Demographic Snapshot of Canada’s Public Service, 2023

Preamble

This snapshot provides key demographics for Canada’s federal public service and supplements the Clerk of the Privy Council’s Thirty-first Annual Report to the Prime Minister on the Public Service of Canada.

The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO) works in partnership with departments and agencies to access, analyze, and share federal public service workforce data to identify current workforce trends. In the coming year, the public service will aim to recruit and equip the next generation of federal public servants to carry out the Government of Canada’s priorities. In the process, there will be an increased focus on ensuring that the public service is diverse and inclusive and reflects the population it serves.

On this page

Introduction

This snapshot compares the current workforce with that of the baseline year of 2010. The data in this snapshot is current as of March 31, 2023, unless indicated otherwise.

Part 1 of this document covers all employees of the entire federal public service (the core public administration and separate agencies), and Part 2 focuses on executives. Part 3 provides highlights from the 2022/2023 Public Service Employee Survey and the 2023 Student Experience Survey.

Canada’s federal public service consists of two population segments:

- the core public administration; and

- separate agencies.

The term “core public administration” refers to approximately 70 departments and agencies for which the Treasury Board is the employer. These organizations are listed in Schedules I and IV of the Financial Administration Act. More information on this segment of the population is available in the Interactive data visualization tool.

The term “separate agencies” refers to agencies listed in Schedule V of the Financial Administration Act. Separate agencies conduct their own negotiations and may set their own classification system and compensation levels for their employees.

The principal separate agencies are:

- Canada Revenue Agency;

- Parks Canada;

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency; and

- National Research Council Canada.

Population counts for the following separate agencies are not included because their employee information is not available in the Pay system:

- Canadian Security Intelligence Service;

- National Capital Commission;

- Canada Investment and Savings; and

- Canadian Forces Non‑Public Funds.

The data does not include:

- ministers’ exempt staff;

- employees locally engaged outside Canada;

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) regular force members;

- RCMP civilian force members; and

- Canadian Armed Forces members.

Highlights from 2023

-

In this section

Number of employees

- 357,247 active employees (282,980 in 2010)

- Represents 0.90% of the Canadian population (0.83% in 2010)

Location of work

- 57.5% of employees are in the regionsFootnote 1 (59.4% in 2010)

- 42.5% of employees are in the National Capital Region (40.6% in 2010)

Employment type

- 81.5% are indeterminate employees (86.2% in 2010)

- 13.5% are term employees (9.1% in 2010)

- 5.0% are casuals and students (4.7% in 2010)

WomenFootnote 2

- 56.8% of employees are women (55.2% in 2010)

- 53.5% of executives are women (43.8% in 2010)

Official languagesFootnote 3

- 71.8% of employees indicated English as their first official language (71.0% in 2010)

- 28.2% of employees indicated French as their first official language (29.0% in 2010)

AgeFootnote 4

- The average age of employees is 43.3 years (43.9 years in 2010)

- The average age of executives is 49.9 years (50.1 years in 2010)

Part 1: Federal public service

Relative size and spending

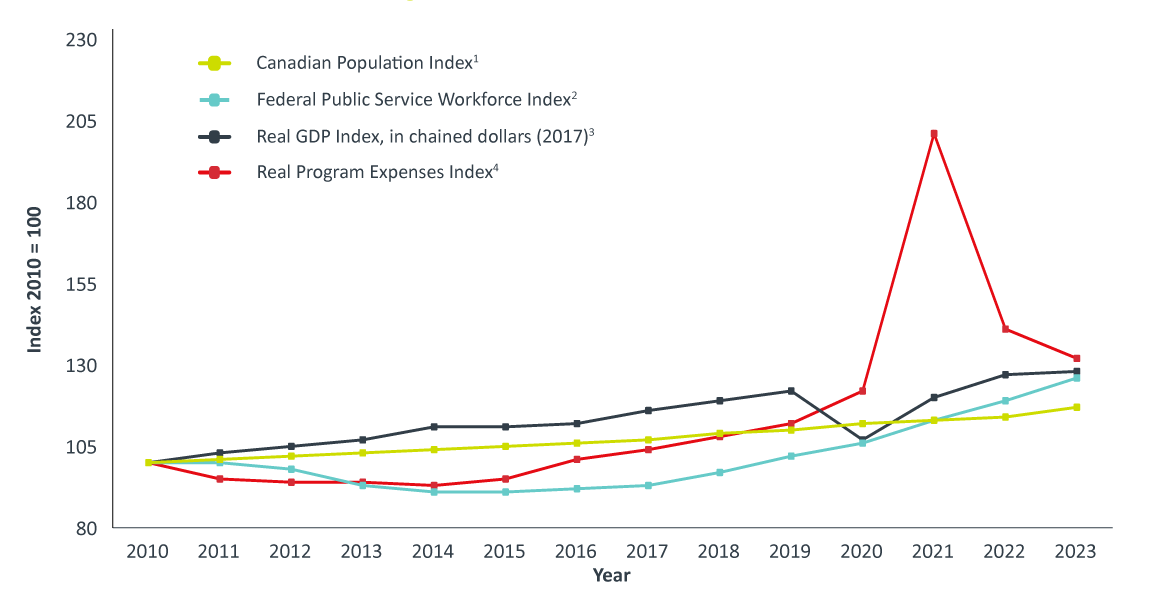

Between 2010 and 2023:

- the population of Canada grew from approximately 33.9 million to 39.8 million (an increase of 17.3%)Footnote 5; and

- the number of federal public servants increased from 282,980 to 357,247 (an increase of 26.2%).Footnote 6

The federal public service comprised 0.90% of the Canadian population in 2023. Over the last 10 years, the size of the federal public service in relation to the Canadian population fluctuated but it now represents a greater proportion of the Canadian population than in 2010 when it represented 0.83%.

Between 2010 and 2023:

- Canada’s real gross domestic product (GDP) increased by 28.1%Footnote 7; and

- real federal program expenses increased by 32.2% (in constant dollars)Footnote 8.

Most recently, from 2022 to 2023, there was:

- an increase of 1.3% in real gross domestic product; and

- a decrease of 6.1% in real federal program expenses.

Since the 2010 to 2015 period, where the workforce decreased in response to budget reductions, there has been an increase in the federal public service workforce. In the last year the workforce increased by 6.3%.

Figure 1 shows trends in the economy, the Canadian population, real federal program expenses and the size of the federal public service, from 2010 to 2023.

Figure 1 - Text version

| Year | Canadian Population Indextable 1 note 1 | Federal Public Service Workforce Indextable 1 note 2 | Real GDP Index, in chained dollars (2012)table 1 note 3 | Real Program Expenses Indextable 1 note 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 2011 | 101 | 100 | 103 | 95 |

| 2012 | 102 | 98 | 105 | 94 |

| 2013 | 103 | 93 | 107 | 94 |

| 2014 | 104 | 91 | 111 | 93 |

| 2015 | 105 | 91 | 111 | 95 |

| 2016 | 106 | 92 | 112 | 101 |

| 2017 | 107 | 93 | 116 | 104 |

| 2018 | 109 | 97 | 119 | 108 |

| 2019 | 110 | 102 | 122 | 112 |

| 2020 | 112 | 106 | 107 | 122 |

| 2021 | 113 | 113 | 120 | 201 |

| 2022 | 114 | 119 | 127 | 141 |

| 2023 | 117 | 126 | 128 | 132 |

Table 1 Notes

- Table 1 Note 1

-

Based on data as of April 1 for each year.

- Table 1 Note 2

-

Based on active employees only and data as of March 31 for each year.

- Table 1 Note 3

-

Based on data as of April 1 for each year.

- Table 1 Note 4

-

Based on fiscal year data. Real program expenses were adjusted using Statistic Canada's gross domestic product (GDP) as market price indexes in 2017 chained dollars.

Sources: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat; Statistics Canada (Table 17-10-0009-01 Population estimates, quarterly; Table 36-10-0104-01 Gross domestic product, expenditure-based, Canada, quarterly; Table 36-10-0106-01 Gross domestic product price indexes, quarterly; and Department of Finance Canada (Fiscal Reference Tables).

Diversity in the federal public service

Sex

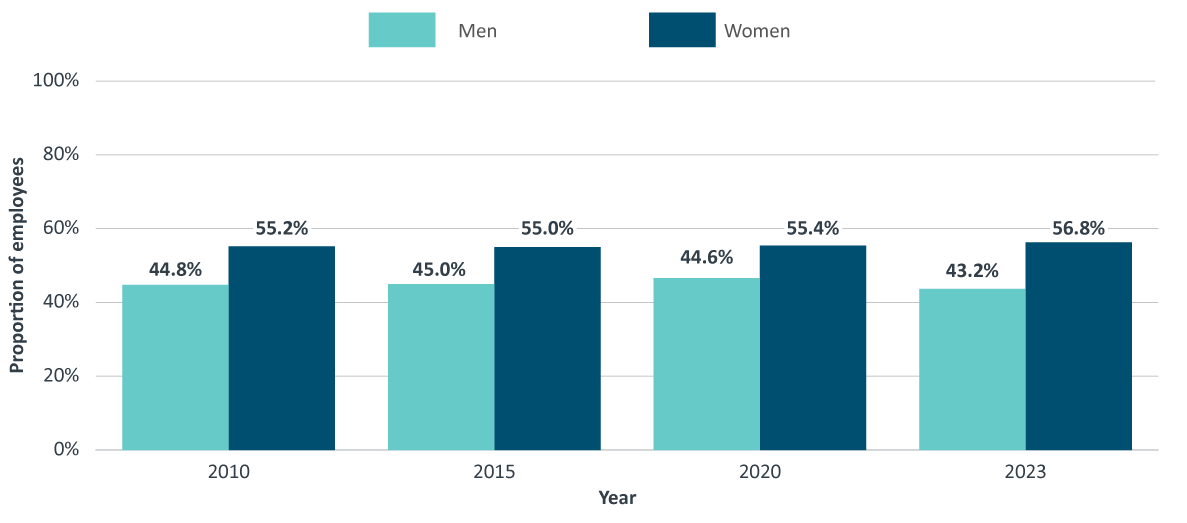

As shown in Figure 2, in 2023, women made up 56.8% of the federal public service, a 1.6 percentage point increase from 2010.

Figure 2 - Text version

| Sex | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 44.8% | 45.0% | 44.6% | 43.2% |

| Women | 55.2% | 55.0% | 55.4% | 56.8% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Technical notes:

Population: Includes all employment tenures and active employees only (employees on leave without pay are excluded).

The information provided excludes employees of unknown sex and is based on data as of March 31.

Employment equity designated groups

Representation

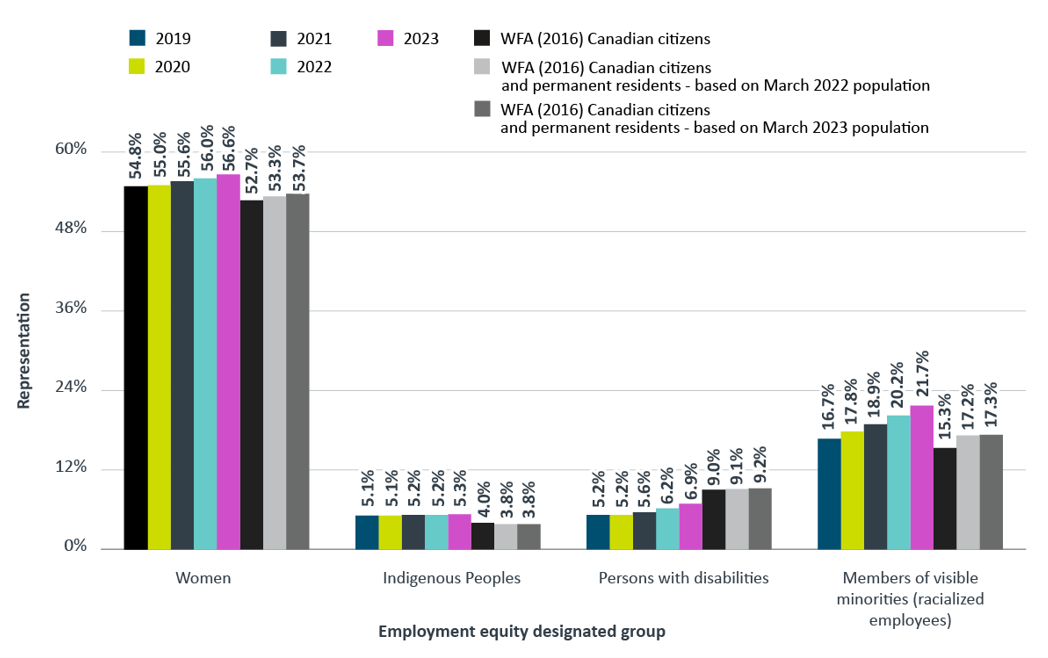

Figure 3 shows that there have been increases in the representation levels of all four employment equity designated groups in the core public administration since 2019.

The representation rate for women was slightly higher than the previous year while the representation rate of persons with disabilities increased from 6.2% in 2022 to 6.9% in 2023. As well, representation rates for members of visible minorities showed an increase for the last five consecutive years. However, the representation rate of Indigenous Peoples in the core public administration remained relatively stable over the last five years.

Overall, representation of the employment equity groups (women, Indigenous Peoples and members of visible minorities) continue to exceed their respective workforce availability estimatesFootnote 9 with the exception of persons with disabilities.

Figure 3 - Text version

| Employment equity designated group | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | WFA (2016) Canadian citizens | WFA (2016) Canadian citizens and permanent residents - based on March 2022 population | WFA (2016) Canadian citizens and permanent residents - based on March 2023 population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 54.8% | 55.0% | 55.6% | 56.0% | 56.6% | 52.7% | 53.3% | 53.7% |

| Indigenous Peoples | 5.1% | 5.1% | 5.2% | 5.2% | 5.3% | 4.0% | 3.8% | 3.8% |

| Persons with disabilities | 5.2% | 5.2% | 5.6% | 6.2% | 6.9% | 9.0% | 9.1% | 9.2% |

| Members of visible minorities (racialized employees) | 16.7% | 17.8% | 18.9% | 20.2% | 21.7% | 15.3% | 17.2% | 17.3% |

Source: Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat Pay system as of March 31 of each year and Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat Employment Equity Data Bank (EEDB).

Population: The information includes indeterminates, terms of three months or more, and seasonal employees of organizations captured under the Financial Administration Act, Schedules I and IV (core public administration). Excluded from this information are employees on leave without pay, terms less than 3 months, students and casual workers, Governor in Council appointees, Ministers’ exempt staff, federal judges and deputy ministers.

The data in this table covers employees identified for the purpose of employment equity in the regulations to the Employment Equity Act.

Technical notes:

Internal representation for Indigenous Peoples, persons with disabilities and members of visible minorities is based on those who have voluntarily chosen to self-identify in one of the respective employment equity groups, while sex information is taken from the Pay system.

The 2016 workforce availability estimates (WFA) are based on information from the 2016 Census of Canada and the 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability. Workforce availability estimates include Canadian citizens and starting in 2022, permanent residents, in those occupations in the Canadian workforce that correspond to occupations in the core public administration.

The 2016 WFA based on Canadian citizens only is the relevant comparison for 2019, 2020 and 2021. The 2016 WFA based on Canadian citizens and permanent residents based on the March 2022 population is the relevant comparison for 2022, while the 2016 WFA based on Canadian citizens and permanent residents based on the March 2023 population is the relevant comparison for 2023.

Hiring

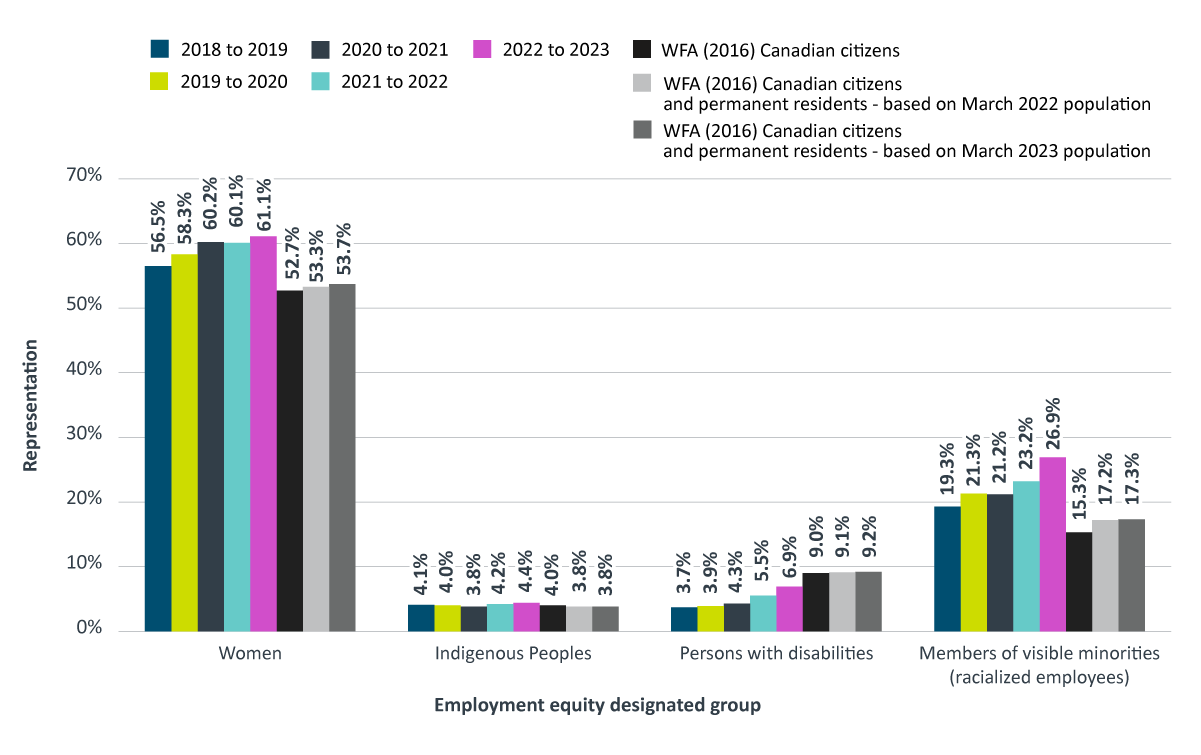

Figure 4 shows that the proportion of new hires for indeterminate and term positions of three months or more remains above or equal to the current workforce availability estimates of all employment equity designated groups except for persons with disabilities, which remains below the group’s current workforce availability.

Figure 4 - Text version

| Employment equity designated group | 2018 to 2019 | 2019 to 2020 | 2020 to 2021 | 2021 to 2022 | 2022 to 2023 | WFA (2016) Canadian citizens | WFA (2016) Canadian citizens and permanent residents - based on March 2022 population | WFA (2016) Canadian citizens and permanent residents - based on March 2023 population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 56.5% | 58.3% | 60.2% | 60.1% | 61.1% | 52.7% | 53.3% | 53.7% |

| Indigenous Peoples | 4.1% | 4.0% | 3.8% | 4.2% | 4.4% | 4.0% | 3.8% | 3.8% |

| Persons with disabilities | 3.7% | 3.9% | 4.3% | 5.5% | 6.9% | 9.0% | 9.1% | 9.2% |

| Members of visible minorities (racialized employees) | 19.3% | 21.3% | 21.2% | 23.2% | 26.9% | 15.3% | 17.2% | 17.3% |

Source: Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat Pay system, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat Employment Equity Data Bank (EEDB) and the Public Service Commission of Canada’s files on hiring and staffing activities.

Population: The information includes indeterminates, terms of three months or more, and seasonal employees of organizations captured under the Financial Administration Act, Schedules I and IV (core public administration).

Technical notes:

Internal representation for Indigenous Peoples, persons with disabilities and members of visible minorities is based on those who have voluntarily chosen to self-identify in one of the respective employment equity groups, while sex information is taken from the Pay system.

“Employees hired” refers to employees who were added to the public service of Canada payroll between April 1 and March 31 of each given fiscal year.

Percentages are that designated group’s share of all hires.

The 2016 workforce availability estimates (WFA) are based on information from the 2016 Census of Canada and the 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability. Workforce availability estimates include only Canadian citizens and starting in 2022, permanent residents, in those occupations in the Canadian workforce that correspond to occupations in the core public administration.

The 2016 WFA based on Canadian citizens only is the relevant comparison for the 2018 to 2019, 2019 to 2020 and 2020 to 2021 fiscal years. The 2016 WFA based on Canadian citizens and permanent residents based on the March 2022 population is the relevant comparison for the 2021 to 2022 fiscal year, while the 2016 WFA based on Canadian citizens and permanent residents based on the March 2023 population is the relevant comparison for the 2022 to 2023 fiscal year.

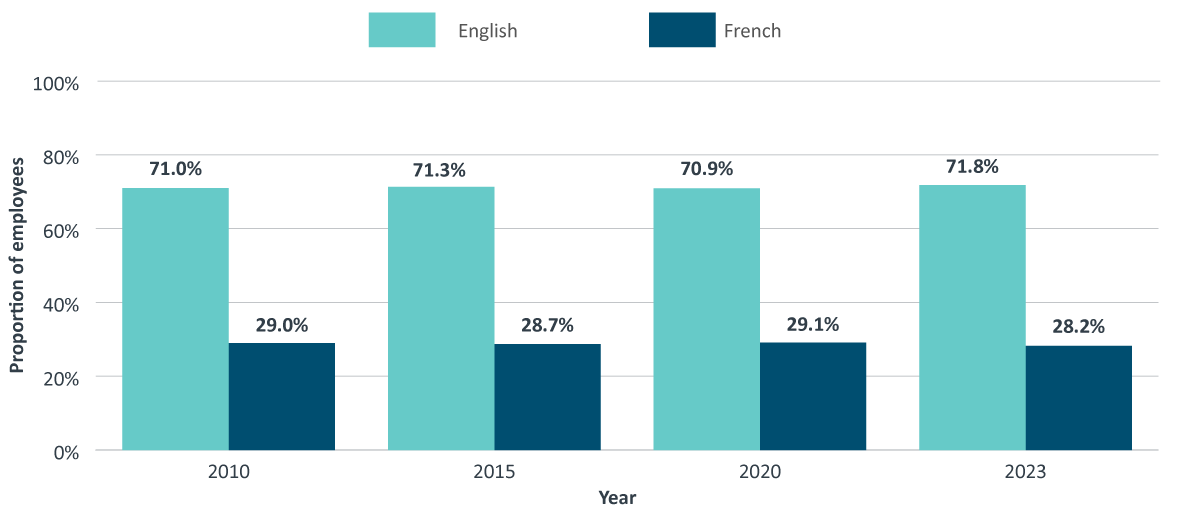

First official language

As shown in Figure 5, the breakdown of federal public servants by first official language is consistent across the years. In 2023, 71.8% of federal public servants’ first official language was English, while 28.2% was French.

Figure 5 - Text version

| First official language | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | 71.0% | 71.3% | 70.9% | 71.8% |

| French | 29.0% | 28.7% | 29.1% | 28.2% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Technical notes:

Population: Includes all employment tenures and active employees only (employees on leave without pay are excluded).

The information provided excludes employees with an unknown first official language and is based on data as of March 31.

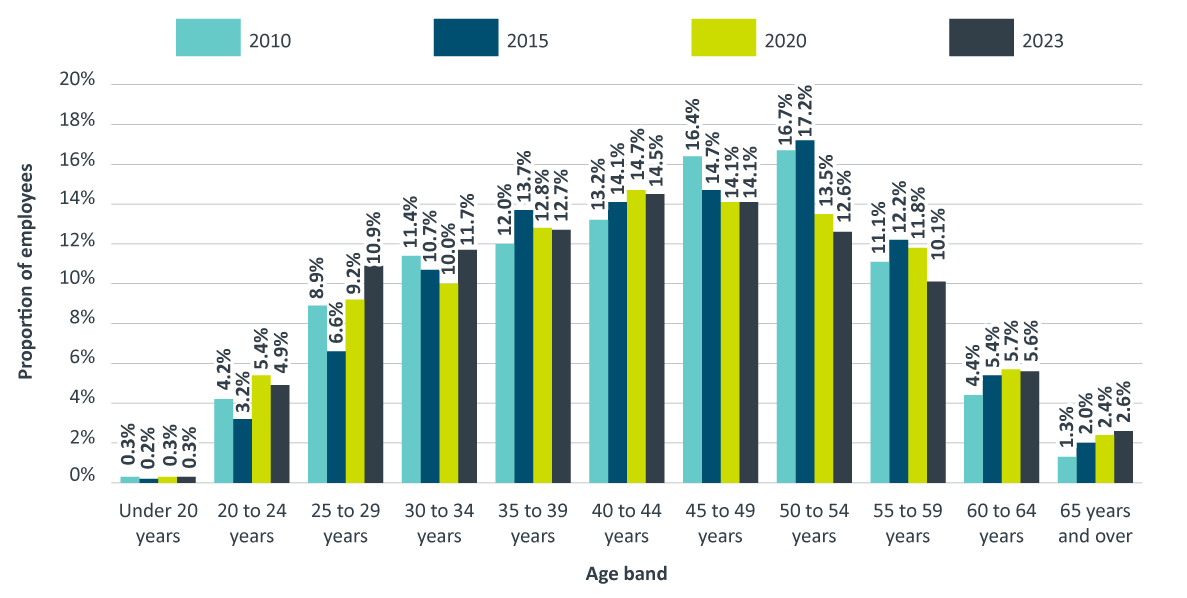

Age of federal public servants

Figure 6 compares the breakdown of federal public servants in 2010, 2015, 2020 and 2023 by age. From 2010 to 2023, the age breakdown changed slightly, with:

- a decrease in the proportion of employees aged 45 to 59 years; and

- an increase in the proportion of employees under the age of 45 years and those above the age of 60 years.

The average age of federal public servants increased slightly between 2010 and 2015 (from 43.9 years in 2010, to 45.0 years in 2015) and then decreased between 2015 and 2023 from 45.0 years in 2015 to 43.3 years in 2023.

Figure 6 - Text version

| Age band | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 20 years | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| 20 to 24 years | 4.2% | 3.2% | 5.4% | 4.9% |

| 25 to 29 years | 8.9% | 6.6% | 9.2% | 10.9% |

| 30 to 34 years | 11.4% | 10.7% | 10.0% | 11.7% |

| 35 to 39 years | 12.0% | 13.7% | 12.8% | 12.7% |

| 40 to 44 years | 13.2% | 14.1% | 14.7% | 14.5% |

| 45 to 49 years | 16.4% | 14.7% | 14.1% | 14.1% |

| 50 to 54 years | 16.7% | 17.2% | 13.5% | 12.6% |

| 55 to 59 years | 11.1% | 12.2% | 11.8% | 10.1% |

| 60 to 64 years | 4.4% | 5.4% | 5.7% | 5.6% |

| 65 years and over | 1.3% | 2.0% | 2.4% | 2.6% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Technical notes:

Population: Includes all employment tenures and active employees only (employees on leave without pay are excluded).

The information provided excludes employees with an unknown age and is based on data as of March 31.

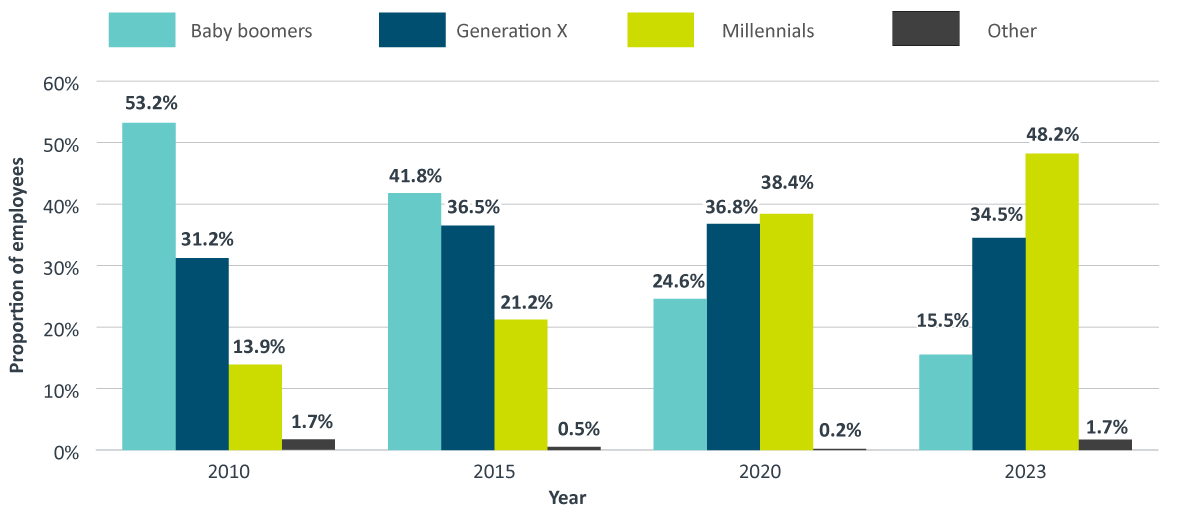

Figure 7 shows the distribution of federal public servants by generation for 2010, 2015, 2020 and 2023. Up until 2015, baby boomers (people born between 1946 and 1966) made up the largest group of federal public servants. However, they are being replaced by Generation Xers (people born between 1967 and 1979) and millennials (people born between 1980 and 2000). Millennials now represent the largest group of public servants (48.2%) followed by Generation Xers (34.5%).

Figure 7 - Text version

| Generation | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baby boomers | 53.2% | 41.8% | 24.6% | 15.5% |

| Generation X | 31.2% | 36.5% | 36.8% | 34.5% |

| Millennials | 13.9% | 21.2% | 38.4% | 48.2% |

| Other | 1.7% | 0.5% | 0.2% | 1.7% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Technical notes:

Population: Includes all employment tenures and active employees only (employees on leave without pay are excluded).

The information provided excludes employees with an unknown age and is based on data as of March 31.

“Other” includes employees who were born in other generations (i.e., the Greatest generation, Traditionalists and Generation Z).

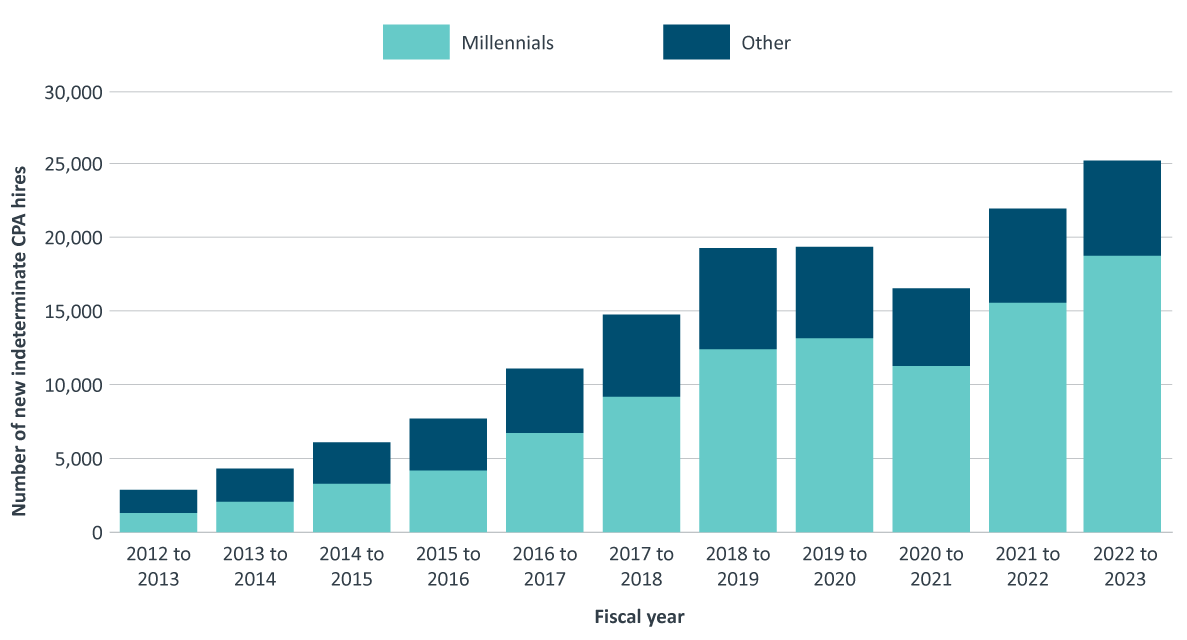

Hiring into the core public administration

Figure 8 shows new indeterminate hiring in the core public administration over time. Indeterminate hiring has been on the rise since the 2012 to 2013 fiscal year. There was a decline in indeterminate hires between the 2019 to 2020 fiscal year and the 2020 to 2021 fiscal year, however it has since risen. New indeterminate hiring in the core public administration increased by 14.6%, from 21,925 in the 2021 to 2022 fiscal year to 25,125 in the 2022 to 2023 fiscal year.

Figure 8 - Text version

| Generation | 2012 to 2013 | 2013 to 2014 | 2014 to 2015 | 2015 to 2016 | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | 2018 to 2019 | 2019 to 2020 | 2020 to 2021 | 2021 to 2022 | 2022 to 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Millennials | 1,284 | 2,060 | 3,274 | 4,168 | 6,712 | 9,169 | 12,381 | 13,127 | 11,247 | 15,532 | 18,451 |

| Other | 1,581 | 2,255 | 2,819 | 3,530 | 4,373 | 5,580 | 6,864 | 6,206 | 5,281 | 6,393 | 6,674 |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Technical notes:

Population: Includes new indeterminate core public administration hires only.

Generation information is based on an employee's age at the time they were hired.

"Other" includes employees who were born in all generations (i.e., the Greatest generation, Traditionalists, Baby boomers, Generation X and Generation Z) except for millennials. "Other" also includes employees with an unknown age.

The proportion of new indeterminate hires who are millennials increased from 70.8% in the 2021 to 2022 fiscal year to 73.4% in the 2022 to 2023 fiscal year. During this same period:

- the proportion of new indeterminate hires from the baby boomer generation decreased from 6.2% to 4.7%; and

- the proportion of hires who are Generation Xers decreased from 22.5% to 20.7%.Footnote 10

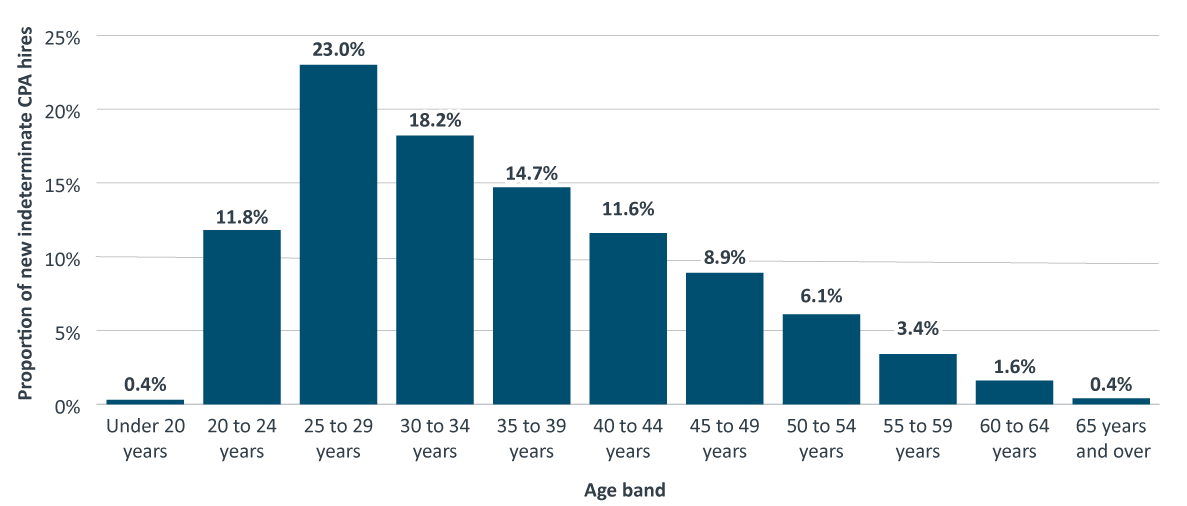

Figure 9 shows the entire age distribution of new indeterminate hires in the core public administration. The median age was 34.0 years.

Figure 9 - Text version

| Age band | Proportion of new indeterminate CPA hires |

|---|---|

| Under 20 years | 0.4% |

| 20 to 24 years | 11.8% |

| 25 to 29 years | 23.0% |

| 30 to 34 years | 18.2% |

| 35 to 39 years | 14.7% |

| 40 to 44 years | 11.6% |

| 45 to 49 years | 8.9% |

| 50 to 54 years | 6.1% |

| 55 to 59 years | 3.4% |

| 60 to 64 years | 1.6% |

| 65 years and over | 0.4% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Technical notes:

Population: Includes new indeterminate core public administration hires only.

The information provided excludes employees with an unknown age.

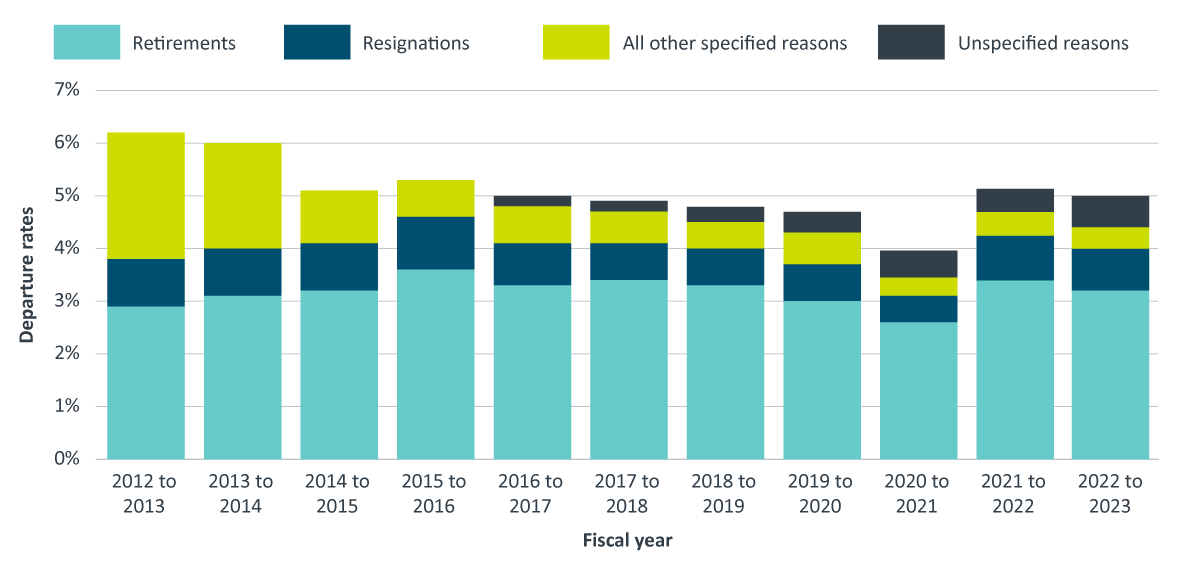

Departures from the federal public service

Retirements accounted for 66.0% of departures while resignations accounted for 18.2% in the 2022 to 2023 fiscal year.

Since the 2012 to 2013 and the 2013 to 2014 period, where the number of departures from the federal public service increased in response to budget reductions, there has been a steady decrease of departures from the federal public service workforce up until the 2020 to 2021 fiscal year. Between the 2020 to 2021 fiscal year and the 2022 to 2023 fiscal year, the number of departures has increased by 33.9%.

As shown in Figure 10, in the 2022 to 2023 fiscal year, the federal public service departure rates for retirements, resignations, all other specified reasons and unspecified reasons were 2.9%, 0.8%, 0.2% and 0.5%, respectively.

Figure 10 - Text version

| Departure type | 2012 to 2013 | 2013 to 2014 | 2014 to 2015 | 2015 to 2016 | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | 2018 to 2019 | 2019 to 2020 | 2020 to 2021 | 2021 to 2022 | 2022 to 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retirements | 2.9% | 3.1% | 3.2% | 3.6% | 3.4% | 3.4% | 3.3% | 3.1% | 2.6% | 3.2% | 2.9% |

| Resignations | 0.9% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 1.0% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.5% | 0.7% | 0.8% |

| All other specified reasons | 2.4% | 2.0% | 1.0% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% |

| Unspecified reasons | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.5% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Technical notes:

Population: Indeterminate federal public servants, including employees who departed (retired, resigned left for other specified and unspecified reasons) while active or on leave without pay.

“Unspecified reasons” are instances where the departure reasons have not been provided.

Departure figures and rates from fiscal year 2016 to 2017 onwards are subject to change.

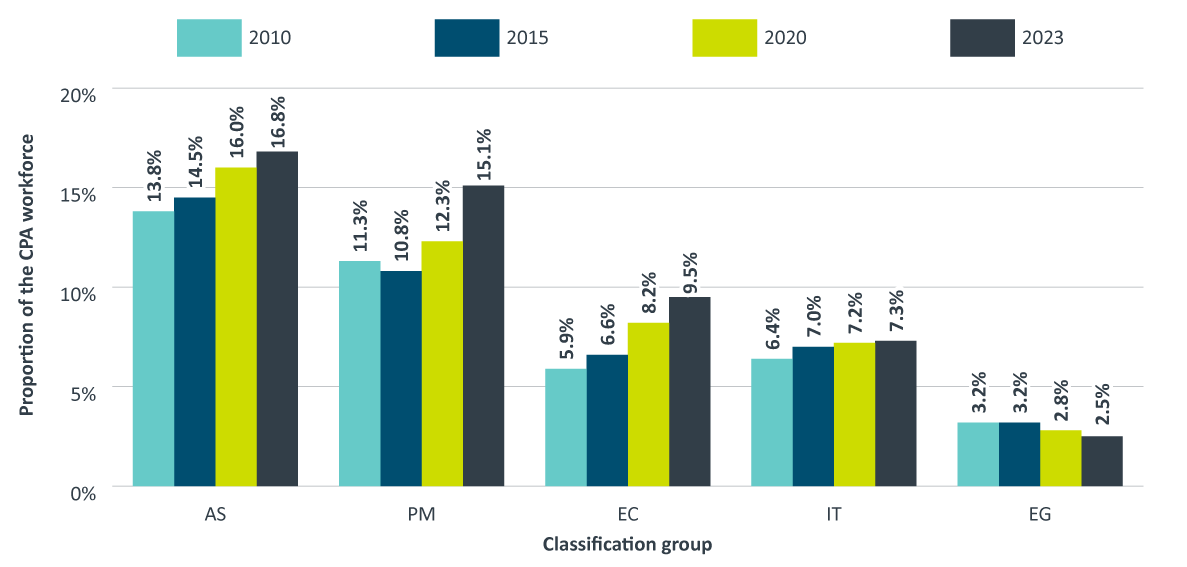

Knowledge-intensive workforce in the core public administration

In 1990, the public service workforce was composed mainly of clerical and operational workers. Since then, employees undertaking more knowledge-intensive work comprise an ever-increasing share of employees in the core public administration. The cadre of knowledge workers is highly skilled, with significant expertise gained through a combination of education, training and experience. The transformation in work has been in response to:

- an increasingly demanding environment;

- new challenges; and

- technological advances since 2000.

As shown in Figure 11, the five largest knowledge-intensive classification groups in the core public administration are:

- Administrative Services (AS);

- Program Administration (PM);

- Economics and Social Science Services (EC);

- Information Technology (IT)Footnote 11; and

- Engineering and Scientific Support (EG).

In 2023, these classification groups represented 51.1% of the core public administration workforce and in 2010, they represented only 40.7%.

Figure 11 - Text version

| Classification group | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | 13.8% | 14.5% | 16.0% | 16.8% |

| PM | 11.3% | 10.8% | 12.3% | 15.1% |

| EC | 5.9% | 6.6% | 8.2% | 9.5% |

| IT | 6.4% | 7.0% | 7.2% | 7.3% |

| EG | 3.2% | 3.2% | 2.8% | 2.5% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Technical notes:

Population: Includes all employment tenures and active employees only (employees on leave without pay are excluded), based on effective employment classification (acting appointments are included).

The information provided is based on data as of March 31.

On June 22, 2009, the Economics, Sociology and Statistics (ES) and the Social Science Support (SI) classification groups were combined to form the Economics and Social Science Services (EC) classification group.

The Computer Systems (CS) group changed to a new classification group called Information Technology (IT).

Part 2: Executives

-

In this section

This section provides demographic information about the federal public service’s Executive groupFootnote 12.

Typically, assistant deputy ministers (classified as EX-04 and EX-05) fulfill senior leadership functions, providing strategic direction and oversight. Directors, executive directors and directors general (classified from EX-01 to EX-03) fulfill executive functions and are responsible for managing employees.

Population size of the executive group

As of March 31, 2023, there were 9,069 executives in the federal public service:

- about half of them (50.6%) were EX-01s; and

- only 5.7% were EX-04s and EX-05s.

As of March 31, 2023, executives accounted for 2.5% of the federal public service.

Between 2010 and 2023, the federal public service workforce grew by 26.2%, while the executive population grew by 33.9% over this same period.

Executive diversity

Employment equity designated groups among core public administration executives

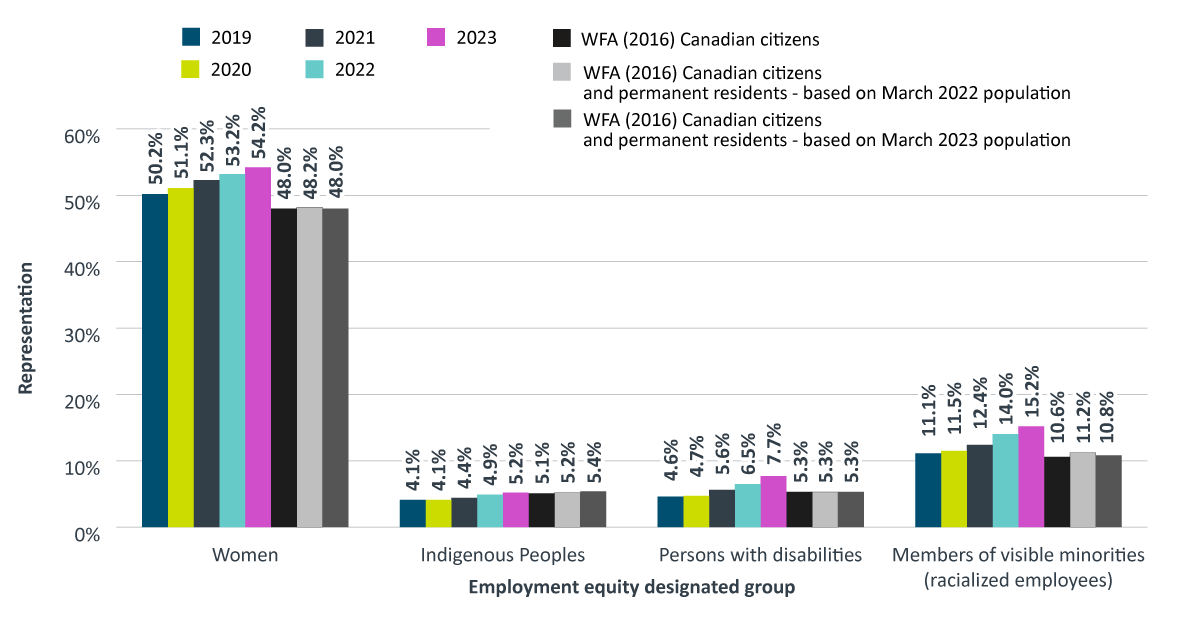

Figure 12 illustrates the levels of executive representation in the core public administration for all four employment equity groups from 2019 to 2023.

In 2023, the core public administration representation levels for women, persons with disabilities and members of visible minorities in the executive category exceeded their respective workforce availability, while representation of Indigenous Peoples fell short of their workforce availability.

Compared with 2022, the representation levels of all four designated groups at the executive level increased.

Figure 12 - Text version

| Employment equity designated group | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | WFA (2016) Canadian citizens | WFA (2016) Canadian citizens and permanent residents - based on March 2022 population | WFA (2016) Canadian citizens and permanent residents - based on March 2023 population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 50.2% | 51.1% | 52.3% | 53.2% | 54.2% | 48.0% | 48.2% | 48.0% |

| Indigenous Peoples | 4.1% | 4.1% | 4.4% | 4.9% | 5.2% | 5.1% | 5.2% | 5.4% |

| Persons with disabilities | 4.6% | 4.7% | 5.6% | 6.5% | 7.7% | 5.3% | 5.3% | 5.3% |

| Members of visible minorities (racialized employees) | 11.1% | 11.5% | 12.4% | 14.0% | 15.2% | 10.6% | 11.2% | 10.8% |

Source: Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat Pay system as of March 31 of each year and Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat Employment Equity Data Bank (EEDB).

Population: The information includes indeterminates, terms of three months or more, and seasonal employees of organizations captured under the Financial Administration Act, Schedules I and IV (core public administration). Excluded from this information are employees on leave without pay, terms less than 3 months, students and casual workers, Governor in Council appointees, Ministers’ exempt staff, federal judges and deputy ministers.

The data in this table covers employees identified for the purpose of employment equity in the regulations to the Employment Equity Act.

Technical notes:

Internal representation for Indigenous Peoples, persons with disabilities and members of visible minorities is based on those who have voluntarily chosen to self-identify in one of the respective employment equity groups, while sex information is taken from the Pay system.

The Law Management (LC) group has been included as part of the executive workforce since the 2011 to 2012 fiscal year.

The 2016 workforce availability estimates (WFA) are based on information from the 2016 Census of Canada and the 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability. Workforce availability estimates include Canadian citizens and starting in 2022, permanent residents, in those occupations in the Canadian workforce that correspond to occupations in the core public administration.

The 2016 WFA based on Canadian citizens only is the relevant comparison for 2019, 2020 and 2021. The 2016 WFA based on Canadian citizens and permanent residents based on the March 2022 population is the relevant comparison for 2022, while the 2016 WFA based on Canadian citizens and permanent residents based on the March 2023 population is the relevant comparison for 2023.

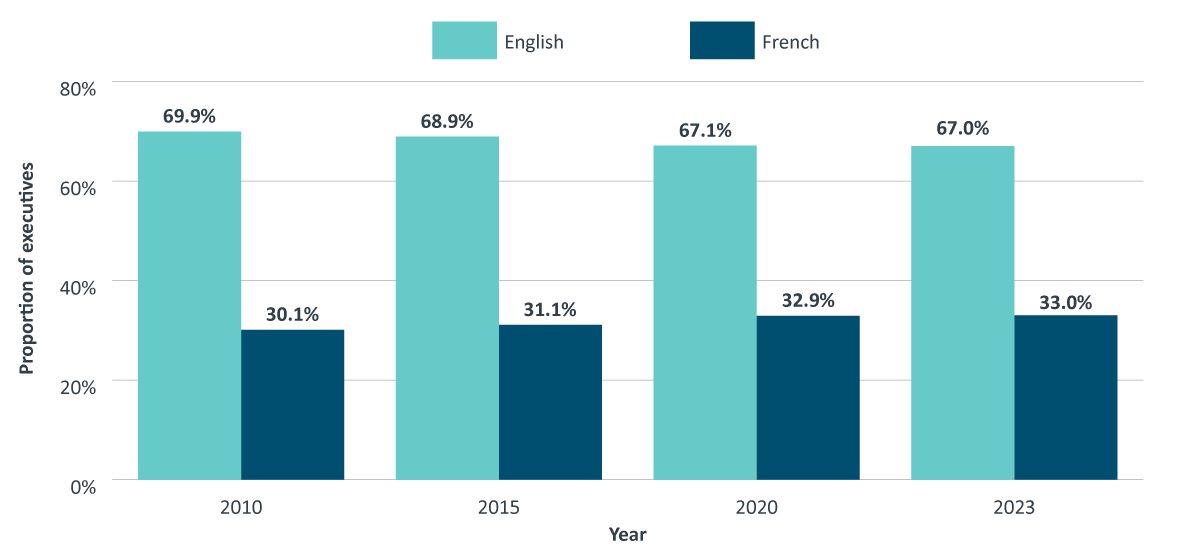

First official language of executives

As shown in Figure 13, between 2010 and 2023 the proportion of executives in the federal public service who indicated that French is their first official language increased from 30.1% to 33.0%. This trend was not seen for the overall federal public service for the same period of time. The proportion of federal public servants who indicated that French was their first official language decreased slightly from 29.0% in 2010 to 28.2% in 2023.

Figure 13 - Text version

| First official language | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | 69.9% | 68.9% | 67.1% | 67.0% |

| French | 30.1% | 31.1% | 32.9% | 33.0% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Technical notes:

Population: Includes all federal public service executives, specifically, core public administration executives and their equivalents in separate agencies (such as Executive group (EX) and Management group (MG) classifications) in all tenures (indeterminate, term and casual). It does not include executives on leave without pay or executives with an unknown first official language.

The information provided is based on data as of March 31.

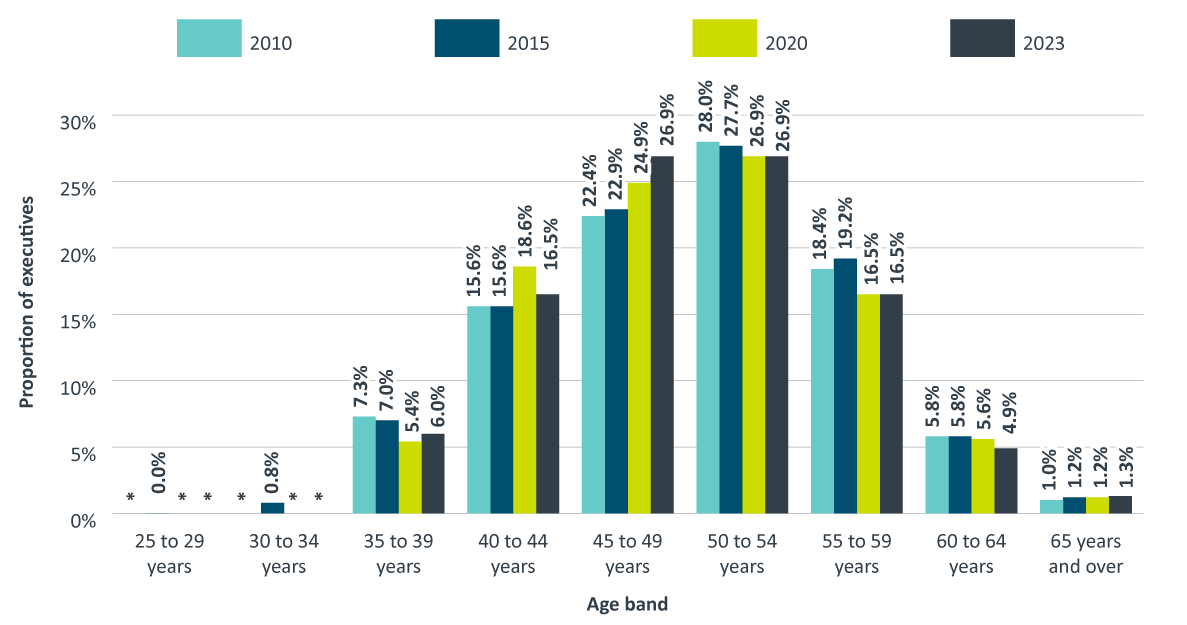

Age of executives in federal public service

Figure 14 shows the age breakdown of federal public service executives for 2010, 2015, 2020 and 2023. The proportion of executives between 40 and 49 years of age and 65 years and older have increased between 2010 and 2023, while the proportion of executives between 35 and 39 years of age and between 50 and 64 years of age has decreased.

* Information for small numbers has been suppressed (counts of 1 to 5). Additionally, to avoid residual disclosure, other data points, may also be suppressed.

Figure 14 - Text version

| Age band | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 to 29 years | * | 0.0% | * | * |

| 30 to 34 years | * | 0.8% | * | * |

| 35 to 39 years | 7.3% | 7.0% | 5.4% | 6.0% |

| 40 to 44 years | 15.6% | 15.6% | 18.6% | 16.5% |

| 45 to 49 years | 22.4% | 22.9% | 24.9% | 26.9% |

| 50 to 54 years | 28.0% | 27.7% | 26.9% | 26.9% |

| 55 to 59 years | 18.4% | 19.2% | 16.5% | 16.5% |

| 60 to 64 years | 5.8% | 5.8% | 5.6% | 4.9% |

| 65 years and over | 1.0% | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.3% |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Technical notes:

Population: Includes all federal public service executives, specifically, core public administration executives and their equivalents in separate agencies (such as Executive group (EX) and Management group (MG) classifications) in all tenures (indeterminate, term and casual). It does not include executives on leave without pay.

The information provided excludes employees with an unknown age and is based on data as of March 31.

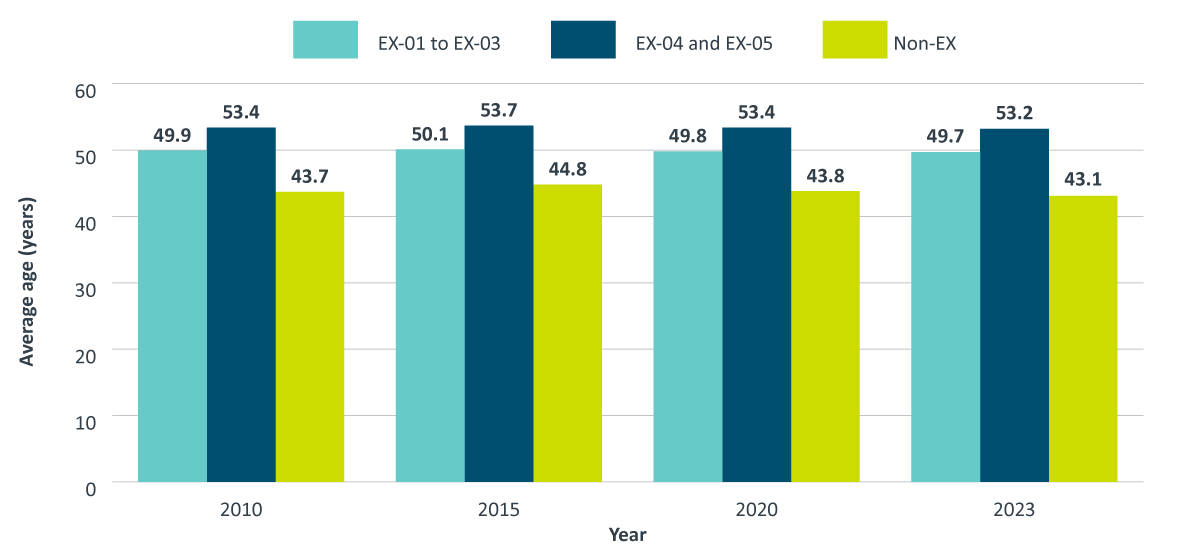

Figure 15 shows that between 2010 and 2023:

- the average age of junior executives at the EX-01 to EX-03 levels in the federal public service remained stable at approximately 50 years of age;

- the average age of senior executives at the EX-04 to EX-05 levels remained between 53 and 54 years of age; and

- the average age of non-executives remained between 43 and 45 years of age.

Figure 15 - Text version

| Executive level | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EX-01 to EX-03 | 49.9 | 50.1 | 49.8 | 49.7 |

| EX-04 and EX-05 | 53.4 | 53.7 | 53.4 | 53.2 |

| Non-EX | 43.7 | 44.8 | 43.8 | 43.1 |

Source: Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

Technical notes:

Population: Includes all federal public service executives, specifically, core public administration executives and their equivalents in separate agencies (such as Executive group (EX) and Management group (MG) classifications) in all tenures (indeterminate, term and casual). The population does not include executives on leave without pay.

The information provided excludes employees with an unknown age and is based on data as of March 31.

Part 3: Highlights from employee surveys

2022/2023 Public Service Employee Survey

The 2022/2023 Public Service Employee Survey (PSES) was administered by Statistics Canada in partnership with Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. It took place from November 21, 2022 to February 5, 2023. This comprehensive survey measures the federal government employees’ opinions about their engagement, leadership, workforce, workplace, workplace well-being and compensation.

A total of 189,584 employees in 90 federal departments and agencies responded to the 2022/2023 PSES, for a response rate of 53%.

The results from the 2022/2023 PSES indicate that more than four in five (81%) public servants like their job, and 78% of employees report having support in balancing their work and personal life. The results show that employees felt more positive regarding their career development than they did in 2020. 79% indicated that they feel that their immediate supervisor supports their career goals, up from 77% in 2020/2021.

Most employees indicated that they believe that their workplace is respectful, and the results relating to many aspects of respect in the workplace were more positive than they were in 2020/2021. 87% of employees indicated that in their work unit, individuals behave in a respectful manner, slightly higher than 2020/2021 (85%).

Overall, results related to harassment and discrimination have improved year over year.

- Harassment numbers have been steadily declining over the years. There was a decrease from 14% in 2019/2020 to 11% in 2020/2021. These levels have remained at 11% in 2022/2023. Discrimination also remained around the 7-8% mark from 2019/2020 to 2022/2023.

- 72% of employees indicated their department or agency works hard to create a workplace that prevents harassment, up from 71% in 2020/2021, and 74% of employees indicated their department or agency works hard to create a workplace that prevents discrimination (73% in 2020/2021).

Most employees (83%) indicated that their immediate supervisor supports their mental health and well-being, up from 79% in 2020/2021, and 83% of employees indicated that they would feel comfortable sharing concerns with their immediate supervisor about their physical health and safety.

For more information, consult the results of the 2022/2023 Public Service Employee Survey.

2023 Student Experience Survey

The Student Experience Survey (SES) is led by the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO) and has been conducted annually since 2017. The SES was developed to:

- inform recruitment and onboarding strategies;

- contribute to improvements to the student orientation process; and

- ensure students have meaningful learning opportunities.

It is important that students are provided with a meaningful work experience, not only to showcase the federal public service as an employer of choice, but also to train and recruit strong candidates who will help shape the future of the public service.

The 2023 SES was conducted from July 31, 2023 to September 15, 2023 and included questions related to different stages of the student work term, such as:

- recruitment

- onboarding and orientation

- work experience

- accommodations

- work environment

- workplace well-being

- employment in the federal public service

- pay

- general information

76 organizations participated in the survey, yielding 5,471 submitted surveys.

For the most part, the positive gains in the SES results that were seen from 2021 to 2022 were maintained in 2023.

Overall, students were positive about the recruitment process:

- 83% of students felt that the application process was clear and easy to understand.

- 65% of students were satisfied with the amount of information they were provided about the job prior to accepting the position, slightly lower than 2022 (67%).

The vast majority of students were positive about their onboarding experience:

- More than nine in ten students were satisfied with the welcome they received from their supervisor (95%) and from their colleagues (94%), unchanged from 2022; and

- 82% of students were satisfied with the overall orientation they received about their organization, slightly lower than 2022 (84%).

As in 2022, there were widespread positive perceptions of the student work experience in 2023:

- 93% of students agreed that overall, they had a positive work experience, similar to 2022 (94%);

- 93% of students felt that they were generally made to feel part of the team, similar to 2022 (94%);

- 84% of students felt that they were given meaningful work, slightly lower than 2022 (86%); and

- 86% of students believed that their job was a good fit with their skills, similar to 2022 (87%).

Similar to 2022, students in 2023 overwhelmingly endorsed a future career in the public service:

- 87% would recommend to other students that they seek a career in the federal public service, similar to 2022 and 2021 (88%);

- 83% of students would seek a career in the federal public service, the same as in 2022 and 2021; and

- 91% of students felt that their current job provided them with valuable skills needed for future employment, slightly lower than 2022 (92%) and the same as 2021 (91%).

Students identified the following factors as most important in choosing their future employment after completing their education: gaining work experience in their field of study; salary; and innovative and exciting opportunities and experiences.

For more information, consult the results of the 2023 Student Experience Survey.