Pre-1920: From punishment to penance

Harsh beginnings

Canada became a country in 1867 with Confederation, but its history of corrections goes back much farther. In the early days, the system was truly one of crime and punishment: people who broke the law suffered harsh consequences, often in public. They could be whipped (called 'flogging') or branded (marked on the skin with burning hot metal); they could be put in pillories (wooden frames with holes for an offender's head and arms) or stocks (wooden frames with holes for an offender's arms and legs) and made to stand for hours or days on display out in the open. Other times, convicts were simply sent away, transported or banished to other countries and left to fend for themselves.

Changing attitudes

Toward the end of the 19th century, new ideas about corrections began to take shape in England and, a little later on, the United States. These eventually took root in Canada as well. One of the most important was the concept of penitentiary houses: places where convicts could be kept away from other members of society, but where they could have a chance to think about their actions and-hopefully-reform their behaviour. The "Provincial Penitentiary of Upper Canada" at Kingston, Ontario was Canada's first institution of this kind, taking its first six inmates on June 1, 1835. Others soon followed: at Saint John, New Brunswick in 1841 and Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1844. These, along with Kingston, would become Canada's first federal penitentiaries after Confederation. (Federal penitentiaries are run by the federal government and house offenders whose sentences are longer than two years. Sentences of less than two years are served in provincial penitentiaries.)

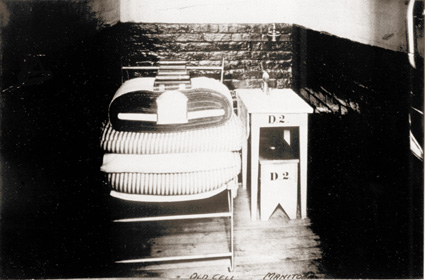

Several new federal penitentiaries were built between Confederation and 1920: St. Vincent de Paul in Quebec; Manitoba (now Stony Mountain Institute); British Columbia; Dorchester in New Brunswick; Alberta; and Saskatchewan.

Asylums and penitientaries

Asylums developed at the same time as Canada's penitentiaries. In 1865, the government of Upper Canada opened Rockwood Hospital next door to Kingston Penitentiary and transferred mentally ill inmates there. Within 12 years, Rockwood became a provincial asylum, and the few remaining offenders there were transferred back to the penitentiary. Diagnosing people as mentally ill was extremely haphazard for many years. Some wardens and inspectors estimated that between 15 and 25 per cent of Kingston's inmates were insane; in the 1940s, many psychiatrists suggested that all criminals were insane and that prisons should be converted into psychiatric hospitals. For decades, the criminally insane were handed off between prison cells, infirmary beds, and provincial asylums until after the Second World War—confined, but not treated.

A nation is built

It was a time of coming together and a time of reaching out. A time when the vision of what Canada might be started to become reality. Upper and Lower Canada united. Queen Victoria named Ottawa the capital of Canada in 1857—a diplomatic choice halfway between Montreal and Kingston, the two major centres at the time. And, on July 1, 1867, the British North America Act was signed at Charlottetown—joining Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec and Ontario together as the Dominion of Canada.

Railroads soon became the lifelines of the country, extending eastward into the Maritimes and, by 1885, west to British Columbia. (BC joined the Canadian Confederation in 1871.) Shortly after the turn of the century, those railroads carried immigrant settlers into the Prairies, and by 1905 Canada had two new provinces: Saskatchewan and Alberta.

A nation is called

With the dawn of the new century came the dawn of new possibilities. Guglielmo Marconi received the first Transatlantic radio message at St. John's, Newfoundland in 1901, ushering in the age of telecommunications. Yet not all advancements were as sound as they promised to be: the 'unsinkable' ship Titanic, for example, struck an iceberg off the Newfoundland coast in 1912 and vanished into the Atlantic.

Then came 1914, when events in Europe prompted England to declare war on Germany—and Canada plunged without hesitation into the conflict. During the war years (1914-1918), the worst accident in Canadian history occurred: the explosion of a French munitions ship in Halifax harbour, killing 2,000 people on December 6, 1917. The war was harder and longer than anyone expected. As a way of supporting the war effort, Canada's federal government introduced a temporary money-raising measure: income tax.

Seeking to win the federal election of 1918, Prime Minister Robert Borden created the Wartime Elections Act, which for the first time granted women the right to vote. To be eligible, a woman had to be a British subject 21 years of age or older and also the wife, widow, mother, sister or daughter of any male or female who served in Canada's military forces.

The human factor

The opening of Kingston Penitentiary in 1835 marked the beginning of a new age in Canadian corrections—one in which the notion of a principled, truly institutional approach was undertaken for the first time.

Yet change did not come overnight. For many years, prisons remained cruel and unhealthy places. Prisoners' food rations were often restricted to bread and water as a 'punishment diet'. Convicts were prohibited from speaking to, looking at or gesturing toward other inmates. Cells were small and ill-equipped. And the guards and keepers who operated the facilities had no formal training. In its early years, the penitentiary was something of a tourist attraction, charging admission to visitors such as Charles Dickens, who described it as "well and wisely governed." However, Dickens and the rest of the public were deceived. Despite having been designed with the best intentions, the penitentiary was a place of violence and oppression.

At the root of its problems in the early years was its first warden, Henry Smith. Smith's use of flogging, even in an age when it was an accepted form of discipline, was flagrant. Women and children as young as eight were flogged. As well, Smith punished inmates with shackling, solitary confinement, bread-and-water diets, darkened cells, submersion in water, 35-pound yokes, and imprisonment in "the box," an upright coffin. In 1848, George Brown, a member of parliament, led an investigation that uncovered Warden Smith's abuses. Brown produced a 300-page document citing 11 criminal charges and 121 counts. Smith was suspended and later—after 14 years as Warden—dismissed by Governor General Lord Elgin.

Advocates for change

Even as the conditions of prison life in Canada were starting to be called into question, groups began to emerge with concerns about life after prison. Specifically, the Prisoners' Aid Association of Toronto—organized in the 1870s—argued that without support to find work, lodging, food and clothes, many ex-convicts who had served their sentences were likely to end up back in jail.

The efforts of the Association led to Canada's first penal convention in 1891, where topics such as the segregation of male and female inmates, special tribunals for juvenile offenders, systematic reform of Canada's correctional systems and parole were discussed.

These issues became recurrent topics of Royal Commission reports over the ensuing decades, and some were acted upon in the years leading up to 1920: with the establishment of the Ticket of Leave act in 1899 and the Dominion Parole Office in 1905.

After you've had a chance to explore Canada's correctional history, let's see what made an impression!