Chapter 2 – The Purpose and Composition of Professions

Section 2.1 – What is a Profession?

This chapter will describe the idea of a profession, examining the purpose and composition of this important type of organization. It will begin by describing a profession as a system and define its major terms and concepts.Footnote 27 These terms and concepts will then be used in subsequent chapters to explore a very specific profession: the Profession of Arms.

A profession is considered an exclusive group of people who possess and apply a systematically acquired body of knowledge, skills, abilities and other attributes (KSAO) derived from extensive research, education, training and experience. For a profession to have meaning, it must exist within a broader society and, as a result, the actions of the profession will have a direct impact on the status of that profession within society.Footnote 28 Professionals are the members of a profession. They have a responsibility to fulfill their professional function ethically and competently for the benefit of society. Professionals are governed by a code of ethics that establishes standards of conduct within their profession. Members actively uphold and enforce this code of ethics that encapsulates values widely acknowledged and deemed legitimate by society. Professionalism is the conduct and performance expected of a professional. This means abiding by a set of recognized standards and practices related to the profession’s specific body of knowledge.Footnote 29 Members of the profession actively innovate, expand and improve upon their KSAOs.

Section 2.2 – Fundamental Imperatives

A profession is generally overseen by external governing bodies that provide its legitimate jurisdiction to practice the said profession. These governing bodies also provide regulatory and accountability frameworks that assess the credibility and trustworthiness of the profession to fulfill its function; in short, its professional effectiveness. Professions must therefore fulfill two fundamental imperatives to ensure their credibility and trustworthiness to society. Both imperatives are of equal importance to the relevance and effective functioning of the profession.

The societal imperative demands that the profession submit to a governing body that determines and oversees the legitimate jurisdiction of the profession and its regulatory compliance. The second aspect of the societal imperative is that to serve its society well, the profession must reflect - to the greatest degree possible but without compromising its primary function - the values and norms of the society that it serves. In essence, this means that the professionals must perform their function in line with the laws, values, virtues and norms that represent the best aspirations of society.

The functional imperative demands that the profession be effective in fulfilling its primary function, whether that be delivering a service or product. Governing bodies generally allow professions a high degree of control and self-regulation over their internal matters to ensure that their profession is functioning effectively. For example, these can include decisions related to doctrine, the professional development of its members, discipline, technical matters, administration, personnel policy and the internal organization of the profession itself. Oversight is maintained by an external governing body to periodically assess the effectiveness of the profession on behalf of society.

The functional imperative demands a specialization of knowledge, skills and abilities across society which, history has shown, allows society to flourish.Footnote 30

Section 2.3 – Professional Attributes

Generally, a profession comprises four attributes, as illustrated in Figure 2.1: responsibility, expertise, ethos or code of values and ethics, and identity. Responsibility represents the assigned role, function and legitimate boundaries that define the profession. Expertise represents the profession’s systematically acquired body of KSAOs and its capacity to apply them competently. An ethos or code of ethics governs how that expertise is to be used in a positive manner that is relevant and beneficial to society. A practitioner takes on a professional identity by fulfilling their responsibilities to their highest degree of expertise in a manner that aligns with the ethos or code of ethics. Combined with expertise, this forms the professional ideology that guides the profession’s standards of conduct and performance; in essence, the standards of professionalism.

Figure 2.1: The Professional Construct

Government Direction and Control

Long description

The graphic portrays the professional attributes of identity, expertise, and responsibility forming the sides of an isosceles triangle, with ethos in the centre as the binding attribute. Government direction and control is shown undergirding the professional attribute of responsibility at the base of the triangle.

Section 2.4 – Professions and Trust

The relationships between society, professions and their governing bodies are founded on trust. The perceived trustworthiness of the profession is predicated upon its credibility in delivering its service or product. Does the profession do so in an ethical manner? Does the profession truly have expertise in the area for which it is providing that service? Does the profession have the capability to provide the service to the required standard and scale? Whereas the boundaries of a profession are generally well-defined, they are not impermeable, and hence the profession is influenced by changes within society.

Ultimately, a profession’s worth is its ability to ensure trustworthiness in the fulfilment of its service to society. Where we understand trust to mean the confidence that someone will act in another’s best interest, trustworthiness is the demonstration of the capacity to act in another’s best interest; that is, for professionals to act in the best interest of society.Footnote 31 Research has demonstrated that trustworthiness is best generated through the application of three variables: character, competence and commitment.

Figure 2.2 The Development of Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness = (Character + Competence) x Commitment

Long description

The graphic portrays the professional attributes of identity, expertise, and responsibility forming the sides of an isosceles triangle, with ethos in the centre as the binding attribute. Government direction and control is shown undergirding the professional attribute of responsibility at the base of the triangle.

Trustworthiness, as the formula illustrates in Figure 2.2, is the product of commitment amplifying the sum of character and competence. Character (who you are) and competence (what you do and how well you do it) are additive. Critically, one’s commitment is a force multiplier towards building trustworthiness, towards success.Footnote 32 Research and experience inform us that commitment is multiplicative because, while talent is important, effort counts twice as much towards success. Passion and perseverance are necessary to sustain the levels of ambition, engagement and personal sacrifice that commitment requires.Footnote 33 Trustworthiness allows professions to work within an intent and a values-based approach in an effective, and efficient manner. Trustworthiness enhances both efficiency and effectiveness so that a profession can operate with less friction, at the proverbial speed of trust.Footnote 34

Character

Character, the first variable in the equation, stems from antiquity (to include many Western, Eastern and Indigenous cultures) into today. The concept of character in North America can be found within Indigenous virtues. Several sources suggest that Seven Sacred Teachings - Niizhwaaswi Gagiikwewin – as a set of virtues created and accepted by many First Nations and Métis peoples.Footnote 35 The Seven Sacred Teachings of love, humility, respect, truth, honesty, wisdom and courage are at the heart of many Indigenous cultures.

Inuit have a unique articulation of virtues called the Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ). IQ is an Inuit way of knowing that translates into English as “traditional Inuit knowledge.”Footnote 36 Alternatively, it has been translated to mean “that which Inuit have always known to be true.”Footnote 37 IQ has a framework to clarify ways of knowing Inuit culture that help Inuit apply their traditional knowledge based on six principles. These six principles translate to service, consensus, collaboration, knowledge, stewardship and resourcefulness.Footnote 38 In turn, these principles are supported by Maligait, which provides a way in which to live a good life. Maligait’s four laws include working for the common good, respecting living things, maintaining harmony and balance, and planning and preparing for the future.Footnote 39 Parallels to the Seven Sacred Teachings are obvious.

Within Western cultures, the Values in Action (VIA) Institute on Character's universal virtues and character strengths are similar to Indigenous virtues and principles. Character is largely described as a combination of values, virtues and individual traits that are internalized and lived. Prominent within the field is the work of Christopher Peterson and Martin Seligman who created the VIA Classification of Character Strengths and Virtues. Offered as a tool through which to identify, measure and develop character, the VIA classification offers twenty-four character strengths that support the six core virtues of wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, temperance and transcendence.Footnote 40 This foundational research forms a set of universal virtues and character strengths that transcend ethnicity, culture, religion and time.

More recently, Western University academics have adapted the VIA research to a leader character model comprising eleven character dimensions supported by sixty-two character elements. Centered on the character dimension of judgement, the ten other dimensions include transcendence, drive, collaboration, humanity, humility, integrity, temperance, justice, accountability, and courage. These interdependent character dimensions interact with each other to form the character variables that are activated by and inform judgement. The purpose of this practical leader character model is to ensure team well-being and sustain excellence through better judgement informed by character.Footnote 41

The concept of character closely tracks with the societal imperative. The values and virtues that professions must adopt to ensure their relevance and trustworthiness to society should be the best values, virtues and traits that their societies aspire to be. In short, professionals need to reflect and remain obedient to the best of the value system that they are sworn to protect.

Competence

The second variable in the trustworthiness equation, competence, relates to the professional expectations that support the core purpose of the profession. The competence of a profession is determined by the quality and degree to which the professional KSAOs are performed in service to society. Professional competence is varied, from technical skills, procedural abilities, new innovative knowledge, to the organization of the profession itself. Such competence is acquired through continuous research, education and training along with the accumulation of experience in applying such knowledge. Moreover, the principles guiding the acquisition and application of this knowledge are codified within doctrine, professional discourse, policies and procedures within professions.

Commitment

While most aspects of character and all aspects of competence are captured by KSAOs, it is the vitality of one’s commitment – as the third variable in the equation – to pursue excellence in character and competence that achieves the trust inherent in professionalism. Talent is simply not enough; commitment, or persistence of effort, is the overriding ingredient needed to ensure that character and competence are pursued towards the trust necessary for success. Commitment can be expressed as the sum of ambition, engagement and sacrifice to ensure success. This combination of elements creates trustworthy organizations that thrive and succeed.

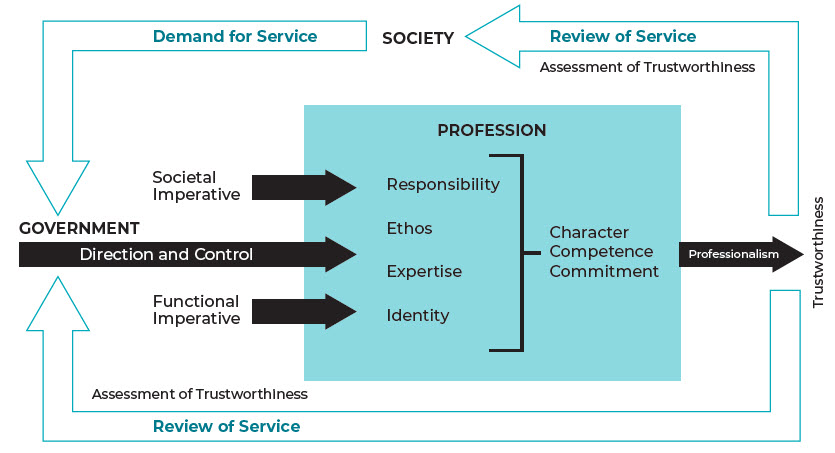

These elements can be seen in relation to each other in Figure 2.3 which is a simplified depiction of the profession as a system and the context within which it operates.

Figure 2.3 The Professional System

Long description

The graphic portrays the profession being directed and controlled by government informed by the societal and the functional imperatives in the form of bold arrows. The profession is in turn influenced by its professional attributes in terms of responsibility, ethos, expertise and identity, which the profession delivers in terms of character, competence and commitment to deliver its service with professionalism, depicted as an output arrow. This professionalism generates trustworthiness, which is in turn, assessed by both society and government in their respective reviews of the profession’s service, which then results in a demand from society to government for professional service. The system comes full circle as a flow diagram with government providing direction and control of the profession.

Section 2.5 – Types of Professions and Professionals

Professions can take a variety of forms. Professions are commonly known as associational professions whereby a member of the profession works individually to serve their clients. The medical and legal professions are normally considered associational. A collective profession is quite different from an associational profession. In a collective profession, the service or product cannot be performed or produced by an individual.Footnote 42 The professional service is only able to be performed by a collective group of professionals.

Dual professionals are professionals who hold professional status in more than one profession, simultaneously. Dual professionals may be regulated by both professional bodies. For example, an associational professional may bring unique expertise to a collective profession and be a member of both.

Section 2.6 – Conclusion

This chapter presented a conceptual framework for the profession centred on the pivotal concept of trust. Trust within a profession is both a requirement and a product of a profession meeting both its functional and societal imperatives. The trust bestowed upon a profession must be earned every day as trustworthiness. This trust can be eroded when members of the profession fall short of meeting the expectations embodied in the professional attributes, but in particular, the professional ideology.

In the chapters that follow, this framework of trust, imperatives, and attributes will be applied to military professionals - members of the profession of arms. It will chart the path to ensuring the profession of arms remains capable of defending Canada and Canadian interests and doing so in a manner that maintains the CAF’s position within society as a respected and vital profession.