The Canadian Guide to Understanding and Combatting Islamophobia: For a more inclusive Canada

The drafting of this guide was led by the Office of the Special Representative on Combatting Islamophobia.

On this page

- Land Acknowledgment

- Permission to reproduce

- Message from the Special Representative

- Executive Summary

- Chapter One: Islamophobia Landscape in Canada

- Chapter Two: Islamophobia today

- Chapter Three: Impacts of Islamophobia

- Chapter Four: Islamophobia and intersecting identities

- Chapter Five: Navigating media narratives and stereotypes

- Chapter Six: Strategies for Combatting Islamophobia

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1: Glossary

- Appendix 2: Islam and Muslims

Alternate format

The Canadian Guide to Understanding and Combatting Islamophobia: For a more inclusive Canada [PDF version - 5.4 MB]

Land Acknowledgment

The Office of the Special Representative on Combatting Islamophobia respectfully acknowledges that it is in the National Capital Region, which is located on the traditional unceded territory of the Algonquin Anishinaabeg People. The Office acknowledges the responsibility it shares as guests on this land and is committed to learning about the history and culture of First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples, taking meaningful steps towards addressing harms, and advancing in the journey towards reconciliation.

Permission to reproduce

The text in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. Commercial reproduction and distribution are prohibited except with written permission from Canadian Heritage (PCH).

To request permission for commercial use, please contact PCH at publications@pch.gc.ca.

About the cover: The Office of the Special Representative on Combatting Islamophobia’s logo was created through a collaboration with the Department of Canadian Heritage and community members with an interest in design and community representation. The geometric shapes are often found within Islamic art and symbolize interconnectedness and harmony. The selected shades of purple and green represent the colours used to honour “Our London Family” and the victims of the Quebec Mosque massacre. Purple was the late Yumnah Afzaal’s favourite colour; green represents the carpet of the Quebec City Mosque where the worshippers took their last breaths. The maple leaf at the centre represents Canada.

Message from the Special Representative

Islamophobia challenges safety and well-being, undermines social cohesion and threatens our democratic values.

It spans a broad spectrum of behaviours—from bias and discrimination to racism and hate—and can be experienced in workplaces, schools, public settings and throughout all facets of society. Institutional forms of Islamophobia mean that, at times, the very institutions and systems that are meant to protect or support Canadian Muslims can discriminate and cause harm.

The federal government created the role of a Special Representative on Combatting Islamophobia with a mandate that includes enhancing efforts to combat Islamophobia and promoting awareness of the diverse and intersectional identities of Muslims in Canada.

While no one resource can be fully exhaustive, this Guide offers a holistic Canadian view of Islamophobia, its manifestations and various strategies to combat it. It is based on numerous books, reports and studies, including a report I was pleased to contribute to, titled Islamophobia At Work, published by the Canadian Labour Congress and which is referenced in these pages.

This new Guide is meant for everyone: educators, employers, administrators, decision makers, journalists, lawyers, judges, law enforcement, students and community leaders. In short, it is for all Canadians who seek to combat Islamophobia.

Our team conducted extensive consultation with stakeholders from across government, civil society and community. I extend my sincere appreciation for their contributions.

Special thanks as well to Canadian Muslim civil society organizations, academics, advocates and local community leaders. These people and groups dedicate their time and knowledge towards defending the rights and freedoms of Canadian Muslims, and towards upholding our shared values, promoting civic engagement and defending our democratic ideals.

Finally, I would also like to extend my gratitude to the Honourable Kamal Khera, Minister of Diversity, Inclusion and Persons with Disabilities, for her commitment and support towards combatting Islamophobia and all forms of hate and discrimination.

Combatting Islamophobia requires action from all orders of government, the private sector, media, public institutions including schools and universities, civil society organizations and everyday Canadians. Together, we can take steps to ensure Canadian Muslims can live lives of dignity and respect, free from harassment and discrimination.

Thank you for being here and joining in the effort to help build a Canada that is fairer, more equitable and welcoming to all.

Amira Elghawaby

Canada’s Special Representative on Combatting Islamophobia

Executive Summary

Canada is often described as a multicultural, pluralistic nation—a country that welcomes people from around the world to build their lives, raise their families and contribute to its collective success. These values are enshrined in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Canadian Human Rights Act and provincial and territorial legislations.

Alongside the painful legacy of colonialism and its ongoing impacts on First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities, racism, hate and discrimination continue to affect the lives of many Canadians citizens, permanent residents, refugees and newcomers alike.

Islamophobia negatively impacts the lives of the members of Canada’s diverse Muslim communities and those who are perceived to be Muslim. Like all forms of discrimination and hate, Islamophobia is multi-faceted. It can be systemic in nature, perpetuated by institutional systems in policies, actions or inaction. It can be at the community level, within workplaces and educational/service settings. And it can occur at the individual level. For many Canadian Muslims, Islamophobia is a daily reality, as highlighted in the 2023 Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights' report, Combatting Hate: Islamophobia and its Impact on Muslims in Canada. Islamophobia can include violations of religious freedom, a fundamental protection under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and international agreements. Despite efforts to foster inclusion and equality, Islamophobia continues to impact Canadian Muslims, leading to multiple tragic mass killings. In fact, Canada has the highest number of targeted killings of Muslims among G7 nations.Footnote 1

In response to these tragic events, the Government of Canada, alongside Canadians from coast to coast to coast, has launched various initiatives to combat Islamophobia. This Guide is intended to support the objectives of Canada’s Anti-Racism Strategy 2024-2028 and Canada’s Action Plan on Combatting Hate, and ultimately strengthen social cohesion and inclusion in Canadian society. The Guide does not constitute a binding directive on any government department or agency and is not legally binding.

The Guide is organized around three overarching themes. First, we present a conceptual understanding of Islamophobia, offering a detailed definition, key drivers, and examples of its manifestations. Second, the Guide examines the impacts of Islamophobia on diverse communities. The last chapter presents practical strategies for individuals and organizations to prevent and combat Islamophobia to actively contribute to an inclusive society.

Chapter One: Islamophobia Landscape in Canada

Who are Canadian Muslims?

Islam is Canada’s second most reported religion. Nearly 1.8 million people, or 1 in 20 Canadians, declared Islam as their faith in 2021. In 20 years, the share of the Muslim population in Canada has more than doubled from two percent in 2001 to around five percent in 2021.Footnote 2

The arrival of Muslims as settlers to Canada predates Confederation, well before the British North America Act in 1867Footnote 3. Although the first documented arrival of Muslims was in 1854, historians believe that Black Muslims from West Africa arrived during the transatlantic slave trade as early as the 1700sFootnote 4. Throughout the 1900s, the Muslim population grew with the arrival of newcomers from Africa, Europe, the Middle East and Asia.

Between 2011 and 2021, 18.9 percent of immigrants reported being Muslim. Ontario and Quebec have the highest percentage of Muslims, with 10 percent living in the Greater Toronto Area and 8.7 percent in Greater MontrealFootnote 5. Muslim communities across Canada have established places of worship, advocacy organizations and educational spaces, which are vital in enhancing a sense of community and safety for individuals and families, as well as encouraging civic engagement and inclusion. Canadian Muslims contribute positively to every facet of public life, shattering stereotypes and challenging biases each day.

What are Islamic Values?

Before addressing Islamophobia, it is important to understand Islam and how those who consider themselves its followers, Muslims, generally view their faithFootnote 6. Islam is one of the fastest-growing religions globally, and Muslims are encouraged to uphold universal core values including peace, freedom, justice, mercy, equality and human dignity.

Research across 39 countries with significant Muslim populations highlights the importance of unity, diversity and community within IslamFootnote 7. Muslims place strong emphasis on building cohesive communities through various means. These include collective prayers at mosques, organizing charity events like food drives during Ramadan, or supporting local and humanitarian causes through charitable donations.

For example, in 2022, the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) in Canada noted that individual Canadian Muslims, as well as Canadian Muslim organizations, were among the top 10 donors to its Refugee Zakat Fund reflecting the strong sense of humanitarian giving that exists among Canadian Muslim communities, for all communitiesFootnote 8. This mirrors the generosity of Canada as a whole which is one of the top ten donor countries to the UNHCR.

Such values align with Canadian principles of care, giving and community service, alongside respect for multiculturalism, interculturalism and human rights.

What is Islamophobia?

The word “Islamophobia” was likely coined in France around 1910 (“Islamophobie”)Footnote 9. The English version, Islamophobia, was already in use globally by the time it was defined in 1997 as “unfounded hostility towards Muslims, and therefore fear or dislike of all or most Muslims.”Footnote 10

Some prefer to use the words “anti-Muslim racism” or “anti-Muslim bigotry” to avoid appearing to describe what some might misperceive as an “irrational fear” instead of an intentional, targeted hatred. Several reports by the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) suggest that anti-Muslim hatred and discrimination should be understood through the concept of racialization which involves viewing Muslims, or those perceived as Muslim, as different based on factors like religion, ethnicity or appearanceFootnote 11. ECRI also notes that anti-Muslim racism is not just about hostility toward religion but is deeply connected to other forms of exclusion, such as anti-immigrant sentiments, xenophobia, gender bias and social class discriminationFootnote 12.

The Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights (2022) discussed different terms and definitions and noted that Islamophobia is the term most commonly used in CanadaFootnote 13.

Canada’s Anti-Racism Strategy 2024-2028 defines Islamophobia as including:

Racism, stereotypes, prejudice, fear or acts of hostility directed towards individual Muslims or followers of Islam in general. In addition to individual acts of intolerance and racial profiling, Islamophobia can lead to viewing and treating Muslims as a greater security threat on an institutional, systemic and societal levelFootnote 14.

Islamophobia takes many forms ranging from bias and discrimination to harassment and hate. It also occurs on three key levels (system-level, community-level and individual)Footnote 15:

- System-level Islamophobia refers to systemic discrimination, often seen in laws and policies that target or are biased against Muslims. This can include biased practices in policing and security screening, the justice system, negative portrayals in the media, widespread discriminatory actions within government institutions and harmful rhetoric from political leaders. This type of discrimination can also occur when religious minorities, including Muslims, are prevented from exercising their freedom of religion or expression as outlined in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms by a government or state institution without it being demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.

- Community-level Islamophobia is reflected in actions such as the rise of hate groups, anti-Muslim protests, opposition to mosque construction, vandalism and resistance to welcoming refugees and newcomersFootnote 16. These activities target Muslims and their places of worship or settlementFootnote 17.

- Individual Islamophobia refers to actions perpetrated by individuals and is experienced on a personal level, where Muslims may face discrimination, harassment, verbal abuse or physical violence because of their faith.

What is Islamophobic – and what is not?

Non-Islamophobic actions, behaviours and rhetoric: Combatting Islamophobia is not about clamping down on freedom of expression. Criticism of Islam or opposition to Islamic doctrines is not Islamophobic, nor is criticism of Muslim-majority countries, so long as criticism is not used as a means of targeting or casting entire populations as responsible for the actions of their leaders, governments or a few individualsFootnote 18.

Expressing negative views of a Muslim-led government because of its policy decisions or actions, including those which violate international human rights, are legitimate forms of speech and do not constitute Islamophobia.

Islamophobic actions, behaviours and rhetoric: Islamophobia occurs when a person targets or excludes a Muslim (or a person perceived to be Muslim) because of their faith (or perceived faith). Even non-Muslims, like Arab Christians, Hindus and Sikhs, experience Islamophobia because of perceptions of their skin colour or attire (as with Sikh men), or their language (such as Arabic).

Islamophobia also occurs when violent or harmful actions committed by individual Muslims or groups are then attributed to, or blamed on, all Muslims everywhere, even where such actions have been condemned. It is unjust to label any entire religious group as responsible for the actions of extremists or individuals who engage in violence or criminal activity. Similarly, it is unfair to hold all Muslims accountable for the actions of those who misinterpret or distort the faith to justify violence or oppression. Throughout history, violent extremists from various religious communities have used religious doctrine to justify harmful behaviors, including criminality and acts of terror. Those who do so should be held fully accountable under the law.

Peaceful adherents of any religion should not be expected to apologize or be made to explain any violence, harm, or the violation of human rights committed in the name of their faith. Nor should they be made to feel as though they live under a cloud of suspicion, deserve fewer human rights protections or must lose their civil liberties in the name of fighting terrorism.

Open and closed views of Islam: At a glance

The Runnymede Trust in the United Kingdom created a table to highlight the differing views associated with Islam and, by extension, MuslimsFootnote 19. The table below is a modified version of the “closed” and “open” views presented in its report.

Closed views often involve a fixed, negative view of certain racial or ethnic groups. These views may include prejudices, stereotypes or an unwillingness to accept or understand cultural differences. Open or positive views are inclusive, flexible and accepting of diversity.

The myths and facts section that follows provides further context based on this summary.

| Closed views | Open views |

|---|---|

| Muslims are monolithic, unchanging, and unresponsive to new realities. | Muslims are diverse, with internal differences, debates and development. |

| Muslims are a separate group without any shared aims or values with other cultures. | Muslims are connected to other faiths and cultures, sharing common values and goals. |

| Muslims are inferior to the West—barbaric, irrational, primitive, sexist. | Muslims may be different in their faith but not deficient and as equally worthy of respect. |

| Muslims are violent, security threats, supportive of terrorism, and engaged in “a clash of civilizations.” | Muslims are integral and valued members of society with a rich history of contributions to world civilization and development. |

| Muslims are harbouring ulterior political ideology for political or military advantage and will hide their true goals to advance their political aims. | Muslims are a diverse group with varied political beliefs, and their views—religious and political—are shaped by many factors. |

| Muslims deserve to be subject to discriminatory practices because their belief system contradicts human rights. | Muslims, like other faith groups, are guaranteed human rights, and should be protected from discrimination and hate. |

| Anti-Muslim hostility is normalized in society based on bias and stereotypes. | Anti-Muslim hostility is rejected like other forms of discrimination and hate. |

Myths vs. facts

The best way to counter myths is to present facts. Below are some examples of factual explanations of the various myths that can lead to closed views of Muslims.

MYTH: All Muslims are monolithic, unchanging and unresponsive to new realities.

This myth conveys the false belief that Muslims, as a group, are a singular entity with unvarying beliefs, practices and behaviours. It implies that Islam, and those who follow it, are stuck in time, resistant to progress, and unwilling or incapable of adapting to the evolving demands of modern society. This myth reduces a diverse and dynamic group of people to a static, unchanging image. It erases the complexity of Muslim identities, cultures and responses to contemporary issues.

FACTS: Muslims around the world are diverse and actively engaged in navigating the complexities of modern life.

There are over two billion Muslims worldwide. This makes Islam one of the largest and most diverse religions in the world, encompassing a wide range of cultures, ethnicities, traditions and worldviews. The diversity within the Muslim population is immense, with Muslims living across different continents, speaking different languages, and following various schools of thought and practices based on their own personal experiences and contexts.

In 2021, over 60 percent of Muslims in Canada who were born outside Canada came from 10 different countries, including Pakistan, Algeria, Iran, Somalia, Lebanon and TurkeyFootnote 20. These countries represent a range of cultures, languages, ethnic backgrounds and traditions, which means that Muslims in Canada are not a homogeneous group.

Canadian Muslims, including young people and second-generation Muslims, are increasingly advocating for social justice, climate justice and gender equity—all while remaining committed to their faith. Canadian Muslims are not unresponsive to modern realities. They actively engage with contemporary issues in ways that reflect their individual and community values.

MYTH: Muslims are a separate group without any shared aims or values with other cultures.

This myth creates a false and harmful stereotype by depicting Muslims as an isolated, homogeneous group that is fundamentally different and disconnected from other cultural or religious communities.

This myth suggests that Muslims do not share common goals, desires or values with other cultures and communities. It implies that Muslims are isolated in their belief systems and are uninterested in or hostile to societal issues that concern others, such as social justice, economic progress, human rights, gender equality or environmental sustainability.

FACTS: Muslims participate in shared civic and social life and contribute to the development and progress of the broader communities they live in.

Muslims are part of many different societies, including multicultural nations like Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom and others, where they interact daily with people from diverse backgrounds.

Muslims also contribute financially and charitably to society. In Islam, Zakat and Sadaqat is a fundamental pillar of the faith. It emphasizes the importance of giving to those in need, like Christian teachings on charity and the Jewish concept of tzedakah. Similarly, Muslim organizations often work alongside Christian, Jewish and other faith or secular groups to provide aid and support to communities in need. For instance, the Kanata Muslim Association (KMA) partnered with the Kanata United Church (KUC) to raise funds for family programs and one of busiest food banks in the city of OttawaFootnote 21.

Another remarkable example of Canadian Muslim contributions to the greater good was demonstrated by a blood drive in 2022. Organized by a Toronto-based charity, with support from 27 countries, the group successfully rallied over 37,000 blood donations in a single day, setting a world record. This act of generosity demonstrates the commitment of Muslims to the health and well-being of their communities, showing that they are dedicated to giving back to society in meaningful waysFootnote 22.

MYTH: Muslims are violent, security threats, supportive of terrorism, and are engaged in “a clash of civilizations.”

The myth that Muslims are violent and pose security threats is a harmful and pervasive stereotype that paints all Muslims as inherently dangerous, radical and supportive of terrorismFootnote 23. This myth has been fueled by fearmongering, misrepresentation and political rhetoric over the past several decades. This has been especially true in the wake of the terrorist attacks in New York City on September 11, 2001, and the later rise of extremist groups like ISIS/DaeshFootnote 24. Studies show that after 9/11, Islamophobic hate crimes surged in Europe and North America, including CanadaFootnote 25. Between 2009 and 2020, police-reported anti-Muslim hate crimes in Canada showed a steady rise, from 36 incidents in 2009 to 99 in 2014. In 2015, reported incidents surged to 159, a 60 percent increase, and in 2017, the number jumped to 349, marking a 150 percent riseFootnote 26. Many Canadian Muslims have shared how they faced increased discrimination and hate following 9/11, and were often perceived as sympathetic to terrorism and violenceFootnote 27.

This myth often ties Muslims to the concept of a “clash of civilizations,” popularized by political scientist Samuel Huntington in the 1990sFootnote 28. According to this theory, there is an inherent and inevitable conflict between Islam and Western civilization, with Muslims positioned as the antagonistic “other.”Footnote 29

This narrative frames Muslims as being in opposition to the values of Western democracies, such as freedom, secularism and individual rights, suggesting that Islam and the West are incompatible and always in conflict. This view reduces a diverse group of over two billion Muslims to a single, monolithic entity, disregarding the variety of political views, lifestyles and social values within Muslim communitiesFootnote 30.

Figure 1: Image of a grey castle, labelled “The West.”– text version.

In front of the castle gate is a huge wooden horse on wooden rollers, with the word “Islam” written on it. The image implies Muslims are hiding inside the horse, that will be wheeled into “the West.”Footnote 31

A key part of this myth is the concept of the “Islamic Trojan Horse.” This idea suggests that Muslim immigrants or refugees are secretly infiltrating Western societies with the goal of undermining national values, spreading extremism and replacing local cultures with Islamic norms. This misconception gained traction in Europe and was particularly associated with the 2014 Trojan Horse scandal in the United Kingdom, when a letter falsely accused Muslim groups of attempting to take over schools in Birmingham by promoting extremism and Shariah law. Despite a lack of evidence, the story circulated widely, leading to increased scrutiny and the policing of Muslim communitiesFootnote 32.

Far-right political groups in Canada also echoed the Trojan Horse trope, suggesting that Muslim refugees and immigrants posed a risk to Canadian society, further reinforcing the idea of Muslims as a dangerFootnote 33.

FACTS: While extremist groups may claim to represent Islam, their views are rejected by most Muslims around the world, who understand that terrorism and violence are contrary to the teachings of IslamFootnote 34.

Violence perpetrated by extremist groups or individuals affects everyone and has led to the killing of countless numbers of people of a variety of faith and ethnic backgrounds, including a significant number of Muslims living in Muslim-majority countriesFootnote 35. In Canada, Muslim organizations and religious leaders are involved in initiatives aimed at promoting peace, countering violent extremism and encouraging interfaith dialogue. These efforts are crucial in fostering a sense of shared responsibility in the fight against terrorism and radicalization.

Very few Muslims believe there is much, if any, support within their community for violent extremist activities at home or abroad. At the same time, there is almost universal agreement on the importance of actively working with government agencies to address any potential threats. – Environics Survey of Muslims in Canada, 2016Footnote 36

The idea of a “clash of civilizations” oversimplifies the complex relationships and interactions between cultures and peoples and has been critiqued as a “clash of ignorance.”Footnote 37 The lens through which some Western intellectual traditions have historically viewed Muslim-majority societies has been described in Edward Said’s seminal work as “Orientalism.” For centuries, much of Western culture portrayed Muslims as exotic “Others” and rationalized colonial domination of Muslim-majority-held landsFootnote 38.

Following the tragic events of September 11, 2001, negative stereotypes and misleading images of Muslims became more common in public discourse that lacked nuance or balance. Immediately following the attacks of 9/11, then Prime Minister Jean Chretien rejected such a binary view:

The evil perpetrators of this horror represent no community or religion. They stand for evil, nothing else. As I said, this is a struggle against terrorism, not against any one community or faith. Today more than ever we must reaffirm the fundamental values of our charter of rights and freedoms: the equality of every race, every colour, every religion and every ethnic originFootnote 39.

Despite efforts to counter harmful narratives about Muslims, misleading portrayals have influenced public policy, especially in the years following 9/11, and continue to persist to the present dayFootnote 40.

MYTH: Muslims are seen as inferior to the West—barbaric, irrational, primitive, sexist.

Islamophobic tropes often depict Muslims as living in the past, adhering to barbaric practices that are incompatible with modernity. These views paint Muslims as primitive, irrational and sexist, reinforcing the idea that they are fundamentally inferior to Western cultures. Critics will often point to practices that are widely condemned by many Muslims, including female genital mutilation, forced marriages and so-called honour killings (a form of femicide), as evidenceFootnote 41.

These depictions of Muslims as barbaric are not new. They go back hundreds of years. The image below, drawn in the nineteenth century, portrays the conflict between the British and Sudanese as a struggle of the forces of “civilization” against the forces of “barbarism.” It reflects some attitudes in the West at the time when colonialism and imperialism was at its height.

Figure 2: Conflict between the British and Sudanese – text version.

White-skinned Britannia in a long white dress, with flowing yellow hair, carrying a large white flag labeled "Civilization," with British soldiers and colonists behind her. She is walking over dark-skinned men, who wear cloth around only their waist, toward a group of men fighting back, one of whom is on a horse carrying a flag labeled "Barbarism." The British colonists carry guns, the other side carry spears and shieldsFootnote 42.

While the culture today is different to when Udo Keppler created the illustration, the underlying tropes about Muslims and Muslim-majority countries persist. These portrayals dehumanize Muslims by presenting them as violent, sexist, backward and in constant conflict with the West, further embedding the belief that they are inherently incompatible with modern Western values.

One of the most pervasive aspects of this myth is the portrayal of Muslim women as oppressed and subjugated. This reinforces the idea of Muslim societies as inherently sexist and barbaric, compared to Western ideals of gender equality.

FACTS: Muslims who choose to practice Islam are exercising their personal freedom and deserve to be afforded the same respect and dignity as any other faith practitioner, and this includes Muslim women. Intellectual exploration, scientific discovery and an embrace of modernity are evidenced in Muslim communities.

Canadian Muslims, like their counterparts worldwide, are not only valued members of society but are also crucial contributors to the advancement of humanity in medicine, technology, social justice and humanitarian work.

They challenge the harmful stereotypes that position Muslims as inferior. They show instead that they are dynamic, diverse and vital to the social and cultural fabric of their communities and that they strive for professional and academic excellence in a variety of fieldsFootnote 43.

Historically, Muslims have played a key role in advancing human progress. During the Islamic Golden Age (8th-13th centuries), scholars like Ibn Sina and Al-Razi advanced medical knowledge, while Al-Khwarizmi made foundational contributions to mathematics, including the development of algebraFootnote 44. These contributions helped shape Western science and medicine. Muslims also contributed to world culture through architecture, art and literature, as seen in the creation of masterpieces like the Alhambra in Spain and the Taj Mahal in India. These achievements showcase the cultural richness of Islamic civilization.

Muslim women have made and continue to make significant contributions to various fields, both historically and in modern times. Examples include Fatima al-Fihri, a Muslim woman from North Africa in the 9th century, who founded the University of Al-Qarawiyyin in Fez, Morocco, which is recognized by UNESCO and the Guinness World Records as the oldest existing, continually operating degree-granting university in the world. In the field of medicine, Zaynab al-Sha'bi, a 9th-century Arab physician, was noted for her expertise in treating wounds and her contributions to medical knowledge. In the field of social justice, Lila Fahlman stood out as an educator, social justice advocate and the founder of the Canadian Council of Muslim Women. She is renowned for her groundbreaking contributions as the first Muslim woman in Canada to earn a PhD in Educational Psychology, serve on a public school board and become a university chaplain, while promoting interfaith dialogue and advocating for women.

A reductionist view of Muslim women fails to recognize the diversity of experiences and roles that Canadian Muslim women play in all aspects of society, where they contribute fully as equal and respected community members. The instrumentalization of the hijab or niqab as symbols of Muslim women’s oppression ignores the personal reasons why many women in Canada may choose to wear these garments and assumes a lack of agency. When women are denied the right to make their own decisions about what they wear in public, in the name of secularism or equality, the outcome can lead to discrimination.

Acts that violate human rights, bodily integrity, or that are criminal in nature, including all forms of gender-based violence, are fully contrary to the teachings of Islam, as made clear by numerous international and national Canadian Muslim organizations, scholars and various expert bodiesFootnote 45.

MYTH: Muslims are harbouring ulterior political ideology for political or military advantage and lying about it.

The myth that Muslims are seen as harbouring an ulterior political ideology for political or military advantage is based on the false assumption that Muslims, as a group, have secret political or religious motives that are harmful to wider Western societiesFootnote 46. This stereotype suggests that Muslims are aligned with some hidden agenda or radical political movement aimed at undermining or controlling other societies, often framed as a “global jihad” or conspiracy to take over governments or impose Islamic ruleFootnote 47.

Like the “Trojan Horse” trope, other imagery and narratives about a Muslim invasion seeking to take control of society and institutions, both covertly and overtly, have emerged. The concept of “Muslim invaders” is often portrayed as a precursor to a larger “jihad”Footnote 48 against Western nationsFootnote 49. The term “Jihad” has been misappropriated to promote the narrative of a military and/or political Muslim takeover and fueled further by right-wing media to cement an existential and political threat in the minds of some CanadiansFootnote 50. A full description of the term is found in Appendix 2.

This “Muslim invader” rhetoric has been used globally, including in Canada, and is prevalent in online media discussions, which can be interchanged with the “Great Replacement Theory.”Footnote 51 Variations of this theory include the false belief that white populations in Western countries are deliberately being replaced by non-white people, which can include Muslims. The conspiracy theory also has roots in antisemitic notions that “Jewish elites” are responsible for the “replacement” plotFootnote 52.

Such language has been adopted by white nationalists to justify acts of hate and terrorism, such as the tragic Christchurch, New Zealand, shooting in 2019, which resulted in the deaths of fifty-one Muslim worshippersFootnote 53. The shooter’s actions were motivated by a belief in the Muslim invasion of the WestFootnote 54. These Islamophobic ideologies frequently intersect with racist fears, presenting Islam as both a cultural and civilizational threat. At their core, these narratives blend racial and religious anxieties, with Islamophobia often serving as a vehicle for deeper racial prejudices.

Muslims are also often accused of lying or hiding their intentions. This accusation perpetuates Islamophobic stereotypes discussed in this sectionFootnote 55. Deliberately misrepresented or misunderstood concepts in Islam are sometimes used to make claims that Muslims conceal or disguise their beliefs for political motivesFootnote 56.

FACTS: Muslims, like any other group, hold diverse political beliefs, and their actions and intentions should not be generalized or assumed to be driven by a hidden agenda. Many Muslims prioritize peace, social justice and the well-being of their communities, just like individuals of any other faith or background.

A 2016 Environics Institute survey of Muslims in Canada revealed a clear counter-narrative to the above myth. Over 80 percent of Muslim respondents expressed being very proud to be Canadian, which is a higher percentage than the non-Muslim populationFootnote 57. This demonstrates that Muslims, far from harbouring ulterior political motives, are deeply committed to the country they live in. Their Canadian identity was just as important as their Muslim identity, challenging the stereotype that Muslims are more loyal to their religious or political affiliations than to their home country.

Furthermore, Canadian Muslims overwhelmingly value freedom, democracy and Canada’s multiculturalism, all of which align closely with the core values of Canadian society. This suggests that the political views of Canadian Muslims are shaped by the same principles that define Canadian identity, rather than any secret political agenda. The survey results emphasize that Muslims’ religious beliefs and political views are complex and shaped by numerous factors, including their country of birth, age, gender, immigration status and regionFootnote 58. This diversity of experiences contradicts the myth that Muslims are a monolithic group united by a single political agenda.

Additionally, experiences of discrimination, especially among Muslim women, can impact one’s sense of belonging, further highlighting how lived experiences shape political views within the Muslim community. These factors show that Canadian Muslims, like fellow Canadians, navigate their identities and political beliefs based on personal experiences and social contexts, not through a hidden political agenda.

MYTH: Muslims deserve to be discriminated against because their belief system contradicts human rights.

Hostility toward Islam is often used to justify discriminatory practices and the exclusion of Muslims from mainstream society. One of the most visible symbols of Islam in public discourse is the hijab (headscarf) or niqab (face covering), which has been repeatedly debated in the context of its presence in public institutions and even the wider societyFootnote 59. The debates surrounding the hijab or niqab reflect broader, often negative views about Muslims, particularly Muslim women, and their place in Western societies. In Canada, prominent elected officials and public figures have at times denigrated or dismissed the agency and choice of Canadian Muslims when it comes to wearing the niqab or hijabFootnote 60.

Women who choose to wear the hijab or niqab must contend with prejudicial views, and political debatesFootnote 61. However, for many, the veil is a meaningful expression of personal choice and an essential part of their identityFootnote 62.

FACTS: Using negative views about Muslims to justify discriminatory practices is fundamentally at odds with the values enshrined in Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Canadian Human Rights Act, and the country’s multiculturalism policy.

Our country’s foundational principles emphasize equality, inclusivity and protection from discrimination. They reject the idea that Muslims or any other group should be subject to unjust treatment based on negative stereotypes.

Muslims, like all Canadians, are entitled to practice their religion freely and are protected from discriminatory treatment based on their faith or any religious clothing they choose to wear.

MYTH: Anti-Muslim hostility should be normalized in society.

There have been various studies, which will be further explored in the chapter on media, that demonstrate how media discourses depict Muslims as terrorists all too frequently.

On social media, such narratives are pervasive almost anytime Muslims are mentioned. In 2019, for example, a media company issued an apology after hateful comments were left on its Facebook page following the deaths of seven Syrian children in a Halifax house fire. The comments included: “good riddance”Footnote 63.

This myth can lead to the normalization of racial profiling, surveillance and discrimination, particularly at airports, border crossings or in law enforcement settings, where Muslims (especially those from Middle Eastern backgrounds) are more likely to be subjected to extra scrutinyFootnote 64.

FACTS: Anti-Muslim hostility should be rejected like other forms of discrimination and hate. Anti-Muslim hostility in Canada has significant consequences for the affected communities.

Normalizing Islamophobic hostility affects mental health, weakens social cohesion, perpetuates inequality in employment and education, and leads to violence and hate crimes. Canadian Muslims, like other minority groups, face systemic barriers to fully participating in society. For example, Muslim women experience discrimination in healthcare—particularly in maternal and mental health—where they can be treated dismissively or with prejudice by practitioners, leading to poorer outcomesFootnote 65. They are also underemployed at higher rates than the general population and less likely to hold full-time or senior management positions, contributing to economic precarityFootnote 66. Anti-Muslim hostility can escalate into violence, including hate crimes, or even terrorism.

Chapter Two: Islamophobia today

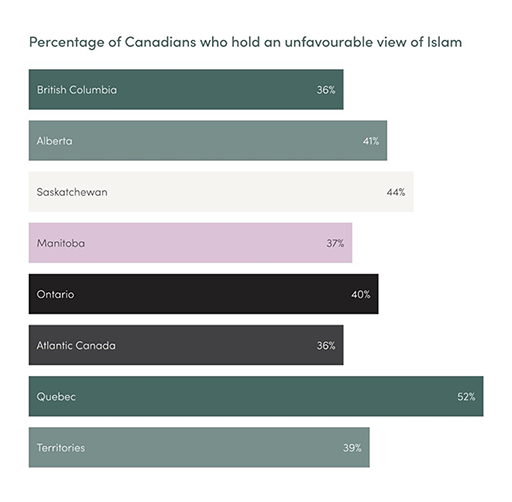

A 2023 study from the non-profit Angus Reid Institute found that across the country, Canadians are less likely to hold favourable views of Islam than five other major religions, namely Buddhism, Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism and SikhismFootnote 67. The following chart shows the percentage of Canadians in each province who hold an unfavourable view of Islam.

Figure 3: Percentage of Canadians who hold an unfavourable view of Islam – text version.

Table shows the percentage of people in each province who hold an unfavourable view of Islam. British Columbia: 36 percent. Alberta: 41 percent. Saskatchewan: 44 percent. Manitoba: 37 percent. Ontario: 40 percent. Atlantic Canada: 36 percent. Quebec: 52 percent. Territories: 39 percentFootnote 68.

The survey also found that two-thirds of Canadians are comfortable with a mosque in their neighbourhood, though the support for mosques remains lower than the level of support which exists for places of worship for the five other faith groups.

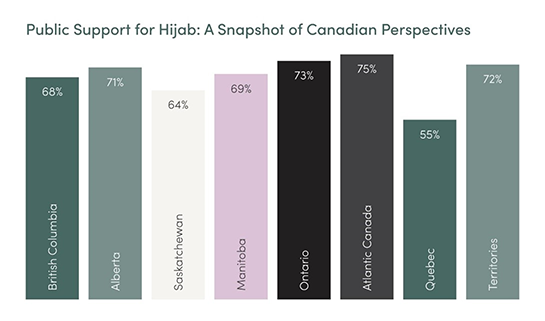

In terms of acceptance of religious symbols like the wearing of the hijab, support differs across the country. Many Canadians support people wearing religious symbols or clothing in public, as well as being comfortable working with people who wear such items, including the hijabFootnote 69. It is important to note that not all Muslim women wear the hijab, and among those who do, an even smaller subset choose to wear the face covering. Those who are visibly Muslim are at times particularly vulnerable to discrimination and anti-Muslim sentiments, which will be discussed in Chapter 4.

Figure 4: Public Support for Hijab: A Snapshot of Canadian Perspectives – text version

Table shows percentage of people in each province who support Muslim women wearing hijab in public. British Columbia: 68 percent. Alberta: 71 percent. Saskatchewan: 64 percent. Manitoba: 69 percent. Ontario: 73 percent. Atlantic Canada: 75 percent. Quebec: 55 percent. Territories: 72 percentFootnote 70.

A later study from Angus Reid, published in December 2023, found that 75 percent of Canadians view anti-Muslim hatred either as a major problem (22 percent), or as a problem among many (53 percent)Footnote 71.

According to a 2023 poll conducted by Leger Marketing, nearly half of Canadians (46 percent) expressed interest in receiving resources or tips on how to be better allies to Canadian MuslimsFootnote 72. The same survey also revealed that one-in-three non-Muslim Canadians (31 percent) indicated no interest in being an ally to Muslims. These findings suggest a mix of views on Islam in Canada, including some negative perspectives.

Drivers of Islamophobia

Economic Drivers

Times of economic hardship, such as rising income inequality and high unemployment, can contribute to IslamophobiaFootnote 73. When people struggle financially, they might look for someone to blame, often targeting groups that are different from themselves, like those with different ethnic backgrounds or religionsFootnote 74. This “scapegoating” can make people believe that these “outgroups” are responsible for their problemsFootnote 75. Economic downturns can make poverty and inequality worse, creating instability and conflict between different groupsFootnote 76. Some individuals or groups may take advantage of these difficult times to stir up hateFootnote 77. Islamophobia, in turn, can also worsen economic inequality for Muslim communities, especially for visibly Muslim womenFootnote 78. These women may face discrimination in hiring, promotions and even job opportunities, leading to fewer chances to advance or to underemploymentFootnote 79.

Political Drivers

The politics of hate exacerbate anti-Muslim sentiments, at home and abroad, and is fueled by geopolitical contexts. For instance, anti-immigrant attitudes can lead to intolerant attitudes towards minority faith communities. One European study discovered that anti-Muslim attitudes could exist even where there are few Muslims—a concept referred to as “phantom Islamophobia.”Footnote 80 The rise of white nationalism has also fueled anti-Muslim sentiments, leading to deadly attacks and a rise in the popularity of far-right political partiesFootnote 81.

UN experts highlighted on the 2024 International Day to Combat Islamophobia that political parties, armed groups, religious leaders and state actors worldwide are undermining religious diversity, violating human rights and justifying discrimination, particularly against Muslim minorities, for political gainFootnote 82. This can occur particularly ahead of elections, as both state and non-state actors exploit religious tensions and promote discriminatory laws and policies.

Religious intolerance or misinformation as Drivers

Prejudice can arise from misunderstandings, misinformation or misconceptions about Islam. This prejudice is perpetuated by a failure to appreciate the diversity within Muslim communities and a lack of knowledge or deliberate misinformation about the religion.

Stereotypes and biases can lead to religious intolerance which may also persist due to a lack of exposure to diverse cultural practices and can hinder efforts to promote greater understanding and foster mutual respect.

Media Drivers

Media play a significant role in shaping public perceptions. The media can deliberately or inadvertently create or reinforce distorted narratives that promote stereotypes, particularly towards marginalized communities, including MuslimsFootnote 83. As news is driven by big events, conflict or scandal, Muslims are frequently mentioned in the news media in association with terrorism or extremism, or their religious practices, overshadowing the diverse experiences and contributions of Muslim communitiesFootnote 84. This can magnify misconceptions, creating a narrative that portrays Muslims primarily through the lens of fear and suspicion, rather than as complex individuals with a wide range of identities and values. Studies have demonstrated that negative media portrayals of Muslims contribute to an increase in Islamophobic attitudes and behaviours, reinforcing stereotypes that Muslims are somehow dangerous or untrustworthyFootnote 85. This environment of mistrust further marginalizes Muslim voices, making it difficult for diverse narratives to emerge and be heard.

Additionally, the surge of online Islamophobia has become a pressing issue, exacerbated by the pervasive influence of social media platforms and content creators dedicated to misinformation and “rage-baiting” (a form of click-bait)Footnote 86. These platforms, designed to maximize user engagement, contribute to the spread of discriminatory narratives by fostering echo chambers and algorithmic biasFootnote 87. The rapid and viral dissemination of hate speech online translates into real-world consequences, even leading to deadly violence against MuslimsFootnote 88.

The “Islamophobia industry”

Various books and research reports have exposed the intricate web of networks influencing and funding Islamophobia, characterizing it as a burgeoning transnational sectorFootnote 89.

According to several findings, the Islamophobia industry comprises organized networks and industries that intentionally promote it and profit from itFootnote 90. Despite facing limitations in accessing essential financial documents for Canadian research, evidence was found which demonstrates that the Islamophobia industry has infiltrated Canada, finding support within its bordersFootnote 91.

Findings also confirm the role of far-right media outlets in circulating anti-Muslim stereotypes, conspiracy theories, tropes and misinformation to instill fear and division in society. It is important to unravel these links and expose the wider Islamophobia industry as the systemic distribution of these anti-Muslim myths shape public opinion and inform actionsFootnote 92. In 2024, the Canadian government expressed concerns about “reports of divisive, co-ordinated, Islamophobic, and inauthentic information targeting Canadians on social media platforms”Footnote 93. Therefore, efforts to combat Islamophobia must also consider the underlying systems that profit from its organized spread.

Chapter Three: Impacts of Islamophobia

Islamophobia has a multifaceted impact on both individuals and society, affecting various aspects of life, from personal well-being to social cohesion and public policy, including:

- Acts of murder and terrorism: Muslims in Canada and around the world have been subjected to deadly Islamophobic attacks, including the terrorist attack in London, Ontario, in 2021, when a family of five was deliberately run over. Only the youngest family member survived. The attack was described as a “textbook example of terrorist motive and intent” by the Court, marking the first time a white nationalist was convicted of terrorism in Canada. Additional details are found at the end of this sectionFootnote 94.

- Hate crimes: Hate crimes can include targeted acts of violence, harassment, threats, vandalism and cyber hate crimes. These incidents contribute to a climate of fear and insecurity within Muslim communities. Muslim women, especially those who wear the hijab, can be particularly vulnerable to hate. Statistics Canada reported that for all types of hate crimes reported to police between 2010 and 2019, violent incidents targeting Muslim populations were more likely than other types of hate crimes to involve female victimsFootnote 95.

- Discrimination in employment: Muslims may face discrimination in the workplace based on their religious identity. This can include bias in hiring practices, unequal opportunities for career advancement, instances of workplace harassment or a lack of willingness to provide reasonable accommodations for religious practice which is guaranteed by the Canadian Human Rights Act and provincial and territorial human rights lawsFootnote 96.

- Online hate: Muslims may experience online harassment, hate speech and cyberbullying. Social media platforms can become spaces for the spread of anti-Muslim stereotypes, disinformation and misinformation.

- Profiling and surveillance: Muslims may be disproportionately targeted by state-imposed security measures, including racial profiling and surveillance. This can occur in public spaces, airports and in other contextsFootnote 97.

- Discriminatory treatment by state institutions: Various policies by government institutions have at times been implemented with bias, including unconscious bias, in discriminatory ways against Muslims, leading to differential and negative outcomesFootnote 98.

- Discrimination in education: Muslim students may encounter discrimination in educational settings, ranging from microaggressions to overt discrimination like bullying, belittling and exclusion. This can impact their overall academic experience, their progress and advancement and their overall sense of belonging.

- Microaggressions: Muslims may experience everyday microaggressions, such as stereotyping, insensitive comments about their faith or exclusionary behaviour. These forms of Islamophobia can lead to significant distress and a sense of isolation.

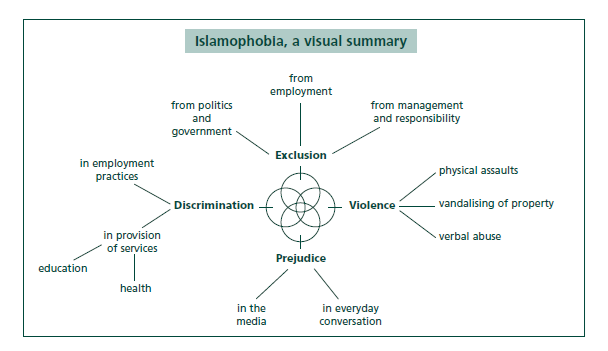

Figure 5: Islamophobia, a visual summary – text version

Image is of a word map that shows the sites that people experience Islamophobia. Exclusion: from politics and government, from employment, from management and responsibility; Discrimination: in employment practices, in provision of services, like health and education; Prejudice: in the media, in everyday conversation; Violence: physical assaults, vandalising of property, verbal abuseFootnote 99.

Terrorism and killings of Muslims

On January 29, 2017, an individual consumed by hatred and fear of Muslims carried out a deadly attack at the Islamic Cultural Centre of Quebec City, killing six men and injuring five othersFootnote 100. Motivated by radical right-wing ideologies, the perpetrator was influenced by white nationalist figures and the fear of Muslims targeting his familyFootnote 101. The devastating attack in Quebec was followed by another episode of mass violence against Canadian Muslim communities with the attack on the Afzaal family in London, Ontario.

On June 6, 2021, a perpetrator deliberately drove a pickup truck into five members of the Afzaal family, fondly remembered today as “Our London Family.” Four members of the family were killed—a grandmother, mother, father and teenage daughter. Their young son survived but was badly injured. The killer admitted to choosing his victims on account of their Muslim faith and was later found guilty on four counts of first-degree murder and one count of attempted murder. The judge in the case concluded it as an act of terrorism, the first verdict of its kind in a case of white nationalismFootnote 102.

Islamophobia and hate crimes

The correlation between Islamophobia, hate crimes and hate incidents is a multifaceted and concerning phenomenon that mirrors more extensive societal views and biases.

Hate crimes are criminal acts motivated by hate, bias or prejudice. They can involve acts of violence, threats or intimidating conduct and damage to property.

A hate crime targeting a Muslim, or someone perceived to be Muslim, or against a property, has occurred if it can be shown that the crime was motivated by hate, bias or prejudice towards Muslims or against Islam.

According to Statistics Canada data, the number of police-reported hate crimes more than doubled (+145 percent) since 2019 with higher numbers of hate crimes targeting a religion or a sexual orientation accounting for the most increase in 2023Footnote 103.

In Canada, segments of the Muslim population can be considered as belonging to a visible minority groupFootnote 104. Specifically, a third of Canadian Muslims are of Arab background, a third of South Asian background, and a third are either from other racialized groups or non-racialized converts to the faith. This suggests that religion works in conjunction with race and ethnicity in motivating hate crimes against Canadian Muslims.

Statistics Canada reported a significant 67 percent average surge in police-reported hate crimes motivated by religion in 2023 compared to the previous year. Those which specifically targeted Muslims rose by 94 percentFootnote 105. However, the lack of intersectionality in the data undermines the accuracy of current hate crime statistics from Statistics Canada, failing to provide a comprehensive depiction of offences against Muslim communities that may be driven by both religious and ethnic biasesFootnote 106. For example, hate crimes targeting Arab or West Asians rose by 52 percent. Hate crimes targeting South Asian communities went up by 35 percentFootnote 107.

The “dark figure” of hate crimes

It is important to note that hate crimes are largely underreported. The unknown number of hate crimes has been described as “the dark figure” of hate crimesFootnote 108. For instance, according to the 2019 General Social Survey published by Statistics Canada, up to 223,000 Canadians reported being a victim of a hate crimeFootnote 109. Studies suggest that only one-fifth of hate crime victims report to the police and they are less likely to report than other victims of crimeFootnote 110. This suggests that the actual number of hate crimes is significantly higherFootnote 111.

Victims could be reluctant to report for a variety of factors, including prior instances of police discrimination, general discomfort with law enforcement, and barriers to reporting, including physically travelling to a police station or unease in asking police to attend at one’s home to take a report. Even when reported, a concerning trend emerges, as police often dismiss many cases as unfounded. They may either disbelieve the victim, question the utility of pursuing the report, or encounter obstacles in their investigationsFootnote 112. The resource, Understanding Anti-Muslim Hate Crimes—Addressing the Security Needs of Muslim Communities: A Practical Guide, developed by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) provides 10 practical steps for both law enforcement agencies and government agencies to help improve trust and provide more robust protectionsFootnote 113.

Figure 6: Security concerns of Muslim communities: Responding to the challenge – 10 practical steps – Text version.

Security is only possible in societies based on mutual respect and equality. The practical steps aim to help governments and everyone working to combat Anti-Muslim hate crime turn policies into action and build tolerant societies for all. The steps are Acknowledge the problem, Raise awareness, Recognize and record bias motivation of anti-Muslim hate crime, Work with Muslim communities to identify security needs, Build trust between national authorities and Muslim communities, Identify security gaps to assess risks and prevent attacks, Provide extra protection to Muslim communities when necessary, Set up crisis response systems, Reassure the community if an attack takes place, and Provide targeted support to victims. To learn more, read ODHIR’s “Understanding Anti-Muslim Hate Crimes – Address the Security Needs of Muslim Communities: A Practical Guide”Footnote 114.

Hate incidents

Hate incidents encompass non-criminal acts driven by detestation or vilification. Hate incidents do not reach the level of criminal conduct, according to the Canadian Criminal Code, and may include verbal harassment, discriminatory practices, or instances of bias that contribute to a culture of fear and alienation for Muslim individuals or communities.

Other cases may be less obvious and require a more nuanced understanding of anti-Muslim stereotypes and codes to detect when they are being applied.

Therefore, strengthening community ties, promoting the reporting of hate crimes and incidents, and holding perpetrators accountable are crucial steps in combatting hate crimes.

Chapter Four: Islamophobia and intersecting identities

Canada’s Muslim communities represent a tapestry of diverse identities, reflecting a rich blend of cultural, ethnic, religious, and linguistic backgrounds. Muslims in Canada come from all around the world, from Morocco in North Africa, through Asia to Southeast Asia and Fiji. Various groups contribute to the country’s unique and vibrant Muslim experience within this mosaic. This diversity also underscores the reality that individuals with intersecting identities may encounter distinct systemic challenges. The term intersectionality, coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, is instructive to acknowledge the ways in which varied and overlapping identities shape individual experience. The Government of Canada’s Anti-Racism Strategy discusses intersectionality as follows:

The Strategy recognizes that people have multiple and diverse identity factors that intersect to shape their perspectives and experiences. In this, it adopts an intersectional approach that acknowledges the ways in which people's experience of racism is shaped by their multiple and overlapping characteristics and social locations. Together, they can produce a unique and distinct experience for that individual or group, for example, creating additional barriers for some and/or opportunities for othersFootnote 115.

In addition, the Government of Canada has been committed to using Gender Based Analysis Plus (GBA Plus) in the development of policies, programs and legislation since 1995Footnote 116. GBA Plus is an intersectional analysis that goes beyond biological (sex) and socio-cultural (gender) differences to consider other factors, such as age, disability, education, ethnicity, economic status, geography (including rurality), language, race, religion, and sexual orientationFootnote 117.

The following sections highlight how intersecting identities can amplify the experiences of bias, discrimination, and hate faced by certain groups. While the examples provided are not exhaustive, the main point is to emphasize the importance of recognizing Muslims as individuals with multiple, intersecting identities, rather than as a monolithic group.

South Asian Muslims

South Asian Muslims in Canada comprise of the largest racialized group among the Muslim population and encounter various stereotypes that stem from biases and misunderstandings. These biases include associating South Asian Muslims with terrorism or extremism, which can lead to unjust suspicion and fear. Other assumptions relate to cultural homogeneity—overlooking the rich diversity within the South Asian community. South Asian Muslims may also face stereotypes related to arranged marriages, perpetuating the misconception that all marriages within the community are arranged without considering individual agency and choice. Stereotypes about arranged marriages can be rooted in cultural practices that are often misapplied to Islam as a whole.

Other stereotypes can relate to educational and economic status and educational attainment, leading to assumptions of either under or overachievement. A 2023 study on the experiences of South Asian Muslims in Canada revealed widespread instances of everyday prejudice and exclusion, with safety—both physical and psychological—identified as the primary concernFootnote 118. Diaspora Muslims from across the Asian continent, as well as Canadians Muslims whose families originate in this region, may also face anti-Asian racism. See Appendix 1 for the definition of anti-Asian racism.

Arabs and Muslims from the Middle East

Individuals of Arab and Middle Eastern descent often encounter Islamophobia influenced by cultural stereotypes perpetuated in the media and exacerbated by geopolitical tensions. Stereotypes about Arabs and Muslims from the Middle East are often rooted in historical, cultural and geopolitical discriminations, create a framework that extends beyond the Arab world and is applied more broadly to Muslims from diverse backgrounds. Many of the stereotypes about Arabs and Muslims from the Middle East, such as assumptions about terrorism, cultural homogeneity or oppressive gender norms, become generalized and perpetuated in the broader discourse about Muslims.

Anti-Palestinian racism (APR) has become a significant term used by Canadian Palestinian organizations and civil society to describe the discrimination faced by Palestinian Canadians, a group of over 45,000 peopleFootnote 119. While many Palestinian Canadians identify as Muslim, they represent a diverse population from different faiths. This form of discrimination extends beyond Palestinians, affecting Arab and Muslim communities as well. Public discourse often unfairly associates Palestinian and Muslim identities with terrorism, leading to harassment, hate crimes, and other negative consequences in schools, workplaces, and communitiesFootnote 120. Advocacy for Palestinian human rights is sometimes viewed through the lens of suspicion, hostility, and incompatibility with national valuesFootnote 121.

APR shares some similarities with Islamophobia but also has distinct characteristics. In Canada, the understanding of APR is growing, with initiatives like the Arab Canadian Lawyers Association’s 2022 framework highlighting its impacts and manifestationsFootnote 122. Some school boards, such as the Thames Valley District and Toronto District School Boards, have also developed, or are in the process of developing their own definitions of anti-Palestinian racism to address this issue and its harmful effectsFootnote 123.

Black Muslims

In 2021, Black Muslims made up approximately 11.6 percent of the total Muslim population in CanadaFootnote 124. The intersection of their racial and religious identities introduces a unique layer to their experiences with Islamophobia. Negative media representations, systemic biases and discriminatory legislation have contributed to the marginalization of Black communities, including Muslims within them. Consequently, Black Muslims may navigate a complex web of anti-Black racism and discrimination, wherein racial prejudices intersect with Islamophobic sentiments, potentially intensifying the challenges they face in areas including employment, education and social integrationFootnote 125. See Appendix 1 for the definition of anti-Black racism.

In 2021, CBC news reported a horrific attack on a Black Muslim woman and her child outside a shopping mall in Edmonton, prompting the family to call for political actionFootnote 126. Soon after this incident, at an Edmonton transit station, a woman attempted to strike a young Black Muslim woman while shouting racial slurs. On New Year’s Day 2022, outside a mosque in Edmonton, a man verbally threatened and attacked a Black Muslim woman in her vehicle, where she was with her childrenFootnote 127. These attacks, combined with the systemic barriers faced by Black Muslims in Canada, have sparked urgent calls to address the rising hate against them.

Indigenous Muslims

Indigenous Muslims, at the intersection of Indigenous and Muslim identities, bring a unique perspective, blending the rich history of Indigenous cultures with the diverse traditions of Islam. According to Statistics Canada data from 2022, of the 1.8 million people in Canada with Indigenous identity, around 1,840 identify as MuslimFootnote 128. While the community remains small, it is growing in visibility and contributes to a greater understanding of the complex ways in which Muslim and Indigenous identities intersect. Indigenous Muslims in Canada face a unique set of challenges. Many navigate the intersection of their Indigenous identity with their Muslim faith, balancing both cultures in a country where Islamophobia and anti-Indigenous racism persist.

This can also include grappling with both the historical injustices and the legacy of colonization faced by Indigenous peoples and the Islamophobia directed at Muslim communities.

Muslim converts

Muslim communities in Canada also include a growing number of converts who have embraced Islam, sometimes described as “reverts.” Their unique journeys contribute to the diverse narratives within Muslim communities, highlighting the inclusive and welcoming nature of Islam in Canada. Converts to Islam may experience Islamophobia for a variety of similar reasons as other Muslims. Additionally, Muslim converts may also experience perceptions they have been radicalized and may pose a security threatFootnote 129, and are sometimes targeted for being informants, alongside potential cultural and familial challenges following their decisionFootnote 130. Recognizing the intersectionality of their identities fosters a more comprehensive approach to supporting this diverse group.

2SLGBTQI+ Muslims

Canada’s Muslim population encompasses individuals who are both Muslim and queer. 2SLGBTQI+ Muslims navigate intersecting forms of discrimination based on both sexual orientation, gender identity and religious identity. They can suffer specific compounding exclusions of homophobia, transphobia, racism and IslamophobiaFootnote 131.

Muslim youth

Around 25 percent of Muslim Canadians are below the age of 15, and around 50 percent are below the age of 35Footnote 132. Therefore, Muslim youth make up a significant segment of the Canadian Muslim population and may encounter challenges as they navigate their identities in a multicultural society. The intersection of age and religious identity, along with other identities, call for initiatives that empower and support Muslim youth. Schools, colleges and universities can incorporate anti-Islamophobia initiatives and strategies to promote inclusion and equity. Several school boards and at least one provincial government have committed to providing anti-Islamophobia resources and/or have developed board-wide strategies. Furthermore, initiatives that promote belonging, civic engagement, and the mental health of young people are also instrumental towards building resilience and fostering social cohesion.

Figure 7: The cover of the Thames Valley District School board’s magazine, “Equity,” – Text version

The cover of the Thames Valley District School board’s magazine, “Equity,” which has the words, “Dismantling Anti-Muslim Racism Strategy,” with a photo of a young Muslim woman wearing glasses in a maroon headscarf. Photo credit: Amira ElghawabyFootnote 133

Muslim women

Muslim women’s experiences of Islamophobia are shaped by the intersection of their gender and religious identities, giving rise to what is often referred to as “gendered Islamophobia.”Footnote 134 This form of discrimination stereotypes Muslim women as oppressed victims of a barbaric patriarchy, ignoring their agency and autonomyFootnote 135. These harmful perceptions contribute to social, economic, psychological, and physical harm, as Muslim women face discrimination and violence simply because of their visible religious identityFootnote 136.

The visibility of Muslim women, particularly those who wear the hijab or traditional clothing like the shalwar kameez, often attracts unwanted attention and can lead to harassment, exclusion, and violence. High-profile incidents, such as the hate-motivated knife attack on two sisters in Edmonton and the tragic killing of a Muslim family in London, Ontario, highlight the physical dangers Muslim women faceFootnote 137. They also experience discrimination in other areas, such as workplace bans on wearing the hijab or niqab, or restrictions like the federal government’s previous ban on wearing a niqab during citizenship oaths, which sparked significant legal debateFootnote 138. The Federal Court ultimately struck down the ban, but ongoing legal discussions, such as Quebec’s restrictions on religious symbols in public institutions, continue to affect the rights and freedoms of visibly Muslim women and other religious minoritiesFootnote 139.

Muslims living with disabilities

Muslims living with disabilities face not only physical and social barriers related to their disabilities, but also cultural, religious, and racial biases linked to their Muslim identity. For Muslims living with disabilities, this intersection of disability and Muslim identity can lead to heightened discrimination, exclusion, and marginalization in both the broader society and within the Muslim community itself. For instance, the presence of accessibility issues in mosques or religious spaces, coupled with a lack of understanding or support for their religious practices, can hinder the full participation of Canadian Muslims living with disabilities in spiritual and community activitiesFootnote 140.

Muslim immigrants, newcomers & refugees

Understanding the intersection of religion and immigration status is important. A significant proportion (19 percent) of immigrants admitted from 2011 to 2021 reported being MuslimFootnote 141. This has the potential of compounding challenges already faced by Muslims, specifically regarding economic status and mobility. According to 2022 data, the poverty rate was higher for immigrants aged 15 years and older (10.7 percent), particularly recent (14 percent) and very recent immigrants (16.4 percent) in this age group, than persons born in Canada aged 15 years and older (8.6)Footnote 142.

The recent rise in anti-immigrant sentiment across Canada and the US, especially against those who are racialized, also includes Islamophobic rhetoricFootnote 143. Ultimately, the intersections of Islamophobia, anti-immigrant sentiment, and anti-Palestinian racism creates a toxic environment in which individuals are marginalized not just for one aspect of their identity, but for the multiple ways they are racialized or othered, particularly while exercising civil liberties, including those of free expression and assembly.

Chapter Five: Navigating media narratives and stereotypes

Much of what is known about Islam and Muslims in Western societies is derived through media sources and Hollywood.

The overrepresentation of Muslims in narratives about terrorism has been a persistent and concerning trend in media portrayalsFootnote 144. In a study of over 900 Hollywood films, Muslim or Arab men were often represented as terrorists or “stock villains.”Footnote 145 A few media examples demonstrate this phenomenon which transcends borders, reaching audiences throughout the West. A study released in 2018 by the Washington-based Institute for Social Policy and Understanding found that between 2002 and 2015, the New York Times and the Washington Post gave, on average, 770 percent more coverage to foiled cases of ideologically motivated violence involving Muslim perpetrators than similar cases involving non-Muslim perpetratorsFootnote 146.

Between 2008 and 2012, 81 percent of stories about terrorism on 146 network and cable news programs in the United States were about Muslims, while only six percent of domestic terrorism suspects were actually Muslim, leading to a clear over-representation of Muslims as terroristsFootnote 147. Over a 25-year span, Islam garnered more negative headlines in the New York Times than cocaine, cancer and alcohol, according to Canadian researchersFootnote 148. Muslims are constantly under scrutiny, the subject of persistent divisive political rhetoric and fearmongering.

In addition, the findings of the Canadian Association of Journalists’ survey on newsrooms underscore a pressing issue in the form of a significant lack of diverse representation within Canada’s media outlets. The underrepresentation of diverse voices in newsrooms perpetuates a notable disparity between the composition of news teams and the diversity of the Canadian populationFootnote 149. This disconnect has repercussions. It limits the range of perspectives and narratives covered in news reporting, resulting in a less comprehensive and inclusive understanding of the issues that impact diverse communitiesFootnote 150.

Social media and Islamophobia

Social media platforms such as Facebook, X (formerly known as Twitter), YouTube and Instagram, among many others, have become integral facets of modern life, shaping trends and captivating usersFootnote 151.

However, with this evolution comes certain dangers: the rise of Islamophobic hate speech on social mediaFootnote 152. This phenomenon poses a growing concern, manifesting in ways that inflict harm on victims, breed fear and exclusion within communities, poison public discourse. It can even incite extremist, hateful and deadly acts.

While the study of social media and its impact on Islamophobia is still an understudied area in Canada, recent research in Europe serves as a stark warningFootnote 153. Far-right groups exploit these digital spaces, employing disinformation and manipulation tactics to vilify Muslims and their faith. Researchers have shed light on the insidious nature of “cloaked” Facebook pages, revealing how individuals or groups feign radical Islamism to sow antipathy against Muslims, successfully inciting anger toward broader Muslim communitiesFootnote 154.

Several online far-right media channels have also appeared or grown in Canada in the recent years with substantial viewership that target Islamophobic and anti-immigrant sentiments, while perpetuating misinformation and hate. For example, in 2017, a far-right media source posted lamenting that the white population of Canada is being “replaced” by immigrants, particularly from Muslim-majority countriesFootnote 155. The consequences of exposure to Islamophobic messages are profound. Sociological studies indicate that portrayals of Muslims as terrorists can fuel support for civil restrictions on Muslims and endorse military actions against Muslim-majority countriesFootnote 156 and have led to the self-radicalization of individuals who would go on to kill Muslims in Canada and beyondFootnote 157. The role of social media in perpetuating Islamophobia demands scrutiny and awareness, as social media is a powerful force in shaping perceptions and attitudes, influencing policy decisions and potentially leading to deadly violence.

Empowering Muslims to tell their own stories

The relative ease with which people can broadcast their experiences, views and interests means that a more representative range of narratives is more widely available than ever before. Furthermore, a growing number of Muslim filmmakers, journalists, artists, authors, comedians and creative producers are excelling in their fields. They are challenging unidimensional portrayals and telling stories that are both universal and yet also deeply rooted within their own cultural and religious communitiesFootnote 158. Mainstream culture and media provide an important avenue to counter Islamophobia while demonstrating the presence and vibrancy of Muslim communities. More and more Canadian Muslim creatives are stepping up, as are institutional efforts to document the vibrant history of Muslims in CanadaFootnote 159. A commitment to diverse school curricula and university courses, along with community arts programming, will help ensure more Canadians have access to such offeringsFootnote 160.

Chapter Six: Strategies for Combatting Islamophobia