Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2016 and ending March 31, 2017 Chapter II - 5. Employment Insurance Work-Sharing benefits

From: Employment and Social Development Canada

On this page

5. Employment Insurance Work-Sharing benefits

During the period of an economic slowdown, some employers are faced with temporary reductions in the normal level of economic activities as a result of factors beyond their control. The Work-Sharing program is designed to provide support for both employers and workers facing such temporary reductions in economic activities, by helping them to avoid layoffs. Eligible employees who agree to work in a temporarily reduced work week while the business recovers can receive income support in the form of Employment Insurance (EI) Work-Sharing benefits, with the goal that all participating employees return to normal working levels when the Work-Sharing agreement ends. By participating in the Work-Sharing program, employers are able to retain skilled employees and thus can avoid the costly process of recruiting and training new employees once the business activities return to normal level. At the same time, participating workers can maintain their employment and skills by supplementing the reduced wages with Work-Sharing benefits for the days they are not working.

Normally, Work-Sharing agreements are signed for a duration period of between 6 to 26 weeks, which can be extended for up to 12 additional weeks (up to 38 weeks total) under exceptional circumstances, such as an unanticipated and prolonged period of economic contraction. In Budget 2016, the Government of Canada extended the maximum duration of Work-Sharing agreements from 38 weeks to 76 weeks, for agreements that began or ended between April 1, 2016 and March 31, 2017. This temporary special measure was put in place to assist employers and workers affected by the downturn in the commodities sector. To be eligible for Work-Sharing benefits, an affected group of employees in a particular work unit must experience a minimum 10% reduction in their normal weekly earnings, and available work is to be redistributed through a reduction in the hours worked by all employees within one or more work units of a company. Affected workers must be year-round employees, meet the eligibility criteria to receive EI regular benefits and must agree to a reduction in their normal amount of working hours in order to participate in a Work-Sharing agreement.

Example: Receiving Employment Insurance Work-Sharing benefits

Samantha works as a full-time employee at an engineering firm in the Mining and oil and gas extraction industry in Edmonton, Alberta, and earns $40,000 per year (weekly earnings of $769). Due to the global downturn in commodity prices, the firm faces significant reduction in workload because of decline in sales, and the possibility of laying off a quarter of its employees. The firm decides to enter into a Work-Sharing agreement with Service Canada, where all eligible employees in Samantha’s work unit agree to reduce their work hours per week by 35% and receive EI Work-Sharing benefits for days where they do not work as a result of the agreement.

If Samantha and her co-workers did not agree to voluntarily reduce their work hours to participate in the Work-Sharing program and were laid off, each of them would have been entitled to receive 55% of their weekly income ($423), by applying for EI regular benefits. By participating in the Work-Sharing program, Samantha and her co-workers receive 35% less of their regular weekly income (earning $500 per week); and collect EI benefits for that 35% of their average hours worked per week (equal to 55% of the value of the insurable earnings she would have received from the firm, which is $148).

By participating in the Work-Sharing program, Samantha and her co-workers are able to earn a total of $648 per week ($500 worth of income from working at the firm plus $148 from Work-Sharing benefits), compared to $423 if they had been on EI regular benefits following a layoff. By participating in the Work-Sharing program, Samantha and her co-workers are able to earn more and keep their jobs, and keep their skills up to date. At the same time, the firm is able to retain its skilled and experienced workforce.

For an employer to be eligible to participate, it must be a publicly-held company, private business or non-profit organization experiencing reductions in business activity that are beyond its control, and must be in operation year-round in Canada for at least two years prior to application. The employer is also required to implement a recovery plan to return affected work units to normal staffing levels and hours of work by the end of the agreement period. The employer must also employ a minimum of two EI-eligible employees within the affected work unit, and agreements must be signed by the employer, the affected employees and Service Canada. Employers who are experiencing a reduced-level of business activity attributable to a predictable seasonal shortage or any other recurring production slowdown are not eligible to participate in the Work-Sharing program. Those who are involved in work stoppages from a labour dispute are also not eligible to participate.

For the purpose of this section, EI Work-Sharing claims refers to any claims for which at least one dollar of Work-Sharing benefit was paid.

5.1 Employment Insurance Work-Sharing agreements

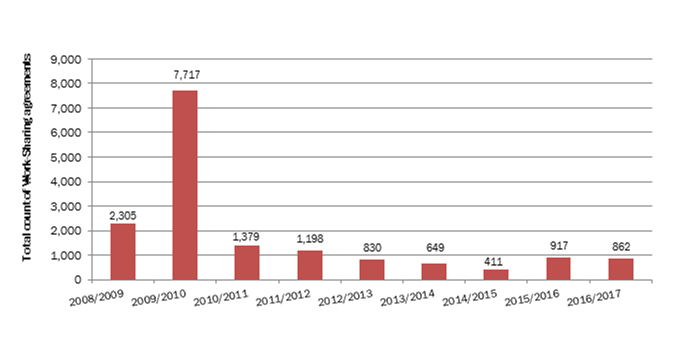

The number of Work-Sharing agreements established in a given fiscal year increases during periods of economic shocks and uncertainty, and decreases during periods of economic growth and stability. This countercyclical pattern can be observed by looking at the number of Work-Sharing agreements established in Canada in past few years (see Chart 32).

Show data table

| Canada | |

|---|---|

| 2008/2009 | 2,305 |

| 2009/2010 | 7,717 |

| 2010/2011 | 1,379 |

| 2011/2012 | 1,198 |

| 2012/2013 | 830 |

| 2013/2014 | 649 |

| 2014/2015 | 411 |

| 2015/2016 | 917 |

| 2016/2017 | 862 |

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada, Common System of Grants and Contributions.

The total number of Work-Sharing agreements decreased slightly from 917 agreements established in FY1516 to 862 agreements in FY1617, which is consistent with the recovery of the Canadian economy that was observed in the reporting period examined (see Chapter 1). The number of agreements decreased in Central and Western provinces except Alberta, with the largest decrease reported in Quebec (-26 agreements) and British Columbia (-21 agreements). On the other hand, among the Atlantic provinces, Nova Scotia reported the largest increase (+8 agreements) followed by Newfoundland and Labrador (+2 agreements). There was no change in the number of Work-Sharing agreements in Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick in FY1617 compared to the previous fiscal year. Same as the previous fiscal year, the highest number of Work-Sharing agreements was established in Alberta (458 agreements), representing 53.1% of the all agreements.

Continuing with the trend observed in previous years, the goods-producing industries represented the majority of all Work-Sharing agreements established in FY1617 (see Table 40). The share of Work-Sharing agreements in the goods-producing increased from 69.6% in FY1516 to 70.3% in FY1617. Consistent with previous years, the Manufacturing industry reported the largest number of Work-Sharing agreements (426 agreements), equivalent to 49.4% of all agreements established in the fiscal year examined. The Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extractions industry, and the Construction industry reported significant increase in the number of agreements established in FY1617 compared to the previous fiscal year (+34 agreements for both industries). The total number of Work-Sharing agreements in the services-producing industries decreased from 279 agreements in FY1516 to 256 agreements in FY1617. The Wholesale trade industry and the Professional, scientific, and technical services industry had a decrease in the number of agreements established (-15 agreements and -18 agreements, respectively) while the Retail trade industry had small increase (+5 agreements).

| 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | 2015/2016 | 2016/2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goods-producing industries | 810 (67.6%) |

569 (68.5%) |

446 (68.7%) |

267 (65.0%) |

638 (69.6%) |

606 (70.3%) |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extract | 3 (0.3%) |

7 (0.8%) |

20 (3.1%) |

6 (1.5%) |

56 (5.8%) |

90 (10.4%) |

| Construction | 67 (5.6%) |

41 (4.9%) |

36 (5.5%) |

28 (6.8%) |

52 (5.7%) |

86 (10.0%) |

| Manufacturing | 727 (60.7%) |

512 (61.7%) |

382 (58.9%) |

227 (55.2%) |

526 (57.4%) |

426 (49.4%) |

| Services-producing industries | 388 (32.4%) |

261 (31.4%) |

203 (31.3%) |

144 (35.0%) |

279 (30.4%) |

256 (29.7%) |

| Wholesale trade | 88 (7.3%) |

43 (5.2%) |

44 (6.8%) |

34 (8.3%) |

80 (8.7%) |

65 (7.5%) |

| Retail trade | 75 (6.3%) |

47 (5.7%) |

24 (3.7%) |

17 (4.1%) |

21 (2.3%) |

26 (3.0%) |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 93 (7.8%) |

76 (9.2%) |

79 (12.2%) |

55 (13.4%) |

84 (9.2%) |

66 (7.7%) |

| Rest of services-producing industries | 132 (11.0%) |

95 (11.4%) |

56 (8.6%) |

38 (9.2%) |

94 (10.3%) |

99 (11.5%) |

| Canada | 1,198 (100.0%) |

830 (100.0%) |

649 (100.0%) |

411 (100.0%) |

917 (100.0%) |

862 (100.0%) |

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada, Common System of Grants and Contributions.

When assessed by firm size, small-sized enterprises (with fewer than 50 employees) comprised 78.4% of all Work-Sharing agreements in the fiscal year examined, up from 76.6% reported in the previous fiscal year. Combined, small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) with fewer than 500 employees accounted for 99.4% of all Work-Sharing agreements in FY1617, which is similar to the level in the previous fiscal year (99.2%). The number of Work-Sharing agreements involving large-sized enterprise (with 500 employees or more) dropped from seven agreements in FY1516 to only five agreements in FY1617. This was consistent with the general trend observed since the 2008 recession, as Work-Sharing agreements have been primarily initiated to assist SMEs in recovering from economic shocks to their normal levels of business activity.

5.2 Employment Insurance Work-Sharing claims and amount paid

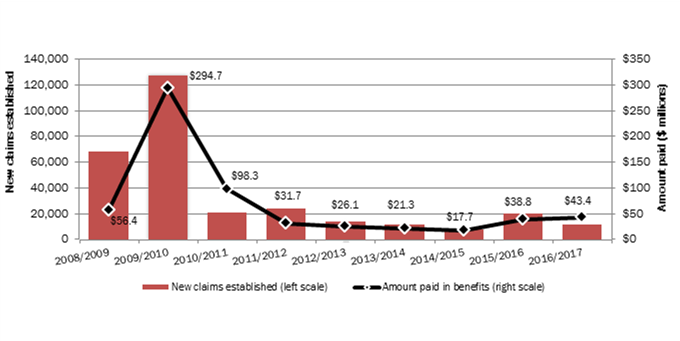

The use of Work-Sharing benefits is linked to the trends observed in Work-Sharing agreements, and is countercyclical to economic conditions (similar to the number of new claims established and amounts paid under EI regular benefits). As with the number of Work-Sharing agreements, the total number of Work-Sharing claims established and the total amounts paid in Work-Sharing benefits increase during labour market contraction and economic uncertainties, and decrease during periods of economic expansion.

Chart 33 illustrates the number of Work-Sharing claims and benefits paid from FY0809 to FY1617. The number of Work-Sharing claims and benefits paid peaked to just over 127,000 claims and $294.7 million paid in FY0910, corresponding to the recession in 2008 and the temporary Employment Insurance changes introduced in response, such as extending agreement duration, streamlining the administrative process and easing eligibility requirements for employers.Footnote 90 The number of Work-Sharing claims has declined significantly since then as the economy began to recover after the recession, before increasing once again in FY1516 when the number of Work-Sharing claims (20,500 claims) more than doubled from the previous fiscal year (8,000 claims). This was attributable to the downturn in global commodity prices which represented an external economic shock impacting many firms in affected industries and commodity-based regions that experienced sudden and unexpected declines in business activity. In FY1617, the total number of Work-Sharing claims established declined significantly (-41.8%) from the previous fiscal year to 11,900 claims, reflecting the improved economic conditions observed in the fiscal year examined.

Show data table

| Work-Sharing claims (left scale) | Amount paid in benefits ($ millions) (right scale) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2008/2009 | 68,437 | $56.4 |

| 2009/2010 | 127,033 | $294.7 |

| 2010/2011 | 20,929 | $98.3 |

| 2011/2012 | 23,755 | $31.7 |

| 2012/2013 | 13,890 | $26.1 |

| 2013/2014 | 11,673 | $21.3 |

| 2014/2015 | 8,024 | $17.7 |

| 2015/2016 | 20,521 | $38.8 |

| 2016/2017 | 11,936 | $43.4 |

- Note: Includes all claims for which at least $1 of Work-Sharing benefits was paid.

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 100% sample of EI administrative data.

The total amount paid in Work-Sharing benefits increased from $38.8 million in FY1516 to $43.4 million in FY1617, representing an increase of 11.9%. While the total amount paid in Work-Sharing benefits increased for the second consecutive year, it was still well below the peak of $294.7 million observed in FY0910.

The average number of beneficiariesFootnote 91 receiving Work-Sharing benefits each month increased from 5,530 in FY1516 to 6,780 in FY1617, even though the total number of new claims established had declined during the same time period. This explains the increase in the total amount paid in Work-Sharing benefits in FY1617 compared to the previous fiscal year. Chart 34 outlines the average number of beneficiaries receiving Work-Sharing benefits over the last decade. The increase in the average number of Work-Sharing beneficiaries in FY1617 represents the second consecutive yearly increase, after declining for five years since FY1011.

Show data table

| Average number of beneficiaries | |

|---|---|

| 2008/2009 | 9,554 |

| 2009/2010 | 52,694 |

| 2010/2011 | 21,299 |

| 2011/2012 | 6,189 |

| 2012/2013 | 4,706 |

| 2013/2014 | 3,636 |

| 2014/2015 | 2,685 |

| 2015/2016 | 5,526 |

| 2016/2017 | 6,781 |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, CANSIM table 276-0020.

Employment Insurance Work-Sharing claims and amount paid, by province, gender, age and industry

In FY1617, all regions reported a decrease in the number of Work-Sharing claims established, compared to the previous fiscal year. This reflects the economic rebound that was observed in Canada in FY1617 after the downturn in commodity prices in the previous year. As outlined in Table 41, the most notable decline was in Alberta (-3,067 claims), where the number of new claims had peaked to 7,939 claims in FY1516 from only 631 claims in FY1415.

| New claims established | Amount paid ($ millions) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015/2016 | 2016/2017 | 2015/2016 | 2016/2017 | |

| Region | ||||

| Atlantic provinces | 302r (1.5%) |

212 (1.8%) |

$0.5 (1.2%) |

$0.9 (2.2%) |

| Quebec | 4,451 (21.7%) |

2,737 (22.9%) |

$6.0 (15.3%) |

$6.5 (15.0%) |

| Ontario | 2,849 (13.9%) |

2,017 (16.9%) |

$5.3 (13.6%) |

$4.7 (10.9%) |

| Manitoba and Saskatchewan | 3,517 (17.1%) |

1,492 (12.5%) |

$6.3 (16.2%) |

$5.3 (12.3%) |

| Alberta | 7,939 (38.7%) |

4,872 (40.8%) |

$17.1 (43.9%) |

$23.5 (54.1%) |

| British Columbia | 1,463 (7.1%) |

606 (5.1%) |

$3.8 (9.7%) |

$2.4 (5.4%) |

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 15,933 (77.6%) |

8,883 (74.4%) |

$30.5 (78.6%) |

$32.3 (74.4%) |

| Women | 4,588 (22.4%) |

3,053 (25.6%) |

$8.3 (21.4%) |

$11.1 (25.6%) |

| Age category | ||||

| 24 years old and under | 1,425 (6.9%) |

718 (6.0%) |

$2.4 (6.2%) |

$2.3 (5.3%) |

| 25 to 54 years old | 15,002 (73.1%) |

8,691 (72.8%) |

$29.1 (75.0%) |

$32.5 (74.9%) |

| 55 years old and over | 4,094 (20.0%) |

2,527 (21.2%) |

$7.3 (18.8%) |

$8.6 (19.8%) |

| Industry | ||||

| Goods-producing industries | 15,612 (76.1%) |

9,315 (78.0%) |

$27.6 (71.1%) |

$30.1 (69.3%) |

| Manufacturing | 14,431 (70.3%) |

8,474 (71.0%) |

$25.1 (64.7%) |

$27.4 (63.1%) |

| Rest of goods-producing industries | 1,181 (5.8%) |

841 (7.0%) |

$2.5 (6.4%) |

$2.7 (6.2%) |

| Service-producing industries | 4,869 (23.7%) |

2,439 (20.4%) |

$11.2 (28.8%) |

$12.8 (29.4%) |

| Wholesale trade | 2,026 (9.9%) |

1,017 (8.5%) |

$3.9 (9.9%) |

$3.8 (8.7%) |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 1,069 (5.2%) |

543 (4.5%) |

$2.7 (6.9%) |

$2.6 (5.9%) |

| Rest of service-producing industries | 1,774 (8.6%) |

879 (7.4%) |

$4.6 (11.9%) |

$6.5 (14.9%) |

| Canada | 20,521 (100.0%) |

11,936 (100.0%) |

$38.8 (100.0%) |

$43.4 (100.0%) |

- Note: Data may not add up to the total due to rounding. Percentage share is based on unrounded numbers. Includes claims for which at least $1 of EI Work-Sharing benefits was paid. No Work-Sharing claim was established in the Northwest Territories, Yukon or Nunavut in FY1516 or FY1617.

- r Revised data.

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 100% sample of EI administrative data.

Quebec (-1,714 claims) and Manitoba (-1,567 claims) were two other provinces that also reported significant declines in new claims established. However, Alberta continued to represent the largest share of total new claims established (40.8%) and of total amount paid (54.1%) in FY1617.

Men continue to be more likely to make use of the Work-Sharing program—a trend that has been persistent over the years. In FY1617 men accounted for 74.4% of new Work-Sharing claims and total benefits paid, down from 77.6% of claims and 78.6% of benefits paid in the previous fiscal year. Workers aged 25 to 54 years accounted for 72.8% of all new Work-Sharing claims and 74.9% of Work-Sharing benefits paid. Same as the previous fiscal year, youth were under-represented among new Work-Sharing claims established (6.0%) and benefits paid (5.3%) compared with their total share of employment (14.3%) in FY1617.Footnote 92

From the industry perspective, the Work-Sharing program was most frequently used by workers in the Manufacturing industry, which is consistent with historical patterns. Employees in the Manufacturing industry accounted for 71.0% of new EI Work-Sharing claims in FY1617, up from 70.3% in the previous fiscal year. These workers accounted for 63.1% of the total EI Work-Sharing benefits paid, down from 64.7% FY1516 (see Table 41), which was disproportionate to their share of total employment (9.5% in FY1516 and 9.3% in FY1617).Footnote 93 Among the services-producing industries, workers in the Wholesale trade industry accounted for the largest share of Work-Sharing claims (8.5%) and total Work-Sharing benefits paid (8.7%) in FY1617. This was closely followed by workers in the Professional, scientific and technical services industry, who accounted for 4.5% of new Work-Sharing claims and 5.9% of total Work-Sharing benefits paid in FY1617. See Annex 2.21.1 for detailed information on new claims established and Annex 2.21.4 for amount paid by industry.

5.3 Level and duration of Employment Insurance Work-Sharing benefits

The Work-Sharing program is designed to provide income support for workers in firms that experience temporary reductions in demand for reasons beyond the employer’s control. As such, the program provides partial income stabilization to offset reductions in hours that is agreed upon by the employees participating in the program, but is not meant to provide full coverage of insurable hours or insurable earnings. As a result, the data reported on Work-Sharing claims are not directly comparable to other types of EI benefits. This is particularly true of the weekly benefit rates paid to claimants, which are meant to only cover up to 60% of a regular work weeks for affected employees in a work unit subject to a Work-Sharing agreement depending on the agreed upon decrease in work levels. Because of this, the weekly benefit rates for Work-Sharing claimants are lower on average than for other types of EI benefits. Because the weekly Work-Sharing benefit rate is determined by the employees wage and the degree of reductions in the hours worked, significant variability is also observed across industries in the reported weekly benefit rates.

In FY1617, the average weekly Work-Sharing benefit rate was $125, down from the average weekly benefit rate of $131 in the previous fiscal year (see Table 42). This represents a decrease of 4.6% in the average weekly benefit rate after increasing for four previous consecutive years. Similar to the previous years, a high degree of variability can be observed among the average weekly benefit paid in each province in the fiscal year examined; for example, the highest average weekly benefit rate was in Prince Edward Island ($211) while the lowest was in Manitoba ($101). The average weekly Work-Sharing benefit rate for both men and women decreased in FY1617 compared to the previous fiscal year. Men received an average weekly benefit rate of $131 in FY1617, down from $136 in FY1516; while women received an average weekly benefit rate of $107 in FY1617, down from $115 in FY1516. The average weekly benefit was $126 for workers who were aged 25 to 54 years, a little higher than for workers aged 24 years and under ($120) and those aged 55 years and older ($124).

| 2015/2016 | 2016/2017 | Change (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Region | |||

| Atlantic provinces | $142 | $153 | +7.7% |

| Quebec | $116 | $113 | -2.6% |

| Ontario | $117 | $118 | +0.9% |

| Manitoba and Saskatchewan | $126 | $116 | -7.9% |

| Alberta | $142 r | $137 | -3.5% |

| British Columbia | $150 r | $114 | -24.0% |

| Gender | |||

| Male | $136 | $131 | -3.7% |

| Female | $115 | $107 | -7.0% |

| Age category | |||

| 24 years old and under | $133 | $120 | -9.8% |

| 25 to 54 years old | $131 | $126 | -3.8 |

| 55 years old and over | $129 | $124 | -3.9% |

| Industry | |||

| Goods-producing industries | $132 | $124 | -6.1% |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | $142 | $116 | -18.3% |

| Mining and oil and gas extraction | $152 | $126 | -17.1% |

| Manufacturing | $130 | $122 | -6.2% |

| Average of other goods-producing industries | $153 | $148 | -3.3% |

| Services-producing industries | $129 | $129 | 0.0% |

| Wholesale trade | $109 | $111 | +1.8% |

| Accommodation and food services | $211 | $125 | -40.8% |

| Other services (excl. public administration) | $158 | $151 | -4.4% |

| Average of other services-producing industries | $134 | $140 | +4.5% |

| Canada | $131 | $125 | -4.6% |

- Note: Percentage change is based on unrounded numbers. Includes claims for which at least $1 of Work-Sharing benefits was paid. No Work-Sharing claim was established in the Northwest Territories, Yukon or Nunavut in FY1516 or FY1617.

- r Revised data.

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 100% sample of EI administrative data.

The average weekly Work-Sharing benefit rate in the goods-producing industries declined by 6.1% to $124 in FY1617, from $132 reported in the previous fiscal year (see Table 42). Workers in the Construction industry received the highest amount of average weekly benefits ($148) in the goods-producing sector. On the other hand, the average weekly Work-Sharing benefit rate remained unchanged in FY1617 from the previous fiscal year at $129 in the service-producing industries. The largest decline in the average weekly benefit rate in FY1617 was observed in the Accommodation and food services industry (-40.8%). See Annex 2.21.3 for detailed information on average Work-Sharing weekly benefit rate by industry.

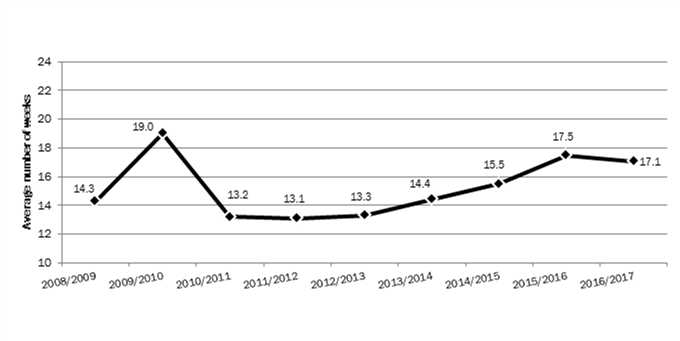

The average durationFootnote 94 of Work-Sharing claims established in FY1617 was 17.1 weeks, a decrease of 0.4 weeks from FY1516 (17.5 weeks). This represents a decline in the average duration of Work-Sharing claims after steadily rising since FY1112 (see Chart 35).

Show data table

| Average duration (weeks) | |

|---|---|

| 2008/2009 | 14.3 |

| 2009/2010 | 19.0 |

| 2010/2011 | 13.2 |

| 2011/2012 | 13.1 |

| 2012/2013 | 13.3 |

| 2013/2014 | 14.4 |

| 2014/2015 | 15.5 |

| 2015/2016 | 17.5 |

| 2016/2017 | 17.1 |

- Note: Includes all claims for which at least $1 of EI Work-Sharing benefits was paid.

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada, Employment Insurance (EI) administrative data. Data are based on a 100% sample of EI administrative data.

5.4 Employment Insurance Work-Sharing agreements subject to early termination

When a firm returns to normal levels of business activity ahead of recovery plan timelines, or withdraws from the Work-Sharing agreement for other reasons (such as it is closing down or deciding to go ahead with layoffs), the Work-Sharing agreements end before the anticipated end date of the agreement—this is referred to as early termination. Of the 862 Work-Sharing agreements established in FY1617 by firms across Canada, a total of 110 agreements were terminated earlier than their scheduled end date (12.8% of all agreements). This proportion increased from FY1516 (6.3%) and was the highest in the past five fiscal years, but was still much lower than the proportion reported in FY1011 (38.1%). Of the 110 early terminated agreements in FY1617, 82 agreements (9.5% of total Work-Sharing agreements) concluded because these firms returned to their normal level of employment, while the other 28 agreements (3.2% of total Work-Sharing agreements) concluded because the firms did not return to normal levels of employment (see Table 43).

| Count | Share of all Work-Sharing agreements |

|

|---|---|---|

| Agreements terminated on schedule | 752 | 87.2% |

| Agreements terminated earlier than scheduled end date | 110 | 12.8% |

| Early termination because level of employment returned to normal levels | 82 | 9.5% |

| Early termination with employment not returning to normal levels | 28 | 3.2% |

| Canada | 862 | 100.0% |

- Source: Employment and Social Development Canada, Common System for Grants and Contributions.

Effectiveness of the Work-Sharing program over the years

A recent study* looked at the usage of the Work-Sharing program since 2000 and estimated the number and distribution of layoffs averted by the Work-Sharing program, and the number of employers’ shutdowns who participated in the program. The study found that Work-Sharing claims that started at the beginning of a recession and that ended during it were most likely associated with a layoff after the agreement had terminated, whereas claims that started once the recession was already underway and ended as the economy recovered were less likely associated with a subsequent layoff. For example, during the economic slowdown in 2001, the proportion of net layoffs averted** improved from 34% in FY0001 to 67% in FY0102. Again during the 2008 recession, the proportion of net layoffs averted improved from 26% in FY0708 to 51% in FY0809, and 69% in FY0910. Following the economic slowdown because of the decline in commodity prices in FY1415, the proportion of net layoffs averted improved from 42% in FY1415 to 58% in FY1516.

The study also looked at the incidence of shutdowns among employers who participated in the Work-Sharing program and those who did not. It was found that in the short to medium term, the cumulative shutdown rate among non-Work-Sharing employers was about six percentage points higher than for employers who participated in the program. The shutdown rate for non-Work-sharing employers was almost 20 percentage points higher than for participating employers in the longer term.

* ESDC, Usage of the Work-Sharing Program: 2000 to 2001 to 2016 to 2017 (Ottawa: ESDC, Evaluation Directorate, 2018).

** The methodology used to estimate the number of layoffs averted assumes a perfect substitution between one hour of work reduction with the Work-Sharing program and one hour of work reduction through the layoff alternative (a conversion rate of 1.0). The number of layoffs that occurred subsequent to the program was subtracted from the estimated number of layoffs averted to calculate the net layoffs averted.