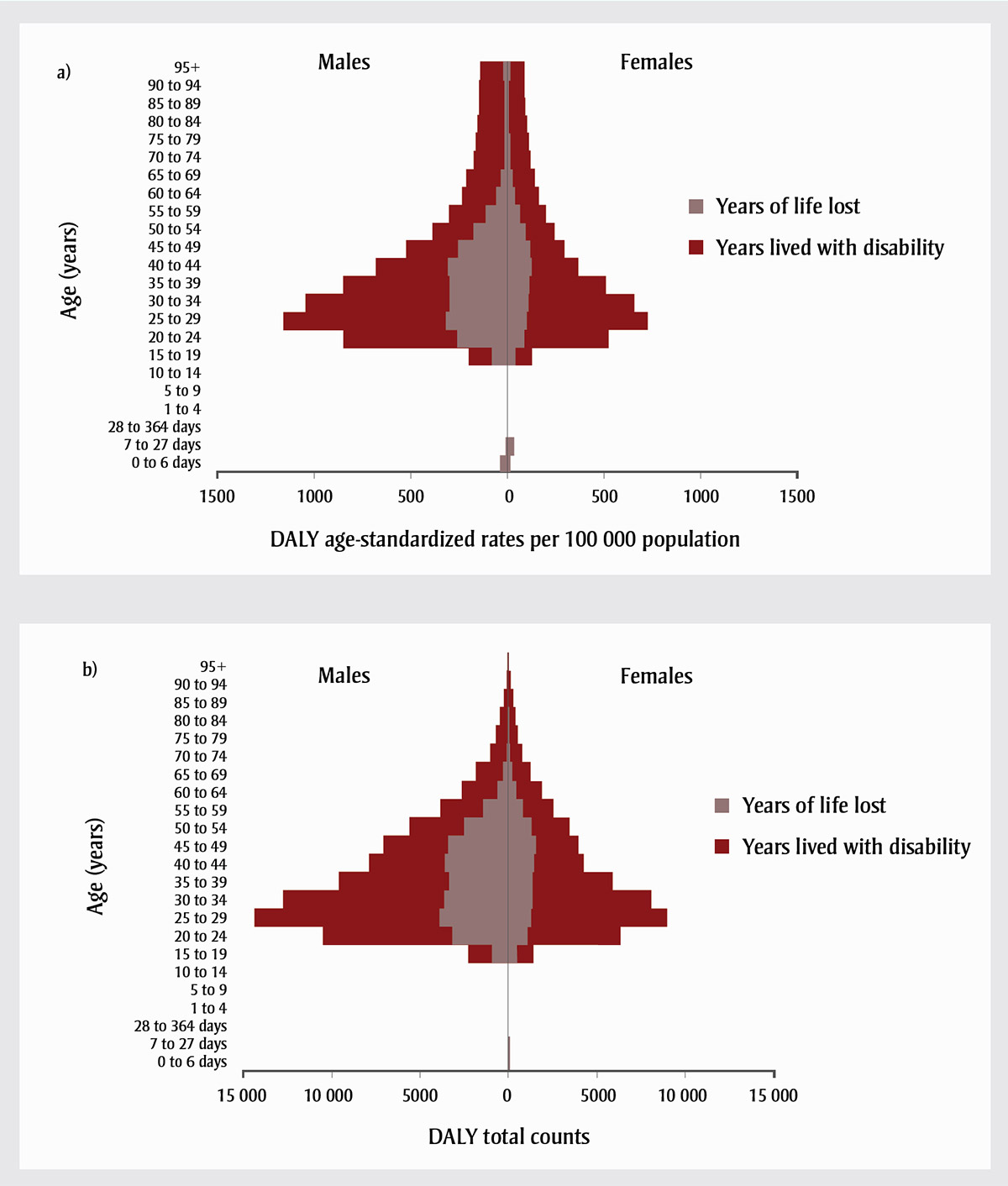

Figure 3 shows the age distribution of DALYs as the sum of YLL and YLD, for males and females, as rates per 100 000 population and counts. The DALY rate among infants is low because of the small number of deaths contributing a relatively higher number of YLL in this age group. This is consistent with vital statistics data for this age group, which show a small and variable number of deaths due to accidental narcotic poisoning each year.Reference 24 The highest number of DALY total counts and highest DALY age-standardized rates are among males in their 20s, whereas those aged 65 years and over contribute a relatively small number of opioid-related DALY overall. YLD contribute the greatest proportion of DALY in all age categories except the neonatal period; however, this proportion varies by age group. There is a relatively higher contribution of YLD to DALY among those aged 70 years and over, compared to younger age groups, and YLD contribute a relatively higher proportion to DALY among younger females, compared to younger men.

Abbreviations: DALY, disability-adjusted life year; YLD, years lived with disability; YLL, years of life lost.

Figure 3 - Text description

Figure 3 shows the age distribution of DALYs as the sum of YLL and YLD, for males and females, as rates per 100 000 (Figure 3a) and counts (Figure 3b). The DALY rate among infants is low because of the small number of deaths contributing a relatively higher number of YLL in this age group. This is consistent with vital statistics data for this age group, which show a small and variable number of deaths due to accidental narcotic poisoning each year. The highest number of DALY total counts and highest DALY age-standardized rates are among males in their 20s, whereas those aged 65 years and over contribute a relatively small number of opioid-related DALY overall. YLD contribute the greatest proportion of DALY in all age categories except the neonatal period; however, this proportion varies by age group. There is a relatively higher contribution of YLD to DALY among those aged 70 years and over, compared to younger age groups, and YLD contribute a relatively higher proportion to DALY among younger females, compared to younger men.

| Age (years) | Males | Females | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YLL | YLD | YLL | YLD | |

| 0 to 6 days | −35.6935362 | 0 | 15.00902923 | 0 |

| 7 to 27 days | −10.74434478 | 0 | 33.71798766 | 0 |

| 28 to 364 days | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 to 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 to 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 to 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 to 19 | −81.62439115 | −118.108076 | 43.7204523 | 83.6531501 |

| 20 to 24 | −258.7364202 | −588.4603408 | 87.47552296 | 434.3096637 |

| 25 to 29 | −317.5719179 | −843.9211927 | 101.3269873 | 626.6724989 |

| 30 to 34 | −299.2156517 | −747.4973507 | 108.4549485 | 550.023642 |

| 35 to 39 | −296.8029834 | −552.5187467 | 116.6601157 | 392.2424149 |

| 40 to 44 | −308.8928903 | −369.3435998 | 124.1958894 | 242.1439262 |

| 45 to 49 | −253.28475 | −271.1966263 | 118.8847152 | 179.7666062 |

| 50 to 54 | −173.6205812 | −215.7087701 | 91.92716966 | 151.347982 |

| 55 to 59 | −111.3289101 | −192.1789953 | 64.63726347 | 134.5500081 |

| 60 to 64 | −56.93214286 | −180.1860456 | 39.08911881 | 125.9259773 |

| 65 to 69 | −35.51347447 | −177.6544654 | 25.27521403 | 116.1412323 |

| 70 to 74 | −15.50828194 | −157.5727853 | 11.75778477 | 106.7560954 |

| 75 to 79 | −15.2036936 | −151.9749058 | 11.47372514 | 97.79128682 |

| 80 to 84 | −12.7149887 | −145.2590212 | 6.970448063 | 92.4313568 |

| 85 to 89 | −12.19520146 | −136.7481143 | 6.937375597 | 86.22384819 |

| 90 to 94 | −15.3308248 | −131.5762409 | 8.508262515 | 81.33070794 |

| 95+ | −19.15856307 | −122.6503053 | 11.44576161 | 76.26994068 |

| Age (years) | Males | Females | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YLL | YLD | YLL | YLD | |

| 0 to 6 days | −1.379705087 | 0 | 0.549473056 | 0 |

| 7 to 27 days | −1.243164743 | 0 | 3.695595973 | 0 |

| 28 to 364 days | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 to 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 to 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 to 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 to 19 | −934.9625644 | −1352.863134 | 473.3710779 | 905.731294 |

| 20 to 24 | −3200.055952 | −7278.08638 | 1059.433974 | 5260.013284 |

| 25 to 29 | −3921.256475 | −10420.41583 | 1246.906135 | 7711.684754 |

| 30 to 34 | −3640.813831 | −9095.442292 | 1333.401164 | 6762.274797 |

| 35 to 39 | −3353.744366 | −6243.22105 | 1342.213222 | 4512.878737 |

| 40 to 44 | −3586.077121 | −4287.876719 | 1446.464156 | 2820.161853 |

| 45 to 49 | −3418.616311 | −3660.375172 | 1576.855548 | 2384.376914 |

| 50 to 54 | −2490.775668 | −3094.576416 | 1299.264079 | 2139.095516 |

| 55 to 59 | −1420.107591 | −2451.428385 | 822.5233784 | 1712.178414 |

| 60 to 64 | −639.06504 | −2022.593858 | 446.1973738 | 1437.429189 |

| 65 to 69 | −303.3058154 | −1517.272903 | 226.1814932 | 1039.318493 |

| 70 to 74 | −91.17344074 | −926.3729576 | 77.26424031 | 701.5291374 |

| 75 to 79 | −65.45307468 | −654.2637021 | 58.57939282 | 499.2758792 |

| 80 to 84 | −40.28927012 | −460.2740971 | 29.58285273 | 392.2822738 |

| 85 to 89 | −20.91253757 | −234.4979774 | 21.07235052 | 261.9058356 |

| 90 to 94 | −8.759013791 | −75.17391421 | 11.85380067 | 113.3107963 |

| 95+ | −2.346864584 | −15.02428218 | 5.091419281 | 33.92716534 |

Discussion

Estimates from the GBD study demonstrate that the health burden associated with opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder in Canada is significant and has increased from 1990 to 2014. The 142% increase in YLLs and 63% increase in DALYs from 1990 to 2014 demonstrate a slowly developing epidemic of opioid-related harms over a quarter of a century.

The Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdose reported 2861 apparent opioid-related deaths in 2016 in Canada.Reference 2 While not directly comparable because of the differences in case definitions, this nevertheless indicates a recent, rapid acceleration of this public health problem. Patterns observed in the USA may foreshadow what is to come for Canada, as the vital statistics data used to model estimates in the USA are current to 2015. Early patterns of opioid-related mortality seen in the USA have been observed in Canada, albeit later.

The burden of opioid-related health loss in Canada disproportionately affects males. The estimated prevalence of opioid use disorder and the DALY rate in males is 1.6 times that in females; their death rate, 2.3 times; their YLD rate, 1.3 times; and their YLL rate, almost 2.5 times. There is a need to understand what drives these sex differences and how interventions can address health inequity. Similarly, opioid-related harms are disproportionately higher among young adults, which could have lasting repercussions throughout the life course. The nature of opioid-related disability and mortality varies according to age group.Reference 32 While deaths in younger age groups likely reflect a higher proportion of non-prescription opioid use, mortality in the older age groups may reflect a significant proportion of opioid toxicity.Reference 33

It is important to note that while the trends from 1990 to 2014 show large increases in opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder, these estimates are almost certainly conservative and underestimate the true burden of opioid use in Canada. When calculating prevalence, used to estimate YLD and DALY, only opioid use disorder is captured. Not all opioid use in the population meets the criteria for opioid use disorder, yet all levels of non-prescription opioid use have the potential to cause harm and disability. Including use that does not meet the criteria for disorder would provide a more comprehensive picture of the true burden of opioid use in Canada. As noted in the methods section of this paper, the 2016 iteration of the GBD calculated estimates using 2012 Canadian vital statistics data. Given that vital statistics data for 2013 and 2014 show an increasing trend in opioid-related mortality, based on public health surveillance, we anticipate that the number of opioid-related deaths will be significantly higher in 2016 and 2017 in Canada.Reference 2 When the GBD process is able to capture this increase, deaths, YLD, YLL and DALY will be higher than the estimates for 2014, which are the focus of this paper.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the rigorous approach to modelling estimates used to quantify health loss associated with opioid use in a manner that is comparable across time, across causes and between countries. This paper provides a more comprehensive account of the health burden associated with opioid-related mortality and disability from opioid use disorder in Canada than previously published results.Reference 3,Reference 6,Reference 34

However, along with this comparability come limitations. The data presented here have been truncated at 2014 in order to align with the date range of the estimates we report from the GBD, as explained in the previous section. The GBD produces estimates through a modelling process that includes standardizing across countries and recoding some causes of death that are known to be unreliable. As such, some GBD estimates may not be fully aligned with the observed data for Canada. Nonetheless, these estimates provide a more robust picture of health loss due to opioid use in Canada, including temporal trends. Comparison of the GBD estimates and observed data from 2000 to 2014 indicate high concordance once categories of deaths are collapsed in a consistent fashion. Deaths due to opioid use disorder, which are relatively rare in Canada (observed deaths between 2000 and 2014 ranged from 1 to 13), were combined with deaths due to accidental poisoning by narcotics and other hallucinogens to create total deaths due to opioid use. This approach may overestimate deaths related to opioid use due to the inclusion of "other hallucinogens" in ICD code X42. However, this is likely to be small because of the low toxicity of hallucinogens.Reference 35 Furthermore, some deaths recorded as accidental poisoning may, in fact, have been intentional poisonings, thus representing deaths by suicide.Reference 36 The full picture of deaths related to opioid use needs to be considered when understanding patterns of opioid-related harms, including those attributed to opioid use disorder and unintentional and intentional poisonings.

Because only disability associated with opioid use disorder was estimated, these analyses do not take into account disability associated with other forms of use, such as acute opioid intoxication or harmful use that does not meet the criteria for disorder. Other studies may include ICD codes not referenced in the present study.Reference 37 The actual burden of disability associated with a broader range of opioid use is likely to be higher than the estimates reported here. Disability weights derived from surveys in a limited number of countries may not be entirely applicable to the Canadian context, and the underlying level of disability for opioid use disorder may vary significantly over time and between contexts.Reference 1

Finally, the GBD method does not account for indirect effects of opioid use and losses that are not health-related. Opioid use may impact negatively on other facets of life, such as relationships, educational attainment and work life, thus having indirect health effects through these social determinants.Reference 38

Further refinement of analyses by characteristics other than sex and age was not possible with the GBD data. Opioid-related health loss is likely not evenly distributed across the Canadian population, and further analyses of inordinately affected subgroups should be conducted. Examples of these subgroups include those who have other mental health problems, low school involvement, a prior history of substance use disorder, chronic homelessness, a history of abuse and neglect and substance use during adolescence.Reference 39 The relationship of medical opioid-prescribing patterns due to patterns of health loss due to opioid use should also be further elucidated. Subnational estimates were not provided, but may be available in future iterations of the GBD study, in a manner similar to those for the USA and the United Kingdom.Reference 40,Reference 41

Conclusion

Health loss due to opioid use is significant and has increased dramatically in Canada from 1990 to 2014. When the GBD study produces estimates with updated vital registration data on opioid-related deaths for 2013 and later, we expect estimates for the period 2014 to 2016 to be even greater than those reported here. Furthermore, they will more accurately reflect the health loss associated with opioid use in Canada. Even then, these estimates will not fully account for the burden of disease associated with opioid use. Canada has a higher level of health loss associated with opioid use than all other high-income countries except for the USA. Well-coordinated public health action to prevent problematic opioid use and related harms is indicated to mitigate the unnecessary death and disability associated with this problem in Canada.

Acknowledgements

This research has been conducted as part of the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD), led by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. The GBD was partially funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; the funders had no role in the study design, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

The authors would like to thank Emily Wolfe Phillips for her thorough review of the final manuscript.

NK is supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' contributions and statement

HMO and JJL conceived the research questions and objectives for this study. HMO and JJL led the synthesis and interpretation of results. HMO, JJL and MB drafted the manuscript. All co-authors contributed to interpreting data and reviewing and revising the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Reference 1

-

Health Canada. Government of Canada actions on opioids: 2016 and 2017. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2017 [Catalogue No.: H14-236/2017E-PDF].

- Reference 2

-

Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. National report: apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada (January 2016 to June 2017) [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2017 [cited 2018 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/apparent-opioid-related-deaths-report-2016-2017-december.html

- Reference 3

-

Klar SA, Brodkin E, Gibson E, et al. Furanyl-fentanyl overdose events caused by smoking contaminated crack cocaine - British Columbia, Canada, July 15-18, 2016. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2016;36(9):200-1. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.36.9.05.

- Reference 4

-

Baldini A, Von Korff M, Lin EH. A review of potential adverse effects of long-term opioid therapy: a practitioner's guide. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(3):PCC.11m01326. doi: 10.4088/PCC.11m01326.

- Reference 5

-

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General. Facing addiction in America: the Surgeon General's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. Washington (DC): HHS; 2016.

- Reference 6

-

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Pan-Canadian trends in the prescribing of opioids, 2012 to 2016. Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2017.

- Reference 7

-

Statistics Canada. CANSIM database: Table 102-0540: Deaths, by cause, Chapter XX: External causes of morbidity and mortality (V01 to Y89), age group and sex, Canada, annual (number), Canada [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; [cited 2018 Jan 1]. Available from: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&id=1020540

- Reference 8

-

Statistics Canada. Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs (CTADS): 2015 summary [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; [updated 2017 Mar; cited 2018 Jan 9]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2015-summary.html

- Reference 9

-

Tourangeau R, Yan T. Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(5):859-83. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.859.

- Reference 10

-

Bonevski B, Randell M, Paul C, et al. Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):42.

- Reference 11

-

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Substance use and suicide: A nexus requiring a public health approach. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. [HHS Publication No. SMA-16-4935].

- Reference 12

-

Gakidou E, Afshin A, Abajobir AA, et al.; GBD 2016 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1345-422. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32366-8.

- Reference 13

-

Wall R, Rehm J, Fischer B, et al. Social costs of untreated opioid dependence. J Urban Health. 2000;77(4):688-722. doi: 10.1007/BF02344032.

- Reference 14

-

GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1151-210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9.

- Reference 15

-

Stevens GA, Alkema L, Black RE, et al. Guidelines for accurate and transparent health estimates reporting: the GATHER statement. PLoS Med. 2016;13(6):e1002056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002056.

- Reference 16

-

Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, et al.; GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet.2017;390(10100):1211-59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2.

- Reference 17

-

Hay SI, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, et al.; GBD 2016 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1260-344. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32130-X.

- Reference 18

-

Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Mathers B, et al. The global epidemiology and burden of opioid dependence: results from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Addiction. 2014;109(8):1320-33. doi: 10.1111/add.12551.

- Reference 19

-

Calabria B, Degenhardt L, Briegleb C, et al. Systematic review of prospective studies investigating "remission" from amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine and opioid dependence. Addict Behav. 2010;35(8):741-49. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.03.019.

- Reference 20

-

Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Calabria B, et al.; GBD illicit drug use writing group. What data are available on the extent of illicit drug use and dependence globally? Results of four systematic reviews. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117(2-3):85-101. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.032.

- Reference 21

-

Nelson P, McLaren J, Degenhardt L, et al. What do we know about the extent of heroin and other opioid use and dependence? Results of a global systematic review. Sydney (AU): National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales; 2010 [NDARCTechnical Report no. 309].

- Reference 22

-

Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Mathers B, et al. Mortality among regular or dependent users of heroin and other opioids: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Addiction. 2011;106(1):32-51. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03140.x.

- Reference 23

-

Foreman KJ, Lozano R, Lopez AD, Murray CJ. Modeling causes of death: an integrated approach using CODEm. Popul Health Metr. 2012;10(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-10-1.

- Reference 24

-

Statistics Canada. CANSIM database: Table 102-0525: Deaths, by cause, Chapter V: Mental and behavioural disorders (F00 to F99), age group and sex, Canada, annual (number), Canada [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; [cited 2018 Jan 1]. Available from: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&id=1020525

- Reference 25

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,4th ed., text revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Reference 26

-

World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders - diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993.

- Reference 27

-

Barendregt JJ, van Oortmarssen GJ, Vos T, Murray CJ. A generic model for the assessment of disease epidemiology: the computational basis of DisMod II. Popul Health Metr. 2003;1(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-1-4.

- Reference 28

-

Hickman M, Taylor C, Chatterjee A, et al. Estimating the prevalence of problematic drug use: a review of methods and their application. Bull Narc. 2002;54:15-32.

- Reference 29

-

Salomon JA, Vos T, Hogan DR, et al. Common values in assessing health outcomes from disease and injury: disability weights measurement study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012; 380(9859):2129-43.

- Reference 30

-

Salomon JA. New disability weights for the global burden of disease. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:879-79.

- Reference 31

-

Grant BF, Moore T, Kaplan K. Source and Accuracy Statement: Wave 1 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Bethesda (MD): National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2003.

- Reference 32

-

Paulozzi LJ, Jones CM, Mack KA, et al. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers - United States, 1999-2008. MMWR. 2011;60(43):1487-92.

- Reference 33

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers and other drugs among women--United States, 1999-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013 Jul 5;62(26):537-42

- Reference 34

-

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Opioid-related harms in Canada. Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2017.

- Reference 35

-

MacLean KA, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Hallucinogens and club drugs. Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment, Fifth Edition. Galanter M, Kleber HD, Brady KT eds. American Psychiatric Association, Arlington, VA. 2015 Apr 1.

- Reference 36

-

Rockett IR, Kapusta ND, Bhandari R. Suicide misclassification in an international context: revisitation and update. Suicidol Online. 2011;2:48-61.

- Reference 37

-

O'Connor S, Grywacheski V, Louie K. At-a-glance - Hospitalizations and emergency department visits due to opioid poisoning in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2018;38(6):244-7.

- Reference 38

-

Degenhardt L, Whiteford H, Hall WD. The Global Burden of Disease projects: what have we learned about illicit drug use and dependence and their contribution to the global burden of disease? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014;33(1):4-12.

- Reference 39

-

Stone AL, Becker LG, Huber AM, et al. Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addict Behav. 2012;37(7):747-75.

- Reference 40

-

Newton JN, Briggs AD, Murray CJ, et al. Changes in health in England, with analysis by English regions and areas of deprivation, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(10010):2257-74.

- Reference 41

-

Coles E, Mensah GA. The burden of heart, lung, and blood diseases in the United States, 1990 to 2016: Perspectives from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Glob Heart. 2017;12(4):349-58.