Evaluation of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program

On this page

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of acronyms and abbreviations

- Introduction

- Key evaluation results summary

- Recommendations

- Program background

- Key findings

- Management response and action plan

- References

- Annexes

Alternate formats

Evaluation of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program[PDF - 2.3 MB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of figures

- Figure 1: Evaluation scope

- Figure 2: Temporary Foreign Worker Program timeline

- Figure 3: Composition of the labour force (2018)

- Figure 4: Total number of temporary foreign worker positions approved (2013 to 2020)

- Figure 5: Total number of temporary foreign worker positions approved, by stream (2013 to 2020)

- Figure 6: Proportion of employers who indicated that the hiring of temporary foreign workers will fill labour shortages, by stream (2011 to 2018)

- Figure 7: Proportion of employers who indicated that the hiring of temporary foreign workers will fill labour shortages, by year and stream (2011 to 2018)

- Figure 8: Average number of applications submitted by survey respondents (unique employers), by stream (2015 to 2020)

- Figure 9: Percentage of respondents who were satisfied or very satisfied with the timeliness of the response to their application (n=505)

- Figure 10: Average number of weeks required before obtaining the Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) result, according to estimates provided by survey respondents (n=353)

- Figure 11: Average number of calendar days required to make a decision on a LMIA application by stream (2012 to 2018)

- Figure 12: Proportion of employers who indicated that Canadians are not interested, available or qualified, by stream

- Figure 13: Percentage of employers who reported that hiring temporary foreign workers improved their organization's ability to do the following, to a large or very large extent (n=288)

- Figure 14: Percentage of respondents who reported that not being able to hire foreign workers had a negative impact on their ability to: stay in business, retain current employees, hire more Canadians, meet the demand for products and services, meet financial targets (in other words revenues and profits), and expand and/or diversify activities

- Figure 15: As a result of not being able to hire foreign workers, did any of the following occur? (n=75)

- Figure 16: Challenges faced by employers who tried to recruit Canadian workers

- Figure 17: Actions taken by Canadian job seekers whose profile was matched with the job posted on the Job Bank (on average between 2015 and 2018)

- Figure 18: Employers attempting to hire Canadians or permanent residents first, by year (2011 to 2018)

- Figure 19: Average top hourly wages by employment of temporary foreign workers

- Figure 20: Proportion of temporary foreign workers, selected industries (North American Industry Classification System subsectors), 2017

- Figure 21: Actions taken by employers for each Job Bank posting matched with the job seeker's profile (average between 2015 and 2018)

- Figure 22: Percentage of temporary foreign worker positions that received positive Labour Market Impact Assessments, by stream (2012 to 2019)

- Figure 23: Provincial median wage among temporary foreign workers versus Canadians, carpenters (2016 to 2019)

- Figure 24: Average starting hourly wages by employment of temporary foreign workers

- Figure 25: Reasons why wages paid to foreign workers were different than those paid to Canadian workers in similar or equivalent positions

- Figure 26: Which of the following have you done as part of your transition plan?

- Figure 27: How successful has the transition plan been in progressively reducing the need for your organization to hire temporary foreign workers?

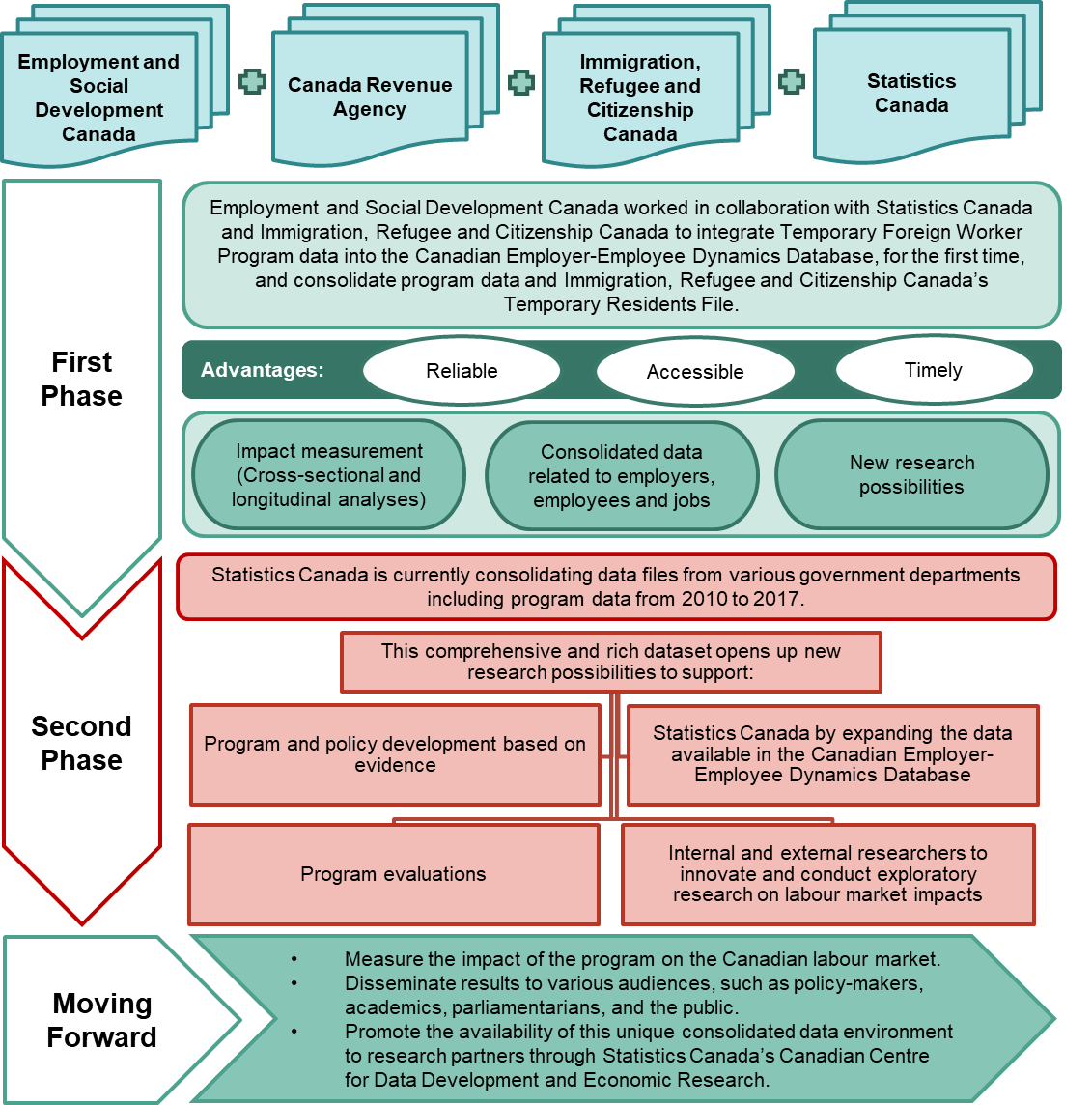

- Figure D-1: Multiple data files from various government departments consolidated and available through the Canadian Employer-Employee Dynamics Database

List of tables

- Table 1: Average Labour Market Impact Assessment processing times for February 2021

- Table 2: Top 4 reasons why Canadian workers were not interested in applying for the positions offered by the employers

- Table 3: Reasons why Canadians were not hired

- Table 4: Proportion of employers who were able to fill positions versus those who could not

- Table 5: Efforts made to try to recruit Canadians after the negative LMIA decision

- Table 6: Program’s negative impacts related to job displacement

- Table 7: Pay differences between Canadian workers and foreign workers

- Table 8: Employers’ preferences to hire foreign workers

- Table 9: Employers’ efforts to hire from underrepresented groups

- Table C-1: Focus groups coverage – additional information

- Table C-2: Percentage of population, sample and surveys completed

- Table E-1: Additional reasons for not hiring: Indigenous Canadians, persons with disabilities, newcomers and vulnerable youth

List of acronyms and abbreviations

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- HUMA

- Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities

- LMIA

- Labour Market Impact Assessment

- NOC

- National Occupational Classification

- SAWP

- Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program

Introduction

The Evaluation of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program was developed based on the knowledge gained from the last evaluation (presented in Annex A) and significant reforms to the program made in 2014.

The evaluation covers the portion of the program that is administered by Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) for the period from 2011 to 2018. However, the most recent data is provided where relevant. It focusses on the following issues:

- labour market shortages and gaps

- employers’ efforts to hire resident labour before applying to the program, and

- impact of the program on wages and displacement

Figure 1: Evaluation scope

-

Text version of figure 1

- Covered by the evaluation

- High-Wage Stream

- Low-Wage Stream

- Primary Agriculture StreamFootnote 1

- Stream to support permanent residency (Express entry)

- Not covered by the evaluation but may be referred to for context

- Global Talent Stream

- Covered by the evaluation

- ESDC’s Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee approved the Evaluability Assessment in April 2018. This includes the evaluation questions presented in Annex B

- The evaluation used 5 lines of evidence:

- a document and literature review

- an administrative data review and analysis

- focus groups

- key informant interviews, and

- a survey of employers

- More details about the evaluation methodology, the lines of evidence and their limitations can be found in Annex C

Key evaluation results summary

Key findings

- The program plays a crucial role in helping Canadian employers temporarily fill different types of labour needs that are most commonly recurrent and that employers prove unable to meet using other means

- The program helps protect jobs for Canadians and permanent residents, and can contribute to job creation and economic growth in some sectors

- Overall, there is no evidence pointing to a risk for job displacement or wage suppression at the national level in Canada. In 2019, temporary foreign workers represented only 0.49% of the total labour force in Canada.Footnote 2There is, however, evidence of varying factors affecting employment and working conditions in localized labour markets. This points to some risk of job displacement or wage suppression in some specific sectors, occupations and regions

- Important challenges related to the Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) process and related requirements may hinder the effectiveness of the program for some program users

- Administrative and financial barriers associated with using the program may explain why some employers do not use the program. It should be noted that other comparable employers in similar situations use the program

- The program contributes towards ensuring that qualified Canadians or permanent residents are considered first for current job opportunities

- The transition plans required from employers who apply through the High-Wage Stream encourage some of them to support the foreign workers’ transition to permanent residency

- Findings suggest that transition plans do not reduce employers’ need for the program

Recommendations

- Better engage employers and key stakeholders on the objectives of the program

- Explore alternative approaches for application-based processing for returning or frequent program users who maintain good track records in the program

- Clarify processes to help program officers assess labour market impacts and shortages more consistently

Program background

The Temporary Foreign Worker Program is legislated through the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act and Immigration and Refugee protection Regulations. One of the key objectives of the program is to provide Canadian employers with access to temporary foreign workers when qualified Canadians or permanent residentsFootnote 3 are not available.

Figure 2: Temporary Foreign Worker Program timeline

-

Text version of figure 2

Year or period Milestones 1966 Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program established 1973 Temporary Foreign Worker Program established (high-skilled workers component only) 1922 Line-in Caregiver Program introduced 2002 Low-skilled workers component added 2013 Evaluation (2007 to 2010) 2014 2014 Reforms: Temporary Foreign Worker Program (LMIA required) and International Mobility Program (LMIA not required) May 2017 Auditor General Report June 2017 Global Talent Stream June 2020 Internal Audit Report 2018 to 2021 Evaluation

The recruitment of foreign workers in Canada dates back to the 1960s. The Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program was first established in 1966 with the main focus on the agricultural industry. In 1973 the federal government put in place the Temporary Foreign Worker Program which focused on hiring high-skilled foreign labour. The Live-in Caregiver Program was introduced in 1992 with a key requirement that the caregiver must live with the hiring family. The program’s focus was further widened in 2002, adding the low-skilled workers’ component. Since then, the program has been expanding, reaching its peak in 2013 when 162,400 temporary foreign worker positions were approved under the program. In June 2014, the federal government announced reforms to the program, restructuring it into 2 distinct programs:

- the Temporary Foreign Worker Program, and

- the International Mobility Program

The Temporary Foreign Worker Program is jointly administered by Employment and Social Development Canada, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada and the Canada Border Services Agency.

Budget 2017 proposed an investment to support the continued delivery and improvement of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program and the International Mobility Program. The investment builds on Canada’s new Global Skills Strategy, which aims to facilitate the temporary entry of high-skilled international talent.

- $280 million over 5 years, starting in 2017 to 2018

- $50 million per year thereafter

The Temporary Foreign Worker Program is a small proportion of the overall labour market.

Figure 3: Composition of the labour force (2018)

-

Text version of figure 3

Group or sub-set Count Percentage of the total labour force Note Total labour force 19.8 millions 100% n/a Permanent immigrants

and temporary residentsFootnote 48.4 millions 43% n/a Temporary residents

with work permits795,000 4% These temporary residents with work permits include both those hired through the Temporary Foreign Worker Program and those hired under Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s International Mobility Program. Unlike the positions filled through the Temporary Foreign Worker Program, those filled through the International Mobility Program are exempted from the requirement to undergo a Labour Market Impact Assessment. Such exemptions are provided when it has been demonstrated that the hiring of temporary foreign workers will help support and advance Canada’s broad economic and cultural national interests. Temporary residents with Temporary Foreign Worker Program work permits 120,000 0.6% This group of workers forms a sub-set of all temporary residents with work permits.

Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) application requirements and assessment

- Canadian employers interested in hiring foreign nationals through the program must first determine whether a LMIA is required. The LMIA application must outline recruitment efforts, in order to demonstrate that they cannot find Canadians or permanent residents to meet their labour needs

- The program’s minimum requirements require that employers conduct a minimum of 3 distinct recruitment efforts. They have to last at least 4 weeks within the 3 month period prior to the employer applying for a LMIA

- At least 1 recruitment effort should continue until the date a positive or negative LMIA is issued

- Employers seeking to hire low-wage foreign nationals are required to recruit from at least 2 of the 4 underrepresented groups in the labour market:

- persons with disabilities

- Indigenous people

- newcomers, and

- vulnerable youth

- Employers seeking access to the High-Wage and Low-Wage Streams of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program are required to advertise on Job Bank, or on its provincial counterpart. They also have to use 2 or more additional methods of recruitment

- Employers applying to the Global Talent Stream or the Primary Agriculture Stream are exempt from those requirements

- For on-farm Primary Agriculture positions, employers need to conduct 1 additional method of recruitment. They are not required to ensure that at least 1 advertisement remains posted until the date a positive or negative LMIA is issued

- Once those recruitment requirements are fulfilled, employers are to submit the LMIA application to ESDC. LMIAs are conducted by Service Canada to ensure that:

- there is a genuine need for the temporary foreign worker position (for example skills or labour shortages), and

- Canadians are not available to fill the position

- Other factors considered during the LMIA application assessment include:

- the number of Canadians who applied and were interviewed for the job

- the reasons for not hiring them, and

- whether the temporary foreign workers may or will have a negative effect on the Canadian labour market

- If all requirements are met, a positive LMIA is granted. This gives the employer the authorization to hire temporary foreign workers in some or all positions for which the application was submittedFootnote 5

- Employers hiring temporary foreign workers under the program must pay them the wage determined by the applicable collective agreement, if any. When those temporary foreign workers are hired in non-unionized positions, the employer has to pay them a prevailing wage established by the program

- Employers must ensure that they include the wage to be paid for the position in the job posting

- They must also review and adjust (if necessary) the foreign worker’s wage after 12 months of employment. This is to ensure that the worker continues to receive the prevailing wage rate of the occupation and work location where the foreign worker is employed

- The prevailing wage corresponds to the higher of:

- the median wage for the corresponding occupation in the region where the job is located, as published on the Job Bank website

- the wage as defined by other publicly available labour market information, or

- the wage the employer is paying Canadian or permanent resident employees working in the same occupation and work location, and who have the same skills and experiences

- In Quebec, where the program is delivered in partnership with the provincial government, the prevailing wage is determined by Immigration, Francisation et Intégration Québec, using a different wage grid

- For each of the occupations listed, this grid also includes 3 wage quartiles associated with different levels of experience required for the job:

- from 0 to 2 years (first quartile)

- more than 2 years but less than 9 years (second quartile), and

- more than 9 years of experience (third quartile)

- In both Quebec and the rest of Canada, the positions to be filled under the program are classified under the National Occupational Classification (NOC) 4 digit code that best corresponds to the job description

- In Quebec, the wage data used is aggregated at the provincial level. In other provinces, it is available by economic region within the province. Finally, in Quebec, wage data may not be available at the provincial level for the corresponding National Occupational Classification code. In that case, the prevailing wage that will apply corresponds to the national median wage published on the Job Bank website for that National Occupational Classification code

Key findings

Supporting employer needs

1. Between 2013 and 2016, there is a downward trend (46%) in the number of positions approved under the Temporary Foreign Worker Program. This is followed by an increase of 35% between 2017 and 2019

Figure 4: Total number of temporary foreign worker positions approved (2013 to 2020)Footnote 6

-

Text version of figure 4

Year 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Total number of temporary foreign worker positions approved 162,400 104,172 89,416 87,760 97,054 108,058 129,458 123,312 Source: Open Government data from 2013 to 2020.

- The decline in the number of positions approved between 2013 and 2016 is observed since the program gradually introduced the LMIA processing fees

- Changes in the labour market (for example strong economic growth in the context of an aging population) required more foreign workers between 2017 and 2019, hence the upward trend

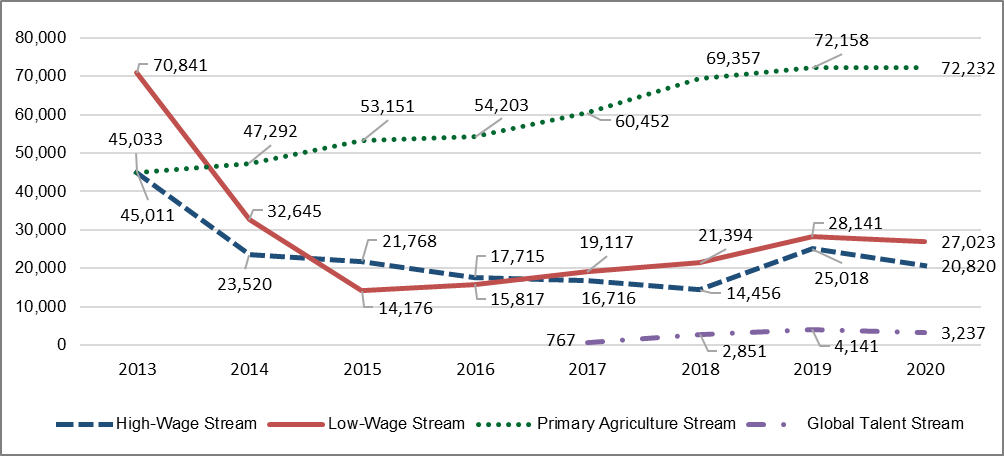

- Figure 5 below indicates that:

- between 2013 and 2020, the number of positions approved under the Low-Wage Stream decreased by approximately 62%

- over the same period the number of positions approved under the High-Wage Stream decreased by approximately 54%, and

- the number of positions approved under the Primary Agriculture Stream over the same period increased by approximately 60%

- The reduction of low-wage positions is considered to result from the establishment of a cap on the number of low-wage positions that can be filled under the program within single employer organisations

Figure 5: Total number of temporary foreign worker positions approved, by stream (2013 to 2020)

-

Text version of figure 5

Year 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 High-Wage Stream 45,011 23,520 21,768 17,715 16,716 14,456 25,018 20,820 Low-Wage Stream 70,841 32,645 14,176 15,817 19,117 21,394 28,141 27,023 Primary Agriculture Stream 45,033 47,292 53,151 54,203 60,452 69,357 72,158 72,232 Global Talent Stream n/a n/a n/a n/a 767 2,851 4,141 3,237 Source: Open Government data from 2013 to 2020.

2. A majority (53%) of employers indicated that they need the program to fill labour shortages

- 53% of LMIA applicants indicated that they required the Temporary Foreign Worker Program to fill labour shortages

- According to Figure 6, labour shortages are noted most in the Global Talent and High-Wage Streams

- This remained relatively stable over time but increased sharply between 2017 and 2018

Figure 6: Proportion of employers who indicated that the hiring of temporary foreign workers will fill labour shortages, by stream (2011 to 2018)

-

Text version of figure 6

Stream Global Talent Stream High-Wage Stream Low-Wage Stream Stream to support permanent residency Primary Agriculture Stream All streams Proportion of employers who indicated that the hiring of temporary foreign workers will fill labour shortages from 2011 to 2018 69% 62% 50% 57% 41% 53% Source: ESDC’s LMIA system data analysis (2011 to 2018).

Figure 7: Proportion of employers who indicated that the hiring of temporary foreign workers will fill labour shortages, by year and stream (2011 to 2018)

-

Text version of figure 7

Year Global Talent Stream High-Wage Stream Low-Wage Stream Stream to support permanent residency Primary Agriculture Stream All streams 2011 n/a 52% 42% n/a 24% 43% 2012 n/a 48% 45% n/a 28% 44% 2013 n/a 59% 50% 42% 36% 52% 2014 n/a 65% 44% 78% 36% 50% 2015 n/a 63% 67% 88% 32% 59% 2016 n/a 76% 46% 91% 34% 58% 2017 0% 82% 49% 87% 37% 57% 2018 90% 88% 92% 96% 92% 91% Source: ESDC’s LMIA system data analysis (2011 to 2018).

- The program is often considered by employers and other stakeholders as the only solution for finding and/or retaining workers in occupations or industry sectors where there are:

- skills shortages

- labour gaps, and/or

- retention issues, either nationally or regionally

3. Survey respondents from all streams applied to the program on average 3 times between 2015 and 2020

- Applications to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program continue at a steady pace, indicating an ongoing need for workers

- The 505 survey respondents (employers) submitted a total of 1,734 LMIA applications between 2015 and 2020. Each applicant made on average 3.43 applications during that period

- Employers who applied under the Primary Agriculture Stream are those who reported using the program most frequently. They submitted an average of 5.26 applications over the reference period

- A lower number of applications (average 2.21) were made under the Low-Wage Stream

Figure 8: Average number of applications submitted by survey respondents (unique employers), by stream (2015 to 2020)

-

Text version of figure 8

Stream Average number of applications submitted by survey respondents (unique employers) from 2015 to 2020 Primary Agriculture Stream 5.26 Low-Wage Stream 2.21 High-Wage Stream 2.49 Stream to support permanent residency 2.35 All streams 3.43 Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

4. The level of satisfaction with the timeliness of the response to applications varies by stream with 50% to 60% not being satisfied

- Based on survey responses, the period of time required before obtaining the result of the LMIA was 10.5 weeks on average for all program streams

- This processing time was particularly high at about 16 weeks for the High-Wage StreamFootnote 7

- Respondents indicate needing to begin recruitment efforts up to 1 year in advance to account for LMIA and work permit processing times

Figure 9: Percentage of respondents who were satisfied or very satisfied with the timeliness of the response to their application (n=505)

-

Text version of figure 9

Stream Satisfied Very satisfied Primary Agriculture Stream 32% 29% Low-Wage Stream 29% 16% High-Wage Stream 25% 15% Stream to support permanent residency 31% 24% Private households (caregivers or housekeepers only) 23% 16% All streams 29% 22% Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

Figure 10: Average number of weeks required before obtaining the Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) result, according to estimates provided by survey respondents (n=353)Footnote 8

-

Text version of figure 10

Stream Average number of weeks required before obtaining the LMIA result Primary Agriculture Stream 6.1 Low-Wage Stream 13.0 High-Wage Stream 15.9 Stream to support permanent residency 11.2 Private households (caregivers or housekeepers only) 13.9 All streams 10.5 Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

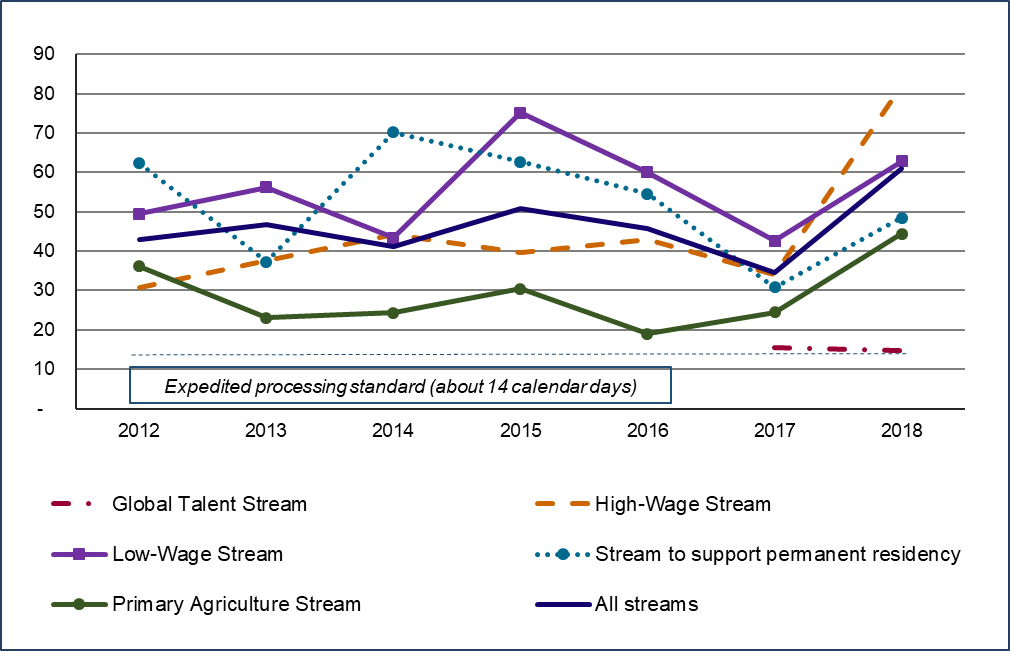

5. The average number of calendar days required to process LMIA applications reached 61 days in 2018. It was even higher at 82 days for those submitted in the High-Wage Stream

- The average LMIA processing times tend to fluctuate significantly over time and by program stream

- Service standards are generally met for applications submitted under the Global Talent Stream. However, they are not always met for applications submitted under the Stream to support permanent residency which have a 10 business days processing standard

Figure 11: Average number of calendar days required to make a decision on a LMIA application by stream (2012 to 2018)Footnote 9

-

Text version of figure 11

Year Global Talent Stream High-Wage Stream Low-Wage Stream Stream to support permanent residency Primary Agriculture Stream All streams 2012 n/a 31 50 62 36 43 2013 n/a 38 56 37 23 47 2014 n/a 44 43 70 24 41 2015 n/a 40 75 63 30 51 2016 n/a 43 60 54 19 46 2017 15 34 43 31 24 35 2018 15 82 63 48 44 61 Source: ESDC’s LMIA system data analysis for the current evaluation covering the period from 2012 to 2018.

The 2016 Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities (HUMA) Review also pointed out that the length of time to process the Labour Market Impact Assessment applications across the streams was a challenge. The 10 business day processing service standard for high-demand occupations introduced in 2014 was not always met.

| Stream | Average LMIA processing time for February 2021 |

|---|---|

| Global Talent Stream | 13 business days |

| Agricultural Stream | 21 business days |

| Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program | 14 business days |

| Permanent Residence Stream | 21 business days |

| High-Wage Stream | 32 business days |

| Low-Wage Stream | 33 business days |

| In-home caregivers | 15 business days |

6. According to Service Canada key informants, a combination of factors explain why processing times have been increasing and can continue to fluctuate over time

- Significant and unexpected increases in the demand for Labour Market Impact Assessments

- The complexity and frequent changes of program rules and requirements makes the training of new program staff relatively lengthy and challenging

- The implementation of a National Quality Control Program required that more information is provided to substantiate the decisions made. This increased the average time required to process each application

- The implementation of a new IT system in 2018 for the processing of applications encountered major hurdles. This led to the accumulation of a significant backlog of applications to be processed

In 2021, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration also pointed out that:

- the work permit processing times are lengthy

- the administrative burden on small businesses needs to be reduced, and

- successful applicants should be fast-tracked for permanent residency, if applicable

The committee also noted a need to improve:

- consistency within Service Canada

- coordination between ESDC and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, and

- communications in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic

Some suggestions made by external stakeholders to reduce the administrative burden associated with the LMIA process include:

- the creation of a simplified renewal process for employers who show a good track record in the program, and

- the implementation of an accreditation system or « trusted employer model » for employers who need to use the program on a more frequent basis, due to recurring or chronic labour shortages

Sources: ESDC’s key informant interviews (2020). Parliament of Canada, Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration (2021).

7. Employers note a reluctance among Canadian workers to apply for jobs in certain streams

- 63% of employers who received a negative LMIA decision still had difficulties finding Canadians for the position offered

- A higher proportion of employers in the High-Wage Stream mentioned that Canadians are not interested, available or qualified

- A higher proportion of employers in the Primary Agriculture Stream mentioned that the hard work and physical condition of their job is a challenge in recruiting Canadians

| Why not Canadian workers? | Percentage of survey respondents |

|---|---|

| Hard work/physical labour | 37% |

| Non-standard work schedule | 27 % |

| Remote location | 24 % |

| Uninteresting work (for example, repetitive) | 21% |

Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

| Why not Canadian workers? | Percentage of survey respondents |

|---|---|

| Temporary/seasonal job | 19 % |

| Low wage | 19 % |

| Poor working environment | 18 % |

| Low hours | 5 % |

Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

Figure 12: Proportion of employers who indicated that Canadians are not interested, available or qualified, by stream

-

Text version of figure 12

Stream Proportion of employers who indicated that Canadians are not interested, available or qualified Primary Agriculture Stream 35.5% Low-Wage Stream 36.8% High-Wage Stream 42.5% Stream to support permanent residency 38.8% Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

Sector sustainability

8. The vast majority (92%) of employers who hired temporary foreign workers reported that it helped them meet demand for their products or services

- The majority or vast majority of survey respondents who hired temporary foreign workers also reported that it helped improve their organization's ability to:

- stay in business (89%)

- meet financial targets (80%)

- expand or diversify activities (74%), and

- retain current employees (70%)

- Without the program, some firms would need to reduce their output or the quality of the goods and services produced, while others may cease to exist

- Gross (2014) argues that “in the absence of a well-framed Temporary Foreign Worker Program, wages will rise or the production will be stopped (or decreased) due to a lack of domestic workers. Thus, an effective Temporary Foreign Worker Program can make a positive contribution to smoothing (and/or increasing) economic development. By filling in positions left vacant by domestic workers, temporary foreign workers act as temporary complements to domestic workers”

- Input obtained through key informant interviews and focus groups also indicates that the program can provide these benefits:

- productivity gains

- reduced turnover and business stabilization, since temporary foreign workers are tied to them through employer-specific work permits, and

- allow a potential transfer of new skills and knowledge from the temporary foreign workers to Canadian or permanent resident staff

Figure 13: Percentage of employers who reported that hiring temporary foreign workers improved their organization's ability to do the following, to a large or very large extent (n=288)Footnote 10

-

Text version of figure 13

Hiring temporary foreign workers improved their organization's ability to: To a large extent To a very large extent Hire more Canadians 16% 28% Retain its current employees 18% 52% Expand and/or diversify its activities 20% 54% Meet its financial targets (in other words revenues/profits) 20% 60% Stay in business 13% 76% Meet demand for its products/services 18% 74% Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

9. There were negative implications for 76% of employers who obtained a negative Labour Market Impact AssessmentFootnote 11

- According to employers, the program contributes to sector sustainability. The findings in Figure 14 suggests the following:

- 45% indicated that they could not stay in business

- 74% reported that they could not meet their financial targets, and

- 75% indicated that they could not expand or diversify their business

- According to the Canadian Agricultural Human Resource Council, the inability to hire temporary foreign workers to respond to unfilled job vacancies on farms can result in production losses and delays. This leads to lost revenue (2020)

- Mukhopadhyay and Thomassin (2021) also note that temporary foreign workers can “lower the operating costs for firms through increased output and encouraging either expansion or at least maintenance of current output”

- These findings confirm that foreign workers contribute to sector sustainability in Canada

Figure 14: Percentage of respondents who reported that not being able to hire foreign workers had a negative impact on their ability to:

-

Text version of figure 14

Not being able to hire temporary foreign workers had a negative or very negative impact on their organization's ability to: Very negative Negative Expand and/or diversify activities 55% 20% Meet financial targets (in other words revenues/profits) 47% 27% Meet the demand for products/services 55% 18% Hire more Canadians 33% 12% Retain current employees 23% 18% Stay in business 25% 20% Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

10. More than half (55%) of the employers who were not authorized to hire some or any temporary foreign workers had to ask their current employees to work overtime to compensate

- According to employers, the inability to hire temporary foreign workers can negatively impact Canadian workers:

- 44% kept employees that should have been let go

- 33% reduced opening hours or closed down locations, and

- 9% Canadians were laid off due to not being able to stay open

- These findings also suggest that foreign workers contribute to sector productivity and sustainability in Canada

Figure 15: As a result of not being able to hire foreign workers, did any of the following occur? (n=75)

-

Text version of figure 15

As a result of not being able to hire foreign workers, the following occurred: Percentage of respondents Existing employees worked overtime to compensate 55% Turned down work/reduced output 51% Kept employees you might have otherwise let go 44% Reduced open hours/closed down some locations 33% Canadian workers were laid off 9% None of these 5% Don't know/no response 4% Other 3% Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

Job displacement and wage suppression

Background

An inherent concern associated with immigration policy at-large and the Temporary Foreign Worker Program specifically, is their impacts on the domestic labour markets (at the national and/or local level). The premise for these concerns is typically rooted in the view that immigrants are competing with domestic workers over a fixed number of jobs. Based on this premise, immigrants would potentially:

- put downward pressures on national/local wages (wage suppression), and

- lead to lower employment rates as domestic workers drop out of the labour force (job displacement)

These concerns generally align with basic inferences from the standard theoretical model of supply-and-demand. In this model, an increase in the labour supply leads to lower wages for all workers (Constant, 2014).

However, this type of inference is often viewed as overly simplistic, since it omits a number of key considerations (Mukhopadhyay and Thomassin, 2021, Banerjee and Duflo, 2019, Somerville and Sumption, 2009). For instance:

- immigrants and domestic workers may complement rather than compete with each other

- immigrants may contribute to labour market efficiency, which in turn also affects the demand for domestic workers

- immigrants consume goods and services, which in turn affects the demand for domestic workers

Taken together, these considerations suggest that immigrants lead to an increase in both the labour supply and labour demand. As per the standard theoretical model of supply-and-demand, both increases are associated with offsetting effects on wages and employment. Which effect dominates becomes an empirical question.

Most of the empirical research in this area focuses on the impact of immigration (or permanent migrants) on the wages and employment of domestic workers. On the impact of temporary migrants on the labour market of the host country, the literature is limited (Mukhopadhyay & Thomassin, 2021). In the particular case of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program, not enough empirical research has been conducted to inform a definite answer on these questions (Mukhopadhyay & Thomassin, 2021).

Definitions

Job displacement: Displaced workers are workers who permanently lost a stable job in the last few years and who are currently unemployed, out of the labour force or re-employed (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development).

Wage suppression: Wage suppression occurs when downward pressure is put on domestic wages – thereby keeping them low. This is sometimes attributed to firms offering lower wages than they would otherwise in order to maximize their use of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program.Footnote 12

From an empirical perspective, assessing the impact of temporary foreign workers on domestic labour markets is very complex. It involves many observable and unobservable contributing factors. The impact of temporary foreign workers on the national and local labour markets depends, in part, on:

- the degree of substitutability between the domestic and the foreign workers

- the degree of labour market tightness and how it is affected by seasonality

- labour market institutions, such as income support programs and wage-setting mechanisms affecting the mobility and work decisions of domestic workers, and

- firms’ decisions regarding the allocation of resources between labour and capital, which in turn affects the demand for domestic workers

Other factors, often unobservable such as language barriers, local/organizational norms and culture, and motivation may also affect these decisions. Exacerbating the challenge with the conduct of such an empirical analysis is the small number of temporary foreign workers relative to the size of the Canadian labour force. Even at the regional and industry level, where the incidence of temporary foreign workers among labour force participants is relatively higher, disaggregate labour market information would be subject to variability due to small sample sizes. Furthermore, approaches to isolate the impact of temporary foreign workers inherently involve the estimation of how national and local labour markets would have adjusted in the absence of temporary foreign workers. This is not observed and therefore remains subject to debate.

For these reasons, no advanced empirical analysis was conducted as part of this evaluation. Instead, the Evaluation Directorate commissioned two research projects to assess potential impacts of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program’s Low-Wage Stream on the Canadian labour market. The research has a focus on the potential suppression of Canadian wages and displacement of Canadian workers. This research takes advantage of the newly available linkages between Temporary Foreign Worker Program data and the Canadian Employer-Employee Dynamics Database. The creation of this new consolidated dataset is the result of efforts from ESDC's Evaluation Directorate in collaboration with the Chief Data Officer, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, and Statistics Canada. It is meant to enable this type of research work, policy analysis and future evaluations (for more details, see Annex D). Due to COVID-19, these research projects were delayed and are expected to be completed in 2022. They will shed more light on the complex questions of job displacement and wage suppression. Once completed, the research reports will be available upon request.

As a complementary effort, this evaluation aims at contextualizing the potential risk of wage suppression and job displacement. This was done by gathering information mainly through qualitative lines of evidence (for example a survey, key informant interviews and focus groups) and descriptive quantitative data analysis. Information gathered as part of this evaluation may help inform specific policy design features of the program. However, it is not sufficient to draw specific and definitive conclusions on these 2 labour market issues.

Summary of evaluation findings on job displacement and wage suppression

- Key findings indicating no risk for job displacement and wage suppression at the national level:

- in 2019, there were about 98,000 foreign workers who were hired through the Temporary Foreign Worker Program in Canada. They accounted for just 0.51% of total employment and 0.49% of the total labour force in Canada

- approximately 38% of employers perceived that Canadian workers are either not interested, available or qualified for the job opportunity

- only 12.6% of Canadian job seekers viewed potential job matches on the Job Bank between 2015 and 2018, suggesting low interest in foreign-worker-dominated jobs

- approximately 63% of employers who received a negative LMIA decision continued to have difficulties in finding Canadians to fill positions

- Gross (2014) argued that the Temporary Foreign Worker Program has allowed jobs to be filled relatively quickly, which prevents interruptions in production

- an expert panel discussion related to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program and the labour market noted that since the temporary foreign workers constitute a small fraction of the Canadian population, any negative impact they may have will be small (ESDC Workshop Report, 2018)

- Some of the evidence pointing to some risk of job displacement and wage suppression is noted as follows:

- approximately one third of key informants and between 66% and 75% of survey participants indicated that there may be preferences to hire foreign workers

- Beine and Coulombe (2017) noted that “employers, having hired temporary foreign workers from a specific origin country, get some useful information about those workers’ productivity and commitment to the job. If satisfied, Canadian employers subsequently tend to hire the same temporary foreign workers of the same origin”

- some key informants pointed out that the program demonstrates some risk for wage suppression in specific sectors, occupations and regions

- some key informants and focus group participants indicated that worker displacement may be occurring in some sectors (trucking, construction, food industry, beauty parlors)

- the report highlights some examples of sectors and occupations (that is carpenters, fish and seafood, agriculture) that may be at some risk for wage suppression

Job displacement – No risk

11. Approximately 38% of employers perceived that Canadian workers are either not interested, available or qualified for the job opportunity

Figure 16: Challenges faced by employers who tried to recruit Canadian workers

-

Text version of figure 16

Challenges faced by employers who tried to recruit Canadian workers Percentage of respondents Canadians are not interested/available/qualified 37.6% Other 8.0% The work schedule was not standard 7.9% No problems 7.1% Retention issues (unreliable/quit after hired) 7.0% The place of work is in a rural or remote area, or location is inconvenient 6.2% Wages not attractive 6.0% It was hard work/involving physical labour 5.0% The type of work 3.7% The work environment and conditions are difficult or stressful 3.7% Don't know/no response 3.1% Poor work ethic 2.9% It was a temporary or seasonal job 1.6% The number of hours a week was too low 0.2% Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

Survey respondents reported that the Canadians who applied were not hired because of the following factors:

| Reasons why Canadians were not hired | Percentage of respondents |

|---|---|

| The lack of previous experience | 28% |

| The lack of work ethics demonstrated by the candidate | 24% |

| The candidate eventually lost interest in the job | 23% |

Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

12. Only 12.6% of Canadian job seekers viewed potential job matches on the Job Bank between 2015 and 2018. This suggests low interest in jobs occupied by foreign workers

- Employers seeking access to the High-Wage and Low-Wage Streams must post their jobs on the Job Bank website or on its provincial counterpart

- The Job Bank and Foreign Workers System databanks were linked

- An analysis of positions advertised in the Job Bank by employers who used the Temporary Foreign Worker Program between 2015 and 2019 was conducted (see Annex C for more details)Footnote 13

- From 2015 to 2018, on average, only about 31% of all LMIA applications were associated with a job posting on the Job Bank. This proportion increased from 7% in 2015 to 49% in 2018. However, it remained relatively low for the Primary Agriculture Stream, at only 23% in 2018

- Key informants and focus group participants noted that employers do not always consider Job Bank to be the best tool to connect with local workersFootnote 14

- Data analysis revealed that only 4.1% of Canadian job seekers requested information on how to apply for the job matches

- 0.2% of Canadian job seekers indicated that they applied for a job matching their interests and skills

Figure 17: Actions taken by Canadian job seekers whose profile was matched with the job posted on the Job Bank (on average between 2015 and 2018)

-

Text version of figure 17

Actions taken by Canadian job seekers whose profile was matched with the job posted on the Job Bank Percentage of job seekers (on average between 2015 and 2018) Viewed the matching job posting 12.6% Favorited the matching job posting 3.6% Clicked to obtain information on how to apply 4.1% Voluntarily indicated they applied to the job 0.2% Rejected the matching job 1.1% Source: ESDC’s linked data for the current evaluation covering the period 2015 to 2018.

13. Approximately 73% of employers who received a negative LMIA decision experienced continued difficulties in finding Canadians to fill positions

| Ability to fill the positions with Canadians | Percentage of employers who received a negative LMIA decision |

|---|---|

| Were unable to fill the positions with Canadians | 42.6% |

| Were able to fill some of the positions with Canadians | 30.4% |

Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

| Efforts made to try to recruit Canadians after the negative LMIA decision | Percentage of employers |

|---|---|

| Posted the job on another platform | 88.5% |

| Tried to advertise the position more actively | 64.1% |

| Offered training to Canadians | 56.4% |

| Increased the wage offered | 51.3% |

Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

- Key informants pointed out several reasons as to why some businesses hire temporary foreign workers and some don't:Footnote 15

- type of goods or services provided in niche industries that require workers with specialized training and experience which Canadians may not have

- smaller and less established businesses may not be able to offer higher wages or better working conditions to attract more Canadians, and

- the economic sector and the severity of labour shortages in the community where the business is located

- These findings are consistent with the fact that foreign workers can either complement or substitute the Canadian labour force. This would depend on the type of skills and experiences they bring into the country, as well as on other factors such as the availability and motivation of Canadian workers

14. Only 12% of surveyed employers believe that the program has a negative impact on Canadian workers related to job displacement

Surveyed employers believe that the hiring of temporary foreign workers:

| The hiring of temporary foreign workers: | Percentage of surveyed employers |

|---|---|

| Leads to not hiring Canadians | 9% |

| From the time when the pandemic started temporary foreign workers are taking jobs that Canadians might want | 1% |

| Leads to Canadian workers being laid off (before temporary foreign workers) | 1% |

| Causes employers to rely on temporary foreign workers even when Canadians are available | 1% |

Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

- The key informants agreed that the design of the program and measures put in place prevent the displacement of Canadian workers and ensure that they are considered first for job opportunities:

- mandatory posting of the job on Job Bank and 2 other forums where Canadians or permanent residents can apply

- verification of the records of employment recently issued by the employer

- expensive Labour Market Impact Assessment application fee, and

- extensive administrative and logistic requirements

Source: ESDC’s key informant interviews 2020.

The analysis of administrative data revealed that the vast majority of employers attempted to hire Canadians first over the years.

Figure 18: Employers attempting to hire Canadians or permanent residents first, by year (2011 to 2018)

-

Text version of figure 18

Year Yes No Missing 2011 72% 25% 3% 2012 61% 27% 12% 2013 64% 33% 3% 2014 72% 28% 0% 2015 75% 25% 1% 2016 81% 19% 0% 2017 82% 18% 0% 2018 77% 11% 12% Source: ESDC’s LMIA system data analysis for the current evaluation covering the period from 2011 to 2018.

Wage suppression – No risk

15. A very small proportion (0.49%) of the labour force in Canada is comprised of temporary foreign workers

- In 2019, there were about 98,000 temporary foreign workers in Canada, accounting for just 0.51% of total employment and 0.49% of the total labour force in Canada. This points to no risk for wage suppression at the national level

- An expert panel discussion related to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program and the labour market noted that since the temporary foreign workers constitute a small fraction of the Canadian population, any negative impact they may have will be smallFootnote 16

Source: ESDC’s customized tables using Labour Force Survey and LMIA data.

- Focus group participants and key informants noted how the risk of wage suppression is mitigated:

- the mandatory use of prevailing wages when temporary foreign workers are hired

- the presence of unions in organizations where temporary foreign workers are hired

- According to Mukhopadhyay and Thomassin (2021), “the provision to pay the same regulated wages to temporary foreign workers as domestic workers implies that the employers do not seek temporary foreign workers as a means for getting away with lower wages. Rather, temporary foreign workers are the last resort for employers where domestic workers are either not willing to take up a particular job or are simply not available. Thus, this is a case of temporary foreign workers supplementing the domestic labour with essentially no impact on domestic wages or further employment for Canadians who may wish to work in the sector in the future”

- Most workers indicated that their presence had no significant effect on wages as they are performing work that Canadians are not interested in and that their wages are regulated

Sources: ESDC’s key informant interviews 2020, ESDC’s focus groups 2020 and Mukhopadhyay and Thomassin (2021).

| Foreign workers were paid: | Percentage of surveyed employers |

|---|---|

| The same as Canadian workers doing similar or equivalent tasks | 85% |

| More than Canadian workers | 6.5% |

| Less than Canadian workers | Only 3.5 % |

Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

Sector/industry example

16. Evidence from the analysis of top wage earners in Atlantic fish and seafood plant and processing workers points to no risk for wage suppression

- The average top hourly wage was generally the same or higher for companies with temporary foreign workers than for those without, according to a 2017 survey of fish and seafood businesses

- Data prepared by Prism Economics and Analysis for the Food Processing Skills Council

Figure 19: Average top hourly wages by employment of temporary foreign workers

-

Text version of figure 19

Occupation Average top hourly wage, businesses that employ temporary foreign workers Average top hourly wage, businesses that do not employ temporary foreign workers Difference Fish and seafood plant workers (NOC 9463) $19.57 $17.30 $2.26 Shellfish plant worker $17.85 $17.92 -$0.07 Fish plant worker $28.18 $16.95 $11.24 Labourers in fish and seafood processing (NOC 9618) $16.41 $17.44 -$1.03 Shellfish processing labourer $15.53 $17.23 -$1.69 Fish processing labourer $19.47 $17.64 $1.83 Source: Prism Economics and Analysis for the Food Processing Skills Council (FPSC). Atlantic Fish + Seafood Processing Workforce Survey Report, June 2018.

Job displacement – Some risk

17. Approximately one third of key informants and between 66% and 75% of survey participants indicated that there may be preferences to hire foreign workers. In the long term, this is attributed to some risk for job displacement

- According to some key informants and focus group participants, the employers have developed a preference for temporary foreign workers in general. This could be to save on labour costs, make productivity gains and/or reduce employee turnover

A majority (66% to 75%) of survey respondents who have hired temporary foreign workers (n=339) indicated that in comparison to Canadian workers, temporary foreign workers are:

| In comparison to Canadian workers, temporary foreign workers are: | Percentage of respondents |

|---|---|

| More reliable | 75% |

| More likely to stay with the organization after being hired | 73% |

| More hard working | 72% |

| More willing to take training needed for the job | 66% |

Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

- In a study by Brochu et al (2016), the authors argue that Canadian employers have a preference to hire temporary foreign workers over Canadians. This occurs even if they are obliged to pay the domestic wage rate after a failed search for a worker who is a citizen or permanent resident

- Other reasons noted by the key informants that could contribute to job displacement:

- for various reasons that are not necessarily related to the lack of Canadians who have the same profile, employers hire a specific foreign national they already know, and

- the employer is not acting in good faith and uses the program as an immigration strategy to help someone immigrate to Canada more rapidly

- These are considered some risk for job displacement. Most of the jobs occupied by the temporary foreign workers are unwanted by Canadians and foreign workers represent about 0.6% of the overall labour force (2018)

Sources: ESDC’s key informant interviews 2020 and focus groups 2020.

18. Some key informants and focus group participants indicated that worker displacement may be occurring in some sectors

- The participants mentioned the following sectors as examples:

- trucking industry

- construction industry

- beauty parlors

- food industries

- Displacement of Canadians is also considered in industries where part-time workers are being replaced with full-time workers

- However, participants pointed out an absence of tools to properly assess where the labour shortages are. They also reported difficulty in determining if in fact worker displacement is taking place in these sectors

- Temporary foreign workers are concentrated in specific employment sectors

Figure 20: Proportion of temporary foreign workers, selected industries (North American Industry Classification System subsectors), 2017

-

Text version of figure 20

Subsector Proportion of temporary foreign workers Crop production 27.4% Private households 9.8% Gasoline stations 8.0% Accommodation and food services 7.2% Animal production and aquaculture 5.6% Amusement, gambling and recreation 4.5% Warehousing and storage 4.3% Arts, entertainment and recreation 4.2% Clothing and clothing accessories stores 4.2% Food manufacturing 3.4% Overall 2.9% Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Employer-Employee Dynamics Database. For more details, see Lu (2020).

- It was noted that the system of capsFootnote 17was intended to prevent worker displacement by ensuring that low-wage positions are composed of a limited number of foreign workers

- This system of “caps” is based on attestations. These are not systematically validated or verified

- Employers can also find ways around these caps by moving workers around multiple sites

Sources: ESDC’s focus groups 2020 and ESDC’s Key informant interviews 2020.

19. Only 34% of employers viewed potential job matches of Canadian applications between 2015 and 2018. This may indicate a reduced effort to hire Canadians and may signal very low program compliance

- Job opportunities posted on the Job Bank by the employers are matched with the profiles of Canadian job seekersFootnote 18

- Only 34% of job matches were viewed by employers. This suggests that employers may not be making enough effort to view applications of potential qualified candidates

- On average, only 27% of employers invited the matched Canadian job seeker to apply for the job

Figure 21: Actions taken by employers for each Job Bank posting matched with the job seeker's profile (average between 2015 and 2018)

-

Text version of figure 21

Actions taken by employers for each Job Bank posting matched with the job seeker's profile Percentage of employers (average between 2015 and 2018) Viewed the job seeker's matching profile 34% Invited the job seeker to apply to the job 27% Rejected the job seeker's matching profile 5% Source: ESDC’s linked data for the current evaluation covering the period from 2015 to 2018.

- The increased number of temporary foreign workers and the co-existence of significant unemployment suggests that the hiring of temporary foreign workers was not done only as a last measure by employers (Worswick, C. et al., 2017)

- Some employers have integrated the hiring of temporary foreign workers into their business model and may have developed a longer-term dependency on the program

- The program is not necessarily viewed by employers as a last resort solution (in other words to be used when all other options have been exhausted). They view foreign workers as a source of added value

20. More than half (53%) of all survey respondents said that they did not make efforts to hire Canadians with disabilitiesFootnote 19 and 46% did not try recruiting Canadian vulnerable youth

The program requires employers to make an effort to hire Canadians from underrepresented groups:

| Efforts made to hire from underrepresented groups | Percentage of all survey respondents |

|---|---|

| Tried to recruit Indigenous Canadians | 57% |

| Actually hired Indigenous Canadians | Only 7% |

| Tried to recruit new Canadians | 60% |

| Recruited new Canadians | 16% |

Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

- The design of the program does not guarantee the hiring of Canadian workers from underrepresented groups for the following reasons:

- employers are not necessarily aware of, or able to access, the more specialized resources needed to recruit job seekers from underrepresented groups (for example community-based organizations)

- there is a resistance to change among many employers when it comes to using innovative approaches to recruiting job seekers from underrepresented groups (for example providing workplace accommodation to persons with disabilities)

Wage suppression – Some risk

Sector/industry example: 1

21. In 2018, approximately 66% of temporary foreign worker agricultural positions were paid lower than the occupations’ provincial median wagesFootnote 20

- The analysis of a sample of industries and regions is presented in the 2013 Temporary Foreign Worker Program Evaluation. This study revealed that in the agricultural industry in Ontario and Quebec, the average wage paid to temporary foreign workers appears to be below the range paid for similar positions

- According to Figure 22, agricultural positions, which include those filled through the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program, made up 64% of all positions in 2018

- The temporary foreign workers hired through the Primary Agriculture Stream are paid wages in accordance with commodity valuation calculations as per long-standing international agreements

Figure 22: Percentage of temporary foreign worker positions that received positive Labour Market Impact Assessments, by stream (2012 to 2019)

-

Text version of figure 22

Stream 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 High-Wage 31.69% 27.97% 22.77% 24.39% 20.20% 16.47% 13.38% 19.34% Low-Wage 48.47% 44.30% 31.83% 16.17% 17.99% 19.64% 19.81% 21.87% Primary Agriculture 19.83% 27.73% 45.40% 59.44% 61.76% 62.29% 64.17% 55.60% Global Talent n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a 0.79% 2.64% 3.19% Unspecified 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 0.05% 0.82% 0.00% 0.00% Source: Open Government data – Temporary Foreign Worker Program.

Sector/industry example: 2

22. Since 2016, the majority of temporary foreign worker carpenter positions in British Columbia and Ontario were paid well above their respective regional and provincial median wage levels. These temporary foreign workers’ wages grew by roughly 1% since 2016

- From 2016 to 2018, a decline in real wages was also reported for carpenters, nationally (-3.8%) and in British Columbia (-2.5%) and Ontario (-9.4%)Footnote 21

- However, the overall share of temporary foreign workers has remained low since 2016 in both British Columbia (1.5% to 3%) and Ontario (roughly 0.5%). This suggests very low impacts on wages for the occupation in both provinces and Canada

Figure 23: Provincial median wage among temporary foreign workers versus Canadians, carpenters (2016 to 2019)

-

Text version of figure 23

Year or period 2016 2017 2018 2019 (January to September) Ontario temporary foreign worker wage 28.00 $ 29.00 $ 30.00 $ 30.00 $ British Columbia temporary foreign worker wage 25.00 $ 26.25 $ 27.00 $ 27.00 $ British Columbia median wage 25.00 $ 25.50 $ 25.00 $ No data Canada 23.05 $ 25.00 $ 25.00 $ 25.00 $ Ontario median wage 22.00 $ 23.42 $ 25.00 $ 24.00 $ Source: Program’s study: Temporary Foreign Worker Program Wage Review, Winter 2019 (Data used: LMIA system, Job Bank website, Labour Force Survey).

Sector/industry example: 3

23. Evidence from the analysis of starting hourly wages of Atlantic fish and seafood plants and processing workers points to some risk for wage suppression

- The average hourly starting wage was generally lower for companies with temporary foreign workers than for those without, according to a 2017 survey of fish and seafood businesses

- Data prepared by Prism Economics and Analysis for the Food Processing Skills Council

Figure 24: Average starting hourly wages by employment of temporary foreign workers

-

Text version of figure 24

Occupation Average starting hourly wage, businesses that employ temporary foreign workers Average starting hourly wage, businesses that do not employ temporary foreign workers Difference Fish and seafood plant workers (NOC 9463) $13.24 $13.58 -$0.34 Shellfish plant worker $12.64 $12.99 -$0.35 Fish plant worker $16.15 $13.99 $2.17 Labourers in fish and seafood processing (NOC 9618) $13.18 $14.63 -$1.45 Shellfish processing labourer $12.82 $14.64 -$1.82 Fish processing labourer $14.49 $14.61 -$0.12 Source: Prism Economics and Analysis for the Food Processing Skills Council (FPSC). Atlantic Fish + Seafood Processing Workforce Survey Report, June 2018.

24. Some focus group participants and key informants including foreign workers identified cases or situations pointing to some risk for wage suppression

- The following situations were observed at least once and relate to wage suppression and the working experiences of some foreign workers:

- employers not actually paying the wages they committed to during the LMIA process, and/or making unauthorized deductions from the workers’ payFootnote 22

- employers hiring foreign workers whose work permits have expired without going through the mandatory LMIA process, while paying them cash at a significantly lower rate than the prevailing wage established by the program

- employers coercing temporary foreign workers to do extra work without providing them with proper compensation (for example unpaid overtime, additional tasks like cleaning and truck driving in very harsh weather and/or for extended hours)

- employers requiring the temporary foreign workers to give them back a portion of their wages in cash (for example $5/hour out of 25$/h), to cover the costs related to their hiring (for example the LMIA and work permit fees) and/or in exchange of support to obtain permanent residence

- It should be noted that the above listed practices are generally prohibited by the program and employment laws

Sources: ESDC’s key informant interviews 2020 and ESDC’s focus groups 2020.

25. Some key informants pointed out that the program demonstrates some risk for wage suppression in specific sectors, occupations and regions

- An expert panel discussion related to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program and the labour market noted that the temporary foreign workers concentrate in specific regions and occupations. The impact of the program may be significant in those sub-labour marketsFootnote 23

- Wage suppression might be occurring in specific sectors and situations as follows:

- in agriculture and any other low-wage or lower-skilled occupations where foreign workers are willing to work for lower wages than what a Canadian or permanent resident would consider acceptable

- sectors where compensation is calculated based on the type and/or amount of work done (for example in terms of weight or distance) such as the trucking industry

- when the positions filled by temporary foreign workers are exempted from the cap on low-wage positions (for example any work conducted on a farm or that is seasonal, such as landscaping, etc.)

- in positions that can be classified under different National Occupational Classification codes that encompass a broad range of job types and/or sub-specialties (for example in engineering, IT experts)

- in positions that are not unionized; and/or

- in regions or sectors where low-wage temporary foreign workers account for a relatively large proportion of all workers who occupy specific types of jobsFootnote 24

Source: ESDC’s key informant interviews 2020.

Wage suppression – Considerations

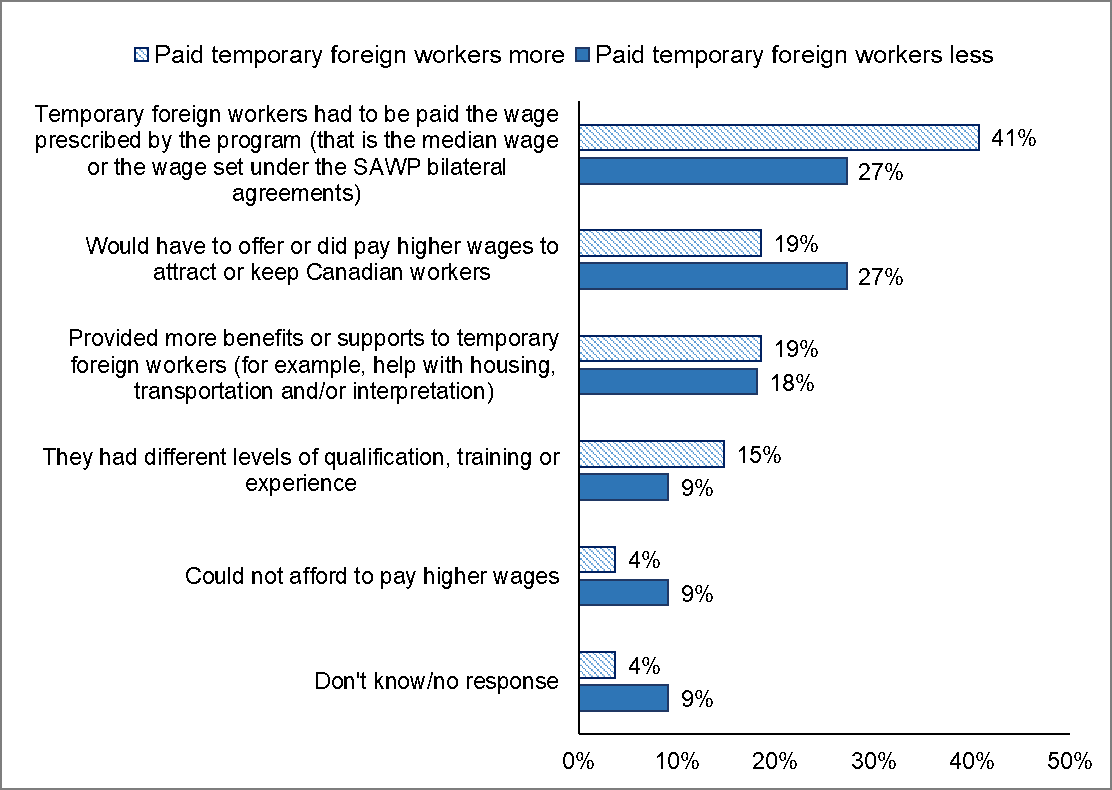

26. Surveyed employers indicated reasons for differences in wages paid to foreign workers and to Canadians

- The most common reason for paying temporary foreign workers more than Canadian workers was that temporary foreign workers had to be paid the prevailing wage established by the program (41%)

- The most common reason for paying temporary foreign workers less than Canadian workers was that employers had to offer or pay Canadian workers more to attract them or to keep them (27%)

Figure 25: Reasons why wages paid to foreign workers were different than those paid to Canadian workers in similar or equivalent positions

-

Text version of figure 25

Reason why wages paid to foreign workers were different than those paid to Canadian workers in similar or equivalent positions Percentage of employers who paid temporary foreign workers less Percentage of employers who paid temporary foreign workers more Don't know/no response 9% 4% Could not afford to pay higher wages 9% 4% They had different levels of qualification, training or experience 9% 15% Provided more benefits or supports to temporary foreign workers (for example, help with housing, transportation and/or interpretation) 18% 19% Would have to offer or did pay higher wages to attract or keep Canadian workers 27% 19% Temporary foreign workers had to be paid the wage prescribed by the program (that is the median wage or the wage set under the SAWP bilateral agreements) 27% 41% Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

27. Stakeholders outlined some factors that may unintentionally affect wages in Canada

- The use of wage data that is not precise enough geographically or that is outdated by up to 2 years

- Challenges with determining the actual “market wage” for a job, due to the difficulty or inability of finding a comparison basis and/or accurate wage data (in part due to limitations in the National Occupational Classification)

- The determination of the prevailing wage (during the LMIA) a lot of time in advance of the temporary foreign worker’s arrival here (for example up to a year prior)

- The use of provincial or national averages (in Quebec), which can be detrimental to temporary foreign workers hired in regions where the cost of living is higher (for example Montréal), and vice-versa

Source: ESDC’s key informant interviews 2020.

Transition plans

- Employers who wish to hire foreign workers under the High-Wage Stream are also required to submit a transition plan, in which they outline the activities they are agreeing to undertake to recruit, retain and train Canadians and permanent residents and to reduce their reliance on the Temporary Foreign Worker Program. Specifically, a transition plan must include:

- 3 distinct activities to recruit, retain, or train Canadians and/or permanent residents

- 1 additional activity specifically targeting underrepresented groups such as new immigrants, Indigenous people, people with disabilities, etc., or

- 1 activity to facilitate the temporary foreign worker(s)’ permanent residence

- A transition plan must be provided for each high-wage position for which an employer is seeking a LMIA. Employers must report on the success of the transition plan should they ever reapply to hire a temporary foreign worker or be selected for an inspection

28. The vast majority of employers (86%) who submitted a Transition Plan have supported their foreign workers to become permanent residents

- Supporting the worker’s application for permanent residence as part of a transition plan is considered to potentially reduce the need for the program by increasing the pool of available permanent resident workers

- This type of transition plan has the same outcome as submitting the application under the Stream to support permanent residency

- In both cases, the success of the transition to permanent residency and the extent to which it helped address the employer’s medium- to long-term needs cannot be fully assessed by Employment and Social Development Canada

- Specifically, when a positive LMIA is issued, no follow-up is systematically made by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada to inform Employment and Social Development Canada as to whether temporary work permits were issued for the position(s) approved under the LMIA and, if applicable, whether the temporary foreign worker(s) hired then successfully transitioned to permanent residency

Figure 26: Which of the following have you done as part of your transition plan?Footnote 25

-

Text version of figure 26

Measures undertaken as part of the transition plan Percentage of employers Supporting the foreign worker's application for permanent residency 86% Offered health insurance or other benefits 57% Hired apprentices, interns or co-op students 50% Increased the wages offered 46% Filled the positions from within the organization, by offering on-the-job training/paid leave for education 43% Advertised the jobs again and more actively 39% Attended job fairs 36% Implemented an employee referral incentive program 29% Hired a headhunting firm to identify prospective candidates 29% Provided financial supports for relocation of Canadian workers 18% Partnered with unions/industry associations/post-secondary education institutions to identify potential candidates 18% Offered part-time or flexible hours as an option 14% Don't know/no response 4% Source: ESDC’s: employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

29. The Transition Plans do not generally reduce or eliminate the need for foreign workers

- Approximately 14% of survey respondents reported that the implementation of transition plans did help them eliminate their need for the program

- However, the majority of survey respondents who implemented their transition plans (75%) reported that they still need to hire temporary foreign workers

- 25% of all respondents who did implement their transition plan reported that they hire more Canadians but also continue to need to hire temporary foreign workers

- Input from key informants and focus group participants indicate that employers who support the temporary foreign workers’ applications for permanent residence may continue to need the program, because:

- their overall need for workers may continue to grow between each application, and

- there is no guarantee that foreign workers will stay in the company indefinitely after obtaining their permanent residency

Figure 27: How successful has the transition plan been in progressively reducing the need for your organization to hire temporary foreign workers?Footnote 26

-

Text version of figure 27

Result of the transition plan Percentage of employers Not successful, the organization still cannot find Canadian workers to fill the positions 18% Somewhat successful, we hire more Canadian workers, but also need to hire more temporary foreign workers 25% Somewhat successful, some positions occupied by temporary foreign workers are now filled by Canadian workers 32% Very successful, all positions occupied by temporary foreign workers are now filled by Canadian workers 14% Don't know/no response 11% Source: ESDC’s employer survey 2020 (for the period 2015 to 2020).

30. Program stakeholders indicated that the transition plans are not effective and add unnecessary administrative burden

- Transition Plans are also generally considered to be administratively burdensome and to yield few concrete results, except in larger organizations where the activities outlined in those plans would already be occurring

- The development of those types of plans is particularly challenging for smaller businesses

- Program officials indicated that it is difficult to measure whether the commitments made as part of transition plans are honored

- Employers who submit transition plans would resubmit transition plans to the program repeatedly and still obtain the authorization to hire temporary foreign workers

- A few key informants noted that transition plans often comprise similar content that is partially copied and pasted from one application to another. They noted that most program users submit those plans to satisfy administrative requirements, without really expecting to eventually be able to reduce their reliance on the program

Source: ESDC’s key informant interviews 2020.

Management response and action plan

Overall management response

Management accepts the recommendations outlined in the Evaluation of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program and will be engaging in further analysis on how its findings can inform ongoing adjustments to program design and delivery. Insights gained through the evaluation’s lines of evidence, including the perspectives of employers and other key stakeholders, have confirmed the importance of program changes made in recent years and provide additional insights for considerations going forward. Significant efforts were already in progress during the time of the evaluation to address highlighted areas of focus, including communication and service improvements for employers and enhanced processes for assessing labour market conditions and other program requirements. The program will strive for continuous improvement across all ESDC branches engaged in its design and delivery moving forward.

Recommendation 1

Better engage employers and key stakeholders on the objectives of the program.

Management response

Management agrees with the recommendation. The Temporary Foreign Worker Program works on an ongoing basis to strengthen communication of its objectives and requirements for program users, in addition to seeking out the perspectives of its diverse stakeholders to inform adjustments to policies and service delivery. In recent years, this has included updates to public information on evolving program rules and conditions, in addition to comprehensive stakeholder consultations undertaken during targeted sector reviews and the design of the Migrant Worker Support Network. More recently, the program’s response to COVID-19 has included the rapid provision of information on public health conditions and program requirements for employers and workers.