Chapter 1: Labour market context

From: Employment and Social Development Canada

Official title: Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2018 and ending March 31, 2019: Chapter 1: Labour market context

In chapter 1

List of abbreviations

This is the complete list of abbreviations for the Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2018 and ending March 31, 2019.

Abbreviations

- ASETS

- Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy

- ATSSC

- Administrative Tribunals Support Service of Canada

- B/C Ratio

- Benefits-to-Contributions ratio

- B/U Ratio

- Benefits-to-Unemployed ratio

- B/UC Ratio

- Benefits-to-Unemployed Contributor ratio

- BDM

- Benefit Delivery Modernization

- CANSIM

- Canadian Socio-Economic Information Management System

- CAWS

- Citizen Access Workstation Services

- CCAJ

- Connecting Canadians with Available Jobs

- CCB

- Canada Child Benefit

- CCDA

- Canadian Council of Directors of Apprenticeship

- CEIC

- Canada Employment Insurance Commission

- COLS

- Community Outreach and Liaison Service

- CSO

- Citizen Service Officer

- CPI

- Consumer Price Index

- CPP

- Canada Pension Plan

- CRA

- Canada Revenue Agency

- CRF

- Consolidated Revenue Fund

- CUSMA

- Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement

- CX

- Client Experience

- EBSMs

- Employment Benefits and Support Measures

- ECC

- Employment Contact Centre

- EF

- Enabling Fund

- EI

- Employment Insurance

- EI PAAR

- Employment Insurance Payment Accuracy Review

- EI PRAR

- Employment Insurance Processing Accuracy Review

- EICS

- Employment Insurance Coverage Survey

- eROE

- Electronic Record of Employment

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- FLMM

- Forum of Labour Market Ministers

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- G7

- Group of Seven

- GDP

- Gross Domestic Product

- HCCS

- Hosted Contact Centre Solution

- HRSDC

- Human Resources and Social Development Canada

- IQF

- Individual Quality Feedback

- IVR

- Interactive Voice Response

- LFS

- Labour Force Survey

- LMDA

- Labour Market Development Agreements

- LMI

- Labour Market Information

- LMP

- Labour Market Partnerships

- MIE

- Maximum Insurable Earnings

- MSCA

- My Service Canada Account

- NAICS

- North American Industry Classification System

- NAFTA

- North American Free Trade Agreement

- NAS

- National Apprenticeship Survey

- NERE

- New-Entrant/Re-Entrant

- NESI

- National Essential Skills Initiative

- NIS

- National Investigative Services

- NOS

- National Occupational Standards

- NQCP

- National Quality and Coaching Program for Call Centres

- OAS

- Old Age Security

- OECD

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PPEs

- Clients who are Premiums Paid Eligible

- P/Ts

- Provinces and Territories

- PPTS

- Percentage points

- PRP

- Premium Reduction Program

- QPIP

- Quebec Parental Insurance Plan

- RAIS

- Registered Apprenticeship Information System

- ROE

- Record of Employment

- RSOS

- Red Seal Occupational Standards

- SA

- Social Assistance

- SCC

- Service Canada Centres

- SDP

- Service Delivery Partner

- SEPH

- Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours

- SIN

- Social Insurance Number

- SIR

- Social Insurance Registry

- SME

- Small and medium sized enterprises

- SO

- Scheduled Outreach

- SST

- Social Security Tribunal

- STDP

- Short-term disability plan

- SUB

- Supplemental Unemployment Benefit

- UV

- Unemployed-to-job-vacancy ratio

- VBW

- Variable Best Weeks

- VER

- Variable Entrance Requirement

- WWC

- Working While on Claim

Introduction – Chapter 1

This chapter outlines the overall economic situation and key labour market developments in Canada during the fiscal year beginning on April 1, 2018 and ending on March 31, 2019 (FY1819), the period for which this Report assesses the Employment Insurance (EI) program.Footnote 1 Section 1.1 provides a general overview of the economic situation for FY1819 as well as a historical context. Section 1.2 summarizes key labour market developments in the Canadian economy.Footnote 2 Section 1.3 discusses trends in non-standard employment in Canada, and the socio-demographic and labour market characteristics of individuals working in such work arrangements.

1.1 Economic overview

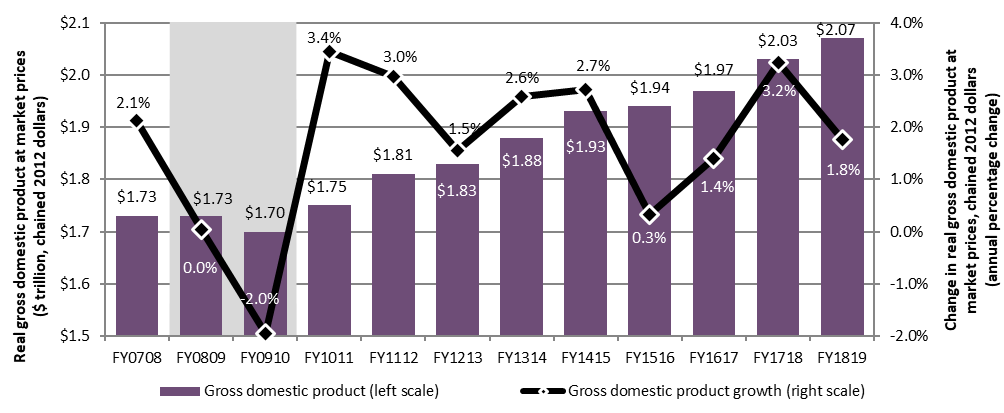

The size of real gross domestic product (GDP) in Canada reached $2.07 trillionFootnote 3 in the fiscal year beginning on April 1, 2018 and ending on March 31, 2019 (FY1819)—an increase of 1.8% compared to the previous fiscal year (see Chart 1). The real GDP growth slowed down in the reporting year after reaching the highest year-over-year growth observed last year since FY1011. On a quarterly basis, growth in real GDP was almost flat (+0.2%) in the last 2 quarters of FY1819, the slowest pace observed since the first quarter of FY1617. The slowdown in FY1819 is attributable to the weaker growth in household final consumption expenditure (+1.8% in FY1819, compared to +3.8% observed in FY1718) and the decline in business investments (gross fixed capital formation declined by $3.1 billion in the reporting fiscal year compared to the previous fiscal year). However, growth in exports of goods and services increased to +3.3% in FY1819, from the moderate growth observed in the previous fiscal year (+1.6%),Footnote 4 despite the uncertainty regarding the new Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) that is set to replace the existing North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).Footnote 5

By industry classification,Footnote 6 all industries experienced growth in terms of real GDP in FY1819 compared to the previous fiscal year, except for the Construction industry, which shrank by 1.2%. The Professional, scientific and technical services industry saw the largest growth in terms of real GDP (+3.5%), followed by the Health care and social assistance industry (+3.3%) and Public administration industry (+3.1%) (see Annex 1.3 for change in real GDP by industry in FY1819 from the previous fiscal year).

Chart 1 – Text description

| Fiscal year | Gross domestic product (left scale) | Gross domestic product growth (right scale) |

|---|---|---|

| FY0708 | 1.73 | 2.1% |

| FY0809 | 1.73 | 0.0% |

| FY0910 | 1.70 | -2.0% |

| FY1011 | 1.75 | 3.4% |

| FY1112 | 1.81 | 3.0% |

| FY1213 | 1.83 | 1.5% |

| FY1314 | 1.88 | 2.6% |

| FY1415 | 1.93 | 2.7% |

| FY1516 | 1.94 | 0.3% |

| FY1617 | 1.97 | 1.4% |

| FY1718 | 2.03 | 3.2% |

| FY1819 | 2.07 | 1.8% |

- Note: Shaded area(s) correspond to recessionary period(s) in Canada’s economy.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0104-01.

When compared to other Group of Seven (G7) countries—a group consisting of the world’s major industrialized and advanced economies—Canada ranked third in terms of real GDP per capita (approximately USD 45,800 in FY1819 using the fixed Purchasing Power ParityFootnote 7), behind United States and Germany.Footnote 8 However, Canada’s real GDP per capita grew only 0.3% in FY1819 compared to the previous fiscal year—the lowest among all G7 nations during this period.Footnote 9

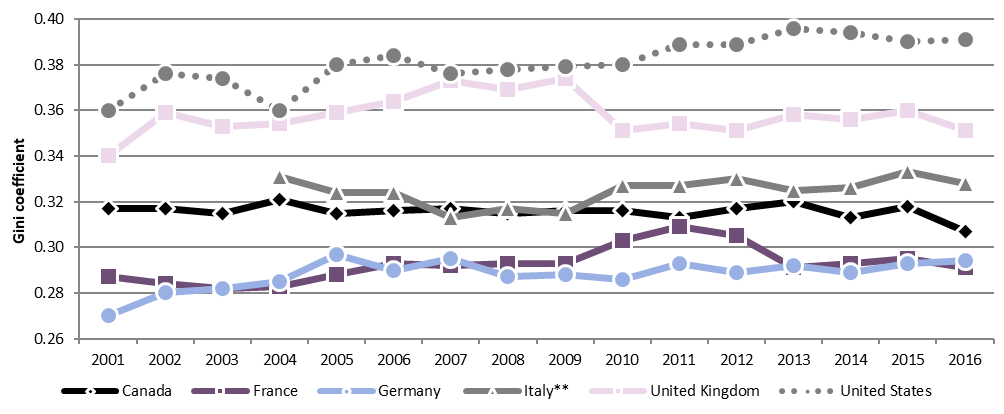

While the real GDP per capita, when measured in the same currency, is often used as a measure of standard of living among countries, it is not an adequate measure of well-being of individuals as it does not reveal any information on the distribution of income or wealth at different segments of the population. A measure of income inequality, on the other hand, shows the relative gap between the richest and the rest of the population. Rising income inequality has been found to have negative effects on long-term economic growths and improved social outcomes.Footnote 10 Chart 2 illustrates the income inequalityFootnote 11 in Canada and other G7 countries (except Japan, due to lack of available data) from 2001 to 2016. Canada ranks third in terms of equal distribution of income among its population, behind Germany and France in 2016 (the most recent available year). Over the years, the income inequality in Canada has remained steady while it declined to the lowest level observed in 2016 within this period.

Chart 2 – Text description

| Country | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.31 |

| France | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.29 |

| Germany | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| Italy | not available | not available | not available | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| United Kingdom | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.35 |

| United States | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.39 |

- * Based on household disposable income, post taxes and transfers.

- ** Data not available for Italy from 2001 to 2003.

- Source: OECD, Social and Welfare Statistics, Income distribution, August 2019.

1.2 The Canadian labour market in FY1819

In this section

The size of Canada’s labour forceFootnote 12 grew to 19.9 million in FY1819, up from 19.7 million in the previous fiscal year (+207,600 or +1.1%).Footnote 13 All provinces during this period experienced positive change in the size of their labour force except Newfoundland and Labrador, where the labour force shrank by 0.2%.Footnote 14 The most prominent increase in the size of labour force was observed in Ontario (+1.8%), followed by Prince Edward Island (+1.7%), Manitoba (+1.3%) and British Columbia (+1.1%). Growth in the remaining provinces were relatively modest.

In the reporting fiscal year, there were 18.7 million employed persons in Canada, up from 18.5 million in FY1718 (+1.4%). The growth in employment weakened slightly in FY1819 compared to the one observed in FY1718 (+1.8%), attributable to the slow down in growth of full-time employment (+1.7% growth in FY1819 compared with +2.2% growth in FY1718)—see Annex 1.2 for key labour market statistics in the past 5 years. Canada ranked third among G7 nations in terms of employment growth in the reporting fiscal year, behind Japan (+1.7%) and United States (+1.5%). During this period, growth in part-time employment in Canada remained relatively unchanged (+0.3% growth in FY1819 compared with +0.4% growth in FY1718). By class of worker,Footnote 15 job creation in terms of the number of employees in FY1819 was higher in the public sector (+1.7%) compared to the private sector (+1.4%), while the number of self-employed person in Canada had a moderate increase during this period (+0.9%).Footnote 16

By enterprise size,Footnote 17 small-medium-sized and large-sized firms had similar employment growth in FY1819 (+2.1% and +2.7%, respectively), while it was higher in medium-large-sized firms (+3.7%).Footnote 18 Small-sized firms, on the other hand, had the lowest employment growth in FY1819 (+0.6%) compared to the previous fiscal year. Both small-sized and small-medium-sized firms accounted for around one-fifth (19.6%) of the total number of employees while medium-large-sized firms had the lowest share (15.5%) in FY1819. Large-sized firms continued to have the highest share of all employees in Canada (45.3%), relatively unchanged over recent years.

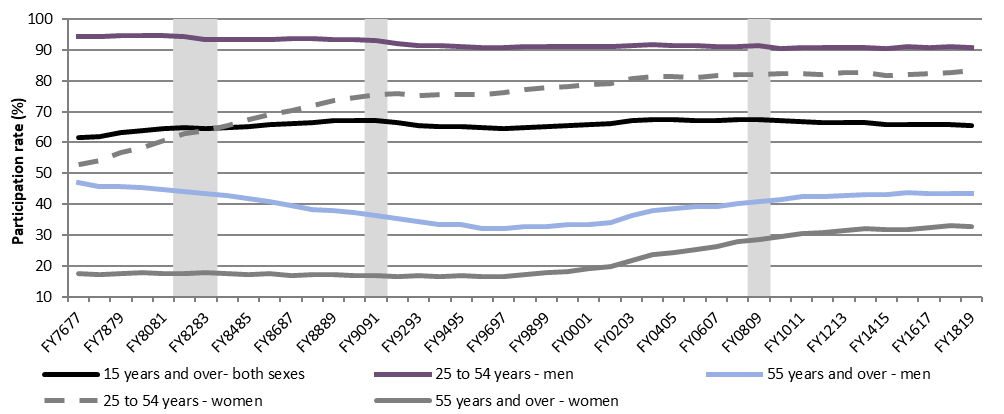

The employment rate,Footnote 19 which can be used as a measure of the extent to which available labour resources are being utilized, was 61.7% in FY1819—relatively unchanged in the past 10 fiscal years. Historically, the employment rate for men has been higher than that for women—in the reporting fiscal year, the employment rate for men was 65.4%, compared to 58.0% for women. By age groups, the employment rate was the highest for core-aged workers (aged 25 to 54) at 82.9%, and the lowest (35.9%) for older workers (aged 55 and over). Notably, the employment rate for older workers has been rising steadily over the past 2 decades, from 23.2% in FY9899 to 35.9% in FY1718 and FY1819. Educational attainment also plays an important role in employability—in FY1819, individuals with an education level above the bachelor’s degree had an employment rate of 74.0%, whereas those with primary education or lowerFootnote 20 had an employment rate of 20.0%. This contrast in employment rates can be explained by the over-representation of older individuals among people with lower educational attainment—in FY1819, the employment rate for older individuals with primary education or lower was 11.7%, compared to 50.9% for core-aged individuals with the same educational level. Similarly, core-aged workers are over-represented among people with education level above bachelor’s degree—the employment rate for core-aged individuals in this case was 87.3% in FY1819, compared to 48.2% for older individuals. Another metric used to estimate labour market conditions is the participation rate, which measures the total labour force relative to the size of the working-age population.Footnote 21 The overall participation rate in FY1819 in Canada was 65.5%, relatively unchanged from the rate observed in the previous fiscal year (65.7%). The participation rate has been on a downward trend particularly over the past decade—down from 67.5% in FY0809—indicative of an aging population.Footnote 22 The participation rate for men has been historically higher than that for women; however, this gap has been shrinking over the past 4 decades, especially among core-aged and older individuals (see Chart 3). The increase in participation rate is particularly evident for core-aged women (from 52.7% in FY7677 to 83.5% in FY1819), while for older women it almost doubled over this period (from 17.6% in FY7677 to 32.8% in FY1819).

Chart 3 – Text description

| Fiscal year | 15 years and over- both sexes | 25 to 54 years - men | 55 years and over - men | 25 to 54 years – women | 55 years and over - women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY7677 | 61.6 | 94.4 | 46.8 | 52.7 | 17.6 |

| FY7778 | 62.0 | 94.3 | 45.9 | 54.2 | 17.3 |

| FY7879 | 63.1 | 94.7 | 45.8 | 56.9 | 17.4 |

| FY7980 | 63.9 | 94.6 | 45.4 | 58.4 | 18.0 |

| FY8081 | 64.4 | 94.5 | 44.7 | 60.5 | 17.5 |

| FY8182 | 65.0 | 94.4 | 44.1 | 63.0 | 17.6 |

| FY8283 | 64.4 | 93.5 | 43.3 | 63.7 | 17.7 |

| FY8384 | 64.8 | 93.4 | 42.7 | 65.5 | 17.4 |

| FY8485 | 65.2 | 93.4 | 41.8 | 67.3 | 17.3 |

| FY8586 | 65.8 | 93.5 | 40.9 | 69.2 | 17.5 |

| FY8687 | 66.2 | 93.6 | 39.5 | 70.5 | 16.7 |

| FY8788 | 66.6 | 93.8 | 38.4 | 71.9 | 17.3 |

| FY8889 | 67.0 | 93.4 | 38.0 | 73.5 | 17.1 |

| FY8990 | 67.2 | 93.4 | 37.3 | 74.7 | 16.7 |

| FY9091 | 67.1 | 93.1 | 36.3 | 75.6 | 16.8 |

| FY9192 | 66.3 | 92.1 | 35.3 | 75.8 | 16.6 |

| FY9293 | 65.6 | 91.4 | 34.4 | 75.2 | 16.7 |

| FY9394 | 65.3 | 91.3 | 33.4 | 75.6 | 16.7 |

| FY9495 | 65.2 | 91.2 | 33.4 | 75.6 | 17.0 |

| FY9596 | 64.7 | 90.9 | 32.1 | 75.6 | 16.6 |

| FY9697 | 64.7 | 90.8 | 32.2 | 76.2 | 16.7 |

| FY9798 | 64.9 | 91.0 | 32.8 | 77.1 | 17.2 |

| FY9899 | 65.3 | 91.1 | 32.7 | 77.7 | 17.9 |

| FY9900 | 65.6 | 91.1 | 33.4 | 78.3 | 18.3 |

| FY0001 | 65.9 | 91.1 | 33.3 | 78.6 | 19.1 |

| FY0102 | 66.1 | 91.1 | 34.1 | 79.3 | 19.8 |

| FY0203 | 67.1 | 91.6 | 36.3 | 80.6 | 21.6 |

| FY0304 | 67.6 | 91.6 | 38.0 | 81.4 | 23.6 |

| FY0405 | 67.4 | 91.6 | 38.5 | 81.5 | 24.3 |

| FY0506 | 67.1 | 91.4 | 39.2 | 81.0 | 25.2 |

| FY0607 | 67.2 | 91.1 | 39.3 | 81.6 | 26.4 |

| FY0708 | 67.5 | 91.2 | 40.3 | 82.0 | 27.7 |

| FY0809 | 67.5 | 91.4 | 40.7 | 82.0 | 28.6 |

| FY0910 | 67.0 | 90.6 | 41.6 | 82.3 | 29.4 |

| FY1011 | 66.9 | 90.7 | 42.4 | 82.2 | 30.4 |

| FY1112 | 66.6 | 90.6 | 42.5 | 82.1 | 30.7 |

| FY1213 | 66.6 | 90.9 | 42.7 | 82.6 | 31.4 |

| FY1314 | 66.4 | 90.7 | 43.2 | 82.6 | 31.9 |

| FY1415 | 65.9 | 90.5 | 43.1 | 81.9 | 31.6 |

| FY1516 | 65.9 | 91.0 | 43.7 | 82.1 | 31.8 |

| FY1617 | 65.7 | 90.9 | 43.5 | 82.4 | 32.5 |

| FY1718 | 65.7 | 91.0 | 43.4 | 82.8 | 32.9 |

| FY1819 | 65.5 | 90.9 | 43.3 | 83.5 | 32.8 |

- Note: Shaded areas correspond to recessionary periods in Canada’s economy.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0017-01.

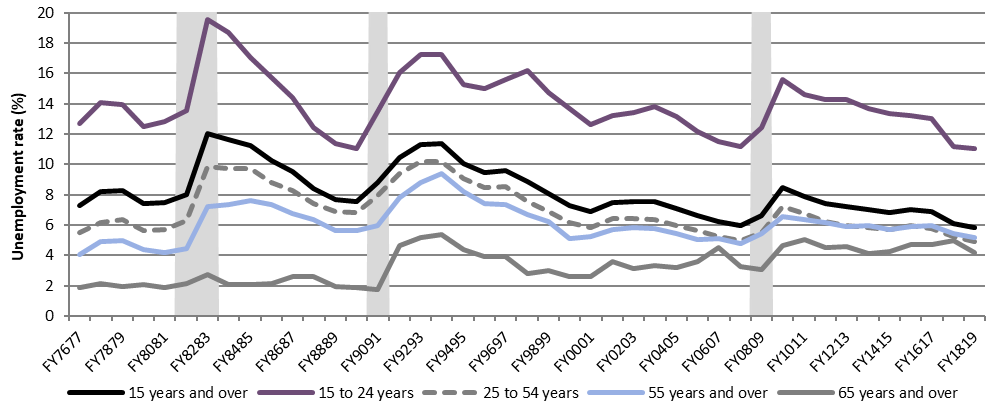

On average, there were 47,000 fewer (-3.9%) unemployed individuals (aged 15 years and over) in Canada in FY1819 compared to the previous fiscal year. This decline in the number of unemployed persons was for the third consecutive year—translating into the lowest level of unemployment rate (5.8%) observed since FY7677 (see Chart 4). Among G7 countries, Canada’s unemployment rate was the third highest in FY1819, behind France and Italy.Footnote 23, Footnote 24 By age groups, the unemployment rate among younger individuals (aged 15 to 24) was the highest (11.0%) in FY1819, while the lowest (4.2%) was among seniors (aged 65 and over)—lower than the unemployment rate among core-aged workers (4.9%) and older workers aged 55 and over (5.2%). As illustrated in Chart 4, the overall unemployment rate, as well as the unemployment rate for the youth (aged 15 to 24) and core-aged workers (aged 25 to 54) reached its lowest mark in 42 years in FY1819. In terms of the eligibility for EI regular benefits, a lower unemployment rate translates into a higher required number of hours of insurable employment within the qualifying period—which is one of the core eligibility requirements (see section 2.2 for details on eligibility for EI regular benefits). Regional variations of the unemployment rate are discussed in detail in subsection 1.2.1.

Chart 4 – Text description

| Fiscal year | 15 years and over | 15 to 24 years | 25 to 54 years | 55 years and over | 65 years and over |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY7677 | 7.3 | 12.7 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 1.9 |

| FY7778 | 8.2 | 14.1 | 6.2 | 4.9 | 2.2 |

| FY7879 | 8.3 | 13.9 | 6.3 | 5.0 | 2.0 |

| FY7980 | 7.4 | 12.5 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 2.1 |

| FY8081 | 7.5 | 12.8 | 5.7 | 4.2 | 1.9 |

| FY8182 | 8.0 | 13.6 | 6.3 | 4.5 | 2.1 |

| FY8283 | 12.0 | 19.5 | 9.8 | 7.2 | 2.7 |

| FY8384 | 11.7 | 18.7 | 9.7 | 7.3 | 2.1 |

| FY8485 | 11.2 | 17.0 | 9.7 | 7.6 | 2.1 |

| FY8586 | 10.3 | 15.7 | 8.8 | 7.4 | 2.2 |

| FY8687 | 9.5 | 14.4 | 8.3 | 6.8 | 2.6 |

| FY8788 | 8.4 | 12.5 | 7.4 | 6.4 | 2.6 |

| FY8889 | 7.7 | 11.4 | 6.9 | 5.7 | 1.9 |

| FY8990 | 7.6 | 11.1 | 6.8 | 5.7 | 1.9 |

| FY9091 | 8.8 | 13.5 | 7.9 | 6.0 | 1.7 |

| FY9192 | 10.4 | 16.0 | 9.4 | 7.8 | 4.7 |

| FY9293 | 11.3 | 17.3 | 10.2 | 8.8 | 5.2 |

| FY9394 | 11.4 | 17.2 | 10.2 | 9.4 | 5.4 |

| FY9495 | 10.0 | 15.3 | 9.1 | 8.2 | 4.4 |

| FY9596 | 9.5 | 15.0 | 8.5 | 7.4 | 4.0 |

| FY9697 | 9.6 | 15.6 | 8.5 | 7.3 | 3.9 |

| FY9798 | 8.9 | 16.2 | 7.6 | 6.7 | 2.8 |

| FY9899 | 8.1 | 14.8 | 6.9 | 6.2 | 3.0 |

| FY9900 | 7.3 | 13.7 | 6.2 | 5.1 | 2.6 |

| FY0001 | 6.9 | 12.6 | 5.8 | 5.2 | 2.6 |

| FY0102 | 7.5 | 13.2 | 6.4 | 5.7 | 3.6 |

| FY0203 | 7.5 | 13.4 | 6.4 | 5.9 | 3.2 |

| FY0304 | 7.6 | 13.8 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 3.3 |

| FY0405 | 7.1 | 13.1 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 3.2 |

| FY0506 | 6.6 | 12.2 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 3.6 |

| FY0607 | 6.3 | 11.5 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 4.5 |

| FY0708 | 6.0 | 11.2 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 3.3 |

| FY0809 | 6.6 | 12.4 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 3.1 |

| FY0910 | 8.5 | 15.6 | 7.2 | 6.6 | 4.7 |

| FY1011 | 7.9 | 14.6 | 6.7 | 6.4 | 5.1 |

| FY1112 | 7.5 | 14.3 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 4.5 |

| FY1213 | 7.2 | 14.3 | 6.0 | 5.9 | 4.6 |

| FY1314 | 7.0 | 13.7 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 4.1 |

| FY1415 | 6.9 | 13.3 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 4.3 |

| FY1516 | 7.0 | 13.2 | 6.0 | 5.9 | 4.7 |

| FY1617 | 6.9 | 13.0 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 4.7 |

| FY1718 | 6.1 | 11.2 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 5.0 |

| FY1819 | 5.8 | 11.0 | 4.9 | 5.2 | 4.2 |

- Note: Shaded areas correspond to recessionary periods in Canada’s economy.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0017-01.

The number of job vacancies (unoccupied positions for which employers are actively seeking workers) increased substantially in FY1819 (+15.7%) compared to the previous fiscal year, reaching 537,800 vacant positions, up from 464,600 vacant positions in FY1718.Footnote 25 Of the total number of vacant positions in the reporting fiscal year, a little less than three-quarters (72.5% or 389,600 positions) were for full-time jobs. Close to two-thirds (62.5%) of the total vacant jobs required high school diploma or less. On that same note, the job vacancy rate (the number of job vacancies expressed as a percentage of all occupied and vacant jobs) rose to 3.3% during the reporting period, up from 2.9% observed in the previous fiscal year (+0.4 percentage points). The highest job vacancy rate in FY1819 was in the Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting industry (6.0%), while the lowest was in the Educational services industry (1.1%). Notably, the job vacancy rate rose in all industries in FY1819 compared to the FY1718, except for the Mining, oil and gas extraction industry and the Finance and insurance industry where the job vacancy rate remained unchanged from the previous fiscal year.Footnote 26 The duration of job vacancies also continued to rise in FY1819, for the second year in a row, which suggests that it took more time for employers to fill their vacant positions in FY1819 compared to the previous fiscal year. The proportion of positions that were vacant for a longer period of time (3 months or more) increased by 0.8 percentage points in FY1819 compared to FY1718, reaching 12.3% of all vacant positions. The growing proportion of vacant positions with longer durations, along with the increased job vacancy rate, points to stronger labour demand that has continued in the reporting period from the past year.

Labour market condition of Indigenous peoples and persons with disability

While this chapter outlines the overall labour market conditions in Canada, it is also important to focus on the specific segments of the population who may be vulnerable. Two such population groups are Indigenous peoplesFootnote 27 and persons with some degree of disability.Footnote 28

Generally, the Indigenous population in Canada have less desirable labour market outcomes than the non-Indigenous population. In the reporting year, the employment rate among the Indigenous population in Canada was 58.1%, compared to 63.0% for the non-Indigenous population. The participation rate among the Indigenous population (64.6%) was also lower than that of the non-Indigenous population (66.6%), suggesting that the available labour resources in the Indigenous population are being utilized at a comparatively lower rate. Consequently, there was a stark difference between the unemployment rates for the Indigenous and non-Indigenous population groups—in FY1819, the unemployment rate among Indigenous individuals was 10.0%, whereas it was 5.3% for the non-Indigenous individuals. In contrast to the generally lower employment and participation rates observed for the Indigenous population compared to the non-Indigenous population, they were higher for the Indigenous population among older individuals (see Table 1).| Category | Indigenous employment rate (%) | Non-Indigenous employment rate (%) | Indigenous participation rate (%) | Non-Indigenous participation rate (%) | Indigenous unemployment rate (%) | Non-Indigenous unemployment rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 60.6% | 67.7% | 68.6% | 71.8% | 11.6% | 5.8% |

| Women | 55.7% | 58.6% | 60.8% | 61.6% | 8.3% | 4.8% |

| 15 to 24 years old | 47.8% | 58.9% | 58.2% | 65.7% | 17.9% | 10.2% |

| 25 to 54 years old | 71.8% | 85.2% | 78.5% | 89.0% | 8.5% | 4.3% |

| 55 years old and over | 36.8% | 35.9% | 40.0% | 37.9% | 8.1% | 5.1% |

| Canada | 58.1% | 63.0% | 64.6% | 66.6% | 10.0% | 5.3% |

- Note: Non-Indigenous population includes individuals who identified themselves as not belonging to any of the following groups: North American Indian, Inuit or Métis; and excludes those who did not respond to this survey question. Estimates presented in this subsection exclude persons living on reserves.

- Source: ESDC calculations using Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey master files, April 2018 to March 2019.

An estimated 1 in 5 Canadians (22% or 6.2 million) aged 15 and over had one or more disabilities in 2017.Footnote 29 Persons with disabilities remain less likely to be employed than those without disabilities,Footnote 30 both in Canada and other parts of the world.Footnote 31 Based on the Canadian Survey on Disability in 2017, almost 3 in 5 (59%) persons with disabilities were employed compared to 4 in 5 (80%) without disabilities among those aged 25 to 64 years. It was also found that the employment rate was even lower for persons with more severe disabilities—ranging from 76% among those with mild disabilities to 31% among those with very severe disabilities.Footnote 32

Employment rates also varied based on demographic factors and the degree of disability—for example, employment rate was higher for men with milder disabilities for all age groups except those who were 25 to 34 years old; however, this reversed among those with more severe disabilities as the employment rate was higher for women for all age groups, except those who were 55 to 64 years old. Individuals with more severe disability were also more likely to work part-time (defined as less than 30 hours per week). Regardless of the level of severity of disability, persons with post-secondary education had higher employment rate compared to those with high school graduation or less—this is consistent with the results found for individuals with no disability.1.2.1 Canada’s regional labour markets

Canada’s continued strong labour market performance in FY1819 was evident in all provinces and territories, as all of them had a positive growth in employment from the previous fiscal year. Employment growth was at or above the national level in Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Alberta, British Columbia and Nunavut. The participation rate, on the other hand, remained relatively unchanged in most provinces and territories, except Yukon and Nunavut, where it decreased slightly in FY1819 compared to the previous fiscal year (-1.6 and -1.1 percentage points, respectively)—see Annex 1.4 and Annex 1.5 for information on employment and participation rates by provinces and territories in the past 5 years. Together, as discussed earlier, an increase in the level of employment, with unchanged or a decline in the participation rate, is indicative of an aging population in the provinces and territories. In terms of the number of job vacancies, as outlined in Table 2, all provinces and territories except Saskatchewan had an increase in FY1819 on a year-over-year basis. The job vacancy rate, however, was higher in all provinces and territories in FY1819 compared to the rate observed in the previous year, indicating a higher demand for labour in each of the provinces and territories.

| Province or territory | Labour force participation rate (%) | Employment (thousands) | Year-over-year change in employment | Job vacancies (thousands) | Year-over-year change in job vacancies (%) | Job vacancy rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 59.0% | 227.3 | +1.7% | 4.0 | +14.7% | 2.0% |

| Prince Edward Island | 66.4% | 76.1 | +2.4% | 2.3 | +36.4% | 3.6% |

| Nova Scotia | 61.8% | 459.0 | +1.9% | 11.0 | +10.8% | 2.7% |

| New Brunswick | 61.4% | 354.8 | +0.5% | 9.3 | +21.4% | 3.0% |

| Quebec | 64.5% | 4,273.0 | +0.7% | 116.7 | +30.9% | 3.2% |

| Ontario | 64.6% | 7,288.8 | +1.9% | 205.9 | +11.0% | 3.2% |

| Manitoba | 67.2% | 650.9 | +0.9% | 15.1 | +7.6% | 2.5% |

| Saskatchewan | 68.7% | 572.2 | +0.9% | 10.0 | -0.5% | 2.2% |

| Alberta | 71.8% | 2,333.0 | +1.5% | 55.8 | +8.2% | 2.8% |

| British Columbia | 65.1% | 2,512.1 | +1.4% | 105.7 | +17.6% | 4.6% |

| Yukon | 74.4% | 21.2 | +0.1% | 0.8 | +13.9% | 4.5% |

| Northwest Territories | 71.2% | 21.4 | +0.5% | 0.7 | +17.6% | 3.3% |

| Nunavut | 62.8% | 13.6 | +2.2% | 0.4 | +16.8% | 3.4% |

| Canada | 65.5% | 18,747.1 | +1.4% | 537.7 | +15.7% | 3.3% |

- Note: Figures for Canada’s participation rate and employment exclude the territories, while figures for job vacancies and job vacancy rate include all provinces and territories. Percentage change is based on unrounded numbers.

- Sources: Statistics Canada; Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0287-01 and 14-10-0292-01 (for data on participation rates and employment) and Job Vacancy and Wage Survey, Table 14-10-0325-01(for data on job vacancies).

Table 3 outlines the unemployment rate and duration of unemployment in the provinces and territories in the reporting fiscal year and the previous fiscal year. The unemployment rate decreased notably in all provinces and territories except Manitoba and Northwest Territories, led by Newfoundland and Labrador (-1.7 percentage points) and Nova Scotia (-1.1 percentage points). Among the provinces, British Columbia continued to record the lowest unemployment rate (4.7%) for the third consecutive year in FY1819, while Quebec and Ontario had unemployment rates below the national average for the second consecutive year. The Atlantic provinces continued to post unemployment rates well above the national average, led by Newfoundland and Labrador (13.0%). Among the territories, Yukon had the lowest unemployment rate (3.2%), lower than the national average and significantly lower than Northwest Territories (7.3%) and Nunavut (14.2%).Footnote 33

In FY1819, the average duration of an unemployment spell in Canada was 18.1 weeks, down from 19.1 weeks observed in FY1718 (-1.0 week). The variation in the unemployment duration was mixed among the provinces, suggesting contrasting labour market developments in the reporting period. Among the provinces, the highest unemployment duration was in Alberta (21.9 weeks), despite a decline of 0.8 weeks from the record level observed in that province in the previous fiscal year. On the other hand, the lowest level of unemployment duration was observed in Prince Edward Island (14.2 weeks).

| Province or territory | Unemployment rate FY1718 | Unemployment rate FY1819 | Unemployment rate Change (% points) | Unemployment spells duration (weeks) FY1718 | Unemployment spells duration (weeks) FY1819 | Unemployment spells duration (weeks) Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 14.7% | 13.0% | -1.7 | 18.7 | 19.8 | +1.1 |

| Prince Edward Island | 9.9% | 9.3% | -0.6 | 16.1 | 14.2 | -2.0 |

| Nova Scotia | 8.3% | 7.2% | -1.1 | 17.7 | 18.0 | +0.3 |

| New Brunswick | 8.0% | 7.9% | -0.1 | 18.4 | 16.2 | -2.3 |

| Quebec | 5.9% | 5.4% | -0.4 | 18.6 | 18.6 | 0.0 |

| Ontario | 5.8% | 5.7% | -0.1 | 18.6 | 17.1 | -1.5 |

| Manitoba | 5.5% | 5.8% | +0.3 | 15.9 | 16.6 | +0.7 |

| Saskatchewan | 6.1% | 6.0% | -0.1 | 18.7 | 21.2 | +2.5 |

| Alberta | 7.4% | 6.7% | -0.7 | 22.7 | 21.9 | -0.8 |

| British Columbia | 5.0% | 4.7% | -0.3 | 18.3 | 15.4 | -2.8 |

| Yukon | 3.4% | 3.2% | -0.2 | not available | not available | not available |

| Northwest Territories | 6.9% | 7.3% | +0.3 | not available | not available | not available |

| Nunavut | 14.5% | 14.2% | -0.3 | not available | not available | not available |

| Canada | 6.1% | 5.8% | -0.3 | 19.1 | 18.1 | -1.0 |

- Note: The unemployment rates and the average unemployment spell durations shown for Canada exclude the territories.

- Sources: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0287-01, 14-10-0292-01 and 14-10-0056-01.

Unemployment rate and the probability of finding a job

A recent departmental study* examined factors influencing the ability of unemployed individuals to find a job. Using Labour Force Survey data from 2006 to 2018, the study found that the probability of finding a job increases with educational attainment, but decreases as the unemployment spell lengthens. It also varies significantly across occupations. In addition, after accounting for occupation and EI economic region, neither gender nor age seemed to affect the probability of finding a job.

The study also found that the probability of finding a job varies across EI economic regions with similar unemployment rates, suggesting that the unemployment rates do not fully reflect the probability of finding a job. The same result still holds when involuntary part-time workers and discouraged job searchers are included in the analysis.

- *ESDC, Factors that influence the probability of finding jobs in EI regions. (Ottawa: ESDC, Labour Market Information Directorate, 2020).

Trends in temporary layoffs and recall expectations

A recent departmental study* examined the trends in temporary layoffs in Canada, as well as the trends and the characteristics of workers experiencing temporary layoffs with recall expectations from their employers, using different data sources.

Based on the Labour Force Survey (LFS), the total layoff rates** (permanent and temporary layoffs combined) in Canada have declined from around 4.0% in 1976 to 2.5% in 2018. Considering the 3 recessionary periods over that time, the average temporary layoff rates increased during those periods but to a lesser extent in recent recessions, going from 0.8% in 1980 to 1984, 0.7% in 1990 to 1994, to 0.5% in 2008 to 2011. During the period examined, women had lower average rates of temporary layoffs than men.

The study found that there was also a decline in the expected recall rate*** over time, going from 32% in 1996 to 25% in 2018, as measured by the LFS data. However, over the same period, the actual recall rate, estimated with Record of Employment and Tax data, increased. In 2016, about 60% of laid-off employees were recalled by their former employer, compared to 47% in 1999.

In terms of characteristics of laid-off employees with recall expectations, men, workers with less than a bachelor degree and workers from the Atlantic provinces were over-represented compared to their relative share of employment in Canada.

- *ESDC, Trends in Temporary Layoffs and Recall Expectations. (Ottawa: ESDC, Labour Market Information Directorate, 2020).

- ** Layoff rates are the numbers of layoffs expressed as a proportion of employment.

- *** Expected recall rates are the numbers of laid-off employees expecting to be recalled by their former employer expressed as a proportion of all laid-off employees.

The average weekly nominal and realFootnote 34 earnings in FY1819 and the previous fiscal year in the provinces and territories are outlined in Table 4. In the reporting fiscal year, the territories continued to have the highest average nominal weekly earnings, followed by Alberta ($1,147) and Newfoundland and Labrador ($1,041). The lowest average nominal weekly earnings, on the other hand, was in Prince Edward Island ($843)—well below the national average of $1,005.Footnote 35 All provinces and territories experienced an increase in the average nominal weekly earnings in FY1819 compared to the previous fiscal year; however, in real terms, the average weekly earnings actually declined in 5 provinces and in the Northwest Territories (see Table 4). The national average weekly earnings in real terms remained virtually unchanged (+0.1%) in FY1819 compared to the previous fiscal year.

| Province or territory | Average nominal weekly earnings ($)* FY1718 | Average nominal weekly earnings ($)* FY1819 | Average nominal weekly earnings ($)* change (%) FY1718 to FY1819 | Average real weekly earnings ($)** FY1718 | Average real weekly earnings ($)** FY1819 | Average real weekly earnings ($)** change (%) FY1718 to FY1819 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1,034 | 1,041 | +0.7% | 759 | 754 | -0.7% |

| Prince Edward Island | 828 | 843 | +1.9% | 618 | 618 | 0.0% |

| Nova Scotia | 863 | 878 | +1.8% | 648 | 647 | -0.2% |

| New Brunswick | 893 | 916 | +2.6% | 677 | 682 | +0.7% |

| Quebec | 912 | 938 | +2.8% | 716 | 724 | +1.2% |

| Ontario | 1,000 | 1,026 | +2.6% | 754 | 757 | +0.4% |

| Manitoba | 917 | 944 | +3.0% | 698 | 702 | +0.5% |

| Saskatchewan | 1,011 | 1,017 | +0.6% | 747 | 738 | -1.3% |

| Alberta | 1,139 | 1,147 | +0.8% | 826 | 812 | -1.6% |

| British Columbia | 950 | 973 | +2.4% | 755 | 753 | -0.3% |

| Yukon | 1,091 | 1,135 | +4.0% | 852 | 866 | +1.6% |

| Northwest Territories | 1,401 | 1,423 | +1.6% | 1,045 | 1,038 | -0.7% |

| Nunavut | 1,343 | 1,385 | +3.2% | 1,064 | 1,067 | +0.3% |

| Canada | 983 | 1,005 | +2.2% | 750 | 751 | +0.1% |

- * Earnings include overtime and apply to employees paid by the hour, salaried employees and other employees.

- ** Based on 2002 dollars.

- Sources: Statistics Canada, Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours, Table 14-10-0203-01 (for data on nominal earnings), and Statistics Canada, Consumer Price Index Measures, Table 18-10-0004-01 (for data on CPI).

As discussed above, FY1819 marked the lowest unemployment rate (5.8%) since FY7677, indicating a relatively lower number of individuals looking for work in excess of those who were already employed during the reporting period. On the other hand, the increased number of job vacancies in FY1819 suggests that the unmet labour demand has continued rising during the reporting period. One very important aspect of an efficient labour market is how easily and efficiently workers find jobs and employers find skilled labour for available positions. The unemployment-to-job vacancy (UV) ratio shows the number of unemployed people for every vacant position—a measure of how tight or slack the labour market is. A low UV ratio corresponds to a lower number of unemployed people relative to the total job vacancies, which may indicate that unemployed workers are able to find jobs more efficiently and there is lower skills mismatch.Footnote 36 A lower UV ratio indicates a more tight labour market. Table 5 outlines the UV ratios by province from FY1516 to FY1819. The UV ratio declined in all provinces in FY1819 for the second consecutive year, except Manitoba and Saskatchewan where it remained unchanged, indicating increased tightness in the Canadian labour market. During the reporting period among provinces, the UV ratio ranged from 0.9 in Yukon to 8.6 in Newfoundland and Labrador. A larger UV ratio can occur when there is a larger share of unemployed person relative to their share of job openings. For example, in FY1819 Newfoundland and Labrador accounted for 2.9% of the total unemployed population but had only 0.7% share of the total job vacancies. Similarly, in FY1819 Nova Scotia had 3.1% share of the total unemployed population while accounted for only 2.0% of the total number of job vacancies, which reflect the slack labor market conditions in these provinces.

| Province | FY1516 | FY1617 | FY1718 | FY1819 | Change FY1718 to FY1819 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 7.8 | 10.3 | 11.1 | 8.6 | -2.5 |

| Prince Edward Island | 5.9 | 6.6 | 4.8 | 3.4 | -1.5 |

| Nova Scotia | 4.3 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 3.2 | -0.9 |

| New Brunswick | 5.2 | 5.6 | 4.0 | 3.3 | -0.7 |

| Quebec | 5.7 | 4.6 | 3.0 | 2.1 | -0.8 |

| Ontario | 3.2 | 2.9 | 2.4 | 2.1 | -0.2 |

| Manitoba | 3.1 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 0.0 |

| Saskatchewan | 2.8 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 0.0 |

| Alberta | 2.9 | 4.8 | 3.5 | 3.0 | -0.6 |

| British Columbia | 2.4 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.2 | -0.3 |

| Canada | 3.5 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 2.2 | -0.4 |

- Note: The UV ratios presented in this table are calculated using the number of job vacancies from the Job Vacancy and Wage Survey, and the number of unemployed from the Labour Force Survey, to be consistent with the data provided elsewhere in this chapter. Statistics Canada provides UV ratios using job vacancy statistics from the Survey of Employment, Payroll and Hours in Table 14-10-0226-01, which are different from the estimates presented here, due to sampling and coverage issues.

- Sources: Statistics Canada, Job Vacancy and Wage Survey, Table 14-10-0325-01 (for data on job vacancies), and Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0017-01 (for data on unemployment).

1.2.2 Interprovincial mobility trends

A substantial number of people in Canada relocate across provincial and territorial borders each year. Between July 1, 2018 and June 30, 2019, an estimated 290,500 individuals relocated within Canada. This movement across provinces and territories is partly attributable to emerging employment opportunities or a decline in labour demand, and gives workers the possibility to access labour markets in other jurisdictions and obtain or find a job that may be better suited for their particular skillset. From a national perspective, interprovincial mobility can increase real GDP and aggregate labour productivity growth. It can also improve individual outcomes in terms of finding suitable employment, as workers from provinces with high unemployment and an excess of labor supply move to provinces with lower unemployment and labour shortages.

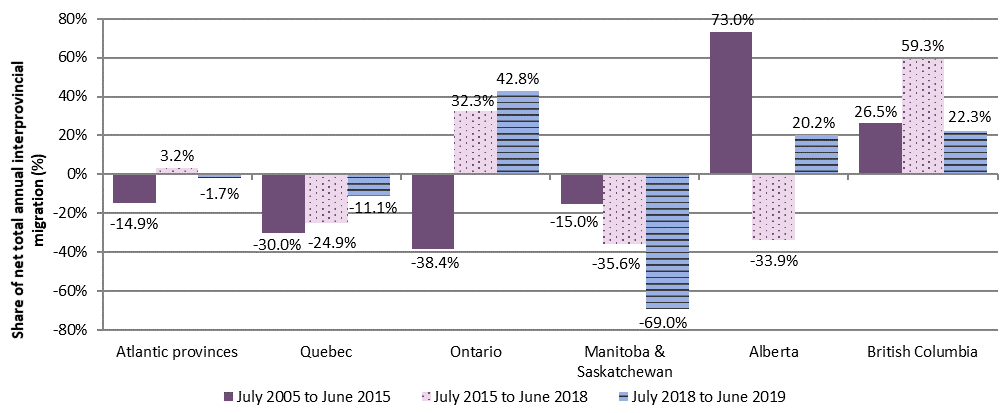

While several factors can influence an individual’s decision to move (including, but not limited to, job opportunities, education/school or family reasons), the desire to seek a higher standard of living is often a driving force. Since the mid-1990s, Western Canada, especially Alberta, was the destination of choice for a majority of Canadian interprovincial migrants. However, with the downturn in commodity prices and less favourable labour market conditions in Alberta, trends have somewhat shifted to Ontario and British Columbia in recent years (see Chart 5).

Labour market developments in Ontario and British Columbia have made these provinces the preferred destination of interprovincial migrants since July 2015 (+11,000 and +16,400 on average per year, respectively). In Alberta, the net migration was on average 23,700 each year from July 2005 to June 2015—a trend that reversed from July 2015 to June 2018 (-11,300 in net migration per year, on average), following the downturn in commodity prices in FY1415. However, between July 2018 and June 2019 Alberta experienced positive net migration (+5,500). Saskatchewan, another oil-producing province, had an average net migration of -7,000 per year over the period July 2015 to June 2019.

Chart 5 – Text description

| Region | July 2005 to June 2015 (annual average) | July 2015 to June 2018 (annual average) | July 2018 to June 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic provinces | -14.9% | 3.2% | -1.7% |

| Quebec | -30.0% | -24.9% | -11.1% |

| Ontario | -38.4% | 32.3% | 42.8% |

| Manitoba and Saskatchewan | -15.0% | -35.6% | -69.0% |

| Alberta | 73.0% | -33.9% | 20.2% |

| British Columbia | 26.5% | 59.3% | 22.3% |

- Note: Annual is defined as the period from July 1 to June 30. Results for the territories are not presented in the chart. Consequently, the total net migration does not add up to zero.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Table 17-10-0021-01.

1.3 Trends in non-standard employment in Canada

In this section

- 1.3.1 Profile of permanent part-time employees

- 1.3.2 Profile of the self-employed

- 1.3.3 Profile of individuals in temporary employment

Labour market developments as discussed in the previous section, such as employment growth, do not distinguish between standard and non-standard jobs. Different types of employment result in varying labour market outcomes, such as hours worked and wage level, which are linked to qualifying for and the amount received in EI benefits. The prevalence of standard employment that emerged in the post-World War II period, which generally refers to the employee “working full-time, year-round for one single employer on the employer’s premises, enjoys extensive statutory benefits and entitlements, and expects to be employed indefinitely,”Footnote 37 started to decrease due to more non-standard employment pattern in the 1980s.Footnote 38 Non-standard employment currently makes up a sizeable share of the labour force—36.9% in FY1819, and it has remained fairly stable since the latter half of the 1990s. The evolution of non-standard employment in Canada, types of such employment, as well as the characteristics of individuals who are engaged in such employment patterns are reported in this section.

Non-standard employment is an umbrella term that comprises the following 3 situations:

- permanent part-time employment

- self-employment (including unpaid family workers), and

- temporary employment

Each accounts for 10.5%, 15.3% and 11.2% of total employment in Canada in FY1819 (see Chart 6).

Chart 6 – Text description

| Mutually exclusive employment forms | Number | Share |

|---|---|---|

| Total employment | 18,747,100 | 100.0% |

| Paid employees | 15,886,300 | 84.7% |

| Permanent paid employees | 13,791,800 | 73.6% |

| Full-time permanent paid employees | 11,822,400 | 63.1% |

| Part-time permanent paid employees | 1,969,400 | 10.5% |

| Temporary paid employees | 2,094,500 | 11.2% |

| Self-employed | 2,860,800 | 15.3% |

| Own-account self-employed | 1,985,900 | 10.6% |

| Self-employed employers | 853,400 | 4.6% |

| Unpaid family workers | 21,500 | 0.1% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Public Use Microdata File, April 2018 to March 2019.

Precariousness can be a feature of non-standard jobs, but it is not essential to the definition of non-standard employment. The degree of precariousness of an employment form is dependent on multiple dimensions; for example, the uncertainty of continuing employment, the control over the labour process (including working conditions, wages and existence of labour unions), and the degree of regulatory protection and the income level.Footnote 39 Some full-time full-year jobs can also be precarious in a sense (for example, being in a position with no opportunities for job advancement due to various reasons or for reskilling), and the level of precariousness varies by types of non-standard employment.

There are important differences among the range of non-standard employment situations; for example, the occupation, income profile and job security of workers in temporary employment may be different from that of individuals who are self-employed. Similarly, within the self-employed category, there can be differences between individuals who employ others and those who do not. Also, many workers in non-standard employment could be excluded from collective bargaining law and employment standards legislation.Footnote 40

The rest of this section outlines the evolution of non-standard employment by type (that is, permanent part-time employment, self-employment and temporary employment) in Canada and the characteristics of individuals working in such types of work arrangement.

Employment instability in Canada’s labour market

Not considered as part of non-standard employment, multiple (or “concurrent”) job holders are sometimes considered as a group of workers that have precarious or unstable work. A recent study* by ESDC examined several trends in employment instability, including whether employees concurrently worked for more than 1 employer within a given year, as well as the average job tenure and earnings instability.

Using data from the Labour Force Survey (LFS) and Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) tax files, the study found mixed evidence on the trend of employment instability (mainly measured by the number of employees holding multiple concurrent jobs) in Canada over time. From the LFS, by identifying individuals who held multiple jobs in any month of the year that they were surveyed, the study found the multiple jobholding rate to be trending upwards, from 9.1% in 2000 to almost 12% in 2018. The rate increased steadily for all age groups during this period, with a more pronounced increase for older workers aged between 45 and 64 years. Women were more likely to hold multiple jobs than men, and this gender gap was found to be more evident among older workers. As well, the study found increases in the multiple jobholding rate in a majority of industries, although there were substantial variations across industries. Notably, multiple job holding increased for some industries dominated by low skilled/low wage jobs as well as for those dominated by high skilled/high wage jobs.

By contrast, from the CRA data, both for all employees and EI recipients, the study found that the multiple jobholding rate has declined over time, although the numbers are markedly lower for EI recipients. Between 1999 and 2015, the rate for all employees declined from 18.0% to 12.0% and for EI recipients, it decreased from about 7% to 4%.

The study also looked at other measures of employment instability, namely the average job tenure and earnings instability. The average job tenure was found to have declined for workers in Canada between 1990 and 2018. This decline was the most pronounced for workers aged between 35 and 54 years. Furthermore, the percentage of employees with earnings instability, indicated by a drop in the real annual income by 2% or more, was found to have increased over time, from 30% in 2000 to 39% in 2015, indicative of greater employment instability from an annual income perspective.

- *ESDC, Employment Insurance and the changing stability of employment relationships. (Ottawa: ESDC, Labour Market Information Directorate, 2020).

1.3.1 Profile of permanent part-time employees

Over time, the prevalence of part-time employment (both permanent and temporary), which consists of work usually less than 30 hours per week at the main or only job, grew consistently until the end of 1980’s, and remained stable since then (see Chart 7).

Chart 7 – Text description

| Fiscal year | Number of part-time employment (left-scale) | Share of total employment (right scale) |

|---|---|---|

| FY7677 | 1,235.1 | 12.6% |

| FY7778 | 1,305.2 | 13.1% |

| FY7879 | 1,371.9 | 13.3% |

| FY7980 | 1,502.7 | 14.0% |

| FY8081 | 1,595.9 | 14.4% |

| FY8182 | 1,690.5 | 15.0% |

| FY8283 | 1,767.2 | 16.3% |

| FY8384 | 1,866.1 | 16.8% |

| FY8485 | 1,914.5 | 16.8% |

| FY8586 | 2,001.3 | 17.0% |

| FY8687 | 2,038.0 | 16.9% |

| FY8788 | 2,076.0 | 16.7% |

| FY8889 | 2,155.7 | 16.9% |

| FY8990 | 2,167.6 | 16.6% |

| FY9091 | 2,239.6 | 17.2% |

| FY9192 | 2,342.6 | 18.3% |

| FY9293 | 2,369.2 | 18.6% |

| FY9394 | 2,478.1 | 19.3% |

| FY9495 | 2,466.3 | 18.7% |

| FY9596 | 2,522.1 | 18.9% |

| FY9697 | 2,572.8 | 19.1% |

| FY9798 | 2,606.7 | 18.9% |

| FY9899 | 2,655.5 | 18.8% |

| FY9900 | 2,644.5 | 18.2% |

| FY0001 | 2,684.0 | 18.1% |

| FY0102 | 2,730.5 | 18.2% |

| FY0203 | 2,910.8 | 18.9% |

| FY0304 | 2,961.5 | 18.8% |

| FY0405 | 2,958.9 | 18.5% |

| FY0506 | 2,974.1 | 18.4% |

| FY0607 | 3,000.7 | 18.2% |

| FY0708 | 3,080.0 | 18.3% |

| FY0809 | 3,178.2 | 18.7% |

| FY0910 | 3,228.8 | 19.3% |

| FY1011 | 3,346.6 | 19.6% |

| FY1112 | 3,305.4 | 19.2% |

| FY1213 | 3,319.8 | 18.9% |

| FY1314 | 3,391.4 | 19.1% |

| FY1415 | 3,431.7 | 19.2% |

| FY1516 | 3,389.5 | 18.9% |

| FY1617 | 3,492.7 | 19.2% |

| FY1718 | 3,506.7 | 19.0% |

| FY1819 | 3,516.4 | 18.8% |

- Note: Shaded areas correspond to recessionary periods in Canada’s economy.

- * This chart is based on both permanent and temporary part-time employment, and not only permanent part-time employment.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour force Survey, Table 14-10-0050-01.

This following subsection only focuses on permanent part-time employment; temporary part-time employment is included in subsection 1.3.3 as part of temporary employment.

Permanent part-time employment does not have a specified end-date. In the past decade, the share of individuals with permanent part-time employment among the total employed has gone down slightly. Notably, women are over-represented in this type of employment, representing 69.3% of these workers in FY1819. Within the last decade, however, the share of men among workers with permanent part-time employment has been increasing, from 28.1% in FY0809 to 30.7% in FY1819 (see Table 6).

| Category | Number (thousands) and share (%) of permanent part-time employment FY0809 | Share of total employment (%) FY0809 | Number (thousands) and share (%) of permanent part-time employment FY1819 | Share of total employment (%) FY1819 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 531.8 (28.1%) | 6.0% | 603.8 (30.7%) | 6.2% |

| Women | 1,358.9 (71.9%) | 16.9% | 1,365.5 (69.3%) | 15.3% |

| 15 to 24 years | 767.9 (40.6%) | 29.6% | 727.8 (37.0%) | 29.6% |

| 25 to 54 years | 827.5 (43.8%) | 7.1% | 824.6 (41.9%) | 6.7% |

| 55 years and over | 295.3 (15.6%) | 11.1% | 417.0 (21.2%) | 10.3% |

| Canada | 1,890.7 (100.0%) | 11.2% | 1,969.4 (100.0%) | 10.5% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Public Use Microdata File, April 2008 to March 2019.

By age groups, a higher share of youth (29.6%) work in permanent part-time employment, compared to individuals in other age groups (6.7% of core-aged workers and 10.3% of older workers) in FY1819. This is attributable to the fact that a large share of youth are students who chooses part-time employment to better reconcile study with work. However, over the last decade, older workers accounted for a growing part of part-time employees, from 15.6% in FY0809 to 21.2% in FY1819.

It should be noted that some workers choose part-time employment over full-time employment due to the flexibility it offers. A recent study by Statistics CanadaFootnote 41 found that nearly three-quarters (73%) of youth working part-time chose to do so because of schooling, while among older workers the main reason was personal preferences. Childcare was an important factor for core-aged women, which also explains the relatively higher share of women in part-time employment. Based on the Labour Force Survey in FY1819, 21.1% of part-time employees worked involuntarily in such employment arrangement.Footnote 42

While 79.0% of all Canadian employees worked in the service-producing sector in FY1819,Footnote 43 permanent part-time workers are overrepresented in this sector, representing 95.1% of total part-time workers in FY1819. Notable industries include the Wholesale and retail trade industry (28.2% of total part-time workers), Accommodation and food services industry (18.1% of total part-time workers) and Health care and social assistance industry (17.6% of total part-time workers). This trend has not changed much in the past 10 years (see Annex 1.6).

Permanent part-time workers tend to experience more employment interruptions, thus are less likely to pay EI premiums in the year prior to unemployment. As a result, the proportion of these workers covered by the EI program is lower than that for permanent full-time workers. On the other hand, working fewer hours per week means that the part-time workers would be less likely to accumulate sufficient hours to qualify for EI benefits. In addition, these workers, on average, could also have a lower wage rate compared to full-time workers, which may lead to a lower EI weekly benefit rate.Footnote 44

1.3.2 Profile of the self-employed

Self-employment refers to working owners of a business, farm or professional practice, whether employer (that is, incorporated) or own-account (that is, unincorporated). It also includes unpaid family workers who work without pay on a farm or in a business or professional practice owned and operated by another family member living in the same dwelling (see Chart 6 for breakdown of self-employed categories).

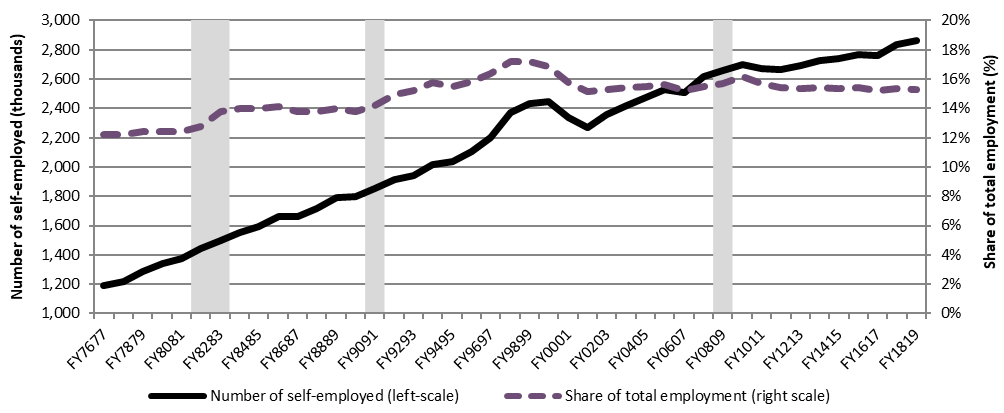

Among all forms of non-standard employment in Canada, self-employment has the largest share of the employed individuals (15.3% in FY1819). Over the years, the share of self-employed among total employed has increased from 12.2% in FY7677 to 17.2% in FY9798 and FY9899, to reach 15.3% in FY1819 (see Chart 8).

Chart 8 – Text description

| Fiscal year | Number of self-employed (left-scale) | Share of total employment (right scale) |

|---|---|---|

| FY7677 | 1,193.4 | 12.2% |

| FY7778 | 1,216.6 | 12.2% |

| FY7879 | 1,283.8 | 12.4% |

| FY7980 | 1,338.6 | 12.4% |

| FY8081 | 1,374.6 | 12.4% |

| FY8182 | 1,441.3 | 12.8% |

| FY8283 | 1,498.1 | 13.8% |

| FY8384 | 1,555.4 | 14.0% |

| FY8485 | 1,595.0 | 14.0% |

| FY8586 | 1,664.0 | 14.1% |

| FY8687 | 1,660.1 | 13.8% |

| FY8788 | 1,718.5 | 13.8% |

| FY8889 | 1,789.2 | 14.0% |

| FY8990 | 1,796.1 | 13.8% |

| FY9091 | 1,849.8 | 14.2% |

| FY9192 | 1,913.7 | 14.9% |

| FY9293 | 1,939.5 | 15.2% |

| FY9394 | 2,019.4 | 15.7% |

| FY9495 | 2,038.8 | 15.5% |

| FY9596 | 2,106.9 | 15.8% |

| FY9697 | 2,203.3 | 16.4% |

| FY9798 | 2,371.8 | 17.2% |

| FY9899 | 2,430.3 | 17.2% |

| FY9900 | 2,448.3 | 16.9% |

| FY0001 | 2,336.6 | 15.8% |

| FY0102 | 2,270.2 | 15.2% |

| FY0203 | 2,356.6 | 15.3% |

| FY0304 | 2,420.6 | 15.4% |

| FY0405 | 2,471.7 | 15.5% |

| FY0506 | 2,528.0 | 15.6% |

| FY0607 | 2,511.0 | 15.2% |

| FY0708 | 2,613.8 | 15.5% |

| FY0809 | 2,660.7 | 15.7% |

| FY0910 | 2,701.9 | 16.1% |

| FY1011 | 2,670.0 | 15.7% |

| FY1112 | 2,663.4 | 15.4% |

| FY1213 | 2,691.1 | 15.4% |

| FY1314 | 2,727.7 | 15.4% |

| FY1415 | 2,738.0 | 15.4% |

| FY1516 | 2,768.8 | 15.4% |

| FY1617 | 2,760.3 | 15.2% |

| FY1718 | 2,834.6 | 15.3% |

| FY1819 | 2,860.8 | 15.3% |

- Note: Shaded areas correspond to recessionary periods in Canada’s economy.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0026-01.

Although we have seen increases in the share of self-employed workers during economic downturns, there is no evidence that economic necessity is a determinant factor for people in choosing this type of work arrangement.Footnote 45 As is the case with part-time employment, many Canadians choose to be self-employed due to the flexibility it provides. Based on the Labour Force Survey of September 2018, around one-third of the respondents (33.5%) who were self-employed in their main job during the 12 months prior to the survey responded independence and freedom to be the main reasons for choosing self-employment. Around 15% of the respondents reported that they were self-employed because of the nature of their job (such as physicians, dentists and veterinarians), while only 5% respondents were self-employed as they could not find suitable employment.Footnote 46 The survey also showed that older workers (aged 55 and over) were more likely to be self-employed than younger (aged between 15 and 24 years) and core-aged (aged between 25 and 54) workers (26%, 3% and 14%, respectively).

In FY1819, almost two-thirds (62.4%) of the self-employed were men. However, within the past decade, growth in the number of self-employed women (+1.6% on average every year) outpaced the growth in the number of self-employed men (+0.3% on average every year); consequently, the share of women in total self-employed population has steadily increased (see Annex 1.7).

By industry classification, there were more self-employed workers in the goods-producing sector (16.7% of total employed in those industries) than in the service-producing sector (14.9% of total employed in those industries) in FY1819—see Table 7 for the incidence of self-employment by industry. The share of self-employed individuals in the goods-producing sector has been declining steadily for the past decade, mostly due to their decrease in the Agriculture industry, while it remained stable in the service-producing sector. The industries with the highest share of self-employed in FY1819 were Agriculture (55.6%), Professional, scientific and technical services (31.7%) and Construction (27.1%) industry.

| Industry | FY0809 | FY1819 |

|---|---|---|

| Goods-producing industries | 18.6% | 16.7% |

| Agriculture | 62.7% | 55.6% |

| Forestry, fishing, mining, quarrying, oil and gas | 14.1% | 11.3% |

| Utilities | n/a* | n/a* |

| Construction | 30.6% | 27.1% |

| Manufacturing | 5.4% | 4.3% |

| Service-producing industries | 14.8% | 14.9% |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 11.2% | 9.1% |

| Transportation and warehousing | 16.8% | 18.5% |

| Finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing | 16.8% | 18.6% |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 34.0% | 31.7% |

| Business, building and other support services | 24.5% | 25.7% |

| Educational services | 4.7% | 6.2% |

| Health care and social assistance | 12.5% | 13.1% |

| Information, culture and recreation | 16.9% | 17.2% |

| Accommodation and food services | 8.2% | 8.3% |

| Other services (except public administration) | 30.2% | 28.8% |

| Public administration | n/a* | n/a* |

| Canada | 15.7% | 15.3% |

- * Data not available.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0026-01.

Self-employed workers are not eligible for EI regular benefits, but they can opt in to EI special benefits (see subsection 2.6.7 for detailed discussion).

Informal (“gig”) work in Canada

The term “gig work” (also known as informal work) has been gaining popularity in recent years to describe the evolution of non-standard work. Gig work tends to involve jobs with relatively short durations, variable hours and earnings, with the absence of employment continuity with a single employer but rather with contracts for a specific period of time or task for which a negotiated amount of money is paid. In that sense, gig workers could fall under the “self-employed” category. In recent years, the prevalence of gig work has been associated with the availability of online platforms and crowdsourcing marketplaces; however, not all gig workers make use of these platforms.

In the Canadian context, research and data on gig economy continue to grow. Consequently, difference in definitions and data sources used to identify gig workers could lead to varied estimates and outcomes. Two Canadian studies on this topic has been undertaken recently.

A recent study by Statistics Canada* identified gig workers using administrative data. It defined gig workers as unincorporated self-employed workers (sole proprietors) aged 15 and over; who reported business, professional or commission self-employment income; and whose future business activity was uncertain or expected to be minor or occasional. The study estimated that during the period 2005 to 2016, the share of gig workers out of all workers rose from 5.5% to 8.2%.

The Statistics Canada study also found that there was a higher share of female gig workers (9.1%) than males (7.2%), and a lower share of youth aged 24 and less than the other age groups, which is contrary to the notion that younger workers are overrepresented in gig work. In addition, gig work was found to be more prevalent among immigrants. The study also estimated that income from gig work was low; that for roughly half of the gig workers, this type of work was only a temporary activity; and that an increasing share of workers do gig work in addition to their main job.

Another paper by Bank of Canada** looked at informal (gig) work by using a broader definition*** than the Statistics Canada study. The study measured the size and characteristics of informal work in Canada using the Canadian Survey of Consumer Expectations, and found that around 30% of the respondents participated in such type of work during the period from April 2018 to December 2018.

- * Sung-Hee Jeon, Huju Liu and Yuri Ostrovsky, “Measuring the gig economy in Canada using administrative data”, Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2019.

- ** Olena Kostyshyna and Corinne Luu, “The size and characteristics of informal (“gig”) work in Canada”, Ottawa: Bank of Canada, Staff Analytical Note, 2019.

- *** The Bank of Canada paper defines informal (gig) work as having engaged in certain side jobs or informal activities for pay over the past 2 years, excluding activities for which income is generated from physical capital (for example, selling goods or renting properties) rather than labour and survey-taking.

1.3.3 Profile of individuals in temporary employment

A temporary job has a predetermined termination date, or ends upon the completion of a project or the attainment of a goal. While there is a degree of uncertainty associated with temporary employment, such work arrangement can also provide employees with flexibility, experience, and enable them to acquire new skills and diversify existing knowledge.

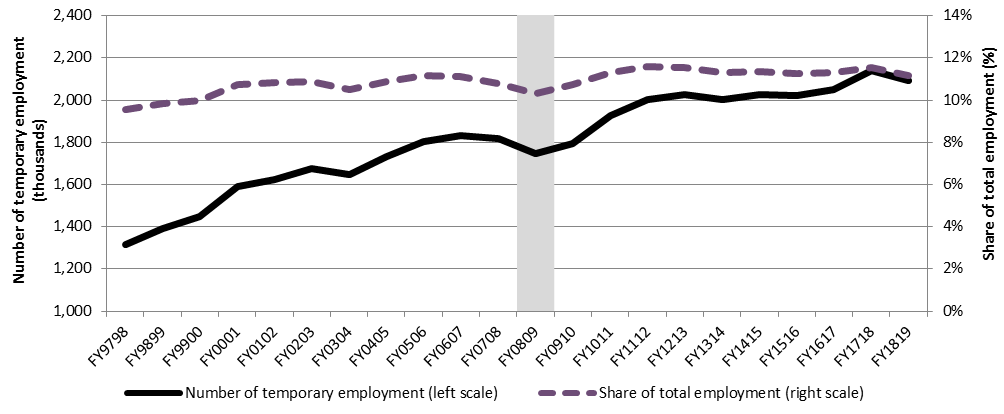

Over the past 20 years, the share of individuals with temporary employment among all workers increased, from 9.5% in FY9798 to 11.2% in FY1819 (see Chart 9). Notably, the number and share of temporary employed individuals went down significantly during the recession in FY0809, as the demand for temporary staff generally goes down during economic downturns.Footnote 47

Chart 9 – Text description

| Fiscal year | Number of temporary employment (left scale) | Share of total employment (right scale) |

|---|---|---|

| FY9798 | 1,316.4 | 9.5% |

| FY9899 | 1,389.7 | 9.8% |

| FY9900 | 1,447.4 | 10.0% |

| FY0001 | 1,588.6 | 10.7% |

| FY0102 | 1,622.0 | 10.8% |

| FY0203 | 1,675.8 | 10.9% |

| FY0304 | 1,649.4 | 10.5% |

| FY0405 | 1,734.4 | 10.9% |

| FY0506 | 1,805.3 | 11.2% |

| FY0607 | 1,829.9 | 11.1% |

| FY0708 | 1,819.3 | 10.8% |

| FY0809 | 1,746.9 | 10.3% |

| FY0910 | 1,796.3 | 10.7% |

| FY1011 | 1,925.6 | 11.3% |

| FY1112 | 2,002.4 | 11.6% |

| FY1213 | 2,025.7 | 11.6% |

| FY1314 | 2,001.2 | 11.3% |

| FY1415 | 2,024.4 | 11.4% |

| FY1516 | 2,022.5 | 11.2% |

| FY1617 | 2,050.9 | 11.3% |

| FY1718 | 2,137.6 | 11.6% |

| FY1819 | 2,094.5 | 11.2% |

- Note: The shaded area corresponds to a recessionary period in Canada’s economy.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0071-01.

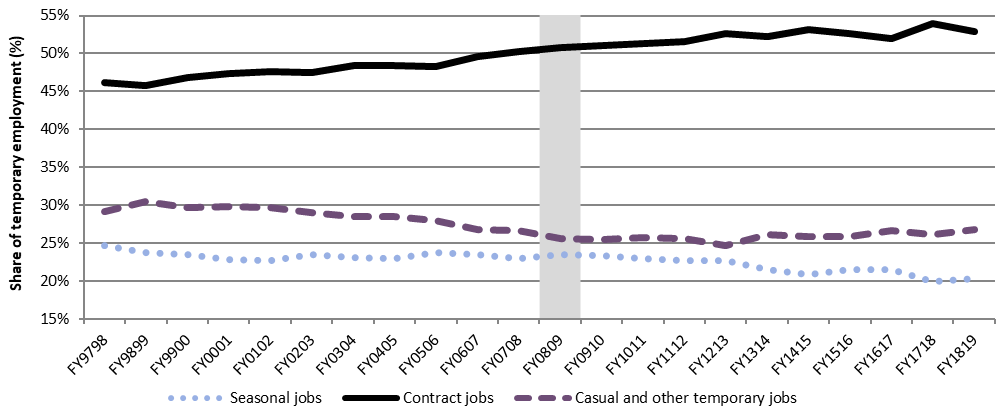

The Labour Force Survey divides temporary employment into 3 categories: seasonal jobs, contract jobs and casual jobs. Seasonal jobs last for a limited period(s) at the same time every year—they are structured by the annual labour demand patterns of industries that have varying labour demand during specific season(s) in a year. Contract jobs are defined by the employer prior to hiring, and are to be terminated at a specific date or at the completion of a specific task or project.Footnote 48 Lastly, casual jobs have work hours that vary substantially from one week to the next, with no pre-arranged schedules and no pay for the time not worked, and limited prospects for regular work in the long-term.Footnote 49

Chart 10 illustrates the distribution of each type of category in temporary employment in Canada over the past 2 decades. Between FY9798 and FY1819, the share of individuals with contract jobs increased from 46.1% to 52.8%, while it decreased for casual jobs (from 29.2% to 26.8%) and seasonal jobs (from 24.7% to 20.4%).

Chart 10 – Text description

| Fiscal year | Seasonal jobs | Contract jobs | Casual and other temporary jobs |

|---|---|---|---|

| FY9798 | 24.7% | 46.1% | 29.2% |

| FY9899 | 23.8% | 45.8% | 30.5% |

| FY9900 | 23.5% | 46.9% | 29.7% |

| FY0001 | 22.8% | 47.4% | 29.8% |

| FY0102 | 22.7% | 47.6% | 29.7% |

| FY0203 | 23.5% | 47.5% | 29.0% |

| FY0304 | 23.1% | 48.5% | 28.5% |

| FY0405 | 23.0% | 48.5% | 28.5% |

| FY0506 | 23.7% | 48.3% | 27.9% |

| FY0607 | 23.5% | 49.6% | 26.8% |

| FY0708 | 23.0% | 50.3% | 26.7% |

| FY0809 | 23.6% | 50.8% | 25.7% |

| FY0910 | 23.4% | 51.1% | 25.5% |

| FY1011 | 22.9% | 51.3% | 25.7% |

| FY1112 | 22.8% | 51.6% | 25.6% |

| FY1213 | 22.8% | 52.6% | 24.6% |

| FY1314 | 21.6% | 52.3% | 26.1% |

| FY1415 | 20.9% | 53.2% | 25.9% |

| FY1516 | 21.5% | 52.7% | 25.9% |

| FY1617 | 21.5% | 51.9% | 26.6% |

| FY1718 | 19.9% | 53.9% | 26.2% |

| FY1819 | 20.4% | 52.8% | 26.8% |

- Note: The shaded area corresponds to a recessionary period in Canada’s economy.

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour force Survey, Table 14-10-0071-01.

In FY1819, Newfoundland and Labrador had the highest share (21.0%) of temporary jobs in Canada, followed by Prince Edward Island (17.9%), New Brunswick (14.3%) and Nova Scotia (13.5%). The share of women with temporary jobs (12.2%) was slightly higher than the share of men (10.2%), while the prevalence of temporary jobs was much higher among youth (aged between 15 and 24 years) compared to individuals in other age groups (see Annex 1.8). This is attributable to the fact that a large share of youth are students, who may use temporary employment as a stepping stone to permanent employment.

In the reporting year, temporary employment represented 11.2% of all employment. When breaking down by categories, contract jobs accounted for 5.9% of all employment in Canada, while the share of casual and seasonal jobs were much lower (3.0% and 2.3%, respectively). The share of contract and casual jobs was higher among women compared to men, but this reversed for seasonal jobs. While the shares of all types of temporary jobs were higher among youth, a notably higher proportion of core-aged workers was employed in contract jobs (5.3%) than the other 2 types of temporary employment (see Table 8).

| Category | Contract jobs Share of total employment (%) | Casual jobs Share of total employment (%) | Seasonal jobs Share of total employment (%) | Temporary jobs Share of total employment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 5.2% | 2.2% | 2.8% | 10.2% |

| Women | 6.7% | 3.8% | 1.7% | 12.2% |

| 15 to 24 years | 13.0% | 10.5% | 7.1% | 30.5% |

| 25 to 54 years | 5.3% | 1.7% | 1.4% | 8.3% |

| 55 years and over | 3.4% | 2.5% | 2.1% | 8.1% |

| Canada | 5.9% | 3.0% | 2.3% | 11.2% |

- Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0071-01.

By industry classification, 8.9% of workers in the goods-producing sector had temporary employment in the reporting year, compared to 11.8% in the service-producing sector. In the goods-producing sector, the Agriculture industry and the Construction industry had the highest share of temporary jobs (11.6% for both industries) in FY1819. The majority of these were seasonal jobs. On the other hand, in the service-producing sector, the Educational services industry had the highest share of temporary jobs (24.8%, mostly composed of contract jobs), followed closely by the Information, culture and recreation industry (22.0%, mostly composed of seasonal and contract jobs)—see Annex 1.8.

Lower earnings and fewer hours of work are generally associated with temporary employment.Footnote 50 Even after controlling for differences in individual and job characteristics (for example, skills proficiency, education, industry and occupation), there is still a wage gap associated with temporary employment.Footnote 51 As applicants for EI regular benefits need a minimum number of hours of insurable employment to be eligible for benefits, workers who previously held temporary employment, in general, have a lower eligibility rate than those who had permanent employment.Footnote 52

However, the coverage rate of EI regular benefits for those who occupied temporary employment is generally higher than those who held permanent employment. This is due to the high proportion (40.0%) of seasonal workers among the unemployed who previously held temporary employment and to the fact that seasonal workers are more likely to have paid EI premiums in the year prior to unemployment given their cyclical employment pattern over a year.

1.4 Summary

In FY1819, the Canadian economy was marked by a slowdown in real GDP growth, attributable to declines in business investments and modest growth in consumption expenditure. Despite disruptions in global trade and ongoing efforts to conclude a revised Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) on trade, Canada’s exports of goods and services rebounded in FY1819 compared to the previous fiscal year.

The Canadian labour market, on the other hand, continued its strong performance in FY1819, as the national unemployment rate reached the lowest level (5.8%) since FY7677. Growth in employment, however, was modest in the reporting year compared to the previous fiscal year, mainly due to a slowed down growth in full-time employment.

In FY1819, a little more than 1 in 3 employed individuals in Canada worked in non-standard employment. Variations by gender, age group, industry and geographic location are evident among different types of non-standard employment. For example, permanent part-time jobs are mostly occupied by women and youth, which is largely due to the flexibility of such type of employment and personal preferences. On the other hand, men are overrepresented in self-employment, and this type of employment is more prevalent in Agriculture, Construction and Professional, scientific and technical services industries. Lastly, temporary employment is more prevalent in the Atlantic provinces and among youth.