Evaluation of the Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion 2016-17 to 2021-22

Download in PDF format

(1.04 MB, 38 pages)

Organization: Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2023-06-12

Final report

February 2023

Prepared by the Office of Audit and Evaluation

Health Canada

Table of contents

- List of acronyms

- Executive summary

- Program description

- Scope and evaluation questions

- Findings

- Efficiency and economy

- Conclusion

- Management Response and Action Plan

- Appendix 1 – Data Collection and Analysis Methods

- Appendix 2 – Variance between planned vs. actual spending – 2016-17 to 2021-22 ($M)

- Endnotes

List of acronyms

- HPFB

- Health Products and Food Branch

- ONPP

- Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion

- P/Ts

- Provinces and Territories

- SGBA

- Sex and Gender-Based Analysis

Executive summary

This report presents the findings of the evaluation of the Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion (ONPP). The purpose of the evaluation was to provide guidance and information to Health Canada by focusing on the relevance, performance, and efficiency of ONPP. The evaluation covered activities from the period of 2016-17 to 2021-22.

Program profile

Health Canada has provided national leadership in nutrition since the 1930s. Working collaboratively with federal partners, provinces, territories, and a range of other stakeholders, the Department develops and implements evidence-based policy that defines healthy eating and promotes environments that support Canadians in making nutritious food choices. ONPP leads this effort. It promotes and supports the nutritional health and well-being of Canadians by:

- providing public health nutrition leadership;

- anticipating and responding to public health nutrition issues;

- developing, promoting, and implementing evidence-based policies, initiatives, and standards;

- providing timely and authoritative nutrition information to support and influence decisions; and

- generating and disseminating nutrition-related knowledge.

What we found

Progress on results:

- Different barriers and external factors in the food environment affect healthy eating and the ability of many Canadians to adopt a healthy diet. For example, nearly 60% of Canadians have limited health literacy and have difficulty applying nutrition and health information to their lives.

- ONPP has made considerable efforts to mitigate this with, for example, the launch of Canada's food guide, by engaging Canadians, partners, and stakeholders, including Indigenous experts, to ensure that nutrition advice is relevant, accessible, and useful.

- Many partners and stakeholders work to help Canadians eat healthily, and to do so they rely on ONPP's resources in their day-to-day work, referencing the 2019 Canada's food guide on their websites, and integrating it into their respective policies, programs, and initiatives.

- Awareness and access to ONPP's nutrition and healthy eating products, namely Canada's food guide, is widespread among Canadians. While the food guide has been one of the most visited and downloaded health files on Canada.ca in the past three years, aside from COVID-19 related products, the impact on consumer behaviours is difficult to assess.

Challenges to effectiveness and efficiency:

- Collaboration with partners and stakeholders has not been consistent over the years.

- Internal capacity issues and external disruptions brought on by the pandemic have contributed to delays in the release of a few healthy eating information products. This has ultimately led to ONPP not meeting some interviewed stakeholders' expectations. Some jurisdictions have had to produce their own resources to supplement those provided by ONPP to address their specific needs.

- While ONPP has considered diversity and inclusion in the development of key resources, partners and stakeholders felt that more could be done to address the specific nutrition needs of particular groups such as seniors, different ethnic groups, and Indigenous groups (e.g., incorporating more traditional foods).

- Similarly, key data sources that are outside of ONPP's control contribute to gaps in Sex and Gender-Based Analysis Plus data, such as the irregularity and lack of timeliness in the collection of national data related to eating habits and other health related factors.

- Clarity on the different objectives, roles, and responsibilities between ONPP and the Food Directorate, who both deliver the Food and Nutrition Program within the Health Products and Food Branch would further support the delivery of key priorities, including addressing existing data gaps. The same would apply to other partnerships.

- Finally, while the program has articulated clear outcomes in their performance information profile, a few indicators could be improved with appropriate measurement strategies. In addition, clearly articulating how external factors can act as barriers to the program's desired outcomes could provide the appropriate context for such a complex area.

Recommendations

The findings from this evaluation have resulted in the following three recommendations.

Recommendation 1: Explore ways to address engagement issues.

Although engagement is a strength, a few projects would have benefited from the early involvement of key partners and stakeholders. Recognizing that the promotion of healthy eating is important, resources are scarce, and many other organizations could contribute, there is value in examining additional collaborations with key partners and stakeholders. This could include developing resources in collaboration with others. In addition, continuing to work collaboratively with partners and stakeholders will further support changes to the food environment and, to do so, not only should "traditional" partnerships be considered, but new ones as well (e.g., Indigenous organizations, food service providers in key settings).

Recommendation 2: Ensure that upcoming activities are reflective of the evolving food environment (e.g., COVID-19 related impacts on nutrition and healthy eating, inflation) and are undertaken with responsible groups (i.e., governance bodies and agreements), when appropriate.

The Healthy Eating Strategy and the ONPP strategic plan were developed and implemented before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and before recent food inflation. As ONPP continues to deliver on these strategies and plans' commitments, as well as its ongoing work, it should consider the current food environment and determine its impact on planned activities. To ensure that proper channels are used to undertake and oversee work to address the evolving food environment, it will be important to clarify long-standing roles (e.g., Food Directorate) by developing clear objectives, roles, and responsibilities via formal or informal governance bodies and agreements.

Recommendation 3: Improve performance measurement by:

- reassessing the current medium-term outcomes' related indicators; and

- articulating how external factors and barriers affect the achievement of outcomes and the impact of activities.

ONPP has a well-developed performance information profile with clearly articulated outcomes. They collect performance data and surveillance and monitoring data to assess activities that affect the food environment. However, limited performance information for some medium-term outcomes has made it challenging to assess the achievement of those outcomes. ONPP should consider developing or refining some of the indicators to include more systematic measurement strategies, as well as establishing an agreement with Statistics Canada to ensure the ongoing collection of relevant national data to help address some of the existing data gaps. Finally, clearly articulating how external factors affect Canadians' healthy eating decisions and can act as barriers to the achievement of ONPP's outcomes could provide an appropriate context for such a complex and multifaceted issue.

Program description

Background

Health Canada has provided national leadership in nutrition since the 1930s. Working collaboratively with federal partners, provinces and territories (P/Ts), and a range of other stakeholders, the Department develops and implements evidence-based policy that defines healthy eating and promotes environments that support Canadians in making nutritious food choices.

The Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion (ONPP) leads this effort. It promotes and supports the nutritional health and well-being of Canadians by:

- providing public health nutrition leadership;

- anticipating and responding to public health nutrition issues;

- developing, promoting and implementing evidence-based policies, initiatives and standards;

- providing timely and authoritative nutrition information to support and influence decisions; and

- generating and disseminating nutrition knowledge.

ONPP co-delivers the Food and Nutrition Program with the Food Directorate and both organizations are part of Health Canada's Health Products and Food Branch (HPFB). ONPP's current activities are guided by its strategic plan (2016-2021) and the Healthy Eating Strategy (2016), both aiming to increase healthy eating awareness, knowledge and food skills.

ONPP's recognized products include the following:

- Evidence-based dietary guidance and standards such as Canada's food guide and Evidence Review for Dietary Guidance;

- Resources and tools including the "Food Guide Snapshot" translated into 31 languages, recipes, and "Eat well. Live well." educational posters;

- Prenatal nutrition guidelines and infant feeding guidelines, nutrition facts table and related educational tools; and

- Information products related to restricting the exposure of unhealthy food and beverages marketing to kids.

Scope and evaluation questions

The purpose of the evaluation was to provide guidance and information to Health Canada by focusing on the relevance, performance, and efficiency of ONPP. The evaluation covered activities from 2016-17 to 2021-22.

The evaluation drew on evidence from multiple data collection methods including interviews, document and file review, literature review, and financial data review. For more information on methodology, refer to Appendix 1.

The following evaluation questions guided the evaluation:

Continued Need

- What are the current and emerging needs related to nutrition and healthy eating?

Effectiveness

- How successful has ONPP been in achieving the following outcomes?

- Engagement with partners, stakeholders, and Canadians.

- Canadians, partners, and stakeholders have access to timely, useful, and relevant information.

- Canadians have the knowledge and skills to make informed decisions pertaining to nutrition and healthy eating.

- Partners and stakeholders integrate nutrition and healthy eating considerations into their respective policies, programs, and initiatives.

- Canadians make healthy eating choices.

- Does ONPP deliver its mandate effectively to address current and emerging healthy eating issues?

Efficiency and Economy

- Are resources used efficiently and effectively?

Findings

Continued Need

What are the current and emerging needs related to nutrition and healthy eating?

Many current and emerging needs related to nutrition and healthy eating are linked to the food environment, including the availability of, and access to, nutritious foods, the impacts of social media and food marketing on consumption patterns, and rises in alcohol consumption and nutrition-related chronic illnesses.

With increasing and easy availability across multiple settings of highly processed food items that are high in calories, fat, sodium, and sugar, the current food environment makes it challenging for Canadians to choose nutritious foods. Not only are some nutritious foods more difficult to find, they can also be more expensive. Challenges with access and availability are particularly evident in northern and remote communities, as well as for some racialized and marginalized groups (e.g., newcomers to Canada, lower-income individuals, seniors) in rural and urban communities across Canada, according to internal documents. At the time of writing this report, food affordability is a topic highly covered in the media and top-of-mind for many Canadians as a result of inflation.

As consumers resort to a variety of sources for information on nutrition and its link with health, an increasing number of Canadians are relying on peers and social media for nutrition-related information. Nearly 60% of Canadians have limited health literacyFootnote 1 and experience difficulty in applying health information to their lives. Coupled with the risk of disinformation and misinformation spread on social media, there is an increasing need to provide clear messaging on nutrition. As well, billions of dollars are spent in direct-to-consumer marketing of foods, with nearly 80%Footnote 2 of all advertised food products contributing to excess sodium, free sugars or saturated fat. The effect of direct-to-consumer food marketing in influencing food preferences and consumption patterns is well documented.

Alcohol plays a related role as well. Recent studies suggest a need for additional awareness and education on the harms of alcohol. For example, data from the Survey on COVID-19 and Mental Health, collected from September to December 2020, was used to calculate that there was an increase of 15.7% in the prevalence of self-reported change in alcohol consumptionFootnote 3.

Canada ranks fourth among eighty countries in ultra-processed food consumptionFootnote 4, products that have low nutritional quality, are less satiating, and contribute to high-saturated fats, sugars, and sodium intake. Increased consumption of these products is associated with higher rates of obesity and chronic diseases. These conditions have a high impact on health care costs and life expectancy, as demonstrated by the following:

- Between 2000 and 2008, the annual economic burden of obesity in Canada increased by $735 million, from $3.9 to $4.6 billionFootnote 5. The annual economic burden of diabetes was estimated to be $3.8 billion in 2020, and is projected to be as much as $4.9 billion by 2030.

- Higher mortality rates can also be attributed to diet-related chronic diseases, with diabetes being known to reduce the lifespan by five to 15 years, as well as bringing complications associated with premature deathFootnote 6.

- The economic burden of not meeting dietary recommendations in Canada was estimated to be $13.8 billion in 2014, an amount similar in magnitude to the burden of smokingFootnote 7.

Effectiveness

How successful has ONPP been in achieving its outcomes?

ONPP values collaboration, and has taken many steps to ensure that Canadians, partners, and stakeholders are engaged. ONPP collaborates mostly by sharing information with others, and undertaking broad and thorough consultation on Canada's food guide. Similarly to what was reported in the 2015 evaluation of ONPP, some key products could have benefited from input from others.

As mentioned in the program description, ONPP collaborates with many partners and stakeholders to carry out its mandate. Engagement with partners and stakeholders, as well as Canadians, is key to ensuring that the guidance developed resonates, is relevant, and will be used.

The latest revision of Canada's food guide was highly collaborative and included consultations with multiple external partners, stakeholders, and the general public over a three-year period. As well, ONPP also engaged directly with health professionals, academic institutions, and academics to support healthy eating and promote the use of Canada's food guide.

As a result of criticisms from previous revisions to the food guide, and to limit influence of commercial interests, ONPP did not engage directly with the food and agriculture industry during the policy development of the guide. Some external stakeholders noted this was a step in the right direction to ensure that guidelines are evidence based and bias free. On the other hand, this change was also criticized by a few stakeholders such as P/Ts, another government department, and an external expert, who perceived that this resulted in less emphasis put on certain agricultural and agri-food products such as dairy and meat products. They felt this could lead to significant economic impacts on these food sectors, should Canadians decide to adopt the guidance.

The food guide's revision process included engagement with Indigenous academics, national Indigenous organizations, and Indigenous health professionals to integrate Indigenous considerations, and recognize the distinct nature and lived experienced of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.

ONPP also engaged with partners and stakeholders in the development and implementation of other initiatives. For instance, an extensive collaborative approach was also taken to the mandated priority of restricting the marketing of food and beverages to children, and ONPP engaged with researchers, external experts, and P/Ts in the development of a framework to monitor marketing to children.

Partners and stakeholders expressed their appreciation for ONPP's knowledge and expertise, their responsiveness to individual requests, and their openness to sharing information and providing regular updates. However, similar to what was noted in the 2015 evaluation, expectations of working collaboratively were not fully met according to some external interviewees. These interviewees felt that the lack of collaboration resulted in a few resources not meeting their needs and delayed their release. ONPP is aware of these stakeholder concerns and is working to address them.

Also, while recognizing ONPP's considerable engagement efforts with some Indigenous groups, some partners and stakeholders felt that upcoming consultations could be broadened by working with additional Indigenous leaders and organizations to reflect their unique needs (i.e., First Nations, Inuit, Métis). One external interviewee noted that, as part of the Government of Canada's truth and reconciliation commitments, the 2019 food guide had created a very important foundation to build upon by recognizing the impacts of colonialism and residential schools on nutrition. According to the interviewee, "the challenge is to develop a food guide for all Canadians that resonates with Indigenous peoples".

ONPP has increased access to healthy eating information that is relevant, useful, and somewhat timely. Some information products aimed at specific partners and stakeholders were not as timely, which may have limited their usefulness. ONPP provided greater access to its healthy eating and nutrition information by considering diversity and inclusion in the development of its products. The food guide was released prior to the recent rising cost of food due to inflation and does not currently acknowledge the growing issues of food availability and affordability in Canada.

Canada's food guide is a resource that is easily accessible: it is available online and through a web-based mobile application. ONPP has ensured access to the food guide by developing and disseminating many related products such as videos, recipes, social marketing campaigns, and a Canada's food guide monthly e-newsletter. In collaboration with the Communications and Public Affairs Branch, ONPP used various online channels (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram) to promote aspects of the food guide.

Canadians have accessed ONPP's products and platforms in great numbers, given that, for example, Canada's food guide is the most popular Health Canada product. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the food guide was the 17th most-common task visited by Canadians on the Government of Canada website. The Government of Canada website is task-based, meaning users come to it to complete a task, such as renewing a passport. The website makes a special effort to help users with the most frequently requested tasks, called top tasks. This is often easier to navigate because it addresses the user's goals. It is the third most visited Health Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada task, excluding COVID content, just behind recalls and product safety alerts, and travel advisories.

ONPP has modernized the appearance and delivery of the food guide to ensure that nutrition advice is relevant and useful. The input received through consultations has led ONPP to produce a food guide that is simpler to follow. It is less prescriptive, more flexible, and written in plainer language. The Canada's food guide plate tool helps Canadians to make healthy meals or snacks by allowing users to simulate adjusting their meals to follow the proportions of the Canada's food guide plate. One considerable change is that the guide combines two of the previous food groups of milk and alternatives and meat and alternatives into a single group called "protein foods". These changes having been made as a result of research and consultations. Some countries have adopted a similar shift for meats and alternatives, but that is not the case for milk and alternatives, which remain in those countries' food guides (e.g., Australia, England, the United States).

To ensure that its information is mindful of various contexts, the food guide acknowledges the food environment by highlighting healthy eating in various settings (home, school, work, and restaurants), the benefits of eating with others, eating less highly-processed foods, and taking the time to eat without distractions. Additional resources were also developed to provide advice on meal planning and making healthier choices, including information on the risks of drinking alcohol. The new food guide also demonstrated relevance by allowing more space for, and information on, cultural considerations (see section below for more information). All of these changes were noted and appreciated by partners and stakeholders.

Source: Canadian Community Health Survey, 2020; Canadian Community Health Survey, 2016

Figure A: Text description

The above diagram shows the general awareness Canadians have for the existence of a food guide. In 2020, 87% of respondents reported being aware of the resource, which is up two percentage points from 2016 (85%)Footnote 8. Another survey looked at Canadians' awareness of the food guide in 2020, and found that almost three quarters of the respondents reported being aware of a new versionFootnote 9.

In addition, in the past three years, aside from COVID and paid marketing traffic (i.e., traffic driven through paid ads), Canada's food guide including the food guide snapshot were the most visited and downloaded health files on the Government of Canada's website, excluding recalls and travel advisories that are tracked in separate systems. The guide and snapshot had 9.5 million visits over the past three years, which is more than content on cannabis (6.2 million), general non-COVID vaccinations (5.1 million), and opioids (4.2 million visits).

To enhance its reach, ONPP conducted numerous social marketing campaigns for variety of audiences. Over the past five years, social media posts related to healthy eating that also include Canada's food guide, have had a higher average of views per post than other campaigns related to cannabis or opioids (7,500 versus 6,500), as well as higher engagement rates (2.4% versus 1.7%). Table B provides some insight into ONPP's successful dissemination of nutrition knowledge over the past three fiscal years.

Diversity and inclusion and SGBA Plus considerations

ONPP integrated diversity and inclusion and SGBA Plus in the development of its information products. This includes translating the food guide snapshot into 29 additional languages, nine of which are Indigenous, and conducting an audit of the food guide web pages from a diversity and inclusion perspective. Web pages included guidance around nutritional needs and healthy eating habits for children, teenagers, and older adults; how cultures and food traditions can fit into healthy eating and recipes from a variety of cultures; and guidance to support healthy eating on a budget. ONPP is currently exploring with its partners how to gather disaggregated data to develop a better understanding of needs and how to address gaps.

| no data | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food guide (FG) snapshots accessed | 2,100,000 | 695,000 | 2,100,000 |

| Translated FG snapshots accessed | 65,000 | 57,000 | 150,900 |

| E-newsletter subscribers | 40,000 | 52,000 | 61,000 |

| Website visits | 4,500,000 | 2,900,000 | 2,900,000 |

| FG recipes accessed | 1,600,000 | 800,000 | 1,300,000 |

|

Note: numbers have been rounded up |

|||

ONPP also adapted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the lockdowns, ONPP added additional information to the Canada's food guide web page. These included how to make healthy eating and snacking as easy as possible, recommendations for meal planning and preparation, tips on shopping for nutritious foods with longer shelf lives, and how to eat consciously during stressful times.

Partners and stakeholders have access to information

Health and education professionals who subscribe to the Canada's food guide newsletters use its information as part of their work. According to internal ONPP documents, 93% of survey respondents, including consumers, were satisfied or very satisfied with the type of healthy eating information provided.

Although partners and stakeholders agreed they generally have access to the information they need, some noted that access to some information was not always timely. Despite having the expertise to adapt nutrition guidelines based on client-specific and unique needs, some of the stakeholders' expectations were not met. These include additional guidance to support nutrition programming and education for different life stages, identification of minimum portion sizes and amounts of foods to develop and adapt menus to specific settings, such as long-term care institutions, schools, and child care centres).

The lack of timely deliverables had an impact on service delivery and provision of advice by some partners and stakeholders:

- Additional dietary guidance for health professionals: As a result of receiving the Applying Canada's Dietary Guidelines three years after the launch of the new food guide, some stakeholders initially lacked the supplementary information they needed to correctly interpret the new food guide. Interviewees stated that they had to take on additional work to address gaps in the new food guide, particularly around meal planning for specific populations. For example, with milk featured in the protein group instead of its own category, some child care services misinterpreted the guidance and replaced milk with water on their menus. Similarly, the guidance contributed to some parents removing milk from their children's diet, since they believed it to no longer be featured in the food guide, as mentioned anecdotally by interviewees. While the Applying Canada's Dietary Guidelines were developed in 2021-22, some interviewees pointed out that more frequent communication and transparency on the status of the product may have helped manage expectations.

- Updating the 2014 infant feeding guidelines: A few stakeholders were concerned that ONPP had yet to update the infant feeding guidelines. A scan conducted by ONPP in 2021-22 demonstrated that, in some cases, there were some inconsistencies in the way the guidelines have been implemented. For example, in the absence of more current guidelines, some health services are now recommending more vitamin D than the 2014 guidelines (i.e., 400 to 800 international units daily, as opposed to Health Canada's recommendation of 400 international units daily recommendation). Internal interviewees acknowledged that the infant feeding guidelines were not updated as originally planned and confirmed that it was due to lack of resources. They are currently reviewing the evidence base.

ONPP works to ensure Canadians have the knowledge and skills to make informed decisions pertaining to nutrition and healthy eating. It does not systematically track Canadians' knowledge and skills. While Canadians access, and are aware of, Canada's food guide and other key resources, it is unclear whether knowledge and skills were gained and whether that resulted in healthy eating decisions.

As outlined earlier in the report, many external factors have an impact on individual food choices. ONPP's activities to promote nutritious food environments included promoting the uptake of the food guide in key settings and restricting the marketing of foods and beverages to children. This includes an initiative that aims to support changes in the food environment by creating principles and resources to assist publicly funded institutions to promote healthier options and limiting the availability of highly-processed foods and beverages.

While the program does not have an indicator to measure the knowledge and skills of Canadians, many studies have looked at aspects of Canadians' awareness and their use of Health Canada guidance. In general, Canadians are aware of the food guide and accompanying resources. However, while studies and internal documents report that Canadians believe the food guide is an important document that influences food-related behaviours, and they use it to assess the quality of foods, choose foods, or plan meals, it may not always translate in their ability to make appropriate food choices. In fact, 30% were more likely to turn to family or friends or conduct their own research for healthy eating adviceFootnote 10.

Health literacy has been increasingly recognized as an important influence on eating patterns. Health literacy is defined as the ability to read, understand, and act upon health information. A few studies demonstrate that the majority of Canadians are aware of Health Canada's guidance and appear to have some skill when it comes to reading nutrition-related information on food labels. However, this knowledge remains somewhat limited. In some cases, evidence points to younger Canadians (18-34 years old) lacking clarity on how to eat nutritious foods, including parents of very young children. Based on this information, ONPP has developed online resources dedicated to helping parents shape their children's' eating habitsFootnote 11.

There is limited reliable and recent performance measurement data on the uptake of ONPP's information products. Although partners and stakeholders confirmed the importance and reliance on ONPP's national dietary guidance, some initial challenges were noted with the adaptation of the guidance in various settings and population needs. More recent evidence, however, shows integration of the food guide by the majority of P/T health authorities, health professional organizations and academic institutions across the country. Strong evidence of uptake was also noted given the increase of copyright requests of the food guide.

Partners and stakeholders recognize ONPP as the leader and national authority for dietary guidance that provides the basis for healthy eating guidelines. They also recognize that their respective policies, programs, and initiatives should be based on ONPP's guidance.

There is limited recent and reliable performance measurement data available on the extent to which partners and stakeholders have integrated ONPP's policies and resources into their own, an area that ONPP is looking into, as the latest data is based on a 2012 survey. As integration and uptake of new evidence can take years, it is too early to determine the full extent to which ONPP resources have been fully integrated. Partners and stakeholders were well informed by ONPP regarding nutrition and healthy eating policies, strategies, and initiatives; however, the majority of interviewees mentioned not being able to integrate some of the recent guidance, at least in the first years after the launch of the new food guide, because:

- More specific guidance was needed, such as portion sizes and quantities that could be adapted to various settings (e.g., long-term care) and population needs (e.g., clear guidance on dairy product consumption for children) to help policy and program development and implementation (e.g., menu development).

- Guidance had to be adapted to include more culturally relevant aspects that would meet the diverse needs of certain population groups, such as Indigenous peoples (e.g., incorporating more traditional foods, adjusting examples of foods to ones that are available locally). In addition, recommended foods like nuts and seeds or fruit may not be easily available in some parts of the country, or may be unaffordable.

However, the evaluation was able to find solid evidence of uptake and integration of ONPP's policies and resources through other means. One example is the copyright request data collected by Health Canada, which showed an average of 108 requests received per year in the past four fiscal years:

- At its peak in 2018-19, there were 156 total copyright requests processed by ONPP. This number slightly decreased to 115 in 2019-20 and then to 75 requests in 2020-21 and 86 in 2021-22.

- Some of these requests varied from requests to update imaging in textbooks for nursing students to developing resources for clients with chronic health conditions.

There is also documented evidence of partners and stakeholders referring to the food guide in their own resources. The majority of P/T health authorities reference the 2019 Canada's food guide on their websites (i.e., links to the Government of Canada webpage). The only jurisdiction that did not reference the food guide is Nunavut. Furthermore, the majority of key nutrition and food stakeholders, from health care professional organizations to agri-food industry associations, have promoted the use of the new food guide in their public-facing material. Multiple organizations refer to the food guide, with universities that teach nutrition programs going so far as to mention that they use it for their on-campus meal planning, while some groups (e.g., Dairy Farmers of Canada) have developed educational material for middle schools based on the new food guide's recommendations.

Here are a few examples of the new food guide being used by different types of organizations:

- Some organizations working to reduce the burden of diet related illness link the new Canada's food guide on their websites and promote it as a resource for healthy eating and a healthy lifestyle.

- Some health care and allied services professionals provide links to the new food guide.

- For universities offering nutrition programs:

- All adopted the new food guide within their coursework.

- More than half refer to the food guide as a source of nutritional information for healthy campus living.

- More than half provide links to the webpage.

- Some mention adopting the food guide for campus menu planning.

- For agriculture and agri-food industry organizations:

- Many provided a link to the food guide on their websites while some developed resources based on the food guide's recommendations.

- Some mention the new food guide's impact on the industry in a few articles.

Finally, the evaluation also found many references to Canada's food guide in peer-reviewed journals. From 2016 to 2021 approximately 600 articles mentioned the food guide. It is worth noting that a reference to new guidance documents, such as the food guide, in scientific journals can take three to five years to occur. In the current climate, the pandemic may have prolonged some of these processes; however, the numbers collected so far demonstrate the importance of this resource to increasing the knowledge base in the field of health, nutrition and healthy eating.

Canadians make healthy eating choices: External factors, such as the pandemic and the food environment, play a significant role in the eating behaviours of Canadians. A little less than half the population is using ONPP's dietary guidance and only one quarter of the population is consuming the recommended daily servings of fruits and vegetables. Although ONPP does not have financial levers in place to help incentivize behaviour change, it has collaborated with the right partners that do – demonstrating their commitment to achieving their objectives.

As mentioned earlier in the report, Canadians have accessed ONPP's resources, are aware of the food guide, and have some knowledge and skills regarding healthy eating. Regardless, Canadians still make unhealthy decisions on nutrition. ONPP tracks Canadians' healthy eating choices through two key performance indicators: the percentage of Canadians who use dietary guidance, and the percentage of Canadians who report eating fruits and vegetables five or more times per day. Results have been collected on an ad hoc basis between 2016 and 2022, rather than on a regular schedule. As shown in Table A, data reported in 2021-22 shows a slight decline from previous years in the percentage of Canadians who use dietary guidance provided by Health Canada. Similarly, there has been a decline in the consumption of fruits and vegetables, with data slightly below the established targets of 30%. Of note, the target for fruit and vegetable consumption is the indicator used by Canada in the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals to support the broader indicator of "Canadians adopt healthy behaviours".

| Year | % of Canadians who use dietary guidance provided by Health Canada | % of Canadians who report eating fruits and vegetables 5 or more times per day | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Result | Target | Result | |

| 2016-17 | ≥40% | 40.7% | N/A | 30% |

| 2017-18 | ≥50% | 46.5% | 30% | 28.6% |

| 2021-22 | ≥50% | 44.3% | 30% | 25.4% |

|

Source: Results InfoBase |

||||

However, as seen in the evidence presented in this report, there are many Canadians who have an interest in Health Canada guidance and who use ONPP's information. For instance, out of 54,795 subscribers to the food guide e-newsletter, 83% mentioned using the food guide's recommended dietary guidance for personal use and asked for more recipes. This number is relevant to the time when the evaluation was conducted, which is different from what was reported later in program highlight documents.

Canadians intend to make nutritious food choices, but convenience is a key factorFootnote 12. One survey carried out from 2018 to 2020Footnote 13 shows marginal improvements in the consumption of nutritious foods, with a small increase in processed food consumption in 2020, as compared to previous years. This aligns with a Statistics Canada study noting that, even during the pandemic lockdown measures, although meals were more frequently prepared at home, some of these were made from ultra-processed and packaged products with high amounts of fat, free sugars, and sodium. The result was that some home-prepared meals were just as unhealthy as "take out" mealsFootnote 14. Furthermore, while some research suggested that a third of Canadians had made healthier choices during the pandemic, other research found increased consumption of "take out food", a trend that had been steadily increasing a few years before the pandemic.Footnote 15

Another issue to consider is access to and availability of nutritious food. While the current food guide may be more affordable for families because it puts less emphasis on meat and dairy products than the previous one, demand will increase for other foods. Researchers caution that, as produce and plant-based (vegetable) protein prices increaseFootnote 16, pressure on food budgets may become increasingly problematicFootnote 17.

ONPP does not have any financial mechanisms in place (e.g., grants and contributions programming) to incentivize stakeholders to follow their dietary guidance. However, it has collaborated with partners and stakeholders that do. ONPP has worked with many partners and stakeholders (e.g., P/Ts, the Food Directorate, the Public Health Agency of Canada, stakeholders in key settings) that have access to mechanisms to ensure reach and promote healthy eating choices. Leveraging outreach mechanisms with partners like PHAC might serve to further increase the reach of ONPP's public education awareness work. Continuing to explore and track these relationships could inform the utility of a potential ONPP grants and contributions program in the future.

ONPP's mandate, roles and objectives

ONPP's mandate and role are clear but more could be done to clarify ONPP's role versus the Food Directorate's role. To deliver its mandate and carry out its role, ONPP has developed detailed operational and engagement plans as well as a strong performance measurement system. A few gaps were noted around the identification of external factors, and the measurement of a couple of indicators.

ONPP, housed within the Health Products and Food Branch (HPFB), is mandated to help Canadians maintain and improve their nutritional health. Its key functions include responding to nutrition-related public health issues, developing evidence-informed policies and standards, providing strategic advice on nutrition information, and disseminating nutrition knowledge. ONPP was instrumental in developing, and implementing elements of, the Healthy Eating Strategy for Canada, which was launched by the Minister of Health in October of 2016. The Strategy outlines how Health Canada will achieve the commitments set out in the Prime Minister's mandate letter to the Minister of Health related to promoting nutritious food choices, introducing restrictions on the marketing of food and beverages to children, and establishing front-of-package labelling on prepackaged foods that are high in sodium, sugars, and saturated fat.

Most internal interviewees agreed that ONPP's mandate is clear. However, over the years, the division of roles and responsibilities between the ONPP and the HPFB's Food Directorate have become unclear. Uncertainty around specific roles and areas of responsibility were noted, in particular around the education, promotion, and awareness work streams, with staff seeming to be carrying out overlapping and duplicate activities (e.g., education, promotion, and awareness related to nutrition labeling). In some cases, changing priorities and staffing changes have resulted in a functional transfer of files to the Food Directorate, even though those files remain part of ONPP's mandate (e.g., aspects of food and nutrition surveillance). Those decisions were not documented and therefore remain unclear to both ONPP and the Food Directorate.

ONPP has established many processes and tools to advance work priorities in support of the delivery of their mandate. Those include strategic plans, annual operational work plans with specific deliverables and allocated full-time equivalent resources, terms of references for various working groups, and engagement calendars. Inconsistencies were noted with the full completion of organizational charts and annual work plans (i.e., although the documents exist, they are not finalized, nor are they up-to-date). While joint bilateral meetings between the Food Directorate and ONPP's senior management take place on ad hoc basis, there are no other formal mechanisms between the two directorates to outline roles and responsibilities, nor are there mechanisms guiding joint or collaborative activities.

While ONPP has continued to work on priorities in support of their mandate, they have adjusted some of their activities to align with their current staffing levels. For instance, they minimized their involvement in the Food and Nutrition Surveillance System working group and deferred other research-related activities such as research to assess the broader determinants of health's impact on nutrition and healthy eating, especially during the revision of the food guide.

The evaluation did not delve into some of these specific challenges, as a more in-depth review was being undertaken by ONPP to clarify the differences in roles and responsibilities between the Food Directorate and ONPP. That review identified several possible solutions, including the need for senior leadership to clarify both groups' mandates, objectives, and roles and responsibilities, along with developing a more formal governance structure to guide the groups' joint work.

Performance measurement

The Food and Nutrition Program's logic model has clearly articulated outcomes that are logical and appropriate, and support the achievement of program goals. ONPP's work is well reflected in this logic model. The majority of indicators identified in the Performance Information Profile are also well defined and aligned with priorities, including the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals.

There are a few aspects that could be improved:

- As noted earlier, external factors affect Canadians' healthy eating decisions. The Performance Information Profile does not currently outline those factors. Solid, evidence-based, and accessible resources on healthy eating, such as the ones produced by ONPP, are not the only factors influencing food and eating decisions.

- Similarly, a few indicators linked to medium-term outcomes were either missing or were lacking a more systematic measurement strategy.

- Some key data sources are outside of the control of ONPP. The collection of national data, on eating habits and other health-related factors, led by Statistics Canada, does not follow a regular, nor timely, schedule. Similar gaps currently exist with SGBA Plus data. Sample sizes restrict the availability and accuracy of disaggregated data, which then impedes the program's ability to develop products targeted to specific populations. The lack of an agreement between Statistics Canada and Health Canada is hindering ongoing data collection to help ONPP monitor its key performance indicators.

ONPP also collects data through surveillance and monitoring activities (e.g., to assess the impacts of advertising), consultations, and public opinion research (e.g., Canada's food guide revisions, eating patterns during COVID). As well, ONPP leverages its work with experts across the country to measure the current food environment. For instance, it works with the International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable disease Research, Monitoring and Action Support Canada (INFORMAS Canada) members and others to develop methodologies and share data about the food environment.

Efficiency and economy

ONPP resources have been effectively managed. Expenditures led to minor deficits in salary dollars and some surpluses in operations and maintenance (O&M) funds the latter being affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

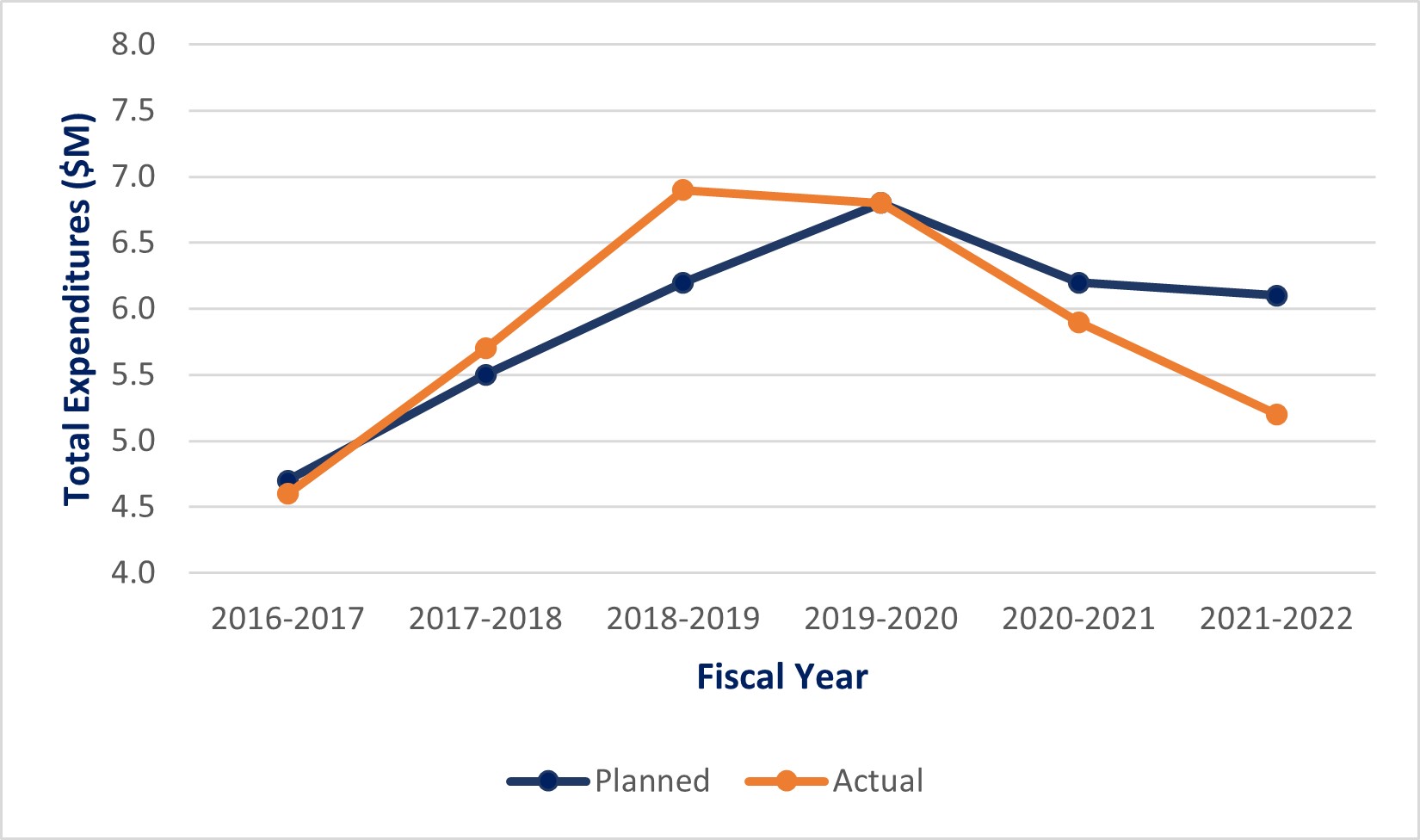

ONPP's budget has remained relatively stable over the past six fiscal years, averaging approximately $6 million per year. The budget was increased in 2017-18, but the most prominent increase came in 2019-20 when their budget totalled $6.8 million (see Appendix 2, Table B). These increases were temporary allocations provided to support Healthy Eating Strategy commitments, including the launch of Canada's food guide.

Note: Figures include salary costs for students and Employee Benefit Plan (at 20% for 2016-17 to 2018-19, and 27% for 2019-20 to 2021-22)

Source: Chief Financial Officer Branch

Table C: Text description

The table presents the variance between planned vs. actual spending from 2016-17 to 2021-22 in millions of dollars, as follows:

| Spending | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned | 4.7 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 6.8 | 6.2 | 6.1 |

| Actual | 4.6 | 5.7 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 5.9 | 5.2 |

ONPP slightly exceeded its planned expenditures in 2017-18 and 2018-19 (approximately 104% and 111%, respectively) and lapsed some of its planned expenditures in other years, with most of it (approximately 15%, or $900,000) in 2021-22. Many planned activities and deliverables were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, as some contracts and agreements were not pursued, including some Canada's food guide promotional activities, monitoring marketing to children, and public opinion research to inform healthy eating initiatives. Prior to the release of the new food guide, shifting priorities on revising the food guide contributed to unspent operations and maintenance funds. ONPP has slightly overspent its salary budget in the past five years, with an overall average deficit of approximately $600,000 per fiscal year, the highest taking place in 2018-19.

Since 2018-19, ONPP has reduced its expenditures to stay within their allocated budget. They were able to do so despite new initiatives being added to their workload, such as monitoring marketing to children, promoting the food guide in key settings, and work on the Nutrition Science Advisory Committee. However, as outlined earlier in the report, the completion of some work has been affected.

Conclusion

Many Canadians are not adopting healthy eating habits, despite being well aware of Health Canada's healthy eating and nutrition information, and having accessed those resources in great numbers. ONPP has made Canada's food guide and additional resources more accessible, relevant, and useful than ever before. It has considered and applied diversity and inclusion and SGBA Plus in the development of numerous resources. Nonetheless, barriers and external factors prevent Canadians from adopting a healthy diet. Many factors in the food environment, including food accessibility and the influence of social media affect Canadians' healthy eating decisions.

Health Canada is not the only player in the world of healthy eating. Many other partners and stakeholders at the national, provincial, territorial, regional, and local levels work to help Canadians eat healthy. They rely on ONPP's nutrition policies and resources in their day-to-day work. Health Canada and ONPP's mandate is well recognized and they are seen as a trusted source.

Collaboration with partners and stakeholders has not been consistent over the years. In the past few years, with limited resources in place, ONPP focussed on revising and promoting Canada's food guide. This resulted in other work being paused (e.g., reviewing infant nutrition guidelines). In some cases, external factors resulted in ONPP being unable to seek input from partners and stakeholders on a few key deliverables, and in other cases, ONPP was unable to produce some deliverables in a timely manner. With expectations not fully met, some partners and stakeholders developed their own resources.

There is some confusion internally within Health Canada when it comes to ONPP's role versus that of the Food Directorate within the HPFB. There are limited formal mechanisms in place to clarify the collaboration and synergies that need to exist between the two groups. Furthermore, to compensate for a shift in resources, some work that was originally within ONPP's mandate was moved to, and still resides with, the Food Directorate. There is a need to clarify the mandates and roles and responsibilities between ONPP and the Food Directorate, as existing confusion among staff had led to duplicated functions, knowledge gaps, and deferred and limited engagement between teams.

ONPP's work is well represented within the Food and Nutrition Program's Performance Information Profile. The program's objectives and expected outcomes are clear, logical, and appropriate. Most of the key indicators tracked by ONPP are appropriate and useful, but a few measures could be strengthened. However, as noted above, the healthy eating decisions of Canadians are influenced by many considerable external factors, and those should be specified in the Performance Information Profile to ensure they are considered when interpreting results.

Recommendations

The findings from this evaluation have resulted in the recommendations listed below.

Recommendation 1: Explore ways to address engagement issues.

Although engagement is a strength, a few projects would have benefited from the early involvement of key partners and stakeholders. Recognizing that the promotion of healthy eating is important, resources are scarce, and many other organizations could contribute, there is value in examining additional collaborations with key partners and stakeholders. This could include developing resources with others. In addition, continuing to work collaboratively with partners and stakeholders will further support changes to the food environment and not only should "traditional" partnerships be considered, but new ones as well (e.g., Indigenous organizations, food service providers in key settings).

Recommendation 2: Ensure that upcoming activities are reflective of the evolving food environment (e.g., COVID-19 related impacts on nutrition and healthy eating, inflation) and are undertaken with responsible groups (i.e., governance bodies and agreements), when appropriate.

The Healthy Eating Strategy and the ONPP strategic plan were developed and implemented before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and before recent food inflation. As ONPP continues to deliver on the plans' commitments as well as its additional ongoing work, it should consider the current food environment and determine its impact on planned activities. To ensure that proper channels are used to undertake and oversee work to address the evolving food environment, it will be important to clarify long standing roles (e.g., Food Directorate) by developing clear objectives, roles and responsibilities via formal or informal governance bodies and agreements.

Recommendation 3: Improve performance measurement by:

- reassessing the current medium-term outcomes' related indicators; and

- articulating how external factors and barriers affect the achievement of outcomes and the impact of activities.

ONPP has a well-developed performance information profile with clearly articulated outcomes. They collect performance data and surveillance and monitoring data to assess activities that affect the food environment. However, limited performance information for some medium-term outcomes made it challenging to assess the achievement of those outcomes. ONPP should consider developing or refining some of the indicators with more systematic measurement strategies as well as establishing an agreement with Statistics Canada to ensure the ongoing collection of relevant national data to help address some of the existing data gaps. Finally, clearly articulating how external factors affect Canadians' healthy eating decisions and can act as barriers to the achievement of ONPP's outcomes could provide an appropriate context for such a complex and multifaceted issue.

Management Response and Action Plan

Recommendation 1:

Explore ways to address engagement issues.

Although engagement is a strength, a few projects would have benefited from early involvement of key partners and stakeholders. Recognizing that the Healthy Eating Strategy's initiatives are important; resources are scarce; and many other organizations could contribute, there is value in examining additional collaborations with key partners and stakeholders. This could include developing resources in collaboration with others. In addition, continuing to work collaboratively with partners and stakeholders will further support changes to the food environment and, to do so, not only should "traditional" partnerships be considered but new ones as well (e.g., Indigenous organizations, food service providers in key settings).

Management response:

Management agreed with the recommendation.

| Key Activities | Deliverables | Responsible Directorate | Timeframe | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

At the outset of developing a new policy or tool for integration or use in other programs or policies, the Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion (ONPP) applies the department's decision-making framework. This includes involving interested and affected parties throughout the development process, such as other federal departments and levels of government, the public, and other stakeholders, and as early as possible in the process. In doing so, this helps mitigate issues and ensure timely feedback so not to delay release dates. In this context, ONPP will: 1) Work to ensure that Indigenous partners and stakeholders are engaged, leverage networks and programs. Broaden bilateral engagement with Indigenous partners and stakeholders and participation in key fora, including the Inuit Crown Partnership Committee on food security. |

1) ONPP will develop and maintain planning and reporting tools, such as stakeholder engagement plans, and, decisions from meetings. |

HC-HPFB-ONPP |

1) December 2023 |

Existing resources |

2) Explore and assess opportunities to collaborate with internal and external stakeholders to develop resources, support the implementation of healthy eating recommendations and improve the food environment. This includes opportunities for co-development. |

2) ONPP will put in place agreements (e.g., MOA), contracts, and track collaborative discussions with stakeholders and partners. |

2) December 2023 |

||

3) Update, implement, and maintain existing stakeholder tracking and engagement tools to support strategic stakeholder interactions, as well as planning and reporting needs. |

3) Finalize stakeholder engagement assessment tools and implement their use to ensure a consistent and strategic approach to stakeholder engagement activities. Activities will be documented in stakeholder calendar. |

3) November 2023 |

||

4) Explore opportunities to collaborate with PHAC and Sport Canada on advancing healthy eating. |

4) ONPP will develop interdepartmental governance mechanisms and collaborative agreements, such as MOAs, MOUs, ILAs, terms of reference and work plans for working groups to advance healthy living policy and programs |

4) December 2023 |

Recommendation 2:

Ensure that upcoming activities are reflective of the evolving food environment (e.g., COVID-19 related impacts on nutrition and healthy eating, inflation), and are undertaken with responsible groups (i.e., governance bodies and/or agreements) where and when appropriate.

The Healthy Eating Strategy and the ONPP strategic plan were developed and implemented before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and before recent food inflation. As ONPP continues to deliver the plans' commitments, it should consider the current food environment and determine its impact on planned activities. To ensure that proper channels are used to undertake and oversee work to address the new food environment it will be important to clarify long standing roles (e.g., Food Directorate) by developing clear objectives, roles and responsibilities via formal or informal governance bodies and/or agreements.

Management response:

Management agrees with the decision.

| Key Activities | Deliverables | Responsible Directorate | Timeframe | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

ONPP will conduct the following activities: 1) Continue to take account and consideration of food environment as it relates to mandated roles and responsibilities (i.e., developing and implementing evidence-based policy that defines healthy eating and promoting environments that support Canadians in making nutritious food choices), through multiple existing processes. |

1) Expand evidence monitoring to include evidence on the food environment. |

HC-HPFB-ONPP |

1) June 2024 |

1) Existing resources |

2) Examine facilitators and barriers of the use and integration of Canada's food guide as part of an outcome assessment of Canada's food guide (and associated resources). Learnings from the assessment to support strengthening stakeholder engagement, will be documented. |

2) Conduct the outcome assessment and complete a report to share the findings. |

2) June 2024 |

2) Existing resources (O&M contract) |

|

3) Contribute to the update of food environment indicators in Health Canada's Food and Nutrition Surveillance Indicator Framework; and collaborate with internal and external partners to implement (Food Directorate and PHAC). |

3) Updated Food and Nutrition Surveillance Indicator Framework |

HC-HPFB-FD-ONPP |

3) June 2024 |

3) Existing resources |

4) Establish executive-level governance to address collaboration and decision-making between ONPP and the Food Directorate related to nutrition mandates. |

4) Complete review of ONPP and Food Directorate roles and collaboration and introduce protocols and governance mechanisms such as Terms of Reference, sharing work plans, to enhance synergies and cooperation. |

4) June 2023 |

4) Existing resources |

Recommendation 3:

Improve performance measurement by:

- reassessing the current medium-term outcomes' related indicators

- articulating how external factors and barriers affect achievement of outcomes and impact of activities

ONPP has a well-developed performance information profile with clearly articulated outcomes. They collect performance data as well as surveillance and monitoring data to assess activities that affect the food environment. However, limited performance information for some medium-term outcomes made it challenging to assess the achievement of those outcomes. ONPP should consider developing or refining a few of the indicators with more systematic measurement strategies as well as establishing an agreement with Statistics Canada to ensure the ongoing collection of national data – these actions will help address some of the existing data gaps. Finally, clearly articulating how external factors impact Canadian's healthy eating decisions and can act as barriers to the achievement of ONPP's outcomes could provide the appropriate context to such a complex and multifaceted issue.

Management response:

Management agrees with the decision.

| Key Activities | Deliverables | Responsible Directorate | Timeframe | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

The Food and Nutrition Program aligns with the Departmental Results Framework "Health Protection and Promotion" Core Responsibility and supports the result "Canadians make healthy choices". As part of this program, the office works with its partners to identify and fill information gaps. ONPP also contributes to the development of Canadian health surveys, analyzes data and interprets survey results, monitors public health nutrition indicators, and contributes to the improvement of national nutrition data collection tools. 1) Review and analysis of current PIP outcomes and indicators, and identification of areas requiring improvements. |

1) Document detailing findings (i.e., areas requiring improvements from the review and analysis of current PIP outcomes and indicators) and intended implementation timelines (where applicable) |

1) HC-HPFB-ONPP |

1) March 2024 |

Existing resources |

2) Addition of the "theory of change" component for the nutrition policy and promotion aspect of the program logic model. This annex to the PIP will articulate external factors and barriers that could impact outcomes and activities. |

2) Theory of change annex developed and approved. |

2) HC-HPFB-ONPP-RMOD-FD |

2) October 2023 |

Appendix 1 – Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Evaluators collected and analyzed data from multiple sources. Data collection started in February 2022 and ended in July 2022. Evidence from multiple data sources was collected and analyzed, including interviews, document and file review, literature review, and financial data review.

Performance Data Review

The evaluation collated and compared annual updates to performance indicators and supplementary quarterly and annual reports to established targets.

Key Informant Interviews

Key informant interviews were conducted to gather in-depth information related to governance, funding, methodology, expertise, and effectiveness. Interviews were conducted based on a predetermined interview guide. In total, 22 interviews were conducted. Respondents included:

- Internal: program staff (n=nine interviews)

- Other Government Departments (n=five interviews)

- Provincial and territorial partners (n=four interviews)

- NGO (n= two interviews)

- Industry (n=one)

- External expert (n=one)

Emerging themes from interviews were identified and quantified.

Financial Analysis

ONPP provided verified financial data demonstrating planned and actual expenditures for the period covered by the evaluation (April 2016-17 to March 2021-22).

File and Document Review

Program file and document reviews included documents provided by ONPP, including:

- Administrative files

- Terms of Reference for committees and partnerships

- Stakeholder calendar engagements, meeting minutes, and Records of Decisions

- Briefing and research summary reports.

Literature Review

Journal articles and grey literature documentation were reviewed and analyzed to inform current and emerging trends and continued need for the program.

Approximately 240 files, documents, and articles were reviewed.

| Limitation | Impact | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Key informant interviews are retrospective in nature, providing only a recent perspective on past events. | This can affect the validity of assessments of activities or results that may have changed over time. | Triangulation with other lines of evidence substantiated or provided further information on data captured in interviews. |

| External key informants were identified based on purposive sampling. Project timelines placed constraints on the number of external interviews that could be completed. | External key informant interview findings cannot be interpreted as representing the views of all stakeholders or categories of stakeholders. | Interview findings are used in conjunction with other lines of evidence, such as file and document review. |

| Performance measurement data and information were limited to measure the achievement of one particular outcome (i.e., knowledge and skills of Canadians). | This can affect the proper assessment of the program outcome. | External sources, such as published research articles, were used to help provide additional information and data. |

| The evaluation did not have sufficient time and resources to conduct a thorough scan of stakeholders' websites. | The information presented may not provide an accurate picture of integration. | A random sample of websites across a variety of stakeholders were selected to give an overview of integration. |

The evaluation considered the SGBA+ lens in its assessment of ONPP activities, including a discussion of equity issues in the development of resources. Although official languages were not specifically examined, they were not found to be an issue for the program's activities. Furthermore, an examination of the Sustainable Development Goals was not applicable for this evaluation.

The scope for this evaluation was shared secretarially with the Performance Measurement, Evaluation and Results Committee (PMERC) in January 2022. The preliminary findings were presented at PMERC in October 2022, and the final report will be presented at PMERC in January 2023.

Appendix 2 – Variance between planned vs. actual spending – 2016-17 to 2021-22 ($M)

| Fiscal Year | Planned ($M) | Expenditures ($M) | Variance ($M) | % of planned budget spent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salary | O&M | Total | Salary | O&M | Total | |||

| 2016-2017 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 4.7 | 3.8 | 0.8 | 4.6 | + 0.1 | 97.9% |

| 2017-2018 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 0.9 | 5.7 | - 0.2 | 103.6% |

| 2018-2019 | 3.8 | 2.4 | 6.2 | 5.3 | 1.6 | 6.9 | - 0.7 | 111.3% |

| 2019-2020 | 5.2 | 1.6 | 6.8 | 5.3 | 1.5 | 6.8 | - | 100% |

| 2020-2021 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 6.2 | 4.7 | 1.2 | 5.9 | + 0.3 | 95.2% |

| 2021-2022 | 4.3 | 1.8 | 6.1 | 4.3 | 0.9 | 5.2 | + 0.9 | 85.2% |

| 6 Years TOTAL | 24.6 | 10.9 | 35.5 | 28.2 | 6.9 | 35.1 | + 0.4 | 98.9% |

|

Source: Chief Financial Officer Branch |

||||||||

Endnotes

- Footnote 1

-

Murray, T. S., Hagey, J., Willms, D., Shillington, R., & Desjardins, R. (2008). Health literacy in Canada: a healthy understanding. Retrieved from http://www.en.copian.ca/library/research/ccl/health/health.pdf

- Footnote 2

-

Health Canada. (2016). Healthy Eating Strategy. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/food-nutrition/healthy-eating-strategy.html

- Footnote 3

-

Varin M, Hill MacEachern K, Hussain N, Baker MM. (2021). Measuring self-reported change in alcohol and cannabis consumption during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. Received from https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.41.11.02

- Footnote 4

-

Polsky, J. Y., Moubarac, J. C., & Garriguet, D. (2020). Consumption of ultra-processed foods in Canada. Health Reports, 31(11), 3-15. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/docview/2473420106?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

- Footnote 5

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2011). Obesity in Canada: a joint report from the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Retrieved from https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2011/aspc-phac/HP5-107-2011-eng.pdf

- Footnote 6

-

Diabetes Canada. (2020). Diabetes in Canada: Backgrounder. Retrieved from https://www.diabetes.ca/DiabetesCanadaWebsite/media/Advocacy-and-Policy/Backgrounder/2020_Backgrounder_Canada_English_FINAL.pdf

- Footnote 7

-

Lieffers JRL, Ekwaru JP, Ohinmaa A, Veugelers PJ. (2018). The economic burden of not meeting food recommendations in Canada: The cost of doing nothing. PLoS ONE 13(4): e0196333. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196333

- Footnote 8

-

Charlebois, S., Smook, M., Wambui, B. N., Somogyi, S., Racey, M., Fiander, D., Music, J. & Caron, I. (2021). Can Canadians afford the new Canada's Food Guide? Assessing Barriers and Challenges. Journal of Food Research, 10(6), 1-22. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356567566_Can_Canadians_afford_the_new_Canada%27s_Food_Guide_Assessing_Barriers_and_Challenges

- Footnote 9

-

Charlebois, S., Smook, M., Wambui, B. N., Somogyi, S., Racey, M., Fiander, D., Music, J. & Caron, I. (2021). Can Canadians afford the new Canada's Food Guide? Assessing Barriers and Challenges. Journal of Food Research, 10(6), 1-22. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356567566_Can_Canadians_afford_the_new_Canada%27s_Food_Guide_Assessing_Barriers_and_Challenges

- Footnote 10

-

Charlebois, S., Smook, M., Wambui, B. N., Somogyi, S., Racey, M., Fiander, D., Music, J. & Caron, I. (2021). Can Canadians afford the new Canada's Food Guide? Assessing Barriers and Challenges. Journal of Food Research, 10(6), 1-22. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356567566_Can_Canadians_afford_the_new_Canada%27s_Food_Guide_Assessing_Barriers_and_Challenges

- Footnote 11

-

Mintel Group Ltd. (2020). Attitudes toward health eating: including impact of COVID-19. Retrieved from https://store.mintel.com/report/canada-attitudes-towards-healthy-eating-market-report

- Footnote 12

-

Mintel Group Ltd. (2020). Attitudes toward health eating: including impact of COVID-19. Retrieved from https://store.mintel.com/report/canada-attitudes-towards-healthy-eating-market-report

- Footnote 13

-

University of Waterloo. (2018-2020). International Food Policy Study. Retrieved from http://foodpolicystudy.com/

- Footnote 14

-

Polsky, J. Y., & Garriguet, D. (2021). Eating away from home in Canada: impact on dietary intake. Health Reports, 32(8), 26-34. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/docview/2562945979?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

- Footnote 15

-

Polsky, J. Y., & Garriguet, D. (2021). Health Report - Eating away from home in Canada: Impact on dietary intake. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2021008/article/00003-eng.htm

- Footnote 16

-

Charlebois, S., Smook, M., Wambui, B. N., Somogyi, S., Racey, M., Fiander, D., Music, J., & Caron, I. (2021). Can Canadians afford the new Canada's Food Guide? Assessing Barriers and Challenges. Journal of Food Research, 10(6), 1-22. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356567566_Can_Canadians_afford_the_new_Canada%27s_Food_Guide_Assessing_Barriers_and_Challenges

- Footnote 17

-

Arrel Food Institute. (2019-03-14). New food guide will save Canadians money but few are following it, study finds. Retrieved from https://arrellfoodinstitute.ca/new-food-guide-study/