Archived - Joint Audit and Evaluation of the Medical Devices Program 2013-14 to 2019-20

Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Introduction and Background

- 2.0 Safety, Effectiveness and Quality of Medical Devices in Canada

- 3.0 Providing Access to Medical Devices in Canada

- 4.0 Communicating with Stakeholders and Canadians

- 5.0 Program Organization and Governance

- 6.0 Program Resources

- 7.0 Conclusions and Recommendations

- Management Response and Action Plan

- Appendix A – Joint Engagement Scope and Methodology

- Appendix B - Internal Audit Summary

- Appendix C - Summary of Evaluation Findings

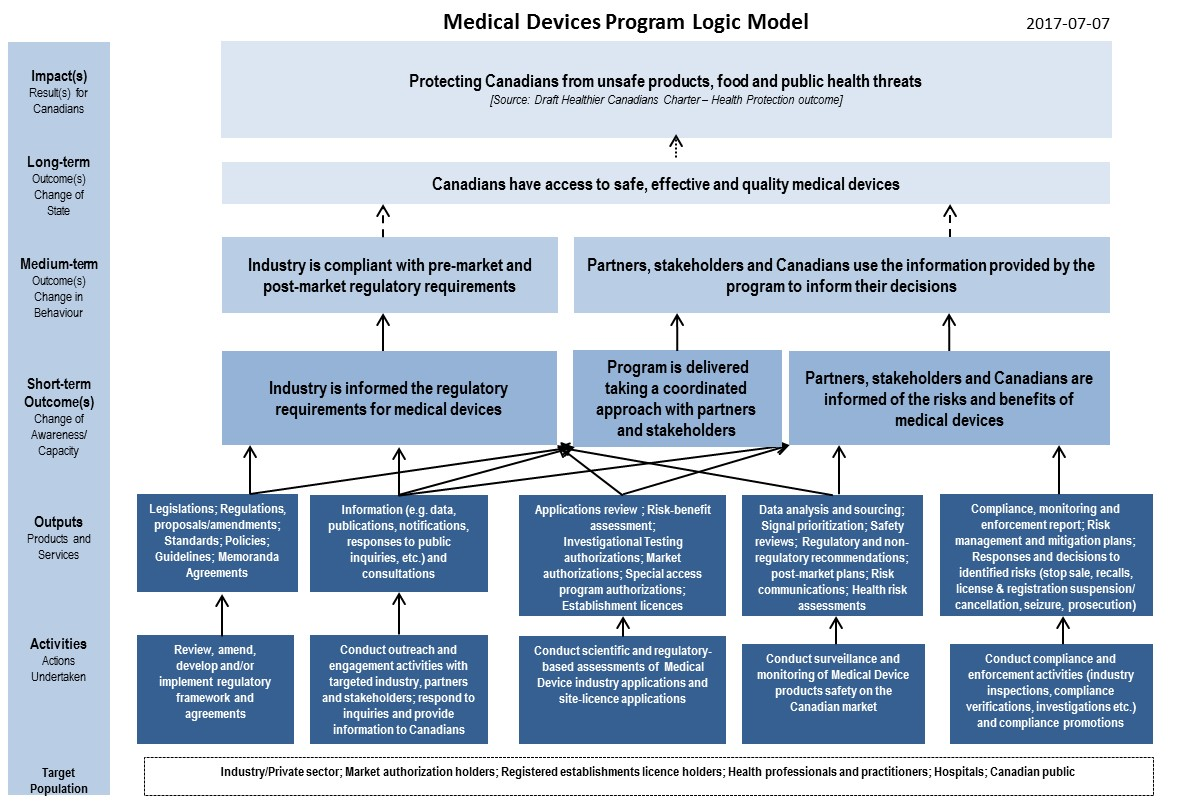

- Appendix D – Logic Model

- Appendix E – MDP Key Roles and Responsibilities at the Time of the Engagement

- Endnotes

List of figures

- Figure 1: Example of Health Canada’s Involvement in the Medical Device Life cycle

- Figure 2: Organizational structure of the Medical Devices Program at the time of the engagement

- Figure 3: Proportion of medical device incident reports entered within service standards

- Figure 4: Targeted risk communications were disseminated within service standards for 3 of 5 years

- Figure 5: Proportion of DEVICE licence applications in backlog

- Figure 6: Proportion of DEVICE licence applications that complied with regulatory requirements at first review and after additional information was requested and provided

- Figure 7: Organizational structure of the Medical Device Programs in the United States and Ireland

- Figure 8: Resources and workload of the medical devices and pharmaceutical surveillance functions (2015-16)

List of Acronyms

- CMDSNET

- Canadian Medical Devices Sentinel Network

- HPFB

- Health Products and Food Branch

- HPSEB

- Health Products Surveillance and Epidemiology Bureau

- IMDRF

- International Medical Device Regulators Forum

- IT

- Information Technology

- MDB

- Medical Devices Bureau

- MDCCD

- Medical Devices and Clinical Compliance Directorate

- MDCP

- Medical Device Compliance Program

- MDP

- Medical Devices Program

- MDSAP

- Medical Device Single Audit Program

- MHPD

- Marketed Health Products Directorate

- ROEB

- Regulatory Operations and Enforcement Branch

- RTOF

- Regulatory Transparency and Openness Framework

Executive Summary

This report presents findings from a Joint Audit and Evaluation of Health Canada’s Medical Devices Program (MDP). The engagement examined MDP’s activities from April 2013 to August 2019. The MDP aims to ensure that Canadians have access to safe, effective, and quality medical devices through:

- approval of establishment and medical device licences;

- surveillance of devices available in Canada;

- inspections of manufacturers, importers, and distributors; and

- communication to Canadians about risks related to devices.

In 2018-19, MDP planned expenditures were about $33M, $15M of which was funded by Health Canada. The remaining program funds were recovered through fees for regulatory services (e.g., licences to sell devices) Footnote 1 1.

Key Findings

Ensuring the Safety, Quality and Effectiveness of Medical Devices in Canada

The MDP had sufficient controls in place for its pre-market activities to ensure the safety, effectiveness, and quality of medical devices. It also completed most of its post-market activities within service standards.However, delays in processing medical device incident reports affected the Program’s ability to proactively detect such incidents. The MDP also experienced delays in completing the assessment of medical devices incidents.

While these challenges represent a risk for the Department, there is no evidence that they affected Health Canada’s ability to ensure the safety of medical devices. The Department was perceived as a trusted regulator by the majority of external key informants and available data suggests that the safety of medical devices in Canada was comparable to other countries.

The medical device environment is complex and evolving rapidly, with the development of novel devices using innovative technologies, such as digital technology, artificial intelligence, and 3D printing. Health Canada made significant strides to adapt its regulatory framework to remain effective at regulating such rapidly changing and complex devices. The Program also progressed in its efforts to integrate sex- and gender-based analysis considerations into the delivery of its activities. However, there was room to integrate these considerations more systematically across all program functions.

Providing Access to Medical Devices in Canada

The MDP made progress in balancing safety with access to medical devices. It processed the majority of device licence applications within services standards, but most of those applications did not meet regulatory requirements when initially submitted to Health Canada. This may have increased their processing time. The reasons why the majority of device licence applications did not meet program requirements when first submitted are not fully understood. Publicly available guidance documents outlining these requirements were difficult to find and were sometimes outdated. At the same time, the Program implemented various measures to improve the industry’s understanding of the regulatory process (e.g., an e-learning course) and aligned its requirements with those of other countries, in an effort to improve access to devices in Canada. It has also put in place various initiatives to streamline the access to medical devices, such as the Special Access Program, which allows health care professionals to gain access to medical devices that are not approved for sale in Canada for use in emergencies or when conventional therapies have failed, are unavailable, or are unsuitable to treat a patient.

Communicating with Stakeholders and Canadians

The MDP increased its engagement with stakeholders through meetings with industry representatives, discussions with health care professionals, targeted outreach to patient groups, and opportunities for stakeholders and Canadians to participate in online consultations. While these efforts were well received by industry, improvements are still required for Health Canada to become a go-to source of information for non-industry stakeholders and Canadians.

Program Organization and Governance

Various factors affected the Program’s ability to function efficiently. Roles and responsibilities across the pre-market and post-market surveillance and compliance and enforcement functions were not always clearly defined, particularly at the working level. However, the Program delineated clear roles and responsibilities among scientific evaluators and medical officers.

In addition, with the creation of the new Medical Devices Directorate, the roles and responsibilities between the merged pre and post market functions are intended to be further clarified through the development of revised operating procedures and processes. The Program is based on the Medical Devices Regulations which are based on the level of risk for various classes of medical devices. All the Medical Devices Program’s core activities centre on a risk-based approach for regulating medical devices through their life cycle.The MDP, however, did not have a comprehensive framework defining roles and responsibilities, nor an integrated risk management and information-sharing strategy. This lack of clarity regarding roles and responsibilities may have contributed to the development of parallel processes across MDP functions.

Additionally, the MDP’s information was stored across several repositories. Available information had to be consolidated from various sources in order to understand the full history of Health Canada activities in relation to a medical device.

Program Resources

A lack of resources challenged the post-market surveillance function’s ability to process incident reports and complete signal assessments within service standards. Overall, post-market surveillance activities received about only 7% of MDP’s budget in 2018-19. Additionally, in recent years, the number of staff working in medical device surveillance decreased. In comparison, the number of staff increased in the other two MDP functions.

With the introduction of mandatory incident reporting by hospitals in December 2019, the workload of the post-market surveillance function and the compliance and enforcement function may significantly increase. At the time of the engagement, the workload implications of mandatory reporting were not fully analyzed. However, it should be noted that recent investments have been made through various projects. This is expected to result in an increased intake of reports that are processed through new semi-automated systems. A risk still exists, as the challenges regarding the timely assessment and completion of some surveillance activities may be exacerbated if capacity issues are not addressed in these areas.

Recommendations

-

The Health Products and Food Branch should address current resource gaps in the post-market functions responsible for processing incident reports and assessing incidents. The Regulatory Operations and Enforcement Branch should consider the subsequent impacts on the resource needs of the compliance and enforcement function. As well, both Branches should ensure that the MDP has the capacity and tools to address the mandatory reporting by hospitals introduced in December 2019, and associated enforcement of hospital vigilance practices.

MDP’s surveillance activities were challenged by a lack of resources and could not always be completed within service standards. The introduction of mandatory reporting of medical device incidents by approximately 775 Canadian hospitals in December 2019 will likely further affect the post-market surveillance function’s ability to manage its workload, as the number of incident reports submitted to Health Canada may double. Mandatory reporting may also affect the resources and activities of the compliance and enforcement function, as inspectors will be required to monitor potential under-reporting and inspect hospitals. However, at the time of the engagement, Health Canada had not fully analyzed the implications of mandatory reporting on program workload.

-

The Health Products and Food Branch and the Regulatory Operations and Enforcement Branch should continue their efforts to adapt the MDP, through both domestic and international initiatives, to address challenges emerging from the rapidly changing life cycle of medical devices and the use of novel technologies.

While Health Canada made significant strides to adapt its regulatory framework, other challenges need to be addressed to ensure that the MDP remains effective moving forward. For instance, at the time of the engagement, there was no mechanism to address the growing issue around medical devices offered through a subscription or service (e.g., online diagnostic tools), or to track individuals using implanted devices so they can be notified directly by Health Canada if there is an incident.

-

The Health Products and Food Branch and the Regulatory Operations and Enforcement Branch should consider and document how to further integrate sex- and gender-based analysis plus (SGBA+) into the life cycle of medical devices, including providing guidance to applicants and increasing awareness of MDP staff.

Evidence shows that men and women are affected differently by medical devices due to sex and gender disparities. While Health Canada progressed in its efforts to integrate sex and gender considerations into the MDP, there were additional opportunities to further integrate these considerations in all program activities, where relevant.

-

The Health Products and Food Branch and the Regulatory Operations and Enforcement Branch should maintain and scale up communication and engagement efforts with industry stakeholders, health care professionals and organizations, and patient groups. It is also recommended that the Health Product and Food Branch improve the timeliness and accessibility of program information available online. This includes ensuring that guidance documentation is reviewed and updated as required across all of the MDP's operations, including on the Government of Canada website.

Health Canada’s efforts to increase communication and engagement with stakeholders were well received by industry representatives. However, Health Canada was not a go-to source of information for health care representatives, patient groups, and the population in general. There was also a need to improve the timeliness and accessibility of information online. In particular, outdated guidance documents may have contributed to inaccuracies in application submissions for medical device licences. Also, industry key informants mentioned having difficulty finding the information and guidance required to support the development of their applications.

-

The Health Products and Food Branch and the Regulatory Operations and Enforcement Branch should ensure that roles and responsibilities at the operational level are clearly defined and distributed, and that program risks are identified and managed.

Roles and responsibilities of operational-level staff were not clearly defined across the three MDP functions. The MDP also did not have a comprehensive framework defining roles and responsibilities, nor an integrated risk management and information-sharing strategy. Challenges with roles and responsibilities may be addressed, in part, with the implementation of the new Medical Devices Directorate announced in late 2019, which will integrate the pre-market function and the function responsible for the assessments of medical device incidents. However, the compliance and enforcement function and the Health Products Surveillance and Epidemiology Bureau (i.e., the group responsible for processing medical device incident reports) will remain with their original directorates.

-

The Health Products and Food Branch and the Regulatory Operations and Enforcement Branch should ensure that a data management approach supports the monitoring of medical devices throughout their life cycle.

The MDP’s information was fragmented across several repositories. This challenged the Program’s efficiency and ability to take a life cycle approach to regulating and monitoring medical devices.

1.0 Introduction and Background

This report presents key findings and recommendations of the Joint Audit and evaluation of Health Canada’s Medical Devices Program (MDP). The engagement examined MDP’s activities from April, 2013 to August, 2019.

Areas examined include the adequacy of program controls, risk management, and the integration of sex- and gender-based analysis plus (SGBA+), as well as the MDP’s impacts, how it was positioned to adapt to an increasingly complex environment, and how the organizational structure at the time of the engagementFootnote ii supported an efficient delivery of MDP’s activities.

Since March 2020, the Medical Devices Program has been focused on meeting the immense needs of health professionals, patients and industry in the fight against COVID-19. The central role of the Program in protecting the health and safety of Canadians has been placed in the spotlight, resulting in the fast tracking of a number of significant regulatory activities, including the drafting and implementation of various Interim Orders, all targeted at providing expedited access to COVID-19 medical devices (e.g., testing devices, ventilators, gloves) at this critical time. In addition, processes have been adapted to expedite the issuance of a significant increase of Medical Device Establishment Licences in order to ensure that critical personal protective equipment (PPE) is available to combat COVID-19. Lastly, the intake of incident reports, post-market monitoring, health risk assessments, and compliance and enforcement activities have required significant resources.

Although the finalization of the Office of Audit and Evaluation’s (OAE) report and Management Response Action Plan has been delayed due to COVID-19 priorities, the Program has continued to be mindful of the OAE’s recommendations. The pandemic has provided an opportunity to make progress in addressing some of these recommendations. Specifically, the Program has continued to engage domestic and international stakeholders in relation to COVID-19. Furthermore, the Program has been cognizant of historical challenges with the existing website when developing new content and webpages to share information in relation to COVID-19.

Data was collected from a review of the literature and program documents, performance measurement data and financial information as well as from case studies, a comparative analysis, and key informant interviews with MDP staff and stakeholders. Analyses undertaken also included the testing of a sample of operational transactions from April 1st 2018 to September 2019 (see Appendix A for further details).

1.1 Benefits and Risks of Medical Devices

Medical devices, as defined in the Food and Drugs ActFootnote 2 2, cover a wide range of medical instruments, apparatus, contrivance, or similar articles, as well as in vitro reagents used in the treatment, mitigation, diagnosis, or prevention of a disease, disorder, or abnormal physical condition. Without medical devices, many common medical procedures would not be possible, such as bandaging a sprained ankle, diagnosing infectious diseases, or implanting artificial hips.

The Medical Devices Regulations Footnote 3 3 group medical devices into one of four risk classes: Class I represent the lowest risk (e.g.,

tongue depressors) and Class IV represents the highest risk (e.g., artificial heart valves).

1.3 million different types of medical devices are available for sale in Canada. These devices range from bandages, hospital beds, pacemakers, implants, and MRI machines, to smart watches.

Many Canadians are dependent on medical devices to improve their health and quality of life. In some cases, medical devices like pacemakers are also credited with saving lives. According to several external key informants who are using medical devices, having access to a device improved their health and allowed them to engage in everyday activities such as work, sports, and travel.

Medical devices also provide economic benefits for the health care system. For instance, interventional cardiology and the use of drug-secreting stents, instead of coronary bypass surgeries, was linked to substantial health system savings and improved cardiac disease management, which in turn enhanced patient outcomes, including reduced recovery times and increased capacity for managing cardiac diseaseFootnote 4 4. According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information Patient Cost Estimator, implanting a stent costs approximately $6,000, compared to $26,680 on average for coronary bypass surgeryFootnote 5 5. Additionally, a Diabetes Canada study found that specialized devices to treat diabetic foot ulcers can help prevent amputations, which could result in direct cost savings ranging from $48 to $75 million a year for the province of Ontario Footnote 6 6.

Although medical devices are valuable to Canadians and the health care system, they also involve a certain level of risk. Incidents can occur as a result of a device malfunction, application or user error, the inherent risk of a device, as well as the negative interaction between the device and another device or medical procedureFootnote 7 7. Such incidents may result in health issues or illnesses for the user, and in some cases death. For instance, in 2014, the Paradigm Insulin Pump was recalled by the manufacturer because inadvertent misuse could have resulted in the delivery of an insulin dose exceeding the amount intended by the user and potentially cause hypoglycaemiaFootnote 8 8.

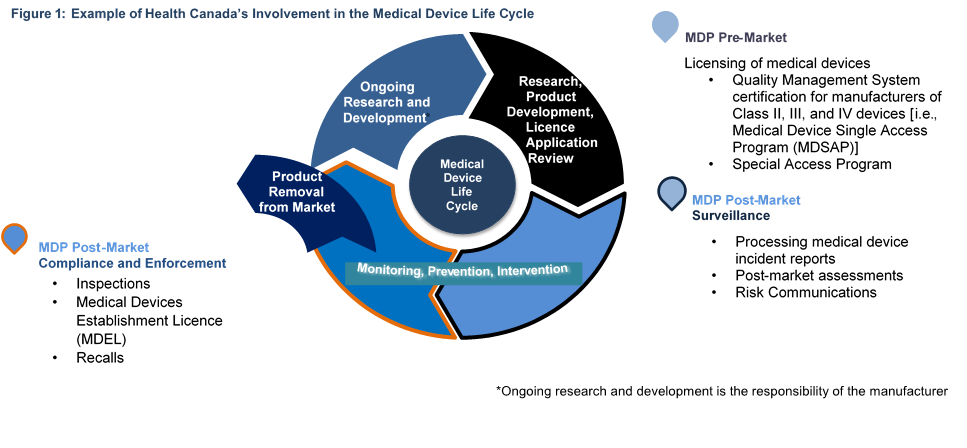

The MDP aims to mitigate the risks associated with medical devices by ensuring that Canadians have access to safe, effective, and quality devicesFootnote 9 9. The MDP’s activities cover the life cycle of a medical device, from providing regulatory guidance to manufacturers during their research and product development, through to the review of device licence applications, as well as monitoring, prevention, and intervention for devices that are licensed for sale in CanadaFootnote 10 10. The MDP's compliance and enforcement function also monitors the extent to which manufacturers, distributors, and importers are compliant with the Food and Drugs Act and Medical Devices Regulations. It delivers Medical Device Establishment Licences, conducts proactive inspections for manufacturers of Class I devices, and for importers and distributors of all medical devices, as well as responsive inspections of manufacturers, importers, and distributors of all classes of devices. Figure 1 below provides examples of some of the MDP’s activities that cover the various stages of the medical device life cycle. Of note, Health Canada does not licence Class I medical devices, but monitors them through the establishment licensing of manufacturers, importers, and distributors of medical devices in CanadaFootnote 11 11.

Figure 1 - Text description

This figure illustrates some of the Health Canada Medical Device Program functions and examples of activities to regulate the life cycle of medical devices. The figure is a 4-part circular model. Each section represents a particular part of the medical device life cycle. For each section, there is also an accompanying statement providing examples of activities of the Medical Device Program.

The first section of the life cycle model is labeled: Research, Product Development, Licence Application Review. The corresponding function is MDP Pre-Market Activities, with a bullet list of the following activities:

- Licensing of medical devices;

- Quality Management System certification for manufacturers of Class II and IV devices (i.e. Medical Device Single Access Program (MDSAP); and,

- Special Access Program.

The second and third sections of the model share the label: Monitoring, Prevention & Intervention. The second sections shows the MDP Post-Market Surveillance with the following examples of activities:

- Processing medical device incident reports;

- Post-market assessments; and,

- Risk Communications.

The third section shows the function: MDP Post-Market Compliance & Enforcement whit the following examples of activities:

- Inspections

- Medical Devices Establishment Licence (MDEL)

- Recalls

The third section of the model also has a smaller arrow labeled: Product Removal from Market. This arrows indicates that when a device reaches this point, it is no longer part of the model or the work of Health Canada.

The final section of the model is labeled: Ongoing Research & Development with a note indicating that ongoing research and development is the responsibility of the manufacturer. This section is included to show the entire life cycle of a medical device. It also points back to the first section of the model, which is MDP Pre-Market Activities

1.2 Health Canada’s Medical Devices Program

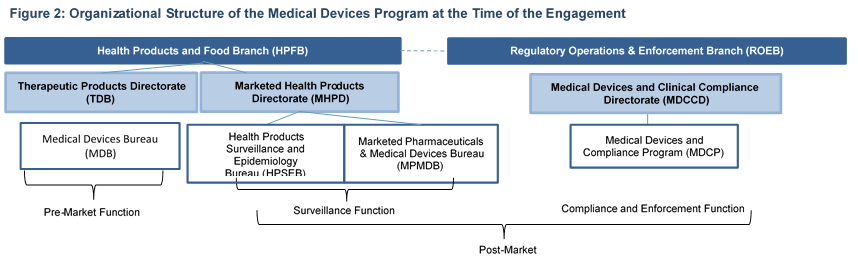

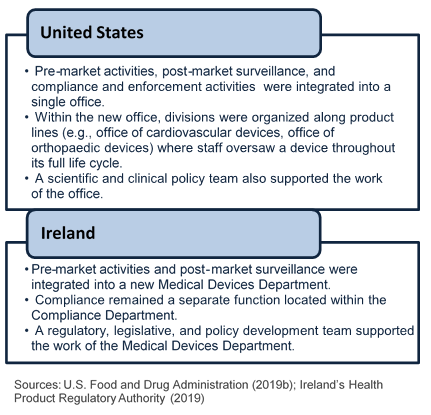

At the time of the engagement, the MDP was organized along separate pre-market (i.e., licence approval) and post-market functions (i.e., surveillance, as well as compliance and enforcement), each responsible for different program activities (see Figure 2).

As of November 2019, part of the Program was restructured into a new Medical Devices Directorate. This new directorate is comprised of the pre-market function and the Marketed Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Bureau, from the post-market surveillance function. The other half of the surveillance function (i.e., the Health Products Surveillance and Epidemiology Bureau) and the compliance and enforcement function remain with their original directoratesFootnote 12 12.

In 2018-19, MDP planned expenditures were about $33M, $15M of which was funded by Health Canada. The remaining expenditures were funded through the Program’s licensing fees.

Figure 2 - Text description

This figure illustrates the organizational structure within Health Canada that comprises the primary functions of the Medical Device Program.

Two Branches deliver program activities: the Health Products and Food Branch (HPFB) and the Regulatory Operations & Enforcement Branch (ROEB).

Under HPFB, the Therapeutic Products Directorate (TPD) and Marketed Health Products Directorate (MHPD) have different divisions involved in the program:

- Under the Therapeutic Products Directorate (TPD), the Medical Devices Bureau (MDB) is responsible for the pre-market function.

- Under the Marketed Health Products Directorate (MHPD), the Health Products Surveillance and Epidemiology Bureau (HPSEB) and Marketed Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Bureau (MPMDB) is responsible for the post-market surveillance function.

Under the Regulatory Operations & Enforcement Branch (ROEB), the Medical Devices and Clinical Compliance Directorate (MDCCD) has a division named the Medical Device Compliance Program (MDCP). This division delivers the compliance and enforcement function, which is also a post-market function.

Overall, at the time of the engagement, the MDP’s activities were similar in scope to other Health Canada regulatory programs (e.g., pharmaceuticals)Footnote 13 13. They were also aligned with the Department’s mandate and stewardship role of protecting Canadians and facilitating access to products that are vital to their health and well-beingFootnote 14 14.

The engagement focused on the three main functions of the MDP; however, it should be noted that program activities are supported by the Health Products and Food Branch’s Resource Management and Operations Directorate and Policy Planning and International Affairs Directorate, as well as the Regulatory Operations and Enforcement Branch’s Planning and Operations Directorate and Policy and Regulatory Strategies Directorate. Moreover, the Program’s risk communications are developed in collaboration with the Marketed Health Products Directorate’s Office of Policy, Risk Advisory and Advertising.

2.0 Safety, Effectiveness and Quality of Medical Devices in Canada

2.1 Pre-market Process Controls

The MDP implemented adequate controls within its pre-market function, and the majority of medical device licence applications were processed consistently. However, guidance documents available to staff were outdated, which could represent a risk, especially for new employees who are unfamiliar with the application process.

The pre-market function established controls and provided guidance documents to MDP staff outlining the intake, screening, evaluation, and approval of medical device license applications. Transactional testing shows that approximately 94% of device licence applications were processed by the pre-market function in accordance with all of the required controls. The processing errors observed in the remaining 6% of applications were minor deficiencies, including administrative errors, formatting inconsistencies, and partially completed internal documents.

Some of the controls implemented by the pre-market function included:

- For combination products (see definition below), the MDP developed a Combination Products Policy, as well as several standard operating procedures for reviewing device licence applications for these products. The majority of device licence applications for combination products received by Health Canada in 2017-18 and 2018-19 were processed consistently, in accordance with the MDP’s standard operating procedures. Because combination products involve more than one Health Canada directorate, consultations held between the directorates when reviewing license applications for these products, were recorded, and stored in a document repository named docuBridge.

- The MDP required all staff in the pre-market function to sign conflict of interest disclaimers when they were hired and on an annual basis. These disclaimers were tracked in an electronic database. Moreover, any contractors hired by the pre-market function to review applications had to answer an extensive list of questions on conflicts of interest related to their contracts. They were not assigned to applications in which they may have had a potential vested interest.

- The pre-market function also established a control mechanism consisting of issuing licences with conditions for certain Class III and IV devices. These conditions aim to address any safety or effectiveness concerns when additional information is required from manufacturers during the application process. These licences with conditions helped ensure that medical devices with potential safety and effectiveness concerns were monitored following license approval.

Key Definition: Combination products contain multiple different components, such as a drug and a medical device, or a biological component and a medical device. These types of products typically require joint reviews between the MDP and other programs or directorates within Health Canada (e.g., the Biologics and Genetic Therapies Directorate). The primary component of the product determined which program or directorate takes the lead on reviews.

Although the pre-market function implemented processes and controls that were followed almost all of the time, many of the function’s internal guidance documents that support the review process for device licence applications were significantly outdated. For instance, some of the guidance documents for intake and application administration did not reflect the MDP’s transition to docuBridge in 2017. This represents a risk as outdated information has the potential to mislead program staff when reviewing device licence applications. This risk is likely greater for newly hired staff who may be unfamiliar with undocumented processes.

2.2 Post-market process controls

The MDP experienced delays in processing mandatory incident reports. This represents a risk to the MDP’s ability to ensure the continued safety, effectiveness, and risk-benefit profile of medical devices.

The MDP detected, monitored and followed up on medical device incidents through the collection of:

- mandatory incident reports from manufacturers or importers;

- foreign incident reports from international regulatory agenciesFootnote 15 15;

- voluntary incident reports, through the Canadian Medical Devices Sentinel Network (CMDSNet)Footnote iiiiFootnote 16 16; and

- voluntary incident reports from other sources (e.g., private clinics, industry, individuals using a medical device)Footnote 17 17.

Once received, incident reports were manually processed by MDP staff.

In addition to receiving incident reports, the MDP also conducted active surveillance of incidents through literature and media scans, monitored actions taken by international regulatory agencies, followed-up with manufacturers to ensure reporting, and implemented compliance actions in cases of underreporting. It also had several working groups and committees, with representatives from each program function that were responsible for identifying and screening these incidents.

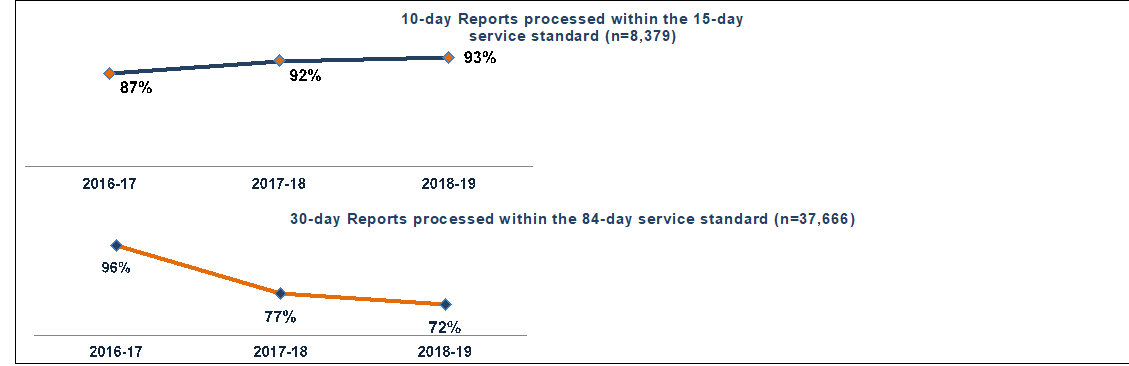

From 2013 to 2017, the MDP received between 11,070 and 14,931 incident reports per yearFootnote 1818. The majority were mandatory reports, for which there are two categories:

- “10-day reports”, meaning that the manufacturer has 10 days to report incidents that have led to the death or serious deterioration of an individual. The MDP received 1,814 of these reports on average per year between 2013 and 2017. The processing of 10-day reports was prioritized over other reports. MDP staff had to complete the data entry for these report within a 15-day service standard.

- “30-day reports”, meaning that the manufacturer has 30 days to report all other type of incidents. The MDP received 10,317 of these reports on average per year between 2013 and 2017. The service standard for the data entry of those reports was 84 daysFootnote 19 19.

An examination of reports by fiscal year showed that the entry of 10-day reports within service standards improved over the last few years, as illustrated in Figure 3Footnote iii iii. During the same period, the number of 30-day reports entered within service standards, decreased significantly. Additional testing showed that 10-day reports exceeded service standards by up to 319 and 30-day reports exceeded service standards by up to 370 days. This included delays of up to 153 days for high-risk Class IV devices.

Internal documentation suggests that the delays experienced at the beginning of fiscal year 2019-20 were attributed to the receipt

of approximately 1,600 incident reports from a manufacturer early in 2019. Such a situation can occur when the compliance and

enforcement function discovers that a manufacturer has under-reported incidents, and is then required to send all those reports

to Health Canada. According to a few internal key informants, at the time of the engagement, the surveillance function did not have the capacity to process such a large surge of reports within program service standards.

Figure 3 - Text description

This figure contains two separate line graphs. The first graph shows the proportion of 10-day reports processed within the 15-day service standard (n=8,379) over time:

- 87% in 2016-17

- 92% in 2017-18

- 93% 2018-19

The second graph is for 30-day reports processed within the 84-day service standard (n=37,666). The line graph shows the results by fiscal year starting in 2016-17 through 2018-19. The results are as follows:

- 96% in 2016-17:

- 77% in 2017-18:

- 72% in 2018-19:

The source of information for this graph is results from the audit transactional testing.

One control to ensure that 10-day reports were dealt with promptly was to verify that incidents were properly labelled as either a 10-day or 30-day report when submitted to Health Canada. However, at the time of the engagement, the triaging of reports was omitted from the intake process for medical device incidents. As a result, 10-day reports were miscategorized as 30-day reports when they were received by Health Canada, and remained in the processing queue for a longer period than would normally be expected for a 10-day report. This is a potential risk to the Canadian public, as emerging serious incidents may not be caught and addressed in a timely manner.

Some internal key informants explained that delays in completing the data entry for incident reports, lack of triaging incoming reports, and inconsistencies in the labelling of reports challenged the Program’s ability to conduct trend analysis, proactively address emerging and suspected safety issues, and conduct compliance and enforcement activities.

That being said, there were delays entering mandatory reports, as evidence shows that the voluntary reports received by the CMDSNet, which were considered to be at the same priority level as 10-day reports, were all entered within the required service standard (i.e., 15 days).

The MDP experienced delays in the completion of signal assessments, but most risk communications continued to be disseminated within service standards.

When an incident is signalled through reporting or monitoring, staff in the post-market surveillance function assess and review such signals in order to determine the right course of action to address the incident. MDP performance data shows that the majority of signal assessments and reviews were completed within the 130-day service standard for signal assessments and 60 days for reviews.

The proportion of these activities meeting service standards steadily declined from 100% in 2014-15 and 2015-16 to 89% in 2018-19. This downward trend continued in the first part of fiscal year 2019-20, as only 50% of signal assessments were completed within service standards between April and June, 2019. However, while operational data shows that service standards were met in the majority of cases before April 2019, they did not account for the time required to collect additional information about the incident from the manufacturer or other sources. If this time, excluding industry delays, is taken into consideration, approximately 30% of signals from fiscal year 2018-19 did met the required service standards.

Key Definitions

Signal Assessments aim to gather safety information on a priority issue in order to characterize it, come up with strategies to deal with it, and recommend solutions to prevent or mitigate identified risks.

Summary Safety Reviews provide information collected from monitoring licensed devices, based on several potential sources of information (e.g., domestic and foreign incident reports, medical and scientific literature) to identify potential safety issues. Each summary outlines what was assessed, what was found, and what action was taken by Health Canada, if any.

According to some internal key informants and program documents, activities pertaining to signal assessments were challenged by a lack of resources, including the redirection of staff towards other activities, such as addressing increased media attention regarding implanted devices and implementing the Medical Devices Action Plan.

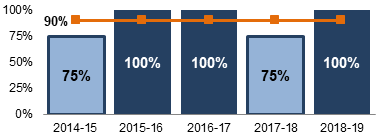

The delays in conducting signal assessment did not affect the MDP’s ability to issue risk communications (e.g., recalls, warnings and safety reviews) for devices that had an incidentFootnote 20 20. As shown in Figure 4, since 2014-15, most risk communications regarding medical devices were disseminated within service standards (i.e., 25 days for standard communications, 10 days for non-standard communications, five days for expedited communications, and two days for urgent communications).

Figure 4 - Text description

This figure is a vertical bar graph showing results by fiscal year from 2014-15 through 2018-19. A target line across the top of the bar graph provides a visual representation of how close results are to the target of 90% of risk communications disseminated within services standards. The following are the results:

- 75% in 2014-15

- 100% in 2015-16

- 100% in 2016-17

- 75% in 2017-18

- 100% in 2018-19

The source of information for this graph is MDP Performance Data.

Compliance and enforcement activities were conducted within service standards.

Program performance data shows that compliance and enforcement activities for medical devices were generally conducted within performance targets:

- The target of 95% of manufacturers inspected who were in compliance with the Food and Drug Act and related regulations was exceeded every year during the 2013-14 to 2018-19 period;

- In 2018-19, the proportion of high-risk cases initially identified as non-compliant, but that eventually resulted in compliance, met the target of 95%; and

- • The target of 100% of Medical Device Establishment Licences reviewed within the 120-day service standards was achieved twice between 2014-15 and 2018-19. In other years, the proportion of licences reviewed within these service standards was higher than 99%.

Key Definition: Medical Device Establishment Licences are issued to importers and distributors of medical devices in Canada, to manufacturers selling medical devices for which they are not the licence holder, as well as manufacturers of Class I devices who distribute their own devices.

Most post-market processes were documented, but there were gaps in the documentation of service standards. In addition, inconsistencies in data entry limited the Program’s ability to analyze trends from incident report data and proactively detect incidents.

The post-market surveillance and the compliance and enforcement functions documented the operating processes and assessment criteria for the prioritization of medical device incidents, in order to ensure that high-priority incidents (i.e., 10-day and CMDSNet reports) were examined promptly. However, the post-market surveillance function did not document its service standards in its internal guidance documents, and the compliance and enforcement function did not establish service standards for the voluntary reports it received. There was no comprehensive review done by the Program to determine if the timelines for data entry, assessment, and coding of incident reports had considered all current processes. In addition, the service standards for data entry have not been reviewed since they were adopted in 2010.

The engagement team expected to find that the processes followed by post-market functions would be reflected in the Program’s guidance documents. However, all the medical device incident reports examined in the Medical Devices System database were missing one or more pieces of the scientific evaluation information that was outlined in standard operation procedures and work instructions. This information was documented in external tracking sheets instead of the database. There were also inconsistencies in data entry for the Program’s Medical Devices System database that affected data integrity. For example, Special Access Program and investigational testing reports (see section 3 for a definition), which did not have a specific label in the database, were labelled as 10-day reports. This limited the ability to interpret statistical analyses of data extracted from the Medical Devices System.

2.3. Safety of Medical Devices Available in Canada

Despite challenges in accomplishing some post-market surveillance and compliance and enforcement activities on time, Health Canada was generally effective at ensuring the safety of medical devices in Canada.

The regulatory process was seen by several external key informants as rigorous because of the requirements to be addressed. These informant’s perceptions echo results from the 2016 Regulatory Transparency and Openness Framework (RTOF) survey, which included stakeholders and members of the public. Among stakeholderFootnote iv iv respondents involved with medical devices (n=20), the majority (95%) agreed that products regulated by Health Canada were safe. Additionally, the majority (75%) of members of the Canadian public with an interest in medical devices (n=40) were confident in the products regulated by Health CanadaFootnote v v.

Several external key informants perceived Health Canada as effective at ensuring the safety of medical devices. Moreover, some experts interviewed perceived the safety of medical devices sold in Canada to be comparable to other countries. Between 2013-14 and 2018-19, Health Canada issued approximately 900 recalls, on average, per year. In comparison, Australia, which received a similar number of Class II to IV licence applications per year (i.e., approximately 2,500 applications in 2017-18, compared to 2,100 in Canada), issued an average of approximately 600 recalls annually.

A comparison of recalls in Canada and the United States suggests that the safety of devices in Canada is similar to the United States. A sample of 60 recallsFootnote vi vi issued by Health Canada in 2018 was assessed to determine whether these recalls were also issued in the United States. If the recall was not issued in the United States, the team further examined whether the device subject to the Canadian recall was approved for sale by the United States Food and Drug Administration. The analysis shows that 70% (42 out of 60) of the recalls analyzed occurred in both countries. Of these:

- The time when the recall was initiated was comparable in both countries. Of the 42 recalls, 16 were initiated in the United States, 14 were initiated in Canada and 12 were initiated in both countries at the same timeFootnote vii vii.

- In most cases (30 out of 42 recalls), the recall was posted on Health Canada’s website before it was posted on the Food and Drug Administration’s website.

- The devices most frequently subject to recalls in both countries were in the diagnostic category (e.g., immunodiagnostic products) with 10 recalls, followed by surgical instruments with eight recalls, and imaging systems (e.g., ultrasound equipment) with seven recalls. Two of the recalls sampled and found in both countries were for implantable devices.

Of the 60 recalls analyzed, 18 were only issued in Canada. Of these:

- Most of the devices were approved for sale in the United States (15 out of 18).

- Three devices were not approved in the United States. These were subject to a recall in Canada due to a: 1) licensing issue, 2) labelling issue, and 3) a reminder from the manufacturer providing some technical information about the device.

- Certain recalls issued in Canada were not relevant for the United States. For instance, a recall pertained to a packaging issue for a certain lot of devices, or the French translation was missing from the product information.

- None of the 18 recalls issued only in Canada were due to a situation where there was a reasonable probability that the use of, or exposure to, the recalled device would cause serious adverse health consequences or death. In this regard, six out of the 18 recalls were in the Health Canada’s hazard classification II, which is related to a situation where the use of, or exposure to, a recalled device could cause temporary adverse health consequences, or where there is not a significant probability of serious adverse health consequences. The other 12 recalls were in the hazard classification III, which is related to a situation where the use of, or exposure to, a recalled device is not likely to cause any adverse health consequences.

- The recalls were primarily related to diagnostic devices (eight out of 18), and two were for implantable devices.

In addition to Canada’s comparability with the United States in terms of recalls, Health Canada was sometimes at the forefront internationally when issuing warnings and recalls. This was the case with the Essure Permanent Birth Control System. Canada was among the first countries to issue a Summary Safety Review and warning to health care professionals, advising them of potentially serious complications with this device. Canada was also one of the first countries to suspend the licence for Biocell breast implants.

Key Definition: Recalls include any action taken by a manufacturer, importer, or distributor of a device to recall or correct the device, or to notify users of its potential defectiveness.

2.4 Adapting to the Evolution of Medical Devices

The medical device environment is increasingly complex and driven by the use of novel technologies.

Ensuring the safety of medical devices is complicated by the fact that the medical device environment is increasingly complex, as novel devices are being developed using new and innovative technologies, such as digital health technology, artificial intelligence, and 3D printing. The life cycle of devices is becoming shorter as they are developed and updated more rapidly.

According to a few key informants and Health Canada documents, the pace of innovation challenged the Department’s regulatory framework, which had requirements and timelines built around traditional models of manufacturing, pre-market approval, and sales, among other thingsFootnote 21 21. For instance, during the period examined, there was a growing trend towards licensing software as a medical device (e.g., online diagnostic tools) and there was no mechanism in the current regulations to address this change.

With the Medical Devices Action Plan and the Regulatory Review of Drugs and Devices, Health Canada made progress in adapting to the changing environment.

During the engagement period, Health Canada implemented several initiatives and tools to adapt its approach to regulating and monitoring medical devices. Many of these initiatives were driven by the 2018 Medical Devices Action Plan and the 2017 Regulatory Review of Drugs and DevicesFootnote 22 22. These initiatives had concrete milestones and their progress was tracked by program staff. A detailed examination of the Medical Devices Action Plan tracking tool shows that its initiatives were generally on track or completed, and that progress updates were accurate and supported by evidence (e.g., publications).

Key Definitions

The 2018 Medical Devices Action Plan focuses on 1) improving how devices get on the market; 2) strengthening the monitoring and follow-up of devices once used by Canadians; and 3) providing more information to Canadians about medical devices.

The 2017 Regulatory Review of Drugs and Devices aims to provide more timely access to drugs and devices for Canadians through collaboration with other health care organizations (e.g., Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health).

As part of these initiatives, the MDP built internal expertise and expanded the use of outside experts and stakeholders to strengthen its competencies in key areas of growth for medical devices. This resulted in:

- The development and implementation of a Digital Health Division in 2018 to support a more targeted and comprehensive pre-market review of medical device licence applications related to digital health technologies;

- The creation of two new standing scientific advisory committees to obtain scientific, technical, and clinical advice on Digital Health Technologies (2018) and Health Products for Women (2019); and;

- The development of guidance documents on novel medical devices that use new and innovative technologies (e.g., 2019 guidance document on Supporting Evidence for Implantable Medical Devices Manufactured by 3D Printing ).

Health Canada also amended section 23 of the Food and Drugs Act in 2019 to increase the power of compliance inspectors. The amendment provided them with the ability to engage in more activities on the ground (i.e., testing, taking photographs and recordings) and to examine electronic data. The Department also implemented regulatory changes, including the mandatory reporting of medical device incidents by hospitals (see further details in section 6).

In addition, the Compliance and Enforcement Policy for Health Products (Policy 0001) was revised in December 2018. This revised version was perceived by a few internal key informants to be a more appropriate risk-based approach to enforcement, as it allows Health Canada to be more assertive in response to non-compliance. At the time of the engagement, the Department was also reviewing the scope and responsibilities of some of its compliance and enforcement activities to ensure that these activities focused on the right level of risk, and used resources effectively.

Additionally, Health Canada increased the number of annual foreign inspections to 90 (including 15 foreign on–site inspections) a year to help address challenges related to the globalization of the medical devices environment. This increase was expected to improve the compliance and enforcement of manufacturers in other counties, as well as promote international alignment and cooperation.

Engagement with international partners helps with sharing expertise and harmonizing practices.

Health Canada engaged in several international initiatives and partnerships to share expertise and harmonize practices, policies, and regulations with other jurisdictions. In particular, Health Canada was an active participant in the International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF). MDP staff participated in several working groups, including one dedicated to developing a harmonized terminology for reporting medical device incidents.

The MDP considered sex and gender differences, as they relate to medical devices.

Through the Health Portfolio Sex- and Gender-Based Analysis PolicyFootnote 23 23, Health Canada can integrate sex, gender, and diversity considerations into its programs, when appropriate, in an effort to better meet the needs of different patient groups. This is relevant for the MDP, as evidence shows that men and women are affected differently by medical devices due to sex and gender disparitiesFootnote 24 24.

In this context, the MDP implemented measures to account for these disparities in several of its activities. In addition to creating the Scientific Advisory Committee on Health Products for Women in 2019, the MDP proposed amendments to the Medical Devices Regulations to provide Health Canada with greater authority to require information from manufacturers when there is evidence of a problem, including identified risks or uncertainties for specific groups (e.g., women, people with disabilities, children)Footnote 25 25. Also, in 2013, the MDP published a guidance document, Considerations for Inclusion of Women in Clinical Trials and Analysis of Sex Differences , which outlined key considerations for including women in pre-market studies for therapeutic productFootnote 26. Health Canada also sponsored a research project that focused on applying a sex- and gender-based analysis lens to the medical device life cycle.

The pre-market function examined whether clinical studies data provided with medical device licence applications had considered specific population groups that might use the device. However, the MDP did not have structured guidance for the industry on when and how to include this information. Manufacturers were also not required to include this data in their device licence applications. As such, there was no available evidence that the MDP had conducted systematic data or trends analysis to provide information regarding sex and gender considerations related to medical devices.

While Health Canada made strides to adapt to a changing environment, some challenges remain to be addressed.

Several internal and external key informants noted that further progress was required to adapt the regulatory framework. For instance, there was no mechanism to address the growing issue of medical devices offered through a subscription or as a service (e.g., online diagnostic tools).

Although controls were in place within the compliance and enforcement function to inspect and mitigate risks, should an incident report be submitted for an unlicensed medical device, Health Canada did not have the means to directly contact individuals living with or using a medical device when there was a safety issue. The regulations required manufacturers to monitor the use of their devices, submit mandatory incident reports, and contact individuals when there was new information concerning device safety, effectiveness, or performance. However, there was a lack of clarity with respect to responsibilities for contacting individuals using devices that were no longer licensed in Canada, or that were sold by a manufacturer that did not have an active licence in Canada (e.g., their medical device licence was suspended or not renewed).

Some external key informants, including experts, health care professionals, and individuals using a medical device, felt there should be a central registry of individuals with an implantable device, in order to allow Health Canada to inform the individuals directly when there is an incident. A similar suggestion was also made by the Scientific Advisory Committee on Health Products for WomenFootnote 27 27.

Although there were ongoing mechanisms for collaboration with international regulatory agencies, some internal and international key informants noted that more could be done to communicate and collaborate with other jurisdictions. In particular, the compliance and enforcement function was often unable to engage in international collaboration due to workload pressures emerging from domestic priorities.

3.0 Providing Access to Medical Devices in Canada

3.1 Processing of Device Licence Applications

The MDP made progress in finding a balance between ensuring the safety of the devices and providing access in a timely manner.

Between 2013-14 and 2018-19, the MDP received an annual average of 1,499 new applications for Class II medical devices, 424 for Class III, and 78 for Class IV. During the same period, the Program also received an annual average of 1,382 Class II, 424 Class III, and 311 Class IV amendment applications.

During the period, the MDP improved its performance at providing decisions on medical device licence applications within service standards (i.e., 15 days for Class II licence applications, 60 days for Class III and 75 days for Class IV). Calculations undertaken for the study show that, between April 1, 2018 and June 30, 2019, almost all device licence applications (96%) were processed within service standards for all application types.

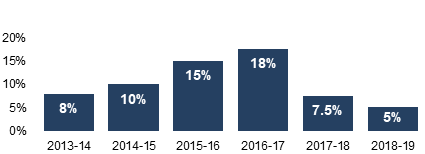

Additionally, according to program performance data, the MDP’s ability to process device licence applications within service standards improved over the engagement period. As illustrated in Figure 5, the backlog of applications was reduced for Class III and IV devices from a high of approximately 18% in 2016-17, to a low of 5% in 2018-19.

At the time of the engagement, the MDP’s service standards for reviewing device licence applications did not include the time required for administrative processing, nor for technical and regulatory screening of applications once received by Health Canada. They also did not account for the 45 days added to the review process once manufacturers respond to any requests for additional information.

Figure 5 - Text description

This figure is a vertical bar graph that shows the proportion of licence applications in backlog by fiscal year from 2013-14 through 2018-19. The following are the results shown:

- 8% in 2013-14

- 10% in 2014-15

- 15% in 2015-16

- 18% in 2016-17

- 7.5% in 2017-18

- 5% in 2018-19

Source of information for this graph are MDB Annual Report 2018-19 and MDB Annual Report 2013-14

Several health care professionals, as well as some industry representatives and experts, perceive the regulatory process to be lengthy. However, when compared to the United States, for instance, Health Canada’s service standards for reviewing device licence applications were shorter. The United States had a 180-day service standard for the scientific review of device licence applications with a possible extension for an additional 180 days if the application is amended (e.g., more information is provided) Footnote 28 28.

A significant proportion of device licence applications did not meet regulatory requirements when first submitted to Health Canada

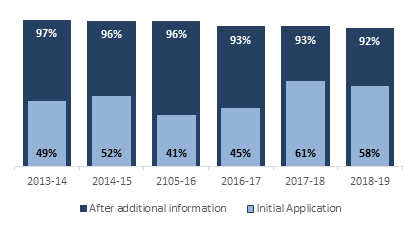

According to program performance data, from 2013-14 to 2018-19, between 39% and 59% of the device licence applications received by the MDP did not comply with regulatory requirements at the time of their first review decision. According to several internal and external key informants, incomplete device licence applications often increased the time required for the review process as program staff had to go back to the applicant to request additional information. Transactional testing demonstrates that 66% of device licence applications were the object of at least one additional information request or deficiency letter from the MDP to the applicant.

As shown Figure 6, once the applicant provided the additional information requested by Health Canada, the percentage of applications that remained non-compliant with regulatory requirements dropped to 8% or less between 2013-14 and 2018-19.

Figure 6 - Text description

This figure is an overlapping vertical bar graph showing results by fiscal year of both the proportion of initial licence application that comply with regulatory requirements at first review and the proportion of applications that became compliant after MDB requested and received additional information. The proportion of initial application that were compliant is as follows:

- 49% in 2013-14

- 52% in 2014-15

- 41% in 2015-16

- 45% in 2016-17

- 61% in 2017-18

- 58% in 2018-19

The proportion of applications that became compliant following the additional request and receipt of information is as follows:

- 97% in 2013-14

- 96% in 2014-15

- 96% in 2015-16

- 93% in 2016-17

- 93% in 2017-18

- 92% in 2018-19

Source of information for this graph is MDP Performance Data

Guidance documents on the application process were challenging to find and often not up-to-date.

The MDP published guidance documents on Health Canada’s website outlining requirements for all classes of medical devices, certain novel technologies (e.g., 3D printed devices), and combination products. These aimed to help applicants determine the classification of their product and navigate the application process.

The majority of industry key informants mentioned having difficulty finding the right information and guidance to support the development of their applications. They explained that navigating Health Canada’s website was difficult, and that the information available was not integrated in a way that helps industry understand the different steps of the application process (e.g., there is no roadmap to follow). Several industry and a few internal key informants explained that small and new manufacturers were more likely to experience challenges with the device licence application process, as they were less likely to be familiar with the regulatory process or had fewer resources with which to prepare their application materials. These perceptions align with results from the 2016 RTOF survey, where the majority of stakeholders (80%) reported that Health Canada’s information on regulatory requirements was not easy to find.

A review of guidance documents available online shows that, while the majority of guidance documents were drafted or updated within the last few years, a couple have not been updated in at least seven years. For instance, the document, Guidance on Supporting Evidence to be provided for New and Amended Licence Applications for Class III and Class IV Medical Devices, not including In Vitro Diagnostic Devices (IVDDs) , was last updated in 2012. Outdated documents may have contributed to inaccuracies in application submissions, leading to more back-and-forth between applicants and the program. This could also have affected the timeliness of device licensing decisions. There is also a risk that outdated internal guidance documentation may have caused confusion and errors when processing submissions, which could, in turn, have had impacts on the efficiency of pre-market processes.

Also, while broad information and evidence requirements for medical device licence applications were established for each class of device and available to industry stakeholders on Health Canada’s website, evidence of a defined process to periodically update these requirements was not found. This means that revisions to available guidance documents were made on an ad hoc basis.

3.2 Measures to Improve Access to Devices

The MDP’s Special Access Program provided a mechanism for Canadians to access medical devices.

According to program documents and a few external and internal key informants, challenges in accessing medical devices may also be mitigated through the MDP’s Special Access Program. This program allows health care professionals to gain access to medical devices that are not approved for sale in Canada, for use in emergencies or when conventional therapies have failed, are unavailable, or are unsuitable to treat a patient. Between 2013-14 and 2018-19, the MDP received an annual average of 4,714 applications through the Special Access Program, involving approximately 1,800 devices. On average, 95% of these applications were reviewed within the service standard of 72 hoursFootnote 29 29.

A few external and internal key informants raised concerns that accessing the Special Access Program could result in the circumvention of the full regulatory process. In this regard, the engagement team expected to find adequate controls in place to ensure that applications satisfied the criteria established by the Medical Devices Regulations, including the stipulation that manufacturers or importers must not use Special Access Program authorizations to circumvent regular licensing requirements.

The MDP implemented several controls to prevent the circumvention of licensing requirements. For example, in 2016, Health Canada published a guide informing health care professionals that the Special Access Program is not intended to provide early market access, and that manufacturers and importers are expected to pursue licensing for devices that were repeatedly authorized through the Special Access Program.

MDP staff also verified the credentials of health care professionals and restricted the number of units authorized per application. However, several controls implemented by the MDP relied on whistleblowing or self-disclosure (e.g., Health Canada prohibits applications completed by manufacturers or importers, and asks manufacturers or importers about their intentions to licence devices).

Transactional testing shows that approximately 80% of devices requested through the Special Access Program from 2013 to 2018 did not generate a subsequent device licence application. This proportion of devices also accounted for 73% of frequently-requested devices. A minority of applicants and devices accounted for the large majority of Special Access Program applications. This suggests that further incorporation of data analytics would strengthen Special Access Program controls for identifying possible attempts to circumvent regular licence requirements by facilitating the identification of risks, trends, and high-volume applications. In particular, data analytics may provide a supplemental control to help ensure that authorizations granted through the Special Access Program comply with the criteria established by the regulations, including identifying use of the Special Access Program to circumvent licensing regulations.

The MDP recently implemented several measures to mitigate challenges with the device licence application process.

In recent years, the MDP has focused on engaging with industry representatives to increase their awareness of available information and guidance documents regarding the medical device licence application process. The Program also developed and implemented several initiatives and tools in an attempt to reduce the number of applications that did not fulfill regulatory requirements, including:

- Pre-submission meetingswith industry stakeholders to discuss upcoming device licence applications. The impact of these meetings was unknown at the time of the engagement, as only a small number of industry representatives requested pre-submission meetings. The majority of industry key informants interviewed who participated in a pre-submission meeting found them to be helpful, particularly for new and novel technologies and devices;

- The launch of an e-Learning tool, Understanding how Medical Devices are Regulated in Canada – Premarket Regulation, to provide guidance on the regulatory requirements for new or amended device licence applications. While data was not collected on the reach of training, nor on feedback from participants, some industry and internal key informants noted that the course was well received; and

- The creation of the Digital Health Technology Division to facilitate the review process for devices involving new technologies. Some industry key informants recognized the Division’s efforts to facilitate and support the application process, including informational road shows and participation at industry conferences.

Harmonizing the MDP’s requirements with those of other countries can help improve access to devices .

According to program documents and interviews with several internal key informants, Health Canada was pursuing various initiatives to harmonize its requirements for medical device licence applications with those of other countries. Mainly organized through the International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF), these initiatives aimed to streamline the processes for manufacturers submitting applications in multiple jurisdictions. Examples include:

- A Table of Contents format to harmonize the format of device licence applications across IMDRF member countries. This format was perceived by a few internal key informants as a potential way to clarify the requirements of a medical device licence application. As of April 1 st, 2019 manufacturers can choose to use the Table of Content format for their Class III and IV licence applications; and

- As of January 1st, 2019, Canada implemented the Medical Device Single Audit Program (MDSAP) as a mandatory requirement for manufacturers submitting device licence applications to Health Canada. At the time of this engagement, Canada was the only IMDRF member to mandate the MDSAP. The United States and AustraliaFootnote 30 30 also accepted the MDSAP, but these countries did not implement it as a mandatory requirement.

Key Definition: The Medical Device Single Audit Program allows manufacturers to complete and submit one certificate of their Quality Management System in fulfillment of the regulatory requirements of multiple countries.

Concerns were raised by several industry key informants that the introduction of the MDSAP may have hindered access to certain medical devices. They explained that the increased costs for obtaining the MDSAP, as compared to the previous audit certification required by Health Canada, may have deterred some manufacturers from renewing their establishment licence, or from submitting device licence applications for new or amended medical devices. At the time of the engagement, it was too early to determine the impact of the MDSAP. According to program performance data, between July, 2018 and July, 2019, about 8% of the total medical device licences approved by Health Canada were cancelled, not renewed or discontinued, which was an increase compared to the annual average of 4% between July, 2013 and July, 2018 .

Transaction testing demonstrates that the MDP’s staff reviewed the certificates of manufacturers’ Quality Management System in a consistent manner when processing medical device licence applications. If deficiencies with the certificate were found during the application review, they were communicated to applicants via e-mail for Class II devices, or in a formal deficiency letter for Classes III and IV devices. However, there was a lack of integration between MDSAP audit report information and compliance and enforcement activities. Observations of post-market non-compliance were received by the pre-market function, but not flagged to the compliance and enforcement function for action, thereby limiting the Program’s ability to adopt a life cycle approach.

The MDP was exploring additional measures to further facilitate access to needed medical devices .

The MDP continued to explore measures to ensure both safety and access to medical devices in the midst of a changing environment. It is too early to assess the impacts of these measures, as they were still being implemented at the time of the engagement. These measures include:

- A regulatory pathway for advanced therapeutic products announced in Budget 2019. This proposed pathway is designed to support patient safety, while increasing the Program’s flexibility to approve novel devices that do not clearly align with the current regulatory framework; and

- The expansion of the Priority Pathway mechanism. This would allow the MDP to move certain device licence applications to the head of the queue for processing, in order to be more responsive to health care system needs and expand the agility of the regulatory system.

Key informants suggested potential opportunities for Health Canada to continue improving access to medical devices.

Several external key informants suggested examining the possibility of implementing an expedited process for approving amendment applications for medical devices that are already licensed for sale in the Canadian market, if the amendments are not expected to significantly increase the risks related to the device. This suggestion was made based on the expectation that the number of amendment applications would increase as the pace of technology continues to accelerate and updates to devices that are already licensed become more frequent (e.g., updates to software used as medical devices). A similar process for expediting amendment applications already exists in the United States [i.e., the 510(k)].

Some external key informants, including representatives from industry and health care, also suggested an expedited approval process for devices already approved for sale in countries that have regulatory processes similar to Canada. These informants further noted that, should Health Canada consider this option, it would also have to maintain its regulatory autonomy and its accountability to Canadians.

Additionally, some external key informants noted a desire for more transparency on the status of medical device licence applications submitted to Health Canada. This could be in line with the online ‘Submissions Under Review’ database for Health Canada’s pharmaceutical program. A similar desire was noted by the majority of respondents (76%) from the 2016 Health Products and Food Branch Transparency survey, who agreed that the Submissions Under Review list should be expanded to include medical devices.

4.0 Communicating with Stakeholders and Canadians

Health Canada improved its communications regarding medical devices and increased its engagement of stakeholders.

Health Canada disseminated a number of different types of communications products to help industry stakeholders navigate the Program, and help health care professionals and Canadians make informed decisions about the use of a device (e.g., Dear Health Care Professional Letter, recall notices). Communication products produced by the Department also included guidance documents (see section 3.3 for further details).

Over the last five years, Health Canada has improved its communications on medical devices through initiatives such as:

- Publishing Regulatory Decision Summaries for new and amended Class III and Class IV devices. Approximately 125 new summaries were published between March and August 2019;

- Increasing public access to medical device clinical data through a searchable web portal and to a regularly updated online database of medical device incidents, complaints, and recalls;

- Providing greater clarity and additional information on medical device inspections; and,

- Undertaking various engagement activities, including bi-annual meetings with key industry representatives, a webinar with health care professionals to discuss Health Canada's safety review of breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), and targeted outreach to patient groups, including meetings with women living with breast implants to learn about their experiences.

Key Definition: Regulatory Decision Summaries explain Health Canada's decision for certain health products seeking market authorization.

Several industry representatives and a few health care professionals recognized the MDP for its engagement initiatives. Industry representatives appreciated the opportunity to engage with Health Canada representatives and hoped these types of opportunities will continue in the future. These perceptions echo findings from the 2016 RTOF survey, where the majority of stakeholder respondents (85%) agreed that Health Canada did a better job at communicating to Canadians at that time than it did ten years ago. Additionally, all stakeholders who answered the survey felt that Health Canada was a trustworthy and reliable source of health and safety information, while 95% reported using Health Canada information to inform their activities and decisions.

In addition to various engagement initiatives, Health Canada offered stakeholders and Canadians the opportunity to participate in online consultations on proposed regulatory changes, as well as the development of new or amended policies and guidance documents. In 2017-18 and 2018-19, it completed 100% of its planned consultation projects on medical devices. While industry representatives were generally happy with the opportunity to participate in these consultations, a few noted that they would have appreciated more opportunities to follow up with the MDP after their participation. This would have allowed them to provide additional details, if required, and get a better understanding of how their feedback was used by the Program. In this regard, program documents show that the MDP reviewed feedback collected through online consultations and used it, where relevant.

To date, the majority of engagement and consultation efforts by the MDP were carried out by the pre-market function. As such, there remain opportunities to further engage stakeholders in discussions related to post-market activities. The compliance and enforcement function developed a stakeholder engagement plan, but were unable to fully implement it due to a lack of resources.

Non-industry key informants, including members of the Canadian public, had a limited awareness of Health Canada’s communications related to medical devices.

The majority of key informants who were health care professionals, patient associations, or individuals using a medical device stated that they were unaware of Health Canada’s communications products on medical devices. Those who were aware indicated that they rarely used this information to inform their decisions. They relied instead on other sources of information, including manufacturers, hospital procurement departments, medical journals and publications, media, as well as colleagues or other individuals using a medical device. Nevertheless, some health care professionals and several individuals using a medical device noted that they would prefer to have accessed information from Health Canada, as they expected it to be more objective and trustworthy.