ARCHIVED - Departmental Performance Report

For the period ending

March 31, 2014

Citizenship and Immigration Canada

Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Minister’s Message

- Section I: Organizational Expenditure Overview

- Organizational Context

- Section II: Analysis of Programs by Strategic Outcome

- Strategic Outcome 1: Migration of permanent and temporary residents that strengthens Canada’s economy

- Program 1.1: Permanent Economic Residents

- Sub-Program 1.1.1: Federal Skilled Workers

- Sub-Program 1.1.2: Quebec Skilled Workers

- Sub-Program 1.1.3: Provincial Nominees

- Sub-Program 1.1.4: Live-in Caregivers

- Sub-Program 1.1.5: Canadian Experience Class

- Sub-Program 1.1.6: Federal Business Immigrants

- Sub-Program 1.1.7: Quebec Business Immigrants

- Program 1.2: Temporary Economic Residents

- Sub-Program 1.2.1: International Students

- Sub-Program 1.2.2: Temporary Foreign Workers

- Strategic Outcome 2: Family and humanitarian migration that reunites families and offers protection to the displaced and persecuted

- Program 2.1: Family and Discretionary Immigration

- Sub-Program 2.1.1: Spouses, Partners and Children Reunification

- Sub-Program 2.1.2: Parents and Grandparents Reunification

- Sub-Program 2.1.3: Humanitarian and Compassionate and Public Policy Considerations to Address Exceptional Circumstances

- Program 2.2: Refugee Protection

- Sub-Program 2.2.1: Government-Assisted Refugees (GARs)

- Sub-Program 2.2.2: Privately Sponsored Refugees (PSRs)

- Sub-Program 2.2.3: In-Canada Asylum

- Sub-Program 2.2.4: Pre-Removal Risk Assessment (PRRA)

- Strategic Outcome 3: Newcomers and citizens participate to their full potential in fostering an integrated society

- Program 3.1: Settlement and Integration of Newcomers

- Sub-Program 3.1.1: Foreign Credentials Referral

- Sub-Program 3.1.2: Settlement

- Sub-Sub-Program 3.1.2.1: Information and Orientation

- Sub-Sub-Program 3.1.2.2: Language Training

- Sub-Sub-Program 3.1.2.3: Labour Market Access

- Sub-Sub-Program 3.1.2.4: Welcoming Communities

- Sub-Sub-Program 3.1.2.5: Contribution to British Columbia for Settlement and Integration

- Sub-Sub-Program 3.1.2.6: Support for Official Language Minority Communities

- Sub-Program 3.1.3: Grant to Quebec

- Sub-Program 3.1.4: Immigration Loan

- Sub-Program 3.1.5: Refugee Resettlement Assistance Program

- Program 3.2: Citizenship for Newcomers and All Canadians

- Sub-Program 3.2.1: Citizenship Awareness

- Sub-Program 3.2.2: Citizenship Acquisition, Confirmation and Revocation

- Program 3.3: Multiculturalism for Newcomers and All Canadians

- Sub-Program 3.3.1: Multiculturalism Awareness

- Sub-Program 3.3.2: Federal and Public Institutional Multiculturalism Support

- Strategic Outcome 4: Managed migration that promotes Canadian interests and protects the health, safety and security of Canadians

- Sub-Program 4.1.1: Health Screening

- Sub-Program 4.1.2: Medical Surveillance Notification

- Sub-Program 4.1.3: Interim Federal Health

- Program 4.2: Migration Control and Security Management

- Sub-Program 4.2.1: Permanent Resident Status Documents

- Sub-Program 4.2.2: Visitors Status

- Sub-Program 4.2.3: Temporary Resident Permits

- Sub-Program 4.2.4: Fraud Prevention and Program Integrity Protection

- Sub-Program 4.2.5: Global Assistance for Irregular Migrants

- Program 4.3: Canadian Influence in International Migration and Integration Agenda

- Program 4.4: Passport

- Program 5.1: Internal Services

- Strategic Outcome 1: Migration of permanent and temporary residents that strengthens Canada’s economy

- Section III: Supplementary Information

- Section IV: Organizational Contact Information

- Appendix: Definitions

Foreword

Departmental Performance Reports are part of the Estimates family of documents. Estimates documents support appropriation acts, which specify the amounts and broad purposes for which funds can be spent by the government. The Estimates document family has three parts.

Part I (Government Expenditure Plan) provides an overview of federal spending.

Part II (Main Estimates) lists the financial resources required by individual departments, agencies and Crown corporations for the upcoming fiscal year.

Part III (Departmental Expenditure Plans) consists of two documents. Reports on Plans and Priorities (RPPs) are expenditure plans for each appropriated department and agency (excluding Crown corporations). They describe departmental priorities, strategic outcomes, programs, expected results and associated resource requirements, covering a three-year period beginning with the year indicated in the title of the report. Departmental Performance Reports (DPRs) are individual department and agency accounts of actual performance, for the most recently completed fiscal year, against the plans, priorities and expected results set out in their respective RPPs. DPRs inform parliamentarians and Canadians of the results achieved by government organizations for Canadians.

Additionally, Supplementary Estimates documents present information on spending requirements that were either not sufficiently developed in time for inclusion in the Main Estimates or were subsequently refined to account for developments in particular programs and services.

The financial information in DPRs is drawn directly from authorities presented in the Main Estimates and the planned spending information in RPPs. The financial information in DPRs is also consistent with information in the Public Accounts of Canada. The Public Accounts of Canada include the Government of Canada Consolidated Statement of Financial Position, the Consolidated Statement of Operations and Accumulated Deficit, the Consolidated Statement of Change in Net Debt, and the Consolidated Statement of Cash Flow, as well as details of financial operations segregated by ministerial portfolio for a given fiscal year. For the DPR, two types of financial information are drawn from the Public Accounts of Canada: authorities available for use by an appropriated organization for the fiscal year, and authorities used for that same fiscal year. The latter corresponds to actual spending as presented in the DPR.

The Treasury Board Policy on Management, Resources and Results Structures further strengthens the alignment of the performance information presented in DPRs, other Estimates documents and the Public Accounts of Canada. The policy establishes the Program Alignment Architecture of appropriated organizations as the structure against which financial and non-financial performance information is provided for Estimates and parliamentary reporting. The same reporting structure applies irrespective of whether the organization is reporting in the Main Estimates, the RPP, the DPR or the Public Accounts of Canada.

A number of changes have been made to DPRs for 2013−14 to better support decisions on appropriations. Where applicable, DPRs now provide financial, human resources and performance information in Section II at the lowest level of the organization’s Program Alignment Architecture.

In addition, the DPR’s format and terminology have been revised to provide greater clarity, consistency and a strengthened emphasis on Estimates and Public Accounts information. As well, departmental reporting on the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy has been consolidated into a new supplementary information table posted on departmental websites. This new table brings together all of the components of the Departmental Sustainable Development Strategy formerly presented in DPRs and on departmental websites, including reporting on the Greening of Government Operations and Strategic Environmental Assessments. Section III of the report provides a link to the new table on the organization’s website. Finally, definitions of terminology are now provided in an appendix.

Minister's Message

As Canada’s Citizenship and Immigration Minister, I am very pleased to present the Departmental Performance Report for 2013-2014.

This past year, my department and I continued our work to build a faster and more flexible immigration system that is better aligned with Canada’s economic needs. We did so, while also reuniting tens of thousands of loved ones and giving refuge to thousands of the world’s most vulnerable people. Indeed, all Canadians can be proud that Canada boasts one of the world’s most successful family reunification programs and most generous refugee systems.

Looking ahead, we will soon launch the new Express Entry application management system to actively recruit the talented, skilled workers whose skills are most needed in the Canadian labour market. Those chosen under Express Entry will be more likely to work immediately upon their arrival, and will get here much sooner than ever before. With the launch of Express Entry for many of our most popular immigration streams, we can be more responsive to the changing needs of employers and Canada’s economy. This will help reduce employer reliance on temporary foreign workers in favour of permanent immigration that responds to Canada’s labour market needs.

We will continue to build on the reforms to the International Mobility Programs that we announced in June 2014. A number of measures have been taken to reduce abuse of these programs and ensure they work in the best interests of Canadians. My department will continue to work with Employment and Social Development Canada to ensure that the Temporary Foreign Workers Program and the International Mobility Program are only used as intended: to fill labour shortages on a temporary basis when qualified Canadians are not available or there is a compelling rationale in Canada’s best interests.

We will continue to uphold our longstanding tradition of reuniting families. Since the Action Plan for Faster Family Reunification was launched in 2011, the Government has cut the backlog of parents and grandparents in half, and we expect to make further substantial progress by the end of 2015. To date, more than 40,000 families have discovered the ease and convenience of the Super Visa, which continues to be a wildly popular option allowing parents and grandparents to remain in Canada for up to two years at a time.

We will also continue to be a world-leader in resettling refugees and providing protection to the world’s most vulnerable populations. At a time where there are more displaced people around the world than at any other time since the Second World War, it is important that Canada’s refugee system works at its most effective. Our comprehensive reforms to the once-broken system are working and we will continue our efforts to provide refuge to those who most need Canada’s protection.

It is in Canada’s interest to ensure newcomers and refugees can successfully and quickly integrate into Canada’s labour market and Canadian communities. To that end, the Government of Canada will continue to invest in settlement services across Canada and expand pre-arrival employment and orientation services. Funding for settlement services in Canada has increased from less than $200 million in 2005-06 to approximately $600 million in 2013–2014. This is over and above the substantial funding we provide to the province of Quebec for immigration and settlement services there.

We continue to implement the measures contained in the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act. Passed by Parliament in June 2014, this legislation represents the most comprehensive set of reforms to the Citizenship Act in more than a generation. These will reinforce the value of Canadian citizenship and protect the integrity of our citizenship program while streamlining the application process and decreasing legacy backlogs. We expect to reduce processing times to less than one year by 2015-2016.

We continue to introduce new measures to support legitimate trade and travel. The launch of CAN+ and other facilitative travel programs for low-risk populations this past year will make it faster and easier for legitimate travellers in key global markets to get a visa to come to Canada. We are also modernizing our immigration network overseas and finding new ways to deliver better service to prospective visitors. The take-up, as measured by high volumes of multiple entry visas and record visitor visa issuance in many countries, speaks for itself. For Canada, the economic benefits of this are immense.

These are just some of the new ways in which we are making Canadian immigration more responsive to the needs of our economy. You can read more in the coming pages and be assured that the launch of Express Entry in the coming months will only contribute further to our country’s economy and to our collective prosperity.

I would like to close by thanking the dedicated employees who work in our offices across Canada and missions around the world for their efforts to further the goals outlined above and bring the benefits of global migration home to all Canadians.

Canada’s Citizenship and Immigration Minister

Section I: Organizational Expenditure Overview

Organizational Profile

Minister: Chris Alexander

Deputy Head: Anita Biguzs

Ministerial Portfolio:

Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism

Department: Department of Citizenship and Immigration

Special Operating Agency: Passport Canada

Statutory and Other Agencies: Citizenship Commission, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada

Crown Corporation: Canadian Race Relations Foundation

Enabling Instruments: Section 95 of the Constitution Act, 1867, the Citizenship Act, the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), the Canadian Multiculturalism Act and the Canadian Passport Order.

Year Established: 1994

Organizational Context

Raison d’être

In the first years after Confederation, Canada’s leaders had a powerful vision: to connect Canada by rail and make the West the world’s breadbasket as a foundation for the country’s economic prosperity. This vision meant quickly populating the Prairies, leading the Government of Canada to establish its first national immigration policies. Immigrants have been a driving force in Canada’s nationhood and its economic prosperity—as farmers settling lands, as workers in factories fuelling industrial growth, as entrepreneurs and as innovators helping Canada to compete in the global, knowledge-based economy.

Responsibilities

Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) selects foreign nationals as permanent and temporary residents and offers Canada’s protection to refugees. The Department develops Canada’s admissibility policy, which sets the conditions for entering and remaining in Canada; it also conducts, in collaboration with its partners, the screening of potential permanent and temporary residents to protect the health, safety and security of Canadians. Fundamentally, the Department builds a stronger Canada by helping immigrants and refugees settle and integrate into Canadian society and the economy, and by encouraging and facilitating Canadian citizenship. To achieve this, CIC operates 27 in-Canada points of service and 68 points of service in 61 countries.

CIC’s mandate is partly derived from the Department of Citizenship and Immigration Act. The Minister for Citizenship and Immigration Canada is responsible for the Citizenship Act of 1977 and shares responsibility with the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness for the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), which came into force following major legislative reform in 2002. CIC and the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) support their respective ministers in the administration and enforcement of IRPA. These organizations work collaboratively to achieve the objectives of the immigration and refugee programs.

In October 2008, responsibility for administration of the Canadian Multiculturalism Act was transferred to CIC from the Department of Canadian Heritage. Under the Act, CIC promotes the integration of individuals and communities into all aspects of Canadian society and helps to build a stronger, more cohesive society.

Jurisdiction over immigration is a shared responsibility between the federal, and the provincial and territorial governments under section 95 of the Constitution Act, 1867. Under section 91(25) of the Constitution Act, 1867, the federal government has jurisdiction over naturalization and aliens.

In July 2013, the primary responsibility for the Passport Program was transferred from the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada (DFATD) to CIC; Passport service delivery is now provided through Service Canada.

In August 2013, CIC assumed responsibility for International Experience Canada (IEC) – archived from DFATD. This transfer allowed the program to better align with government priorities and labour market demands in Canada by linking IEC to other immigration programs.

Strategic Outcomes and Program Alignment Architecture

- Strategic Outcome 1: Migration of permanent and temporary residents that strengthens Canada’s economy

- Program 1.1: Permanent Economic Residents

- Sub-Program 1.1.1: Federal Skilled Workers

- Sub-Program 1.1.2: Quebec Skilled Workers

- Sub-Program 1.1.3: Provincial Nominees

- Sub-Program 1.1.4: Live-in Caregivers

- Sub-Program 1.1.5: Canadian Experience Class

- Sub-Program 1.1.6: Federal Business Immigrants

- Sub-Program 1.1.7: Quebec Business Immigrants

- Program 1.2: Temporary Economic Residents

- Sub-Program 1.2.1: International Students

- Sub-program 1.2.2: Temporary Foreign Workers

- Program 1.1: Permanent Economic Residents

- Strategic Outcome 2: Family and humanitarian migration that reunites families and offers protection to the displaced and persecuted

- Program 2.1: Family and Discretionary Immigration

- Sub-Program 2.1.1: Spouses, Partners and Children Reunification

- Sub-Program 2.1.2: Parents and Grandparents Reunification

- Sub-Program 2.1.3: Humanitarian and Compassionate and Public Policy Considerations

- Program 2.2: Refugee Protection

- Sub-Program 2.2.1: Government-Assisted Refugees

- Sub-Program 2.2.2: Privately Sponsored Refugees

- Sub-Program 2.2.3: In-Canada Asylum

- Sub-Program 2.2.4: Pre-removal Risk Assessment

- Program 2.1: Family and Discretionary Immigration

- Strategic Outcome 3: Newcomers and citizens participate in fostering an integrated society

- Program 3.1: Newcomer Settlement and Integration

- Sub-Program 3.1.1: Foreign Credentials Referral

- Sub-Program 3.1.2: Settlement (Policy and Program Development)

- Sub-Sub-Program 3.1.2.1: Information and Orientation

- Sub-Sub-Program 3.1.2.2: Language Training

- Sub-Sub-Program 3.1.2.3: Labour Market Access

- Sub-Sub-Program 3.1.2.4: Welcoming Communities

- Sub-Sub-Program 3.1.2.5: Contribution to British Columbia for Settlement and Integration

- Sub-Sub-Program 3.1.2.6: Support for Official Language Minority Communities

- Sub-Program 3.1.3: Grant to Quebec

- Sub-Program 3.1.4: Immigration Loan

- Sub-Program 3.1.5: Refugee Resettlement Assistance Program

- Program 3.2: Citizenship for Newcomers and All Canadians

- Sub-Program 3.2.1: Citizenship Awareness

- Sub-Program 3.2.2: Citizenship Acquisition, Confirmation and Revocation

- Program 3.3: Multiculturalism for Newcomers and All Canadians

- Sub-Program 3.3.1: Multiculturalism Awareness

- Sub-Program 3.3.2: Federal and Public Institutional Multiculturalism Support

- Program 3.1: Newcomer Settlement and Integration

- Strategic Outcome 4: Managed migration that promotes Canadian interests and protects the health, safety and security of Canadians

- Program 4.1: Health Management

- Sub-Program 4.1.1: Health Screening

- Sub-Program 4.1.2: Medical Surveillance Notification

- Sub-Program 4.1.3: Interim Federal Health

- Program 4.2: Migration Control and Security Management

- Sub-Program 4.2.1: Permanent Resident Status Documents

- Sub-Program 4.2.2: Visitors Status

- Sub-Program 4.2.3: Temporary Resident Permits

- Sub-Program 4.2.4: Fraud Prevention and Program Integrity Protection

- Sub-Program 4.2.5: Global Assistance for Irregular Migrants

- Program 4.3: Canadian Influence in International Migration and Integration Agenda

- Program 4.4: Passport

- Internal Services

- Program 4.1: Health Management

Organizational Priorities

In 2013–2014, CIC identified the following four priorities.

Priority: Improving/modernizing client service

TypeFootnote 1: Ongoing

Strategic Outcomes: SO 1, 2, 3, 4—Enabling

Summary of Progress

CIC has continued the process of modernizing its client service through legislative changes and through the implementation of new technologies in program delivery. These changes allow for increased efficiency, strengthened program integrity and seamless service delivery of programs and services, as well as enabling CIC to better respond to client expectations. Key accomplishments included the following:

- The expansion of the global Visa Application Centre (VAC) network was crucial to improve access to services for applicants and to increase processing efficiencies. As of March 31, 2014, CIC had 129 VACs in 92 countries. In addition to providing valuable administrative support services in local languages to applicants before, during and after the time when their application is assessed at a CIC office, VACs also collect biometrics from some clients, thereby improving CIC’s management of identity fraud risk.

- Continuing the work of transferring business lines to the Global Case Management System (GCMS) in order to replace legacy systems. These changes improved service delivery, efficiency and security while allowing an integrated view of clients across business lines. GCMS also allowed applications created by one office to be transferred efficiently, in whole or in part, to any office in CIC’s global network for further processing. For example, London and New Delhi absorbed all Economic and Family Class production based on applicants’ country of residence for Islamabad, and Case Processing Region will process 100% of applications submitted in Canada as well as some non-complex cases submitted abroad. GCMS continued to develop and maintain system capabilities, incorporating new business and technology enhancements to improve functionality and business processes.

- A dramatic increase in the use of multiple-entry visas (MEV) for low-risk frequent visitors is ongoing. An MEV allows visitors to enter Canada several times during the validity period of their visa (up to 10 years, but not beyond the expiry date of an individual’s passport), eliminating the need for clients to reapply for visas over the course of several years. The proportion of MEVs issued has increased from 48% in September 2013 to 94% in March of 2014. The fee for MEVs was also reduced from $150 to $100. Other new initiatives, such as opening new offices in China and India, will help meet the demand in these two key countries.

- To build on program linkages and CIC’s suite of e-Tools, responsibility for the Passport Program was transferred to CIC with functions related to service delivery transferred to Service Canada. The transition was done successfully without any service disruptions to Canadians. CIC also introduced the 10-year passport option, which provides another choice for clients.

- Responsibility for International Experience Canada (IEC) was also transferred to CIC, which will align the program with Canada’s economic and labour market needs.

- Video conferencing equipment was installed in offices across Canada, enabling some clients to be interviewed via video conferencing rather than requiring them to appear in person, a particular benefit to those clients who live far from a CIC office. Video conferencing is currently being used for Pre-removal Risk Assessment, Humanitarian and Compassionate and Citizenship Hearings.

- While the Professional Association of Foreign Service Officers’ job action in 2013 affected overseas processing offices with regard to meeting overall economic admission targets and adherence to service standards and processing times, CIC’s processing network has now recovered.

Priority: Emphasizing people management

Type: Ongoing

Strategic Outcomes: SO 1, 2, 3, 4—Enabling

Summary of Progress

In its commitment to create a high-quality workforce and a workplace founded on strong leadership, CIC successfully emphasized effective people management through various measures. Most notably:

- In the transfer of responsibility for the Passport Program to CIC, senior leaders and managers were able to maintain or create the working conditions required for motivating employees to excel in an environment characterized by intense organizational changes and to help transform, through service modernization, the way CIC operates.

- CIC fully implemented the Common Human Resources Business Processes across all human resources (HR) disciplines in order to streamline and standardize HR processes and to empower managers to more effectively manage the workforce while strengthening the strategic partnerships with HR professionals.

- CIC reviewed and is now implementing national standardized core staffing services.

- An online workforce dashboard was developed to provide CIC management and staff with various graphs and data charts extracted directly from the HR management system.

- CIC worked closely with the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer at the Treasury Board Secretariat to implement the new performance management program, including the clarification of the various roles and responsibilities, to train managers and to keep the workforce informed of each step in the implementation process.

- In order to strengthen its leadership and people management capacity, CIC established mandatory Learning Roadmaps for executives, managers and supervisors.

- The organization implemented mechanisms and tools to strengthen managers’ change management abilities by establishing partnerships with the Canada School of Public Service.

- A new official languages governance structure was established to strengthen leadership accountability in implementing CIC’s official languages obligations and strategic direction.

- The development of the 2013–2016 Official Languages Plan, which addresses the challenges outlined in CIC documents: 2011 Public Service Employee Survey results, Management Accountability Framework (MAF) assessment, Departmental Staffing Accountability Report, and 2011 Official Languages Quiz.

- CIC’s Diversity and Employment Equity Champion worked closely with an Advisory Committee to establish additional strategies for the 2012–2015 Diversity and Employment Equity Plan.

- CIC determined that post-employment conflict of interest situations continue to have a low risk of occurrence and a low impact on integrity. Such disclosures will be addressed on a case-by-case basis and mitigation measures will emphasize prevention.

- Key issues and trends in HR management were presented to senior management on a quarterly basis.

- The Department continued to strengthen its capacity to plan, measure and monitor the workforce through the ongoing improvement of internal tools, HR quarterly reports, and dashboards.

- HR bulletins were published monthly to provide management and staff with important information and guidance on HR policies, initiatives and best practices to support strong people management.

- A new executive (EX) action report was implemented to better streamline EX staffing and classification actions and empower senior management to more effectively manage the workforce.

- As part of the Consolidation of Pay project, CIC prepared and transferred nearly 1,100 pay accounts for centralized processing and communicated changes to employees. Collaboration with stakeholders to clarify procedures and accountabilities was ongoing throughout.

- During the Professional Association of Foreign Service Officers’ job action in 2013, the International Region mitigated the impacts of the job action by establishing a dedicated interdisciplinary team to manage issues, strategies and communications. To manage the workload, urgent humanitarian cases and student applications were prioritized and lower-risk cases were processed by the Ottawa Case Processing Office. While leave during the job action was restricted for Foreign Service Officers as well as locally engaged staff, it was important to be able to bring back full productivity at its conclusion. To assist in the full-scale resumption of work, open communication and mutual trust between employer and employees was essential to quickly resolve problems experienced by either or both sides.

By focusing on strong leadership that embodies a high standard of values and ethics, CIC created the working conditions that inspire employees to excellence, innovation and higher levels of productivity, in turn transforming how CIC does business and provides services to clients.

Priority: Promoting management accountability and excellence

Type: Ongoing

Strategic Outcomes: SO 1, 2, 3, 4—Enabling

Summary of Progress

CIC managed its corporate services effectively by continuing to focus on strong management practices, oversight and accountability, and by strengthening compliance and monitoring, simplifying internal rules and procedures, and improving internal services. This supported CIC in achieving its mandate and priorities.

In 2013–2014, management practices and corporate infrastructure were further enhanced through the following initiatives:

- CIC supported the Government of Canada Open Data Initiative by expanding access to the CIC Access to Information and Privacy online request application to 11 additional departments. In addition, CIC piloted GCDOCS (a document management system) and prepared for full roll-out in 2014–2015.

- The Department improved internal service delivery by increasing standardization and implementing self-service options for managers. In particular, Common Human Resources Business Processes were implemented to standardize and streamline HR processes; nearly 1,100 pay accounts were sent for centralized processing as part of the Consolidation of Pay project; and procedures were established to enable implementation of the Performance Management Program.

- As demonstrated by 2013–2014 MAF results, CIC continued to improve its management practices in the areas of Values and Ethics, Audit, Evaluation, Financial, and People Management. Greater integration of risk management with planning, reporting and performance measurement was achieved to ensure that the Department is well positioned to respond to requirements for the 2014–2015 MAF exercise.

- CIC reviewed its HR policies and directives to ensure flexibility and adequate management controls.

- The Department initiated the development of a risk-based Compliance Management Framework to ensure that CIC remains compliant with all central agency policies and legislation.

- CIC enhanced the Department’s project investment management framework and continued to provide leadership in the promotion of investment planning and project management best practices within the Government of Canada community.

While managing the migration of Passport Canada into CIC and facilitating of responsibilities for service delivery to Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), corporate Passport Program enablers provided the tools needed to support a healthy and high-performing workforce which ensured that service standards for passport services were maintained at all times. Full integration with accompanying cost savings and efficiencies will be achieved over the coming years through further alignment of corporate functions.

Priority: Strengthening outcomes-based management

Type: Ongoing

Strategic Outcomes: SO 1, 2, 3, 4—Enabling

Summary of Progress

In 2013–2014, the continued implementation of the departmental Performance Measurement Action Plan strengthened overall performance measurement and outcomes-based information and data throughout CIC. Key accomplishments included:

- Improved horizontal governance of performance measurement, which ensured consistency across the Department, performance measurement data availability and performance results in support of decision making.

- Development and dissemination of performance measurement resources and tools across CIC, including a departmental guide to performance measurement.

- Further development of departmental research and performance measurement data and systems in support of outcomes-based reporting, such as the expansion of the Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment and the Refugee Claimant Continuum.

- Strengthening of departmental data governance through the development of a data governance charter to ensure a higher degree of data integrity; to harmonize operational, research, and analytical data sets; and to streamline statistical reporting.

- Implementation of revised outcomes-based performance indicators contained in the departmental Performance Measurement Framework with annual data collection, analysis and reporting.

- Development of robust Performance Measurement Strategies in numerous program areas, such as Federal Skilled Workers/Federal Skilled Trades, Settlement, Temporary Residents Biometrics Project, and Start-up Visa, creating a strong foundation for ongoing monitoring and eventual evaluation.

Risk Analysis

| Risk | Risk Response StrategyNote A | Link to Program Alignment Architecture |

|---|---|---|

Program and service delivery |

|

|

Program integrity |

|

|

Partner and stakeholder engagement |

|

|

Information management/information technology (IM/IT) capacity |

|

|

Managing change in a global context

CIC’s strategic directions, as well as its policies and operations, are influenced by a number of external factors such as emerging world events; Canadian and global economic, social and political contexts; and shifting demographic and migration trends. Furthermore, the fact that immigration is a shared area of jurisdiction between the federal government and the provinces and territories adds another layer of complexity to the effort of distributing the benefits of immigration across regions. CIC also works regularly with international and domestic partners on a range of migration issues. Information about international best practices for managing migration is acquired, and, thanks to the many international forums and meetings in which CIC participates, Canada has been able to advance its positions. Domestically, this past year CIC continued to work with the provinces and territories on the joint 2012–2015 FPT Vision Action Plan. The Plan is being overseen by FPT ministers of immigration and seeks to improve the coordination of immigrant selection and settlement within Canada.

Developing a more demand-driven economic immigration program

The Government continues to build a fast and flexible immigration system that supports Canada’s economy. The new Express Entry application management system will enable the immigration system to be more flexible and responsive to the needs of employers and Canada’s changing economic conditions and priorities by creating a pool of skilled workers ready to begin employment in Canada. Over the past year, CIC has engaged with the provinces and territories, other government departments, and employers on the design and implementation of the system in order to meet the objectives of the Government of Canada, as well as the needs of provinces, territories, and employers.

Over the past year, the Government has implemented a number of measures to ensure that the Temporary Foreign Workers (TFW) Program works in the best interest of Canadians and strengthens the Government’s ability to verify employers' compliance with the TFW Program rules; CIC works closely with ESDC to implement these reforms. These changes complement those already implemented as part of the Economic Action Plan (EAP) 2013, to support our economic recovery and growth while ensuring that more employers hire Canadians before hiring temporary foreign workers.

Reforms to the program to improve integrity and compliance in the past year include:

- Strengthened authorities conferred in the 2013 amendments to IRPA through the Budget bill which allow CIC to revoke work permits and allow ESDC to revoke, suspend and refuse to process LMOs if the public policy considerations specified in Ministerial Instructions given by the Ministers of Citizenship and Immigration and Employment and Social Development warrant such a step.

- New authorities to ESDC and CIC to impose conditions on employers, to conduct inspections for the purpose of verifying compliance with conditions, and to impose consequences for not meeting conditions after the issuance of a LMO or work permit. Employers found to be non-compliant with conditions may be added to an ineligibility list and banned from hiring TFWs for two years.

Immigration can also support the economy by creating jobs through new business ventures. On April 1, 2013, the Government launched the Start-Up Visa as a five-year pilot program to attract immigrant entrepreneurs with the potential to build innovative companies and who have the support of Canadian private sector organizations. In EAP 2014, the Government also announced its intention to terminate the existing federal Immigrant Investor and Entrepreneur Programs and their backlogs, as they offer limited economic benefit to Canada.

Providing strong service to clients is also necessary to rise to the challenge of creating a more responsive immigration system. The Department is modernizing its programs and processes, leveraging technology, and strengthening partnerships to more effectively and efficiently manage risks, workload and workforce, while keeping a strong focus on client service. Some examples of progress made in 2013–2014 include:

- Expansion of CIC’s network of Visa Application Centres which, as of March 31, 2014, stood at 129 in 92 countries;

- The Citizenship Program now has three offices dedicated to processing cases requiring additional scrutiny, and is moving toward the implementation of e-applications for citizenship; and,

- The processing of temporary resident applications continues to be transformed to increase decision makers’ efficiency and productivity.

Striving for efficient and well-managed family and humanitarian immigration

The Government remains committed to upholding Canada’s tradition of reuniting families, resettling refugees and providing protection to those in need. Since the launch of the Action Plan for Faster Family Reunification in 2011, the Government has reduced the Parents and Grandparents Program backlog by half. The Department anticipates cutting the backlog by a total of 75% by the end of 2015. CIC also met the Action Plan commitment of admitting 50,000 parents and grandparents into Canada over two years (2012 and 2013). CIC reopened the Parents and Grandparents Program for new applications on January 2, 2014. At that time, new criteria were established to ensure the fiscal sustainability of the program over the long term, further reduce the backlog, prevent future backlogs, ensure that families have the financial means to support those they sponsor, and protect the interests of taxpayers.

Major reforms to Canada’s asylum system came into force on December 15, 2012. One goal of the new system is to provide faster protection to those in need while more quickly removing those with unfounded claims. Under the new system, processing times for asylum claimants have been significantly shorter than those before the new measures took effect. It now takes, on average, just over three months for the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB) to finalize a claim, which is markedly shorter than the 20 months this process took prior to the reform.

Improving outcomes for newcomers

The ability of newcomers to make an immediate impact and contribute to the Canadian economy and society is in part determined by their access to quality settlement and integration services. To that end, CIC manages a grants and contributions program to provide financial assistance to organizations that provide services to newcomers outside of Quebec. In addition, as of April 2014 the Government of Canada has assumed the administration of settlement services in British Columbia and Manitoba, whereby federal settlement services are for the first time provided in all provinces and territories outside Quebec. In order to ensure newcomers have the tools they need to achieve success, the Government of Canada has also significantly increased settlement funding across Canada since 2005–2006, from less than $200 million to approximately $600 million in 2013–2014.

Under the Canada-Québec Accord relating to Immigration and Temporary Admission of Aliens, the Government of Canada provides a grant to Quebec for settlement services in that province. CIC has worked with Quebec officials to develop a comparative study to ensure that the settlement and integration services offered in Quebec correspond to those available in the rest of the country.

Ensuring public health and safety; and maintaining program integrity

Extensive program and policy transformation means that CIC needs to manage change efficiently and effectively in order to uphold the integrity of its programs and to continue to meet its operational objectives. CIC must ensure that its programs continue to deliver services to the right people, for the right reasons, in a consistent manner, and at the lowest possible cost, while safeguarding the immigration system against the risk of fraud, misrepresentation and other abuses.

To this end, following the passing of the Protecting Canada’s Immigration System Act, CIC began requiring biometrics from certain visitors, students and temporary workers in September 2013. This screening helps strengthen the integrity of Canada’s immigration system by protecting the safety and security of Canadians, and safeguarding against fraud and abuse, while helping to facilitate legitimate travel.

Now that Royal Assent has been given to Bill C-43, the Faster Removal of Foreign Criminals Act, the Government has taken action to close some of the loopholes that allowed individuals found inadmissible to Canada to remain in this country. Among these changes, foreign nationals inadmissible on the most serious grounds of security, human or international rights violations or organized criminality no longer have access to humanitarian and compassionate consideration.

Efforts are also underway to ensure that people and goods can efficiently move across our borders while protecting the health, safety and security of Canadians. In 2013–2014, CIC continued to work with other federal departments, such as Public Safety Canada and its portfolio organizations, to implement measures under the Canada-U.S. Beyond the Border Action Plan. The Action Plan provides a practical road map for facilitating legitimate trade and travel across the Canada-U.S. border while protecting Canadians.

On June 19, 2014, Bill C-24, the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act received Royal Assent. This law reinforces the value of Canadian citizenship and protects program integrity while creating a faster and more efficient process for citizenship applications. It also represents the most comprehensive reform of the Citizenship Act in more than a generation.

CIC must also be prepared to respond in cases of emergency, both at home and abroad. Natural disasters or unexpected world events can happen anywhere, any time, and can place a strain on CIC as it strives to protect not only Canadians and migrants affected by these events, but also employees and assets worldwide. CIC’s ability to assist those in need depends on continued strong relationships with domestic and international partners so that planned, timely and coordinated responses can be implemented in relation to unforeseen events such as war, civil unrest, cyber attacks, pandemics and natural disasters.

Remaining a well-managed organization

To ensure that CIC can effectively and efficiently deliver on its mandate and implement its ambitious change agenda, the Department continuously strives to improve its internal management practices and accountabilities by focussing on its two organizational priorities, “Emphasizing People Management” and “Promoting Management Excellence and Accountability”, described in the section above. In addition, the Department stringently monitors the finances of its programs and projects, continues to report quarterly against performance plans and targets, and expends considerable effort to achieve efficiencies and reduce backlogs.

The Department also focuses on strengthening performance-measurement capacity and the use of audits and evaluations to:

- support evidence-based policy making and program development;

- ensure that risks are well managed; and

- ensure that the intended outcomes of CIC programs are achieved in an efficient and cost-effective manner.

Given ongoing technological change, complex partnership-based IM/IT services, and an ambitious CIC modernization agenda based on the use of technology, the Department increasingly relies on IM and IT systems and infrastructure to support the delivery of CIC business lines as well as selected business lines of other organizations (such as CBSA). In 2013–2014, CIC renewed its strategic IM/IT action plan for ensuring that its IM/IT systems deliver business value efficiently and securely. The Department also enhanced its efforts to better manage information across business lines and to better manage relationships with key partners, including CBSA and Shared Services Canada.

Actual Expenditures

| 2013-14 Main Estimates |

2013-14 Planned Spending |

2013-14 Total Authorities Available for Use |

2013-14 Actual Spending (authorities used) |

Difference (actual minus planned) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,655,418,818 | 1,655,418,818 | 1,654,198,717 | 1,378,694,696 | 276,724,122 |

| 2013-14 Planned |

2013-14 Actual |

2013-14 Difference (actual minus planned) |

|---|---|---|

| 4,689 | 5,483 | 794 |

| Strategic Outcomes, Programs and Internal Services | 2013-14 Main Estimates |

2013-14 Planned Spending |

2014-15 Planned Spending |

2015-16 Planned Spending |

2013-14 Total Authorities Available for Use | 2013-14 Actual Spending (authorities used) |

2012-13 Actual Spending (authorities used) |

2011-12 Actual Spending (authorities used) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategic Outcome 1: Migration of permanent and temporary residents that strengthens Canada's economy | |||||||||

| 1.1 Permanent Economic Residents | 135,224,145 | 135,224,145 | 80,799,944 | 43,027,060 | 80,486,818 | 79,311,818 | 40,200,532 | 36,541,121 | |

| 1.2 Temporary Economic Residents | 22,315,694 | 22,315,694 | 34,918,556 | 36,687,258 | 24,764,395 | 20,831,035 | 20,617,661 | 23,659,011 | |

| Subtotal | 157,539,839 | 157,539,839 | 115,718,500 | 79,714,318 | 105,251,213 | 100,142,853 | 60,818,193 | 60,200,132 | |

| Strategic Outcome 2: Family and humanitarian migration that reunites families and offers protection to the displaced and persecuted | |||||||||

| 2.1 Family and Discretionary Immigration | 42,452,802 | 42,452,802 | 46,863,229 | 45,783,649 | 45,271,198 | 44,096,198 | 48,674,101 | 45,110,237 | |

| 2.2 Refugee Protection | 35,148,822 | 35,148,822 | 35,205,049 | 34,394,036 | 32,669,562 | 28,698,237 | 30,301,402 | 33,433,739 | |

| Subtotal | 77,601,624 | 77,601,624 | 82,068,278 | 80,177,685 | 77,940,760 | 72,794,435 | 78,975,503 | 78,543,976 | |

| Strategic Outcome 3: Newcomers and citizens participate in fostering an integrated society | |||||||||

| 3.1 Newcomer Settlement and Integration | 973,358,823 | 973,358,823 | 1,002,954,353 | 1,002,435,931 | 1,000,314,120 | 970,807,076 | 950,739,681 | 966,045,346 | |

| 3.2 Citizenship for Newcomers and All Canadians | 43,950,801 | 43,950,801 | 109,789,678 | 96,780,242 | 64,797,788 | 62,517,787 | 46,583,524 | 49,352,898 | |

| 3.3 Multiculturalism for Newcomers and All Canadians | 14,256,922 | 14,256,922 | 13,208,032 | 13,100,065 | 11,732,446 | 9,793,615 | 15,120,234 | 21,051,465 | |

| Subtotal | 1,031,566,546 | 1,031,566,546 | 1,125,952,063 | 1,112,316,238 | 1,076,844,354 | 1,043,118,478 | 1,012,443,439 | 1,036,449,709 | |

| Strategic Outcome 4: Managed migration that promotes Canada's interests and protects the health, safety, and security of Canadians | |||||||||

| 4.1 Health Management | 60,620,439 | 60,620,439 | 58,356,894 | 58,325,951 | 60,849,860 | 38,115,873 | 59,616,808 | 92,337,565 | |

| 4.2 Migration Control and Security Management | 87,096,376 | 87,096,376 | 84,966,649 | 84,402,341 | 112,701,893 | 93,642,100 | 76,410,491 | 66,771,311 | |

| 4.3 Canadian influence in international migration and integration agenda | 3,120,542 | 3,120,452 | 8,156,032 | 8,010,725 | 5,617,939 | 5,616,646 | 3,282,924 | 3,101,193 | |

| 4.4 PassportNote B | – | – | (254,192,238) | (236,497,778) | (29,101,484) | (206,332,014) | – | – | |

| Subtotal | 150,837,357 | 150,837,357 | (102,712,663) | (85,758,761) | 150,068,208 | (68,957,395) | 139,310,223 | 162,210,069 | |

| Internal Services Subtotal | 237,873,452 | 237,873,452 | 164,414,885 | 159,175,833 | 244,094,182 | 231,596,325 | 231,778,110 | 246,086,861 | |

| Total | 1,655,418,818 | 1,655,418,818 | 1,385,441,063 | 1,345,625,313 | 1,654,198,717 | 1,378,694,696 | 1,523,325,468 | 1,583,490,747 | |

The 2013–2014 planned spending of $1,655.4 million decreased by $1.2 million due to Supplementary Estimates and other funding adjustments to provide total authorities of $1,654.2 million.

Actual spending was lower than total authorities by $275.5 million. A total of $71.3 million in anticipated operating expenditures was not used. Among the most significant factors explaining this positive variance are the reduction of costs related to the reform of the Interim Federal Health Program, which led to a reduction in the volume of Interim Federal Health Program claims from 837,000 in 2012–2013 to 464,000 claims in 2013–2014, as well as the Beyond the Border Action Plan for which costs were lower than anticipated in some areas. In addition, the delivery of the Temporary Resident Biometric Project was completed on time and under budget due to strong project management practices.

Also contributing to the amount not used was funding that had been set aside to offset costs in the delay of implementing new Citizenship and Temporary Resident Program regulations.

The remaining unused amount resides mostly in general operations, where management effectively managed funds in case of unforeseen events that could have impacted the Department.

Also contributing to the Department’s overall financial position was a $177.2 million excess of revenues over expenditures in the Passport revolving fund.

Alignment of Spending with the Whole-of-Government Framework

Alignment of 2013-2014 Actual Spending with the Whole-of-Government Framework (dollars)

| Strategic Outcome | Program | Spending Area | Government of Canada Outcome | 2013-14 Actual Spending |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Migration of permanent and temporary residents that strengthens Canada’s economy | 1.1 Permanent Economic Residents | Economic Affairs | Strong Economic Growth | 79,311,818 |

| 1.2 Temporary Economic Residents | Economic Affairs | Strong Economic Growth | 20,831,035 | |

| Family and humanitarian migration that reunites families and offers protection to the displaced and persecuted | 2.1 Family and Discretionary Immigration | Social Affairs | A diverse society that promotes linguistic duality and social inclusion | 44,096,198 |

| 2.2 Refugee Protection | International Affairs | A safe and secure world through international engagement | 28,698,237 | |

| Newcomers and citizens participate in fostering an integrated society | 3.1 Newcomer Settlement and Integration | Social Affairs | A diverse society that promotes linguistic duality and social inclusion | 970,807,076 |

| 3.2 Citizenship for Newcomers and All Canadians | Social Affairs | A diverse society that promotes linguistic duality and social inclusion | 62,517,787 | |

| 3.3 Multiculturalism for Newcomers and All Canadians | Social Affairs | A diverse society that promotes linguistic duality and social inclusion | 9,793,615 | |

| Managed migration that promotes Canadian interests and protects the health, safety and security of Canadians | 4.1 Health Management | Social Affairs | Healthy Canadians | 38,115,873 |

| 4.2 Migration Control and Security Management | Social Affairs | A safe and secure Canada | 93,642,100 | |

| 4.3 Canadian Influence in International Migration and Integration Agenda | International Affairs | A safe and secure world through international engagement | 5,616,646 | |

| 4.4 Passport | International Affairs | A safe and secure world through international engagement | (206,332,014) |

Total Spending by Spending Area (dollars)

| Spending Area | Total Planned Spending | Total Actual Spending |

|---|---|---|

| Economic Affairs | 157,539,839 | 100,142,853 |

| Social Affairs | 1,221,736,153 | 1,218,972,649 |

| International Affairs | 38,269,364 | (172,017,131) |

| Government Affairs | – | – |

Departmental Spending Trend

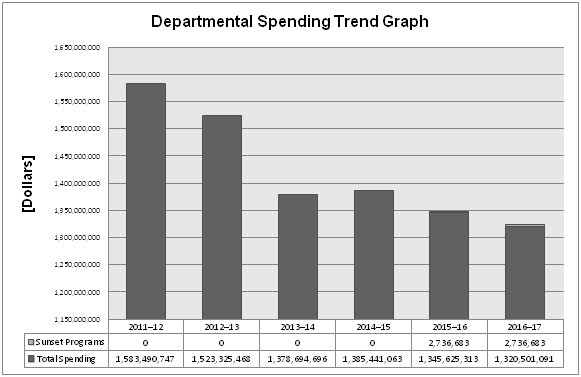

During 2013–2014, CIC’s spending to meet the objectives of its programs amounted to $1,378.7 million. The following graph illustrates CIC’s spending trend from previous years and planned spending for future years up to 2016–2017.

Text version: Departmental Spending Trend

| Fiscal Year | Total Spending | Sunset Programs |

|---|---|---|

| 2011-12 | 1,583,490,747 | 0 |

| 2012-13 | 1,523,325,468 | 0 |

| 2013-14 | 1,378,694,696 | 0 |

| 2014-15 | 1,385,441,063 | 0 |

| 2015-16 | 1,345,625,313 | 2,736,683 |

| 2016-17 | 1,320,501,091 | 2,736,683 |

CIC has achieved cost savings in the overall level of departmental spending since 2011–2012 as it has contributed to the Government’s objective of reaching a balanced budget by 2015–2016.

Estimates by Vote

For information on CIC’s organizational votes and statutory expenditures, consult the Public Accounts of Canada 2014 on the Public Works and Government Services Canada website.

Section II: Analysis of Programs by Strategic Outcome

Strategic Outcome 1: Migration of permanent and temporary residents that strengthens Canada’s economy

CIC plays a significant role in fostering Canada’s economic development. By promoting Canada as a destination of choice for innovation, investment and opportunity, CIC encourages talented individuals to come to Canada and to contribute to our prosperity. Canada’s immigration program is based on non-discriminatory principles—foreign nationals are assessed without regard to race, nationality, ethnic origin, colour, religion or gender. Those who are selected to immigrate to Canada have the skills, education, language competencies and work experience to make an immediate economic contribution.

CIC’s efforts, whether through policy and program development or processing applications for the Federal Skilled Worker Program, the Quebec Skilled Workers Program, the Provincial Nominees Program or other programs, attract thousands of qualified permanent residents each year. Under the 2008 amendments to Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) the Minister for Citizenship and Immigration Canada has the authority to issue instructions establishing priorities for processing certain categories of applications. In that regard, the Department analyses and monitors its programs to ensure they are responsive to emerging labour market needs.

CIC also facilitates the hiring of foreign nationals by Canadian employers on a temporary basis and implements a number of initiatives to attract and retain international students.

| Performance Indicator | Target | 2013-14 Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Rank within the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) of employment rate for all immigrants | ≤ 5 | 6 |

Benefits for Canadians

Immigration continues to have a significant influence on Canadian society and economic development. Permanent residents who arrive in Canada every year enhance Canada’s social fabric, contribute to labour market growth and strengthen the economy. Changes that modernize and improve the immigration system not only strengthen the integrity of the Permanent Economic Residents program but also benefit Canada by targeting skills Canadian employers need and admitting qualified individuals more quickly.

Temporary foreign workers help generate growth for a number of Canadian industries by meeting short-term and acute needs in the labour market that are not easily filled by the domestic labour force. International students contribute economically as consumers and enrich the fabric of Canadian society through their diverse experiences and talents. Some temporary workers and international students represent a key talent pool to be retained as immigrants.

Performance Analysis

Canada's average employment rate of the foreign-born rose to 70.1% in 2012, which is an increase from 2011 levels and the highest average employment rate since 2008. Canada rose from seventh to sixth place among OECD countries, which can be attributed to improvements in the economy in 2013–2014 compared to 2012–2013.

Canada’s Immigration Plan for 2013

The immigration levels set out in Canada’s immigration plan for 2013 reflect the important role of immigration in supporting Canada’s economic growth and prosperity. Further details can be found in the Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration, 2013.

| Immigrant Category | 2013 Plan Admissions Ranges | Number Admitted | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| Federal Skilled Workers | 53,500 | 55,300 | 52,877 |

| Federal Business | 5,500 | 6,000 | 5,098 |

| Canadian Experience Class | 9,600 | 10,000 | 7,216 |

| Live-in Caregivers | 8,000 | 9,300 | 8,797 |

| Provincial Nominee Program | 42,000 | 45,000 | 39,915 |

| Quebec-selected Skilled Workers | 31,000 | 34,000 | 30,284 |

| Quebec-selected Business | 2,500 | 2,700 | 3,994 |

| Total Economic | 152,100 | 162,300 | 148,181 |

| Spouses, Partners and Children (including Family Relations H&C) | 42,000 | 48,500 | 49,513 |

| Parents and Grandparents | 21,800 | 25,000 | 32,318 |

| Total Family | 63,800 | 73,500 | 81,831 |

| Protected Persons in Canada | 7,000 | 8,500 | 8,149 |

| Dependants Abroad of Protected Persons in Canada | 4,000 | 4,500 | 3,714 |

| Government-assisted Refugees | 6,800 | 7,100 | 5,756 |

| Visa Office Referred Refugees | 200 | 300 | 153 |

| Public Policy–Federal Resettlement Assistance | 500 | 600 | 29 |

| Privately Sponsored Refugees | 4,500 | 6,500 | 6,277 |

| Public Policy–Other Resettlement Assistance | 100 | 400 | -- |

| Humanitarian and Compassionate Considerations | 900 | 1,100 | 2,875 |

| Other H&C cases outside the family class/Public Policy | – | – | 1,934 |

| Total Humanitarian | 24,000 | 29,000 | 28,887

|

| Permit Holders | 100 | 200 | 44 |

| DROC and PDRCC | – | – | 10 |

| Grand Total | 240,000 | 265,000 | 258,953 |

Program 1.1: Permanent Economic Residents

Rooted in objectives outlined in IRPA, the focus of this Program is on the selection and processing of immigrants who can support the development of a strong and prosperous Canada, in which the benefits of immigration are shared across all regions of Canada. The acceptance of qualified permanent residents helps the government meet its economic objectives, such as building a skilled workforce, addressing immediate and longer term labour market needs, and supporting national and regional labour force growth. The selection and processing involve the issuance of a permanent resident visa to qualified applicants, as well as the refusal of unqualified applicants.

| Total Budgetary Expenditures (Main Estimates) 2013-14 |

Planned Spending 2013-14 |

Total Authorities (available for use) 2013-14 |

Actual Spending (authorities used) 2013-14 |

Difference 2013-14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 135,224,145 | 135,224,145 | 80,486,818 | 79,311,818 | (55,912,327) |

Actual spending was lower than planned spending by $55.9 million due to lower-than-forecasted fees returned for terminated applications.

| Planned 2013-14 |

Actual 2013-14 |

Difference 2013-14 |

|---|---|---|

| 295 | 384 | 89 |

| Expected Result | Performance Indicators | Targets | Actual Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| The benefits of immigration are shared across all regions of Canada | Percentage of new permanent residents who land outside of the Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver Census Metropolitan Areas (CMAs) | > 50% | 42.1% |

| Economic immigrants contribute to the growth of the Canadian labour force | Incidence of Employment 3-5 years after landing relative to the Canadian average | + 10% | + 12% |

| Employment earnings 3-5 years after landing relative to the Canadian average | 100% | 78% | |

| Rate of social assistance 5 years after landing | ≤ 5% | 3.9% | |

| Percentage growth in labour force attributed to economic migration | > 42% | 62% | |

| Successful permanent resident applicants are admitted in Canada | Number of admissions | 152,100 – 162,300 | 148,181 |

Performance Analysis and Lessons Learned

As shown in the first indicator, the percentage of new permanent residents who landed outside of the census metropolitan areas (CMAs) was 42.1%, a percentage that has ranged between 40% and 42% over the last three years. There has been a marked de-concentration of immigrant regional distribution during the past 10 to 15 years, namely a decrease in the proportion of permanent residents intending to reside in Ontario and an increase in those intending to reside in the Prairie Provinces.

For the second and third performance indicators, approximately 78% of permanent economic principal applicants show employment earnings three to five years after landing, which is 12% higher than the Canadian average of 66%. Economic permanent resident principal applicants are selected for their labour-market suitability and thus their ability to become economically established in Canada. The average entry employment earnings for permanent economic principal applicants are well above the average of all immigrants and, in addition, are on par with or surpass the overall Canadian average three years after landing. Permanent economic principal applicants have higher than average employment earnings relative to other immigrants and greater labour market attachment as measured by the incidence of employment earnings one year after landing. As demonstrated by the fourth indicator, these applicants also utilize social assistance at a rate lower than the Canadian average.

For the fifth indicator, 62% of labour force growth was attributed to economic immigration—a 1% increase from 2012 (63%). Immigration is increasingly accounting for most labour force growth and, therefore, increasingly contributes to positive economic consequences of a growing labour force, such as increased economic activity and greater tax revenue. The proportion of labour force growth due to immigration is expected to continue to increase as Canada’s population ages. However, Canadians continue to comprise the vast majority of new labour market entrants.

For the last indicator, 148,181 permanent residents were admitted to Canada in 2013 in economic class programs. CIC issued 149,500 visas (for overseas applicants) and authorizations (for applicants already in Canada) for permanent residence in this category in 2013.

CIC consulted provinces and territories on immigration levels planning; federal, provincial and territorial (FPT) ministers supported moving further toward a 70/30 economic-to-non-economic immigration split and committed to developing an action plan to achieve this goal.

CIC advanced the development of a new immigrant selection model. The Department led policy work to support the finalization of the design of Express Entry (EE) for initial launch, which were discussed with FPT Ministers in March 2014. In an effort to engage employers in design, CIC struck the Employer Technical Reference Group, and organized information sessions and roundtables across Canada. The Department also advanced work on mandatory Job Bank registration and engaged Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) to present the modernized Job Bank at the roundtables. IT business requirements were finalized and an implementation plan was developed.

To promote integrity in the immigration system, CIC launched a new campaign in partnership with the Immigration Consultants of Canada Regulatory Council (ICCRC) and the Federation of Law Societies of Canada that promotes awareness of the dangers of using an unauthorized immigration representative. Designated by the Government in 2011, the ICCRC’s mandate is to protect the consumers of immigration consulting services and ensure professional conduct among its members, known as Regulated Canadian Immigration Consultants.

Sub-Program 1.1.1: Federal Skilled Workers

The Federal Skilled Workers (FSW) Program is the Government of Canada's main selection system for skilled immigration, accounting for roughly 20% of all new permanent residents annually. The Program uses a “points system” to identify prospective immigrants with the ability to economically establish in Canada, based on their human capital (education, skilled work experience, language skills, etc.). The goal of the Program is to select immigrants who will make a long-term contribution to Canada's national and structural labour market needs, in support of a strong and prosperous Canadian economy. The selection and processing involve the issuance of a permanent resident visa to qualified applicants, as well as the refusal of unqualified applicants.

| Planned Spending 2013-14Note D |

Actual Spending 2013-14 |

Difference 2013-14 |

|---|---|---|

| – | 58,008,325 | – |

| Planned 2013-14 |

Actual 2013-14 |

Difference 2013-14 |

|---|---|---|

| – | 178 | – |

| Expected Results | Performance Indicators | Targets | Actual Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Federally selected skilled workers contribute to the growth of the Canadian labour force | FSW incidence of employment 3-5 years after landing relative to the Canadian average | + 15% | + 12% |

| Percentage of federally-selected skilled workers earning at or above the Canadian average 3-5 years after landing | ≥ 35% | 49% | |

| Rate of social assistance for FSW principal applicants, 5 years after landing | ≤ 2% | 3.7% | |

| Successful Federal Skilled Worker applicants are admitted to Canada | Number of admissions | 53,500 – 55,300 | 52,877 |

Performance Analysis and Lessons Learned

For the first indicator above, approximately 78% of federally selected skilled workers show employment earnings three to five years after landing, which is 12% higher than the Canadian average of approximately 66%.

For the second indicator, approximately 49% of federally selected skilled workers show employment earnings at or above the Canadian average five years after landing, significantly surpassing the target.

For the third indicator, the social assistance rate five years after landing was 3.7% for the 2011 tax year, the last year for which data is available. It is not surprising to see a low incidence of social assistance for FSWs, given their high employment earnings and the fact that they were selected for their labour market suitability.

For the last indicator, there were 52,877 FSW Program admissions in 2013.

Effective May 4, 2013, the eighth set of Ministerial Instructions (MI8) lifted the general pause on the FSW Program, and re-established an eligible occupations stream, with an overall cap of 5,000 new applications and subcaps of 300 applications in each of the 24 eligible occupations. MI8 coincided with the coming into force of the modernized FSW Program, which included new minimum language requirements and mandatory educational credential assessments of foreign educational credentials. MI8 also reset the cap for Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) applicants under the program (1,000 new applications each year) and for the Federal Skilled Trades Program (3,000 new applications each year) for the period of May 4, 2013 to April 30, 2014.

Sub-Program 1.1.2: Quebec Skilled Workers

The Canada-Quebec Accord specifies that the province of Quebec is solely responsible for the selection of applicants destined to the province of Quebec. Federal responsibility under the Accord is to assess an applicant’s admissibility and to issue permanent resident visas. The Quebec Skilled Workers (QSW) Program uses specific criteria to identify immigrants with the human capital and skills needed to economically establish in Quebec. Similar to the Federal Skilled Worker Program, applicants to the QSW are assessed according to their age, education, work experience, language proficiency (in French), and enhanced settlement prospects (previous education or work experience in Canada, or a confirmed job offer). The selection and processing involve the issuance of a permanent resident visa to qualified applicants, as well as the refusal of unqualified applicants.

| Planned Spending 2013-14 |

Actual Spending 2013-14 |

Difference 2013-14 |

|---|---|---|

| – | 4,671,873 | – |

| Planned 2013-14 |

Actual 2013-14 |

Difference 2013-14 |

|---|---|---|

| – | 53 | – |

| Expected Result | Performance Indicator | Target | Actual Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Successful QSW applicants are admitted to Canada | Number of admissions destined to Quebec | 31,000–34,000 | 30,197 |

| Successful QSW applicants are admitted to Quebec | Number of admissions for Quebec | 31,000–34,000 | 30,284 |

Performance Analysis and Lessons Learned

The difference in the number of individuals who are destined to Quebec versus admissions to Quebec (a difference of 87 cases) can be attributed to individuals who are accepted to Canada under Quebec immigration programs but who decide to move elsewhere in Canada upon landing. For 2013, the Government of Quebec planned for 31,400–32,700 admissions for Quebec-selected skilled workers. CIC’s levels plan range, as indicated in the performance results above, does not match Quebec’s planned admissions because Quebec published its 2013 Levels Plan after CIC. Quebec ranges are always accommodated within CIC’s existing total planning range, and in 2013, CIC fell short of Quebec’s targeted planning range by 1,116 admissions.

Sub-Program 1.1.3: Provincial Nominees

The Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) supports the Government of Canada’s objective for the benefits of immigration to be shared across all regions of Canada. Bilateral immigration agreements are in place with all provinces and territories except Nunavut and QuebecFootnote 2, conferring on their governments the authority to identify and nominate for permanent residence immigrants who will meet local economic development and regional labour market needs, and who wish to settle in that specific province or territory. As part of the nomination process, provincial and territorial governments assess the skills, education and work experience of prospective candidates to ensure that nominees can make an immediate economic contribution to the nominating province or territory. CIC retains the final selection authority and verifies that nominees can economically establish in Canada and meet all admissibility requirements before issuing permanent resident visas. The selection and processing involve the issuance of a permanent resident visa to qualified applicants, as well as the refusal of unqualified applicants.

| Planned Spending 2013-14 |

Actual Spending 2013-14 |

Difference 2013-14 |

|---|---|---|

| – | 4,159,670 | – |

| Planned 2013-14 |

Actual 2013-14 |

Difference 2013-14 |

|---|---|---|

| – | 36 | – |

| Expected Results | Performance Indicators | Targets | Actual Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provincially nominated workers contribute to the growth of the Canadian labour force | PNP incidence of employment 3-5 years after landing relative to the Canadian average | ≥ +15% | +16% |

| Percentage of provincially-nominated workers earning at or above the Canadian average 3-5 years after landing | ≥ 25% | 46% |

|

| Rate of social assistance for PNP principal applicants, 5 years after landing | ≤ 2% | 1.1% |

|

| Provincially-nominated workers contribute to the growth of the labour force of the province/territory of nomination | PNP incidence of employment, in their PT of nomination, 3-5 years after landing relative to that province or territory's incidence of employment earnings | ≥ +10% | +16% |

| Successful Provincial Nominee applicants are admitted to Canada | Number of admissions | 42,000 – 45,000 | 39,915 |

| Provincial Nominees contribute to the shared benefits of immigration in regions of Canada | Percentage of provincially-nominated immigrants landing outside of Toronto and Vancouver Census Metropolitan Areas (CMAs) (excludes Quebec and QSW) | ≥ 90% | 83.3% |

Performance Analysis and Lessons Learned

For the first indicator, the incidence of employment for provincial nominees is approximately 82% three to five years after landing, which is 16% greater than the Canadian average of 66%. For the second indicator, approximately 46% of provincial nominees show employment earnings at or above the Canadian average five years after landing, well above the target of 25%. The third indicator demonstrates that rates of social assistance are quite low for this group.

For the fourth indicator, provincial nominees show incidence of employment, in all provinces, approximately 16% on average higher than that of Canadians. This result is not surprising given that the PNP is intended to address regional labour market shortages and that a significant proportion of provincial nominees have a job offer at the time of nomination.

The fifth indicator shows that the number of provincial nominees admitted to Canada remained relatively stable in 2013, at 39,915 admissions.

For the last indicator, 83.3% of provincial nominees were destined outside the CMAs of Toronto and Vancouver. (Immigrants selected under the QSW Program are excluded from these results.) The high proportion of provincial nominees settling outside these two cities demonstrates the program’s contribution to a more regionally balanced migration. The PNP is one of the main drivers in the marked deconcentration of immigrant regional distribution during the past decade.

Sub-Program 1.1.4: Live-in Caregivers

The Live-in Caregiver Program (LCP) allows persons residing in Canada to employ qualified foreign workers in private residences to provide care for children, elderly persons or persons with a disability. Eligible applicants come to Canada as temporary foreign workers, subject to their employer obtaining a neutral or positive Labour Market Opinion (LMO) from Human Resources and Skills Development Canada. The LMO considers whether a Canadian or permanent resident is available and the wage and working conditions being offered. The critical component of the program distinguishing it from the general pool of Temporary Foreign Workers is the requirement for the caregiver to reside in their place of employment. The program is also unique in that foreign workers arriving in Canada under the program are eligible to apply for permanent residence after two years or 3,900 hours of fulltime employment within four years of their arrival in Canada. They are granted permanent residence as part of the Live-in Caregiver category of the Economic Class, with established room under the Annual Levels Plan. The selection and processing involve the issuance of a permanent resident visa to qualified applicants, as well as the refusal of unqualified applicants.

| Planned Spending 2013-14 |

Actual Spending 2013-14 |

Difference 2013-14 |

|---|---|---|

| – | 4,442,856 | – |

| Planned 2013-14 |

Actual 2013-14 |

Difference 2013-14 |

|---|---|---|

| – | 70 | – |

| Expected Result | Performance Indicator | Target | Actual Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Successful LCP permanent resident applicants are admitted to Canada | Number of admissions | 8,000–9,300 | 8,797 |

Performance Analysis and Lessons Learned

In 2013, there were 8,797 live-in caregiver admissions, which was within the target range. This result reflected operational planning and resource allocation to support the Department’s goal of reducing the backlog of LCP applications.

Sub-Program 1.1.5: Canadian Experience Class