Commentary – Nimble, efficient and evolving: the rapid response of the National Collaborating Centres to COVID-19 in Canada

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada

Tell us what you think

Help us improve our products, answer our quick survey.

Maureen Dobbins, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1; Alejandra Dubois, PhDAuthor reference footnote 2; Donna Atkinson, MAAuthor reference footnote 3; Olivier Bellefleur, MScAuthor reference footnote 4; Claire Betker, PhDAuthor reference footnote 5; Margaret Haworth-Brockman, MScAuthor reference footnote 6; Lydia Ma, PhDAuthor reference footnote 7

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.41.5.03

(Published February 17, 2021)

Correspondence: Alejandra Dubois, Public Health Agency of Canada, 130 Colonnade (6501H) Ottawa, ON K1A 0K9; Tel: 343-549-1247; Email: alejandra.dubois@canada.ca

Abstract

Since December 2019, there has been a global explosion of research on COVID-19. In Canada, the six National Collaborating Centres (NCCs) for Public Health form one of the central pillars supporting evidence-informed decision making by gathering, synthesizing and translating emerging findings. Funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada and located across Canada, the six NCCs promote and support the use of scientific research and other knowledges to strengthen public health practice, programs and policies. This paper offers an overview of the NCCs as an example of public health knowledge mobilization in Canada and showcases the NCCs’ contribution to the COVID-19 response while reflecting on the numerous challenges encountered.

Keywords: knowledge mobilization, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, knowledge networks, public health practice, evidence-based practice, organizational decision making, emerging infectious diseases

Highlights

- The explosion of research on COVID-19 in Canada and around the world called for an improved capacity to support evidence-informed decision making (EIDM).

- Canada is fostering various mechanisms to achieve this goal; the National Collaborating Centres (NCCs) for Public Health are central to supporting EIDM during the pandemic.

- The NCCs, a network of networks anchored on six unique knowledge hubs, are well connected to provincial, territorial, local and international partners.

- In response to COVID-19, the NCCs are making an important contribution to building knowledge, skills and capacity in the public health sector, and to supporting public health professionals in synthesizing and using evidence-informed knowledge in policy and practice.

Introduction

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in late 2019 resulted in a pandemic that precipitated, among other things, an unprecedented explosion of research and a deluge of information in popular science journalism and the mainstream press. The continual evolution of knowledge and information related to the virus significantly hampered the ability of policy makers and other decision makers to utilize the best available evidence. Furthermore, the task of gathering, synthesizing and translating emerging science-informed evidence relating to COVID-19 became particularly challenging. The exponential growth of data and other information made it increasingly difficult to quickly locate evidence of sufficient trustworthiness to inform policy and practice decisions. In the midst of this challenging reality, opportunities arose for a collaborative approach to knowledge mobilization that takes into account the respective knowledge, skills, expertise, capacity and networks of the National Collaborating Centres (NCCs) for Public Health in Canada.

While many organizations have contributed significantly to the public health response to COVID-19, this article will focus specifically on the six National Collaborating Centres for Public Health. The NCCs were established in 2005Footnote 1 following the first SARS outbreak in Canada with a key purpose of quickly and efficiently mobilizing rigorous knowledge to public health decision makers in Canada in the event of a national or global crisis.Footnote 2

The purpose of this article is to summarize what the NCCs have done to support the public health response to COVID-19 in Canada, to explore challenges related to rapid knowledge mobilization and to review lessons learned throughout this experience. This article also aims to describe how the vast networks of the NCCs and their ability to develop new partnerships during the pandemic have supported public health professionals throughout Canada in a way that could not have been achieved by any one organization alone.

The National Collaborating Centres for Public Health

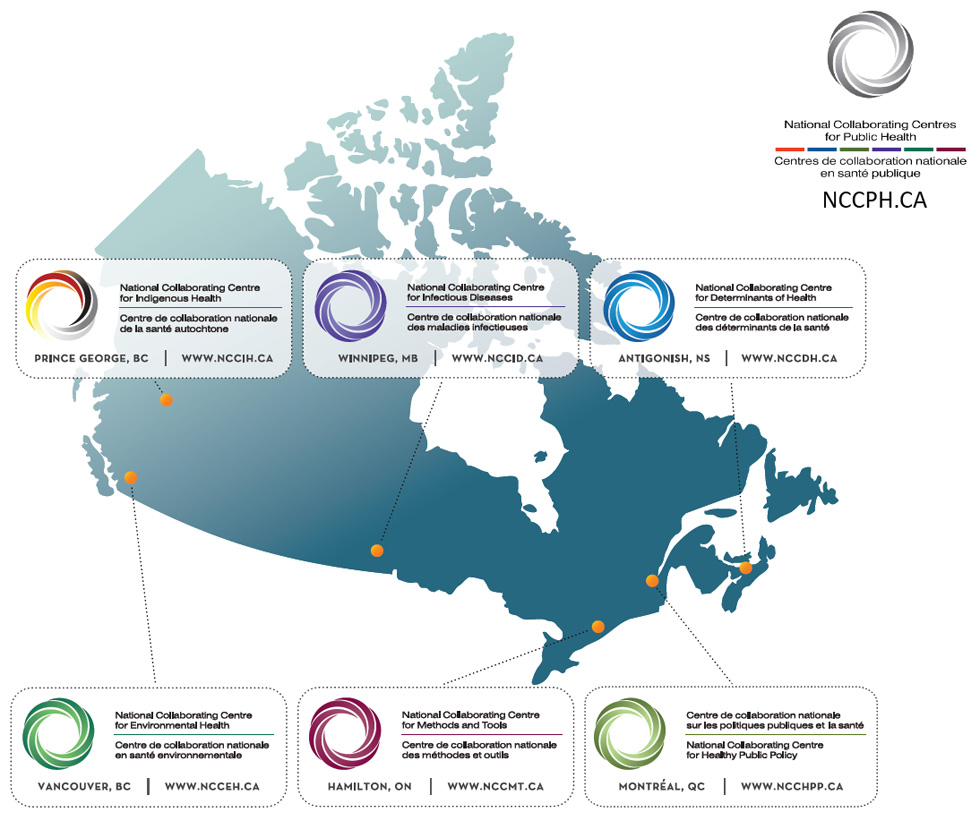

The NCCs are funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and are geographically located across the country (Figure 1). They were designed to promote and support the use of scientific research and other knowledges to strengthen public health practice, programs and policies in Canada within specific public health domains: Determinants of Health, Environmental Health, Healthy Public Policy, Indigenous Health, Infectious Diseases, and Methods and Tools (Table 1).

Note: This figure depicts a map of Canada, indicating the location, name and unique logo of each of the six National Collaborating Centres (NCCs). It also includes the logo of the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health, which encompasses the six specific NCCs.

Figure 1 - Text description

This figure depicts a map of Canada, indicating the location, name and unique logo of each of the six National Collaborating Centres (NCCs). It also includes the logo of the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health along with its website, NCCPH.CA, which encompass the six specific NCCs.

From left to right:

National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health in Vancouver, British Columbia. (www.ncceh.ca)

National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health in Prince George, British Columbia. (www.nccih.ca)

National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases in Winnipeg, Manitoba. (www.nccid.ca)

National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools in Hamilton, Ontario. (www.nccmt.ca)

National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy in Montréal, Quebec. (www.ncchpp.ca)

National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health in Antigonish, Nova Scotia. (www.nccdh.ca)

| NCC name | Acronym | Host organization | Location | Main focus/priorities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Determinants of Health | NCCDH | St. Francis Xavier University | Antigonish, Nova Scotia |

|

| Environmental Health | NCCEH | British Columbia Centre for Disease Control | Vancouver, British Columbia |

|

| Infectious Diseases | NCCID | University of Manitoba | Winnipeg, Manitoba |

|

| Methods and Tools | NCCMT | McMaster University | Hamilton, Ontario |

|

| Indigenous Health | NCCIH | University of Northern British Columbia | Prince George, British Columbia |

|

| Healthy Public Policy | NCCHPP | Institut national de santé publique du Québec | Montréal, Quebec |

|

Abbreviation: NCC, National Collaborating Centre. |

||||

The NCCs carry out their mission by fostering collaboration and networking among diverse stakeholders and drawing on regional, national and international expertise to build knowledge, skills and capacity at the individual, organizational and system levels. NCCs turn research and other information and evidence into knowledge products tailored to specific audiences, contextualized to their settings and available in both official languages. They work with a wide range of partners and organizations across jurisdictions to create opportunities to share knowledge and learn from one another.Footnote 3

The NCCs’ contribution to Canada’s response to COVID-19

Although each NCC is unique and has its own focus, distinctive characteristics and expertise, their flexibility and responsiveness to emerging issues are their common denominator. This joint attribute makes the NCCs ideally suited to support the system response. Indeed, from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, each NCC reoriented its priorities to support the evidence needs of public health professionals and address gaps as they emerged.

Some of the key resources produced by the NCCs include curated online lists or repositories of COVID-19 evidence pertaining to topics specific to the focus of each NCC;Footnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 7Footnote 8 evidence syntheses on priority questions identified by public health decision makers and public health practitioners;Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11Footnote 12Footnote 13 a backgrounder on SARS-CoV-2 that provides an introduction to the basic virology and transmission of SARS-CoV-2; to inform the measures taken to mitigate the spread of the virus;Footnote 14 new webpages that identify topic-specific websites with trustworthy information on COVID-19;Footnote 15 mathematical modelling resources;Footnote 16 and fact sheets.Footnote 17 Key activities the NCCs engage in to support knowledge mobilization of COVID-19 evidence and resources include webinars,Footnote 18Footnote 19 blog posts,Footnote 20 guidance documents,Footnote 21 podcasts,Footnote 22Footnote 23 and social media.

The NCCs contributed to multiple research proposals for COVID-19 funding competitions and partnered with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to support research teams in the dissemination and uptake of findings from COVID-19 proposals funded in 2020. The NCCs also fostered various networks (e.g. COVID-19 and Health Equity Network,Footnote 24 Global Network for Health in All Policies), supported communities of practice,Footnote 25 and have been working to facilitate the integration of well-being indicators in government budgeting and policy decisions related to the recovery phase of the pandemic.Footnote 26

While each NCC operates as an autonomous and independent entity, throughout the pandemic the NCCs have met regularly to explore opportunities to work together on many of the initiatives described above. A continuing intention is to avoid duplication, and to share efforts to address local, regional, provincial/territorial and national public health needs. Several resources have been developed by two or more NCCs together, and many initiatives to disseminate evidence on COVID-19 have been conducted by several NCCs in partnership.

Challenges encountered

Because the coronavirus that caused the global pandemic was a novel pathogen, its features and the disease transmission mechanisms only began to be understood in early 2020, and our understanding has continued to evolve over time. Particularly during the first six months of the pandemic, new evidence emerged almost on a daily basis, making evidence syntheses out of date before they were even released. Pre-prints, which are articles submitted to journals that are released ahead of peer review, became the norm and many were released with little to no detail about their research methods, drawing into question the trustworthiness of the findings. Because the pathogen was novel, the evidence needs of policy and decision makers and the speed at which those needs had to be addressed were far greater than the capacity of those trying to address them.

Challenges were also experienced in deciding which questions to address first and understanding whose needs should be given the greatest priority. For example, there was a lack of peer-reviewed COVID-19 information relating to Indigenous health available to synthesize, particularly research written by Indigenous scholars. In addition, there were challenges in ensuring First Nations, Inuit and Métis community perspectives and experiences informed policies and decision-making. The depth of existing inequities experienced by Indigenous peoples increased their risk and required that information be contextualized in order that the unique vulnerabilities and determinants of First Nations, Inuit and Métis health could be understood and appropriate responses made.

At the same time, keeping a proportionate focus on the needs of public health personnel and populations at greater disadvantage (due to local availability of health care resources or ongoing stigma and discrimination) was also necessary in order to avoid perpetuating further health inequities and inequalities. Furthermore, the arrival of COVID-19 did not—with the apparent exception of seasonal influenzaFootnote 27—diminish the need to provide timely evidence and knowledge about other pervasive infectious diseases (e.g. sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections, tuberculosis and antimicrobial resistanceFootnote 28Footnote 29) and other public health programs and services.

In addition, while there was an urgent need to quickly distribute knowledge products to policy makers and decision makers, they were also overwhelmed with too much information and misinformation. The term “infodemic” re-emerged to define this particular context.Footnote 30 It was not immediately clear how best to disseminate knowledge products, and to whom. There was also substantial duplication of evidence syntheses occurring (internationally, nationally, provincially, regionally and locally) as well as duplication in the development of French and English resources. It was impossible to stay aware of what everyone was doing and producing all of the time.

Many have described the pace at which organizations functioned during the first six months of the pandemic as that of a “sprint.” It became impossible to maintain this pace; staff became fatigued and experienced signs of burnout. In addition, this effort occurred while learning how to function virtually. There was much to learn about working efficiently and effectively from home as a team, including ensuring that staff had the necessary equipment to work virtually.

Lessons learned and emerging strategies

In the early months of the pandemic (March and April 2020) reviewing research, recommendations and lessons learned from the SARS and H1N1 epidemics was time well spent to capitalize on dos and don’ts from past strategies. In the same way, reflection on the first several months of the current pandemic gives rise to several lessons learned that the NCCs will use to guide efforts to support the current and medium- and long-term responses to COVID-19 as well as those of the recovery phase.

First, there is a need for forward thinking in order to anticipate the next steps in the pandemic response and future knowledge needs of policy makers and decision makers. A proactive rather than reactive approach will facilitate the availability of evidence syntheses and knowledge products, as well as engagement and collaboration, when policies and decisions are being made. It is important to create resources that not only meet current needs related to COVID-19 but have usability beyond the pandemic.

Second, public health actors have been heavily mobilized to contain the spread of the virus and to mitigate its immediate impacts on all sectors of society since the start of the pandemic, but they have also been solicited to contribute to policies, programs and practices to support recovery to a healthier and more equitable, resilient and sustainable society. However, containing the virus and dealing with its immediate impacts has not left much time or energy for public health organizations to contribute to this second role, which is more focussed on the medium- to long-term response. As a network of networks, some NCCs were well placed to contribute to the surge capacity needed to support public health actors in their immediate response, while others were able to mobilize to support them in their contribution to the medium- and long-term response.

Third, established relationships and partnerships are essential. Being able to tap into the public health field has been critical to the work of the NCCs, as has the ability to draw on Indigenous knowledges and experiences of past pandemics (e.g. H1N1, smallpox). Regular check-ins with other NCCs and PHAC have been instrumental in coordinating work, fostering collaboration and avoiding duplication of effort. Dedicated staff with established relations of trust who can work across jurisdictions are needed to proactively seek out who is working on what, compile the information and share it.

Leveraging networks and developing new partners

A comprehensive response to COVID-19 requires engagement, collaboration and partnership across disciplines, sectors and jurisdictions. Building on well-established relationships with many partners and colleagues such as public health professionals, governmental departments, evidence synthesis organizations, researchers and post-secondary educational institutions, the NCCs have contributed to connecting researchers, policy makers and practitioners to support knowledge sharing and evidence-informed policies, decisions, practice and emerging research.

The NCCs have been active participants and leaders in national and international collaborations that have emerged as a result of the pandemic. One such initiative is the COVID-19 Evidence Network to support Decision-making (COVID-END).Footnote 31 This international network is helping those supporting decision making to find and use the best evidence on COVID-19, facilitating coordination of evidence syntheses efforts worldwide,Footnote 32 and reducing duplication of effort. Through participation in COVID-END, the NCCs are contributing to the evidence ecosystem and avoiding duplication of evidence syntheses.

Conclusion

Evidence-informed public health is rooted in the seminal work of Archie Cochrane, who since the early 1970s noted that many medical treatments lacked scientific evidence of effectiveness.Footnote 33 Over the years, Canada and many other countries have developed evidence-informed capacity to improve the use of scientific evidence in day-to-day public health practice, policy and decisions. With each pandemic (SARS, H1N1, COVID-19) there has been a growing commitment both nationally and internationally to an evidence-informed response. In fact, it was the SARS epidemic of 2003 that triggered the creation of the Public Health Agency of Canada, the pan-Canadian Public Health Network and the NCCs as structural pillars of the Canadian public health system.

In the 16 years since their creation, the NCCs have demonstrated a proven track record of working with the other pillars, supporting and responding to the needs of public health with evidence, knowledge systems and network building. Today, we are witnessing the benefits of the investment in the NCCs as they fill a critical role in the public health system in Canada during this pandemic by identifying gaps, compiling and synthesizing evidence and facilitating knowledge mobilization and exchange so as to bridge the divide between evidence, policy and practice.

Acknowledgements

The National Collaborating Centres receive funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada. Many thanks to key members of each of the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health for reviewing earlier drafts of this article and for providing input (in alphabetical order: Emily Clark, Margo Greenwood, Heather Husson, Michael Keeling, Yoav Keynan, Tom Kosatsky, Sarah Neil-Sztramko). Our thanks to Dr. Patricia Huston for her advice and contribution to the preliminary draft of the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions and statement

AD was responsible for conceptualization, methodology and project administration, and writing, reviewing and editing the original draft. MD significantly revised the original draft and added several new sections based on feedback received from reviewers. All other listed authors were responsible for validation of the research design, and review and editing of both drafts of the paper. All authors helped critically revise the article throughout the development and peer review process.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

Conflicts of interest

None.