Opioid-related Harms in Canada: Integrating Emergency Medical Service, hospitalization, and death data

The opioid overdose crisis continues to devastate families and communities across Canada. In response, local governments, provinces, and territories have implemented a variety of interventions. At the national level, the Government of Canada has committed to a targeted public health response supported by a strong evidence base informed by surveillance and research activities. This report demonstrates how data on Emergency Medical Service (paramedic) responses for suspected opioid-related overdoses, hospitalizations for opioid-related poisonings and apparent opioid-related deaths can be interpreted together to better understand the public health impact and pathways of the crisis.

What information does this report add?

A number of data sources for opioid-related harms provide specific pieces of the puzzle that help us to understand a more complete picture of the opioid overdose crisis in Canada. While significant gaps still exist, this report presents national data on the following opioid-related harms:

- Emergency Medical Service (paramedic) responses for suspected opioid-related overdoses;

- Hospitalizations for opioid-related poisonings; and

- Apparent opioid-related deaths.

For the first time at a national level, this report demonstrates how these data sources can be interpreted together to provide additional insight into the opioid overdose crisis. Specifically, this integrated analysis provides new information on the pathways from opioid overdose to contact with the health care system, and in some cases, apparent opioid-related death.

For example, if someone experiences an opioid-related overdose in the community, 911 may be called so Emergency Medical Service (paramedic) staff can arrive to the person's location as a first response for treatment. Emergency Medical Service (paramedic) staff may administer Naloxone, a drug which can be used to temporarily reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, and transport the person to receive further medical care at the emergency department and/or hospital. Often, people can be treated as an outpatient in the emergency department for their opioid overdose, however sometimes their condition may also require treatment as an inpatient in hospital. Depending on the severity of the overdose and timeliness of treatment, a person may die at any step through these pathways as a result of their condition. This brief report highlights available data for each of these pathways.

Emergency Medical Service responses for suspected opioid-related overdoses (EMS)

How many Emergency Medical Service responses are there for suspected opioid-related overdoses in Canada?

Emergency Medical (paramedic) Services are often the first point of medical intervention for someone who experiences a suspected opioid overdose. First responders, such as paramedics and ambulance crews, respond to 911 calls for suspected opioid-related overdoses and can administer Naloxone which can save a person's life. Between January and September 2019, there were more than 17,000 Emergency Medical Service responses to suspected opioid-related overdoses, based on available data from 9 provinces and territories in Canada.

Who is affected?

People from all sociodemographic groups are affected by the opioid crisis. However, some populations experience a greater burden of opioid-related harm. The majority of Emergency Medical Service responses to suspected opioid-related overdoses were for males (72%) and more than three-quarters (76%) were among young and middle aged adults aged 20-49 years old.

What happened after the Emergency Medical Service response?

Emergency medical (paramedic) service staff transport people to emergency departments and hospitals by ambulance to receive further treatment as required. Currently, national data are not available to indicate how many people may have refused transportation and additional medical care. However, available data shows that most (82%) hospitalizations for opioid-related poisonings in Canada are admitted by ambulance (source: the Discharge Abstract Database, 2018/19).

Emergency department visits for opioid-related overdoses

In some instances, people may receive treatment for opioid overdoses in the emergency department, defined as immediate medical care without an appointment delivered on an outpatient basis, and not become hospitalized as an inpatient. Emergency departments receive patients from Emergency Medical Services as well as from self-referral (that is, patients who come on their own accord or are brought in by lay people such as family or friends), and are usually located in hospitals operating 24 hours a day. However, complete emergency department data were available only for three provinces (Ontario, Alberta and Yukon) at the time this report was released. Data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) shows that, where complete emergency department data is available, for every one hospitalization for an opioid poisoning in 2017, there were roughly four emergency department visits for opioid poisonings Footnote 1. As most opioid poisonings appear to be treated in the emergency department and not as inpatients in hospital, the lack of available national emergency department data creates a large gap in our understanding of opioid-related harms in Canada. The Government of Canada continues to explore opportunities to improve the quality and coverage of these data in the future.

Detailed trends of emergency department visits for opioid-related poisonings in Alberta, Ontario and Yukon, between 2013 and 2017, are available in CIHI's last Opioid-related Harms in Canada release.

Hospitalizations for opioid-related poisonings

How many hospitalizations for opioid-related poisonings are there in Canada?

Someone who experiences an opioid overdose, referred to in the hospital data as an opioid-related poisoning, may need to be hospitalized as an inpatient. Between January 2016 and September 2019, there were 19,490 hospitalizations for opioid-related poisonings in Canada Footnote a. Of note, hospitalization counts for opioid-related poisonings between April to September 2019 are preliminary and expected to change as provinces and territories continue to submit data. Length-of-stay in hospital can be used as an indicator of use of health care resources and severity of harm. This analysis found that the average total length-of-stay in hospital for an opioid-related poisoning was 7.8 days (source: CIHI Discharge Abstract Database, 2018/19). It is important to note that these data represent the number of hospitalizations for opioid-related poisonings, not the number of people who were hospitalized; it is possible the same person may have been hospitalized for an opioid-related poisoning more than once within the study time frame. Future analyses will explore patients that have been hospitalized more than once.

Who is affected?

Among accidental opioid-related poisoning hospitalizations that occurred in 2019 between January and September, the majority (59%) were among males, compared to females (41%). A similar proportion of accidental opioid-related poisoning hospitalizations occurred among young and middle-aged adults, 20 to 49 years old, and older adults aged 50 years and older, at 49% and 46% respectively.

What happened after the hospitalization?

A person can take many pathways after being hospitalized for an opioid-related poisoning, such as a transfer to another facility or in some cases even death, however most people who are hospitalized for opioid-related poisonings are discharged from the hospital to their home.

- Sixty-three percent (63%) of hospitalization records for opioid-related poisonings indicate the patient was discharged home. The majority (53%) were discharged to a private home without supports from the community at home or referral to services, while 10% are discharged to a private home with supports services/referrals. These may include supports from community mental health services, home care, or community based clinics. Patients who are referred after discharge from hospital to their family physician for routine follow up, or referred to a specialist, are considered to be routine discharge orders and are not included in the proportion discharged home with support services or referrals. Of note, this analysis did not examine who needed to be discharged home with supports based on the outcome of their condition; future work is needed to better interpret this finding.

- Nineteen percent (19%) of hospitalization records for opioid-related poisonings indicate the patient was transferred to another facility, for example to another inpatient, ambulatory, or residential care facility.

- More than 1 out of 10 (or 11%) hospitalization records for opioid-related poisonings indicate the patient left against medical advice. This means the patient may not have received all of the medical care or supports available. By comparison, a past study by the Canadian Institute for Health Information found that 1.3% of all acute inpatient hospital admissions ended with patients leaving against medical advice. This study found that patients who left against medical advice were more likely to: be younger males; leave hospital between evening and early morning hours (7 p.m. to 7 a.m.); and be treated for mental health or substance use disorders. Patients who left against medical advice were more than twice as likely to be readmitted within a month and more than three times as likely to visit the emergency department within a week, compared to patients with routine discharges Footnote 2.

- Depending on the severity of the opioid-related poisoning, some people who are hospitalized may die. Between April 2018 and March 2019, 7% of hospitalization records for opioid-related poisonings indicated that the patient died (source: CIHI Discharge Abstract Database, 2018/19).

Apparent opioid-related deaths

How many people die from opioids in Canada?

Between January 2016 and September 2019, more than 14,700 Canadians have lost their lives due to apparent opioid-related deaths. In 2019, between January and September, 94% of apparent opioid-related deaths were deemed to be accidental in nature, meaning the person did not intend to harm themselves.

Who is affected?

Among those who died from accidental apparent opioid-related overdoses in 2019 between January and September, the majority of people were male (75%) compared to female (25%). Most (65%) of people who died accidentally from apparent opioid-related deaths were young and middle aged adults (20-49 years). Fentanyl and fentanyl analogues, which are very toxic synthetic opioids Footnote 3 , were found to be involved in 78% of accidental apparent opioid-related deaths, 72% of these deaths involved one or more non-opioid substance, such as alcohol, methamphetamine or sedatives.

What characteristics are more frequent among people who died?

A study that asked coroners, medical examiners, and toxicologists in Canada to reflect upon opioid- and other drug-related overdose deaths they had investigated between 2016 and 2017 Footnote 4, found that characteristics more frequently observed among those who died included:

- lack of social support;

- lower drug tolerance (tolerance refers to when a person needs to use a higher amount of a substance over time to obtain the same effect. People who are new to using a substance, or have stopped using a substance for a period of time, may have lower drug tolerance which can put them at a greater risk of harm as they may use more of a substance than their body can handle)Footnote 5 ;

- polysubstance use (using more than one type of substance together);

- being alone at the time of overdose;

- history of mental health concerns, substance user disorder, trauma, and/or experiences of stigma; and

- a lack of comprehensive and coordinated healthcare and social service follow up

Future directions

This report presents part of the public health impact of opioid-related harms in Canada. The Government of Canada will continue to work collaboratively to collect and report national data, surveillance and research to better inform evidence-based public health responses to reduce opioid-related harms. As surveillance systems evolve, future work that can further inform prevention and intervention strategies may include identifying other types of opioid-related harms (beyond poisonings and deaths) in addition to exploring factors that put people at greater risk of harm.

In summary

Canada is currently experiencing an opioid overdose crisis. The pathways of harm presented in this report provide an analysis of how Emergency Medical Service responses for suspected opioid-related overdoses, opioid-related poisoning hospitalizations, and apparent opioid-related death data inform a more complete picture of opioid-related harms in Canada.

This report found that most people who are hospitalized for opioid-related poisonings are admitted by ambulance and discharged to their home after their hospitalization. Of note, the majority (53%) of opioid-related poisoning hospitalizations indicate the patient was discharged home without supports from the community at home or referred to services, while 10% are discharged home with supports services which may include supports from community mental health services, home care, or community based clinics. It's important to note that this analysis did not examine who needed to be discharged home with supports based on the outcome of their condition; therefore more work is needed to interpret this finding. In addition, in more than 1 out of 10 cases, people who were hospitalized for opioid-related poisonings left the hospital against medical advice, which means they may not have received all of the medical care or supports available. Another key finding of this report is the mortality proportion for opioid-related poisonings in hospital: it was found that in 7% of hospitalizations for opioid-related poisonings, the person died in the hospital.

People from all walks of life are affected by the opioid crisis, however this report found that the majority of Emergency Medical Service responses to suspected opioid-related overdoses, hospitalizations for accidental opioid-related poisonings and accidental apparent opioid-related deaths were among males (ranging from 59%-75%). Most Emergency Medical Service responses for suspected opioid-related overdoses and accidental apparent opioid-related deaths were among young and middle aged adults (20-49 years). In comparison, older adults, aged 50 years or older, and young and middle aged adults (20-49 years) accounted for a similar proportion of hospitalizations for accidental opioid-related poisonings. Reasons for the differences in the profile of these groups should be explored in future research, to better target prevention and treatment interventions.

It is important to note that the analysis in this report presents only part of the public health impact of the opioid crisis in Canada. The Government of Canada will continue to work to improve data and analysis to inform strategies and interventions to reduce opioid-related harms across the country. More detailed information on opioid-related harms in Canada and technical notes can be found at: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids.

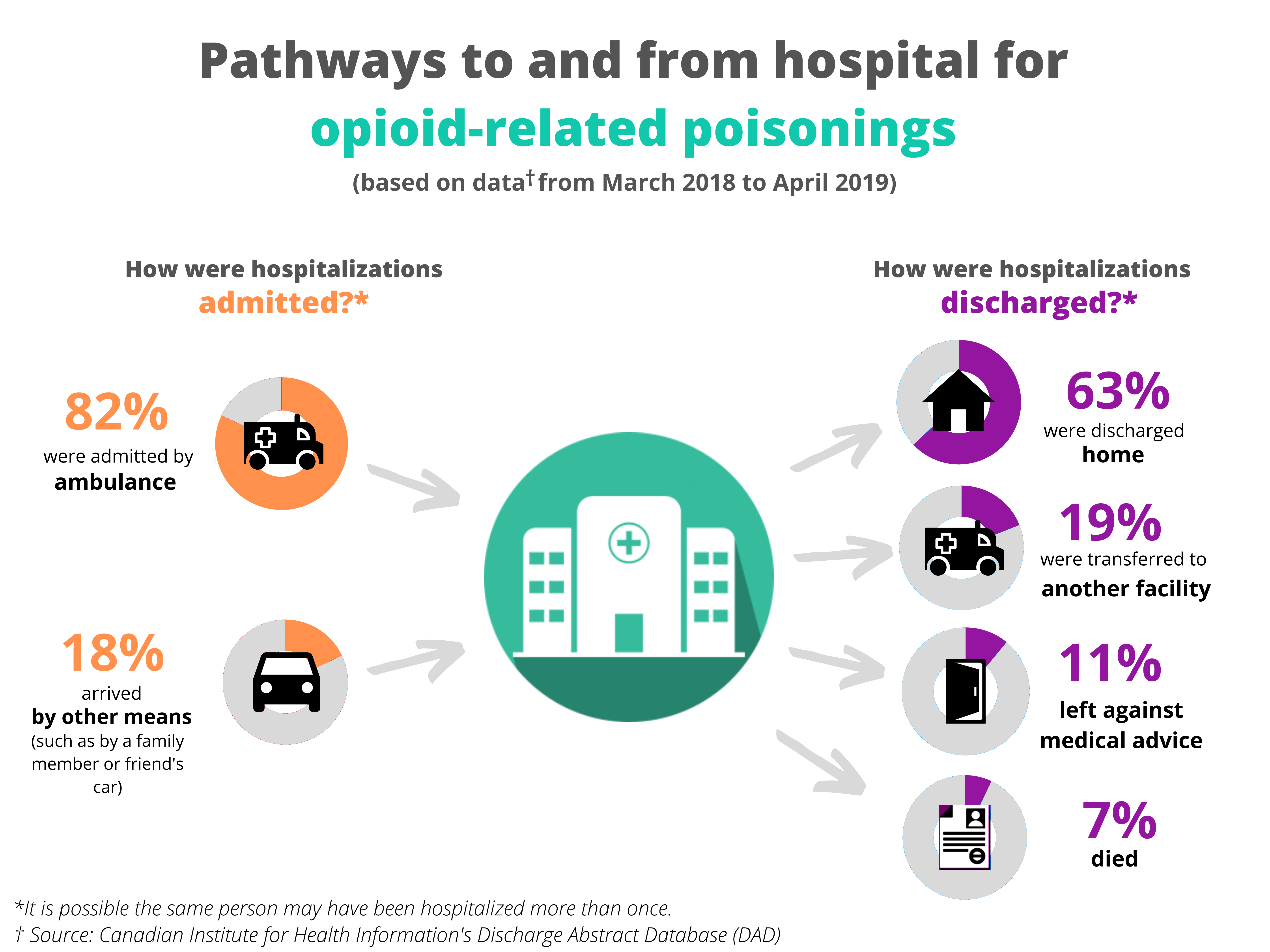

A summary of this report's key findings are highlighted in the infographic below (Figure 1).

Text description for infographic (Figure 1)

Figure 1 depicts an infographic of pathways to and from hospital for opioid-related poisonings, based on available data from April 2018 to March 2019, from the Canadian Institute for Health Information's Discharge Abstract Database.

How were hospitalizations admitted?

- 82% were admitted by ambulance

- 18% arrived by other means, such as by a family member or friend's car

How were hospitalizations discharged?

- 63% were discharged home

- 19% were transferred to another facility

- 11% left against medical advice

- 7% died

It is possible the same person may have been hospitalized more than once between April 2018 to March 2019.

Acknowledgements

This brief report would not be possible without the collaboration and dedication of provincial and territorial (PT) offices of Chief Coroners and Medical Examiners as well as PT public health and health partners and Emergency Medical Services data providers. We would also like to acknowledge the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) for collecting and providing the data used for reporting opioid-related poisoning hospitalizations.

Disclaimer

Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by CIHI. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of CIHI.

Methodology

To analyze pathways to and from hospital for opioid-related poisonings, data was analyzed from the Canadian Institute for Health Information's (CIHI) Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) for fiscal year 2018/2019. The fiscal year begins April 1, 2018 and ends March 31, 2019. The approach for identifying opioid-related poisoning hospitalizations aligned with CIHI's methodology in their reporting of opioid-related harms, except this analysis excluded Quebec data which was included in CIHI's reporting Footnote 6. The DAD contains demographic, administrative and clinical data on all separations from acute inpatient facilities in all provinces and territories except Quebec. Detailed information about the DAD can be found on CIHI's website: https://www.cihi.ca/en/discharge-abstract-database-metadata

Opioid-related poisoning hospitalizations were identified using the ICD-10-CA T40- codes listed in Appendix A. Only opioid poisoning diagnoses that were considered influential to the time spent and/or treatment received while in hospital, as defined by diagnosis types "M" (most responsible diagnosis (MRD)), "1" (pre-admission comorbidity), "2" (post-admission comorbidity), "W", "X", "Y" (service transfer diagnosis), and "6" (proxy MRD) were included. Opioid poisoning codes with a prefix of Q, indicating a suspected diagnosis, were excluded from this analysis, as were cadavers and still births records. The following mandatory fields were used to examine routes by which people were admitted and discharged from hospital:

| Field | Description/Values |

|---|---|

Admit via Ambulance |

Identifies whether a patient arrives at the reporting facility via ambulance and the type of ambulance that was used.

|

Discharge Disposition |

The location where the patient was discharged to or the status of the patient on discharge.

|

The values for Admit via Ambulance were recoded into a dichotomous variable (1 = Admitted by ambulance (A, G, C), 2 = Arrived by other means (N)). To determine which individuals died, Discharge Disposition was recoded as 1 = Died (66, 67, 72, 73, 74) and 2 = Not known to have died (04, 05, 10, 20, 30, 40, 61, 62, 65, 90).

For the detailed methodology regarding how apparent opioid-related deaths and Emergency Medical Service responses for suspected opioid overdoses were counted, please refer to the technical notes at: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids

For this study, linkage of data sources was not conducted; analysis was independent for each data source.

Appendix A: ICD-10-CA codes used to identify opioid-related poisoning hospitalizations

| ICD-10-CA Code | ICD-10-CA Description |

|---|---|

T40.0 |

Poisoning by opium |

T40.1 |

Poisoning by heroin |

T40.2 |

Poisoning by other opioids (e.g., codeine, hydromorphone, morphine, oxycodone) |

T40.20Footnote * |

Poisoning by codeine and derivatives |

T40.21Footnote * |

Poisoning by morphine |

T40.22Footnote * |

Poisoning by hydromorphone |

T40.23Footnote * |

Poisoning by oxycodone |

T40.28Footnote * |

Poisoning by other opioids not elsewhere classified |

T40.3 |

Poisoning by methadone |

T40.4 |

Poisoning by synthetic narcotics (e.g., fentanyl, tramadol) |

T40.40Footnote * |

Poisoning by fentanyl and derivatives |

T40.41Footnote * |

Poisoning by tramadol |

T40.48Footnote * |

Poisoning by other synthetic narcotics not elsewhere classified |

T40.6 |

Poisoning by unspecified/other narcotics (e.g., analgesic - not elsewhere classified, narcotic - not elsewhere classified) |

Footnote

- Footnote a

-

Excludes data from Quebec

References

- Footnote 1

-

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Opioid-Related Harms in Canada - data tables. December 2018.

- Footnote 2

-

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Leaving Against Medical Advice: Characteristics Associated With Self-Discharge. October 1, 2013:1-20.

- Footnote 3

-

Government of Canada. Fentanyl: Learn about fentanyl, why it can be dangerous, and what to do in the case of an overdose. 2019; Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/controlled-illegal-drugs/fentanyl.html. Accessed February/20, 2020.

- Footnote 4

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. Highlights from phase one of the national study on opioid and other drug-related overdose deaths: insights from coroners and medical examiners. 2019. Updated October 2019; Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/highlights-phase-one-national-study-opioid-illegal-substance-related-overdose-deaths.html. Accessed February/20, 2020.

- Footnote 5

-

Government of Canada. About problematic substance use. 2019; Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/about-problematic-substance-use.html. Accessed February/20, 2020.

- Footnote 6

-

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Opioid-Related Harms in Canada. December 2018:1-79.