Greenhouse gas emissions trends 2012

Environment Canada

August 2012

Table of Contents

Tables and Figures

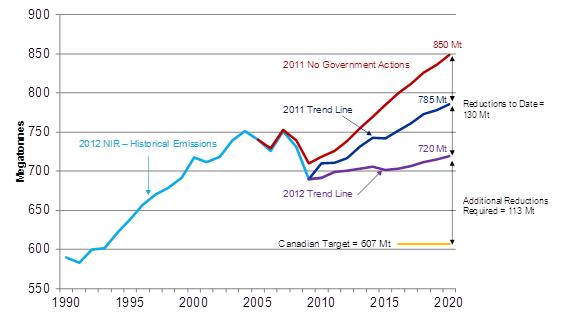

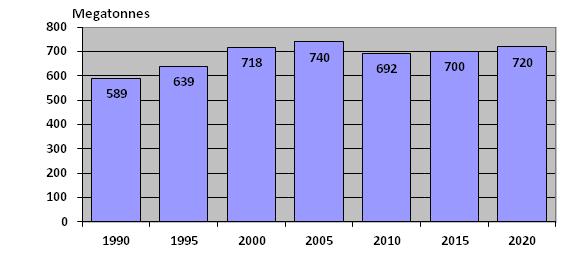

- Figure ES 1 - Scenarios of Canadian emissions to 2020 (Mt CO2e)

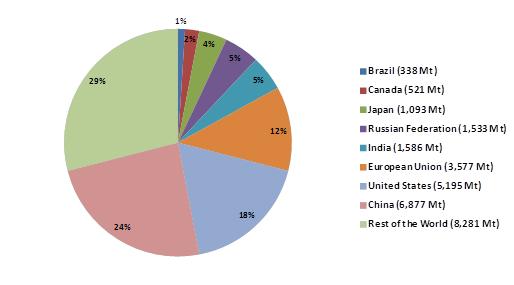

- Figure 1 - Distribution of world carbon dioxide emissions from fuel combustion, 2009

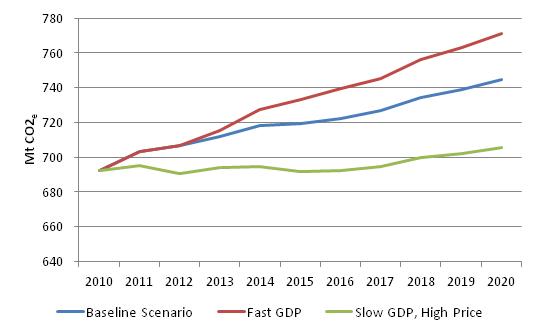

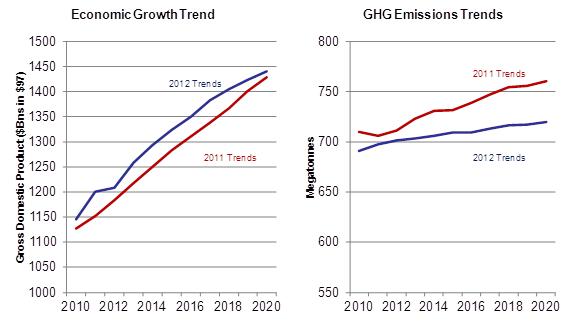

- Figure 2 - Projected GHG emissions under alternative economic assumptions (excluding LULUCF)

- Figure 3 - Total Canadian GHG emissions and projections (with no further government actions): 1990 to 2020 (Mt CO2e - incl. LULUCF)

- Figure 4 - Decoupling of GDP and GHG emissions - 2010 to 2020

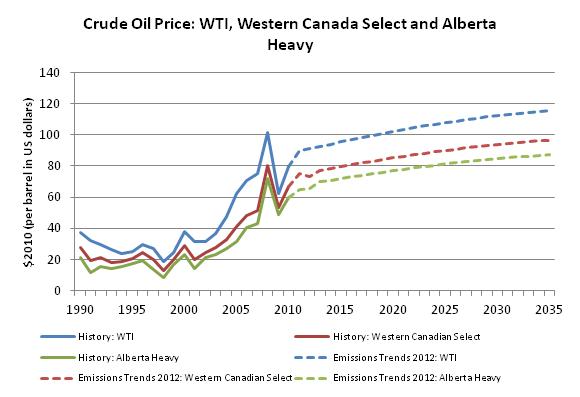

- Figure A.1.1 - Crude oil price: WTI, Western Canada Select and Alberta Heavy ($US 2010/bbl)

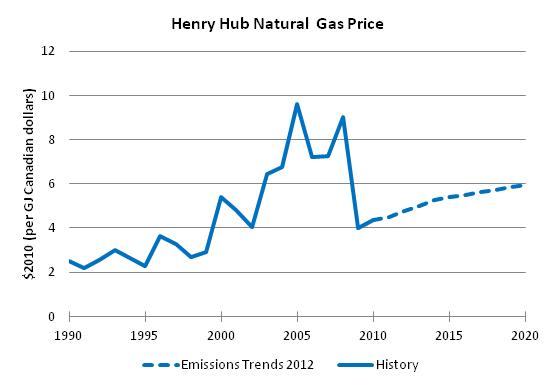

- Figure A.1.2 - Henry Hub natural gas price ($CDN 2010/GJ)

- Figure A.3.1 - Energy, emissions and economy model for Canada

- Table ES 1 - Canadian GHG emissions and government measures (Mt CO2e)

- Table 1 - GHG emissions by economic sector (Mt CO2e)

- Table 2 - Sensitivity of emissions to changes in GDP and world oil price (excluding LULUCF)

- Table 3 - Change in GHG emissions by economic sector (Mt CO2e)

- Table 4 - Transportation: emissions (Mt CO2e)

- Table 5 - Oil and gas sector: emissions by production type (Mt CO2e)

- Table 6 - Upstream oil and natural gas production: emissions and drivers

- Table 7 - Petroleum refining and upgrading sector: emissions and drivers

- Table 8 - Electricity sector: emissions and drivers

- Table 9 - Electricity generation: emissions by fuel type (Mt CO2e)

- Table 10 - Emissions-intensive and trade-exposed industries: emissions and drivers

- Table 11 - Emissions-intensive and trade-exposed industries: emissions by subsector (Mt CO2e)

- Table 12 - Residential sector: emissions and drivers

- Table 13 - Commercial sector: emissions and drivers

- Table 14 - Agriculture sector: emissions (Mt CO2e)

- Table 15 - Waste and Others: emissions (Mt CO2e)

- Table 16 - Provincial and territorial GHG and per capita emissions: 2005 to 2010

- Table 17 - Provincial and territorial GHG emissions: 2005 to 2020 (Mt CO2e)

- Table 18 - Provincial and territorial per capita emissions: 2005 to 2020

- Table 19 - Projected emissions (+) or removals (-) from the LULUCF sector in 2020

- Table 20 - Selected industries' share of GDP in 2020 (%)

- Table A.1.1 - Macroeconomic assumptions: 1990-2020 average annual growth rates (%)

- Table A.1.2 - Crude oil production

- Table A.1.3 - Oil sands disposition

- Table A.1.4 - Natural gas production

- Table A.1.5 - Electricity generation by fuel

- Table A.1.6 - Mass of carbon dioxide emitted per quantity of energy for various fuels

- Table A.1.7 - GHG: measures reflected in projections (policies in place as of Spring 2012)

- Table A.1.8 - Announced 2020 GHG reduction targets of provincial governments (only announced and implemented measures under these targets are included in projections)

- Table A.2.1 - Sensitivity analysis - Change in GDP and/or world oil/natural gas prices

Overview

When Canada signed the Copenhagen Accord in December 2009, it committed to reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to 17% below 2005 levels by 2020, establishing a target of 607 Megatonnes (Mt). This mirrors the reduction target set by the United States.

According to the International Energy Agency, Canada's CO2 emissions from fuel combustion in 2009 accounted for approximately 2% of global emissions. Canada's share of total global emissions, like that of other developed countries, is expected to continue to decline in the face of rapid emissions growth from developing countries.

The Government of Canada's initial focus in tackling GHG emissions has been directed at the largest source of Canadian emissions through regulation of the transportation sector, as well as actions to reduce emissions from electricity generation. The Government is now turning its focus to work with partners in other key economic sectors, in particular, working with our partners in the oil and gas sector to make further progress on meeting our target.

The future path of greenhouse gas emissions in Canada will depend on a number of factors including: economic activity, population, development of energy markets and their influence on prices, technological change, consumer behaviour, and government actions.

Last year, Canada's GHG emissions were projected to be 785 Mt in 2020. Since that time, there have been several key developments and GHG emissions are now projected to be 65 Mt lower at 720 Mt in 2020. This is despite the fact that Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is projected to be slightly higher in 2020 in this year's projection. The decline in projected emissions, when compared to last year, is influenced by four main factors:

- Emissions are increasingly becoming decoupled from economic growth. Changes in behaviour by consumers and businesses, in part due to federal, provincial and territorial actions, are leading to a decline in emissions intensity.

- Projected sectoral shifts in the economy are also contributing to this improvement in emissions intensity. Compared to last year's report, projected growth for the emissions-intensive sectors is now lower, while it is now higher for the less emissions-intensive sectors. This reduces projected emissions in 2020, even though total GDP is projected to be slightly higher.

- For the first time, the contribution of the land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) sector to achieving Canada's target is included in our projections.

- This year's projections also have a new, lower starting point as the most recent data show emissions were significantly lower in 2010 than previously estimated. Last year, emissions were estimated to be 710 Mt and since that time, preliminary data collected by Statistics Canada and assessed for the National Inventory Report 1990-2010: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada (NIR) put Canada's actual emissions in 2010 at 692 Mt.

Canada's Greenhouse Gas Inventory shows a decoupling of GHG emissions from economic growth

Canada's total greenhouse gas emissions in 2010 were 692 Mt, essentially unchanged from 2009 levels (a 0.25% increase).This means that between 2009 and 2010, Canada's emissions remained steady despite economic growth of 3.2%.

Over the last two decades, technological and structural changes, along with increases in efficiency, have acted to create this decoupling of emissions and economic growth. The Canadian economy has experienced a substantial decline in energy intensity as industrial processes have become more efficient and lower-emissions and service-based industries have grown. As well, emissions from energy generation have declined, primarily due to changes to the generation mix and closure of coal-fired generating units. As a result, economic activity and the level of greenhouse gas emissions are becoming increasingly independent. Between 2005 and 2010, the economy grew by 6.3% whereas Canadian greenhouse gas emissions decreased by 6.5%.

Per capita emissions in 2010 fell to 20.3 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per person, their lowest level since tracking began in 1990. In comparison to the 2005 level (22.9 t CO2 eq/capita), per capita emissions in 2010 are 2.6 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent lower. Canada is making steady progress towards its commitment to reduce GHG emissions. Of note, since 2005, annual greenhouse gas emissions have dropped by 48 megatonnes and emissions have declined in almost all sectors, including oil and gas and electricity generation.

Emissions intensity continues to improve through 2020 with help from federal, provincial, and territorial actions

In this year's report, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is projected to be slightly higher in 2020 than in the previous report (by 0.8%), while GHG emissions are lower (by 5.3%). The projected decline in GHG emissions is thus associated with a reduction in intensity, implying greater de-coupling between GDP and GHGs. The improvements in emission intensity are in part due to: i) increased contribution of the services sector, which typically emits less emissions per dollar of GDP; and ii) actual emissions in 2010 were lower than projected, while actual GDP was higher. The decline in emissions intensity was also due to the fact that consumers and businesses are making more progress in reducing emissions. Government programs are contributing to this by helping to accelerate the adoption of energy efficient technologies and cleaner fuels.

Canada is moving forward to regulate GHGs on a sector-by-sector basis, aligning with the U.S where appropriate. The Government of Canada has started with the transportation and electricity sectors - two of the largest sources of Canadian emissions - and plans to move forward with regulations in partnership with other key economic sectors, including oil and gas. Last year's report included emissions regulations for light-duty vehicles for the model years 2011-2016 as well as an electricity performance standard to phase-out coal-fired electricity, Alberta's Specified Gas Emitters Regulation, British Columbia's carbon tax and Quebec's carbon levy. Provincial policies such as Ontario's phase-out of coal-fired electricity also made important contributions. Projected emissions levels in the 2012 version of the report have further declined, in part through the inclusion of further federal actions on additional emissions regulations for light-duty vehicles for the 2017-2025 period as well as heavy duty vehicle regulations. Recent provincial actions (e.g., Quebec's cap-and-trade, Nova Scotia's emissions cap for electric utilities, increased stringency of building energy codes, equipment standards and requirements for capturing methane from landfill gas) are also included. Total emissions in 2020 are projected to decrease to 720 Mt.

The future trajectory of Canadian GHG emissions can, and will, be influenced by further government actions, technological change, economic conditions, and developments in energy markets. Recognising this, Environment Canada has developed scenarios for projected emissions based on different assumptions regarding future economic and energy market developments.

For the first time, there is recognition of the contribution of the Land Use, Land-Use-Change and Forestry sector

The Land Use, Land-Use-Change and Forestry sector (LULUCF) has been internationally recognised as an important consideration in global accounting frameworks for emissions reductions. Improvements in greenhouse gas related activities within Canada's LULUCF sector can make an important contribution towards reducing national emissions levels, given Canada's large supply of forest and cropland.

This 2012 Emissions Trends Report represents a key milestone for Canada in moving towards the inclusion of the LULUCF sector in accounting of GHG emissions. New projections allow the inclusion of the LULUCF sector in emission projections for the first time. Current estimates suggest a net contribution of 25 Mt of GHG emissions towards the 2020 target. While these estimates are preliminary in nature and will change as a result of ongoing efforts to improve data and methodologies as well as the consideration of alternative accounting approaches, they provide a solid first step toward recognizing the important contribution from LULUCF.

This important step will encourage advancement in policies and measures to make further progress towards Canada's GHG reduction goals.

The report projects that Canada is one half of the way toward meeting its Copenhagen Commitment

Overall, this report demonstrates that Canada is making significant progress towards meeting its 2020 target for GHG emissions. Beyond federal initiatives, provincial and territorial governments are contributing with significant action of their own under their respective jurisdictional targets. Taken together, the measures of the federal and provincial governments, combined with the efforts of consumers and businesses, are projected to have a significant impact on emissions over the coming years.

| 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| * Includes the contribution of LULUCF in 2015 and 2020. | ||||

| Emissions - Assuming No Government Measures (2011) | 740 | 718 | 784 | 850 |

| Emissions - with Existing Government measures (2012 update)* | 740 | 692 | 700 | 720 |

Last year, Canada's GHG emissions were projected to be 850 Mt in 2020 under a scenario assuming no government measures to reduce emissions. Taking into account existing measures of federal, provincial and territorial governments, it was projected that emissions would be 785 Mt in 2020. This reduction of 65 Mt represented one quarter of the reductions needed to meet Canada's target of 607 Mt. This year, GHG emissions are now projected to be 720 Mt in 2020, as a result of all the developments outlined in this report. The gap between the initial projected business-as-usual GHG emissions in 2020 (850 Mt) and the 607 Mt target now has been closed by 130 Mt - one half of the way to meeting Canada's target. Upcoming federal policies, in particular oil and gas regulations, along with further provincial measures, will further contribute to the additional 113 Mt required for Canada to meet its commitments under the Copenhagen Accord.

Figure ES 1 - Scenarios of Canadian emissions to 2020 (Mt CO)

Preface

Consistent with its goal of becoming a “World Class Regulator”, and ensuring greater transparency, Environment Canada has committed to publish emissions projections annually. This is the second annual report, building on last year's publication, Canada's Emissions Trends 2011.

The analysis presented in this report incorporates the most up-to-date statistics on GHG emissions and energy available at the time that the technical modeling was completed[1], and is based on scenarios of emissions projections using a detailed, proven Energy, Emissions and Economy Model for Canada.

Last year, projected emissions were 710 Mt in 2010. Since that time, data collected by Statistics Canada for 2010 has been assessed for the National Inventory Report 1990-2010: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada (NIR) in accordance with standards set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change - a United Nations body. Estimates published in the 2012 NIR show that Canada's emissions in 2010 were actually 2.6% lower at 692 Mt. Subsequently, emissions projections in this paper have been revised down compared to the 2011 Report to reflect these changes as well as factors such as slower than expected economic growth for certain emissions-intensive subsectors.

Provincial and federal government departments were consulted during the model's development and were invited to provide their input and suggestions for improvement. Environment Canada also consulted industry experts to improve the model and core technical assumptions.

The majority of data and advice received from sector experts and authorities for the modelled emissions scenarios have been subjected to rigorous consultations. For example, the National Energy Board has extensive consultation processes in place to ensure their assumptions of energy demand and supply growth are robust; the input they provided to Environment Canada reflects those consultations.

In addition, the methodology used to create the projections underwent a peer review by a panel of experts in 2010/2011. In the peer review, the experts assessed the modeling methodology on its reasonableness and robustness, reviewed the sources for the key macroeconomic and energy-related assumptions, and made suggestions on how to continue improving the methodology in future rounds. While we are working with a highly detailed and sophisticated model, as with all projections, the estimates in this paper should be seen as representative of possible outcomes that will, in the end, depend on economic, social and other factors, including future government policy.

Questions and requests for further information on the analysis underlying this report should be directed to: AMD_EAD@ec.gc.ca

Canada's GHG Emissions in a Global Context

It is important to put Canada's situation into context by comparing to other countries. According to the International Energy Agency, Canada's CO2 emissions from fuel combustion in 2009 accounted for approximately 2% of global emissions[2].

Global emissions of CO2 have increased by 38% between 1990 and 2009. Over the same period, Canadian CO2emissions have increased by less than 19%. Canada's share of total global emissions, like that of other developed countries, will continue to decline in the face of rapid emissions growth from developing countries, particularly China and India. By 2005, China had overtaken the U.S. as the world's largest overall greenhouse gas emitter, and by 2020 China's greenhouse gas emissions are expected to account for 27% of global emissions, up from about 20% in 2005.

Figure 1 - Distribution of world carbon dioxide emissions from fuel combustion, 2009

Source: www.ec.gc.ca/indicateurs-indicators/default.asp?lang=en&n=54C061B5-1

The Copenhagen Accord is a critical instrument for addressing such dramatic escalation in global emissions because it is signed by 140 nations, representing 85% of the world's GHG emissions. For example, the Accord was signed by China, the U.S., Brazil and India, which together account for over 40% of global emissions. In contrast, none of these major emitters had commitments under the Kyoto Protocol, an agreement that involved commitments of only 40 nations representing 27% of global emissions.

When Canada signed the Copenhagen Accord in December 2009, it committed to reducing its GHG emissions to 17% below 2005 levels by 2020. This mirrors the reduction target set by the United States, which is also following a sector-by-sector approach. Canada is moving in alignment with the U.S. given the importance of our economic relationship. Every day, $1.8 billion in goods and services crosses the border, and fully 85% of Canada's trade is with the United States. Comparatively, Canada has relatively less trade with other large partners. This makes the United States Canada's primary link into global value chains - which is the transformation process of a product from raw materials to finished good, or the process of developing tradable services. The GHG regulations for light duty and heavy duty vehicles are examples of an aligned approach. With aligned regulations, light duty vehicle and heavy duty vehicle manufacturers face the same rules in each country, providing greater investment certainty and a level playing field. Furthermore, all Canadians benefit from the efficiency of having a single set of regulations in the integrated North American auto sector.

Emissions by Activity and Economic Sector

There are several methods to categorise the sources of greenhouse gas emissions that arise across Canada. In Canada's National Inventory Report (NIR)[3], as specified by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change definitions, greenhouse gas emissions are primarily categorized by emitting activity: e.g., emissions from energy use, fugitive emissions, transportation emissions, and emissions from industrial processes. However, for the purposes of analyzing trends and policies, it is useful to allocate emissions to the economic sector from which they originate. As such, both this report and the 2012 NIR present emissions by economic activity.

Historical Emissions

Historical emissions estimates within this report are taken from the NIR which is submitted to and reviewed by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).Every year the estimates are updated to reflect the availability of data as well as improvements and refinements to data sources and methodological techniques. For this reason, the historical emissions reported here will differ from those reported in Canada's Emissions Trends 2011.

From 1990 to 2005, total emissions grew from 589 Mt to 740 Mt. The majority of this increase occurred in the transportation sector, the oil and gas sector and the electricity sector. In the transportation sector, changes in subsectors including light-duty and heavy-duty vehicles caused an increase in emissions of 42 Mt over this period. Expansion and adoption of new extraction technologies resulted in an increase in emissions of 60 Mt in the oil and gas sector. The electricity sector accounted for a further 29 Mt of the increase in total emissions.

Greenhouse gas emissions have decreased in almost every sector of Canada between 2005 and 2010. This is a result of factors such as the global economic downturn, changes to energy efficiency technology, changes in energy prices, and a decrease in the energy intensity of the economy. Moreover, federal and provincial government actions to reduce emissions had a significant impact on emissions over this time period.

Table 1 shows historical emission levels for selected years up to 2010 (the last available year of historical emissions numbers under the NIR for 2012) for each of the major economic sectors generating emissions.

| Mt CO2equivalent |

1990

|

2000

|

2005

|

2006

|

2007

|

2008

|

2009

|

2010

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil and Gas |

100

|

150

|

160

|

161

|

165

|

160

|

161

|

154

|

| Electricity |

92

|

128

|

121

|

115

|

124

|

112

|

96

|

99

|

| Transportation |

128

|

155

|

170

|

169

|

172

|

172

|

162

|

166

|

| Emissions Intensive & Trade Exposed Industries |

96

|

88

|

90

|

89

|

90

|

87

|

74

|

75

|

| Buildings |

70

|

81

|

85

|

80

|

85

|

85

|

82

|

79

|

| Agriculture |

54

|

65

|

67

|

66

|

68

|

68

|

67

|

69

|

| Waste and Others |

49

|

50

|

48

|

46

|

48

|

47

|

47

|

50

|

| National GHG Total |

589

|

718

|

740

[4]

|

726

|

751

|

731

|

690

|

692

|

Transportation

Emissions from transportation (including passenger, freight, and off-road emissions) are the largest contributor to Canada's greenhouse gas emissions, representing 24% of overall greenhouse gases in 2010.

Between 1990 and 2005, emissions in the transportation sector increased 33% from 128 Mt in 1990 to 170 Mt in 2005. This was largely driven by a strong period of economic growth as well as a shift from cars to light-duty trucks.

Since 2005, transportation emissions have decreased 4 Mt. Light-duty vehicles have become increasingly more fuel efficient. For example, between 2005 and 2010, the sales-weighted on-road fuel economy for new cars has improved from 8.5 litres per 100 km to 6.8 litres per 100 km, while the sales-weighted on-road fuel economy for new light trucks has improved from 12.7 litres per 100 km to 8.5 litres per 100 km. Offsetting factors include an increase in number of vehicles on the road and kilometres driven.

Electricity

Historically over the 1990 to 2005 period, emissions from the electricity sector increased in parallel with rising demand for electricity both domestically and to satisfy export demand from the United States. Additionally, fossil fuel power generation became more prominent in the overall generating portfolio between.

Electricity-related emissions (including heat generation) have generally declined since 2005 due to factors such as a return to service of a number of nuclear units and fuel switching to natural gas, as well as a decline in coal-fired electricity generation in Ontario. These factors coupled with the economic downturn have seen emissions from the electricity sector decrease by 22 Mt between 2005 and 2010.

Oil and Gas

Conventional oil and gas production and petroleum refining emissions are related primarily to the production, transmission, processing, refining and distribution of all oil and gas products. In 2010, the Oil and Gas economic sector produced the second largest share of greenhouse gas emissions in Canada (22%).

Emissions from this sector increased by 60 Mt over the 1990 to 2005 time period as the sector expanded and adopted new extraction processes. However, GHG emissions from the Oil and Gas sector have fallen by 6 Mt between 2005 and 2010. This more recent decrease in the emissions from the oil and gas sector is the result of a number of factors including a lower global demand for petroleum products during the economic downturn, as well as the gradual exhaustion of conventional natural gas and oil resources in Canada.

Emissions-Intensive and Trade-Exposed Industries (EITE)

Emissions from the Emissions-Intensive Trade-Exposed Industry sector[5] were responsible for 16% of total Canadian emissions in 1990 falling to 12% in 2005. In more recent years, emissions have fallen further as a result of the economic downturn and the continued evolution of Canadian production towards other sectors and services, representing an additional decrease of 15 Mt between 2005 and 2010 (11% of total emissions).

The decline in emissions was also due to the contribution of several factors such as the installation of nitrous oxide abatement technology in Canada's only adipic acid manufacturing plant and the improved emission control technologies for perfluorocarbons within the aluminum industry. Energy efficiency measures, replacement of raw materials with recycled materials, and use of unconventional fuels such as biomass and waste in the production processes, were also responsible for the reductions.

Buildings

Emissions in Canada's service industry and residential buildings increased by 15 Mt overall between 1990 and 2005. However, more recently, between 2005 and 2010, emissions decreased by 6 Mt. This was driven by a 5 Mt decrease in commercial buildings, mainly due to improved energy standards and the adoption of higher-efficiency furnaces and other improved appliances.

Agriculture

Canada's agricultural emissions consist mainly of methane and nitrous oxide from animal and crop production systems. Emissions have remained relatively stable over the 2005 to 2010 time period increasing by only 2 Mt or 3%, following an increase of 13 Mt from 1990 to 2005. Increasing emissions from on-farm fuel use and crop production have been partially offset by decreasing emissions from animal production since 2005.

Waste and Others

Emissions from the Waste and Others sector have remained relatively stable over the period. GHG emissions from landfills increased only slightly over the time period, as provincial government measures aimed at capturing landfill gas from solid waste helped to slow growth. In contrast, emissions from coal production have nearly doubled over the 2005 to 2010 time period increasing by nearly 3 Mt.

Emissions Scenarios and Key Drivers

Greenhouse gas emissions in Canada are driven by a number of economic drivers (e.g., energy demand and supply mix, economic growth, among others). Looking ahead, projections of future emissions are greatly influenced by the underlying assumptions about the expected development of these economic drivers over time[6]. Changing assumptions about any of these factors will alter the future path of emissions.

The approach adopted for development of the emissions scenarios presented here relies on a baseline set of assumptions. In this respect, the economic projections are calibrated to those used by Finance Canada in Budget 2012. The longer-term projections incorporate productivity growth projections and Statistics Canada's population growth projections. Similarly, forecasts of major energy supply projects from the National Energy Board were incorporated for key variables and assumptions in the model (e.g., oil sands production, large hydro capacity expansions, nuclear refurbishment and additions). Supply forecasts are based on consultation with industry experts and reflect the Government's most recent views regarding the evolution of Canada's energy supply sector. The projections also incorporate data from the National Inventory Report 1990-2010: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada (NIR), Natural Resources Canada, and the U.S. Energy Information Administration. For a more detailed summary of key economic data and assumptions see Annex 1.

It is impossible to predict Canada's greenhouse gas emissions with certainty, given the importance of the economic drivers and the intrinsic uncertainty related to the evolution of these drivers (e.g. GDP, energy prices) in the future. Government policy also has a significant impact on emissions, (including expected future policies) along with changes in behaviour as individuals place more importance on environmentally-friendly products and businesses adopt more environmentally-friendly processes. While the modeling explicitly recognizes technological progress (e.g., known advanced energy efficient technologies will become more cost-effective over time), it is virtually impossible to predict what new technologies will be developed and commercialized in the future. In this respect, future emissions will be shaped by existing government measures, as well as future measures that will be implemented as part of Canada's plan to reduce emissions to the target established in the Copenhagen Accord.

Taking into account the economic drivers described above, with no major technology changes and factoring in current government measures and land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF), results in a baseline scenario whereby emissions reach 720 Mt by 2020 (or 20 Mt below 2005 levels).

Given the uncertainty regarding the economic drivers, this scenario should be seen as one estimate within a set of possible emissions outcomes in 2020, depending on economic developments and underlying assumptions. To get a sense of the sensitivity of emissions to economic developments, emissions were calculated under a series of alternative assumptions involving relatively minor variations in assumed economic growth rates for Canada and world oil prices[7].

For example, under a scenario of high GDP growth, reference world oil prices and no further government action, Canadian emissions, before accounting for contributions from LULUCF, could reach almost 771 Mt by 2020. Alternatively, with low GDP growth and high world oil, 2020 emissions, before accounting for contributions from LULUCF, could be as low as 705 Mt. Figure 2 illustrates these alternative emissions pathways. For a more detailed explanation of this sensitivity analysis, see Annex 2.

Figure 2 - Projected GHG emissions under alternative economic assumptions (excluding LULUCF)

These sensitivities illustrate that Canada's emissions projections should not be interpreted as a precise prediction or forecast of our emissions since, as outlined above, actual emissions will be determined by a range of as yet unknown developments in key drivers. Rather, the projections should be viewed as one plausible outcome for future emissions that provides a reference point for evaluating the impact of economic and technological developments, as well as assessing the impact of existing and future government measures.

It is important to note that the projection of emissions in this report is based on existing government measures as of the spring of 2012 only, and does not reflect the impact of further federal measures that are under development as part of the government's plan to reduce GHG emissions to 607 Mt by 2020, nor new provincial measures that could be undertaken in the future. The impact of government measures on emissions is described in more detail in a later section.

| Cases | Impact on GHG emissions relative to the reference scenario (Mt CO2e) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2020 | Change, 2005 to 2020 |

|

| Slow GDP - High World Oil Prices |

740

|

705

|

-35

|

| Fast GDP - Reference World Oil Prices |

740

|

771

|

31

|

| Baseline Scenario |

740

|

745

|

5

|

| Sensitivity Range (including all scenarios examined - see Annex 2) |

740

|

705 to 771

|

-35 to 31

|

National Emissions Projections

Figure 3 depicts the total projected Canadian greenhouse gas emissions[8] in the absence of further government actions for selected years from 1990 to 2020. The projection suggests that Canadian emissions peaked in 2005. By 2020, emissions, including the contribution of LULUCF, are projected to be 720 Mt. This is comparable to the emissions level in 2000.

Figure 3 - Total Canadian GHG emissions and projections (with no further government actions): 1990 to 2020 (Mt CO2e - incl. LULUCF)

Emissions Projections by Sector

Over the last two decades, the Canadian economy has become significantly less energy intensive and there continues to be an accelerated decoupling between economic growth and greenhouse gas emissions levels. Canada's total greenhouse gas emissions in 2010 were 692 Mt, and were essentially unchanged from 2009 levels with only a 0.25% increase.This means that between 2009 and 2010, Canada's emissions remained steady despite economic growth of 3.2%.

However, since a strong connection still remains between economic growth and greenhouse gas emissions, emissions are projected to rise over the period, but at a rate lower than economic growth. As the economy grows beyond 2010, total emissions are expected to begin to increase. Absent further government action, by 2020 emissions are projected to reach 720 Mt, a decrease of 20 Mt from 2005.

Table 3 illustrates how the trends in each economic sector vary based on how economic drivers and government policies shape emissions in that sector. Electricity generation is the one major economic sector that is projected to reduce emissions significantly, in large part due to the combined impact of government measures to create a cleaner electricity system. Electricity emissions are projected to decline by 41 Mt (34%) between 2005 and 2020. On the other hand, increased production in the oil sands is expected to result in overall oil and gas emissions increasing by 44 Mt (28%) between 2005 and 2020.

The following pages provide more detail on expected emissions trends by economic sector.

| 2005 | 2020 | Change, 2005 to 2020 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Transportation | 170 | 171 | 1 |

| Electricity | 121 | 80 | -41 |

| Oil and Gas | 160 | 204 | 44 |

| Emissions-Intensive Trade- Exposed Industries | 90 | 83 | -7 |

| Buildings | 85 | 91 | 6 |

| Agriculture | 67 | 65 | -2 |

| Waste and Others | 48 | 51 | 3 |

| Sub-Total | 740 | 745 | 5 |

| Expected LULUCF Contribution | N/A | -25 | -25 |

| Total | 740 | 720 | -20 |

Transportation

Total transportation emissions are projected to increase by about 1 Mt - from 170 Mt in 2005 to 171 Mt by 2020 - a marked deceleration of growth from the historical long-term trend. This deceleration is expected to occur as a result of higher gasoline and refined petroleum prices, and greater fuel efficiency in vehicles being accelerated by federal vehicle emissions regulations[9].

As depicted in Table 4, the transportation sector is comprised of several distinct subsectors - passenger, freight, and air and others (e.g., rail and marine)[10]. Each sector exhibits different trends and responds to a very different mix of technological options. For example, emissions from passenger transportation are projected to decrease by 11 Mt between 2005 and 2020, while those for ground freight and off-road are projected to grow by 11 Mt.

Under both phases of light duty vehicle regulations, spanning model years 2011 to 2025, the fuel efficiency of passenger vehicles will increase by some 35%. The sales-weighted fuel economy of new passenger vehicles is projected to improve from 7.9 L/100km in 2010 to 6.0 L/100km in 2020 and to 5.0 L/100km by 2025.

Likewise, emissions from freight are expected to decrease as a result of various federal, provincial and territorial programs. The recently announced Heavy Duty vehicle regulations will improve the average fuel efficiency of trucks from 2.5 litres/100 tonne-km to 2.1 litres/100 tonne-km by 2020.

“Drilldown” - Light-Duty Vehicle Emissions and Regulations

Transportation is a significant source of GHG emissions in Canada. In 2010, transportation sources accounted for 24% of total Canadian GHG emissions, of which 55% were emissions arising from the light-duty vehicle sub-sector (i.e. cars; small trucks). This has led the Government of Canada to target light-duty vehicles as a high priority for regulations.

In recognition of the integrated North American economies and transportation industry, the governments of Canada and the U.S. have established aligned policies for national regulations to reduce emissions from the transportation sector.

In October 2010, the Government of Canada released the final Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations (LVD1), which prescribes progressively more stringent annual emission standards for new vehicles of model years 2011 to 2016. The Government also published a Notice of Intent for “phase 2” of the regulations to develop more stringent GHG emissions standards for light-duty vehicles of model years 2017 to 2025 (LVD2).

These regulations will achieve significant and sustained GHG reductions and fuel saving benefits. By 2020, preliminary estimates suggest that Canadian regulations for model years 2011 to 2016 will lead to annual reductions of between 9 and 10 Mt in Canada. Preliminary estimates also suggest that the proposed regulations for model years 2017 to 2025 will contribute to achieving the Copenhagen 2020 target by reducing GHG emissions by an additional 2 to 3 Mt in 2020. Greenhouse gas emissions are expected to be reduced further beyond 2020, as the 2021 to 2025 reductions come into effect.

Under the first phase of the regulations, the average fuel efficiency of new vehicles is projected to increase by 15% between 2010 and 2016. The regulations continue to establish progressively stringent annual fleet average emission standards. Under the second phase of the regulations, average fuel efficiency of new vehicles is projected to increase by 37% between 2016 and 2025. Overall, the cumulative improvement from LDV1 and LDV2 is projected to increase the average fuel efficiency of new vehicles by 57% over the period from 2010 to 2025.

Unconventional vehicles (those that use diesel, alternative fuels, and/or hybrid electric systems) are projected to play a significant role in meeting more stringent fuel economy standards. This means that companies will continue to offer a full range of vehicle types to meet the transportation needs of Canadians, but that consumers can expect to see a greater choice of alternative vehicles available for sale. As a result, it is anticipated that the market penetration of existing advanced technology vehicles, such as hybrid-electric vehicles (e.g. Toyota Prius), plug-in hybrid-electric vehicles (e.g. Chevrolet Volt) and fully-electric vehicles (e.g. Nissan Leaf), will increase in Canada.

These vehicles have the potential to allow driving habits to change significantly, but, at the same time, reduce CO2emissions significantly. Moreover, electric vehicles offer zero tail pipe emissions since electricity is generated at centralized utilities which would significantly reduce localized smog and other air pollutant emissions.

Consumers that purchase a vehicle would be expected to recover any higher upfront costs through fuel savings between 5 to 8 years for passenger cars, and a period of only 2 to 4 years for light trucks. In fact, the lifetime fuel savings for a vehicle is projected to be 2 to 3 times the estimated increase in vehicle cost or approximately $1,950 in 2025. Thus, the performance standard represents an economically efficient and low cost approach to emissions reductions. Under these regulations, greenhouse gas emissions from light-duty vehicles are projected to decrease by 16% between 2005 and 2020. Moreover, these regulations will have a significant impact on total transportation emissions. Canadian average annual Transport greenhouse gas emissions increased at 1.9% per year over 1990 to 2000 while they are projected to increase by only 0.4% on average over 2010 to 2020. As the second phase of the regulations take hold, and regulations for Heavy Duty Trucks increasingly impact other transport subsectors, average annual transport GHG emissions decrease by 4% from 2020 to 2030.

It is projected that there will be almost 26 million vehicles on the road by 2025. The emissions reduction of 15% due to the full phase in of LDV1 and LDV2 over the period from 2010 to 2025 would be equivalent to removing approximately 3.7 million vehicles from the road.

Oil and Gas

This projection does not include the impact of future oil and gas regulations. While work is currently underway, we have not yet reached a point where the effects can be reliably quantified. It is anticipated that these regulations will be included in Canada's Emission Trends in the future, and this inclusion will result in significant additional reductions by 2020 relative to the projections herein.

Upstream Oil and Gas Production

Absent further government action, emissions from upstream oil and gas production, including pipelines but excluding refining and upgrading[11], are estimated to grow from 125 Mt in 2005 to 160 Mt in 2020. This increase is primarily driven by the growth in bitumen production, where emissions are expected to increase from 19 Mt in 2005 to about 80 Mt by 2020. Specifically, emissions from oil sands mining are projected to double while emissions from in situ production are expected to increase more than five times from 10 Mt in 2005 to 55 Mt in 2020.

Over this same period, emissions from conventional crude oil production are expected to fall from 33 Mt in 2005 to 27 Mt in 2020, while those from natural gas production and processing are expected to fall from about 57 Mt in 2005 to 44 Mt by 2020.

Emissions from the pipeline transport of oil and natural gas are expected to fall from about 16 Mt in 2005 to 9 Mt by 2020. The emissions associated with the upgrading of oil-sands bitumen[12] are expected to rise from 14 Mt in 2005 to 23 Mt by 2020. Further details on emissions from oil-sands upgrading are reported in the section below dealing with the refining industry.

| 2005 | 2010 | 2020 | Absolute Change 2005 to 2020 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Gas Production and Processing | 57 | 46 | 44 | -13 | |

| Conventional Oil Production | 33 | 29 | 27 | -6 | |

| Conventional Light Oil Production | 10 | 9 | 9 | -1 | |

| Conventional Heavy Oil Production | 21 | 18 | 15 | -6 | |

| Frontier Oil Production | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Oil Sands | 32 | 48 | 104 | 73 | |

| Bitumen In situ | 10 | 18 | 55 | 45 | |

| Bitumen Mining | 9 | 13 | 25 | 16 | |

| Bitumen Upgrading | 14 | 17 | 23 | 9 | |

| Oil and Natural Gas Transmission | 16 | 11 | 9 | -7 | |

| Downstream Oil and Gas | 22 | 20 | 20 | -2 | |

| Petroleum Products | 20 | 18 | 18 | -2 | |

| Natural Gas Distribution | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Total | 160 | 154 | 204 | 44 | |

| 2005 | 2010 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Oil Production | |||

| Emissions (Mt CO2e) | 33 | 29 | 27 |

| Production (1,000 barrels/day) | 1361 | 1228 | 1112 |

| Natural Gas Production [13] and Processing (including Pipelines) | |||

| Emissions (Mt CO2e) | 57 | 46 | 44 |

| Production (billion cubic foot (BCF))[14] | 6951 | 5868 | 4711 |

| Bitumen Production | |||

| Emissions (Mt CO2e) | 19 | 31 | 80 |

| Production (1,000 barrels/day) | 1064 | 1614 | 3263 |

Petroleum Refining and Upgrading

Table 7 displays emissions associated with petroleum refining and upgrading. As noted above, the greenhouse gas emissions from upgrading bitumen into synthetic crude oil are included in the petroleum refining industry category. From 2005 to 2020, emissions from bitumen upgrading are projected to increase by 9 Mt, while emissions from petroleum refining are projected to decline by 2 Mt.

| 2005 | 2010 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Refineries | |||

| Emissions (Mt CO2e) | 20 | 18 | 18 |

| Refined Petroleum Processed (1,000 barrels/day) | 2165 | 2144 | 2359 |

| Upgraders | |||

| Emissions (Mt CO2e) | 14 | 17 | 23 |

| Upgraded Products (1,000 barrels/day) | 611 | 865 | 1359 |

Electricity Generation

Emissions from electricity generation and distribution have historically increased over time as a result of the need to increase generating output to supply a growing economy. However, emissions from this sector are now declining, and that trend is expected to continue over the next decade. Between 2005 and 2020, electricity generation emissions are expected to decrease by 41 Mt, from 121 Mt in 2005 to 80 Mt in 2020, as a result of the federal Emissions Performance Standard for coal-fired electricity generation as well as provincial measures to shift away from coal as a fuel source and measures to encourage the development of renewables.

| 2005 | 2010 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emissions (Mt CO2e) | 121 | 99 | 80 |

| Generation (TWh) | 557 | 529 | 598 |

Against a backdrop of decreasing coal power usage, fossil fuel generation is expected to vary with the availability of electricity from hydro, nuclear and renewable power sources such as wind. Hydro power generation is expected to increase throughout Canada, although the growing demand for electricity in Alberta is expected to continue being met primarily through increased generation from coal and natural-gas-fuelled power plants[15]. On a national level, electricity generation from natural gas, a relatively cleaner form of energy than coal, is expected to double between 2005 and 2020.

| 2005 | 2010 | 2020 | Absolute Change 2005 to 2020 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coal | 98 | 80 | 57 | -41 |

| Refined Petroleum Products | 9 | 2 | 3 | -6 |

| Natural Gas | 13 | 16 | 19 | 6 |

| Non-combustion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 121 | 99 | 80 | -41 |

The proportion of utility electricity generation coming from wind power and other renewable sources (other than hydro and nuclear) increases in the 2005 to 2020 period, starting at only about 0.3% in 2005 and reaching 6% of total generation by 2020. These forms of electricity generation are assumed to be emissions free.

Emissions-Intensive and Trade-Exposed Industries

As shown in Tables 10 and 11, emissions in the emissions-intensive trade-exposed (EITE) industries (which include, among others, chemicals, pulp and paper, cement and iron and steel) are expected to experience modest growth as the economy recovers in 2010 and onwards. By 2020 emissions are projected to be 7 Mt lower than 2005 levels, at 83 Mt.

| 2005 | 2010 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emissions (Mt CO2e) | 90 | 75 | 83 |

| Gross Output of EITE sectors (1997 $billions) | 139 | 121 | 134 |

Emissions remain stable over the 2005 to 2020 projection period in most of the EITE subsectors, owing to modest growth and continued improvements in emission intensities. Emissions are expected to decrease in the pulp and paper and base metal smelting subsectors while mining is increasing.

Buildings

Residential

As shown in Table 12, greenhouse gas emissions from the residential sector (e.g., houses, apartments and other dwellings) are expected to remain stable between 2005 and 2020.

The number of households, which is a key driver of growth in residential sector emissions, is expected to increase by 2.8 million from 2005 to 2020 but residential emissions are almost flat throughout this period. This is largely due to federal and provincial measures aimed at increasing the energy efficiency of residential buildings (e.g., building code regulations and incentives/rebates for energy efficiency improvements).

| 2005 | 2010 | 2020 | |

| Emissions (Mt CO2e) | 42 | 41 | 43 |

| Households (Millions) | 12.1 | 13.0 | 14.74 |

Service Industry

Greenhouse gas emissions from Canada's service industry are expected to increase by 5 Mt from 2005 to 2020 to 48 Mt (Table 13), mainly as a result of expansion of commercial floor space. As in the residential sector, emissions growth in the commercial sector is significantly dampened by federal and provincial measures incorporated into this analysis, such as building code regulations, energy efficiency standards, and other programs.

| 2005 | 2010 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emissions (Mt CO2e) | 43 | 38 | 48 |

| Floor space (Millions m2) | 1106 | 1248 | 1552 |

Agriculture

The agriculture sector produces emissions of three greenhouse gases: carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide. Carbon dioxide emissions are released from fossil fuel combustion in farm machinery; methane emissions arise from livestock manure and ruminant animals; and nitrous oxide emissions arise from fertilizer usage, crops and manure and crop residue burning. Emissions from the agriculture sector are projected to decrease by 4 Mt from 69 Mt in 2010 to 65 Mt in 2020.

| 2005 | 2010 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture[16] | |||

| On-Farm Fuel Use | 9 | 13 | 10 |

| Crop Production | 19 | 22 | 22 |

| Animal Production | 39 | 33 | 33 |

| Total | 67 | 69 | 65 |

Waste and Others

This sector includes emissions from waste management as well as from non-emissions-intensive industrial sectors. Emissions from this sector are projected to grow moderately, leading to emissions growth of 3 Mt between 2005 and 2020.

Emissions from waste management arise from three sources: emissions from the decomposition of solid waste in landfill sites, emissions from wastewater treatment and incineration of waste. These emissions represent 6% of total GHG emissions in 2010. For these emissions, population and households are the main drivers. Provincial measures aimed at recycling and emissions capture from landfill sites are projected to help keep emissions growth below the growth in population and household formation. Emissions from waste are projected to remain stable.

Emissions from other industrial sectors represent a wide variety of operations and include construction, forestry as well as light-manufacturing facilities (e.g. food and beverage, and electronics) and coal production. These industries are projected to grow moderately, leading to emissions growth of 2 Mt between 2005 and 2020.

| 2005 | 2010 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waste & Others | |||

| Waste | 22 | 22 | 23 |

| Coal Production | 2 | 5 | 3 |

| Light Manufacturing, Construction & Forest Resources | 23 | 23 | 25 |

| Total Waste and Others | 48 | 50 | 51 |

Emissions by Province

Emissions vary significantly by province, driven by diversity in population size, economic activities, and resource base among other factors. For example, provinces where the economy is oriented more toward resource extraction have more uncertainty around the timing of large projects and will tend to have higher emission levels whereas more manufacturing or service-based economies tend to have lower emissions levels. Electricity generation sources also vary, with provinces that rely on fossil fuels for their electricity generation having higher emissions than provinces that rely more on hydroelectricity. Table 16 shows the provincial/territorial distribution of emissions in absolute terms as well as their per capita emissions.

The provinces oriented toward resources extraction and/or are highly reliant on fossil fuels for their electricity generation (i.e., Alberta, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia) have per capita emissions above the national average. The provinces oriented toward manufacturing or services or are highly reliant on hydroelectricity or less emission intensive sources for their electricity generation (i.e., Quebec, British Columbia, Ontario, Newfoundland and Labrador and Manitoba) have per capita emissions below the national average.

| GHG Emissions (Mt CO2e) | Per Capita Emissions (t/capita) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2010 | 2005 | 2010 | |

| British Columbia | 63 | 56 | 15.0 | 12.4 |

| Alberta | 232 | 236 | 69.8 | 63.4 |

| Saskatchewan | 71 | 73 | 71.1 | 69.8 |

| Manitoba | 21 | 20 | 17.9 | 16.3 |

| Ontario | 206 | 172 | 16.4 | 13.0 |

| Quebec | 86 | 82 | 11.4 | 10.4 |

| New Brunswick | 22 | 18 | 29.8 | 24.5 |

| Nova Scotia | 24 | 20 | 25.3 | 21.7 |

| Newfoundland | 10 | 9 | 19.8 | 16.9 |

| Prince Edward Island | 2 | 2 | 16.2 | 13.8 |

| Territories | 2 | 2 | 21.9 | 18.8 |

| Canada | 740 | 692 | 22.9 | 20.3 |

Table 17 displays projected provincial and territorial greenhouse gas emissions from 2005 to 2020. The projected emissions reflect a diversity of economic factors and government measures to reduce GHG emissions. These include public education campaigns, energy efficiency and renewable electricity programs, greening government operations carbon taxes or levies (i.e., British Columbia, Alberta and Quebec), regulatory measures, and legislated renewable electricity targets[17].

It should be noted that the increase in emissions in British Columbia and Alberta are driven by large natural resource projects; oil sands in the case of Alberta and natural gas in the case of British Columbia. For the most part, the oil and natural gas production projections reflect the views of the National Energy Board outlook for projects in these provinces, but there is an intrinsic level of uncertainty as to the timing of them that affects the projected GHG emissions[18]. The decline in emissions from 2005 to 2020 in Saskatchewan, Ontario, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia are due in large part to government measures related to coal-fired electricity.

| 2005 | 2010 | 2020 | Change 2005 to 2020 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 63 | 56 | 72 | 9 |

| Alberta | 231 | 237 | 285 | 53 |

| Saskatchewan | 71 | 73 | 64 | -7 |

| Manitoba | 21 | 20 | 21 | 0 |

| Ontario | 206 | 172 | 167 | -39 |

| Quebec | 86 | 82 | 85 | -1 |

| New Brunswick | 23 | 19 | 17 | -5 |

| Nova Scotia | 24 | 20 | 17 | -7 |

| Prince Edward Island | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Newfoundland | 10 | 9 | 10 | 0 |

| Territories | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| LULUCF | -25 | |||

| Canada | 740 | 692 | 720 | -20 |

Table 18 displays projected provincial and territorial per capita greenhouse gas emissions in 2020 and compares them to actual emissions in 2005 and 2010. Per capita emissions are projected to fall in all provinces in 2020, except for British Columbia and Alberta. British Columbia's per capita emissions are projected to increase due to the pace of natural gas development. Despite this increase, British Columbia's per capita emissions are projected to remain below the national average.

| 2005 | 2010 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 15.0 | 12.4 | 14.3 |

| Alberta | 69.8 | 63.4 | 63.6 |

| Saskatchewan | 71.1 | 69.8 | 54.7 |

| Manitoba | 17.9 | 16.3 | 15.1 |

| Ontario | 16.4 | 13.0 | 11.7 |

| Quebec | 11.4 | 10.4 | 10.0 |

| New Brunswick | 29.8 | 24.5 | 21.8 |

| Nova Scotia | 25.3 | 21.7 | 18.1 |

| Prince Edward Island | 16.2 | 13.8 | 12.3 |

| Newfoundland | 19.8 | 16.9 | 20.3 |

| Territories | 21.9 | 18.8 | 26.8 |

| Canada | 22.9 | 20.3 | 19.2 |

Importance of the LULUCF Sector

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has recognized the important role of the “land use, land-use change and forestry” (LULUCF) sector in addressing climate change. The LULUCF sector involves greenhouse gas (GHG) fluxes between the atmosphere and Canada's managed lands, as well as those associated with land-use change. Globally, land-use change was responsible for estimated net carbon flux to the atmosphere of about 1.47 GtC in 2005. In comparison, global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from fossil-fuel burning and cement manufacture emitted about 8.09 GtC in 2005[19].

Land management activities can either act as a carbon dioxide sink (i.e., remove CO2 from the atmosphere) or a GHG source (emit CO2 and other GHGs to the atmosphere). For example, afforestation, or planting trees on non-forest land, removes carbon from the atmosphere as the trees grow; but deforestation, or conversion of forest land to other land uses, will increase CO2 emissions due to decomposition or burning of the biomass.

LULUCF is a particularly important sector for Canada given that 10% of the world's forests are in Canada and our managed forest covers 229 million hectares, more than the managed forest of the entire European Union. Canada also has 47 million hectares of cropland.

Over the last two decades, important changes have occurred in land management practices in Canada that have reduced CO2 emissions or enhanced their removals from the atmosphere. For example, farmers have increasingly adopted no-till practices and reduced summer fallow practices, thereby increasing the rate of soil carbon sequestration. Best practices have also been adopted by the forestry sector, primarily as a result of provincial policies and/or regulations in their areas of jurisdiction.

Although these policies and regulations are aimed broadly at improving sustainability in the sector, they also reduce carbon emissions and increase sequestration. They include: relatively more reliance on tree planting as opposed to natural regeneration; more use of improved seed stock for tree planting; more and faster rehabilitation of harvest roads and landings; and adjustment in management practices to reduce soil compaction. Recently, economic factors have had a large impact on the forest sector which experienced a 43% decline in harvest levels between the peak year of 2004 and 2009, resulting in the lowest harvest since 1975[20].

Accounting for the LULUCF Sector

While GHG emissions from the LULUCF sector are included in Canada's annual National Inventory Report, the sector was left out of Canada's first national Emissions Trends report published in 2011, primarily as a result of technical challenges in forecasting emissions and removals from LULUCF and because accounting approaches for the sector had not yet been determined.

A unique challenge in forecasting LULUCF emissions resides in addressing the effects of natural disturbances (e.g. wildfires, insect infestations such as the mountain pine beetle), which can result in significant variations in the annual emission and removal estimates but are very difficult to project. The impact of natural disturbances also makes it difficult to discern the effects of improved management practices.

Environment Canada's National Inventory Report, which is used to measure current Canadian GHG emissions, currently includes estimates of emissions and removals with natural disturbances. The National Inventory Report is submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) on an annual basis.

The difficulties related to accounting for LULUCF emissions and removals are widely-recognized in the international community. In particular, challenges related to natural disturbances have been the subject of considerable technical work over the past several years. Acknowledging that natural disturbances are out of human control, it was finally agreed at the 2011 UNFCCC Climate Conference in Durban, South Africa, that the impacts of natural disturbances can be removed in accounting for forest management in 2013 and thereafter.

The UNFCCC guidelines for GHG inventory reporting were also updated in Durban to allow reporting estimates that better represent the direct effect of human activities, taking into account national circumstances. These new guidelines will come into effect for the 2015 National Inventory Report submission. Going forward, and on the basis of these new decisions, Canada will continue to explore options for revised reporting that provides a more accurate representation of emissions arising from human activities.

In a spring 2012 submission to the UNFCCC, Canada, along with a number of other countries, stated its intent to include the LULUCF sector in its accounting of GHG emissions towards its 2020 target, noting that emissions and related removals resulting from natural disturbances would be excluded from the accounting.

This 2012 Emissions Trends Report represents a key milestone for Canada in moving towards the inclusion of the LULUCF sector in projecting GHG emissions. While the estimates presented are preliminary in nature and will change as a result of ongoing efforts to improve data and methodology, as well as continued analysis of various approaches to accounting for LULUCF, they provide a solid first step toward understanding the underlying trends of LULUCF that will enable a policy discussion and the implementation of new measures to make further progress towards Canada's GHG reduction goals.

Subsector Analysis

Environment Canada, in partnership with Natural Resources Canada and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, has undertaken research and analysis over the past year to develop preliminary projections of LULUCF emissions and removals. Projected business-as-usual emissions and removals (i.e. in the absence of new policies that contribute to mitigation) have been estimated to 2020 for each of the following subsectors: forest management, cropland management, deforestation and afforestation[21]. Table 19 below shows preliminary results for each of the subsectors assessed.

| (In Mt of GHG emissions/removals) | 2020 Projected Emissions/ Removals | 2005 Estimate/ Reference Level | Expected Contribution to 2020 Emissions |

|---|---|---|---|

| * For forest management, a 2020 reference level is used for comparison (explained in further detail below). ** As a conservative estimate, the total is rounded down to 25 Mt, given that estimates are preliminary and will be revised as modeling methodology, accounting approaches and data are further refined. |

|||

| Forest Management | -148.7 | -122.6* | -26.1 |

| Cropland Management | -9.8 | -10.0 | +0.2 |

| Deforestation | +13.8 | +14.2 | -0.4 |

| Afforestation | -1.3 | -0.6 | -0.7 |

| Totals | -146 | -119 | ≈-25** |

Each subsector's contribution to Canada's 2020 emissions reduction target is estimated using an accounting approach that compares projected business-as-usual 2020 emissions/removals to 2005 emissions/removals, with the exception of forest management, where 2020 projected emissions/removals are compared to a 2020 reference level.

The rules agreed in Durban for LULUCF included a reference level for forest management, proposed by Canada, for the 2013 to 2020 period[22]. Canada's reference level is consistent with data in the National Inventory Report and was derived by assuming that future harvests in 2013 to 2020 would be the same as the average historical level between 1990 and 2009. As well, the reference level excluded all natural disturbance impacts after 2009, except a low background level expected to occur every year. As Canada's target is focused on the single year of 2020, the 2020 value used in constructing the reference level is used here. The reference level approach factors out highly variable natural disturbance impacts.

In Durban, parties agreed to LULUCF accounting rules for the Kyoto Protocol's second commitment period. Parties to the UNFCCC that will not take a second commitment period may follow these rules but are not bound to do so. The U.S., for example, in a submission to the UNFCCC in 2012, indicated it will include LULUCF when accounting for its 2020 target and that it will use a net-net approach for the LULUCF sector with a 2005 base-year. Canada's submission stated that LULUCF will be accounted for using either a 2005 base-year or a reference level.

Given this context, Canada's work to analyze alternative accounting approaches is ongoing, and adjustments to the accounting approach may be made in future Emissions Trends reports. In particular, alternative accounting approaches may need to be considered given that accounting approaches for LULUCF continue to vary internationally and there remains uncertainty with respect to future approaches under a proposed new climate change agreement beyond 2020.

Subsector Emission Trends and Methodologies

Further detail on Canadian emission trends and methodologies used are provided for each of the subsectors below:

- Forest Management[23]. As per Table 19, the Forest Management subsector dominates the expected LULUCF contribution in 2020, as a result of declining harvest rates. Harvesting is the human activity with the most impact on emissions in the managed forest. Harvest levels declined by 43% between the peak harvest year of 2004 and a 35-year low in 2009 before recovering somewhat in 2010. Current projections suggest that harvests will remain below the recent average historical level used in estimating the reference level. The projected value for the forest management sink in 2020 is derived by using projected harvests to 2020 and assuming no natural disturbances from 2010 onward except a low background level expected to occur every year, compared with the reference level.

- Cropland Management[24]. Due largely to the uptake of new farming practices (e.g. the increased adoption of no-till), soil carbon sequestration in Canada has increased over time from a rate of 1.5 Mt per year in 1990 to 1.3 Mt per year in 2010 (NIR, 2012). Currently, most of the land where no-till makes economic sense is already using this practice, so there is limited scope for increased uptake. Furthermore, the potential for land that has been in no-till for a long time (i.e. in excess of 20 years) to sequester more carbon decreases over time. Therefore, while soils will continue to sequester carbon (at a projected rate of 9.8 Mt in 2020), they will do so at a lower annual rate than in 2005 (when the rate was 10 Mt). Because accounting for emissions/removals for cropland management is on a net basis relative to 2005, this results in a small reduction in the overall LULUCF contribution in 2020. However, this does not indicate that a reversal of the stock of carbon in the soil has occurred.

- Deforestation/Afforestation[25]. Current deforestation rates in Canada are estimated at 44,000 hectares per year, down from 65,000 hectares per year in 1990. Part of the emissions due to deforestation occurs immediately upon the deforestation event, while the remaining emissions take place over subsequent years and decades. Deforestation emissions are projected to decline slightly to 2020 relative to 2005, whereas afforestation removals are expected to increase as a result of a slow increase in the area planted since 1990 and growth of the trees. The circumstances surrounding deforestation activities in Canada are extremely varied and involve a wide range of economic sectors (agriculture, urban expansion, resource extraction). As such, projections presented in this report will be adjusted as a result of revised projections of economic growth and conditions for each of these sectors.

Work is currently underway to also develop estimates for Peatland Management that will be added to next year's LULUCF estimates.

Contribution of the LULUCF Sector to 2020 Projected Emissions

On the basis of preliminary estimates, the projected contribution of the LULUCF sector to achieving the 2020 target is approximately 25 Mt. This estimated contribution, while illustrative of the potential, may change as subsector projections are refined over time as a result of further analysis, new data, updated projections, or adjusted accounting approaches.

As the Government of Canada works towards achieving its climate change objectives, it will consider, along with its provincial and territorial partners, policy actions to achieve further mitigation results from the LULUCF sector. Key LULUCF activities in Canada with potential for increasing mitigation benefits through reducing emissions or increasing removals include changing forest management practices, increasing afforestation, decreasing deforestation, enhancing agricultural practices that sequester carbon and possibly restoring managed peatlands. In addition to climate change mitigation, such efforts could positively impact other environmental or economic objectives. For example:

- Deforesting one hectare of forest emits on average approximately 300 tonnes of CO2e; policies aimed at reducing deforestation would have climate change benefits and could also address other environmental issues, such as biodiversity conservation.

- Increased adoption of farming practices such as no-till will also provide long-term benefits to farmers by improving soil quality and reducing erosion while increasing soil carbon sequestration.

- Mitigation practices such as increasing afforestation, reducing deforestation or restoring abandoned peatlands can also lead to creation and protection of wildlife refuges.

Emissions Intensity Improvements and Federal, Provincial and Territorial Actions

Last year, Canada's 2020 GHG emissions were projected to be 785 Mt in 2020. Since that time, there have been several key developments and GHG emissions are now projected to be 65 Mt lower at 720 Mt in 2020. This is despite the fact that GDP is projected to be slightly higher in 2020 in this year's projection. This reduction in GHG intensity implies a greater decoupling of emissions and economic growth.

As shown in Figure 4, while GDP growth is similar when compared with last year's report, emissions growth is slower. While GDP is expected to grow approximately 2.3% per year between 2010 and 2020, GHG emissions are only expected to grow 0.4% per year over the period. This leads to a total emissions intensity improvement of 14% over the period - an increase over the 13% improvement in last year's report.

In addition to the inclusion of reductions associated with LULUCF, there are a number of factors contributing to the increased emissions intensity improvement.

Figure 4 - Decoupling of GDP and GHG emissions - 2010 to 2020

First, this year's projections have a new, lower starting point as the most recent data show emissions were significantly lower in 2010 than previously estimated. Last year, emissions were estimated to be 710 Mt and since that time, preliminary data collected by Statistics Canada and assessed for the National Inventory Report put Canada's actual emissions in 2010 at 692 Mt. Contributing factors to this change were lower than expected natural gas production and slower growth in some emissions-intensive sectors.

Secondly, economic growth is projected to be slower in some emissions-intensive and light industry sectors. Projected sectoral shifts in the economy are contributing to the improvement in emissions intensity. Compared to last year's report, projected growth for the EITE sectors, specifically iron and steel and pulp and paper, is now lower, while it is now higher for the service industries which are less emissions intensive. GDP in Canada's services industry, where emissions intensity is low, increases as a share of the total. This reduces projected emissions in 2020, even though total GDP is projected to be slightly higher.

| 2011 Trends | 2012 Trends | Change from last year's report |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity | 1.7 | 1.9 | +0.2 |

| Oil and Gas | 2.5 | 2.6 | +0.1 |

| Emissions-Intensive Trade- Exposed Industries | 4.2 | 3.9 | -0.3 |

| Light Industry | 18.7 | 17.8 | -0.9 |

| Agriculture | 1.3 | 1.4 | +0.1 |

| Total Goods | 28.5 | 27.6 | -0.9 |

| Total Services | 71.5 | 72.4 | +0.9 |

Thirdly, progress is being made to reduce emissions. Supported by existing government measures, there is greater response from consumers and businesses to reduce emissions. Emissions are also declining with additional federal, provincial and territorial measures. In addition, additional federal emissions regulations for light-duty vehicles for the 2017-2025 period as well as heavy-duty vehicle regulations were included as well as recent provincial actions (e.g., Quebec's cap-and-trade, Nova Scotia's emissions cap for electric utilities, increased stringency of building energy codes, equipment standards and requirements for capturing methane from landfill gas). Additional details on these existing federal and provincial measures are provided in Annex 1.

More work is required to achieve the reductions required to meet the Canadian target. Work is underway that will lead to additional reductions. As the government advances additional measures under its climate change plan, future emission reductions will continue to accumulate, thereby pushing projected emissions in 2020 down towards the levels required to meet the 2020 target. For example, the Government of Canada is currently working in partnership with the oil and gas industry to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. Once the details of these measures have been announced and they are taken into account in the baseline scenario, projected emissions in 2020 will decline further below the projected levels shown here. Similarly, once additional measures in other sectors and additional provincial actions are announced and taken into account, projected emissions in 2020 will decline even further.

Key Economic Drivers and Assumptions

Many factors influence the future trends of Canada's greenhouse gas emissions. These key factors include the pace of foreign and domestic economic growth as well as its composition, population and household formation, energy prices (e.g., world oil price and the price of refined petroleum products, regional natural gas prices, and electricity prices), technological change, and policy decisions. Varying any of these assumptions could have a material impact on the emissions outlook.

In constructing the emissions projections, Environment Canada developed alternative views of changes in key drivers (e.g., world oil price, the pace of economic growth) that result in a range of plausible emissions growth trajectories. The baseline emissions projections scenario represents the mid-range of these variations, but remains conditional on the future path of the economy, world energy markets and government policy. The assumptions and key drivers are listed in this section. Alternative cases are explored in the sensitivity analysis in Annex 2 of the paper.

The emissions projections baseline scenario is designed to incorporate the best available information about economic growth as well as energy demand and supply into the future. The projections capture the impacts of future production of goods and services in Canada on greenhouse gas emissions.

Economic assumptions are based on the Government of Canada's short-term economic outlook contained in Finance Canada's Budget 2012 private sector economic survey. Long-term economic projections were developed using The Informetrica Macro-Economic Model(TIM) and are tuned to productivity growth projections and Statistics Canada's population growth projections. With respect to major energy supply project assumptions, Environment Canada typically adopts either the National Energy Board or Natural Resources Canada's view regarding the evolution of Canada's energy supply sector. For the emissions outlook in this report, forecasts of major energy supply projects are based on the National Energy Board's Fall 2011 Outlook, as their assumptions reflect their most recent views regarding the evolution of Canada's energy supply sector.

The projections also incorporate data from the National Inventory Report 1990-2010: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada, the National Energy Board, and the U.S. Energy Information Administration for the latest information on key parameters.

Economic Growth

Canadian real gross domestic product (GDP) in 2010 was an estimated $1,146 billion ($1997). This represents an average annual real GDP growth rate of about 2.4% over the twenty previous years.

The short-term economic outlook underlying the emissions reference case is grounded in the GDP growth forecast contained in Budget 2012. The Department of Finance regularly surveys private sector economic forecasters on their views on the outlook for the Canadian economy. The economic forecasts reported in this fiscal update, and which also form the basis of the department's fiscal forecasts, are based on a survey from March 2012 and includes the views of 14 private sector economic forecasters[26].

The Canadian economy is expected to show strong growth of about 3.1% per year to 2014. This growth is expected to continue at a slightly slower pace into the future, as annual rate of growth in real GDP decreases to approximately 1.8% in the period 2014 to 2020.

| 1990-2005 | 2005-2010 | 2010-2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gross Domestic Product | 2.8% | 1.2% | 2.3% |

| Industrial Gross Output | 2.8% | 0.8% | 2.3% |

| Real Disposable Personal Income | 1.6% | 4.2% | 2.4% |

| Consumer Price Index | 2.1% | 1.6% | 1.8% |

Gross output, which is a proxy for industrial production, is also projected to show significant growth. It is expected to increase by about 16% by 2015 and 26% by 2020, relative to 2010 levels.