Joint Evaluation of the Implementation of the Veterans Hiring Act

Table of Contents

- 1.0 Purpose

- 2.0 Background

- 3.0 Objective, scope and methodology

- 4.0 Evaluation findings

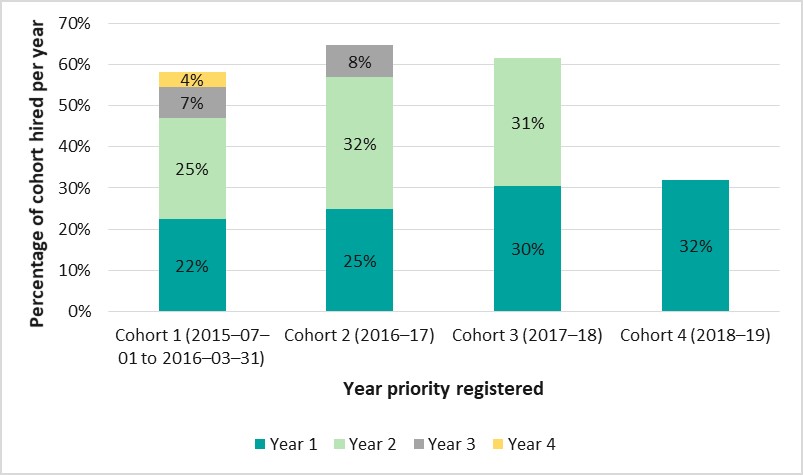

- 4.1 Veterans Hiring Act implementation

- 4.2 Awareness of the Veterans Hiring Act provisions

-

4.3 Hiring veterans through the provisions established in the Veterans Hiring Act

- 4.4 To what extent are veterans appointed to the federal public service applying their skills and making meaningful contributions to the work environment?

- 4.5 To what extent are there alternative ways or lessons learned that might be applied to achieve the same results?

- 4.6 Veterans Hiring Act implementation alignment with government roles and responsibilities

- 4.7 Continuing need for implementing the Veterans Hiring Act provisions

- 5.0 Conclusion

- 6.0 Recommendations

- 7.0 Management response and action plan

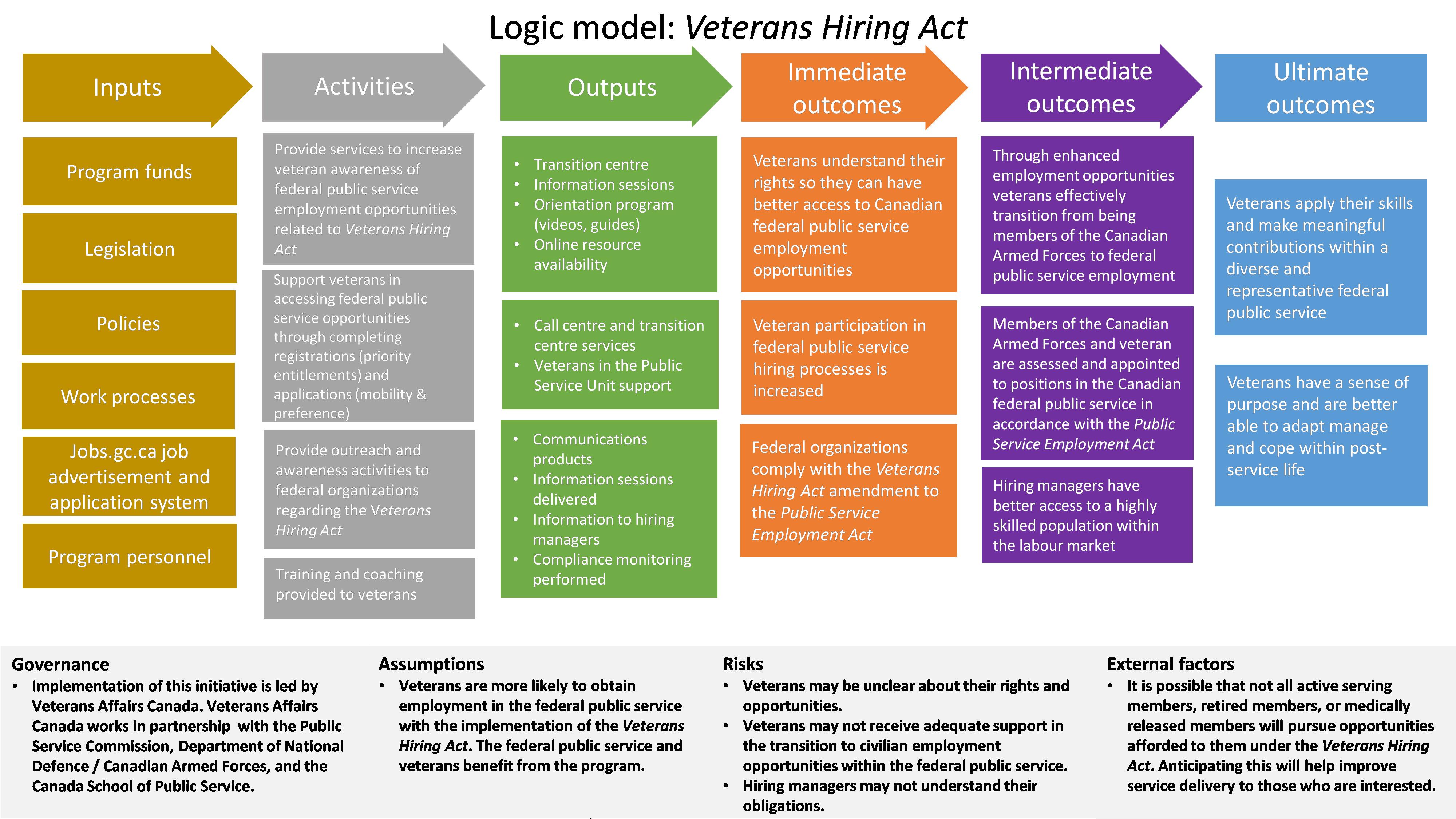

- Annex 1: Veterans Hiring Act logic model

- Annex 2: Evaluation matrix

- Annex 3 - Methodology and limitations

- Annex 4: Veterans Hiring Act survey demographic information

- Annex 5: Department of National Defence Human Resources Civilian National Staffing Operations

- Annex 6: Other programs and services offered by Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group / Director General Military Transition

1.0 Purpose

1.This report provides the results of an evaluation of the implementation of the Veterans Hiring Act. The evaluation was conducted jointly by the internal audit and evaluation directorates of the Public Service Commission of Canada, and Veterans Affairs Canada. The team was supported by the evaluation team within the Assistant Deputy Minister (Review Services), Department of National Defence, and the Canadian Armed Forces.

2.0 Background

2. The Government of Canada has a tradition of supporting veterans in finding work in the public and private sectors. Between 1914 and 1919, a number of programs and benefits were put in place for veterans. These included monthly disability benefits payments and support for veterans wishing to farm and settle. During this period, certain classes of veterans were also provided with a preference to civil service jobs. As well, vocational rehabilitation was provided to injured veterans through a series of federally run hospitals. In the 5 years after World War One, 40 000 veterans were provided with training in 140 different occupations Footnote 1. More land, rehabilitation, education and re-establishment benefits were introduced during World War Two.

3. In 1944, the Department of Veterans Affairs was established and assumed responsibilities for administering rehabilitation programs in partnership with other government departments. Veteran programming has continuously evolved under the department’s mandate, most recently with the introduction of the New Veterans Charter (2006) and the new suite of programs released in 2019 as part of the Pension for Life benefits. In 1984, the applied name of the department (the name commonly used for communication with the public) was changed to Veterans Affairs CanadaFootnote 2.

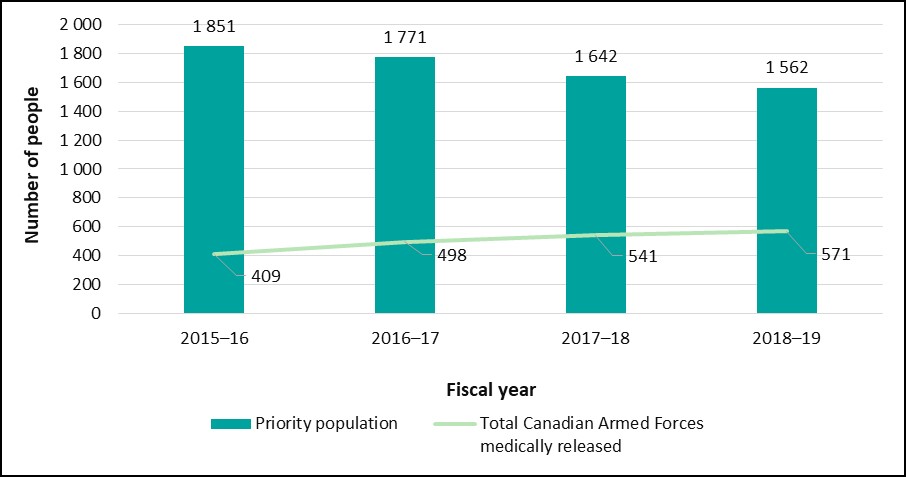

4. In March 2014, the Canadian mission in Afghanistan was formally completed. In the final year of Canada’s involvement, discussions were held to determine how the Government of Canada could support Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans at the end of the mission. The Public Service Commission, Veterans Affairs Canada, and the Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces were the lead departments involved in these discussions. Given approximately 9 000 regular force and reserve members release from service every year, with approximately 2 000 due to medical reasons, a need was identified to support them in obtaining federal public service employmentFootnote 3.

5. These discussions led to the introduction of the Veterans Hiring Act. This act amended the Public Service Employment ActFootnote 4 to provide employment opportunities for veterans and eligible Canadian Armed Forces members into the federal public service, and provide hiring managers with better access to this group of skilled candidates through 3 provisions — priority, preference and mobility. Veteran hiring provisions are contained in the Public Service Employment Act and related regulations. The key changes introduced by the Veterans Hiring Act are the following:

- Priority entitlement. Medically released Canadian Armed Forces members must activate their priority entitlement within 5 years of their release. Once activated, these veterans are provided a 5-year statutory or regulatory priority entitlement within public service appointment processes depending on whether their medical release was attributable to service. This entitlement expires at the end of the 5-year period or when they obtain permanent employment in the federal public service.

- Preference for appointment. If there are no qualified persons with a priority entitlement, a qualified veteran must be appointed to a job that was advertised to the public, before any other Canadian citizen. This applies for 5 years after Canadian Armed Forces members are honourably released, unless they have already found permanent federal public service jobs. Eligible veterans are to be identified in the list of applicants.

- Mobility provision. Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans are treated as employees in advertised internal appointments through the mobility provision. The limits set out in the area of selection do not apply to eligible Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans, except for any employment equity requirements. Canadian Armed Forces members with at least 3 years of service, and veterans, are now eligible to apply and participate in these processes for up to 5 years after being honourably released.

6. Between July 1, 2015, and March 31, 2019, 1 440 medically released veterans (for reasons attributable to service, or not) activated a priority entitlement, and 799 (55%) of them were appointed to federal public service positions. Eligible veterans applied to approximately one quarter of all staffing processes that were advertised to the public through the preference provision. During the same period, eligible Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans used the mobility provision to participate in approximately half of advertised internal appointment processes. From July 1, 2015, to March 31, 2019, 359 veterans were appointed through the preference provision and 509 Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans were appointed through the mobility provision.

3.0 Objective, scope and methodology

Objective

7.The evaluation objective was to assess and report on the efficiency, effectiveness and relevance of public service -wide and departmental initiatives undertaken to support the implementation of the Veterans Hiring Act provisions since July 1, 2015. Specifically, the evaluation reviewed the following:

- Awareness: Canadian Armed Forces member and veteran awareness of federal public service employment opportunities established by the Veterans Hiring Act.

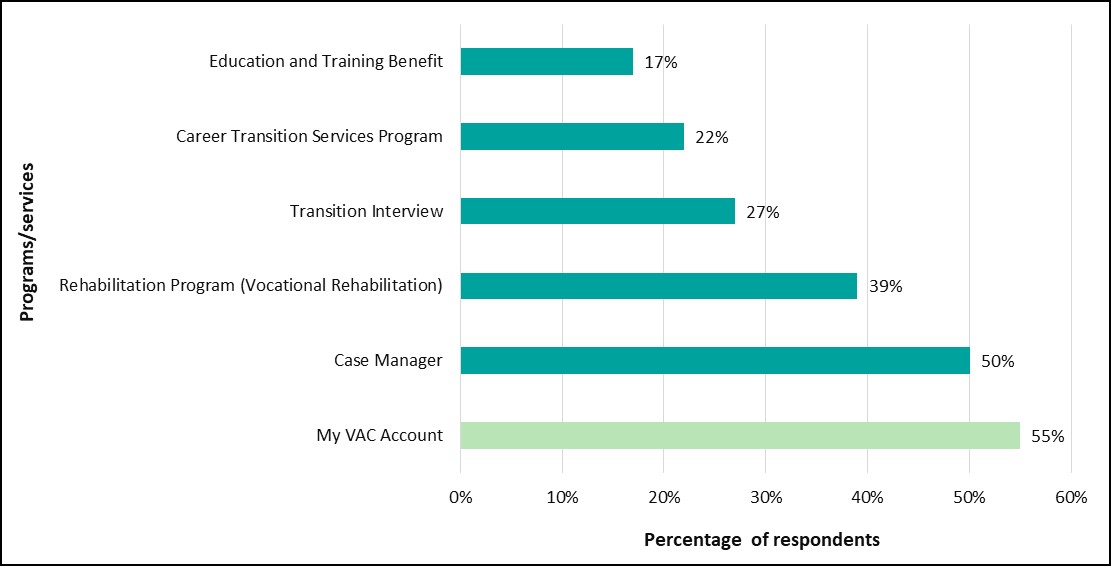

- Support: the level of support provided to eligible Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans interested in pursuing federal public service employment opportunities.

- Appointments: the appointment of eligible Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans in accordance with the provisions established by the Veterans Hiring Act.

8. The report provides a neutral, independent assessment of how public service initiatives have been implemented, and whether they have supported and continue to support government objectives and priorities related to veteran hiring.

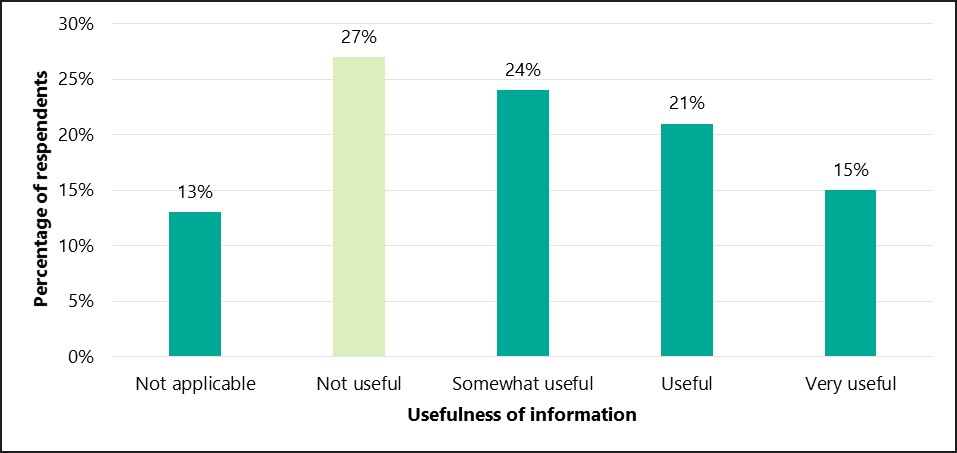

Scope

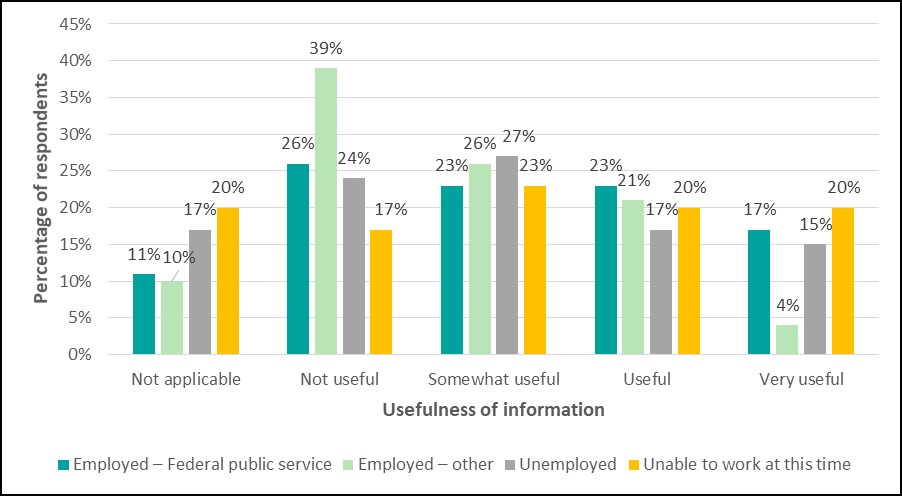

9.This evaluation was included in the Public Service Commission’s Internal Audit and Evaluation Plan 2018–21 and covers the period from July 1, 2015, to March 31, 2019. The evaluation was carried out in accordance with the Treasury Board’s Policy on Results.

Methodology

10.The methodology included multiple lines of evidence derived from the Veterans Hiring Act logic model described in Annex 1, and the evaluation matrix described in Annex 2. The following methods were used to answer the evaluation questions described in the evaluation matrix (see Annex 3 for further details):

- Document review: The document review included an examination of the Veterans Hiring Act, the Public Service Employment Act, and strategic departmental and policy documents (such as, Public Service Commission annual reports and departmental plans). Other key documents were reviewed with various purposes and levels of specificity (for example, other related federal public service program documentation, including ministerial mandate letters and parliamentary reports).

- Literature review: The literature review included articles from peer-reviewed journals, reference books, and newspaper articles providing further insights and perspectives on staffing issues relating to veterans.

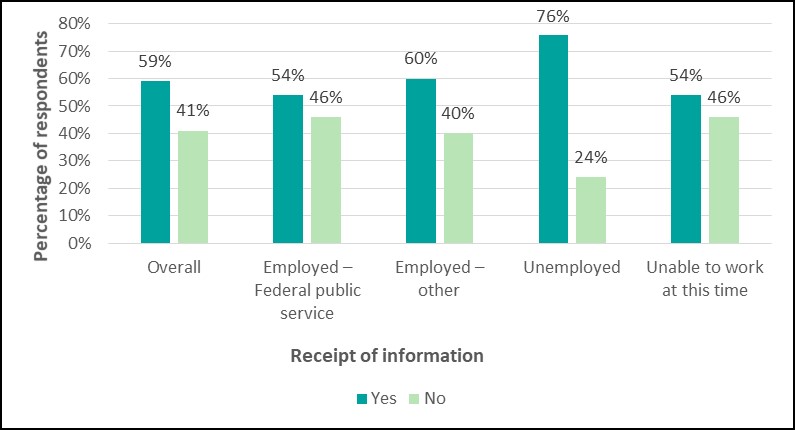

- Review of administrative information and data: The evaluation included obtaining, reviewing and analyzing Veterans Hiring Act administrative and performance data from a variety of sources. This work was conducted in partnership with the Public Service Commission’s Data Services and Analysis Directorate of the Oversight and Investigations Sector. A detailed analysis of relevant questions from the Public Service Commission’s Staffing and Non-Partisanship Survey was also performed to gather information on hiring managers’ and staffing advisors’ level of awareness of their roles in implementing the provisions established by the Veterans Hiring Act.

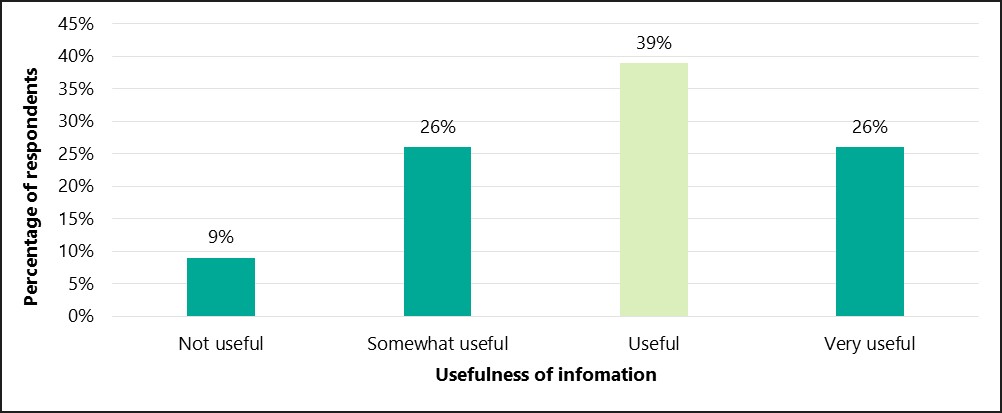

-

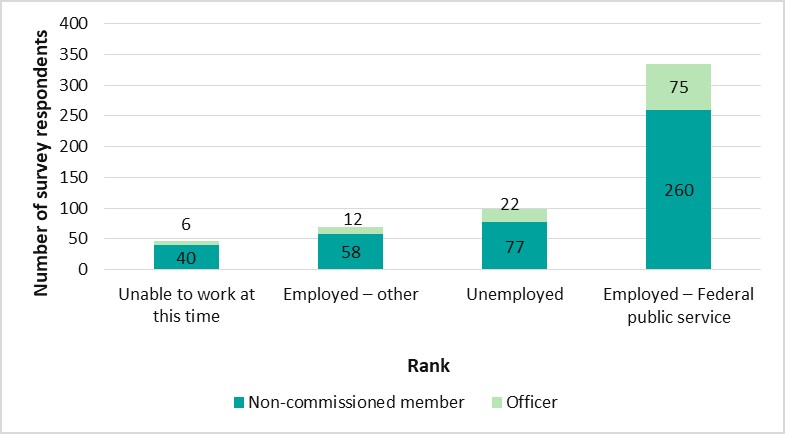

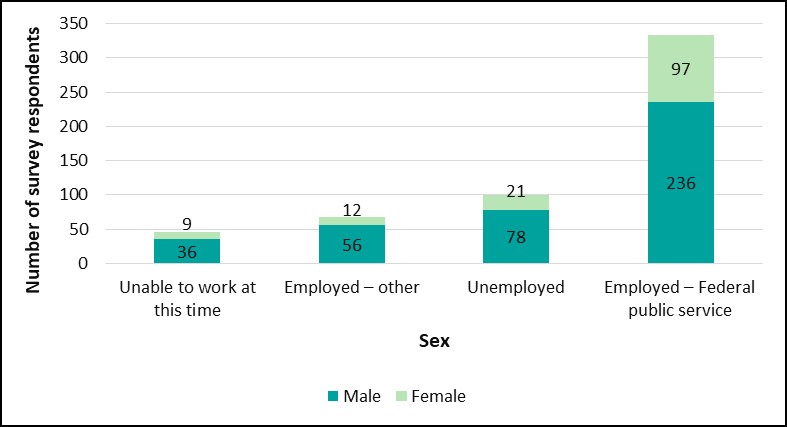

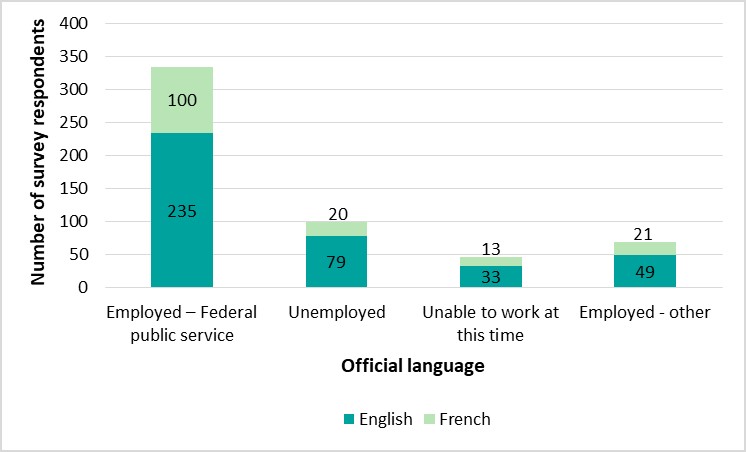

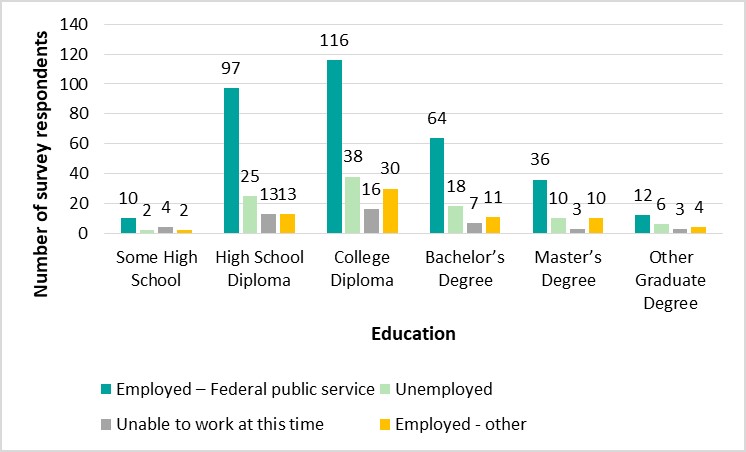

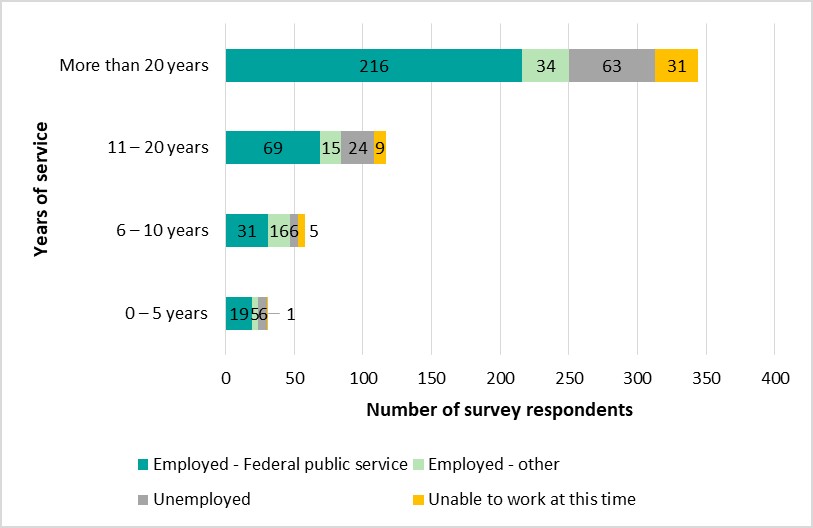

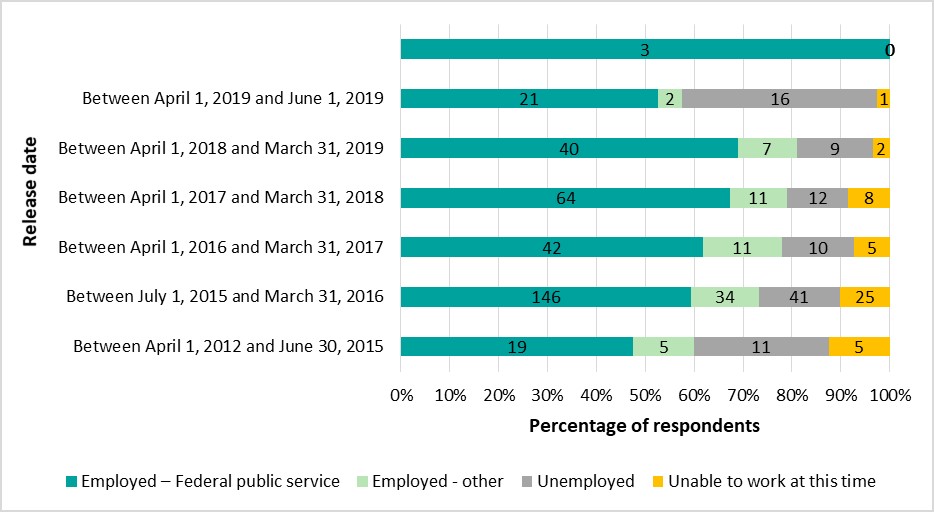

Survey: A survey of veterans with a priority entitlement was administered to gather information on their experiences. The survey was sent to 1 392 veterans who had activated their priority entitlement and registered in the Priority

Information Management System between July 1, 2015, and May 25, 2019. The survey response rate was 39.5%. Graph 1 provides a breakdown of the respondents by employment status. Annex 4 provides more detailed survey respondent

demographic information.

Graph 1 – Survey respondents by employment status, n=550

Text version

Employment status

Number of respondents

Unable to work at this time

46

Employed - other

70

Unemployed

99

Employed - Federal public service

335

- Interviews, site visits and focus groups: Interviews were conducted with various Veterans Hiring Act stakeholders to obtain insight. Site visits were conducted at Veterans Affairs Canada offices and Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces installations in Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. Focus group sessions were held with Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces, Veterans Affairs Canada, Correctional Services Canada, and Public Services and Procurement Canada hiring managers and staffing advisors to obtain insight into efforts being made to increase veteran hiring in these departments.

4.0 Evaluation findings

4.1 Veterans Hiring Act implementation

11.Multiple stakeholders are involved in implementing the Veterans Hiring Act provisions. Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces, Veterans Affairs Canada, and Public Service Commission officials work collaboratively so that eligible Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans are aware of, have access to, and are considered for, federal public service employment opportunities. All departments and agencies that operate under the Public Service Employment Act have an obligation to implement the Veterans Hiring Act provisions.

12.Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces. They support Canadian Armed Forces members who transition from active service to civilian life. The goal is to enable seamless transition and enhanced well-being with special attention to ill and injured personnel, their families, and the families of deceased members.

- Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group / Director General Military Transition: In 2009, Canadian Armed Forces formalized the importance of taking care of ill and injured veterans with the creation of the Joint Personnel Support Unit / Integrated Personnel Support Centers. In December 2018, the Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group / Director General Military Transition was formed to build on the work that had previously been done by the unit and centres. It is mandated to reinvent the transition experience for all transitioning Canadian Armed Forces members and their families. It collaborates with its partners to deliver a personalized, professional and standardized transition process.

- Department of National Defence Human Resources (Civilian): Following Department of National Defence Human Resources -Civilian Next Generation, the department underwent organizational changes including the dismantling of the client services team and the standing up of the new National Priority Management Team, whose roles and responsibilities are discussed further in this report. Annex 5 provides more information on key stakeholders and their roles and responsibilities within the priority management process.

13.Veterans Affairs Canada. It provides support, benefits and services to veterans. The Veterans in the Public Service Unit was established in 2017 Footnote 5 to support veterans in accessing federal public service employment opportunities. This unit consisted of a team of veterans trained in human resources practices that provided direct assistance to those who requested it. Services provided by the unit included:

- helping veterans to understand the public service appointment process in general

- providing résumé and cover letter revision and editing advice

- helping veterans phrase their military experience and training in language easily understood by public service hiring managers

- coaching for assessments and interviews for federal public service job processes

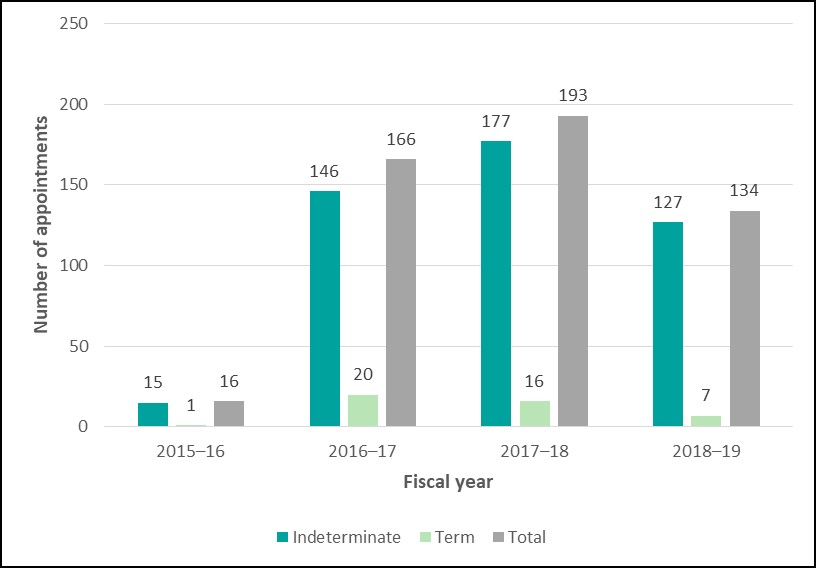

14.In May 2019, an internal Veterans Affairs Canada service-level agreement was signed, splitting the functions of the Veterans in the Public Service Unit. Veterans in the Public Service (Operations), headed by Service Delivery Branch, provides advice to veterans about opportunities in the public service. The Veterans in the Public Service (Strategic), headed by Human Resources Division, focuses on services in support of increasing the number of veterans in the public service.

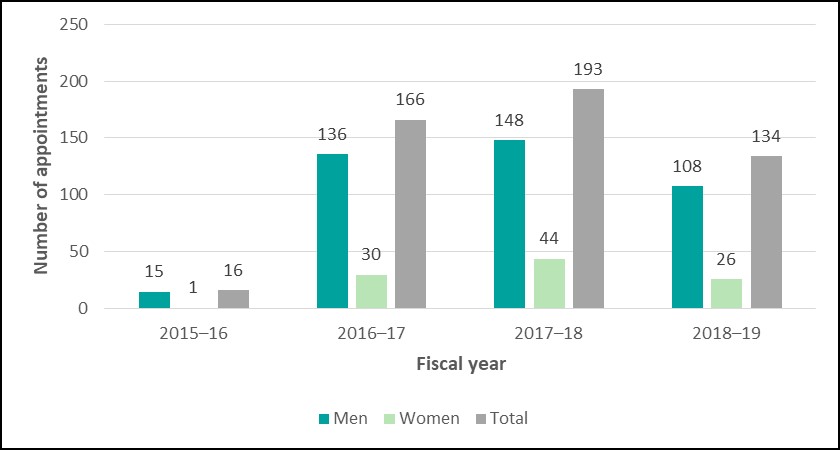

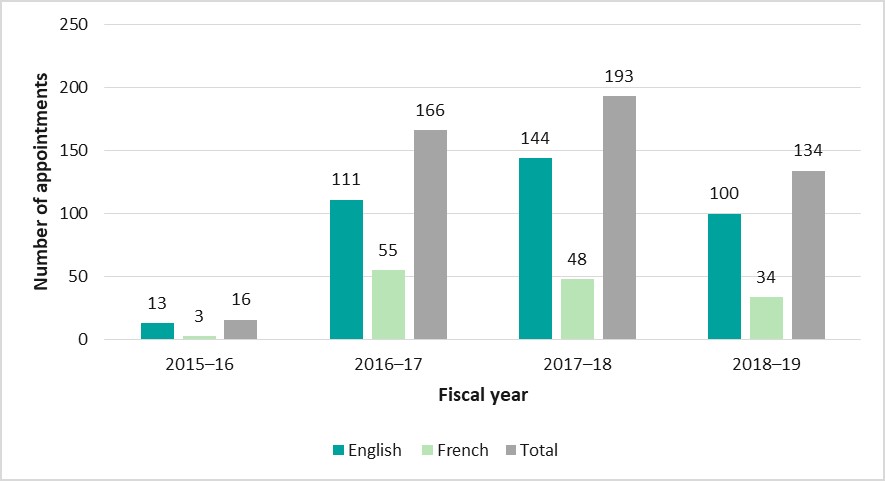

15.Veterans Affairs Canada also has programs to support veterans who seek employment opportunities in the private sector and for those who are unable to work and require care, access to education and other related services.

16.The service-level agreement put in place in May 2019 is in the early stages of implementation and has not been fully funded. With the implementation of the new model, Veterans Affairs Canada is also reviewing all initiatives related to veteran employment.

17.Public Service Commission of Canada. It manages and oversees the implementation of recruitment and staffing policy mechanisms, including the implementation of the Veterans Hiring Act provisions. It also sets and interprets policies, directives, guides and procedures to support departments and agencies in administering priority entitlements.

Collaboration

“The Commission continues to work with Veterans Affairs Canada and the Department of National Defence on initiatives to help veterans find employment. Collectively, the public service needs to do more to retain veterans. Canada’s veterans are a rich source of talent, with valuable knowledge, skills and experience and demonstrated commitment to public service.”

— Public Service Commission of Canada’s 2016–17 Annual Report

19.The Public Service Commission hired 2 veterans to provide guidance and information to medically released veterans registered in the Priority Information Management System. They consult veterans to improve how the Public Service Commission serves them in accessing federal public service employment opportunities. Public Service Commission staffing support advisors, who provide staffing support to all human resources groups across the federal public service, and the Vice-President responsible for this area, continuously raise awareness of the importance of successfully implementing the Veterans Hiring Act.

20.All departments and agencies under the Public Service Employment Act. Staffing advisors and hiring managers from all departments and agencies that operate under the Public Service Employment Act must respect that act, as well as the Veterans Hiring Act provisions, in their staffing actions.

21.When the Veterans Hiring Act was first introduced, there was no overall strategy to ensure consistent implementation of the 3 provisions across the federal public service. The Public Service Commission had worked with the Canada School of Public Service to include information about the Veterans Hiring Act in staffing courses for hiring managers and human resources professionals, and it had offered information sessions on the act ahead of its implementation. But the present evaluation found that those efforts were not sustained to support hiring managers in understanding the Veterans Hiring Act provisions and how to apply them. This evaluation also observed that no hiring goals were established, and no systematic performance measurement strategy was established to track progress in achieving veteran hiring objectives.

22.Since July 2015, approximately 8 departments and agencies have accounted for more than 80% of all hires through the Veterans Hiring Act provisions, with Department of National Defence accounting for 62% of all hires. In recent years, Employment and Social Development Canada, Veterans Affairs Canada, the Correctional Service of Canada, and Public Services and Procurement Canada have developed initiatives to support veteran hiring into their organizations. For example, Veterans Affairs Canada set a goal for veterans to make up 10% of its workforce. While most initiatives to support veteran hiring have been organization-specific, the Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group is working with Veterans Affairs Canada and a number of departments and agencies to determine how these initiatives can be more strategic, and focused system-wide.

4.2 Awareness of the Veterans Hiring Act provisions

23.This section focuses on how Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces, Veterans Affairs Canada, and the Public Service Commission inform eligible Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans about federal public service employment opportunities during and after their transition from military to civilian life.

Canadian Armed Forces / Department of National Defence Programs and Services

24.Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group / Director General Military Transition offers a number of information sessions, services and support mechanisms to transitioning Canadian Armed Forces members, veterans and their families. Table 1 provides an overview of some of these programs and services.

|

Programs and services offered |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Second Career Assistance Network seminar |

This service provides a broad range of information on pension benefits, education benefits, job search tools and networking opportunities. |

|

Vocational Rehabilitation Program for Serving Members |

This program enables eligible Canadian Armed Forces members to start vocational rehabilitation training up to 6 months before their release, with authorized approval. |

|

Transition centres (formally called Integrated Personnel Support Centre) |

Transition centres provide an integrated, one-stop centre where ill and injured Canadian Armed Forces members and their families are offered transition services and casualty support. As well, Canadian Armed Forces members, veterans and their families can go to any local transition centre for information regarding transition-related matters. These centres are operated by staff from Canadian Armed Forces, Veterans Affairs Canada and partners. |

|

Canadian Armed Forces Nurse Case Manager |

Nurse case managers work closely within the Care Delivery Unit to build relationships with Canadian Armed Forces members to help them navigate the health care systems. |

|

Base/Wing Personnel Selection Officer |

These officers provide professional advice to military commanders, particularly in the areas of recruiting, selection, leadership and other human resource issues. |

|

The Guide to Benefits, Programs and Services for Serving and Former Canadian Armed Forces Members and their Families |

The guide provides information on benefits and programs that Canadian Armed Forces members are entitled to if they are injured or become disabled while serving. |

|

Integrated Transition Plan |

Service partners present recommendations for a member’s transition plan, based on each member’s needs. |

|

Operational Stress Injury Social Support |

The Department of National Defence and Veterans Affairs Canada work in partnership to deliver Operational Stress Injury Social Support. This service establishes, develops, and improves social support programs for Canadian Armed Forces members. It also provides an understanding and acceptance of occupational stress injuries. |

|

Education Reimbursement for Canadian Armed Forces Members |

This program allows for the reimbursement of both regular force and reserve force personnel, for eligible costs incurred in studying at a Canadian university, college, or high school to get a degree or diploma. The reimbursement rate varies between 100% for regular force members, and 50% for reserve force personnel (reservists are limited to a maximum of $2,000 per year, and a total career maximum of $8,000). The Canadian Armed Forces also offers a third Educational Reimbursement program (the Skills Completion program): members with 10 years of regular force service (who do not already have a degree or diploma) can access up $5,400, which can be used towards a skills-based program of study to gain a civilian qualification that will enhance their military training and experiences. |

|

Military Family Resource Centre |

Located on Canadian Armed Forces bases and wings, these centres provide a suite of programs and services for medically released veterans and their families, via the Veteran Family Program (funded by Veterans Affairs Canada), to help ease the transition to post-service life. This includes enhanced information and referral, system navigation, as well as employment and volunteer programs. |

|

Integrated Transition Plan |

The plan is an integrated process part of the Career Transition Support Policy for severely ill and injured military members. It aims to give the appropriate time and services to prepare Canadian Armed Forces members (mostly health-wise) to engage in various programs, including education reimbursement options. |

25.Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group / Director General Military Transition offer other services and programs that are detailed in Annex 6.

26.Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group / Director General Military Transition services and programs are overseen in Ottawa, but delivered at 9 transition units, 32 transition centres, supported by 40 base and wing personnel selection offices and online platforms across Canada and abroad. Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group / Director General Military Transition continues to develop additional modernized transition resources and processes, such as:

- MY Skills and Education Translator (MYSET), a centralized online database that will offer post-secondary education advanced standing based on military skills and experience for all Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans.

- The ongoing Transition Trial in Canadian Forces Base Borden, which provides a test bed for modernizing military to civilian transition capability, transition processes and tools before implementation on a national scale. This includes the Canadian Armed Forces release renewal process, an online application process that will replace the need to submit a memorandum or the current form. It will simplify, standardize and enhance proficiency for both release administrators and transitioning Canadian Armed Forces members.

- National Resource Database, which will provide direct linkage between members and organizations to Canadian Armed Forces valued resources to support all aspects of the well-being of members, veterans and their families.

- Canadian Armed Forces / Veterans Affairs Canada Seamless Transition Roadmap, which highlights the many actions of Veterans Affairs Canada and the Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces to improve the transition experience for serving members, veterans and their families.

27.In the past, many of these programs were offered during the final 2 years of a member’s active service and were aimed at providing information to support members in achieving a successful transition. The Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group / Director General Military Transition is currently studying different approaches to provide information at various points during a member’s career.

28.Seventy-eight percent of evaluation survey respondents used a Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group / Director General Military Transition or Veterans Affairs Canada service during their transition. Graph 2 provides an overview of the percentage of respondents who used Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group / Director General Military Transition programs / services.

Text version

|

Program / services |

Percentage of respondents |

|

Second Career Assistance Network seminar |

58% |

|

Vocational Rehabilitation Program |

36% |

|

Transition centres |

31% |

|

Canadian Armed Forces Nurse Case Manager |

26% |

|

Base/Wing Personnel Selection Officer |

23% |

|

Guide to Benefits, Programs and Services for Serving and Former Canadian Armed Forces Members and their Families |

20% |

|

Military Family Resource Centres |

9% |

|

Integrated Transition Plan |

7% |

|

Education Reimbursement for Primary Reserves |

4% |

|

Operational Stress Injury Social Support |

4% |

|

Other programs |

3% |

29.Overall, the Second Career Assistance Network seminar was the most commonly used service, attended by 58% of survey respondents. These seminars are typically 2 or 3 full-day events held across Canada informing Canadian Armed Forces members and their families of the support offered to them during the transition process. Interviewed case managers believed that these seminars are important and should include more information on the Veterans Hiring Act to enhance awareness of federal public service employment opportunities. The Director General Military Transition has recently put these seminars online so that all Canadian Armed Forces members, their families and veterans have access to the information provided as part of the transition process.

30.The evaluation team met with Canadian Armed Forces Transition Centre officials in Halifax and Edmonton to better understand how they support Canadian Armed Forces members during the transition process. Transition centres aim to provide professional, timely, compassionate services to transitioning military members. Some interviewees indicated that a number of Canadian Armed Forces members tell them that they do not feel they receive adequate information about theVeterans Hiring Act provisions during the transition process. Personnel interviewed in Halifax saw themselves as part of a larger, cross-country network and have established good working relations with the Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group / Director General Military Transition headquarters in Ottawa, and with military installations in Atlantic Canada, particularly with Maritime Forces Atlantic.

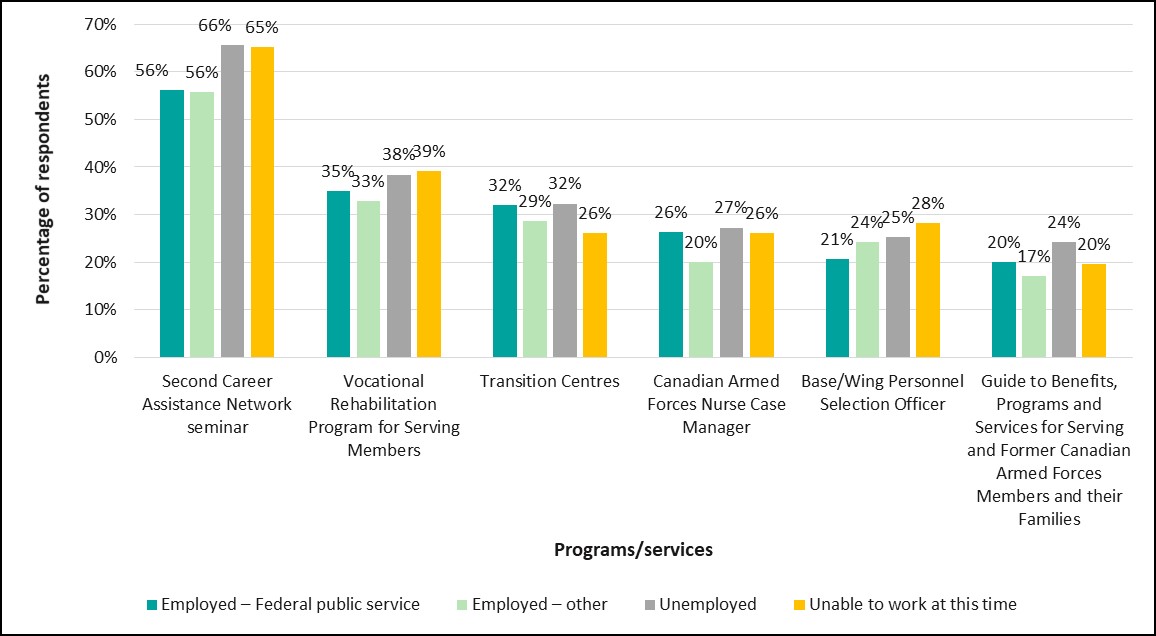

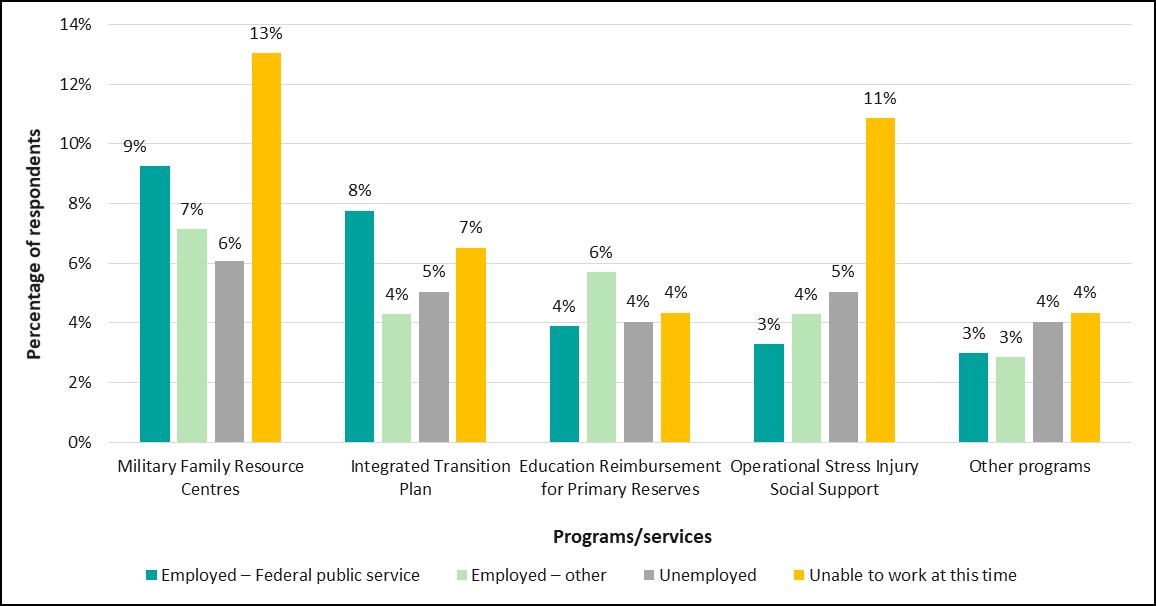

31.The evaluation observed that certain types of programs accessed during the transition process may be indicators of an individual’s potential ability to work after release. For example, those who used operational stress injury services were more likely to be unable to work (see graphs 3 and 4).

Text version

|

Programs / services |

Employed – Federal public service |

Employed – other |

Unemployed |

Unable to work at this time |

|

Second Career Assistance Network seminar |

56% |

56% |

66% |

65% |

|

Vocational Rehabilitation Program for Serving Members |

35% |

33% |

38% |

39% |

|

Transition Centres |

32% |

29% |

32% |

26% |

|

Canadian Armed Forces Nurse Case Manager |

26% |

20% |

27% |

26% |

|

Base/Wing Personnel Selection Officer |

21% |

24% |

25% |

28% |

|

Guide to Benefits, Programs and Services for Serving and Former Canadian Armed Forces Members and their Families |

20% |

17% |

24% |

20% |

Text version

|

Programs / services |

Employed – Federal public service |

Employed – other |

Unemployed |

Unable to work at this time |

|

Military Family Resource Centres |

9% |

7% |

6% |

13% |

|

Integrated Transition Plan |

8% |

4% |

5% |

7% |

|

Education Reimbursement for Primary Reserves |

4% |

6% |

4% |

4% |

|

Operational Stress Injury Social Support |

3% |

4% |

5% |

11% |

|

Other programs |

3% |

3% |

4% |

4% |

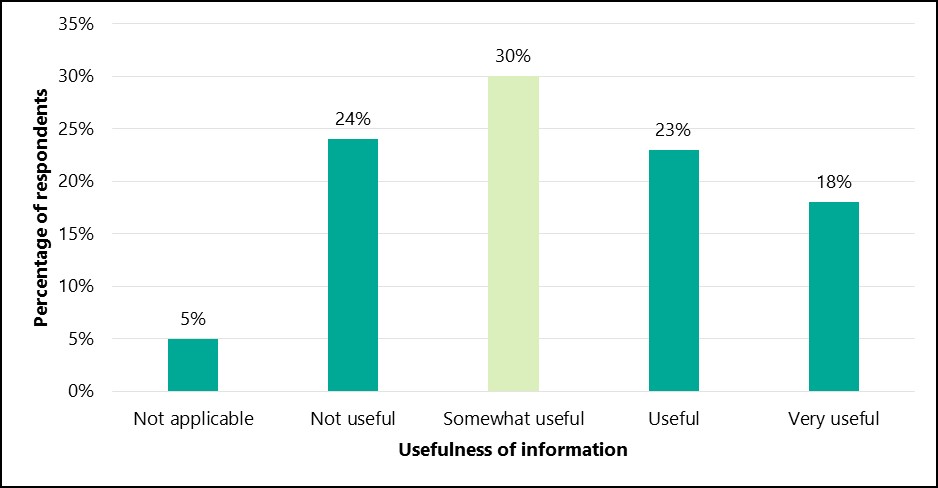

32.As part of the survey, respondents rated the usefulness of the information they received from Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group / Director General Military Transition during the transition process. Overall, 71% of respondents indicated that the information was somewhat useful or better (see Graph 5).

Text version

|

Usefulness of information |

Percentage of respondents |

|

Not applicable |

5% |

|

Not useful |

24% |

|

Somewhat useful |

30% |

|

Useful |

23% |

|

Very useful |

18% |

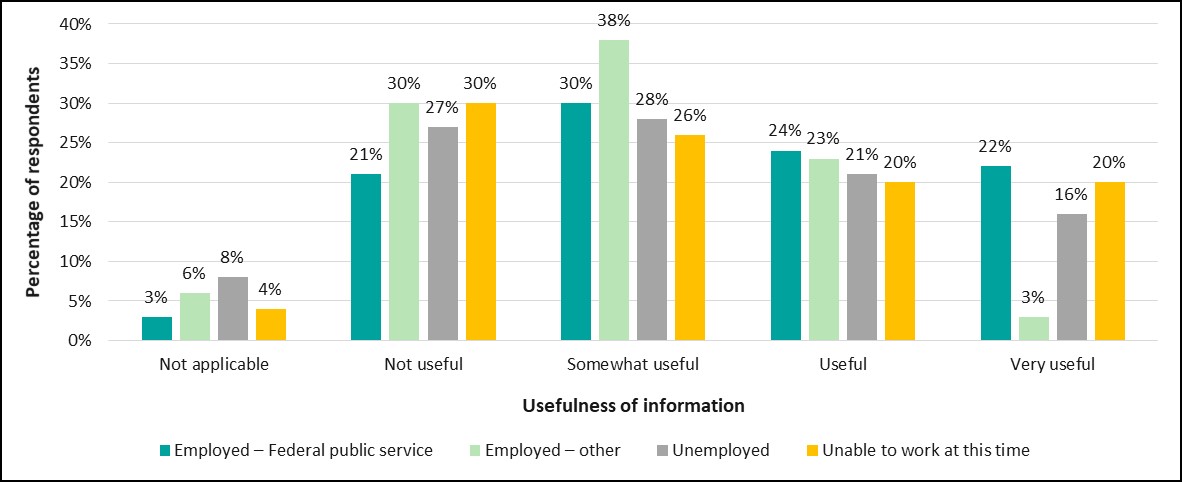

33.The evaluation observed that respondents’ perceptions of usefulness of information differed based on their employment status (see Graph 6). For example, there was a variance in “very useful” responses between veterans employed in the federal public service (22%) and veterans employed outside the federal public service (3%). As well, veterans who are unable to work and those employed outside the federal public service had the same percentage of “not useful” (30%) responses.

34.The evaluation found that one issue that impacts Canadian Armed Forces members who medically release is the time it takes to receive a determination of whether their medical release is due to service. The 16-week service standard is currently being met 59% of the time. This step is normally completed after a member is released, but survey respondents indicated that they would appreciate receiving this information before they release. This was also identified in the 2019 Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates report on veteran hiring, which found that the timeliness of these types of decisions affected the time it takes for veterans to be registered in the Priority Information Management System gain access to federal public service jobs Footnote 6.

Text version

|

Usefulness of information |

Employed – Federal public service |

Employed – other |

Unemployed |

Unable to work at this time |

|

Not applicable |

3% |

6% |

8% |

4% |

|

Not useful |

21% |

30% |

27% |

30% |

|

Somewhat useful |

30% |

38% |

28% |

26% |

|

Useful |

24% |

23% |

21% |

20% |

|

Very useful |

22% |

3% |

16% |

20% |

35.An Assistant Deputy Minister (Review Services) evaluation report on the military transition program to be published in 2020 notes that the Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group is transforming its services to strengthen the support provided to Canadian Armed Forces members and their families during the transition to civilian life.

Veterans Affairs Canada programs and services

36.Veterans Affairs Canada fulfills its mandate by delivering programs and services to veterans, including disability benefits, financial benefits, rehabilitation, pension advocacy, education, and training support. Table 2 provides an overview of some of the programs that support veterans and their families with regard to employment and income replacement. It should be noted that Veterans Affairs Canada programming changed significantly during the period of the evaluation.

|

Program and services offered |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Veterans Affairs Canada Rehabilitation Program – Vocational Assistance Component |

Provides veterans with skills development, education, training, and other support mechanisms to help them establish a new career. |

|

Income Replacement Benefit |

Provides a taxable monthly benefit equal to 90% of a veteran's salary on release, indexed annually, with a minimum of $48,600 per year. The salary of veterans with a diminished earning capacity will also be increased by 1% per every year until they reach what would have been 20 years of service or age 60. If a veteran has a diminished earning capacity before age 65, the benefit may be payable for life. After the veteran reaches the age of 65, instead of 90% of the release salary, they will receive 70% of the amount, less offsets. |

|

Earnings Loss Benefit Program |

Provided eligible veterans in the Rehabilitation Program with an income replacement of 90% of their pre-release military salary. |

|

Supplementary Retirement Benefit* |

Provided a taxable lump-sum benefit to veterans at the age of 65 to recognize their decreased ability to save for retirement. |

|

Career Impact Allowance* |

Provided a taxable monthly allowance for life to eligible veterans to compensate for their economic loss due to service-related injury or illness. |

|

Career Impairment Allowance Supplement* |

Provided a taxable monthly allowance to those with a diminished earning capacity preventing them from performing any occupational roles. |

|

Retirement Income Security Benefit* |

Provided a taxable monthly benefit for life after age 65, calculated at 70% of a veteran’s Earnings Loss. |

|

Canadian Forces Income Support |

Provides a tax-free monthly benefit (basic income) to aid veterans who cannot find employment while they engage in a job search. |

|

Career Transition Services |

Provides eligible veterans with market information, career counselling and job-finding assistance in order to effectively obtain employment. |

|

Education and Training Benefit |

Provides veterans with a taxable benefit of up to $80,000 to cover tuition fees, and some incidental expenses, while they attend school. |

|

Case Management Services |

Enable recipients to achieve mutually agreed-upon goals through a collaborative, organized and dynamic process. The process is coordinated by a Veterans Affairs Canada case manager, who works with recipients to monitor and evaluate progress. The case manager also adjusts the case management plan to help recipients reach their goals and optimize their level of independence and well-being. Goals and improvements to well-being are targeted for individuals with complex needs in areas such as physical health, mental health, employment, financial, housing, social integration and life skills. Veterans who do not require the services of a case manager are often assigned to veteran service agents to ensure their needs are met with regard to the coordination and integration of programs and services. |

|

My VAC Account |

An online portal where veterans can:

|

|

Transition Interview |

This service is available to all Canadian Armed Forces members (regular and reserve) who have started or are planning to start the release process. |

|

Operational Stress Injury Clinics |

Provide assessment, treatment, prevention and support to serving Canadian Armed Forces members, veterans and Royal Canadian Mounted Police members and former members. Treatment options at each operational stress injury clinic are on an outpatient basis and include one-on-one therapy sessions and group sessions to address anxiety, insomnia, anger and other issues occurring as a result of a mental health disorder. |

Text version

|

Programs / services |

Percentage of respondents |

|

My VAC Account |

55% |

|

Case Manager |

50% |

|

Rehabilitation Program (Vocational Rehabilitation) |

39% |

|

Transition Interview |

27% |

|

Career Transition Services Program |

22% |

|

Education and Training Benefit |

17% |

38.The evaluation found that My VAC Account was the most common service used by veterans. Fifty-five percent of survey respondents used this tool, while 50% consulted Veterans Affairs Canada case managers. Case managers indicated that it would be beneficial if My VAC Account were used as a one-stop-shop to inform veterans about the support available to them to find jobs with the federal public service. An analysis of the use of programs and services by survey respondents and employment status demonstrates that those who were unable to work were more likely to use My VAC Account, Veterans Affairs Canada case managers, and the Veterans Affairs Canada rehabilitation program (see Graph 8).

Text version

|

Programs / services |

Employed – Federal public service |

Employed – other |

Unemployed |

Unable to work at this time |

|

My VAC Account |

53% |

46% |

58% |

72% |

|

Case Manager |

47% |

47% |

57% |

61% |

|

Rehabilitation Program (Vocational Rehabilitation) |

38% |

33% |

36% |

63% |

|

Career Transition Services Program |

19% |

26% |

27% |

28% |

|

Education and Training Benefit |

19% |

4% |

16% |

15% |

|

Transition Interview |

26% |

23% |

28% |

33% |

|

Veterans Service Agent |

15% |

27% |

14% |

17% |

39.Veterans Affairs Canada case managers each work with approximately 30 to 35 veterans who are experiencing complex issues (though in some regions, the caseload may be larger). Veterans Affairs Canada’s veteran service agents are responsible for approximately 1 200 veterans who generally have less complicated needs. Based on the workload and veterans’ needs, it is sometimes difficult for case managers and veteran service agents to meet expectations and provide timely advice to those who seek it. The evaluation team was informed that there is a relatively high staff turnover of Veterans Affairs Canada case managers. One survey respondent highlighted the fact that they received valuable advice from their case manager and that they were instrumental in helping them navigate the various programs, which ultimately assisted them in getting a federal public service position.

40.A number of interviewed case managers identified a lack of training and consistent and clear guidance on the Veterans Hiring Act provisions. Interviewees indicated that this has resulted in varying efforts in providing veterans with adequate support and information on the Veterans Hiring Act. Interviewees also stressed that they need simple, concrete information to hand to veterans on the Veterans Hiring Act provisions. One suggestion by interviewees was to dedicate a training session for case managers on how to best inform veterans of the Veterans Hiring Act and to make the session available to all case managers across the country.

41.As part of the survey, respondents rated the usefulness of information provided by Veterans Affairs Canada. Sixty percent of respondents found the information somewhat useful or better (see Graph 9).

Text version

|

Usefulness of information |

Percentage of respondents |

|

Not applicable |

13% |

|

Not useful |

27% |

|

Somewhat useful |

24% |

|

Useful |

21% |

|

Very useful |

15% |

42.The evaluation found that respondents’ perceptions of usefulness of information varied based on their employment status (see Graph 10). For those unable to work, responses were fairly consistent across the 5 choices (at approximately 20% each). The largest discrepancy was for people employed outside the federal public service. For this category, only 4% rated the information as very useful, and 39% rated the information as not useful.

43. One common theme was the frustration related to understanding how the skills acquired during an individual’s military career could meet federal public service merit criteria on job advertisements. While there is a basic tool that translates a military occupation to a civilian equivalent National Occupation Code, the tool does not demonstrate how veterans’ skills match those required in the federal public service. As well, many military occupations identified in the tool have no civilian equivalent. Survey respondents who had difficulty finding employment indicated that the lack of tools and assistance with this aspect of their transition led to fewer options within the federal public service and to being offered lower level positions than they expected. In April 2019, a joint initiative led by Employment and Social Development Canada and supported by Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group / Director General Military Transition was launched to help eligible candidates find jobs in the department. The initiative aims to speed up the process to screen in interested Canadian Armed Forces members to an interview with the department. The pilot will be limited to Canadian Armed Forces members who attended a Second Career Assistance Network seminar within the past 2 years in the National Capital Region. If successful, this initiative will improve the process for Canadian Armed Forces members applying to public service jobs.

Text version

|

Usefulness of information |

Employed – Federal public service |

Employed – other |

Unemployed |

Unable to work at this time |

|

Not applicable |

11% |

10% |

17% |

20% |

|

Not useful |

26% |

39% |

24% |

17% |

|

Somewhat useful |

23% |

26% |

27% |

23% |

|

Useful |

23% |

21% |

17% |

20% |

|

Very useful |

17% |

4% |

15% |

20% |

44.As of June 30, 2019, Veterans Affairs Canada has provided advice, guidance, and information on priority hiring to 758 veterans. As mentioned earlier in this report, Veterans Affairs Canada is implementing a new internal service-level agreement to improve support to veterans seeking employment in the federal public service.

45.Survey respondents indicated that there might be an opportunity to strengthen how veterans are informed of Veterans Hiring Act provisions. Interviewed case managers mentioned that many of the veterans they interacted with did not understand, or had limited knowledge of, the Veterans Hiring Act provisions. Interviewees indicated that Veterans Affairs Canada could play a larger role in providing guidance and training to veterans about federal public service hiring. As well, the evaluation found that Veterans Affairs Canada could use the contractors who deliver vocational rehabilitation and career transition services to inform veterans of employment opportunities provided through the Veterans Hiring Act.

Information provided by the Public Service Commission to veterans

46.The inventory of persons with a priority entitlement has changed over time. Before July 2015, it was largely composed of those who had been affected by the Deficit Reduction Action Plan in 2012–14. Veterans now account for more than one-third of persons with a priority entitlement in the system. Due to the increased share of veterans in the inventory of persons with a priority entitlement, in December 2018, the Public Service Commission launched an orientation program for persons with a priority entitlement, including veterans (who make up 37% of the 1 600 individuals currently in the Priority Information Management System). The program provides veterans with the information they need to increase their odds of finding jobs in the federal public service. These orientation sessions are provided by the Public Service Commission both in-person and online. As of July 2019, a total of 49 veterans with a priority entitlement had participated in one of the 15 orientation sessions, 5 of which were offered at Canadian Armed Forces installations in March 2019.

47.The Public Service Commission provides information to veterans and eligible Canadian Armed Forces members on federal public service jobs and how to apply. Fifty-nine percent of survey respondents indicated that they had received information from the Public Service Commission during their transition. This number was consistent each year for veterans who had taken their release since April 1, 2012. Another 41% of survey respondents indicated that they did not receive information from the Public Service Commission during their transition — even though the Public Service Commission contacted 100% of veterans registered in the Priority Information Management System over the past 2 years. See Graph 11 for the percentage of those who indicated they received information from the Public Service Commission by employment status.

Text version

|

Receipt of information |

Overall |

Employed – Federal public service |

Employed – other |

Unemployed |

Unable to work at this time |

|

Yes |

59% |

54% |

60% |

76% |

54% |

|

No |

41% |

46% |

40% |

24% |

46% |

48.As part of the survey, respondents rated the usefulness of the information provided by the Public Service Commission. Overall, 91% of respondents indicated that the information was somewhat useful or better (see Graph 12).

Text version

|

Usefulness of information |

Percentage of respondents |

|

Not useful |

9% |

|

Somewhat useful |

26% |

|

Useful |

39% |

|

Very useful |

26% |

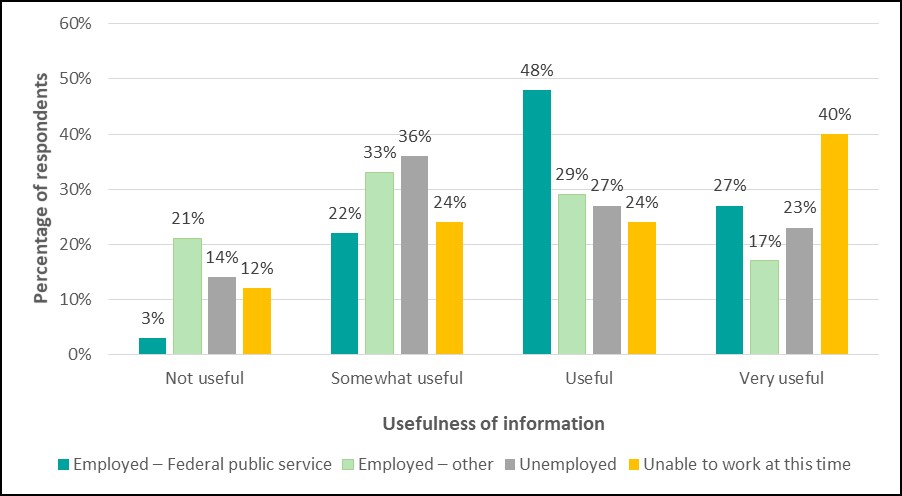

49.Survey respondents generally found the information provided by the Public Service Commission useful. Veterans employed outside the federal public service were the only exception: 21% did not find the information useful (see Graph 13)

Text version

|

Usefulness of information |

Employed – Federal public service |

Employed – other |

Unemployed |

Unable to work at this time |

|

Not useful |

3% |

21% |

14% |

12% |

|

Somewhat useful |

22% |

33% |

36% |

24% |

|

Useful |

48% |

29% |

27% |

24% |

|

Very useful |

27% |

17% |

23% |

40% |

50.Survey respondents identified areas for improvement related to how the Public Service Commission communicates with veterans. For example, they identified a barrier when registering in the Priority Information Management System. As part of the process, veterans must choose federal public service occupational classifications, although they have little knowledge of how these classifications match their skills sets and military experience. In order to close this gap, a new National Priority Management Team within the Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces was created to help veterans and Canadian Armed Forces members with registration by discussing the process and their preferences with them, as well as completing most of the administrative portion for them. The registration service offered by the new team also includes working with veterans to determine which occupational classifications to enter into their system profile.

51.Another perceived barrier was the merit criteria on job advertisements, which often require recent experience for a position. Some survey respondents stated that the recent experience criterion made many processes inaccessible to them, as some medically released Canadian Armed Forces members require several years of vocational rehabilitation before returning to the labour market. Delays in reactivating security clearances and difficulties in updating second language profiles were also seen as barriers. The challenges identified by survey respondents are supported by the results of the evaluation team’s literature review. For example, the 2019 report of the Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates also observed that the staffing process was “too complex and not veteran-centric Footnote 7.”

52.Public Service Commission officials collaborated with Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces and Veterans Affairs Canada teams during the early stages of Veterans Hiring Act implementation and continue to work together to support veterans in applying for federal public service jobs. Concerted efforts have also been made to reach out to veterans registered in the Priority Information Management System to learn from their experiences and offer information as required.

General perception about the information received

53.The evaluation found opportunities for improvement in how Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans are informed about the Veterans Hiring Act provisions. Before December 2018, information was provided through Second Career Assistance Network seminars and through other programs and services, covering all aspects of life after service. There was often a significant time lapse between when a person received information on employment in the federal public service through a seminar offered in their region, and when they needed that information to apply for jobs. As well, survey respondents indicated that the amount of information provided to them was at times overwhelming and difficult to interpret. It is likely for these reasons that interviewees suggested that information about the Veterans Hiring Act provisions be provided when veterans are ready to return to work rather than early in the transition process.

54.As a result of how information has been provided to Canadian Armed Forces members in the past, some have faced challenges in navigating their transition to civilian life. According to the Assistant Deputy Minister (Review Services) evaluation of the military transition program report to be published in 2020, “evidence suggests that, while almost all members receive some form of information on transition services prior to their release, the quality of that information is inconsistent, leading to limited awareness and understanding of available services among Canadian Armed Forces members.” The report also mentions that the “lack of integration of transition-related policies and procedures between Canadian Armed Forces and Veterans Affairs Canada, are among the gaps identified through interviews and literature review.” It is within this context that released Canadian Armed Forces members have been provided information up until December 2018 and why the work currently underway by the Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group to improve the transition process is so important.

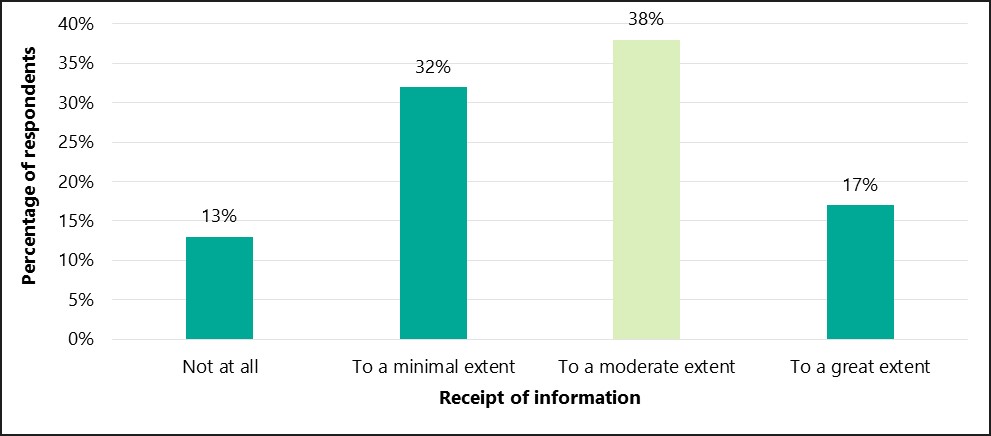

55.Survey respondents rated the extent to which they believed they received the right information at the right time to support them in their awareness of federal public service employment opportunities and knowledge of how to apply for them. Overall, 55% responded that they received the right information at the right time to a moderate or great extent (see Graph 14).

Text version

|

Receipt of information |

Percentage of respondents |

|

Not at all |

13% |

|

To a minimal extent |

32% |

|

To a moderate extent |

38% |

|

To a great extent |

17% |

56.The evaluation found that respondents’ perceptions of whether they received the right information at the right time varied based on their employment status (see Graph 15). For example, there was a variance in “very useful” responses between veterans employed in the federal public service (20%) and those employed outside the federal public service (6%). As well, 61% of veterans who are unable to work responded “not at all” or “to a minimal extent.”

Text version

|

Receipt of the right information at the right time |

Employed – Federal public service |

Employed – other |

Unemployed |

Unable to work at this time |

|

Not at all |

12% |

14% |

12% |

20% |

|

To a minimal extent |

26% |

40% |

42% |

41% |

|

To a moderate extent |

42% |

40% |

27% |

28% |

|

To a great extent |

20% |

6% |

19% |

11% |

57.The Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group has made improvements in these areas in the past 6 months with the creation of the online Second Career Assistance Network, the online transition application, and other tools and guidance documents. As well, Veterans Affairs Canada is assessing how to improve the way that veterans are informed of federal public service employment opportunities. The department also hosted its first career and education fair on May 4, 2019, in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, to support veterans and their families as they transition to meaningful careers in civilian life. The fair included booths for employers, educational institutions, volunteer organizations and other Veterans Affairs Canada partners showcasing opportunities for veterans. The Public Service Commission’s regional office in Halifax delivered a presentation at this event promoting the use of the GC Jobs application portal and providing information on the federal public service hiring process. Over 40 exhibitors and more than 100 veterans participated. Veterans Affairs Canada is looking to host more of these career and education fairs across the country in 2020.

General perception about the transition experience

58.As part of the survey, respondents were asked to rate the extent to which they believed they had a successful transition experience. Overall, 49% identified their transition experience as successful to a moderate or great extent (see Graph 16). Canadian Armed Forces Transition Group officials interviewed estimated that approximately one-third of Canadian Armed Forces members have relatively poor transition experiences, one-third have relatively good experiences and one-third are somewhere in the middle. The survey results are in line with this estimate.

Text version

|

Extent of successful transition |

Percentage of information |

|

Not at all |

19% |

|

To a minimal extent |

32% |

|

To a moderate extent |

27% |

|

To a great extent |

22% |

59.Perceptions about the transition experience varied based on employment status (see Graph 17). For example, those least satisfied with their transition were employed outside the federal public service. Thirty-eight percent of respondents who obtained a federal public service job also saw their transition experience as successful to a minimal extent or not at all.

Text version

|

Value |

Employed – Federal public service |

Employed – other |

Unemployed |

Unable to work at this time |

|

Not at all |

12% |

31% |

26% |

26% |

|

To a minimal extent |

26% |

46% |

44% |

33% |

|

To a moderate extent |

32% |

19% |

18% |

26% |

|

To a great extent |

30% |

4% |

12% |

15% |

60.Each transition experience is unique, and Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces and Veterans Affairs Canada are working to ensure that every released Canadian Armed Forces member receives individual support to allow them to be successful in life after service. The evaluation also found a recognized need for an overall strategy to better coordinate activities across the federal public service to ensure that awareness and support efforts by Veterans Affairs Canada, Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces and the Public Service Commission lead to more departments and agencies hiring qualified veterans.

Hiring managers’ and staffing advisors’ awareness of Veterans Hiring Act provisions

61.This section assesses the extent to which hiring managers and staffing advisors across the federal public service understand their roles and responsibilities with respect to Veterans Hiring Act implementation.

62.The Public Service Commission delivers outreach activities to raise awareness of provisions of the Veterans Hiring Act, and it provides advice and guidance to staffing advisors and hiring managers. Since 2015, the Public Service Commission has focused on enabling federal public service departments and agencies to hire veterans so that their knowledge, skills and experiences can continue to contribute to achieving government priorities. The evaluation team analyzed the results of the Public Service Commission’s 2018 Staffing and Non-Partisanship Survey to assess the extent to which hiring managers and staffing advisors understood their roles and responsibilities related to the Veterans Hiring Act provisions. The evaluation team also conducted interviews with staffing advisors and hiring managers from 4 federal departments and agencies (Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces, Veterans Affairs Canada, Public Services and Procurement Canada and the Correctional Service of Canada).

Hiring managers

63.The Staffing and Non-Partisanship Survey asked hiring managers to rank how well they understood the provisions that help veterans gain employment in the federal public service. Table 3 provides a list of the departments and agencies whose hiring managers ranked themselves the highest in this regard. In general, hiring managers ranked themselves relatively low in terms of their understanding, and all organizations had a rating of great and moderate at 54%.

|

Department |

Great extent |

Moderate extent |

Total great plus moderate |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Canadian Space Agency |

68% |

26% |

94% |

|

Public Service Commission of Canada |

58% |

28% |

86% |

|

Veterans Affairs Canada |

48% |

37% |

85% |

|

Military Grievance External Review Committee |

64% |

18% |

82% |

|

Canadian Transportation Agency |

50% |

31% |

81% |

|

Canada Economic Development for the Region of Quebec |

52% |

28% |

80% |

|

Veterans Review and Appeal Board |

57% |

21% |

78% |

|

Financial Consumer Agency of Canada |

50% |

25% |

75% |

|

National Energy Board |

46% |

26% |

72% |

|

Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages |

48% |

22% |

70% |

64.Most organizations in the top 10 are small departments and agencies. The Department of National Defence is not one of the top 10 organizations, even though it has hired approximately 62% of all veterans recruited into the federal public service since April 1, 2015.

65.The evaluation found that the Department of National Defence employs good practices with respect to informing hiring managers of the Veterans Hiring Act provisions and how to apply them in appointment processes. The Assistant Deputy Minister (Human Resources Civilian) maintains an online training presentation, and has included key information on the human resources section of the Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces Intranet site. The evaluation also found that Public Services and Procurement Canada and the Correctional Service of Canada are developing strategies for informing hiring managers.

66.In interviews, Veterans Affairs Canada service delivery employees and survey respondents highlighted suggestions that could be implemented by hiring managers. These included communicating information more effectively and concisely during staffing processes, as well as providing more guidance and insights for veterans to help them navigate the staffing system. A good practice in this regard is the information provided to veterans on the Canada Revenue Agency employment opportunities’ Internet site. This site is easy to navigate and provides detailed explanations to support veterans looking to work for that agency.

Staffing advisors

67.The Staffing and Non-Partisanship Survey asked staffing advisors to rank the extent to which they were sufficiently informed about changes to priority entitlements included in the Veterans Hiring Act so they could provide sound advice within their organizations. Table 4 provides a list of the organizations whose staffing advisors ranked themselves the highest in this regard. In general, staffing advisors ranked themselves relatively high in terms of their understanding, with all departments and agencies having a rating of great and moderate above 80%.

|

Department |

Great extent |

Moderate extent |

Total great plus moderate |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Veterans Affairs Canada |

76% |

21% |

97% |

|

Department of Justice Canada |

67% |

29% |

96% |

|

Correctional Services Canada |

65% |

30% |

95% |

|

Department of Fisheries and Oceans |

68% |

26% |

94% |

|

Department of National Defence |

54% |

38% |

92% |

|

Crown Indigenous Relations and Indigenous Services |

64% |

27% |

91% |

|

Statistics Canada |

69% |

19% |

88% |

|

Global Affairs Canada |

65% |

23% |

88% |

|

Natural Resources Canada |

73% |

13% |

86% |

|

Environment and Climate Change |

64% |

18% |

82% |

68.Staffing advisors have a positive view of their understanding of the Veterans Hiring Act provisions. Since they support hiring managers, this is a strength that could be built upon to improve veteran hiring across the federal public service.

69.The evaluation found that Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada have partnered with Veterans Affairs Canada and offered a session for their departmental human resources staffing community in November 2019 on the recruitment of veterans. The session included a short presentation by a current veteran who shared their experience and some of the barriers they encountered in appointment processes. Sessions for hiring managers in both departments are going to be offered in early 2020 via WebEx on the same subject.

70.In interviews with a sample of staffing advisors from 4 departments, the evaluation team was informed that the part of the staffing process that involves identifying and screening persons with a priority entitlement could be strengthened. As the priority clearance process is generally managed by staffing advisors, hiring managers do not have the opportunity to see the résumés of priority persons unless they respond to a priority request. Those we spoke to said that it may be time for the Public Service Commission to review this process and develop profiles of individuals in the Priority Information Management System to showcase to managers, since in many cases, persons with priority entitlements are overwhelmed with job advertisements and do not respond to staffing advisors.

71.Overall, the Staffing and Non-Partisanship Survey results align with the findings of the June 2019 report of the Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates on veterans hiring, which stated that “a number of witnesses [..] highlighted that […] some public service managers and human resource specialists do not understand the priority hiring process for veteransFootnote 8.” The fact that hiring managers self-rated their knowledge of the Veterans Hiring Act provisions at 54% (great and moderate) highlights that more work needs to be done to educate them. While some work has started in a number of departments and agencies, an overall strategy would benefit the entire system.

4.3 Hiring veterans through the provisions established in the Veterans Hiring Act

This section provides information on veteran hiring through the Veterans Hiring Act provisions since July 1, 2015.

Preference and mobility

72.Preference. Veterans with a minimum of 3 years of service who were honourably released within the past 5 years have preference for appointment in job opportunities advertised to the public. If found qualified, a veteran must be appointed ahead of other candidates (if there are no persons with a priority entitlement qualified for the position). The preference provision can be activated up to 5 years after a Canadian Armed Forces member releases. A veteran who is already indeterminately employed in the federal public service cannot be considered as a preference in appointment processes.

73.Mobility. The mobility provision provides access to advertised internal appointment processes for veterans and eligible Canadian Armed Forces members who are not indeterminately (permanently) employed in the federal public service. Canadian Armed Forces members who have served a minimum of 3 years can apply to all internally advertised processes. The provision also applies to veterans who have a minimum of 3 years of service and were honourably released within the past 5 years.

74.Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans eligible to be considered for appointment through the mobility provision when they apply to an advertised internal process remain eligible even if their status changes during the process. Veterans eligible for mobility can activate it at any time within 5 years from their release date. Eligibility ends upon indeterminate appointment to the federal public service or, for veterans, 5 years after they have been released, whichever comes first.

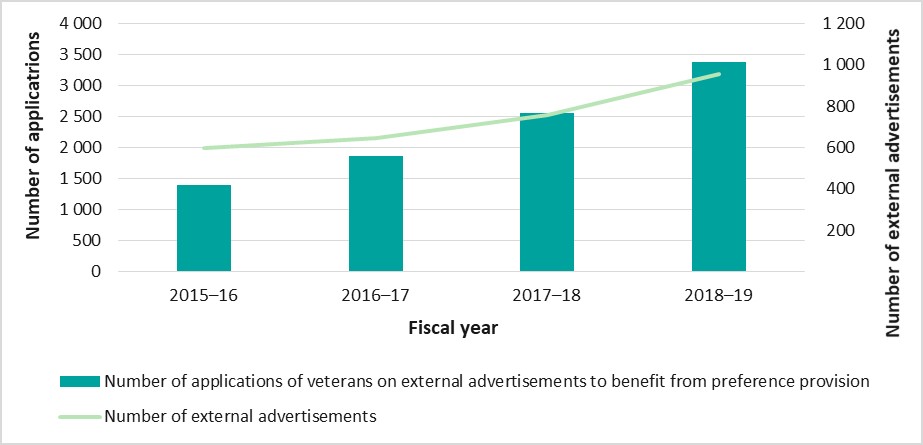

Preference

75.To examine the extent to which veterans understand the preference provision, the evaluation compared the number of applications from veterans exercising this provision with the number of federal public service external advertisements. For the period from 2015–16 to 2017–18, both the number of external advertisements and the number of applicants who exercised this provision increased by 21% and 45% respectively (see Graph 18). The number of applications from veterans to external advertised processes increased from 1 400 in 2015–16 to 3 387 in 2018–19. This may indicate that veterans are becoming more aware of the preference provision and how it works.

Text version

|

Number of applications |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|

Number of applications of veterans on external advertisements to benefit from preference provision |

1400 |

1858 |

2557 |

3387 |

|

Number of external advertisements |

596 |

645 |

758 |

957 |

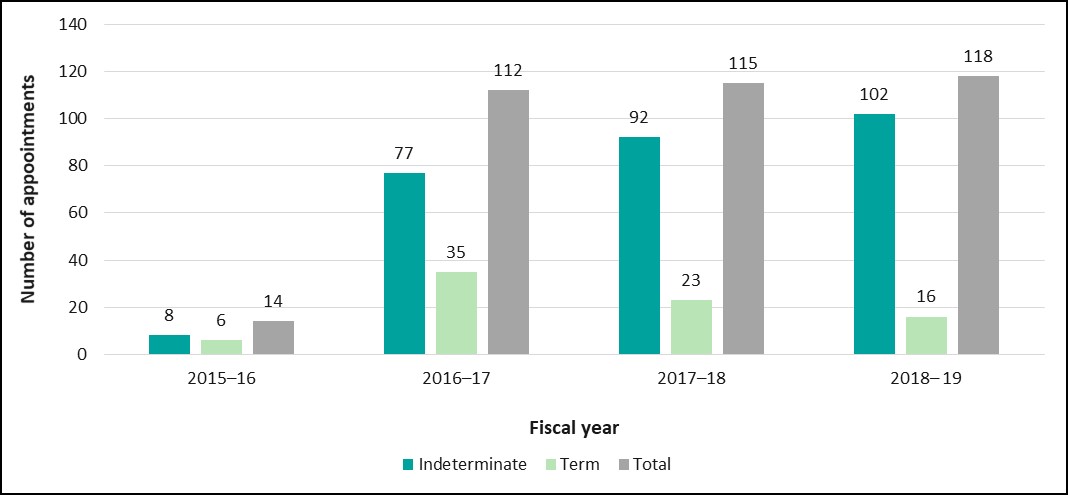

76.From 2016–17 to 2018–19, there has been a relatively stable number of preference hires, averaging 115 people per year — most for permanent federal public service positions (see Graph 19).

Text version

|

Preference |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|

Indeterminate |

8 |

77 |

92 |

102 |

|

Term |

6 |

35 |

23 |

16 |

|

Total |

14 |

112 |

115 |

118 |

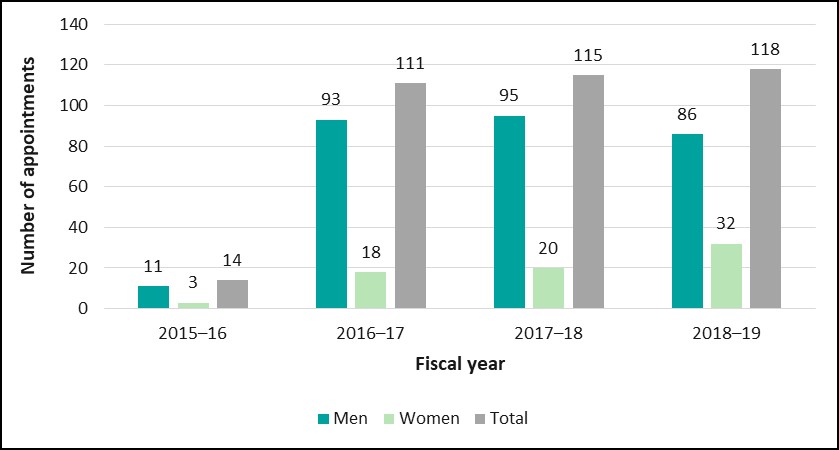

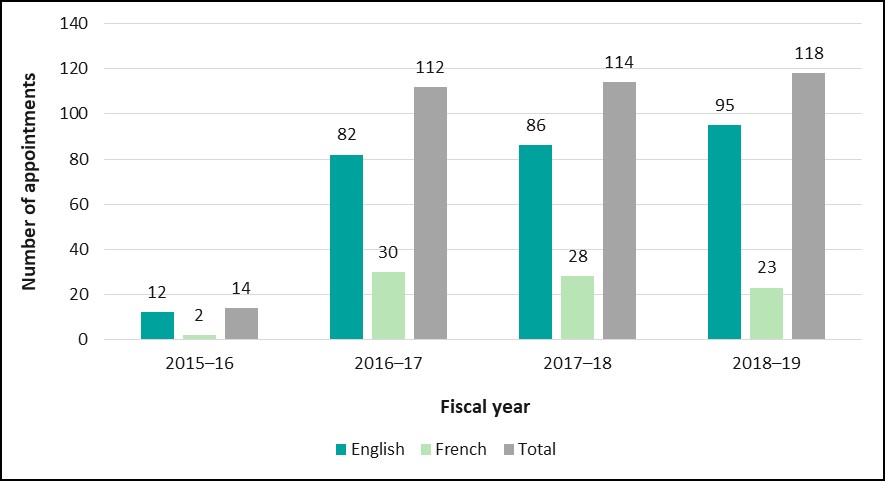

77.The evaluation found that women accounted for approximately 20% of veterans hired through the preference provision (see Graph 20). This compares to the fact that women make up 15.7% of total Canadian Armed Forces members and reservists (see Table 5) Footnote 9. Of the 80 individuals who were hired as term employees, 25% were women. As well, 77% of hires were Anglophone, and 23% of hires were Francophone (see Graph 21).

Text version

|

Preference |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|

Men |

11 |

93 |

95 |

86 |

|

Women |

3 |

18 |

20 |

32 |

|

Total |

14 |

111 |

115 |

118 |

Text version

|

Preference |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|

English |

12 |

82 |

86 |

95 |

|

French |

2 |

30 |

28 |

23 |

|

Total |

14 |

112 |

114 |

118 |

|

% Women |

% Men |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Canadian Armed Forces demographics |

15.7% |

85% |

|

Preference - Indeterminate positions |

19% |

81% |

|

Preference - Term positions |

25% |

75% |

78.The top 8 departments and agencies that hired individuals through the preference provision represented 82% of all hires in that category (see Table 6).

|

Preference - top 8 departments |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

Total |

% of total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

National Defence |

8 |

52 |

61 |

59 |

180 |

50% |

|

Employment and Social Development Canada |

0 |

8 |

10 |

10 |

28 |

8% |

|

Fisheries and Oceans Canada |

0 |

6 |

7 |

10 |

23 |

6% |

|

Veterans Affairs Canada |

1 |

12 |

3 |

2 |

18 |

5% |

|

Correctional Service Canada |

1 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

13 |

4% |

|

Statistics Canada |

3 |

5 |

0 |

4 |

12 |

3% |

|

Public Services and Procurement Canada |

0 |

6 |

5 |

1 |

12 |

3% |

|

Shared Services Canada |

0 |

1 |

3 |

6 |

10 |

3% |

|

33 departments and agencies |

1 |

18 |

22 |

22 |

63 |

18% |

|

Total |

14 |

112 |

115 |

118 |

359 |

100% |

79.The Department of National Defence hired 50% of those who found work through the preference provision. As well, Employment and Social Development Canada has consistently hired approximately 10 people per year through the preference provision, while Veterans Affairs Canada hired 2 in 2018–19, down from 12 in 2016–17.

80.The use of the preference provision is more common in the regions than in the National Capital Region. The preference provision appears to be a means for veterans who live outside of the National Capital Region to be hired into the federal public service. Approximately 75% of all hires through the preference provision were for positions outside of the National Capital Region (see Table 7). As Department of National Defence is the main employer, the preference provision could be a way for Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces installations across the country to benefit from the experience and expertise that veterans have to offer the federal public service in the regions.

|

Preference - by province/territory |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

Total |

% of total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

National Capital Region (NCR) |

0 |

38 |

25 |

27 |

90 |

25% |

|

British Columbia |

3 |

18 |

17 |

19 |

57 |

16% |

|

Quebec (except NCR) |

1 |

13 |

15 |

13 |

42 |

12% |

|

Ontario (except NCR) |

1 |

7 |

12 |

22 |

42 |

12% |

|

Nova Scotia |

1 |

8 |

12 |

18 |

39 |

11% |

|

Alberta |

4 |

9 |

10 |

7 |

30 |

8% |

|

New Brunswick |

0 |

13 |

12 |

4 |

29 |

8% |

|

Newfoundland and Labrador |

2 |

1 |

4 |

3 |

10 |

3% |

|

Manitoba |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

2% |

|

Saskatchewan |

0 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

1% |

|

Prince Edward Island |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

1% |

|

Northwest Territories |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1% |

|

Unknown |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0% |

|

Yukon |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0% |

|

Nunavut |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0% |

|

Total |

14 |

112 |

115 |

118 |

359 |

100% |

81.Finally, the evaluation obtained data on employment by federal public service occupational group. Table 8 demonstrates that 302 (roughly 35%) of those hired through the preference and mobility provision were for administration (AS) and clerical positions (CR); and 23 (2.6 %) veterans were hired for positions in the executive cadre.

|

Occupational groups |

Mobility |

Preference |

Total |

% of total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Administrative Services |

172 |

39 |

211 |

24.30% |

|

Clerical and Regulatory |

28 |

63 |

91 |

10.40% |

|

Engineering and Scientific |

30 |

35 |

65 |

7.50% |

|

Program Administration |

28 |

28 |

56 |

6.45% |

|

Computer Systems |

29 |

22 |

51 |

5.80% |

|

General Technical |

32 |

11 |

43 |

5.00% |

|

General Services - Stores |

9 |

24 |

33 |

3.80% |

|

Economics / Social Sciences |

23 |

7 |

30 |

3.40% |

|

Executive |

19 |

4 |

23 |

2.60% |

|

Welfare Programs |

2 |

13 |

15 |

1.73% |

|

53 other categories |

137 |

113 |

250 |

28.80% |

|

Total |

509 |

359 |

868 |

100% |

82.In terms of hiring managers applying the preference provision, the Public Service Commission’s 2018 System-Wide Staffing Audit revealed that the use of the provision to hire eligible veterans was not respected in 23.8% of the sample of staffing files reviewed. Some survey respondents also indicated that the preference provision might not have been respected in processes they were a part of. This demonstrates a need for hiring managers to have a better understanding of how to apply the 3 provisions.

Mobility provision

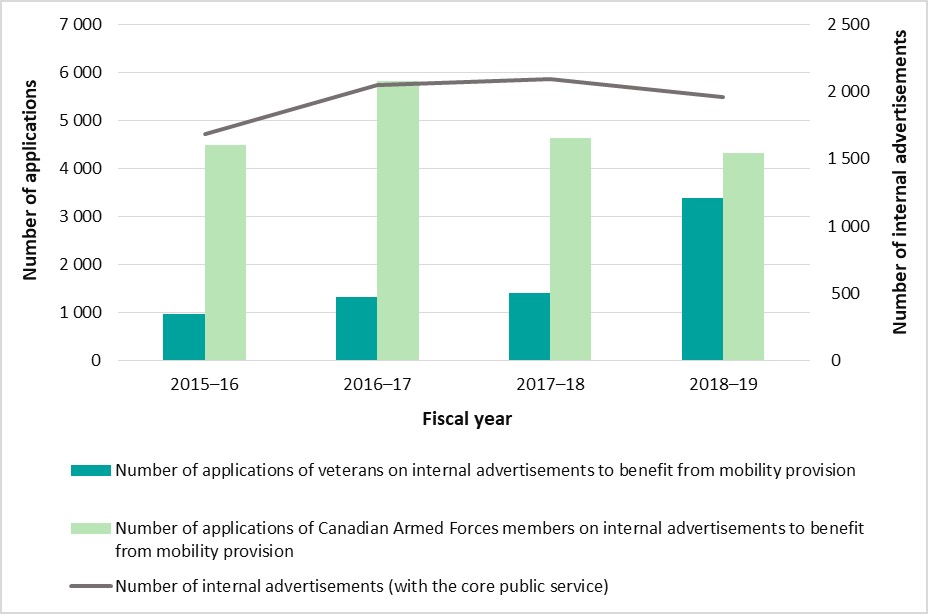

83.Eligible Canadian Armed Forces members’ and veterans’ awareness of the mobility provision was reviewed by analyzing staffing action data where this provision was used by hiring managers. Graph 22 illustrates that between 2015–16 and 2018–19, applications from veterans using this provision increased 3-fold, while the percentage of Canadian Armed Forces member applicants was constant during the period. As well, internal advertisements increased by 16%.

Preference to veterans and Canadian citizens

In accordance with Section 39 (1) of the Public Service Employment Act, in an advertised external appointment process, any of the following people who meet the essential qualifications referred should be appointed ahead of other candidates, in the following order:

- a person in receipt of a pension by reason of war service

- a veteran or a survivor of a veteran

- a Canadian citizen, within the meaning of the Citizenship Act, in any case where a person who is not a Canadian citizen is also a candidate

The System-Wide Staffing Audit, published in 2018, found that the order of preference was applied in 18 sampled external advertised appointment processes, where, in addition to Canadian citizens, there were veterans or non-Canadians who met the essential qualifications. Of these, the order of preference was respected in 13 appointment processes (61.9%) but was not respected in 5 appointment processes (23.8%), where another qualified candidate was appointed ahead of an eligible veteran or Canadian citizen.

Text version

|

Mobility applicants |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|

Number of applications of veterans on internal advertisements to benefit from mobility provision |

976 |

1324 |

1403 |

3387 |

|

Number of applications of Canadian Armed Forces members on internal advertisements to benefit from mobility provision |

4486 |

5828 |

4638 |

4317 |

|

Number of internal advertisements (with the core public service) |

1685 |

2051 |

2090 |

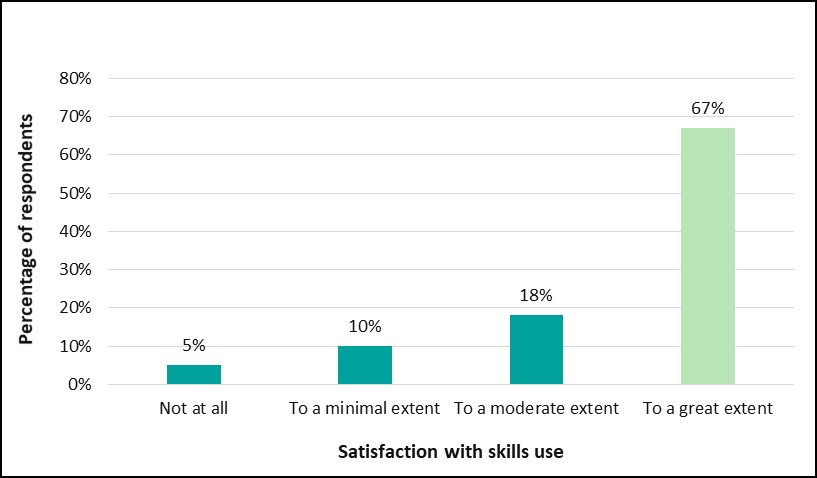

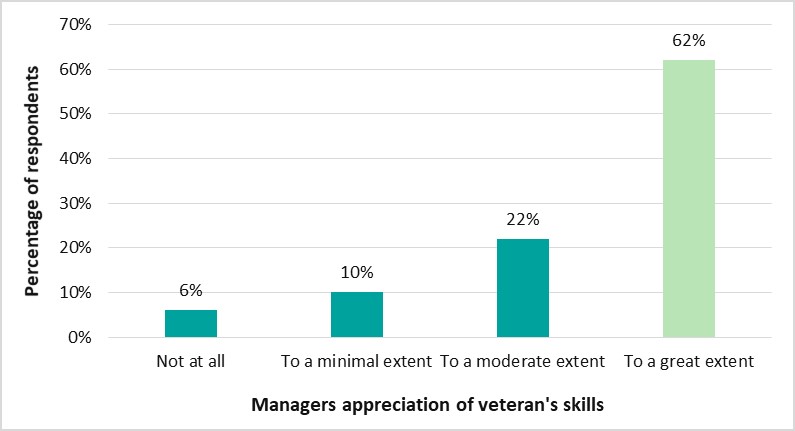

1957 |