Annual Report on Official Languages 2013 – 2014

ISSN: 1486-9683

Volume 3

Catalogue No. BT23-1/2014E-PDF

Table of Contents

- Message From the President of the Treasury Board

- Introduction

- Implementation of the Official Languages Program

- Methodology

- Implementation of the Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations Re-Application Exercise

- Activities

- Results

- Next Steps

- Communications With and Services to the Public (including social media)

- Language of Work

- Human Resources Management (including equitable participation)

- Governance and Monitoring

- OCHRO Activities and Follow-Up

- Conclusion and Trends

- Appendix A: Sources of Statistical Data

- Appendix B: Definitions

- Appendix C: Federal Institutions Required to Submit an Annual Review in 2013–14

- Appendix D: Statistical Tables

- Endnotes

Message From the President of the Treasury Board

As President of the Treasury Board, I am pleased to table in Parliament this 26th Annual Report on Official Languages for fiscal year 2013–14, in accordance with section 48 of the Official Languages Act.

The Government of Canada provides a wide range of services to Canadians, and citizens depend on a public service that is professional, modern and effective in both official languages. As Canadians adopt new methods of communication, they expect their Government to adapt and provide information and services through the most efficient and effective means available. Moreover, the Canadian public expects the federal Government to have the institutional capacity to achieve this in both official languages. This Government succeeded in proportionately increasing its pool of bilingual employees over the last three years, enabling it to communicate and serve Canadians more effectively in the official language of their choice.

One of the highlights of the past year has been the Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations Re-Application Exercise following the release of the last decennial census data. The exercise involves the review of the language obligations of 10,240 federal offices across the country subject to the Regulations to ensure that Canadians have access to services in their official language of choice where required.

I am pleased with the progress we have made in implementing the official languages policy suite that came into effect in November 2012, which my department continues to support. As President of the Treasury Board, I am proud of the results achieved thus far. This report offers parliamentarians and the Canadian population a description of the way that federal institutions are following through on the Government’s commitments. The efforts and leadership of federal institutions demonstrated in the following pages will help us continue to advance linguistic duality.

Original signed by

The Honourable Tony Clement

President of the Treasury Board

Introduction

The Official Languages Act (the Act) requires the President of the Treasury Board to submit a report to Parliament on the status of official languages programs in the various federal institutions subject to Parts IV, V and VI of the Act.

The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO) supports approximately 200 federal institutions in the core public administration as well as Crown corporations, privatized entities, separate agencies and departmental corporations subject to the Act in fulfilling their linguistic obligations.

Deputy heads hold primary responsibility for human resources management in their organizations. They must ensure that their institutions develop and maintain an organizational culture that is conducive to the use of both official languages and are able to communicate with Canadians and public service employees in both official languages, while maintaining a public service whose composition reflects both official language communities. This 26th Annual Report covers the application of Parts IV, V and VI of the Act for fiscal year 2013–14, with a focus on the results of the Official Languages Program as a whole.

The highlights that follow provide an overview of the implementation of the Official Languages Program in 2013–14.

Implementation of the Official Languages Program

In fiscal year 2013–14, federal institutions continued to work toward implementing the Official Languages Program, which is central to human resources management and services delivered to the Canadian public. Federal institutions are required to submit a review on official languages at least once over a period of three years. This marks the third year of the three-year cycle that started in 2011–12 and coincides with the third year of implementing a coordinated approach to official languages reporting adopted by the OCHRO and Canadian Heritage. Fifty-six organizations Footnote 1 were required to submit a review to the OCHRO on the elements related to the application of Parts IV, V and VI of the Act; 54 out of 56 submitted a review.

Methodology

Institutions reported to the OCHRO on the following elements of the Official Languages Program:

- communications with and services to the public in both official languages;

- language of work;

- human resources management;

- governance; and

- monitoring of the Official Languages Program.

These five elements were mainly assessed through multiple choice questions.

The approach of asking narrative-type questions to facilitate the collection of more detailed information about various elements was also maintained. These elements included the following:

- the presence of institutions on various social media platforms;

- institutions’ official languages capacity; and

- official languages in the context of strategic and operational reviews.

The following sections of the report outline the status of the Official Languages Program within the 54 institutions that submitted a review. The statistical tables in this report reflect data provided by federal institutions.Footnote 2

Implementation of the Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations Re-Application Exercise

In 2013–14, institutions reviewed their application of the Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations (the Regulations), following the release of the language data from the 2011 Census on October 24, 2012, by Statistics Canada.

The Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations Re-Application Exercise (the Regulations Exercise) stems from a regulatory requirement to update the language obligations of federal offices subject to demographic rules every ten years, using the data on first official language spoken from the most recent decennial census. In its Directive on the Implementation of the Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations (the Directive), the Treasury Board has added the requirement to review the obligations of all other offices and service locations subject to significant demand provisions. This Regulations Exercise ensures that bilingual offices are designated as such in regions where there is significant demand for services in the minority language on the basis of thresholds established by the Regulations.

The designation of bilingual offices takes place in three phases:

- In Phase I, federal institutions consider census data on the size and proportion of the official languages minority population served by the office in the census area in which each office is located. Some institutions are also required to consider the number of people that they serve at their offices;

- In Phase II, federal institutions consider census data on the size and proportion of the official language minority population found in the broader area served by each affected office; and

- In Phase III, federal institutions gather data on the language preferences of the public that they serve in a specific location.

The first phase of the Regulations Exercise, which involved a systematic review of the language obligations of 10,240 federal offices subject to the Regulations, was completed in January 2014.

Activities

Throughout the year, the OCHRO provided support to institutions in their efforts to apply the Directive. Specifically,

- nine training sessions for institutions required to take measures as a result of the census data were offered; Footnote 3

- an online tool to help institutions conduct the Regulations Exercise was provided; and

- the results of Phase I were shared with the Fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne du Canada, the Quebec Community Groups Network and the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages in February 2014.

Results

The first phase allowed the OCHRO to review 77 per cent of the targeted offices, including all of the Canada Post offices, and determine their linguistic obligations for communications with and services to the public. The resulting language obligations for these offices have been posted on Burolis, a federal government inventory of the offices of institutions that are subject to the Regulations, which allows Canadians to identify offices that offer services in their official language.

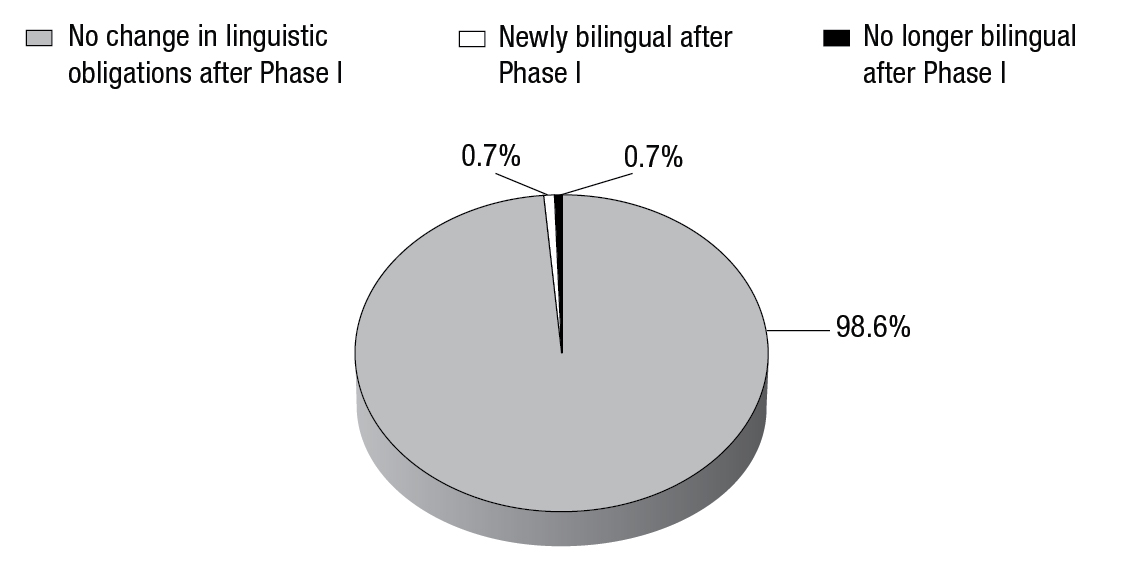

As of , the linguistic designation remains the same for 7,789 offices, or 98.6 per cent of the total number reviewed. Of these, 1,901 offices continue to be designated bilingual in terms of communications with and services to the public, while 5,888 offices continue to provide communications and services in only one official language.

However, 54 offices representing 0.7 per cent of the total number reviewed are newly designated bilingual, while 54 others, or 0.7 per cent, will no longer be required to offer services in both official languages. The majority of these 108 offices are Canada Post service locations, spread across the country.

Figure 1 - Text version

98.6% of the federal offices have no change in linguistic obligations after Phase I; 0.7% of the offices are newly bilingual after Phase I; and, for 0.7% of the offices, bilingualism is no longer required after Phase I of the Regulations Exercise.

In Quebec, 17 offices will be newly designated bilingual, and 15 other offices will be newly designated unilingual—the majority of these again being Canada Post service locations.

About 2,000 other federal offices are automatically designated bilingual because of their mandate or by being directly subject to section 22 or section 24 of the Act, and were not implicated in the Regulations Exercise.

Next Steps

Offices with new linguistic obligations have a maximum of one year, until January 10, 2015, to implement the necessary measures to offer bilingual services. In the case of offices that no longer have to provide bilingual services, the Directive requires that consultations take place with the linguistic minority on the terms and expected date of the discontinuation of bilingual services, and on the location of offices where services are available in the official language of the linguistic minority. The Directive grants institutions a maximum period of two years to conclude these consultations. The offices in question must continue to provide bilingual services until the consultations take place.

Institutions have carried out Phase II of the Regulations Exercise, which affects about 1,500 offices in 48 institutions; the results will be known in 2014–15. Some offices that provide services to a restricted and identifiable clientele or that are subject to specific circumstances under the Regulations, such as those related to the travelling public, have also begun Phase III of the Regulations Exercise, which may continue until the middle of fiscal year 2016–17.

Communications With and Services to the Public (including social media)

As of , there were 11,469 federal offices and service locations, of which 3,931 (34.3 per cent) were required to offer bilingual services to the public.Footnote 4

Based on the 2013–14 annual reviews, a strong majority of the institutions indicated that in offices designated bilingual for communications with and services to the public, oral and written communications are in the official language of the public’s choice. Almost all of these institutions ensure that these offices produce all communications materials in both official languages and publish both language versions simultaneously in full. All of the institutions surveyed stated that, nearly always or very often, the English and French versions of their website content are simultaneously posted in full and are of equal quality.

Canadians are quickly adopting social media as a new method of communication, and federal institutions are following suit using Web 2.0 tools to communicate with the public. Of the 54 institutions subject to the Act that submitted a review in 2013–14, 40 indicated that they use social media: 29 institutions post tweets on Twitter, 20 maintain a Facebook page, 19 post videos on YouTube, 8 have a LinkedIn profile, 6 share pictures on Flickr, 6 contribute to a blog and 4 share interests on Pinterest. Most of these institutions stated that they maintain two pages on social media, one in English and the other in French. They indicated that they ensure the information posted under separate accounts is of equal quality and is posted simultaneously. Institutions that have only one account stated that they ensure it is bilingual by posting information simultaneously in both official languages. While the use of social media is increasing, federal institutions continue to use traditional means of communication and continue to meet their linguistic obligations when doing so.

Federal institutions take various measures to ensure the active offer of communications and services to the public in both official languages in bilingual offices. In the Policy on Official Languages, "active offer" is defined as "to clearly indicate visually and verbally that members of the public can communicate with and obtain services from a designated office in either English or French." Almost all institutions stated that signs identifying their offices are nearly always in both official languages.

Institutions were less inclined to say that they take appropriate measures to greet the public in person in both official languages. They acknowledge that they must continue their efforts to improve their results. Institutions stated that they are more effective in telephone interactions with the public; the vast majority of them nearly always or very often answer calls in both official languages. Almost all institutions stated that their recorded messages are nearly always or very often bilingual.

A majority of institutions indicated that contracts or agreements signed with third parties acting on behalf of offices designated bilingual include clauses setting out their linguistic obligations. A smaller number of institutions ensure that measures are taken to verify that these clauses are respected. Nine institutions stated that they had not signed any contracts or agreements with third parties to act on their behalf. Throughout the fiscal year covered by the reviews, the OCHRO noted that a number of institutions had questions about the services supplied by third parties and provided support to these institutions.

Finally, almost all institutions claimed to nearly always or very often select and use media that reach the targeted public in the most efficient way possible. In their analyses, institutions made extensive reference to their websites, social media accounts and press releases, in addition to the purchase of advertising space or time.

Language of Work

In regions designated bilingual for language of work purposes under the Act, 43 of the 54 institutions examined in 2013–14 stated in their reviews that senior management communicates effectively in both official languages with their employees. A higher number of institutions (i.e., 46) stated that senior management encourages employees to use their preferred official language in the workplace.

Two thirds of the institutions maintained that incumbents of bilingual or either/or positions are nearly always supervised in their preferred official language, regardless of whether the supervisors are located in bilingual or unilingual regions. One third of the institutions indicated that this is very often the case for incumbents.

Forty-three institutions stated that managers and supervisors who occupy bilingual positions in bilingual regions nearly always or very often supervise employees in their employees’ official language of choice, regardless of the linguistic designation of the employees’ positions. Of the language-of-work elements examined in the reviews, the results for supervision remain among the lowest.

A strong majority of institutions maintained that personal and central services are nearly always provided to employees located in bilingual regions in the official language of their choice. A majority of institutions stated that employees obtain training and professional development in the official language of their choice in over 70 per cent of cases.

The findings from the reviews are mixed regarding meetings held in both official languages: the majority of institutions stated that meetings are nearly always conducted in both official languages and that employees are able to use the official language of their choice. For a little over a third of the institutions, this is very often the case.

In a strong majority of institutions, documentation, regularly and widely used work instruments, and electronic systems are available in employees’ preferred official language. A majority of institutions reported that employees can nearly always write documents in the official language of their choice.

Forty-four institutions that have websites intended for employees indicated that the English and French versions were simultaneously posted in full, and that both versions were of equal quality in over 70 per cent of cases.

A strong majority of institutions stated that in unilingual regions, regularly and widely used work instruments are almost always available in both official languages for employees who are responsible for providing bilingual services to the public or to employees in designated bilingual regions. However, 14 institutions indicated that this question does not apply to them.Footnote 5

Human Resources Management (including equitable participation)

As of , Anglophones represented 73.4 per cent of employees in federal institutions subject to the Act; Francophones represented 26.5 per cent of employees. In the core public administration, Anglophones represented 68.1 per cent of employees, Francophones 31.9 per cent. The 2011 Census data indicate that English is the first official language for 75 per cent of Canada’s population, and French for 23.2 per cent. Based on a comparison between workforce data and the most recent data from the 2011 Census, employees from both official language communities are well represented across federal institutions subject to the Act. The participation rate of the two language groups has remained relatively stable over the past three years, even though the number of civil servants has dropped.

All 54 institutions that submitted a review in 2013–14 stated that, overall, they nearly always and very often have the necessary resources to fulfill their language obligations related to services to the public and language of work. Almost as many institutions stated that they nearly always or very often put in place administrative measures to ensure that the bilingual requirements of a function are met in order to offer services to the public and to employees in the official language of their choice, when required by Treasury Board policies.

Almost all of the institutions stated that the language requirements of bilingual positions are nearly always and very often established objectively. Four institutions indicated that the question did not apply to them. Their linguistic profiles reflect the duties of employees or their work units as well as the obligations with respect to services to the public and language of work. For three quarters of the 54 institutions that have bilingual positions, these positions are nearly always filled by candidates who were bilingual at the time of appointment. For nearly one quarter of the institutions that submitted a review, this is very often the case.

About half of the institutions nearly always grant language training to employees for career advancement; this is often or very often the case for a third of the institutions. Thirty-seven institutions stated that they nearly always or very often provide working conditions conducive to the use and improvement of second language skills so that employees who return from language training are able to maintain their skills.

Governance and Monitoring

Three years of a coordinated approach to reporting on official languages with Canadian Heritage and the 2012 inclusion of governance requirements in the new official languages policy suite are having an impact on official languages governance in federal institutions, fostering collaboration between Official Languages Champions and those responsible for different parts of the Act, and encouraging institutions to review their official languages governance.

A large majority of the institutions examined in 2013–14 indicated that they have developed a distinct official languages action plan or have integrated precise and complete objectives in another planning instrument in order to ensure compliance with their language obligations. In addition, a majority of institutions indicated that language obligations are regularly or sometimes on the agenda of senior management committees.

The champion or co-champion and the persons responsible for Parts IV, V, VI and VII of the Act meet regularly to discuss the official languages file in a majority of the institutions. Twelve institutions responded that they hold no meetings of this kind. For several small institutions, the champion and the person responsible for official languages are one and the same.

More than half of the institutions that have introduced performance agreements have included performance objectives for implementing various parts of the Act. Some respondents, such as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and Air Canada, indicated that these performance objectives are for the champions or persons responsible for official languages. Others indicated that a performance objective may be mandatory for an employee who demonstrates shortcomings in the language skills required for his or her position. Finally, some institutions have developed a generic performance objective for senior managers to promote the use of both official languages in the workplace.Footnote 6

More than half of the institutions have established an official languages committee, network or working group made up of representatives from the different sectors or regional offices to deal horizontally with questions related to language obligations. Many small institutions have no such bodies.

Of the 54 institutions that submitted a review, 50 stated that they regularly take measures to ensure that employees are well aware of the obligations related to various parts of the Act. A large majority of the institutions that have taken such measures stated that mechanisms are in place to ensure that they regularly monitor the implementation of the different parts of the Act and inform the deputy head of the results.Footnote 7 The majority of institutions (i.e., 78 per cent) conducted activities during the fiscal year to measure the availability and quality of services offered to the public in both official languages.Footnote 8 Institutions also carry out activities to periodically measure whether, in regions designated bilingual for language-of-work purposes, employees can use the official language of their choice in the workplace. The Public Service Employee Survey was the main measuring tool that institutions mentioned, although some stated that they conducted their own internal surveyFootnote 9 in the fiscal year under review. Almost all of the institutions that submitted a review stated that they take measures to improve or rectify shortcomings or deficiencies revealed by their monitoring activities or mechanisms. Two thirds of the institutions stated that they have put mechanisms in place to determine and document the impact of their decisions on the implementation of the Act, such as decisions to adopt or revise a policy, create or abolish a program, or establish or eliminate a service location. Out of the 54 institutions, 13 stated that they do not have such mechanisms, and five specified that this question did not apply to them.

The main tool that institutions mentioned to document the impact of their decisions was the Official Languages Impact Analysis template included in Treasury Board submissions. In reviewing A Guide to Preparing Treasury Board Submissions, the OCHRO modified its criteria in consultation with Canadian Heritage to take into account, among other things, the impact on the participation of English- and French-speaking Canadians in federal institutions.Footnote 10 Institutions had until , to fully implement the updated guide.

A majority of institutions said that audit or evaluation activities are undertaken either by internal audit or by other units to evaluate to what extent official language requirements are implemented. When monitoring activities or mechanisms reveal shortcomings or deficiencies, most institutions maintained that steps are taken and documented to improve or rectify the situation with due diligence.

OCHRO Activities and Follow-Up

At the start of 2013–14, the OCHRO received the final report on the Evaluation of the Official Languages Centre of Excellence Initiative, which assessed the relevance and performance of the initiative from 2008 to 2012 and met the reporting requirements of the horizontal evaluation of the Roadmap for Canada’s Linguistic Duality 2008-2013: Acting for the Future. The OCHRO accepted the recommendations of the Internal Audit and Evaluation Bureau and worked toward their implementation. This work also engaged the official languages community.

The OCHRO continued to provide horizontal support to federal institutions on key issues of mutual interest, including some of the challenges identified in the reviews. To help institutions improve their outcomes in certain areas, the OCHRO worked with them through

- Clearspace, an external online platform (e.g., information sharing, discussions);

- activities of departmental and Crown corporation advisory committees on official languages (e.g., workshops, case studies, discussions); and

- Official Languages Champions (e.g., annual conference).

The topics addressed through these means were the Regulations Exercise, identification of language requirements and the bilingual bonus, bilingual meetings, translation of drafts, bilingual signature blocks, social media and Web 2.0, supervision, federal office moves and performance management.

In 2013–14, the OCHRO also modernized an aspect of its collection of statistical data on resources. The Official Languages Information System II tables, whose purpose is to meet the Treasury Board’s data needs on the status of the Official Languages Program in institutions not part of the core public administration, were modernized through the adoption of a more user-friendly template to make the compilation of statistical data more effective.

The OCHRO was consulted during the development of the Standard on Social Media Account Management, which came into effect on . The standard clarifies the Treasury Board’s expectations of institutions and reiterates the requirements of the Directive on Official Languages for Communications and Services.

The OCHRO supported various activities and initiatives led by the Council of the Network of Official Languages Champions (the Council) and the community of Official Languages Champions to help these champions support deputy heads in implementing their official languages obligations and in promoting official languages in their institutions:

- In anticipation of the , coming into force of the Directive on Performance Management, the OCHRO supported the Council by helping to organize an information session for Official Languages Champions in March 2014. It contributed to the vision exercise Blueprint 2020: Building Tomorrow’s Public Service Together, launched by the Clerk of the Privy Council, by participating in a working group established by the Council.

- During 2013–14, a working group established by the Council and supported by the OCHRO developed a checklist to help Official Languages Champions support deputy heads in fulfilling their official languages obligations in their institutions, especially with respect to governance. The checklist was launched on the occasion of the fifth Linguistic Duality Day in the federal public service, held on . The Council also established a working group on the Public Service Employee Survey, which the OCHRO supports and advises within the framework of its official languages and survey responsibilities. This working group proposed that questions be added to the survey in order to obtain detailed information on certain official languages issues.

Departmental and Crown corporation advisory committees, made up of persons responsible for official languages and chaired by the OCHRO, were also active in 2013–14:

- A working group on language training and maintenance was established to discuss two recommendations from a study by the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages about language training, monitoring measures that might be necessary, and skills maintenance for public servants who have met the linguistic requirements of their positions.

- Since the active offer of services in both official languages has been identified as a recurring shortcoming in the annual reviews, a working group was established to discuss possible approaches to improve results. This working group will continue its work over 2014–15.

In January 2014, the OCHRO published Bilingual Bonus – Support Document. This document, which is intended for managers, was developed from the collection of questions asked by institutions over the years. In addition, the OCHRO promoted sharing good practices by helping to organize the Best Practices Forum, where 230 persons participated in December 2013.

The OCHRO’s activities, as well as discussions and exchanges within the official languages community through the platform Clearspace, enabled the sharing of good practices and contributed to improved results and a better understanding of official languages obligations. This platform makes it possible to reach the community of persons responsible for official languages, quickly and effectively.

Conclusion and Trends

2013–14 is the third year in the three-year cycle of annual reviews on official languages. Institutions subject to the Act seem determined to implement all the requirements of the Act, the Regulations and the Policy on Official Languages. Most institutions have put in place an official languages governance structure and are quick to deal with shortcomings. Nonetheless, there continue to be challenges, and deputy heads must remain vigilant and rigorous in measuring performance and monitoring compliance.

The OCHRO will support institutions throughout the Regulations Exercise as it continues, at a time when the means of delivering service to the public are undergoing considerable change.

Websites, social media and toll-free telephone lines are overtaking face-to-face services and are preferred by Canadian businesses and citizens in dealing with their Government. As service delivery changes, deputy heads will need to demonstrate leadership to ensure their institutions have a competent workforce that offers quality services to the public in both official languages. This also applies to personal and central services for public servants and, in regions designated bilingual for language-of-work purposes, to managers and supervisors who supervise employees from both linguistic groups.

The results of the 2014 Public Service Employee Survey will provide vital, up-to-date information on institutions’ capacity to successfully establish a workplace that is conducive to the effective use of both official languages.

In 2013, the Clerk of the Privy Council and Head of the Public Service of Canada launched Blueprint 2020, a consultation process that aims to build the public service of tomorrow. The discussion paper envisions improved access to government information and services in both official languages through close collaboration with other levels of government, partners and end-users in designing and delivering public programs. The exchanges on official languages that took place during the consultation process led to an action plan proposal by the Council of the Network of Official Languages Champions in February 2014. Elements of the Council’s Vision 2017 strategic plan were retained in the Blueprint 2020 progress report.

The engagement of public servants in defining the Blueprint 2020 vision in concrete terms should continue. This is one more opportunity to incorporate linguistic duality in the definition of what the federal public service will be in the future. The OCHRO continues to encourage institutions—and public servants—to participate in building the public service of tomorrow by affirming the importance of our two official languages at every opportunity.

Appendix A: Sources of Statistical Data

There are three main sources of statistical data:

- Burolis is the official inventory of offices and service locations that indicates whether they have an obligation to communicate with the public in both official languages;

- The Position and Classification Information System (PCIS) covers the positions and employees in institutions that are part of the core public administration; and

- The Official Languages Information System II (OLIS II) provides information on the resources held by institutions that are not part of the core public administration (i.e., Crown corporations and separate agencies).

The reference year for the data in the tables varies depending on the system: , for the Position and Classification Information System and Burolis; , for OLIS II.

Although the reference years may be different, the data used for reporting are based on the same fiscal year. To simplify the presentation of the tables and make comparison easier, the two data systems use the same fiscal year.

For the three institutions that did not provide any information (Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services [formerly Non-Public Funds, Canadian Forces]; Fredericton International Airport Authority Inc.; and St. John’s International Airport Authority), the statistical tables reflect data provided by these institutions for the previous year.

Notes

Percentages in the tables may not add up to 100 per cent due to rounding to the closest decimal point.

The data in this report that pertain to positions in the core public administration are compiled from the Position and Classification Information System and differ slightly from the data in the Incumbent Data System.

Pursuant to the Public Service Official Languages Exclusion Approval Order, incumbents who do not meet the language requirements of their position would fall into one of two categories:

- They are exempt; or

- They have two years to meet the language requirements.

The linguistic profile of a bilingual position is determined using three levels of second language proficiency:

- Level A: Minimum proficiency;

- Level B: Intermediate proficiency; and

- Level C: Superior proficiency.

Appendix B: Definitions

The term "position" refers to a position filled for an indeterminate period or a determinate period of three months or more, according to the information available in the Position and Classification Information System.

"Resources" refers to the resources required to meet obligations on a regular basis, according to the information available in Official Languages Information System II.

"Bilingual position" is a position in which all or part of the duties must be performed in both English and French.

"Reversible" or "either/or position" is a position in which all the duties can be performed in English or French, depending on the employee’s preference.

"Incomplete record" means a position for which data on language requirements is incorrect or missing.

"Linguistic capacity outside Canada" refers to all rotational positions outside Canada (i.e., rotational employees)—most of which are in Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada—that are staffed from a pool of employees with similar skills.

In Tables 5, 7, 9 and 11, the levels of second language proficiency required refer only to oral interaction (i.e., understanding and speaking). The "Other" category refers to positions either requiring specialized proficiency (i.e., code P) or not requiring any second language oral interaction skills.

The terms "Anglophone" and "Francophone" refer to employees on the basis of their first official language. The first official language is the language declared by the employee as the one with which he or she has a primary personal identification.

Appendix C: Federal Institutions Required to Submit an Annual Review in 2013–14

Fifty-four federal institutions submitted an annual review in 2013–14:

- Air Canada

- Atlantic Pilotage Authority Canada

- Canada Border Services AgencyFootnote 11

- Canada Post

- Canada Revenue Agency

- Canada Science and Technology Museum

- Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

- Canadian Commercial Corporation

- Canadian Dairy Commission

- Canadian Forces Morale and Welfare Services

- Canadian HeritageFootnote 11

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat

- Canadian Museum of History (Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation)Footnote 11

- Canadian Museum of Nature

- Canadian National Railway Company

- Canadian Polar Commission

- Citizenship and Immigration Canada

- Communications Security Establishment Canada

- Correctional Service CanadaFootnote 11

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- Federal Bridge Corporation

- Financial Consumer Agency of Canada

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada

- Health Canada

- Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada

- Indian Oil and Gas Canada

- Industry Canada

- International Development Research Centre

- Laurentian Pilotage Authority CanadaFootnote 11

- Marine Atlantic Inc.

- Military Police Complaints Commission of Canada

- Nanaimo Port Authority

- National Defence

- Natural Resources Canada

- Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada

- Office of the Secretary to the Governor General

- Pacific Pilotage Authority Canada

- Patented Medicine Prices Review Board Canada

- Public Works and Government Services Canada

- Quebec Port Authority

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- Saguenay Port AuthorityFootnote 11

- Security Intelligence Review Committee

- Shared Services Canada

- Standards Council of Canada

- The Jacques-Cartier and Champlain Bridges Inc.

- The National Battlefields Commission

- The Seaway International Bridge Corporation Ltd.

- Transport Canada

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

- VIA Rail Canada Inc.

- Windsor Port Authority

Two federal institutions did not submit an annual review for 2013–14:

- Farm Products Council of Canada

- Saint John Port Authority

Appendix D: Statistical Tables

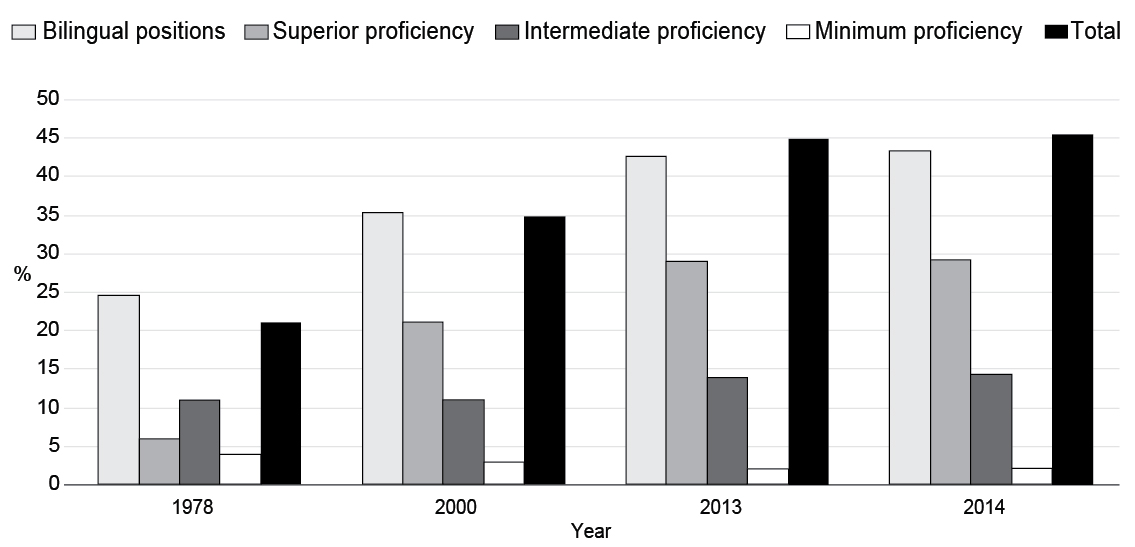

Figure 2 - Text version

| Year | Bilingual positions % | Superior proficiency % | Intermediate proficiency % | Minimum proficiency % | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | 25% | 6% | 11% | 4% | 21% |

| 2000 | 33% | 21% | 11% | 3% | 35% |

| 2013 | 43% | 29% | 14% | 2% | 45% |

| 2014 | 43% | 29% | 14% | 2% | 46% |

| Year | Bilingual | English Essential | French Essential | English or French Essential | Incomplete Records | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | 52,300 | 24.7% | 128,196 | 60.5% | 17,260 | 8.1% | 14,129 | 6.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 211,885 |

| 2000 | 50,535 | 35.3% | 75,552 | 52.8% | 8,355 | 5.8% | 7,132 | 5.0% | 1,478 | 1.0% | 143,052 |

| 2013 | 80,008 | 42.8% | 93,314 | 49.9% | 6,979 | 3.7% | 6,254 | 3.3% | 550 | 0.3% | 187,105 |

| 2014 | 79,403 | 43.3% | 90,827 | 49.6% | 6,589 | 3.6% | 5,903 | 3.2% | 479 | 0.3% | 183,201 |

| Unilingual Positions | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province, Territory or Region | Bilingual | English Essential | French Essential | English or French Essential | Incomplete Records | Total | |||||

| British Columbia | 507 | 3.2% | 15,404 | 96.4% | 1 | 0.0% | 32 | 0.2% | 28 | 0.2% | 15,972 |

| Alberta | 378 | 4.1% | 8,717 | 95.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 45 | 0.5% | 11 | 0.1% | 9,151 |

| Saskatchewan | 138 | 3.1% | 4,362 | 96.7% | 1 | 0.0% | 6 | 0.1% | 2 | 0.0% | 4,509 |

| Manitoba | 524 | 8.1% | 5,929 | 91.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 17 | 0.3% | 7 | 0.1% | 6,477 |

| Ontario (excluding the NCR) | 2,525 | 10.8% | 20,674 | 88.5% | 13 | 0.1% | 127 | 0.5% | 30 | 0.1% | 23,369 |

| National Capital Region (NCR) | 55,200 | 67.5% | 20,779 | 25.4% | 152 | 0.2% | 5,390 | 6.6% | 242 | 0.3% | 81,763 |

| Quebec (excluding the NCR) | 13,743 | 67.1% | 148 | 0.7% | 6,390 | 31.2% | 141 | 0.7% | 56 | 0.3% | 20,478 |

| New Brunswick | 3,475 | 53.7% | 2,885 | 44.6% | 20 | 0.3% | 80 | 1.2% | 6 | 0.1% | 6,466 |

| Prince Edward Island | 482 | 29.4% | 1,154 | 70.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 1,637 |

| Nova Scotia | 899 | 11.0% | 7,161 | 87.3% | 12 | 0.1% | 43 | 0.5% | 90 | 1.1% | 8,205 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 110 | 3.9% | 2,723 | 95.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 10 | 0.4% | 2 | 0.1% | 2,845 |

| Yukon | 16 | 5.2% | 291 | 94.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 308 |

| Northwest Territories | 10 | 2.6% | 379 | 97.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 389 |

| Nunavut | 14 | 6.1% | 211 | 92.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 1.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 229 |

| Outside Canada | 1,382 | 98.5% | 10 | 0.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 6 | 0.4% | 5 | 0.4% | 1,403 |

| Total | 79,403 | 43.3% | 90,827 | 49.6% | 6,589 | 3.6% | 5,903 | 3.2% | 479 | 0.3% | 183,201 |

| Do Not Meet | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Meet | Exempted | Must Meet | Incomplete Records | Total | ||||

| 1978 | 36,446 | 69.7% | 14,462 | 27.7% | 1,392 | 2.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 52,300 |

| 2000 | 41,832 | 82.8% | 5,030 | 10.0% | 968 | 1.9% | 2,705 | 5.4% | 50,535 |

| 2013 | 76,332 | 95.4% | 2,867 | 3.6% | 268 | 0.3% | 541 | 0.7% | 80,008 |

| 2014 | 75,881 | 95.6% | 2,776 | 3.5% | 178 | 0.2% | 568 | 0.7% | 79,403 |

| Year | Level C | Level B | Level A | Other | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | 3,771 | 7.2% | 30,983 | 59.2% | 13,816 | 26.4% | 3,730 | 7.1% | 52,300 |

| 2000 | 12,836 | 25.4% | 34,677 | 68.6% | 1,085 | 2.1% | 1,937 | 3.8% | 50,535 |

| 2013 | 26,302 | 32.9% | 51,478 | 64.3% | 621 | 0.8% | 1,607 | 2.0% | 80,008 |

| 2014 | 26,333 | 33.2% | 50,968 | 64.2% | 560 | 0.7% | 1,542 | 1.9% | 79,403 |

| Do Not Meet | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Meet | Exempted | Must Meet | Incomplete Records | Total | ||||

| 1978 | 20,888 | 70.4% | 8,016 | 27.0% | 756 | 2.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 29,660 |

| 2000 | 26,766 | 82.3% | 3,429 | 10.5% | 690 | 2.1% | 1,631 | 5.0% | 32,516 |

| 2013 | 43,916 | 95.9% | 1,438 | 3.1% | 157 | 0.3% | 265 | 0.6% | 45,776 |

| 2014 | 42,724 | 95.8% | 1,471 | 3.3% | 97 | 0.2% | 301 | 0.7% | 44,593 |

| Year | Level C | Level B | Level A | Other | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | 2,491 | 8.4% | 19,353 | 65.2% | 7,201 | 24.3% | 615 | 2.1% | 29,660 |

| 2000 | 9,088 | 27.9% | 22,421 | 69.0% | 587 | 1.8% | 420 | 1.3% | 32,516 |

| 2013 | 17,141 | 37.4% | 28,270 | 61.8% | 290 | 0.6% | 75 | 0.2% | 45,776 |

| 2014 | 16,972 | 38.1% | 27,286 | 61.2% | 258 | 0.6% | 77 | 0.2% | 44,593 |

| Do Not Meet | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Meet | Exempted | Must Meet | Incomplete Records | Total | ||||

| 2013 | 53,595 | 95.4% | 2,038 | 3.6% | 174 | 0.3% | 372 | 0.7% | 56,179 |

| 2014 | 53,486 | 95.7% | 1,924 | 3.4% | 114 | 0.2% | 379 | 0.7% | 55,903 |

| Year | Level C | Level B | Level A | Other | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 19,122 | 34.0% | 35,659 | 63.5% | 272 | 0.5% | 1,126 | 2.0% | 56,179 |

| 2014 | 19,085 | 34.1% | 35,472 | 63.5% | 248 | 0.4% | 1,098 | 2.0% | 55,903 |

| Do Not Meet | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Meet | Exempted | Must Meet | Incomplete Records | Total | ||||

| Note: This table excludes employees working outside Canada | |||||||||

| 2013 | 22,922 | 95.4% | 786 | 3.4% | 135 | 0.6% | 125 | 0.5% | 22,968 |

| 2014 | 21,584 | 95.6% | 774 | 3.4% | 83 | 0.4% | 132 | 0.6% | 22,573 |

| Year | Level C | Level B | Level A | Other | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note: This table excludes employees working outside Canada | |||||||||

| 2013 | 11,962 | 52.1% | 10,923 | 47.6% | 45 | 0.2% | 38 | 0.2% | 22,968 |

| 2014 | 12,085 | 53.5% | 10,408 | 46.1% | 40 | 0.2% | 40 | 0.2% | 22,573 |

| Province, Territory or Region | Anglophones | Francophones | Unknown | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 15,690 | 98.2% | 282 | 1.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 15,972 |

| Alberta | 8,886 | 97.1% | 265 | 2.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 9,151 |

| Saskatchewan | 4,439 | 98.4% | 70 | 1.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 4,509 |

| Manitoba | 6,239 | 96.3% | 238 | 3.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 6,477 |

| Ontario (excluding the NCR) | 22,133 | 94.7% | 1,235 | 5.3% | 1 | 0.0% | 23,369 |

| National Capital Region (NCR) | 48,046 | 58.8% | 33,717 | 41.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 81,763 |

| Quebec (excluding the NCR) | 1,986 | 9.7% | 18,492 | 90.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 20,478 |

| New Brunswick | 3,563 | 55.1% | 2,903 | 44.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 6,466 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1,452 | 88.7% | 185 | 11.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 1,637 |

| Nova Scotia | 7,719 | 94.1% | 486 | 5.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 8,205 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 2,779 | 98.4% | 46 | 1.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 2,845 |

| Yukon | 298 | 96.8% | 10 | 3.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 308 |

| Northwest Territories | 377 | 96.9% | 12 | 3.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 389 |

| Nunavut | 206 | 90.0% | 23 | 10.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 229 |

| Outside Canada | 949 | 67.6% | 454 | 32.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 1,403 |

| All regions | 124,782 | 68.1% | 58,418 | 31.9% | 1 | 0.0% | 183,201 |

| Category | Anglophones | Francophones | Unknown | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management (EX) | 3,376 | 67.0% | 1,664 | 33.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 5,040 |

| Scientific and Professional | 23,598 | 74.2% | 8,203 | 25.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 31,801 |

| Administrative and Foreign Service | 50,398 | 61.0% | 32,196 | 39.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 82,594 |

| Technical | 9,613 | 76.4% | 2,977 | 23.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 12,590 |

| Administrative Support | 14,224 | 68.3% | 6,616 | 31.7% | 1 | 0.0% | 20,841 |

| Operations | 23,573 | 77.7% | 6,762 | 22.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 30,335 |

| All categories | 124,782 | 68.1% | 58,418 | 31.9% | 1 | 0.0% | 183,201 |

| Province, Territory or Region | Anglophones | Francophones | Unknown | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 33,353 | 96.0% | 1,363 | 3.9% | 11 | 0.0% | 34,727 |

| Alberta | 26,581 | 94.8% | 1,429 | 5.1% | 18 | 0.1% | 28,028 |

| Saskatchewan | 7,417 | 96.4% | 269 | 3.5% | 8 | 0.1% | 7,694 |

| Manitoba | 14,557 | 95.5% | 683 | 4.5% | 8 | 0.1% | 15,248 |

| Ontario (excluding the NCR) | 74,154 | 94.2% | 4,547 | 5.8% | 27 | 0.0% | 78,728 |

| National Capital Region (NCR) | 31,529 | 69.0% | 14,136 | 30.9% | 41 | 0.1% | 45,706 |

| Quebec (excluding the NCR) | 7,883 | 15.9% | 41,585 | 84.0% | 28 | 0.1% | 49,496 |

| New Brunswick | 7,118 | 74.3% | 2,459 | 25.7% | 6 | 0.1% | 9,583 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1,569 | 95.1% | 81 | 4.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 1,650 |

| Nova Scotia | 14,762 | 91.6% | 1,358 | 8.4% | 4 | 0.0% | 16,124 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 5,309 | 97.8% | 117 | 2.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 5,426 |

| Yukon | 355 | 93.9% | 23 | 6.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 378 |

| Northwest Territories | 575 | 90.7% | 59 | 9.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 634 |

| Nunavut | 195 | 85.5% | 33 | 14.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 228 |

| Outside Canada | 1,180 | 79.1% | 312 | 20.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 1,492 |

| All regions | 226,537 | 76.8% | 68,454 | 23.2% | 151 | 0.1% | 295,142 |

| Category | Anglophones | Francophones | Unknown | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management | 10,944 | 75.8% | 3,482 | 24.1% | 7 | 0.0% | 14,433 |

| Professionals | 26,623 | 73.1% | 9,755 | 26.8% | 43 | 0.1% | 36,421 |

| Specialists and Technicians | 18,985 | 75.3% | 6,161 | 24.4% | 61 | 0.2% | 25,207 |

| Administrative Support | 32,855 | 75.7% | 10,493 | 24.2% | 35 | 0.1% | 43,383 |

| Operations | 74,483 | 80.2% | 18,348 | 19.8% | 5 | 0.0% | 92,836 |

| Canadian Forces and Regular Members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 62,647 | 75.6% | 20,215 | 24.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 82,862 |

| All categories | 226,537 | 76.8% | 68,454 | 23.2% | 151 | 0.1% | 295,142 |

| Province, Territory or Region | Anglophones | Francophones | Unknown | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 49,043 | 96.7% | 1,645 | 3.2% | 11 | 0.0% | 50,699 |

| Alberta | 35,467 | 95.4% | 1,694 | 4.6% | 18 | 0.0% | 37,179 |

| Saskatchewan | 11,856 | 97.2% | 339 | 2.8% | 8 | 0.1% | 12,203 |

| Manitoba | 20,796 | 95.7% | 921 | 4.2% | 8 | 0.0% | 21,725 |

| Ontario (excluding the NCR) | 96,287 | 94.3% | 5,782 | 5.7% | 28 | 0.0% | 102,097 |

| National Capital Region (NCR) | 79,575 | 62.4% | 47,853 | 37.5% | 41 | 0.0% | 127,469 |

| Quebec (excluding the NCR) | 9,869 | 14.1% | 60,077 | 85.9% | 28 | 0.0% | 69,974 |

| New Brunswick | 10,681 | 66.6% | 5,362 | 33.4% | 6 | 0.0% | 16,049 |

| Prince Edward Island | 3,021 | 91.9% | 266 | 8.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 3,287 |

| Nova Scotia | 22,481 | 92.4% | 1,844 | 7.6% | 4 | 0.0% | 24,329 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 8,108 | 98.0% | 163 | 2.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 8,271 |

| Yukon | 653 | 95.2% | 33 | 4.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 686 |

| Northwest Territories | 952 | 93.1% | 71 | 6.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 1,023 |

| Nunavut | 401 | 87.7% | 56 | 12.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 457 |

| Outside Canada | 2,129 | 73.5% | 766 | 26.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 2,895 |

| All regions | 351,319 | 73.4% | 126,872 | 26.5% | 152 | 0.0% | 478,343 |

Page details

- Date modified: