Original quantitative research – Effects of removing a fee-for-service incentive on specialist chronic disease services: a time-series analysis

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada

Andrew Appleton, MDAuthor reference footnote 1Author reference footnote 2; Melody Lam, MScAuthor reference footnote 2; Britney Le, MScAuthor reference footnote 2; Salimah Shariff, PhDAuthor reference footnote 2; Andrea Gershon, MDAuthor reference footnote 3Author reference footnote 4

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.41.2.04

This article has been peer reviewed.

Correspondence: Andrew Appleton, B9-106 University Hospital, London, ON N6A 5A5; Tel: 519-663-3071; Email: aapplet2@uwo.ca

Abstract

Introduction: Physician payment models are known to affect the nature and volume of services provided. Our objective was to study the effects of removing a financial incentive, the fee-for-service premium, on the provision of chronic disease follow-up services by internal medicine, cardiology, nephrology and gastroenterology specialists.

Methods: We collected linked administrative health care data for the period 1 April 2013 to 31 March 2017 from databases held at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) in Ontario, Canada. We conducted a time-series analysis before and after the removal of the fee-for-service premium on 1 April 2015. The primary outcome was total monthly visits for chronic disease follow-up services. Secondary outcomes were monthly visits for total follow-up services and new patient consultations. We compared internal medicine, cardiology, nephrology and gastroenterology specialists practising during the study timeframe with respirology, hematology, endocrinology, rheumatology and infectious diseases specialists who remained eligible to claim the premium. We chose this comparison group as these are all subspecialties of internal medicine, providing similar services.

Results: The number of chronic disease follow-up visits decreased significantly after removal of the premium, but there was no decrease in total follow-up visits. There was also a significant downward trend in new patient consultations. No changes were observed in the comparison group.

Conclusion: The decrease in volume of chronic disease follow-up visits can be explained by diagnostic criteria being met less often, rather than an actual reduction in services provided. Potential effects on patient outcomes require further exploration.

Keywords: physicians, chronic disease, remuneration, specialization, fee-for-service, economics

Highlights

- Chronic disease patients are mostly looked after by fee-for-service specialists.

- Fee-for-service payment models promote high service volumes.

- Removing a financial incentive for chronic disease follow-up visits led to a decrease in volume of those visits, without affecting total follow-up service volumes.

- Our results suggest that specialists changed their practices, but it remains unclear if this included providing fewer services to patients with chronic disease, increasing higher-paying services or both.

- This work suggests that policy-makers must expect that changes to fee schedules may affect service provision in unanticipated ways.

Introduction

The prevalence of chronic diseases is increasing as our population ages.Footnote 1 Specialist physicians see the patients with the most complex situations, with multiple comorbidities, who cannot be managed solely in primary care. Specialists often provide continuity of care in the form of outpatient office follow-up.

In Canada, specialists are typically paid on a fee-for-service basis; their counterparts in primary care are often remunerated via other payment models, including capitation. Although there is evidence for the effects of payment models on outcomes in primary care, evidence on the extent to which they affect the provision of services by specialists is less abundant. The removal of a premium code, representing a financial incentive for chronic disease follow-up care by specialists in Ontario, Canada, provided an opportunity to study changes in physician practice.

Effective 1 April 2015, the physician specialities of internal medicine, nephrology, gastroenterology and cardiology, practising in Ontario, were no longer eligible to claim a chronic disease premium code listed in the Ontario Health Insurance Program’s (OHIP) Schedule of Benefits.Footnote 2 The code (E078) added a 50% increase in pay on top of follow-up assessment fees, so long as the claim was accompanied by one of 26 eligible diagnostic codes, amounting to an additional $19–$40 per service.Footnote 3 The rationale for removing the E078 code was not made clear, although the timing coincided with a number of changes to payments for physician services and cost-saving measures by Ontario’s Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). Although the code was removed for these higher billing subspecialties of internal medicine, it remained eligible for others, including respirology, endocrinology, rheumatology, hematology and infectious diseases. Other specialties, including oncology and pediatrics, also remained eligible, but for this study we focussed on subspecialties of internal medicine, for their inherently comparable practice style and patient populations.

The removal of the E078 financial incentive for chronic disease follow-up allowed us to study the real-world effect, within the context of a fee-for-service payment model. Our objective was to determine if the volume of chronic disease follow-up visits provided by specialists changed following removal of E078 from the fee schedule. In this time-series analysis, we hypothesized that there would be a reduction in volume of chronic disease follow-up visits by specialists from whom the code was removed, and that there would be no such change in a group of specialists for whom the code remained.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective interrupted time-series analysis of physician services between 1 April 2013 and 31 March 2017, using linked health administrative databases from Ontario. Physician and hospital services in Ontario are covered by a public single-payer insurance program. The fiscal year-end of the insurance program is March 31st. Specialist physicians submit claims to OHIP and are reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis. The reporting of this study follows the guidelines outlined in the RECORD statement for observational studies.Footnote 4

Data sources

We used five linked databases to conduct this study. Datasets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES. We determined physician specialty using the Corporate Provider Database. Physician demographics and service volumes were determined using the ICES Physician Database. For information on physician services, billing claims and their associated diagnostic codes, we used the OHIP Claims database. The Registered Persons Database was used to obtain patient demographics and vital statistics. The Canadian Institute for Health Information’s Discharge Abstract Database was used for comorbidity and hospitalization data. Programming of data extraction was done according to a prespecified dataset creation plan, available on request.

Study population

We assembled a cohort of two groups of specialist physicians who bill fee-for-service. The first group included specialists who were no longer eligible to claim the chronic disease financial incentive, represented by the E078 premium code, after 1 April 2015 (internal medicine, nephrology, gastroenterology and cardiology). We refer to this group as “E078-removed.” The second group remained eligible to claim the premium throughout the study timeframe; their subspecialties included endocrinology, respirology, rheumatology, hematology and infectious diseases. We refer to this group as “E078-remained.” All physicians in the study were eligible to claim internal medicine fee codes; subspecialists (e.g. cardiologists) could also claim fee codes specific to their subspecialty. This is because subspecialists are doubly certified in internal medicine and their subspecialty.

To ensure their eligibility to claim for health services in Ontario, all physicians were required to have an OHIP specialty designation dated prior to 1 April 2013 and ceasing no earlier than 31 March 2017. Moreover, we excluded physicians who billed fewer than 100 annual claims during any year of the study to ensure they were actively practising in Ontario. To confirm that physicians were providing the chronic disease management services of interest, we excluded those who did not claim an E078 premium code during the 2 years prior to its removal.

We gathered data on physician demographics at 1 April 2013, including age, sex, location of medical school graduation, number of years since graduation and rural versus urban practice location. We used the ICES Physician Database to determine the relative full-time-equivalent, percentage of remuneration from fee-for-service claims, total number of visits, emergency department visits, outpatient office visits and hospital visits provided by physicians for fiscal years 2013 and 2015. Using OHIP data, we determined the relative percentage of claims, for each group, made using their internal medicine versus other subspecialty designations.

Because changes in physician service provision could affect the frequency of visits and which patients receive access to care, we created two groups of patients for comparison before and after the removal of E078 premium code. The first group included patients who had an outpatient assessment by at least one of the study physicians between 1 April 2013 and 31 March 2014. The second group met the same criteria but for the timeframe between 1 April 2016 and 31 March 2017. Although the patient groups were not identical, they could include a number of the same individuals. We collected demographic and clinical variables for these patients, including age, sex, regional income quintile, rurality (Statistics Canada definition), Charlson Comorbidity Score, receipt of any E078-eligible chronic disease diagnoses and number of annual consultation or follow-up visits.Footnote 5Footnote 6

Intervention and outcome variables

The intervention in this study was the removal of eligibility to claim the E078 chronic disease premium, effective 1 April 2015, from the E078-removed group of specialists. The primary outcome was the monthly rate of chronic disease follow-up visits, according to E078 premium code eligibility, between 1 April 2013 and 31 March 2017.

Secondary outcomes were monthly visits for the same follow-up services, disregarding E078-specific diagnoses, and monthly visits for new patient consultations. We tracked consultations because specialists could have reallocated their time in favour of these higher-paying services. The same outcomes were determined for the comparator E078-remained group.

Statistical analysis

We compared the baseline characteristics between the E078-removed and E078-remained physicians using T-tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables where a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. For each group of physicians, we compared baseline characteristics of patients seen before and after the intervention using standardized differences. A difference of greater than 10% represented a meaningful imbalance.

We used interventional autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) interrupted time-series models to examine the effect of removing the premium on chronic disease follow-up visits, total follow-up visits and new patient consultations. We fit ARIMA models within both the E078-removed group and the E078-remained group for each outcome, adjusting for serial correlation and seasonality. We evaluated the effect of the intervention by testing for differences in the magnitude and trend of total monthly visits before and after 1 April 2015 for each model.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics approval

The use of data in this project was authorized under section 45 of the province of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, which does not require review by a research ethics board.

Results

After exclusions, we obtained a total cohort of 2560 physicians, with 1826 (71%) in the E078-removed group. The cohort was mostly composed of urban-based, mid- to late-career physicians (Table 1). The E078-removed group was more than 2 years older, on average, and had fewer women than the E078-remained group (22.3% vs. 43.5%).

| Characteristic | E078-removed groupFootnote a n = 1826 |

E078-remained groupFootnote b n = 734 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||

| Age at cohort entry, years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 50.0 (12.0) | 47.9 (10.4) | < 0.01 |

| Median (IQR) | 48 (40–59) | 47 (39–56) | – |

| Female sex, n (%) | 407 (22.3) | 319 (43.5) | < 0.01 |

| Specialty, n (%) | |||

| Internal medicine | 989 (54.2) | – | – |

| Cardiology | 444 (24.3) | – | – |

| Gastroenterology | 237 (13.0) | – | – |

| Nephrology | 156 (8.5) | – | – |

| Respirology | – | 177 (24.1) | – |

| Endocrinology | – | 163 (22.2) | – |

| Rheumatology | – | 157 (21.4) | – |

| Hematology | – | 136 (18.5) | – |

| Infectious diseases | – | 101 (13.8) | – |

| Years since medical school graduation | |||

| Mean (SD) | 24.1 (12.5) | 21.9 (10.9) | < 0.01 |

| Median (IQR) | 22 (14–33) | 20 (13–30) | – |

| Medical degree from outside Canada, n (%) | 397 (21.7) | 107 (14.6) | < 0.01 |

| Rural practice address, n (%) | 11 (0.6) | ≤ 5 | 0.12 |

| Physician payment data, mean (SD) | |||

| Average full-time-equivalentFootnote c | |||

| Fiscal year 2013Footnote d | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.5) | 0.03 |

| Fiscal year 2015Footnote d | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.4) | 0.45 |

| Percent fee-for-service income | |||

| Fiscal year 2013Footnote d | 90.8 (18.7) | 79.3 (29.5) | < 0.01 |

| Fiscal year 2015Footnote d | 88.9 (27.7) | 77.2 (31.2) | < 0.01 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

|

|||

On average, physicians in both groups maintained greater than one full-time-equivalent workload (comparing cohort physicians’ total payments to averages within their subspecialties) before and after the intervention. Fee-for-service income accounted for most of the remuneration of both groups.

The E078-removed group provided significantly fewer total annual visits during the year after the intervention, driven by a decrease in outpatient office visits (Table 2). Conversely, the E078-remained group provided significantly more total annual visits, driven by an increase in outpatient office visits. Comparing fiscal years 2016/17 to 2013/14, the E078-removed group saw 4.3% more patients after the intervention, while the E078-remained group saw 11.4% more patients (Table 3).

| Visits | Physician medical practice data, mean number (SD) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before removal of E078 premium – fiscal year 2013Footnote a | After removal of E078 premium – fiscal year 2015Footnote b | ||

| E078-removed groupFootnote c | |||

| Total patient visitsFootnote d | 3041 (2000) | 2857 (1878) | <0.01 |

| Office visits | 2169 (1850) | 2018 (1741) | 0.01 |

| Emergency department visits | 81 (168) | 83 (172) | 0.78 |

| Hospital visits | 785 (934) | 750 (904) | 0.25 |

| E078-remained groupFootnote e | |||

| Total patient visitsFootnote d | 3155 (2236) | 3400 (2432) | 0.05 |

| Office visits | 2603 (2102) | 2894 (2340) | 0.01 |

| Emergency department visits | 32 (101) | 28 (95) | 0.38 |

| Hospital visits | 516 (711) | 473 (702) | 0.25 |

|

|||

| Characteristic | E078-removed groupFootnote a | E078-remained groupFootnote b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before removal of E078 premium – fiscal year 2013Footnote c n = 994 518 |

After removal of E078 premium – fiscal year 2016Footnote d n = 1 037 302 |

Standardized differencee, % | Before removal of E078 premium – fiscal year 2013Footnote c n = 467 324 |

After removal of E078 premium – fiscal year 2016Footnote d n = 520 554 |

Standardized differenceFootnote e, % | |

| Demographic data | ||||||

| Age, years | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 58.5 (18.3) | 59.8 (17.9) | 7 | 56.5 (17.6) | 57.1 (17.6) | 4 |

| Median (IQR) | 61 (47–72) | 62 (49–73) | – | 58 (45–69) | 59 (46–70) | – |

| Female sex, n (%) | 493 913 (49.7) | 508 753 (49.0) | 1 | 278 768 (59.7) | 308 505 (59.3) | 1 |

| Regional income quintile, n (%) | ||||||

| Quintile 1 | 185 984 (18.7) | 211 862 (20.4) | 4 | 81 827 (17.5) | 101 605 (19.5) | 5 |

| Quintile 2 | 198 903 (20.0) | 216 293 (20.9) | 2 | 89 463 (19.1) | 104 001 (20.0) | 2 |

| Quintile 3 | 198 588 (20.0) | 208 377 (20.1) | 0 | 92 952 (19.9) | 103 881 (20.0) | 0 |

| Quintile 4 | 208 024 (20.9) | 196 232 (18.9) | 5 | 100 968 (21.6) | 101 641 (19.5) | 5 |

| Quintile 5 | 199 423 (20.1) | 202 575 (19.5) | 1 | 100 352 (21.5) | 108 466 (20.8) | 2 |

| Rural residence, n (%) | 87 271 (8.8) | 82 824 (8.0) | 3 | 34 933 (7.5) | 34 479 (6.6) | 3 |

| Charlson Comorbidity ScoreFootnote f, n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 91 840 (9.2) | 93 761 (9.0) | 1 | 41 819 (8.9) | 45 011 (8.6) | 1 |

| 1 | 46 998 (4.7) | 48 395 (4.7) | 0 | 21 489 (4.6) | 23 277 (4.5) | 1 |

| 2+ | 81 059 (8.2) | 86 485 (8.3) | 1 | 37 333 (8.0) | 40 433 (7.8) | 1 |

| No hospitalizations | 774 621 (77.9) | 808 661 (78.0) | 0 | 366 683 (78.5) | 411 833 (79.1) | 2 |

| E078-eligible diagnosis, n (%) | ||||||

| AIDS | 1418 (0.1) | 1592 (0.2) | 0 | 2766 (0.6) | 3312 (0.6) | 1 |

| AIDS-related complex | 617 (0.1) | 627 (0.1) | 0 | 2067 (0.4) | 1933 (0.4) | 1 |

| HIV infection | 1172 (0.1) | 1227 (0.1) | 0 | 3306 (0.7) | 3550 (0.7) | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 221 786 (22.3) | 239 069 (23.0) | 2 | 133 400 (28.5) | 153 875 (29.6) | 2 |

| Coagulation defects | 9586 (1.0) | 8731 (0.8) | 1 | 8009 (1.7) | 8451 (1.6) | 1 |

| Hemorrhagic conditions | 9367 (0.9) | 9585 (0.9) | 0 | 9895 (2.1) | 10 349 (2.0) | 1 |

| Dementia | 29 461 (3.0) | 33 575 (3.2) | 2 | 11 471 (2.5) | 13 509 (2.6) | 1 |

| Parkinson's disease | 6122 (0.6) | 6980 (0.7) | 1 | 2289 (0.5) | 2826 (0.5) | 1 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 2459 (0.2) | 2622 (0.3) | 0 | 1445 (0.3) | 1624 (0.3) | 0 |

| Cerebral palsy | 466 (<0.1) | 461 (<0.1) | 0 | 276 (0.1) | 328 (0.1) | 0 |

| Epilepsy | 9152 (0.9) | 9880 (1.0) | 0 | 4331 (0.9) | 5174 (1.0) | 1 |

| Hypertensive heart disease | 85 887 (8.6) | 47 799 (4.6) | 16 | 15 140 (3.2) | 10 241 (2.0) | 8 |

| Congestive heart failure | 79 332 (8.0) | 80 529 (7.8) | 1 | 21 113 (4.5) | 22 396 (4.3) | 1 |

| Chronic bronchitis | 23 194 (2.3) | 23 855 (2.3) | 0 | 16 650 (3.6) | 19 669 (3.8) | 1 |

| Emphysema | 19 335 (1.9) | 21 157 (2.0) | 1 | 17 073 (3.7) | 20 113 (3.9) | 1 |

| Asthma, allergic bronchitis | 63 141 (6.3) | 58 486 (5.6) | 3 | 44 664 (9.6) | 50 474 (9.7) | 0 |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 6566 (0.7) | 7780 (0.8) | 1 | 7825 (1.7) | 9986 (1.9) | 2 |

| Crohn’s disease | 24 464 (2.5) | 25 088 (2.4) | 0 | 3633 (0.8) | 3987 (0.8) | 0 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 23 793 (2.4) | 24 945 (2.4) | 0 | 3307 (0.7) | 3714 (0.7) | 0 |

| Cirrhosis of the liver | 19 622 (2.0) | 21 074 (2.0) | 0 | 4503 (1.0) | 5325 (1.0) | 1 |

| Chronic renal failure | 88 826 (8.9) | 99 074 (9.6) | 2 | 23 468 (5.0) | 27 573 (5.3) | 1 |

| Lupus, scleroderma, dermatomyositis | 10 115 (1.0) | 11 001 (1.1) | 0 | 19 538 (4.2) | 22 150 (4.3) | 0 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis, Still’s disease | 25 251 (2.5) | 25 935 (2.5) | 0 | 53 790 (11.5) | 57 450 (11.0) | 1 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 3612 (0.4) | 3997 (0.4) | 0 | 8666 (1.9) | 10 381 (2.0) | 1 |

| Seronegative spondyloarthropathies | 5096 (0.5) | 6383 (0.6) | 1 | 14 342 (3.1) | 17 490 (3.4) | 2 |

| Chromosomal anomalies | 2207 (0.2) | 2527 (0.2) | 0 | 2567 (0.5) | 3548 (0.7) | 2 |

| Specialist physician visits | ||||||

| Annual follow-up assessments, n | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.5 (2.6) | 2.6 (2.7) | 4 | 3.0 (3.1) | 3.1 (3.1) | 2 |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | – | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) | – |

| Annual new consultations, n | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.7 (1.1) | 0.8 (1.1) | 3 | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.8 (1.1) | 1 |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | – | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | – |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

|

||||||

There were no substantial differences in patient demographics or frequency of physician visits for either group. The only substantial difference found in patient factors was a reduction in the diagnosis of hypertensive heart disease for patients seen by an E078-removed group physician (8.6% before versus 4.6% after).

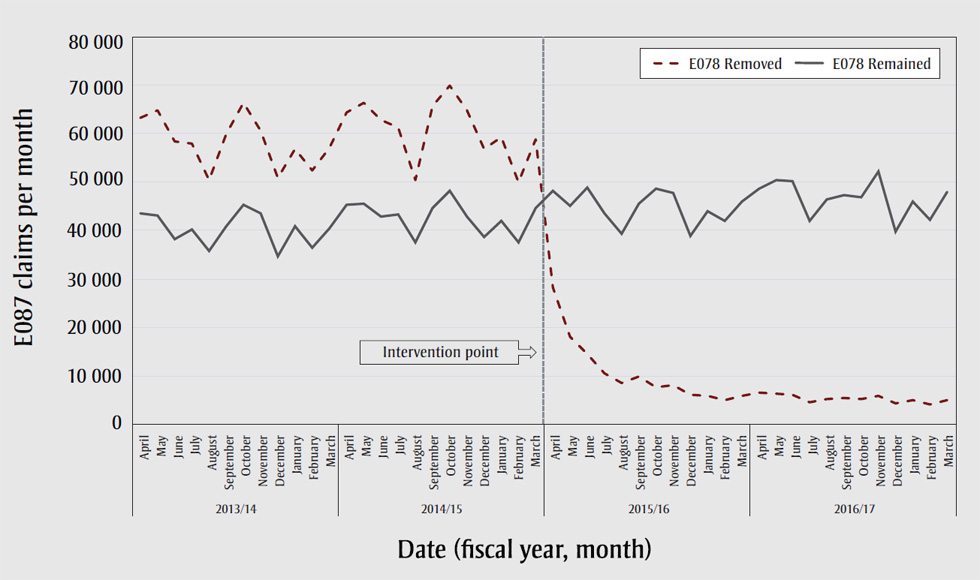

Claims for the E078 premium code, by the E078-removed group, dropped from approximately 60 000 per month to 5 000 per month after the intervention point (Figure 1). Claims by the E078-remained group stayed steady, ranging between 40 000 to 50 000 per month throughout the study timeframe.

Figure 1. Monthly claims of the E078 chronic disease premium by specialist physicians

Text description: Figure 1

| Fiscal year | Month | E087 claims per month | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E078 removed | E078 remained | ||

| 2013/2014 | April | 63303 | 43555 |

| May | 64749 | 43184 | |

| June | 58429 | 38250 | |

| July | 58025 | 40155 | |

| August | 50329 | 35789 | |

| September | 59969 | 40851 | |

| October | 66407 | 45337 | |

| November | 60597 | 43633 | |

| December | 50898 | 34761 | |

| January | 56890 | 40927 | |

| February | 52465 | 36406 | |

| March | 57135 | 40528 | |

| 2014/15 | April | 64385 | 45398 |

| May | 66242 | 45446 | |

| June | 62725 | 42809 | |

| July | 61293 | 43408 | |

| August | 50381 | 37568 | |

| September | 65757 | 44722 | |

| October | 69873 | 48210 | |

| November | 64824 | 42788 | |

| December | 56810 | 38588 | |

| January | 59166 | 42029 | |

| February | 49909 | 37472 | |

| March | 58852 | 44568 | |

| Intervention point | |||

| 2015/16 | April | 28258 | 48266 |

| May | 18035 | 45064 | |

| June | 14468 | 48774 | |

| July | 10566 | 43638 | |

| August | 8548 | 39273 | |

| September | 9829 | 45513 | |

| October | 7619 | 48559 | |

| November | 8013 | 47652 | |

| December | 6090 | 38808 | |

| January | 5836 | 44077 | |

| February | 5046 | 41939 | |

| March | 5833 | 45938 | |

| 2016/17 | April | 6456 | 48718 |

| May | 6302 | 50322 | |

| June | 6419 | 50235 | |

| July | 4543 | 42035 | |

| August | 5334 | 46351 | |

| September | 5530 | 47370 | |

| October | 5228 | 46900 | |

| November | 5875 | 52168 | |

| December | 4455 | 39758 | |

| January | 5063 | 45886 | |

| February | 4217 | 42310 | |

| March | 5055 | 47918 | |

When we plotted visits for follow-up services submitted as internal medicine specialists versus other subspecialty designations, we found no change for the E078-removed group. There was a reduction by more than 90% in visits submitted as internal medicine, following the intervention, by the E078-remained group (data available by request).

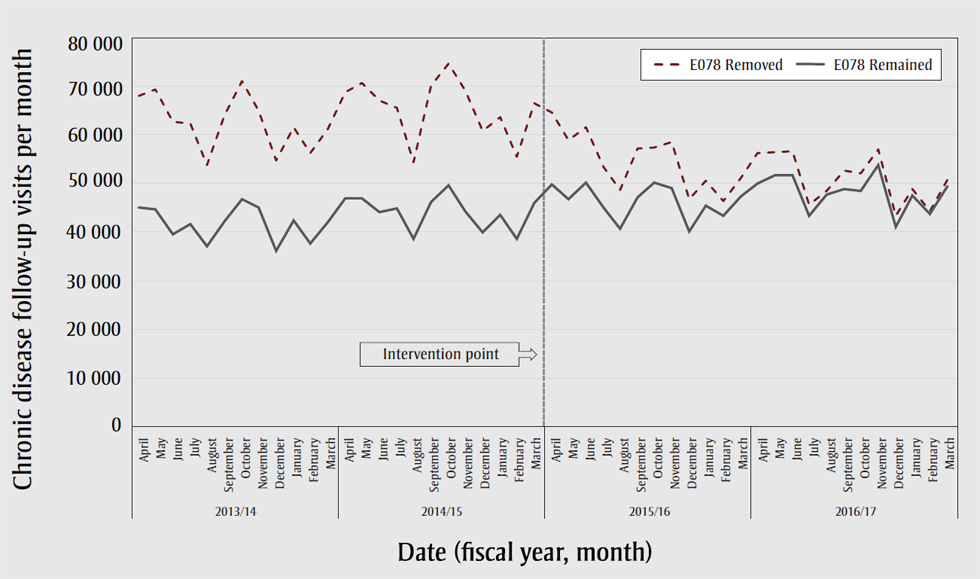

In our time-series analysis, the E078-removed group demonstrated a significant drop in chronic disease follow-up visits for eligible diagnoses immediately following the intervention point, by a factor of 0.86 (p < 0.0001, 95% CI: 0.82–0.90), and in the monthly trend following, by a factor of 0.99 (p < 0.0001, 95% CI: 0.98–0.99). There was no significant change in the E078-remained group at either the intervention point (95% CI: 0.95–1.07) or in the monthly trend following (95% CI: 0.99–1.01) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Monthly chronic disease follow-up visits by specialist physicians

Text description: Figure 2

| Fiscal year | Month | Chronic disease follow-up visits per month | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E078 removed | E078 remained | ||

| 2013/2014 | April | 67945 | 44961 |

| May | 69215 | 44604 | |

| June | 62522 | 39467 | |

| July | 62347 | 41508 | |

| August | 53793 | 36864 | |

| September | 64014 | 42080 | |

| October | 70968 | 46628 | |

| November | 64890 | 45001 | |

| December | 54727 | 35978 | |

| January | 61473 | 42276 | |

| February | 56237 | 37515 | |

| March | 61126 | 41814 | |

| 2014/15 | April | 68738 | 46794 |

| May | 70720 | 46754 | |

| June | 67115 | 44058 | |

| July | 65589 | 44748 | |

| August | 54362 | 38530 | |

| September | 70024 | 46105 | |

| October | 74644 | 49551 | |

| November | 69193 | 44222 | |

| December | 60816 | 39821 | |

| January | 63511 | 43453 | |

| February | 55407 | 38553 | |

| March | 66450 | 45938 | |

| Intervention point | |||

| 2015/16 | April | 64628 | 49767 |

| May | 58931 | 46571 | |

| June | 61593 | 50009 | |

| July | 53293 | 45032 | |

| August | 48554 | 40496 | |

| September | 57165 | 47023 | |

| October | 57281 | 50040 | |

| November | 58478 | 49037 | |

| December | 46597 | 39965 | |

| January | 50517 | 45263 | |

| February | 46351 | 43159 | |

| March | 50946 | 47190 | |

| 2016/17 | April | 56114 | 49904 |

| May | 56359 | 51683 | |

| June | 56514 | 51537 | |

| July | 45588 | 43248 | |

| August | 47537 | 47537 | |

| September | 52517 | 48723 | |

| October | 51901 | 48350 | |

| November | 57024 | 53718 | |

| December | 43314 | 40999 | |

| January | 48763 | 47369 | |

| February | 44133 | 43630 | |

| March | 50583 | 49331 | |

Note: E078-eligibility criteria include an assessment fee code plus one of 26 eligible chronic disease diagnoses.

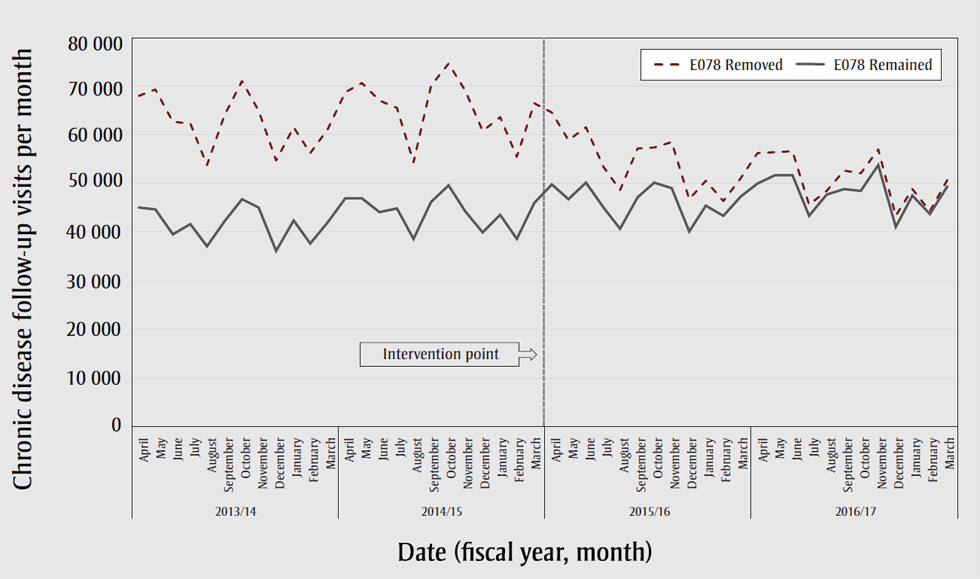

Time-series analyses of secondary outcomes did not demonstrate significant changes in total follow-up visits, which disregard the diagnostic criteria for the E078 premium (Figure 3). Although there was no change in new patient consultations at the intervention point, there was a significant decrease in the monthly trend following the intervention, by a factor of 0.99 (p < 0.05, 95% CI: 0.99–1.00), in the E078-removed group.

Figure 3. Monthly visits for total follow-up services and consultations by specialist physicians, which need not meet criteria for E078-eligibility

Text description: Figure 3

| Fiscal year | Month | Visits per month | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E078 removed follow-ups | E078 remained follow-ups |

E078 removed consultations |

E078 remained consultations |

||

| 2013/2014 | April | 183843 | 88980 | 94599 | 28660 |

| May | 189206 | 89698 | 94517 | 28014 | |

| June | 169832 | 80327 | 87980 | 25017 | |

| July | 170329 | 83576 | 89543 | 27516 | |

| August | 147767 | 74779 | 78752 | 24811 | |

| September | 172411 | 84752 | 87344 | 27013 | |

| October | 189732 | 92163 | 97035 | 28639 | |

| November | 177250 | 89008 | 91435 | 28006 | |

| December | 147871 | 72377 | 76098 | 22119 | |

| January | 168484 | 84504 | 91958 | 28266 | |

| February | 152257 | 75365 | 82841 | 24839 | |

| March | 166328 | 83255 | 88785 | 26690 | |

| 2014/15 | April | 184242 | 91873 | 94013 | 27992 |

| May | 186623 | 92514 | 95463 | 27849 | |

| June | 179534 | 87183 | 91318 | 26524 | |

| July | 173844 | 89976 | 91445 | 29002 | |

| August | 145353 | 75751 | 77573 | 23369 | |

| September | 184841 | 92026 | 94893 | 27735 | |

| October | 194195 | 96787 | 96054 | 28965 | |

| November | 181317 | 87768 | 89955 | 26033 | |

| December | 163234 | 79295 | 82477 | 23584 | |

| January | 173728 | 86654 | 93993 | 27629 | |

| February | 151792 | 76460 | 84377 | 24881 | |

| March | 179593 | 89567 | 93273 | 27924 | |

| Intervention point | |||||

| 2015/16 | April | 188864 | 96575 | 97058 | 28097 |

| May | 181198 | 91607 | 92485 | 26543 | |

| June | 193711 | 97798 | 98180 | 28752 | |

| July | 170851 | 88932 | 90129 | 27669 | |

| August | 157355 | 79486 | 82920 | 24283 | |

| September | 182848 | 92572 | 92476 | 26358 | |

| October | 185427 | 96877 | 90506 | 27144 | |

| November | 188886 | 96225 | 93544 | 26982 | |

| December | 158657 | 79349 | 80761 | 22853 | |

| January | 171873 | 88817 | 93745 | 27810 | |

| February | 160192 | 83419 | 89752 | 26828 | |

| March | 175663 | 91173 | 93881 | 27536 | |

| 2016/17 | April | 185410 | 95775 | 95187 | 27033 |

| May | 190277 | 99676 | 96777 | 28018 | |

| June | 191200 | 99375 | 98304 | 28360 | |

| July | 156872 | 82281 | 82162 | 24522 | |

| August | 165288 | 90424 | 86581 | 27051 | |

| September | 177942 | 94253 | 90426 | 26368 | |

| October | 177564 | 92773 | 88055 | 25199 | |

| November | 195824 | 102958 | 96526 | 28674 | |

| December | 154328 | 79304 | 77280 | 22537 | |

| January | 174376 | 90801 | 93491 | 27315 | |

| February | 155353 | 82672 | 85800 | 25173 | |

| March | 175819 | 94461 | 93734 | 27671 | |

Discussion

In this time-series analysis, we identified a reduction in the monthly volume of chronic disease follow-up visits provided by internal medicine, nephrology, gastroenterology and cardiology specialists following removal of the E078 chronic disease premium from the OHIP Schedule of Benefits. In comparison, there was no significant change in chronic disease follow-up visits by respirology, endocrinology, rheumatology, hematology and infectious disease specialists, who remained eligible to claim the premium.

We analyzed two secondary outcomes: total follow-up visits (not limited to E078-eligible diagnoses) and new patient consultations. The only significant change was a downward trend in new patient consultations provided by the E078-removed group, confirming that the provision of services did not skew in favour of consultations, which pay 2 to 4 times more than follow-ups. Since chronic disease follow-up visits are a subset of total follow-up visits, and the rate of the latter did not change, we concluded that the formerly E078-eligible diagnostic codes were being applied less often by the E078-removed group following the intervention. This is understandable, from the standpoint of economic behaviour, as a financial incentive for the E078-removed group to designate certain diagnoses over others no longer existed. This is supported by our baseline data for patients seen by an E078-removed group physician, revealing that patients were less likely to have been assigned a diagnostic code for hypertensive heart disease after the intervention. Patients seen by specialists often have more than one chronic disease. Therefore, more than one diagnostic code may apply. However, our findings cannot resolve whether specialists were assigning diagnostic codes that accurately reflected the condition for which the patient sought care, versus a stable comorbidity that would have met criteria for the E078 premium.

The reduction in use of internal medicine versus other subspecialty-specific billing codes by the E078-remained group may also be explained by economic behaviour. For example, after E078 was removed, an endocrinologist would not receive the premium when claiming internal medicine service codes, but would receive the premium when claiming endocrinology codes. Even though the endocrinologist could claim either set of codes, the rational option would be to use their subspecialty-specific ones, remaining eligible for premium payment.

Removal of the E078 premium represented a one-third reduction in remuneration for eligible services. In response to this, a physician could either increase the volume of these same services to make up for losses or shift their allocation of services to higher-paying tasks. We now know that the E078-removed group did not significantly increase their volume of follow-up services, nor did they shift to provide more consultations. In fact, they experienced a downward trend in providing new patient consultations, which aligns with our baseline data revealing a significant reduction in average total office visits provided in the year following loss of the premium. Given that physicians in the study were already working at greater than one full-time-equivalent, it is unlikely they would have had capacity to increase service volume. It may be possible that the decrease in office visits indicates a shift in allocation to other tasks, but we are unable to tell, from data collected for this study, if this actually occurred.

This study focussed on the effects of removing a fee-for-service payment incentive, which is representative of the predominate model for remuneration of specialists in Canada. It is generally known that fee-for-service payments can lead to the overprovision of low-value or unnecessary care, hence the push for salary-based or capitation payment models in primary care.Footnote 7Footnote 8 Moreover, prior studies on two models of salary-based funding for specialists, in Canadian academic centres, indicate better care for complex patients.Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11

This stands in contrast with more robust data, from primary care, showing that fee-for-service payment models may incent complex chronic disease management more than capitation models, where a set amount is provided per enrolled patient.Footnote 12Footnote 13Footnote 14 In addition, no strong evidence exists demonstrating that non-fee-for-service payment models for specialists would reduce costs; nor does the present study address this point. Exploring the effects of different payment models for specialists, on chronic disease management, requires more attention.

Strengths

Given that physician services in Ontario are insured publicly, the data are valid and representative of the groups of specialists who were studied. Further, the findings from this report are generalizable to other jurisdictions in Canada, who also remunerate physicians via public insurance programs. On an international scale, specialists are also often paid fee-for-service, making the results from our study of wide interest.

In terms of methodology, because the intervention was at a single time point and affected the entire cohort, using time-series analysis is a sensitive statistical technique to detect a quantitative change in the outcome.

Limitations

Our study focussed on changes in the volume of services provided by the E078-removed group. Although we compared outcomes with the E078-remained group, this was not a controlled experiment, so differences cannot be attributed solely to removal of the premium. The baseline characteristics of these two physician groups were substantially different, notably for type of specialty and proportion of women. These, among other unmeasured factors, could have influenced the outcomes of the study.

A number of changes were made to payments for physician services along with the premium removal.Footnote 2 Although global reductions in fee-for-service and non-fee-for-service payments applied to all physicians, there were other changes for specific service fees, which may have affected some specialties more than others. We did not quantify the potential effects of these changes to remuneration.

Our results can only be applied in relation to changes in economic incentives for physicians. Our study did not evaluate effects on patients’ health outcomes. The patient data collected only indicated that there was an increase in the total number of individuals seen by both groups and that their basic demographics were similar before and after the fee schedule change.

Conclusion

Removal of the E078 chronic disease premium from the OHIP Schedule of Benefits was followed by a significant decrease in the provision chronic disease follow-up visits. This was driven by changes in the use of diagnostic codes, rather than total follow-up service volumes. However, affected specialists experienced a downward trend in new patient consultations, and provided fewer total office visits, on average, in the year following removal of the premium, suggesting a shift in service allocation. These outcomes underscore that policy-makers need to consider the effect on economic behaviour when planning to alter payment incentives for specialists, as this may have downstream effects on patient outcomes. Future work should focus on quantifying the possible changes in health outcomes for patients whose specialist physicians were included in the group no longer able to claim the chronic disease premium.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the ICES Western site. ICES is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). Core funding for ICES Western is provided by the Academic Medical Organization of Southwestern Ontario (AMOSO), the Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry (SSMD), Western University and the Lawson Health Research Institute (LHRI).

The opinions, results and conclusions are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES, AMOSO, SSMD, LHRI, Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) or the MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by CIHI. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed in the material are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of CIHI.

Conflict of interest

None.

Authors’ contributions and statement

AA: conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft; ML: methodology, data curation, writing – review and editing; BA: methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing – review and editing; SS: conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing; AG: conceptualization, supervision, writing – review and editing.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.