Chapter 6: Fundamentally rethinking the regulatory oversight pillar

Official title: A Transformative Framework to Achieve and Sustain Employment Equity - Report of the Employment Equity Act Review Task Force: Chapter 6

Author: Professor Adelle Blackett, FRSC, Ad E, Task Force Chair

On this page

- Introduction: Regulatory oversight is in need of fundamental repair

- Where we are

- The one-stop shop: Fundamentally rethinking oversight

- Institutional architecture

- Special programs: A role for the Employment Equity Commissioner

- Harmonizing equity frameworks

- Oversight through employment equity leadership at the top

Introduction: Regulatory oversight needs fundamental repair

Employment equity is perceived to be about reports and not about advancing and progress.

The success of a human rights enforcement system can ultimately be measured by one test - does the system lead to measurable and real reduction in the discrimination faced by citizens protected by the law.

Workplaces should have significant latitude to promote equitable inclusion, reasonable latitude on how to implement employment equity, and no latitude to drag their feet on achieving and sustaining employment equity.

As we looked closely at the regulatory oversight and accountability measures in place for the Employment Equity Act framework, our task force came away with the concern that the existing legislation, like some other employment law frameworks, might, in the words of political scientist Leah Vosko, “inadvertently incentivize non-compliance.”Footnote 1

The current Employment Equity Act framework might be incentivizing foot dragging, not providing enough guidance to implement, and putting a brake on the creativity necessary to exceed unduly rigid indicators and achieve a barrier free workplace for all.

We have said it before: for employment equity to mean achieving substantive equality, the implementation through barrier removal, meaningful consultations and regulatory oversight must be proactive too. And the failure to implement and to engage in meaningful consultations must entail consequences.

Professor Vosko’s work on employment standards legislation has led her to question the reliance on a mix of “new governance” strategies that privilege persuasion and information sharing without enough attention placed on deterrence.Footnote 2 We took note as well of the many stakeholders who told us that we need to focus on ensuring that the Employment Equity Act framework is actually enforced. There was lost confidence in the ability of individual human rights complaints and individual grievances to resolve these systemic questions.

We reviewed decisions raising employment equity concerns rendered by the Federal Public Service Labour Relations and Employment Board in response to employee complaints of “abuse of authority” under Section 77(1)(a) of the Public Service Employment Act. These decisions confirm the challenge of fitting systemic complaints into individual cases. The review similarly suggests how important it is for adjudicators to have specialized expertise and training in equity. The chair of the Board, Edith Bramwell and general counsel Asha Kurian, also stressed the importance of a holistic approach to addressing employment equity.Footnote 3

We need hospitals, of course. But we heard an urgent plea for us to focus on proactive prevention and care. Regulatory oversight must be nimble, supportive and sustained.

We have a framework that seeks to stimulate change through implementation via self-evaluation and reporting, through meaningful consultations and regulatory oversight. It is well designed to do so, so long as each of the pillars is fortified.

But we have all the evidence we need to affirm that we cannot achieve employment equity if even one of the pillars is weak. And while we have provided recommendations to strengthen implementation and meaningful consultations, it is clear that the regulatory oversight pillar is broken, and in need of quite fundamental repair.

Without sufficiently robust regulatory oversight, workplaces lose all three key reasons why they might seek to comply with the Employment Equity Act, namely:

- economic—it costs less to comply than to risk fines and penalties

- social—they do not want to be unfavorably compared to others in their industry, and

- normative—they believe it is the right thing to doFootnote 4

Our current approach to regulatory oversight misses all three reasons. The Employment Equity Act framework offers:

- very little by way of economic incentive

- limited visibility to employers who are doing well in the industry and little objective basis for comparison, and

- insufficient guidance to employers who want to do the right thing by fostering equitable inclusion on how to do so

This chapter canvasses where we are on regulatory oversight, and offers recommendations on where we need to go.

Where we are:

The role of the Labour Program

The Minister of Labour, largely through the Labour Program’s Workplace Equity Division, is responsible for the administration of the Employment Equity Act. It is called upon it to:

- develop and conduct information programs to foster public understanding the Employment Equity Act and foster public recognition of its purposeFootnote 5

- undertake research related to the purpose of the Employment Equity ActFootnote 6

- promote the purpose of the Employment Equity ActFootnote 7

- publish and distribute information, guidelines and advice to private sector employers and employee representatives regarding the implementation of employment equityFootnote 8

- develop and conduct programs to recognize private sector employers and employee representatives for outstanding achievement in implementing employment equityFootnote 9

- issue penalties to private sector employers for non-compliance with the Employment Equity ActFootnote 10

- submit an Annual Report to Parliament on the status of employment equity in the federally regulated private sectorFootnote 11

- make available to employers any relevant labour market information respecting designated groups in the Canadian workforce in order to assist employers in fulfilling their obligations under the Employment Equity ActFootnote 12, and

- administer the Federal Contractors Program (FCP)Footnote 13

The Labour Program also administers the WORBE program discussed in Chapter 5, alongside an Employment Equity Achievement Awards program.

Employment Equity Achievement Awards Program:

The Employment Equity Achievement Awards Program has honoured awardees from the Legislated Employment Equity Program or the Federal Contractors Program since 2016 for

- Outstanding commitment to employment equity

- Innovation

- Sector distinction

- Employment equity champion

The awards program was paused for two years during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is set to relaunch at a ceremony in 2023, and is to include a new Indigenous Reconciliation award.

The awards program is administered by the Labour Program.

Based on the announcements, quite a number of the awards may reflect commitment to diversity and inclusion, or the launching of initiatives or programs aimed at increasing representation.

Some others reflect innovative, promising practices, such as working through memoranda of agreement with Indigenous communities to advertise, assess and assist with the hiring of Indigenous candidates.

The publicly shared information on the awards program have tended not to provide specific detail on the results of the promising practices, or whether and how recipients have successfully implemented employment equity in keeping with the current requirements of the Employment Equity Act framework.

The Labour Program’s limited means:

The Labour Program’s responsibilities and powers are broad. The capacity and results have been less so.

Consider that only 4 employers have ever received a notice of assessment of a monetary penalty. The last penalty was issued in 1991, which is also when the largest penalty was issued - $3,000.00. Under the FCP, no contractor has been found to be in non-compliance since the 2013 redesign.Footnote 14

This is despite the fact that the Labour Program conducts compliance assessments annually for federally regulated private sector employers. For the FCP, the Labour Program conducts individual compliance assessments the year after the contract award date, then every three years afterward.

There are built-in limits in the Employment Equity Act framework, explored throughout this report, that affect what the Labour Program can do. The point of the Employment Equity Act framework should have been to create incentives for employers to comply wherever possible.

If we knew that employment equity was actually being achieved and sustained, the limited assessments of penalties would be something to celebrate. But that is far from the reality.

Consider that currently, when a compliance officer in the Labour Program finds that an employer is not meeting an undertaking – for example, the employer has failed to review and revise its employment equity plan as required by Section 13 of the Employment Equity Act, or has failed to consult with employee representatives as required by Section 15 – the compliance officer is required to notify the employer and “attempt to negotiate a written undertaking.”Footnote 15 That’s it.

Consider also that Workplace Equity Officers used to be available across Canada, working out of regional offices, and close to the workplace actors themselves. They were able to undertake on-site visits to FCP contractors. The positions were eliminated in 2013. Compliance assessments are now based on reporting rather than on-site visits. While there is a lot that can be done with virtual meetings and we were told that the Labour Program has gotten creative with them during the pandemic, there are limits.

Our task force recognized the depth of knowledge of our interlocutors on the policy side of the Workplace Equity Department, including the capacity developed to administer the tool developed by the Labour Program. The Workplace Equity Information Management System (WEIMS) program enables LEEP and FCP employers to prepare and submit their reports online. The chair and vice-chair were provided with a demonstration of WEIMS’ capabilities alongside an emerging platform to share results on the pay transparency requirements under the Employment Equity Act framework.

On pay transparency under the Employment Equity Act framework, we were told that there was little ongoing exchange between the Labour Program and the Pay Equity Commissioner, despite the closely related framework and objectives under the Pay Equity Act. There are silos enabled by law.

Regarding data management, we were informed that a separate module of WEIMS is made available to the Canadian Human Rights Commission to review individual employer reports, and the Labour Program and the Canadian Human Rights Commission report meeting to discuss current and emerging issues. Canadian Human Rights Commission staff told the task force that they have to request some information available to the Labour Program on the WEIMS data management system directly from employers.

Remarkably, too, both the Labour Program and the Canadian Human Rights Commission told us that the audits conducted by the Canadian Human Rights Commission are not shared with the Labour Program that subsequently advises employers.

We could of course simply recommend that each institution share more information and collaborate. The impediments to sharing seemed not to be strictly legally mandated. Under Section 34 (3) of the Employment Equity Act, the Canadian Human Rights Commission is permitted to communicate or disclose “on any terms and conditions that the Commission considers appropriate”, to a minister of the Crown in right of Canada or to any officer or employee of Her Majesty, “for any purpose relating to the administration or enforcement” of the Employment Equity Act.

Regrettably, the current practice seems to reflect the institutional silos that have developed over time.

The division may have had merits in the past, but currently it is part of the problem.

So many years into a process that should be helping us to achieve employment equity, our task force came away concerned. The bifurcation of responsibilities seems to be a big part of the problem facing regulatory oversight of the Employment Equity Act framework.

Public Service Commission of Canada – an employer and an auditor

Employment equity implementation and regulatory oversight in the federal public service is cross-cutting.

In the core federal public administration, responsibility for carrying out the obligations under the Employment Equity Act is shared:

- The Public Service Commission (PSC) assumes responsibility for appointments to the public service or from within the public service, including promotions, under the Public Service Employment Act (Sections 11 & 29). These responsibilities are delegated to deputy heads of departments.

- The Treasury Board Secretariat’s Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (TBS-OCHRO) assumes human resources responsibilities under the Financial Administration Act (Section 11.1), including classifications of positions and establishing policies and programs to implement employment equity in the public service. The president of the Treasury Board tables public sector reports to Parliament on an annual basis.

The Public Service Commission’s employment equity responsibilities also include conducting investigations and audits under the Public Service Employment Act (Sections 11 & 17). As discussed in Chapter 4, this includes the power to conduct audits to determine whether there are biases or barriers that disadvantage persons belonging to any equity-seeking group. When assuming this role, the Public Service Commission has all the powers of a commissioner under the Inquiries Act.

The takeaway is that the Treasury Board Secretariat and the Public Service Commission share responsibility for identifying and removing barriers to achieving and sustaining employment equity, and for supporting departments to implement positive measures to close representation gaps.

We stress two features:

- First, the language of the Public Service Employment Act does not refer specifically to groups as designated by the Employment Equity Act. Any equity-seeking group is broader and suggests the kind of recognition of the importance of barrier removal that this report has emphasized.

- Second, the Public Service Commission has an auditing responsibility for recruitment processes. But the relationship between its own role in hiring – essentially delegated to departments and agencies - and its function as an auditor requires serious attention.

Responsible for safeguarding a merit-based, representative and non-partisan federal public service for the benefit of all Canadians, the Public Service Commission reports independently to Parliament.

Constituencies that met with our task force expressed frustration, however, at not being able to obtain the kind of granular data on merit and representativeness in the federal public service that show what is really happening on hiring, promotion and retention in the federal public service.

Names matter. If the Public Service Commission is the joint employer with responsibility for appointments, should we really be calling their reviews of employment practices by the deputy heads of departments to whom they have delegated their authority audits?

We learned that this concern is not merely a matter of terminology.

We were informed in particular that the Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s anticipated audit of an inclusive workplace for racialized employees was not expected to cover recruitment in the public service in part because the Public Service Commission conducts its own audits. We understood that the Auditor General’s decision was in part to respect responsibilities that are legislatively granted to other federal institutions and to avoid duplication.Footnote 16

We accorded the utmost seriousness to the call by the Public Service Commission for accountability to be increased by focusing on outcomes rather than simply monitoring efforts, that is, for an oversight body to ensure that progress is actually made to close gaps.Footnote 17

The Canadian Human Rights Commission

In effect, a demonstrably effective process which is frustratingly limited in coverage has been replaced by a broader process which lacks features critical to effective implementation.

Following the National Capital Alliance on Race Relations case before the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, the Canadian Human Rights Act was amended to prevent employment equity cases – that is, cases relying on statistics - from coming forward. Subsequently, the Canadian Human Rights Commission has been responsible for monitoring compliance, a responsibility entrusted to them as an independent agency. Stakeholders came to see the role initially assumed by the Labour Program in what was then HRDC as presenting a potential “conflict of interest” given its proximity to employers in other programs.Footnote 18 So responsibilities were divided up.

The Canadian Human Rights Commission monitors compliance by conducting compliance audits for both the federal public service and federally regulated private sector employers. It is also able to receive and examine complaints regarding non-compliance.Footnote 19

As discussed in detail below, the Canadian Human Rights Commission may also apply to the Chairperson of the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal to request that an Employment Equity Review Tribunal be appointed, with power to issue decisions enforceable as court orders.Footnote 20 This application is made when an employer requests a review of a decision issued by the Canadian Human Rights CommissionFootnote 21 or the Canadian Human Rights Commission requests the confirmation of its decision.Footnote 22 The Employment Equity Review Tribunal itself has barely ever been used.

The Canadian Human Rights Commission’s annual report is also submitted to Parliament, comprising information about the Canadian Human Rights Commission’s audits and enforcement activities.

The Canadian Human Rights Commission’s own implementation report

Given the CHRC’s role in auditing others, in both the public sector and the private sector, it was important to look at how it understood implementation within its own workplace.

The CHRC reported in November 2022 that it met its employment equity targets for all four equity groups, using the higher LMA rather than WFA applied in the federal public service as a benchmark. The CHRC added that as a small organization, “for some of the equity seeking groups, the departure of one or two employees can have a significant impact on representation”.Footnote 23 The report contains a workforce analysis in statistical terms, but an environmental scan revealed several areas of concern including access to career development opportunities, conflicting messages about parental leave, cumbersome and lengthy processes for accommodation requests that affect both workers with disabilities and religious minority workers seeking accommodation of their religious holidays, and the use of inappropriate language to discuss non-CHRC employees.

The language of systemic barriers was used sparingly, however, and obstacles to career development were not considered to be systemic employment equity barriers since the Employment Systems Review “did not identify differential treatment of employees because they belonged to an equity seeking group” but rather because there is an employee perception of arbitrariness. It was surprisingly unclear from the report whether belonging to an equity group was considered to be one of the factors. Moreover, without identifying a specific link to equity groups in the report, ready access to French language training was identified as a “common barrier to career advancement” with the problem apparently at the level of receiving the appropriate approvals to take the training due to high workload.Footnote 24

The CHRC recommended formalizing and structuring its approach to talent management, and better communication about staffing plans and decisions. It also recommended “right-size workload expectations”, the kind of measure that can support workers with family responsibilities and workers with disabilities who are disproportionately affected, but also support all employees’ mental health and work-life balance. The report underscored the importance of catalyzing support for achieving employment equity from the level of the Chief Commissioner.

The Canadian Human Rights Commission’s audits

The Employment Equity Unit, housed in the Proactive Compliance Branch of the Canadian Human Rights Commission, is small, and smaller than it was when it was first established. The dynamic, committed but clearly overworked team of professionals charged with auditing every Canadian workplace under federal Employment Equity Act jurisdiction, including the federal public service, could fit in one small conference room, with seats to spare.

The traditional approach is to conduct conventional audits of all employer implementation and consultation requirements under the Employment Equity Act. This entails enforcing the nine employer obligations under Section 22(1) of the Employment Equity Act, and summarized by the Commission in its auditing frameworkFootnote 25 as:

- Collection of workforce information

- Workforce analysis

- Review of employment systems, policies and practices

- Employment equity plan

- Implementation and monitoring of employment equity plan

- Periodic review and revision of employment equity plan

- Information about employment equity

- Consultation and collaboration

- Employment equity records

Under the Employment Equity Act, the CHRC conducts a comprehensive, conventional audit, then CHRC follows up with written directions to the employer to undertake necessary steps. There are statutory limits: as discussed in Chapter 4, the directions may not cause undue hardship; the direction must not require unqualified people to be hired or breach the merit principle in the federal public service. They may not require new jobs to be created. They must not impose a quota; rather, they must consider the appropriate factors for setting numerical targets.

An employer may request a review of a direction, or the CHRC may apply for a Tribunal order to confirm a direction. Both are understood that this is meant to be a last resort. The focus of the legislation is on persuasion.

Recently, in an attempt to be responsive and creative, despite limited resources, the Canadian Human Rights Commission has also been conducting horizontal audits. They include a Horizontal Audit on Indigenous employment in the banking and financial sector released in 2019, and a Horizontal Audit in the Communications Sector: Improving Representation for People with Disabilities, released in 2022.

The CHRC has largely lost what limited on-site capacity it initially had. The paper-intensive approach to audits – which in one recent case for the public service entailed an audit survey sent to the 47 public service departments and agencies with 500+ employees and out of which they selected 18 to submit to a full documentary assessment coupled with interviews with employees from different levels of the organization - may reflect the restrictions in the context of a pandemic where most employees were not working in the office, but one unavoidable issue for the CHRC remains the limits to what can be done with its current resources.

There is no use putting a gloss on this challenge: the CHRC’s Employment Equity Division, with 11 staff members, does not have anywhere near the capacity necessary to undertake their crucial oversight work.

Although it is responsible for undertaking conventional audits of employers, covering all 9 requirements found in the Employment Equity Act, it has only audited 423 employers between 1997 and 2021 for a total of 814 audits.Footnote 26

Not surprisingly, we learned that some employers tend to react to the audits, rather than undertaking proactive measures in advance.Footnote 27 Given the small number of audits conducted, there is little incentive to do otherwise.

The CHRC informs employers in its Framework for Compliance Audits that although the information gathered is treated as confidential under Section 34 of the Employment Equity Act, the CHRC is subject to disclosure requirements of the Access to Information Act, which take precedence.

Our task force was told by the outgoing Chief Commissioner that the CHRC shared a commitment to transparency and strengthening the Employment Equity Act framework. On direct request from the task force chair, the CHRC made a small selection of anonymized audits available for the purpose of this review. The CHRC shared conventional audits and background audits to a horizontal audit that had not yet been released on the representation of racialized people in the federal public service. Horizontal audit reports are already publicly available on the CHRC’s website.

The conventional audits reviewed are discussed below in some detail precisely because they have rarely been externally reviewed.

The conventional audits contained employment equity data profiles including analyses of the percentage of the equity group in the specific workplace as well as the attainment rates and a discussion of those results over time. Past audits were summarized and discussed in relation to the current audit results. They addressed employment equity groups as a whole.

Alongside the representation analysis was a separate section providing information about the employer, its employment equity program, previous employment equity audits and the audit’s findings.

It was important to see within those documents that the CHRC affirmed that employment equity is not just about the numbers. It stressed the steps that need to be taken beyond current levels of representation.

Unfortunately, some of the audits were not terribly detailed. They did not suggest that the audits permitted a “deep dive” into the employer’s organizational behaviour. They suggested that much of the auditing took the form of an exchange and analysis of documents submitted. Given the size of the audit team, this is hardly a surprise.

On implementation including barrier removal, in one case, the audit revealed that the governmental unit or agency had not completed an employment systems review or a valid employment equity plan based on recent workforce analysis and the results of an employment systems review (ESR). They indicated that they intended to hire a consultant to conduct an ESR. The CHRC noted that they were required to conduct the audit sooner than it was apparently planned to be conducted.

Although the language of diversity and inclusion was all over the reports, the CHRC’s audit showed that it was not letting generic EDI practices substitute for the specific requirements of the Employment Equity Act:

- It is also important that the CHRC clarified that a Diversity and Inclusion Strategic Plan, which had some similarities to an Employment Equity Action Plan, was not based on the Employment Systems Review so was not an “evidence-based” action plan.

- Similarly, some of the Diversity and Inclusion training could not be considered a “strategy” for external hiring of racialized persons into management and executive roles. Promised items - like a toolkit to support the hiring - were not submitted to the CHRC for review.

The examples of barriers identified by the CHRC varied. They included barriers in gaining access to telework. Another audit indicated that there was “systemic hostility toward racialized women who eat lunches from their cultural backgrounds at work” with co-worker complaints about smells and “an order from an executive against ‘smelly food’ in the workplace.”

The CHRC’s remedial action called upon the agency to develop formal strategies for hiring. The CHRC was clearly moving beyond the merely symbolic to identify whether strategies were actually in place to develop a specialized skillset among the staff of the department, train hiring managers to address attitudinal barriers, and address the untapped internal talent of overqualified and loyal staff whose belief in the mandate of the organization contributed to them staying in junior roles despite their educational and professional attainment.

In other audits, the CHRC wanted to see actual performance goals for hiring managers to close the employment equity gaps for racialized workers. Although the evaluations were somewhat terse and a bit formulaic, the message was clear: the performance indicators for hiring should be specific; moreover, even if a group happens to be appropriately represented, there is still a responsibility to monitor to maintain the workforce availability rate.

The CHRC looked closely at the organizational resources available to carry out the employer’s plan. Finally, the CHRC wanted to see an annual analysis of reasonable progress but could not, in the absence of that plan. Audits showed that the CHRC sought evidence-based employment equity plans.

In some audits, the CHRC might report that barriers must be addressed. They might direct an employer to build a “management action plan,” that is, a schedule of the items requiring remedial action with a deadline by which to complete them.

But the CHRC provided no guidance on how to do so in the audit report.

In another audit, and in the absence of an employment systems review report that should already have been available, the CHRC called for an employment systems review to be prepared by a particular date. But these kinds of audits just illustrate the problem: most of these legislated requirements should already have been completed and ready for the CHRC’s compliance audit.

It was frankly troubling to read this kind of advice, given to employers that have been in the program for decades. And the employer was in the federal public service, which should set an example. The audit sounded at best like the kind of advice that should have been coming from the body responsible for monitoring compliance to employers that had just enrolled in the program or had produced their first report.

The upshot: this public service employer was given a later date to complete what should already have been done by law. The CHRC provided little guidance on how.

There were no immediate consequences for not already having met the legal requirements.

It is some consolation that the audit process closes only once the CHRC has assessed the evidence to ensure that each employer has met the requirements of the Management Action Plan prepared by the CHRC. But the auditors are overworked and under-resourced.

Since the Labour Program does not receive the audits, there is no ability to follow up when the employer submits the next employment equity report.

A betting employer could wager that not much will happen.

Even the list of barriers identified in an audit of a high performing unit, which was praised for exceeding workforce availability for the groups under consideration, and for taking important outward-facing initiatives suggested that there would be problems in sustaining employment equity. The report found the following barriers:

- Affinity bias, or hiring, promoting or granting “acting” assignments to people who look like or have similar backgrounds to them

- Lack of transparency in staffing processes

- Unconscious bias or stereotypes, and

- Lack of intercultural competence

The audits listed these problems, but without much granularity. Without follow up support, it is reasonable to worry that little will change.

On meaningful consultations, the Employment Equity Act requirements did not figure prominently in the conventional audit reports reviewed. Consultations were assessed as one of the sub-lines under the barrier-removal line of inquiry. In the background audits conducted for the announced horizontal audit for racialized employees in the federal public service, departments were assessed on whether they consulted with racialized employees to identify possible barriers in recruitment training, coaching, evaluation, promotion, discipline and termination; in respect of workflow and procedures; in respect of workplace climate and acceptance, and in respect of the availability of accommodation.

In one case, the documentation provided to the CHRC by an employer – largely slides of presentations – were considered not to constitute proof of consultations with racialized employees on barriers. Positive practices were acknowledged, but were not considered to replace the need for consultations with racialized employees for the purposes of an employment systems review.

Employers might submit a schedule of meetings with bargaining agents in which EDI was on the agenda. But reference to bargaining agents was almost entirely absent from the audits provided for the task force’s review.

The CHRC audits call for consultation, and clearly have a sense of what is inadequate, but seems not to offer guidance on how to structure consultations in order to be compliant with the Employment Equity Act.

Horizontal and Blitz Audits are an example of the room available for innovation on regulatory oversight even in the midst of significant constraints:

- The CHRC has shown creativity given its extremely limited resources, by establishing a horizontal auditing practice that allows it to identify and take a deeper dive into systemic issues faced by a particular designated group and publish a sector-wide report. They have the potential advantage of providing insight into specific issues in specific sectors.

- The CHRC has also developed blitz audits to reach more employers, by focusing on 2 of the entire 9 obligations listed above that the CHRC is required to audit under the Employment Equity Act – this approach is used with smaller employers, that is, those with fewer than 300 employees.

But frustrations have been expressed about these auditing practices, given the generality of the reporting in the horizontal audits currently available to the public and the small number of workplaces ultimately audited. According to the Public Service Alliance of Canada, for example, horizontal audits run the risk of lowering the standard necessary to ensure that employment equity is meaningfully implemented.Footnote 28

The CHRC’s 2019 Horizontal Audit on Indigenous Employment in the Banking and Financial Sector entailed 36 completed surveys and 10 second level audits. In contrast, in over 20 years since 1997, the CHRC reported that it had completed close to 80 audits in the sector of 240,000 employees, or fewer than 4 audits in the entire sector per year.

The CHRC’s 2022 Horizontal Audit in the Communications Sector: Improving Representation for People with Disabilities entailed 58 employers – in an important development, identified in an annex - who completed the survey, and 17 who were subjected to a full audit. Much of it took place during the COVID-19 pandemic so the CHRC graciously acknowledged the participation despite the challenges. It reported however that only 41.4% of those surveyed had taken any measures to eliminate employment barriers. Only 2 of 17 had established performance indicators for hiring managers. They noted that while the representation of people with disabilities in the communications sector had increased — from 1.7% in 2011 to 3.7% in 2019 — it is still well below the availability rate of 9.1%. The CHRC’s own frustration seemed apparent: it reported that “even after 25 years of the Act being in force, the Commission still had to require all 17 of the employers that were the subject of a full audit to sign a management action plan.”Footnote 29

Both horizontal audits seemed to confirm the extent of the underrepresentation, and the lack of comprehensive communication on how to identify employment barriers with the specificity needed to address them. The CHRC expressed the hope that the audit findings would assist the concerned sectors. Yet the separation between the Labour Program and the CHRC as well as the chronic underfunding do not facilitate the kind of follow up that would be needed to foster effective change.

Commendable creativity aside, the conclusion is unavoidable: Employment equity is the federal government’s commitment to substantive equality at work. It requires and deserves more than 11 overworked auditors and poorly coordinated, bifurcated regulatory oversight. It is time for change.

It is important for legislative frameworks to assume good faith. The federal government is accountable for ensuring that there is proper public oversight. But surely, we can accept that non-compliance can happen for reasons other than a lack of knowledge. If we persist in assuming that all we need is more training, the legislative framework that seeks to support one of Canada’s fundamental values, substantive equality, risks being undermined.

The one-stop shop: Fundamentally rethinking oversight

It is time for change.

One suggestion we received was that employers should be able to count on a “guichet unique” – a one-stop shop – through which to engage with questions affecting workplace equity. The one-stopshop should include both the specialists who can accompany employers, as well as the measures and programs of governmental financial aid necessary to make achieving substantive equality in the workplace a reality.

The suggestion corresponds with some of the most important contemporary thinking on how to deliver services in an effective and efficient manner. It is the approach we recommend.

Regulatory oversight to achieve and sustain employment equity

There is nothing inevitable about the employment equity enforcement gap.Footnote 30 Research confirms that the success of Canada’s employment equity framework depends in significant measure on “increased and vigorous enforcement”.Footnote 31

We are nowhere near there.

The time has come to adopt a unified model, which would ensure that one independent entity, reporting directly to Parliament, has comprehensive regulatory oversight for the Employment Equity Act framework.

This would be consistent with the contemporary equity frameworks put in place by the federal government under the Pay Equity Act and the Accessible Canada Act.

Creating the position of an Employment Equity Commissioner was recommended by a wide range of stakeholders, including the Canadian Human Rights Commission.

There are many strengths to the Commissioner model, which requires individual integrity and credibility alongside a depth of expertise in alternative dispute resolution methods to provide guidance, support, and identify sustainable ways to ensure that the frameworks, and their purposes, are achieved. However, commissioners cannot achieve equity or accessibility alone. They require significant resources including personnel to make sure the breadth of their mandate is respected. To succeed, they must be supported by a robust office helping to carry out and sustain their mandate.

Cultivating independent guidance and regulatory oversight

The Employment Equity Commissioner will be key to ensuring that employers and joint equity committees receive the guidance they need to achieve substantive equality in the workplace.

We heard from employers and service providers who are putting in place innovative employment equity programs, often working with great energy and intentionality to arrive at their representation goals. When they do so, they should be able to count on supportive, sustainable guidance. For example, one service provider adopted a strategic hiring approach and indicated they did so on the recommendation of the CHRC. However, they received no written advice. They anticipated some media attention but were surprised not to have the CHRC take a more explicit position to explain the practice to the public at large.

There should be public audits of EE progress, comparable across departments so that departments are held accountable for progress in an explicit way. It is not easy to discern how departments are doing on EE, other than to work through reams and reams of TBS data. Total transparency requires resources – to ensure that departments and central agencies can report explicitly, rather than making it difficult to understand the data. It has been great to have access to the data, but analysis is needed so that citizens, employees, bargaining agents and others can easily track progress.

It is also clear that employers that adopt special measures under the Employment Equity Act to achieve greater representation within their workplace, or special programs to improve representation of other equity groups under the Canadian Human Rights Act need to be prepared to defend their programs. For example, we heard from a major Crown corporation that explained their decision to adopt a closed pool for a strategic hire and their resolve to do so transparently and to face public opinion on the matter.

Employers implementing special programs should be able to count on clear, written guidance from the Equity Commissioner.

Recommendation 6.1: An Employment Equity Commissioner should be established.

A model for guidance – the Pay Equity Commissioner:

The model of the Pay Equity Commissioner offers some important insights for a revised Employment Equity Act framework. The Pay Equity Commissioner is a full-time member of the CHRC, established under the CHRA. The Commissioner’s mandate as set out in Section 104(1) of the Pay Equity Act, is to

- ensure the administration and enforcement of the Pay Equity Act

- assist persons in understanding their rights and obligations under the Pay Equity Act, and

- facilitate the resolution of disputes relating to pay equity

The Pay Equity Commissioner’s list of duties to carry out the mandate is significant, and includes monitoring implementation of the Pay Equity Act and offering assistance to employers, employees and bargaining agents, notably in relation to complaints, objections and disputes. The Commissioner decides whether a matter falls within their jurisdiction. The education and information dimension of the duties figures prominently, alongside the duty to develop tools to promote compliance with the Pay Equity Act and publish research (Section 104(2) (c) & (e)), including an opportunity or obligation as the case may be to provide advice to the Minister or to the House of Commons or Senate under Sections 114 & 115.

The Pay Equity Commissioner is also responsible for conducting compliance audits, with a full complement of auditing powers. The Commissioner may require an employer to conduct an internal audit and report the results. The Commissioner may also conduct investigations. On reasonable grounds to believe that there is a contravention of the Pay Equity Act, the Commissioner has the power to order the employer, employee or bargaining agent to terminate the contravention. Finally, the Pay Equity Act contemplates administrative monetary penalties in the event of a violation, with a view to promoting compliance rather than punishing (Section 126). Administrative monetary penalties (AMPs) are financial penalties or fines, which can be imposed when the regulatory scheme is violated, without having to go to court. AMPs seek to provide fair and efficient approaches to ensure compliance.Footnote 32 Violations – classified as minor, serious or very serious – are subject to a range of penalties with maxima of $30,000 for employers between 10 -99 employees and $50,000 for over 100 employees (Section 127). While specific violations are set by regulations, the legislation is clear: due diligence or reasonable belief in the existence of facts that if true would exonerate the employer are not available defenses (Section 133). Continuing violations constitute separate violations for each day they were committed or continued (Section 134).

The Commissioner may receive complaints from employers, employees or bargaining agents for a specific but fairly comprehensive set of matters. But the emphasis remains on finding an amicable solution and there is significant legislative scope to shape the litigation. The Pay Equity Commissioner is required to try to settle the matters, first (Section 154(1)) and may dismiss them if they are trivial, frivolous, vexatious or in bad faith; if they are beyond the Pay Equity Commissioner’s jurisprudence; or if the subject matter has been adequately dealt with another procedure.

The Pay Equity Commissioner has the power to review the notice of violation (Section 139), and the notice of decision contemplated in Section 161(1). The message is clear: the Pay Equity Act is meant to be complied with, and enforced. The process remains firmly within the hands of one office for a considerable time, although the Pay Equity Commissioner retains at any stage after a notice of dispute has been received, the right to refer the matter to the chairperson of the Tribunal. The Tribunal may also conduct a review. This is all in the shadow of the privative clause in Section 171 – “Every decision made under Section 170 is final and is not to be questioned or reviewed in any court.”

The Pay Equity Act already anticipates in Section 104(2)(f) that the Commissioner will “maintain close liaison with similar bodies or authorities in the provinces in order to coordinate efforts when appropriate”. With a new Employment Equity Commissioner, both jurisdictions should be encouraged to coordinate efforts as appropriate. This might be implicit if the Employment Equity Commissioner, like the Accessibility Commissioner, is also housed within the CHRC. However, as discussed below, it might well be time to offer a different institutional vision for the enforcement of workplace equity.

The list of recommendations below draws in part on the Pay Equity Commissioner model. The recommendations are not meant to offer a comprehensive list of the Employment Equity Commissioner’s powers or responsibilities.

A catalyst for change: Learning from the federal research funding agencies:

We heard repeatedly that an agency able to catalyze change is crucial. We learned from the model of implementation provided through the Canada Research Chairs program. While employers (the universities) might have initially acted because they faced requirements that were imposed by a funding agency due to a court settlement, many have now integrated proactive policies and approaches into their regular practices and explain their broader actions, beyond the Canada Research Chairs program, more generally as part of their adherence to EDI principles.Footnote 33 There was a fruitful balance struck: the funding agencies could at once offer incentive in the form of prestigious, well-funded research chairs, while requiring responsiveness to equity to meet established goals, and offering hands-on accompaniment to build employment systems review processes. The consequences of not making reasonable progress were clear: loss of future funding. Not only have goals increasingly been met. The effective, hands on, proactive regulatory oversight through the federal tri-agency funding councils and led by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, has made a significant difference.

We urge that the reasons for this progress not be overlooked in any proposed redesign of the federal research funding landscape.

We can learn from this process to support employment equity regulatory oversight. Compliance under the Employment Equity Act seeks to be reflexive and responsive. It needs regulatory oversight to be independent, supportive and strong.

Recommendation 6.2: The Employment Equity Commissioner should be independent and should report directly to Parliament.

Recommendation 6.3: The Employment Equity Commissioner should have legislative responsibility and powers that include the powers in Section 42 of the Employment Equity Act.

Recommendation 6.4: The Employment Equity Commissioner should have the legislative authority to collect information on the employment practices and policies of all covered employers in the federal public service and private sector, as well as under the Federal Contractors Program, for the purpose of ensuring that employment equity is implemented in their workplaces.

Recommendation 6.5: The Employment Equity Commissioner, like other federal commissioners including the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, the Commissioner of Official Languages, the Information Commissioner of Canada, the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada and the Commissioner of Lobbying, should be considered a contracting authority exempted from Section 4 of the Government Contracts Regulations.

Recommendation 6.6: The Employment Equity Commissioner should be responsible for regulatory oversight including workplace auditing.

Cultivating independent review – Advisory and review panel

It is only by regularly reviewing the [Employment Equity] Act that we can better identify and evaluate areas where accountability, compliance and enforcement improvements are needed. The current twenty-year gap in reviewing the Act is unacceptable, and has only deepened and exacerbated labour market inequities faced by marginalized workers. The government must regularly review the Act every five years as is currently prescribed.

It is well known that the 5-year review cycle Parliament foresaw in the Employment Equity Act has not been a reality. We recommend that an independent advisory panel be created, and that it hold responsibility for undertaking reviews no less frequently than once every 10 years.

We recommend that a 10-person advisory and review panel be established to inform the work of the Employment Equity Commissioner. The panel should comprise experts in employment equity and related human rights and labour and employment relations issues. Members should broadly reflect a composite of Canadian society as a whole, and ensure intersectional representation of each of the employment equity groups. It should be convened at least twice per year. It should have the responsibility to conduct the reviews that are to be submitted to Parliament by the Employment Equity Commissioner and rendered public. The advisory and review panel’s budget should include the resources to undertake the reviews no less than once every 10 years.

Recommendation 6.7: An Employment Equity Advisory and Review Panel should be established under the Employment Equity Act to inform the work of the Employment Equity Commissioner.

Recommendation 6.8: The Employment Equity Advisory and Review Panel should have the responsibility to conduct reviews no less frequently than once every 10 years, to be submitted to Parliament by the Employment Equity Commissioner and rendered public.

Ensuring institutional autonomy

Employment equity can readily be sidelined, not only through ideological attacks, but institutionally through severe funding challenges.Footnote 34 Human rights commissions across Canada have not been immune to significant budget cuts. Our task force has expressed our significant concern about the small staff size of those responsible for auditing compliance with the Employment Equity Act in both the public service and the private sector.

Employment equity programs are constitutionally protected under Sections 15(1) and 15(2) of the Charter, understood together. Attention must be paid to institutional autonomy and the ability to meet the magnitude of the task available.

Law does indeed convey commitment. And a lack of funding undermines law’s commitments.

Funding levels ultimately tell us what commitments we mean to keep. Our task force unfortunately heard a fair bit of cynicism on this point.

More troubling still is the deep-set presumption that equity work will be close to voluntary work, done out of duty and love by the very people who have faced structural inequity throughout their working lives. That assumption is replete with stereotypes on the basis of the very grounds that employment equity seeks to redress. Those stereotypes fuel employment barriers and pay inequities. The assumption perpetuates the undervaluing of the work to be done and can lead to stress and burnout for the people doing the equity work. Government should be setting a better example.

It is time to break out of the idea that equity work should be done on a nickel and a dime. If we are committed to championing employment equity in this global moment of rising intolerance, if we understand how critical substantive equality is to our workplaces, our economy as a whole, and our identity as Canadians, we must show it.

Employment equity requires real change; real support to implementation in workplaces; real auditing and oversight. If any one of the pillars is weak, it will remain highly unstable, and fail to achieve its results. If fortified, it can support societal inclusion and growth.

Recommendation 6.9: The staffing and funding envelope for the Employment Equity Commissioner should be commensurate with the magnitude of the responsibility, including the auditing responsibilities, and reviewed periodically to provide the regulatory oversight necessary to achieve and sustain employment equity across federally regulated employers.

Recommendation 6.10: The Employment Equity Commissioner should be legislatively guaranteed a separate budgetary envelope sufficient to ensure that the purposes of the Employment Equity Act can be fulfilled through appropriate staffing and mobility, and guided by the funding available to other independent commissioners that report directly to Parliament, including the Auditor-General of Canada. In particular,

- the auditing responsibility of the Employment Equity Commissioner should be funded at a level commensurate with the volume of covered employers in the federally regulated sector for which it assumes responsibility, and

- the responsibility for statistical analysis should be increased to meet the needs of an expanded Employment Equity Act and to ensure that the Office of the Employment Equity Commissioner can participate meaningfully in the Employment Equity Data Steering Committee.

Recommendation 6.11: The Employment Equity Act should provide that the Employment Equity Commissioner enjoys sufficient remedial and enforcement powers to ensure that the purposes of the legislation can be fulfilled.

Recommendation 6.12: The Public Service Employment Act and the Canada Labour Code should be amended to require them to notify the Employment Equity Commissioner when a matter relates to the Employment Equity Act and provide the power to refer a matter to the Employment Equity Commissioner.

Recommendation 6.13: Notice should be given to the Employment Equity Commissioner when a policy grievance has been referred to adjudication and a party to the grievance raises an issue involving the interpretation or application of the Employment Equity Act, in accordance with the regulations. The Employment Equity Commissioner should have standing in order to make submissions on the issues in the policy grievance.

Recommendation 6.14: The Employment Equity Commissioner should enjoy immunity and be precluded from giving evidence in civil suits in a manner analogous with Sections 178 & 179 of the Pay Equity Act.

Institutional architecture

Establishing supportive and sustainable regulatory oversight

The Committee emphasizes the importance of ensuring coordination and complementarity between the interlocking measures and strategies adopted, and between the various competent bodies with a view to ensuring coherence and enhancing impact, while avoiding duplication of efforts and promoting the optimal use of resources.

We want to ensure that the Employment Equity Commissioner is able to assure the level of regulatory oversight necessary to meet the purpose of the Employment Equity Act. There are three options:

- Option 1. House an Employment Equity Commissioner within the CHRC, through a buttressed proactive compliance branch

- Option 2. Create a stand-alone Office of the Employment Equity Commissioner

- Option 3. Build an Office of Equity Commissioners

Option 1: House an Employment Equity Commissioner within the CHRC, through a buttressed proactive compliance branch

Currently the Canadian Human Rights Commission houses the Employment Equity Division, the Accessibility Commissioner’s Unit and the Pay Equity Commissioner’s Unit within the Proactive Compliance Branch. The total staff of that branch is 65 persons, including the director general’s office. The Pay Equity Commissioner and the Accessibility Commissioner have a staff comprising primarily full time but also a few part time workers totalling 25 and 28 persons respectively. The Employment Equity Division has a staff of 11 persons.

Our task force heard concerns in particular about the capacity given to the CHRC to assume the responsibility for yet another commissioner. Some stakeholders categorically requested that the oversight bodies be separate from the CHRC and Tribunal systems, and representative of equity groups. Some cited a lack of resources to address the magnitude of the challenge. Others pointed to a lengthy history of inaction or inadequate action on systemic barriers, particularly as they relate to systemic racism.

The conclusions of the 2020 Hart Report are clear: while the CHRC has made a “laudable commitment” to strengthen how it handles race-based complaints, and taken “significant preliminary steps”, the path ahead of it is long and challenging.

In the thorough review of practices and procedures, former Ontario Human Rights Tribunal Vice-Chair Mark Hart identified a range of challenges. One was the discretion provided under Section 41(1)(a) or (b) of the Canadian Human Rights Act to dismiss a complaint where it appears that the alleged victim ought to exhaust grievances or another procedure under another Act of Parliament may be more appropriate. He called for these provisions not to be used automatically or perfunctorily and to be alive to the prospect that racialized complainants may face barriers to having their grievances processed appropriately.Footnote 35 Another centred on reducing the risk of anti-claimant bias, which he characterized in light of the #MeToo movement to affirm that “there is a difference between moving from a place of ‘I don’t believe you until you can prove it’, to starting from a place of hearing and accepting the claimant’s stated experience with an approach of openness and curiosity, without abdicating the need to ultimately assess the evidentiary support for the allegation required by the legal process”.Footnote 36 Yet another was the absence of support to most racialized claimants to properly prepare their complaints. He cited promising practices to support complainants in place in other Canadian jurisdictions, such as the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission, but that require resources.Footnote 37 The extent to which the CHRC, for limited resource reasons, may elect only to represent a complainant in a race-based complaint through “partial participation” was also a source of concern given the negative impact on cases that are already “notoriously difficult to prove at a hearing”.Footnote 38 And he was consistently mindful of the limited resources available to the CHRC and quite explicitly sought to tailor his recommendations in light of the limits.

The overall thrust of the Hart Report is that for the CHRC to be successful, it requires not only sustained commitment, but significant resources.Footnote 39

The CHRC has embarked upon a modernization process, which it describes as a work-in-progress.Footnote 40

On 6 March 2023, the Public Service Staff Relations Board found that the CHRC had breached the “no discrimination” clause of its collective agreement. This has prompted inquiries into the CHRC and to state the least, has not helped instill confidence in the CHRC.

The widely acknowledged limited resources of the CHRC are a source of considerable concern. Does it make sense to continue to add critical equity responsibilities to the CHRC’s mandate without a clear commitment to securing for it a budgetary envelope that would enable these mandates to be conducted in the fulsome, comprehensive manner that a federal all-of-government commitment to employment equity would require?

There are structural integration questions that also need to be thought out. Consider, for example, that while the Pay Equity Commissioner is established under the Canadian Human Rights Commission and reports to the Minister (of Labour), the Pay Equity Commissioner’s staff reports ultimately to the Chief Commissioner. The integration of thematic commissioners within the Canadian Human Rights Commission requires great care from a structural perspective, and significant resources.

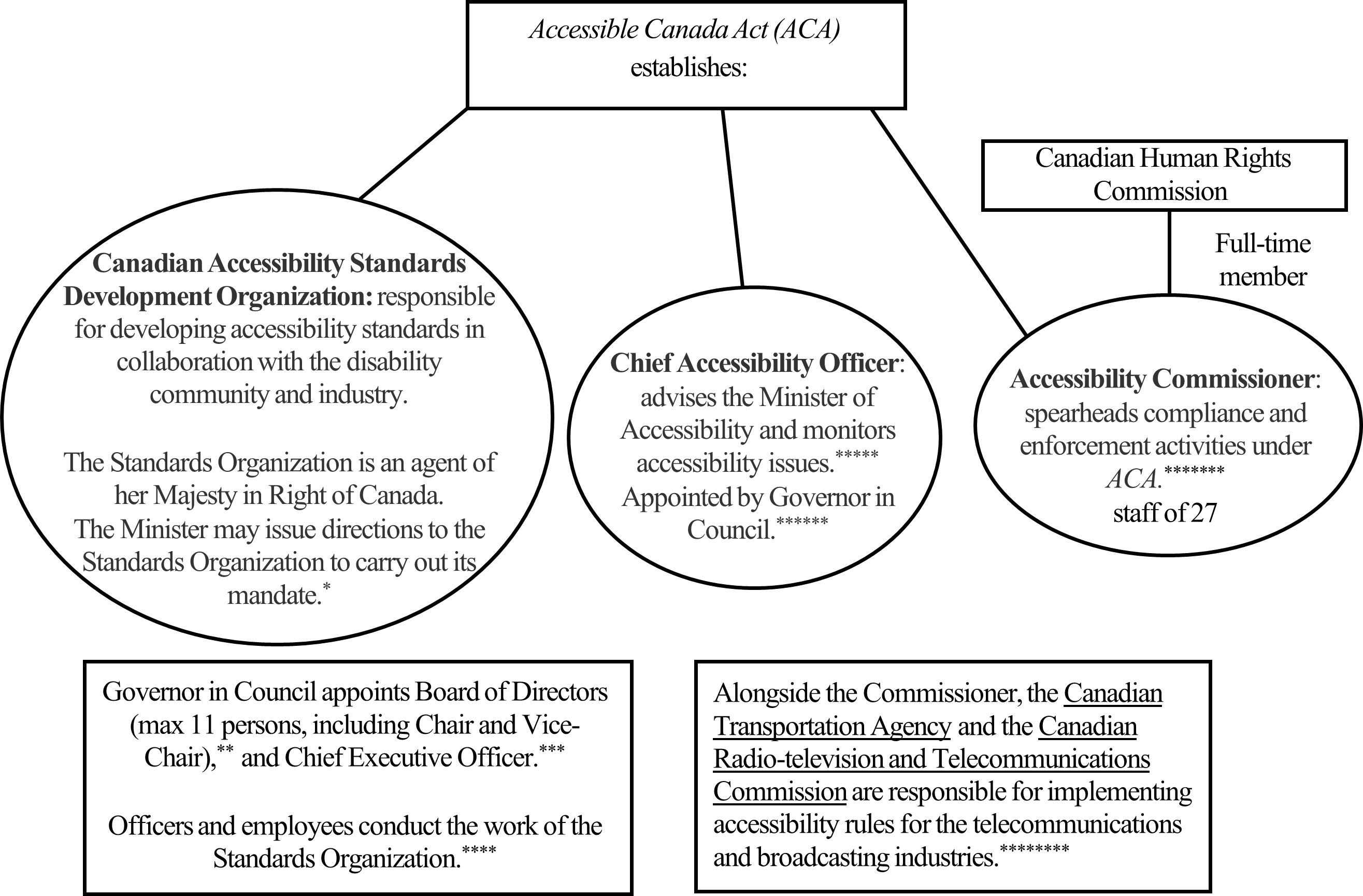

The model below offers a map of the Accessibility Commissioner’s partial integration into the Canadian Human Rights Commission structure:

The Accessible Canada Act and the Accessibility Commissioner

Text description of figure 6.1

The Accessible Canada Act (ACA) establishes:

- The Canadian Accessibility Standards Development Organization: responsible for developing accessibility standards in collaboration with the disability community and industry.

- The Standards Organization is an agent of her Majesty in Right of Canada. The Minister may issue directions to the Standards Organization to carry out its mandate.*

- Chief Accessibility Officer: advises the Minister of Accessibility and monitors accessibility issues.***** Appointed by Governor in Council.******

Under the ACA and the Canadian Human Rights Commission is:

- Accessibility Commissioner: (Full-time member of the Canadian Human Rights Commission) spearheads compliance and enforcement activities under ACA.******* Staff of 27.

The Governor in Council appoints Board of Directors (max 11 persons, including Chair and Vice-Chair),** and Chief Executive Officer.*** Officers and employees conduct the work of the Standards Organization.****

Alongside the Commissioner, the Canadian Transportation Agency and the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission are responsible for implementing accessibility rules for the telecommunications and broadcasting industries.********

- * Accessible Canada Act, SC 2019, c. 10 ss. 17(1) and (2), 21(1) [ACA]; Government of Canada, “News Release - Historic appointment of Canada’s first Accessibility Commissioner” (April 25, 2022), online: <https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/news/2022/04/historic-appointment-of-canadas-first-accessibility-commissioner.html> .

- ** Accessible Canada Act, s. 22, 23.

- *** Accessible Canada Act, s. 30.

- **** Accessible Canada Act, s. 33.

- ***** Government of Canada, “News Release: Historic appointment of Canada’s first Accessibility Commissioner” (25 April 2022).

- ****** Accessible Canada Act, s. 111.

- ******* Appointed under Canadian Human Rights Act s. 26(1). Also responsible for monitoring the Government of Canada’s compliance with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Canadian Human Rights Commission, “The Accessible Canada Act” online.

- After consulting with the Chief Commissioner of the Canadian Human Rights Commission, the Accessibility Commissioner may delegate their powers, duties or functions to another member of the Canadian Human Rights Commission (other than the Chief Commissioner) or to a member or staff of that Commission. ACA s. 40(2), 40(3).

- ******** Accessible Canada Act ss. 42(1), 60(1); Canada Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, The Accessible Canada Act and the CRTC Accessibility Reporting Regulations (Sept 20, 2022), online: < https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/industr/acces/index.htm>; Canadian Transportation Agency, “Summary of the Accessible Canada Act and Reporting Regulations: A Guide on Accessibility Plans” (Feb 18, 2022), online: <https://www.otc-cta.gc.ca/eng/summary-accessible-transportation-planning-and-reporting-regulations-accessibility-plans>; Laverne A Jacobs et al, The Annotated Accessible Canada Act, University of Windsor, Faculty of Law, 2021 CanLIIDocs 987, https://canlii.ca/t/t58r

The integration of thematic commissioners within the Canadian Human Rights Commission may respect the preference for broad human rights mandates to remain within national human rights institutions within the Principles Relating to the Status of National Human Rights Institutions known as the Paris Principles. However, the remarkable and chronic underfunding, the serious concerns raised by some of the equity groups and the lack of sustained attention to functional fit call for a response of a different magnitude.

During its 2019 visit to Canada, the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities commended developments under the Accessible Canada Act ensuring independent monitoring through the Canadian Human Rights Commission, while underlining the importance of ensuring that the Commission receive “an unequivocal national monitoring mandate and appropriate financial and human resources to implement this function”.Footnote 41

If this option is adopted, the funding envelope and the institutional configuration will need to be significantly rethought.

This is our second-best option of the three.

Option 2: Create a stand-alone Office of the Employment Equity Commissioner

The 2004 Bilson report recommended the creation of an entire, stand-alone Pay Equity Commission, with a specific tribunal structure devoted to pay equity appeals. Our task force has received similar appeals, for an independent enforcement body mandated to audit, to investigate and to ensure the removal of barriers, with the power to hear, address and adjudicate complaints. They have tended to be responses to the concerns about the Canadian Human Rights Commission identified above. They reflect the thrust of this report: ensuring that employment equity constitutes a one-stop-shop for employers to obtain the insight and guidance they need to ensure that employment equity is effectively implemented.

In considering this option, we drew inspiration from the many independent offices that currently exist. Below we map several of them, with a view to providing insight into staffing, budgeting, and structural reporting. There is much to learn from them.

Each represents responsibilities understood as central to our self-understanding in Canada. From the Office of the Attorney General to the Office of Official Languages and the Office of the Privacy Commissioner, the significance of the role is reflected in the significance of the autonomy provided. Employment equity warrants comparable treatment.

There are challenges, however. Primary among them is that rather than harmonizing employment equity with other existing legislative frameworks on equity, a separate office runs the risk of building yet another silo. It may also leave employment equity on its own and too vulnerable in the future.

For these reasons and as explained below, we support this option but would prefer option 3.

Option 3: Establish an Office of Equity Commissioners

It is because of the importance of harmonization that this report introduces the prospect of building an Office of Equity Commissioners. The Office would include the Pay Equity Commissioner and the Accessibility Commissioner, both currently housed in the Canadian Human Rights Commission and part of the Proactive Compliance Branch.

There are important examples of institutional experimentation with the appropriate mix of human rights and labour rights bodies across Canada.Footnote 42 Experimentation with human rights enforcement structures continues across Canada. Both the work to integrate equity tribunals in Ontario and the integration in Québec of the pay equity commission with the labour standards and occupational safety and health tribunal suggest the kind of creativity that seems important federally to achieve employment equity and support harmonization of responsibilities on Canadian workplaces.

Our consultations point toward the value in establishing an Office of Equity Commissioners, through which the Employment Equity Commissioner, the Pay Equity Commissioner and the Accessibility Commissioner could be jointly housed.

It would be our expectation that like the Office of the Official Languages Commissioner and the Office of the Privacy Commissioner, a recommended Office of Equity Commissioners should report directly to Parliament.

The Office of the Equity Commissioner’s relationship to the Canadian Human Rights Commission should be a horizontal dotted line, with initiatives to ensure that there is collaboration with the Chief Human Rights Commissioner including in its role as Canada’s National Human Rights Institution.

The Office of Equity Commissioners should receive a staffing and budgetary envelope that is on par with the seriousness of the responsibility that they face. A separate budgetary envelope for the Office of Equity Commissioners is key; the task force has understood the challenge of holding resources constant for employment equity when there are competing demands and employment equity is not clearly prioritized.

The Office of Equity Commissioners should have a dedicated team of auditors, and significantly increased in number, on par with the extensive responsibility, who are conversant with all three covered mandates, representative of employment equity groups and highly qualified in understanding and addressing substantive equality.

It is clear that the Accessibility Commissioner’s mandate exceeds the workplace although the workplace is a critical dimension that invariably intersects with other areas. We consider this to be a positive feature of the proposed Office of Equity Commissioners, as it avoids further silos when barrier removal serves multiple accessibility purposes in society.

The relationship of the Office of Equity Commissioners to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, through which the Employment Equity Review Tribunal is linked, should be similar to the relationship between the Canadian Human Rights Commission and the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal.

The establishment of an Office of Equity Commissioners will not be a panacea.

The Office of Equity Commissioners must be fully supported, and there must be support around the Commissioners to ensure sustainability.

Models to guide the choice of options

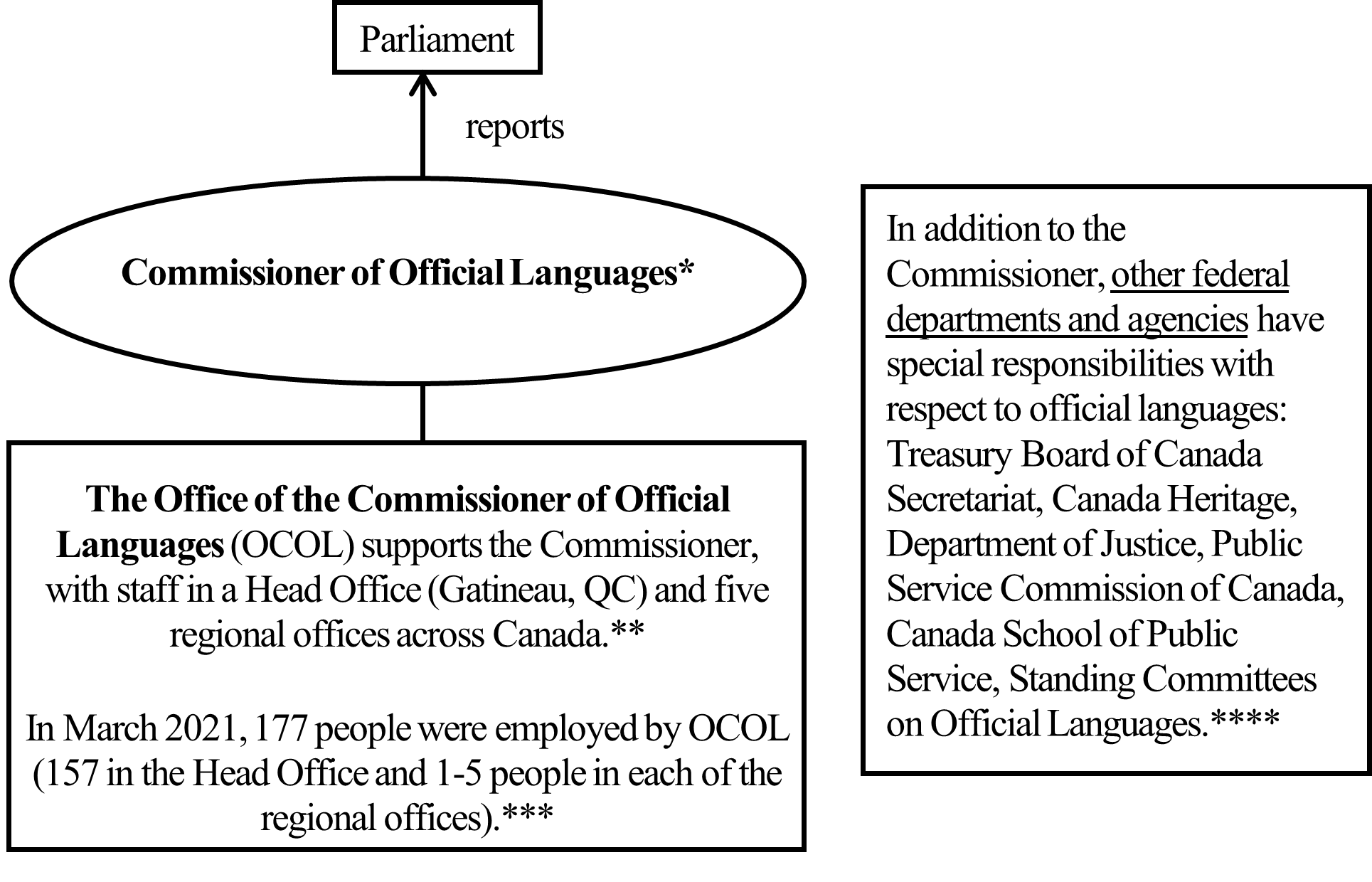

There are other Commissioner models available within the federal government and beyond. The task force canvassed a number of Commissioners’ offices within the federal system, to gain a closer understanding of the different structures within and beyond the Canadian Human Rights Commission that might inform the decision about the appropriate options for an Employment Equity Commissioner. The Office of the Auditor General of Canada, the Official Languages Commissioner and the Privacy Commissioner offer particular insights, including on funding levels.

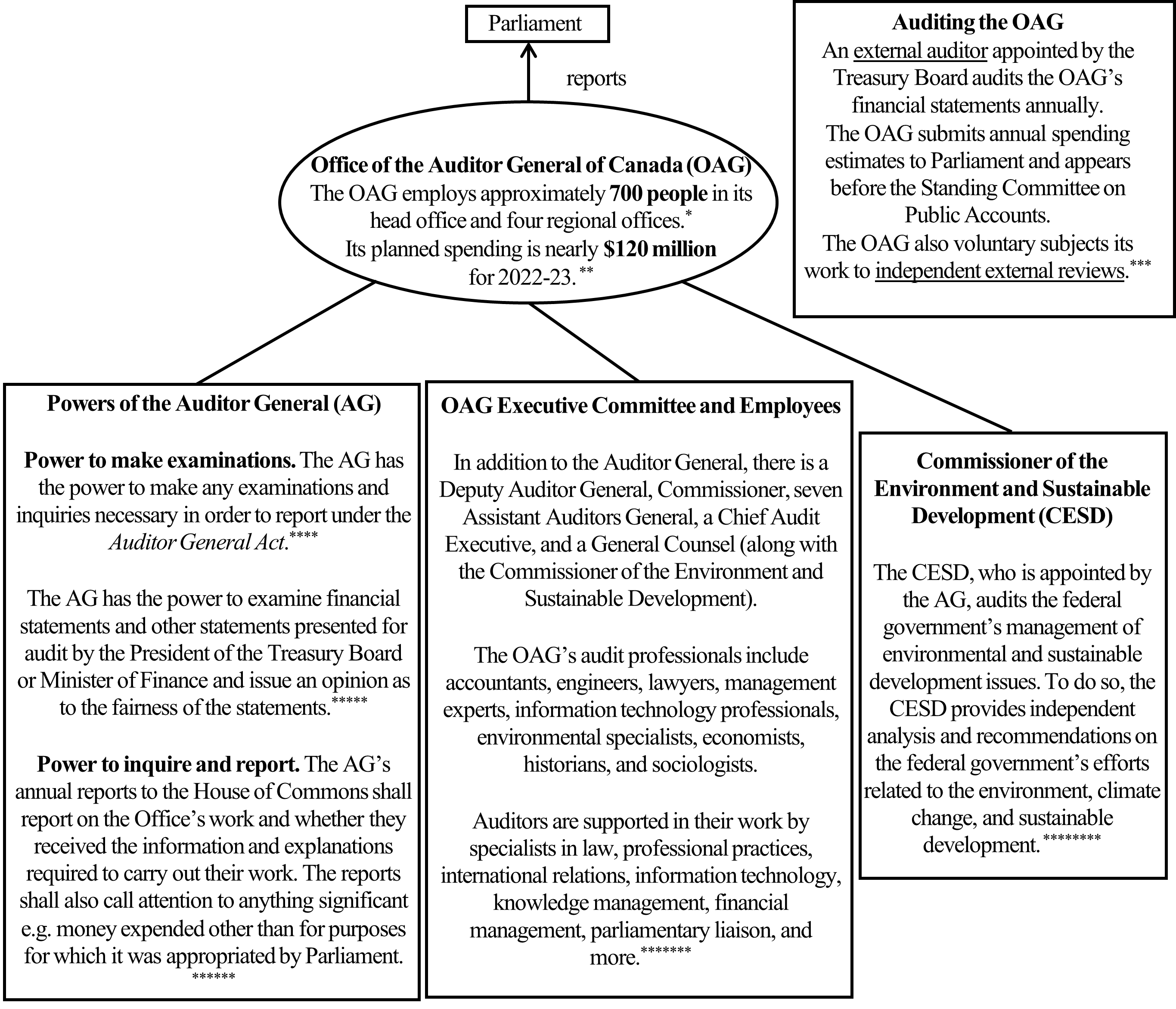

Office of the Auditor General of Canada

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG) is independent of government, although it is subject to the Employment Equity Act and acknowledges the cross-cutting, underlying value to its work and for its own workplace. The Office of the Auditor General also understands its vision to be a transformative one – “to bring together people, expertise and technology to transform Canada’s future, one audit at a time.Footnote 43 It is noteworthy that the OAG’s publicly available, online employment equity report was one of the rare public reports to include the employment equity plan with each commitment, measure, targets and results.

The OAG differs from most other government departments and agencies because of its independence from the government of the day and its reporting relationship to Parliament. Controls are in place to ensure the OAG’s independence, including exemptions from certain Treasury Board policy requirements, its status as a separate employer, and a 10-year non-renewable term for the Auditor General.

In the 2018 report, the Auditor General explained why the report into inappropriate sexual behaviour in the Canadian Armed Forces was conducted in the following terms:

This audit is important because inappropriate sexual behaviour is wrong. It undermines good order and discipline, goes against the professional values and ethical principles of the Department of National Defence and the Forces, and weakens cohesion within the Forces… Moreover, if inappropriate sexual behaviour persists, it could negatively affect the Forces’ recruitment and retention efforts.Footnote 44

It conducted the review following the External Review of Sexual Harassment in the Canadian Armed Forces and referenced it. The 2000 Task Force also recommended that external advice and independent review should be enabled. They recommended that a three-member external advisory group, including one member from the private sector in the position of management, be appointed for 5-year mandates to advise on implementation in the public service.

During the deliberations, we considered whether the Auditor-General might be an appropriate institution to assume responsibility for the all-of-government approach to achieving employment equity. This was an imperfect fit, not least because the Employment Equity Act requires private sector reporting beyond Crown corporations. Employment Equity Act implementation requires auditing, certainly, and it requires so much more to foster ongoing implementation. We want the dynamic regulatory oversight and engagement of the Commissioner model foregrounded through the Pay Equity Commissioner.

However, the Auditor General’s model is important for another reason: it gives a really clear example of the independence, the people power and the resources necessary to do auditing work well. Serious auditing requires serious resource allocation:

Text description of figure 6.2

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG): The OAG reports to Parliament. and employs approximately 700 people in its head office and four regional offices.* Its planned spending is nearly $120 million for 2022-23.**

- The Powers of the Auditor General (AG):

- Power to make examinations. The AG has the power to make any examinations and inquiries necessary in order to report under the Auditor General Act.****

- The AG has the power to examine financial statements and other statements presented for audit by the President of the Treasury Board or Minister of Finance and issue an opinion as to the fairness of the statements.*****

- Power to inquire and report. The AG’s annual reports to the House of Commons shall report on the Office’s work and whether they received the information and explanations required to carry out their work. The reports shall also call attention to anything significant e.g. money expended other than for purposes for which it was appropriated by Parliament.******

- The OAG Executive Committee and Employees:

- In addition to the Auditor General, there is a Deputy Auditor General, Commissioner, seven Assistant Auditors General, a Chief Audit Executive, and a General Counsel (along with the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development).

- The OAG’s audit professionals include accountants, engineers, lawyers, management experts, information technology professionals, environmental specialists, economists, historians, and sociologists.

- Auditors are supported in their work by specialists in law, professional practices, international relations, information technology, knowledge management, financial management, parliamentary liaison, and more.*******

- The Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development (CESD):

- The CESD, who is appointed by the AG, audits the federal government’s management of environmental and sustainable development issues. To do so, the CESD provides independent analysis and recommendations on the federal government’s efforts related to the environment, climate change, and sustainable development.********

- The Powers of the Auditor General (AG):

- Auditing the OAG: An external auditor appointed by the Treasury Board audits the OAG’s financial statements annually. The OAG submits annual spending estimates to Parliament and appears before the Standing Committee on Public Accounts. The OAG also voluntary subjects its work to independent external reviews.***

- * Office of the Auditor General of Canada, “Who We Are,” online: <https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/au_fs_e_370.html#organization>. The OAG’s legislative basis is in the Auditor General Act, the Financial Administration Act, among other statutes.

- ** Office of the Auditor General of Canada, “2022-23 Departmental Plan” (Feb. 4, 2022), online: <https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/acc_rpt_e_44002.html>.

- *** Office of the Auditor General of Canada, “Who We Are.” online: <https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/au_fs_e_370.html#organization>.

- **** Auditor General Act, RSC, 1985, c. A-17, s. 5

- ***** Auditor General Act, RSC, 1985, c. A-17, s. 6; Financial Administration Act, RSC, 1985, c. F-11, s. 64.

- ****** Auditor General Act, RSC, 1985, c. A-17, s. 7(1) and (2).

- ******* Office of the Auditor General of Canada, “Who We Are” online: <https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/au_fs_e_370.html#organization>.

- ******** Office of the Auditor General of Canada, “Who We Are,” online: https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/au_fs_e_370.html#organization; Auditor General Act, RSC, 1985, c. A-17, s. 15.1; The CESD has responsibilities under the Auditor General Act, the Federal Sustainable Act, and the Canadian Net Zero Emissions Accountability Act.

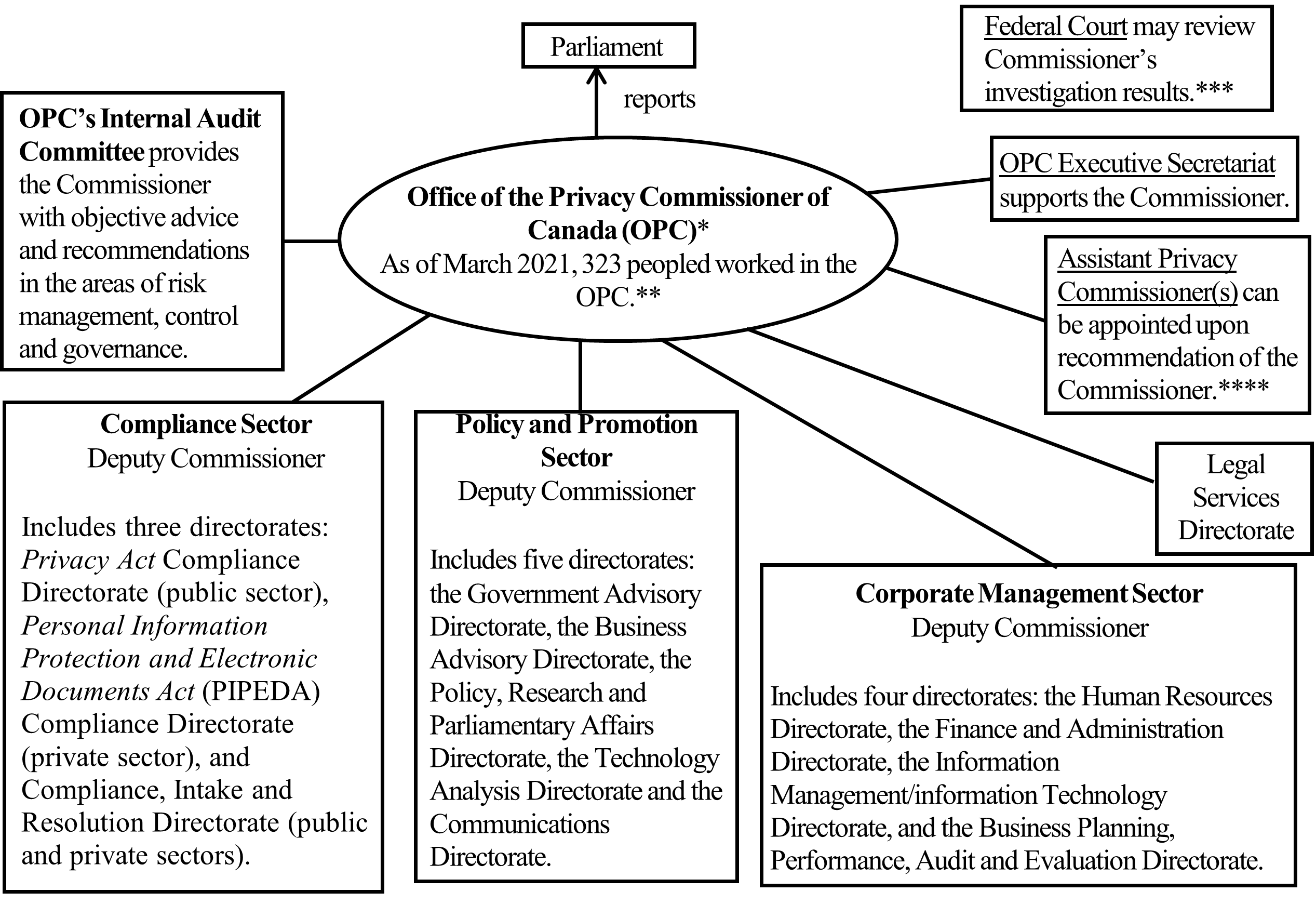

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC)