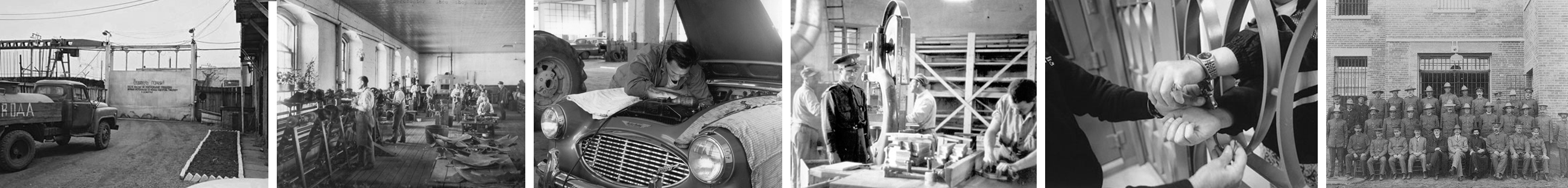

1920 to 1939: Through adversity

A system under scrutiny

Throughout the early part of the 20th century, increasing attention was paid to Canada's penitentiary system. More groups became involved in the prisons, and governments looked for ways to improve conditions and find more effective ways to rehabilitate offenders.

At the start of the 1920s, the Biggar-Nickle-Draper Committee, appointed through the Department of Justice, suggested several changes to penitentiary regulations-changes that were considered quite radical in some quarters. For example, the Committee proposed that prisoners be paid meagre wages for their work (which ranged from breaking rocks, quarrying and stonecutting to farming, metalwork, carpentry, tailoring and brick-making.) It suggested that prison libraries and educational facilities should be improved; and that inmates should be confined less often to their cells.

A society under stress

The Great Depression that began in 1929 placed terrific strains on Canadians. More than a quarter of all working people had lost their jobs by 1933. Families lost their comforts, their belongings—even their homes. Not surprisingly, in such desperate times, the crime rate rose and Canada's prisons saw an influx of new offenders.

And yet a spirit of compassion persisted. In addition to the efforts of groups like the Prisoners' Aid Association and the Salvation Army (which had been operating in Canadian prisons since 1882), a new organization emerged to help rehabilitate and reintegrate convicts: the John Howard Society, founded by Reverend J. Dinnage Hobden and named after the famous British prison reformer of the 19th century. Its creation was followed in 1939 by the first Canadian branch of the Elizabeth Fry Society for women inmates, named for another British prison reformer and advocate of inmates' rights.

A vision of change

Toward the end of the 1930's came further calls for prison reform. Canada's first women's prison had opened in Kingston in 1934, answering a long-called for need to separate male and female inmates.

In 1936, a Royal Commission was struck to examine the penitentiary system in a comprehensive way. Its report, the Archambault Report, was released in 1938. Its many recommendations contributed to the creation of a revised Penitentiary Act. But events on the world stage would postpone those changes from being acted on for many years.

High times, low times

The 1920s were prosperous years for Canada and Canadians. Wages were up, unemployment was down and memories of the First World War were slowly being left behind.

The stock market crash of October 1929 changed all that overnight. Many factors contributed to the fall: slowing economies, over-valued companies, too little regulation of financial practices and affairs. Whatever the causes, the impact was huge—and long-lasting. Only by the end of the 1930s did countries really shake off the effects. And the years of Depression in between were hard ones for all.

Challenging years

During the Great Depression, the value of goods dropped incredibly—making it hard for companies to generate profits and hard for workers to earn a decent living, especially in commodity-based sectors such as farming, mining and logging. The numbers make it clear: In 1929, companies reported profits of $396 million. In 1933, the total was a loss of $98 million.

1933 was the turnaround year, actually; things slowly started to improve after then. But a full recovery would not come until the end of the decade.

During the 1930s, in response to the widespread suffering and want caused by the Depression, the government began to create programs like Medicare and unemployment insurance to provide what has come to be known as a 'social safety net'.

The Archambault Report

While prison populations grew during the Depression, there was little money available to expand existing facilities or open new ones. Some construction went on, but even so, overcrowding created significant tensions. And these, eventually, erupted in the form of full-scale riots. The first occurred at Kingston in 1932, and lasted six days. Fifteen others took place in penitentiaries across the country between then and 1937.

It was clear that something had to be done, and Agnes Macphail, Canada's first female elected Member of Parliament, had many thoughts on the matter. She had become a strong advocate of change to Canada's prison system since taking office in 1922.

Her ideas included creating an independent parole board, and making the option of parole available to all offenders. After a change of government in 1935, a Royal Commission was established to look into the topic of Canada's penitentiaries.

From every angle

The Royal Commission—called the Archambault Commission after the man who led it, Mr. Justice Joseph Archambault—made a careful examination of virtually every aspect of Canada's corrections system.

It issued a thorough and substantial report in 1938, and in its findings confirmed much of what Agnes Macphail had been saying for years with respect to prison conditions and the importance of parole.

A key finding of the report was that more than 70 percent of inmates were repeat offenders; a figure that all involved felt could be brought down with more effective efforts to rehabilitate convicts.

In the end, Archambault and his colleagues called for a prison commission with real and complete authority over the management of penitentiaries—and the ability to act as an independent federal parole board.

The world intrudes

While there was much debate over how much of the Archambault report's recommendations should be implemented, and while shortly after its issue a revised Penitentiary Act was drafted, the change that was so imminent did not occur due to the outbreak of the Second World War.

After you've had a chance to explore Canada's correctional history, let's see what made an impression!