Substance-related poisonings and homelessness in Canada: a descriptive analysis of hospitalization data

Canada is currently experiencing an overdose crisis affecting people from all walks of life. The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), in collaboration with the provincial and territorial (PT) offices of Chief Coroners and Chief Medical Examiners, PT public health and health partners, and Emergency Medical Service data providers, releases quarterly surveillance data on apparent opioid and stimulant toxicity (overdose) deaths and Emergency Medical Services responses for suspected opioid-related poisonings (overdoses) Footnote 1. PHAC also collaborates with Health Canada to report on hospitalizations for opioid- and stimulant-related poisonings (overdoses) using hospital administrative data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Footnote 1. In addition to ongoing surveillance, PHAC releases targeted analytical reports to help fill gaps identified by stakeholders on specific topics related to substance-related harms.

There are many factors that can play a role in substance use and related harms, including a person's living situation. It is estimated that in Canada, there are on average at least 235,000 people experiencing homelessness in a given year and at minimum 35,000 on a given night Footnote 2. Across the country, an additional 50,000 people a night could be experiencing hidden homelessness Footnote 2. Hidden homelessness refers to people who are temporarily staying with friends, relatives or others because they have nowhere else to live and no immediate prospect of permanent housing Footnote 2. The number of people experiencing homelessness in Canada remains very difficult to estimate, yet this number is thought to be increasing Footnote 2Footnote 3. The rates of substance use are disproportionally high among people experiencing homelessness compared to people with secure housing Footnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 7Footnote 8 and people experiencing homelessness are at a greater risk of substance-related harms Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11. Further, during the COVID-19 pandemic, some disparities in health have widened, particularly among some hard to reach populations, including an increase in the number of people experiencing homelessness, as well as an increase in the number of substance-related poisonings across the country Footnote 12Footnote 13.

It recently became mandatory to capture homelessness status upon admission to hospitals in the CIHI's national hospitalization data effective 2018 Footnote 14. In response to this newly available data, the objective of this analysis is to describe patterns of substance-related poisoning hospitalizations in Canada (excluding Quebec) among people with housing and people experiencing homelessness using the CIHI's Discharge Abstract Database. Data are presented for the time period from April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020, and therefore most of the data included in this analysis captures the pre-pandemic period. This report examines patterns by patient demographics (sex and age), context of the poisoning (substances involved and intention of poisoning), hospitalization characteristics and outcomes (length of stay, intensive care unit admission and discharge disposition), and co-diagnosed mental health conditions. This analysis includes poisonings due to opioids, stimulants, cannabis, hallucinogens, alcohol, other depressants, and psychotropic drugs. To our knowledge, substance-related poisoning hospitalizations among people experiencing homelessness have not yet been reported publicly at a national level using this data source. The results of this analysis can be used to help better understand the intersection of homelessness, mental health, and substance-related harms and how hospital care is experienced differently by people experiencing homelessness.

Definitions included in this report

Substance-related poisoning: A substance poisoning harm (overdose) resulting from the use of a substance in an accidental, intentional, or unknown manner. Poisonings of interest for this report include those due to opioids, stimulants, cannabis, hallucinogens, alcohol, other depressants, and psychotropic drugs. More than one substance may be involved in a poisoning and could be due to intended use of multiple substances at the same time or close in time, or due to a substance unknowingly containing other substances. Information is not available on how substances were obtained and, depending on the substance, may include non-pharmaceutical substances, pharmaceutical substances, or both. Pharmaceutical substances refer to substances manufactured by a pharmaceutical company and approved for medical purposes in humans. Pharmaceutical substances can be obtained by a personal prescription or by other means.

People experiencing homelessness: People experiencing a range of physical living conditions including living on a street or place that is not intended for human habitation (e.g. park, car, sidewalk), staying at an overnight shelter, and staying in temporary accommodations (e.g. motels, with friends, family or couch surfing, temporary housing for immigrants and refugees during settlement) Footnote 15. For the data included in this report, homelessness status upon admission to hospital was mandatory to capture using the ICD-10-CAFootnote a code "Z59.0". Coders are instructed to capture homelessness status when it is mentioned in physician documentation or when it is noted on routine review of the medical record.

People with housing: People who are securely housed upon admission to hospital, identified by no presence of the ICD-10-CA code "Z59.0" on their record.

For more information on these definitions, please refer to the technical notes and appendices.

Key Findings

Substance-related poisoning hospitalizations among people experiencing homelessness

Between April 2019 and March 2020, in Canada (excluding Québec), there were 10,659 substance-related poisoning hospitalizations. Of those, approximately 6% (n=623) were among people experiencing homelessness on admission.

Sex and age

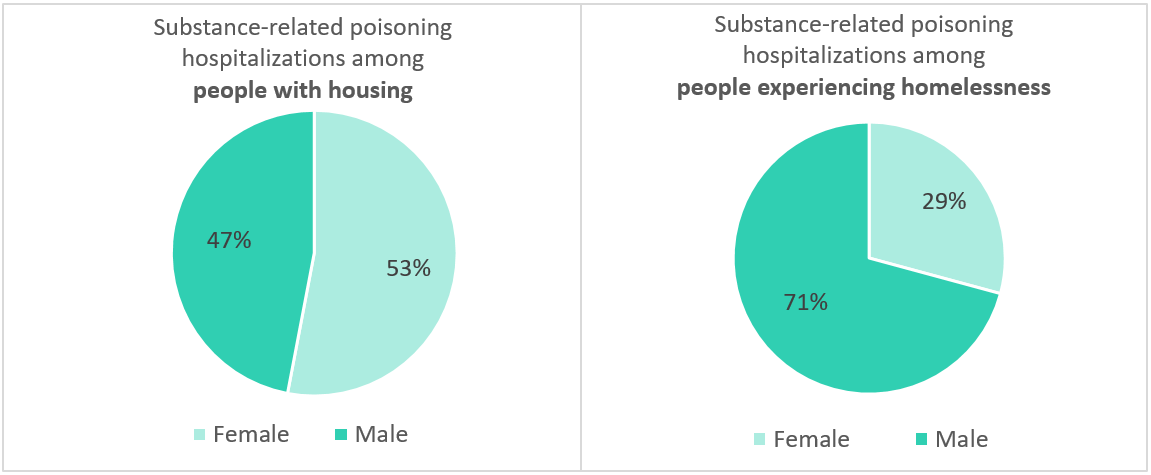

The majority of substance-related poisoning hospitalizations for people experiencing homelessness were among males (71%). This may reflect the higher proportion of men who experience homelessness Footnote 2, males experiencing higher rates of substance use disorders compared to females Footnote 16, in addition to potentially more women experiencing hidden homelessness Footnote 17. In contrast, a more even distribution of substance-related poisonings was observed between males (47%) and females (53%) among people with housing (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Text Equivalent

| Substance-related poisoning hospitalization | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| % (N) | % (N) | |

| People with housing | 47% (4,715) | 53% (5,316) |

| People experiencing homelessness | 71% (441) | 29% (182) |

Data source |

||

Note(s) |

||

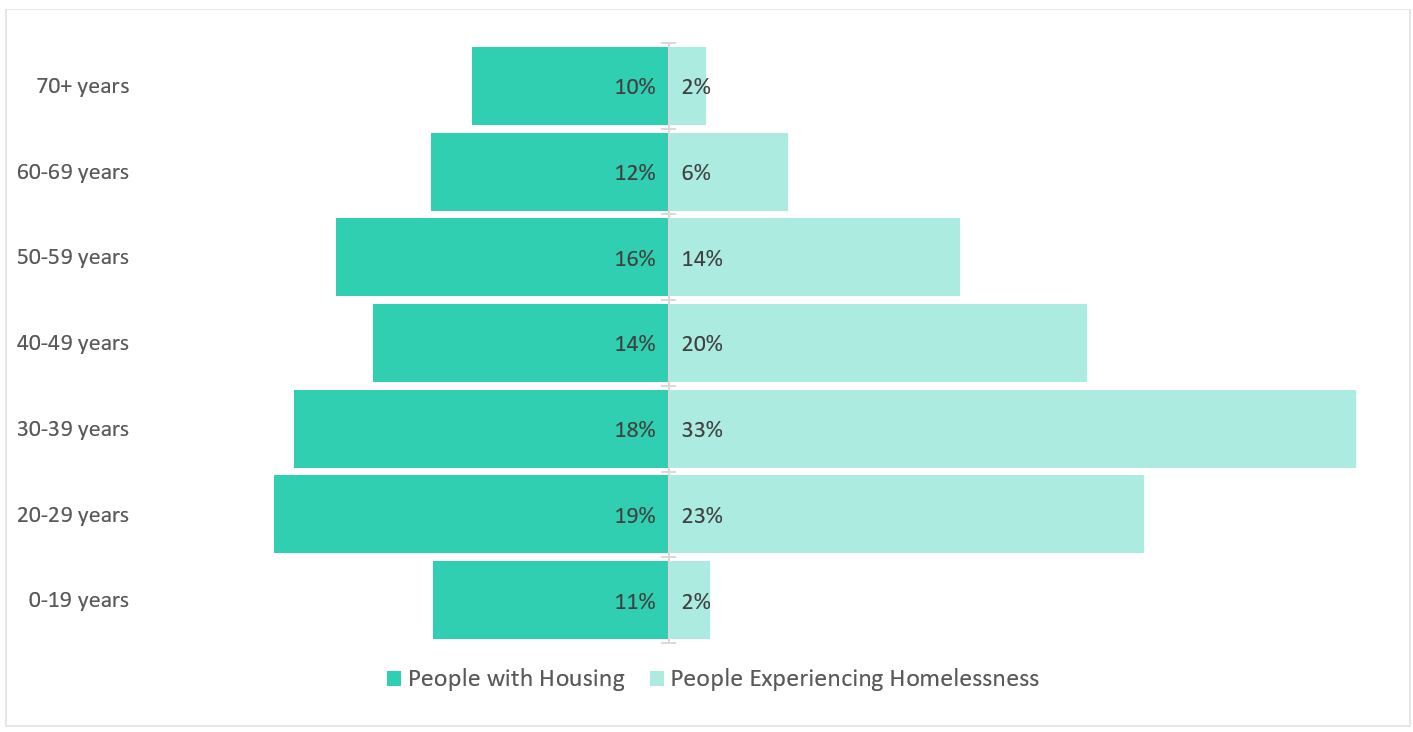

Among those who were experiencing homelessness, most substance-related poisoning hospitalizations occurred in the 20-29 (23%), 30-39 (33%) and 40-49 (20%) age groups (Figure 2). In contrast, among people with housing, there was a more even distribution across age groups from 20-29 to 70+ years. This may reflect the relatively younger population among those experiencing homelessness Footnote 18.

Figure 2 - Text Equivalent

| Substance-related poisoning hospitalization | 0-19 Years | 20-29 Years | 30-39 Years | 40-49 Years | 50-59 Years | 60-69 Years | 70+ Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | |

| People with housing | 11% (1,146) | 19% (1,915) | 18% (1,819) | 14% (1,435) | 16% (1,619) | 11% (1,149) | 9% (953) |

| People experiencing homelessness | 2% (12) | 23% (143) | 33% (207) | 20% (126) | 14% (88) | 6% (36) | 2% (11) |

Data source |

|||||||

Generally, among hospitalizations for substance-related poisonings, people experiencing homelessness were younger compared to people with housing. The median age for people experiencing homelessness was 37 years (mean = 39), while the median age for people with housing was 40 years (mean = 43).

Hospitalization characteristics and outcomes

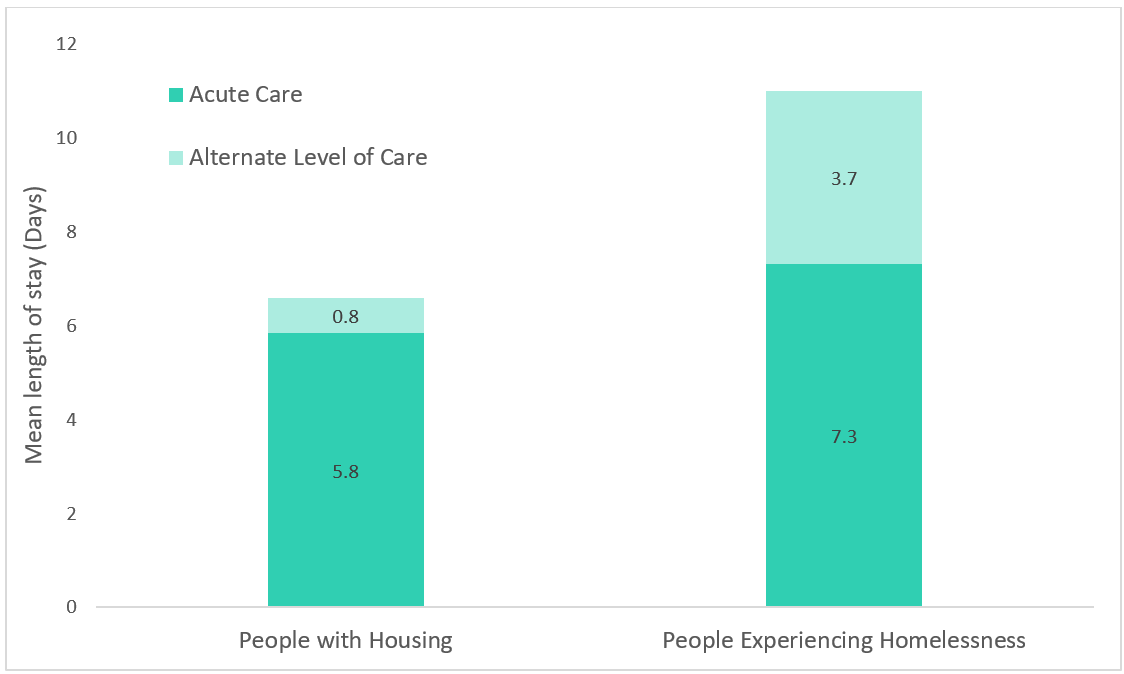

Length of stay

When examining the length of stay in hospital among people with housing and people experiencing homelessness, a substantial difference was observed (Figure 3). The total length of stay in hospital adds the number of days a patient was in acute inpatient care (patients receiving necessary treatment for a disease or severe episode of illness for a short period) and alternate level of care (patients occupying a bed but not requiring the intensity of services provided in that care setting) Footnote 19Footnote 20. Overall, the average total length of stay in hospital for a substance-related poisoning was longer among people experiencing homelessness. People experiencing homelessness hospitalized for substance-related poisonings spent an average of 7.3 days in acute inpatient care and 3.7 days in alternate level of care, for a total of 11.0 days spent in hospital. In comparison, people with housing hospitalized for substance-related poisonings spent an average of 5.8 days in acute inpatient care and 0.8 days in alternate level of care, for a total of 6.6 days spent in hospital. Please see Appendix A for information regarding median length of stay.

Figure 3 - Text Equivalent

| Substance-related poisoning hospitalization | Mean length of stay in acute inpatient care | Mean length of stay in alternate level of care | Mean total length of stay |

|---|---|---|---|

| People with housing | 5.8 | 0.8 | 6.6 |

| People experiencing homelessness | 7.3 | 3.7 | 11.0 |

Data source |

|||

Intensive care unit admission

The Intensive Care Unit (ICU) is an organized system to provide specialized medical care to patients who are critically ill, and allow for enhanced monitoring and life support Footnote 21. This care could involve mechanical ventilation to help a person breathe if they are unable to do so on their own. A similar proportion of hospitalizations were admitted to the ICU when comparing people with housing and people experiencing homelessness with a substance-related poisoning. Among people experiencing homelessness, 38% were admitted to the ICU compared to 36% of people with housing.

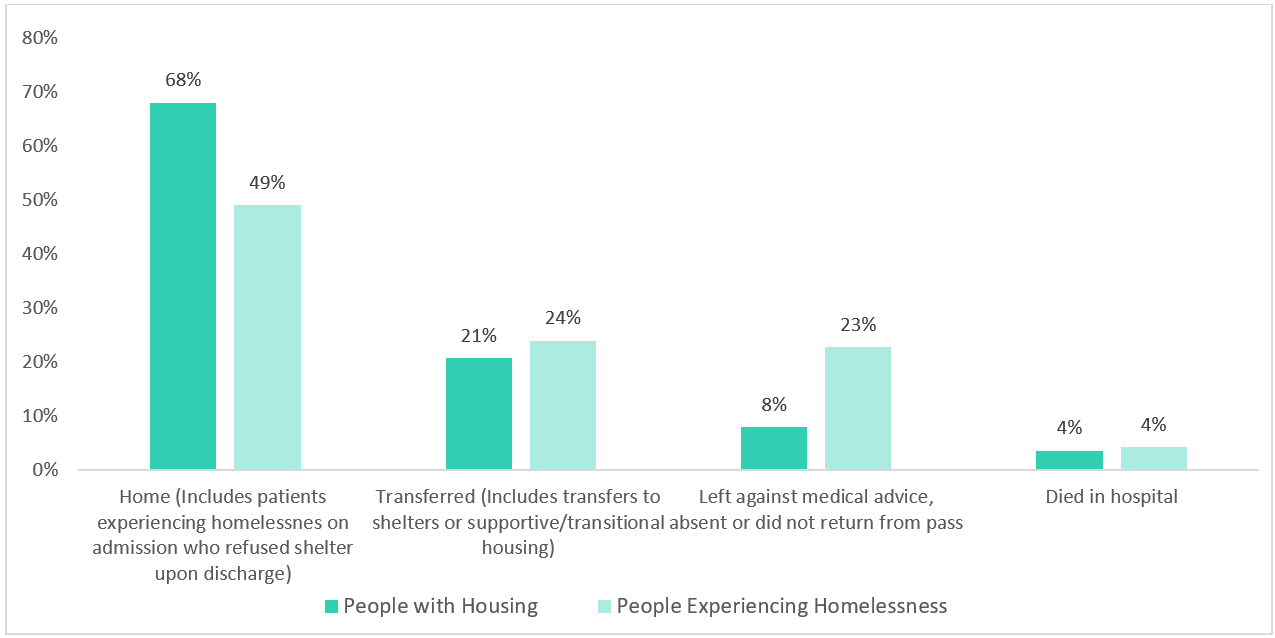

Discharge disposition

Discharge disposition describes the status of the patient on discharge or where the patient was discharged to, and varies between people with housing and people experiencing homelessness (Figure 4). A notable difference was observed in the proportion who left the hospital against medical advice. For substance-related poisonings among people with housing, 8% left the hospital against medical advice. In comparison, for substance-related poisonings among people experiencing homelessness, almost a quarter (23%) left the hospital against medical advice. Patients who leave against medical advice may not have received all of the medical care or supports available.

The majority (68%) of substance-related poisoning hospitalizations among people with housing indicated that the patient was discharged home. In comparison, 49% among people experiencing homelessness were "discharged home". However, it is important to note this category also includes patients who were experiencing homelessness on admission and refused shelter upon discharge, as there was not a value to capture this concept in the data. As a result, "home" in these instances could refer to discharging a patient to living on a street or place that is not intended for human habitation (e.g., park, car, sidewalk).

A similar percentage of substance-related poisoning hospitalizations among people with housing (21%) and people experiencing homelessness (24%) resulted in the patient being transferred, for instance, to a specialty hospital for inpatient rehabilitation, mental health or addiction treatment centre, long-term care, shelter or assisted living with supportive housing. Upon examining those who fall within this category further, 12% of people experiencing homelessness were transferred to a shelter, compared to only 3% of people with housing on admission.

No differences were observed between those with housing and those experiencing homelessness for deaths occurring in hospital.

Figure 4 - Text Equivalent

| Substance-related poisoning hospitalization | Home (includes patients experiencing homelessness on admission who refuse shelter upon discharge) | Transferred (includes transfers to shelters or supportive/transitional housing) | Left against medical advice absent or did not return from pass | Died in hospital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | |

| People with housing | 68% (6,829) | 21% (2,069) | 8% (786) | 4% (352) |

| People experiencing homelessness | 49% (306) | 24% (149) | 23% (142) | 4% (26) |

Data source |

||||

Note(s) |

||||

Substances involved and intentionality

Type of substance(s) involved

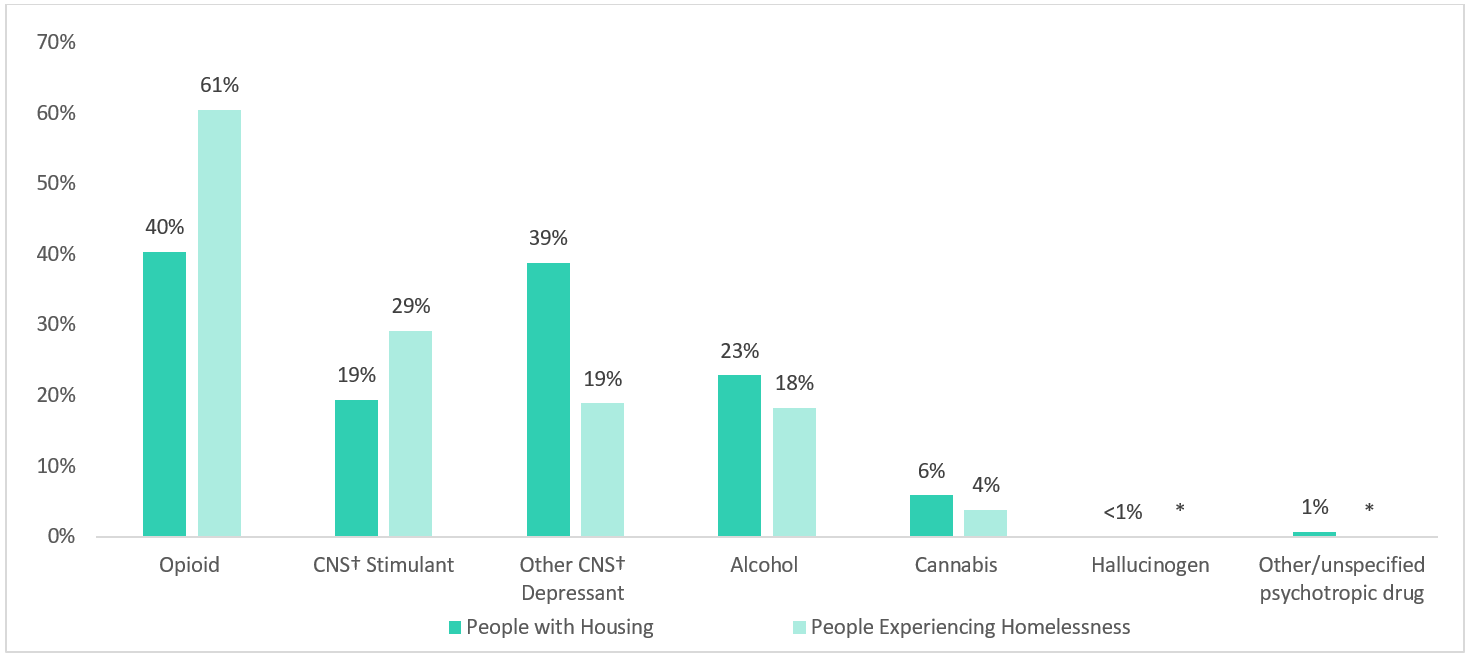

Differences were observed when examining the substance(s) involved in the poisoning for people with housing and people experiencing homelessness (Figure 5). For substance-related poisoning hospitalizations among people experiencing homelessness, opioids were the most common type of substance involved. Opioids were present in 61% of poisoning hospitalizations among people experiencing homelessness and in 40% of poisoning hospitalizations among people with housing. Stimulants (e.g., methamphetamine) were also involved in a greater percentage of substance-related poisoning hospitalizations among people experiencing homelessness (29%) than among people with housing (19%). Overall, for substance-related poisoning hospitalizations among people with housing, cannabis, alcohol and other central nervous system depressants (e.g., benzodiazepines and other sedatives) were more commonly involved compared to people experiencing homelessness. Of note, multiple types of substances may be involved in any given poisoning and therefore percentages will not add up to 100%. Refer to the technical notes and Appendix B for the methodology used to identify types of substance-related poisoning hospitalizations.

Figure 5 - Text Equivalent

| Substance-related poisoning hospitalization | Opioid | CNS† Stimulant | Other CNS† Depressant | Alcohol | Cannabis | Hallucinogen | Other/unspecified psychotropic drug |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | |

| People with housing | 40% (4,056) | 19% (1,953) | 39% (3,897) | 23% (2,300) | 6% (594) | <1% (35) | 1% (67) |

| People experiencing homelessness | 61% (377) | 29% (182) | 19% (118) | 18% (114) | 4% (24) | Suppressed | Suppressed |

Data source |

|||||||

Note(s) |

|||||||

Type of opioid(s) involved

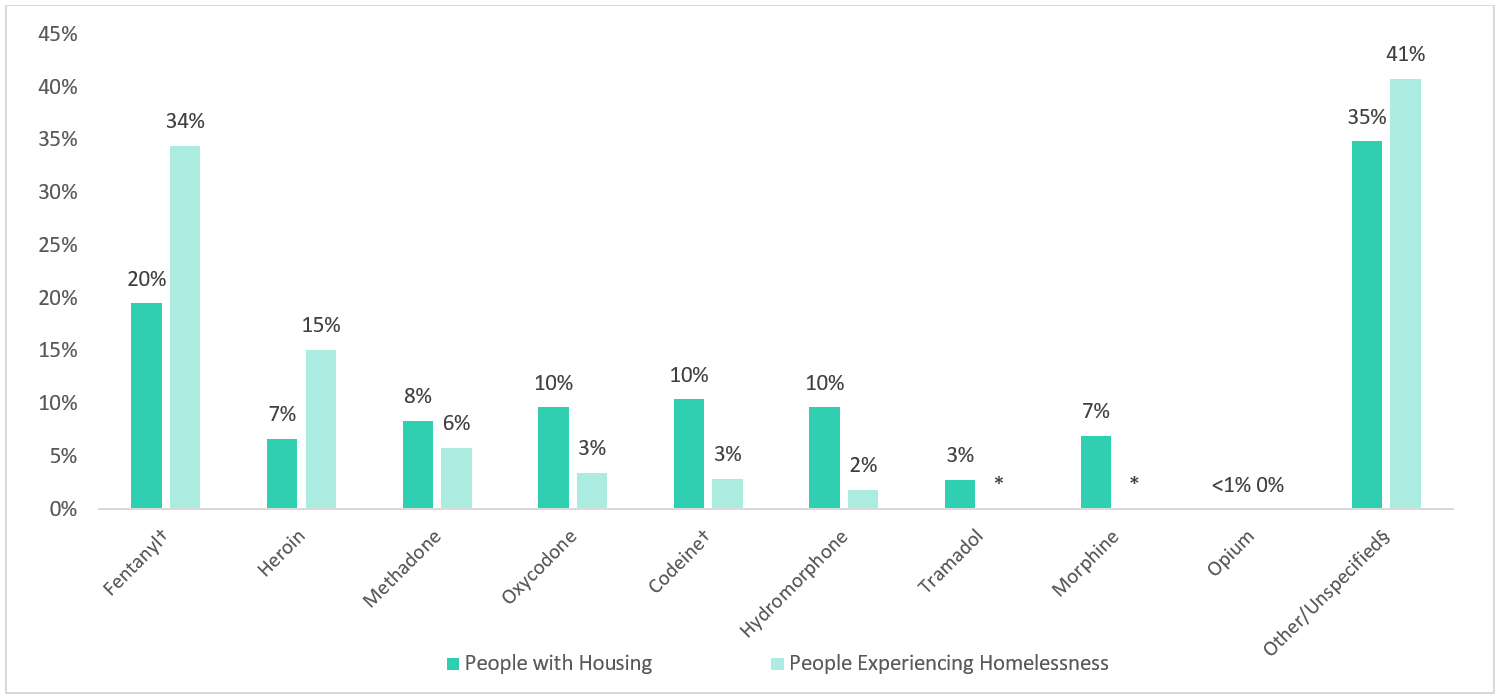

Overall, the opioid(s) involved in the substance-related poisoning hospitalization differed between people with housing and people experiencing homelessness (Figure 6). Most notably, among people experiencing homelessness, 34% of opioid-related poisoning hospitalizations involved fentanyl and its analogues, whereas 20% of such hospitalizations were observed among people with housing. Heroin was also involved in a greater proportion of opioid-related poisoning hospitalizations among people experiencing homelessness than among people with housing, at 15% and 7% respectively. While fentanyl and heroin were most commonly observed among opioid-related hospitalizations for people experiencing homelessness, other opioid types were more prevalent among people with housing. In particular, tramadol, methadone, oxycodone, hydromorphone, morphine, opium and codeine were more commonly involved among people with housing. Of note, the category for other/unspecified opioids represented the highest proportion for both people with housing and people experiencing homelessness. This finding may reflect further confirmatory testing to distinguish the specific type of opioid being unavailable or not necessary for treatment, new and emerging substances not being captured in the toxicology screen, or an inability or unwillingness of the patient to disclose the substance used.

It was not possible to determine which poisonings were a result of pharmaceutical opioids, non-pharmaceutical opioids, or a combination of both. Multiple types of opioids may be involved in any given poisoning and therefore percentages will not add up to 100%. Refer to the technical notes and Appendix B for the methodology used to identify types of opioid-related poisonings.

Figure 6 - Text Equivalent

| Substance-related poisoning hospitalization | Fentanyl† | Heroin | Methadone | Oxycodone | Codeine† | Hydromorphone | Tramadol | Morphine | Opium | Other/Unspecified§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | |

| People with housing | 20% (792) | 7% (272) | 8% (341) | 10% (393) | 10% (424) | 10% (393) | 3% (115) | 7% (284) | <1% (8) | 35% (1,415) |

| People experiencing homelessness | 34% (130) | 15% (57) | 6% (22) | 3% (13) | 3% (11) | 2% (7) | Suppressed | Suppressed | 0% (0) | 41% (154) |

Data source |

||||||||||

Note(s) |

||||||||||

Multiple substance poisoning

Substance-related poisoning hospitalizations which involved more than one substance were relatively similar among people with housing and people experiencing homelessness. The involvement of only one substance of interest accounted for 77% of all substance-related poisoning hospitalizations among people with housing, and 74% of all substance-related poisoning hospitalizations among people experiencing homelessness. For people with housing, 19% of substance-related poisoning hospitalizations involved two substances and 5% of substance-related poisoning hospitalizations involved three or more substances. Similarly, for people experiencing homelessness, 20% of substance-related poisoning hospitalizations involved two substances and 5% of substance-related poisoning hospitalizations involved three or more substances. Of note, the following substance types were explored for the multiple poisoning analysis: opioids, stimulants, cannabis, hallucinogens, alcohol, other depressants, and psychotropic drugs. Substances outside of this scope, for example poisonings that also involved anti-depressants, are not reported.

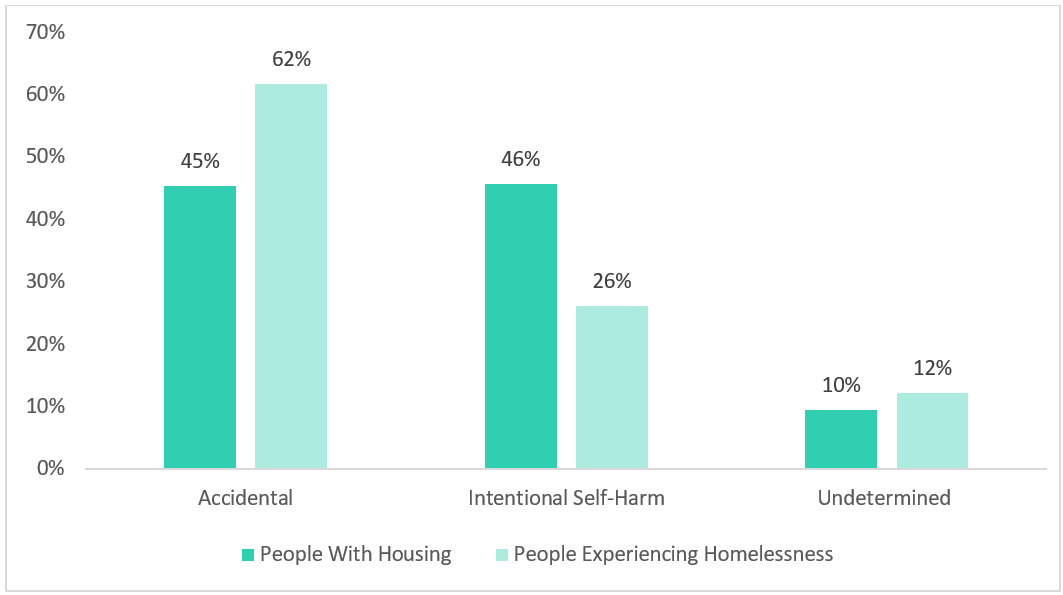

Intention

Intention refers to the documented reason for the poisoning, which may rely on self-report, and is classified as accidental, intentional self-harm and undetermined. Definitions and methodology are in the technical notes and Appendix C. People experiencing homelessness had a higher proportion of substance-related poisoning hospitalizations recorded to be accidental in nature compared to people with housing, 62% vs. 45% respectively (Figure 7). Conversely, people with housing had a higher proportion of substance-related poisoning hospitalizations recorded to be intentional self-harm compared to people experiencing homelessness, 46% vs. 26% respectively. Similar proportions were observed for substance-related poisoning hospitalizations of undetermined intention between people experiencing homelessness and people with housing.

Figure 7 - Text Equivalent

| Intention for the poisoning | Accidental | Intentional self-harm | Undetermined |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | |

| People with housing | 45% (4,519) | 46% (4,551) | 10% (949) |

| People experiencing homelessness | 62% (382) | 26% (162) | 12% (76) |

Data source |

|||

Note(s) |

|||

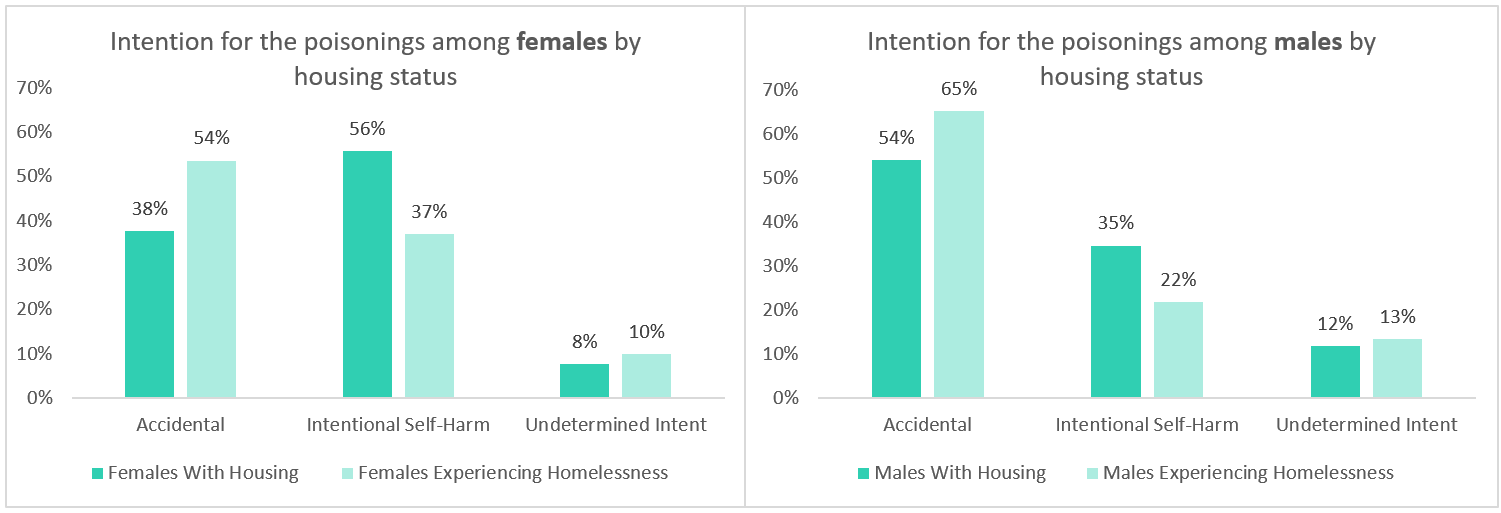

Intention by sex

Among males, accidental substance-related poisoning hospitalizations were most common for both people with housing (54%) and people experiencing homelessness (65%). Among females with housing, intentional substance-related poisoning hospitalizations were most common (56%), while for females experiencing homelessness, accidental substance-related poisoning hospitalizations were most common (54%) (Figure 8).

Figure 8 - Text Equivalent

| Intention for poisoning | Accidental | Intentional self-harm | Undetermined |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | |

| Females with housing | 38% (1,986) | 56% (2,928) | 8% (398) |

| Females experiencing homelessness | 54% (97) | 37% (67) | 10% (18) |

| Males with housing | 54% (2,532) | 35% (1,620) | 12% (550) |

| Males experiencing homelessness | 65% (285) | 22% (95) | 13% (58) |

Data source |

|||

Note(s) |

|||

Co-Diagnosed Mental Health Conditions

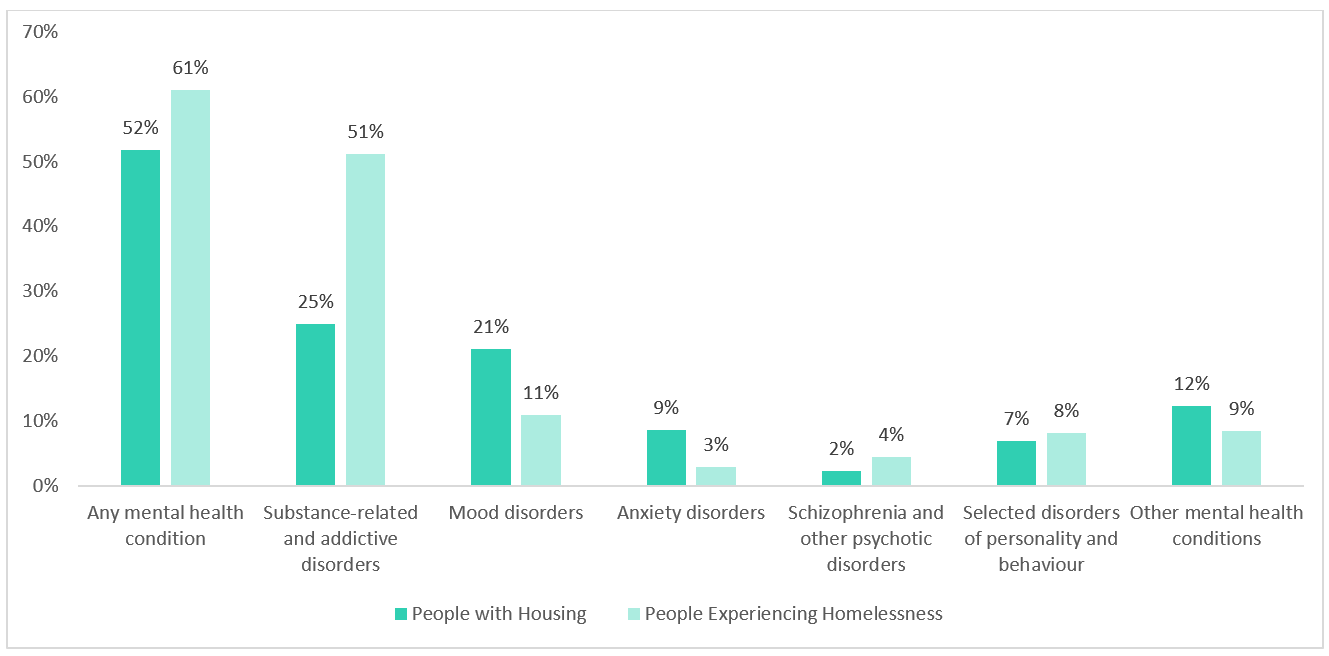

Records were explored for co-diagnoses of mental health conditions (referred to as mental disorders in the ICD-10-CA) during the hospital stay for the poisoning; more detailed definitions and methodology are available in the technical notes and Appendix D. The presence of co-diagnosed mental health conditions during the hospital stay for a substance-related poisoning was high among both people with housing and people experiencing homelessness. However, people experiencing homelessness had a higher proportion of mental health conditions recorded during their hospital stay compared to people with housing, at 61% vs. 52% respectively (Figure 9).

The most commonly documented co-diagnosed mental health conditions for both people experiencing homelessness and people with housing were substance-related and addictive disorders and mood disorders, however patterns within these categories varied. People experiencing homelessness had more than double the proportion of co-diagnosed substance-related and addictive disorders compared to people with housing (51% vs. 25% respectively). People with housing had a substantially higher proportion of co-diagnosed mood disorders compared to people experiencing homelessness (21% vs. 11% respectively). People with housing also had a higher proportion of co-diagnosed anxiety disorders (9% as compared to 3%). While less frequent, 2% among people with housing and 4% among people experiencing homelessness had a co-diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders during their hospital stay. Patterns for other mental health condition categories were more similar by housing status.

Figure 9 - Text Equivalent

| Co-diagnosed mental health conditions | Any mental health condition | Substance-related and addictive disorders | Mood disorders | Anxiety disorders | Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders | Selected disorders of personality and behavior | Other mental health conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | |

| People with housing | 52% (5,196) | 25% (2,509) | 21% (2,122) | 9% (865) | 2% (236) | 7% (694) | 12% (1,232) |

| People experiencing homelessness | 61% (380) | 51% (319) | 11% (68) | 3% (18) | 4% (28) | 8% (51) | 9% (53) |

Data source |

|||||||

Note(s) |

|||||||

In Summary

Canada continues to experience an overdose crisis and data has shown that substance-related harms and deaths continue to be of great concern Footnote 5. Furthering our understanding of substance-related harms, including the demographics, context, and implications among specific populations, is essential to inform the implementation of evidence-based clinical and public health actions, harm reduction strategies, and social services.

This report found that approximately 6% of hospitalizations for substance-related poisonings (that were primarily from opioids, stimulants, cannabis, alcohol, and other depressants) across the country were among people experiencing homelessness. When compared to people with secure housing, hospitalizations for substance-related poisonings among people experiencing homelessness had a higher proportion of:

- Males

- Younger individuals

- Poisonings which were accidental in nature

- Poisonings due to opioids and stimulants, notably involving fentanyl and heroin

- Recorded mental health conditions, mainly for substance-related and addictive disorders

- Hospital stays ending by leaving against medical advice before being formally discharged by a health care professional

Additionally, compared to people with secure housing, people experiencing homelessness:

- Had lengthier stays in hospital and stayed four days longer on average

These findings are highlighted for healthcare professionals, researchers, and policy makers to better understand the intersection of homelessness, mental health, and substance-related harms and can be used to inform sectors that interact with people experiencing homelessness. In particular, these findings demonstrate how substance-related harms may differ among people with housing and people experiencing homelessness. Care in hospital settings may also be experienced differently among people experiencing homelessness as they had a higher proportion of substance-related poisoning hospitalizations which ended by leaving against medical advice. This may be due to a variety of factors, such as care not meeting the needs of this population or due to a lack of trust or stigma, and warrants further investigation to reduce barriers to care for people experiencing homelessness.

It is important to note that at the time of this analysis, homelessness status was only mandatory to record upon admission to hospital, and therefore the data presented in this report is likely an underestimate, as it may not reflect people who are experiencing homelessness upon discharge. Additional research is needed to better understand the causes and consequences of substance-related harms among people experiencing homelessness, but also among other populations that are disproportionally affected by substance use, such as LGBTQ2+ populations, racialized populations, and Indigenous Peoples Footnote 22Footnote 23. The Government of Canada will continue to improve data and analysis to inform strategies and interventions to reduce substance-related harms across Canada.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) for collecting and providing the data used in this report.

Disclaimer

Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI).

Suggested Citation

Substance-related poisonings and homelessness in Canada: a descriptive analysis of hospitalization data. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; June 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/opioids/hospitalizations-substance-related-poisonings-homelessness.html

Technical notes

Methodology

Data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information's (CIHI) Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) for the fiscal year April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020 were analyzed for this descriptive report. This analysis was limited to acute inpatient hospital discharges, which are nationally representative across Canada, except for Quebec. This analysis presents the number of acute inpatient hospital discharges for substance-related poisonings; it does not reflect the number of patients who were hospitalized in the analysis year. It is possible some patients may have been hospitalized more than once for a substance-related poisoning.

The International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Canada (ICD-10-CA) is used in the DAD to capture diagnoses from the patient's hospitalization. It is the national standard for reporting morbidity statistics. More information on the DAD and ICD-10-CA coding can be found on CIHI's website.

The methodology for identifying substance-related poisonings in this report was adapted from CIHI's Opioid-related Harms in Canada report and Hospital Stays for Harm Caused by Substance Use indicator. The methodology for identifying homelessness was followed as per the Canadian Coding Standards directives for version 2018 ICD-10-CA. The methodology for identifying co-diagnosed mental health conditions was adapted from CIHI's indicator for Repeat Hospital Stays for Mental Illness.

Identifying substance-related poisonings

A complete listing of all ICD-10-CA diagnosis codes used to identify substance-related poisonings presented in this report can be found in Appendix B. Of note, poisonings from the following substances of interest were included in the scope of this analysis: opioids, stimulants, cannabis, hallucinogens, alcohol, other depressants, and psychotropic drugs. Information on these substance-related poisonings are extracted from patient charts by trained coders, which may be based on toxicological analysis and/or patient self-report.

For substance-related poisonings, analyses were restricted to the following significant diagnosis types:

- Most responsible diagnosis ("M")

- Pre-admit comorbidity ("1")

- Post-admit comorbidity ("2")

- Service transfer diagnosis ("W", "X", and "Y")

These significant diagnosis types capture hospitalizations in which the substance-related harm poisoning was considered influential to the time spent and treatment received by the patient in hospital. Secondary diagnoses that do not meet the criteria for significance (diagnosis type 3) were excluded.

A diagnosis prefix of "Q", indicating unconfirmed diagnoses or query diagnoses recorded by the physician, were excluded from these analyses as the scope of the analysis was concerned with confirmed cases of poisonings only. Records indicating the patient was admitted to the facility as a cadaveric donor and stillbirths were also excluded.

Identifying intention of poisoning

When a patient experiences a poisoning, coders are directed to assign an external cause ICD-10-CA code to indicate the intention (i.e., reason) for the poisoning. Each substance-related poisoning of interest for this analysis was further examined by the documented intention for the poisoning, and classified in the following three groups in line with the Intentional Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Canada:

- Accidental: A substance-related poisoning hospitalization that is considered to be non-intentional in nature and is identified by an associated external cause ICD-10-CA code of X41, X42, or X45.

- Intentional: A substance-related poisoning hospitalization that occurred as a result of purposely self-inflicted harm and is identified by an associated external cause ICD-10-CA code of X61, X62, or X65.

- Undetermined: A substance-related poisoning hospitalization which has been documented to be of undetermined/unknown intention and is identified by an associated external cause ICD-10-CA code of Y11, Y12, or Y15.

In line with CIHI coding standards, a diagnosis type of "9" was used to identify intention using external cause codes. External cause codes are mandatory to assign with codes within the range S00-T98 Injury, poisoning, and certain other consequences of external causes. All poisonings captured in this report fall within this range, however a small number of records contained poisonings that were found to be missing associated external cause codes and therefore it was not possible to determine the intention for these. Hospital records where one or more poisonings were missing an associated external cause code to determine intention were excluded from the intention analysis, but were included in all other analyses. In total, 102 records were missing complete codes to determine the intention of the poisoning and excluded from the intention analyses.

External cause codes for intention with a diagnosis prefix of "Q", indicating unconfirmed diagnoses or query diagnoses, were included when identifying intention as the scope of this analysis was concerned with capturing suspected diagnoses for intention.

A list of all substance-related poisoning types of interest for this analysis and their associated intention codes can be found in Appendix C.

Identifying homelessness

The ICD-10-CA code of "Z59.0 - Homelessness" was used to identify homelessness status upon admission to hospital. Substance-related poisoning records with and without a corresponding ICD-10-CA code of "Z59.0 - Homelessness", were identified to create two groups for analyses:

1) Substance-related poisoning hospitalizations among people experiencing homelessness and;

2) Substance-related poisoning hospitalizations among people with housing.

When examining recorded homelessness during the patient's substance-related poisoning hospitalization, the following diagnosis types were included:

- Most responsible diagnosis ("M")

- Pre-admit comorbidity ("1")

- Post-admit comorbidity ("2")

- Secondary diagnosis ("3")

- Service transfer diagnosis ("W", "X", "Y")

Of note, diagnosis types of "3" were included as the scope of this analysis was concerned with capturing secondary diagnoses for homelessness as per CIHI coding directives. Unconfirmed diagnoses or query diagnoses, with a diagnosis prefix of "Q", were included when identifying homelessness as the scope of this analysis was also concerned with capturing suspected diagnoses for homelessness.

Identifying co-diagnosed mental health conditions

Specific examples of diagnoses included in each mental health condition category reported and associated ICD-10-CA codes can be found in Appendix D. When examining recorded co-diagnoses of mental health conditions (referred to as mental disorders in the ICD-10-CA) during the patient's substance-related poisoning hospital stay, the following diagnosis types were included:

- Most responsible diagnosis ("M")

- Pre-admit comorbidity ("1")

- Post-admit comorbidity ("2")

- Secondary diagnosis ("3")

- Service transfer diagnosis ("W", "X", "Y")

Of note, diagnosis types of "3" were included as the scope of this analysis was concerned with capturing secondary diagnoses for mental health conditions.

Unconfirmed diagnoses or query diagnoses (with a diagnosis prefix of "Q") were included when identifying mental health conditions as the scope of this analysis was also concerned with capturing suspected diagnoses for mental health conditions.

Recording diagnoses of mental health conditions is mandatory if the mental health condition(s):

- significantly affects the treatment received

- requires treatment beyond maintenance of the pre-existing condition, or

- increases the length of stay in hospital by at least 24 hours.

Therefore, the data presented in this report does not reflect the overall prevalence of mental health conditions among those hospitalized for substance-related poisonings, but rather mental health conditions that were deemed relevant to the patient's hospital stay.

Limitations

General notes

- This analysis is descriptive in nature and while it will report differences in demographics, context of poisoning, and hospital characteristics, it does not evaluate why these differences occur.

- It was not possible to determine which poisonings, if applicable, were a result of pharmaceutical substances, non-pharmaceutical substances, or a combination of both. It was also not possible to determine whether co-poisonings were a result of intended use of multiple substances at the same time or close in time, or if a substance unknowingly contained other substances.

- The DAD captures patients discharged from hospital. Patients who were still hospitalized during the analysis year are not captured in this report.

- The terminology used in this report aligns with the terms used in the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Canada (ICD-10-CA).

- This analysis does not include data from the province of Quebec.

- Data released by provinces and territories may differ from the data provided in this report due to the availability of updated data, differences in the type of data reported, the use of alternate age groupings, differences in time periods presented and/or population estimates used for calculations, etc.

Data on sex

- At the time of this analysis, no data was available in relation to gender identity. In the DAD, data on sex is typically recorded based on biological determination or legal documentation. Although an 'other' sex group was available, the counts were too low to include in this report. Therefore, the 'other' sex group was retained in the overall analyses, but excluded from all analyses by sex to avoid disclosure.

Data on homelessness

- The ICD-10-CA code used to identify people experiencing homelessness (Z59.0) is mandatory to capture individuals who are experiencing homelessness upon admission to hospital. Patients who were newly experiencing homelessness upon discharge from hospital but not homeless on admission, may not have been captured. A new coding direction, effective on April 1, 2021, specifies it is mandatory to code Z59.0 for patients who are experiencing homelessness whenever documented (e.g., on admission, during admission) Footnote 24. As coverage improves, this analysis should be repeated.

- Homelessness status can rely on self-reported information. It is possible some patients may have not disclosed they were experiencing homelessness, or were not able to do so due to disability or death. As a result, these instances of "hidden homelessness" may have been falsely classified to the "people with housing" group.

- It's important to note that even though an individual may be housed, they could be experiencing housing insecurity. It was not possible to examine other factors, such as unstable housing, poor housing quality or overcrowding.

Data on intention

- Poisonings are classified as accidental unless there is clear documentation of intentional self-harm or undetermined intention. This may reflect an overrepresentation of accidental poisonings.

- Determining intention can rely on self-reported information which patients may not be willing to disclose due to various reasons, or unable to due to disability or death.

Data on mental health conditions

- Co-diagnoses of mental health conditions in this report do not reflect the overall prevalence of mental health conditions among those hospitalized for substance-related poisonings, but rather mental health conditions that were recorded/deemed relevant to the patient's stay in hospital. Mental health conditions can go undiagnosed, or take time to diagnose, and these instances would not be captured in this data.

Data suppression

Values representing less than five hospitalizations are suppressed according to CIHI's privacy guidelines.

Appendix A

Median length of stay in acute inpatient care and alternate level of care (ALC) among people with housing and people experiencing homelessness

| Housing status | Level of care | Median length of stay in hospital |

|---|---|---|

| People with housing | Acute inpatient care | 2 days |

| Alternate level of care | 0 days | |

| Total care | 2 days | |

| People experiencing homelessness | Acute inpatient care | 3 days |

| Alternate level of care | 0 days | |

| Total care | 3 days |

Appendix B

List of ICD-10-CA codes used to identify substance-related poisoning hospitalizations

| Poisoning from substance | ICD-10-CA code and descriptions |

|---|---|

| Alcohol | T51- Toxic effect of alcohol |

| Cannabis | T40.7 Poisoning by cannabis (derivatives) |

| Other central nervous system (CNS) depressants |

T42.3 Poisoning by barbiturates T42.4 Poisoning by benzodiazepines T42.6 Poisoning by other antiepileptic and sedative-hypnotic drugs T42.7 Poisoning by other antiepileptic and sedative - hypnotic drugs, unspecified |

| Central nervous system (CNS) stimulants |

T40.5 Poisoning by cocaine T43.6 Poisoning by psychostimulants with abuse potential (excludes cocaine) Note: this category includes poisonings from methamphetamine |

| Hallucinogens | T40.8 Poisoning by lysergide (LSD) T40.9 Poisoning by other and unspecified psychodysleptics (hallucinogens) |

| Opioids | T40.0 Poisoning by opium T40.1 Poisoning by heroin T40.2 Poisoning by other opioids T40.20 Poisoning by codeine and derivatives T40.21 Poisoning by morphine T40.22 Poisoning by hydromorphone T40.23 Poisoning by oxycodone T40.28 Poisoning by other opioids not elsewhere classified* T40.3 Poisoning by methadone T40.4 Poisoning by other synthetic narcotics T40.40 Poisoning by fentanyl and derivatives T40.41 Poisoning by tramadol T40.48 Poisoning by other synthetic narcotics not elsewhere classified* T40.6 Poisoning by other and unspecified narcotics* |

| Other/unspecified psychotropic drug |

T43.8 Poisoning by other psychotropic drugs, not elsewhere classified T43.9 Poisoning by psychotropic drug, unspecified |

* Grouped together as "other/unspecified" opioid category.

Appendix C

Associated ICD-10-CA codes used to identify intention for poisonings

| ICD-10-CA poisoning codes | Associated ICD-10-CA intention codes (i.e., external cause codes) |

|---|---|

| Other central nervous system depressants (T42.3, T42.4, T42.6, T42.7) Poisoning by psychostimulants with abuse potential (T43.6) Other/unspecified psychotropic drugs (T43.8, T43.9) |

Accidental: X41 Intentional: X61 Undetermined: Y11 |

| Opioids (T40.0, T40.1, T40.2-, T40.3, T40.4-, T40.6) Cocaine (T40.5) Cannabis (T40.7) Hallucinogens (T40.8, T40.9) |

Accidental: X42 Intentional: X62 Undetermined: Y12 |

| Alcohol (T51-) | Accidental: X45 Intentional: X65 Undetermined:Y15 |

Appendix D

Examples of specific diagnoses captured in mental health condition categories and associated ICD-10-CA codes

| Mental health condition category and ICD-10-CA codes | Examples of specific mental health condition diagnoses (not an exhaustive list) |

|---|---|

| Substance-related and addictive disorders (F10-F19, F55, F63.0) |

Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of alcohol, cannabinoids, cocaine, other stimulants, sedatives or hallucinogens. Pathological gambling. |

| Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (F20, F21, F22, F23, F24, F25, F28, F29) |

Schizophrenia, schizotypal disorders, psychotic disorders, induced delusional disorders, and schizoaffective disorders |

| Mood disorders (F30, F31, F32, F33, F34, F38, F39, F53.0, F53.1) |

Manic episodes, bipolar affective disorders, and depressive disorders |

| Anxiety disorders (F40, F41, F93.0, F93.1, F93.2, F94.0) |

Phobic anxiety disorders, panic disorders, generalized anxiety disorders, and separation anxiety disorders |

| Selected disorders of personality and behaviour (F60, F61, F62, F68 (excluding F68.1), F69) |

Paranoid personality disorders, schizoid personality disorders, dissocial personality disorders, and emotionally unstable personality disorders |

| Other mental health conditions (F42, F43, F44, F45, F48.0, F48.1, F48.8, F48.9, F50, F51, F52, F53.8, F53.9, F54, F59, F63 (excluding F63.0), F68.1, F90, F91, F92, F93.3, F93.8, F93.9, F94.1, F94.2, F94.8, F94.9, F95, F98.0, F98.1, F98.2, F98.3, F98.4, F98.5, F98.8, F98.9, F99, O99.3) |

Somatoform disorders including hypochondria disorders, eating disorders, nonorganic sleep disorders, conduct disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorders |

More detailed information regarding the diagnosis codes included in this report can be found in CIHI's version 2018 ICD-10-CA manual. More general information on ICD-10 can be found in the World Health Organizations ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. The World Health Organization also provides a list of key terms and definitions in mental health as a reference.

References

- Footnote a

-

International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Canada (ICD-10-CA).

- Footnote 1

-

Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms in Canada [Internet]. Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms in Canada - Public Health Infobase | Public Health Agency of Canada; 2021 [cited 2021Feb1]. Available from: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants#hospSection

- Footnote 2

-

Gaetz S, Dej E, Richter T, Redman M. The state of homelessness in Canada 2016. Toronto.

- Footnote 3

-

Strobel S, Burcul I, Dai JH, Ma Z, Jamani S, Hossain R. Characterizing people experiencing homelessness and trends in homelessness using population-level emergency department visit data in Ontario, Canada. Health Reports. 2021 Jan 1;32(1):13-23.

- Footnote 4

-

Didenko E, Pankratz N. Substance use: Pathways to homelessness? Or a way of adapting to street life. Visions: BC’s Mental Health and Addictions Journal. 2007;4(1):9-10.

- Footnote 5

-

Strehlau V, Torchalla I, Kathy L, Schuetz C, Krausz M. Mental health, concurrent disorders, and health care utilization in homeless women. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2012 Sep 1;18(5):349-60.

- Footnote 6

-

North CS, Eyrich-Garg KM, Pollio DE, Thirthalli J. A prospective study of substance use and housing stability in a homeless population. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2010 Nov 1;45(11):1055-62.

- Footnote 7

-

Hwang SW. Homelessness and health. Cmaj. 2001 Jan 23;164(2):229-33.

- Footnote 8

-

Linden IA, Werker GR, Schutz CG, Mar MY, Krausz M. Regional patterns of substance use in the homeless in British Columbia. BC Studies: The British Columbian Quarterly. 2014 Aug 13(184):103-14.

- Footnote 9

-

Carter J, Zevin B, Lum PJ. Low barrier buprenorphine treatment for persons experiencing homelessness and injecting heroin in San Francisco. Addiction science & clinical practice. 2019 Dec 1;14(1):20.

- Footnote 10

-

Russolillo A, Moniruzzaman A, Parpouchi M, Currie LB, Somers JM. A 10-year retrospective analysis of hospital admissions and length of stay among a cohort of homeless adults in Vancouver, Canada. BMC health services research. 2016 Dec;16(1):1-0.

- Footnote 11

-

Chang DC, Rieb L, Nosova E, Liu Y, Kerr T, DeBeck K. Hospitalization among street-involved youth who use illicit drugs in Vancouver, Canada: a longitudinal analysis. Harm reduction journal. 2018 Dec;15(1):1-6.

- Footnote 12

-

Benfer EA, Vlahov D, Long MY, Walker-Wells E, Pottenger JL, Gonsalves G, Keene DE. Eviction, health inequity, and the spread of covid-19: housing policy as a primary pandemic mitigation strategy. Journal of Urban Health. 2021 Feb;98(1):1-2.

- Footnote 13

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Joint statement from The co-chairs of the special Advisory Committee on the epidemic of opioid Overdoses – ... [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021Apr22]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/news/2021/03/joint-statement-from-the-co-chairs-of-the-special-advisory-committee-on-the-epidemic-of-opioid-overdoses--latest-national-data-on-the-overdose-crisis.html

- Footnote 14

-

Canadian Coding Standards for Version 2018 ICD-10-CA and CCI [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2018 [cited 2021Apr21]. Available from: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/CodingStandards_v2018_EN.pdf

- Footnote 15

-

Gaetz S, Barr C, Friesen A, Harris B, Pauly B, Pearce B. Canadian definition of homelessness. Toronto, ON: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press; 2012.

- Footnote 16

-

Merikangas KR, McClair VL. Epidemiology of substance use disorders. Human genetics. 2012 Jun 1;131(6):779-89.

- Footnote 17

-

Andermann A, Mott S, Mathew CM, Kendall C, Mendonca O, Harriott D, McLellan A, Riddle A, Saad A, Iqbal W, Magwood O, Pottie K. Evidence-informed interventions and best practices for supporting women experiencing or at risk of homelessness: a scoping review with gender and equity analysis. Health Promotion Chronic Disease Prevention Canada. 2021 Jan;41(1):1-13.

- Footnote 18

-

Gaetz S, Donaldson J, Richter T, Gulliver T. The state of homelessness in Canada 2013. Toronto: Canadian Homelessness Research Network Press; 2013.

- Footnote 19

-

Guidelines to Support ALC Designation [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information [cited 2021Apr22]. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/guidelines-to-support-alc-designation#:~:text=Alternate%20level%20of%20care%20(ALC,patients%20in%20acute%20inpatient%20care

- Footnote 20

-

Acute Care [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information [cited 2021Apr22]. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/acute-care

- Footnote 21

-

Marshall JC, Bosco L, Adhikari NK, Connolly B, Diaz JV, Dorman T, Fowler RA, Meyfroidt G, Nakagawa S, Pelosi P, Vincent JL. What is an intensive care unit? A report of the task force of the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine. Journal of critical care. 2017 Feb 1;37:270-6.

- Footnote 22

-

Belzak L, Halverson J. The opioid crisis in Canada: a national perspective. La crise des opioïdes au Canada: une perspective nationale. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2018;38(6):224-33.

- Footnote 23

-

Rapid review: substance use-related harms and risk factors during periods of disruption. [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2020 [cited 2021May21]. Available from: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/ncov/main/2020/08/substance-use-related-harms-disruption.pdf?la=en

- Footnote 24

-

Updated ICD-10-CA coding direction: Homelessness, and falls from an electric scooter (escooter), mobility scooter, Segway® or hoverboard [Internet]. CIHI. [cited 2021Apr13]. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/bulletin/updated-icd-10-ca-coding-direction-homelessness-and-falls-from-an-electric-scooter