Annual Report on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act 2019 to 2020

The Annual Report on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act provides an overview of the activities respecting disclosures made in federal public sector organizations.

On this page

- Message from the Chief Human Resources Officer

- About this report

- Reported enquiry and disclosure activity

- Investigations, findings and corrective measures

- Federal public sector organizations: education and awareness activities

- Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer: activities that supported ethical workplaces

- Appendix A: Summary of organizational activity related to disclosures under the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act

- Appendix B: Key terms

Message from the Chief Human Resources Officer

It is my pleasure to present the 13th annual report on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act to the President of the Treasury Board of Canada and, in turn, to Parliament. The worldwide COVID-19 pandemic has propelled public servants to the forefront of governments’ response. Global studies by third parties showed improvement in the trust that citizens put in their public service. Canada was no exception. More than ever, the integrity of the public sector is a condition to maintaining the public’s confidence in its institutions.

The Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act contributes to the creation of an environment where public servants feel safe to come forward with their concerns about possible wrongdoing. This report provides transparency on activities related to such disclosure. Data shows a decrease in the number of new disclosures received from the previous reporting period.

This year’s report introduces an analysis of results from the 2019 Public Service Employee Survey that relate to the ethical environment in workplaces. Most respondents indicated they know where to go for help when faced with an ethical dilemma and find their organization does a good job of promoting values and ethics. However, and despite a slight improvement, only half of respondents feel they can initiate a formal recourse process without fear of reprisal. This is an indication that the federal public service must continue to invest efforts in this area.

My Office continued to support federal organizations in their efforts by delivering information sessions to designated senior officers for disclosure and to the National Managers’ Community, in collaboration with the Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada, the Department of Justice Canada and the Canada School of Public Service. In addition, and in alignment with the 2017 recommendations of the Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates, the Treasury Board reinforced the accountability of deputy heads by adopting the new Policy on People Management and the associated revised Directive on Conflict of Interest.

Reporting of wrongdoing is a positive and courageous action. An effective public service depends on the commitment of all to maintain the highest possible standards of honesty, openness and accountability. My Office will continue to take steps to foster an ethical workplace culture that is respectful, safe, healthy, diverse and inclusive.

Original signed by

Nancy Chahwan

Chief Human Resources Officer

Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

About this report

This annual report on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (the Act) covers the period from April 1, 2019, to March 31, 2020. The report contains information on disclosure activities in the federal public sector, which includes departments, agencies and Crown corporations as defined in section 2 of the Act.

Every organization subject to the Act is required to designate a senior officer for internal disclosure responsible for addressing disclosures made under the Act and to establish internal procedures to manage disclosures. Alternatively, organizations that are too small to designate a senior officer or establish their own internal procedures can have disclosures handled directly by the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada (PSIC). This report does not contain information on disclosures or reprisal complaints made to the PSIC or anonymous disclosures.

In addition to summarizing disclosure activities in the federal public sector, this report outlines activities undertaken by the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO) to foster an ethical workplace culture in which public servants feel safe to report wrongdoing and are protected from acts of reprisal.

Reported enquiry and disclosure activity

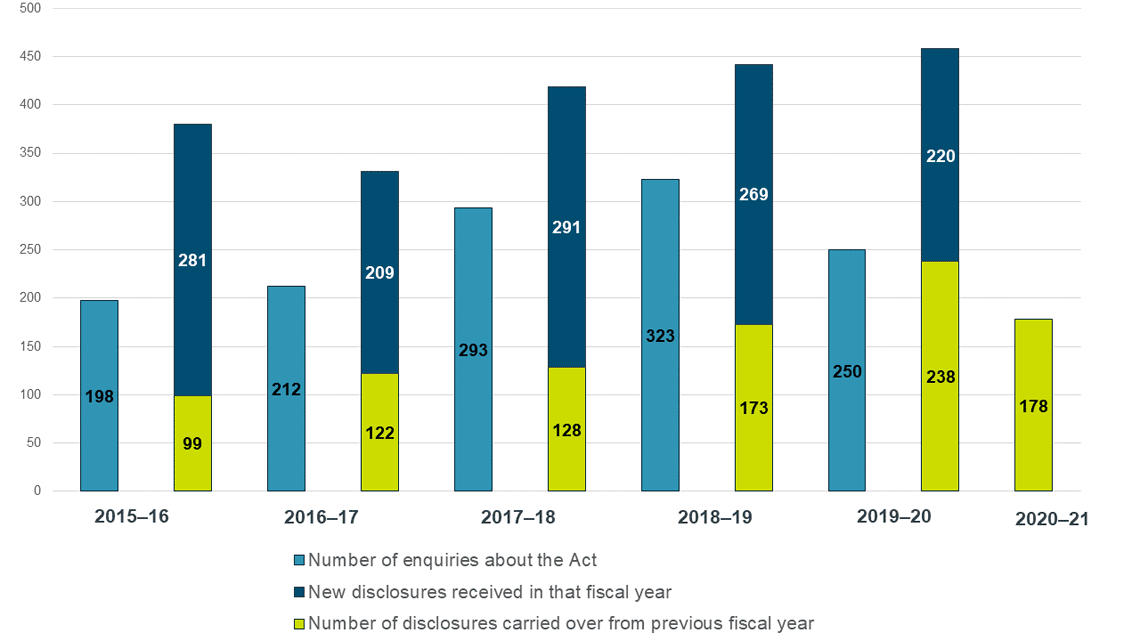

As shown in Figure 1, the number of enquiries about the disclosure process increased in four of the last five years but decreased in 2019–20. Over the last five years, the number of new disclosures has fluctuated between slightly more than 200 and slightly less than 300 per year, with the average being 254. In 2019–20, 220 new disclosures were received by federal public sector organizations, the second-lowest number in five years. For reporting purposes, each allegation made (for example, misuse of public funds, gross mismanagement) is counted as a single disclosure, even when received in a single submission.

From 2015 to 2020, there was an increase in the number of disclosures carried over from one fiscal year to the next. This year, the figure fell despite the rise in volume of active disclosures, with 178 unresolved disclosures being carried over into 2020–21. Federal public sector organizations have indicated that not being able to resolve disclosures in a timely fashion stems from of a lack of internal investigative capacity or available investigative services. To mitigate this issue, a National Master Standing Offer for investigative services has been made available to organizations since 2018.

Since 2016–17, there has also been an increase in the total number of disclosures assessed annually.

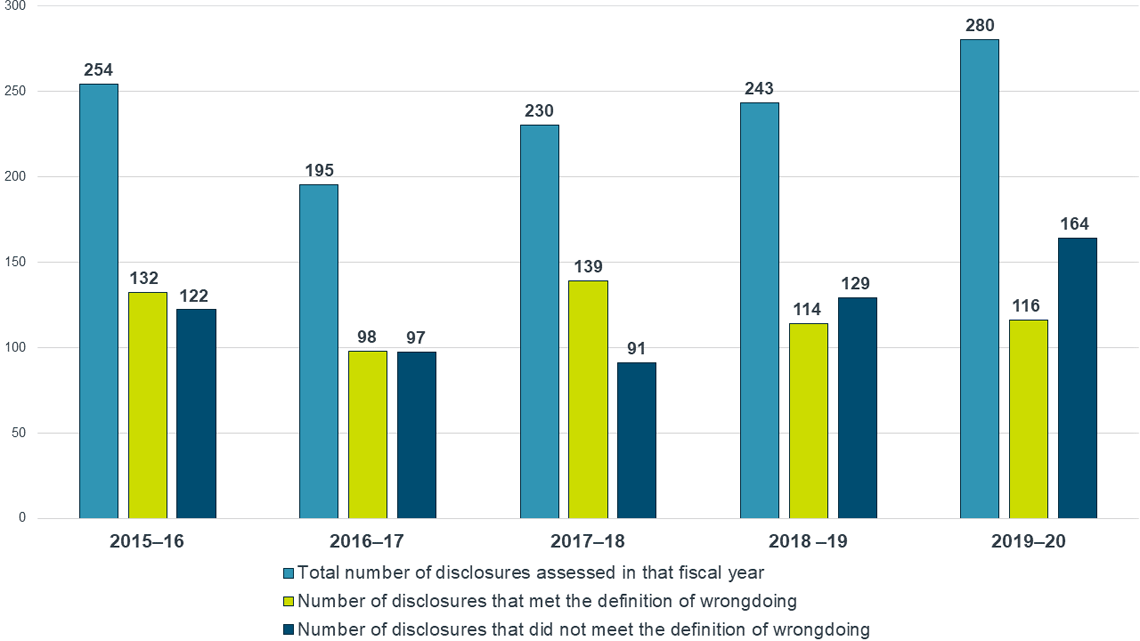

Of the 458 total active disclosures in 2019–20, 61% (280) were assessed this year. In the previous four years, the percentage of disclosures assessed annually fluctuated between 55% (230) in 2017–18 and 67% (254) in 2015–16. Each disclosure is assessed by the relevant senior officer for internal disclosure to determine whether the disclosure made falls within the definition of wrongdoing and warrants further action.

As shown in Figure 2, in 2019–20, 41% (116) of disclosures assessed this year met the definition of wrongdoing.Footnote 1 Over the previous four years, the percentage of disclosures that met the definition of wrongdoing following preliminary analysis has fluctuated annually between 50% (98 in 2016–17) and 60% (139 in 2017–18), with the average being 52% (120).

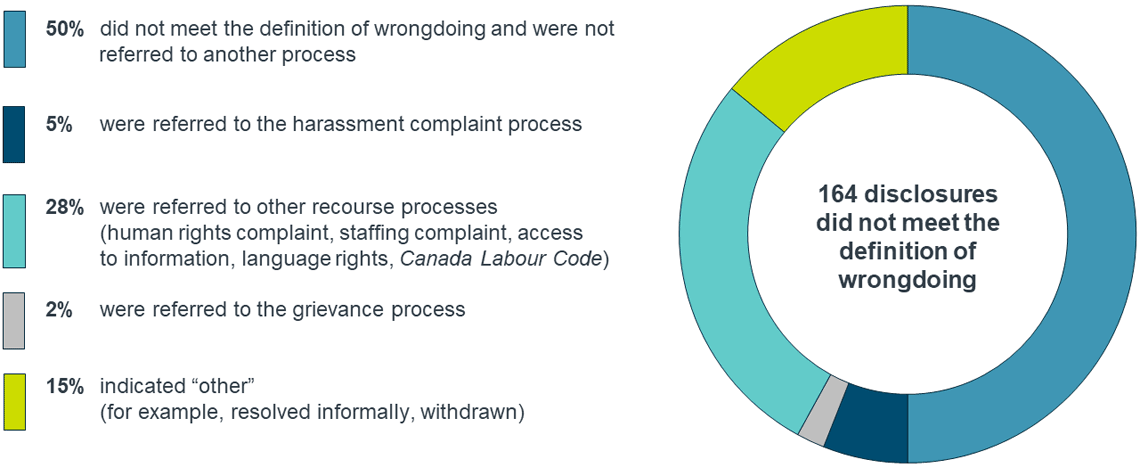

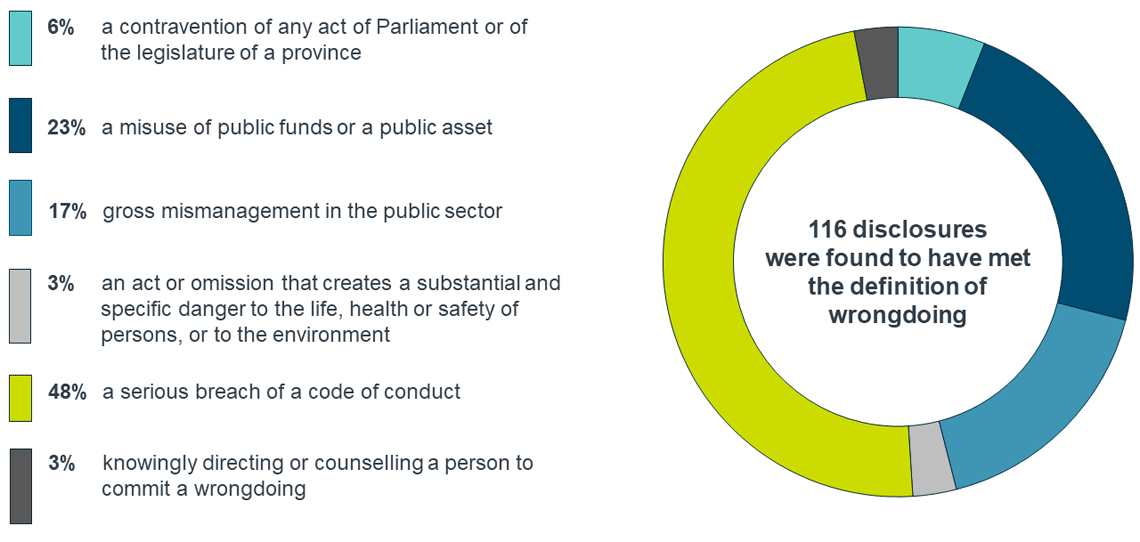

Figures 3 and 4 show the following for 2019–20:

- the breakdown of disclosures that did not meet the definition of wrongdoing

- the breakdown of disclosures that met the definition of wrongdoing

In 2019–20, of the 164 disclosures that did not meet the definition of wrongdoing, 35% (58) were directed to other recourse processes. This situation may indicate a need for federal public sector organizations to develop approaches to more effectively steer public servants to the proper process at the outset.

Compared with last year, fewer disclosures that did not meet the definition of wrongdoing were referred to the harassment complaint process (reduced by 15% to 5%), and a greater number did not meet the definition for “other” reasons (increasing from 3% to 15%).

More than half (51%) of the disclosures over the past two years dealt with a serious breach of a code of conduct. This number may be higher than for other categories because codes of conduct encompass multiple expected behaviours and values. In addition, because codes of conduct provide an explicit standard against which to measure behaviour, this is an area with which public servants may be most familiar and most easily identify perceived breaches.

Investigations, findings and corrective measures

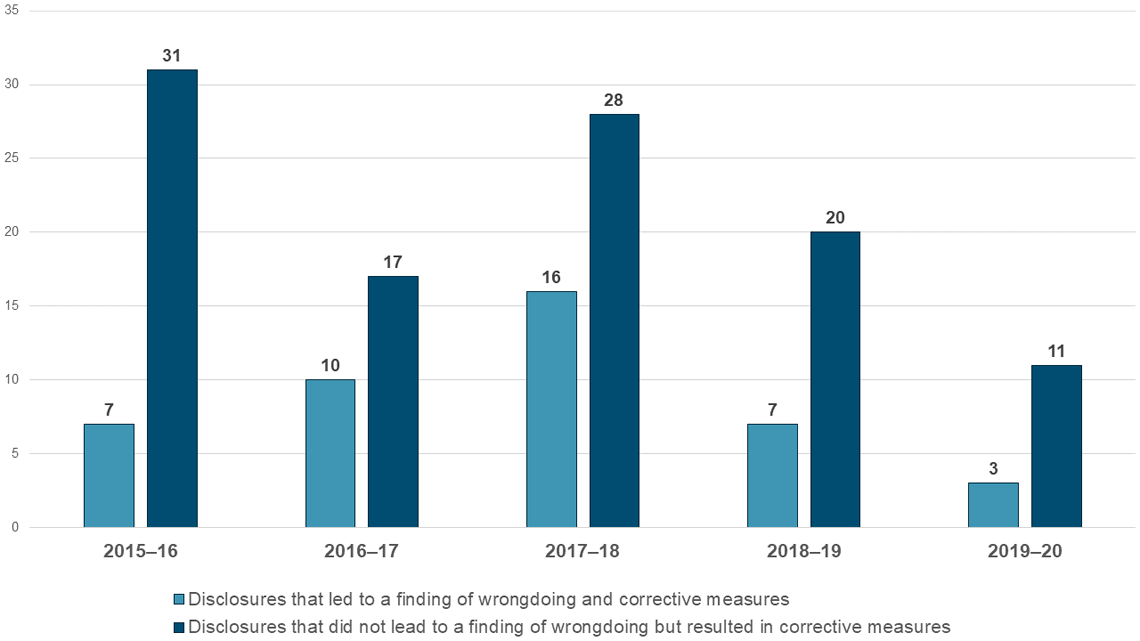

In 2019–20, 38 formal investigationsFootnote 2 were launched. Three were not completed and will be carried over into 2020–21. As a result of preliminary analysis, fact-finding and formal investigations, there were:

- three findings of wrongdoing and corrective measures

- 11 cases where it was determined that there was no wrongdoing but where corrective measures took place; where no wrongdoing is found under the Act, corrective measures (for example, discipline or mandatory training) can still be applied

Figure 5 - Text version

| Type | 2015 to 2016 | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | 2018 to 2019 | 2019 to 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disclosures that led to a finding of wrongdoing and corrective measures | 7 | 10 | 16 | 7 | 3 |

| Disclosures that did not lead to a finding of wrongdoing however resulted in corrective measures | 31 | 17 | 28 | 20 | 11 |

Federal public sector organizations: education and awareness activities

As in previous years, federal public sector organizations took various steps to raise awareness among public servants about the disclosure process and to support those public servants who wish to make a disclosure. Examples include:

- creating and using online guidance, disclosure forms and other tools

- providing organization-specific examples of wrongdoing

- leveraging dedicated email inboxes and toll-free phone lines

- distributing posters and pamphlets placed in common spaces

- setting up kiosks at town hall meetings

Federal public sector organizations also took steps to educate public servants. For example, 99% of federal public sector organizations reported that they provided values and ethics training to staff. In addition, roughly a quarter of organizations reported having developed stand-alone organization-specific training on values and ethics or on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act.

Some specific examples of how organizations are creating awareness of the disclosure process and educating public servants are as follows:

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation operates a dedicated email box and toll-free phone line that are monitored by the organization’s senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing to facilitate questions and disclosures

- Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) published its Internal Disclosure for Reporting Wrongdoing Under the PSDPA: Guidelines for NRCan Managers, Supervisors and Employees on its departmental website

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada provided workshops on fraud, wrongdoing, waste, abuse and mechanisms on how to report such matters under the Act in all regions in Canada

- Global Affairs Canada set up a kiosk during branch-wide town hall meetings that promoted values and ethics and the management of disclosures of wrongdoing

In 2019–20, 20,427 public servants completed the Canada School of the Public Service’s mandatory course “Values and Ethics Foundations for Employees” (C255), and 1,154 managers completed the “Values and Ethics Foundations for Managers” course (C355).

Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer: activities that supported ethical workplaces

In 2019–20, OCHRO provided educational activities for senior officers for disclosure of wrongdoing and managers in order to better equip them to support public servants in their organizations.

OCHRO provided sessions for senior officers for disclosure of wrongdoing in collaboration with:

- the Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner and the Department of Justice Canada to ensure awareness of recent jurisprudence, promising practices and promotional materials to ensure that the disclosure process continues to be accessible

- the Canada School of the Public Service provided training on unconscious bias to senior officers to help them be aware of biases and barriers to staff coming forward

In addition to training for senior officers for disclosure of wrongdoing, training was also provided to the National Managers’ Community to help supervisors understand their responsibilities, as they are often the first point of contact for guidance on the disclosure process.

OCHRO continued to lead government-wide communities of practice this year to share best practices and discuss recent developments in these fields by:

- hosting nine meetings for the Interdepartmental Network on Values and Ethics

- supporting six meetings for the Internal Disclosure Working Group

OCHRO also participated in international organizations, such as the United Nations, the Organization of American States (OAS), and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Being engaged internationally helps keep OCHRO up to date on activities, research and best practices internationally in the areas of integrity, anti-corruption and disclosure regimes. Some of these activities are listed below:

- represented Canada on the OECD’s Working Party of Senior Public Integrity Officials, which developed an Integrity Handbook for member states

- provided advice to the Department of Justice Canada as it represented Canada in the development of the OAS Model Law on Conflict of Interest

- reported on Canada’s promoting of measures to prevent conflicts of interest at the Summit of the Americas Lima Commitment: Democratic Governance Against Corruption

- collaborated with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the Embassy of Canada in Mexico as part of an international initiative to support efforts to establish whistleblower protection legislation across the globe

- exchanged knowledge and experience on Canada’s public service values and ethics with delegations from the Republic of Korea, Mexico, the Republic of Niger, Kazakhstan and Australia

Policy on People Management and Directive on Conflict of Interest

The overall approach to federal public service integrity was strengthened through the new Policy on People Management and the accompanying revised Directive on Conflict of Interest, which both came into effect April 1, 2020.

The new Policy on People Management now requires deputy heads to appoint one or more designated senior officials to prevent and resolve conflict of interest and conflict of duties situations. The directive requires that designated senior official(s) put in place appropriate mechanisms to help public servants identify, report and effectively resolve conflicts of interest.

The directive also complements chief executives’ obligations under the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector to ensure that public servants can obtain appropriate advice within their organization on ethical issues.

Mental health in the workplace

The health and wellness of public servants is vital to each organization’s success. Having the right workplace conditions to support mental health and wellness:

- generates higher levels of employee engagement

- adds to public servants’ confidence coming forward with concerns about wrongdoing

In addition, it is crucial that public servants who make disclosures have access to proper support to help them manage any negative physical, emotional or mental health effects.

OCHRO’s Centre of Expertise on Mental Health in the Workplace supports federal organizations in aligning with the National Standard for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace and advances the Federal Public Service Workplace Mental Health Strategy. Further, the Centre for Wellness, Inclusion and Diversity supports federal organizations in creating safe, healthy, diverse and inclusive workplaces by providing a single window to access system-wide initiatives and resources related to wellness, inclusion, diversity and harassment prevention.

These resources provide part of the foundations of support needed by public servants who wish to disclose potential wrongdoing.

Preventing and resolving harassment and violence in the workplace

The Government of Canada is committed to creating a workplace that is free of harassment and violence where all public servants are treated with dignity, respect and fairness. Research has documented a variety of reprisals that whistleblowers can experience as a result of their disclosures, including negative performance appraisals, exposure to an unmanageable workload and harassment (External Whistleblowers’ Experiences of Workplace Bullying by Superiors and Colleagues).

Employment and Social Development Canada’s Labour Program developed new regulations in 2019–20 in order to better protect federally regulated public servants from harassment and violence in the workplace. These regulations, which will come into effect on January 1, 2021, require all departments and agencies to update their policies and procedures to better prevent, respond to, and provide support to those affected by harassment and workplace violence.

OCHRO, working with bargaining agents, will release a new directive on harassment, aligned with these new regulations, which will replace all current Treasury Board policies and directives on harassment and violence in the workplace. Departments and agencies will receive guidance and tools to assist them in updating their departmental policies and procedures by January 1, 2021.

Public Service Employee Survey: ethics in the workplace

Each year, the Public Service Employee Survey (PSES) allows the public service to gauge what it is doing well and what it could be doing better to ensure the continual improvement of people management practices in government. This includes questions that pertain to the perception of an ethical environment in their workplaces. While the questions are not specific to disclosure of wrongdoing, they provide insights into how public servants are being equipped to address issues such as values and ethics dilemmas, including wrongdoing.

Compared with 2018, the overall 2019 PSES results pertaining to ethics in the workplace were either more positive or unchanged:

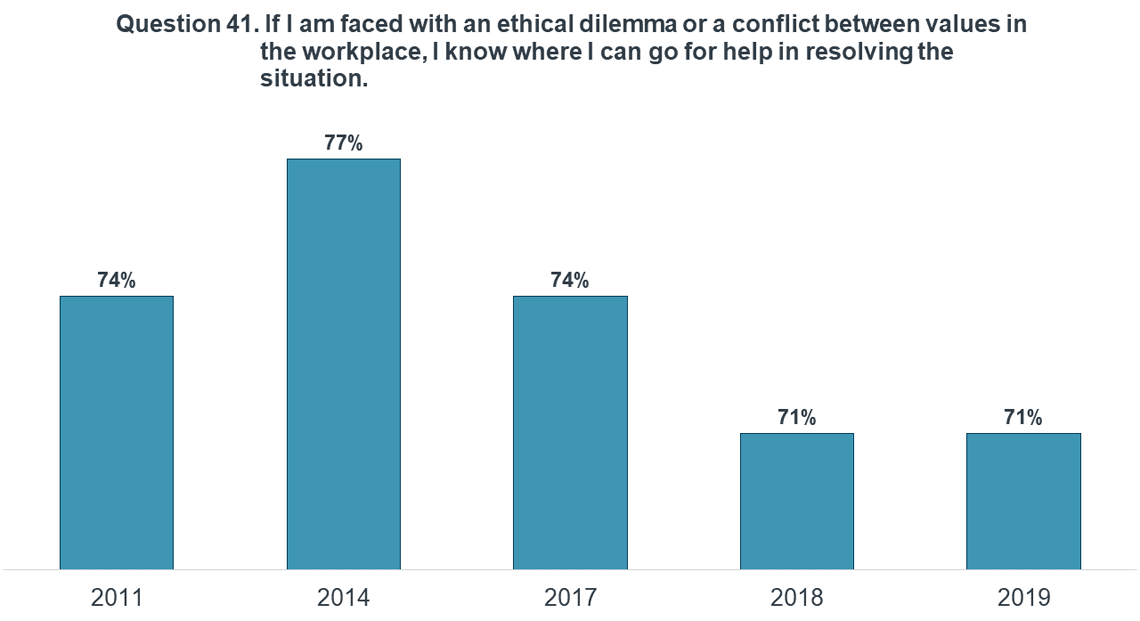

- 71% of public servants indicated that they would know where to go for help in resolving the situation if they were faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace; while this figure is unchanged from 2018 (71%), this indicator has generally tracked downward since it reached a peak of 77% in the 2014 PSES exercise (see Figure 6)

Figure 6 - Text version

| Survey year | Agree |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 74% |

| 2014 | 77% |

| 2017 | 74% |

| 2018 | 71% |

| 2019 | 71% |

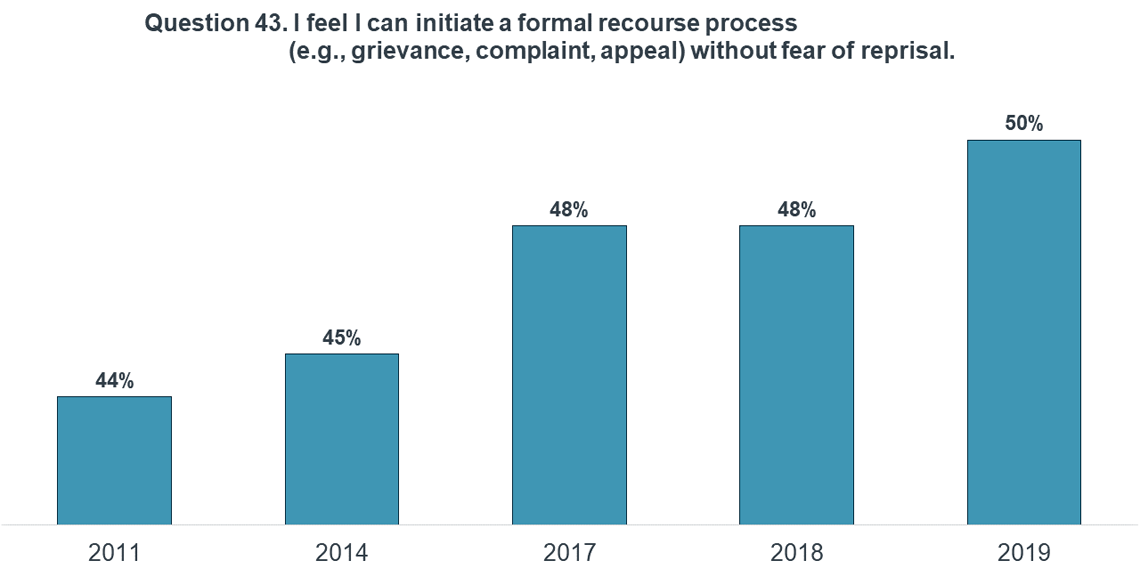

- 50% of public servants indicated they felt they could initiate a formal recourse process (for example, grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal, 2 percentage points higher than in 2018 (48%); this figure has steadily tracked upwards over the course of the last five PSES surveys since 2011 (see Figure 7)

Figure 7 - Text version

| Survey year | Agree |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 44% |

| 2014 | 45% |

| 2017 | 48% |

| 2018 | 48% |

| 2019 | 50% |

- 69% of public servants indicated that they felt that their department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace, the same as 2018 (69%); this question was first introduced to the survey in 2018 and, as such, it is too early to assess its trend

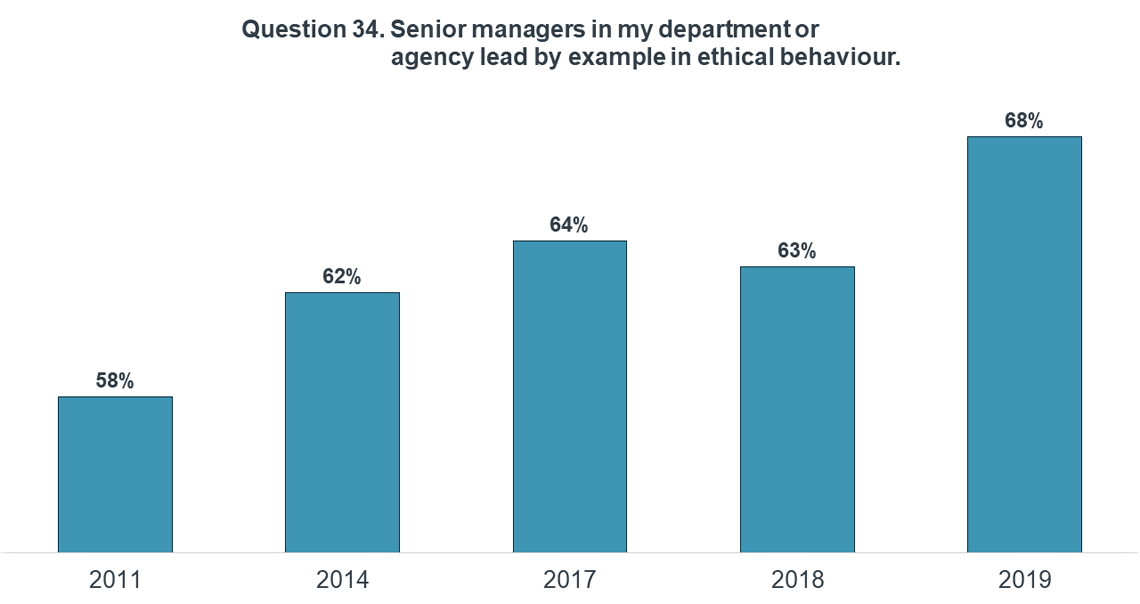

- 68% of public servants responded positively that senior managers in their department or agency lead by example in ethical behaviour; this result reflects a general upward trend over the last five PSES surveys from 58% in 2011 (see Figure 8)

Figure 8 - Text version

| Survey year | Agree |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 58% |

| 2014 | 62% |

| 2017 | 64% |

| 2018 | 63% |

| 2019 | 68% |

Ideally, all four indicators should improve over time. As such, while upward trends in the perception of ethical leadership are important, the downward trend in the rate of awareness about where to go for help in resolving ethical dilemmas or conflicts is a concern. OCHRO will continue to support federal organizations to create workplaces where public servants feel safe and protected to come forward when they have concerns about possible wrongdoing.

For the first time this year, these questions from the 2019 PSES were analyzed by gender, province and territory, employment equity group, employment community, and organizational mandate to gain a better understanding of the federal public service values and ethics landscape. This analysis has provided insights into areas where there are notable differences. For example, when compared with the public service as whole, it was noted that certain groups generally responded less positively to the PSES questions about values and ethics, including:

- persons with disabilities, Indigenous peoples and those who self-identify as gender-diverse

- public servants in British Columbia and Alberta

- public servants in the security community and in security- or military-related organizations

Additionally, specific gaps were also noted. For example, there was a lower positive response rate among the legal services community and public servants working outside of Canada related to not fearing reprisal. The latter also had the lowest levels of positive response about senior managers leading by example in ethical behaviour.

Some groups, such as gender-diverse public servants, Indigenous persons, and persons with disabilities, generally reported through the PSES both higher rates of harassment and discrimination as well as a heightened fear of reprisal, potentially impacting their decisions to pursue formal recourse processes, including in cases of wrongdoing.

Going forward, these insights will inform where and with which communities OCHRO and the chief executives of federal organizations should target outreach and communication resources and activities to further strengthen the environment for both awareness about and disclosure of wrongdoing. More details of this analysis are provided below.

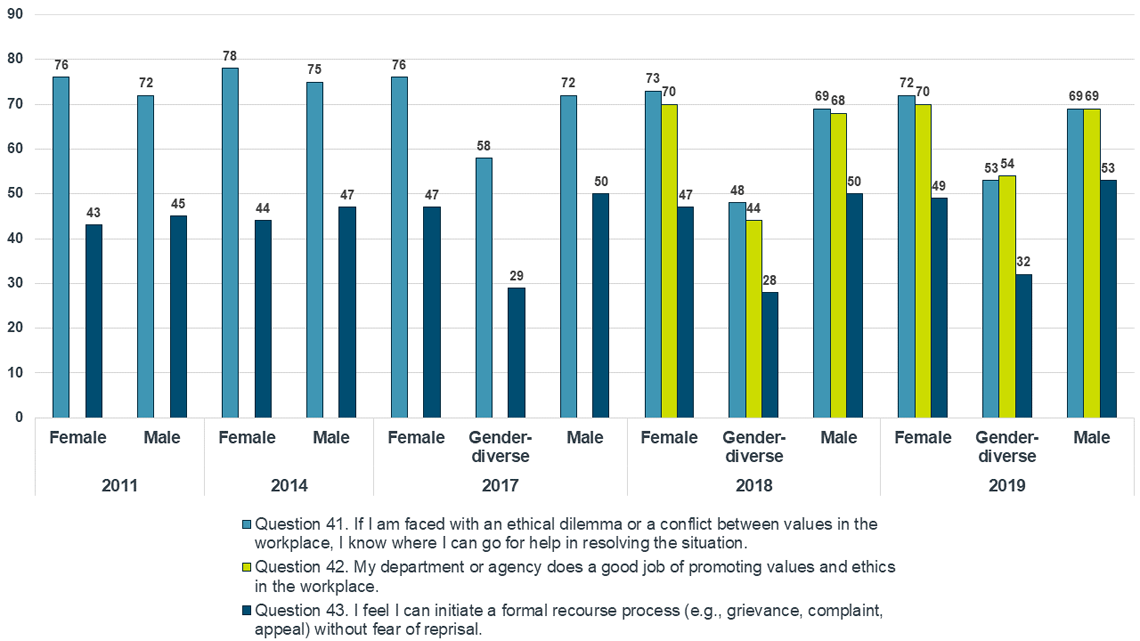

PSES results by gender

As shown in Figure 9, the results on the questions pertaining to ethics for men and women have remained relatively consistent since 2011. Female respondents reported slightly higher rates than males in terms of:

- knowing where to go to resolve an ethical dilemma

- the belief that their organization promotes values and ethics in the workplace

Female respondents, however, have consistently been more positive than their male counterparts, with the exception of their perception of being able to initiate a formal recourse process without fear of reprisal.

Although gender-diverse public servants represented less than 1% of all respondents, the results for this group were much less positive when compared with males and females, including lower levels of agreement that senior managers were leading by example in terms of ethics (49% versus 68% for the public service as a whole). It is notable that gender-diverse public servants have generally reported harassment rates that are double that of males and females, which may be influencing the overall more negative perception of the ethical environment.

Figure 9 - Text version

| Survey year | Gender | Question 41. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation. | Question 42. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace. | Question 43. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (e.g., grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | Female gender | 76% | n/a | 43% |

| Male gender | 72% | n/a | 45% | |

| 2014 | Female gender | 78% | n/a | 44% |

| Male gender | 75% | n/a | 47% | |

| 2017 | Female gender | 76% | n/a | 47% |

| Male gender | 72% | n/a | 50% | |

| Gender diverse | 58% | n/a | 29% | |

| 2018 | Female gender | 73% | 70% | 47% |

| Male gender | 69% | 68% | 50% | |

| Gender diverse | 48% | 44% | 28% | |

| 2019 | Female gender | 72% | 70% | 49% |

| Male gender | 69% | 69% | 53% | |

| Gender diverse | 53% | 54% | 32% |

PSES results by provinces and territories

As shown in Table 1, for all three ethical workplace questions, the results for Alberta and British Columbia were less positive than for other provinces and territories, whereas public servants in the Atlantic provinces tended to be more positive.

Notably, public servants who work outside Canada reported the lowest levels of certainty that they could initiate a formal recourse process without fear of reprisal and the lowest levels of agreement that senior managers were leading by example in terms of ethical behaviour.

| Ethical Workplace Questions by Provinces and Territories (%) – 2019 PSES | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Question 41. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation. | Question 42. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace. | Question 43. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (e.g., grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal. | |

| Alberta | 67 | 64 | 47 |

| British Columbia | 67 | 63 | 47 |

| Manitoba | 72 | 70 | 52 |

| National Capital Region | 72 | 72 | 50 |

| New Brunswick | 75 | 74 | 58 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 77 | 77 | 58 |

| Northwest Territories | 73 | 67 | 52 |

| Nova Scotia | 70 | 67 | 53 |

| Nunavut | 75 | 75 | 60 |

| Ontario (excluding National Capital Region) | 69 | 66 | 49 |

| Outside of Canada | 81 | 73 | 42 |

| Prince Edward Island | 74 | 76 | 56 |

| Quebec (excluding National Capital Region) | 68 | 69 | 53 |

| Saskatchewan | 70 | 68 | 51 |

| Yukon | 69 | 67 | 52 |

| Public Service | 71 | 69 | 50 |

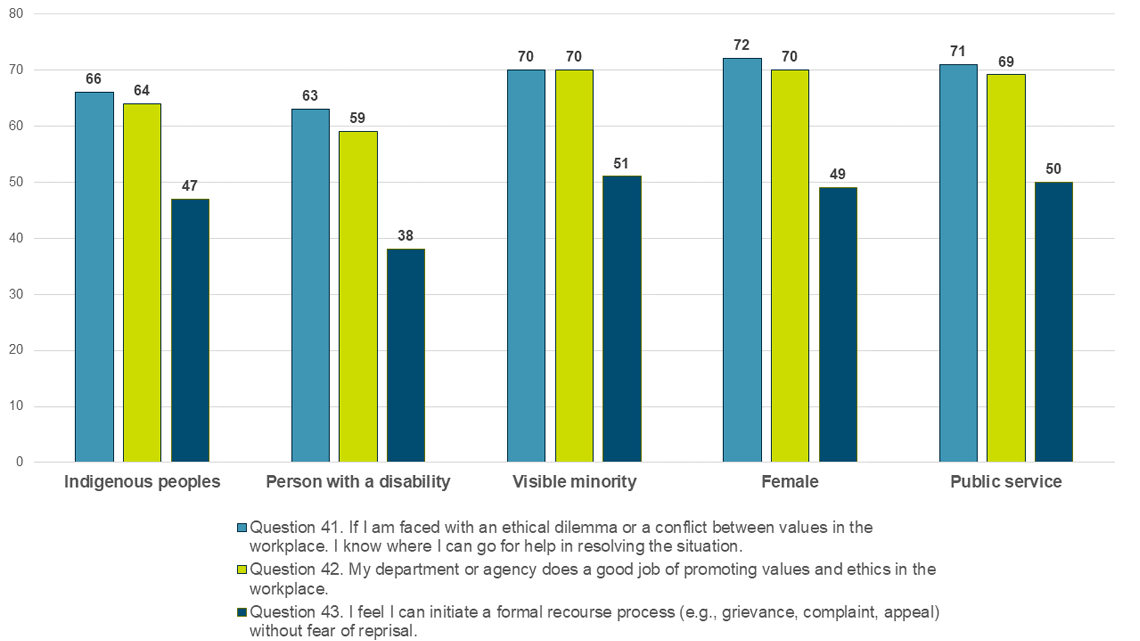

PSES results by employment equity group

As shown in Figure 10, the results for questions about an ethical workplace in 2019 for members of a visible minority and female public servants were generally on par with those for the public service as a whole.

Persons with disabilities were less positive for three questions when compared with the public service, showing negative gaps of between 5 and 12 percentage points. Indigenous peoplesFootnote 3 showed a negative gap of 5 percentage points in terms of knowing where to go to get help to resolve a dilemma and 3 percentage points in terms of not fearing reprisal. Of the four employment equity groups, these two also reported levels of agreement that senior managers were leading by example in terms of ethical behaviour that were lower (56% for persons with disabilities and 64% for Indigenous persons) than the public service average (68%).

Figure 10 - Text version

| Demographic | Question 41. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation. | Question 42. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace. | Question 43. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (e.g., grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous peoples | 66% | 64% | 47% |

| Person with a disability | 63% | 59% | 38% |

| Visible minority | 70% | 70% | 51% |

| Female | 72% | 70% | 49% |

| Public Service | 71% | 69% | 50% |

PSES results by employment community

The 2019 PSES results for ethics in the workplace did not vary significantly across employment communities,Footnote 4 with some notable exceptions. Public servants in the security community were less likely than public servants in the overall public service to agree that:

- they would know where to go if they had an ethical dilemma (55% versus 71% for the public service as a whole)

- their organization promotes values and ethics in the workplace (49% versus 69% for the public service as a whole)

- they could initiate a formal recourse process without fear of reprisal (39% versus 50% for the public service as a whole)

- they felt that senior managers were leading by example in terms of ethical behaviour (45% versus 68% for the public service as a whole)

Similarly, public servants in the legal services community were also less likely to agree that they could initiate a formal recourse process without fear of reprisal (38% versus 50% for the public service as a whole).

Conversely, certain employment communities were more likely to have positive responses to these same questions. For example, higher rates of agreement were noted in:

- the internal audit and human resources communities with regard to knowing where to go if they had an ethical dilemma (79% and 78% versus 71% for the public service as a whole)

- the internal audit community in terms of the success of organizations in promoting values and ethics in the workplace (77% versus 69% for the public service as a whole)

- the client contact centre and information technology communities that they could initiate a formal recourse process without fear of reprisal (56% for both versus 50% for the public service as a whole)

A number of communities, including communications, data science, policy and others, felt that their senior managers were leading by example in terms of ethical behaviour (75% versus 68% for the public service as a whole).

Certain communities, such as human resources, access to information/privacy, procurement and internal audit were more positive across all four questions versus the public service average.

PSES results by organizational mandate

As shown in Table 2, reflecting the results as analyzed by employment communities, public servants in organizations whose key mandate is related to security and militaryFootnote 5 were less positive in their responses for these four questions in comparison with the other mandate groups. This finding aligns with the observations, noted in the section above, about the lower positive response rates for public servants in the security community. Those organizations with a security and military mandate represent a large portion of the public service, with a population of approximately 66,000 public servants, or approximately 30% of the federal public service.Footnote 6

The results for organizations that have a business and economic developmentFootnote 7 mandate were also less positive for three of the PSES ethics questions but had a similar rate of agreement about the “senior managers lead by example” question as the rest of the public service. These organizations represent approximately 12,604 public servants, or approximately 4% of the federal public service.

| Ethical Workplace Questions by Organizational Mandate (%) – 2019 PSES | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Question 41. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation. | Question 42. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace. | Question 43. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (e.g., grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal. | |

| Agents of Parliament | 76 | 77 | 57 |

| Business and Economic Development | 67 | 66 | 47 |

| Central Agency and Government Operations | 73 | 73 | 52 |

| Enforcement and Regulatory | 74 | 74 | 55 |

| Justice, Courts and Tribunals | 73 | 71 | 45 |

| Science-Based | 70 | 71 | 51 |

| Security and Military | 65 | 61 | 47 |

| Social and Culture | 73 | 73 | 51 |

| Public Service | 71 | 69 | 50 |

Appendix A: Summary of organizational activity related to disclosures under the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act

-

In this section

- A.1 Disclosure activity from 2015 to 2020

- A.2 Organizations reporting activity under the Act in the 2019–20 fiscal year

- A.3 Organizations that reported a finding of wrongdoing under the Act in the 2019–20 fiscal year

- A.4 Organizations that reported no disclosure activities in the 2019–20 fiscal year

- A.5 Organizations that do not have a senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing

- A.6 Inactive organizations for the purposes of reporting

Subsection 38.1(1) of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (the Act) requires chief executives to prepare a report on the activities related to disclosures made in their organizations and to submit it to the Chief Human Resources Officer within 60 days after the end of each fiscal year. The statistics in this report are based on those reports. In the sections that follow, statistics from the four previous years are provided. These statistics provide a snapshot of internal disclosure activities under the Act. It is difficult to draw conclusions because of the differences between organizations. Issues, for example, may be dealt with through different processes in different organizations.

Although the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSEC) and Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) are excluded from the Act by virtue of section 52 of the Act, they are required to establish their own procedures for the disclosure of wrongdoing, including for protecting persons who disclose wrongdoing. These procedures must be approved by the Treasury Board as being similar to those set out in the Act. CSIS’s procedures were approved in December 2009, CSEC’s procedures were approved in June 2011, and the CAF’s procedures were approved in April 2012.

A.1 Disclosure activity from 2015 to 2020

| General enquiries | 2019–20 | 2018–19 | 2017–18 | 2016–17 | 2015–16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of general enquiries related to the Act | 250 | 323 | 293 | 212 | 198 |

| Disclosure activity | 2019–20 | 2018–19 | 2017–18 | 2016–17 | 2015–16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of disclosures received under the Act | 216 | 269 | 291 | 209 | 281 |

| Number of referrals resulting from a disclosure made in another public sector organization | 4 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Number of cases carried over on the basis of disclosures made the previous year | 238 | 173 | 128 | 122 | 99 |

| Total number of disclosures handled (disclosures received, referred, carried over) |

458 | 445 | 332 | 385 | 299 |

| Number of disclosures that met the definition of wrongdoingtable A.1 note a | 116 | 114 | 139 | 98 | 132 |

| Number of disclosures that did not meet the definition of wrongdoingtable A.1 note b | 164 | 129 | 91 | 97 | 122 |

| Number of investigations commenced as a result of disclosures received | 38 | 59 | 71 | 61 | 56 |

| Number of disclosures that led to a finding of wrongdoing | 3 | 7 | 16 | 10 | 7 |

| Number of disclosures that led to corrective measures | 11 | 20 | 28 | 17 | 31 |

Table A.1 Notes

|

|||||

| Organizations reporting | 2019–20 | 2018–19 | 2017–18 | 2016–17 | 2015–16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of active organizations | 133 | 134 | 134 | 133 | 134 |

| Number of organizations that reported enquiries | 33 | 35 | 36 | 36 | 29 |

| Number of organizations that reported disclosures | 24 | 29 | 35 | 22 | 31 |

| Number of organizations that reported findings of wrongdoing | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Number of organizations that reported corrective measures | 4 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 |

| Number of organizations that reported finding systemic problems that gave rise to wrongdoing | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Number of organizations that did not disclose information about findings of wrongdoing within 60 days | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

A.2 Organizations reporting activity under the Act in the 2019–20 fiscal year

| Organization | General enquiries | Disclosures | Investigations commenced | Disclosures that led to | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received | Referred | Carried over from the 2018–19 fiscal year |

Acted upon | Not acted upon | Carried over into the 2020–21 fiscal year |

Finding of wrongdoing | Corrective measures | |||

| Atomic Energy of Canada Limited | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 12 | 38 | 0 | 107 | 3 | 70 | 72 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada Energy Regulator | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 14 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada School of Public Service | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Food Inspection Agency | 26 | 18 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 16 | 17 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Correctional Service Canada | 31 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Department of Justice Canada | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada | 17 | 9 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 1 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Export Development Canada | 7 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Farm Credit Canada | 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | 10 | 14 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Global Affairs Canada | 16 | 12 | 0 | 27 | 35 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Health Canada | 9 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Indigenous Services Canada | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada and Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy Canada | 13 | 13 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 13 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| International Development Research Centre | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| National Capital Commission | 5 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| National Defence | 29 | 16 | 3 | 38 | 16 | 2 | 39 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| National Research Council Canada | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Natural Resources Canada | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Office of the Chief Electoral Officer | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Parks Canada | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Parole Board of Canada | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public Service Commission of Canada | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 3 | 26 | 0 | 10 | 14 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Royal Canadian Mint | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 10 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shared Services Canada | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Staff of the Non-Public Funds, Canadian Forces | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Statistics Canada | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Transport Canada | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Veterans Affairs Canada | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| VIA Rail Canada Inc. | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 250 | 216 | 4 | 238 | 116 | 164 | 178 | 38 | 3 | 7 |

A.3 Organizations that reported a finding of wrongdoing under the Act in the 2019–20 fiscal year

| Organization | Finding of wrongdoing | Corrective measures |

|---|---|---|

| National Capital Commission | Serious breach of a code of conduct (paragraph 8(e) of the Act) |

|

| Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) | Serious breach of a code of conduct (paragraph 8 (e) of the Act) |

|

| Global Affairs Canada | (c) a gross mismanagement in the public sector |

|

A.4 Organizations that reported no disclosure activities in the 2019–20 fiscal year

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

- Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency

- Atlantic Pilotage Authority Canada

- Bank of Canada

- Business Development Bank of Canada

- Canada Council for the Arts

- Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation

- Canada Development Investment Corporation

- Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions

- Canada Employment Insurance Commission

- Canada Infrastructure Bank

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

- Canada Post

- Canada Science and Technology Museum

- Canadian Air Transport Security Authority

- Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

- Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety

- Canadian Commercial Corporation

- Canadian Grain Commission

- Canadian Heritage

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- Canadian Museum for Human Rights

- Canadian Museum of History and Canadian War Museum Corporation

- Canadian Museum of Nature

- Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency

- Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission

- Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission

- Canadian Space Agency

- Canadian Transportation Agency

- Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP

- Courts Administration Service

- Defence Construction Canada

- Department of Finance Canada

- Destination Canada

- Energy Supplies Allocation Board

- Farm Products Council of Canada

- Federal Bridge Corporation

- Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario

- Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada

- Freshwater Fish Marketing Corporation

- Great Lakes Pilotage Authority Canada

- Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada

- Impact Assessment Agency of Canada

- Indian Oil and Gas Canada

- Infrastructure Canada

- International Joint Commission (Canadian Section)

- Library and Archives Canada

- Marine Atlantic Inc.

- Military Police Complaints Commission of Canada

- National Arts Centre

- National Gallery of Canada

- Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada

- Northern Pipeline Agency

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada

- Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs Canada

- Office of the Correctional Investigator

- Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada

- Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada

- Office of the Registrar of the Supreme Court of Canada

- Office of the Secretary to the Governor General

- Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada

- Pacific Pilotage Authority Canada

- Patented Medicine Prices Review Board Canada

- Privy Council Office

- Public Prosecution Service of Canada

- Public Safety Canada

- Public Sector Pension Investment Board

- RCMP External Review Committee

- Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada

- Statistical Survey Operations

- The National Battlefields Commission

- Transportation Safety Board of Canada

- Western Economic Diversification Canada

- Windsor-Detroit Bridge Authority

- Women and Gender Equality Canada

A.5 Organizations that do not have a senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing

- Administrative Tribunals Support Service of Canada

- Canada Lands Company Limited

- Canadian Dairy Commission

- Canadian Human Rights Commission

- Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat

- Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21

- Canadian Race Relations Foundation

- Copyright Board Canada

- Financial Consumer Agency of Canada

- Laurentian Pilotage Authority Canada

- Military Grievances External Review Committee

- National Film Board

- Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages

- Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

- Polar Knowledge Canada

- National Security Intelligence Review Committee

- Standards Council of Canada

- Telefilm Canada

A.6 Inactive organizations for the purposes of reporting

- The Jacques-Cartier and Champlain Bridges Inc.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- Veterans’ Land Act, Director

Appendix B: key terms

For the purposes of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (the Act) and this report, “public servant” means every person employed in the public sector. This includes the deputy heads and chief executives of public sector organizations, but it does not include other Governor in Council appointees (for example, judges or board members of Crown corporations) or parliamentarians and their staff.

The Act defines wrongdoing as any of the following actions in, or relating to, the public sector:

- violation of a federal or provincial law or regulation

- misuse of public funds or assets

- gross mismanagement in the public sector

- a serious breach of a code of conduct established under the Act

- an Act or omission that creates a substantial and specific danger to the life, health or safety of Canadians or to the environment

- knowingly directing or counselling a person to commit a wrongdoing

A protected disclosure is a disclosure that is made in good faith by a public servant under any of the following conditions:

- in accordance with the Act, to the public servant’s immediate supervisor or senior officers for disclosure of wrongdoing, or to the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner (PSIC)

- in the course of a parliamentary proceeding

- in the course of a procedure established under any other act of Parliament

- when lawfully required to do so

Furthermore, anyone can provide information about wrongdoing in the public sector to the PSIC.

The Act defines reprisal as any of the following measures taken against a public servant who has made a protected disclosure or who has, in good faith, cooperated in an investigation into a disclosure:

- a disciplinary measure

- demotion of the public servant

- termination of the employment of the public servant

- a measure that adversely affects the employment or working conditions of the public servant

- a threat to do any of those things or to direct a person to do them

Every organization subject to the Act is required to establish internal procedures to manage disclosures made in the organization. Organizations that are too small to establish their own internal procedures can declare an exception under subsection 10(4) of the Act. In organizations that have declared an exception, disclosures related to the Act are handled directly by the PSIC.

The senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing is the person appointed in each organization to receive and deal with disclosures made under the Act. Senior officers have the following key leadership roles for implementing the Act in their organizations:

- providing information, advice and guidance to public servants regarding the organization’s internal disclosure procedures, including the making of disclosures, the conduct of investigations into disclosures, and the handling of disclosures made to supervisors

- receiving and recording disclosures and reviewing them to establish whether there are sufficient grounds for further action under the Act

- managing investigations into disclosures, including determining whether to deal with a disclosure under the Act, initiate an investigation or cease an investigation

- coordinating the handling of a disclosure with the senior officer of another federal public sector organization, if a disclosure or an investigation into a disclosure involves that other organization

- notifying, in writing, the person(s) who made a disclosure of the outcome of any review or investigation into the disclosure and of the status of actions taken on the disclosure, as appropriate

- reporting the findings of investigations, as well as any systemic problems that may give rise to wrongdoing, directly to his or her chief executive, with recommendations for corrective action, if any

Other relevant terms

- allegation of wrongdoing

- The communication of a potential instance of wrongdoing through a disclosure as defined in section 8 of the Act. The allegation must be made in good faith, and the person making it must have reasonable grounds to believe that it is true.

- disclosure

- The provision of information by a public servant to his or her immediate supervisor or to a senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing that includes one or more allegations of possible wrongdoing in the public sector, in accordance with section 12 of the Act.

- disclosure that was acted upon (admissible disclosure)

- A disclosure where action, including preliminary analysis, fact-finding and investigation, was taken to determine whether wrongdoing occurred and where that determination was made during the reporting period.

- disclosure that was not acted upon (inadmissible disclosure)

- A disclosure received for which the designated senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing determined that the definition of wrongdoing under the Act was not met. The disclosure was either referred to another process or required no further action.

- general enquiry

- An enquiry about procedures established under the Act or about possible wrongdoings, not including actual disclosures.

- investigation

- A formal investigation triggered by a disclosure.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the President of the Treasury Board, 2020,

Catalogue No.BT1-18E-PDF, ISSN: 2292-048X