Departmental Results Report for fiscal year 2020 to 2021

On this page

- From the Ministers

- Results at a glance

- Results: what we achieved

- Analysis of trends in spending and human resources

- Corporate information

- Supporting information on the program inventory

- Supplementary information tables

- Federal tax expenditures

- Organizational contact information

- Appendix: definitions

Alternate formats

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

From the Ministers

We are pleased to present the 2020 to 2021 Departmental Results Report for Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC or the department). This report shines a light on our actions during a landmark year: in March of 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 to be a global pandemic. The rapid spread of the virus throughout the world caused widespread social and economic shock that is ongoing.

This report demonstrates how ESDC helped individuals, communities and families weather the economic and social hardships caused by the pandemic. It also shows how, at the same time, the department advanced its mandate to build a stronger and more inclusive country.

When the pandemic first shuttered the Canadian economy, the Government of Canada moved quickly to support Canadians. The keystone piece of that support was the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), which the department developed in collaboration with the Canada Revenue Agency. The CERB was a lifeline for many suddenly out of work. Nearly 8.9 million Canadians received over $71.7 billion in CERB payments. The Canadian financial sector put forward that this support has helped prevent catastrophic household income loss and has helped keep the economy afloat.

As the pandemic wore on, ESDC made temporary changes to the Employment Insurance (EI) program to better support workers. Later, the department also created three new recovery benefits that would provide continued support to those affected.

However, not everyone who lost income in the spring of 2020 was covered by the CERB or EI. That is why ESDC created the Canada Emergency Student Benefit, which included an extra amount for students with disabilities and students with dependents. To help youth find quality summer jobs, the department expanded the Canada Summer Jobs program. It also provided thousands of opportunities through the Youth Employment and Skills Strategy, especially for youth who face barriers to entering the workplace. ESDC also made additional investments to provide valuable paid student work placements and placed a delay on student loan repayments.

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted marginalized and underserved populations. That is why ESDC implemented the Emergency Community Support Fund. Local and diverse community organizations received funding for over 11,500 projects to help Canadians in vulnerable situations cope with effects of the pandemic.

Reducing and preventing homelessness in Canada remained a priority. The department distributed supplementary funding to Reaching Home recipients. This allowed the homeless-serving sector to protect and support those experiencing homelessness during the pandemic.

ESDC also issued a one-time payment for eligible persons with disabilities to help them deal with pandemic-related costs. In addition, the department established the COVID‑19 Disability Advisory Group to help the Government have a disability-inclusive response to the pandemic.

This past year, the Government helped seniors offset their extra pandemic-related costs through a Goods and Services Tax Credit in April 2020 and a one-time Old Age Security/Guaranteed Income Supplement payment in July 2020. We also funded community projects to help reduce social isolation and serve seniors’ needs.

We know it has been a difficult year for many Canadian families – especially those with young children at home. The closures of schools and daycares forced parents – often women – to take on new roles while balancing working from home. Remote learning also created unexpected additional expenses. To help cover some of these costs, families received a one-time Canada Child Benefit payment of $300. Additionally, in July 2020, the maximum yearly Canada Child Benefit amount was increased once again to keep up with the cost of living.

As we transition toward economic recovery, we aim to build back better. We know that as parents start the process of returning to work, finding affordable, high-quality child care is critical. The department has put in place bilateral agreements with provinces and territories, based on the Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework. This means that providers will be able to offer spaces beyond the 40,000 new spots created, as promised. ESDC also supported Indigenous communities to advance the goals and priorities outlined in the Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care Framework.

Building back better also means making sure that Canadians have the skills they need to do the jobs that are available. ESDC made new investments in an effort to support people experiencing barriers to entering the workforce. In this regard, the department put special emphasis on people trying to enter skilled trades.

The department is committed to pay equity. To facilitate the application of the Pay Equity Act, it developed the Pay Equity Regulations. These regulations will ensure that employees of federally regulated workplaces receive equal pay for work of equal value regardless of their gender. ESDC has also implemented initiatives such as federal anti-harassment and violence legislation and the Roadmap to Future Workplaces project.

If we are going to build back better, we need to do so with a vision for the future. This means a labour market that is resilient and inclusive. It means that people have the skills they need to do the jobs of the future. And it means that people can access the services they need without barriers. Here at ESDC, we brought this vision into our pandemic response, and we will bring it into our recovery.

Finally, we would like to extend our sincerest gratitude to all the employees of ESDC and Service Canada for their hard work and dedication during this difficult year. Thanks to them, Canadians continued to receive urgent and new services, without delay, to help them weather the pandemic. And in the meantime, employees faced enormous hurdles to get things done, while living through the pandemic themselves – sometimes at personal sacrifice. To these employees: we send our sincerest gratitude and appreciation for your role in helping Canadians get through this difficult period.

Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Disability Inclusion, Carla Qualtrough

Minister of Families, Children and Social Development, Karina Gould

Minister of Labour, Seamus O’Regan Jr.

Minister of Seniors, Kamal Khera

Results at a glance

Fiscal year 2020 to 2021 unfolded under the global COVID-19 pandemic, creating unprecedented disruptions to the lives of all Canadians. Throughout the year, Employment and Social Development Canada continued to support Canadians by quickly implementing pandemic response measures. The department developed and implemented many new measures to support Canadians, including:

- the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, which benefited nearly 8.9 million Canadians, from March 2020 to October 2020. Then in the fall, the department implemented 3 new Canada Recovery Benefits. As of March 31st, 2021, approximately 1.9 million Canadians accessed the Canada Recovery Benefit, 370,000 accessed the Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit, and 470,000 accessed the Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit

- the One-Time Payment for Seniors and One-Time Payment for Persons with Disabilities. Both financially supported eligible clients to help them cover additional costs resulting from the pandemic

- the Emergency Community Support Fund, which provided $350 million to community organizations that funded 11,500 projects

- eServiceCanada, a call-back service put in place in March 2020 to replace in-person services, which were temporarily unavailable

The department also provided support through many existing programs, for example, by:

- providing provinces and territories with an additional $1.5 billion through the Workforce Development Agreements. These funds helped Canadians from underrepresented groups and in sectors hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic with training and employment supports, so they could quickly re-enter the workforce

- investing an additional $266.1 million in the Student Work Placement Program. This investment supported the creation of work placements for post-secondary students in vital sectors such as healthcare. These funds helped more students access learning opportunities

- protecting the safety and rights of foreign workers. The department reprioritized applications under the Temporary Foreign Workers Program to focus on key economic sectors and essential occupations. In addition, the department reduced administrative burdens for employers under the program

- to better support workers protection, ESDC inspectors were granted the authority to verify employers’ compliance with new health and safety requirements. The department also increased the number of inspections, improved coordination and information sharing with provinces, and made enhancements to its tip line operations and consulate liaison services

All these measures, and many others included in this report, played an essential role in helping Canadians through the crisis. For example, the department made adjustments to its programs and processes to either simplify access or extend eligibility to benefits. The department also ensured Canadians were kept informed through the 1 800 O-Canada phone line and Canada.ca website.

In addition to supporting Canadians through the pandemic, the department also completed many of its planned activities. Among these are the following, which are detailed in this report:

- modernizing the Canada Labour Code to implement an Administrative Monetary Penalties System

- implementing the Work Place Harassment and Violence Prevention Regulations

- concluding 1-year extension agreements on early learning and child care with all provinces and territories

- expanding the Reaching Home program, aimed at reducing homelessness in Canada to 6 new communities

The Virtual Assistant tool, on Canada.ca, helped Canadians find quick answers to their COVID-19 related questions. Developed in partnership with the Department of Finance and Health Canada, it was used more than 750,000 times by Canadians.

These are just a few of the many activities undertaken by the department, either directly or through partnerships with other organizations. All through this report, you can learn more about the ways in which the department supported seniors, women, youth, homeless people, persons with disabilities, Indigenous people, children and families, Black communities, official language minority communities, workers, employers, newcomers, students, and others.

Operating context

The department operated and undertook all its activities in the particular context of the COVID-19 pandemic in fiscal year 2020 to 2021. The Canadian economy and labour market underwent dramatic changes due to measures put in place to slow the spread of the virus.

Before the pandemic, the Canadian economy and labour market were performing well. The unemployment rate was at, or close to, historical lows for most of 2019 and early 2020. However, the pandemic resulted in a sudden and unprecedented shock that started in March 2020. By April 2020, public health measures to limit the spread of the virus had affected the employment of 5.5 million Canadians. Of these, 3 million lost their jobs. Another 2.5 million were still employed but worked less than half of their regular hours. Groups that faced barriers to labour market participation prior to the pandemic were among those most impacted. These include youth, women, immigrants, Indigenous people, low-wage workers and persons with lower levels of education. Full-time, highly-educated workers experienced far fewer job losses over this period. However, the way this group worked changed almost overnight as the majority switched to teleworking. Accommodation, food services and non-essential retail trade industries with limited ability to telework experienced significant job losses at the beginning of the pandemic. Although the number of workers affected by the pandemic declined throughout 2020 to 2021, to over 500,000 by March 2021, long-term unemployment grew significantly over the course of the 2020 to 2021 fiscal year.

These employment losses and other impacts of the pandemic took a toll on Canada’s economy. Canada’s Gross Domestic Product shrank by 5.4% in 2020, the steepest annual drop in economic output since data were first published in 1961.

Other, longer-term factors present before the pandemic continued to impact Canada’s labour market and economy. These include:

- an aging population that can reduce labour force growth, limit economic growth and increase the likelihood of labour shortages

- the use of new, digital technologies that speed up changes in the labour market. These technologies are making some occupations obsolete, creating new ones and changing the skills needed for many occupations

- efforts to mitigate the impacts of climate change and contribute to the green economy. These efforts continued to play a role in labour market transformation, but uncertainty still remains regarding the precise scope and pace of anticipated change. Employment related to environmental and clean technologies is growing at a faster pace than for the rest of the economy

In addition, the pandemic slowed down the pace of globalization. Travel restrictions, workplace capacity restrictions, and lockdowns reduced the movement of people, goods and services across borders. This contributed to a global supply chain disruption. The pandemic has also created pressures in different parts of the Canadian labour market. For example, it increased the demand for workers in some occupations, such as high-skilled medical workers. At the same time, it reduced inflows of immigrants and temporary foreign workers, which limited their contribution to the Canadian labour market.

Supporting the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic defined Employment and Social Development Canada’s service delivery context. The department’s efforts were focused on maintaining timely and safe access to Government of Canada information, services, and benefits. It established eService Canada to allow clients to access services online, without coming into a Service Canada office. The department also worked to ensure the rapid delivery of new benefits and increased the capacity of its online and phone delivery services. This addressed increased demand for services and health and safety concerns associated with in-person services. At the same time, the department ensured safe access to its in-person offices following temporary closures early in the pandemic. These offices are often the most convenient option for marginalized and underserved individuals to access government assistance.

The department continued to work to ensure service excellence for all Canadians. Here is an overview of what the department accomplished in this regard in fiscal year 2020 to 2021.

Key service achievements

The COVID-19 pandemic had a major impact on the department’s service delivery in fiscal year 2020 to 2021. The department focused on a rapid roll-out of support measures and on maintaining uninterrupted delivery of services to Canadians and community organizations.

At the same time, it continued to advance its ambitious service agenda to ensure service excellence for clients in 3 main areas:

- modernizing the departmental information technology systems, which support online service delivery

- improving the quality of the client service experience and outcomes

- ensuring all eligible individuals can access the department’s services

Technology and systems modernization

Technology underpins the department’s service delivery and enables reliable, accurate, and secure online services. In fiscal year 2020 to 2021, the department made progress in updating technology. For example, it:

- advanced execution of the Benefits Delivery Modernization programme. This key initiative will span over 10 years. It will transform service delivery for the department’s 3 major programs, Employment Insurance (EI), Old Age Security (OAS) and Canada Pension Plan (CPP). In fiscal year 2020 to 2021, the department started activities to improve how services for these 3 programs are delivered. This included launching the development of the common benefit delivery platform on which these benefits will be delivered. The launching required building the foundational business processes, operating model, technology and cloud infrastructure. All these elements needed to be flexible enough to design, onboard, manage, and securely administer these benefits in the future.

- implemented the Electronic Social Insurance Number service which now allows clients across Canada to get a Social Insurance Number online, without going to a Service Canada Centre

- developed its Security Policy Suite to better protect Canadian’s personal information

- supported migration of 2 identity business lines, the Social Insurance Number and the Registration and Authentication telephone services, to a new platform in April and June 2020.

- allowed clients to complete their Declaration of Attendance at School or University online and upload proof of enrolment to renew CPP Children’s Benefits

- moved forward on the design and implementation of Robotics Processing Automation (RPA) to automate routine, repetitive and operational tasks for EI, OAS and CPP operations. This automation allows client service agents to focus on tasks that require human intelligence and decision-making capacity. This has resulted in more timely support and personalized services for clients

- Supported EI and Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) processing, by implementing the use of RPA, which allowed reallocation of human resources. For example, every year there are EI tax slips (T4Es) that cannot be issued automatically by the system for various reasons. In fiscal year 2020 to 2021, the volume of manually processed T4Es was over 60 times higher than normal. The RPA initiative supported the department in meeting its obligation of having all T4Es mailed out by the last day in February

- enabled Canadians to submit their documentation electronically for the JobBank, CPP-Disability, Apprenticeship Grants and Employment Insurance programs. In fiscal year 2020 to 2021, 52,886 documents were uploaded electronically compared to 82 in the previous year. Clients can now upload supporting documentation for CPP-Disability applications through their My Service Canada Account. This can be done for both the online and paper versions of the application form. Clients can now also make an online request to have their application reviewed

Improving the client service experience and outcomes

Service modernization and investments in technology improve the client service experience. Making services user friendly and intuitive, easy to access, and supported across channels, improves how clients experience their interactions with government and increases public trust. For a citizen-centred organization, responding to emerging client needs and providing an excellent service experience is the ultimate objective. This year, the department:

- reacted rapidly to the COVID-19 crisis and enhanced its call centre services to support Canadians during the pandemic by:

- creating a new Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) Virtual Call Centre. This call centre responded to general inquiries and provided information related to CERB eligibility and the application process. At its peak, the CERB Virtual Call Centre had more than 1,500 staff. Between April and September 2020, nearly 1.2 million calls were answered

- increasing the number of agents from 1,100 to 3,000 agents in its Employment Insurance (EI) Call Centres to reduce wait times

- launching a call centre, on behalf of the Public Health Agency of Canada, to monitor quarantine requirements of travelers entering Canada. Agents made calls to close to 2 million travelers. In addition, more than 1.1 million automated calls were made to advise travelers of quarantine requirements. There were also over 800,000 automated survey calls made to travelers, to confirm that they were following quarantine requirements. Close to 1.3 million inbound calls were received from travelers to report that they arrived at their place of quarantine and to complete their daily COVID-19 symptom self-assessment

- providing telephone services for the new One-Time Payment to Seniors, by answering 75,000 calls through the Pensions Call Centres

- designed, tested and launched a self-service option for the Pensions Call Centres’ Interactive Voice Response system. This allowed clients to self authenticate using their Social Insurance Number and date of birth to receive information on their most recent payment amount and date, or their application status. Nearly 1.25 million calls were answered in fiscal year 2020 to 2021. Client surveys showed that the client experience was improved by this enhancement to the Interactive Voice Response system

- modernized grants and contributions programs by focusing on 4 key areas: client experience, efficiency, innovation and stewardship. This made it easier for organizations to apply for grants and contributions. This included:

- streamlining application processes by publishing a new call for proposal calendar to inform clients when they can apply for funding

- launching a survey to measure client’s satisfaction and expectations of grants and contributions programs

- updating service standards to reduce the time required to acknowledge receipt of proposals, issue payment, and notify applicants of funding decisions

- introducing flexibilities for grants and contributions programs to support community organizations in maintaining critical services

- completed consultation with partners to ensure the blueprint for the Social Insurance Register modernization would meet expectations

Reaching all Canadians

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted that government services must be available to everyone. This is especially important for marginalized and underserved clients, who even under normal circumstances, experience barriers in accessing government services. The department made its services more accessible to marginalized and underserved populations by:

- developing the Reaching All Canadians Strategy to improve service delivery outcomes for all clients. This includes informing marginalized and underserved populations about Government of Canada programs, services and benefits, and how to access them

- implementing an Outreach Support Centre to provide services to Indigenous communities and other marginalized and underserved clients. These can be clients with no reliable access to the internet or who experience other barriers to accessing service

- simplifying and updating the language used in grant and contribution program web pages related to program delivery. These pages now use plain language and are fully accessible

- facilitating and ensuring the flow of funding to marginalized and underserved Canadians by simplifying requirements for grant and contribution recipient organizations

- continuing to simplify its web content. The web pages for ESDC’s major benefits programs drive 90% of traffic. They are, on average, at a grade 6 reading level. The rest of ESDC’s information-focused pages average grade 9 reading level

- improving ESDC’s digital client experience, including by working earlier with policy and programs to embed client experience early in content and program design, and by improving client journeys across service channels

- assisting clients with vision or hearing impairments who visit Service Canada Centres through various devices to improve their service experience

- reaching out to more than 350 targeted contacts with Indigenous communities and 425 contacts with senior organizations in the Atlantic region. The region also reached out to 1,000 contacts with disability organizations, 70 contacts with Black community organizations and 1,200 contacts with newcomers and homeless services organizations. These organizations were offered information and access to services. These included programs such as skills and employment training, New Horizons for Seniors and Canada Summer Jobs

Service Canada regional service delivery

Regions played a pivotal role in supporting Canadians through the pandemic. They shifted their activities to make sure marginalized and underserved groups had information on, and access to, government programs, services and benefits. Among the key marginalized and underserved groups are Indigenous people, Canadians living in rural and remote areas, employers and grant and contribution recipient organizations. Regions also carried out programming to help employers and Canadians across the country during the pandemic. This year, regions:

- provided Indigenous Elders and seniors with assistance to fill-out forms and submit documents to receive government supports

- worked with the National Defence Army Rangers to distribute business cards and posters. These cards provided the Service Canada Outreach Support Centre phone number to residents of Hatchet Lake in northern Saskatchewan

- proactively provided information on COVID-19 special measures, available supports, programs and services to organizations. This included 507 Indigenous communities and 1,803 community partners in the Western Canada and Territories (W-T) region

- partnered with the Canada Revenue Agency and the Kativik Regional Government, to provide virtual services, by phone or computer, to 11 of the 14 Inuit communities in Nunavik. In total, 28 clients used this service

- worked with employers to set up 1,887 Work-Sharing agreements that helped avoid layoffs and protected 24,374 jobs in the W-T region. This was an increase from 189 agreements in the previous year

- held over 80 virtual information sessions in Quebec to inform businesses about the Work-Sharing Program and the temporary measures put in place during the pandemic. These measures relaxed eligibility requirements for employers and allowed for the extension of Work-Sharing Agreements. Over 200 businesses were reached through these sessions

Results achieved in specific regions

Western Canada and Territories

- the region provided guidance to Alberta’s Ministry of Children’s Services on the electronic Social Insurance Number application process. The ministry is now using this process to apply directly online to obtain Social Insurance Numbers for children in care

- the region also partnered with the Northern Lights School Division to provide students with information on obtaining a Social Insurance Number

- program officials transcribed applications received orally from New Horizons for Seniors applicants in remote and lower capacity communities. This resulted in reducing barriers to access the program. The program also translated marketing materials into Indigenous languages and into Inuktitut. Both of these efforts resulted in an increase of applications in Nunavut from 8 in fiscal year 2019 to 2020, to 16 in fiscal year 2020 to 2021. During the same period, in the Northwest Territories, it increased from 23 to 34, and in the Yukon, from 14 to 24

Ontario region

- the region piloted tools, chosen in consultation with individuals who have lived experience with disabilities. These will help clients navigate and communicate with Service Canada Centre staff. This included tactile flooring, a textured ground surface to guide clients who are visually impaired. TalkPerfect has also been put in place to amplify speech and minimize background sound for both the client and Service Canada agent

- the region provided community-based virtual services to reduce client wait times and maximize Service Canada Centres' capacity. This service connects clients to a virtual Citizen Service Officer by video chat

Quebec region

- to facilitate the error-free issuance of social insurance numbers (SIN) to temporary foreign workers (TFWs), the region carried out an electronic Social Insurance Numbers (SIN) issuance strategy and organized clinics at key locations, avoiding the trip to Service Canada Centres. In total, the Quebec Region issued 12,000 SIN to TFWs

- the region attended le Salon des aidants et des aînés de la Mauricie and received 124 virtual visits, compared to an average of 74 visits amongst other kiosks

Atlantic region

- the region worked with the Labrador Aboriginal Training Partnership. This allowed approximately 20 Indigenous clients from Labrador to acquire in-person, underground miner training during the pandemic

- the region led the Death Notification Proof of Concept initiative for the Canada Pension Plan Service Improvement Strategy. In total, 193 death notifications were submitted electronically from funeral homes to Service Canada. Funeral homes requested to continue this online service

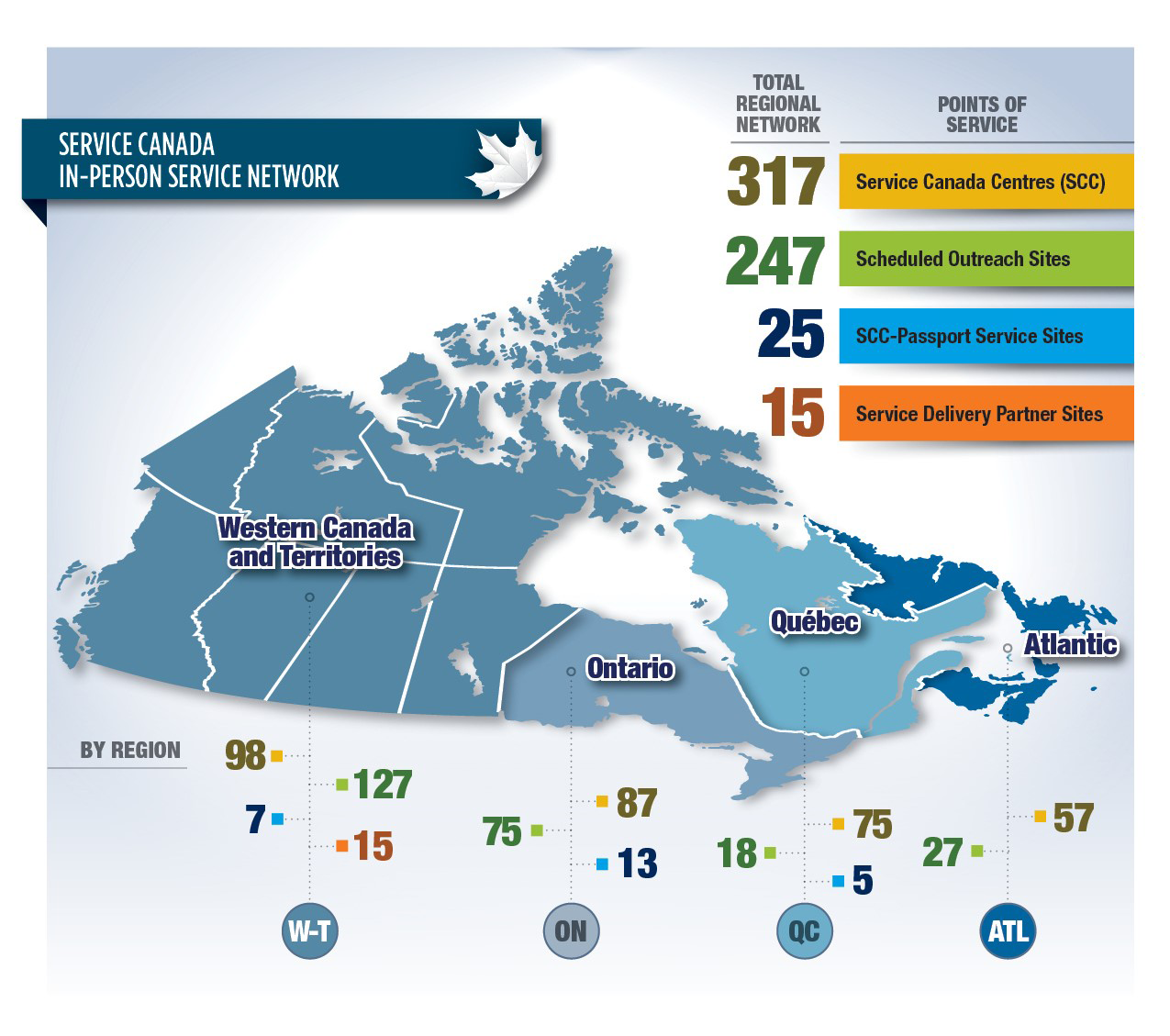

Text description of Figure 1:

Service Canada Centres

- Western Canada and Territories: 98

- Ontario: 87

- Québec: 75

- Atlantic: 57

- Total: 317

Scheduled outreach sites

- Western Canada and Territories: 127

- Ontario: 75

- Québec: 18

- Atlantic: 27

- Total: 247

Service Canada Centres - Passport service sites

- Western Canada and Territories: 7

- Ontario: 13

- Québec: 5

- Atlantic: 0

- Total: 25

Service delivery partner sites

- Western Canada and Territories: 15

- Ontario: 0

- Québec: 0

- Atlantic: 0

- Total: 15

Information in this figure is valid as of March 31, 2021. Note that 310 Service Canada Centres had been reactivated as of March 31, 2021.

For more information on Employment and Social Development Canada’s plans, priorities and results achieved, see the “Results: what we achieved” section of this report.

Results: what we achieved

Social development

Description: to increase inclusion and opportunities for Canadians to participate in their communities.

Results

Access to early learning and child care is increased

Pandemic-related measures

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of access to child care to the functioning of Canada’s economy. Therefore, the department added flexibility to its bilateral early learning and child care agreements with provinces and territories. This helped them to respond to the unique demands flowing from the pandemic. The department also provided $625 million in emergency pandemic support to provinces and territories for the child care sector through the Safe Restart Agreements.

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted early learning and child care in Indigenous communities. In response, the department put in place a temporary measure to spend the Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care program funds. This measure enabled Indigenous leaders to provide alternative program and service delivery options to children and families impacted by the pandemic. The department also distributed $120.7 million in additional funding to help Indigenous early learning and child care facilities adapt to public health measures.

Planned commitments and other achievements

Early learning and child care

The department signed one-year extensions of existing bilateral agreements on early learning and child care (ELCC) with all provinces and territories. These agreements provide for a total federal investment of $400 million for fiscal year 2020 to 2021.

To improve data and to do research to help measure progress, the department completed 22 collaborative projects with Statistics Canada to help identify data gaps, inform policy development and decision-making. These include 4 data development and collection projects, such as the 2020 Survey on Early Learning and Child Care Arrangement. They also include research and analysis reports on a number of priority topics related to ELCC and Indigenous ELCC. The department also undertook 2 dissemination projects, including the development of the ELCC Information Hub.

Indigenous early learning and child care

The department supported Indigenous communities through its partnership tables with First Nations, Inuit and the Métis Nation. These partnership tables advanced goals and priorities stated in the Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care Framework. This resulted in:

- funding to First Nations communities for a range of early learning and child care needs

- continued funding to improve existing early learning and child care services in Inuit Nunangat

- the establishment of new Métis-specific early learning and child care programs, services and supports

- increased support to the Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities program to enhance programming in urban and northern communities

As well, a total of 13 Quality Improvement Projects received funding to support Indigenous-led best practices and advance foundational elements of Indigenous ELCC.

Barriers to accessibility for people with disabilities are removed

Accessible Canada Act implementation

The department published the proposed Accessible Canada Regulations for public comment. To encourage participation, the department provided 5 technical briefings to stakeholders and held meetings with key disability organizations. The pandemic made it difficult for the disability community to take part in this process. To accommodate this community, the department provided a longer comment period on the draft regulations. This gave more time for the disability community to participate in the process.

In support of this implementation, the Accessibility Secretariat co-designed a project with the department’s Innovation Lab. This project included workshops with a diversity of people with disabilities and representatives from federally-regulated industries. They came together to create recommendations, prototypes and guidance material related to the act. The department listened to the stories of 127 participants from across Canada. It then developed 10 prototypes to support implementation of the act. These prototypes included proposed models for engagement and consultations, visual design for accessibility, planning and reporting with accessibility considerations, and performance measurement for accessibility.

In addition, the department:

- funded projects aimed at informing and engaging the disability community, Indigenous governments and organizations, and regulated entities on the application and implementation of the act

- supported projects through the Social Development Partnerships Program – Disability component to support disability-related organizations during National AccessAbility Week (NAAW) 2020. These supports contribute to raising awareness of the importance of accessibility and inclusion in different sectors, communities and at the national level. As part of NAAW 2020, the department posted a video to highlight the work of sign language interpreters during the pandemic

- provided support for the establishment of Accessibility Standards Canada. This support included coordinating the appointments of all members of the Board of Directors. It also included providing legislative interpretation and advice. As a result, the organization is now a fully operational, independent corporation, within the department’s portfolio

- collaborated with provinces and territories, through the Open Forum on Accessibility, on an environmental scan of federal, provincial and territorial service animal requirements. The goal was to better understand what is needed to provide a consistent travel experience for persons with disabilities throughout Canada

- funded 3 national Indigenous organizations so they can consult their member communities on how to advance accessibility on reserve. This will ensure that the implementation of the Accessible Canada Act is based on diverse Indigenous voices. It will also ensure that this implementation meets the needs of Indigenous Canadians living on reserve

To measure progress on accessibility, the department worked with Statistics Canada to develop an Accessibility Data Hub. The hub is hosted on the Statistics Canada website. It gathers constantly updated federal data related to accessibility. This data is available to all Canadians including persons with a disability, the organizations that advocate on their behalf, Indigenous persons and academia. The 2 organizations also collaborated to launch the Survey on Accessibility in Federal Sector Organisations.

The department shared the report on Accessibility of Electronic Payment Terminals with provincial and territorial partners. It also engaged them to explore options for collaboration and to encourage action to enhance accessibility in areas under their jurisdictions. The department also shared the report with stakeholders and published a summary to raise awareness and encourage collaboration across the stakeholder community. The report identifies barriers associated with electronic payment terminals and outlines options and considerations for improving their accessibility.

Enabling Accessibility Fund

Under the Enabling Accessibility Fund, the department funded 383 projects (272 under the Small projects stream and 111 under the Youth Innovation stream). A change to the program allowed the department to fund up to 100 per cent of project costs, for a maximum of $100,000 per project. In past years, applicants had to obtain some of their funds from other sources. Because of the removal of the leveraging requirement, the department provided more funding for each project. As a result, it was only able to fund 383 projects, instead of the 430 projects originally targeted for in fiscal year 2020 to 2021.

The Youth Innovation component of the Enabling Accessibility Fund received a record number of 238 applications and was able to fund 111 youth-led projects. These projects fulfill 2 objectives. They provide greater access for persons with disabilities to community spaces and workplaces. They also allow youth to play a leadership role by having a direct impact in the lives of persons with disabilities.

Homelessness in Canada is prevented and reduced

Pandemic-related measures

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the department distributed over $400 million in supplementary funding to Reaching Home funding recipients. This allowed the homeless-serving sector to protect and support those experiencing or at risk of homelessness. This included preventing COVID-19 transmission in shelters and other forms of accommodation by:

- reducing overcrowding in shelters and other congregate living settings. This included enabling physical distancing, enhancing cleaning and putting other emergency health and safety measures in place

- establishing isolation spaces

- securing housing and other forms of accommodation

- focusing on homelessness prevention initiatives. This included short-term financial assistance to cover rent arrears grocery cards, landlord-tenant mediation, problem solving with neighbours and helping with budgeting

In November 2020, the government announced an additional $299.4 million for fiscal year 2020 to 2021 through the Fall Economic Statement. The goal of this investment was to further help homeless-serving organizations reduce the impact of COVID-19 for those experiencing homelessness in their communities. It also aimed at preventing at-risk Canadians from becoming homeless by supporting targeted interventions. Such interventions enable people to stay housed and creates more permanent housing solutions.

Planned commitments and other achievements

Reducing homelessness in Canada

The department expanded Reaching Home to 6 new designated communities, 3 in British Columbia and 3 in Ontario. In fiscal year 2020 to 2021, the program provided $581 million, in total, to:

- 64 communities (urban centres)

- various rural and remote areas across Canada

- the 3 territorial capitals: Iqaluit, Yellowknife and Whitehorse

- 30 Indigenous communities (mostly urban areas)

Reaching Home also provided $9 million through the Community Capacity and Innovation stream to 81 communities. This included funding to support the national delivery of training and technical assistance for communities. It also included funding them directly to:

- design and implement local coordinated access systems that streamline access to services for people with housing challenges

- foster innovation in the homelessness sector

Reaching Home continued to work closely with organizations to reduce Indigenous homelessness at the community level. The program provided funding to ensure that the unique needs of First Nations, Inuit and Métis Nation were met.

Poverty in Canada is reduced

The department provided policy, administrative and logistical support to the National Advisory Council on Poverty. This support enabled the council to deliver on its mandate to provide advice on poverty reduction in Canada through their first report. Building Understanding: The First Report of the National Advisory Council on Poverty was tabled in Parliament on February 23, 2021.

The department also supported the council in continuing a dialogue with Canadians on poverty. This support helped the council to undertake 15 national and 8 regional engagement sessions. These sessions gathered together over 600 stakeholders, academics, experts, provinces and territories and persons with lived expertise on poverty and its many dimensions. What was heard during these engagement sessions will help to form the council’s second annual report.

The department worked with Statistics Canada to review Canada’s Official Poverty Line, based on the Market Basket Measure (MBM). Such reviews are mandatory under the Poverty Reduction Act. They ensure that the poverty line reflects an up-to-date basket of goods and services that represent a modest, basic standard of living in Canada. Periodic reviews of the MBM help better track poverty in Canada over time.

The department worked with Statistics Canada and territorial governments to expand the Canadian Income Survey to Canadians in the territories. This expansion will provide valuable statistics on the income of persons living in the 3 territories and will improve the measurement of poverty in Canada’s North. The department has also been co-developing indicators of poverty and well-being, from First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Nation perspectives, with National Indigenous organizations. These indicators will reflect the multiple dimensions of poverty and well-being experienced by Indigenous peoples.

Not for profit organizations, communities and other groups have an enhanced capacity to address a range of social issues such as the social inclusion of people with disabilities, the engagement of seniors and support for children and families

Pandemic-related measures

The department implemented the Emergency Community Support Fund which provided $350 million to local community organizations who support marginalized and underrepresented populations. Over 11,500 projects received funding in diverse communities across the country.

The New Horizons for Seniors Program reduced the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on seniors by:

- allowing organizations to use approved funding to address pandemic-related issues instead of for original objectives

- collaborating with United Way/Centraide Canada to deliver $9 million to more than 900 community organizations

- distributing an additional $20 million to more than 1,000 projects. These community-based projects aimed to reduce isolation, improve seniors’ quality of life, and help seniors maintain social support networks

The department provided additional funding to national disability organizations to support communication and engagement activities in response to the pandemic. In total, 27 organizations accessed these additional funds ($927,000 in total).

Planned commitments and other achievements

Supporting seniors

The department funded over 2,600 projects across Canada under the Community-Based stream of the New Horizons for Seniors Program (NHSP). These projects helped seniors benefit from, and contribute to, the quality of life in their communities through active living and social activities. Funded organizations reported an increase in their capacity to:

- provide activities to seniors

- recruit volunteers

- develop partnerships

- improve facilities that support seniors’ initiatives in their communities

Through the pan-Canadian stream of the NHSP, the department funded 24 projects:

- 22 projects brought together different community organizations to meet seniors’ growing social needs

- 1 national project funded a knowledge hub

- 1 project funded other projects aimed at LGBTQ2+ seniors in 3 Canadian cities

In total, an estimated 661,500 seniors benefitted from the NHSP in fiscal year 2020 to 2021.

Enhanced capacity to address social issues

The department funded over 680 social purpose organizations (SPOs) through the Investment Readiness Program. Program funding helps social purpose organizations build the skills they need to seek loans or other forms of financing to grow their social impact. This way, they can help solve social and environmental challenges. Funded organizations are addressing pressing issues such as:

- including marginalized Canadians in the workforce (32% of funded SPOs) for example through supportive employment opportunities

- supporting Indigenous people (27% of funded SPOs), for example by developing an Indigenous culinary arts program and catering business

- including people with disabilities (22% of funded SPOs), for example by creating an organization to train and educate businesses on meeting their obligation under the Accessible Canada Act

- supporting children and youth (18% of funded SPOs), for example by expanding an organization that offers French-language childcare to francophones in official language minority communities

- other pressing social and environmental issues (11% of funded SPOs)

ESDC is moving forward with the implementation of the Social Finance Fund, designed to support the growth of Canada’s social finance market. A Call for Expression of Interest (EOI) to become a social finance wholesaler for the Social Finance Fund was launched this fiscal year, distributing up to $220 million of the fund in the next two fiscal years.

A Social Innovation Advisory Council will also be established. The council will provide strategic advice and expertise to the Government of Canada. This will support the implementation of the Social Innovation and Social Finance Strategy and the growth of social purpose organizations.

Supporting children and families

The Children and Families component of the Social Development Partnerships Program benefitted 421,597 marginalized and underrepresented Canadians, including children, youth and adults. As well, every dollar received from the program allowed community organizations to raise an additional $2.65 from other partners.

Supporting Black communities

Under the “Capital Projects” stream of the Supporting Black Communities Initiative, the department led a $3 million call for proposals. The call was open to Black-led, not-for-profit organizations seeking to improve their workplaces and community spaces. These organizations had an opportunity to obtain up to $100,000 per project to fund capital projects.

The department also established an intermediary network with 3 high-capacity organizations. This intermediary network supports the ‘For Us By Us’ philosophy, as communicated by stakeholders in Black communities. The department is empowering representative organizations to determine funding distribution, based on their grassroots knowledge of community needs.

The intermediaries held a separate call for proposals to distribute funding to grassroots Black-led organizations. This funding will allow these organizations to enhance their capacity in the areas of improved governance, financial management and diversification of funding sources. This greater capacity will support them in delivering services and supports to Black communities.

Supporting persons with disabilities

In fiscal year 2020 to 2021, there were 87 projects underway through the Social Development Partnership Program – Disability component.

This was the second year of 3-year funding agreements with 28 national disability organizations. Under these agreements, the department provided a total of $5.8 million to increase the social inclusion of persons with disabilities.

Additionally, 12 regional affiliate organizations of Inclusion Canada received a combined $1.5 million. This funding allowed them to support the social inclusion of persons with intellectual disabilities.

The department also funded projects that:

- developed tools and resources in priority areas of the Accessible Canada Act. These are areas like accessible service, design and delivery, and communication

- promoted accessibility and inclusion in communities and workplaces across Canada during National AccessAbility Week

- engaged the disability community on how the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is implemented

- supported the production of alternate format materials for persons who are unable to read conventional print

- funded LIFT Philanthropy Partners to increase the capacity of 8 disability organizations that work on social inclusion and improving employment outcomes for persons with disabilities

- helped make disability organizations stronger by giving youth a chance to be leaders

- engaged national Indigenous organizations on key issues about barriers faced by Indigenous persons with disabilities

- found new ways to improve the financial security of persons with disabilities

Supporting sustainable development

The department led the development of Moving Forward Together – Canada’s 2030 Agenda National Strategy. Launched in February 2021, the strategy aims to create an environment enabling all segments of society to participate in advancing the sustainable development goals. The strategy will help build a Canada that is peaceful, prosperous, and sustainable, where no one is left behind.

Through the Sustainable Development Goals Funding Program, the department provided 46 grants and 12 contributions to organizations to support them in advancing the sustainable development goals. These organizations include not-for-profits, provinces and territories, municipalities, academia, the private sector, and organizations that work with Indigenous and racialized communities.

The department also funded 3 national Indigenous organizations: the Assembly of First Nations, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, and the Métis National Council. The goal was to raise awareness of the sustainable development goals among First Nations, Métis Nation and Inuit and the integration of indigenous perspectives into Canada’s implementation of the 2030 Agenda.

Clients receive high quality, timely and efficient services that meet their needs

In fiscal year 2020 to 2021, the department brought changes to the Enabling Accessibility Fund and simplified the application process. This, combined with pandemic-related flexibilities, allowed organizations to get funding for projects in an average of 12 weeks. In comparison, the average processing time was 32 weeks in previous years.

Gender-based analysis plus

The department makes great efforts to increase inclusion and opportunities for Canadians to participate in their communities. These efforts align with the pillars of the Gender Results Framework. They align more specifically with the Economic Participation and Prosperity pillar, and the Poverty Reduction, Health and Well-Being one. These pillars aim to promote equal and full participation in the economy. They also support the reduction of poverty and better health outcomes for diverse groups of women, men and non-binary people.

Here are a few examples of how the department supports the Poverty Reduction, Health and Well-Being pillar.

The homeless population includes a variety of at-risk populations and includes a number of at-risk groups. Given this context, Reaching Home provides flexibility to communities to design and deliver systems that reflect local needs and priorities.

Communities are expected to work toward 5 core Reaching Home outcomes. Progress with reaching homelessness reduction targets for each outcome is documented and shared through annual Community Homelessness Reports, which began this year. These data will allow for a fuller understanding of results achieved at the community level.

Many projects under the New Horizons for Seniors Program focus on reaching the most marginalized and underrepresented senior populations. Funding recipients targeted socially isolated seniors. Almost 33% targeted visible minority seniors. Funded recipients also targeted other marginalized and underrepresented seniors including immigrant seniors (26%) and ethno-cultural seniors (26%). Overall, these projects benefited more senior women (56%) than senior men. Senior women represented (63%) of the seniors who volunteered in the implementation of these projects. Some (68%) of seniors who volunteered as mentors to other seniors and youth, were female seniors.

Here are a few examples that support both pillars.

The lack of affordable and accessible early learning and child care services is a major barrier for full economic gender equality. Child care availability and cost strongly impact mothers’ decisions to enter or remain in the labour market or school. This is especially true for racialized women, single mothers, and mothers of pre-school age children. Helping families to access child care will allow them to build a better future. Many parents, particularly women, will be able to enter or return to the labour market. They might also further their education or open a new business. All this will contribute to their well-being and to Canada’s economy.

The Investment Readiness Program supported the inclusion of women and other diversity groups. Through the Social Innovation and Social Finance strategy, the program:

- built awareness of social innovation and social finance amongst social purpose organizations (SPOs) that are led by, or that support, women and other diversity groups

- increased investment readiness of social purpose organizations that are led by, or serve, women and other diversity groups

In total, 24 recipients delivered the Investment Readiness Program (IRP) through grant and contribution agreements. Of those recipients, 8 had projects that supported access to the program for social purpose organizations serving women and other diversity groups. This ensured that these populations had access to, and were able to receive support from, the program.

IRP recipients re-granted funds to 680 social purpose organizations to support them in building their investment readiness. An increased investment readiness allowed women-led and women-focused SPOs to develop new skills from the program. This will help them in obtaining the financing needed to develop and scale innovative solutions. With this financing, they will be able tackle the pressing challenges facing communities across Canada. Of the 680 social purpose organizations that received grants from the program through the IRP:

- 180 (26.5%) supported women and girls

- 338 (49.7%) supported at least one diversity group (Indigenous people, racialized people, people with disabilities, LGBTQ2+)

- 517 (76%) built their capacity to access social finance to serve women and other diversity groups

The Children and Families component of the Social Development Partnerships Program funded projects that benefitted more than 422,597 marginalized and underrepresented Canadians. This included women, persons with disabilities, Indigenous people, new immigrants, ethno-cultural communities, LGBTQ2+ community and official language minority communities. Funded organizations increased their capacity to recruit volunteers, engaged marginalized and underrepresented Canadians in consultations, and provided more services to these groups. They also increased their knowledge and awareness of the needs of marginalized and underrepresented Canadians.

Experimentation

The Accessible Canada Act requires regulated parties to develop accessibility plans to identify, remove and prevent barriers to accessibility. The department worked with Statistics Canada to explore the use of artificial intelligence to rapidly scan accessibility plans that will be developed. The scan spots indicators that measure progress in advancing accessibility through the removal of barriers to accessibility. Limitations around the algorithms were encountered during initial testing and are being addressed to increase its effectiveness at gathering relevant data. Using technology to efficiently mine large data sources for specific information can be applied to a range of research, policy, program and compliance activities.

Feedback from organizations and persons with disabilities applying to the Enabling Accessibility Fund indicated that:

- the process was complex for small organizations (requirement of multiple quotes, budget template)

- decisions were not timely

- the results produced resulted in some projects addressing accessibility issues better than others

In response, the department introduced a flat rate model to calculate costs of commonly funded small projects. This reduced the administrative burden on clients by requiring less information to apply for funding. It also facilitated the department’s assessment of projects. Project officers had less information to review and could make consistent decisions for eligible project activities and project funding amounts. These changes resulted in 58% of organizations submitting a complete application compared to 10% in the past. Lessons learned from this initiative will inform the next phase of the flat rate model under the program.

2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

In fiscal year 2020 to 2021, Reaching Home contributed to the following United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):

- No Poverty (SDG 1) - Supports the most marginalized and underrepresented Canadians in maintaining safe, stable and affordable housing. It also aims to reducing chronic homelessness nationally by 50% by 2027 to 2028

- Gender Equality (SDG 5) - It helps communities meet the needs of at-risk populations, including seniors, youth, women, gender diverse individuals, people fleeing violence, families, Indigenous peoples, LGBTQ2+ individuals, veterans, racialized Canadians and newcomers to Canada

- Reduced Inequalities (SDG 10) - Helped 30 communities and 7 regions to respond to the needs of Indigenous people who are at risk of, or are, experiencing homelessness. In addition, it introduced a distinctions-based funding stream to ensure the unique needs of First Nations, Métis Nation, and Inuit are met

- Sustainable Cities and Communities (SDG 11) - Ensured access to adequate, safe and affordable housing, particularly for some of the most at-risk groups. It also aims to reduce chronic homelessness by 31% by March 2024

The Supporting Black Canadian Communities Initiative contributes to the following SDG:

- Reduced Inequalities (SDG 10) – The capital assistance provided is intended to support capacity building in community organizations. This will help them better achieve their mandate to support Black communities

The New Horizons for Seniors Program contributes to the following SDG:

- Good Health and Well-Being (SDG 3) - It increases the social participation and inclusion of seniors in their communities. Increased social inclusion is directly linked to improved mental health. Some 72% of funded recipients reported that the NHSP funding enabled them to increase the social participation and inclusion of seniors in their communities

The Investment Readiness Program supports social purpose organizations that contribute in various ways to the following SDGs:

- No Poverty (SDG 1)

- Good Health and Well-Being (SDG 3)

- Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG 8)

- Reduced Inequalities (SDG 10)

- Sustainable Cities and Communities (SDG 11)

The Accessible Canada Act requires parties that are subject to the act to identify, remove and prevent barriers to accessibility in 7 priority areas. Priority areas include transportation, the built environment, employment, communication, information and communications technology, procurement, and programs and services. It will be easier for persons with disabilities to secure and retain employment, access government programs and services, receive information, access public buildings and transportation, etc. As such, the act contributes to the following SDGs:

- No Poverty (SDG 1)

- Zero Hunger (SDG 2)

- Good Health and Well-Being (SDG 3)

- Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG 8)

- Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure (SDG 9)

The Enabling Accessibility Fund (EAF) contributes to the following SDGs:

- Good Health and Well-Being (SDG 3) - Past EAF-funded projects have included multisensory rooms which support people with cognitive and/or mental health disabilities. These rooms have grown in popularity over the past 3 years and support the provision of mental health services in community spaces

- Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG 8) - By improving accessibility in workplaces and community spaces, the program supports the labour market integration and community involvement of people with disabilities

- Reduced Inequalities (SDG 10) - The EAF program supports the social, economic, and political inclusion of people with disabilities. It does so by removing barriers to community involvement and labour market participation. This allows people with disabilities to participate in social activities within their community, access workplaces, and maintain employment

The Early Learning and Child Care program contributes to the following SDG:

- Quality Education (SDG 4) – More specifically, it contributes to the global target 4.2: “by 2030, ensure that all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education”

Results achieved

Departmental result: access to early learning and child care is increased

Performance indicator: number of children in regulated child care spaces and/or early learning programs and number of children receiving subsidies or other financial supports

Target: 40,000

Date to achieve target: March 2020

2018 to 2019 actual results: 40,116 (combined total for both indicators for both fiscal years: 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019)

2019 to 2020 actual results: not available (See note 1 below)

2020 to 2021 actual results: not available (See note 1 below)

Departmental result: barriers to accessibility for people with disabilities are removed

Performance indicator: number of community spaces and workplaces that are more accessible due to Enabling Accessibility Fund funding

Target: 430

Date to achieve target: March 2021

2018 to 2019 actual results: 473

2019 to 2020 actual results: 376

2020 to 2021 actual results: 386 (See note 2 below)

Departmental result: homelessness in Canada is prevented and reduced

Performance indicator: reduction in the estimated number of shelter users who are chronically homeless

Target: 31% reduction from the 2016 baseline estimated at 26,900 shelter users

Date to achieve target: March 2024

2018 to 2019 actual results: not available (See note 3 below)

2019 to 2020 actual results: not available (See note 3 below)

2020 to 2021 actual results: not available (See note 3 below)

Departmental result: not for profit organizations, communities and other groups have an enhanced capacity to address a range of social issues such as the social inclusion of people with disabilities, the engagement of seniors and support for children and families

Performance indicator: for every dollar invested through the Social Development Partnerships Program, amount leveraged/invested by non-federal partners (See note 4 below)

Target: $0.30

Date to achieve target: March 2021

2018 to 2019 actual results: Social Development Partnerships Program - Children and Families: $0.94; Social Development Partnerships Program – Disabilities: $0.32

2019 to 2020 actual results: Social Development Partnerships Program - Children and Families: $0.78; Social Development Partnerships Program – Disabilities: $0.39

2020 to 2021 actual results: Social Development Partnerships Program - Children and Families: $2.65 (See note 5 below); Social Development Partnerships Program – Disabilities: $0.36

Departmental result: clients receive high quality, timely and efficient services that meet their needs

Performance indicator: service standard target for Social Development program priority service, as defined by the Government of Canada’s Policy on Service, was met [Note: service standards can be consulted on Canada.ca.]

Target: 1 out of 1

Date to achieve target: March 2021

2018 to 2019 actual results: 1 out of 1

2019 to 2020 actual results: 100% (See note 6 below)

2020 to 2021 actual results: 1 out of 1

Notes

- results for fiscal years 2019 to 2020 and 2020 to 2021 are not available yet. Compilation of results across the country are based on annual reports provided by provinces and territories in the fall of the following fiscal year. Due to the pandemic, delays have been encountered in the preparation of these reports

- the program funded fewer projects than projected, in part due to the removal of leveraging under the 2020 Small projects component call for proposals (CFP). Prior to the 2020 Small CFP, the leveraging requirement required successful applicants to fund 35% of their project through non-EAF funds. With the removal of funding provided by applicants, the EAF program funded fewer projects. Despite this, the department still achieved 89% of its target

- this indicator is based on the calendar year. There is a 3-year lag in the availability of data

- organizations are encouraged to use the Social Development Partnership Program funding to leverage cash and in-kind investments from other non-federal organizations. This allows the pool of investment brought to bear on any given issue to be increased. Note that for the Disability component, it is no longer mandatory to leverage the Social Development Partnership Program funding. Increased partnerships, through cash and/or in-kind contributions, increases the impact of program funding. It expands the capacity of recipients to build and further their knowledge, understanding and capacity to address complex social issues

- this result is based on partial data.

- this indicator’s target was converted to a percentage for fiscal year 2019 to 2020. The target being expressed as a percentage (instead of as a number) is consistent with applicable service standards. As the target (for fiscal year 2019 to 2020) is expressed as a percentage, the actual result (for the aforementioned fiscal year) is also expressed as a percentage. Result originally indicated in Departmental Results Report for 2019 to 2020 was 94%, but upon further review, the GC Infobase shows a 100% result for the Parents of Young Victims of Crime grant. The result has therefore been modified so that both sources match

| Spending category | 2020 to 2021 Main Estimates | 2020 to 2021 Planned spending* | 2020 to 2021 Total authorities available for use | 2020 to 2021 Actual spending (authorities used) | 2020 to 2021 Difference (Actual spending minus Planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross Spending | 953,560,319 | 953,560,319 | 2,607,464,463 | 2,572,173,843 | 1,618,613,524 |

| Spending in Specified Purpose Accounts | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Revenues netted against expenditures | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Net Spending** | 953,560,319 | 953,560,319 | 2,607,464,463 | 2,572,173,843 | 1,618,613,524 |

Explanation of variances: the main variance between planned and actual spending is due to additional funding received through the Public Health Events of National Concern Payments Act (PHENCPA). The variance is due to in-year funding, for both new and existing programs that was not included in planned spending. This led to actual spending being higher than initially planned.

Notes

* “Planned spending” may differ from Main Estimates as they include the amounts to be spent for the Specified Purpose Accounts (such as Employment Insurance and Canada Pension Plan accounts). These amounts include benefits paid to clients and amounts associated with the payment of these benefits.

** “Net Spending” excludes amounts spent under Specified purpose accounts.

Refer to the department's Financial Framework section for a complete description of the departmental financial profile, including explanation of gross actual and planned spending.

Human resources (full-time equivalents)

2020 to 2021 planned full-time equivalents: 559

2020 to 2021 actual full-time equivalents: 538

2020 to 2021 difference (actual full-time equivalents minus planned full-time equivalents): (21)

Explanation of variances: no significant variance.

Financial, human resources and performance information for Employment and Social Development Canada’s Program Inventory is available in GC InfoBase.

Pensions and benefits

Description: assist Canadians in maintaining income for retirement, and provide financial benefits to survivors, people with disabilities and their families.

Results

Seniors have income support for retirement

Pandemic-related measures

The department implemented the One-Time Payment to Seniors to help them deal with additional costs resulting from the pandemic. This one-time tax-free payment provided $300 to seniors eligible for the Old Age Security (OAS) pension. Seniors eligible for the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS) received an additional tax-free payment of $200. This measure provided a total of $500 to low-income seniors who received both the OAS pension and the GIS. Allowance recipients also received $500. This payment was issued during the week of July 6, 2020.

The department introduced several interim measures to public pensions programs. This made it easier for program recipients to access their benefits. For example the department:

- reduced the number of documents required when applying for benefits

- adjusted the annual reassessment of income-tested benefits in response to the extension of the tax-filing deadline. This allowed low-income seniors to continue to receive their benefits, pending the processing of their tax return

- eliminated the need for an in-person Commissioner for Oaths signature

These changes aimed to ensure that individuals would not experience payment disruptions as a result of missing documentation or information. The department is now assessing which of these adjustments could be adopted on a permanent basis to modernize program delivery.

Planned commitments and other achievements

Old Age Security

In fiscal year 2020 to 2021, the OAS program provided the OAS pension to 6.7 million seniors. It provided the GIS to 2.2 million low-income pensioners, and the Allowances to 80,200 low-income 60 to 64 year-old individuals.

The department has been automatically enrolling individuals in the OAS program since 2013, and in the GIS program since 2017. In fiscal year 2020 to 2021, 3 million individuals had their GIS eligibility reassessed automatically. These individuals continued to receive their benefits without any interruption. The department implemented a temporary measure to maintain GIS benefits for up to an additional 6 months, if income information was unavailable. As of March 2021, around 50% of new pensioners are being enrolled automatically.

Guaranteed Income Supplement earnings exemption

The department enhanced the GIS earnings exemption, which came into effect in July 2020. This enhancement increased the amount of the full exemption from $3,500 to $5,000 of annual earnings. The measure also extended the exemption to self-employment income, and introduced a 50% exemption on the next $10,000 of earnings. As a result, low-income seniors who work are now able to earn more before their GIS benefit is reduced. Therefore, this exemption reduced disincentives to work for low-income seniors.

Proactive enrollment to the Canada Pension Plan

Since April 2020, the department started proactively enrolling eligible individuals aged 70 or older to the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) retirement pension. This decision was made to ensure that individuals do not miss out on the benefits they are entitled to receive. There is no added financial benefit to further deferring the start of their retirement pension after the age of 70. As a result of this measure, nearly 50,000 seniors began receiving the CPP retirement pension to which they are entitled to during fiscal year 2020 to 2021. Approximately $185 million (comprised of retroactive payments as well as ongoing monthly payments) was paid to these individuals. These individuals are now receiving an average of $260 each month from the CPP retirement pension.

People with disabilities and their families have financial support

Pandemic-related measures

COVID-19 had a disproportionate impact on persons with disabilities, who incurred extraordinary expenses during the pandemic. To reduce this impact, the department distributed the government’s One-Time Payment for Persons with Disabilities. This was a one-time, non-taxable payment of up to $600. The majority of eligible Canadians with disabilities received the payment in fiscal year 2020 to 2021. In total, more than 1.74 million Canadians with disabilities have received the emergency support.

Planned commitments and other achievements

Canada Pension Plan Disability

The department continued the Medical Adjudication Quality Assurance Program, which provides analysis and information about the decision process to grant or deny benefits. The results from this program will help inform and enhance policies, procedures and training. It will also provide feedback to individual medical adjudicators on their strengths and areas for improvement.

The department continued to engage with non-profit disability organizations and public programs in other jurisdictions on ways to improve the program. Among the stakeholders consulted were provinces, territories and the International Social Security Association. The department also pursued consultations through the Canada Pension Plan Disability Client and Stakeholder Roundtable.

Canada Disability Savings Program

The Canada Disability Savings Program helps eligible persons with disabilities and their families save for the future. Under this program, the government pays matching grants, as well as bonds, into the Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP) of disabled beneficiaries. As of the end of March 2021, a total of 219,524 RDSPs were opened. Over time, the government has paid $3.15 billion in grants and $1.41 billion in bonds in these RDSPs.

RDSP take-up has been steadily increasing since the implementation of the program. However, this increase slowed down in fiscal year 2020 to 2021 (compared to fiscal year 2019 to 2020). This could be attributed, in part, to pandemic restrictions, which limited the program’s ability to conduct in-person outreach activities. The total value of RDSP assets is now $7.41 billion.

Clients receive high quality, timely and efficient services that meet their needs

The department took measures to improve service delivery. This included increasing access to online applications, and developing new letters for contributors to encourage them to apply online.

The department also completed a pilot that looked at ways to reduce the time to finalize an appeal on a decision. This work used various data and analysis to identify more complex appeal files. The findings will help to improve departmental approaches to addressing appeal files, therefore providing better service to Canadians.

The pandemic presented an opportunity for the Canada Disability Savings Program to rethink its mail-out strategy. Originally, this strategy targeted a small number of jurisdictions where program take-up was low. However, program officials anticipated that the One-Time Payment for Persons with Disabilities would encourage more individuals to apply for the Disability Tax Credit (DTC). That meant that more persons with disabilities would potentially be eligible to open a Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP). These persons could then be eligible to receive the grant and the bond. That offered a great opportunity to inform a larger population of potential RDSP beneficiaries about the program. As a result, the program shifted its original mail-out strategy. The revised strategy targeted all DTC-approved Canadians aged 0 to 49 in every province and territory. The mail-out resulted in increased awareness of the Canada Disability Savings Program among the entire population that was eligible to benefit from it. In March 2021, following this mail-out, 4,988 new RDSPs were registered. This was the third highest amount of new RDSPs registered in a month since the inception of the program.