Employment Equity Promotion Rate Study - Three-Year Update

Table of Contents

Key terms used in this report

“federal public service”

- departments and agencies that fall under the jurisdiction of the Public Service Employment Act

“employees” or “public servants”

- indeterminate public servants who are employed in departments and agencies that fall under the jurisdiction of the Public Service Employment Act

“employment equity groups”

- as defined in the Employment Equity Act, the 4 employment equity groups are women, members of visible minorities, Aboriginal people (referred to as Indigenous Peoples throughout this study) and persons with disabilities

“counterparts” and “reference group”

- a group of employees not belonging to the employment equity group being considered

- the counterparts for women are men, and the counterparts for each of the other 3 groups are people who did not self-identify as belonging to that group; for example, the counterparts for members of visible minorities and their subgroups are people who did not self-identify as a member of visible minorities

Executive summary

This update of the Employment Equity Promotion Rate StudyFootnote 1 was undertaken as part of the Public Service Commission of Canada (PSC)’s oversight mandate to assess the integrity of the public service staffing system and under its responsibilities as outlined in the Employment Equity Act. The main purpose of the update was to integrate visible minority subgroups into the analysis and to reflect the most recent employment equity data. The key findings from the analysis can be summarized as follows:

First, since the original study, the relative promotion rates of visible minority public servants steadily increased. Most visible minority subgroups experienced this increase in relative promotion rates. For example, Black public servants went from a negative relative promotion rate (‑4.8%) in the original study period (2005 to 2018) to a statistically equivalent relative promotion rate in the latest study period (2008 to 2021) (see Table 1 and Table 2).

Second, persons with disabilities experienced a decline in their relative promotion rates over the same reference periods. The relative promotion rate of persons with disabilities declined from ‑7.9% to ‑12.6% between the original study period (2005 to 2018) and the most recent analysis period (2008 to 2021) (see Table 1).

Third, women in the Scientific and Professional occupational category are still experiencing challenges when compared to men. In the most recent study period (2008 to 2021), women holding a job in that occupational category still had lower relative promotion rates (-3.1%) (see Table 6).

Introduction

The Public Service Commission of Canada (PSC) is responsible for promoting and safeguarding a merit-based, representative and non-partisan federal public service. As part of its oversight role, it undertakes investigations as well as audit and research activities to assess the integrity of the public service staffing system and its performance against intended outcomes. This study is part of these oversight initiatives and assesses the success of employment equity group members (women, visible minorities, Indigenous Peoples, and persons with disabilities) in seeking and obtaining promotions, relative to their counterparts.

The study expands the analysis of the original PSC’s 2019 Employment Equity Promotion Rate Study to include employment equity visible minority subgroups. This analysis was conducted over 4 time periods to monitor if the relative promotion rates improved (or not) throughout the examined period. Those 4 periods are 2005 to 2018, 2006 to 2019, 2007 to 2020, and 2008 to 2021.

The statistical methodology used is explained in Appendix A. The study is presented in 5 sections: relative promotion rates of government-wide results, occupational categories, Executives, employment equity groups’ intersectionalities, and the propensity to apply to a job advertisement.

Methodological notes

The results in this paper are reported as relative promotion rates, where a relative promotion rate above 0 indicates a higher promotion rate for a given employment equity group than its counterpart. Conversely, a negative relative promotion rate indicates a lower promotion rate for an employment equity group compared to its counterpart. Results presented in the tables may be accompanied by asterisks, which indicate the statistical significance of the finding. The absence of asterisks means no statistical significance, one asterisk means a statistical significance at the 5% level, and 2 asterisks denote a statistical difference at the 1% level.

Data

The dataset used for this analysis is derived from 2 data sources. The first data source, PSC’s Job-Based Analytical Information System, contains transactional data gathered from the government’s pay system since April 1990. This data source was used to identify promotions and most explanatory variables used in the analysis, such as region and occupational category. The second data source, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Employment Equity Data Bank, contains employment equity self-identification information provided by employees.

For the determination of employment equity status, women are identified through the federal government pay system. The other 3 groups (members of visible minorities, persons with disabilities, and Indigenous Peoples) and the visible minority subgroups are identified through the Employment Equity Data Bank. A retrospective approach was taken for members of visible minorities and Indigenous Peoples. That is, if a public servant self-identified as such after the year of hiring, then that self-identification status was used for the public servant throughout the entire study period. A similar retrospective approach could not be taken for persons with disabilities since not all disabilities may have been present before employees self-identified . Our numbers show that 59% of persons with disabilities self-identified within the first year of service. Also, 81% self-identified by the end of the fourth year of service, which is close to the average time to first promotion for persons with disabilities. Therefore, the majority of persons with disabilities in this study self-identified early into their career.

Findings

Public service-wide results

Table 1 below presents the relative promotion rates for the 4 employment equity groups from the original study (2005 to 2018) and the updated results for each of the 3 subsequent periods studied (2006 to 2019, 2007 to 2020 and 2008 to 2021). The current study also includes results for visible minority subgroups. Table 1 includes results for the largest subgroup (Black public servants) while numbers for all other subgroups are reported in Table 2.

The most notable results from Table 1 are the following:

- Women’s relative promotion rates decreased over the 4 periods but remained higher than men.

- The relative promotion rates of members visible minorities improved throughout the 4 periods. They increased from an equivalent rate for the 2005 to 2018 period to a relative promotion rate of 4.4% for the 2008 to 2021 period.

- A positive trend is also observed for Black public servants. During the 2005 to 2018 period, public servants who identified as Black had lower relative promotion rates (‑4.8%). For the period ending in 2021, Black public servants had relative promotion rates that were statistically equivalent.

- Indigenous Peoples continue to have lower relative promotion rates and have remained consistent across the various time periods in our study (‑7.5% for the most recent period ending in 2021).

- Persons with disabilities had lower relative promotion rates in each of the 4 time periods. In addition, their relative promotion rate declined since the original study (from ‑7.9% to ‑12.6% for the periods ending in 2018 and 2021, respectively).

| Employment equity groups | Original study 2005 to 2018 |

2006 to 2019 | 2007 to 2020 | 2008 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 4.3%** | 3.2%** | 2.8%** | 2.8%** |

| Members of visible minorities | 0.6% | 1.8% | 2.9%** | 4.4%** |

| Black | -4.8%** | -4.2%** | -3.1%* | -1.1% |

| Indigenous Peoples | -7.5%** | -8.4%** | -8.5%** | -7.5%** |

| Persons with disabilities | -7.9%** | -9.4%** | -11.2%** | -12.6%** |

* Stands for statistical significance at 5% level; ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level

Results by occupational categories

The original study explored the relative promotion rates of employment equity group members by occupational categories. In this section, the analysis was updated with results as of 2021 and including visible minorities’ subgroups. The analysis below focuses on key findings; however, complete results on all 5 occupational categories are presented in Appendix C.

Findings

In every period of our study (see Tables 2 to 6), women have consistently higher relative promotion rates in the Administrative Support, and Administrative and Foreign Service occupational categories, but have considerably lower relative promotion rates in the Scientific and Professional and Technical occupational categories. In the most recent period of our study (2008 to 2021), women had a higher relative promotion rate in the Operational occupational category.

Indigenous Peoples and persons with disabilities have had lower relative promotion rates in the Administrative Support, Administrative and Foreign Services, and the Scientific and Professional categories throughout the 4 periods. Persons with disabilities had substantially higher relative promotion rates in the Operational Category.

Members of visible minorities had, for the most part, relative promotion rates that were comparable, or higher, across all occupational categories, with the highest relative promotion rate differential observed in the Administrative Support, Administrative and Foreign Service and Operational occupational categories.

Finally, for members of visible minorities subgroups, Non-White West Asian, North African or Arab employees had a higher relative promotion rate in the Administrative Support, Administrative and Foreign Service and technical occupational categories throughout the 4 periods. Black and Filipino public servants had a lower relative promotion rate in the Scientific occupational category for most periods of the study. In the period ending in 2021, all visible minority subgroups in the Administrative Support Category had equivalent or higher relative promotion rates than their counterpart (see Table 3).

Relative promotion rates within the Executive Category, from feeder groups, and to the Executive Category

As in the original study, this report also contains updated results on relative promotion rates of employment equity group members:

- within the Executive (EX) Group

- from feeder groups (EX-minus-1 level) to EX and EX-equivalent positions

- from feeder groups (EX-minus-1 level) to the (EX) group only

This section presents key findings on the Executive Group. Detailed results can be found in tables 8, 9 and 10 in Appendix D.

Within the Executive (EX) Group

Within the Executive Group, visible minority public servants observed lower relative promotion rates for the periods ending in 2018 (‑15.6%) and 2019 (‑14.7%). Their relative promotion rates increased over the next periods to statistically equivalent levels for the periods ending in 2020 and 2021 (see Table 8).

It is worth mentioning that the low number of observations for Indigenous executives, executives with disabilities, and certain visible minority subgroups impact the statistical significance of the results. Even so, large differences, whether statistically significant or not, deserve attention and should be explored further.

From the feeder groups (EX-minus-1 level) to EX and EX-equivalent positions

For the period ending in 2021, all employment equity groups, including visible minority subgroups, showed statistically equivalent relative promotion rates from feeder groups to EX and EX-equivalent positions.

From the feeder groups (EX-minus-1 level) to the EX group only

When the analysis is restricted to promotions from the feeder groups to the Executive Group, the original study concluded that members of visible minorities displayed substantially lower relative rates of promotion (-25.7%) and women showed a higher relative promotion rate (15.6%). This observation remained for subsequent periods except for indigenous Peoples. For the period ending in 2021, Indigenous Peoples had statistically higher (21.7%) relative promotion rates (see Table 10).

Disaggregating visible minority data into subgroups shows that the Chinese subgroup consistently had lower relative promotion rates from the EX-minus-1 level to solely the EX group (‑53.5%, ‑48.1%, ‑50.8%, ‑54.4% for the 4 periods considered, respectively). All other visible minority subgroups had no statistically significant differences in their relative promotion rates.

Intersectionality

Intersectionality refers to the compounding effect of belonging to more than one employment equity group. This section presents the most significant findings from our intersectionality analysis. Tables 11 and 12 in Appendix E present the results for all modelled interactions.

Interaction between gender and identifying as a Black public servant

As presented in our main result (see Table 1), women tend to have a higher relative promotion rate (2.8% for the 2008 to 2021 period). However, the results presented in Table 11a and 11b show that the compounding effect of being both a Black public servant and a woman significantly impacts the chances of promotion. More specifically:

- Black public servant women have lower relative promotion rates (-5.2%) than women who did not identify as a visible minority

- Black public servant women have lower relative promotion rates (-7.0%) as compared to Black public servant men

Other interactions

This study also measured interactions between other factors and employment equity status. An interesting interaction relates to gender and geographical location. Table 12 shows that the relative promotion rates of public servants in the National Capital Region were much higher than public servants outside the National Capital Region (63.1%). When considering the interaction with gender, we see that:

- the relative promotion rate for women compared to men was higher (8.3%) in the National Capital Region as compared to outside the region (-6.0%)

- the relative promotion rate of women in the National Capital Region compared to women outside the region (72.2%) was higher than the same comparison for men (49.5%).

Finally, note that the relative promotion rates of members of visible minorities and Indigenous Peoples, compared to their respective counterparts, were also higher in the National Capital Region than outside the region (as reported above for women). Conversely, persons with disabilities continue to have significantly lower relative promotion rates in the National Capital Region versus outside the region. (See Table 12.)

Representation of employment equity group members as applicants, in the federal public service, and as a share of promotions

Relative promotion rates depend on both the success of employment equity groups during the staffing process and how likely members of the groups are to apply for opportunities. That is, an employment equity group or sub-group may be under-promoted because it encounters barriers at the application stage, during the staffing process, or both.

Table 13 Footnote 2 provides representation numbers of all employment equity groups, including visible minority subgroups as applicants, compared to their representation share in the federal public service for the fiscal years 2017–18 to 2020–21. The main results are:

- The representation of women applicants to job advertisements and their share of promotions continue to surpass their representation in the federal public service.

- Members of visible minorities’ representation as applicants continues to be larger than both their representation in the general population and their share of promotions. Among visible minority subgroups, this was also notable for public servants who identified as Black, South Asian/ East Indians and Non-White West Asian, North African or Arabs.

- Indigenous Peoples had a lower representation as applicants than their representation in the general population over the 4 fiscal years. However, their representation in promotions continues to be higher than their representation as applicants.

- Over the 4 years, persons with disabilities had equivalent or higher representation as applicants compared to their share in promotions. However, both were lower than their representation in the federal public service.

Conclusion

The main objective of this study was to identify potential gaps in the relative promotion rates of employment equity groups and subgroups, and to assess progress in that regard over 4 comparable periods between 2005 and 2021. This study relied on the same survival analysis techniques as the original 2019 study.

Compared to the original 2019 study, this update reveals a statistically significant increase in the relative promotion rates of visible minority public servants over the last 3 study periods. This increasing trend is also clearly observed in the data for the Black public servants subgroup, who now have statistically equivalent relative promotion rates.

Finally, this update showed that the relatively lower promotion rate of persons with disabilities observed in 2019 has declined further over the last 3 study periods. This observation aligns with the results for persons with disabilities from the PSC’s recent Audit of Employment Equity Representation in Recruitment with respect to potential barriers in the application process.

Employment equity is a shared responsibility between the PSC, the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer and federal departments and agencies. With this in mind, we will continue to work with key stakeholders as well as members of the employment equity community to identify and address barriers to career progression.

Appendix A: Methodology

In this paper, we relied on a Cox proportional hazards survival model to investigate the effect several variables have on the time to the first promotion and between 2 consecutive promotions for Canadian federal public servants. This type of model is generally used to look at the relationship between the “survival” of a subject and various explanatory variables. This type of analysis originates from research in the field of health sciences, where the impact of various treatments for life-threatening conditions on the survival of patients are being compared. Due to technical similarities in experiment design and features of datasets, survival analysis has known considerable popularity beyond the narrow scope of health sciences, and it has been successfully used over a wide spectrum of research fields. It is particularly useful for social research aiming at following a subject until a certain event of interest occurs and discerning the factors that predict the duration to that particular event. In our case, the event of interest is the promotion of a federal public servant. Our model allowed us to compare the survival times to promotion of members of an employment equity group to their counterparts.

Survival analysis has also been widely used in econometric modelling with respect to labour market analysis such as employee retention, career advancement, unemployment spells, and product life expectancy. Allison Milner et al. (2018) (English only) used survival analysis to identify employment characteristics associated with exiting work and assess if these were different for persons with disabilities versus those without disabilities. A paper by Daniela-Emanuela Danacica and Ana-Gabriela Babucea (2010) (English only) presented an application of survival analysis on the duration of unemployment using exogenous variables such as gender and age. More closely related to our work, Janet M. Box-Steffensmeier, Raphael C. Cunha, et al. (2015) (English only) used survival analysis to look at the impact of gender on the time of departure and time to promotion in academia.

Unlike logistic regression, which calculates the probability of an event happening based on explanatory variables, the response variable hi(t) in Cox Proportional Hazard models is the hazard function at a given time t. Therefore, an underpinning assumption of our analysis is that all employees, regardless of employment equity status, are eligible to obtain a promotion at any given time. However, federal public servants are only eligible to obtain a promotion if they are active in the pursuit of promotion opportunities. Our analysis of the propensities of the various employment equity groups to apply to staffing processes attempts to provide a better picture of the factors that may be at play behind promotion rate differentials across employment equity groups.

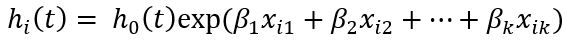

The model used in this analysis takes the form of

Text version

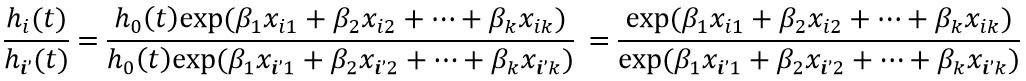

The function h underscript i at time t equals the function h underscript 0 at time t multiplied by the exponential function of the linear function of k variables x with their corresponding parameters β for each observation i.where h stands for the hazard function, x refers to a set of explanatory variables listed below and ranging from 1 to k, depending on each specification of the model, β represents the coefficients of these variables, the argument t stands for time, and the subscript i refers to a specific transaction (that is, a promotion or a waiting period leading to a separation) being described by the model. Here, h0(t) is the baseline hazard as hi(t) = h0(t) when all x’s are equal to zero. The baseline hazard is unspecified and can take any form. If we consider 2 different observation (i) and (i’), the hazard ratio given by

Text version

The fraction of the function h underscript i at time t to the function h underscript i prime (i’) at time t equals the fraction of the function h underscript 0 at time t multiplied by the exponential function of the linear function of k variables x with their corresponding parameters β for each observation i as the numerator and the function h underscript 0 at time t multiplied by the exponential function of the linear function of k variables x with their corresponding parameters β for each observation i prime (i’) as the denominator. Simplifying the equation by the common multiplier of the function h underscript 0 at time t, we get the fraction of the exponential function of the linear function of k variables x with their corresponding parameters β for each observation i as the numerator and the exponential function of the linear function of k variables x with their corresponding parameters β for each observation i prime (i’) as the denominator.is independent of time (t) and proportional across time. Not having to make arbitrary, and possibly counterfactual, assumptions about the form of the baseline hazard is a significant advantage of using Cox’s specification. Footnote 3

Observations

Due to a transition in data capture in April 1991, the dataset only contains employees hired into the public service after April 1, 1991, who are followed until their separation/retirement or until March 31, 2021. The rationale for the choice of the starting date is that, prior to the April 1991 transition, the data does not differentiate between a promotion and other types of staffing actions (such as new hires).

The time to promotion is calculated from the time of hire to the time of the first promotion, or the time between any 2 consecutive promotions. The datasets consist of the following: 1. observations, 2 number of indeterminate employees, 3. waiting periods to promotion and 4. interrupted waiting periods. Interrupted waiting periods are periods of time (either since last promotion, or since hiring in cases where there was no promotion) which were interrupted either by a separation or by the end of the period under observation.

| Time period | Total observations | Indeterminate employees | Waiting periods | Interrupted waiting periods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 to 2018 | 409 468 | 230 310 | 172 125 | 237 343 |

| 2006 to 2019 | 431 970 | 242 097 | 182 708 | 249 262 |

| 2007 to 2020 | 450 428 | 252 487 | 190 639 | 259 789 |

| 2008 to 2021 | 464 026 | 263 103 | 193 695 | 270 331 |

The following variables were used in our models:

- Time: a continuous dependent variable, defined as length of time (in years) from being hired into the federal public service to first promotion, the length of time (in years) between 2 consecutive promotions or length of time with no promotion.

- Promotion: the event indicator, equal to 1 if the employee obtained a promotion; 0 otherwise.

- Women: a dummy variable, equal to 1 if indicated as such in the pay system; 0 otherwise.

- Visible minority subgroups: a dummy variable, equal to 1 if self-identified as such in the employment equity database by the end of the study period; 0 otherwise.

- Indigenous Peoples: a dummy variable, equal to 1 if self-identified as such in the employment equity database by the end of the study period; 0 otherwise.

- Persons with disabilities: a dummy variable, equal to 1 if self-identified as such in the employment equity database by the end of the fiscal year the promotion was obtained; 0 otherwise.

- Age: a continuous variable defined as age at hire or age at previous promotion.

- Salary deciles: a dummy variable, derived from current salary of public servants who were not promoted and public servants’ salary before promotion for those who were promoted for each fiscal year. This was used as a proxy of seniority. The reference group selected was salary decile 1.

- Occupational categories: a dummy variable based on Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat definitions. The reference group selected was the Executive Group.

- First official language: dummy variable defined as 0 if Anglophone; 1 if Francophone.

- Bilingual bonus: a dummy variable based on the requirements of the position and linguistic profile of the public servant. If the position is bilingual and the public servant meets the requirements of the position, then 1; otherwise, 0. For those who did not obtain a promotion, it is based on current position; for those who were promoted, it is based on new position.

- National Capital Region: a dummy variable, defined as 1 if position is NCR; 0 otherwise. For those who did not obtain a promotion, it is based on current position; for those who were promoted, it is based on new position.

- Leave without pay: a continuous variable, defined as length of time (in years) that a public servant spent on leave without pay. For the public servants who were not promoted, it equates to all time spent on leave without pay throughout their career. For public servants who were promoted, it is the time spent on leave without pay from either the start of their career to promotion, or the time spent on leave without pay between consecutive promotions.

Models

For this paper, we analyzed 2 models for each of the 4 time periods while using a varying number of explanatory variables and interactions. Our benchmark model consisted of using all variables as listed above while considering promotions that occurred between:

- April 1, 2005, and March 31, 2018, for those hires on or after April 1, 1991

- April 1, 2006, and March 31, 2019, for those hires on or after April 1, 1992

- April 1, 2007, and March 31, 2020, for those hires on or after April 1, 1993

- April 1, 2008, and March 31, 2021, for those hires on or after April 1, 1994

The second model consisted of the benchmark model augmented with factors capturing the interactions of pairs of employment equity statuses as well as of each employment equity status with age, first official language, bilingual status, National Capital Region, and leave without pay.

For the same time periods and explanatory variables as indicated above, we also analyzed:

- promotions within the executive level (that is, an executive being promoted to a higher-level executive position)

- promotions to the executive level or executive equivalent level from employees who held positions one level below the executive level

- promotions to the executive level from employees who held positions one level below the executive level

Interpretation

Throughout the paper we refer to hazard rates as “relative promotion rates” for simplicity. This is not to be confused with other approaches, such as logistic regression for dichotomous outcomes, which calculates an event happening based on independent variables.

A hazard ratio (HR) is indeed a ratio and its interpretation in the context of this paper is as follows:

- HR = 0.5: at any particular time, half as many public servants in a given employment equity group obtained a promotion as compared to those who were not in that employment equity group.

- HR = 1: at any particular time, as many public servants in a given employment equity group obtained a promotion as compared to those who were not in that employment equity group.

- HR = 2: at any particular time, twice as many public servants in a given employment equity group obtained a promotion as compared to those who were not in that employment equity group.

The reporting of promotion rates in this paper is given as PR = HR -1. That means a (+) indicates a lower survival time (higher promotion rate) as compared to the reference groups and a (-) indicates a higher survival time (lower promotion rate) as compared to the reference groups.

Appendix B: Overall results

Employment equity groups |

Original study 2005 to 2018 |

2006 to 2019 |

2007 to 2020 |

2008 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 4.3%** | 3.2%** | 2.8%** | 2.8%** |

| Members of visible minorities | 0.6% | 1.8% | 2.9%** | 4.4%** |

| Black |

-4.8%** | -4.2%** | -3.1%* | -1.1% |

Chinese |

2.6% | 3.0%* | 2.7%* | 3.7%** |

Filipino |

-7.5%* | -7.1%* | -6.3%* | -4.8% |

Japanese |

-3.2% | -1.6% | -1.7% | -3.3% |

Korean |

6.0% | 7.2% | 7.2% | 5.1% |

Non-white Latin American |

-6.4%* | -1.8% | 0.2% | 3.1% |

Person of Mixed Origin |

5.5%** | 6.3%** | 5.3%** | 7.3%** |

South Asian / East Indian |

-0.1% | 0.5% | 2.0% | 3.5%* |

Southeast Asian |

-14.7%** | -12.7%** | -10.3%** | -6.3%* |

Non-white West Asian, North African or Arab |

10.1%** | 10.7%** | 12.1%** | 14.2%** |

Other visible minority |

4.3% | 9.1%** | 12.2%** | 12.4%** |

| Indigenous Peoples | -7.5%** | -8.4%** | -8.5%** | -7.5%** |

| Persons with disabilities | -7.9%** | -9.4%** | -11.2%** | -12.6%** |

* Stands for statistical significance at 5% level, ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level

Appendix C: Results by occupational categories

Employment equity groups |

Original study 2005 to 2018 |

2006 to 2019 |

2007 to 2020 |

2008 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 11.5%** | 8.6%** | 6.9%** | 6.0%** |

| Members of visible minorities | 6.2%** | 8.6%** | 11.1%** | 13.6%** |

| Black |

-7.6%** | -7.8%** | -4.0% | -0.4% |

Chinese |

15.7%** | 18.1%** | 18.6%** | 23.2%** |

Filipino |

12.6%* | 14.5%* | 14.9%* | 15.1%* |

Japanese |

7.8% | 14.9% | 23.5% | 38.1%* |

Korean |

21.4% | 24.6% | 31.0% | 37.8%* |

Non-white Latin American |

-7.0% | -3.0% | 2.0% | 8.6% |

Person of Mixed Origin |

10.8%* | 14.3%** | 12.3%* | 17.5%** |

South Asian / East Indian |

3.7% | 9.5%* | 9.0%* | 10.3%** |

Southeast Asian |

14.6% | 13.0% | 18.4%* | 25.4%** |

Non-white West Asian, North African or Arab |

24.3%** | 24.7%** | 28.8%** | 29.1%** |

Other visible minority |

9.1% | 16.5%** | 23.8%** | 18.5%** |

| Indigenous Peoples | -11.6%** | -13.8%** | -14.1%** | -14.7%** |

| Persons with disabilities | -20.3%** | -21.3%** | -23.7%** | -24.9%** |

* Stands for statistical significance at 5% level, ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level

Employment equity groups |

Original study 2005 to 2018 |

2006 to 2019 |

2007 to 2020 |

2008 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 10.0%** | 8.8%** | 7.7%** | 7.3%** |

| Members of visible minorities | -2.2%* | -0.1% | 1.3% | 3.5%** |

| Black |

-5.3%** | -3.9%* | -3.3% | -1.3% |

Chinese |

-1.7% | -0.2% | 1.5% | 3.2% |

Filipino |

-15.8%** | -13.4%** | -11.8%** | -7.0% |

Japanese |

-5.7% | 1.1% | -0.1% | -0.8% |

Korean |

2.2% | 3.1% | 4.2% | 3.4% |

Non-white Latin American |

-11.5% | -4.3% | -1.9% | 0.4% |

Person of Mixed Origin |

5.9% | 6.3%* | 3.5% | 5.9%* |

South Asian / East Indian |

-3.1% | -3.2% | -1.1% | 1.2% |

Southeast Asian |

-22.1%** | -18.2%** | -14.8%** | -11.7%** |

Non-white West Asian, North African or Arab |

6.8%** | 8.6%** | 10.6%** | 14%** |

Other visible minority |

2.8% | 9.6%** | 12.4%** | 13.5%** |

| Indigenous Peoples | -6.7%** | -7.1%** | -8.0%** | -7.0%** |

| Persons with disabilities | -3.3% | -6.1%** | -8.5%** | -10.6%** |

* Stands for statistical significance at 5% level, ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level

Employment equity groups |

Original study 2005 to 2018 |

2006 to 2019 |

2007 to 2020 |

2008 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 2.2% | 1.1% | 2.1% | 5.4%* |

| Members of visible minorities | 0.5% | 3.9% | 9.3%* | 11.3%** |

| Black |

-0.1% | 3.2% | 12.1% | 17.0% |

Chinese |

28.4%* | 24.7% | 22.9% | 24.2% |

Filipino |

-16.3% | -10.7% | -1.5% | 3.7% |

Japanese |

2.7% | 13.4% | 1.5% | 15.9% |

Korean |

-66.8% | -83.7%** | -69.8%** | -37.3% |

Non-white Latin American |

-7.9% | -10.7% | -7.5% | -2.9% |

Person of Mixed Origin |

3.2% | 12.2% | 11.8% | 4.9% |

South Asian / East Indian |

-12.1% | -8.8% | 4.1% | 8.3% |

Southeast Asian |

-17.0% | -5.2% | -6.6% | -12.9% |

Non-white West Asian, North African or Arab |

44.4%** | 41.8%* | 49%** | 44.1%** |

Other visible minority |

2.2% | 8.3% | 6.6% | 7.3% |

| Indigenous Peoples | -0.6% | -0.8% | 0.2% | 5.2% |

| Persons with disabilities | 28.0%** | 23.5%** | 26.1%** | 27.0%** |

* Stands for statistical significance at 5% level, ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level

Employment equity groups |

Original study 2005 to 2018 |

2006 to 2019 |

2007 to 2020 |

2008 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | -5.7%** | -5.8%** | -4.1%** | -3.1%** |

| Members of visible minorities | -0.3% | -0.9% | -1.3% | -0.5% |

| Black |

-6.1% | -6.3%* | -6.8%* | -6.4%* |

Chinese |

0.9% | 0.0% | -2.6% | -3.0% |

Filipino |

-8.9% | -17.0%* | -17.5%* | -17.3%* |

Japanese |

-10.6% | -15.9% | -17.5% | -26.4%* |

Korean |

9.8% | 10.2% | 7.9% | 1.5% |

Non-white Latin American |

-0.8% | 2.6% | 4.2% | 8.3% |

Person of Mixed Origin |

2.7% | 2.5% | 4.5% | 5.3% |

South Asian / East Indian |

0.7% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 1.0% |

Southeast Asian |

-12.5% | -14.2%* | -15.7%* | -10.3% |

Non-white West Asian, North African or Arab |

1.2% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 2.5% |

Other visible minority |

5.7% | 5.5% | 7.6% | 9.3%* |

| Indigenous Peoples | -13.3%** | -13.6%** | -11.2%** | -9.6%** |

| Persons with disabilities | -13.9%** | -13.5%** | -14.1%** | -15.1%** |

* Stands for statistical significance at 5% level, ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level

Employment equity groups |

Original study 2005 to 2018 |

2006 to 2019 |

2007 to 2020 |

2008 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | -10.6%** | -13.8%** | -16.4%** | -19.6%** |

| Members of visible minorities | 7.0%* | 5.3% | 2.7% | 0.9% |

| Black |

4.1% | -0.1% | -0.6% | 2.2% |

Chinese |

6.8% | 5.7% | 2.1% | 0.4% |

Filipino |

-11.1% | -8.6% | -11.1% | -21.5% |

Japanese |

17.3% | 17.9% | 14.1% | -1.3% |

Korean |

5.8% | 18.6% | -0.6% | -21.4% |

Non-white Latin American |

19.1% | 10.7% | -6.0% | -9.7% |

Person of Mixed Origin |

-1.7% | 0.7% | 0.5% | 2.8% |

South Asian / East Indian |

5.1% | 3.6% | 4.5% | 1.5% |

Southeast Asian |

-18.8% | -22.8% | -24.0% | -12.1% |

Non-white West Asian, North African or Arab |

65.5%** | 61.5%** | 55.5%** | 41.4%** |

Other visible minority |

-3.9% | -4.2% | -3.5% | -4.6% |

| Indigenous Peoples | 1.1% | 0.2% | 1.6% | -0.9% |

| Persons with disabilities | -2.0% | -3.2% | -5.4% | -6.9% |

* Stands for statistical significance at 5% level, ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level

Appendix D: Executive results

Employment equity groups |

Original study 2005 to 2018 |

2006 to 2019 |

2007 to 2020 |

2008 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | -2.7% | -2.5% | -2.9% | 2.1% |

| Members of visible minorities | -15.6%** | -14.7%** | -7.1% | -6.0% |

| Black |

2.6% | 3.7% | 11.7% | 10.7% |

Chinese |

-49.5%** | -54.0%** | -49.5%** | -39.2%** |

Filipino |

-56.5% | -61.2% | -61.3% | -75.1%* |

Japanese |

7.5% | -67.1% | -45.2% | -55.2% |

Korean |

-30.3% | -27.5% | -25.2% | -31.9% |

Non-white Latin American |

-11.4% | -21.3% | -7.8% | -25.4% |

Person of Mixed Origin |

-37.2%* | -37.7% | -27.4% | -19.1% |

South Asian / East Indian |

6.0% | 6.6% | 14.6% | 12.1% |

Southeast Asian |

-60.1% | -42.2% | -29.3% | -27.6% |

Non-white West Asian, North African or Arab |

-5.4% | 12.5% | 13.1% | 18.0% |

Other visible minority |

-24.0% | -31.3%** | -12.6% | -19.3% |

| Indigenous Peoples | -11.3% | -13.0% | -11.2% | -10.8% |

| Persons with disabilities | -17.7% | -12.3% | -14.3% | -11.2% |

* Stands for statistical significance at 5% level, ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level

Employment equity groups |

Original study 2005 to 2018 |

2006 to 2019 |

2007 to 2020 |

2008 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | -3.6% | -0.8% | -1.1% | 0.7% |

| Members of visible minorities | -0.5% | 0.6% | -1.7% | 2.2% |

| Black |

3.0% | 6.5% | 3.5% | 16.5% |

Chinese |

28.3%** | 23.1%* | 7.0% | -1.4% |

Filipino |

-17.2% | -16.4% | -25.2% | -40.7% |

Japanese |

-38.6% | -36.6% | -51.4% | -31.5% |

Korean |

-43.1% | -15.0% | -6.2% | -4.5% |

Non-white Latin American |

-35.8% | -23.7% | -24.3% | -4.3% |

Person of Mixed Origin |

-12.5% | -3.1% | -2.7% | 10.1% |

South Asian / East Indian |

-12.2% | -11.6% | -12.2% | -11.6% |

Southeast Asian |

-13.8% | -15.1% | -11.1% | -22.8% |

Non-white West Asian, North African or Arab |

5.8% | -2.1% | 7.7% | 20.0% |

Other visible minority |

6.4% | 1.3% | 2.7% | 2.5% |

| Indigenous Peoples | -10.6% | -6.5% | -5.8% | 6.7% |

| Persons with disabilities | 5.5% | 2.7% | -3.4% | -11.4% |

* Stands for statistical significance at 5% level, ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level

Employment equity groups |

Original study 2005 to 2018 |

2006 to 2019 |

2007 to 2020 |

2008 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 15.6%** | 18.5%** | 18.7%** | 20.8%** |

| Members of visible minorities | -25.7%** | -23.6%** | -21.7%** | -12.7%* |

| Black |

-17.8% | -13.4% | -8.4% | 8.2% |

Chinese |

-53.5%** | -48.1%** | -50.8%** | -54.4%** |

Filipino |

-23.0% | -9.4% | -22.6% | -29.7% |

Japanese |

-43.8% | -39.9% | -68.1% | -33.4% |

Korean |

-25.5% | -6.0% | -2.7% | 3.1% |

Non-white Latin American |

-32.9% | -20.2% | -23.4% | 2.7% |

Person of Mixed Origin |

-18.9% | -16.9% | -17.6% | 4.3% |

South Asian / East Indian |

-15.6% | -16.4% | -17.2% | -11.8% |

Southeast Asian |

-40.5% | -37.2% | -28.8% | -37.2% |

Non-white West Asian, North African or Arab |

-15.7% | -22.3% | -10.6% | 1.2% |

Other visible minority |

-9.1% | -11.6% | -4.7% | 6.0% |

| Indigenous Peoples | 3.5% | 9.0% | 8.8% | 21.7%* |

| Persons with disabilities | 2.4% | 6.3% | -0.1% | -6.7% |

* Stands for statistical significance at 5% level, ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level

Appendix E: Intersectionality

| Comparison made (non-conditioned relative promotion rate) |

Conditioned on men |

Conditioned on women | Conditioned on not visible minority members |

Conditioned on visible minority members | Conditioned on Black visible minority subgroup |

Conditioned on Chinese visible minority subgroup | Conditioned on Filipino visible minority subgroup | Conditioned on Japanese visible minority subgroup | Conditioned on Korean visible minority subgroup | Conditioned on Non-white Latin American visible minority subgroup |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women vs. Men (2.8%**) |

. | . | 3.4%** | 0.2% | -7.0%** | 5.1% | 11.8% | 0.4% | 25.3%* | 1.4% |

| Members of visible minorities vs. not members visible minorities (4.4%**) |

6.4%** | 3.1%** | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Black vs. not members of visible minorities |

5.5%** | -5.2%** | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Chinese vs. not members of visible minorities |

2.7% | 4.4%* | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Filipino vs. not members of visible minorities |

-9.4%* | -2.1% | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Japanese vs. not members of visible minorities |

-1.4% | -4.2% | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Korean vs. not members of visible minorities |

-7.4% | 12.2%* | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Non-white Latin American vs not members of visible minorities (3.1%) |

4.3% | 2.3% | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Person of mixed origin vs. not members of visible minorities (7.3%**) |

8.6%** | 6.5%** | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Other visible minority vs. not members of visible minorities (12.4%**) |

15.5%** | 10.5%** | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

South Asian / East Indian vs. not members of visible minorities (3.5%*) |

5.5%* | 21% | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Southeast Asian vs. not members of visible minorities (‑6.3%*) |

-9.2%* | -4.3% | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Non-white West Asian, North African or Arab vs. not members of visible minorities (14.2%**) |

17.2%** | 11.9%** | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Indigenous Peoples vs. non-Indigenous Peoples (-7.5**) |

-5.8%** | -9.0%** | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Persons with disabilities vs. persons without disabilities (-12.6%**) |

-14.8%** | -11.3%** | -12.1%** | -15.7%** | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| National Capital Region vs. outside National Capital Region (63.1%**) |

49.5%** | 72.2%** | 62.9%** | 62.7%** | 73.4%** | 59.6%** | 72.5%** | 32.9%** | 71.7%** | 72.2%** |

| French vs. English (-7.9%**) |

-4.8%** | -9.7%** | -8.6%** | -8.2%** | -0.30% | 2.20% | 16.10% | -16.50% | -15.40% | -17.2%** |

| Receive bilingual bonus vs. do not receive bilingual bonus (28.2%**) |

24.9%* | 30.1%** | 29.0%** | 28.1%** | 24.8%** | 30.6%** | 39.1%** | 17.60% | 29.9%* | 30.3%** |

Note 1: * Stands for statistical significance at 5% level, ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level

Note 2: The original interaction model included multiple 2‑way interactions for each employment equity group. This led to more than 20 000 relative promotion rates to analyze. To cite actual relative promotions rates as displayed in Table 2 meant executing the model considering only one 2‑way interaction at a time.

Note 3: Empty cells in the table are due to one of the following:

- there were no interactions to cite (for example, visible minority groups as compared to non-visible minority groups conditions on visible minority groups)

- interactions between 2 employment equity groups intuitively would lead to small numbers (for example, Indigenous Peoples and persons with disabilities)

- interactions that were not included in the main interaction model (for example, region by first official language)

| Comparison made (non-conditioned relative promotion rate) |

Conditioned on Person of mixed origin visible minority subgroup | Conditioned on other visible minority subgroup | Conditioned on South Asian / East Indian visible minority subgroup |

Conditioned on Southeast Asian visible minority subgroup | Conditioned on Non-white West Asian, North African or Arab visible minority subgroup |

Conditioned on not Indigenous Peoples |

Conditioned on Indigenous Peoples | Conditioned on persons without disabilities | Conditioned on persons with disabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women vs. Men (2.8%**) |

1.4% | -1.1% | 0.1% | 8.9% | -1.3% | 3.0%** | -0.6% | 2.6%** | 6.8%** |

| Members of visible minorities vs. not members visible minorities (4.4%**) |

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | 4.4%** | 0.3% |

Black vs. not members of visible minorities |

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Chinese vs. not members of visible minorities |

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Filipino vs. not members of visible minorities |

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Japanese vs. not members of visible minorities |

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Korean vs. not members of visible minorities |

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Non-white Latin American vs not members of visible minorities (3.1%) |

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Person of mixed origin vs. not members of visible minorities (7.3%**) |

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Other visible minority vs. not members of visible minorities (12.4%**) |

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

South Asian / East Indian vs. not members of visible minorities (3.5%*) |

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Southeast Asian vs. not members of visible minorities (‑6.3%*) |

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

Non-white West Asian, North African or Arab vs. not members of visible minorities (14.2%**) |

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Indigenous Peoples vs. non-Indigenous Peoples (-7.5**) |

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Persons with disabilities vs. persons without disabilities (-12.6%**) |

. | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| National Capital Region vs. outside National Capital Region (63.1%**) |

59.0%** | 64.1%** | 65.4%** | 55.6%** | 53.3%** | 62.7%** | 68.9%** | 63.9%** | 44.8%** |

| French vs. English (-7.9%**) |

-8.9%* | -13.3%** | -4.30% | -5.50% | 10.2%** | -8.2%** | -2.10% | -7.8%** | -9.9%** |

| Receive bilingual bonus vs. do not receive bilingual bonus (28.2%**) |

23.7%** | 23.6%** | 41.2%** | 38.1%** | 24.7%** | 28.1%** | 30.9%** | 28.5%** | 22.1%** |

Note 1: * Stands for statistical significance at 5% level, ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level.

Note 2: The original interaction model included multiple 2‑way interactions for each employment equity group. This led to more than 20 000 relative promotion rates to analyze. To cite actual relative promotions rates as displayed in Table 2 meant executing the model considering only one 2‑way interaction at a time.

Note 3: Empty cells in the table are due to one of the following:

- there were no interactions to cite (for example, visible minority groups as compared to non-visible minority groups conditions on visible minority groups)

- interactions between 2 employment equity groups intuitively would lead to small numbers (for example, Indigenous Peoples and persons with disabilities)

- interactions that were not included in the main interaction model (for example, region by first official language)

| Comparison made (non-conditioned relative promotion rate) |

Conditioned on outside National Capital Region |

Conditioned on in the National Capital Region |

Conditioned on English as first official language |

Conditioned on French as first official language | Conditioned on not receiving a bilingual bonus |

Conditioned on receiving a bilingual bonus |

Conditioned on age 25 |

Conditioned on age 35 |

Conditioned on age 45 |

Conditioned on age 55 |

Conditioned on Age 65 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women vs. men (2.8%**) |

-6.0%** | 8.3%** | 4.6%** | -0.8% | 1.4%* | 5.7%** | 0.7% | 2.9%* | 5.2%** | 7.5%** | 9.8%** |

| Members of visible minorities vs. not members of visible minorities (4.4%**) |

3.2%** | 5.1%** | 2.9%** | 9.2%** | 4.2%** | 4.8%** | 2.9%** | 4.5%** | 6.2%** | 7.9%** | 9.6%** |

Black vs. not members of visible minorities |

-5.2%* | 0.9% | -4.9%** | 3.8%* | 0.1% | -2.6% | -7.9%** | -1.3% | 5.8%** | 13.4%** | 21.5%** |

Chinese vs. not members of visible minorities |

4.9%* | 2.8% | 2.9%* | 15.0%* | 3.5%* | 5.4% | 10.3%** | 2.8%* | -4.1% | -10.6%** | -16.6%** |

Filipino vs. not members of visible minorities |

-7.0% | -1.5% | -5.6% | 20.0% | -5.5% | 2.5% | -8.4%* | -4.6% | -0.8% | 3.3% | 7.5% |

Japanese vs. not members of visible minorities |

5.7% | -13.8% | -2.9% | -11.3% | -2.0% | -10.2% | -7.2% | -3.6% | 0.2% | 4.1% | 8.2% |

Korean vs. not members of visible minorities |

1.8% | 7.3% | 5.5% | -2.3% | 4.8% | 6.1% | 10.4% | 3.3% | -3.2% | -9.4% | -15.1% |

Non-white Latin American vs. not members of visible minorities |

-0.8% | 4.8% | 5.4% | -4.5% | 2.5% | 4.1% | -1.6% | 3.1% | 8.1% | 13.4% | 18.9% |

Person of mixed origin vs. not members of visible minorities |

9.0%** | 6.4%** | 7.2%* | 6.9% | 8.8%** | 4.9% | 6.7%* | 7.3%** | 8.0%* | 8.7% | 9.4% |

Other visible minority vs. not members of visible minorities |

11.8%** | 12.7%** | 13.9%** | 8.1%* | 13.8%** | 9.7%** | 6.2%* | 13.4%** | 21.0%** | 29.2%** | 37.9%** |

South Asian / East Indian vs. not members of visible minorities |

2.6% | 4.2%* | 3.0%* | 8.0% | 2.1% | 12.4%** | 2.0% | 3.7%** | 5.4%* | 7.2% | 8.9% |

Southeast Asian vs. not members of visible minorities |

-3.5% | -7.8%* | -7.2%* | -0.0% | -8.2% | -1.2% | -5.4% | -6.7%* | -7.9% | -9.2% | -10.4% |

Non-white West Asian, North African or Arab vs. not members of visible minorities |

20.0%** | 12.9%** | 7.0%** | 29.1%** | 15.6%** | 12.4%** | 10.2%** | 14.9%** | 19.8%** | 24.8%** | 30.1%** |

| Indigenous Peoples vs. non-Indigenous Peoples (-7.5**) |

-9.7%** | -6.2%** | -9.7%** | -3.8%* | -8.5%** | -6.5%** | -12.3%** | -7.7%** | -2.8% | 2.3% | 7.6%* |

| Persons with disabilities vs. persons without disabilities (-12.6%**) |

-5.9%** | -16.8%** | -12.2%** | -14.2%** | -11.4%** | -15.8%** | -21.3%** | -14.2%** | -6.5%** | 1.8% | 11.0%** |

| Comparison made (non-conditioned relative promotion rate) |

Conditioned on outside National Capital Region |

Conditioned on in the National Capital Region |

Conditioned on English as first official language |

Conditioned on French as first official language | Conditioned on not receiving a bilingual bonus |

Conditioned on receiving a bilingual bonus |

Conditioned on age 25 |

Conditioned on age 35 |

Conditioned on age 45 |

Conditioned on age 55 |

Conditioned on Age 65 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women vs. men (2.8%**) |

-6.0%** | 8.3%** | 4.6%** | -0.8% | 1.4%* | 5.7%** | 0.7% | 2.9%* | 5.2%** | 7.5%** | 9.8%** |

| Members of visible minorities vs. not members of visible minorities (4.4%**) |

3.2%** | 5.1%** | 2.9%** | 9.2%** | 4.2%** | 4.8%** | 2.9%** | 4.5%** | 6.2%** | 7.9%** | 9.6%** |

Black vs. not members of visible minorities |

-5.2%* | 0.9% | -4.9%** | 3.8%* | 0.1% | -2.6% | -7.9%** | -1.3% | 5.8%** | 13.4%** | 21.5%** |

Chinese vs. not members of visible minorities |

4.9%* | 2.8% | 2.9%* | 15.0%* | 3.5%* | 5.4% | 10.3%** | 2.8%* | -4.1% | -10.6%** | -16.6%** |

Filipino vs. not members of visible minorities |

-7.0% | -1.5% | -5.6% | 20.0% | -5.5% | 2.5% | -8.4%* | -4.6% | -0.8% | 3.3% | 7.5% |

Japanese vs. not members of visible minorities |

5.7% | -13.8% | -2.9% | -11.3% | -2.0% | -10.2% | -7.2% | -3.6% | 0.2% | 4.1% | 8.2% |

Korean vs. not members of visible minorities |

1.8% | 7.3% | 5.5% | -2.3% | 4.8% | 6.1% | 10.4% | 3.3% | -3.2% | -9.4% | -15.1% |

Non-white Latin American vs. not members of visible minorities |

-0.8% | 4.8% | 5.4% | -4.5% | 2.5% | 4.1% | -1.6% | 3.1% | 8.1% | 13.4% | 18.9% |

Person of mixed origin vs. not members of visible minorities |

9.0%** | 6.4%** | 7.2%* | 6.9% | 8.8%** | 4.9% | 6.7%* | 7.3%** | 8.0%* | 8.7% | 9.4% |

Other visible minority vs. not members of visible minorities |

11.8%** | 12.7%** | 13.9%** | 8.1%* | 13.8%** | 9.7%** | 6.2%* | 13.4%** | 21.0%** | 29.2%** | 37.9%** |

South Asian / East Indian vs. not members of visible minorities |

2.6% | 4.2%* | 3.0%* | 8.0% | 2.1% | 12.4%** | 2.0% | 3.7%** | 5.4%* | 7.2% | 8.9% |

Southeast Asian vs. not members of visible minorities |

-3.5% | -7.8%* | -7.2%* | -0.0% | -8.2% | -1.2% | -5.4% | -6.7%* | -7.9% | -9.2% | -10.4% |

Non-white West Asian, North African or Arab vs. not members of visible minorities |

20.0%** | 12.9%** | 7.0%** | 29.1%** | 15.6%** | 12.4%** | 10.2%** | 14.9%** | 19.8%** | 24.8%** | 30.1%** |

| Indigenous Peoples vs. non-Indigenous Peoples (-7.5**) |

-9.7%** | -6.2%** | -9.7%** | -3.8%* | -8.5%** | -6.5%** | -12.3%** | -7.7%** | -2.8% | 2.3% | 7.6%* |

| Persons with disabilities vs. persons without disabilities (-12.6%**) |

-5.9%** | -16.8%** | -12.2%** | -14.2%** | -11.4%** | -15.8%** | -21.3%** | -14.2%** | -6.5%** | 1.8% | 11.0%** |

Note 1: * Stands for statistical significance at 5% level, ** stands for statistical significance at 1% level

Note 2: The original interaction model included multiple 2‑way interactions for each employment equity group. This led to more than 20 000 relative promotion rates to analyze. To cite actual relative promotions rates as displayed in Table 2 meant executing the model considering only one 2‑way interaction at a time

Appendix F: Propensity to apply

| Employment equity groups | 2017–18 population | 2017–18 applicants | 2017–18 promotions | 2018–19 population | 2018–19 applicants | 2018–19 promotions | 2019–20 population | 2019–20 applicants | 2019–20 promotions | 2020–21 population | 2020–21 applicants | 2020–21 promotions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 54.1% | 60.7% | 59.2% | 54.2% | 62.0% | 60.3% | 54.3% | 60.7% | 61.0% | 54.8% | 61.2% | 60.5% |

| Members of visible minorities | 15.4% | 21.8% | 17.1% | 16.2% | 22.7% | 18.5% | 17.1% | 24.3% | 19.6% | 18.1% | 26.7% | 20.9% |

| Black |

2.8% | 5.1% | 2.9% | 3.0% | 5.1% | 3.2% | 3.2% | 5.6% | 3.6% | 3.5% | 6.0% | 4.2% |

Chinese |

3.0% | 3.6% | 3.9% | 3.0% | 3.4% | 2.8% | 3.1% | 3.4% | 2.8% | 3.2% | 3.6% | 3.1% |

Filipino |

0.5% | 0.8% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.6% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 0.7% |

Japanese |

0.1% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

Korean |

0.2% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.3% |

Non-white Latin American |

0.6% | 1.0% | 0.7% | 0.6% | 0.9% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 1.0% | 0.9% | 0.8% | 1.1% | 0.9% |

Person of Mixed Origin |

1.2% | 1.8% | 1.4% | 1.2% | 1.4% | 1.6% | 1.3% | 1.5% | 1.6% | 1.5% | 1.6% | 1.8% |

South Asian / East Indian |

2.7% | 4.7% | 2.6% | 2.8% | 4.7% | 2.8% | 2.9% | 4.9% | 3.1% | 3.2% | 5.8% | 3.3% |

Southeast Asian |

0.7% | 1.0% | 0.6% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.9% | 0.9% |

Non-white West Asian, North African or Arab |

1.7% | 3.3% | 2.4% | 1.8% | 3.2% | 2.3% | 1.9% | 3.6% | 2.7% | 2.1% | 4.0% | 2.9% |

Other visible minority |

2.0% | 0.9% | 2.6% | 2.2% | 0.9% | 3.2% | 2.3% | 1.0% | 3.2% | 2.1% | 1.1% | 2.7% |

| Indigenous Peoples | 5.3% | 4.0% | 5.0% | 5.2% | 4.0% | 4.8% | 5.2% | 3.9% | 5.0% | 5.4% | 3.7% | 4.9% |

| Persons with disabilities | 5.4% | 4.0% | 4.0% | 5.3% | 4.4% | 4.3% | 5.3% | 4.5% | 4.1% | 5.7% | 5.1% | 4.7% |