Annual Report for the 2021 to 2022 Fiscal Year: Federal Regulatory Management Initiatives

On this page

- Message from the President of the Treasury Board

- Introduction

- Types of federal regulations

- The federal government’s response to COVID‑19

- Section 1: benefits and costs of regulations

- Section 2: implementation of the one-for-one rule

- Section 3: update on the Administrative Burden Baseline

- Section 4: regulatory modernization

- Appendix A: detailed report on cost-benefit analyses for the 2021–22 fiscal year

- Appendix B: detailed report on the one-for-one rule for the 2021–22 fiscal year

- Appendix C: administrative burden count

Message from the President of the Treasury Board

President of the Treasury Board

As the President of the Treasury Board and the Minister responsible for federal regulatory policy and oversight, I am pleased to present the sixth annual report on federal regulatory management initiatives.

This report provides a detailed analysis of benefits and costs in federal regulations, the one-for-one rule, and the Administrative Burden Baseline. It also provides an update on modernization initiatives that help promote competitiveness, agility, and innovation in the Canadian regulatory system.

Regulations can protect the environment, help keep people safe, and ensure social and economic wellbeing. For instance, regulations have played a critical role in the government’s ability to respond to global crises like the war in Ukraine and the COVID-19 pandemic. They play an important part in improving the lives of Canadians and the environment for businesses.

This year, we finalized the review of the Red Tape Reduction Act, better known as the “one-for-one rule”. The review concluded that the Act is working as intended to control the administrative burden from regulations on businesses. We also learned that more can be done to address cumulative regulatory burden, improve regulatory efficiency for stakeholders, and promote regulatory reviews to reduce costs and ensure continuous improvement.

We are continuing to work with stakeholders, including the External Advisory Committee on Regulatory Competitiveness, to adapt and improve our regulatory system, including finding new ways to support competitiveness, cross-border trade and supply chains. Based on the Advisory Committee’s advice, we are also exploring new ways to engage Canadians and Canadian businesses on cross-cutting regulatory issues such as by piloting the ‘Let’s Talk Federal Regulations’ platform. We will be using this platform to seek proposals for the next Annual Regulatory Modernization Bill – to identify overly complicated, inconsistent, or outdated legislative requirements that should change to make the regulatory system more efficient and effective.

The government will continue to ensure that Canada’s regulatory system is more responsive, easier to navigate, and promotes trade and innovation while still protecting Canadians’ health, safety, security, and the environment. I invite you to read this year’s report to learn more.

Original signed by

The Honourable Mona Fortier

President of the Treasury Board

Introduction

This is the sixth annual report on federal regulatory management initiatives. This report is part of regular monitoring of certain aspects of Canada’s regulatory system.

This year’s report has four main sections:

- Section 1 describes the benefits and costs of regulations that were made by the Governor in CouncilFootnote 1 and that have a significantFootnote 2 cost impact

- Section 2 reports on the implementation of the one-for-one rule, fulfilling the Red Tape Reduction Act reporting requirement

- Section 3 sets out the Administrative Burden Baseline for 2021 and for previous years, providing a count of administrative requirements in federal regulations

- Section 4 provides an update on regulatory modernization initiatives underway

The regulations reported on in this document were published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, in the 2021–22 fiscal year, which covers the period from April 1, 2021, to March 31, 2022.

Types of federal regulations

Regulations are a type of law intended to change behaviours and achieve public policy objectives. They have legally binding effect and support a broad range of objectives, such as:

- health and safety

- security

- culture and heritage

- a strong and equitable economy

- the environment

Regulations are made by every order of government in Canada in accordance with responsibilities set out in the Constitution Act. Federal regulations deal with areas of federal jurisdiction, such as patent rules, vehicle emissions standards and drug licensing.

The Cabinet Directive on Regulation (CDR) is the policy instrument that governs the federal regulatory system. There are three principal categories of federal regulations. Each is based on where the authority to make regulations lies as determined by Parliament when it enacts the enabling legislation:

- Governor in Council (GIC) regulations are reviewed by a group of ministers who recommend approval to the Governor General. This role is performed by the Treasury Board.

- Ministerial regulations are made by a minister who is given the authority to do so by Parliament; considerations such as impact, permanence and scope of the measures are taken into account when providing these authorities.

- Example: Subsection 28(2) of the Canadian Navigable Waters Act authorizes the Minister of Transport to make regulatory orders designating any works that are likely to interfere with navigation either slightly or substantially; this designation determines the requirements associated with those projects.

- Regulations made by an agency, tribunal or other entity that has been given the authority by law to do so in a given area, and that do not require the approval of the GIC or a minister.

- Example: Section 16(1) of the Canada Grain Act authorizes the Canadian Grain Commission to make regulations establishing grades and grade names for grain, specifications for those grades, and methods for determining the characteristics of the grain to meet the quality requirements of grain purchasers.

The federal government’s response to COVID‑19

The COVID‑19 pandemic is an extraordinary circumstance with unprecedented health and economic impacts, and the regulatory system has played a key role in the government’s response. The government has used a variety of regulatory tools to protect Canadians from the coronavirus and to manage the impacts of disruptions to the Canadian economy. Many of the proposals in this report addressed specific pandemic-related issues on an emergency basis.

The Treasury Board prioritized regulatory initiatives that directly addressed COVID‑19, while other regulatory business was deferred unless doing so would have significant legal or administrative implications or impacts on health, safety, security or the environment.

As well, recognizing the need for decision-making under tight time frames, the Treasury Board directed that the analytical requirements for priority initiatives could be modified if data or information were not available or if there was insufficient time or capacity to fulfill the standard requirements. This is permitted under section 5.5 of the Cabinet Directive on Regulation to address “exceptional measures.”

In practice, this meant that proposals with large resource implications could proceed with less detailed costing than usual, and other analytical requirements were relaxed.

Sections 1 and 2 of this report include further information on the modified analytical requirements and the specific regulations that were affected.

Section 1: benefits and costs of regulations

In this section

What is cost-benefit analysis?

In the regulatory context, cost-benefit analysis (CBA) is a structured approach to identifying and considering the economic, environmental and social effects of a regulatory proposal. CBA identifies and measures the positive and negative impacts of a regulatory proposal and any feasible alternative options so that decision-makers can determine the best course of action. CBA monetizes, quantifies and qualitatively analyzes the direct and indirect costs and benefits of the regulatory proposal to determine the proposal’s overall benefit.

Since 1986, the Government of Canada has required that a CBA be done for most regulatory proposals in order to assess their potential impact on areas such as:

- the environment

- workers

- businesses

- consumers

- other sectors of society

The results of the CBA are summarized in a Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS), which is published with proposed regulations in the Canada Gazette, Part I. The RIAS enables the public to:

- review the analysis

- provide comments to regulators before final consideration by the GIC and subsequent publication of approved final regulations in the Canada Gazette, Part II

Analytical requirements

The analytical requirements for CBA as part of a RIAS are set out in the Policy on Cost‑Benefit Analysis, which was introduced on September 1, 2018, in support of the Cabinet Directive on Regulation. The policy requires both robust analysis and public transparency, including:

- reporting stakeholder consultations on CBA in the RIAS

- making the CBA available publicly

Regulatory proposals are categorized according to their expected level of impact, which is determined by the anticipated cost of the proposal:

- no-cost-impact regulatory proposals: proposals that have no identified costs

- low-cost-impact regulatory proposals: proposals that have average annual national costs of less than $1 million

- significant‑cost‑impact regulatory proposals: proposals that have $1 million or more in average annual national costs

The level of impact determines the degree of analysis and assessment that is required for a given regulatory proposal. This proportionate approach is consistent with regulatory best practices set out by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Table 1 shows the minimum analytical requirements for each level of impact.

Table 1: minimum analytical requirements, by level of impact

| Impact level | Description of costs | Description of benefits |

|---|---|---|

| None | Qualitative statement that there are no anticipated costs | Qualitative |

| Low | Qualitative | Qualitative |

| Significant | Qualitative, quantified and monetized (if data are readily available) |

Qualitative, quantified and monetized (if data are readily available) |

In this report, information on CBA covers GIC regulations only and is limited to regulatory proposals that have a significant cost impact; since these proposals require that the majority of benefits and costs be monetized, the overall net impact can be described in economic terms more clearly than proposals with low or no costs, which rely more on qualitative or quantified analysis. These three types of analysis are described in detail later in Section 1.

Figures in this report are taken from the RIASs for regulations published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, in the 2021–22 fiscal year. To remove the effect of inflation, figures are expressed in 2012 dollars and, therefore, will vary from those published in the RIASs. This approach permits meaningful and consistent comparison of figures, regardless of the year in which regulatory impacts were originally measured.

Overview of benefits and costs of regulations

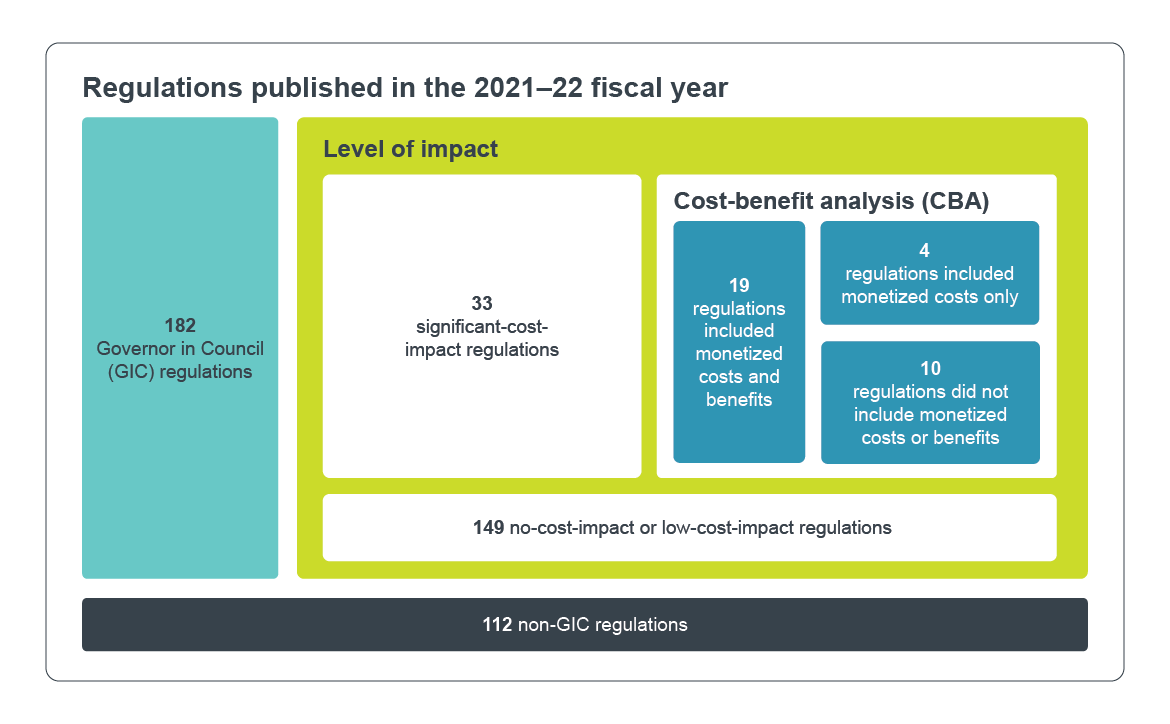

In the 2021–22 fiscal year, a total of 294 regulations were published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, compared with 305 in the 2020–21 fiscal year. Of these 294 regulations:

- 182 were GIC regulations (61.9% of all regulations)

- 112 were non-GIC regulations (38.1% of all regulations)

Of the 182 GIC regulations (compared with 187 in the 2020–21 fiscal year):

- 149 had no cost impact or low-cost impact (81.9% of GIC regulations)

- 33 had significant cost impact (18.1% of GIC regulations)

Figure 1 provides an overview of regulations approved and published in the 2021–22 fiscal year.

Figure 1 - Text version

Figure 1 provides an overview of the regulations published in the 2021-22 fiscal year.

During this period, 112 non-Governor in Council regulations were published, and 182 Governor in Council regulations were published.

Of the 182 Governor in Council regulations, 149 were no-cost-impact or low-cost-impact regulations, and 33 were significant-cost-impact regulations.

Of the 33 significant-cost-impact regulations, 19 included monetized costs and benefits, 4 included monetized costs only, and 10 did not include monetized costs or benefits.

Qualitative benefits and costs

The most basic element of any analysis of costs and benefits is a description of the expected impacts of the regulatory proposal. This description is based on a qualitative analysis and is used to:

- provide decision-makers with an evidence-based understanding of the anticipated impacts of the regulation

- provide context for further analysis that is expressed in numerical or monetary terms

Qualitative analysis should be part of the CBA of all regulatory proposals, including those that have no cost impact or low-cost impact.

The following are examples of qualitative impacts identified in significant‑cost‑impact regulations in the 2021–22 fiscal year:

- The Financial Consumer Protection Framework Regulations (SOR/2021-181) positively impact Canadians by making the complaint-handling process more transparent and accountable for consumers, who can have their complaints addressed by banks in a shorter period of time. In addition, the Regulations ensure consumers receive the information they need in a more timely manner regarding products and services about to be renewed or automatically renewed by requiring banks to disclose to the consumer 21 days in advance that a product is scheduled to be renewed and to send a reminder 5 days prior to the renewal date. Lastly, the Regulations also increase the maximum number of Government of Canada cheques that can be cashed free of charge, which allows Canadians to access funds without having to incur additional costs. These are concrete examples of measures aimed to empower and protect consumers when dealing with their banks.

- The Regulations Amending the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (Atlantic Immigration Class) (SOR/2021-242) have benefitted Canada by bringing immigrants with valuable skills to areas of the country that have traditionally been underserved by migration. The regulatory changes have been designed to increase retention of immigrants and employers in Atlantic provinces, and to benefit newcomers with increased support provided via mandatory settlement plans. The Atlantic Immigration Program also helps to support Canada’s reputation as a leader in immigration, and to maintain a welcoming and inclusive society that values cultural diversity.

- The Order Amending the Lockdown Regions Designation Order (COVID‑19) (SOR/2021-277) designated lockdown regions for the purposes of the Canada Worker Lockdown Benefit Act. Eligible workers in these designated lockdown regions were able to receive the Canada Worker Lockdown Benefit. The benefit provided indirect economic benefits arising from the spending of these income supports in the economy. This spending helped keep some self-employed individuals and businesses operational during and after the lockdown. These businesses would otherwise have experienced revenue loss or would have had to close. This in turn helped to accelerate the economic recovery coming out of the lockdown. Access to the additional income supports were also expected to have indirect societal impacts by reducing the risk of homelessness or childhood poverty.

Quantitative benefits and costs

Quantitative benefits and costs are those that are expressed as a quantity, for example:

- the number of recipients of a benefit

- the percentage reduction in pollution

- the amount of time saved

As is the case with qualitative information, quantitative benefits and costs can be used in two ways:

- on their own, they can illustrate the expected magnitude of a proposal by providing measurable figures to decision-makers

- they can be used as a factor in developing cost estimates

Quantitative analysis is an element of nearly all regulatory proposals that have a significant cost impact. Such analysis provides key metrics on the frequency or number of instances of an activity and is essential for estimating benefits and costs. Quantitative analysis can also be used on its own to illustrate the overall impact of a proposal in non-monetary terms. Although quantitative analysis is not required for proposals that have no cost impact or low-cost impact, it is often included alongside qualitative information because it can be useful to decision-makers.

The following are examples of quantified benefits and costs identified in significant‑cost‑impact regulations that were finalized in the 2021–22 fiscal year:

- The Regulations Amending the Canada Recovery Benefits Act and the Canada Recovery Benefits Regulation (SOR/2021-204) extended the periods during which recovery benefits were available and increased the maximum number of weeks of Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB) entitlement. A total of 2.1 million recipients were expected to directly benefit from the extension of the recovery benefits and the increase in weeks available for the CRB. Approximately 1.8 million recipients were expected to benefit from the extension and the additional four weeks of CRB, while an additional 300,000 claimants were expected to exhaust Employment Insurance (EI) benefits and be able to apply for the CRB.

- The Regulations Amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Parts I, III and VI — RESA) (SOR/2021-269) mandated the implementation of runway end safety areas (RESA) at each end of a runway serving scheduled commercial passenger-carrying flights at the busiest Canadian airports. The amendments aim to improve the safety of air travel by reducing the adverse consequences of runway undershoots and overruns, and align the regulations more closely with current International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) standards. It is projected that between 2021 and 2040, the amendments will reduce the severity of about six undershoots and overruns.

- The Accessible Transportation Planning and Reporting Regulations (SOR/2021-243) help provide persons with disabilities with equitable access to the Canadian transportation network so they can fully participate in the social and economic aspects of Canadian society. The Accessible Transportation Planning and Reporting Regulations (ATPRR) do this by ensuring that transportation service providers consider accessibility in the design, development and delivery of programs, policies and services, which helps to identify, remove, and prevent barriers to accessibility in the federal transportation network. The ATPRR created a set of requirements to develop accessibility plans, progress reports and feedback processes, and through consultation and the feedback received, they allow for the identification and removal of barriers to an accessible transportation network. Transportation service providers are also required to provide these documents in various accessible formats, upon request, so that persons with disabilities save time in reading and understanding the documents. Approximately 273,000 persons with disabilities are expected to benefit from alternate formats.

Monetized benefits and costs

Monetized benefits and costs are those that are expressed in a currency amount, such as dollars, using an approach that considers both the value of an impact and when it occurs.Footnote 3

An analysis of monetized costs and benefits is required for all regulatory proposals that have a significant cost impact. If the benefits or costs cannot be monetized, a rigorous qualitative analysis of the costs or benefits of the proposed regulation is required, and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) must be satisfied that there are legitimate obstacles to monetizing the impacts. In practice, most regulatory proposals with significant cost impacts include both monetized benefits and costs as part of the analysis.

For costs and benefits to be considered monetized, the dollar values used in a CBA are adjusted so that values and prices that occur at different times are equal:

- to their exchange value (inflation adjustment)

- when they occur (discounting)

Several proposals that were part of the government’s response to COVID‑19 were developed using modified analytical requirements. In the case of CBA, proposals identifying significant costs could state impacts qualitatively instead of monetizing them.

Of the 33 regulations with significant cost impacts that were finalized in the 2021–22 fiscal year, 23 of them had monetized impacts, representing 12.6% of GIC regulations. Of the 33 regulations:

- 19 had monetized benefits and costs

- 4 had monetized costs only

- 10 did not include monetized costs or benefits; of these, 8 were related to COVID‑19 and featured modified analytical requirements

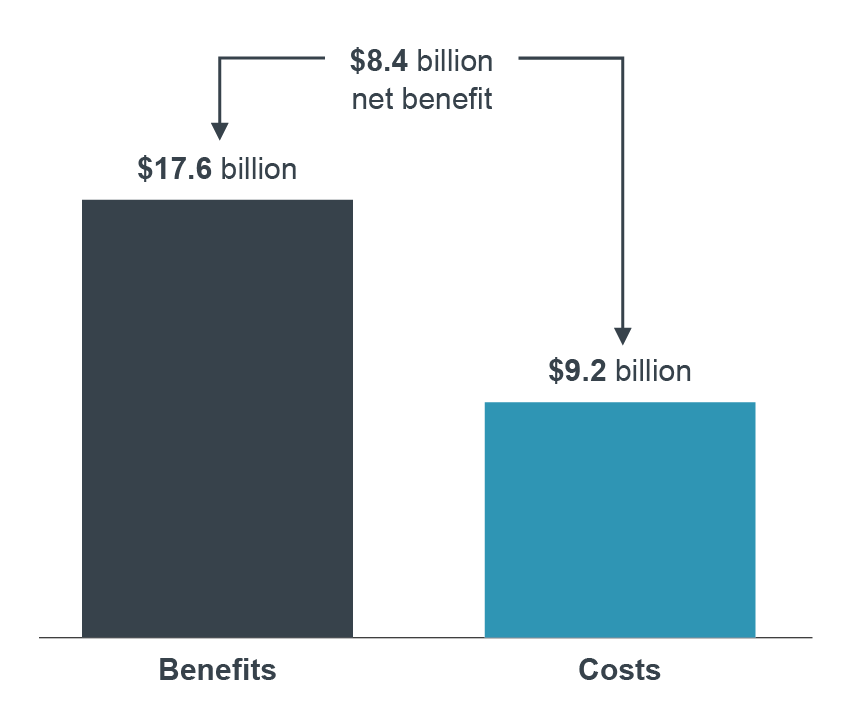

For the 19 regulations with significant cost impacts that had monetized estimates of both benefits and costs, expressed as total present value (see Figure 2):Footnote 4

- total benefits were $17,633,793,497

- total costs were $9,202,464,745

- net benefits were $8,431,328,752

Figure 2 - Text version

Figure 2 depicts the benefits and costs of significant-cost-impact regulations published in the 2021-22 fiscal year.

The benefits associated with significant-cost-impact regulations totalled $17.6 billion.

The costs associated with significant-cost-impact regulations totalled $9.2 billion.

The difference between the benefits and the costs is a net benefit of $8.4 billion.

The following three significant‑cost‑impact regulatory proposals had the greatest net benefit of all proposals that were finalized in the 2021–22 fiscal year and that had monetized benefits and costs:

- The Regulations Amending Certain Regulations Made Under the Canada Student Financial Assistance Act (SOR/2021-138) build on previously introduced measures to make post-secondary education more affordable and accessible to students facing financial challenges during the COVID‑19 pandemic. The regulations extended the doubling of Canada Student Grants for eligible full-time and part-time students, students with dependants and students with permanent disabilities until July 31, 2023. The regulations also extended the $1,600 adult learner top-up to the full-time Canada Student Grant until July 31, 2023. Finally, the amendments permanently allow applicants to use the current year’s income instead of the previous year’s income for determining eligibility for Canada Student Grants. These changes will result in a net benefit of $7,435,216,808 over 10 years.

- The Ballast Water Regulations (SOR/2021-120) give effect to Canada’s international obligations under the International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments, 2004. The measures reduce the environmental and economic impacts of invasive species introduced to Canadian waters through ballast water release. These changes are expected to result in a net benefit of $654,585,475 between 2021 and 2043.

- The Volatile Organic Compound Concentration Limits for Certain Products Regulations (SOR/2021-268) contribute to better air quality and help Canada meet its national and international commitments to lower and control emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOC) from products used by consumers for institutional, industrial and commercial applications. They establish VOC concentration limits for approximately 130 product categories and subcategories, including personal care products, automotive and household maintenance products, adhesives, adhesive removers, sealants and caulks, and other miscellaneous products. In total, these measures will result in a net benefit of $578,569,795 between 2022 and 2033.

The purpose of CBA is to determine whether the expected benefits of a proposal are greater than the expected costs. This determination, however, is not based entirely on monetized benefits and costs. CBAs frequently include quantitative and qualitative analysis, in addition to monetized analysis, and the overall analysis must consider this broader range of evidence. In the 2021–22 fiscal year:

- two regulations that had a significant cost impact had monetized costs that were equal to monetized benefits, a result that is usually associated with a direct transfer from one party to another

- eight regulations that had a significant cost impact had monetized costs that were greater than monetized benefits, which typically indicates that some benefits, such as broader societal benefits, could not be monetized and were stated qualitatively alongside benefits that were monetized

For detailed benefits and costs by regulation, see Appendix A.

Section 2: implementation of the one-for-one rule

The one-for-one rule

To comply with the annual reporting requirements of the Red Tape Reduction Act, this report also provides an update on the implementation of the one-for-one rule.

The one-for-one rule, which was instituted in the 2012–13 fiscal year, seeks to control the administrative burden that regulations impose on businesses.

Administrative burden includes:

- planning, collecting, processing and reporting of information

- completing forms

- retaining data required by the federal government to comply with a regulation

Under the rule, when a new or amended regulation increases the administrative burden on businesses, the cost of this burden must be offset through other regulatory changes. The rule also requires that an existing regulation be repealed each time a new regulation imposes new administrative burden on business.

The rule applies to all regulatory changes made or approved by the GIC or a minister that impose new administrative burden on business, including those with low cost impacts and significant cost impacts. Under the Red Tape Reduction Regulations, the Treasury Board can exempt three categories of regulations from the requirement to offset burden and regulatory titles:

- regulations related to tax or tax administration

- regulations where there is no discretion regarding what is to be included in the regulation (for example, treaty obligations or the implementation of a court decision)

- regulations made in response to emergency, unique or exceptional circumstances, including where compliance with the rule would compromise the Canadian economy, public health or safety

Regulators are required to monetize and report on:

- the change in administrative burden

- feedback from stakeholders and Canadians on regulators’ estimates of administrative burden costs or savings to business

- the number of regulations created or removed

As with CBA, the dollar values used in estimating administrative burden are adjusted so that values and prices that occur at different times are equal in their exchange value (inflation adjustment) and when they occur (discounting). In this report, all figures related to the one‑for‑one rule are expressed in 2012 dollars to permit meaningful and consistent comparison of regulations, regardless of the fiscal year in which they were introduced.

In 2015, the Red Tape Reduction Act enshrined the existing policy requirement for the one‑for‑one rule in law. Section 9 of the Red Tape Reduction Act requires that the President of the Treasury Board prepare and make public an annual report on the application of the rule.

The Red Tape Reduction Regulations state that the following must be included in the annual report:

- a summary of the increases and decreases in the cost of administrative burden that results from regulatory changes that are made in accordance with section 5 of the act within the 12‑month period ending on March 31 of the year in which the report is made public

- the number of regulations that are amended or repealed as a result of regulatory changes that are made in accordance with section 5 of the act within that 12‑month period

Key findings on the implementation of the one-for-one rule

The main findings on changes in administrative burden and the overall number of regulations for the 2021–22 fiscal year are as follows:

- system-wide, the federal government remains in compliance with the requirement in the Red Tape Reduction Act to offset administrative burden and titles within 24 months

- annual net administrative burden increased by $995,800 in the 2021–22 fiscal year; since the 2012–13 fiscal year, annual net burden has been reduced by approximately $59.5 million

- 18 regulatory titles (net) were taken off the books, with a total net reduction of 205 titlesFootnote 5 since the 2012–13 fiscal year

A detailed report on regulations that had implications under the one-for-one rule is in Appendix B.

Under the one-for-one rule, regulatory changes in the 2021–22 fiscal year resulted in the following increases and decreases in the cost of administrative burden on businesses:

- $1,013,654 of new burden introduced

- $17,854 of existing burden removed

- net increase of $995,800

The rule allows individual portfolios two years to offset any new burden introduced. As well, portfolios are allowed to bank burden reductions for future offsets within that portfolio. As a result, all of the $1,013,654 in new burden introduced in the 2021–22 fiscal year was immediately offset by previously removed burden.

The changes introduced by the following three final regulations represented the largest changes in administrative burden in the 2021‒22 fiscal year:

- The Regulations Amending Certain Regulations Made Under the Canada Labour Code (SOR/2022-41) implemented new provisions to the Canada Labour Code that support work-life balance and flexibility in federally regulated workplaces. Under the changes, employers are required to keep additional records related to hours of work and flexible work arrangements. It is estimated that the annualized administrative costs imposed on affected federally regulated employers will be $559,315.

- The Formaldehyde Emissions from Composite Wood Products Regulations (SOR/2021-148) reduce potential risks to the health of Canadians from exposure to formaldehyde by putting in place limits on allowable formaldehyde emissions from composite wood products. The regulations also aligned Canadian requirements for composite wood products with similar requirements in the U.S. to help create a level playing field for Canadian businesses. Administrative costs include small chamber equivalency testing, third-party certification, labelling, record keeping, training/familiarization with the regulatory requirements, self-identifying as regulatees and providing contact information to the departments, and preparing and submitting reports to the departments on demand. The annualized average increase in administrative burden on businesses is $145,051.

- The Regulations Amending the Canada Occupational Health and Safety Regulations (Part XI) (SOR/2021-143) protect the health and safety of employees working in confined spaces in workplaces under federal jurisdiction. The amendments require employers to maintain a record of confined spaces, add new requirements to the hazard assessment report, and retain records of confined spaces training. These requirements are expected to add approximately $83,266 in additional administrative costs per year to affected sectors.

Under the one-for-one rule, regulatory changes in the 2021–22 fiscal year resulted in the following increases and decreases in the stock of federal regulations:

- 6 new regulatory titles imposing administrative burden on business were introduced

- 10 regulatory titles were repealed

- 17 existing titles were repealed and replaced with 3 new titles

While nine new titles were introduced over the course of the year, the rule allows individual portfolios two years to offset these titles. As is the case with administrative burden, portfolios are allowed to bank title repeals for future offsets within the portfolio. As a result, most of these new titles have already been offset:

- six were offset immediately by previously removed titles

- three were not yet offset as of March 31, 2022

The Treasury Board monitors regulators’ compliance with the requirement to offset new administrative burden and titles. System-wide, the federal government remains in compliance with the requirement in the Red Tape Reduction Act to offset new administrative burden and titles within 24 months.

TBS also tracks offsetting requirements by portfolio. As of March 31, 2022, Fisheries and Oceans Canada had an outstanding amount of $24,333 of burden that had exceeded the 24‑month period for offsetting; this situation has been reported in previous annual reports.

Of this outstanding balance, $23,190 relates to the Aquaculture Activities Regulations (SOR/2015-177), which were registered on June 29, 2015. The regulations introduced $409,513 in administrative burden on business, of which the department offset $151,761 prior to 2020–21. A further $234,562 was offset in 2020–21 by the Regulations Amending Certain Regulations Made Under the Fisheries Act (SOR/2020‑255).

The outstanding balance also includes $738 related to the Regulations Amending the Marine Mammal Regulations (SOR/2018-126), and $173 related to the Banc-des-Américains Marine Protected Area Regulations (SOR/2019-50), which exceeded the 24-month reconciliation deadline in 2020–21.

During the 2021–22 fiscal year, the Authorizations Concerning Fish and Fish Habitat Protection Regulations(SOR/2019-286) surpassed the 24-month period for offsetting the $232 in administrative burden it introduced in 2019. This regulation also introduced one new regulatory title, which has not yet been offset and is also beyond the 24-month timeframe.

Officials from TBS and from Fisheries and Oceans Canada continue to work together to identify opportunities to achieve these outstanding offsets.

In the 2021–22 fiscal year, the Treasury Board approved the exemption of six regulations from the requirement to offset burden and titles:

- one was related to tax and tax administration

- none were related to non-discretionary obligations

- five were related to emergency, unique or exceptional circumstances

The total number of exemptions in 2021–22 is lower relative to previous years. As well, the number of exemptions related to emergency, unique or exceptional circumstances is proportionately higher since proposals related to COVID‑19 typically cited “emergency circumstances” to justify exemption.

Figure 3 - Text version

Figure 3 provides an overview of the implementation of the one-for-one rule for regulations published in the 2021-22 fiscal year.

There were 9 new regulations added and 27 regulations repealed, resulting in 18 fewer regulations in the regulatory stock.

There were 6 exemptions to the one-for-one rule, including 1 exemption for tax or tax administration, 0 non-discretionary obligations, and 5 emergency, unique or exceptional circumstances.

In total, 19 regulations increased burden by $1,013,654, and 5 regulations decreased burden by $17,854, for a net increase of $995,800 in administrative burden costs.

In April 2020, the Government of Canada initiated a legislated review of the Red Tape Reduction Act. The internal review found that while the one‑for‑one rule is working, administrative burden and other costs can be further reduced by promoting the review of regulations. It highlighted stakeholder views on the scope of the rule and policy areas to explore in the future. This includes addressing cumulative regulatory burden and reducing regulatory administrative burden on individuals and organizations, not just on businesses. A summary of the review and its findings will be published in a report online shortly.

Section 3: update on the Administrative Burden Baseline

In this section

The Administrative Burden Baseline

The Administrative Burden Baseline (ABB) provides Canadians with a count of the total number of administrative requirements on businesses in all federal regulations (GIC and non-GIC) and associated forms.

For the purposes of the ABB, an administrative requirement is a compulsion, obligation, demand or prohibition placed on a business, its activities or its operations through a GIC or non-GIC regulation. A requirement may also be thought of as any obligation that a business must satisfy to avoid penalties or delays. Regulatory requirements generally use directive words or phrases such as “shall,” “must,” and “is to,” and the ABB counts these references in the regulatory text or other documents.

The ABB was first publicly reported on in September 2014, providing a baseline count of administrative requirements by regulator. Since then, regulators continue to:

- do a count of their administrative requirements occurring from July 1 to June 30 each year

- publicly post updates to their ABB count by September 30 each year

Key findings on the Administrative Burden Baseline

The baseline provides Canadians with information on 39 regulators that are responsible for GIC and non-GIC regulations that contain administrative requirements on business.

As of June 30, 2021:

- the total number of administrative requirements was 150,569, an increase of 13,480 (or 9.83%) from the 2020 count of 137,089

- there were 604 regulations identified by regulators as having administrative requirements, an increase of 5 (or 0.83%) from the 2020 figure of 599

- the average number of administrative requirements per regulation was 249.3, an increase of 20.4 (or 8.9%) from the 2020 average of 228.9

The top three changes in the ABB in 2021 were:

- The Labour Program’s 2021 count increased by 9,150 requirements, largely due to amendments to the Employment Equity Regulations, which included significant changes to Employment Equity forms. However, despite the increased number of individual requirements, the changes reduced overall administrative costs to employers by streamlining salary calculation methodology and allowing the forms to be populated automatically using the Workplace Equity Information Management System tool.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada’s count increased by 4,047 requirements, mainly in relation to monitoring, record-keeping and reporting introduced under the Reduction in the Release of Volatile Organic Compounds Regulations (Petroleum Sector).

- The Canada Energy Regulator’s count increased by 545 requirements as a result of updates made to the web-based Online Event Reporting System (OERS) and Electronic Document Submission System. The majority of the increases are found in the Online Event Reporting System’s Damage to Pipe Report and Unauthorized Activities Report, which were updated to clarify the information required in these reporting forms. The OERS is an interactive reporting system that provides companies with greater clarity and efficiency in reporting, as well as a single window for reporting events to the CER and the Transportation Safety Board (as applicable).

A detailed summary of the ABB count for 2021 and for previous years can be found in Appendix C.

Section 4: regulatory modernization

In this section

This year regulators reflected on what was learned from the pandemic to inform ways to further improve the competitiveness, agility, efficiency and innovation of the Canadian federal regulatory system.

TBS partially relies on the OECD for insights on internationally recognized Good Regulatory Practices and lessons learned from other jurisdictions. These best practices are reflected in the CDR and Canada’s federal regulatory oversight approach. Every three years, the OECD conducts a comprehensive survey of practices of its 38 member countries and the European Union (39 total jurisdictions). TBS uses the results to situate Canada’s approach among its peers and identify opportunities for improvement. In 2021, the OECD’s Policy Outlook Report ranked Canada:

- 5th for regulatory impact analysis, down from 4th in 2018

- 3rd for stakeholder engagement, no change from 2018

- 6th for regulatory ex-post review, down from 5th in 2018

These scores indicate that Canada is strong in its approach to stakeholder engagement and regulatory impact analysis; however, more can be done, particularly to strengthen ex-post review. The legislated review of the Red Tape Reduction Act also echoed the importance of reviewing regulations to ensure they remain relevant, efficient, and effective. Improving performance in this area will be a key policy focus in the year ahead.

Strengthening transparency and participation in the regulatory system

Last year’s report highlighted a project being carried out in response to calls from Canadian stakeholders and trade partners to enhance transparency of regulatory consultations, including the proactive release of public comments on regulatory proposals. As committed to in the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA), a new commenting feature on Canada Gazette, Part I, (CG I) was launched in April 2021, which allows stakeholders to review proposed regulations and submit their comments directly on the CG I web page. This feature was tested on over 25 regulations through 2021–22 and became mandatory for all regulations pre-published in CG I as of September 27, 2022. These changes to the Canada Gazette make it easier to comment on draft regulations and improve the transparency of Canada’s regulatory process.

To further engage stakeholders, in 2021–22, preparations were made to launch a second External Advisory Committee on Regulatory Competitiveness (EACRC) with new members and a new mandate. The second EACRC brings together business, academic, civil society and consumer representatives to provide an independent perspective on promoting and advancing regulatory excellence. It will continue to help ministers and regulators modernize Canada’s regulatory system to create one that protects health, security, safety, and the environment while supporting economic growth and innovation. The second iteration of the committee, which launched in fall 2022, is mandated to provide advice on lessons learned from the COVID‑19 pandemic, policy/guidance on regulatory stock reviews, and updates to the CDR and monitor guidance on the advancement of recommendations made by the previous committee.

External Advisory Committee on Regulatory Competitiveness advice in action

The EACRC identified cumulative burden as a key issue facing the Canadian regulatory system. It recommended measuring the cumulative burden of one or more sectors as a first step to understand the aggregate net impact of all regulations and regulatory practices on that sector. Following a review of existing measurement methodologies, TBS worked on a proof of concept for a binary method, which uses yes/no questions to measure cumulative burden and compare that burden across jurisdictions. Further work is needed to determine whether this methodology can be scaled up and automated for use across the entire regulatory system.

Case Study: Trying New Ways to Improve Regulator-Stakeholder Collaboration

As part of the Agri-food and Aquaculture RoadmapFootnote 6 commitments, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada (AAFC) launched the Agile Regulations Table (ART) – an innovative forum that provides a wide range of industry stakeholders and government organizations a platform to come together and address horizontal and systemic regulatory issues facing the agriculture and agri-food sector. Since the completion of its strategic plan in fall 2021, the ART has committed to three areas of focus: improving navigability of regulations and building a shared understanding of regulatory pathways; reducing cumulative regulatory burden through the application of journey mapping to guide process improvements; and readying the regulatory system for the future through foresight and regulatory experimentation.

Through this table, members analyzed regulatory flexibilities used during the pandemic and discussed how they could shape longer-term improvements. They also developed a journey mapping toolkitFootnote 7 to further engage industry to identify ways to reduce cumulative regulatory burden, and started two regulatory experiments, looking at filling plant protein regulatory gaps and examining drone-based pesticide application. While it can be difficult to reach common ground when members may have opposing views, varying levels of commitment and special interests, the ART’s early achievements are proof that these challenges can be overcome. This innovative model promises to shape the way governments collaborate and bridge gaps with stakeholders in the future.

Improving regulatory efficiency through cross-border cooperation

Regulatory cooperation is one of many tools that the government uses to improve efficiency and competitiveness in the regulatory system. Federal regulators cooperate with regulators across borders to:

- reduce unnecessary regulatory differences

- eliminate duplicative requirements and processes

- harmonize or align regulations

- share information and experiences

- foster innovation and collaboration

- adopt international standards

As of 2021-22, the federal government has advanced 42 reconciliation items through three formal regulatory cooperation forums:

- 21 workplans through the Canada-United States Regulatory Cooperation Council established in 2011

- 5 workplans through the Canada-European Union Regulatory Cooperation Forum, established in 2018 under the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic Trade Agreement

- 16 workplan items through the Regulatory Reconciliation and Cooperation Table, established in 2017 between the federal government and all provinces and territories under the Canadian Free Trade Agreement.

This year the federal government also approved the first work programme under Agile Nations, a forum established in November 2020 for countries to collaborate on common regulatory innovation priorities. Members include Canada, Denmark, Italy, Japan, Singapore, the United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom. As part of the first work programme, Canada is working with Agile Nations partners to address issues ranging from cyber security and digital technologies to the use of regulatory experimentation. These projects involve sharing ideas, testing new solutions and identifying opportunities for regulators to better support innovative industries in introducing and scaling new technologies.

Through these different forums, regulators identify opportunities for cooperation and commit to workplans that advance their cooperation goals. Workplans are kept up to date online at Canada’s regulatory cooperation web page and on the Agile Nations web page.

Strengthening capacity to understand and leverage innovation

Traditional regulatory approaches have struggled to keep pace with a rapidly changing regulatory environment, with new technologies and disruptive events requiring flexibility and agile responses.

The Centre for Regulatory Innovation (CRI) provides tools, advice and funding to help federal regulators try new approaches to better understand and respond to new challenges.

Regulatory experiments, for example, allow regulators to test new technologies and different regulatory approaches. Regulators can use experiments to better understand how a new technology fits into their regulatory framework and identify what works and what does not. The evidence collected from these experiments then enables regulators to design and administer effective regulatory regimes with the impacts of this new technology in mind. This process helps regulators to be more responsive to new products and environments, and helps industry bring innovation into the marketplace – ultimately improving regulatory outcomes for Canadians.

This year, the CRI worked with Nesta, a global innovation firm, to develop a toolkit to provide Canadian regulators with a practical guide on how to design and carry out regulatory experiments. The CRI continues to work directly with regulators to help identify and implement new experiments.

Case study: light sport aircraft in a pilot training environment

Transport Canada is implementing a regulatory sandbox – a type of regulatory experiment – to test the use of light sport aircraft for training pilots.

As current regulations do not allow for this practice, creating a regulatory sandbox in partnership with select flight schools will allow Transport Canada to assess whether light sport aircraft can perform effectively in a pilot training environment. A sandbox will also allow for the identification of associated environmental and economic impacts relative to current aircraft. For example, Transport Canada will assess factors ranging from reliability and training quality to emissions, noise and cost.

The evidence gathered from this experiment will support Transport Canada’s determination of whether permanent regulatory change is needed, and if so, inform what the changes should look like.

Enabling the modernization of regulations through legislative change

Outdated regulatory frameworks are sometimes the result of duplicative or overly rigid legislation. For example, outdated rules can prevent a regulator from adopting a new approach or technology, such as requiring a hand-signed document instead of allowing a digital signature. The Annual Regulatory Modernization Bill (ARMB) aims to modernize select legislation to remove legal irritants that impact the regulatory framework.

On March 31, 2022, the second ARMB was introduced in the Senate as Bill S-6, an Act Respecting Regulatory Modernization. Bill S-6 makes common sense changes to 28 acts through 45 amendments, and addresses issues raised by businesses and Canadians about overly complicated, inconsistent or outdated requirements. For example, the bill proposes to allow the Canadian Food Inspection Agency to administer acts electronically, providing faster service and reducing administrative costs. Other amendments in Bill S-6 would:

- reduce the administrative burden for businesses

- make digital interactions with government easier

- simplify regulatory processes

- make exemptions from certain regulatory requirements to test new products

- make cross-border trade easier through more consistent and coherent rules across governments

Bill S-6 passed Third Reading in the Senate in June 2022 and is currently set for Second Reading in the House of Commons.

Appendix A: detailed report on cost-benefit analyses for the 2021–22 fiscal year

Figures in this appendix are taken from the RIASs in final federal regulations published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, in the 2021–22 fiscal year. To remove the effect of inflation, figures are expressed in 2012 dollars and vary from those published in the RIASs.

Table A1 lists GIC regulations finalized in the 2021–22 fiscal year that had significant cost impacts and that included both monetized benefits and monetized costs. These regulations may also include quantitative and qualitative data from a cost‑benefit analysis (CBA) to supplement the monetized CBA.

| Department or agency | Regulation | Benefits (total present value) | Costs (total present value) | Net present value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada Revenue Agency | Disability Tax Credit Promoters Restrictions Regulations (SOR/2021-55) | $85,055,772 | $85,055,772 | $0 |

| Transport Canada | Ballast Water Regulations (SOR/2021-120) | $916,343,137 | $261,757,661 | $654,585,475 |

| Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat | Regulations Amending the Public Service Superannuation Regulations (SOR/2021-136) | $82,326,471 | $82,326,471 | $0 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | Regulations Amending Certain Regulations Made Under the Canada Student Financial Assistance Act (SOR/2021-138) | $10,633,279,661 | $3,198,062,853 | $7,435,216,808 |

| Labour Program | Pay Equity Regulations (SOR/2021-161) | $1,483,934,632 | $1,457,914,456 | $26,020,176 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | Regulations Amending the Canada Labour Standards Regulations (SOR/2021-163)

|

$1,239,431,992 | $1,251,980,155 | -$12,548,164 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Order Amending Part 2 of Schedule 1 to the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act (SOR/2021-195) | $115,481,752 | $214,529,562 | -$99,047,810 |

| Labour Program | Regulations Amending the Wage Earner Protection Program Regulations (SOR/2021-196) | $59,759,143 | $53,548,751 | $6,210,392 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | Regulations Amending the Canada Recovery Benefits Act and the Canada Recovery Benefits Regulations (SOR/2021-204) | $1,833,321,116 | $1,872,082,910 | -$38,761,794 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | Regulations Amending the Canada Recovery Benefits Act (SOR/2021-219) | $222,600,989 | $233,000,494 | -$10,399,506 |

| Transport Canada | Regulations Amending the Grade Crossings Regulations (SOR/2021-233) | $98,399,336 | $216,777,015 | -$118,377,679 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | Accessible Canada Regulations (SOR/2021-241) | $65,972,138 | $20,779,380 | $45,192,758 |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | Regulations Amending the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (Atlantic Immigration Class) (SOR/2021-242) | $1,142,539 | $20,379,029 | -$19,236,490 |

| Canadian Transportation Agency | Accessible Transportation Planning and Reporting Regulations (SOR/2021-243) | $1,803,594 | $1,014,761 | $788,833 |

| Natural Resources Canada | Canada–Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Area Occupational Health and Safety Regulations (SOR/2021-247)

|

$3,467,071 | $1,158,744 | $2,308,327 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Volatile Organic Compound Concentration Limits for Certain Products Regulations (SOR/2021-268) | $787,049,001 | $208,479,207 | $578,569,795 |

| Transport Canada | Regulations Amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Parts I, III and VI — RESA) (SOR/2021-269) | $4,425,155 | $23,617,525 | -$19,192,370 |

| Totaltable 1 note * | $17,633,793,497 | $9,202,464,745 | $8,431,328,752 | |

Table 1 Notes

|

||||

Table A2 lists GIC regulations finalized in the 2021–22 fiscal year that had significant cost impacts and that included monetized costs but not monetized benefits. If it is not possible to quantify the benefits or costs of a proposal that has significant cost impacts, a rigorous qualitative analysis of costs or benefits of the proposed regulation is required, with the concurrence of TBS.

| Department or agency | Regulation | Costs (total present value) |

|---|---|---|

| Health Canada | Nicotine Concentration in Vaping Products Regulations (SOR/2021-123) | $404,483,512 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Formaldehyde Emissions from Composite Wood Products Regulations (SOR/2021-148) | $9,548,596 |

| Department of Finance Canada | Financial Consumer Protection Framework Regulations (SOR/2021-181) | $17,377,351 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Emergency Order for the Protection of the Western Chorus Frog Great Lakes / St. Lawrence — Canadian Shield Population (Longueuil)(SOR/2021-231) | $37,644,492 |

| Totaltable 2 note * | $468,963,950 | |

Table 2 Notes

|

||

Table A3 lists GIC regulations finalized in the 2021–22 fiscal year that had significant cost impacts and that did not include monetized benefits and costs.

Appendix B: detailed report on the one-for-one rule for the 2021–22 fiscal year

| Department or agency | Regulation | Net title change |

|---|---|---|

| New regulatory titles that have administrative burden | ||

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Formaldehyde Emissions from Composite Wood Products Regulations (SOR/2021-148) | 1 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | Accessible Canada Regulations (SOR/2021-241) | 1 |

| Canadian Transportation Agency | Accessible Transportation Planning and Reporting Regulations (SOR/2021-243) | 1 |

| Natural Resources Canada | Canada–Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Area Occupational Health and Safety Regulations (SOR/2021-247) | 1 |

| Natural Resources Canada | Canada–Nova Scotia Offshore Area Occupational Health and Safety Regulations (SOR/2021-248) | 1 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | Volatile Organic Compound Concentration Limits for Certain Products Regulations (SOR/2021-268) | 1 |

| Subtotal | 6 | |

| Repealed regulatory titles | ||

| Indigenous Services Canada | First Nations Election Cancellation and Postponement Regulations (Prevention of Diseases) (SOR/2020-84) repealed:

Note: these regulations included a provision that repealed them automatically on the first anniversary of their coming info force (April 8, 2021) and did not require a separate repealing instrument. |

(1) |

| Department of Finance Canada | Order Repealing the United States Surtax Order (Aluminum 2020) (SOR/2021-112) repealed:

Note: the repealed regulation was exempted from the requirement to offset under the one-for-one rule when it was initially introduced. The title repeal is not counted as per the Policy on Limiting Regulatory Burden on Business. |

0 |

| Transport Canada | Regulations Repealing Certain Regulations Made Under the Pilotage Act (Tariff Regulations — Miscellaneous Program) (SOR/2021-119) repealed:

|

(4) |

| Department of Finance Canada | Regulations Repealing the NAFTA Rules of Origin Regulations (SOR/2021-145) repealed:

|

(1) |

| Department of Finance Canada | Canadian Payments Association By-law No. 9 — Lynx (SOR/2021-182) repealed:

Note: The one-for-one rule section of the RIAS did not indicate that the repeal of the regulatory title would be counted as a title out under element B of the one-for-one rule. It has been counted as a title out despite this omission. |

(1) |

| Health Canada | Order Repealing the Establishment Licence Fees Remission Order (Indication of an Activity in respect of a COVID‑19 Drug) (SOR/2021-274) repealed:

|

(1) |

| Global Affairs Canada | Order Cancelling Certain Permits Issued Under the Export and Import Permits Act (Miscellaneous Program) (SOR/2021-280) repealed:

Note: The one-for-one rule section of the RIAS did not indicate that the repeals of the regulatory titles would be counted as titles out under element B of the one-for-one rule. They have been counted as a title out despite this omission. |

(2) |

| Natural Resources Canada | The Offshore Health and Safety Act (2014, c. 13) repealed:

Note: When these transitional regulations were introduced in 2015, the one-for-one rule was a policy requirement and not yet legislated under the Red Tape Reduction Act and its Regulations. The rule was not applied because the regulations were transitional, although it was intended that the rule would be applied to the eventual permanent regulations. Because these new titles were not counted as titles “in,” they are not counted as titles “out” upon repeal. |

0 |

| Subtotal | (10) | |

| New regulatory titles that simultaneously repealed and replaced existing titles | ||

| Transport Canada | Ballast Water Regulations (SOR/2021-120) replaced:

|

0 |

| Transport Canada | Vessel Safety Certificates Regulations (SOR/2021-135) replaced:

|

(2) |

| Department of Finance Canada | Financial Consumer Protection Framework Regulations (SOR/2021-181) replaced:

|

(12) |

| Subtotal | (14) | |

| Total net impact on regulatory stock in the 2021–22 fiscal year | (18) | |

| Department or agency | Regulation | Publication date | Exemption type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Department of Finance Canada | Regulations Amending the Income Tax Regulations (COVID‑19 — Wage and Rent Subsidies Periods 14 to 16)(SOR/2021-56) | April 14, 2021 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Public Safety Canada | Regulations Amending the Regulations Establishing a List of Entities (SOR/2021-169) | July 21, 2021 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Department of Finance Canada | Regulations Amending the Income Tax Regulations (COVID‑19 — Prior Reference Periods for Wage Subsidy, Rent Subsidy and Hiring Program and Subsidies Extension) (SOR/2021-206) | September 1, 2021 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Department of Finance Canada | Regulations Amending the Income Tax Regulations (COVID‑19 — Twenty-Second Qualifying Period) (SOR/2021-240) | December 22, 2021 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Department of Finance Canada | Regulations Amending the Income Tax Regulations (COVID‑19 — Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Fifth Qualifying Periods) (SOR/2022-11) | February 16, 2022 | Tax or tax administration |

| Health Canada | Clinical Trials for Medical Devices and Drugs Relating to COVID‑19 Regulations (SOR/2022-18) | March 2, 2022 | Emergency, unique or exceptional circumstance |

| Department or agency | Regulation | Net title change |

|---|---|---|

| Transport Canada | Regulations Maintaining the Safety of Persons in Ports and the Seaway (SOR/2020-54) repealed automatically on June 30, 2020 | (1) |

| Canadian Transportation Agency | Accessible Transportation for Persons with Disabilities Regulations Application Exemption Order (SOR/2020-125) repealed automatically on January 1, 2021 | (1) |

Appendix C: administrative burden count

| Department or agencytable 8 note 1 | 2014 (baseline count) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requirements | Regulations | Requirements | Regulations | Requirements | Regulations | Requirements | Regulations | |

| Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada | 134 | 4 | 133 | 4 | 133 | 4 | 133 | 4 |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 1,426 | 30 | 1,274 | 30 | 1,284 | 31 | 1,284 | 31 |

| Canada Energy Regulator | 1,298 | 14 | 4,563 | 14 | 4,636 | 16 | 5,181 | 16 |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 1,776 | 30 | 1,824 | 30 | 1,824 | 31 | 1,824 | 31 |

| Canadian Dairy Commission | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Canadian Food Inspection Agency | 10,989 | 34 | 5,154 | 11 | 5,463 | 11 | 5,174 | 11 |

| Canadian Grain Commission | 1,056 | 1 | 1,056 | 1 | 1,056 | 1 | 1,053 | 1 |

| Canadian Heritage | 797 | 3 | 706 | 3 | 687 | 3 | 684 | 3 |

| Canadian Intellectual Property Office | 569 | 6 | 613 | 5 | 617 | 5 | 592 | 5 |

| Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission | 8,169 | 10 | 6,993 | 10 | 6,993 | 10 | 6,993 | 10 |

| Canadian Pari-Mutuel Agency | 731 | 2 | 731 | 2 | 731 | 2 | 557 | 2 |

| Canadian Transportation Agency | 545 | 7 | 545 | 7 | 432 | 7 | 458 | 8 |

| Competition Bureau Canada | 444 | 3 | 444 | 3 | 444 | 3 | 444 | 3 |

| Copyright Board Canada | 16 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 17 | 1 |

| Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canadatable 8 note 2 | 0 | 0 | 247 | 11 | 247 | 11 | 244 | 11 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | 2,791 | 7 | 3,102 | 6 | 3,102 | 6 | 3,122 | 6 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 9,985 | 53 | 12,542 | 53 | 12,805 | 54 | 16,852 | 56 |

| Farm Products Council of Canada | 47 | 3 | 47 | 3 | 47 | 3 | 47 | 3 |

| Department of Finance Canada | 1,818 | 42 | 2,027 | 43 | 2,029 | 45 | 2029 | 45 |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | 5,350 | 30 | 5,368 | 30 | 5,368 | 30 | 5,370 | 30 |

| Global Affairs Canada | 2,809 | 55 | 2,921 | 62 | 3,137 | 66 | 3,149 | 67 |

| Health Canada | 15,649 | 95 | 16,495 | 33 | 20,058 | 39 | 20,526 | 40 |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | 14 | 1 | 59 | 1 | 59 | 1 | 59 | 1 |

| Impact Assessment Agency of Canada | 89 | 1 | 206 | 1 | 325 | 2 | 325 | 2 |

| Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canadatable 8 note 2 | 288 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indigenous Services Canadatable 8 note 2 | 0 | 0 | 148 | 1 | 148 | 1 | 148 | 1 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada | 1,693 | 8 | 1,419 | 8 | 1,419 | 8 | 1,388 | 8 |

| Labour Program | 21,468 | 32 | 22,168 | 19 | 22,221 | 14 | 31,371 | 20 |

| Measurement Canada | 335 | 2 | 359 | 2 | 359 | 2 | 359 | 2 |

| Natural Resources Canada | 4,507 | 28 | 4,363 | 26 | 4,390 | 26 | 4,390 | 26 |

| Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy Canada | 799 | 4 | 799 | 3 | 799 | 3 | 799 | 3 |

| Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada | 2,875 | 33 | 2,642 | 24 | 2,665 | 24 | 2618 | 24 |

| Parks Canada | 773 | 25 | 773 | 25 | 773 | 25 | 773 | 25 |

| Patented Medicine Prices Review Board Canada | 59 | 1 | 59 | 1 | 59 | 1 | 63 | 2 |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | 42 | 2 | 189 | 2 | 189 | 2 | 189 | 2 |

| Public Safety Canada | 229 | 6 | 229 | 6 | 229 | 6 | 229 | 6 |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 388 | 1 | 498 | 1 | 498 | 1 | 498 | 1 |

| Statistics Canada | 157 | 1 | 157 | 1 | 157 | 1 | 157 | 1 |

| Transport Canada | 29,695 | 94 | 31,594 | 99 | 31,670 | 99 | 31,453 | 93 |

| Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat | 46 | 1 | 15 | 2 | 15 | 2 | 13 | 1 |

| Grand total | 129,860 | 684 | 132,483 | 586 | 137,089 | 599 | 150,569 | 604 |

Table 8 Notes

|

||||||||

© His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, represented by the President of the Treasury Board, 2022,

Catalogue No.BT1-51E-PDF, ISSN: 2561-4290