2020–21 Departmental Results Report - Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

On this page

From the President

President of the Treasury Board

I am pleased to present the Departmental Results Report for the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) for 2020–21.

During this period, TBS worked to support the Government of Canada’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and to improve government operations for the benefit of all.

One way we can produce better results for those we serve is by ensuring that the public service reflects the diversity of Canada’s population and fosters a culture of belonging and trust so that our employees can realize their full potential. To accelerate progress in this area, TBS created the Centre on Diversity and Inclusion, which is co-developing solutions with equity-seeking employee networks. For example, the Mentorship Plus program has been launched to better support leadership development, specifically among members of under‑represented groups who aspire to leadership and executive positions.

A significant part of public service diversity stems from the commitment to bilingualism, ushered in by the Official Languages Act in 1969. In 2020–21, TBS worked closely with partners to support the government’s commitment to modernize the act. The proposed changes will ensure that clients are served in both official languages and that government programming enhances the vitality of English and French linguistic minority communities.

A focus on service has driven efforts to transform the way government serves members of the public to meet their needs and expectations in the digital age. The COVID-19 pandemic pushed the government to develop end-to-end digital services to support Canadians through the crisis, showing them that user-friendly, convenient and digital-first services from their government are possible.

TBS collaborated with partners to create services such as a web‑based tool to help Canadians determine which government benefits they could access during the pandemic. TBS also developed GC Notify, which Health Canada used to send out over 5 million notifications to Canadians with trusted, accurate and timely guidance about COVID‑19.

To ensure that Canadians received the critical support they needed during the pandemic, TBS worked closely with Shared Services Canada to provide public servants working from home with a secure, efficient and reliable network. As a result, despite working remotely, public servants were able to collaborate across departments to provide critical services to Canadians in record time.

TBS also supported the values of openness, transparency and accountability by collaborating with departments to host data and information about COVID‑19 on the Open Government Portal. To continue to promote these values across government, TBS and its partners consulted widely on developing the 2020–2022 National Action Plan on Open Government.

Open, transparent and accountable government also means ensuring that Parliamentarians and members of the public know how public funds are being spent. To continue to raise the bar on accountability, TBS strengthened the clarity and consistency of financial and performance reporting, and made it easier to find, analyze and compare financial, people and results data across departments. Because of the extraordinary circumstances caused by the pandemic, TBS made several changes to the presentation of the Estimates in order to enhance transparency.

In carrying out its regulatory oversight role, TBS supported the government-wide response to the pandemic by providing regulators with flexibilities in developing regulations. At the same time, TBS maintained key elements of due diligence such that Canada’s regulatory system has been an integral part of the country’s emergency response to the pandemic.

TBS also continued to provide government-wide leadership toward net‑zero, climate-resilient and green operations by releasing an updated Greening Government Strategy that commits the Government of Canada to reducing its own greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050.

Last year was a year like no other, and TBS employees once again demonstrated the dedication, innovation and professionalism that are the hallmarks of the federal public service. I invite you to read this report to find out more about what TBS is doing to make government better for the benefit of all.

Original signed by:

The Honourable Mona Fortier, P.C., M.P.

President of the Treasury Board

Results at a glance

-

In this section

Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat role

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) is a central agency that serves as the administrative arm of the Treasury Board. It provides leadershipFootnote 1 in relation to the following four core responsibilitiesFootnote 2 to help departmentsFootnote 3 fulfill government priorities and meet citizens’ expectations of government.

- Spending oversight

TBS oversees how the federal government spends taxpayers’ money by reviewing government programs, spending proposals and spending authorities, and by reporting to Parliament and Canadians on government spending. - Administrative leadership

TBS leads government-wide initiatives, develops policies and sets the strategic direction for federal government administration in areas such as digital government, access to information, and management of assets and finances. - Employer

TBS develops policies and sets the strategic direction for people and workplace management in the federal public service. It also manages total compensation in the core public administration and represents the government in labour relations matters. - Regulatory oversight

TBS develops and oversees policies to promote good regulatory practices in the federal government and regulatory cooperation across jurisdictions. It also reviews proposed regulations and coordinates reviews of existing regulations.

Performance summary

In 2020–21, TBS supported other government departments in their response to the COVID‑19 pandemic by helping them adapt their workplaces and working conditions to facilitate the shift to having public servants work remotely, and to ensure the continuity of services to Canadians. TBS also changed how it carried out its activities, since most of its employees were working remotely.

In 2020–21, TBS aimed to achieve 11 results, which it measured using 28 performance indicators.

- Targets met: 13 (these include targets related to employee wellness and regulatory oversight)

- Targets after March 31, 2021, on track to be met: 4 (these include targets related to the federal government’s greenhouse gas emissions)

- Targets not met: 7 (these include targets related to service delivery and the clarity of reporting on government spending); TBS will work with departments to meet Canadians’ high expectations of government results

- Targets with no data available: 4 related to employment equity indicators

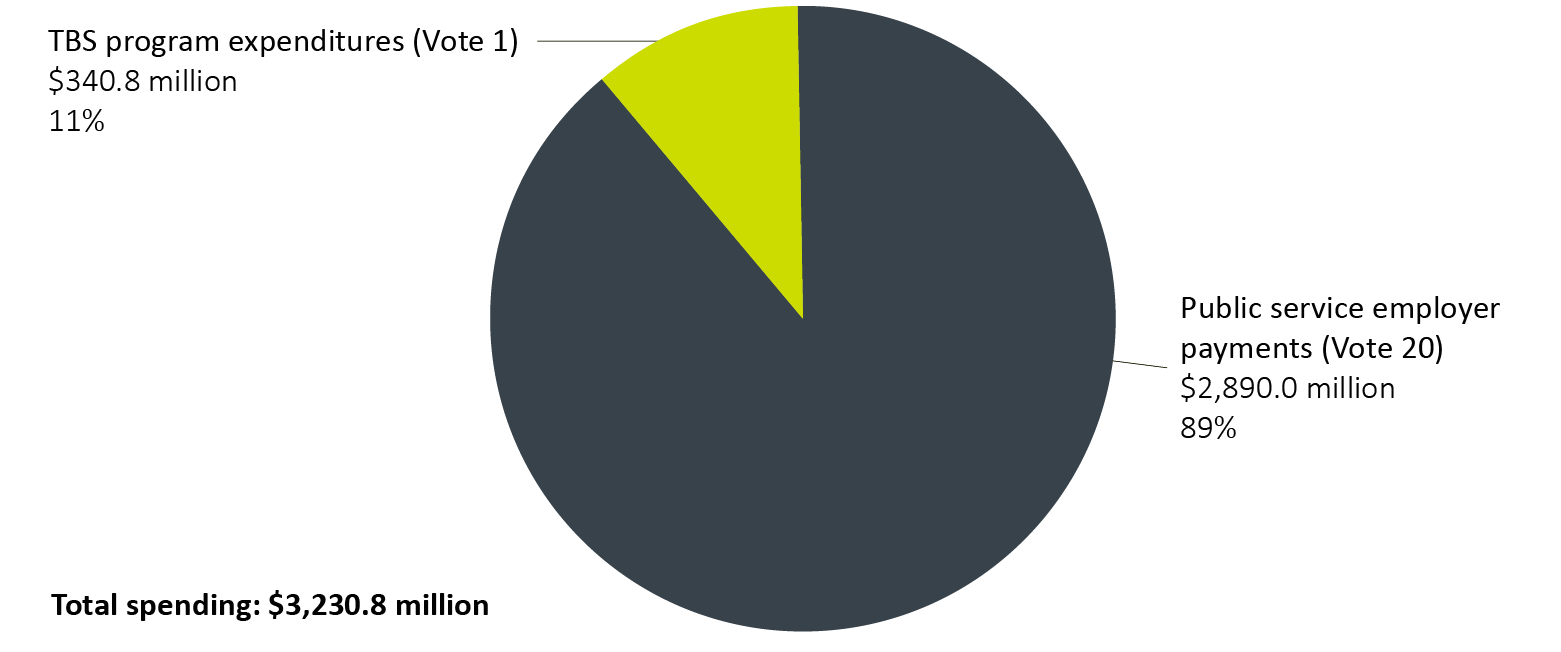

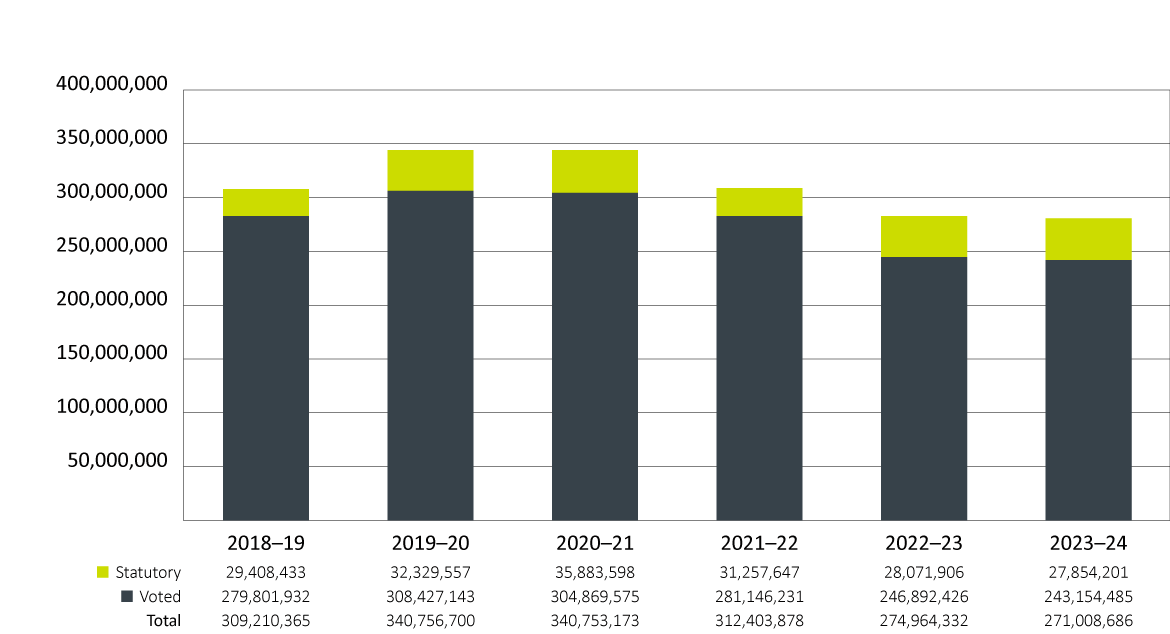

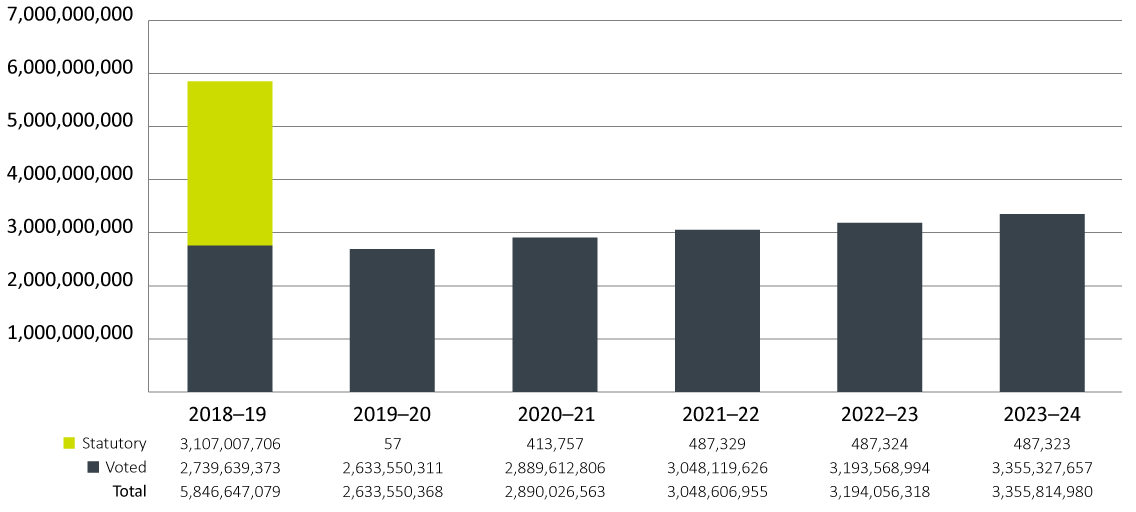

In 2020–21, total actual spending for TBS was $3,230,779,736, and total actual full-time equivalents was 2,330.

For more information on TBS’s plans, priorities and results achieved, see the “Results: what we achieved” section of this report.

Results: what we achieved

This section contains the following for each of TBS’s core responsibilities:

- a description of the responsibility

- the actions TBS took in 2020–21 to achieve its planned results in relation to the responsibility and whether it achieved these results

- a description of:

- how TBS used gender-based analysis plus

- TBS’s contributions to the Government of Canada’s efforts to implement the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,Footnote 4 and achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals

- experiments TBS undertook

- the financial and human resources that TBS allocated to achieving its planned results

This section also contains information about Internal Services at TBS in 2020–21 and the financial and human resources allocated to them.

Spending oversight

Description

- Review spending proposals and authorities

- Review existing and proposed government programs for efficiency, effectiveness and relevance

- Provide information to Parliament and Canadians on government spending

Results

In 2020–21, TBS aimed to achieve two results related to its spending oversight responsibility:

- Treasury Board proposals contain information that helps Cabinet ministers make decisions

- Reporting on government spending is clear

The following provides details on those results.

Departmental result 1 for spending oversight: Treasury Board proposals contain information that helps Cabinet ministers make decisions

The Government of Canada is committed to strengthening the oversight of the expenditure of taxpayer dollars and to exercising due diligence in relation to the costing information that departments prepare for proposed legislation and programs.

In 2020–21, TBS monitored spending trends and developed plans to support the government’s longer-term fiscal objectives by working with departments, primarily during the drafting of Treasury Board submissions, to ensure that the proposals:

- aligned with Treasury Board policies and government priorities

- supported value for money

- clearly explained the results that will be achieved and how those results will be measured

- contained clear assessments of risk, including financial risk

- supported the strategic use of information and technology, and a user-centred approach to services

In 2020–21, 77% of the Treasury Board submissions assessed transparently disclosed financial risk,Footnote 5 an increase from the previous year’s result of 54% and higher than the target of 75% by March 2023. The improvement is due in part to TBS’s efforts to help departments identify and document financial risks and to help them strengthen their costing capacity.

Departmental result 2 for spending oversight: reporting on government spending is clear

The Government of Canada is committed to improving the openness, effectiveness and transparency of government in various ways, including by strengthening the clarity and consistency of financial reporting.

As part of fulfilling this commitment, TBS strives to make sure that the information departments provide in their Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports and in GC InfoBase,Footnote 6 is clear, easy to find and easy to understand.

In 2020–21, to improve the clarity of reporting on government spending, TBS:

- added to the Estimates a reconciliation of the Estimates with the spending measures set out in the government’s fiscal policy documents (for example, the Fall Economic Statement 2020)

- added new data visualizations and datasets to GC InfoBase, including a page dedicated to the government’s planned expenditures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic

- provided feedback to departments on the quality of the information they collected on their performance

- updated the guidance on Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports and clarified the expectations and requirements for departments

To measure performance in this area, TBS surveys online readers of Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports and GC InfoBase users about the usefulness of the information in these products. The survey results for 2020–21 are as follows:

- the average rating for the usefulness of spending information in GC InfoBase was 3.9 out of 5, above the target of 3.5

- the average rating for the usefulness of the online versions of Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports was 3.3 out of 5, below the target of 3.5

To improve these results, TBS will work with departments to make Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports more useful based on readers’ feedback.

Gender-based analysis plus

In carrying out its core responsibility of spending oversight in 2020–21, TBS helped incorporate GBA Plus into government decision-making by:

- reviewing proposals submitted for Treasury Board approval to make sure they:

- take into account the needs, priorities and interests of different groups

- include plans for collecting data and reporting on the impacts in terms of gender and diversity of the proposed program

- as required under the Canadian Gender Budgeting Act, making available to the public analysis of impacts in terms of gender and diversity of Government of Canada expenditure programs through supplementary information tables to Departmental Results Reports

- helping departments improve the quality of their analyses by:

- offering learning resources and events to support the sharing of best practices in GBA Plus

- publishing competencies for heads of evaluation and heads of performance measurement

- distributing guidance on how to meet the requirements of the Policy on Results that relate to GBA Plus

- partnering with Statistics Canada to study women‑owned businesses that access business innovation and growth support programs

2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

In 2020–21, in fulfilling its core responsibility of spending oversight, TBS contributed to Canada’s implementation of the 2030 Agenda by working with the Privy Council Office, the Department of Finance Canada, and Women and Gender Equality Canada, to support Employment and Social Development Canada in developing an overall federal implementation plan for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

In addition, TBS reviewed departments’ Treasury Board submissions and provided guidance on how to ensure that proposed initiatives take into account the requirements of the SDGs.

For example, TBS made sure that proposals:

- met strategic environmental assessment requirements

- took into account potential impacts on climate change and identified any need to adapt as a result of those impacts

- aligned with the Greening Government Strategy

Through this work, TBS contributed to SDG 13.3 (improve education, awareness raising and human and institutional capacity on climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction and early warning).

| Departmental results | Performance indicators | Target | Date to achieve target | 2018–19 actual results |

2019–20 actual results | 2020–21 actual results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treasury Board proposals contain information that helps Cabinet ministers make decisions | Degree to which Treasury Board submissions transparently disclose financial risk (on a maturity scale of 1 to 5) | At least 75% | March 2023 | 45% | 54% | 77% |

| Reporting on government spending is clear | Degree to which GC InfoBase users found the spending information useful (on a scale of 1 to 5) | Average rating 3.5 out of 5 | March 2021 | Average rating 3.2 out of 5 |

61% (average rating 3.6 out of 5) |

78% (average rating 3.9 out of 5) |

| Degree to which visitors to online departmental planning and reporting documents found the information useful (on a scale of 1 to 5) | Average rating 3.5 out of 5 | March 2021 | Average rating 3.3 out of 5 |

Average rating 3.8 out of 5 | Average rating 3.3 out of 5 |

| 2020–21 Main Estimates |

2020–21 planned spending |

2020–21 total authorities available for use |

2020–21 actual spending (authorities used) |

2020–21 difference (actual spending minus planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3,622,079,027 | 3,622,079,027 | 1,092,749,686 | 39,858,663 | -3,582,220,364 |

| 2020–21 planned full-time equivalents |

2020–21 actual full-time equivalents |

2020–21 difference (actual full-time equivalents minus planned full‑time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 302 | 292 | -10 |

Financial, human resources and performance information for the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Program Inventory is available in GC InfoBase.

Administrative leadership

Description

- Lead government‑wide initiatives

- Develop policies and set the strategic direction for government administration related to:

- service delivery

- access to government information

- the management of assets, finances, information; and technology

Results

In 2020–21, TBS aimed to achieve four results in exercising its administrative leadership responsibility:

- Government service delivery is digitally enabled and meets the needs of Canadians

- Canadians have timely access to government information

- Government promotes good asset and financial management

- Government demonstrates leadership in making its operations low‑carbon

The following provides details on those results.

Departmental result 1 for administrative leadership: government service delivery is digitally enabled and meets the needs of Canadians

The Government of Canada is a large, complex institution that provides services to millions of Canadians every single day. Whether renewing a passport, filing taxes or accessing benefits, people expect government services and transactions to be as easy as streaming a movie or shopping online.

While work is underway to review and improve service standards for government services, not all services are easy to access and use. Some still involve paper-based processes or the lack of clear online information, resulting in clients moving to the phone or in-person service channels. Others are using complex PDF forms for simple procedures, such as informing the government of a change of address or marital status.

To make services easier to use and access, the Government of Canada is undertaking a digital transformation. It has committed to implementing generational investments to update and replace outdated information technology (IT) systems and modernize the way government delivers benefits and services to Canadians.

TBS is supporting this digital transformation by providing government‑wide leadership across four strategic pillars:

- Modernize legacy IT systems

The Government of Canada’s major service‑delivery systems are easy to use and maintain, stable and reliable, secure, and adaptable. - Improve services

Individuals and businesses are satisfied with and trust Government of Canada services, which are reliable, secure, timely, accessible, and easy to use from any device. - Take a coordinated approach to digital operations

Government of Canada public servants are happier and more productive; departments make better data-driven decisions; operations are more effective and efficient; costs are lower; and duplication of effort is reduced. - Transform the institution

Government of Canada public servants are digitally enabled through cultural and operational shifts and work on modern, diverse and multidisciplinary teams to serve the public better.

Supporting the Government of Canada’s response to the pandemic

TBS supported the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic by:

- working with Health Canada, and with provincial and territorial partners, to deliver COVID Alert, the nationwide COVID‑19 exposure‑notification app. Over 6.4 million people downloaded the app, and more than 23,000 used it to send alerts about COVID‑19 exposure

- working with Employment and Social Development Canada and Service Canada to launch the COVID-19 Benefits Finder in just a few weeks. This tool has helped over 1.9 million people find personalized information about social programs created during the pandemic that they might be eligible for; over 40% of users used the tool to apply for programs right away

- developing GC Notify,Footnote 7 which Health Canada used to send out over 5 million notifications through the “Get Updates on COVID‑19” service

- recruiting talent that meets the demands for digital services stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic

- providing research and design services to departments for web content and services relating to the COVID-19 pandemic

- partnering with the Canada School of Public Service and Code for Canada to run Open Call, a “living” catalogue of free, easy‑to‑use and reusable digital tools that help teams from all levels of government better serve people across Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic

- coordinating the government’s overall web presence with Health Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Privy Council Office

TBS also helped departments quickly shift to having most employees working from home by:

- rapidly deploying secure collaboration tools to help departments implement Microsoft Office 365

- providing guidance and best practices on information management and technology when working remotely

- providing information on options for implementing e-signatures as alternatives to wet signatures

Digital service delivery

In 2020–21, TBS did the following to help departments improve their digital service delivery:

- validated citizens’ expectations for a “tell‑us‑once” approachFootnote 8 and delivered a prototype of OneGC, a single online window for federal government services

- expanded the use of the Pan‑Canadian Trust FrameworkFootnote 9 by, for example:

- working with the Government of British Columbia, the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) and Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) to make it possible for British Columbians to use their BC Services Card to access their online CRA and Service Canada accounts

- working with ESDC, CRA and the Government of Alberta to standardize wording for federal-provincial trusted digital identity agreements

- launched a prototype of Sign-In Canada for people submitting expressions of interest in Western Economic Diversification Canada’s Business Scale-up and Productivity program

- led the implementation of a multi-factor‑authentication‑as‑a‑service capability as part of GCKey, the federal government’s credential service, which protects access to federal government services, including the My Service Canada account

- published guidance on event logging and patch management, which supports departments in conducting proactive IT security monitoring in their areas of responsibility

- developed a framework for assessing the security of software-as-a-service (SaaS) solutions used by the Government of Canada

- recommended how certain federal government services could be improved through the application of digital practices

- provided documents, tools and information sessions to help make departmental websites more secure and to implement the new Policy on Service and Digital

- started work on a new tool to help departments publish simple, accessible, online forms that Canadians can use to apply for services or benefits

Digital capacity

In 2020–21, TBS did the following to help the government build its digital capacity:

- supported training and development by, for example, participating in training delivered through the Canada School of Public Service’s Digital Academy

- shared digital practices and tools and helped departments adopt them by:

- developing, with partners, a new phonetic alphabet, inclusive illustrations and guidance on using feedback text boxes

- publishing a technical playbook so that other departments can build on the practices of the Canadian Digital Service, which is housed at TBS

- advised departments on job descriptions, hiring practices and competency development to help them build their in-house digital expertise

- amended the Standard on Email Management to improve email security

- clarified the requirements in the Directive on Automated Decision-Making, including the requirements to:

- notify Canadians of automation regardless of how they choose to access federal government services

- document automated decisions to meet monitoring and reporting requirements

- better account for privacy risks arising from the use of personal information by automated decision systems

- developed two new standards to include in the Directive on Service and Digital to support consistent IT service delivery

Results for 2020–21 show that overall, TBS’s efforts to digitally enable government service delivery are having an impact. For example, TBS surpassed its target for the degree to which clients are satisfied with the delivery of Government of Canada services, achieving a score of 63 out of 100, compared with the target of 60.Footnote 10 This result is not only an improvement on the previous score of 58, reported in 2017–18; it is also the highest score since client satisfaction started to be measured, in 1998.

However, results for 2020–21 also show that more work is needed in certain areas:

- 69% of priority services met their service standard, a slight decrease from 70% the previous year and below the target of 80%

- 72% of priority services were available online, up from 69% the previous year, but below the target of 80%

- 69% of Government of Canada websites delivered digital services to citizens securely, up from 57% the previous year, but below the target of 100%

To improve these results, TBS will work with departments to:

- increase the use of client feedback and user consultations to design and continuously improve government services

- identify more services that could be digitized and take steps to digitize them

- work with departments’ designated officials for cybersecurity to make government websites more secure and to provide tools like the Security Playbook for Information System Solutions and patch management guidance in order to improve the delivery of secure and trusted digital services

Departmental result 2 for administrative leadership: Canadians have timely access to government information

The Government of Canada is committed to improving the openness, effectiveness and transparency of government, and to being open by default.

As part of fulfilling this commitment, TBS works with federal government organizations on open government and on helping them better respond to access to information and personal information requests.

Open government

In 2020–21, TBS continued to lead the implementation of Canada’s 2018–2020 National Action Plan on Open Government by:

- consulting with the Multi-Stakeholder Forum on Open Government,Footnote 11, stakeholders and the public on the next open government action plan

- updating the Open Government Guidebook

- disclosing over 1.4 million records proactively

TBS coordinated the publication of 1,613 datasets on the Open Government Portal, including over 400 federal open‑data resources related to COVID-19. This result is below the 2020–21 target of at least 2,000 but above the 2021–22 target of at least 1,000.

TBS set a lower target for the current year because it wants to focus on the quality and usefulness of the data rather than on volume.

Access to information and personal information requests

In 2020–21, TBS worked to improve how federal government institutions respond to access to information and personal information requests by:

- expanding the use of the Access to Information and Privacy Online Request Service to 210 out of the approximately 265 government institutions that are subject to the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act

- providing guidance on their obligations in relation to requests for information under the Access to Information Act and under the Privacy Act

- addressing disruptions to access to information and privacy operations caused by the COVID‑19 pandemic, including by issuing:

- an Access to Information and Privacy Implementation Notice reminding ministers and institutions to make best efforts to respond to requests and to document decisions, and sharing best practices for business resumption

- Privacy Implementation Notices pertaining to the collection, use and disclosure of personal health information during the COVID‑19 pandemic

- the Interim Policy on Privacy Protection and related directives to give certain institutions more flexibility to implement programs and services in response to the COVID‑19 pandemic, while ensuring that privacy continued to be protected

TBS also began a review of the Access to Information Act to ensure that the access to information regime continues to provide open, accessible and trustworthy information to Canadians in this digital age. The review is focused on:

- reviewing the legislative framework

- examining opportunities to improve proactive publication to make information openly available

- assessing processes and systems to improve service and reduce delays

The review is being conducted in consultation with individual Canadians, Indigenous groups, the federal institutions that are subject to the act, the offices of the Information Commissioner of Canada and the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, and other interested stakeholders and experts. A report on the review, with recommendations, is expected to be presented to the President of the Treasury Board in 2022 and will be tabled in Parliament and published online.

TBS measures performance in the administration of the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act by tracking the degree to which institutions respond to Canadians’ access to information requests and personal information requests within legislated timelines.

Institutions have 30 days to respond to access to information requests or requests for personal information. For an access to information request, if an institution needs more time to respond, it can seek an extension within 30 days of receipt of the request. For a personal information request, if an institution needs more time to respond, it can seek an extension of up to 30 days beyond the initial 30‑day deadline.

Access to information requests

The target is to respond to 90% of access to information requests within legislated timelines. The target takes into account the fact that, because institutions have 30 days to seek an extension of the time limit for responding to a request, the time limit is usually exceeded. Of the access to information requests that institutions responded to in 2020–21, 70% were responded to within legislated timelines, up from 67% in 2019–20. About half of the institutions that responded to access to information requests met this target (69 out of 140, or 49.3%).Footnote 12 Seventy‑one institutions did not meet the target, mainly because of restrictions and workload pressures stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Personal information requests

The target is to respond to 85% of personal information requests within legislated timelines. The target reflects the fact that there are often extensions. Extensions can be for up to 30 days, which means that the time limit for responses is a maximum of 60 days in all. There is no maximum extension for access to information requests. Of the personal information requests that institutions responded to in 2020–21, 63% were responded to within legislated timelines, down from 79% in 2019–20. About half of the institutions that responded to personal information requests met the target (50 out of 99, or 50.5%).Footnote 13 Forty‑nine institutions did not meet the target, mainly because of restrictions and workload pressures stemming from the COVID‑19 pandemic.

TBS is working with the institutions that did not meet the targets to help determine how to improve their performance.

Departmental result 3 for administrative leadership: government has good asset and financial management practices

The Government of Canada is committed to ensuring the sound stewardship of government assets and finances and to improving its project management capabilities.

As part of fulfilling this commitment, TBS works to:

- put sound policies, standards and practices in place

- oversee performance and compliance across the government

- maintain and build professional communities

Asset management

In 2020–21, TBS:

- completed the first phase of the policy suite update, which included implementation of the new Policy on the Planning and Management of Investments

- completed the Horizontal Fixed Asset Review; in support of implementing some of the recommendations in the review, $5.2 million over 3 years was allocated in Budget 2021 to setting up a centre of expertise to examine best‑value real estate solutions and service delivery models

- completed the first full year of implementing the Directive on Government Contracts, Including Real Property Leases, in the Nunavut Settlement Area, which supports increased participation by Inuit firms in business opportunities in the settlement area

The indicator used to measure the effectiveness of the government’s asset and financial management practices is the percentage of departments that maintain and manage their assets over their life cycle. This indicator assesses:

- the targeted and actual reinvestment rates in real property

- the proportion of Crown-owned real property assets that departments include in their real property portfolio strategies

In 2020–21, 53% of assessed organizations were effectively maintaining and managing their Crown-owned real property assets. This result, which falls short of the target of 60%, is partly attributable to the following three factors:

- many departments did not have current and complete performance data for all of their real property assets at the time of publishing

- departments are not meeting their reinvestment targets for real property assets (for example, for maintaining or renovating aging buildings)

- some departments that have approved real property portfolio strategies did not update them in 2019–20

Maturing of the Government of Canada’s asset management practices will take time. The target result of 60% is anticipated to be achieved by the target date of March 2023. The result is expected to improve over time as departments collect and update foundational data on the performance, use and condition of their real property assets, and as they use that data to develop comprehensive, integrated real property portfolio strategies. TBS is supporting their efforts by developing formal guidance on real property portfolio strategies for practitioners in departments.

Financial management

In 2020–21, TBS:

- held four Internal Control Working Group (ICWG) sessions on the impact of COVID-19 on internal controls over financial reporting and on the transition from internal control over financial reporting to internal control over financial management

- established an advisory committee that met with 23 large departments and agencies to gather best practices relating to COVID-19 and internal controls over financial reporting and shared the results of the sessions with the ICWG and the chief financial officer community at large

In 2020–21, 100% of large departments demonstrated that they maintained a system of internal controls to mitigate the risks to programs, operations and resource management, surpassing the target of at least 97%. For example, after the pandemic was declared, the large departments updated their assessment of the risks to programs, operations and resource management or reassessed their internal controls over financial reporting to address any weaknesses relating to the changing control environment.

Project management

In 2020–21, TBS:

- worked with departments to improve their capabilities by, among other things:

- surveying the project management community to determine their development needs and to identify certification and education programs that could support the community

- adopting a project management competency framework to support senior designated officials in their roles and to support the project management community’s professional development

- improved collaboration on and enhanced support for major transformation projects across government by creating several committees of professionals who have relevant technical, procurement, legal and other expertise

- implemented lessons learned from previous IT projects, particularly lessons relating to sunk costs and major multi‑year contracts, by:

- sharing lessons learned from IT projects across government through the Senior Designated Officials Council and the Treasury Board Advisory Committee on Project Management

- making the information on the project management portal on the government intranet site more relevant and easier to navigate by adding resources and tools used by other government departments

- strengthened the reporting requirements for projects greater than $25 million to increase the transparency and monitoring of large, complex projects in accordance with the new Directive on the Management of Projects and Programmes

Departmental result 4 for administrative leadership: government demonstrates leadership in making its operations low‑carbon

The Government of Canada is committed to transitioning to net-zero carbon and climate-resilient operation, while also reducing environmental impacts beyond carbon, including on waste, water and biodiversity.

TBS is supporting this commitment through the Centre for Greening Government, which is housed at TBS. The centre is:

- leading and coordinating the federal emissions reduction, climate-resilience and greening government initiatives

- integrating knowledge from other leading organizations and sharing best practices broadly

- tracking and disclosing government environmental performance information centrally

- driving results to meet greening government environmental objectives

Leading by example on combatting climate change

In 2020–21, TBS strengthened the Greening Government Strategy. The updated strategy:

- sets new targets for net-zero, green and climate-resilient government operations, including reducing the government’s own greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050

- makes, for the first time, commitments to achieve net-zero emissions from the national safety and security fleet, green procurement and employee commuting

- encourages Crown corporations to adopt the strategy or an equivalent strategy of their own that includes a net-zero by 2050 target

In 2020–21, TBS did the following to help reduce the government’s carbon footprint and overall environmental impacts:

- incorporated green considerations into the new Policy on the Planning and Management of Investments, which now requires departments to consider opportunities to advance government environmental objectives when making investment decisions

- shared departments’ results and best practices for reducing environmental impacts in the areas of real property, fleet and procurement

- studied the carbon footprint of government procurement to identify the procurement categories that have the highest levels of embodied carbon and to take action to reduce them

- provided funding, through the Greening Government Fund,Footnote 14 for innovative projects undertaken by departments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in their operations; as of March 31, 2021, the fund has committed $18 million over 4 years to support 27 projects involving 12 departments

- launched the Greening Government Initiative with the United States; 32 countries participated in the initial discussion

Greening Government Fund initiative to minimize emissions on military bases

In 2019–20 and 2020–21, National Defence (DND) received funding from the Greening Government Fund for the project Minimizing Greenhouse Gas Emissions in an Optimized Base of the Future. Through this project, DND developed a tool designed to minimize greenhouse gas emissions at military bases while respecting operational requirements. Other departments could use this tool for campus‑style development.

By the end of 2020–21, the government’s overall reduction in greenhouse gas emissions was 40.6% below 2005 levels, compared with 34.6% the previous year and the interim target of reducing emissions by 40% by 2025. The level of reduction in 2020–21 is largely due to the decreased use of federal fleets and facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public health restrictions limited travel, and many public servants were working remotely. The government’s greenhouse gas emissions are expected to continue to fluctuate as the pandemic situation evolves.

Gender‑based analysis plus

In carrying out its core responsibility of administrative leadership in 2020–21, TBS helped incorporate GBA Plus into government decision-making by:

- producing resources and tools to support the initial implementation of the Policy Direction to Modernize the Government of Canada’s Sex and Gender Information Practices, which pertains to the collection of gender information on administrative forms. Departments can now access these resources and tools through Women and Gender Equality Canada

- developing an accessibility hub to centralize information and learning resources that departments can use to improve accessibility and to make their workplaces and services more inclusive for persons with disabilities

- leading and co-organizing events that reached tens of thousands of public servants, equipping them to remove barriers in the workplace and in the services they provide

- investing in innovative and experimental ideas, projects and initiatives through the Centralized Enabling Workplace Fund, which aims to improve workplace accommodation practices and remove systemic barriers that create a need for individual accommodation

- ensuring that services delivered to Canadians in partnership with other federal departments, such as COVID Alert and the COVID-19 Benefits Finder, involved numerous rounds of direct research and testing with a wide range of potential users of those services, including people who self-reported as non-white or non‑European

Experimentation

In November 2018, in partnership with Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) and National Defence, TBS launched a pilot project to assess the impact of using risk‑based contracting approvals rather than the dollar‑based thresholds set in the Contracting Policy.

Normally, PSPC has to seek Treasury Board approval for all defence contracts above its contracting limits, regardless of the risk and complexity of a particular contract. Under the pilot project, the Minister of Public Services and Procurement can enter into and amend defence contracts and contractual arrangements if they have low risk and low or medium complexity but exceed the Minister’s current approval limits.

The pilot project was completed in April 2020. The project was evaluated and was found to have achieved its objectives. According to the evaluation, the contracts considered under the pilot were appropriately identified as low risk and of low or medium complexity.

Given the positive results of the evaluation, the pilot has been extended to March 2025. The extension will allow for an assessment of more contracts and of the longer-term impacts of the approach. The results of the pilot will be used to make a recommendation on permanent changes to the Contracting Policy.

2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

In 2020–21, in fulfilling its core responsibility of administrative leadership, TBS contributed to Canada’s implementation of the 2030 Agenda by, among other things:

- updating the Greening Government Strategy, which includes more ambitious targets for reducing the government’s greenhouse gas emissions for real property and conventional fleet by 40% below 2005 levels by 2025 instead of by 2030 and for eliminating all emissions associated with government operations in order to achieve net‑zero carbon by 2050. These efforts supported SDG 13: to take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

- publishing guidance on green fleet procurement, which supported SDG 12.7: to promote public procurement practices that are sustainable, in accordance with national policies and priorities

- working with departments to improve government service delivery by, for example, accelerating progress to create a single online window for all government services and to set new performance standards. These efforts supported SDG 16: to promote just, peaceful and inclusive societies

| Departmental results | Performance indicators | Target | Date to achieve target | 2018–19 actual results |

2019–20 actual results |

2020–21 actual results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government service delivery is digitally enabled and meets the needs of Canadians | Degree to which clients are satisfied with the delivery of Government of Canada services, expressed as a score from 1 to 100table 4 note * | At least 60 | March 2022 | Survey not conducted in 2018–19 |

Survey not conducted in 2019–20 |

63 |

| Percentage of priority services that meet service standards | At least 80% | March 2021 | 69% | 70% | 69% | |

| Percentage of Government of Canada priority services available online | At least 80% | March 2021 | 74% | 69% | 72% | |

| Percentage of Government of Canada websites that deliver digital services to citizens securely | 100% | March 2021 | 44%table 4 note † | 57% | 69% | |

| Canadians have timely access to government information | Number of new datasets available to the public | At least 2,000 (new non-geospatial datasets) |

March 2021 | 3,168 new datasets published (11,340 total non‑geospatial datasets available in 2018–19 on open.canada.ca) |

Published 1,258 new records (non-geospatial) on the portal for 2019–20 | 1,613 |

| Percentage of access to information requests responded to within legislated timelines | At least 90% | March 2021 | 73% | 67% | 69% | |

| Percentage of personal information requests responded to within legislated timelines | At least 85% | March 2021 | 77% | 79% | 63% | |

| Government has good asset and financial management practices | Percentage of departments that maintain and manage their assets over their life cycle | 60% | March 2023 | 55% | 73% | 53%table 4 note ‡ |

| Percentage of departments that continuously monitor and improve their internal financial controls | 97% | March 2021 | 97% | 97% | 100% | |

| Government demonstrates leadership in making its operations low‑carbon | The level of overall government greenhouse gas emissions | 40% below 2005 levels | December 2030 | 32.6% below 2005 levels | 34.6% below 2005 levels | 40.6% below 2005 levels |

Table 4 Notes

|

||||||

| 2020–21 Main Estimates |

2020–21 planned spending |

2020–21 total authorities available for use |

2020–21 actual spending (authorities used) |

2020–21 difference (actual spending minus planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 86,245,749 | 86,245,749 | 120,210,360 | 116,655,799 | 30,410,050 |

| 2020–21 planned full‑time equivalents |

2020–21 actual full‑time equivalents |

2020–21 difference (actual full‑time equivalents minus planned full‑time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 500 | 771 | 271 |

Financial, human resources and performance information for the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Program Inventory is available in GC InfoBase.

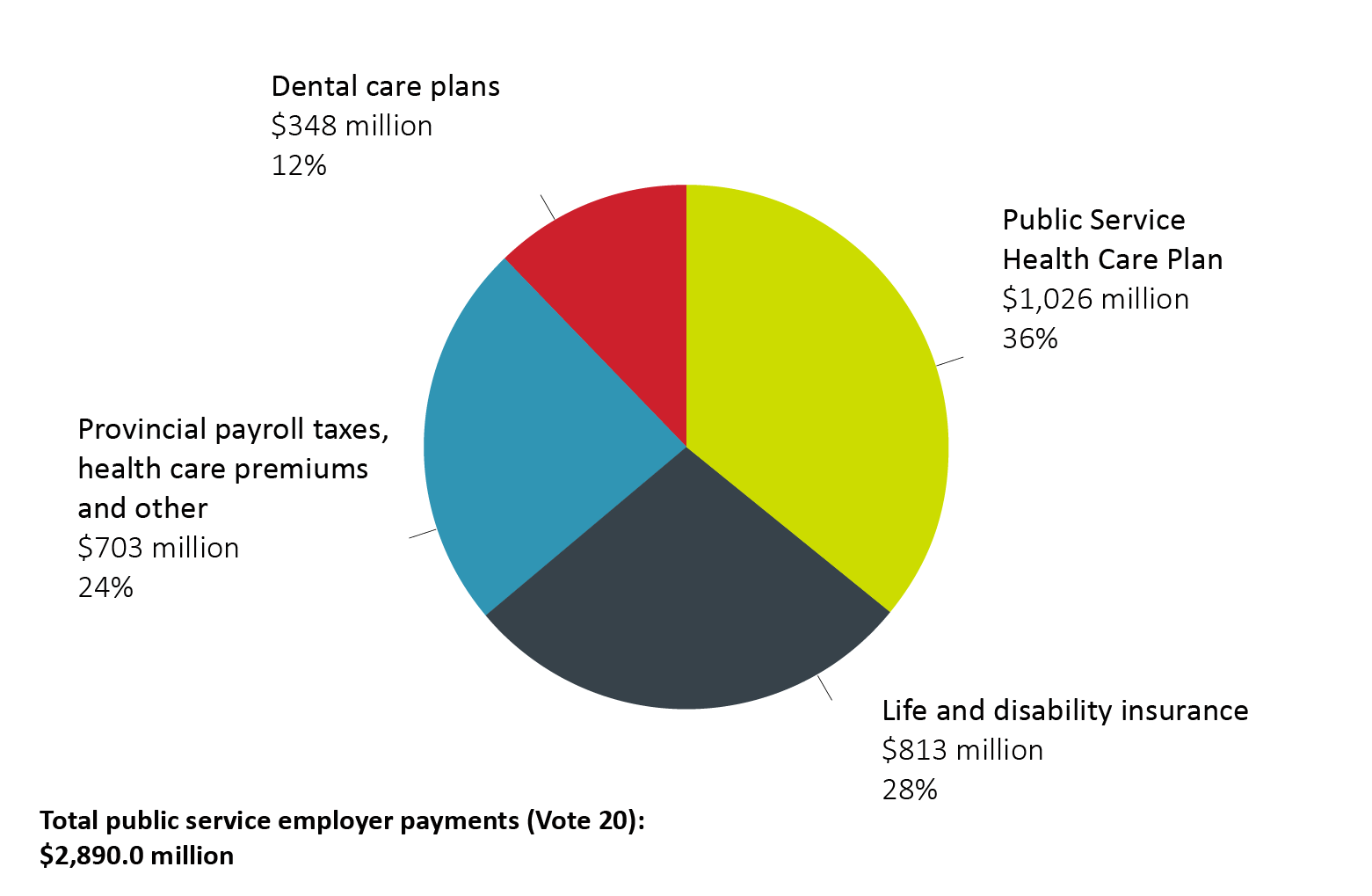

Employer

Description

- Develop policies and set the strategic direction for people management in the public service

- Manage total compensation (including pensions and benefits) and labour relations

- Undertake initiatives to improve performance in support of recruitment and retention

Results

In 2020–21, TBS aimed to achieve three results in relation to its employer responsibility:

- Public service attracts and retains a skilled and diverse workforce

- The workplace is healthy, safe and inclusive

- Terms and conditions of employment are fairly negotiated

The following provides details on those results.

Departmental result 1 for employer: public service attracts and retains a skilled and diverse workforce

Recruiting and retaining a skilled and diverse workforce that reflects the population it serves is a cornerstone of effective people management in the public service and helps build Canadians’ trust in government. The Government of Canada is committed to increasing the diversity of the public service, including in the senior ranks, by increasing the representation of the four groups designated under the Employment Equity Act (women, members of visible minorities, persons with disabilities and Indigenous peoples) and by removing barriers so that Canada’s public service remains a world leader in accessibility and inclusion.

TBS works with key stakeholders, including the Privy Council Office, the Public Service Commission of Canada and the Canada School of Public Service, to support the Treasury Board as the employer for the core public administration.

Deputy heads manage human resources in their own departments. TBS monitors their progress against the policy objectives set by the Treasury Board and fosters consistent, effective people management practices across the public service, including in the areas of inclusive recruitment and talent management, accessibility and official languages.

Inclusive recruitment and talent management

In 2020–21, TBS continued to work on various fronts to make recruitment more inclusive and to improve talent management practices, especially at senior levels. For example, TBS:

- launched the modernization of the executive leadership framework for the public service by introducing enterprise-wide succession planning for assistant deputy minister jobs, with a focus on:

- coordinating vacancies

- identifying talented executives from under-represented groups to take on leadership roles in the senior ranks

- increasing diversity through external recruitment of highly qualified candidates for select jobs

- identified Black executives to consider for promotion (an initiative of the Black Executives Network, in collaboration with TBS)

- adjusted the nomination criteria for the Executive Leadership Development Program to require that 50% of departments’ nominees be executives who have self-identified as Indigenous, visible minorities or persons with a disability; as of fall 2020, this requirement has resulted in the most diverse cohort of participants since the program started in 2016

- led a review of the Public Service Employment Act that resulted in amendments, in July 2021, to address systemic barriers to equity-seeking groups in public service staffing

- created the Centre on Diversity and Inclusion, which:

- launched the Mentorship Plus program across the public service, which pairs employees from under‑represented groups with executives who actively advocate on their behalf and who actively participate in their career development

- partnered with Indigenous employee networks across the public service to launch the Career Pathways for Indigenous Employees intranet site, which aims to reduce barriers to onboarding, employee retention and career development by providing tools and resources for managers and Indigenous employees

- launched the Federal Speakers’ Forum across the public service to promote key principles of diversity and inclusion and to change mindsets and behaviours

- is supporting a new community of practice of Designated Senior Officials for Employment Equity, Diversity and Inclusion

Centre on Diversity and Inclusion

In 2020–21, the Government of Canada established the Centre on Diversity and Inclusion, housed at TBS. The centre is dedicated to examining the barriers to achieving a diverse and inclusive workplace.

The centre’s mandate is to:

- lead new and innovative initiatives on diversity and inclusion

- develop innovative solutions for recruitment and talent management

- coordinate with stakeholders whose policies and programs affect the diversity and inclusion agenda

- co-develop solutions with the many diversity and inclusion networks across the public service

- lead change management and monitor ongoing progress on these priorities and commitments

In 2020–21, TBS also worked to raise managers’ awareness of the benefits of inclusive hiring practices by, for example:

- monitoring their department’s efforts to meet their employment equity obligations

- supporting and implementing plans to increase diversity and inclusion

As part of measuring its progress in this area, TBS monitors the levels of representation of the four employment equity groups in the executive ranks of the public service:

- women

- members of visible minorities

- persons with a disability

- Indigenous peoples

In keeping with the requirements of the Employment Equity Act, the target for the overall public service was to at least meet the workforce availability rates for these groups.

Although representation data for 2020–21 was not available at the time of publication, the overall public service has been meeting or exceeding workforce availability rates for women, Indigenous peoples and members of visible minorities for several years. At the executive level, representation rates for women and members of visible minorities have also been exceeding workforce availability, but rates for Indigenous persons and persons with a disability have fallen short. The 2020–21 data will be made available in the 2020–21 Employment Equity Annual Report and in the TBS 2022–23 Departmental Plan.

Some employees belong to more than one of these groups and have different experiences based on more specific identity factors. For this reason, in 2020–21, TBS:

- updated the self‑identification questionnaire to improve the accuracy, breadth and depth of employment equity data

- collected and shared disaggregated data on the representation of employment equity subgroups (for example, Inuit employees, Black employees, employees who have a mobility impairment) to help inform managers as they develop their recruitment and retention strategies

- launched a tool that lets Canadians access data on human resources in the public service, including demographic and employment equity data

- worked with departments to improve diversity in all areas and at all levels of the public service, including by increasing the representation of groups that already meet the overall public service workforce availability rates

Accessibility

The Accessible Canada Act came into force in 2019 and aims to identify, remove and prevent barriers for persons with disabilities in Canada. In response, the Government of Canada launched, in 2019, the Accessibility Strategy for the Public Service of Canada. Also known as “Nothing Without Us,” the strategy aims to prepare the public service to become a model of accessibility for others, in Canada and abroad.

In 2020–21, as part of leading and supporting the implementation of the accessibility strategy, TBS:

- supported the Public Service Commission of Canada, as policy co‑lead on employment in the public service, to:

- develop and implement recruitment programs for employees with disabilities

- establish and use pools of qualified talent with disabilities

- remove barriers to development and promotions for employees with disabilities

- worked with partners, including the Canada School of Public Service, to develop learning events for specific functional communities, such as managers and human resources professionals, and to support a culture change toward more inclusive and accessible employment practices

- continued to administer the Centralized Enabling Workplace Fund

Centralized Enabling Workplace Fund

In April 2019, the Government of Canada provided the Office of Public Service Accessibility, housed at TBS, with funding of $10 million over 5 years to establish a Centralized Enabling Workplace Fund.

The objective of the fund is to invest in innovative and experimental ideas, projects and initiatives aimed at improving workplace accommodation practices and, where possible, removing systemic barriers that create a need for individual accommodation.

In 2020–21, as part of administering the fund, TBS:

- published an in-depth literature review and comparative analysis of accommodation-related studies in Canada and abroad that substantiates the results of the 2019 Benchmarking Study of Workplace Accommodations in the Federal Public Service

- continued to fund the Lending Library Service Pilot Project at Shared Services Canada, a central point for commonly requested adaptive devices and technologies. Initially intended only for short‑term employees who have disabilities or injuries, the pilot has been expanded to include determinate (term) employees and indeterminate employees who remain at work while experiencing the short-term effects of a disability or injury

- piloted a GC Workplace Accessibility Passport that streamlines the workplace accommodation process for both employees and managers. The passport is updated when an employee’s circumstances change and follows them when they change jobs or managers

- piloted a self‑assessment tool that departments and agencies can use to assess their state of accessibility in each of the five areas of focus of Nothing Without Us: An Accessibility Strategy for the Public Service of Canada and to point them to guidance on the accessibility hub for removing barriers

- funded coaching and support services for managers and interns participating in the Federal Internship Program for Canadians with Disabilities

The Progress Report on Implementation of “Nothing Without Us” contains information on departments’ progress on implementing the accessibility strategy.

Official languages

TBS sets the policy direction for and supports federal institutions with respect to:

- their communications with the public in both official languages

- language of work in the federal public service

- the equitable participation of English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians in the federal public service

In 2020–21, TBS:

- provided analysis and advice to support the government’s efforts to modernize the Official Languages Act, which include a stronger oversight role for the Treasury Board. The analysis and advice provided contributed to the government’s positioning document (English and French: Towards a Substantive Equality of Official Languages in Canada) and, in June 2021, the tabling of the modernization Bill C‑32

- held bimonthly meetings with the 200 departments and Crown corporations that have official languages obligations to, among other things, share guidance on how to maintain linguistic duality in the remote work environment so that employees’ language of work rights are respected

- launched bootcamps to train official languages specialists and champions on fulfilling official languages responsibilities in their institutions

- hosted a virtual best practices forum on linguistic insecurity attended by 2,500 participants. Featured speakers were the Parliamentary Secretary to the President of the Treasury Board and the Commissioner of Official Languages. The forum included presentations on tools that help strengthen bilingualism in federal workplaces

In 2020–21, 93.4% of the federal institutions surveyed reported that communications in designated bilingual offices nearly always occurred in the official language chosen by the public. This result exceeds the performance target of 90% and last year’s result of 91%.

Departmental result 2 for employer: the workplace is healthy, safe and inclusive

The Government of Canada is committed to fostering a modern work environment that is healthy, safe, inclusive and accessible, and where public servants can be most productive.

TBS works with key stakeholders, including deputy heads, to fulfill this commitment.

To measure results relating to workplace health, safety and inclusion, TBS runs the annual Public Service Employee Survey.Footnote 15 In 2020–21, improvement across the public service was achieved in the following areas:

- harassment: 11% of employees indicated that they had been the victim of harassment on the job in the past 12 months (down from 14% the year before)

- psychological heath of the workplace: 68% of employees believed their workplace was psychologically healthy (up from 61% the previous year)

- discrimination: 7% of employees indicated that they had been the victim of discrimination on the job in the past 12 months (down from 8% the year before)

- respect for individual differences: 77% of employees indicated that their organization respected individual differences (for example, culture, work styles and ideas) (up from 75% the previous year)

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, TBS expanded the 2020 survey to assess the impact of the pandemic on federal workplaces and on employees’ health and wellness. TBS will continue to work with departments to improve health, safety and inclusion in the workplace for all employees.

In 2020–21, TBS also expanded support for departments to help them prevent harassment and violence in the workplace by, among other things:

- sharing best practices through the government intranet and engaging with communities of practice (occupational health and safety, labour relations, managers and harassment prevention)

- working with partners to launch training and tools related to harassment and violence prevention and recourse

- strengthening the Treasury Board policies on harassment and violence in the workplace to reflect the amended Work Place Harassment and Violence Prevention Regulations and to align with recent changes to the Canada Labour Code

- adding questions to the Public Service Employee Survey, including questions about employees’ experiences with harassment and racism in the workplace, to gather more data on wellness, inclusion and diversity

In 2020–21, TBS also provided leadership in adapting public service workplaces and conditions of work to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Responding to COVID-19 pandemic and recovery needs

With the declaration of the pandemic in March 2020 and the resulting public health restrictions, most federal public service employees shifted to working remotely. This shift meant that the government had to adopt special measures and adapt working conditions and workplaces to keep employees safe, to maximize efficiency and to continue providing services to Canadians.

TBS provided leadership, guidance and direction to the public service through:

- a plan to help deputy ministers implement special measures in their departments

- guidance on different issues, including:

- working remotely (published in June 2020 and updated in August 2020)

- numerous occupational health and safety and labour relations issues, such as rapid testing for COVID-19, vaccinations and the use of leave code 699, in consultation with Health Canada, bargaining agents and other stakeholders

- the Guidebook for Departments on the Easing of Restrictions: Federal Worksites, in collaboration with the Public Health Agency of Canada, Health Canada, Public Services and Procurement Canada, Shared Services Canada, and in consultation with bargaining agents and other stakeholders

It also:

- incorporated administrative flexibilities into the public service group insurance plans to ensure access to key benefits for employees and their eligible dependents during the pandemic

- created an online mental health information hub for employees and their families

- added questions to the Public Service Employee Survey to gather more data on employees’ mental health in light of the pandemic

It also launched:

- a web page so that employees could easily find the Employment Assistance Program contact for their organization

- a series of facilitated discussions, in collaboration with the Public Service Alliance of Canada, through the Joint Learning Program, to help employees and managers talk about pandemic‑related challenges

- the new Policy on People Management, Policy on the Management of Executives and their supporting instruments, which explain:

- the new elements that support the pandemic response

- how to move quickly to use new authorities

- how to seek policy exemptions to create new flexibilities where needed

- the Student Hiring Challenge, in collaboration with the Canada School of Public Service, the Privy Council Office and Public Services and Procurement Canada, which supported continued student hiring during the pandemic

In addition, TBS supported departments to create “blanket” Interchange Canada agreements to make it easier for people to move in and out of the core public administration and to provide surge capacity to deal with urgent pandemic efforts across levels of government.

TBS held over 60 National Joint Council updates and technical briefings for bargaining agents on the pandemic and followed up on issues raised, including those relating to terms and conditions of employment.

Departmental result 3 for employer: terms and conditions of employment are fairly negotiated

The Government of Canada is committed to maintaining a respectful relationship with Canada’s public service.

TBS works to achieve this commitment by:

- bargaining in good faith with public sector unions and working with them to negotiate terms and conditions of employment and fair compensation

- engaging with public sector unions to nurture and maintain professional and collaborative relationships, and to proactively address diversity and inclusion issues

In 2020–21, TBS:

- signed 6 collective agreements with bargaining agents for the core public service in the context of the 2018 round of bargaining, including the first collective agreement with the National Police Federation, which represents RCMP members and reservists

- supported separate agencies in concluding 10 fully signed collective agreements

- began collective bargaining negotiations with the two bargaining units (Police Operations Support, with the Canada Union of Public Employees, and Ships Officers, with the Canadian Merchant Service Guild) that have not yet concluded a collective agreement in the 2018 round

- continued collective bargaining negotiations with the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC) for the four bargaining units whose collective agreement expired in 2021

- successfully concluded negotiations with bargaining agents on compensation for damages relating to the Phoenix pay system and to the late implementation of the 2014 collective agreement, including the negotiation of catch-up agreements resulting from the damages agreement concluded with the PSAC

- supported Public Services and Procurement Canada as it continued processing the backlog of pay issues resulting from the implementation of Phoenix

- managed the government-wide process to reimburse employees who have incurred out‑of‑pocket expenses because of problems caused by Phoenix and to compensate them for general damages caused by that system

- continued to work with stakeholders such as bargaining agents, employees, and human resources and pay practitioners to help make sure the new pay system will address the needs of a modern public service

TBS also led the public service’s implementation of the recently passed Pay Equity Act by:

- supporting the Labour Program at Employment and Social Development Canada in drafting regulations for the act

- launching multilateral discussions with bargaining agents on the implementation of the act

To measure performance in relation to the fair negotiation of terms and conditions of employment, TBS monitors the results of labour relations cases that are heard by the Federal Public Sector Labour Relations and Employment Board, a quasi‑judicial tribunal that resolves such issues through adjudication or mediation. The target is that the outcomes of all cases that go before the board confirm that the employer bargained in good faith. In 2020–21, as in the previous 4 years, this target was met.

Gender‑based analysis plus

In carrying out its core responsibility of employer in 2020–21, TBS helped incorporate GBA Plus into government decision-making by:

- working with Employment and Social Development Canada’s Office for Disability Issues, with Women and Gender Equality Canada and with the Canada School of Public Service to strengthen GBA Plus by clarifying information on the accessibility and disability inclusion lens that is to be used when developing policies, programs and initiatives in the Government of Canada

- creating and publishing templates for creating Word documents and PowerPoint presentations that meet accessibility standards so that materials are inclusive by default

In collaboration with Women and Gender Equality Canada, a GBA plus training session was given to a number of TBS executives to increase the use of GBA plus when developing and implementing policies on people management.

Experimentation

In September 2020, TBS launched the Self‑Identification Modernization Project to help increase the accuracy, depth and breadth of employment equity data across government. The project explored ways to reduce the stigma associated with self‑identification. Following extensive research and consultations, a new questionnaire was designed with employees from various diversity networks. Preliminary testing shows that the new form has increased intent to self‑identify.

2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

In 2020–21, in fulfilling its core responsibility of employer, TBS contributed to Canada’s implementation of the 2030 Agenda by:

- continuing to work with departments to increase representation of women and members of other minority groups in leadership positions. This work supports SDG 5: to ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision‑making in political, economic and public life

- working with departments to better address and prevent harassment and violence in the public service, which is helping advance:

- SDG 10: to ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including through eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and actions in this regard

- SDG 16: to significantly reduce all forms of violence

| Departmental results | Performance indicators | Target | Date to achieve target | 2018–19 actual results |

2019–20 actual results | 2020–21 actual results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public service attracts and retains a skilled and diverse workforce | Percentage of executive employees (compared with workforce availability) who are members of a visible minority group | At least 10.6%table 9 note * | March 2023 | 11.1%table 9 note † | 11.5%table 9 note ‡ | Not availabletable 9 note § |

| Percentage of executive employees (compared with workforce availability) who are women | At least 48%table 9 note * | March 2023 | 50.2%table 9 note † | 51.1%table 9 note ‡ | Not availabletable 9 note § | |

| Percentage of executive employees (compared with workforce availability) who are Indigenous persons | At least 5.1%table 9 note * | March 2023 | 4.1%table 9 note † | 4.1%table 9 note ‡ | Not availabletable 9 note § | |

| Percentage of executive employees (compared with workforce availability) who are persons with a disability | At least 5.3%table 9 note * | March 2023 | 4.6%table 9 note † | 4.7%table 9 note ‡ | Not availabletable 9 note § | |

| Percentage of institutions where communications in designated bilingual offices “nearly always” occur in the official language chosen by the public | At least 90% | March 2021 | 83% | 91% | 93.4% | |

| The workplace is healthy, safe and inclusive | Percentage of employees who indicate that they have been the victim of harassment on the job in the past 12 months | Year-over-year decrease | March 2021 | 15% | 14% | 11% |

| Percentage of employees who believe their workplace is psychologically healthy | Year-over-year increase | March 2021 | 59% | 61% | 68% | |

| Percentage of employees who indicate that they have been the victim of discrimination on the job in the past 12 months | Year-over-year decrease | March 2021 | Not applicabletable 9 note ‖ | Not applicabletable 9 note ‖ | 7% | |

| Percentage of employees who indicate that their organization respects individual differences (for example, culture, workstyles and ideas) | Year-over-year increase | March 2021 | Not applicabletable 9 note ‖ | Not applicabletable 9 note ‖ | 77% | |

| Terms and conditions of employment are fairly negotiated | Percentage of Federal Public Sector Labour Relations and Employment Board outcomes that confirm that the Government of Canada is bargaining in good faith | 100% | March 2021 | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Table 9 Notes

|

||||||

| 2020–21 Main Estimates |

2020–21 planned spending |

2020–21 total authorities available for use |

2020–21 actual spending (authorities used) |

2020–21 difference (actual spending minus planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,230,326,777 | 2,230,326,777 | 3,243,834,453 | 2,969,957,193 | 739,630,416 |

| 2020–21 planned full‑time equivalents |

2020–21 actual full‑time equivalents |

2020–21 difference (actual full‑time equivalents minus planned full‑time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 430 | 545 | 115 |

Financial, human resources and performance information for the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s Program Inventory is available in GC InfoBase.

Regulatory oversight

Description

- Develop and oversee policies to promote good regulatory practices

- Review proposed regulations to ensure they adhere to the requirements of government policy

- Advance regulatory cooperation across jurisdictions

Results

In 2020–21, TBS aimed to achieve two results in exercising its regulatory oversight responsibility:

- Government regulatory practices and processes are open, transparent and informed by evidence

- Regulatory cooperation among jurisdictions is advanced

The following provides details on those results.

Departmental result 1 for regulatory oversight: government regulatory practices and processes are open, transparent and informed by evidence

The Government of Canada is committed to continuing regulatory reform efforts in order to improve transparency, reduce administrative burden, and make Canadian business more competitive.

TBS supports this commitment by:

- raising awareness and providing guidance about the Cabinet Directive on Regulation

- performing a rigorous challenge function when reviewing regulatory proposals being presented to the Treasury Board

- implementing a suite of modernization initiatives to make the regulatory system more efficient and agile, and less burdensome for business

In 2020–21, TBS:

- informed departments of flexibilities in regulatory policy requirements to facilitate a rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic

- completed the second round of regulatory reviews and regulatory roadmapsFootnote 16 in the areas of clean technology, digitalization, technology neutrality, and international standards; participating departments and agencies are expected to publish their roadmaps in 2021

- continued to provide secretariat support to the External Advisory Committee on Regulatory Competitiveness, which helps the Treasury Board identify ways to modernize Canada’s regulatory system and improve regulatory competitiveness; the committee completed its mandate and summarized its 26 recommendations in two letters to the President of the Treasury Board in January and March 2021

- through the Centre for Regulatory Innovation, advanced regulatory experimentation to support innovation by, for example, administering the Regulatory Experimentation Expense Fund

- developed, with PSPC, tools and training material in preparation for the implementation of a new feature in the Canada Gazette that will make the rule‑making process more transparent by allowing Canadians to submit and view comments on regulatory proposals through an online portal

In 2020–21, TBS surpassed its target of 95% for two of the indicators of progress on regulatory practices:

- 99.09% of regulatory initiatives reported on early public consultation undertaken prior to first publication, up from 98.08% in 2019–20

- 96.10% of regulatory proposals had an appropriate impact assessment

In addition, TBS’s work led to Canada again achieving the target of ranking in the top 5 Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD) member countries with respect to the quality of their regulatory policy frameworks. The ranking is based on three composite indicators. Out of 38 regulatory systems assessed,Footnote 17 Canada’s ranked 3rd for stakeholder engagement, 4th for regulatory impact assessment, and 5th for ex‑post evaluation.

Departmental result 2 for regulatory oversight: regulatory cooperation among jurisdictions is advanced

Regulatory cooperation helps reduce unnecessary regulatory differences between jurisdictions.

The benefits of regulatory cooperation include lower costs, reduced barriers to trade, and more predictable regulatory environments while maintaining the health, safety and security of Canadians and the environment.

The Government of Canada is committed to continuing efforts to:

- harmonize regulations that maintain high safety standards

- make Canadian businesses more competitive

TBS leads efforts to fulfill this commitment by advancing regulatory cooperation among jurisdictions.

In 2020–21, TBS:

- worked with domestic and international regulatory partners to develop new regulatory cooperation work plans and work plan items, adding six new work plans across the following three regulatory forums:

- the Canada‑U.S. Regulatory Cooperation Council, which was established in 2011 to promote economic growth, job creation, and benefits to consumers and businesses through increased regulatory transparency and coordination between Canada and the United States