ARCHIVED – 2017 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration

Table of Contents

- Message from the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship

- Introduction

- Section 1: Managing Permanent Immigration

- Section 2: Managing Temporary Migration

- Section 3: Federal-Provincial/Territorial Partnerships

- Section 4: Gender-based Analysis Plus of the Impact of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

- Additional Information

- Annex: Section 94 and Section 22.1 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

Message from the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship

As Canada marked its 150th anniversary of Confederation this year, Canadians across the country celebrated the diversity that makes us strong. Throughout our history, Canada has proudly welcomed immigrants and refugees from around the world. Indeed, our country was built by the many significant cultural and economic contributions of immigrants and our Indigenous peoples.

Immigration is not only an important part of our country’s history. It will also be integral to our country’s future, helping to spur economic growth, job creation and our prosperity. As Canada’s Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship, I’m honoured to carry forward our country’s welcoming tradition, while we shape our country’s future.

In 2016, Canada welcomed more than 296,000 permanent residents, which is close to our new, ongoing target of 300,000 that we aim to achieve in 2017. In order to meet the growing needs of our economy and expanding labour market, the highest category of admissions in 2016 continued to be the Economic Class, which included approximately 156,000 permanent residents.

The high level of permanent resident admissions in 2016 also featured an extraordinary commitment to resettle Syrian refugees and a renewed focus on reuniting families. More than 62,000 people were admitted to Canada as resettled refugees, as people who were granted protected persons status in Canada through the asylum system, and people admitted for humanitarian and compassionate considerations under public policies. Canada also welcomed approximately 78,000 permanent residents in the Family Class, which is 19 percent higher than admissions in 2015 and reflects a Government of Canada commitment to reuniting more families faster.

Temporary immigration also continues to serve an important role in meeting our labour market needs and represents a significant contribution to our economy in general. Canada is becoming an increasingly popular destination for international students and tourism, and those who came to Canada temporarily in 2016 accounted for $32.2 billion in our economy.

This past year, Canada issued over 286,000 work permits to temporary workers. To help attract and retain global talent, the Government also launched the Global Skills Strategy in 2016. A key aspect of this effort will get highly-skilled temporary workers here faster, helping businesses to attract the talent they need to succeed in an increasingly competitive global market.

To better meet regional economic needs through immigration, this past year Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada launched the employer-focused Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program. As well, to enhance our country’s competitiveness globally, the Start-up Visa Program is now a permanent feature of our economic immigration program.

While Canada will continue to be a welcoming country that embraces our diversity, the Government is also aware of the ongoing need to balance our openness with the security and safety of Canadians. This balance is critical to the future success of our immigration program, to ensure it continues to bring economic and social benefits to Canada. We remain committed to reuniting more families faster and to upholding our humanitarian obligations, while we strive to make our immigration system more efficient and responsive to our economic needs.

As we continue to work towards achieving these goals at Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship, is with great pride that I present the Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration 2017, including the levels plan for 2018 to 2020.

____________________________________

The Honourable Ahmed D. Hussen, PC., M.P.

Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship

Introduction

About Immigration to Canada

Immigration to Canada can be either on a permanent basis or temporary in nature, such as to visit, study or work. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) is responsible for overall management of Canada’s immigration system and handles large volumes of permanent and temporary resident applications across its extensive global processing network. With both temporary and permanent immigration, applicants are screened to protect the health, safety and security of Canadians.

Through temporary and permanent resident immigration streams, Canada selects foreign nationals whose skills contribute to Canadian prosperity, as well as family members. Canada’s humanitarian tradition and international obligations are also upheld by welcoming refugees, and other people in need of protection, to the country.

When foreign nationals are selected to immigrate to Canada as permanent residents, IRCC works with provincial and territorial partners, as well as service provider organizations, to help them settle into Canadian society and the economy through a number of different settlement services.

About This Report

Every year the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship tables this Annual Report in Parliament on Canada’s immigration system. The report provides the Minister with an opportunity to consistently report on key details for permanent resident admissions, temporary resident volumes, aspects of inadmissibility as well as gender-based analysis. It also serves as an important contextual backdrop for the projection of permanent resident admissions for the subsequent calendar year, which is essential for planning purposes for IRCC and its partners inside and outside government.

The Annual Report adheres to the requirements of section 94 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA, see Annex). As in past years, the report focuses on permanent resident admissions from the previous year and the plan for admissions in the coming year, temporary resident volumes and admissibility from the previous year, provincial and territorial partnerships and bilateral agreements, as well as Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+). As indicated in last year’s report, the gender-based analysis component of this year’s report has been enhanced and now incorporates sex-disaggregated data throughout.Footnote 1 Also, the section normally devoted to gender-based analysis now focuses on more enhanced gender and other intersectional identity considerations (GBA+) in immigrant outcomes, economic immigration, family reunification, resettlement and settlement.

SECTION 1 provides key statistics relating to permanent residents admitted in 2016, and highlights immigration levels for 2018 to 2020.

SECTION 2 provides key statistics relating to temporary residents admitted in 2016.

SECTION 3 focuses on IRCC’s partnerships with the provinces and territories. It outlines the bilateral agreements currently in force between the federal government and provincial and territorial governments and describes major joint initiatives.

SECTION 4 provides Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+) highlights of IRCC’s work in 2016.

Section 1: Managing Permanent Immigration

2016 Permanent Resident Admissions

The Government of Canada, in consultation with the provinces and territories and with input from stakeholders, plans admissions of permanent residents each year in order to meet government goals for immigration, uphold the objectives for immigration as set out in the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) and achieve its priorities in a way that balances the benefits of immigration with its costs. Permanent residents are persons who have been admitted to live in Canada on a permanent basis and who have the right to work and study in Canada, but have not become Canadian citizens. To maintain this status and not become inadmissible, they must continue to meet residency requirements and not violate the conditions of their status by reason of serious criminality, security, human or international rights violations, organized crime or misrepresentation. As defined in IRPA, there are three basic classes of permanent residents: economic, family and refugees. The following is an overview of permanent resident admissions in 2016.

Admissions of Permanent Residents in 2016

Canada admitted 296,346 permanent residents in 2016, an increase over 2015 (271,845), and the highest admissions levels since 2010, when Canada welcomed 280,688 permanent residents. This level of admissions, which featured an extraordinary commitment to resettle Syrian refugees as well as a renewed focus on reuniting families, was within the planned levels range of 280,000 to 305,000.

Of those admitted, 53% were economic immigrants (along with their spouse/partner and dependants), 26% were sponsored family members, 20% were either resettled refugees or protected persons, and 1% were in the humanitarian and other category. Table 1 provides a detailed breakdown of the 2016 admissions by immigration category and by sex (male and femaleFootnote 2) in each category. More statistical information on admissions can be found in the Government of Canada’s Open Data website and in the Facts and Figures published by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC).

Throughout the Annual Report, highlights of sex-disaggregated data is provided. Sex-disaggregation of total admissions (principal applicant and their immediate family unit) within each economic immigration program often show near parity between females and males. However, the female/male breakdown of principal applicants can reveal gendered differences. Immigration program selection criteria is applied only to principal applicants—in economic programs, this would be human capital criteria of education or language skills, job offer or provincial/territorial nomination.

| Immigrant Category | 2016 Plan Admission Ranges - Low | 2016 Plan Admission Ranges - High | Number Admitted in 2016 | Females Admitted in 2016 | Males Admitted in 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal Economic – SkilledFootnote 3 | 54,000 | 59,000 | 59,999 | 28,340 | 31,657 |

| Federal Economic – CaregiversFootnote 4 | 20,000 | 22,000 | 18,467 | 10,525 | 7,941 |

| Federal Economic – BusinessFootnote 5 | 500 | 900 | 867 | 402 | 465 |

| Provincial Nominee | 46,000 | 48,000 | 46,170 | 22,139 | 24,031 |

| Quebec Skilled Workers | 25,500 | 27,000 | 25,857 | 12,476 | 13,381 |

| Quebec Business Immigrants | 5,200 | 5,500 | 4,634 | 2,274 | 2,360 |

| Total Economic | 151,200 | 162,400 | 155,994 | 76,156 | 79,835 |

| Spouses, Partners and Children | 57,000 | 62,000 | 60,588 | 35,314 | 25,271 |

| Parents and Grandparents | 18,000 | 20,000 | 17,041 | 9,832 | 7,203 |

| Family – OtherFootnote 6 | - | - | 375 | 211 | 164 |

| Total Family | 75,000 | 82,000 | 78,004 | 45,357 | 32,638 |

| Protected Persons in Canada and Dependants Abroad | 10,000 | 11,000 | 12,116 | 6,026 | 6,089 |

| Government-Assisted Refugees | 24,000 | 25,000 | 23,523 | 11,535 | 11,988 |

| Blended Visa Office-Referred Refugees | 2,000 | 3,000 | 4,434 | 2,168 | 2,266 |

| Privately Sponsored Refugees | 15,000 | 18,000 | 18,362 | 8,734 | 9,628 |

| Total Protected Persons and Refugees | 51,000 | 57,000 | 58,435 | 28,463 | 29,971 |

| Humanitarian and OtherFootnote 7 | 2,800 | 3,600 | 3,913 | 2,055 | 1,858 |

| Total Humanitarian | 2,800 | 3,600 | 3,913 | 2,055 | 1,858 |

| Total | 280,000 | 305,000 | 296,346 | 152,031 | 144,302 |

Source: IRCC, Permanent Resident Data as of May 2017. Additional IRCC data are also available through the Quarterly Administrative Data Release. Any numbers in this report that were derived from IRCC data sources may differ from those reported in earlier publications; these differences reflect typical adjustments to IRCC’s administrative data files over time. As the data in this report are taken from a single point in time, it is expected that they will change over time as additional information becomes available.

Sex-disaggregated data: Totals of sex-disaggregated data may not add up to the totals for “Number Admitted in 2016” due to instances where gender was not stated.

Highlights of Economic Class Admissions in 2016

Rooted in the objectives outlined in IRPA, economic class immigration focuses on the selection and processing of immigrants to build a skilled work force, address immediate and longer-term labour market needs, and support national and regional labour force growth. The Economic Class includes federal economic programs, Quebec-selected skilled workers, federal and Quebec-selected business immigrants, provincial and territorial nominees, and caregivers. It also includes spouses, partners and dependants who accompany the principal applicants in any of these economic categories.

In 2016, Canada admitted 155,994 permanent residents in Economic Class programs, of which 69,709 were principal applicants and 86,285 were immediate family members. This represented an 8% decrease in economic admissions from 2015, which was necessary in order to fulfil the Government’s commitments to refugee resettlement and family reunification. However, the number of economic admissions was within the planned admissions range of 151,200 to 162,400 and was in line with the average number of Economic Class admissions of the previous five years (160,000).

For all Economic Class admissions, 49% were females and 51% were males. Among principal applicants only (69,709), 42% of principal applicants were female while 58% were male. In 2016, the gender gap between female and male principal applicants was 16 percentage points, which is narrower than in the early 2010s (the gap was around 20%) and late 2000s (the gap was around 30%).

Skilled Workers

In 2016, a total of 59,999 permanent residents were admitted (28,082 principal applicants and 31,917 immediate family members) to Canada through the Federal Economic - skilled category, which exceeded the planning range of 54,000 to 59,000. Within this category, 47% of those admitted were female and 53% were male. Among principal applicants only, 35% were female and 65% were male.

Three key programs facilitate the admission of skilled workers to Canada: the Federal Skilled Worker (FSW) Program selects immigrants with skills in managerial, professional or high-skilled occupations on the basis of their ability to become economically established in Canada; the Federal Skilled Trades (FST) Program facilitates the entry of skilled tradespersons, emphasizing practical training and work experience; and the Canadian Experience Class (CEC) Program enables certain skilled temporary foreign workers—including many who were international student graduates with at least one year of full-time work experience after graduation—to stay in Canada permanently.

In 2016, there were 39,749 people admitted (17,435 principal applicants and 22,314 immediate family members) under the FSW Program; 2,428 (921 principal applicants and 1,507 immediate family members) under the FST Program; and 17,822 (9,726 principal applicants and 8,096 immediate family members) under the CEC Program.

In 2016, of principal applicants in the FSW Program, 35% were female and 65% were male. In the FST Program, 5% of principal applicants were female and 95% were male, reflecting the historically gendered nature of this industry sector which has been predominately male. Under the CEC Program, 36% of principal applicants were female and 64% were male.

The vast majority of admissions from these three federal programs, and a portion of the Provincial Nominee Program (PN), are sourced from the Express Entry pool of candidates. While there remains a small inventory of pre-Express Entry applications, by the end of 2016, about 95% of the inventory for the pre-Express Entry federal programs had been processed to completion. To ensure a more fair and responsive immigration system that addresses emerging needs and long-term economic growth for Canada, some improvements were made to Express Entry on November 19, 2016, including a reduction in job offer points, changes to job offer requirements, points for students who studied in Canada, and more time to complete an application for permanent residence. In 2016, a total of 33,410 Economic Class admissions were sourced from Express Entry, representing 21% of all economic admissions. More details can be found in the Express Entry Year-End Report 2016.

Of all the Federal Economic - Highly Skilled admissions, 25,590 were through Express Entry (11,471 principal applicants and 14,119 immediate family members), an increase from the previous year’s total of 9,301.

The remaining 2016 admissions in the Federal Economic - Highly Skilled category (34,409) were from applications that were submitted to the Department for processing prior to the launch of Express Entry in 2015. At the end of 2016, about 95% of the inventory for the pre-Express Entry federal programs had been processed to completion.

Caregivers

The Federal Economic - Caregivers category includes three pathways to permanent residence: the Caring for Children Program, the Caring for People with High Medical Needs Program, and the legacy Live-in Caregiver Program, which remains open for select applicants who were grandfathered before IRCC ended the program in November 2014. In 2016, IRCC admitted 18,467 caregivers as permanent residents (6,835 principal applicants and 11,632 immediate family members), which is slightly below the planned admission range of 20,000 to 22,000. As in previous years, in 2016 the majority (94%) of principal applicant admissions under the Caregivers category were female, compared to 6% who were male, which reflects the historically gendered nature of this industry sector.

Businesses

A total of 867 admissions (323 principal applicants and 544 immediate family members) in 2016 were processed through Federal Economic - Business Immigration programs, which include immigrant investors, entrepreneurs, self-employed persons, and participants in the Start-up Visa Program. Following the backlog termination measures enacted through the 2014 Budget Implementation Act, a portion of admissions (1.8%) in 2016 continue to represent remaining legacy cases in the investor and entrepreneur programs. The majority of admissions in 2016 were self-employed persons, representing 609 principal applicants and their accompanying spouses and dependants. As has been the case in previous years, the majority of all admissions involved male principal applicants. In 2016, females accounted for 30% of applicants while males accounted for 70%, reflecting the historically gendered nature of business immigrants.

Provincial Nominees

The PN Program provides provinces and territories with a mechanism to respond to their particular economic needs by allowing them to nominate individuals who will meet specific local labour market demands, and to spread the benefits of immigration across Canada by promoting immigration to areas that are not traditional immigration destinations. The number of PN admissions in 2016 was 46,170 (20,486 principal applicants and 25,684 immediate family members), which was within the planning range of 46,000 to 48,000. In 2016, females represented 35% of PN principal applicant admissions while males represented 65%.

Of the total admissions (principal applicants and immediate family members) under the PN Program, 7,818 were through Express Entry, a significant increase from 498 in 2015. The substantial increase in Express Entry admissions reflects higher take-up among participating provinces and territories, many of which have implemented or adapted PN streams to leverage the Express Entry system.

Highlights of Family Reunification Admissions in 2016

Canadian citizens and permanent residents may sponsor spouses or partners, dependent children, parents, grandparents and other close relatives to become permanent residents as Family Class immigrants. In 2016, Canada welcomed 78,004 permanent residents in the Family Class, which was within the planned admission range of 75,000 to 82,000. This total is 19% higher than 2015 and reflects a Government of Canada commitment to reunite more families faster. In addition, processing times have improved. For example, as of December 2016, processing times for all family class applications was 26 months, compared to 34 months at the end of December 2015. In the last three years (including 2016), total family class admissions were around 58% female and 42% male, which is reflective of historic trends.

As part of the Government of Canada’s efforts to deliver faster processing and shorter wait times for spousal reunification, in 2016 the Government increased the number of planned admissions in the Spouses, Partners and Children category by 25%, to 60,000. In 2016, Canada welcomed 60,588 sponsored spouses, partners and children: overall, 58% were female and 42% were male. This was within the planned admission range of 57,000 to 62,000.

On average over the last three years (including 2016), about 50,000 spouses and partners were sponsored each year, with approximately 59% being female and 41% being male. As of December 2016, processing times for all spouses and partners applications was 20 months for in-Canada applications and 15 months for overseas applications; this represents a reduction from December 2015, when processing times were 23 months and 17 months, respectively. Also over the last three years (including 2016), an average of approximately 3,500 children were sponsored each year, with about 48% being female and 52% being male.

In 2016, a total of 17,041 persons were admitted in the Parent and Grandparent category. Of this number, 58% were female and 42% were male, which is generally consistent with the previous two years.

During the same year, the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship doubled the annual cap on the number of sponsorships that would be accepted for processing to 10,000, thereby achieving a priority in his mandate letter. Despite the higher volume of new applications, IRCC continues to make progress on reducing the inventory of sponsored parent and grandparent applications, which has been reduced by 72%, from a total of 125,599 applications (in persons) since the beginning of 2012.Footnote 8

Parents and grandparents of Canadian citizens and permanent residents also have the option of coming to Canada temporarily on a super visa. This allows eligible parents and grandparents to visit Canada for up to two years without the need for status renewal, and to make multiple entries for up to 10 years. In 2016, Canada issued 17,327 super visas: 64% were for females, and 36% were for males.

The family reunification of parents and grandparents to Canadians or permanent resident sponsors may have a gendered dimension. In the 2014 Evaluation of the Family Reunification Program, sponsors were asked how often their sponsored relative helps provide child care to their family. A large majority of respondents to the survey (85%) said their parent or grandparent often or sometimes provided child care, which would provide a significant benefit to these families, particularly in enabling both parents (female/male) to join the workforce. Without this childcare support from a parent or grandparent, the responsibility of childcare often historically rest on the female spouse.

Highlights of Protected Persons, Refugees and Humanitarian Admissions in 2016Footnote 9

IRCC and its partners play a significant role in upholding Canada’s international and humanitarian commitments by offering protection to refugees and persons in need of protection, including in response to significant humanitarian crises. In 2016, a total of 62,348 people were admitted to Canada as permanent residents who had been granted protected persons status in Canada through the asylum system, as resettled refugees, or as people admitted for humanitarian and compassionate considerations and under public policies. This total represents an increase of 73% over 2015 and more than twice the five-year average from 2011–2015. Of the total number of protected persons, refugees and humanitarian admissions in 2016, 49% were female and 51% were male.

In 2016, a total of 46,319 refugees were resettled to Canada, exceeding the high end of the planned admission range of 46,000. This enabled the Department to both fulfil the Government’s commitment to resettle Syrian refugees to Canada in 2016 as well as accommodate refugee resettlement from other parts of the world through existing multi-year refugee resettlement commitments, and the private sponsorship of refugees. Among refugee principal applicant admissions (15,368), 27% were females and 73% were males; however, among refugee spouse and dependant admissions (30,951), 59% were female and 41% were males. Almost half (47%) of all resettled refugees in 2016 were 17 years old or under, of which 48% were female and 52% were male. Refugee resettlement programs include gender, gender identity and expression, and diversity considerations. For example, victims of gender-based violence are considered to be vulnerable persons, and in their assessment of cases, departmental officers consider factors submitted by a refugee regarding gender-related issues, such as sexual orientation or need for protection due to their gender and other identity factors (e.g., belonging to a certain group).

In 2016, the majority of resettled refugees, totalling 27,957, were directly supported by the government in whole or in part: 23,523 resettled as government-assisted refugees (slightly below the planned admissions range of 24,000 to 25,000), and 4,434 resettled as blended visa office-referred refugees, which was well above the planned admissions range of 2,000 to 3,000. Additionally, 18,362 were privately sponsored refugees, which slightly exceeded the planned admissions range of 15,000 to 18,000. Of note, the 2016 planned and actual admissions of privately sponsored refugees represented a significant increase over historical levels. For each of the three refugee streams, the proportion of females and males (principal applicants and their immediate family) has been generally consistent in the last three years (including 2016). For the blended visa office-referred refugees and government-assisted refugees streams, 49% were female and 51% were male; for privately sponsored refugees, an average of 47% were female and 53% were male each year.

In addition to refugee resettlement, 12,116 asylum claimants and their dependants received permanent residency under the Protected Persons in Canada and Dependants Abroad category in 2016. This total exceeded the planned admissions range of 10,000 to 11,000. In 2016, there were 7,498 principal applicant asylum claimants who were granted protected persons status in Canada through the asylum system, of whom 46% were female and 54% were male. Of these, 8% (597 individuals) were 17 years old or under, with near proportional parity between female youth (48%) and male youth (52%). These proportions for youth principal applicants have been consistent in the last three years. More information about Canada’s refugee resettlement programs and in-Canada asylum process can be found on the IRCC website.

IRPA authorizes the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship to consider the circumstances of, and grant permanent resident status to, individuals and their families who would not otherwise qualify under an immigration program. These discretionary provisions for humanitarian and compassionate considerations, or for reasons of public policy, provide the flexibility to approve deserving cases that come forward.

For admissions related to humanitarian and compassionate considerations, for reasons of public policy, and permit holders, a total of 3,913 people were admitted into Canada in 2016, which is above the planned admission range of 2,800 to 3,600.

Admissions of Permanent Residents by Knowledge of Official Language in 2016

As outlined in IRPA, one of the objectives of Canada’s immigration system is to enrich and strengthen the cultural fabric of Canadian society, while respecting its bilingual character. Table 2 shows the knowledge of official languages among permanent residents. Of the permanent residents admitted in 2016, a total of 73% self-identified as having knowledge of English, French or both official languages, which is a decrease of three percentage points compared to 2015.

Among all economic immigrant principal applicants admitted, 96% self-identified as having knowledge of at least one of the official languages in 2016, of which 42% were female and 58% were male. Among female economic immigrant principal applicants, 96% self-identified as having knowledge of at least one of the official languages; among male economic immigrant principal applicants, 97% self-identified as having knowledge of at least one of the official languages.

In 2016, among all sponsored family members (spouses/partners, children, parents and grandparents), 71% of females and 72% of males self-identified as having knowledge of at least one of the official languages. Among all resettled refugees and protected persons in Canada, the proportions were 37% for females and 39% for males.

| Immigration Class | English | French | Both | Neither | Not Stated | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sponsored Family | 49,089 | 6,141 | 662 | 20,347 | 1,765 | 78,004 |

| Female | 28,202 | 3,672 | 375 | 12,139 | 969 | 45,357 |

| Male | 20,885 | 2,469 | 287 | 8,201 | 796 | 32,638 |

| Economic Immigrants—Principal Applicants | 56,698 | 7,838 | 2,714 | 2,324 | 137 | 69,711 |

| Female | 23,616 | 3,199 | 1,227 | 1,083 | 51 | 29,176 |

| Male | 33,081 | 4,639 | 1,487 | 1,241 | 86 | 40,534 |

| Economic Immigrants—Spouses and Dependants | 60,227 | 6,907 | 1,318 | 15,469 | 2,368 | 86,289 |

| Female | 33,326 | 3,897 | 739 | 7,775 | 1,246 | 46,983 |

| Male | 26,899 | 3,010 | 579 | 7,694 | 1,122 | 39,304 |

| Total Economic Immigration | 116,925 | 14,745 | 4,032 | 17,793 | 2,505 | 156,000 |

| Female | 56,942 | 7,096 | 1,966 | 8,858 | 1,297 | 76,159 |

| Male | 59,980 | 7,649 | 2,066 | 8,935 | 1,208 | 79,838 |

| Resettled Refugees and Protected Person in Canada | 19,676 | 2,755 | 228 | 32,997 | 3,256 | 58,912 |

| Female | 9,171 | 1,444 | 112 | 16,357 | 1,605 | 28,689 |

| Male | 10,505 | 1,311 | 116 | 16,640 | 1,650 | 30,222 |

| All Other Immigration | 1,886 | 1,075 | 34 | 111 | 324 | 3,430 |

| Female | 1,045 | 515 | 13 | 78 | 175 | 1,826 |

| Male | 841 | 560 | 21 | 33 | 149 | 1,604 |

| Total | 187,576 | 24,716 | 4,956 | 71,248 | 7,850 | 296,346 |

| Female | 95,360 | 12,727 | 2,466 | 37,432 | 4,046 | 152,031 |

| Male | 92,211 | 11,989 | 2,490 | 33,809 | 3,803 | 144,302 |

Source: IRCC, Permanent Residents Data as of May 2017.

Note: Totals of sex-disaggregated data may not add up to the numbers in each of the categories due to cases where gender was not stated. Data in this table may differ from those found in other tables in this report due to the date these numbers were extracted from IRCC’s data systems.

Admissions of Permanent Residents by Top 10 Source Countries in 2016

Canada’s immigration program is based on non-discriminatory principles, where foreign nationals are assessed without regard to race, nationality, ethnic origin, religion, gender identity or sexual orientation. Canada receives its immigrant population from over 200 countries of origin.

As Table 3 indicates, 63% of new permanent residents admitted in 2016 came from the top 10 source countries, which is an increase of two percentage points compared to 2015. The overall composition of the top 10 countries in 2016 remains similar to 2015. However, due to the Government’s second year of responding to the Syrian refugee crisis, the number of permanent residents with Syrian citizenship climbed even further up the list of top source countries, making it the third largest country of citizenship in 2016.

Of the total number of permanent residents admitted in 2016 from the top 10 countries of citizenship, slightly more men (51%) than women (49%) were admitted in 2016, consistent with previous years. Of the top 10 source countries, a slightly higher proportion of female permanent residents in 2016 came from the Philippines, China and Iran, whereas a slightly higher proportion of male permanent residents came from France, the United Kingdom and Eritrea.

| Rank | Country | Number | Percentage | Females | Males |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Philippines | 41,791 | 14 | 22,631 | 19,158 |

| 2 | India | 39,789 | 13 | 19,511 | 20,276 |

| 3 | Syria | 34,925 | 12 | 17,123 | 17,802 |

| 4 | China, People’s Republic of | 26,852 | 9 | 14,864 | 11,988 |

| 5 | Pakistan | 11,337 | 4 | 5,811 | 5,525 |

| 6 | United States of America | 8,409 | 3 | 4,251 | 4,156 |

| 7 | Iran | 6,483 | 2 | 3,345 | 3,138 |

| 8 | France | 6,348 | 2 | 2,996 | 3,352 |

| 9 | United Kingdom and Colonies | 5,812 | 2 | 2,392 | 3,419 |

| 10 | Eritrea | 4,629 | 2 | 2,009 | 2,620 |

| Total Top 10 | 186,375 | 63 | 94,933 | 91,434 | |

| All Other Source Countries | 109,971 | 37 | 57,098 | 52,868 | |

| Total | 296,346 | 100 | 152,031 | 144,302 | |

Source: IRCC, Permanent Resident Data as of May 2017.

Canada’s Immigration Plan for 2018 to 2020

Starting in 2018, the Government of Canada is adopting a multi-year levels plan that will cover a three year period. Ranges for 2019 and 2020 will be updated and announced by November 1 of the preceding calendar year (i.e., November 1, 2018 for the 2019 calendar year). Multi-year levels planning will contribute to the success of Canada’s immigration program by enabling IRCC, its federal and provincial and territorial partners, and stakeholders such as settlement service providers to better plan for projected permanent resident admissions.

Table 4: 2018-2020 Immigration Levels Plan

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Projected Admissions - Targets | 310,000 | 330,000 | 340,000 |

| Projected Admissions - Ranges | Low 2018 |

High 2018 |

Low 2019 |

High 2019 |

Low 2020 |

High 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal-selected Economic Programs, Provincial/Territorial Nominees, Family, Refugees, Humanitarian Entrants and Permit HoldersFootnote * | 262,100 | 300,100 | 268,500 | 316,500 | 278,500 | 326,500 |

| Quebec-selected Skilled Workers and BusinessFootnote ** | 27,900 | 29,900 | 31,500 | 33,500 | 31,500 | 33,500 |

| Total | 290,000 | 330,000 | 300,000 | 350,000 | 310,000 | 360,000 |

Section 2: Managing Temporary Migration

In addition to selecting permanent residents, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) processes applications for the following: the temporary entry of foreign workers, who are important to Canada’s economic growth; international students, who are attracted by the quality and diversity of Canada’s educational system; and visitors who come to Canada for personal or business travel.

These temporary residents contribute to Canada’s economic development by filling gaps in the labour market, enhancing trade, purchasing goods and services, and increasing cultural links.

IRCC’s global processing network handles both permanent and temporary resident applications. While IRCC plans admission ranges for permanent residents, temporary resident applications are processed according to demand.

Temporary Workers

The entry of temporary foreign workers requiring a work permit is facilitated by the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFW) and the International Mobility Program (IMP). For further information on these programs, please visit the IRCC website.

In 2016, a total of 78,535 work permits were issued under the TFW Program, which includes caregivers, agricultural workers and other workers who require a Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA). In 2016, as in 2015, approximately 20% of work permits issued were for females and 80% were for males. In 2014, these figures were 26% for females and 74% for males.

Also, 208,582 work permits were issued under the IMP in 2016, which includes foreign workers who do not require an LMIA. The proportion of work permits issued for females under the IMP has increased slightly in recent years, from 42% in 2014 and 2015, to 44% in 2016. However, work permits issued for males still comprise the majority: 58% in 2014 and 2015, and 56% in 2016.

Transitions from Temporary Foreign Worker to Permanent Resident

In 2016, Canada admitted as permanent residents 41,623 individualsFootnote 10 who had previously held a work permit under the TFW Program or IMP. Of this number, 31,672 were principal applicants and the remainder were spouses/partners and dependants of principal applicants. The majority of principal applicants were male; in the last three years (including 2016), approximately 37% of principal applicants who transitioned to permanent resident status were female and the rest (approximately 63%) were male.

International Students

Canada is an attractive destination for international students, ranking in the top 10 global international study destinations. International students contribute to the cultural, social and economic landscape of Canada. They add an estimated $15 billion a year to Canada’s economy, and many are viewed as ideal candidates for permanent residency given their language proficiency, Canadian education credentials and Canadian work experience.

In 2016, more than 266,000 individuals held a study permit as an international student; 46% were female and 54% were male. While the total number of international students has been increasing in recent years, the proportion of females and males has remained generally constant over all three years.

Transitions from International Students to Permanent Residents

In 2016, Canada admitted as permanent residents 8,246 individualsFootnote 11 who had previously held a study permit as an international student. Of this number, 3,553 were principal applicants and the remainder were spouses/partners and dependants of principal applicants. In the last three years (including 2016), there has been near proportional parity between female and male principal applicant admissions who were previously international students; 51% were female and 49% were male in 2016.

Visitors

IRCC facilitates the entry of visitors, whether as tourists, vacationers visiting friends or family members, or business travellers. Tourists contribute to the economy by creating a demand for services in the hospitality sector. Business visitors allow Canadian companies and entrepreneurs to benefit from their specialized expertise and international ties.

Canada receives international visitors annually, including tourists and business visitors as temporary residents. In 2015, international tourism injected $17.2 billion into Canada’s economy. As of the end of 2016, citizens from 52 countries and territories were able to travel to Canada without a temporary resident visa. In terms of visa policy changes that year, the visa requirement for Mexican citizens was lifted on December 1, 2016.

In 2016, a total of 1,347,966 applications for individuals wanting to visit Canada were approved (52% for females and 48% for males). The female/male ratio for applications approved has remained the same for the last three years.

International visitors can hold a multiple entry visa, which lets them travel to Canada for six months at a time, as many times as desired, and is valid for up to 10 years. In 2016, Canada approved 1,261,515 multiple entry visa applications, 53% of which were submitted by female applicants and 47% by males. While the total number of approved multiple entry visa applications has increased by around 24% between 2014 and 2016, the female/male ratio of approved applications has remained fairly constant for the last three years.

Canada requires an Electronic Travel Authorization for visa-exempt foreign nationals (except United States citizens) travelling to, or transiting through Canada via air travel. The authorization is electronically linked to their passport and is valid for up to five years. Although it came into effect on March 15, 2016, Canada began to fully enforce the electronic travel authorization requirement as a pre-departure obligation on November 10, 2016. In 2016, Canada approved more than 2,570,000 electronic travel authorization applications; 49% were for females and 51% were for males.

Public Policy Exemptions for a Temporary Purpose

In 2016, a total of 596 applications for temporary residence were granted under the public policy authority provided in subsection 25.2(1) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) for certain inadmissible foreign nationals to facilitate their temporary entry into Canada as visitors, students or workers. Of these cases, 30% were for female applicants and 68% were for malesFootnote 12. The proportion of females to males has averaged 28% and 72% respectively in the last three years. This public policy has been in place since September 2010 to advance Canada’s national interests while continuing to ensure the safety of Canadians.

Temporary Resident Permits

Under subsection 24(1) of IRPA, designated officers of IRCC and the Canada Border Services Agency are authorized to issue temporary resident permits (TRPs) to foreign nationals whom they believe are inadmissible or who do not meet the requirements of the Act and where it is justified under the circumstances. For example, a TRP may be issued for reasons of national interest or for compelling humanitarian and compassionate reasons. TRPs are issued for a limited period of time and are subject to cancellation at any time.

IRCC continues to support the Government of Canada’s multifaceted efforts to combat human trafficking. Since May 2006, immigration officers have been authorized to issue TRPs to foreign nationals who may be victims of this crime so that they have a period of time to remain in Canada legally and consider their options. In 2016, IRCC issued 59 TRPs to victims of human trafficking (39% to females and 61% to males), and 8 TRPs to their dependants (25% to females and 75% to males). In the last three years, the female/male ratio of TRPs issued to victims of human trafficking has fluctuated considerably; in 2015, a full 70% of the permits were issued to female victims and 30% to male victims; in 2014, female victims accounted for 44% of permits, while males accounted for 56%.

Table 5 illustrates the number of TRPs issued in 2016, categorized according to grounds of inadmissibility under IRPA. In 2016, a total of 10,568 permits were issued. Of this number, 428 TRPs were authorized under instruction of the Minister (38% to females and 62% to males).

| Description of Inadmissibility | Provision under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act | Number of Permits in 2016 | Number of Females | Number of Males |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Security (espionage, subversion, terrorism) | 34(1)(a), (b), (c), (d), (e) and (f) | 9 | 1 | 8 |

| Human or International Rights Violations | 35(1)(a), (b) and (c) | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Serious Criminality (convicted of an offence punishable by a term of imprisonment of at least 10 years) | 36(1)(a), (b) and (c) | 587 | 53 | 534 |

| Criminality (convicted of a criminal act or of an offence prosecuted either summarily or by way of indictment) | 36(2)(a), (b), (c) and (d) | 5,243 | 734 | 4,509 |

| Organized Criminality | 37(1)(a) or (b) | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Health Grounds (danger to public health or public safety, excessive burden) | 38(1)(a), (b) and (c) | 21 | 8 | 13 |

| Financial Reasons (unwilling or unable to support themselves or their dependants) | 39 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Misrepresentation | 40(1)(a), (b), (c) and (d) | 33 | 13 | 20 |

| Non-compliance with Act or Regulations (e.g., no passport, no visa, work/study without permit, medical/criminal check to be completed in Canada, not examined on entry)Footnote * | 41(a) and (b) | 4,618 | 1,830 | 2,788 |

| Inadmissible Family Member | 42(a) and (b) | 46 | 25 | 21 |

| No Return Without Prescribed Authorization | 52(1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 10,568 | 2,666 | 7,902 |

Source: IRCC Cognos-Enterprise Data Warehouse as of July 10, 2017.

Note: The statistics in this table include the number of TRPs used to enter or remain in Canada in 2016.

Use of the Negative Discretion Authority

Subsection 22.1(4) of IRPA requires the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship to report annually on the number of declarations made under the negative discretion authority of subsection 22.1(1) of IRPA. This allows the Minister to make a declaration that, on the basis of public policy considerations, a foreign national may not become a temporary resident for a period of up to three years. During 2016, there were no declarations made under subsection 22.1(1).

Section 3: Federal-Provincial/Territorial Partnerships

Jurisdiction over immigration is a joint responsibility under section 95 of the Constitution Act, 1867, and effective collaboration between the Government of Canada and the provinces and territories is essential for the successful management of Canada’s immigration system.

Under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) and the Department of Citizenship and Immigration Act, the Minister for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) has the authority, with the approval of the Governor in Council, to enter into agreements with the provinces and territories to facilitate the coordination and implementation of immigration policies and programs. Table 6 below provides a list of the key bilateral agreements currently in force, with their signing and expiry dates. Framework agreements with eight provinces and one territory highlight immigration as a key area for bilateral collaboration and formalize how governments work together on this issue. Agreements for a Provincial Nominee Program (PN) are also in place with 11 jurisdictions (Yukon Territory, Northwest Territories and all provinces except Quebec), either as an annex to a framework agreement or as a stand-alone agreement.

Under the PN Program, provinces and territories have the authority to nominate individuals as permanent residents to address specific labour market and economic development needs. Table 7 presents the breakdown of permanent residents admitted in 2016 by province or territory of destination and immigration category. Under the Canada-Québec Accord relating to Immigration and Temporary Admission of Aliens, Quebec has full responsibility for the selection of immigrants (except Family Class and in-Canada refugee claimants), as well as the sole responsibility for delivering reception and integration services, supported by an annual grant from the federal government. Quebec also establishes its own immigration levels, develops its own related policies and programs, and legislates, regulates and sets its own standards. The federal government is responsible for establishing admission requirements, setting national immigration levels, defining immigration categories, determining refugee claims within Canada, reuniting families and establishing eligibility criteria for settlement programs in the other provinces and territories. In 2015 and 2016, IRCC engaged the Government of Quebec frequently and at all levels to advance common immigration priorities.

| Agreement | Date Signed | Expiry Date |

|---|---|---|

| Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Immigration Agreement | July 31, 2016 | July 31, 2021 |

| Agreement for Canada-Prince Edward Island Co-operation on Immigration | June 13, 2008 | Indefinite |

| Canada-Nova Scotia Co-operation on Immigration | September 19, 2007 | Indefinite |

| Canada-New Brunswick Immigration Agreement | March 30, 2017 | March 30, 2022 |

| Canada-Québec Accord relating to Immigration and Temporary Admission of Aliens | February 5, 1991 | Indefinite |

| Canada-Ontario Agreement on Foreign Workers | June 17, 2015 | June 16, 2020 |

| Canada-Ontario Agreement on Provincial Nominees | May 27, 2015 | May 26, 2020 |

| Canada-Manitoba Immigration Agreement | June 6, 2003 | Indefinite |

| Canada-Saskatchewan Immigration Agreement | May 7, 2005 | Indefinite |

| Agreement for Canada-Alberta Cooperation on Immigration | May 11, 2007 | Indefinite |

| Canada-British Columbia Immigration Agreement | April 7, 2015 | April 6, 2020 |

| Agreement for Canada-Yukon Co-operation on Immigration | February 12, 2008 | Indefinite |

| Canada-Northwest Territories Agreement on Territorial Nominees | September 26, 2013 | September 25, 2018 |

Table 7: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2016, by Destination and Immigration Category

| Immigration Category | NL | PE | NS | NB | QC | ON | MB | SK | AB | BC | NT | NU | YT | Not Stated | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal Economic – SkilledFootnote 13 | 171 | 25 | 720 | 163 | 0 | 31,363 | 624 | 848 | 16,510 | 9,517 | 29 | 9 | 22 | 0 | 60,001 |

| Federal Economic – CaregiversFootnote 14 | 28 | 0 | 59 | 29 | 1,110 | 9,324 | 96 | 222 | 3,828 | 3,736 | 26 | 10 | 8 | 0 | 18,476 |

| Federal Economic – BusinessFootnote 15 | 2 | 9 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 514 | 11 | 0 | 21 | 295 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 867 |

| Provincial Nominee | 455 | 1,932 | 2,590 | 2,448 | 0 | 3,911 | 9,958 | 9,902 | 8,066 | 6,759 | 63 | 0 | 89 | 0 | 46,173 |

| Quebec Skilled Workers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25,858 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25,858 |

| Quebec Business Immigrants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4,634 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4,634 |

| Total Economic | 656 | 1,966 | 3,384 | 2,640 | 31,602 | 45,112 | 10,6896 | 10,972 | 28,425 | 20,307 | 118 | 19 | 119 | 0 | 156,009 |

| Immigration Category | NL | PE | NS | NB | QC | ON | MB | SK | AB | BC | NT | NU | YT | Not Stated | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouses, Partners and Children | 171 | 81 | 588 | 303 | 9,788 | 25,929 | 1,936 | 1,733 | 10,296 | 9,639 | 43 | 14 | 69 | 0 | 60,590 |

| Parents and Grandparents | 21 | 1 | 66 | 30 | 1,266 | 9,068 | 437 | 221 | 2,616 | 3,298 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 17,041 |

| Family – OtherFootnote 16 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 72 | 153 | 6 | 7 | 100 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 375 |

| Total Family | 193 | 82 | 654 | 333 | 11,126 | 35,150 | 2,379 | 1,961 | 13,012 | 12,973 | 53 | 16 | 74 | 0 | 78,006 |

| Immigration Category | NL | PE | NS | NB | QC | ON | MB | SK | AB | BC | NT | NU | YT | Not Stated | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protected Persons in Canada and Dependants Abroad | 12 | 0 | 33 | 7 | 2,274 | 8,163 | 70 | 67 | 922 | 560 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 12,116 |

| Government-Assisted Refugees | 189 | 124 | 889 | 1,475 | 2,960 | 9,826 | 1,271 | 1,392 | 3,007 | 2,388 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 23,523 |

| Blended Visa Office-Referred Refugees | 82 | 27 | 272 | 187 | 10 | 2,360 | 320 | 163 | 353 | 643 | 6 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 4,435 |

| Privately Sponsored Refugees | 53 | 113 | 229 | 17 | 4,172 | 7,512 | 2,069 | 265 | 2,877 | 994 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 52 | 18,363 |

| Total Protected Persons and Refugees | 336 | 264 | 1,423 | 1,686 | 9,416 | 27,861 | 3,730 | 1,887 | 7,159 | 4,585 | 12 | 1 | 17 | 60 | 58,437 |

| Immigration Category | NL | PE | NS | NB | QC | ON | MB | SK | AB | BC | NT | NU | YT | Not Stated | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humanitarian and OtherFootnote 17 | 3 | 1 | 22 | 16 | 1,094 | 1,896 | 23 | 36 | 601 | 206 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 3,913 |

| Total Humanitarian | 3 | 1 | 22 | 16 | 1,094 | 1,896 | 23 | 36 | 601 | 206 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 3,913 |

| Immigration Category | NL | PE | NS | NB | QC | ON | MB | SK | AB | BC | NT | NU | YT | Not Stated | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1,118 | 2,313 | 5,483 | 4,675 | 53,238 | 110,019 | 16,821 | 14,856 | 49,197 | 38,071 | 185 | 36 | 211 | 72 | 296,365 |

| Percentag | 0.38% | 0.78% | 1.85% | 1.58% | 17.97% | 37.13% | 5.68% | 5.01% | 16.6% | 12.85% | 0.06% | 0.01% | 0.07% | 0.02% | 100% |

Source: IRCC Permanent Resident Data as of July 31, 2017. Due to ongoing data reviews and quality checks, numbers found in this table will differ slightly from previously reported tables and analysis as the data was extracted on different dates.

Section 4: Gender-based Analysis Plus of the Impact of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

The Government of Canada is committed to supporting the full implementation of Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+) across federal departments and agencies. Recently, the Government has applied increasing rigour toward the application of GBA+ in its policies, programs and activities. Gender equality is a core Canadian value and is enshrined in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Ministerial mandate letters include a commitment to gender parity across the federal government.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) has a long-standing legislative commitmentFootnote 18 to include GBA+ assessments of the impact of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) in its Annual Report. IRCC also has a Policy on Gender-based Analysis (2011) which aims to ensure that “the needs of diverse groups of women and men, girls and boys are considered in the development and implementation of policies and programs across IRCC’s business lines.” Gender considerations are part of the Department’s work, including an increasing focus on aspects of gender-based vulnerability within the immigration or migration context.

Last year, IRCC committed to providing more sex-disaggregated information and improving GBA+ reporting in its Annual Report to Parliament. As a result, the 2016 Annual Report incorporates sex-disaggregated data throughout.Footnote 19 This GBA+ section now focuses on more enhanced gender and other intersectional identity considerations in immigrant outcomes, economic immigration, family reunification, resettlement and settlement.

In future years, IRCC intends to continue to deepen and enhance the GBA+ section of the Annual Report, including more comprehensive data analysis and research, as well as further work on themes such as gender and intersectionality in Express Entry, vulnerability from an immigration lens, and protection to vulnerable groups in situations of armed conflict and state fragility. These assessments aim to strengthen IRCC’s work toward more positive, gender-sensitive results in the immigration system.

Gender-based Analysis Plus

GBA+ is an analytical tool used to assess how various groups of women, men and gender-diverse people may experience policies, programs and initiatives. The “plus” in GBA+ acknowledges that GBA+ goes beyond biological (sex) and socio-cultural (gender) differences. We all have multiple identity factors that intersect to make us who we are; GBA+ also considers many other identity factors, like race, ethnicity, religion, age, and mental or physical disability.

In addition to IRCC’s application of GBA+, research and analysis done by academics, international organizations or other federal departments on immigrants and gender continue to inform and enrich the Department’s work.

Immigrant Outcomes – Gender-Based Highlights

Immigrants are joining a Canadian labour market and society where women have made great strides in education and economic participation. Canadian women are increasingly educated and occupy a greater presence in Canada’s work force. Today, women account for 47% of the labour force, compared to 38% in 1976. This, along with real wage gains, has led to a significant increase in the earnings of women. However, the gender wage gap (that is, earnings of women relative to men) persists. While it has declined over the last few decades, Canada ranked 28th out of 34 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development countries in terms of having the largest gender wage gap in full-time, full-year earnings among employees and the self-employed in 2014.

Immigrant women therefore join Canadian society within this context of an increased female labour force and greater wage gap.

Economic and social outcomes of immigrants are complex, with many interrelated and inter-dependent factors that are largely outside the control of the immigration program or the federal government. Factors can include Canada’s economic performance, labour market needs in various regions of the country, educational and community infrastructure at provincial and municipal levels, the network of social supports available in communities, and individual behaviour. The longer immigrants spend time in Canada, the more their economic outcomes tend to improve and draw closer to those of persons born in Canada.

Overall, economic immigrants have generally positive economic outcomes since principal applicants are selected for their human capital and ability to integrate economically into Canada’s labour market. Soon after landing in Canada, the average employment earnings of economic principal applicants surpass the Canadian average and generally increase over time. In comparison, family-sponsored immigrants and refugees may have lower human capital and entry into the Canadian labour market may be difficult. However, there are further labour market gaps when disaggregating outcomes between immigrant men and women. On average, and compared to their Canadian-born counterparts, female immigrants have lower labour market rates, such as labour market participation rate and employment rate.Footnote 20 While these rates for immigrant males generally catch up to those of the Canadian-born over time, a persistent gap exists between female immigrants and their Canadian-born counterparts.

For example, in 2015, unemployment rates were 10.4% for recent female immigrants and 15.1% for very recent female immigrants, compared to 5.7% for Canadian-born females. For male immigrants, unemployment rates were 7.8% for recent male immigrants and 9.7% for very recent male immigrants, compared to 7.7% for Canadian-born males.

In terms of average employment earnings, immigrants in general see earnings increase with more years spent in Canada, although entry earnings and earnings growth rates differ considerably between immigrant groups and when disaggregated by sex.

For economic immigrants, male principal applicants have higher average entry employment earnings and higher average employment earnings than their female counterpartsFootnote 21.

- Immigrant male average entry employment earnings for the 2003-2012 landing cohorts ranged from $30,000 to $45,000. Their average employment earnings during the same period were $52,300 to $62,700Footnote 22. Average employment earnings for Canadian male taxpayers ranged from $52,800 to $54,000 during the 2006-2013 periodFootnote 23.

- Female economic principal applicants had average entry employment earnings that ranged from $24,000 to $29,000 for the 2003-2012 landing cohorts. Average employment earnings for Canadian female taxpayers ranged from $33,300 to $36,300 during the 2006-2013 period.

For Family Class immigrants and refugees, the gap between female and male immigrants and their Canadian-born counterparts is larger. The likelihood of being at the lower end of the income scale (under $20,000) is significantly higher for Family Class immigrants and refugees, compared to economic principal applicants: 49% of Family Class immigrants and 45% of refugees earned under $20,000 in 2014, compared to 34% of all Canadians.

- For female Family Class immigrants, the average entry employment earnings ranged from $14,100 to $16,200 for the 2003-2012 landing cohorts. The most recent cohort to attain the average Canadian female taxpayers’ employment earnings was the 1991 cohort (22 years to catch up).

- For male Family Class immigrants, the average entry employment earnings ranged from $23,800 to $26,000 for the 2003-2012 landing cohorts. The most recent cohort to attain the average Canadian male taxpayers’ employment earnings was the 1989 cohort (24 years to catch up).

- For female refugees, the average entry employment earnings ranged from $13,300 to $15,600 for the 2003-2012 landing cohorts. The most recent cohort to reach the average Canadian female taxpayer’s employment earnings was the 1990 cohort (23 years).

- For male refugees, the average entry employment earnings ranged from $19,800 to $23,000 for the 2003-2012 landing cohorts. The most recent cohort to reach the average Canadian male taxpayers’ employment earnings was the 1983 cohort (30 years).

On rates of social assistance among immigrants, their immigration category and length of time spent in Canada are the key factors. Overall, and on average, approximately 9% of immigrants in 2013 reported using social assistance one year after landing in Canada. Although these rates decreased for all immigrants with more time spent in Canada, female immigrants generally had a slightly higher incidence of social assistance than males five years after landing in Canada.

- For female immigrants, the incidence of social assistance dropped from 9.9% one year after landing to 7.5% five years after landing.

- For male immigrants, the incidence of social assistance dropped from 9.1% one year after landing to 6% five years after landing.

Among immigrant categories, economic principal applicants have a low incidence of social assistance (6.9% of females and 6.6% of males one year after landing, and then dropping to 3% for both females and males five years after landing). These low rates of social assistance reflect that it takes time to find employment and economically establish in Canada, even for those selected for their human capital and economic potential. Refugees have the highest incidence of social assistance among immigrants, and female refugees have higher incidence of social assistance than males. However, both incidence rates also decrease over time. It is key to note that social assistance incidence captures the income assistance from the Resettlement Assistance Program for government-supported refugees (Government-Assisted Refugees and Blended Visa Office Referred Refugees) for the first year after landing.

- For female refugees, the incidence of social assistance dropped from 51.3% one year after landing to 37.5% five years after landing.

- For male refugees, the incidence of social assistance dropped from 41.1% one year after landing to 27.3% five years after landing.

IRCC is mindful of the gaps between immigrants and the Canadian-born in economic outcomes, as well as the gender gap between female and male immigrants. IRCC will continue to monitor the economic outcomes of immigrants closely, particularly the gender gap, and to enhance the Settlement Program through innovative ways to position and support immigrants to achieve success, in cooperation with service providers and the provinces and territories.

Economic Immigration – Gender-based Highlights

Economic Class immigration is based on IRPA and has three main objectives: to select immigrants to build a skilled work force; to address immediate and longer-term labour market needs; and to support national and regional labour force growth.

In economic immigration programs, principal applicants are generally selected for their human capital and their ability to bring the economic benefits of immigration to Canada or particular regions of Canada, regardless of their sex or gender. However, the gender trends of immigrants coming to Canada may reflect the historically gendered nature of various labour sectors in Canada, such as caregiving, business and skilled trades.

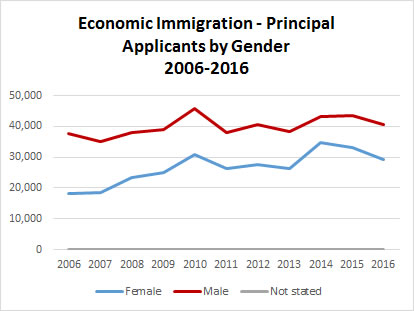

Generally, females have been under-represented as total economic principal applicants (see Figure 1), which may reflect the historically gendered nature of labour market sectors that attract economic immigrants, such as engineering and IT.

Figure 1- Economic Immigration – Principal Applicants by Gender 2006-2016

Text version: Figure 1 - Economic Immigration – Principal Applicants by Gender 2006-2016

| Gender | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Jan-Jun 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 18,128 | 18,619 | 23,345 | 24,928 | 30,746 | 26,241 | 27,689 | 26,466 | 34,849 | 33,139 | 29,186 | 17,528 |

| Male | 37,578 | 35,165 | 37,918 | 39,036 | 45,762 | 38,069 | 40,499 | 38,295 | 43,291 | 43,531 | 40,535 | 22,428 |

| Not stated | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 55,706 | 53,784 | 61,263 | 63,964 | 76,508 | 64,310 | 68,188 | 64,763 | 78,140 | 76,672 | 69,722 | 39,956 |

Recently, there has been a narrowing in the gender gap with respect to female economic principal applicants. For instance, in 2016, a full 42% of total principal applicants from the Economic Class were female, compared to 33% in 2006. The gender gap in 2016 was 16 percentage points compared to 35 percentage points in 2006. However, the reduction in the gender gap may be due to the higher number of caregiver admissions as set by the Immigration Levels Plan, following the termination of the Live-in Caregiver Program, which was succeeded by the Caregiver Program. Caregiver principal applicants are historically and predominantly female, which has bolstered the proportion of female economic principal applicants.

IRCC continues to monitor the gender aspects of economic immigration programs.

Family Reunification – Gender-based Highlights

There is a long tradition of supporting family reunification in Canadian immigration, where Canadians and permanent residents can be reunited with certain members of their family through sponsorship. Persons who can be sponsored include an individual’s spouse, common-law partner (including same-sex partner), conjugal partner, dependent children, parents, grandparents, children adopted from abroad, and other relatives in special circumstances. Family reunification is a non-discretionary immigration stream, where sponsors name their family members as individuals for admission to Canada. Data in past years suggest that more females are sponsored as spouses/partners (whether as different sex or same sex couples) and as parents/grandparents.

IRCC continues to monitor the gender aspects of family reunification, particularly in terms of vulnerability. In 2016, IRCC conducted GBA+ assessments of two proposals related to families: one pertaining to changing the age of dependants, and the other involving the repeal of conditional permanent residence for sponsored spouses.

Changing the Age of Dependants

The definition of “dependent child” in the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations is used to determine whether a child may be eligible to immigrate as an immediate family member of a principal applicant in all immigration classes, as well as a sponsored child in family reunification.

In 2016, a GBA+ analysis was conducted of the proposal to increase the age of dependent children from “under 19” years to “under 22", which was a Ministerial mandate commitment. The GBA+ analysis allowed IRCC to consider the diversity of young people who would be affected by the proposed regulatory amendment, such as those with physical or mental disabilities. Impacts were primarily noted to be beneficial, as the proposal would allow a greater number of young people to be positively affected.

It was estimated that the annual number of additional young people who may qualify for permanent residency could be approximately 5,000. These would be children of applicants for permanent residency in the age range of 19 to 21 years; some would be children in that age range who are sponsored in the Family Class by a parent. Identified diversity factors included immigration and refugee program, country of origin, gender and level of education completed. It was estimated that about 54% of these individuals would be male.

The regulatory changes were introduced on May 2, 2017, and will come into force on October 24, 2017.

Repeal of Conditional Permanent Residence

In 2016, as part of a Ministerial mandate commitment, IRCC developed a proposal to remove a regulatory requirement for sponsored spouses and partners of Canadian citizens and permanent residents to live with their sponsor for two years as a condition to maintaining their permanent resident status.

The analysis recognized that a sponsored spouse or partner can be vulnerable for many reasons, including gender, age, official language proficiency, isolation and financial dependence, and that these factors can create an imbalance between the sponsor and their spouse or partner. It was further assessed that the conditional permanent residence two-year co-habitation requirement could compound these vulnerabilities in situations of domestic abuse. Noting that women made up a majority (70%) of affected individuals who submitted requests to IRCC for an exception to the condition on the basis of abuse or neglect, IRCC assessed that this regulatory requirement may potentially result in vulnerable spouses and partners remaining in abusive relationships out of fear of losing their permanent resident status in Canada.

The conditional permanent residence requirement was repealed on April 18, 2017.

Resettlement and Protected Persons – Gender-based Highlights

Refugees and persons in need of protection are people with a well-founded fear of persecution, risk of torture, risk to their life or risk of cruel and unusual treatment or punishment in their home country.

In some instances, particularly during situations of conflict or emergencies, certain groups of women and men are at risk of sexual and gender-based violence. The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) refers to this type of violence as "any act that is perpetrated against a person’s will and is based on gender norms and unequal power relationships. It encompasses threats of violence and coercion. It can be physical, emotional, psychological, or sexual in nature, and can take the form of a denial of resources or access to services. It inflicts harm on women, girls, men and boys."

IRCC’s refugee resettlement programs take into account gender and diversity considerations, including an applicant’s exposure to sexual and gender-based violence. IRCC recognizes that survivors may face particular vulnerabilities including additional or unique integration barriers such as low literacy and education levels as well as greater physical and mental health needs.

IRCC provides health-care coverage to refugees and protected persons, which includes coverage for mental health services by general practitioners, clinical psychologists, psychotherapists, and counselling therapists. Translation support for mental health services are also covered so clients can seek services without relying on family members or sponsors which means that their privacy is maintained. The Department also includes maternal, child health services and medical treatment in the health-care coverage.

IRCC continues to develop and deliver enhanced training to officials to improve the Department’s policies to provide protection. New training for visa officers who process refugee applications include a GBA+ framework through which to make decisions on refugee resettlement applications received abroad. Specifically, the training provides tools and procedures for officers to assess the gendered aspects of applications as well as the implications of the decisions they make. The training advances four key messages: gender is a legitimate ground for fearing persecution; women often experience persecution differently than men; persecution based on sexual orientation also has a gender dimension and; there are special procedures and programs to ensure women refugees receive protection on an equal basis with men.

IRCC continues to ensure that helping vulnerable and marginalized populations across the world remains at the core of Canada’s refugee and protected persons programs, including protection from gender-based violence due to sex, sexual orientation and gender identity.

Women at Risk program

In terms of programs, the Women at Risk program recognizes the unique vulnerabilities of refugee women and girls, and is designed to offer resettlement opportunities to women in perilous or permanently unstable situations and in situations where urgent or expedited processing is necessary. Women at Risk cases can be referred by the UNHCR, which also has a specific Women at Risk resettlement submission category. The UNHCR was involved in referring Syrian women at risk for resettlement to Canada.

Women at risk with special needs may be resettled to Canada under the Joint Assistance Sponsorship program, which partners refugees with private sponsors to provide additional settlement and emotional support and allows for two years of income support (as opposed to the typical 12 months). In 2016, 408 females resettled to Canada under the Women at Risk program.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity and Expression Refugees

Individuals fleeing persecution for reasons of sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression can qualify as refugees under the 1951 Refugee Convention. In 1993, Canada became one of the first countries to extend refugee protection to those facing persecution for their sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression. IRCC relies primarily on the UNHCR as well as other recognized referral organizations to identify and refer the most vulnerable of refugees for resettlement. Recently, as part of Canada’s commitment to resettle 25,000 Syrian refugees, Canada asked the UNHCR to prioritize vulnerable refugees including women at risk and persons identified as vulnerable due to membership in the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and/or Two-Spirited community.

Asylum

The in-Canada asylum system provides gender-specific protection to in-Canada refugee claimants who have fled conflicts or fragile states. IRCC has developed specific program delivery instructions with respect to processing in-Canada claims for refugee protection of minors and other vulnerable persons. Provisions include ensuring a vulnerable person’s physical comfort; being sensitive to cultural and gender issues; and efforts to allow victims of sexual violence the option of choosing the gender of the interviewing officer.

The Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB), which hears asylum claims, has a set of specific guidelines on how to treat vulnerable groups, including women refugee claimants fearing gender-related persecution. In May 2017, the IRB also announced a new guideline to promote greater understanding of cases involving sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and the harm individuals may face due to their non-conformity with socially accepted norms. This guideline aims to promote a greater understanding of the diversity and complexity that can be associated with having diverse sexual orientation and gender identity and expression; to establish guiding principles for decision-makers in adjudicating cases; and to provide parties with a clearer understanding of what to expect when appearing before the IRB.

Settlement and Integration of Newcomers – Gender-based Highlights

The Settlement Program serves all permanent resident newcomers to support successful integration into Canadian society and the economy. IRCC recognizes the significant contributions that newcomer women make to the economic, social, civic and cultural life of Canada, and their key role in the settlement and integration of the family unit once they have arrived here. Migration to Canada can bring many opportunities for women, but it can also include distinct and multiple challenges, such as navigating a new language, work transitions, child-care responsibilities, developing new networks and shifts in family dynamics.

To address these challenges, considerations for gender, age, identity, and circumstances of migration are included in the design and delivery of Settlement Program policies. IRCC funds through the Settlement Program a range of targeted settlement services that can be accessed by newcomer women (refugee and immigrant women) such as mentoring, information and orientation on rights and responsibilities, women-only employment opportunities and language supports, and family and gender-based violence prevention support. In addition, child-minding and transportation services are offered to ensure that mothers—who may be primarily responsible for child care and feel unable to physically attend meetings or courses—are able to access these services.

In 2016, of the 410,000 clients who accessed at least one Settlement ProgramFootnote 24 service in Canada (outside of Quebec), over half (57%) were women. Women used every type of settlement service at a higher rate than men, particularly language training (66% women).

The main settlement needs identified by women through needs assessment and referral services in 2016 were to increase knowledge of community and government services (79%), and to increase access to local community services (54%). Among woman participants, 39% indicated the need to improve their language skills; of this number, 36% wanted to improve their language skills to find employment. Of the women who accessed needs assessment and referral services, 23% indicated a need to find employment, 13% wanted to improve other skills in support of finding employment, 35% indicated a need to increase knowledge of working in Canada and 15% indicated a need to develop professional networks.