Annual Report for the 2020 to 2021 Fiscal Year: Federal Regulatory Management Initiatives

On this page

- Message from the President

- Introduction

- Types of federal regulations

- The federal government’s response to COVID 19

- Section 1: benefits and costs of regulations

- Section 2: implementation of the one-for-one rule

- Section 3: update on the Administrative Burden Baseline

- Section 4: regulatory modernization

- Appendix A: detailed report on cost-benefit analyses for the 2020–21 fiscal year

- Appendix B: detailed report on the one-for-one rule for the 2020–21 fiscal year

- Appendix C: administrative burden count

Message from the President of the Treasury Board

President of the Treasury Board

As the President of the Treasury Board, I am pleased to present this fifth annual report on federal regulatory management initiatives.

In 2020–2021, Canada’s regulatory system figured prominently in the government’s rapid response to COVID-19, as many of our key safety and recovery measures were made possible through regulatory instruments. Though the initial phase of our response is behind us, we are still dealing with the effects of the ongoing pandemic. Many of the measures we implemented to protect Canadians and address the economic impacts remain in place, and as the situation continues to evolve, so too will our response. From border restrictions and requirements for entry into Canada to financial support for workers and businesses, regulations must be adjusted to respond to the changing public health situation. As in the initial response phase, regulatory changes will continue to be important tools to address the pandemic and ensure the health and safety of Canadians.

Our response to COVID-19 has been an opportunity to learn what works and what more needs to be done to improve the agility of the regulatory system. Our efforts to respond rapidly and effectively to the pandemic, for example, are inspiring more flexible regulatory frameworks and highlighting the need to engage stakeholders early and often.

During the year, we also advanced many non-COVID-related issues in the areas of health, environment, safety and security, as we continued to implement the government’s regulatory agenda. Regulations are essential in achieving priorities such as pay equity and fighting climate change.

We are also encouraging competitiveness, agility and innovation as important tools in ensuring modern, efficient and effective regulations. In addition, the review of the Red Tape Reduction Act was an important way for Canadians and Canadian businesses to tell us how we could reduce unnecessary burden. For its part, the External Advisory Committee on Regulatory Competitiveness completed its first mandate last spring, making a total of 44 recommendations. For instance, it recommended giving stakeholders the flexibility to adopt new technologies to achieve regulatory goals and identifying ways to use digitalization to provide Canadians with efficient user-centric services.

I invite you to read this year’s report to learn about the important improvements we made to the regulatory system during the year and continue to make to set up regulators, stakeholders and Canadians for success.

Original signed by

The Honourable Mona Fortier

President of the Treasury Board

Introduction

This is the fifth annual report on federal regulatory management initiatives. This report is part of regular monitoring of certain aspects of Canada’s regulatory system.

This year’s report has four main sections:

- Section 1 describes the benefits and costs of regulations that were made by the Governor in CouncilFootnote 1 and that have a significantFootnote 2 cost impact

- Section 2 reports on the implementation of the one-for-one rule, fulfilling the Red Tape Reduction Act reporting requirement

- Section 3 sets out the Administrative Burden Baseline for 2020 and for previous years, providing a count of administrative requirements in federal regulations

- Section 4 provides an overview of current regulatory modernization initiatives underway

The regulations reported on in this document were published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, in the 2020–21 fiscal year, which covers the period from April 1, 2020, to March 31, 2021.

Types of federal regulations

Regulations are a type of law intended to change behaviours and achieve public policy objectives. They have legally binding effect and support a broad range of objectives, such as:

- health and safety

- security

- culture and heritage

- a strong and equitable economy

- the environment

Regulations are made by every order of government in Canada in accordance with responsibilities set out in the Constitution Act. Federal regulations deal with areas of federal jurisdiction, such as patent rules, vehicle emissions standards and drug licensing.

The Cabinet Directive on Regulation (CDR) is the policy instrument that governs the federal regulatory system. There are three principal categories of federal regulations. Each is based on where the authority to make regulations lies as determined by Parliament when it enacts the enabling legislation:

- Governor in Council (GIC) regulations are reviewed by a group of ministers who recommend approval to the Governor General. This role is performed by the Treasury Board.

- Ministerial regulations are made by a minister who is given the authority to do so by Parliament; considerations such as impact, permanence and scope of the measures are taken into account when providing these authorities.

- Example: The Employment Insurance Act s. 153.3(1) authorizes the Minister of Employment and Social Development to make interim orders related to Employment Insurance to address the economic effects of the COVID‑19 pandemic.

- Regulations made by an agency, tribunal or other entity that has been given the authority by law to do so in a given area, and that do not require the approval of the GIC or a minister.

- Example: The Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation Act authorizes the Board of the Corporation (CDIC) to make by-laws governing how financial institutions may represent themselves as CDIC members.

The federal government’s response to COVID‑19

The COVID‑19 pandemic is an extraordinary circumstance with unprecedented health and economic impacts, and the regulatory system has played a key role in the government’s response. The government has used a variety of regulatory tools to protect Canadians from the coronavirus and to manage the impacts of disruptions to the Canadian economy. Many of the proposals in this report addressed specific pandemic-related issues on an emergency basis.

The Treasury Board prioritized regulatory initiatives that directly addressed COVID‑19, while other regulatory business was deferred unless doing so would have significant legal or administrative implications or impacts on health, safety, security or the environment.

As well, recognizing the need for decision-making under tight time frames, the Treasury Board directed that the analytical requirements for priority initiatives could be modified if data or information were not available or if there was insufficient time or capacity to fulfill the standard requirements. This is permitted under section 5.5 of the Cabinet Directive on Regulation to address “exceptional measures.”

In practice, this meant that proposals with large resource implications could proceed with less detailed costing than usual, and other analytical requirements were relaxed.

Sections 1 and 2 of this report include further information on the modified analytical requirements and the specific regulations that were affected.

Section 1: benefits and costs of regulations

What is cost-benefit analysis?

In the regulatory context, cost-benefit analysis (CBA) is a structured approach to identifying and considering the economic, environmental and social effects of a regulatory proposal. CBA identifies and measures the positive and negative impacts of a regulatory proposal and any feasible alternative options so that decision-makers can determine the best course of action. CBA monetizes, quantifies and qualitatively analyzes the direct and indirect costs and benefits of the regulatory proposal to determine the proposal’s overall benefit.

Since 1986, the Government of Canada has required that a CBA be done for most regulatory proposals in order to assess their potential impact on areas such as:

- the environment

- workers

- businesses

- consumers

- other sectors of society

The results of the CBA are summarized in a Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS), which is published with proposed regulations in the Canada Gazette, Part I. The RIAS enables the public to:

- review the analysis

- provide comments to regulators before final consideration by the GIC and subsequent publication of approved final regulations in the Canada Gazette, Part II

Analytical requirements

The analytical requirements for CBA as part of a RIAS are set out in the Policy on Cost‑Benefit Analysis, which was introduced on September 1, 2018, in support of the Cabinet Directive on Regulation. The policy requires both robust analysis and public transparency, including:

- reporting stakeholder consultations on CBA in the RIAS

- making the CBA available publicly

Regulatory proposals are categorized according to their expected level of impact, which is determined by the anticipated cost of the proposal:

- no-cost-impact regulatory proposals: proposals that have no identified costs

- low-cost-impact regulatory proposals: proposals that have annual national costs of less than $1 million

- significant‑cost‑impact regulatory proposals: proposals that have $1 million or more in annual national costs

Table 1 illustrates how these categories are determined based on total annual costs or present value over 10 years.

| New cost impact level | Present value of costs (over 10 years) | Annual cost |

|---|---|---|

| None | No costs | No costs |

| Low | Less than $10 million | Less than $1 million |

| Significant | $10 million or more | $1 million or more |

The level of impact determines the degree of analysis and assessment that is required for a given regulatory proposal. This proportionate approach is consistent with regulatory best practices set out by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Table 2 shows the analysis required for each level of impact.

| Impact level | Description of costs | Description of benefits |

|---|---|---|

| None | Qualitative statement that there are no anticipated costs | Qualitative |

| Low | Qualitative | Qualitative |

| Significant | Quantified and monetized (if data are readily available) |

Quantified and monetized (if data are readily available) |

In this report, information on CBA covers GIC regulations only and is limited to regulatory proposals that have a significant cost impact; since these proposals require that the majority of benefits and costs be monetized, the overall net impact can be described in economic terms more clearly than proposals with low or no costs, which rely more on qualitative or quantified analysis.

Figures in this report are taken from the RIASs for regulations published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, in the 2020–21 fiscal year. To remove the effect of inflation, figures are expressed in 2012 dollars and, therefore, will vary from those published in the RIASs. This approach permits meaningful and consistent comparison of figures, regardless of the year in which regulatory impacts were originally measured.

Overview of benefits and costs of regulations

In the 2020–21 fiscal year, a total of 305 regulations were published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, compared with 324 in the 2019–20 fiscal year. Of these 305 regulations:

- 187 were GIC regulations (61.3% of all regulations)

- 118 were non-GIC regulations (38.7% of all regulations)

Of the 187 GIC regulations (compared with 184 in the 2019–20 fiscal year):

- 145 had no cost impact or low-cost impact (77.5% of GIC regulations and 47.5% of all regulations)

- 42 had significant cost impact (22.5% of GIC regulations)

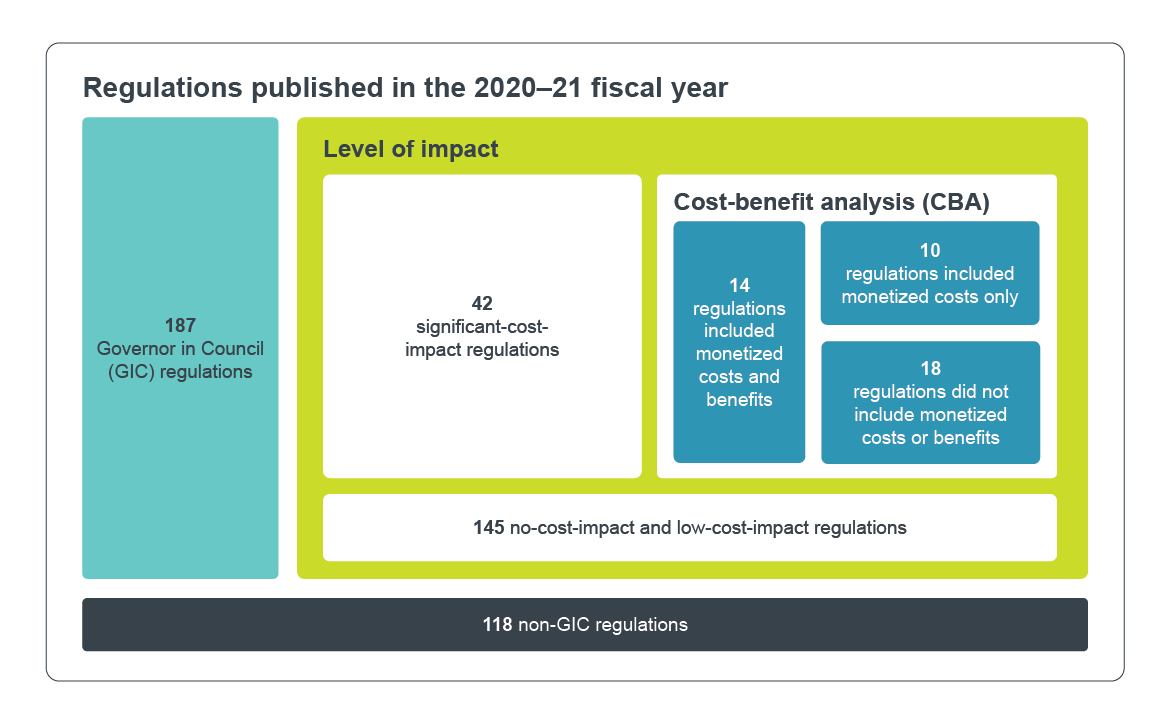

Figure 1 provides an overview of regulations approved and published in the 2020–21 fiscal year.

Figure 1 - Text version

Figure 1 provides an overview of the regulations published in the 2020-21 fiscal year.

During this period, 118 non-Governor in Council regulations were published, and 187 Governor in Council regulations were published.

Of the 187 Governor in Council regulations, 145 were no-cost-impact or low-cost-impact regulations, and 42 were significant-cost-impact regulations.

Of the 42 significant-cost-impact regulations, 14 included monetized costs and benefits, 10 included monetized costs only, and 18 did not include monetized costs or benefits.

Qualitative benefits and costs

The most basic element of any analysis of costs and benefits is a description of the expected impacts of the regulatory proposal. This description is based on a qualitative analysis and is used to:

- provide decision-makers with an evidence-based understanding of the anticipated impacts of the regulation

- provide context for further analysis that is expressed in numerical or monetary terms

Qualitative analysis should be part of the CBA of all regulatory proposals, including those that have no cost impact or low-cost impact.

The following are examples of qualitative impacts identified in significant‑cost‑impact regulations in the 2020–21 fiscal year:

- The Regulations Amending the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (Emergencies Act and Quarantine Act) (SOR/2020‑091) control and prevent the spread of COVID‑19 within Canada by ensuring that foreign nationals and employers of temporary foreign workers comply with measures that protect public health. The regulations provide benefits and protections to temporary foreign workers by requiring the payment of wages during the initial quarantine or isolation period upon entry to Canada, and by introducing new requirements pertaining to their accommodations.

- The Certain Goods Remission Order (COVID‑19) (SOR/2020‑101) waives customs duties on imports of medical supplies, including personal protective equipment (PPE). This waiver benefits Canadian essential service providers such as food-processing facilities, grocery stores, and pharmacies that are importing PPE and are not covered by any other COVID tariff relief measures.

- The Work Place Harassment and Violence Prevention Regulations (SOR/2020‑130) streamline the harassment and violence provisions for federally regulated workplaces that fall under Part II of the Canada Labour Code. Research and expert analysis suggest that the changes will benefit workers by reducing occurrences of harassment and violence in the workplace, which in turn will generate wide-ranging benefits such as reduced absenteeism, job burnout, disability payments, lost work time and litigation costs. These measures foster a collaborative work environment and a psychologically healthier and more motivated workforce, resulting in increased labour productivity.

Quantitative benefits and costs

Quantitative benefits and costs are those that are expressed as a quantity, for example:

- the number of recipients of a benefit

- the percentage reduction in pollution

- the amount of time saved

As is the case with qualitative information, quantitative benefits and costs can be used in two ways:

- on their own, they can illustrate the expected magnitude of a proposal by providing measurable figures to decision-makers

- they can be used as a factor in developing cost estimates

Quantitative analysis is an element of nearly all regulatory proposals that have a significant cost impact. Such analysis provides key metrics on the frequency or number of instances of an activity and is essential for estimating benefits and costs. Quantitative analysis can also be used on its own to illustrate the overall impact of a proposal in non-monetary terms. Although quantitative analysis is not required for proposals that have no cost impact or low-cost impact, it is often included alongside qualitative information because it can be useful to decision-makers.

The following are examples of quantified benefits and costs identified in significant‑cost‑impact regulations that were finalized in the 2020–21 fiscal year:

- The Regulations Amending the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations (SOR/2020‑108) designate 21 water bodies (44.96 hectares) frequented by fish for the disposal of mine waste generated by the Magino Mine Project near Wawa, Ontario. To offset the loss of fish habitat, the project proponent (Prodigy Gold Inc.) is required to implement a fish habitat compensation plan that will result in a direct gain of 47.25 hectares of fish habitat of equivalent or superior quality compared with fish habitat that the disposal of mine waste will destroy.

- The Reduction in the Release of Volatile Organic Compounds Regulations (Petroleum Sector) (SOR/2020-231) reduce fugitive releases of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from equipment leaks at petroleum refineries and upgraders, and at petrochemical facilities that are operated in an integrated way with these facilities. Reducing VOC releases improves air quality by reducing primary precursors of smog. Overall, the amendment will reduce fugitive VOC releases by approximately 90 kilotonnes and greenhouse gas emissions by 120 kilotonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) for the years 2021 to 2037.

- Given that many students faced reduced savings and loss of income due to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the Regulations Amending the Canada Student Financial Assistance Regulations (SOR/2020‑144) provided additional non-repayable grants and access to additional loans for new or returning post-secondary education students for the school year beginning in fall 2020. The regulatory amendments are in effect for one loan year (August 1, 2020, to July 31, 2021), and the nominal total cost of the regulatory amendments is $1.84 billion over three years, with the benefits to Canadians expected to outweigh the costs.

Monetized benefits and costs

Monetized benefits and costs are those that are expressed in a currency amount, such as dollars, using an approach that considers both the value of an impact and when it occurs.Footnote 3

An analysis of monetized costs and benefits is required for all regulatory proposals that have a significant cost impact. If the benefits or costs cannot be monetized, a rigorous qualitative analysis of the costs or benefits of the proposed regulation is required, and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) must be satisfied that there are legitimate obstacles to monetizing the impacts. In practice, most regulatory proposals with significant cost impacts include both monetized benefits and costs as part of the analysis.

In order for costs and benefits to be considered monetized, the dollar values used in a CBA are adjusted so that values and prices that occur at different times are equal:

- to their exchange value (inflation adjustment)

- when they occur (discounting)

Several proposals that were part of the government’s response to COVID‑19 were developed using modified analytical requirements. In the case of CBA, proposals identifying significant costs could state impacts qualitatively instead of monetizing them. As a result, the figures stated for this fiscal year are lower than would be expected in a typical year.

Of the 42 regulations with significant cost impacts that were finalized in the 2020–21 fiscal year, 24 of them had monetized impacts, representing 12.8% of GIC regulations. Of the 42 regulations:

- 14 had monetized benefits and costs

- 10 had monetized costs only

- 18 did not include monetized costs or benefits; of these, 15 were related to COVID‑19 and featured modified analytical requirements

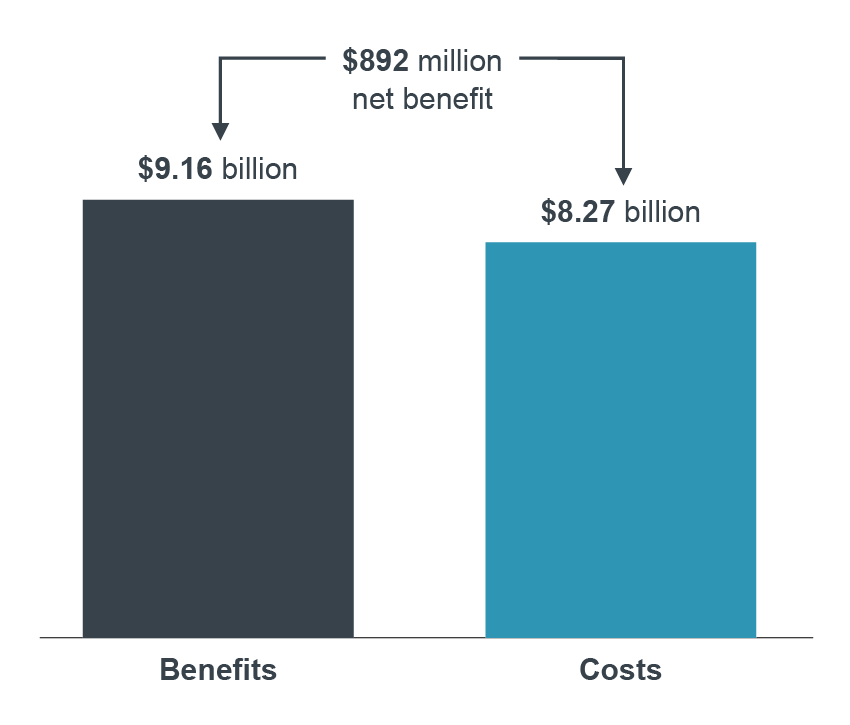

For the 14 regulations with significant cost impacts that had monetized estimates of both benefits and costs, expressed as total present value (see Figure 2): Footnote 4

- total benefits were $9,158,732,536

- total costs were $8,266,420,468

- net benefits were $892,312,068

Figure 2 - Text version

Figure 2 depicts the benefits and costs of significant-cost-impact regulations published in the 2020-21 fiscal year.

The benefits associated with significant-cost-impact regulations totalled $9.16 billion.

The costs associated with significant-cost-impact regulations totalled $8.27 billion.

The difference between the benefits and the costs is a net benefit of $892 million.

The following three significant‑cost‑impact regulatory proposals had the greatest net benefit of all proposals that were finalized in the 2020–21 fiscal year and that had monetized benefits and costs:

- The Regulations Amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Parts I and X — Offsetting of CO2 Emissions — CORSIA) (SOR/2020‑275) require private operators or air operators who fly internationally to offset their portion of global greenhouse gas emissions that exceed 2020 levels from the international aviation sector. This offset is done by using CORSIA Eligible Fuels or acquiring and cancelling emissions units on the international carbon market. These changes are expected to result in a net benefit of $370,791,265 between 2021 and 2035.

- The Canada Recovery Benefits Regulations (SOR/2021‑35) increase the maximum number of weeks of benefits entitlement under the Canada Recovery Benefit and the Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit to 38 weeks, and increase the maximum number of weeks of benefits entitlement under the Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit to four weeks. In addition, the Regulations Amending the Canada Labour Standards Regulations (SOR/2021‑36) extend the maximum length of leave related to COVID‑19 to align with changes to these programs. The net benefit of these changes is $271,293,285 over two years (2021–22 and 2022–23).

- The Navigation Safety Regulations (SOR/2020‑216) repeal nine existing regulations related to navigation safety and radiocommunication and consolidate them into one new regulation. The new regulation also transfers requirements relating to navigation safety from a 10th existing regulation, the Steering Appliances and Equipment Regulations. The new regulation will expand the carriage requirements of navigation safety and radiocommunication equipment to a wider category of vessels, which will enhance marine safety in terms of collision avoidance and search and rescue effort. The regulation also aligns Canada’s regulations with amendments to Chapters IV and V of the SOLAS Convention, allowing Canada to meet its international commitments, supporting harmonization efforts with other jurisdictions, and creating a clearer and simpler set of regulatory requirements while improving safety. The new regulation will also update terminology and clarify wording in regulatory requirements. In total, the changes will result in a net benefit of $104,250,368 between 2020 and 2031.

The purpose of CBA is to determine whether the expected benefits of a proposal are greater than the expected costs. This determination, however, is not based entirely on monetized benefits and costs. CBAs frequently include quantitative and qualitative analysis, in addition to monetized analysis, and the overall analysis must consider this broader range of evidence. In the 2020–21 fiscal year:

- three regulations that had a significant cost impact had monetized costs that were equal to monetized benefits, a result that is usually associated with a direct transfer from one party to another

- two regulations that had a significant cost impact had monetized costs that were greater than monetized benefits, which typically indicates that some benefits, such as broader societal benefits, could not be monetized and were stated qualitatively alongside benefits that were monetized

For detailed benefits and costs by regulation, see Appendix A.

Section 2: implementation of the one-for-one rule

The one-for-one rule

To comply with the annual reporting requirements of the Red Tape Reduction Act, this report also provides an update on the implementation of the one-for-one rule.

The one-for-one rule, which was instituted in the 2012–13 fiscal year, seeks to control the administrative burden that regulations impose on businesses.

Administrative burden includes:

- planning, collecting, processing and reporting of information

- completing forms

- retaining data required by the federal government to comply with a regulation

Under the rule, when a new or amended regulation increases the administrative burden on businesses, the cost of this burden must be offset through other regulatory changes. The rule also requires that an existing regulation be repealed each time a new regulation imposes new administrative burden on business.

The rule applies to all regulatory changes made or approved by the GIC or a minister that impose new administrative burden on business. It covers regulations with low cost impacts and those with significant cost impacts. Under the Red Tape Reduction Regulations, the Treasury Board can exempt three categories of regulations from the requirement to offset burden and regulatory titles:

- regulations related to tax or tax administration

- regulations where there is no discretion regarding what is to be included in the regulation (for example, treaty obligations or the implementation of a court decision)

- regulations made in response to emergency, unique or exceptional circumstances, including where compliance with the rule would compromise the Canadian economy, public health or safety

Regulators are required to monetize and report on:

- the change in administrative burden

- feedback from stakeholders and Canadians on regulators’ estimates of administrative burden costs or savings to business

- the number of regulations created or removed

As with CBA, the dollar values used in estimating administrative burden are adjusted so that values and prices that occur at different times are equal in their exchange value (inflation adjustment) and when they occur (discounting). In this report, all figures related to the one‑for‑one rule are expressed in 2012 dollars to permit meaningful and consistent comparison of regulations, regardless of the fiscal year in which they were introduced.

In 2015, the Red Tape Reduction Act enshrined the existing policy requirement for the one‑for‑one rule in law. Section 9 of the Red Tape Reduction Act requires that the President of the Treasury Board prepare and make public an annual report on the application of the rule.

The Red Tape Reduction Regulations state that the following must be included in the annual report:

- a summary of the increases and decreases in the cost of administrative burden that results from regulatory changes that are made in accordance with section 5 of the act within the 12‑month period ending on March 31 of the year in which the report is made public

- the number of regulations that are amended or repealed as a result of regulatory changes that are made in accordance with section 5 of the act within that 12‑month period

Key findings on the implementation of the one-for-one rule

The main findings on changes in administrative burden and the overall number of regulations for the 2020–21 fiscal year are as follows:

- system-wide, the federal government remains in compliance with the requirement in the Red Tape Reduction Act to offset administrative burden and titles within 24 months

- annual net administrative burden decreased by $2,053,606 in the 2020–21 fiscal year; since the 2012–13 fiscal year, annual net burden has been reduced by approximately $60.5 million

- 31 regulatory titles (net) were taken off the books, with a total net reduction of 185 titles since the 2012–13 fiscal year

A detailed report on regulations that had implications under the one-for-one rule is in Appendix B.

Under the one-for-one rule, regulatory changes in the 2020–21 fiscal year resulted in the following increases and decreases in the cost of administrative burden on businesses:

- $896,795 of new burden introduced

- $2,950,401 of existing burden removed

- net decrease of $2,053,606

The rule allows individual portfolios two years to offset any new burden introduced. As well, portfolios are allowed to bank burden reductions for future offsets within that portfolio. As a result, most of the $896,795 in new burden introduced in the 2020–21 fiscal year has already been offset:

- $736,235 of new burden was offset immediately by previously removed burden

- $160,560 of new burden had not yet been offset as of March 31, 2021

The changes introduced by the following three final regulations represented the largest changes in administrative burden in the 2020‒21 fiscal year:

- The Order Declaring that the Provisions of the Regulations Respecting Reduction in the Release of Methane and Certain Volatile Organic Compounds (Upstream Oil and Gas Sector) Do Not Apply in Alberta (SOR/2020‑233) reduces regulatory overlap and reporting burden by allowing Alberta to achieve equivalent methane emission reductions in the oil and gas sector in a manner that best suits its particular circumstances. Oil and gas facilities in Alberta will no longer need to comply with the administrative requirements associated with the federal regulations, resulting in average annualized cost savings of $1,305,206.

- The Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations and the Medical Devices Regulations (Post-market Surveillance of Medical Devices) (SOR/2020‑262) introduce new summary reports and issue-related analysis of safety and effectiveness that will impose an administrative burden on industry. However, the changes reduce the existing reporting requirements to a list of specified events related to foreign risk notification. Overall, the amendment results in a net reduction of $531,971 per year in administrative burden on business.

- The Order Declaring that the Provisions of the Regulations Respecting Reduction in the Release of Methane and Certain Volatile Organic Compounds (Upstream Oil and Gas Sector) Do Not Apply in Saskatchewan (SOR/2020‑234) reduces regulatory overlap and reporting burden by allowing Saskatchewan to achieve equivalent methane emission reductions in the oil and gas sector in a manner that best suits its particular circumstances. Oil and gas facilities in Saskatchewan will no longer need to comply with the administrative requirements associated with the federal regulations, resulting in average annualized cost savings of $386,793.

Under the one-for-one rule, regulatory changes in the 2020–21 fiscal year resulted in the following increases and decreases in the stock of federal regulations:

- 6 new regulatory titles imposing administrative burden on business were introduced

- 27 regulatory titles were repealed

- 13 existing titles were repealed and replaced with 3 new titles

While nine new titles were introduced over the course of the year, the rule allows individual portfolios two years to offset these titles. As is the case with administrative burden, portfolios are allowed to bank title repeals for future offsets within the portfolio. As a result, all of these nine new titles have already been offset:

- seven were offset immediately by previously removed titles

- two were offset by subsequent repeals in 2020–21.

The Treasury Board monitors regulators’ compliance with the requirement to offset new administrative burden and titles. System-wide, the federal government remains in compliance with the requirement in the Red Tape Reduction Act to offset new administrative burden and titles within 24 months.

TBS also tracks offsetting requirements by portfolio. As of March 31, 2021, Fisheries and Oceans Canada had an outstanding amount of $24,101 of burden that had exceeded the 24‑month period for offsetting; this situation has been reported in previous annual reports.

Of this outstanding balance, $23,190 relates to the Aquaculture Activities Regulations (SOR/2015-177), which were registered on June 29, 2015. The regulation introduced $409,513 in administrative burden on business, of which the department offset $151,761 prior to 2020–21. A further $234,562 was offset in 2020–21 by the Regulations Amending Certain Regulations Made Under the Fisheries Act (SOR/2020‑255).

During the 2020–21 fiscal year, two further Fisheries and Oceans Canada regulations surpassed the 24‑month period for offsetting burden:

- the Regulations Amending the Marine Mammal Regulations (SOR/2018-126) were registered on June 21, 2018, and introduced $738 in new burden

- the Banc-des-Américains Marine Protected Area Regulations (SOR/2019-50) were registered on February 24, 2019, and introduced $173 in new burden

Officials from TBS and from Fisheries and Oceans Canada continue to work together to identify opportunities to offset these outstanding amounts.

In the 2020–21 fiscal year, the Treasury Board approved the exemption of 16 regulations from the requirement to offset burden and titles:

- one was related to tax and tax administration

- four were related to non-discretionary obligations

- 11 were related to emergency, unique or exceptional circumstances

The total number of exemptions in 2020–21 is comparable to previous years. However, the number of exemptions related to emergency, unique or exceptional circumstances is proportionately higher since proposals related to COVID‑19 typically cited “emergency circumstances” to justify exemption.

Figure 3 - Text version

Figure 3 provides an overview of the implementation of the one-for-one rule for regulations published in the 2020-21 fiscal year.

There were 9 new regulations added and 40 regulations repealed, resulting in 31 fewer regulations in the regulatory stock.

There were 16 exemptions to the one-for-one rule, including 1 exemption for tax or tax administration, 4 non-discretionary obligations, and 11 emergency, unique or exceptional circumstances.

In total, 15 regulations increased burden by $896,795, and 16 regulations decreased burden by $2,950,401, for a net decrease of $2,053,606 in administrative burden costs.

In April 2020, the Government of Canada initiated a legislated review of the Red Tape Reduction Act to identify ways to further reduce unnecessary administrative burden on businesses and identify potential improvements to benefit the Canadian economy.

TBS undertook broad public consultations in 2019 on the Red Tape Reduction Act and other initiatives related to regulatory modernization. The resulting report, What We Heard: Report on Regulatory Modernization was posted online in November 2020 summarizing the key themes raised by stakeholders.

Section 3: update on the Administrative Burden Baseline

The Administrative Burden Baseline

The Administrative Burden Baseline (ABB) provides Canadians with a count of the total number of administrative requirements on businesses in federal regulations (GIC and non-GIC) and associated forms.

For the purposes of the ABB, an administrative requirement is a compulsion, obligation, demand or prohibition placed on a business, its activities or its operations through a GIC or non-GIC regulation. A requirement may also be thought of as any obligation that a business must satisfy to avoid penalties or delays. Regulatory requirements generally use directive words or phrases such as “shall,” “must,” and “is to,” and the ABB counts these references in the regulatory text or other documents.

The ABB was first publicly reported on in September 2014, providing a baseline count of administrative requirements by regulator. Since then, regulators continue to:

- do a count of their administrative requirements occurring from July 1 to June 30 each year

- publicly post updates to their ABB count by September 30 each year

Key findings on the Administrative Burden Baseline

The baseline provides Canadians with information on 39 regulators that are responsible for GIC and non-GIC regulations that contain administrative requirements on business.

As of June 30, 2020:

- the total number of administrative requirements was 137,089, an increase of 4,606 (or 3.48%) from the 2019 count of 132,483

- there were 599 regulations identified by regulators as having administrative requirements, an increase of 13 (or 2.22%) from the 2019 figure of 586

- the average number of administrative requirements per regulation was 228.9, an increase of 2.8 (or 1.2%) from the 2019 average of 226.1

The top three changes in the ABB in 2020 were:

- Health Canada’s count increased by 3,563 (16,495 to 20,058), primarily as a result of the legalization and regulation of new classes of cannabis products and the addition of new reporting requirements as part of the Cannabis Tracking System Order. The modernization and harmonization of the licensing and permitting scheme in regulations under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, as well as the new regulations under the Assisted Human Reproduction Act, also resulted in an increase in the 2020 count. In addition, the department’s response to address the COVID‑19 pandemic contributed to the increase.

- Changes to Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) regulations, directives and forms resulted in an overall net increase of approximately 309 requirements (5,154 to 5,463). Two regulations administered and enforced by the CFIA were amended or repealed, 10 incorporated directives were modified, existing forms were updated, and new forms were introduced to collect data to enable evidence-based decision-making.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada’s count increased by 263 requirements (12,542 to 12,805), primarily in relation to the introduction of the Output-Based Pricing Regulations (SOR/2019-266).

A detailed summary of the ABB count for 2020 and for previous years can be found in Appendix C.

Section 4: regulatory modernization

-

In this section

- Strengthening transparency and participation in the regulatory system

- Improving regulatory efficiency through cross-border cooperation

- Reducing barriers to economic growth and innovation

- Strengthening capacity to experiment and innovate

- Enabling the modernization of regulations through legislative change

The Government of Canada has been working to improve competitiveness, agility, efficiency and innovation of the Canadian federal regulatory system.

Strengthening transparency and participation in the regulatory system

Proposed regulations and Regulatory Impact Analysis Statements are published in the Canada Gazette, Part I, to solicit stakeholder feedback. Traditionally stakeholders have provided their feedback by mail or email, and their comments are summarized in a “What We Heard” report and taken into account in the development of the final regulation. Canadian stakeholders and trade partners have called for enhanced transparency of regulatory consultations, including the proactive release of public comments on regulatory proposals. As committed in the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA), a new commenting feature will allow stakeholders to review proposed regulations and submit their comments directly on the Canada Gazette, Part I, web page. Beyond the increased ease for stakeholders to comment on draft regulations, this tool will also result in greater transparency for stakeholder comments.

This initiative works alongside others that promote transparency and participation in the regulatory system. Other initiatives include the requirement for regulators to post online their plans to update or develop new regulations as well as their plans for reviews of existing regulations.

The External Advisory Committee on Regulatory Competitiveness (EACRC) brings together business, academic and consumer representatives to provide an independent perspective on regulatory barriers facing businesses. It was formed to help ministers and regulators modernize Canada’s regulatory system into one that protects health, security, safety, and the environment while promoting economic growth and innovation. At the end of March 2021, the first EACRC completed its mandate. Added to its earlier advice, their last recommendations were summarized in two letters to the President of the Treasury Board in:

EACRC advice in action

The very first recommendation made by the External Advisory Committee on Regulatory Competitiveness was that the government undertake a Regulatory Review of clean technology, digitalization and technology neutrality regulations and international standards. In June 2021, Roadmaps of those Reviews were released that lay out plans to advance regulatory modernization in support of economic growth and innovation:

- Clean Technology Roadmap

- Digitalization and Technology Neutrality Roadmap

- International Standards Roadmap

Updates on progress in implementing these roadmaps are expected to be posted annually.

Improving regulatory efficiency through cross-border cooperation

Regulatory cooperation is one of many tools that the government uses to improve efficiency and competitiveness in the regulatory system. Federal regulators cooperate with regulators across borders to:

- reduce unnecessary regulatory differences

- eliminate duplicative requirements and processes

- harmonize or align regulations

- share information and experiences

- foster innovation and collaboration

- adopt international standards

Additionally, the federal government has advanced 40 reconciliation items through three formal regulatory cooperation forums:

- 17 workplans through the Canada-United States Regulatory Cooperation Council established in 2011

- 5 workplans through the Canada-European Union Regulatory Cooperation Forum, established in 2018 under the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic Trade Agreement

- 18 workplan items through the Regulatory Reconciliation and Cooperation Table, established in 2017 between the federal government and all provinces and territories under the Canadian Free Trade Agreement.

Through these forums, regulators identify opportunities for cooperation and commit to workplans that advance their cooperation goals. Workplans are kept up to date online at Canada’s regulatory cooperation web page.

Reducing barriers to economic growth and innovation

Coordinated by TBS in partnership with federal departments and agencies, and in close consultation with stakeholders, targeted Regulatory Reviews examine existing regulations and related practices to address issues that impact economic growth and competitiveness without compromising health, safety, security and the environment. In addition, the Regulatory Reviews identify new ways to support regulatory innovation. For example, the reviews could identify pilot projects, opportunities to test innovative technologies using experiments or sandboxes, and opportunities to co-develop regulations with stakeholders.

Key features of the Regulatory Review process are transparency and responsiveness to stakeholders. Departments and agencies that participate in a Regulatory Review develop publicly available Regulatory Roadmaps that lay out a plan of action to address the issues identified by stakeholders along with associated timelines, where possible. Departments and agencies also contribute to consolidated Progress Reports for the Treasury Board and publish annual public updates online. To date, there have been two rounds of targeted Regulatory Reviews that have resulted in six Regulatory Roadmaps:

Regulatory Reviews Round 1: launched in 2018

Focused on three high-growth sectors:

- agri-food and aquaculture

- health and biosciences

- transportation and infrastructure

Regulatory Reviews Round 2: launched in 2019

Focused on three thematic areas:

- clean technology

- digitalization and technology-neutral regulations

- international standards

Across the six Regulatory Roadmaps, over 100 concrete actions have been identified to support regulatory modernization. These actions include bringing forward 17 new regulatory packages to update regulations and the identification of over 15 novel regulatory approaches. Incremental funding was provided in Budgets 2019 and 2021 to implement several Roadmap actions.

Review Roadmaps can be found online at the Targeted Regulatory Reviews web page.

Case study: Health and Biosciences Regulatory Review Roadmap

The Health and Biosciences Regulatory Review Roadmap addressed regulatory issues and irritants raised by industry, patient advocacy groups and professional associations across a variety of regulated products. The Roadmap focused on:

- enhancing collaboration with international partners

- improving the agility of regulatory systems to be more risk-based

- addressing rigidity in regulatory frameworks to better reflect updated science and support innovative technologies

For example, as the lead department for this Roadmap, Health Canada sought new legal authorities to be able to customize regulatory requirements for innovative health products. These new authorities helped to minimize barriers to market entry for advanced biomedical innovations and enabled Health Canada to create alternative authorization pathways for COVID‑19-related drugs and vaccines.

Strengthening capacity to experiment and innovate

Regulatory experiments, such as regulatory sandboxes and pilot projects, involve testing new technologies and different regulatory approaches. These experiments help identify what works and what doesn’t, building evidence that regulators can use to create and administer effective regulatory regimes. This process helps industry bring innovative products and services into the marketplace, ultimately improving regulatory outcomes for Canadians.

The Centre for Regulatory Innovation (CRI) provides tools, advice and funding to help federal regulators experiment and innovate. Its activities include supporting new ways of working with industry to ensure that regulations are responsive to complex, rapidly evolving technological and business environments.

Innovation Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) is developing and piloting educational approaches to help regulators, businesses and other entities to adopt and use digital credentials to simplify and digitalize their processes, including for regulatory compliance and trade. Such credentials in turn would enable regulatory digitalization, the ability to transact digitally across the economy, and the reduction of regulatory and administrative burden. The Educational Approaches for Digital Credentials pilot is funded by the Centre for Regulatory Innovation.

The first phase (fall 2020 to spring 2021) consisted of developing three educational approaches for testing with participants. During Phase 2 (spring 2021 to spring 2022), ISED will be piloting different combinations of educational approaches with testing groups to determine which approaches are the most effective.

Enabling the modernization of regulations through legislative change

Outdated regulatory frameworks are sometimes the result of out-of-date or overly rigid legislation. For example, outdated rules can block a regulator from adopting a new approach or technology, such as requiring a hand-signed documents instead of allowing a digital signature. Tools such as the Annual Regulatory Modernization Bill (ARMB) change legislation to remove irritants that add no value and impede modernization.

Modernizing enabling legislation

The first Annual Regulatory Modernization Bill (ARMB) included changes to 12 pieces of legislation. Several of these changes facilitate regulatory innovation and digitalization. For example:

- one amendment to the Canada Transportation Act enabled temporary exceptions from regulatory requirements to test and experiment with new products

- another amendment permitted electronic approaches in place of in-person or paper-based processes and documents (for example, digital signatures for ink signatures, email for fax)

The first ARMB also included several measures to eliminate regulatory irritants, such as amendments to the Importation of Intoxicating Liquors Act, which removed the federal requirement that the interprovincial movement of alcohol must be through provincial liquor authorities. It also included numerous changes to increase the transparency and efficiency of the regulatory process, such as amendments to the Hazardous Materials Information Review Act that allow for risk-based approaches to be taken for compliance and enforcement, therefore freeing up more resources for higher-value activities.

The first ARMB was included in the Budget Implementation Act, 2019, No. 1.

Appendix A: detailed report on cost-benefit analyses for the 2020–21 fiscal year

Figures in this appendix are taken from the RIASs in final federal regulations published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, in the 2020–21 fiscal year. To remove the effect of inflation, figures are expressed in 2012 dollars and vary from those published in the RIASs.

Table A1 shows GIC regulations finalized in the 2020–21 fiscal year that had significant cost impacts and that included both monetized benefits and monetized costs. These regulations may also include quantitative and qualitative data from a cost‑benefit analysis (CBA) to supplement the monetized CBA.

| Department or agency | Regulation | Benefits (total present value) | Costs (total present value) | Net present value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Table 1 Notes

|

||||

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | Regulations Amending the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (Amendment of Certain Fees) (SOR/2020‑45) | $335,341,241 | $267,029,343 | $68,311,898 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Regulations Amending the Ozone-depleting Substances and Halocarbon Alternatives Regulations (SOR/2020‑177) | $99,348,801 | $66,962,369 | $32,386,432 |

| Transport Canada | Locomotive Voice and Video Recorder Regulations (SOR/2020‑178) | $660,401 | $68,715,757 | -$68,055,356 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | Regulations Amending the Canada Student Financial Assistance Regulations (SOR/2020‑182)

|

$24,073,504 | $24,073,504 | $0 |

| Transport Canada | Navigation Safety Regulations, 2020 (SOR/2020‑216) | $183,077,963 | $78,827,596 | $104,250,368 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Reduction in the Release of Volatile Organic Compounds Regulations (Petroleum Sector) (SOR/2020‑231) | $232,955,249 | $231,556,398 | $1,398,851 |

| Transport Canada | Regulations Amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Parts I, V and VI — ELT) (SOR/2020‑238) | $60,890,794 | $23,728,147 | $37,162,647 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Off-road Compression-Ignition (Mobile and Stationary) and Large Spark-Ignition Engine Emission Regulations (SOR/2020‑258) | $147,162,293 | $72,088,933 | $75,073,360 |

| Transport Canada | Regulations Amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Parts I and X — Offsetting of CO2 Emissions — CORSIA) Amendments (SOR/2020‑275) | $1,659,952,206 | $1,289,160,941 | $370,791,265 |

| Elections Canada | Federal Elections Fees Tariff (SOR/2021‑22) | $56,823,162 | $56,823,162 | $0 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | Canada Recovery Benefits Regulations (SOR/2021‑35)

|

$6,163,705,255 | $5,892,411,971 | $271,293,285 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | Regulations Amending the Radiocommunication Regulations (SOR/2021‑40) | $194,741,667 | $195,042,347 | -$300,680 |

| Totaltable 1 note * | $9,158,732,536 | $8,266,420,468 | $892,312,068 | |

Table A2 shows GIC regulations finalized in the 2020–21 fiscal year that had significant cost impacts and that included monetized costs but not monetized benefits. If it is not possible to quantify the benefits or costs of a proposal that has significant cost impacts, a rigorous qualitative analysis of costs or benefits of the proposed regulation is required, with the concurrence of TBS.

| Department or agency | Regulation | Costs (total present value) |

|---|---|---|

| Transport Canada | Regulations Maintaining the Safety of Persons in Ports and the Seaway (SOR/2020‑54) | $84,304,096 |

| Pacific Pilotage Authority (Transport Portfolio) | Regulations Amending the Pacific Pilotage Tariff Regulations (SOR/2020‑58) | $19,971,785 |

| Great Lakes Pilotage Authority (Transport Portfolio) | Regulations Amending the Great Lakes Pilotage Tariff Regulations (SOR/2020‑59) | $27,936,262 |

| Laurentian Pilotage Authority (Transport Portfolio) | Regulations Amending the Laurentian Pilotage Tariff Regulations (SOR/2020‑85) | $14,718,727 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Regulations Amending the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations (SOR/2020‑108) | $16,196,838 |

| Department of Finance Canada | Regulations Amending the Regulations Amending Certain Regulations Made Under the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act, 2019 (SOR/2020‑112) | $16,484,326 |

| Labour Program | Work Place Harassment and Violence Prevention Regulations (SOR/2020‑130) | $525,278,676 |

| Health Canada | Vaping Products Promotion Regulations (SOR/2020‑143) | $6,836,055 |

| Transport Canada | Passenger Rail Transportation Security Regulations (SOR/2020‑222) | $8,645,122 |

| Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (Natural Resources Portfolio) | Regulations Amending Certain Regulations Made Under the Nuclear Safety and Control Act (Radiation Protection) (SOR/2020‑237) | $9,290,486 |

| Total | $729,662,373 | |

Table A3 shows GIC regulations finalized in the 2020–21 fiscal year that had significant cost impacts and that did not include monetized benefits and costs.

Appendix B: detailed report on the one-for-one rule for the 2020–21 fiscal year

Table B1: final GIC and ministerial regulatory changes in the 2020–21 fiscal year that had administrative burden implications under the one-for-one rule and that were published in the Canada Gazette, Part II

| Department or agency | Regulation | Net title change |

|---|---|---|

| New regulatory titles that have administrative burden | ||

| Canadian Energy Regulator (Natural Resources Portfolio) | International and Interprovincial Power Line Damage Prevention Regulations — Obligations of Holders of Permits and Certificates (SOR/2020‑49) | 1 |

| Labour Program | Work Place Harassment and Violence Prevention Regulations (SOR/2020‑130) | 1 |

| Labour Program | Standards for Work-Integrated Learning Activities Regulations (SOR/2020‑145) | 1 |

| Transport Canada | Locomotive Voice and Video Recorder Regulations (SOR/2020‑178) | 1 |

| Transport Canada | Passenger Rail Transportation Security Regulations (SOR/2020‑222) | 1 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Reduction in the Release of Volatile Organic Compounds Regulations (Petroleum Sector) (SOR/2020‑231) | 1 |

| Subtotal | 6 | |

| Repealed regulatory titles | ||

| Global Affairs Canada | Order Cancelling General Export Permit No. Ex. 31 — Peanut Butter (SOR/2020‑79) repealed:

|

(1) |

| Global Affairs Canada | Order Repealing Certain Orders Made Under the Export and Import Permits Act (SOR/2020‑80) repealed:

|

(3) |

| Global Affairs Canada | Regulations Repealing the Regulations Implementing the United Nations Resolution on Eritrea (SOR/2020‑118) repealed:

|

(1) |

| Department of Finance Canada | Order Repealing Certain Orders Made Under the Customs Tariff (CUSMA) (SOR/2020‑154) repealed:

|

(2) |

| Department of Finance Canada | Order Repealing Certain Regulations and Orders Made Under the Customs Tariff (CUSMA) (SOR/2020‑159) repealed:

|

(19) |

| Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat | Regulations Repealing the Protection of Personal Information Regulations (Miscellaneous Program) (SOR/2020‑210) repealed:

|

(1) |

| Subtotal | (27) | |

| New regulatory titles that simultaneously repealed and replaced existing titles | ||

| Transport Canada | Navigation Safety Regulations, 2020 (SOR/2020‑216) replaced:

|

(8) |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Off-road Compression-Ignition (Mobile and Stationary) and Large Spark-Ignition Engine Emission Regulations (SOR/2020‑258) replaced:

|

0 |

Cross-border Movement of Hazardous Waste and Hazardous Recyclable Material Regulations (SOR/2021‑25) replaced:

|

(2) | |

| Subtotal | (10) | |

| Total net impact on regulatory stock in the 2020–21 fiscal year | ||

| Department or agency | Regulation | Publication date | Exemption type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Affairs Canada | Order Amending the Import Control List (SOR/2020‑69) | April 29, 2020 | Non-discretionary obligations |

| Global Affairs Canada | Order Amending the Export Control List (SOR/2020‑70) | April 29, 2020 | Non-discretionary obligations |

| Global Affairs Canada | Regulations Amending Certain Regulations Made Under the Export and Import Permits Act (SOR/2020‑71) | April 29, 2020 | Non-discretionary obligations |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | Regulations Amending the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (Emergencies Act and Quarantine Act) (SOR/2020‑91) | April 24, 2020 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Department of Finance Canada | Regulations Amending the Income Tax Regulations (COVID‑19 — Deemed Remittance) (SOR/2020‑106) | May 27, 2020 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Department of Finance Canada | Regulations Amending the Income Tax Regulations (COVID‑19 — Eligible Entities) (SOR/2020‑107) | May 27, 2020 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Department of Finance Canada | Regulations Amending the Regulations Amending Certain Regulations Made Under the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act, 2019 (SOR/2020‑112) | June 10, 2020 | Non-discretionary obligations |

| Department of Finance Canada | Regulations Amending the Income Tax Regulations (COVID‑19 — June 7 to July 4, 2020 Qualifying Period) (SOR/2020‑160) | July 22, 2020 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Department of Finance Canada | United States Surtax Order (Aluminum 2020) (SOR/2020‑199) | September 30, 2020 | Tax or tax administration |

| Department of Finance Canada | Regulations Amending the Income Tax Regulations (COVID‑19 — Wage Subsidy for Furloughed Employees) (SOR/2020‑207) | October 14, 2020 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Department of Finance Canada | Regulations Amending the Income Tax Regulations, No. 2 (COVID‑19 — Wage Subsidy for Furloughed Employees) (SOR/2020‑227) | October 28, 2020 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Department of Finance Canada | Regulations Amending the Income Tax Regulations, No. 3 (COVID‑19 — Wage Subsidy for Furloughed Employees) (SOR/2020‑243) | November 25, 2020 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Department of Finance Canada | Regulations Amending the Income Tax Regulations (COVID‑19 — Wage and Rent Subsidies) (SOR/2020‑284) | January 6, 2021 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Public Safety Canada | Regulations Amending the Regulations Establishing a List of Entities (SOR/2020‑285) | January 6, 2021 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Public Safety Canada | Regulations Amending the Regulations Establishing a List of Entities (SOR/2021‑8) | February 17, 2021 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Health Canada | Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations (Interim Order Respecting the Importation, Sale and Advertising of Drugs for Use in Relation to COVID‑19) (SOR/2021‑45) | March 31, 2021 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

Appendix C: administrative burden count

| Department or agencytable C1 note * | 2014 (baseline count) | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requirements | Regulations | Requirements | Regulations | Requirements | Regulations | Requirements | Regulations | |

Table C1 Notes

|

||||||||

| Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada | 134 | 4 | 133 | 4 | 133 | 4 | 133 | 4 |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 1,426 | 30 | 1,473 | 30 | 1,274 | 30 | 1,284 | 31 |

| Canada Energy Regulator | 1,298 | 14 | 4,539 | 13 | 4,563 | 14 | 4,636 | 16 |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 1,776 | 30 | 1,808 | 31 | 1,824 | 30 | 1,824 | 31 |

| Canadian Dairy Commission | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Canadian Food Inspection Agency | 10,989 | 34 | 12,075 | 23 | 5,154 | 11 | 5,463 | 11 |

| Canadian Grain Commission | 1,056 | 1 | 1,056 | 1 | 1,056 | 1 | 1,056 | 1 |

| Canadian Heritage | 797 | 3 | 700 | 3 | 706 | 3 | 687 | 3 |

| Canadian Intellectual Property Office | 569 | 6 | 543 | 5 | 613 | 5 | 617 | 5 |

| Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission | 8,169 | 10 | 7,007 | 10 | 6,993 | 10 | 6,993 | 10 |

| Canadian Pari-Mutuel Agency | 731 | 2 | 731 | 2 | 731 | 2 | 731 | 2 |

| Canadian Transportation Agency | 545 | 7 | 545 | 7 | 545 | 7 | 432 | 7 |

| Competition Bureau Canada | 444 | 3 | 444 | 3 | 444 | 3 | 444 | 3 |

| Copyright Board Canada | 16 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 17 | 1 |

| Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canadatable C1 note † | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 247 | 11 | 247 | 11 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | 2,791 | 7 | 3,102 | 6 | 3,102 | 6 | 3,102 | 6 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 9,985 | 53 | 11,390 | 51 | 12,542 | 53 | 12,805 | 54 |

| Farm Products Council of Canada | 47 | 3 | 47 | 3 | 47 | 3 | 47 | 3 |

| Department of Finance Canada | 1,818 | 42 | 1,928 | 42 | 2,027 | 43 | 2,029 | 45 |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | 5,350 | 30 | 5,367 | 30 | 5,368 | 30 | 5,368 | 30 |

| Global Affairs Canada | 2,809 | 55 | 2,896 | 60 | 2,921 | 62 | 3,137 | 66 |

| Health Canada | 15,649 | 95 | 15,879 | 31 | 16,495 | 33 | 20,058 | 39 |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | 14 | 1 | 59 | 1 | 59 | 1 | 59 | 1 |

| Impact Assessment Agency of Canada | 89 | 1 | 89 | 1 | 206 | 1 | 325 | 2 |

| Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canadatable C1 note † | 288 | 12 | 288 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indigenous Services Canada† | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 148 | 1 | 148 | 1 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | 1,693 | 8 | 1,415 | 8 | 1,419 | 8 | 1,419 | 8 |

| Labour Program | 21,468 | 32 | 22,081 | 17 | 22,168 | 19 | 22,221 | 14 |

| Measurement Canada | 335 | 2 | 359 | 2 | 359 | 2 | 359 | 2 |

| Natural Resources Canada | 4,507 | 28 | 4,312 | 26 | 4,363 | 26 | 4,390 | 26 |

| Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy Canada | 799 | 4 | 799 | 3 | 799 | 3 | 799 | 3 |

| Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada | 2,875 | 33 | 2591 | 23 | 2,642 | 24 | 2,665 | 24 |

| Parks Canada | 773 | 25 | 773 | 25 | 773 | 25 | 773 | 25 |

| Patented Medicine Prices Review Board Canada | 59 | 1 | 59 | 1 | 59 | 1 | 59 | 1 |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | 42 | 2 | 189 | 2 | 189 | 2 | 189 | 2 |

| Public Safety Canada | 229 | 6 | 229 | 6 | 229 | 6 | 229 | 6 |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 388 | 1 | 498 | 1 | 498 | 1 | 498 | 1 |

| Statistics Canada | 157 | 1 | 157 | 1 | 157 | 1 | 157 | 1 |

| Transport Canada | 29,695 | 94 | 30,749 | 96 | 31,594 | 99 | 31,670 | 99 |

| Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat | 46 | 1 | 48 | 2 | 15 | 2 | 15 | 2 |

| Grand total | 129,860 | 684 | 136,379 | 585 | 132,483 | 586 | 137,089 | 599 |