ARCHIVED – Syrian Outcomes Report

Evaluation Division

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

June 2019

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship, 2019

Cat. no. Ci4-195/2019E-PDF

ISBN 978-0-660-31530-0

IRCC-2839-07-2019

Ref. No.: E1-2019

Download:

Table of contents

- List of acronyms

- Executive summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Context of the Syrian Refugee Initiative

- 3. Outcomes by thematic areas

- 4. Conclusion and moving forward

- 5. Sources

- 5.1 Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment (ICARE)

- 5.2 2018 IRCC Settlement Outcomes Survey

- 5.3 2016 Longitudinal Immigration Database and 2017 T4 earnings

- 5.4 IRCC-SSHRC funded research

- 5.5 Non-governmental research and studies

- 5.6 Statistics Canada – General Social Survey 2013 and Census 2016

- 5.7 Federal government and parliamentary studies

- Annex A: Socio-demographic profile of Syrians

- Annex B: Profile of IRCC-Funded Settlement Services usage (iCARE) – Syrian profile

- Annex C: IRCC Settlement Outcomes Survey – Syrian respondent profile

- Annex D: List of IRCC-SSHRC funded research on Syrians

- Annex E: Bibliography

List of acronyms

- BVOR

- Blended Visa Office Referred Refugee

- GAR

- Government Assisted Refugee

- GSS

- General Social Survey

- iCARE

- Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment

- IFH

- Interim Federal Health Program

- IMDB

- Longitudinal Immigration Database

- IRCC

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- LINC

- Language Instruction for Newcomers to Canada

- LIP

- Local Immigration Partnership

- PSR

- Privately Sponsored Refugee

- RAP

- Resettlement Assistance Program

- SPO

- Service Provider Organization

- SWIS

- Settlement Workers in School

- UNHCR

- United Nations Refugee Agency

Executive summary

The Syrian Outcomes Report provides a thematic overview of the outcomes of the Syrian refugees who were resettled in Canada between November 2015 and December 2016. This report provides a comprehensive overview of integration outcomes to date for this group of newcomers.

Information and data have been compiled from various sources including Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) settlement service data system (iCARE), a 2018 Departmental Settlement Outcomes Survey, Statistics Canada data and research by academics and settlement service providers.

These data sources tell a story about the settlement of this population, with overall results showing that Syrian integration outcomes have been steadily improving since their arrival in Canada. Syrians are getting the help they need. They feel welcome in their communities. Their employment prospects are getting better. And as they spend more time here, they’re enhancing their language skills and settling in their new home. Key highlights include:

- Syrians are integrating into their communities by making friends, volunteering and building ties which have contributed to a strong sense of belonging. Overwhelmingly, Syrians felt their community was welcoming to newcomers.

- Syrians accessed federally-funded settlement and support services at a higher rate compared to other resettled refugees who arrived in Canada during the same period.

- A large portion of Syrians have accessed federally-funded language services. Most Syrian survey respondents reported being able to complete day-to-day tasks (such as going shopping, visit doctors) in English without help while a lower ability was reported for completing tasks in French.

- While Syrians had lower initial incidence of employment compared to other resettled refugees, they appear to be catching up, and on a similar trajectory as other resettled populations. Average employment earnings have also increased for Syrians with more time in Canada.

- Syrian survey respondents reported having enough information to conduct their day-to-day lives. However, food security continues to be a concern.

- A lack of language skills, understanding of health services, and the stigma around mental health were identified as the main factors preventing some Syrians from accessing healthcare. But despite these barriers, most surveyed Syrians reported having a doctor or healthcare provider.

- While a large majority of Syrian children are reported as enrolled in school, some Syrian students are still facing social and linguistic barriers.

While a majority of integration outcomes are positive or showing positive trends (e.g., sense of belonging, increasing labour market participation, language usage and accessing settlement services), some challenges remain. But it is important to remember that many of these challenges are common difficulties for all resettled refugees and recent newcomers, and are not unique to the Syrian experience. Overall, the integration outcomes of Syrians are in line with those of other resettled refugee populations that have arrived in Canada.

As Syrians are at a relatively early stage of their integration journey, their settlement story will continue to evolve.

1. Introduction

The Syrian Outcomes Report provides a thematic overview of the outcomes of the Syrian population who were resettled in Canada between November 2015 and December 2016. With the Government of Canada’s unprecedented commitments to resettle Syrian refugees and the high degree of public interest in the Initiative, this report provides a results overview on this population.

While the results described in this report showcase the relatively immediate stages in the integration journey of the Syrians who were resettled under the Syrian Refugee Initiative, it is important to note that every refugee’s journey is unique in terms of the opportunities and challenges faced as they work to make Canada their home.

2. Context of the Syrian Refugee Initiative

2.1 Background on Operation Syrian Refugees and commitments

In response to the humanitarian crisis in Syria which has displaced millions of Syrians, the Government of Canada began Operation Syrian Refugees in November 2015 and committed to welcoming 25,000 Syrian refugees by the end of February 2016. This commitment was later expanded to include 25,000 Syrian Government Assisted Refugees (GAR) and Blended Visa Office Referred Refugees (BVOR) in 2016, as well as additional Privately Sponsored Refugees (PSR)Footnote 1.

This massive resettlement effort required ongoing collaboration between all resettlement players. With the task of getting the Syrian refugees to Canada, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) and other federal government departments worked with international partners to identify the Syrians for resettlement, process their applications, get them to Canada, and then to their new community.

Once Syrian refugees arrived in Canada, efforts were required for the Government of Canada to work closely with in-Canada stakeholders, namely provinces and territories, Service Provider Organizations (SPO) across Canada, private sponsors, and community organizations to ensure that the settlement and integration process for Syrian refugees was as facilitative and supportive as possible.

While government resettlement programs and supports were already in existence, the Syrian Refugee Initiative was an exceptional circumstance. Prior to the Syrian Refugee Initiative, approximately 12,000 refugees were resettled in Canada every year. The Syrian commitment went above and beyond Canada’s typical resettlement commitments. Due to the widespread participation of Canadians and communities in welcoming this population, there has been interest in subsequent reporting on the outcomes of the resettlement and integration efforts.

2.2 Resettlement and settlement programs

Syrians were processed and admitted to Canada via one of the following existing Resettlement ProgramsFootnote 2.

Government Assisted Refugees (GAR)

GARs were referred to Canada by the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) or the Turkish Government. The GAR Program has historically placed an emphasis on selecting refugees based on their need for protection, meaning GARs often have higher needs than other refugee groups.

Privately Sponsored Refugees (PSR)

PSRs were identified and sponsored by permanent residents or Canadian citizens.

Blended Visa Office-Referred Refugees (BVOR)

BVOR refugees were referred by UNHCR and identified by Canadian visa officers for participation in the BVOR Program based on specific criteria. The refugees’ profiles were posted to a designated BVOR website where potential sponsors could select a refugee case to support.

After arrival in Canada, supports were available to help meet the immediate and essential needs of resettled refugees. For GARs, this was provided through the Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP) by designated SPOs, while for PSRs and BVORs, it was provided by private sponsors. In addition, GARs and BVOR refugees received monthly income support (based on provincial social assistance rates) meant to support immediate and essential needs, including shelter, food, and incidentals. Private sponsors provided either financial support or in-kindFootnote 3. BVOR is a blend of both the GAR Program (receiving income support through RAP) and the PSR Program (private sponsors selecting cases), resulting in BVORs having similar economic outcomes to both the GAR and PSR Program.

The Settlement Program aims to support newcomers’ successful settlement and integration. These federally-funded services are available to all newcomers up until they become citizens. Through the Settlement Program, IRCC funds SPOs to deliver language learning, community and employment services, path-finding and referral servicesFootnote 4. Refugees, along with immigrants, can also access provincial and local settlement services.

The Interim Federal Health Program (IFH) provides limited, temporary health care benefits to resettled refugees who are not eligible for provincial or territorial health insurance.Footnote 5

The expedited nature of Operation Syrian Refugees resulted in several differences in the resettlement process for the Syrians compared to other resettled populations, which may have affected initial settlement:

- Application processing: The initial phases of the initiative moved very quickly for Syrians – many had just a few days between being offered protection, their application decision, and arriving in Canada. This did not allow for much time to process the drastic life change.

- Pre-arrival settlement services: While pre-arrival services are typically offered to resettled refugees, the first wave of Syrians did not receive these services, contributing to a lack of basic integration information, which may have made the initial resettlement stages more difficult.

- Immigration loans: Syrians did not have an immigration loan to cover the cost of their admissibility exams or transportation. As such, the loan repayment burden was not present for Syrians.

2.3 Socio-demographic profile of Syrians

A total of 39,636 Syrian refugees arrived in Canada between November 4, 2015 and December 31, 2016Footnote 6. Of those, 50% were over the age of 18 upon arrival in Canada, and 51% were male. Over half of the Syrians were GARs (55%), 35% were PSR, and 10% were BVOR refugeesFootnote 7.

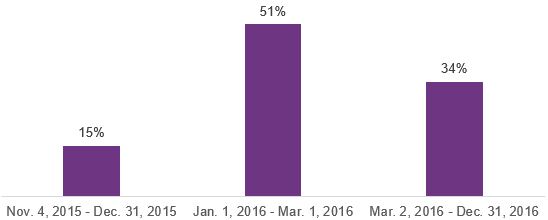

Chart 1: Arrival date

Text version: Arrival date

| Arrival date | % |

|---|---|

| November 4, 2015 - December 31, 2015 | 15% |

| January 1, 2016 - March 1, 2016 | 51% |

| March 2, 2016 - December 31, 2016 | 34% |

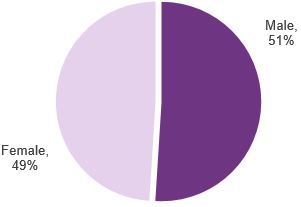

Chart 2: Gender

Text version: Gender

| Gender | % |

|---|---|

| Male | 51% |

| Female | 49% |

Chart 3: Immigration category

Text version: Immigration category

| Immigration category | % |

|---|---|

| GAR | 55% |

| PSR | 35% |

| BVOR | 10% |

As noted through administrative data, census data, as well as previous studies, the Syrian population differs from the typical resettlement population. Primarily, data has shown that Syrian PSRs have very different characteristics than their GAR and BVOR counterparts.

- Adults: While 66% of PSRs were adults, GARs and BVORs had a high proportion of minors (59% and 57%, respectively).

- Family size: Almost half (49%) of PSRs came to Canada not part of a family unit, compared to GARs and BVORs who were more likely to come to Canada as part of a family unit of 4 to 6 family members (52% and 58%, respectively). Also, GARs and BVORs had larger families, with 19% of GAR families, and 11% of BVOR families being comprised of families with 7 or more family members.

- Province of destination: A high proportion of PSRs were destined to Quebec (34%) compared to GAR and BVOR (9% and 1%, respectively).

- Knowledge of English or French: Half of Syrian PSRs self-identified as having knowledge of English, French or both. Comparatively, 92% GARs self-reported having no knowledge of either language.

- Working age: 59% of PSRs were working age (between 18 and 59) at the time of arrival in Canada. Comparatively, only 40% of GARs were working age at the time of arrival in Canada.

2.4 Socio-demographic comparison to non-Syrian populations

The profile of Syrian refugees was different than that other refugees who were resettled during the same period (November 4, 2015 to December 31, 2016); the key differences in socio-demographic characteristics at time of arrival are highlighted below.

Overall, the main differences between the populations are regarding immigration category, self-reported knowledge of official languages, and age at time of arrival in Canada.

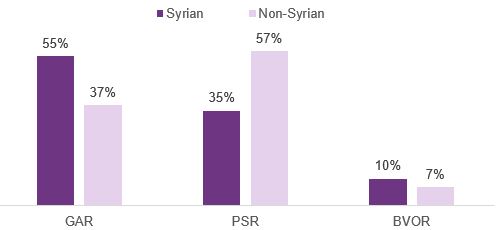

Chart 4: Immigration category

Text version: Immigration category

| Immigration category | Syrian | Non-Syrian |

|---|---|---|

| GAR | 55% | 37% |

| PSR | 35% | 57% |

| BVOR | 10% | 7% |

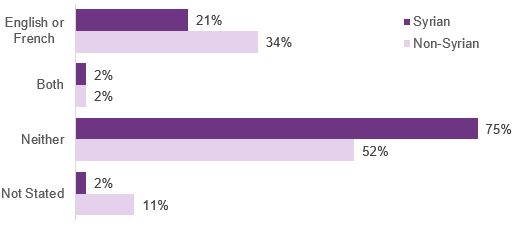

Chart 5: Self-declared knowledge of official languages

Text version: Self-declared knowledge of official languages

| Official languages | Non-Syrian (%) | Syrian (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Not stated | 11% | 2% |

| Neither | 52% | 75% |

| Both | 2% | 2% |

| English or French | 34% | 21% |

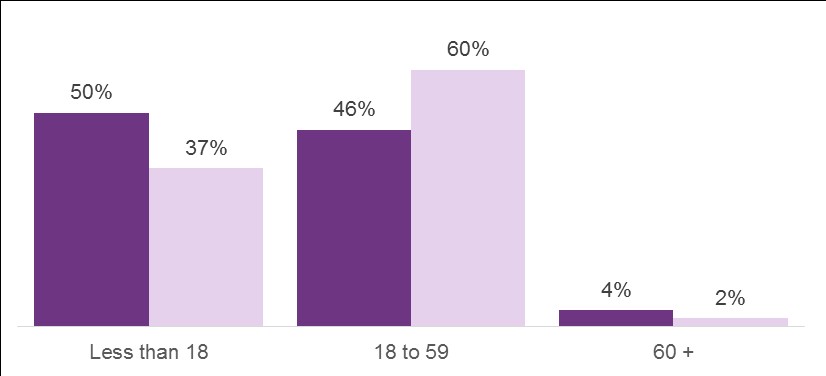

Chart 6: Age at time of arrival

Text version: Age at time of arrival

| Immigration category | Syrian (%) | Non-Syrian (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 18 | 50% | 37% |

| 18 to 59 | 46% | 60% |

| 60 + | 4% | 2% |

- Immigration category: Over half (55%) of Syrian refugees were GARs, while 35% were PSRs and 10% were BVOR. This differs to non-Syrian refugees, in which 37% were GARs, 57% were PSRs, and 7% BVOR.

- Self-reported knowledge of official languages: 65% of Syrian refugees over the age of 18 self-reported no knowledge of English or French, compared to 42% of non-Syrian refugees.

- Age at time of arrival in Canada: Fewer Syrian refugees were working age, as 47% were between the ages of 18 and 60 at time of arrival in Canada, compared to 61% of non-Syrian refugees.

- Family status: 30% of Syrian refugees were principal applicants, compared to 44% of non-Syrian refugees. This can be attributed to the larger families of Syrian refugees.

- Minors: Half of the Syrian population (50%) were under the age of 18 at the time of arrival, in comparison to 37% of non-Syrian refugees.

- Education: No differences were noted in education between the two populations, with 80% of Syrians and 75% of non-Syrian refugees reporting no education or less than secondary.

3. Outcomes by thematic areas

Outcomes are being presented by thematic integration areas to best consolidate evidence from a variety of sources to tell the Syrians’ results story by key aspects of settlement. Comparisons are made to other resettled populations, where possible.

Some settlement outcomes for Syrians include language, employment, daily life, health, and education. These outcomes are not unique to the Syrian population, as they are relevant to all resettled refugee populations as they navigate through the integration process. Also, it should be noted that resettled refugees are not selected based on their capacity to establish economically, and as such, their economic integration outcomes will differ among resettled populations due to the contexts of their arrival in Canada, as well as among other immigrant populations.

While Syrians were admitted to Canada through the resettled refugee stream, upon arrival they became permanent residents. Thus, three years into their integration, this report will refer to them in their integration journey as Syrians, unless the refugee categories (i.e., GAR, PSR, BVOR) are required for comparison purposesFootnote 8.

The overall goal of this report is to demonstrate a comprehensive picture of Syrian outcomes. Information has been synthesized from a variety of sources, including departmental surveys, federal administrative data (i.e., socio-demographic information), federal settlement service data (Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment (iCARE)), Statistics Canada data (i.e., tax records via the Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB), and Census), non-governmental research (i.e., academics, services providers), and federal government studies. A full list of data sources can be found in Section 5, and documents used in Annex E.

A wide variety of research has been undertaken on the Syrian population; however, in many cases it is not representative of the entire Syrian population. For example, most of the non-governmental research projects focused on a particular city or sub-group of the population (e.g., youth, private sponsors, etc.).

In addition, some results (i.e., economic outcomes) should be considered as early outcomes. As integration is a lengthy, multigenerational process, the Department will continue to monitor long-term integration results of resettled refugees.

3.1 Federally-funded settlement service usage

Summary: Syrians accessed federally-funded settlement and support services at a higher rate than other resettled refugees who arrived in Canada during the same period.

Federally-funded settlement services are provided to newcomers to assist in their integration in Canada.

Federally-funded settlement services

A large majority of Syrian GARs and BVORs accessed settlement servicesFootnote 9, with almost 100% receiving at least one settlement service, compared to 93% of PSRs.

Overall, Syrians accessed settlement services at a higher rate than non-Syrians who arrived in Canada during the same period.

| Accessing settlement services | Syrians (%) | Non-Syrians (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Needs assessment and referral services | 91% | 87% |

| Information and orientation | 94% | 95% |

| Community connections | 60% | 33% |

| Employment related services | 30% | 30% |

| Language assessment | 89% | 85% |

| Language training | 77% | 63% |

Source: IRCC, iCARE, December 31, 2018

Research reported that Syrians had positive experiences with the settlement services received. However, language was identified as a barrier for accessing services, with many often needing an interpreterFootnote 10.

Cultural brokers were identified as being important for social connections – connecting refugees with services, helping with the navigation of provincial/federal systems, and connecting Syrians to other community networksFootnote 11.

Federally-funded support services

Of the Syrians who received IRCC-funded settlement services, 87% accessed support services (e.g., child care, translation, interpretation, etc.). This is a higher proportion compared to non-Syrian refugees who arrived in Canada during the same period, in which 70% of those who accessed settlement services received support services.

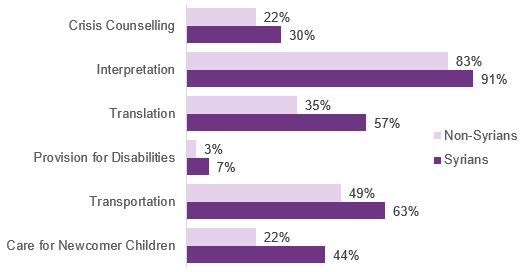

Chart 7: Accessing support services

Text version: Accessing support services

| Accessing support services | Syrian (%) | Non-Syrian (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Care for newcomer children | 44% | 22% |

| Transportation | 63% | 49% |

| Provision for disabilities | 7% | 3% |

| Translation | 57% | 35% |

| Interpretation | 91% | 83% |

| Crisis counselling | 30% | 22% |

Source: IRCC, iCARE, December 31, 2018.

Gender differences in accessing services

Gender parity existed among settlement services uptake for all federally-funded settlement services, apart from Employment Related Services where more Syrian men accessed the services than women.

For support services, gender parity or near parity existed with transportation, translation, interpretation, and crisis counselling. Differences in usage by gender existed with Care for Newcomer Children where more women accessed the services (61%), and less for Provision for Disabilities (43%).

3.2 Language

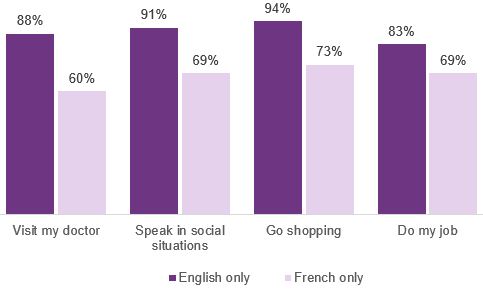

Summary: A large portion of Syrians have accessed IRCC-funded language services. Most Syrian survey respondents reported in 2018 being able to complete day-to-day tasks in English without help, while a lower ability was reported for completing tasks in French.

Language service usage

IRCC administrative data indicates 89% of Syrian adults have accessed IRCC-Funded Language Assessments and (77%) of Syrian adults have accessed IRCC-Funded Language Training since arriving in Canada.

| Immigration category | Language assessment (%) | Language training (%) |

|---|---|---|

| GAR | 93% | 89% |

| PSR | 84% | 61% |

| BVOR | 90% | 77% |

Source: iCARE, December 31, 2018

Communication skills

When asked in the 2018 departmental survey if they could communicate in English or French without help, most Syrian survey respondentsFootnote 12 reported being able to complete day-to-day tasks without help in English. French-only speaking Syrian survey respondents reported a lower ability to complete tasks without help.

Chart 8: I can communicate in English/French, without help when I...

Text version: I can communicate in English/French, without help when I...

| I can communicate in English/French, without help when I... | English only (%) | French only (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Visit my doctor | 88% | 60% |

| Speak in social situations | 91% | 69% |

| Go shopping | 94% | 73% |

| Do my job | 83% | 69% |

Source: IRCC, Settlement Outcomes Survey, 2018.

Language classes such as LINC, as well as other informal supports were critical to developing language skills among refugees. A SPO study indicated that two years after arrival, English language proficiency had increased among SyriansFootnote 13.

Research noted that Syrians felt pressure to develop sufficient language capacity in their first year in Canada, in order to become financially independentFootnote 14.

Barriers and challenges

Language challenges have been integration barriers for Syrians, leading to feelings of isolation among the populationFootnote 15.

A SPO study reported that work and education were the main barriers to accessing language training, followed by health and a lack of space in classFootnote 16.

In addition, studies from across the country have pointed to the inaccessibility of language classes for mothers of young children. These studies have noted that a lack of available childcare as barriers, and in some situations, families send one parent to language training, which research indicated to typically be the father of the householdFootnote 17.

Research also noted that some Syrians were unable to find accessible English Sign Language classes. Given that hearing problems were a common ailment of refugees, the research highlighted a need for specialized servicesFootnote 18.

3.3 Employment and looking for work

Summary: While Syrians had lower initial employment incidence compared to other resettled refugees, they appear to be on similar trajectories as other resettled populations.

Accessing the labour market

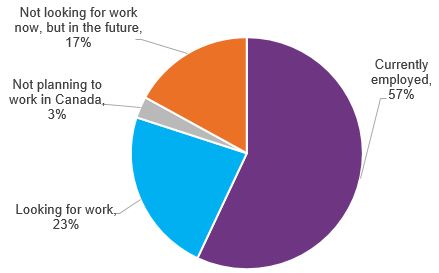

The 2018 Departmental survey has the most recent information regarding Syrian employment status.

The survey indicates that after 2 to 3 years in Canada, 57% of Syrian respondents reported being employed. Additionally, at the time of the survey, 23% of surveyed Syrians were looking for workFootnote 19.

Chart 9: 2018 Self-reported employment status

Text version: 2018 Self-reported employment status

| Employment status | % |

|---|---|

| Currently employed | 57% |

| Looking for work | 23% |

| Not planning to work in Canada | 3% |

| Not looking for work now, but in the future | 17% |

Source: IRCC, Settlement Outcomes Survey, 2018.

Of the Syrians reporting they were currently employed, PSRs were more likely to indicate they were employed.

| Immigration category | % |

|---|---|

| GAR | 43% |

| PSR | 60% |

| BVOR | 55% |

Source: IRCC, Settlement Outcomes Survey, 2018.

Note: This information is not weighted and should be considered exploratory.

Various factors, notably limited language skills, and lower levels of educational attainment of GARs can present challenges to joining the workforce, despite an eagerness to do soFootnote 20. Other significant labour market barriers include lack of knowledge regarding how to navigate the labour market, lack of social capital and networks to secure jobs, gaps in skills, and challenges in starting entrepreneurial venturesFootnote 21.

Research highlighted that Syrians had a desire to continue careers they had pursued in their home country (i.e., mechanics, construction workers)Footnote 22. However, foreign credential recognition was an obstacle for securing employment for some.

Early employment incidence

2016 tax recordsFootnote 23 data (released in late 2018) provide a historical picture of the initial employment incidence of Syrians within months of arrival in Canada.

2016 tax records report 5% of adultFootnote 24 Syrian GARs, 40% of PSRs and 15% of BVORFootnote 25 reported employment earnings within their first months after arrival. Syrian early employment incidence is lower than those of resettled refugees who arrived in Canada during the same time period, with 22% of resettled GARs, 56% of PSRs and 30% of BVORs reporting employment.

Similar to the 2016 survey of Syrian refugees conducted as part of the Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative, these results are an early indication of employment incidence for Syrian refugees, as they highlight the initial employment rates within months after arrival in Canada. These results may be attributed to differences in socio-demographic characteristics of Syrian refugees and certain other factors mentioned earlier, such as not receiving pre-arrival services and the expedited manner of their arrival to Canada.

3.4 Wages and salaries and social assistance

Summary: Syrians’ employment earnings increased with time spent in Canada. Syrian GAR and BVOR social assistance usage in 2016 aligns with historical trends for resettled populations.

Wages and salariesFootnote 26

As anticipated, wages and salaries of Syrians increased with time in Canada.

Chart 10: Average 2017 wages and salaries by Syrian cohort

Text version: Average 2017 wages and salaries by Syrian cohort

| Wages and salaries ($) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Immigration category | Arrived in 2015 | Arrived in 2016 |

| GAR | $15,100 | $10,700 |

| PSR | $22,000 | $19,700 |

| BVOR | $14,300 | $14,000 |

Source: Statistics Canada, 2017 T4 Data.

For those who arrived in 2016, the average wages and salaries for Syrian GARs in 2017 was $10,700, compared to $19,700 for Syrian PSRs, and $14,000 for Syrian BVORsFootnote 27.

Differences in earnings among the Syrian population may be attributed to adult Syrian GARs having lower levels of education and having less knowledge of Canadian official languages compared to adult Syrian PSRsFootnote 28.

Differences in wages and salaries among refugees

Wages and salaries of Syrians are lower than those reported for other resettled populations who arrived during the same time period.

Chart 11: Average 2017 wages and salaries for 2016 resettled populations

Text version: Average 2017 wages and salaries for 2016 resettled populations

| Wages and salaries ($) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Immigration category | Syrian (%) | Non-Syrian (%) |

| GAR | $10,700 | $13,400 |

| PSR | $19,700 | $24,100 |

| BVOR | $14,000 | $17,200 |

Source: Statistics Canada, 2017 T4 Data.

As highlighted in section 2.4, there are noticeable differences between the Syrian population and the resettled population, most notably in the area of language. 65% of Syrians at the time of arrival in Canada self-reported having no knowledge of English or French, compared to 42% of the resettled population. Limited language skills can limit employment uptake, as well as the types of jobs that are available.

Social assistance usageFootnote 29

93% of Syrian GARs and 88% of BVORs reported social assistance usage in their first year in Canada, and 2% of PSRsFootnote 30. As RAP income support is declared for tax purposes as social assistance benefits, a very high proportion of GARs and BVORs typically report social assistance in the first year in CanadaFootnote 31. As such, it is not unexpected that Syrian GARs and BVORs had higher social assistance usage than PSRs.

When looking at historical trends, these percentages of Syrians on social assistance align with previous resettled populations in their first year in CanadaFootnote 32.

3.5 Health, mental health and healthcare

Summary: Most surveyed Syrians reported having a doctor or healthcare provider, though a lack of language skills, understanding of services, and the stigma around mental health were the main factors preventing some Syrians from accessing healthcare.

71% of Syrian GARs who accessed federally-funded settlement services identified a need for health, mental health, or well-being support, compared to 32% of Syrian PSRs, and 35% of Syrian BVORFootnote 33. Unmet healthcare needs were reported to be high among refugees, particularly GARsFootnote 34.

Health

Departmental data indicated that of the Syrians who accessed the Interim Federal Health (IFH) Program, a large proportion was for medications, dental, and vision care.

| Category of care | Number of users |

|---|---|

| Assistive devices | 788 |

| Counselling | 59 |

| Dental care | 22,510 |

| Drugs | 27,717 |

| Home visits - nursing homes | 61 |

| Hospital care | 2,908 |

| Medical care | 11,864 |

| Other professional services | 5,254 |

| Transportation | 918 |

| Vision care | 15,492 |

Source: IFHP Database on Claims, as of December 31, 2017.

Research identified isolation, language barriers, not being connected with Arabic-speaking healthcare providers, lack of serious attention to their health concerns, and slow follow-up and referrals as reasons for declining health statusFootnote 35.

Mental health

A study conducted with Syrian women who recently moved to Canada indicated that participants described two major obstacles that prevent them from seeking or accessing mental health services – stigma of mental health and privacy concerns. Language difficulties also impacted their privacy, especially in the presence of an interpreterFootnote 36.

Self-perceived mental health among Syrians was noted to be very high in the initial months of arrival. However, post-resettlement stress is common among refugees; financial issues, employment, housing, and language acquisition are cited as factors that aggravate stressFootnote 37.

Research also reported a strong reluctance among Syrians to seek professional mental health services, with most choosing family and friends as the first and most important line of supportFootnote 38.

Healthcare

86% of surveyed Syrians reported having a family doctor or regular healthcare service provider.

Chart 12: I have a family doctor or regular healthcare service provider

Text version: I have a family doctor or regular healthcare service provider

| I have a family doctor or regular healthcare service provider | % |

|---|---|

| Yes | 86% |

| No | 14% |

Source: IRCC, Settlement Outcomes Survey, 2018.

Research indicated that access to healthcare is shaped by the available resources – namely, receiving health insurance encouraged health service utilization, while social disconnectedness and the lack of appropriate and adequate language resources prevented itFootnote 39. However, there can be difficulties in accessing the healthcare system, owing to inability to find family doctors, long waitlists for specialists, and a lack of interpretersFootnote 40.

Newcomers relied heavily on cultural brokers to navigate the healthcare system as they provided language and cultural interpretation servicesFootnote 41.

3.6 Daily life

Summary: Syrian survey respondents reported having enough information to conduct their day-to-day lives. Food security continues to be a concern.

Information

As of summer 2018, Syrian survey respondents reported having enough information to conduct their day-to-day livesFootnote 42. A majority of Syrian survey respondents indicated they had enough information to find the things they needed.

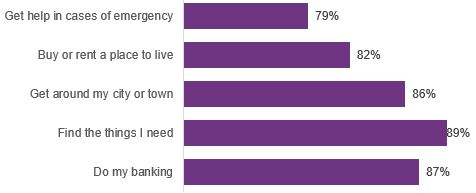

Chart 13: I had enough information to...

Text version: I had enough information to...

| I had enough information to... | % |

|---|---|

| Do my banking | 87% |

| Find the things I need | 89% |

| Get around my city or town | 86% |

| Buy or rent a place to live | 82% |

| Get help in cases of emergency | 79% |

Source: IRCC, Settlement Outcomes Survey, 2018.

Information provided to Syrians upon arrival focused on basic information on daily life in Canada, such as housing, language classes, and health care. Research noted that the information received by Syrians immediately after arrival was overwhelming, and such early information was often not retainedFootnote 43.

Research noted some challenges in getting information to Syrians, particularly due to difficulties in accommodating larger families and language proficiency barriers. Research also indicated that it was difficult to get information to Syrian womenFootnote 44.

Transportation

Walking and public transportation were identified as the two main modes of transportation used by Syrians, as barriers existed to having a car included cost of owning and maintaining a vehicleFootnote 45.

While Syrians who used public transportation generally had positive interactions, language barriers caused difficulties in navigating the bus systemsFootnote 46. Feelings of loneliness, boredom and sadness were reported by Syrians who had difficulties accessing transportationFootnote 47.

Food

Some Syrians reported struggling with food insecurity and relying on foodbanksFootnote 48. 23% of Syrians surveyed by IRCC reported that they sometimes or often did not have enough food and had no money to buy more. Additionally, 43% said they used a foodbank more than twiceFootnote 49.

Research reported that the availability and the cost of food was a concern to Syrians, and the desire to have food typical to their home country also contributed to the high cost of livingFootnote 50. Financial restrictions towards housing (i.e., most of the family income going to rent) was also cited as a factor of household food insecurityFootnote 51.

Family life

Research indicated that some Syrian families struggled with feeling safe and secure in Canada. The changing roles in the family, and trying to find meaning in their lives could be the reasons for this struggle. In addition, changing family dynamics after resettlement (for example, mother attending school with the intention of joining the workforce), could cause family tensionFootnote 52.

3.7 Students and youth

Summary: Syrian students face a variety of challenges integrating into schools, namely related to social and linguistic barriers.

Barriers to education

While Syrian students are acclimatizing to Canada, research found that they faced obstacles to school integrationFootnote 53.

Emotional and social barriers included feelings of isolated and separation. They are encountering difficulties in making friends, bullying and/or racism, and discrimination from other studentsFootnote 54. A sense of exclusion (i.e., not being able to feel a part of school activities due to language) can also lead to emotional and social barriersFootnote 55.

Linguistic barriers are attributed to low English proficiency, which can lead to a sense of marginalization at schoolFootnote 56.

Academic barriers included students feeling discouraged and developing low self-esteem due to low expectations of teachersFootnote 57. Many Syrian high school students also emphasized feeling discouraged, due to being placed in a lower grade. Inaccurate grade placement can occur due to differ languages of instruction, curriculum and educational structures in their home countries, and their temporary education experiencesFootnote 58.

Research noted additional challenges, including grief and trauma, due to the loss of their homes, social connections, witnessing violence and death of loved ones, as well as anxiety and stressFootnote 59.

Youth

Research indicated that there were educational gaps among students aged 14 to 18, as their lives prior to arrival in Canada has created an unusual situation. A SPO study noted that youth sometimes had to re-start their education at earlier gradesFootnote 60.

Many youth reported feeling lost and unsure of what their next steps would be after completing high schoolFootnote 61. Youth also found it hard to figure out what was needed to study to get into university – the overall requirements for post-secondary education and the courses that should be taken in high school were not always clearFootnote 62.

Syrian youth, like adults, encountered difficulties getting accreditation or recognition of diplomas and qualifications obtained overseasFootnote 63. In some situations overseas, youth had dropped out of school and had been working in Lebanon or Jordan, as they were not permitted by the local governments to attend schoolFootnote 64.

Making friends

Research indicated that Syrian young adults, (between the ages of 18 and 30) reported having very few friends they are emotionally close to, with 26% of 18-25 year olds and 38% of 26-30 year olds reporting no close friends, as compared to those 51 years and older who seem to have more close friends than younger onesFootnote 65.

Social media usage

As with all youth, social media plays an important role. Research indicated that Syrian youth found social media to be a useful tool after arriving in Canada. Social media and mobile phones helped them navigate Canada with the phone’s GPS tracker, and figure out how to access to health care services and find jobsFootnote 66. It also supported educational purposes, such as translation toolsFootnote 67.

3.8 Education

Summary: A large percentage of Syrian children were reported as enrolled in school. Supports for students and teachers are important to facilitating the integration of students into the school system.

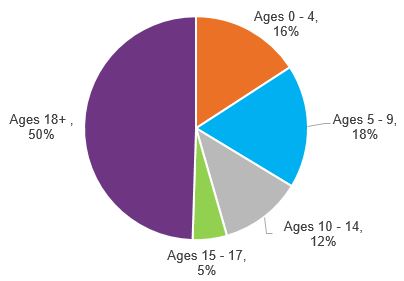

A primary characteristic of the Syrian population was the number of children and youth, with 46% under the age of 15 when they arrived in Canada.

Chart 14: Syrian children at time of arrival

Text version: Syrian children at time of arrival

| Age at time of landing | % |

|---|---|

| Ages 0 - 4 | 16% |

| Ages 5 - 9 | 18% |

| Ages 10 - 14 | 12% |

| Ages 15 - 17 | 5% |

| Ages 18+ | 50% |

Source: IRCC, Permanent Residents, Feb. 28, 2019.

Research found that the arriving Syrian students had experienced disruptions to their formal schoolingFootnote 68.

Parents

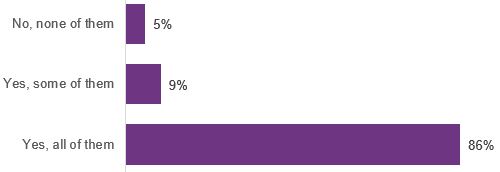

The 2018 Departmental survey found that a majority of Syrian parents reported that their school-age children were enrolled in school.

Chart 15: My children are enrolled in school

Text version: My children are enrolled in school

| School age children attending school | % |

|---|---|

| Yes, all of them | 86% |

| Yes, some of them | 9% |

| No, none of them | 5% |

Source: IRCC, Settlement Outcomes Survey, 2018.

Language barriers were identified by Syrian parents who wished to be more active in their children’s education. Parents often expressed feeling a sense of uncertainty about their roles in their children’s education, particularly due to not having enough information on how to navigate the Canadian school systemFootnote 69.

Teachers

Research from the Greater Toronto Area found that teachers and educators did not have enough preparation and support for working Syrian familiesFootnote 70. The study highlighted the need for teachers to have information regarding intercultural communication and anti-discriminatory educationFootnote 71.

However, research highlighted that while a school can be sensitive and supportive to the various needs of Syrians (i.e., dealing with trauma), occasional modification to programing to be more supportive would be beneficialFootnote 72.

Settlement Workers in Schools

The Settlement Workers in Schools (SWIS) program put settlement workers from community agencies into schools with high numbers of newcomers to offer specialized, culturally-appropriate services to students and their familiesFootnote 73. Studies have found that SWIS workers have been important assets for youth and their familiesFootnote 74.

Research found that teachers viewed settlement workers in schools played an active role in supporting the integration of Syrian children.

3.9 Becoming part of the community

Summary: Syrians are integrating into their communities by making friends, volunteering and building ties which have contributed to a strong sense of belonging.

Sense of belonging

The 2018 Departmental survey found that Syrians reported having a strong sense of belonging, primarily to Canada, as well their local community.

Chart 16: I have a strong sense of belonging to...

Text version: I have a strong sense of belonging to...

| I have a strong sense of belonging to... | % |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | 64% |

| Province/Territory | 83% |

| Local community | 84% |

| Canada | 90% |

Source: IRCC, Settlement Outcomes Survey, 2018.

These results are comparable to that of the overall refugee population in which 76% reported a strong sense of belonging to their community and 96% to Canada. Syrians’ sense of belonging to Canada is comparable to that of Canadian-born (91%)Footnote 75.

Research from Montreal found similar results, with 63% of PSRs reporting a strong sense of belonging to the city and communityFootnote 76. However, research from Ontario reported that combatting racism and social exclusion are factors that impede the sense of belongingFootnote 77.

Connecting with the community

More than one-third of departmentally surveyed Syrians indicated that they had volunteered in the past 12 months.

Research from Ontario found that Syrian parents and older adults made various efforts to reduce their social isolation and become part of the community. Efforts have included visiting mosques, local community centres, their children’s schools, and other gathering spaces to meet others and explore their communityFootnote 78.

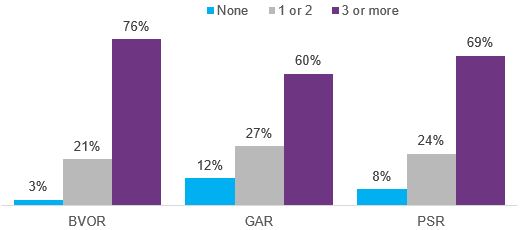

Making friends

Overall, 92% of Syrians reported that they had more than one close friendFootnote 79.

Chart 17: I have close friends in the same city/community as me

Text version: I have close friends in the same city/community as me

| Immigration category | None (%) | 1 or 2 (%) | 3 or more (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BVOR | 3% | 21% | 76% |

| GAR | 12% | 27% | 60% |

| PSR | 8% | 24% | 69% |

Source: IRCC, Settlement Outcomes Survey, 2018.

Research noted that while newcomers were making friends and building ties, these were largely focused on settlement needs or connecting with the socio-cultural communityFootnote 80. GARs were found to have stronger ties to settlement agencies while PSRs had stronger connections to community networksFootnote 81.

Research found that certain socio-demographic characteristics among Syrians were indicators for having friends. For example, Syrians with higher English or French abilities were more likely to have friends from outside their ethnic communitiesFootnote 82. Also, the older Syrians were more likely to have few friends, with 16% of research participants over the age of 65% reporting being friendlessFootnote 83.

Certain factors were found to prevent social interaction of Syrians, namely lack of public transportation, economic constraints (both in working all the time and not enough money for social activities), as well as language barriersFootnote 84.

3.10 Community supports

Summary: Communities played a large role in Syrian resettlement and, overwhelmingly, Syrians felt their community was welcoming to newcomers.

Private sponsors

Regarding reasons as to why they sponsored, media coverage was cited as an important motivation for sponsorship, as well as personal or family history of immigrationFootnote 85.

Research highlighted that individuals who tend to be private sponsors include those with financial resources, time, and social capital. A benefit of a sponsor who has previously sponsored would be that they are aware of the commitment demands, compared to new sponsorsFootnote 86.

Experiences and integration of PSRs varied and depended on the commitment and resourcefulness of their sponsorsFootnote 87.

Local immigration partnerships

Research cited that the LIP relationship to RAP agencies were crucial, especially in the early stages, to the initiative. This was most evident in the case of finding housing for Syrian refugees; RAP centers were overwhelmed and could have benefitted by taking advantage of LIPs to help with coordinationFootnote 88.

Welcoming communities

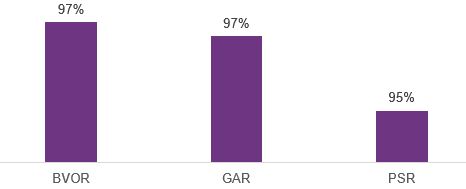

2018 Departmental survey found that overall, 96% of Syrian refugees agreed with the statement “In my experience, my community is welcoming to newcomers.”

Chart 18: My community is welcoming to newcomers

Text version: My community is welcoming to newcomers

| Immigration category | % |

|---|---|

| BVOR | 97% |

| GAR | 97% |

| PSR | 95% |

Source: IRCC, Settlement Outcomes Survey, 2018.

A southern Ontario community noted that there were challenges at the onset with the influx of Syrians and their immediate needs – namely finding housing, effectively using the community supports, and fatigue among service providersFootnote 89. However, positives were noted in that there is now a better knowledge of resources that resettlement organizations provideFootnote 90.

Research reported that the size of the community can provide different benefits to the Syrians. Larger communities had the availability of more organizations that can fill service gaps and provide services in multiple languages. Smaller urban centers had more engaged community which were mobilized quicklyFootnote 91.

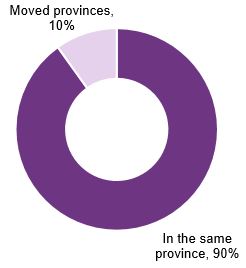

Moving between provinces

90% of surveyed Syrians remained in their original province of landing.

Chart 19: Changing provinces

Text version: Changing provinces

| Mobility | % |

|---|---|

| In the same province | 90% |

| Moved provinces | 10% |

Source: IRCC, Settlement Outcomes Survey, 2018.

Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick were the only provinces that experienced outward migration of Syrians.

Of those Syrians who left from their original province, 67% reported moving to Ontario. Alberta saw the second highest influx, accounting for 12% of those that moved.

Conclusion and moving forward

The emerging information about Syrian settlement shows positive early outcomes, and also highlights some of the challenges still facing this group. While some Syrians face obstacles in their integration to Canada, these are not necessarily unique to the Syrian population. In fact, most are common difficulties faced by recent newcomers in general, particularly resettled refugees who are fleeing vulnerable situationsFootnote 92.

Overall, integration outcomes of Syrians have been steadily improving since their arrival in Canada, and are in alignment with other resettled populations.

Early labour market results are generally encouraging, as Syrians’ employment rates are increasing over time. And while their early wages and salaries were slightly below those of other refugees, these earnings appear to be on similar trajectories to other resettled populations. Factors such as limited language skills, lower levels of education, and foreign credential recognition have been noted as obstacles to securing employment.

It is also encouraging that Syrians are making use of federally-funded settlement services, with nearly all adult GARs and BVORs having accessed settlement services. And a large portion of adult Syrians have taken IRCC-funded language services. These types of services are key integration supports that help newcomers adjust to life in their new home as quickly as possible.

Syrians are integrating well into their communities, reporting a strong sense of belonging to Canada and their communities. They are also volunteering and making friends. Many Syrians feel they have the information they need to navigate day-to-day life, their children are enrolled in school, and many have doctors or a regular healthcare service provider.

Settlement and integration takes time. As Syrians are at relatively early stages of their integration journey, their outcomes story will continue to evolve as they spend more time in Canada and make it their home.

5. Sources

5.1 Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment (iCARE)

iCARE collects information from IRCC-Funded Service Provider Organizations about Resettlement and Settlement Program outputs: clients served and their characteristics, services delivered and their characteristics (e.g., method of delivery, topics covered). iCARE captures detailed information from Service Provider Organizations on the resettlement and settlement services provided to clients monthly. The information is linked by IRCC to administrative data to provide demographic and service usage information on clients.

5.2 2018 IRCC Settlement Outcomes Survey

IRCC conducted a 2018 departmental survey of the newcomer population – both Settlement and Resettlement Program clients, as well as non-clients (i.e., permanent residents who did not access IRCC settlement services) for the purposes of collecting performance measurement information. The survey was conducted in July 2018. Data collected includes information from the client about knowledge gains, behavioural changes and the settlement services’ role in their integration path. The client-specific survey is used to measure performance of the Settlement Program, while the non-client survey is used as an important comparison group against which to measure results and inform program direction.

5.3 2016 Longitudinal Immigration Database and 2017 T4 earnings

The IMDB is a unique longitudinal database that combines administrative data on landed immigrants with their income tax returns, and is a key information source which can be used to investigate the economic performance of immigrants by a wide range of socio-economic characteristics (e.g., income, wages and employment earnings, social assistance rates, mobility within Canada). The IMDB can distinguish Syrian refugees to enable analysis of their economic performance.

Due to the timing of tax filing, there is a two year lag in obtaining IMDB data.

2016 IMDB

2016 IMDB data has been analyzed, which combines administrative immigration data with T1 Family Files (T1FF) through probabilistic record linkage. The data is a census with longitudinal design, and as data is collected for all units of the target population, no sampling is done.

2017 IMDB – T4 wages and salaries

2017 wages and salaries are collected of those working within Canada by using T4 slips (statement of remuneration) rather than relying on T1. These wages and salaries outcomes offer preliminary economic results ahead of the T1 family file. As the T4 files are based on what the employer reports and not what the individual reports as income, this information does not include self-declared income (e.g., tips, self-employment, investments), or supplementary income (i.e., Child tax benefit, social assistance, etc.).

5.4 IRCC-SSHRC Funded research

To supplement outcomes information on Syrian refugee experience, IRCC and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) jointly launched a research initiative on Syrian refugee resettlement in Canada, in early 2016. The initiative resulted in 27 research projects that focused on various aspects of refugee resettlement and integration. Many of the projects are being finalized and results are becoming available. A list of IRCC-SSHRC funded studies are listed in Annex D.

5.5 Non-governmental research and studies

Various research, literature and studies on the Syrian population have been conducted by academics, researchers, SPOs, and non-governmental organizations. Interest has been extremely high for this population and as such, numerous studies have been conducted across the country, focusing on particular themes unique to the Syrian population as well as the community of analysis. As mentioned earlier, these reports, studies and research come with their own caveats and limitations.

A full list of research used for this report can be found in Annex E.

5.6 Statistics Canada – General Social Survey 2013 and Census 2016

General Social Survey 2013

General Social Survey (GSS) gathers data on social trends in order to monitor changes in the living conditions and well-being of Canadians, and to provide information on specific social policy issues. GSS is linked to IRCC landing data, through Statistics Canada tabulations.

Census 2016

The 2016 Census data enumerated approximately 25,000 Syrian refugees who landed between January 1, 2015 and May 10, 2016. In addition, Census data primarily focuses on populations living only in private households, which would exclude people living in collective dwellings. It also excludes individuals who would have left Canada prior to May 10, 2016.

Some notable limitations of the data analysis include the merging of PSRs and BVORs into one immigration category, and identifying Syrian refugees as a person who was born in Syria or who had Syrian citizenship. As a result, it does not map back to the dataset that IRCC has on Syrian refugees.

While the Census provides valuable information, it has significant limitations on the ability to fully report on the early integration outcomes of Syrian refugees, as the resettled Syrian refugees in this study have been in Canada for less than six months at the time of the 2016 Census.

5.7 Federal government and parliamentary studies

A variety of studies and reports have been conducted by the federal government regarding the monitoring of outcomes of Syrian refugees and the programs that impact them.

- IRCC, Research and Evaluation Branch. (2016). Rapid Impact Evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative

- IRCC, Research and Evaluation Branch. (2016). Evaluation of the Resettlement Programs

- IRCC, Research and Evaluation Branch. (2017). Evaluation of the Settlement Program

- IRCC, Research and Evaluation Branch. (2018). Evaluation of Pre-Arrival Settlement Services

- IRCC, Internal Audit and Accountability Branch. (2017). Internal Audit of the Operation Syrian Refugees – Settlement (2017)

- IRCC, Internal Audit and Accountability Branch. (2017). Internal Audit of the Operation Syrian Refugees – Identification and Processing (2017)

- Statistics Canada (2018). Income and Mobility of Immigrants, 2016. The Daily.

- Parliament of Canada, Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration (2016). After the warm welcome: Ensuring that Syrian refugees succeed. 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, Report No. 7. November

- Parliament of Canada, Standing Committee on Public Accounts (2018). Settlement Services for Syrian Refugees – Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, of the 2017 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada. 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, Report No. 3.

- Senate of Canada, Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights. (2016). Finding refuge in Canada: A Syrian resettlement story. 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, Report No. 5. December.

- Auditor General of Canada (2017). Settlement Services for Syrian Refugees – Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Report 3 of the 2017 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada.

Annex A: Socio-demographic profile of Syrians

Between November 4, 2015 and December 31, 2016, 39,650 Syrians arrived in Canada as part of the Syrian Refugee Initiative.

| Immigration category | % |

|---|---|

| Government Assisted | 55% |

| Privately Sponsored | 35% |

| Blended Visa Office Referred | 10% |

| Landing year | % |

|---|---|

| November 4, 2015 – December 31, 2015 | 15% |

| January 1, 2016 – March 1, 2016 | 51% |

| March 2, 2016 – December 31, 2016 | 34% |

| Gender | % |

|---|---|

| Male | 51% |

| Female | 49% |

| Education level | GAR (%) | PSR (%) | BVOR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 29% | 15% | 26% |

| Secondary or less | 62% | 51% | 46% |

| More than secondary, but less than Bachelor | 2% | 15% | 2% |

| Bachelors or higher | 1% | 18% | 1% |

| Not stated | 5% | 2% | 24% |

70% of Syrian refugees were spouses and dependents

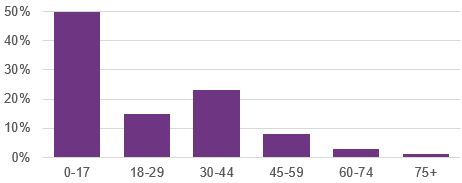

Chart 20: Age at time of arrival in Canada

Text version: Age at time of arrival in Canada

| Age at time of arrival in Canada | % |

|---|---|

| 0-17 | 50% |

| 18-29 | 15% |

| 30-34 | 23% |

| 45-59 | 8% |

| 60-74 | 3% |

| 75+ | 1% |

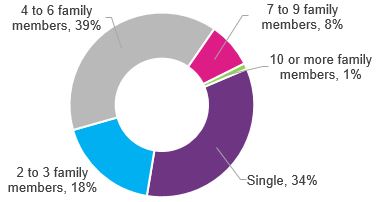

Chart 21: Size of family units

Text version: Size of family units

| Size of family units | % |

|---|---|

| Single | 34% |

| 2 to 3 family members | 18% |

| 4 to 6 family members | 39% |

| 7 to 9 family members | 8% |

| 10 or more family members | 1% |

11,800 Syrian family units arrived in Canada under the Syrian Refugee Initiative

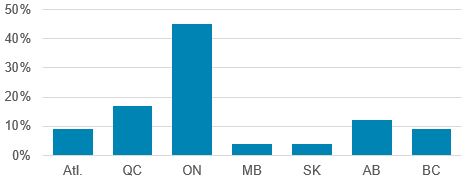

Chart 22: Province of intended destination

Text version: Province of intended destination

| Province of intended destination | % |

|---|---|

| Atlantic | 9% |

| QC | 17% |

| ON | 45% |

| MB | 4% |

| SK | 4% |

| AB | 12% |

| BC | 9% |

Annex B: Profile of IRCC-Funded Settlement Services usage (iCARE) – Syrian profile

Of the Syrian refugees who landed in Canada between Nov. 4, 2015 and Dec. 31, 2016, 15,345 adult Syrian refugees (excluding those whose intended destination was Quebec) have accessed IRCC-Funded Settlement Services.

| Immigration category | % |

|---|---|

| Government Assisted | 53% |

| Privately Sponsored | 36% |

| Blended Visa Office Referred | 11% |

| Family status | % |

|---|---|

| Principal applicant | 58% |

| Spouse or dependent | 42% |

| Gender | % |

|---|---|

| Male | 50% |

| Female | 50% |

| Year | % |

|---|---|

| 2015 | 3% |

| 2016 | 93% |

| 2017 | 92% |

| 2018 | 84% |

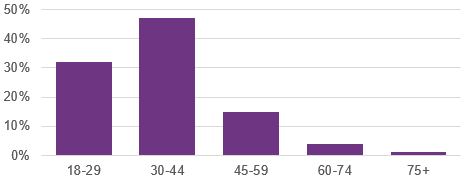

Chart 23: Age at time of arrival in Canada

Text version: Age at time of arrival in Canada

| Age at time of arrival in Canada | % |

|---|---|

| 18-29 | 32% |

| 30-44 | 47% |

| 45-59 | 15% |

| 60-74 | 4% |

| 75+ | 1% |

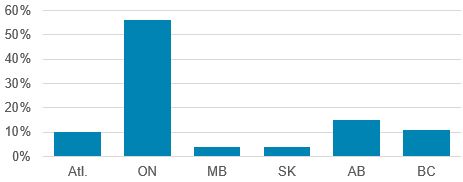

Chart 24: Province of intended destination

Text version: Province of intended destination

| Province of intended destination | % |

|---|---|

| Atlantic | 10% |

| ON | 56% |

| MB | 4% |

| SK | 4% |

| AB | 15% |

| BC | 11% |

Annex C: IRCC Settlement Outcomes Survey – Syrian respondent profile

1,255 survey respondents were admitted to Canada as part of the Syrian Refugee Initiative.

Syrian survey respondents were disproportionately male, principal applicants, privately sponsored refugees, and had higher education levels.

| Immigration category | % |

|---|---|

| Government Assisted | 18% |

| Privately Sponsored | 76% |

| Blended Visa Office Referred | 10% |

| Landing year | % |

|---|---|

| 2015 | 12% |

| 2016 | 52% |

| 2017 | 36% |

| Gender | % |

|---|---|

| Male | 66% |

| Female | 34% |

| Education | % |

|---|---|

| None | 4% |

| Secondary or less | 23% |

| More than secondary, but less than Bachelor | 33% |

| Bachelors or higher | 40% |

| Not stated | 3% |

78% of Syrian survey respondents were principal applicants

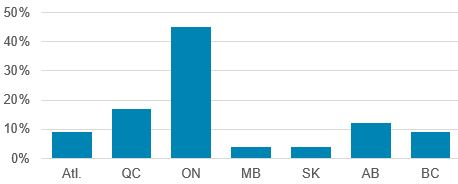

Chart 25: Province of intended destination

Text version: Province of intended destination

| Province of intended destination | % |

|---|---|

| Atlantic | 9% |

| QC | 17% |

| ON | 45% |

| MB | 4% |

| SK | 4% |

| AB | 12% |

| BC | 9% |

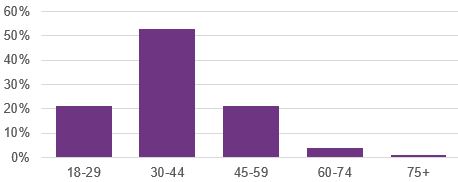

Chart 26: Age at time of survey

Text version: Age at time of survey

| Age at time of survey | % |

|---|---|

| 18-29 | 21% |

| 30-44 | 53% |

| 45-59 | 21% |

| 60-74 | 4% |

| 75+ | 1% |

Note: The Settlement Outcomes Survey (conducted summer 2018) was administered to all IRCC settlement clients and newcomers who were over the age of 18 at the time of the survey. Survey responses for Syrian refugees have been extracted for Syrian reporting purposes.

As the survey was administered online, respondents are limited to those of which IRCC had active email addresses.

Annex D: List of IRCC-SSHRC funded research on Syrians

Agrawal, S., & Zeitouny, S. (2017). Settlement experience of Syrian refugees in Alberta (PDF, 528 KB).

Ahmed, R., Pottie, K., & Veronis, L. (2018). The role of social media in the lives of Syrian refugee youth: How Syrian refugees use social media to improve their experiences of resettlement. BMRC Research Digest, Winter 2018.

Baker, J. White post-secondary youths observations of racism towards refugees in two Canadian cities. Association of New Canadians.

Banting, K. Mapping the terrain: Assessing the scope, strength and future potential of civil society organizations active in Syrian refugee sponsorship and early integration.

Belkhodja, C. Accueil et intégration des réfugiés syriens dans des villes secondaires au Nouveau Brunswick et au Québec : les cas de Moncton et Sherbrooke-Granby

Clark-Kazak, C. R. (2017). Ethical considerations: Research with people in situations of forced migration. Refuge, 33(2).

Esses, V. M. Optimizing the provision of information to facilitate the settlement and integration of refugees in Canada: Case studies of Syrian refugees in London, Ontario and Calgary, Alberta.

Fang, T. Syrian refugee arrival, resettlement and integration in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Farber, S., et al. (2018). Transportation barriers to Syrian newcomer participation and settlement in Durham Region. Journal of Transport Geography, 68, 181-192.

Guo, Y. Exploring initial school integration among Syrian refugee children

Janzen, R., et al. (2017). Policy brief: The impact of the Syrian refugee influx on local systems of support: A collaborative research project in Waterloo Region. Centre for Community Based Research.

Jordan, S. R. Enhancing psychological adaptation of LGBT refugees resettling from Syria: Mixed methods pilot for longitudinal community engaged research

Kirova, A. Cultural brokering with Syrian refugee families with young children: an exploration of challenges and best practices in psychosocial adaptation

Kosny, A., et al. (2018). Safe employment integration of recent immigrants and refugees. Institute for Work and Health.

Kyriakides, C. Rural reception contexts: A study of the inclusion and exclusion of sponsored Syrian refugees in Northumberland County, Ontario

McKenzie, K., et al. (2017). Exploring the mental health and service needs of Syrian refugees within their first two years in Canada [Presentation].

Papazian-Zohrabian, G. Favoriser l’intégration sociale et scolaire des élèves réfugiés syriens en développant leur sentiment d’appartenance à l’école, leur bien-être psychologique et celui de leurs familles

Peng, M., & Milkie, M. A. Parenting stress in settlement: Assessing parenting strains and buffers among Syrian refugee parents during early integration into Canada

Rodriguez del Barrio, L. Regards croisés sur le parrainage privé au Québec enjeux défis et leviers d’intervention

Rose, D., & Charrette, A. (2017). Finding housing for the Syrian refugee newcomers in Canadian cities: Challenges, initiatives and policy implications. Synthesis report. INRS Centre-urbanisation Culture Société.

Stewart, J., & Martin, L. (2018). Bridging two worlds: Supporting newcomer and refugee youth. CERIC.

Ungar, M. T. Canada-Germany research collaboration.

Vatanparast, H. The impact of socio-economic and cultural factors on household food security of Syrian refugees in Canada.

Walton-Roberts, M., et al. (2017). Comparative evaluation of Local Immigration Partnerships (LIPs) and their role in the Syrian refugee resettlement process. International Migration Research Centre.

Annex E: Bibliography

Agrawal, S., & Zeitouny, S. (2017). Settlement experiences of Syrian refugees in Alberta (PDF, 528 KB).

Ahmed, A., Brown, A., & Feng, C. X. (2017). Maternal depression in Syrian refugee women recently moved to Canada: A preliminary study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), 240.

Ahmed, R. & Veronis, L. (2017). Tracing gendered practices in social media use among Syrian refugees in Ottawa, Canada.

Ahmed, R., & Veronis, L. (2018). The role of social media in the lives of Syrian refugee youth. How Syrian refugees use social media to improve their experiences in resettlement. BRMC Research Digest, Winter 2018.

Alberta Association of Immigrant Servicing Agencies (2017). Alberta Syrian Refugee Resettlement Experience Study.

Canada, IRCC (2016). Syrian refugee resettlement initiative – Looking to the future.

-- (2018). Interim Federal Health Program: Summary of coverage.

Canada, IRCC, Internal Audit and Accountability Branch. (2017). Internal audit of the Operation Syrian Refugees – Identification and processing.

-- (2017). Internal audit of the Operation Syrian Refugees – Settlement.

Canada, IRCC, Research and Evaluation Branch. (2016a). Rapid impact evaluation of the Syrian Refugee Initiative.

-- (2016b). Evaluation of the resettlement programs.

-- (2017). Evaluation of the Settlement Program.

-- (2018). Evaluation of pre arrival settlement services.

Canada, Statistics Canada (2018). Income and mobility of immigrants, 2016. The Daily.

Canada, Statistics Canada (2019). Results from the 2016 Census: Syrian refugees who resettled in Canada in 2015 and 2016. René Houle.

Drolet, J., & Moorthi, G. (2018). The settlement experience of Syrian newcomers in Alberta: Social connections and interactions. Canadian Ethic Studies, 50(2), 101-120.

English, K., Ochocka, J., & Janzen, R. (2017). Exploring the pathways to social isolation: A community-based study with Syrian refugee parents and older adults in Waterloo Region. Centre for Community Based Research.

Esses, V., & Hamilton, L. (2017). Optimizing the provision of information to facilitate the settlement and integration of refugees in Canada: Case studies of Syrian refugees in London, Ontario and Calgary, Alberta.

Fang, T., Sapeha, H., Neil, K., Jaunty-Aidamenbor, O., Persaud, D., Kocourek, P., & Osmond, T. (2017). Syrian refugee arrival, resettlement and integration in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Farber, S., et al (2018). Transportation barriers to Syrian newcomer participation and settlement in Durham Region. Journal of Transport Geography, 68, 181-192.

Gagné, A., Al-Hashimi, N., Little, M., Lowen, & M., Sidhu, A. (2018). Educator perspectives on the social and academic integration of Syrian refugees in Canada. Journal of Family Diversity in Education, 3(1), 48-76.

Guo, Y. (2018). Exploring initial school integration among Syrian refugee children.

Guruge, S., Sidani, S., Illesinghe, V., Younes, R., Bukhari, H., Altenberg, J., Rashid, M., & Fredericks, S. (2018). Healthcare needs and health service utilization by Syrian refugee women in Toronto. Conflict and Health, 12(46).

Hanley, J., Al Mhamied, A., Cleveland, J., Hajjar, O., Hassan, G., Ives, N., Hynie, M., et al. (2018). The social networks, social support and social capital of Syrian Refugees privately sponsored to settle in Montreal: Indications for employment and housing during their early experiences in integration. Canadian Ethic Studies, 50(2), 123-148.

Immigrant Services Society of BC. (2016a). Syrian refugee operation to British Columbia: One year in – A roadmap to integration and citizenship (PDF, 4.62 MB).

-- (2016b). Syrian Refugee Youth Consultation: Summary report (PDF, 1.62 MB). Overview of Consultation, September 17, 2016. Vancouver, British Columbia.

Immigrant Services Society of BC. (2018). Syrian refugees: After year two in British Columbia.

Janzen, R. P., Ochocka, J., English, K., Fuentes, J., & Morton Ninomiya, M. (2017). Policy brief: The impact of the Syrian refugee influx on local systems of support: A collaborative research project in Waterloo Region (PDF, 678 KB). Centre for Community Based Research.

Macklin, A., Barber, K., Goldring, L., Hyndman, J., Korteweg, A., Labman, S., & Zyfi, J. (2018). A preliminary investigation into private refugee sponsors. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 50(2), 35-57.

McKenzie, K., Hynie, M., Agic, B., Roche, B., Oda, A., Tuck, A., & Bennett-Abuayyash, C. (2017). Exploring the mental health and service needs of Syrian refugees within their first two years in Canada.

Nofal, M. (2017). For our children: A research study on Syrian refugees’ schooling experiences in Ottawa (Master’s Thesis, University of Ottawa).

Oda, A., Tuck, A., Agic, B., Hynie, M., Roche., B., & McKenzie, K. (2017). Health care needs and use of health care services among newly arrived Syrian refugees: A cross-sectional study. CMAJ open, 5(2), E354.

Kosny, A., Yanar, B., Begum M., Al-khooly, D., Premji, S., Lay, M., & Smith, P.M. (2018). Safe employment integration of recent immigrants and refugees. Institute of Work and Health.

Kirova, A., Yohani, S., Georgis, R., Gokiert, R., Mejia, T., & Chiu, Y. (n.d.). Cultural brokering with Syrian refugee families with young children: An exploration of challenges and best practices in psychological adaptation.

Papazian-Zohrabian, G., Mamprin, C., Lemire, V., Hassan, Gh., Rousseau, C., Turpin-Samson, A., & Aoun, R. (2017). Promoting the social and educational integration of Syrian refugee students by developing their sense of belonging to the school, their psychological well-being and that of their families (PDF, 547 KB). Université de Montréal.

Perkins, J. (2018). Settlement experiences of Syrian refugees (Master’s Thesis, University of Western Ontario).

Shields, J., & Lujan, O. (2018). Immigrant youth in Canada: A literature review of migrant youth settlement and service issues. Knowledge synthesis report (PDF, 386 KB). CERIS.

Stewart, J., & El Chaar, D. (2017). Syrian refugee youth mental health current status in Canada.

Stewart, J., & Martin, L. (2018). Bridging two worlds: Supporting newcomer and refugee youth. CERIC.

Vatanparast, H. (n.d.). The impact of socio-economic and cultural factors on household food security of Syrian refugees in Canada. [Presentation].

Walton-Roberts, M., et al. (2017). Comparative evaluation of Local Immigration Partnerships (LIPs) and their role in the Syrian refugee resettlement process. International Migration Research Centre.

Wilkinson, L., et al. (2017). Initial results of the Western Canadian Syrian Refugee Resettlement Survey (PDF, 1.61 MB). Presented at the Small Centre Promising Practices Learning Event, Brandon MB. June 27, 2017.

Yohani, S., Kirova, A., Georgis, R., Gokiert, R., Mejia, T., & Chiu, M. (2019). Cultural brokering with Syrian refugee families with young children: An exploration of challenges and best practices in psychosocial adaptation. Journal of International Migration and Integration.