2012 Report on the State of Comptrollership in the Government of Canada

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada,

represented by the President of the Treasury Board, 2012

ISBN BT66-15/2012E-PDF

This document is available in alternative formats upon request.

Table of Contents

- Part I: Report on the State of Comptrollership in the Government of Canada

- Message From the Comptroller General of Canada

- Overview of the State of Comptrollership in the Government of Canada

- Office of Comptroller General of Canada: Highlights of Accomplishments in 2011–12 and Priorities for 2012–13

- Part II: Three Research Papers on Aspects of Comptrollership in Canada

- Sustaining the Chief Financial Officer Suite: The Case for a Community-Based Approach to Chief Financial Officer Talent Management and Succession Planning

- Oversight in the Government of Canada: An Overview of Assurance Providers

- Life-Cycle Management of Real Property Assets and Public-Private Partnerships

Part I: Report on the State of Comptrollership in the Government of Canada

Message From the Comptroller General of Canada

I am pleased to present this Report on the State of Comptrollership in the Government of Canada.

My first report (March 2011) provided a comprehensive look at the health of financial management, internal audit, and the management of assets and acquired services in the federal government. This second report provides an update of the performance of government comptrollership functions and highlights progress made in advancing the priorities and challenges identified in last year's report. This report also focuses on three key aspects of comptrollership in Canada:

- Sustaining the chief financial officer suite: The case for a community-based approach to chief financial officer talent management and succession planning;

- Oversight in the Government of Canada: An overview of assurance providers;

- Life-cycle management of real property assets and public-private partnerships.

It is my hope that this report will help further inform and advance discussions on comptrollership issues.

James A. Ralston

Comptroller General of Canada

Overview of the State of Comptrollership in the Government of Canada

Introduction

The Office of the Comptroller General's (OCG's) first Report on the State of Comptrollership in the Government of Canada (March 2011) provided a detailed overview of the health of the comptrollership function across the Government of Canada. It highlighted developments over the previous five years in the comptrollership community and identified priorities in the following areas: financial management, internal audit, investment planning and project management, procurement, materiel management, and real property.

A variety of evidence sources were used to produce the performance data in the OCG's 2011 report. The primary source was the Management Accountability Framework (MAF), which identified management strengths and weaknesses government-wide. In addition to the MAF, the OCG relied on information and findings from other sources such as reports by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada and other external assurance providers, Departmental Audit Committees and the Standing Committee on Public Accounts. Reference was also made to departmental audits and evaluations, and to departments' annual Reports on Plans and Priorities, and Departmental Performance Reports.

This year's report provides an update on the performance of comptrollership functions by presenting the latest round of MAF results. Overall, performance continues to show signs of improvement, and, in many instances, indicates that comptrollership functions are at a high level of maturity.

What Is the Management Accountability Framework (MAF)?

MAF is a key performance management tool that the federal government uses to:

- Support the management accountability of deputy heads; and

- Improve management practices across departments and agencies.

How Does MAF Work?

- Each organization is assessed against criteria or lines of evidence outlined in Areas of Management (AoMs).

- The maturity of practice and capacity for each AoM and line of evidence are assessed using the following scale:

- "Strong": Sustained performance for the AoM that exceeds expectations of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and suggests continued strong performance;

- "Acceptable": Meets the Secretariat's expectations;

- "Opportunity for improvement": Evidence of attention to deficiencies and progress; and

- "Attention required": Inadequate attention to deficiencies.

- All major federal departments and a third of small agencies are assessed annually (approximately 50 organizations each year). Smaller organizations are assessed on a three-year cycle using a more targeted approach.

Internal Audit (Area of Management 5)

The annual MAF assessment to measure the effectiveness of the federal internal audit function enables improved performance and strengthened management practices. MAF Round VIII represented the fifth assessment since the 2006 Policy on Internal Audit came into effect. The criteria for assessing the effectiveness of the internal audit function remained rooted in the policy and focused primarily on the performance and sustainability of the function. These two perspectives enabled an assessment of the internal audit function's governance structure, professional practices, capacity to sustain performance, and value-added contribution to strengthening departmental risk, control and governance processes. Forty large departments and agencies (LDAs) and four small departments and agencies (SDAs) were assessed against three lines of evidence:

- An internal audit governance structure is fully developed and has sufficient capacity to sustain performance;

- Internal audit work is performed in accordance with the Policy on Internal Audit and associated directives; and

- Internal audit is contributing to improvements in risk, control, governance and organizational performance.

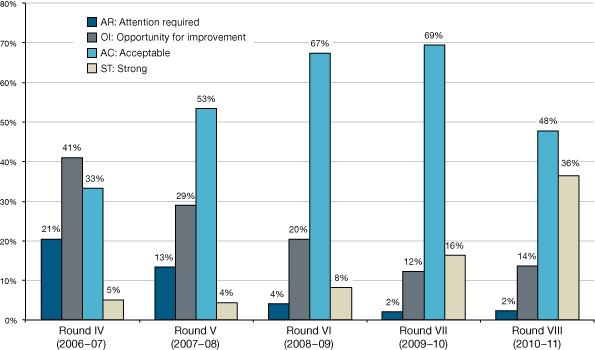

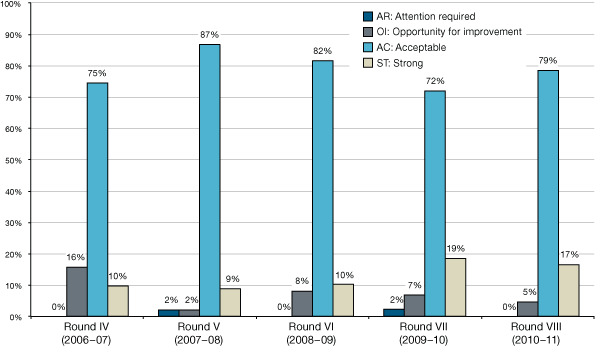

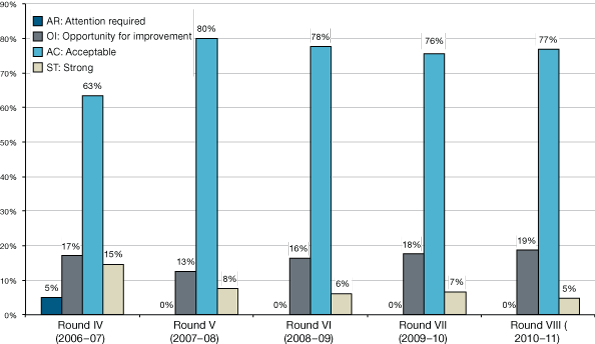

Internal audit continues to perform well. As shown in Figure 1, 84 per cent of departments achieved a "strong" or "acceptable" rating in MAF Round VIII. The distribution of ratings is as follows:

- "Strong": 36 per cent

- "Acceptable": 48 per cent

- "Opportunity for improvement": 14 per cent; and

- "Attention required": 2 per cent.

From MAF Round V to MAF Round VIII, the LDAs and SDAs that achieved a "strong" rating increased as follows: 4 per cent, 8 per cent, 16 per cent and 36 per cent. This increase was largely because of the implementation of the phased-in approach of the 2006 Policy on Internal Audit and the progressive maturation of internal audit regimes government-wide.

Figure 1. Internal Audit Ratings From MAF Round IV (2006–07) to MAF Round VIII (2010–11) (LDAs and SDAs) - Text version

| Rating | Round IV (2006-07) | Round V (2007-08) | Round VI (2008-09) | Round VII (2009-10) | Round VIII (2010-11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Required | 21% | 13% | 4% | 2% | 2% |

| Opportunity for Improvement | 41% | 29% | 20% | 12% | 14% |

| Acceptable | 33% | 53% | 67% | 69% | 48% |

| Strong | 5% | 4% | 8% | 16% | 36% |

| Number of organizations assessed | 39 | 45 | 49 | 49 | 44 |

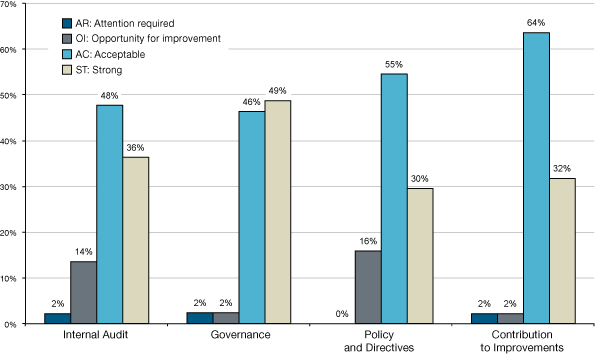

As noted previously, a breakdown of these overall results by individual lines of evidence suggests that organizations are performing at a high level in all the evaluated areas, especially with regard to governance and internal audit's contribution to improvements in their host organization.

Figure 2 MAF Round VIII (2010-11) Internal Audit and Its Lines of Evidence Ratings (LDAs and SDAs) - Text version

| Rating | Internal Audit | Governance | Policy and Directives | Contribution to Improvements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Required | 2% | 2% | 0% | 2% |

| Opportunity for Improvement | 14% | 2% | 16% | 2% |

| Acceptable | 48% | 46% | 55% | 64% |

| Strong | 36% | 49% | 30% | 32% |

Governance

As Figure 2 shows, the majority of departments have fully developed governance structures in place, as illustrated by the 95 per cent "strong" and "acceptable" rating. The independence of chief audit executives is maintained, and Departmental Audit Committees are composed of a majority of external members and provide deputy heads with advice aligned with their areas of mandated responsibility.

Value-Added Contribution

Internal audit regimes are adding value by providing assurance and advice on identified risk, control and governance issues, and on performance. This progressive value-added contribution is evident through annual reporting on the results of the regime's work as articulated in performance reports such as the annual reports of the chief audit executive and the Departmental Audit Committee and in committee records of decision. These performance reports are shifting their focus from activities to results, as indicated by the upward trend in contribution to improvements from a "strong" rating of 18 per cent in MAF Round VII to 32 per cent in MAF Round VIII.

Capacity

Internal audit capacity remains a challenge across all departments. Most human resources plans incorporate recruitment and retention strategies to mitigate this challenge. The primary mitigation strategy employed is the use of external consulting services to contribute to achieving internal audit priorities. However, this is also presenting some challenges because the smaller LDAs cannot compete with the larger departments in securing external resources given that their projects often have a smaller financial value.

In addition, learning plans aligned with risk-based audit plans and other internal audit priorities are implemented and monitored to support improved capacity (and capability). Most departments that achieved an overall rating of "strong" and, to a lesser degree, "acceptable," illustrated that human (and financial) resources were effectively deployed to achieve priorities and sustain performance over time.

Professional Practices

Risk-based audit plans: Departments provided risk-based audit plans as part of rigorous risk assessment exercises that prioritized audit selection based on highest risk and significance. The majority of planned work was assurance-based. Also, areas of highest risk and significance were covered during the planning period in 80 per cent of the plans. Of note, 63 per cent of risk-based plans were assessed as "strong" in MAF Round VIII, compared with 22 per cent in MAF Round VII; this improvement in the quality of plans is attributable to the comprehensive risk‑based methodologies applied. Moreover, 83 per cent of departments had high completion rates (completed projects versus planned projects from 2009–10 plans). This is considered to be an indicator of the value-added contribution of the internal audit function in that areas of high risk and significance in departments were being addressed as a result of the planned projects.

Internal audit reporting: During the MAF assessment period, 245 internal audit reports were submitted to the OCG. Of these, 158 reports were assessed for quality against the reporting criteria outlined in the Internal Auditing Standards for the Government of Canada. Eighty‑five per cent of internal audit reports were aligned with the criteria. The assessment concluded that the quality of audit reports could be improved by including an explicit statement of assurance and by adding more clarity with respect to conclusions, opinions and the significance of findings. The OCG continues to liaise with the internal audit community in support of continuously improving the quality of internal audit reporting.

Although the MAF process in 2010–11 did not formally consider the cycle time and practices for posting audit reports to departmental Internet sites, a review of a sample of departmental websites revealed some inconsistent posting practices. Inconsistencies included internal audit reports being posted without a management action plan in response to the recommendations indicated in an applicable report, and executive summaries being posted rather than complete internal audit reports. Further, some final internal audit reports were not yet posted within one year following submission to the OCG. In early 2011, the OCG provided the audit community with additional guidance regarding expectations for internal audit report posting practices.

Support to the Internal Audit Community

Departmental internal auditors are sharing their best practices via a professional practices forum established by the Office of the Comptroller General (OCG). Departments are encouraged to share tools, techniques, approaches, audit plans, etc. with the internal audit community. The OCG also uses this forum to obtain feedback on guidance documents, self-assessment tools, etc.

Quality assurance improvement program: Although most departments have a quality assurance improvement program in place, the MAF assessment concluded that the application of the key elements of the program could be strengthened. Most departments were rated as "strong" or "acceptable" for their quality assurance improvement programs, but 32 per cent received ratings of "opportunity for improvement" or "attention required." This result is significant because the improvement program is considered an early indicator of the internal audit activity's conformity to the mandatory requirements of the Policy on Internal Audit.

The Policy on Internal Audit requires a department to undergo a practice inspection at least every five years. During 2010–11, nine departments had a quality assurance review or practice inspection conducted, with eight achieving a rating of "generally conforms" (the highest achievable rating) and one receiving a rating of "partially conforms."

Looking Forward

The combined 84 per cent rating of "strong" and "acceptable" in MAF Round VIII demonstrates that the federal internal audit function is meeting the expectations of the Policy on Internal Audit. In light of the increased maturity of the internal audit function, a rebalancing of the number of compliance- and outcome-based measures will be instituted in the MAF Round IX 2011–12 methodology. As viewed through a performance and sustainability lens, the proposed methodology will be streamlined from three lines of evidence to two, which will encompass a balance of compliance- and outcome-based measures. The first line of evidence will focus on the compliance element of the methodology, in particular, professional practices and capacity. The second line of evidence will focus on the value-added contribution of the internal audit regime to the organization. In addition, the more process-specific compliance measures will be removed.

Financial Management (Area of Management 7)

The annual MAF assessment in the area of financial management aims to improve oversight and management practices in departments. More specifically, it measures departments' financial management performance over the year and their capacity to sustain that performance in the long run. In doing so, it covers the whole financial management cycle, from planning to operations and reporting. These assessments yield valuable management information for departments in areas such as governance, internal controls, financial management capacity and stability, and operations relating to the Treasury Board's policy instruments, financial reporting, and financial systems.

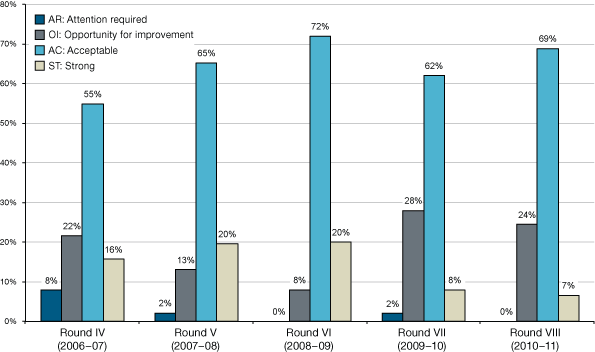

Figure 3. Financial Management Ratings From MAF Round IV (2006–07) to MAF Round VIII (2010–11) (LDAs and SDAs) - Text version

| Rating | Round IV (2006-07) | Round V (2007-08) | Round VI (2008-09) | Round VII (2009-10) | Round VIII (2010-11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Required | 8% | 2% | 0% | 2% | 0% |

| Opportunity for Improvement | 22% | 13% | 8% | 28% | 24% |

| Acceptable | 55% | 65% | 72% | 62% | 69% |

| Strong | 16% | 20% | 20% | 8% | 7% |

| Number of organizations assessed | 51 | 46 | 50 | 50 | 45 |

Overall Financial Management Performance Is Improving

As shown in Figure 3, financial management performance in MAF Round VIII (2010–11) has improved from MAF Round VII (2009–10). This year, 76 per cent of departments achieved an "acceptable" or "strong" rating as compared with 70 per cent the year before. This improvement mainly results from departments reaping the benefits of the successful implementation of a renewed Treasury Board financial management policy framework, which was introduced in 2008–09 to strengthen financial management requirements and capacities in all departments—a government commitment outlined in the Federal Accountability Action Plan.

In particular, this renewed financial management framework has introduced new requirements for departments, including the following:

- The establishment of stronger financial management governance at all levels, clarifying responsibilities of deputy heads in their roles as accounting officers as well as the responsibilities of chief financial officers;

- The conduct of annual departmental risk-based assessments of the effectiveness of departments' systems of internal controls;

- The publication by departments, annexed to their annual financial statements, of summaries of results and action plans from their assessments of the effectiveness of their systems of internal controls over financial reporting;

- The disclosure by departments of in-year spending and variance information on a quarterly basis to better equip parliamentarians to oversee public spending; and

- The phased-in integration of financial information and financial systems across government in support of improved oversight and decision making.

Approximately 90 per cent of all departments assessed had effective financial management governance and accountability mechanisms in support of the oversight roles of the deputy head, the chief financial officer (CFO) and senior managers, including consideration of CFO qualifications.

In addition, 80 per cent of departments had well-informed decision-making practices, clear accountability mechanisms for public resources, and timely information available to support policy and program delivery.

After two years of implementation, the positive effects of the new requirements are becoming more evident across departments, as demonstrated by the performance scores reflected in MAF Round VIII. The decrease in the overall scores between Rounds VI and VII was mainly attributable to the efforts that were originally required by departments to adopt the new Policy Framework for Financial Management.

Finally, overall improvements noted in Round VIII have also been noted in the June 2011 Status Report of the Auditor General to the House of Commons, Chapter 1, "Financial Management and Control and Risk Management." Although there is more work to be done, the Auditor General's report underlines the satisfactory progress made by the OCG and by departments covered by the audit to improve the policy environment across government and to strengthen financial controls and reporting.

Areas for Additional Focus

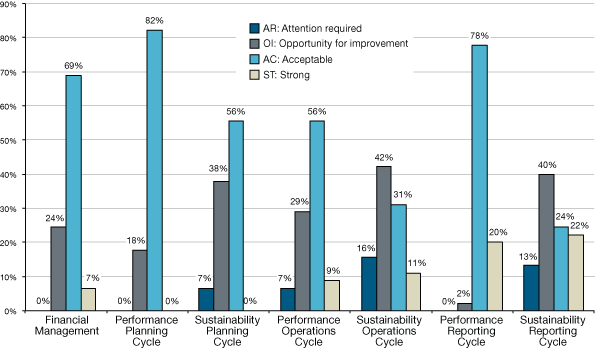

Figure 4. MAF Round VIII (2010–11) Financial Management and Its Lines of Evidence Ratings (LDAs and SDAs) - Text version

| Rating | Financial Management | Performance Planning Cycle | Sustainability Planning Cycle | Performance Operations Cycle | Sustainability Operations Cycle | Performance Reporting Cycle | Sustainability Reporting Cycle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Required | 0% | 0% | 7% | 7% | 16% | 0% | 13% |

| Opportunity for Improvement | 24% | 18% | 38% | 29% | 42% | 2% | 40% |

| Acceptable | 69% | 82% | 56% | 56% | 31% | 78% | 24% |

| Strong | 7% | 0% | 0% | 9% | 11% | 20% | 22% |

Although departments and agencies have improved their overall performance, a more detailed analysis of results for Round VIII indicates that these improvements need to be maintained to sustain performance in the long run. As illustrated in Figure 4, results show that about 53 per cent of departments were rated as less than acceptable in their capacity to sustain performance in their planning, operations and reporting cycles. Financial organizations in departments particularly need stabilization through reduced vacancies and reduced use of interim staffing, increasing the base of experience in the departmental financial management team, and lengthening the time in positions.

Within the performance of the operations cycle, over 80 per cent of departments have made good to strong progress in implementing financial management audit recommendations.

Almost 70 per cent of departments subject to the Policy on Transfer Payments were rated as "acceptable" or "strong."

Over 75 per cent of departments had fully complied with the Treasury Board Accounting Standard 1.2—Departmental and Agency Financial Statements.

Taking into account the fiscal restraint agenda and its impact on departments, we will continue to oversee the financial management performance of departments and their capacity to sustain it in all areas.

Assets and Acquired Services

Assets and acquired services comprise three distinct functional areas: procurement management, asset management, and investment and project management planning. Each area is presented separately in the following, but, overall, all continue to perform well and have been relatively stable in the last few years.

Procurement (Area of Management 11)

The procurement function's MAF performance continues to be strong and is virtually unchanged from previous Rounds.

Figure 5. Procurement Management Ratings From MAF Round IV (2006–07) to MAF Round VIII (2010–11) (LDAs and SDAs) - Text version

| Rating | Round IV (2006-07) | Round V (2007-08) | Round VI (2008-09) | Round VII (2009-10) | Round VIII (2010-11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Required | 0% | 2% | 0% | 2% | 0% |

| Opportunity for Improvement | 16% | 2% | 8% | 7% | 5% |

| Acceptable | 75% | 87% | 82% | 72% | 79% |

| Strong | 10% | 9% | 10% | 19% | 17% |

| Number of organizations assessed | 51 | 45 | 49 | 43 | 42 |

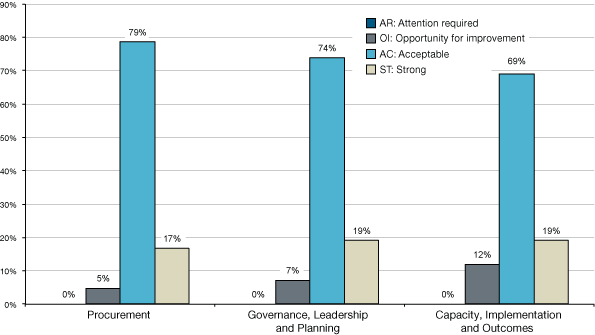

Breaking down these overall results by individual line of evidence reveals no systemic weakness across the federal government. Ninety-five per cent of assessed organizations have a "strong" or "acceptable" rating, partly because of the maturity of the Contracting Policy (see Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 6. MAF Round VIII (2010–11) Procurement Management and Its Lines of Evidence Ratings (LDAs and SDAs) - Text version

| Rating | Procurement | Governance, Leadership and Planning | Capacity, Implementation and Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Required | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Opportunity for Improvement | 5% | 7% | 12% |

| Acceptable | 79% | 74% | 69% |

| Strong | 17% | 19% | 19% |

Some departments are implementing human resources best practices in the procurement field. This is particularly important in order to reinforce innovative initiatives related to capacity in managing procurement activities. The following are specific examples taken from the Management Accountability Framework exercise:

- Creation of departmental Purchasing and Supply (PG) mentor positions: Newcomers to the organization are paired with more experienced employees (mentors) in order to obtain information, lessons learned and advice as they advance in the organization. The benefits are positive for the organization, encouraging retention, improving productivity, elevating knowledge transfer, and retaining the practical experience and wisdom of experienced employees.

- Creation of PG cross-training opportunities: Cross-training involves teaching an employee who was hired to perform one job function the skills required to perform other job functions. Cross-trained employees become skilled at tasks outside the usual parameters of their responsibility. When teams are effectively cross-trained, the organization is more flexible. Cross-training is a good way to break down the "silo" mentality and encourage cooperation among divisions. It also raises awareness of the responsibilities of other groups within the organizations and increases capacity to cope with unexpected absences.

- Creation of a PG contract-monitoring and reporting-specialist position: This specialist reviews client procurement requirements and makes recommendations before submission to the contracting process. This position also consolidates and improves procurement reporting to meet trade and socio-economic obligations.

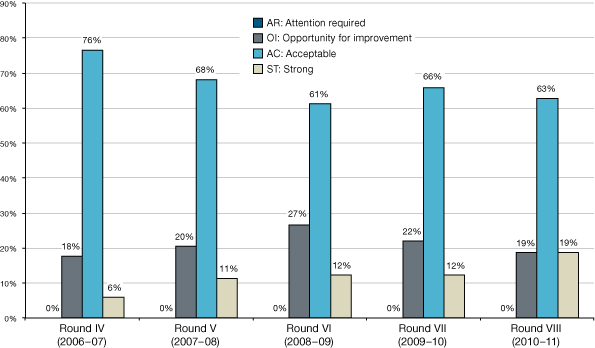

Asset Management (Area of Management 14)

Overall, the asset management function continues to perform well, with 19 per cent of departments and agencies now scoring a "strong" rating in Area of Management (AoM) 14 (see Figure 7). The improved asset management ratings in Round VII and VIII may be partially because of the transfer of the investment planning line of evidence from this AoM to the Project Management and Investment Planning AoM in 2009–10. A number of departments had low ratings in the investment planning line of evidence in Rounds IV, V and VI.

Figure 7. Asset Management Ratings From MAF Round IV (2006–07) to MAF Round VIII (2010–11) (LDAs and SDAs) - Text version

| Rating | Round IV (2006-07) | Round V (2007-08) | Round VI (2008-09) | Round VII (2009-10) | Round VIII (2010-11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Required | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Opportunity for Improvement | 18% | 20% | 27% | 22% | 19% |

| Acceptable | 76% | 68% | 61% | 66% | 63% |

| Strong | 6% | 11% | 12% | 12% | 19% |

| Number of organizations assessed | 51 | 44 | 49 | 41 | 43 |

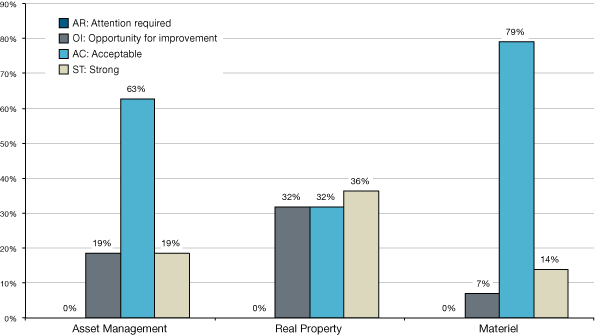

An analysis of the overall scores reveals that departments and agencies continue to do better in materiel management than in real property management (see Figure 8). One reason is that the complexity, value and size of many departmental real property holdings presents a higher risk than materiel holdings, and management expectations are therefore higher. Further, many of the departments assessed have no real property holdings and have only a limited materiel asset base, and so the level of evidence required for these organizations to achieve an "acceptable" rating or higher is less onerous.

Departments are engaging in numerous green initiatives in managing their materiel. Several environmentally friendly best practices and initiatives have been identified in the Management Accountability Framework process. These initiatives range from environmentally friendly disposal of e‑waste to the operation of light-duty vehicles for departmental and executive use, with an aim of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

A department that recently had a "strong" rating in the real property line of evidence developed a due diligence checklist that could be used as a best practice by other federal custodians. The checklist records the necessary steps for the acquisition and disposition of federal real property. Employees, both experienced and new, can use the checklist to verify that all Treasury Board real property policy requirements have been met before they finalize transactions.

Figure 8. MAF Round VIII (2010–11) Asset Management and Its Lines of Evidence Ratings (LDAs and SDAs) - Text version

| Rating | Asset Management | Real Property | Materiel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Required | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Opportunity for Improvement | 19% | 32% | 7% |

| Acceptable | 63% | 32% | 79% |

| Strong | 19% | 36% | 14% |

Investment Planning and Management of Projects (Area of Management 15)

Overall, the performance of activities related to the investment planning and management of projects has remained relatively stable since departments were last assessed (see Figure 9). As expected, departments that have completed the transition to the new Policy on Investment Planning—Assets and Acquired Services and the new Policy on the Management of Projects fared better than those that have not yet completed the transition.

Figure 9. Project Management Ratings From MAF Round IV (2006–07) to MAF Round VIII (2010–11) (LDAs and SDAs) - Text version

| Rating | Round IV (2006-07) | Round V (2007-08) | Round VI (2008-09) | Round VII (2009-10) | Round VIII (2010-11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention Required | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Opportunity for Improvement | 17% | 13% | 16% | 18% | 19% |

| Acceptable | 63% | 80% | 78% | 76% | 77% |

| Strong | 15% | 8% | 6% | 7% | 5% |

| Number of organizations assessed | 41 | 40 | 49 | 45 | 43 |

Breaking down these overall results by individual line of evidence suggests that most departments and agencies are performing well in managing their portfolio of projects, project resources and project results, with the latter significantly improving over last year.

Investment planning continues to be a challenge for many departments, and scores in this area have declined since Round VII. Investment planning was rated as "strong" for departments that have produced a long-term integrated investment plan. This reflects the management performance needed to produce an effective plan at the enterprise level.

The expectation is that departments will continue to identify opportunities to improve and better integrate their resource allocation and decision-making practices as they align with the requirements of the Policy on Investment Planning—Assets and Acquired Services.

Conclusion

Overall, the MAF results are favourable and continue to improve, but challenges remain. Specifically, there are ongoing concerns regarding capacity and sustainability; this issue is particularly relevant given the current economic context and the need for departments and agencies to realize significant savings.

The OCG is committed to continuing to improve lines of evidence to assess the performance of comptrollership functions and streamline the reporting burden on departments.

We will continue to update our assessment of the health of the internal audit, financial management and assets, and acquired services functions going forward.

Office of Comptroller General of Canada: Highlights of Accomplishments in 2011–12 and Priorities for 2012–15

Highlights in 2011–12

The Office of the Comptroller General's (OCG's) March 2011 Report on the State of Comptrollership in the Government of Canada summarized key priorities in the areas of internal audit, financial management, and assets and acquired services. It provided a three-year plan (2011–12 to 2013–14) of the policy, operations and community initiatives that the OCG was undertaking. The following tables highlight key activities accomplished to March 31, 2012.

| Area | Financial Management | Update |

|---|---|---|

| Policy | Support the chief financial officer's (CFO's) sign-off/attestation role. | The OCG is in the process of drafting a guideline to provide a common approach and framework for CFOs for signing off on Memoranda to Cabinet and Treasury Board submissions that will support informed decision making. Following consultations, the document will be ready for approval in 2012–13. |

| Provide guidance on user fee management. | Three sub-activities were completed to develop guidance on user fee management: analysis of options and drafting of potential requirements, alignment of future guidance with the User Fees Act and other relevant policies, and recommendation of draft policy instruments. The OCG will commence consultations with appropriate stakeholders in 2012–13 with a view to finalizing the policy instruments. | |

| Improve efficiencies in the financial legislative framework. | The OCG led the development of legislative changes that culminated in the coming into force of a new section of the Financial Administration Act. Section 29.2 authorizes departments (within prescribed limitations) to provide internal support services to, and receive internal support services from, other departments. The OCG has put in place a new directive to support the orderly implementation of the new legislative provisions. | |

| Implement the Directive on the Management of Expenditures on Travel, Hospitality and Conferences. | The directive came into force in January 2011. Departments published their first annual reports on their total expenditures related to travel, hospitality and conferences in fall 2011. | |

| Standardize financial business processes and common financial information. | The OCG is delivering on its commitment to complete the Guideline on Common Financial Management Business Process 3.1—Manage Procure to Pay and the Guideline on Common Financial Management Business Process for Pay Administration. As well, additional guideline documents are in development. The Common Enterprise Data Initiative continues to refine the data standardization strategy, which is designed to help the flow and quality of key data by establishing standards. This initiative is on track to produce project guidelines by the end of the fiscal year. | |

| Update and rationalize requirements under the Policy on Transfer Payments. 1 | The Policy on Transfer Payments and Directive on Transfer Payments were updated to provide ministers and deputy heads with increased authorities to amend program terms and conditions. In addition, the previous plan to submit a three-year plan for transfer payment programs to the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat by April 1 of each year was integrated into departmental Reports on Plans and Priorities (RPPs). With the policy changes, the three-year plan has now been integrated into departmental RPPs on an ongoing basis. | |

| Operations | Make financial information more open. | Research was conducted to identify international open data practices, the Government of Canada's financial information currently available to the public, and other financial information sources that could be open to the public. In addition, the OCG is monitoring the implementation of the Parliamentary Budget Officer's Integrated Monitoring Database and other projects related to open data initiatives. |

| Reduce reporting burden by eliminating duplication in the Public Accounts of Canada. | An analysis was conducted to identify duplications in the Public Accounts of Canada. Approval for a Parliamentary engagement plan to consult on changes to the Public Accounts will be sought in 2012–13. | |

| Improve departmental knowledge of accounting and reporting requirements. | Support was provided to departments and agencies in implementing accounting changes, including but not limited to the transition to new standards and their implementation. This included international financial reporting standards, public sector accounting standards, Canadian accounting standards, and the implementation of quarterly financial reporting and Treasury Board Accounting Standards (TBAS 1.2). Compliance monitoring was conducted through the Management Accountability Framework (MAF), and feedback was provided to departments on areas that required improvement. | |

| Complete implementation of the Policy on Internal Control. | Implementation was conducted in a phased approach and is currently 80 per cent complete. Phase I departments have published their second annual report on the management of internal control. Phase II departments have published their first reports, and the remaining departments are well positioned to publish their reports in 2012. | |

| Development of guidance and tools to support standardized and efficient practices in the delivery of grants and contributions (Gs&Cs). 2 | The OCG led interdepartmental working groups that developed a Gs&Cs risk management approach and a common business process framework for life-cycle management of Gs&Cs. An interdepartmental workshop was also held on the harmonization and standardization of transfer payment programs. | |

| Improve departmental efficiencies in the delivery of Gs&Cs. 3 | Through outreach to departments and by providing ongoing support to departmentally led pilot projects, the OCG addressed perceived policy and legal barriers and shared expertise on interdepartmental Gs&Cs delivery models. | |

| Community | Support the development of future CFOs through talent and community management and by addressing competency gaps. | The CFO succession risk assessment is being conducted on an ongoing basis, as is the Financial Executive Profile, enabling identification of priority areas for accelerated learning and development and for CFO succession planning. |

| Advance the community-based program on capacity within the financial management community. | The Financial Officer Recruitment and Development (FORD) Program has met 55 per cent of its annual entry-level officer placement goals. Recruitment activities have begun for the 2012–13 year. Placement for all cohort 2 individuals has been successfully secured. | |

| Revise and update the training course for transfer payment departmental practitioners. | The OCG updated the Canada School of Public Service course on transfer payments. |

| Area | Internal Audit | Update |

|---|---|---|

| Policy | Revise the Policy on Internal Audit to respond to results of the evaluation (June 2011). | The revisions to the Policy on Internal Audit were approved by Treasury Board on March 29, 2012, and the revised policy came into effect on April 1, 2012. |

| Develop guidance for internal auditors regarding their role in internal control over financial reporting. | Draft guidance on roles and responsibilities regarding internal control over financial reporting has been developed and was presented to the Comptroller General's Advisory Council for comments. | |

| Operations | Undertake core control audits in small departments and agencies in the areas of human resources, financial management, contracting, travel and hospitality, and payroll. | Since April 2011, 11 core controls audits have been completed. |

| Perform horizontal audits in small departments and agencies (SDAs) and large departments and agencies (LDAs) to address areas of government-wide risk, including governance (for SDAs), common services (for LDAs) and information management (for SDAs and LDAs). | Since April 2011, 6 horizontal audits in a total of 28 LDAs and 31 SDAs have been completed. | |

| Improve internal audit intelligence through analysis of audit-related information, and identify best practices. | Analysis of risk-based audit plans (2010–11) was completed and provided to all chief audit executives (CAEs), and an analysis of internal audit reports completed in fiscal year 2010–11 was provided to CAEs and Treasury Board policy centres. | |

| Community | Revise core training courses and delivery mechanisms for departmental audit committees. | The University of Ottawa has taken on responsibility for the departmental audit committee courses. |

| With the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) and the Canada School of Public Service (CSPS), develop new learning delivery models for internal audit training. | An agreement has been reached whereby the OCG's Internal Audit Sector will be using IIA Ottawa chapter venues to offer new learning opportunities that include webinars and online training. The CSPS will continue to offer regular training. | |

| Support succession planning for departmental audit committees and update the terms and conditions of appointment. | Guidance on succession planning has been developed. Departmental audit committee terms and conditions are being updated to reflect revisions to the Policy on Internal Audit. | |

| Support increased professionalism in internal audit, including setting requirements for certification for CAEs. | A clear statement of CAE requirements has been provided to the internal audit community and included in the revised policy. | |

| With the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO), research the establishment of internal auditor classification, group or stream. | The OCG is working with OCHRO to address the internal auditor classification issue. | |

| Support talent management for CAEs and internal auditors, including core competencies, training, and promotion and retention from entry level to the CAE level. | Core competencies and generic work descriptions have been developed and made available to the internal audit community. In addition, coaching and mentoring services have been provided to CAEs. |

| Area | Assets and Acquired Services | Update |

|---|---|---|

| Policy | Amend the Policy on Management of Real Property to transition to capacity-based transaction approval limits. | Treasury Board approval of amendments to the Policy on Management of Real Property to facilitate the transition to capacity-based transaction approval limits was obtained in November 2011. |

| Renew the Policy on Decision Making in Limiting Contractor Liability in Crown Procurement Contracts. | The renewal of the Policy on Decision Making in Limiting Contractor Liability in Crown Procurement Contracts has now been aligned with broader procurement policy renewal work. | |

| Rescind the Procurement Review Policy. | Approval to rescind the Treasury Board's Contracting Policy, the Policy on Decision Making in Limiting Contractor Liability in Crown Procurement Contracts and the Procurement Review Policy, and approval of the four new policy instruments (the Policy on Managing Procurement, the Directive on Contracting Approval, the Directive on Crown Procurement Contracting and the Directive on Limiting Contractor Liability) are awaiting Treasury Board consideration. | |

| Amend the Government Contracts Regulations. | The amendments came into force on September 22, 2011, and were officially promulgated by the Canada Gazette on October 12, 2011. Two separate Contract Policy Notices were prepared and issued to the stakeholder community to inform it of the changes. The OCG is preparing to launch a second round of Government Contracts Regulations amendments. |

|

| Operations | Implement the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan (Phase II). | Cabinet approved Phase II of the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan in June 2011, and Treasury Board approved Phase II funding for 18 departments in September 2011. Incremental new funding was indentified in Budget 2011 to facilitate implementation of Phase II. |

| Implement the Policy on Managing Procurement and the two related directives. | As previously indicated, the policy and directives are awaiting Treasury Board consideration. | |

| Implement the Policy on Investment Planning—Assets and Acquired Services and the Policy on the Management of Projects. | April 1, 2012, marked the end of the five-year transition period for the Treasury Board Policy on Investment Planning—Assets and Acquired Services and the Policy on Management of Projects. As of that date, the outgoing policies were rescinded and 99 departments are now subject to the new policies, with 2 departments having secured extensions from the Treasury Board. Of the departments now subject to the new policies, 21 have completed an Organizational Project Management Capacity Assessment (OPMCA), and their resulting OPMCA class has been approved by Treasury Board ministers in consideration of their departmental investment plans. These departments accounted for approximately 70 per cent of the Government of Canada's spending on assets and acquired services in 2010–11. The new online application Callipers was successfully launched, providing departments and the Secretariat with real-time access to the Project Complexity and Risk Assessment tool and the OPMCA tool. | |

| Community | Enhance the Certification Program for the Federal Government Procurement and Materiel Management Community. | Subsequent to a review of material for the Certification Program for the Federal Government Procurement and Materiel Management Community, various courses and manuals have been updated and other updates are underway. A series of 15 information sessions and Candidate Achievement Record workshops were delivered in the National Capital Region and other Regions. The Personal Information Bank for the certification program is being updated to improve access to the information in order to better support enrollees in completing their certification. |

| Develop Level II assessments for the Certification Program for the Federal Government Procurement and Materiel Management Community. | The Level II Case Study for Procurement and the associated scoring grid and evaluator's training guide have been finalized based on the evaluation of the results of the pilot exams. | |

| Conduct a mandated five‑year review of the Canadian General Standards Board's (CGSB's) Competencies of the Federal Government Procurement, Materiel Management and Real Property Community. | A decision to no longer maintain the CGSB's Competencies of the Federal Government Procurement, Materiel Management and Real Property Community (CGSB-192.1-2005) was endorsed by the Procurement, Materiel Management and Real Property Communities Director General Steering Committee. In its place, competency dictionaries for each community will be posted on the Secretariat's website. Review of the competencies by interdepartmental working groups for each community is in progress, and a consultation-ready draft is slated for completion by the end of the 2012–13 fiscal year. |

Priorities for 2012–15

| Area | Internal Audit | Financial Management | Assets and Acquired Services |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy | Develop a performance management framework to support the ongoing assessment of the implementation of the Policy on Internal Audit. Develop guidance for the internal audit community on chief audit executive (CAE) and departmental audit committee (DAC) reports. |

Initiate the next phase of reform for grants and contributions (2011–13). Develop a guideline on chief financial officer (CFO) sign-off. Advance the renewal of the Policy on Special Revenue Spending Authorities. Develop a directive on user fee management. |

Obtain approval of the Policy on Managing Procurement and its three related directives and guides. Initiate changes to the Government Contracts Regulations (Round II). Initiate the five-year review of the Policy on Investment Planning—Assets and Acquired Services and the Policy on the Management of Projects. Initiate the five-year review of the Policy on Management of Real Property and the Policy on Management of Materiel. Review the Common Services Policy. |

| Operations | Implement the revised Policy on Internal Audit. Undertake core control audits in small departments and agencies (SDAs). Perform horizontal audits in SDAs and large departments and agencies (LDAs). Provide internal audit services to the Regional Development Agencies cluster and selected SDAs. Develop internal audit intelligence reports that analyze departmental risk-based audit plans and reports. Develop and implement a quality assurance improvement program for horizontal and core control audits; update the practice inspection guidebook. Develop a three-year plan for Management Accountability Framework (MAF) criteria and indicators. |

Lead the independent review of National Fighter Procurement Action Plan. Reduce reporting burden by eliminating duplication in the Public Accounts of Canada. Develop the Business Solutions Project. Advance the Common Enterprise Data Initiative. Continue to implement Common Business Practices. Complete transitional implementation of the Policy on Internal Control (2012–13 to 2013–14). Develop a framework to support the five-year review of policies on financial management and the Policy on Transfer Payments. |

Implement Phase II of the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan (Phase II). Develop data extracts from the Directory of Federal Real Property and the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory for inclusion on the government's Open Data Portal. Implement capacity-based real property transaction approval limits. Implement the Policy on Investment Planning—Assets and Acquired Services and the Policy on the Management of Projects. |

| Community | Process DAC appointments and renewals. Review DAC appointment process and terms and conditions. Work with the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer to address internal audit classification issues. Develop and implement tools to support internal audit and CAE talent management. |

Develop the five-year Competency-Based Financial Management Community Development Strategy 2013–18. Develop and implement a CFO and deputy CFO talent management and succession planning process. Modernize the Financial Officer Recruitment and Development / Internal Auditor Recruitment and Development (FORD/IARD) Program. Finalize amendments to the Chartered Accountant Student Training (CAST) Program guidelines. Facilitate integration of CAST cohorts 2 and 4 into the financial management community. |

Create and publish competency dictionaries for the procurement, materiel management and real property communities to replace the Canadian General Standards Board's Standard Competencies of the Federal Government Procurement, Materiel Management and Real Property Community. Complete the 2012 Real Property Demographic Workforce Analysis and Profile. Enhance the Certification Program for the Federal Government Procurement and Materiel Management Community, and launch Level II certification. |

Part II: Three Research Papers on Aspects of Comptrollership in Canada

Sustaining the Chief Financial Officer Suite: The Case for a Community-Based Approach to Chief Financial Officer Talent Management and Succession Planning

The Evolving Role of the Chief Financial Officer

Introduction of the Chief Financial Officer Model Redefined the Vision

The Government of Canada formally adopted the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) Model with the coming into force of the Treasury Board Policy Framework for Financial Management on June 1, 2010. The framework broadly sets out the distinct yet interrelated roles of those responsible for financial management in government:

- Deputy heads, as accounting officers, are accountable before Parliament for their management responsibilities, including financial management;

- CFOs directly support deputy heads—they are the lead departmental executives for financial management, providing key objective strategic advice on the overall stewardship of a department's financial management culture and its performance; and

- The Comptroller General of Canada provides functional direction for financial management, fosters best practices, and ensures that government financial management practices are aligned with the principles and supporting instruments of the Policy Framework for Financial Management.

The Policy on Financial Management Governance, one of the key policy instruments underpinning the Treasury Board Policy Framework for Financial Management, further elaborates on these roles and responsibilities and on the nature of the support that CFOs are expected to provide to their deputy heads. The strategic advisor role identified in the framework is expanded upon to include independent and objective recommendations on all funding initiatives and resource allocations that require the deputy head's approval. The policy also identifies the CFO as, among other things:

- The key steward of relevant legislation, policy and directives;

- The senior executive responsible for developing, communicating and maintaining the departmental financial management framework; and

- The senior executive responsible for providing leadership and oversight on the proper application and monitoring of financial management across the department.

In turn, the reliance that deputy heads have on their CFOs is reinforced through a policy requirement for a direct reporting relationship between the two. In addition, the policy specifically makes deputy heads responsible for the appointment of a suitably qualified CFO. Deputy heads are to ensure that the Comptroller General, or his or her representative, is a member of any CFO selection committee. This is to reflect the fact that the Office of the Comptroller General (OCG) has functional leadership over the financial management community, including CFOs.

The introduction of the CFO Model, and the policy suite that supports it, established a new vision for financial management across government: a vision rooted in accountability. Roles and responsibilities of all players are clearly articulated, and the interrelationships between these roles are critical to the success of the model. Although individual departmental accountabilities for financial management rest with deputy heads and the CFOs who support them, the OCG has overarching responsibility for the financial management function government-wide, including the development of sustainable capacity of the community.

Comparing Private and Public Sector CFOs

In many ways, the evolution of the CFO's role in the federal government mirrors that of the CFO in the private sector. Beyond the requirement for increased accountability and transparency, however, a more fundamental shift has occurred. The private sector CFO has, for a long time, been expected to be a key business partner who provides valuable insight to support corporate decision making. Today, the federal government CFO is expected to play a comparable role, i.e., to be a key strategic advisor to the deputy head and to provide him or her with an objective, department-wide perspective on all business matters. This represents a significant change in role.

Studies on the CFO function undertaken by IBM 4 provide insight into how government CFOs around the world perceive their role, and their effectiveness in that role, compared with their private sector counterparts. Key activities were divided between those considered core finance and those considered enterprise-focused (see "Core Finance Activities" and "Enterprise-Focused Activities" below). Although government CFOs considered enterprise-focused activities important, their assessment of their own finance organizations' effectiveness in undertaking these activities was appreciably lower than was the case for private sector CFOs.

Core Finance Activities

- Strengthening compliance programs and internal controls

- Developing people in the finance organization

- Executing continuous finance process improvements

- Driving finance cost reduction

Enterprise-Focused Activities

- Measuring and monitoring business performance

- Providing inputs into enterprise strategy

- Driving enterprise cost reduction

- Supporting, managing and mitigating enterprise risk

- Driving integration of information across the enterprise

The realities in which government and private sector CFOs function are undeniably different. Government CFOs operate within a complex legislative and policy framework and must react to rapidly shifting political priorities. That said, acknowledging the gap between government and private sector CFOs identified in the study is worthwhile; it confirms the role that effective CFOs must play in modern organizations and speaks to the need in the public sector for competency development initiatives to ensure that these expectations are met.

Significant Transformation of the Financial Management Function

The introduction of the CFO Model to the federal government was seen as a critical step to improving financial management and accountability. It also signalled a major response to the sponsorship scandal and as such is directly linked to the Federal Accountability Act. Accordingly, the transformation of the financial management function in recent years has been extensive.

To ensure professionalism in implementing the CFO Model, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat issued the Guideline on Chief Financial Officer Qualifications. The guideline is based on the premise that the qualifications of CFOs are critical to the credibility, and to the perception of credibility, of the financial management functions they lead. CFOs and deputy CFOs (DCFOs) are each expected to have an appropriate combination of education, professional qualifications, experience and competencies in order to fulfill their duties. Under the guideline, in appointing CFOs, preference in all cases should be given to candidates who have a professional accounting designation. In all but the smallest departments, the guideline expects that, between the CFO and the DCFO, at least one possesses such a designation.

The Policy on Financial Management Governance came into force on April 1, 2009, and departments were expected to align their practices with those set out in the related Guideline on Chief Financial Officer Qualifications by that date. Given the consultative nature of the policy development process, the financial management community was aware of, and already responding to, the direction that the Secretariat was taking well before the policy instruments were finalized. As outlined in Table 1, the professionalization of the function has advanced overall, particularly with respect to accreditation. There is also greater capacity across the financial management community at the executive level than there has been in terms of this key attribute of the CFO Model.

| Proportion of Executive (EX) Respondents | 2003 | 2009 |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of EX respondents who have a bachelor's degree or higher | 82% | 90% |

| Proportion of EX respondents who have a professional accounting designation | 50% | 70% |

The progress made by the community in recent years has not gone unnoticed by the Auditor General. In Chapter 1 of her Status Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the House of Commons (2011), Auditor General Sheila Fraser noted that in all the departments implicated in the audit, CFOs met the requirements for their positions and that the roles, responsibilities, authorities and accountabilities assigned to them complied with the Policy on Financial Management Governance. The audit report also confirmed that CFOs have assumed the key strategic advisor role that is at the heart of the evolution of the CFO within government. The report cited examples of change within departments influenced by the CFO's advice and noted the considerable increase in the number of CFOs and DCFOS who hold a professional accounting designation compared with earlier years:

In 2002, when we first reported on this issue, only 33 percent of senior financial officers had recognized professional accounting designations. In 2010, we found that 82 percent of chief financial officers and 82 percent of the deputy chief financial officers in the 22 largest departments had these designations. While the Guideline on Chief Financial Officer Qualifications requires that at least one of these officers hold one such designation, in many departments, both officers held designations. This is a significant improvement across the government since we first reported on this issue eight years ago. This high level of professional qualification provides the large departments with the skills and competencies to continue the work to fully meet the requirements of the financial management and control policies. (p. 21)

The successful appointment of so many highly qualified CFOs in such a relatively short period of time is a major accomplishment and has greatly contributed to the progress we have observed in financial management such as that noted in the first Report on the State of Comptrollership in the Government of Canada (2011):

- On internal control: "Broadly speaking, departments have already been enhancing their efforts to manage their systems of internal control to ensure they are effective." (p. 10)

- On financial reporting: "In 2009–2010, MAF ratings on the quality of departmental financial statements for 90 per cent of departments and agencies were rated as 'acceptable' or 'strong.'" (p. 12)

- On financial systems: "Governance models for departmental financial management systems were strong, which enables senior management to better identify, integrate and address financial management systems issues that arise." (p. 13)

This recruitment effort benefited from the existence of a large cadre of highly qualified and experienced financial management executives who were ready to assume the mantle of CFO.

Meeting Future Needs

The Challenges of CFO Demographics

Across government and among its leadership ranks in particular, the aging of the baby boom generation, coupled with the impact of program review in the mid-1990s, is being felt, as emphasized in the Fourth Report of the Prime Minister's Advisory Committee on the Public Service (2010):

A complete transformation in the leadership of the public service is taking place as the retirement of the post-war generation and the cessation of recruitment in the mid-1990s play out. In the near term, the effect of this changeover is churn in the senior ranks….

Within this context, the importance of rigorous talent management, including succession planning, cannot be overstated. (p. 7)

The CFO community has been faced with this demographic challenge in recent years and is expected to continue to be affected.

In May and June 2011, the OCG conducted interviews with 67 CFOs across government as part of a community-wide succession risk assessment. Almost all Tier 1 and Tier 2 CFOs 5 were interviewed, as were about half of Tier 3 CFOs. Of these 67 CFOs, 18 (27 per cent) indicated that they were likely or very likely to retire within the next three years. In addition, CFO vacancies will arise when CFOs seek lateral or promotional appointments.

Given that the vast majority of CFO positions are filled from within the existing financial management community, and at times from within the existing CFO community, an individual retirement or other move out of a CFO position can have a domino effect to varying degrees throughout the community, magnifying the degree of churn across the financial management senior ranks.

Although retirement projections for the CFO community are not unique in the whole-of-government context, they are material. Encouragingly, the CFO interviews indicated that there is a considerable pool of talent available from which to draw successors. The challenge will be to ensure that these candidates possess the full range of competencies necessary for the CFO role of today.

Aligning Competencies With Today's Requirements

Given its mandate to support the development of sustainable capacity of the financial management community and the fact that the DCFO population is the primary feeder group for CFO positions, the OCG recently ran collective staffing processes for DCFO positions at the EX‑02 and EX‑03 levels (see Table 2). The intention of these processes was to establish pre‑qualified pools at both levels from which departments could draw to fill vacancies as they arise. The processes were open to public servants and to the public, and drew applicants from across the country.

| Step in Staffing Process | EX-02 Process | EX-03 Process |

|---|---|---|

| Applications received | 250 | 167 |

| Applicants screened in | 73 | 27 |

| Applicants placed in pre-qualified pool | 9 | 4 |

The performance of many candidates on the written exam (in the case of the EX-02 process) and at the interviews (in both processes) demonstrated an absence of strategic thinking and analysis. These candidates, many of whom were known within the CFO community to be otherwise strong performers, did not qualify for the pool. It is noteworthy that external candidates, particularly in the EX-03 process, demonstrated these competencies more frequently than internal candidates did, an observation consistent with the IBM study referred to earlier.

Candidates' performance in these collective processes appears somewhat at odds with data recently collected by the OCG on how financial management executives perceive their own strengths and weaknesses. The 2011 financial executive profile gathered information from 121 individuals at the EX-01 to EX-03 levels within financial management organizations. Participants were asked to identify their level of knowledge and experience in a variety of fields of practice that were organized among four roles from a proposed CFO Competency Model (see Appendix A, "Proposed Chief Financial Officer Competency Model"). More than three quarters of EX-01 and EX‑02 respondents and almost all EX-03 respondents self-assessed as either "experienced" or "expert" in the strategist role (see Table 3).

| Self-Assessed Level of Competency | Steward Role The steward is oriented toward robust resource management, control rationalization and financial information quality. | Operator Role The operator is oriented toward best practices of the finance function itself. | Catalyst Role The catalyst is oriented toward best practices of the entire organization. | Strategist Role The strategist is oriented toward long-term strategic issues and is outwardly directed. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EX-01 and EX-02 | EX-03 | Total | EX-01 and EX-02 | EX-03 | Total | EX-01 and EX-02 | EX-03 | Total | EX-01 and EX-02 | EX-03 | Total | |

| Expert | 28% | 41% | 31% | 27% | 29% | 25% | 26% | 47% | 31% | 22% | 50% | 28% |

| Experienced | 45% | 40% | 44% | 35% | 47% | 38% | 50% | 38% | 50% | 55% | 46% | 53% |

| Aware | 25% | 19% | 24% | 33% | 22% | 32% | 20% | 14% | 19% | 23% | 4% | 19% |

| Unfamiliar | 2% | 0% | 1% | 5% | 2% | 5% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

Given that many internal candidates failed to demonstrate competencies associated with the strategist role and yet the vast majority of the executives surveyed self-assessed favourably in this regard, a misalignment of expectations between financial executives and their superiors may be in evidence. This disconnect has been previously noted, as feedback from deputy heads who are involved with CFO selection processes consistently indicates that they do not feel confident that many candidates would able to fulfill this role in their organization. There appears to be a need to recalibrate and communicate expectations, and to pursue professional development and other interventions to ensure that otherwise qualified candidates can advance in their financial management careers.

The Need for Formalized Succession Planning

Notwithstanding the evidence of pending churn in the ranks of CFOs and DCFOs, few departments are actively managing the issue. Among the 67 departments that participated in the succession risk assessment mentioned previously, only 21 per cent had a documented CFO succession plan. For DCFO positions, the incidence of documented succession plans was even lower, at only 15 per cent of departments. The problem is particularly acute within smaller departments and agencies; for these, it is well acknowledged that succession planning is inherently challenging. Of the 25 Tier 3 departments that participated, only 3 had a documented CFO succession plan, and only 2 had such a plan for the DCFO position.

During the interviews, CFOs were asked to identify potential successors for their positions, from inside or outside their own department, and the timeline by which they felt the individuals would be ready to assume the CFO role. The extent to which they were able to identify potential successors varied; in many cases, CFOs could not identify anyone. Where CFOs did not identify any potential internal successor, the reasons varied. In some cases, they indicated that individuals in the feeder group lacked certain competencies that are required to assume the CFO role. In other instances, CFOs indicated that some individuals were not considered likely potential successors because they did not have these particular career aspirations or because their retirement was pending.

The CFOs were also asked to identify potential CFO successors for other departments (i.e., where they saw a good potential fit); however, very few could offer specific names.

Evident in CFO responses to questions about succession planning is a low awareness, community-wide, of potential CFO successors. Fortunately, although some CFOs could not identify any potential successors, others were able to name multiple individuals. As a result, when the responses were considered collectively, a relatively large body of potential CFO talent was identified, albeit with different timelines associated with full CFO readiness. The challenge ahead is not only to identify and facilitate the most efficient means to accelerate this state of readiness, but to do so as a community where supply and demand for talent are managed more broadly for the betterment of the financial management function across government.

The Need to Actively Manage Ongoing Transformation

At the outset of the two OCG data collection efforts already mentioned, there was some perception within government of a shortage of potential future CFOs. The findings of the succession risk assessment and financial executive profile exercises put that perception to rest; there is no looming crisis in terms of the renewal of the current suite of CFOs and DCFOs. There is, however, work to be done.

There has been considerable movement in the CFO ranks in recent years, and the data collected indicates that this level of movement will be sustained for some time. As noted, although there are strong pools of feeder groups to fill these vacancies, the issue is candidates' readiness to assume the increasingly complex role of today's government CFO. As we move forward, we need to ensure that the transition is managed well. The solution is for the financial management community to take a well-coordinated and collective approach to CFO and DCFO talent management and succession planning.

The Office of the Comptroller General Has an Important Role to Play

A Community-Based Collective Response Is Key

The OCG is well positioned to lead this community-based initiative. As previously noted, it has the mandate to provide functional leadership and to support the development of sustainable capacity of the financial management community across government. In addition, the OCG has the perspective and expertise necessary to manage horizontally.

Whether it be in legislation or in policy, deputy heads' authorities, responsibilities and accountabilities, and those of the CFOs who support them, are always defined in terms of the departments they manage. It follows that, individually, their efforts in succession planning and talent management will be internally focused. However, given the common challenges faced by departments on this front, the solution can be delivered only through the community of departments acting collectively and collaboratively, a reality acknowledged by departments and endorsed by the Auditor General in her Status Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the House of Commons (June 2011):

Given that a number of senior financial executives within government departments will be eligible to retire in the near future, it is important that departments have succession strategies in place to prepare for those retirements. We found that departments are at various stages in the process of putting succession strategies in place. In our view, departments should collaborate with the Office of the Comptroller General to ensure they have succession strategies to meet future needs. (p. 22)

The feedback received from the CFOs who participated in the interviews was unequivocal: there is a considerable desire for—and, in the eyes of many, an expectation of—leadership from the OCG on the issues of CFO competency development, talent management and succession planning. CFOs offered a variety of suggestions on what role the OCG might play and even what specific activities it might undertake. This input will be valuable as the OCG moves forward with an approach that takes an enterprise-wide view while respecting the role of deputy heads and the individuality of departments.

Building on Progress

To support deputy heads in fulfilling their responsibilities as accounting officers and to nurture a strong, capable and sustainable CFO and DCFO suite, the OCG intends to undertake the following:

- Regularly collect and analyze demographic and other data on the financial management community to forecast anticipated vacancies in the CFO and DCFO suite, and assess the capacity of feeder groups to meet the challenge;

- Work with deputy heads, CFOs and DCFOs to develop viable succession plans, including identifying and assessing potential internal successors;

- Refine the competencies expected of a CFO, building on the existing framework for the four roles of the CFO (steward, operator, catalyst and strategist), and in collaboration with deputy heads and financial management executives. The existing "FI-to-CFO Career Path" (see Appendix B, "DCFO Council FI-to-CFO Career Path"), which was developed by the DCFO Council, provides a starting point from which to identify the incremental experience, skills and competencies required to support sound career progression. Over the longer term, the OCG would integrate the key competencies of the four-role CFO Competency Model into a revised FI-to-CFO career path that reflects the expectations of deputy heads and current CFOs to help ensure that there is a steady reserve of senior financial management talent;

- Develop a suite of learning strategies and tools to accelerate the development of high-potential individuals (based on the above framework) while expanding external recruitment efforts;

- Continue to use collective staffing processes to fill vacancies (particularly targeted at smaller departments and agencies) and create a pool of high-potential pre-qualified individuals;

- Continue to participate as a member of CFO selection committees to ensure continuity, provide the deputy head with objective advice, and identify high-potential candidates and any readiness gaps they may have so that individualized learning opportunities can be developed; and

- Implement a formal on-boarding process to help ensure that appointed candidates are able to successfully adapt to their new responsibilities.

Conclusion

The Government of Canada has made substantial progress in implementing the CFO Model and the new Policy on Financial Management Governance. The improvements we have seen in financial management practices and capacity are, to a large degree, a reflection of the community's ability to recruit and appoint the current cohort of highly qualified and competent CFOs.

The community's success in appointing over 100 CFOs in the last few years, in turn, depended on a pre-existing cohort of seasoned financial management executives. In the nomenclature of the time, these senior financial officers or senior full-time financial officers, although not CFOs, were the lead financial management executives within their organizations. We need to ensure that future cohorts are equally well prepared and fully understand the role of today's CFO and the expectations that accompany it. The rules of the game have changed; gone are the days of the financial executive as simply a scorekeeper. By identifying, addressing and closing any readiness gaps that could impede the current cohort of CFOs-in-waiting, we increase the likelihood of success in the pending demographically fuelled transition.

To this end, a community-based approach to CFO talent management and succession planning is required, and the OCG is best positioned to lead such an initiative. This paper has outlined a number of activities that the OCG is pursuing to better analyze this situation and to identify and fill anticipated vacancies. Concurrently, using its CFO Competency Model, the OCG will work with deputy heads to better understand their expectations so that high-potential internal candidates can be better prepared for the challenges they will invariably face as CFOs. Longer term, the plan is to incorporate these competencies into an FI-to-CFO career path so that a steady reserve of senior financial management talent is built over time.

Appendix A: Proposed Chief Financial Officer Competency Model

The following 6

Steward Role

The steward is oriented toward robust resource management, control rationalization and financial information quality:

Resource Management

- Budgeting and forecasting

- Resource supply (Estimates)

- Expenditure management

- Cash management

- Financial analysis and advice

- Investment proposal and challenge

- Costing, pricing and cost-benefit analysis

- Preparation of Treasury Board submissions and memoranda to Cabinet

Controls

- Financial management control frameworks (including processes and internal controls over financial reporting)

- Internal audit

- Fraud prevention and detection

Accounting and Reporting

- Financial accounting principles and standards (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles and Treasury Board Accounting Standards)

- Performance measurement processes and methods

- Internal financial monitoring and reporting

- Financial statements preparation and analysis

- Statutory reporting (Reports on Plans and Priorities, Departmental Performance Reports, proactive disclosure)

Operator Role

The operator is oriented toward best practices of the entire finance function itself:

- Accounting operations

- Revenue management

- Grants and contributions management

- Procurement management

- Asset management (real property, investments, etc.)

- People management

Catalyst Role

The catalyst is oriented toward best practices of the entire organization:

- Financial systems development and implementation

- Continuous improvement processes and methods

- Change management

- Relationship building and collaboration with internal and external stakeholders and central agencies

- Communication and presentation skills and executive presence

Strategist Role

The strategist is oriented toward long-term, strategic issues and is outwardly directed:

- Corporate governance

- Corporate goal setting and visioning

- Strategic risk management (assessment and mitigation)

- Financial information needs of decision makers