Homelessness and substance-related acute toxicity deaths: a descriptive analysis of a national chart review study of coroner and medical examiner data

National chart review study of substance-related acute toxicity deaths results:

This is the first of a number of publications from a national chart review study of coroner and medical examiner data from 2016 and 2017. The study captures information on substance-related acute toxicity deaths (sometimes called "overdose" or "poisoning" deaths) and aims to better understand the characteristics of the people who died, substances involved, and circumstances of the death. Each publication will focus on specific themes or populations.

Key findings

- People experiencing homelessness are over-represented among those who died of substance-related acute toxicity in 2016 and 2017. Most of their deaths were accidental.

- Of those who died of acute toxicity and were experiencing homelessness at the time of their death in 2016 or 2017, at least:

- 1 in 10 were released from a correctional or health care institution in the month before their death

- one quarter of the acute toxicity events leading to their deaths happened in an outdoor setting

- Of those who died of acute toxicity in 2016 or 2017, those who experienced homelessness at the time of their death:

- more often had a history of substance use

- had a similar percentage known to have a substance use disorder

- were less often known to have a mental health condition

- more often had an opioid or stimulant identified as a cause of death

- had opioids and stimulants found in combination in more than half of their deaths

Background

The overdose crisis in Canada is a significant public health concern, with 29,052 deaths between January 2016 and December 2021 related to apparent opioid toxicity alone.Footnote 1 Provincial and municipal reports show that some populations have been more affected than others, including people experiencing homelessness.Footnote 2Footnote 3Footnote 4Footnote 5 In 2016, an estimated 235,000 people were experiencing homelessness and 22,190 people were in shelters on any given night.Footnote 6Footnote 7

People experiencing homelessness have higher rates of substance use than the general population.Footnote 8 The relationship between housing insecurity and substance use is complex. Substance use is both a reason for housing loss and a way of dealing with the difficulties and dangers of life without a secure home.Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11Footnote 12 People experiencing homelessness have added pressure to conceal or rush substance use, use alone, and use larger amounts to avoid drug possession charges.Footnote 13Footnote 14 These substance use patterns are more dangerous and can lead to higher rates of acute toxicity events.Footnote 15

Previous research has shown that trauma and mental health conditions are possible risk factors for harmful use of substances and for homelessness.Footnote 16Footnote 17Footnote 18Footnote 19 The added fear and stress of limited resources, lack of safety, and stigma associated with homelessness and substance use can also negatively impact mental health.Footnote 20Footnote 21Footnote 22Footnote 23 Barriers to services and not seeking services due to social exclusion and stigma can also contribute to poor physical and mental health in this population.Footnote 22Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26

Transitions between stays in health and correctional facilities and returning to the community are high-risk periods for homelessness.Footnote 6 Furthermore, there is a link between recent release from these facilities and high risk for acute toxicity events because of reduced drug tolerance.Footnote 27

This report describes the relationship between homelessness and substance-related acute toxicity deaths, including the characteristics of people who died, substances involved, and the circumstances of their death. The findings presented here use coroner and medical examiner data (available as of June 2022) from a national chart review study on substance-related acute toxicity deaths in 2016 and 2017. They also draw on 2016 data and reports from Statistics Canada, the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, and Employment and Social Development Canada. For details on the data sources and their limitations, refer to the technical notes section.

Definitions included in this report

Acute toxicity death (sometimes described as an "overdose" or "poisoning" death): An individual who, according to the death certificate, autopsy report, or coroner or medical examiner report, died after an acute intoxication/toxicity resulting from substance use where one or more of the substances was a drug or alcohol. This includes deaths with an accidental (unintentional), suicide (intentional), or undetermined manner of death. See the technical notes for more detail.

Homelessness: Homelessness describes the situation of an individual without stable, safe, or appropriate housing, or the immediate means or ability to acquire it. This includes people living unsheltered on the street, staying in emergency shelters, and temporarily accommodated by couch surfing or staying with friends or family. It also includes people at immediate risk of homelessness because of job loss or eviction by a property owner, for example. See the Canadian definition of homelessness for a detailed typology.Footnote 28

Not identified as experiencing homelessness: Includes people who died from acute toxicity who did not have any information suggesting that they were experiencing or had experienced homelessness. People in this category may have been stably, safely, and appropriately housed or their file did not have enough information to determine their housing history.

Any evidence of a mental health condition: Case files were examined for any record of depression, bipolar disorder, suicidal ideation, schizophrenia, anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, eating disorder, personality disorder, inpatient mental health treatment, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder. Both witness statements about diagnoses and official diagnoses by health professionals were included as evidence of a mental health condition.

Potentially traumatic events: Trauma is "an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual's functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being."Footnote 29 To assess exposure to potentially traumatic events, abstractors recorded any evidence in the case file that the person who died had experienced a traumatic event in their lifetime. See the technical notes for examples. It was also noted whether any of the potentially traumatic events occurred within two weeks of the person's death.

Minimum proportion: The minimum number of people in a group that fit in a given category, usually described as a percentage (for example, the minimum percentage of people experiencing homelessness among all people who died of acute toxicity). This means that at least this many people have a characteristic, and there may be more we do not know about, given the nature of the data of interest and the way in which data are collected.

Results

People experiencing homelessness are overrepresented among those who died of acute toxicity

Based on the available data for 8,798 Canadians who died of acute toxicity in 2016 or 2017, at least:

- 7.8% (686) were experiencing homelessness at the time of their death

- 8.3% (732) experienced homelessness within six months of their death

- 1.0% (86) experienced homelessness during their lifetime as a direct result of substance use

For comparison, based on the total estimated Canadian population of 35,151,728 in 2016,Footnote 6Footnote 7Footnote 30 an estimated:

- 0.06 to 0.10% of Canadians experienced homelessness on a given day in 2016

- 0.67% of Canadians experienced homelessness that year

Compared to estimates for the general population, people who are experiencing homelessness are overrepresented among those who died of acute toxicity.

Characteristics of people who were experiencing homelessness at the time of an acute toxicity death

Among people who died of acute toxicity, those who were experiencing homelessness tended to be younger, aged 20 to 49 years old, and were more often male when compared to those not experiencing homelessness (Table 1). When compared with the general population of CanadiansFootnote 30 or the general population of Canadians experiencing homelessness in 2016,Footnote 9 people who died of acute toxicity and were experiencing homelessness were more commonly between 30 and 59 years old and more often male (Table 1).

| Characteristic | People who died of acute toxicity and were experiencing homelessness at time of deathTable 1 footnote aTable 1 footnote b (minimum proportion) (N < 686) |

People who died of acute toxicity and were not identified as experiencing homelessnessTable 1 footnote aTable 1 footnote b (N < 8,020) |

Canadians who were homelessTable 1 footnote c (estimated proportion) (N = 4,266) |

All CanadiansTable 1 footnote d (N = 35,151,728) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Sex | ≤19 years | 1.5% | 2.2% | 24.4% | 22.4% |

| 20 to 29 years | 20.4% | 16.3% | 18.2% | 12.9% | |

| 30 to 39 years | 31.0% | 23.8% | 20.5% | 13.1% | |

| 40 to 49 years | 24.3% | 21.4% | 12.6% | 13.1% | |

| 50 to 59 years | 20.1% | 23.4% | 6.9% | 15.1% | |

| 60+ years | 2.6% | 12.8% | 17.5% | 23.4% | |

| Sex - Male | All ages | 77.8% | 70.3% | 62.3% | 49.1% |

| ≤19 years | Suppressed | 1.2% | 12.6% | 11.5% | |

| 20 to 29 years | 15.2% | 12.4% | 13.3% | 6.5% | |

| 30 to 39 years | 23.5% | 18.5% | 16.2% | 6.4% | |

| 40 to 49 years | 19.8% | 15.1% | 8.9% | 6.4% | |

| 50 to 59 years | 16.3% | 15.5% | 3.2% | 7.4% | |

| 60+ years | Suppressed | 7.5% | 8.1% | 10.8% | |

| Sex - Female | All ages | 22.2% | 29.7% | 37.7% | 50.9% |

| ≤19 years | Suppressed | 1.0% | 11.8% | 10.9% | |

| 20 to 29 years | 5.2% | 3.9% | 4.9% | 6.4% | |

| 30 to 39 years | 7.6% | 5.3% | 4.3% | 6.7% | |

| 40 to 49 years | 4.5% | 6.3% | 3.7% | 6.7% | |

| 50 to 59 years | 3.8% | 7.9% | 3.7% | 7.7% | |

| 60+ years | Suppressed | 5.3% | 9.4% | 12.6% | |

|

Data sources: |

|||||

Among people who died of acute toxicity, a larger proportion of people who were experiencing homelessness had a history of substance use than people who were not identified as experiencing homelessness, but proportions of people with a history of substance use or alcohol use disorder were similar across both housing situations (Table 2). A smaller proportion of people experiencing homelessness had evidence of any mental health condition (28.4%) compared to those not identified as experiencing homelessness (43.4%).

Half (50.3%) of people who were experiencing homelessness at the time of their death had a history of at least one potentially traumatic event, which is about 10% higher than people who were not identified as experiencing homelessness (Table 2). About one in twenty people who died of acute toxicity experienced a potentially traumatic event in the two weeks prior to their death, for both housing situations.

One in ten people who died of acute toxicity and were experiencing homelessness were released from a correctional or healthcare institution up to one month before their death (Table 2). The proportion released from a correctional facility was higher for people who were experiencing homelessness than for people who were not experiencing homelessness, but the proportions released from a hospital were similar.

| Characteristic | Experiencing homelessness at time of death (minimum proportion) (N = 686) |

Not identified as experiencing homelessness (N = 8,020) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Substance use | History of substance use | 94.1% | 80.7% |

| History of substance use disorderTable 2 footnote a | 19.4% | 18.2% | |

| History of alcohol use disorder | 8.2% | 9.3% | |

| Mental health | Evidence of any mental health condition | 28.4% | 43.4% |

| Potentially traumatic events | History of any potentially traumatic life events | 50.3% | 39.1% |

| One or more potentially traumatic life events experienced in the two weeks prior to death | 5.7% | 5.0% | |

| Recent release from an institution | Release from a correctional facilityTable 2 footnote b up to one month before death | 6.8% | 1.6% |

| Release from a hospital up to one month before death | 3.2% | 2.2% | |

| Total with a recent release from any institutionTable 2 footnote b up to one month before death | 10.4% | 4.3% | |

|

Data source: Data as of June 2022 from a national chart review study of substance-related acute toxicity deaths in 2016 and 2017, Public Health Agency of Canada |

|||

Substances and substance combinations involved in acute toxicity deaths

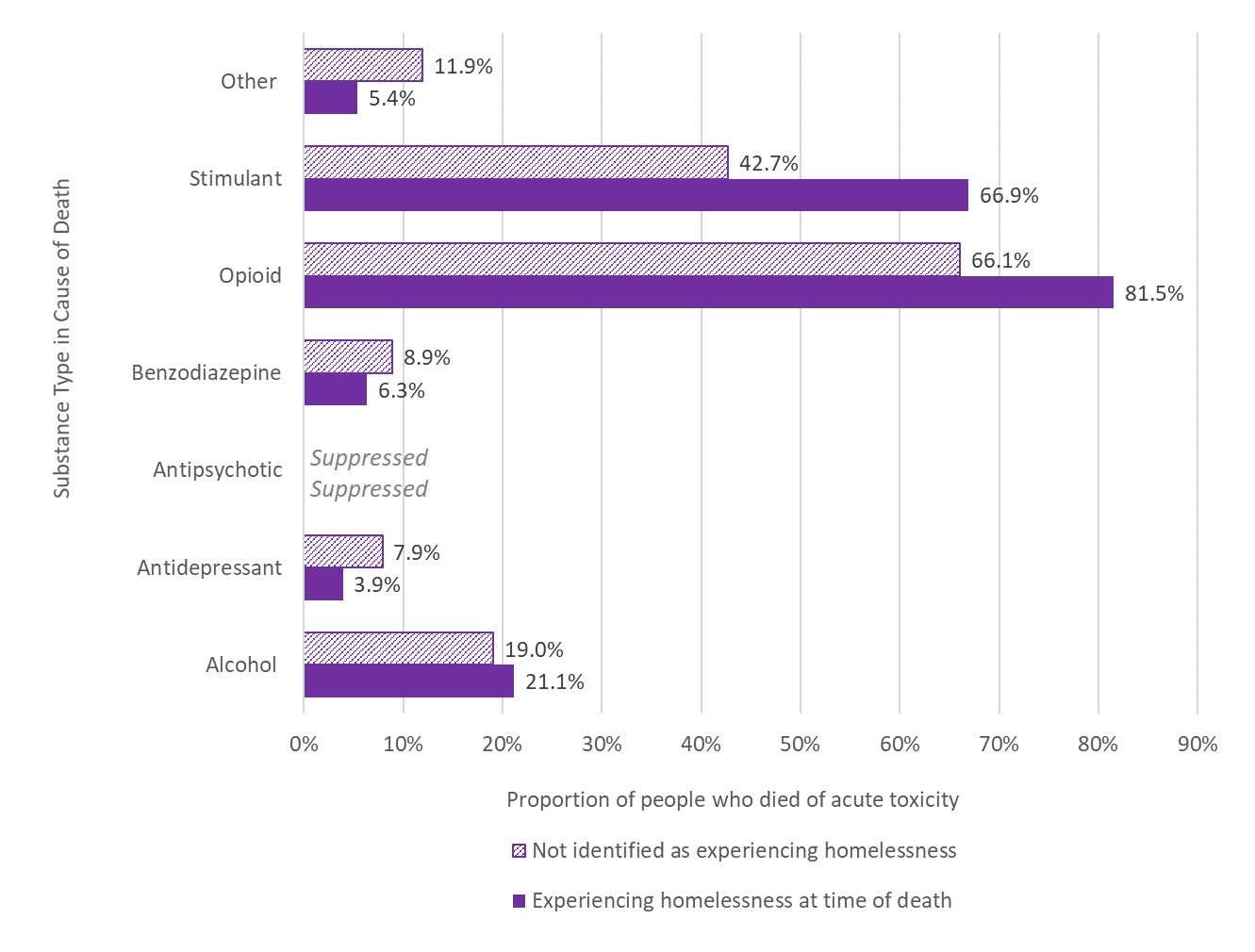

Among people who died of acute toxicity, a higher proportion of those experiencing homelessness had an opioid (81.5%) or stimulant (66.9%) identified as a cause of death than those who were not identified as experiencing homelessness (66.1% and 42.7%, respectively) (Figure 1). The proportions of individuals who had alcohol, antidepressants, antipsychotics, or benzodiazepines identified as a cause of death were similar for people of both housing situations. A lower proportion of those experiencing homelessness had an "other" substance identified as a cause of death (5.4%) when compared to those who were not identified as experiencing homelessness (11.9%).

Figure 1. Proportion of people who died of acute toxicity in 2016 or 2017 by housing situation and substance types identified as a cause of death

| Housing situation | Alcohol | Antidepressant | Antipsychotic | Benzodiazepine | Opioid | Stimulant | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiencing homelessness at time of death | 21.1% | 3.9% | Suppressed | 6.3% | 81.5% | 66.9% | 5.4% |

| Not identified as experiencing homelessness | 19.0% | 7.9% | Suppressed | 8.9% | 66.1% | 42.7% | 11.9% |

Data source: Data as of June 2022 from a national chart review study of substance-related acute toxicity deaths in 2016 and 2017, Public Health Agency of Canada |

|||||||

For both housing situations, the most frequent combinations of substance types causing death involved opioids, stimulants, and alcohol. The proportion of deaths related to both opioids and stimulants was higher among people who were experiencing homelessness (58.2%) compared to those not identified as experiencing homelessness (31.1%). Those who were not identified as experiencing homelessness had a higher proportion of deaths related to opioids alone (21.4%) compared to those who were experiencing homelessness (13.3%).

Circumstances of death

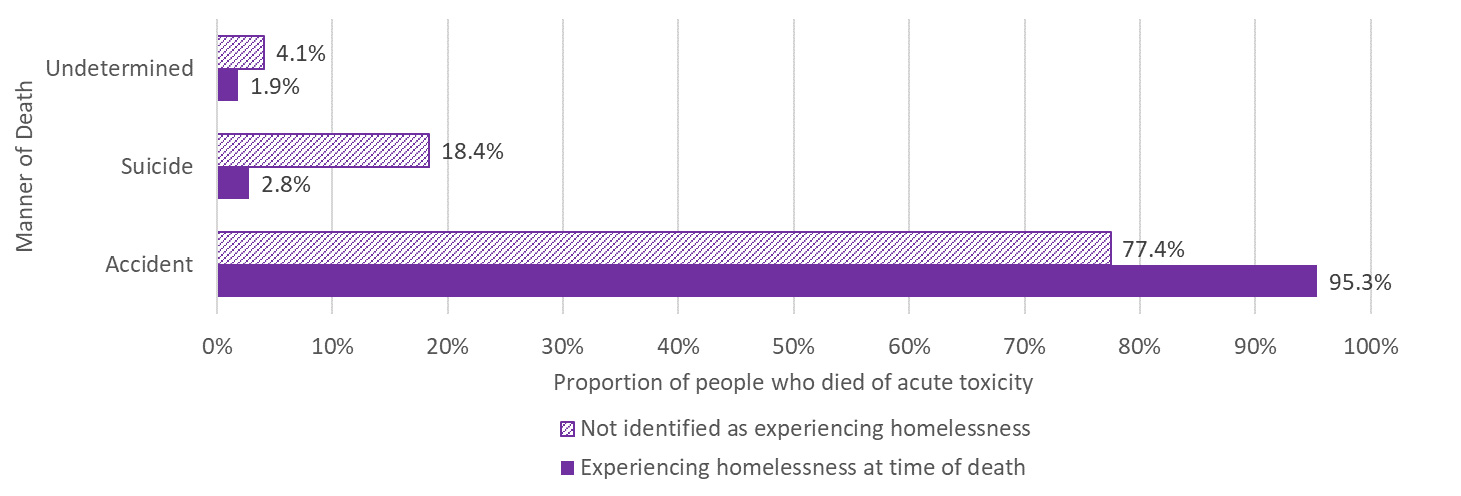

Most acute toxicity deaths among people who were experiencing homelessness were accidental (95.3%), and suicide was rare (2.8%) compared to people who were not identified as experiencing homelessness (18.4%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Proportion of people who died of acute toxicity in 2016 or 2017 by housing situation and manner of death (excluding deaths in British Columbia, where suicide data were not accessible)

| Manner of Death | Experiencing homelessness at time of death (Minimum proportion) (N = 427) |

Not identified as experiencing homelessness (N = 5,791) |

|---|---|---|

| Accident | 95.3% | 77.4% |

| Suicide | 2.8% | 18.4% |

| Undetermined | 1.9% | 4.1% |

Data source: Data as of June 2022 from a national chart review study of substance-related acute toxicity deaths in 2016 and 2017, Public Health Agency of Canada |

||

The acute toxicity event that led to death occurred in an outdoor public place or shelter in greater proportions for people who were experiencing homelessness when compared to people not identified as experiencing homelessness (Table 3). Most (78.2%) acute toxicity events leading to death occurred in a private residence for people who were not identified as experiencing homelessness. For people who died of acute toxicity and were experiencing homelessness, most acute toxicity events took place in a private residence (40.5%) or an outdoor public place (22.6%). The specific setting of one in four acute toxicity events was outdoors (such as, outdoor public places, front or back yards of private residences, sidewalks beside buildings) for people who were experiencing homelessness, compared to only 4.5% of people who were not identified as experiencing homelessness. The location of death was the same as the location of the acute toxicity event for a greater proportion of people not identified as experiencing homelessness (54.2%) compared to those who were experiencing homelessness (44.6%), but a similar proportion of both populations (about one in five people) died in a hospital.

| Location | Experiencing homelessness at time of death (Minimum proportion) (N = 686) |

Not identified as experiencing homelessness (N = 8,020) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Location of acute toxicity event | Outdoor public place | 22.6% | 3.1% |

| Private residenceTable 3 footnote a | 40.5% | 78.2% | |

| Shelter | 8.2% | 0.2% | |

| Hotel or motel | 5.5% | 4.2% | |

| Public building | 4.8% | 1.3% | |

| Other | 9.8% | 2.7% | |

| Specific setting of acute toxicity event | Outdoor setting | 25.1% | 4.5% |

| Vehicle | 1.8% | 1.8% | |

| In or near a bed | 20.3% | 29.9% | |

| Location of death | Location of death was the same as the location of the acute toxicity event | 44.6% | 54.2% |

| Location of death was a hospital | 21.7% | 18.2% | |

|

Data source: Data as of June 2022 from a national chart review study of substance-related acute toxicity deaths in 2016 and 2017, Public Health Agency of Canada |

|||

Discussion

People who are homeless or housing insecure are overrepresented among those who died of acute toxicity deaths in 2016 and 2017, with most of these deaths being accidental. The data presented here suggest several opportunities for connecting with and improving supports for people who are experiencing or at risk of homelessness and are at risk of an acute toxicity death.

1 in 10 people who died of acute toxicity and were experiencing homelessness had been released from a correctional or healthcare institution in the month leading up to their death. The stays in these institutions may or may not be related to substance use. Risk of acute toxicity death may be higher after a recent release from an institution for many reasons. For example, a person's tolerance may be lower after a period of not using substances, the stay could interrupt access to treatments and supports (for example, opioid agonist therapies), and depending on the length of stay, the types of substances available and their toxicity may have changed.Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33 Contact with these institutions may provide opportunities for transition planning and to connect people experiencing homelessness with evidence-based harm reduction, health, and housing services that reduce acute toxicity deaths.

While people who died of acute toxicity and were experiencing homelessness more often had known histories of substance use, they had similar histories of substance use disorders and a lower history of any mental health conditions when compared to those who were not identified as experiencing homelessness. This lack of a recorded history could be due to a lack of access to healthcare services or less information available during death investigations for people who were experiencing homelessness. 1 in every 2 people who died and were experiencing homelessness had experienced at least 1 potentially traumatic event during their life, a higher proportion than those not identified as experiencing homelessness. These findings highlight the need for accessible, inclusive, and trauma-informed healthcare and social services for people experiencing homelessness. People experiencing homelessness have complex medical and social circumstances that require mental health, physical health, and social services be well connected.

A greater proportion of people who died of acute toxicity and were experiencing homelessness had an opioid or stimulant identified as a cause of death, and these were found in combination in more than half of deaths. The pattern of substances involved differed when compared to people not identified as experiencing homelessness. Consulting with people experiencing or at risk of homelessness about the substances they use and their patterns of use may inform more appropriate health promotion and harm reduction services, including safer supply options.

The acute toxicity event location for most people who died and were not identified as experiencing homelessness was in a private residence, but both private residences and outdoor public places were common locations for the acute toxicity events of people who were experiencing homelessness. In addition, one quarter of the acute toxicity events for people who were experiencing homelessness was in an outdoor setting, regardless of location. Substance use in an outdoor setting might increase the odds of a witness noticing a medical emergency, but it could also promote riskier substance use practices while trying to avoid an encounter with law enforcement. Harm reduction programs, housing services, and law enforcement can promote safer environments for substance use, where medical assistance and naloxone are more readily accessible.

Chart review studies of coroner and medical examiner data, while requiring a lot of resources and time, can provide an important depth and breadth of information about the context and risk factors related to preventable deaths. The relationships between homelessness and substance use are complex and improving our understanding of how they relate to acute toxicity deaths can inform strategies and interventions to reduce toxicity deaths in Canada.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge our collaborators at the offices of chief coroners and chief medical examiners across Canada for providing access to their death investigation files, and the co-investigator team (Brandi Abele, Philippe Berthiaume, Matthew Bowes, Songul Bozat-Emre, Jessica Halverson, Dirk Huyer, Beth Jackson, Graham Jones, Fiona Kouyoumdjian, Jennifer Leason, Regan Murray, Jenny Rotondo, Emily Schleihauf, and Amanda VanSteelandt) for their contributions to developing the national chart review study on drug and alcohol-related drug toxicity deaths. We would also like to acknowledge Fiona Kouyoumdjian for major contributions to this report and the many reviewers for their feedback on earlier versions of this report.

Disclaimer

This report is based on data and information compiled and provided by the offices of chief coroners and chief medical examiners across Canada, Statistics Canada, the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, and Employment and Social Development Canada. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the data providers.

Suggested citation

Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. Homelessness and substance-related acute toxicity deaths: a descriptive analysis of a national chart review study of coroner and medical examiner data. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; June 2022.

Technical notes

Methodology

The national drug and alcohol-related deaths study is a time-limited, chart review study of coroner and medical examiner data from 2016 and 2017 to better understand the people who are dying of acute toxicity, the substances involved, and the circumstances of these deaths. This report analyzed data (available as of June 2022) from eight Canadian provinces and the three territories.

Cases include all individuals who died in Canada between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2017 from an acute intoxication/toxicity resulting from the direct effects of the administration of exogenous substance(s) where one or more of the substances was a drug or alcohol. Deaths due to chronic substance use, medical assistance in dying, palliative or comfort care, homicide, occupational exposure, trauma where an intoxicant contributed to the circumstances of the injury (like a car accident), other adverse drug effects (such as anaphylactic shock), or acute toxicity due to products of combustion (like carbon monoxide) were excluded from the study. Variables collected by the data abstractors include (i) socio-demographic risk factors, ii) drug and medical history, iii) antecedent factors, and iv) toxicological findings.

Data abstractors were trained to collect and enter information into a Microsoft Access database according to a shared protocol. The protocol provided guidance on what kinds of information to look for and how to code or describe it in the database. Potentially traumatic events might include, for example: a health problem of a family member or relative, intimate partner problem (for example, divorce, discord), other relationship problem (for example, family argument), job problem, school problem, financial problem, recent suicide of friend/family members, other death of friend/family members, criminal legal problem (for example, arrest, jail, court), other legal problem (for example, custody dispute, civil law), perpetrator of interpersonal violence, victim of interpersonal violence, victim of child abuse, foster care experience, residential school experience, experience of sexual abuse, or experience of physical abuse or assault. An abstractor might also have entered an "other" event with an explanation for how it meets the definition of a potentially traumatic event.

Death investigation protocols and the information available in the case files vary across jurisdictions. Many of the variables collected by this study were not available in the source material for all jurisdictions, therefore, descriptive analysis is limited to the minimum proportions of people who died of acute toxicity and had a given characteristic (in other words, at least this many people in the group belonged to a given category, and there may be more we do not know about).

People who died of acute toxicity in the national data set were categorized into 'experiencing homelessness at the time of death' and/or 'experiencing homelessness within six months of death' based on variables in the database related to their living arrangements, any recent moves within six months of death, and open text comments about the case. The study team used the Canadian definition of homelessness to classify cases.Footnote 28 A specific variable in the database indicates cases where there was evidence that the person experienced homelessness or housing instability as a direct result of substance use in their lifetime. People who died of acute toxicity that did not fall in any of these categories for homelessness were categorized as 'not identified as experiencing homelessness,' and this will include both people who had stable, safe, and appropriate housing and people for whom not enough information was available to determine their housing status.

Other data sources

2016 Coordinated Point-In-Time Count of Homelessness in Canadian Communities, Employment and Social Development Canada:Footnote 9 Between January 1 and April 30, 2016, 32 communities across Canada participated in a coordinated count of people experiencing homelessness in shelters and on the streets within their community. Some of the counts also included people who were in health or corrections facilities and had no place to go when they were released. The count includes survey questions to better understand the population of people experiencing homelessness.

2016 Canada Census Profile, Statistics Canada:Footnote 30 The Census Program provides a statistical overview of the population of Canada every five years. Individuals are counted at their usual place of residence, which can be a private or collective dwelling. While collective dwellings include shelters, the census has limitations in its ability to capture people experiencing homelessness.Footnote 7

Limitations

National estimates of homelessness are based on point-in-time counts of people experiencing homelessness in shelters and/or on the streets in communities. The count might also include people in transitional situations in facilities like hospitals, detox centres, detention centres, or jails who may not have a place to go when they are released. The count is just a one-day snapshot and will not include all people who are homeless in a community over a period of time. People often cycle in and out of homelessness, and people regarded as the "hidden" homeless – those who are temporarily staying with friends or family because they have no home of their own – are less likely to be captured during the count.Footnote 34Footnote 35 People who are experiencing housing insecurity or who are at immediate risk of homelessness are also less likely to be captured during the count. Both the national estimates and chart review study data are point-in-time counts (for national estimates, it is the day of the count; for the chart review study, it is the day of death).

The goal of death investigations is to establish the cause and manner of death and in some cases provide recommendations to prevent future deaths of the same nature. Therefore, coroners and medical examiners are not by design seeking some of the variables of interest to this study. Death investigation protocols and methods of data collection vary across the country and the availability of certain variables will depend on the province or territory of death. In addition, death investigations for people experiencing homelessness generally have less information because it can be difficult to identify witnesses, friends, family members, or service providers who can speak to their history. "Hidden" homelessness is difficult to identify as it is not always clear whether someone was living with a friend or family member due to housing insecurity. Homelessness, history of substance use, history of mental health conditions, and history of potentially traumatic experiences are all likely underreported in the chart review study database. The database represents the minimum proportions of people who had these characteristics (in other words, at least this many people in the group belonged to a given category, and there may be more we do not know about).

The chart review study aimed to capture all deaths in Canada meeting the case definition in 2016 and 2017, however, there were some limitations to the information that could be accessed. Data from Saskatchewan and Manitoba are not included in this report but will be in the final database. Data available from British Columbia included only deaths related to "illicit drugs" (defined as street drugs and medications not prescribed to the person who died) and cases with an accidental or undetermined manner of death; therefore, the number of acute toxicity deaths in British Columbia is underreported in this study. Due to COVID pandemic precautions that limited access to physical files during data abstraction, many cases in Ontario and Quebec from 2017 were only partially abstracted from electronic records and may have slightly less information than earlier cases that were fully abstracted on site.