Economic analysis of the Pan-Canadian Framework

On December 9, 2016, the First Ministers of Canada agreed to the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. The following Questions and Answers provide an overview of the analyses of the environmental and economic impacts of the Pan-Canadian Framework undertaken by the Federal government with input from the provinces and territories.

Q1: How has the Government of Canada considered economic, environmental and social costs and benefits in adopting the Pan-Canadian Framework?

A1: The Government of Canada has and will continue to analyze the economic benefits and costs of the full set of measures in the Pan-Canadian Framework, as well as its environmental and social benefits. We are committed to transparency regarding the assumptions, benefits and costs of this analysis.Clean growth and climate change policy options, including those contained in the Pan-Canadian Framework, have been analyzed extensively by governments and a wide variety of think-tanks, academics and other experts including non-governmental organizations and industry associations. The selection of measures in the Pan-Canadian Framework was also informed by input from Canadians across the country and by extensive analysis within government.

The development of the Framework started with the Vancouver Declaration on March 3, 2016, when First Ministers launched a federal-provincial-territorial process to identify options for action in four areas: how and where to reduce emissions; ideas for new innovation, technology and job creation; pricing carbon pollution; and preparing for and responding to the impacts of climate change. First Ministers asked working groups for each of those topics to identify options for taking action and asked the working groups to assess the likely economic and environmental impacts of each option identified.

The four working groups consisted of representatives of federal-provincial-territorial governments including specialists from departments and ministries of finance, innovation, economic development, transport, energy, natural resources and environment and climate change.

In identifying and analyzing options, the Specific Mitigation Measures and Carbon Pricing Mechanisms Working Groups drew from a wide range of existing sources, including the Ecofiscal Commission, Canadians for Clean Prosperity, Smart Prosperity, EnviroEconomics and Navius, the Council of Canadian Academies and numerous researchers from universities in Canada, the US and other countries.

The working groups also sought input directly from Canadians. The working groups on Specific Mitigation Opportunities and on Carbon Pricing Mechanisms jointly hosted a series of roundtables with invited stakeholders as well as multiple meetings with National Indigenous Organizations. Participants at these sessions were highly engaged, and brought forward a wide variety of issues, considerations and ideas. The Carbon Pricing Mechanisms Working Group also held a meeting with Canadian experts on carbon pricing to discuss issues and considerations related to the role that carbon pricing should play in the Framework. All of the working groups also received considerable input through the online portal from individual Canadians, civil society, academics, businesses and business associations. Some of this input included detailed analyses. All of the input provided to the portal was provided to the ministerial tables charged with overseeing the working groups and was made public.

To support the Working Group on Carbon Pricing Mechanisms, Government officials developed illustrative carbon pricing scenarios. Under the Working Group on Specific Mitigation Opportunities, officials modelled both the anticipated environmental impacts and the cost per tonne of the reductions that could be achieved by numerous mitigation options.

This analytical work will be updated and refined over time as governments finalize the design of specific measures, and as monitoring reports on their impacts. For example, at the federal level, each new Government of Canada policy measure developed under the Pan-Canadian Framework will be subject to additional economic cost-benefit analysis, and each proposed regulatory measure and its supporting analysis will be published for comment in the Canada Gazette, Part I before being finalized.

Q2: What are the costs of not taking action to address climate change?

A2: The impacts of a changing climate are already being felt, and the costs of inaction are much greater than the costs of addressing climate change.

The National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy concluded that the costs of climate change could represent about $5 billion per year by 2020 in Canada, and, depending on the levels of continued global emissions growth, could rise to $21 to $43 billion per year by 2050, or even higher under more extreme scenarios. 1

In 2014, the U.S. Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) issued a report concluding that the economic impacts of increasing temperatures would lead to significant and permanent global GDP losses. 2 The 2014 CEA report also emphasized the costs of delaying action. It estimated that, for the same level of temperature stabilization, each decade of delayed mitigation effort will lead to a 40% increase in net mitigation costs.

The Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC) recently cited estimates from the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) related to the financial costs of natural disasters, driven in part by climate change. Between 1970 and 1994, the federal government paid out an average of $54 million each year from its disaster fund, adjusted to 2014 dollars. By contrast, the PBO estimates that weather events connected to climate change over the next five years will cost the federal government $900 million annually.

Canada cannot avoid these costs solely by taking action on its own. But Canada must contribute to effective collective action globally in order to minimize the adverse impacts of climate change both here in Canada and around the world.

Q3: How will the Pan-Canadian Framework benefit Canadians?

A3: The transition to a low-carbon economy will benefit Canada and Canadians. Collectively, the Pan-Canadian Framework actions will reduce GHG emissions and help achieve Canada’s international 2030 emissions target, improve air quality and health, bolster investment in clean technology and innovation, enhance competiveness and create new jobs.

Investments in infrastructure, clean technology and in supporting mitigation actions under the Low Carbon Economy Fund will support business growth and job creation. For example, the Department of Finance estimated that the initial infrastructure investments funded in Budget 2016 will raise the level of GDP by 0.2 percent in 2016-17 and by 0.4 percent in 2017-18.

Investments in climate resilient infrastructure will also avoid significant costs. An example of this kind of infrastructure is the Red River Floodway. Originally constructed in 1968 at a total cost of $63 million, it was recently expanded in 2014, at a cost of $627 million. Since 1968, the Floodway has prevented over $40 billion (in 2011 dollars) in flood-related damages for the City of Winnipeg.

Other measures in the Pan-Canadian Framework will also result in benefits. Energy efficiency programs generate significant direct economic benefits to Canadian consumers and industry. Residential energy efficiency improvements helped Canadians save $12 billion in energy costs in 2013, an average savings of $869 per household. According to a report undertaken by the Acadia Centre for Natural Resources Canada, energy efficiency saves $3 to $5 for every $1 of government program spending. 3

The Government of Canada has committed to major investments to support research development, demonstration and adoption of clean technologies. 4 These investments will help Canada be a leader in clean technology, encourage “mission-oriented” research, enable the establishment of international partnerships, and will help Canadian clean technology businesses gain access to capital to bring their products and services to market. It will also support the adoption of clean technologies in northern, remote, and Indigenous communities. Actions for advancing clean technology and innovation will contribute to competitiveness and facilitate access by Canadian companies and workers to the rapidly growing global market demand for low-carbon goods and services.

Action to address climate change can also result in substantial co-benefits, like reducing air pollution and its harmful effects on human health and the environment. Coal-fired power generation units are among the largest sources of air pollution in the country, causing significant health and environmental impacts. Health studies completed by the Pembina Institute estimate that, in 2014, pollution from coal power resulted in more than 20,000 asthma episodes and hundreds of emergency room visits and hospitalizations, costing the healthcare system over $800 million annually. Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement for its 2012 regulation to phase-out coal-fired electricity estimated that the regulation would result in cumulative health benefits from 2015 to 2035 of $4.2 billion from reduced smog exposure – associated with reduced risk of death, avoided emergency room visits and hospitalization for respiratory or cardiovascular problems.

Q4: What are the costs of the Pan-Canadian Framework?

A4: The direct cost of the actions in the Pan-Canadian Framework, including carbon pricing, is projected to be modest, particularly in comparison to the projected benefits.

The Pan-Canadian Framework builds on the range of measures that are already in place at the federal, provincial, territorial and local levels. The economic costs and benefits of the pan-Canadian approach to pricing carbon pollution, in particular, will depend on the design of each provincial or territorial carbon pricing system and how each jurisdiction chooses to use the resulting revenue. Costs will also vary across the country, according to the degree of fossil fuel use for electricity generation, the types of fuels used for heating, and the mix of economic activity.

The Government has analysed the economic impacts of the Pan-Canadian Framework using ECCC’s peer reviewed, multi-region, multi-sector, provincial-territorial based computable general equilibrium CGE model (EC-PRO). The EC-PRO model is extensively used to support policy development within ECCC. EC-PRO was also used to support the analytical work of the Carbon Pricing Mechanisms Working Group.

Modelling projections always have a degree of uncertainty, but they provide helpful information about the potential range and magnitude of impacts of the Pan-Canadian Framework. Model-based estimates depend on a wide range of assumptions, including a projection of the future economy. Thus, to the extent that underlying assumptions are uncertain or future economic performance differs from the projections embedded in the models, the actual economic impacts will differ from the estimates presented below.

ECCC’s modelling projects that, in 2022, the measures in the Pan-Canadian Framework, including carbon pricing but excluding infrastructure investments and technology incentives, will reduce the level of GDP by about 0.35% compared to what it would have been otherwise. This is likely an overestimate because computable general equilibrium models of climate change policies, such as EC-PRO, do not capture the full range of benefits including direct benefits from public infrastructure investments, the development of new technologies and market opportunities, improved health, and contributions to the avoided costs of climate change. As a result, the Pan-Canadian Framework is expected to have various benefits that have not been captured by the EC-PRO model. Further, the EC-PRO model does not account for possible technological breakthroughs. In addition, as new technologies become available, their cost will likely fall and their overall effectiveness improve.

Q5: What are the impacts of carbon pricing?

A5: The specific impacts of the carbon pricing system within a given province or territory will depend on the design of the system and how that jurisdiction chooses to recycle any revenue that it generates by the carbon price.

Carbon pricing is a central component of the Pan-Canadian Framework. BC, Alberta, Ontario and Quebec, representing over 80% of Canada’s population, already have carbon pricing policies in place. Under the federal benchmark for pricing carbon pollution, all jurisdictions will have carbon pricing in place by 2018.

Economic analysis and growing international experience indicate that carbon pricing is the most efficient measure to achieve reductions. Carbon pricing provides an incentive for firms and consumers to take advantage of their own least-cost abatement options first and to continue to reduce emissions in all circumstances where it is cost-effective to do so. By creating incentives for consumers to shift their purchases towards less carbon-intensive goods, carbon pricing further reduces emissions and provides industry with an incentive to innovate and respond to the growing demand for low-carbon products.

Carbon pricing also generates revenue that can be recycled back into the economy, for example to reduce distortionary taxes and make the economy more efficient, to minimize impacts on vulnerable groups such as low-income households, or to support businesses that innovate, are more efficient, contribute to a clean economy, and create good jobs for the future. Governments can also invest carbon revenues in specific mitigation initiatives, like energy efficiency programs.

Canadian and international experience demonstrates that carbon pricing can achieve reductions while protecting the economy. For example, BC’s carbon tax helped to reduce emissions between 2008 and 2013, while BC’s economy grew faster than the rest of Canada.

Under the pan-Canadian approach to pricing carbon pollution, provinces and territories have the flexibility to design their pricing systems to best suit their needs and revenues from carbon pricing will remain with the province or territory of origin, allowing jurisdictions to decide how to best reinvest in their economy.

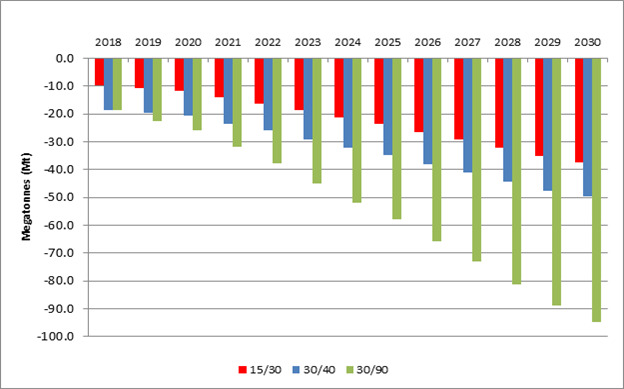

To better understand the implications of implementing additional carbon pricing policies in Canada, the Working Group on Carbon Pricing Mechanisms reviewed three illustrative scenarios: 15/30 scenario, (starting at $15/tonne in 2018 and rising to $30/t in 2030); a 30/40 scenario (starting at $30/t in 2018 and rising to $40/t in 2030); and a 30/90 scenario (starting at $30/t in 2018 and rising to $90/t in 2030).

These scenarios were designed to broadly illustrate the impacts on the economy of carbon pricing at various levels of pricing rather than to reveal the impacts of a specific policy proposal. All three scenarios were run against a baseline scenario that reflected the federal, provincial and territorial policies in place before September 2015 (including BC’s carbon tax, Alberta’s emission trading system for large final emitters, and Quebec’s cap-and-trade system). 5

The modelling done for the Working Group projected that the 15/30 scenario would lead to an additional 38 Mt of emission reductions relative to the baseline scenario in 2030, with larger reductions of 51 Mt for the 30/40 scenario and 95 Mt for the 30/90 scenario. The Figure below provides the projected annual emission reductions in each of the three illustrative scenarios.

Projected emissions reductions of three illustrative scenarios modelled for the Carbon Pricing Mechanisms Working Group

LONG DESCRIPTION

This figure provides the projected annual emission reductions in each of the three illustrative scenarios modelled for the Carbon Pricing Mechanisms Working Group.

- The 15/30 scenario (starting at $15/tonne of greenhouse gas emissions in 2018 and rising to $30/tonne in 2030): this scenario would lead to reductions of 38 Mt (megatonnes) of greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 relative to the baseline scenario.

- The 30/40 scenario (starting at $30/tonne of greenhouse gas emissions in 2018 and rising to $40/tonne in 2030): this scenario would lead to reductions of 51 Mt of greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 relative to the baseline scenario.

- The 30/90 scenario (starting at $30/tonne of greenhouse gas emissions in 2018 and rising to $90/tonne in 2030): this scenario would lead to reductions of 95 Mt of greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 relative to the baseline scenario.

Each of the three illustrative scenarios also projected very small reductions in the rate of growth of GDP, with average annual growth rates slowing by 0.02, 0.03 and 0.08 percent respectively for the three scenarios. These estimated economic impacts are very modest and fall within the range of real GDP forecast error, suggesting that any economic costs of carbon pricing are likely to be smaller than potential fluctuations in such economic drivers as world oil prices. In addition, these projected impacts do not take into account any of the potential positive impacts on growth from pricing policies.

External modelling analysis also supports the conclusion that carbon pricing at levels comparable to these illustrative scenarios or at the 2022 federal benchmark price of $50 per tonne would not have a significant negative impact on GDP in Canada. 6

The cost of carbon pricing to households will vary by province and territory, given differences in electricity generation mix (i.e., fossil-based versus non-emitting) and fuel consumption across provinces and territories, and will also depend on the design of each carbon pricing system and on how each province and territory chooses to recycle carbon revenues. For example, a carbon price of $50 per tonne of CO2 translates to about 11.5 cents per litre of gasoline; less if the gasoline contains biofuel.

In summary, even models that only account for costs and do not factor in benefits indicate that the overall estimated economic cost of the Pan-Canadian Framework will be modest, and the impact of carbon pricing is only a portion of that total cost. Further analysis on the economic impacts of carbon pricing, including for households and businesses, will become available as each province and territory clarifies the precise design of its carbon pricing systems, including how it will utilize its revenues, and as experience is gained with the interactive effects of the multiple policy measures that the federal, provincial and territorial governments will implement.

Q6: What are the next steps for economic analysis of the Pan-Canadian Framework?

A6: The Government is committed to assess and take stock of progress and impacts of the Pan-Canadian Framework, including through annual reports to First Ministers as measures under the Framework are designed and implemented.

ECCC will continue the practice, initiated in 2011, of reporting annually on GHG emissions and trends. In addition, Canada also reports on GHG emissions and trends biannually as part of our international commitments under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Each federal regulatory measure under the Pan-Canadian Framework will be subject to further rigorous cost-benefit analysis, which is a necessary step in the regulatory process, in order to assure that regulations are designed in order that the benefits outweigh the costs. The Government of Canada requires departments and agencies to conduct cost-benefit analysis of regulatory proposals as part of Regulatory Impact Analysis Statements, which are published as part of the regulation development process. On carbon pricing, the federal government will analyze costs and benefits of carbon pricing measures under the Pan-Canadian Framework as provinces and territories make the details of their carbon pricing plans known.

Federal, provincial and territorial governments will also engage with external experts to provide informed advice to First Ministers and decision makers. This will help ensure that actions under the Pan-Canadian Framework are open to external, independent review, and are transparent and informed by science and evidence.

On carbon pricing, federal, provincial, and territorial governments will work together to establish an approach to the review of carbon pricing, including expert assessment of stringency and effectiveness that compares carbon pricing systems across Canada. This will be completed by early 2022 to provide certainty on the path forward. An interim report will be completed in 2020 which will be reviewed and assessed by First Ministers. As an early deliverable, the review will assess approaches and best practices to address the competitiveness of emissions-intensive trade-exposed sectors.